AACR Annual Meeting News: Read the latest session previews and recaps from the official news website.

Select "Patients / Caregivers / Public" or "Researchers / Professionals" to filter your results. To further refine your search, toggle appropriate sections on or off.

Cancer Research Catalyst The Official Blog of the American Association for Cancer Research

Home > Cancer Research Catalyst > Experts Forecast Cancer Research and Treatment Advances in 2022

Experts Forecast Cancer Research and Treatment Advances in 2022

The year 2021 defied our expectations in a variety of ways.

The delta and omicron COVID-19 variants imposed unprecedented challenges on the health care system and threatened our hopes of an end to the pandemic, but widespread vaccine distribution provided protection, preventing an estimated 36 million cases and 1 million deaths in the United States. As omicron called into question the efficacy of existing vaccines, tests, and treatments, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) provided new options, in the form of emergency use authorizations for the first two oral COVID-19 drugs, nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (Paxlovid) and molnupiravir (Lagevrio).

Aside from the pandemic, supply chain delays and worker shortages sparked frustration, but the national unemployment rate gradually fell to its lowest percentage since February 2020. Through a year of harsh weather conditions ranging from ice storms to wildfires to hurricanes and tornadoes, the United States doubled down on initiatives to battle climate change .

In spite of the year’s setbacks, the field of cancer research also made progress. The FDA approved 16 new oncology drugs —including two to treat genetic conditions that cause high rates of tumor formation—as well as two cancer detection agents that help physicians better identify certain tumors during imaging or surgery. We celebrated the 50th anniversary of the National Cancer Act , saw marked progress in many areas of cancer research , and helped provide cancer patients with reliable information about their COVID-19 risks and vaccine efficacy .

As in previous years , we have asked a panel of experts to reflect on the progress made in 2021 and forecast their predictions for cancer research in the year 2022. We spoke with AACR President-Elect Lisa Coussens, PhD, FAACR , about basic research; AACR board member and co-editor-in-chief of Cancer Discovery Luis Diaz Jr., MD , about precision immunotherapy; co-editor-in-chief of Cancer Prevention Research Michael Pollak, MD , and deputy editor of Cancer Prevention Research Avrum Spira, MD , about cancer prevention; and AACR board member and former Annual Meeting Program Chair John Carpten, PhD, FAACR , about cancer disparities.

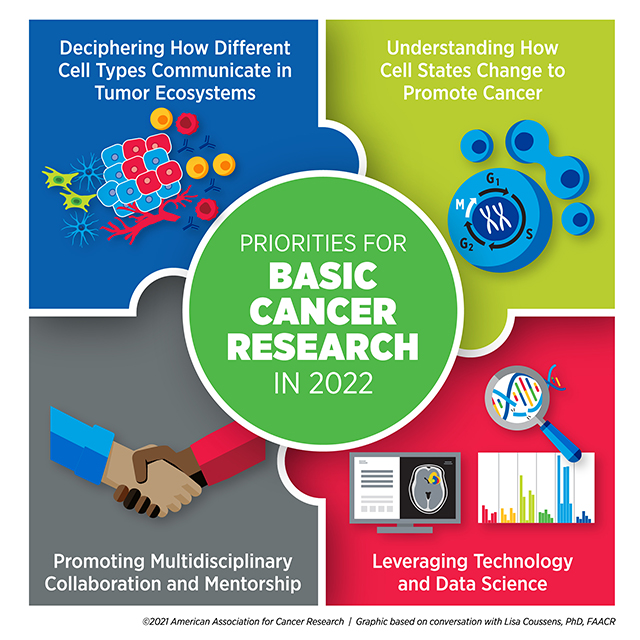

Priorities for Basic Research in 2022

“There isn’t a drug on the market that doesn’t have its origins in a basic science discovery,” said Lisa Coussens, PhD, FAACR , chair of the department of Cell Development and Cancer Biology at Oregon Health and Science University, when asked about the ways that laboratory science has shaped the landscape of cancer care. “We can’t lose sight of the importance of basic research at any step in the pipeline toward advancing cancer medicine and improving outcomes for our patients.”

Basic science—fundamental research about the way cells and molecules function and interact—spans applications from protein chemistry to cell genomics to animal models. Such discoveries help researchers determine, for example, which proteins can be targeted with drugs to fight a disease, or which biomarkers might help determine a patient’s prognosis or course of treatment.

An important priority for improving our knowledge of cancer cell biology, Coussens explained, is to better understand how cells shift between different states, especially in response to a disease or therapy.

“We need to understand nuances between different tissue states within our body, and how they respond to changes in their environment,” Coussens said, noting that this is true in healthy organs as well as in evolving tumors, where single cell types typically steer disease processes but are dependent on cues from the multiple cell types surrounding them.

“Understanding those nuances will lead to bigger discoveries about how to target cell state changes so we can return cells back to normal control mechanisms,” she continued.

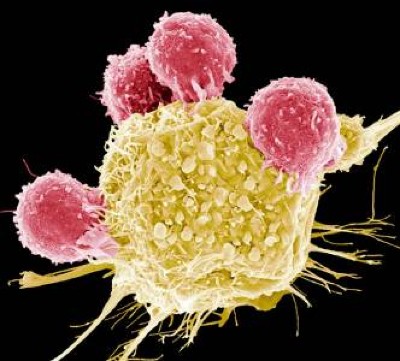

Tumor cells are not the only cells that might change their patterns of gene expression and metabolism during the course of cancer progression and treatment, however. Other cells that surround and interact with the tumor, such as fibroblasts and immune cells, play a vital role in determining how the tumor behaves.

“A full understanding of tumor ecosystems includes the neoplastic cells—the ‘bad guys’ with mutations—as well as the normal host cells that are recruited or co-opted to help tumor cells survive and disseminate,” Coussens said.

Emerging classes of therapies, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors, leverage elements of the tumor microenvironment to kill cancer cells. In order to develop more drugs targeting these cancer support systems, researchers need to learn more about how tumors interact with their surroundings.

“I think the next years will bring a major focus on understanding communication networks between all the different types of cells in tumor ecosystems,” Coussens said, adding that a basic understanding of cell communications could produce benefits beyond the scope of cancer. “Basic discoveries about tumor ecosystems can have far-reaching impacts on autoimmune diseases, chronic inflammatory diseases, and how individuals respond to therapies that are designed to treat Alzheimer’s, for example,” she explained.

Coussens believes that many of these discoveries will be driven by the expanded use of technology and data science. Since the turn of the century, rapid advances in genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics have created an abundance of biological data from patients, animal models, and cell lines. Designing computational programs capable of integrating these data and determining how to analyze them in meaningful ways has been a constant source of innovation over the past 20 years.

Coussens emphasized that continued progress in this area could significantly shape basic research in the coming years.

“The biggest impact we’re seeing right now is with the emergence of technology development and computational data sciences,” Coussens said. “I think the greatest advances we will see over the next several years will be emerging out of team science embracing technology, data science, and biology.”

As technological advances spur more integration between different disciplines, Coussens predicts that collaboration will become more crucial than ever.

“Science has changed—we no longer do science in isolation,” she said. “The best science today, I think, comes out of multidisciplinary team science. I’m a biologist, but I now need to be able to communicate with data scientists, epidemiologists, and chemists.”

Coussens expressed that young investigators entering the field should consider this new paradigm when planning their training. “The more you can round out your education in a multidisciplinary way, the better. You need to be able to communicate your science with people who don’t necessarily speak your field’s language.”

Part of her advice hinged on trainees finding strong mentors who can help guide them toward these opportunities, especially as they recover from lost time and funding resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. “Invest your time and energy in identifying mentors who care about who you are and the trajectory of your career. Find mentors who you will grow to respect and love,” she said.

Overall, Coussens was optimistic about the state of basic research moving forward.

“The basic science discoveries we’re going to see in the next five years will reshape the medical landscape for years to come,” she said.

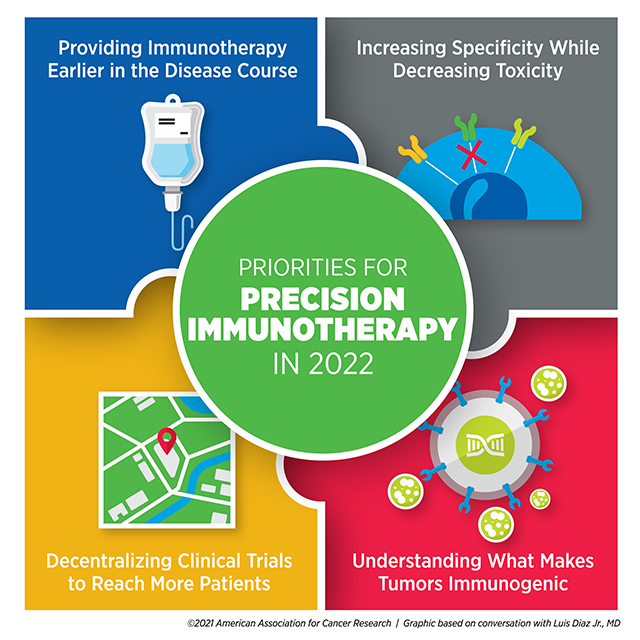

PRIORITIES FOR Precision Immunotherapy IN 2022

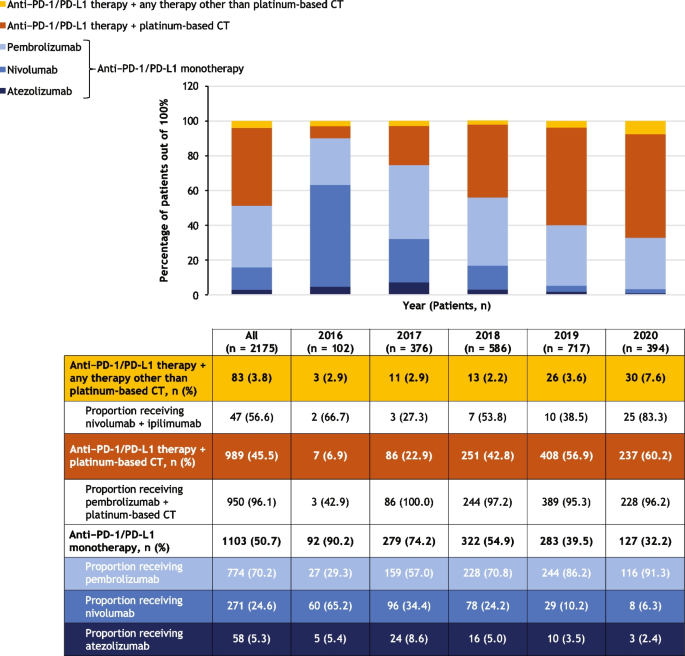

The art of deciding which cancer therapies to give a patient, based on their individual tumor characteristics, has evolved over the past several decades, according to Luis Diaz Jr., MD , head of Solid Tumor Oncology at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and a member of the National Cancer Advisory Board. Such decisions were first made based on protein markers expressed by the tumor, then by genetic changes in the tumor’s DNA. Now, Diaz said, a precise understanding of tumor characteristics can predict which patients may benefit most from immunotherapy.

“One example has been PD-L1 overexpression, either on the tumors themselves or on the surrounding cells,” Diaz said. “Another is mismatch repair deficiency, which seems to prime cells to become very sensitive to immunotherapy.”

This is just one of the ways that the fields of precision medicine and immunotherapy have grown to complement each other in recent years. As Diaz noted, antibodies targeting PD-1 or PD-L1 have become an effective therapy for patients whose tumors express these immunosuppressive markers.

The treatment of patients with CAR T cells—immune cells which are harvested from a patient’s body, engineered to target tumors, and returned to the patient’s bloodstream—represents an even more patient-specific approach to immunotherapy.

But these therapies are not appropriate for all cancer types, and many patients who receive these therapies eventually relapse, creating a need for the expansion of immunotherapy types and indications.

Diaz believes researchers can improve the efficacy of immunotherapy by offering it earlier in a patient’s course of treatment.

“In many cases, we’re testing new therapies on patients for whom all standard therapies have already failed,” he said. “As we move forward, we need to begin to treat earlier in the diagnosis.”

Diaz emphasized that treating advanced cancer poses far more challenges than intervening in early-stage disease or preventing tumor formation altogether. “If we can begin to bring targeted therapy and immunotherapy into the prevention space, I think we’ll see a profound impact,” he said.

A different approach to improving immunotherapy efficiency is to reach more patients by making cell-based immunotherapies, such as CAR T, effective against a broader range of tumor types, including solid tumors.

To overcome these hurdles, Diaz said, “The priority needs to be in maximizing specificity and minimizing toxicity.”

Solid tumors, Diaz explained, are often heterogeneous. An immune response against a single target may kill some of the tumor, but cancer cells that don’t express the target may continue to grow and evade the immune system. Researchers have designed CAR T cells that target multiple tumor cell markers, but more targets also increase the likelihood of harmful side effects.

“It’s a mathematical problem we can’t solve very easily,” Diaz said. “We need some clever new ideas.”

Boosting the number of people who receive immunotherapy also involves addressing accessibility issues, especially for patients in rural or underresourced communities. Diaz speculated that the increase in remote care options resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic might provide a blueprint for the decentralization of clinical trials, paving the way for large cancer centers to collaborate with community hubs.

He emphasized that one way to promote decentralization is to encourage more clinical trial ownership from clinicians rather than pharmaceutical companies. “I’d like to see our investigators becoming the initiators of more trials to be run at large cancer centers and elsewhere,” Diaz said.

He noted that clinical trial decentralization will pose some challenges, such as standardizing procedures and supplies and ensuring that quality does not suffer. However, he was optimistic that it would eventually improve care. “I think it will make clinical development move faster than it ever has before,” he said.

Targeting new populations and tumor types with immunotherapy, however, will only benefit patients whose tumors mount an immune response. Some tumors—deemed immunologically “cold”—expertly evade the immune system, and the mechanisms underlying that process are complex.

“We need a better understanding of what makes tumors immunogenic so we can harness that knowledge to make cancers more immunogenic,” Diaz said.

He noted that research into the interface between immune cells and cancer cells has done a great job of producing the therapies on the market today, but that advancing precision immunotherapy will require those efforts to continue.

“As exciting as everything is that we’re doing, we need to do so much more,” Diaz said. “What’s popular right now is probably only the tip of the iceberg.”

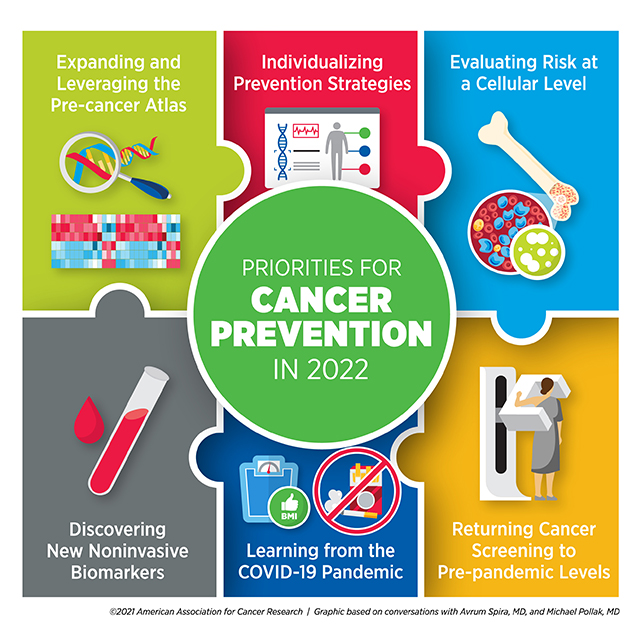

Priorities for Cancer Prevention in 2022

“The most transformative impact we could have on cancer care would be to prevent cancer from happening in the first place,” said Avrum Spira, MD , a professor of medicine, pathology and laboratory medicine, and bioinformatics at the Boston University School of Medicine and global head of the Lung Cancer Initiative at Johnson & Johnson.

Spira and his colleagues study how physicians can better detect early-stage lung cancer or signs of precancerous changes in the lungs. He also studies how to intervene in these early stages to prevent disease progression.

“Researchers have found molecular alterations in late-stage cancer and used that information to develop new targeted therapies and immunotherapies that are transforming the treatment of advanced-stage disease,” Spira said. “It’s absolutely critical to move that fundamental molecular understanding to early-stage and even premalignant disease.”

Understanding what drives benign cells into a tumorigenic state is an important component of this process, Spira emphasized. Drawing on the success of large-scale programs such as The Cancer Genome Atlas , the Human Cell Atlas , and the Human Tumor Atlas Network , dedicated to fully characterizing the blueprints of the human body, researchers have embarked on the development of a Pre-cancer Atlas .

“Within the Human Tumor Atlas Network, researchers are forming large coalitions for multiple different cancer types to develop a temporal and spatial atlas of the cellular and molecular changes associated with the transition of a premalignant lesion to a fully-blown invasive cancer,” Spira said. “I think, in 2022, we’re going to see a proliferation of those types of studies, generating a vast amount of cellular and molecular data from premalignant tissue across many cancer types.”

Spira believes such an atlas will benefit patients in two key ways: the development of biomarkers that can help predict which precancerous lesions will advance to cancer, and the identification of drug targets to stop the progression.

“For most cancer types, we don’t know what those early events are, and therefore, we have no effective way to intercept the disease process,” he said. “I think in 2022, we will begin to understand these events and gain unprecedented insight into targeted approaches aimed at intercepting premalignancy.”

Spira elaborated more on the need for biomarkers, which may not only identify patients at an elevated cancer risk but may also determine which patients with abnormal imaging results may need a biopsy. The most effective biomarkers, he stressed, would be the ones detectable via noninvasive tests.

“I’m excited about the future of blood-based tests looking at nucleic acids,” Spira said. “The technologies are evolving very rapidly to the point where they can now detect very small amounts of DNA or epigenetic changes that are circulating in the blood, and they can screen people across multiple cancer types.”

While blood-based liquid biopsies have attracted a great deal of attention in recent years, Spira also drew attention to other emerging noninvasive tests with the potential to have a significant impact on early cancer detection, such as urine markers of urologic cancer, stool markers of colon cancer, and nasal brushings to assess lung cancer risk.

Spira hopes these noninvasive tests can be integrated with each other and with imaging results to give the best possible assessment of a patient’s risk. “That’s a complicated space, but I think this convergent approach is one that will advance significantly in 2022,” he said.

Even noninvasive tests, however, can only benefit patients who are able to access them. Spira pointed out a few ways the field adapted during the COVID-19 pandemic that could continue to be leveraged moving forward.

“We need to find ways to get screening to patients as opposed to them having to come to the hospital,” Spira said. He highlighted advances such as remote clinical trial management, as well as mobile CT and radiology units, set up in large vans or trucks that can drive to various neighborhoods to perform screening. Used during COVID-19 to promote social distancing and minimize virus exposure, such units could be used in the future to help people catch up on screenings missed during the pandemic, especially in areas with poor health care access.

Spira also noted that the pandemic placed a spotlight on behavioral risk factors that increased COVID-19 susceptibility and the risk for severe disease, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, obesity, and physical inactivity. He pointed out that, often, these same behaviors contribute to cancer risk.

“This has become a teachable moment,” Spira said. “I think we can encourage the public to alter some cancer-causing behaviors that are also related to virus susceptibility.”

Michael Pollak, MD , a professor of oncology and medicine at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, who studies cancer prevention through the lens of reducing risk, also emphasized addressing lifestyle behaviors that affect multiple health conditions.

“An important trend for 2022 may be the concept of healthy lifestyle behaviors integrated across diseases,” Pollak said. “We have to recognize that some of the activities and lifestyles and approaches to cancer risk just contribute to overall good health.”

While many behavioral factors are known to broadly increase risk of several cancers, Pollak noted that risks vary in unique ways among different individuals.

“Oncologists are used to personalization of treatments,” he said. “We try to find out what treatment would be particularly useful for one patient as compared to their neighbor. In prevention, we may discover an analogy to that customization.”

He explained that an individual assessment of risk may make the message of behavioral intervention more personal. “If you hear your doctor saying that, in your particular case, the way your body is put together, your weight especially increases your risk for cancer, it may help motivate some people.”

Pollak believes risk assessment can be further personalized beyond the level of the individual, down to the level of discrete cell types. “We’re used to thinking of a person’s cancer risk as if the person was homogeneous, but carcinogenesis takes place at the cellular level,” he said. “We need to know what’s going on differently in the different cells that might determine risk on a per-cell basis.”

Pollak mentioned the Pre-cancer Atlas as an important vehicle for realizing this goal. “With the Pre-cancer Atlas, we’ll learn more about the cellular composition and subcellular features that lead to carcinogenesis,” he said, noting that such a granular understanding of tumor formation could pave the way for improved therapies.

“We really won’t be able to prevent every cancer, but even if we confine our goals to preventing the subset of cancers that are preventable, that’s estimated to be about half of all cancers,” Pollak concluded. “Even acknowledging the limitations, the potential gains are absolutely enormous.”

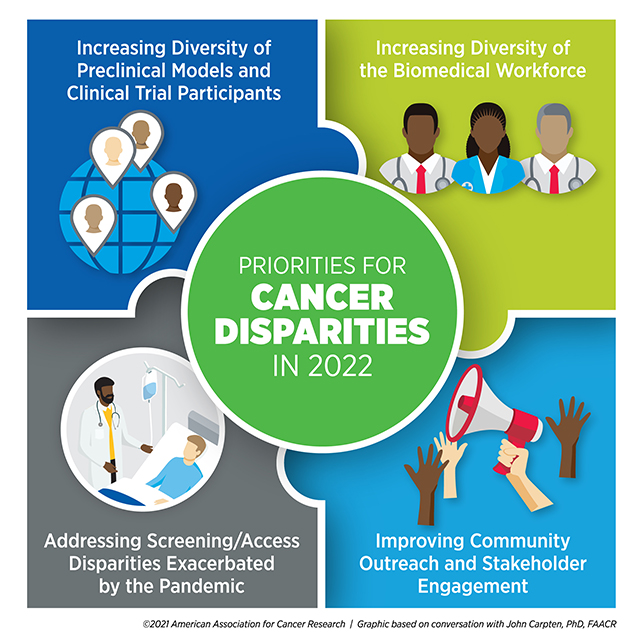

Priorities for Cancer Disparities in 2022

The past two years have presented health care challenges beyond COVID-19, encompassing financial and access-related struggles that affected many facets of medicine, including cancer care. Many individuals have had to delay routine cancer screenings, alter the course of treatment, or miss follow-up appointments as a result of the pandemic.

Such problems were more pronounced in some communities than others.

“The pandemic has definitely impacted our opportunities to move forward toward eliminating disparities in all areas of cancer research,” said John Carpten, PhD, FAACR , chair of the department of Translational Genomics at the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine and chair of the National Cancer Advisory Board. “As we consider gaps in cancer screening and cancer diagnosis, many challenges were further exacerbated in underrepresented minority communities during the pandemic.”

Carpten also pointed out the disproportionate challenges minority cancer researchers faced during COVID-19. “Many underrepresented minority investigators, who may have already had challenges in terms of access to funding, were also impacted severely by the pandemic,” he said. “This is especially true for early-stage investigators and postdoctoral fellows who were unable to be in their laboratories to perform research.”

Although the issue of lost time and funding due to the pandemic may be difficult to solve, Carpten believes that other initiatives to support underrepresented minority researchers—especially trainees and early-career investigators—will positively influence health disparities research in 2022.

Carpten specifically listed diversifying the biomedical workforce as a key priority for tackling health disparities. “Increasing underrepresented minority faculty members will increase the number of mentors who will then be able to train more underrepresented minorities and fellows,” he said.

He mentioned the National Institutes of Health (NIH) FIRST program , a funding opportunity provided to institutions to promote the hiring of early-career investigator cohorts from diverse backgrounds in support of their career development. Providing a supportive environment and sufficient resources to these investigators, Carpten said, can make significant strides toward ensuring a successful career trajectory in academic research.

“We believe that this is going to be a huge component in the growth of underrepresented minorities in the area of biomedical research, specifically cancer research,” he said.

Encouraging diversity of researchers, however, is only one step where meaningful interventions can occur. Another is the broader inclusion of diverse patients and samples in cancer research, especially of patients recruited into clinical trials.

“We need to understand the broader impact of new therapies for all people, preferably prior to approvals, to ensure that we have the most accurate picture relative to effectiveness and toxicity profiles across representative groups of patients,” Carpten said.

Diversity in preclinical studies, including patient-derived samples, genetic data, and model systems, is also key to understanding the biological basis of cancer health disparities.

“Whether it’s understanding the influence of genetic factors on cancer risk or understanding how collections of mutations that occur in cancer cells differ across individuals from different groups, it will be very important for us to continue increasing representation of the reagents, models, and data that we use,” Carpten said.

“Ensuring that we understand how biological changes impact cancer initiation, progression, and growth across an array of models will provide additional information so that we can really capture the full complexity of cancer,” he added.

Carpten also encourages working to address the cultural, social, and access-related issues underlying cancer health disparities by striving harder to engage with the community.

“We need to advance our relationships with various stakeholders, especially in terms of community engagement, outreach, and involvement,” Carpten said. “If we don’t build better relationships with the community, get their feedback, understand their issues, and work together to address them, I think we’ll continue to have challenges.”

As observed during the pandemic , improving community engagement can help health care providers build trust with their patients, bring care to broader geographic areas, and better understand the needs of the populations disparities researchers are working to serve.

“I really look forward to working with my colleagues in academia, industry, and the government, but most importantly, with our colleagues in the community,” Carpten concluded. “Their voice really needs to be heard and will be key in achieving cancer health equity.”

- About This Blog

- Blog Policies

- Tips for Contributors

Arming the Body to Fight Ovarian Cancer

Examining Cancer Health Disparities in the LGBTQ Community

AACR Annual Meeting 2019: Preclinical Steps Toward a Cancer Preventive Vaccine for Lynch Syndrome

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Join the Discussion (max: 750 characters)...

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Thank you so much for sharing such useful information over here with us. This is really a great blog have you written. I really enjoyed reading your article. I will be looking forward to reading your next post. https://atulkulkarnidotblog.wordpress.com/ https://atulkulkarnidotblog.blogspot.com/ https://atulblog123.tumblr.com/

I was distraught when I found out that my grandmother was diagnosed with cancer. I appreciate that this post emphasized that it is important to get the right kind of treatment, to target the cells precisely. I think I will advise my mother to seek the right kind of treatment by speaking with professional oncologists.

This is very informative blog about Cancer research forecast, I will definitely share this content with others.

- Experts Forecast Cancer Research and Treatment...

- Executive Summary

- Experts Forecast 2024, Part 1: Advances in...

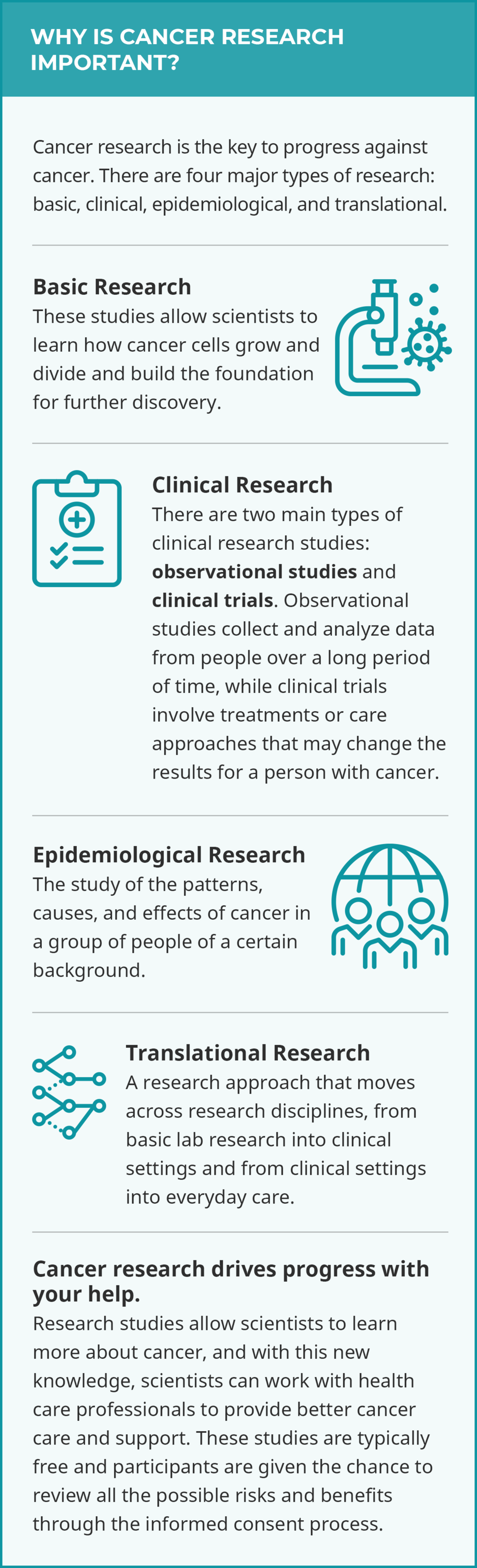

What Are Cancer Research Studies?

What is cancer research and why is it important.

Research is the key to progress against cancer and is a complex process involving professionals from many fields. It is also thanks to the participation of people with cancer, cancer survivors, and healthy volunteers that any breakthroughs go on to improve treatment and care for those who need it.

Cancer research studies may lead to discoveries such as new drugs to treat cancer, new therapies to make symptoms less severe, or lifestyle changes to reduce the chances of getting cancer.

Cancer research may also address big picture questions like why cancer is more prevalent in certain populations or how doctors can make existing cancer detection tools more effective in health care settings.

These discoveries can help people with cancer and their caregivers live fuller lives.

Who should join cancer research studies?

When you choose to participate in a research study, you become a partner in scientific discovery. Your generous contribution can make a world of difference for people like you.

As scientists continue to conduct cancer research, anyone can consider joining a research study. The best research includes everyone, and everyone includes you.

Your unique experience with cancer is incredibly valuable and may help current and future generations lead healthier lives.

When more people of all different races, ethnicities, ages, genders, abilities, and backgrounds participate, more people benefit.

It is important for scientists to capture the full genetic diversity of human populations so that the lessons learned are applicable to everyone.

What are the types of cancer research studies?

See below for definitions on the four major types of research and their subtypes:

- basic research

- quality of life/supportive care

- natural history

- longitudinal

- population-based

- epidemiological research

- translational research

Basic Research

Basic cancer research studies explore the very laws of nature. Scientists learn how cancer cells grow and divide, for example, by growing and testing bacteria , viruses , fungi , animal cells, and human cells in a lab. Scientists also study, for example, the genes that make up tumors in mice and rats in the lab. These experiments help build the foundation for further discovery.

Why Participate in a Clinical Trial?

Get information on how to evaluate a clinical trial and what questions to ask.

Clinical Research

Clinical research involves the study of cancer in people. These cancer research studies are further broken down into two types: clinical trials and observational studies .

- Treatment trials test how safe and useful a new treatment or way of using existing treatments is for people with cancer. Test treatments may include drugs, approaches to surgery or radiation therapy , or combinations of treatments.

- Prevention trials are for people who do not have cancer but are at a high risk for developing cancer or for cancer coming back. Prevention clinical trials target lifestyle changes (doing something) or focus on certain nutrients or medicines (adding something).

- Screening trials test how effective screening tests are for healthy people. The goal of these trials is to discover screening tools or methods that reduce deaths from cancer by finding it earlier.

- Quality-of-life/supportive care tests aim to help people with cancer, as well as their family and loved ones, cope with side effects like pain, nutrition problems, nausea and vomiting , sleeping problems, and depression . These trials may involve drugs or activities like therapy and exercising.

Find Observation Studies >

View a studies that are looking for people now.

- Natural history studies look at certain conditions in people with cancer or people who are at a high risk of developing cancer. Researchers often collect information about a person and their family medical history , as well as blood, saliva, and tumor samples. For example, a biomarker test may be used to get a genetic profile of a person’s cancer tissue. This may reveal how certain tumors change over the course of treatment .

- Longitudinal studies gather data on people or groups of people over time, often to see the result of a habit, treatment, or change. For example, two groups of people may be identified as those who smoke and those who do not. These two groups are compared over time to see whether one group is more likely to develop cancer than the other group.

- Population-based studies explore the causes of cancer, cancer trends, and factors that affect cancer care in specific populations. For example, a population-based study may explore the causes of a high cancer rate in a regional Native American population.

Epidemiological Research

Epidemiological research is the study of the patterns, causes, and effects of cancer in a group of people of a certain background. This research encompasses both observational population-based studies but also includes clinical epidemiological studies where the relationship between a population’s risk factors and treatments are tested.

Translational Research

Translational research is when cancer research moves across research disciplines, from basic lab research into clinical settings, and from clinical settings into everyday care. In turn, findings from clinical studies and population-based studies can inform basic cancer research. For example, data from the genetic profile of a tumor during an observational study may help scientists develop a clinical trial to test which drugs to prescribe to cancer patients with specific tumor genes.

Monica Bertagnolli, Director, NIH; former director, NCI; cancer survivor

Participation in Cancer Research Matters

I am so happy to have the opportunity to acknowledge the courage and generosity of an estimated 494,018 women who agreed to participate in randomized clinical trials with results reported between 1971 and 2018.

Their contributions showed that mammography can detect cancer at an early stage, that mastectomies and axillary lymph node dissections are not always necessary, that chemotherapy can benefit some people with early estrogen receptor–positive, progesterone receptor–positive, HER2-negative breast cancer but is not needed for all, and that hormonal therapy can prevent disease recurrence.

For just the key studies that produced these results, it took the strength and commitment of almost 500,000 women. I am the direct beneficiary of their contributions, and I am profoundly grateful.

The true number of brave souls contributing to this reduction in breast cancer mortality over the past 30 years? Many millions. These are our heroes.

— From NCI Director’s Remarks by then-NCI Director Monica M. Bertagnolli, M.D., at the American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting, June 3, 2023

Advertisement

The Supportive Care Needs of Cancer Patients: a Systematic Review

- Open access

- Published: 25 January 2021

- Volume 36 , pages 899–908, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Madeleine Evans Webb 1 ,

- Elizabeth Murray ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8932-3695 2 ,

- Zane William Younger 2 ,

- Henry Goodfellow 2 &

- Jamie Ross 2

8266 Accesses

33 Citations

4 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Cancer, and the complex nature of treatment, has a profound impact on lives of patients and their families. Subsequently, cancer patients have a wide range of needs. This study aims to identify and synthesise cancer patients’ views about areas where they need support throughout their care. A systematic search of the literature from PsycInfo, Embase and Medline databases was conducted, and a narrative. Synthesis of results was carried out using the Corbin & Strauss “3 lines of work” framework. For each line of work, a group of key common needs were identified. For illness-work, the key needs idenitified were; understanding their illness and treatment options, knowing what to expect, communication with healthcare professionals, and staying well. In regards to everyday work, patients wanted to maintain a sense of normalcy and look after their loved ones. For biographical work, patients commonly struggled with the emotion impact of illness and a lack of control over their lives. Spiritual, sexual and financial problems were less universal. For some types of support, demographic factors influenced the level of need reported. While all patients are unique, there are a clear set of issues that are common to a majority of cancer journeys. To improve care, these needs should be prioritised by healthcare practitioners.

Similar content being viewed by others

Survivorship concerns among individuals diagnosed with metastatic cancer: Findings from the Cancer Experience Registry

Rachelle S. Brick, Lisa Gallicchio, … Melissa F. Miller

Spiritual care interventions in nursing: an integrative literature review

Mojtaba Ghorbani, Eesa Mohammadi, … Monir Ramezani

Network analysis used to investigate the interplay among somatic and psychological symptoms in patients with cancer and cancer survivors: a scoping review

G. Elise Doppenberg-Smit, Femke Lamers, … Joost Dekker

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over 42 million people worldwide are currently living with cancer [ 1 ]. A cancer diagnosis often results in biographical disruption [ 2 ] and distress [ 3 ], sometimes lasting years post-treatment [ 4 , 5 ]. As survival rates continue to increase, more individuals will have to live with the long-term implications of cancer. It is therefore important that the support offered to cancer patients improves to meet this growing demand.

Cancer care pathways are often spread across multiple facilities and delivered by healthcare practitioners (HCP), which make it challenging for a patient’s wider support needs to be met. This has an impact on patient wellbeing [ 6 ] and survival outcomes [ 7 , 8 ]. Many studies focus on the needs of specific patient groups, defined by diagnosis, treatment or demographics, but there is no broad consensus on how common or dissimilar patients’ supportive care needs are across types of cancer and populations. The aim of this study was to synthesise existing data on the support needs of cancer patients across populations. Identifying the common underlying needs of cancer patients, as well as needs that are specific to a patient’s diagnosis or background, will help HCPs provide comprehensive support more efficiently.

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria: Any patient undergoing treatment for any form of cancer. Patients in remission or recovery were eligible only if they had not been in remission for longer than 5 years, a key milestone in cancer survivorship [ 9 ].

Intervention and Comparator

Patients that had received any form of treatment, be it curative or palliative, could be included. As this review was not assessing the effectiveness of an intervention program, there was no appropriate comparator or control group.

The primary outcome was the identification of any supportive care needs, categorised into emotional, informational, spiritual, social or “other”. Needs could be specifically identified, or could be inferred from reported distress, e.g. patients reporting high levels of loneliness would be categorised as having an emotional need.

Inclusion criteria: Any study design which included collection of primary data, quantitative or qualitative, was eligible for inclusion.

Exclusion criteria: Papers which did not include new primary data (e.g. reviews, meta-analyses, editorials), had not been peer reviewed or were not available in English.

The search strategy was the keywords: [emotional need] or [spiritual need] or [social need] or [emotional need] AND [Neoplasm(s)] either appearing in the title, abstract, subject heading, keyword heading, protocol supplementary concept, rare disease supplementary concept or as a unique identifier.

The search was carried out on PsycInfo, Embase and Medline databases, on 24 April 2018. This selection was based on a review of which databases have the highest recall rate, while also needing to produce a manageable number of results [ 10 ].

Reference lists of included papers were searched for potentially eligible studies.

Study Selection

Titles and abstracts were screened against the inclusion/exclusion criteria, and 10% of papers were also screened by a second author. For any paper that could not be confidently excluded, the full paper was read to determine whether it should be included. There was 100% agreement between the screeners about which papers should be excluded.

Data Extraction and Management

Data were extracted into an extraction form, which was piloted and refined. Data extracted from each paper were as follows: title, year of publication, country of study setting, study design, population studied, methods of data collection and analysis and results. The needs identified in each paper were classified as informational, emotional, spiritual, social or other. For quantitative data, scores or rankings for each need were recorded, along with whether needs differed between sub-groups. For qualitative data, overarching themes, subthemes and illustrative quotes were extracted.

Data Synthesis

Data were analysed using a narrative synthesis method [ 11 ]; this allowed for the synthesis of qualitative and quantitative data and analysis of whether medical or demographic factors shaped patient needs [ 11 , 12 ].

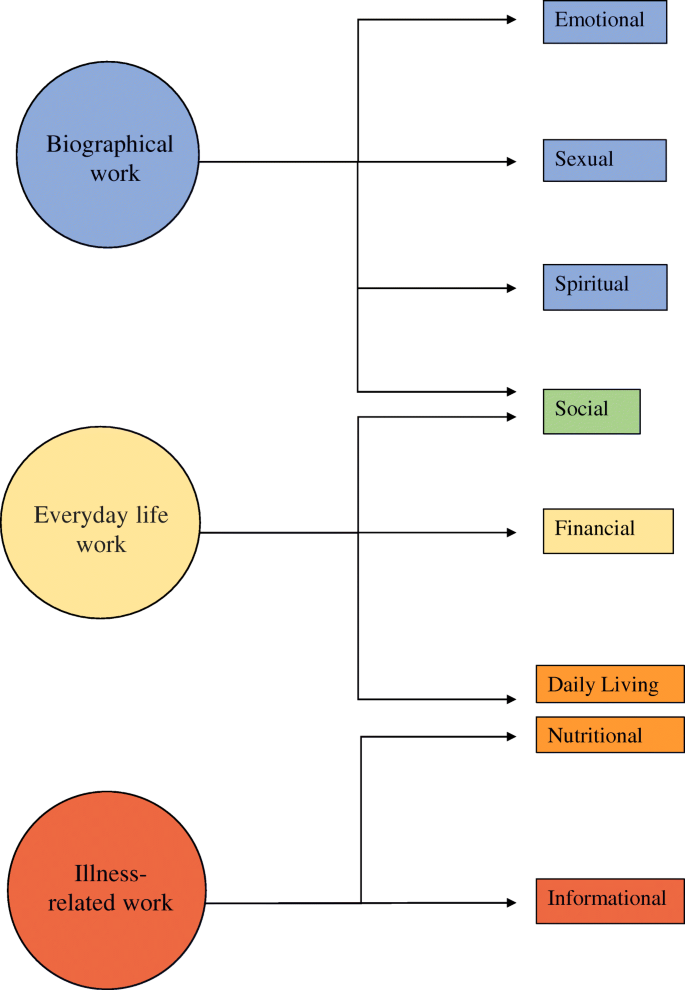

The first step was to group the needs identified in the papers into the categories specified in the primary literature. Seven categories of need were identified in the included papers: emotional, sexual, spiritual, social, financial, daily living, nutritional and informational. The second step was to map these categories onto the Corbin & Strauss “Three lines of work” model of chronic disease management. The model identifies three types of work associated with managing a long-term condition: illness-related work, everyday life work and biographical work [ 13 ]. Within each group, the relative importance and prevalence of all the needs identified in the primary literature were compared to identify which were the most common and urgent.

Our goal was to clarify the commonality of the experience of “cancer”, irrespective of the type of cancer, thus providing an overview of the common and important support needs faced by people with cancer, and hence an understanding of where supportive care is most needed. In instances where there was conflicting evidence in the primary literature on the importance of a specific need, clinical and demographic differences between study populations were reviewed in order to understand the potential reasons for this conflict.

The Corbin & Strauss model was chosen because the categories of need identified in the primary literature clearly corresponded to the types of work in the model (Fig. 2 ). Using the model as a framework to synthesise the data allowed us to compare the relative importance of needs from different categories that fell under the same type of work. The simplicity of the model meant it could be consistently applied to needs that were identified and categorised using a number of different methodologies.

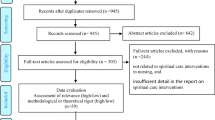

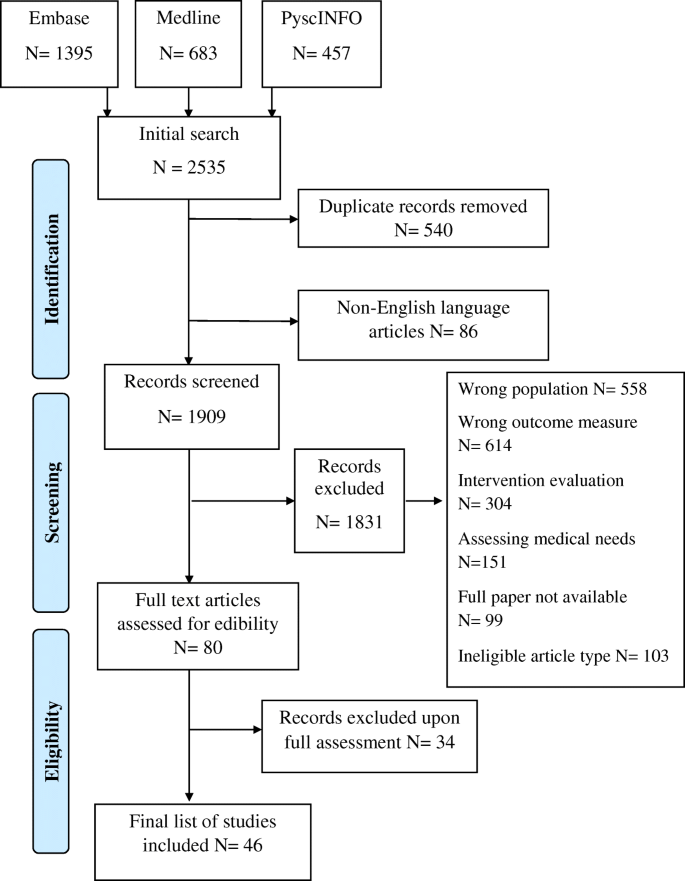

In total, 2535 papers were identified, and 540 duplicates were removed. After screening against the criteria, 1829 papers were removed, and the remaining 80 papers were read in full (Fig. 1 ). Forty-six papers were found to be eligible for inclusion in this review.

PRISMA flow diagram of the paper identification process

Study Characteristics

Of the 46 studies, 34 were quantitative, 10 were qualitative and two were mixed methods. Study population sizes ranged from 7 to 1059 participants. Fifteen papers focused on patients with a specific type of cancer, with breast and colorectal cancer being the most common. Three studies looked at patients from specific ethnic backgrounds. Eight papers focused on patients receiving a specific form of care/treatment. Three papers focused on children or young adults. Three papers looked at adults within specific age groups. Eleven studies only included patients at a certain stage of cancer or time since diagnosis. Thirty-nine studies took place in high-income countries, 6 were from middle income countries and 1 took place in a low-income country.

Needs of Cancer Patients

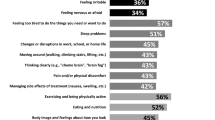

Thirty-two papers mentioned informational needs, 31 mentioned emotional needs, 24 mentioned spiritual needs and 19 mentioned social needs. Thirty-five papers mentioned needs in at least one of these other categories: nutritional, sexual, daily living or financial.

The resulting needs identified were grouped according to the different forms of chronic disease “work” defined by the Corbin & Strauss framework (Fig. 2 ).

Illustration of how the different domains of need identified fit into Corbin and Strauss’ 3 lines of work model of managing chronic illness

Illness-Related Work

Illness-related work, defined by Corbin & Strauss, is “the tasks of controlling symptoms; monitoring, preventing crises; carrying out regimens and managing limitations of activity” [ 13 ]. The central goal of illness-related work for patients is to understand their illness and treatment, and subsequently the need for information is consistently reported as a high priority [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ]. The only paper that did not find a high level of informational need specifically measured unmet need [ 30 ].

Most frequently patients wanted to know what treatment they were receiving and how it worked [ 20 , 26 , 27 , 29 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 ], why that treatment had been selected, its effectiveness and its pros and cons [ 14 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 26 , 35 ]. Patients also frequently searched for more specific information about their diagnosis and prognosis [ 15 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 29 , 31 , 33 , 34 ].

Patients wanted to know what to expect from their illness and treatment [ 15 , 16 , 31 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 37 , 38 ] (Box 1). This included knowing about the chance of a relapse [ 26 ], the length of their hospital stay [ 32 ] and when their life would return to “normal” [ 26 , 31 , 33 , 39 ]. One paper reported that being given “vague” answers by HCPs frustrated patients [ 38 ].

In regard to treatment, patients most often wanted to know what the possible side effects were [ 16 , 18 , 21 , 22 , 25 , 27 , 31 , 33 , 37 , 38 , 40 , 41 ] and how they could manage or relieve them [ 14 , 17 , 19 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 26 , 31 , 33 , 35 , 42 , 43 ]. The importance of this information may depend on the stage of the patient’s treatment, as patients receiving follow-up or palliative care placed less importance on symptom management [ 25 , 27 ].

Wanting to minimise the impact of side effects speaks to a commonly reported desire among patients to be as healthy as possible [ 14 , 15 , 18 , 19 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 33 , 38 , 39 , 40 ]. This aim is also seen in the nutritional needs of patients [ 16 , 20 , 33 , 40 , 41 , 44 ]. Rather than receiving generic information about healthy diets, patients wanted more specific advice around foods that could aid recovery or minimise side effects [ 16 , 40 , 41 ]. Nutritional needs had an outsized importance in studies involving Native American patients and colorectal cancer patients [ 16 , 40 ]. For colorectal cancer patients, nutritional needs are likely higher as their cancer directly affects their digestive system. Within the Native American population, there was a strong interest in information about traditional foods, possibly due to culturally specific reasons [ 40 ].

Generally, patients wanted their test results as soon as possible [ 21 , 22 , 24 , 27 , 33 , 43 ] and wanted the meaning of the results explained to them [ 21 , 22 , 26 , 34 , 43 ]. The importance of this information to patients could be due to a desire to have some say in the treatment they are given [ 18 , 33 , 34 , 45 ], although the level of interest in alternative treatments varied significantly [ 14 , 18 , 24 , 40 , 44 ] (Box 2). The only study where information about tests was less important involved newly diagnosed patients [ 18 ].

The final area of illness-related work highlighted by this review was communication. Patients wanted to be able to communicate with their HCPs [ 18 , 27 , 34 , 40 ] but often felt unsure of when or who to direct questions to [ 24 , 26 , 35 , 36 , 38 ]. Having a single HCP who they could talk to about all aspects of treatment was a high priority [ 19 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 28 , 43 ]. Less important was the need to talk to a professional counsellor [ 25 , 27 , 36 , 43 ].

Although a general need for information was consistent across all included studies, not all patients wanted a high volume of information. A significant minority of patients only wanted to know essential information or did not want to receive bad news [ 29 , 31 , 46 ]. Age may play a role in this dynamic, as multiple papers reported older people wanted less information [ 14 , 15 , 20 , 22 , 25 , 26 , 31 , 44 ], while only a couple found no relationship [ 28 , 34 ]. Timing could also be a factor, as some patients felt the amount of information received when diagnosis was overwhelming and preferred receiving information as it became relevant [ 34 , 37 , 39 , 41 ].

Everyday Life Work

This area of need encapsulates “the daily round of tasks that helps keep a household going”, which includes the practical tasks involved in managing an illness, along with trying to maintain the structure of life pre-diagnosis [ 13 ]. The most frequently reported social needs were about patients’ concern for their family [ 17 , 20 , 21 , 26 , 39 , 46 , 47 , 48 ]. The importance of maintaining relationships with their partner, children or friends were all mentioned [ 15 , 29 , 37 , 42 , 45 , 47 ], although notably not among patients with incurable cancer [ 27 ]. There was no consensus on whether patients wanted to discuss their cancer with loved ones; some papers found this to be highly important, others did not [ 20 , 31 , 36 , 42 , 49 ]. While there were no clear demographic or medical factors connected to this variation, Kent (2013) reported that patients whose existing relationships had been heavily affected by their diagnosis were more likely to want to talk about cancer [ 49 ].

Patients wanted to live a life they consider “normal”, reflected by the importance placed on daily living needs. The most common difficulties patients faced were coping with a lack of energy [ 17 , 19 , 21 , 27 , 28 , 30 , 36 , 38 , 43 ] and wanting to do the things they used to do [ 19 , 21 , 26 , 28 , 31 , 39 ] (Box 3). Patients placed a high value on socialising and leisure time [ 15 , 26 , 32 , 45 ] and reported a fear of being isolated or abandoned [ 16 , 18 , 20 ]. The importance of maintaining a job was influenced by age, with younger patients being more interested in how cancer will affect their career and their employment rights [ 15 , 18 , 20 , 26 , 29 , 33 , 39 , 42 ].

The final practical need identified was financial, though the level of need was highly dependent on location. Patient populations with greater access to healthcare placed lower importance on financial needs [ 25 , 27 , 29 , 30 , 33 ] (Box 4). The needs in these groups related to wanting financial stability and informational support [ 45 , 50 ], with low levels of interest in economic aid [ 34 ]. Patients in countries with more limited access to healthcare reported higher levels of financial stress and reliance on family for monetary support [ 32 , 46 ]. This was true in all US-based studies, apart from one in which the mean income of participants was high [ 18 , 20 , 24 , 28 ]. For these populations, financial concerns included managing bills [ 18 , 24 ], bankruptcy assistance [ 18 ], paying for care [ 20 , 32 , 46 ] and homelessness [ 46 ]. A few financial needs were common across healthcare systems, being able to maintain a basic standard of living [ 27 , 30 , 45 , 46 ] and helping understanding financial systems and resources [ 18 , 25 , 26 , 34 ], though again the level of importance varied.

Biographical Work

Biographical work is defined as “the work involved in defining and maintaining an identity” [ 13 ]. This involves coming to terms with and contextualising a diagnosis within a persons’ identity [ 42 , 45 ]. Patients wanted to be treated as individuals [ 16 , 19 , 21 , 22 , 34 ], be reassured [ 19 , 34 ], have their feelings acknowledged [ 19 , 22 ], be respected [ 34 , 45 ] and have their dignity preserved [ 47 ] (Box 5).

Biographical work includes dealing with the emotional impact of cancer. Feelings of despair or depression were common [ 19 , 21 , 23 , 28 , 30 , 42 , 51 , 52 ], as well as distress and anxiety [ 16 , 21 , 28 , 30 , 35 , 38 , 43 ]. Patients also reported a range of fears including cancer itself [ 17 , 21 , 23 , 31 , 43 , 51 ], their treatment [ 35 , 37 ], dying [ 17 , 19 , 42 , 52 ] and pain [ 27 ]. Physical changes also negatively affected patients’ sense of self [ 26 , 27 , 29 , 30 , 38 , 42 , 45 , 46 , 47 ]. Consequently, the need for relaxation and stress management was high [ 23 , 24 , 33 , 48 , 52 ].

Patients struggled to deal with the uncertainty [ 15 , 17 , 19 , 28 , 30 , 42 , 43 , 46 , 51 ] and expressed a desire for more control [ 17 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 27 , 28 , 30 , 42 , 43 , 53 ]. To cope, patients placed a lot of importance on receiving support from loved ones [ 14 , 18 , 32 , 35 , 36 , 42 , 51 ]. However, this directly conflicted with their fear of being a burden and a perceived pressure to “stay strong” [ 20 , 27 , 37 , 45 , 46 , 51 , 53 ] (Box 6). Other patients were identified as a source of support for some [ 18 , 34 , 37 , 49 , 52 ], but others, especially those who were receiving follow-up or palliative care, were less interested in talking to other patients [ 25 , 35 , 45 , 47 ]. This aligns with a reported need among terminal cancer patients to discuss things other than illness [ 54 ].

Sexuality is another part of identity that can be impacted by cancer. Patients wanted to know how cancer would impact their sex drive, sexuality [ 14 , 17 , 20 , 26 , 29 ] and their intimate relationships [ 14 , 17 , 30 , 31 ] but often felt uncomfortable discussing these needs with their HCPs [ 14 , 18 , 20 , 26 ] (Box 7). When ranked alongside other needs, sexuality was reported to be of lesser importance to most patients [ 17 , 19 , 21 , 22 , 35 , 42 , 43 ], apart from prostate cancer patients, who reported the impact on their sex drive and sexual activity as some of the most significant changes they faced [ 14 , 30 , 38 ] (Box 7). Higher sexuality-related needs were also identified in patients with colorectal and breast cancer, although not at the same level [ 22 , 30 ]. Of the papers that looked, five out of the six studies found a relationship between age and importance of sexual identity, with younger patients having a greater need for information on sex [ 17 , 22 , 26 , 31 ] and individuals over 40 wanting more guidance on fertility [ 18 ]. One study involving younger patients did report limited interest in sexuality; however, the majority of patients were under 18 and therefore were less likely to be sexually active [ 42 ].

Much like with sexual identity, patients’ spiritual needs were not highly important when ranked alongside other domains [ 23 , 24 , 27 , 28 , 33 , 34 , 40 , 45 ], but papers that focused solely on spirituality reported widespread need [ 47 , 48 , 52 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 ]. There was no consensus on the importance of accessing religious resources, some papers reported a strong need for religious support [ 23 , 32 , 45 , 55 , 56 , 59 ], but more papers reported low levels of interest [ 24 , 28 , 33 , 48 , 51 , 52 , 54 , 57 , 60 ]. In line with this, the most commonly reported spiritual needs were not explicitly religious. This included maintaining a sense of calm [ 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 52 , 53 , 55 , 56 , 58 , 60 ], staying positive or hopeful [ 23 , 24 , 32 , 45 , 47 , 48 , 57 , 58 , 59 ] and being able to appreciate or find meaning in life [ 32 , 45 , 47 , 48 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 59 , 60 ]. Generally, there was little reported interest in discussing death or dying [ 23 , 24 , 27 , 42 , 45 , 48 , 52 , 60 ] or making sense of why this happened [ 34 , 55 , 56 , 57 ]. Much like the importance of family relationships in everyday work, being with loved ones was important for patients’ spiritual wellbeing [ 47 , 51 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 60 ]. However, some patients reported that being part of a religious community gave them similar support [ 46 , 51 , 53 , 55 , 60 ].

The most commonly reported religious need for patients was to pray or be prayed for [ 32 , 46 , 48 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 59 ]. The fact that prayer was also important for non-religious participants suggests that it may be seen as a spiritual practice for some patients. A small number of papers reported that having a relationship with God was important to patients [ 15 , 48 , 56 , 57 , 59 ], with some patients viewing God as a saviour from illness [ 40 , 46 , 59 ], while others felt that God caused their illness as punishment or as a test of faith [ 46 , 47 , 51 ] (Box 8).

Cultural factors may also influence spiritual needs. The afterlife was found to be an important concern for some patients [ 52 , 53 , 55 ], but not if their culture had little belief in the concept [ 47 ]. In the same way, having a legacy was a key need in one paper due to the importance of continuity after death in that culture [ 53 ].

This is the first review to synthesise data about cancer patients’ supportive needs across all populations and cancer types. There was remarkable consistency in the needs identified, and these were well explained by the Corbin & Strauss model of managing a chronic condition [ 13 ]. Almost all studies confirmed patients’ need for high-quality, comprehensible and timely information about their illness, treatments and how best to manage their symptoms. Such information was necessary for patients to undertake illness-related, everyday living and biographical work. In addition, patients needed support in dealing with emotional issues, including existential uncertainty, changing relationships with friends and family and practical support with everyday tasks.

Previous Literature

This review confirms the findings of previous reviews focused on specific types of need or specific populations. The most common needs identified as illness-related work in this study correspond to key informational needs highlighted in previous reviews [ 61 , 62 ]. The spiritual needs discussed have also been found to be key in improving psycho-spiritual wellbeing in other research [ 63 ]. While our review did not assess the ability of current care models to meet these needs, it is noteworthy that the key needs we identified have been found to frequently go unmet in other research [ 64 , 65 ].

Strengths and Limitations

The main strength of this study is its inclusive nature, looking across all populations and all types of cancer. This, combined with the theoretical underpinning and use of the Corbin & Strauss model, provides reassurance about the overall transferability of these findings to other clinical populations.

The main limitation pertains to the scope of the primary literature, with most of the studies coming from high-income countries, and only 7 papers from low- or middle-income countries. While the nature of patients’ financial needs were clearly dependent on country, setting may also influence other needs in less direct ways, limiting how universal the findings are. Additionally, the majority of studies used opportunistic sampling so may not accurately capture the needs of the general cancer population. Most included studies were not longitudinal and therefore could not analyse how patients’ concerns changed over time. Finally, potentially relevant demographic information was not always collected. For example, only one of the papers that examined sexuality collected information about sexual orientation, and only a couple of studies that measured financial need recorded socioeconomic status.

Conclusions

This review highlights a number of underlying issues that affect cancer patients. These findings are consistent with the previous literature and fit well with multiple chronic illness frameworks, which suggests that they are robust enough to inform best practice. The most common needs identified support the argument for empowering people with cancer through a patient-centred form of care.

Priorities for practice should be to ensure patients understand their illness and what they can expect throughout their treatment pathway. Supportive care should work to enable patients to live a life they recognise as “normal” and help them maintain their closest relationships. HCPs should ensure that patients always feel that they are being treated as individuals and know who to go to when they have questions. These key needs should be addressed as a first step to provide a strong basis of care before providing more individualised support.

Further research should focus on how to ensure these needs are addressed effectively. Evaluation of supportive care interventions should remain focused on the experiences of patients to allow them to have a voice in their care. Additional research on when different needs arise over the disease progression would help ensure that resources are provided only when needed.

McGuire S (2016) World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer, WHO Press, 2015. Oxford University Press, Geneva, Switzerland

Google Scholar

Park CL, Zlateva I, Blank TO (2009) Self-identity after cancer: “survivor”, “victim”, “patient”, and “person with cancer”. J Gen Intern Med 24(2):430–435

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Piantadosi S (2001) The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psycho-oncology. 10(1):19–28

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Ferrell BR, Dow KH, Leigh S, Ly J, Gulasekaram P (1995) Quality of life in long-term cancer survivors. In: Oncology nursing forum

Stein KD, Syrjala KL, Andrykowski MA (2008) Physical and psychological long-term and late effects of cancer. Cancer. 112(S11):2577–2592

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Li HW, Lopez V, Chung OJ, Ho KY, Chiu SY (2013) The impact of cancer on the physical, psychological and social well-being of childhood cancer survivors. Eur J Oncol Nurs 17(2):214–219

Kroenke CH, Kubzansky LD, Schernhammer ES, Holmes MD, Kawachi I (2006) Social networks, social support, and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol 24(7):1105–1111

Brown KW, Levy AR, Rosberger Z, Edgar L (2003) Psychological distress and cancer survival: a follow-up 10 years after diagnosis. Psychosom Med 65(4):636–643

Welch HG, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S (2000) Are increasing 5-year survival rates evidence of success against cancer? Jama. 283(22):2975–2978

Bramer WM, Rethlefsen ML, Kleijnen J, Franco OH (2017) Optimal database combinations for literature searches in systematic reviews: a prospective exploratory study. Systematic reviews 6(1):245

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M et al (2006) Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme Version 1:b92

Barnett-Page E, Thomas J (2009) Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med Res Methodol 9(1):59

Corbin JM, Strauss A. Unending work and care: managing chronic illness at home: Jossey-Bass; 1988

Boberg EW, Gustafson DH, Hawkins RP, Offord KP, Koch C, Wen K-Y, Kreutz K, Salner A (2003) Assessing the unmet information, support and care delivery needs of men with prostate cancer. Patient Educ Couns 49(3):233–242

Derdiarian AK (1986) Informational needs of recently diagnosed cancer patients. Nurs Res 35(5):276–281

Beaver K, Latif S, Williamson S, Procter D, Sheridan J, Heath J, Susnerwala S, Luker K (2010) An exploratory study of the follow-up care needs of patients treated for colorectal cancer. J Clin Nurs 19(23–24):3291–3300

Dubey C, De Maria J, Hoeppli C, Betticher D, Eicher M (2015) Resilience and unmet supportive care needs in patients with cancer during early treatment: a descriptive study. Eur J Oncol Nurs 19(5):582–588

Goldfarb M, Casillas J (2013) Unmet information and support needs in newly diagnosed thyroid cancer: comparison of adolescent/young adults (AYA) and older patients. J Cancer Surviv 8(3):394–401

Article Google Scholar

Hasegawa T, Goto N, Matsumoto N, Sasaki Y, Ishiguro T, Kuzuya N, Sugiyama Y (2016) Prevalence of unmet needs and correlated factors in advanced-stage cancer patients receiving rehabilitation. Support Care Cancer 24(11):4761–4767

Hawkins NA, Pollack LA, Leadbetter S, Steele WR, Carroll J, Dolan JG, Ryan EP, Ryan JL, Morrow GR (2008) Informational needs of patients and perceived adequacy of information available before and after treatment of cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol 26(2):1–16

Korner A, Garland R, Czajkowska Z, Coroiu A, Khanna M (2016) Supportive care needs and distress in patients with non-melanoma skin cancer: nothing to worry about? Eur J Oncol Nurs 20:150–155

Li WW, Lam WW, Au AH, Ye M, Law WL, Poon J et al (2013) Interpreting differences in patterns of supportive care needs between patients with breast cancer and patients with colorectal cancer. Psycho-Oncol 22(4):792–798

Article CAS Google Scholar

Moadel AB, Morgan C, Dutcher J (2007) Psychosocial needs assessment among an underserved, ethnically diverse cancer patient population. Cancer. 109(Suppl2):446–454

Moody K, Mannix MM, Furnari N, Fischer J, Kim M, Moadel A (2011) Psychosocial needs of ethnic minority, inner-city, pediatric cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 19(9):1403–1410

Ng CHR, Verkooijen HM, Ooi LL, Koh WP (2011) Unmet psychosocial needs among breast, colorectal and gynaecological cancer patients at the National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS). Support Care Cancer 20(5):1049–1056

O'Connor G, Coates V, O'Neill S (2010) Exploring the information needs of patients with cancer of the rectum. Eur J Oncol Nurs 14(4):271–277

Rainbird K, Perkins J, Sanson-Fisher R, Rolfe I, Anseline P (2009) The needs of patients with advanced, incurable cancer. Br J Cancer 101(5):759–764

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Sanders SL, Bantum EO, Owen JE, Thornton AA, Stanton AL (2010) Supportive care needs in patients with lung cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 19(5):480–489

Whelan TJ, Mohide EA, Willan AR, Arnold A, Tew M, Sellick S, Gafni A, Levine MN (1997) The supportive care needs of newly diagnosed cancer patients attending a regional cancer center. Cancer. 80(8):1518–1524

White K, D'Abrew N, Katris P, O'Connor M, Emery L (2012) Mapping the psychosocial and practical support needs of cancer patients in Western Australia. Eur J Cancer Care. 21(1):107–116

Giacalone A, Blandino M, Talamini R, Bortolus R, Spazzapan S, Valentini M, Tirelli U (2007) What elderly cancer patients want to know? Differences among elderly and young patients. Psycho-Oncology. 16(4):365–370

Masika GM, Wettergren L, Kohi TW, von Essen L (2012) Health-related quality of life and needs of care and support of adult Tanzanians with cancer: a mixed-methods study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 10 (no pagination):(133)

Neumann M, Wirtz M, Ernstmann N, Ommen O, Langler A, Edelhauser F et al (2011) Identifying and predicting subgroups of information needs among cancer patients: an initial study using latent class analysis. Support Care Cancer 19(8):1197–1209

Tamburini M, Gangeri L, Brunelli C, Boeri P, Borreani C, Bosisio M et al (2003) Cancer patients’ needs during hospitalisation: a quantitative and qualitative study. BMC Cancer 3 (no pagination):(12)

van Weert JC, Bolle S, van Dulmen S, Jansen J (2013) Older cancer patients’ information and communication needs: what they want is what they get? Patient Educ Couns 92(3):388–397

Wong RK, Franssen E, Szumacher E, Connolly R, Evans M, Page B, Chow E, Hayter C, Harth T, Andersson L, Pope J, Danjoux C (2002) What do patients living with advanced cancer and their carers want to know? - a needs assessment. Support Care Cancer 10(5):408–415

Beaver K, Williamson S, Briggs J (2016) Exploring patient experiences of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Eur J Oncology Nurs 20:77–86

Grimsbo GH, Finset A, Ruland CM (2011) Left hanging in the air: experiences of living with cancer as expressed through e-mail communications with oncology nurses. Cancer Nurs 34(2):107–116

Heidari H, Mardani-Hamooleh M (2016) Cancer patients’ informational needs: qualitative content analysis. J Cancer Educ 31(4):715–720

Doorenbos AZ, Eaton LH, Haozous E, Towle C, Revels L, Buchwald D (2010) Satisfaction with telehealth for cancer support groups in rural American Indian and Alaska native communities. Clin J Oncol Nurs 14(6):765–770

James-Martin G, Koczwara B, Smith E, Miller M (2014) Information needs of cancer patients and survivors regarding diet, exercise and weight management: a qualitative study. Eur J Cancer Care 23(3):340–348

Decker C, Phillips CR, Haase JE (2004) Information needs of adolescents with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 21(6):327–334

Beesley VL, Janda M, Goldstein D, Gooden H, Merrett ND, O'Connell DL, Rowlands IJ, Wyld D, Neale RE (2016) A tsunami of unmet needs: pancreatic and ampullary cancer patients’ supportive care needs and use of community and allied health services. Psycho-Oncology. 25(2):150–157

Choi KH, Park JH, Park SM (2011) Cancer patients’ informational needs on health promotion and related factors: a multi-institutional, cross-sectional study in Korea. Support Care Cancer 19(10):1495–1504

Buzgova R, Hajnova E, Sikorova L, Jarosova D (2014) Association between unmet needs and quality of life in hospitalised cancer patients no longer receiving anti-cancer treatment. Eur J Cancer Care. 23(5):685–694

Elsner F, Schmidt J, Rajagopal MR, Radbruch L, Pestinger M (2012) Psychosocial and spiritual problems of terminally ill patients in Kerala, India. Future Oncol 8(9):1183–1191

Hsiao SM, Gau ML, Ingleton C, Ryan T, Shih FJ (2011) An exploration of spiritual needs of Taiwanese patients with advanced cancer during the therapeutic processes. J Clin Nurs 20(7–8):950–959

Sharma RK, Astrow AB, Texeira K, Sulmasy DP (2012) The spiritual needs assessment for patients (SNAP): development and validation of a comprehensive instrument to assess unmet spiritual needs. J Pain Symptom Manag 44(1):44–51

Kent EE, Smith AW, Keegan TH, Lynch CF, Wu X-C, Hamilton AS et al (2013) Talking about cancer and meeting peer survivors: social information needs of adolescents and young adults diagnosed with cancer. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2(2):44–52

O'Connor G, Coates V, O'Neill S (2010) Exploring the information needs of patients with cancer of the rectum. Eur J Oncol Nurs 14(4):271–277

Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, Worth A, Benton T (2004) Exploring the spiritual needs of people dying of lung cancer or heart failure: a prospective qualitative interview study of patients and their carers. Palliat Med 18(1):39–45

Astrow AB, Wexler A, Texeira K, He MK, Sulmasy DP (2007) Is failure to meet spiritual needs associated with cancer patients’ perceptions of quality of care and their satisfaction with care? J Clin Oncol 25(36):5753–5757

Shih FJ, Lin HR, Gau ML, Chen CH, Hsiao SM, Shih SN, Sheu SJ (2009) Spiritual needs of Taiwan’s older patients with terminal cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 36(1):E31–EE8

Hampton DM, Hollis DE, Lloyd DA, Taylor J, McMillan SC (2007) Spiritual needs of persons with advanced cancer. Am J Hospice Palliat Med 24(1):42–48

Dedeli O, Yildiz E, Yuksel S (2015) Assessing the spiritual needs and practices of oncology patients in Turkey. Holist Nurs Pract 29(2):103–113

Ghahramanian A, Markani AK, Davoodi A, Bahrami A (2016) Spiritual needs of patients with cancer referred to Alinasab and Shahid Ghazi Tabatabaie Hospitals of Tabriz, Iran. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP 17(7):3105–3109

PubMed Google Scholar

Taylor EJ (2006) Prevalence and associated factors of spiritual needs among patients with cancer and family caregivers. Oncol Nurs Forum 33(4):729–735

Vilalta A, Valls J, Porta J, Vinas J (2014) Evaluation of spiritual needs of patients with advanced cancer in a palliative care unit. J Palliat Med 17(5):592–600

Taylor EJ (2003) Spiritual needs of patients with cancer and family caregivers. Cancer Nurs 26(4):260–266

Hocker A, Krull A, Koch U, Mehnert A (2014) Exploring spiritual needs and their associated factors in an urban sample of early and advanced cancer patients. European Journal of Cancer Care. 23(6):786–794

Rutten LJF, Arora NK, Bakos AD, Aziz N, Rowland J (2005) Information needs and sources of information among cancer patients: a systematic review of research (1980–2003). Patient Educ Couns 57(3):250–261

Fletcher C, Flight I, Chapman J, Fennell K, Wilson C (2017) The information needs of adult cancer survivors across the cancer continuum: a scoping review. Patient Educ Couns 100(3):383–410

Lin HR, Bauer-Wu SM (2003) Psycho-spiritual well-being in patients with advanced cancer: an integrative review of the literature. J Adv Nurs 44(1):69–80

Harrison JD, Young JM, Price MA, Butow PN, Solomon MJ (2009) What are the unmet supportive care needs of people with cancer? A systematic review. Support Care Cancer 17(8):1117–1128

Sanson-Fisher R, Girgis A, Boyes A, Bonevski B, Burton L, Cook P, Supportive Care Review Group (2000) The unmet supportive care needs of patients with cancer. Cancer. 88(1):226–237

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

UCL Research Department of Epidemiology & Public Health, 1-19 Torrington Place, London, WC1E 6BT, UK

Madeleine Evans Webb

Department of Primary Care and Population Health, Upper 3rd Floor, Royal Free Hospital, Rowland Hill Street, London, NW3 2PF, UK

Elizabeth Murray, Zane William Younger, Henry Goodfellow & Jamie Ross

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Elizabeth Murray .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

This work was part-funded by the MacMillan Cancer Support Research Grant number 6488115. Elizabeth Murray receives funding from the NIHR School for Primary Care Research and the NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care North Thames. Henry Goodfellow is funded through an NIHR Academic Clinical Fellowship. Jamie Ross is funded by an NIHR School for Primary Care Research fellowship.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 58 kb)

(DOCX 118 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Evans Webb, M., Murray, E., Younger, Z.W. et al. The Supportive Care Needs of Cancer Patients: a Systematic Review. J Canc Educ 36 , 899–908 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01941-9

Download citation

Accepted : 06 December 2020

Published : 25 January 2021

Issue Date : October 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01941-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Supportive care

- Patient needs

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Depression and Anxiety in Patients With Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abdallah y. naser.

1 Faculty of Pharmacy, Isra University, Amman, Jordan

Anas Nawfal Hameed

Nour mustafa.

2 Department of Pharmacy, King Hussein Cancer Center, Amman, Jordan

Hassan Alwafi

3 Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, College of Medicine, Umm Al-Qura University, Mecca, Saudi Arabia

Eman Zmaily Dahmash

Hamad s. alyami.

4 Department of Pharmaceutics, College of Pharmacy, Najran University, Najran, Saudi Arabia

Haya Khalil

Associated data.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/ Supplementary Material , further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Depression and anxiety persist in cancer patients, creating an additional burden during treatment and making it more challenging in terms of management and control. Studies on the prevalence of depression and anxiety among cancer patients in the Middle East are limited and include many limitations such as their small sample sizes and restriction to a specific type of cancer in specific clinical settings. This study aimed to describe the prevalence and risk factors of depression and anxiety among cancer patients in the inpatient and outpatient settings.

Materials and Methods

A total of 1,011 patients (399 inpatients and 612 outpatients) formed the study sample. Patients’ psychological status was assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale. The prevalence rate of depressive and anxious symptomatology was estimated by dividing the number of patients who exceeded the borderline score: 10 or more for each subscale of the HADS scale, 15 or more for the GAD-7 scale, and 15 or more in the PHQ-9 by the total number of the patients. Risk factors were identified using logistic regression.