Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

| Research question | Case study |

|---|---|

| What are the ecological effects of wolf reintroduction? | Case study of wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone National Park |

| How do populist politicians use narratives about history to gain support? | Case studies of Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and US president Donald Trump |

| How can teachers implement active learning strategies in mixed-level classrooms? | Case study of a local school that promotes active learning |

| What are the main advantages and disadvantages of wind farms for rural communities? | Case studies of three rural wind farm development projects in different parts of the country |

| How are viral marketing strategies changing the relationship between companies and consumers? | Case study of the iPhone X marketing campaign |

| How do experiences of work in the gig economy differ by gender, race and age? | Case studies of Deliveroo and Uber drivers in London |

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved July 23, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 1: The Basics

- Introduction and overview

- What is qualitative research?

- What is qualitative data?

- Examples of qualitative data

- Qualitative vs. quantitative research

- Mixed methods

- Qualitative research preparation

- Theoretical perspective

- Theoretical framework

- Literature reviews

Research question

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual vs. theoretical framework

Data collection

- Qualitative research methods

- Focus groups

- Observational research

What is a case study?

Applications for case study research, what is a good case study, process of case study design, benefits and limitations of case studies.

- Ethnographical research

- Ethical considerations

- Confidentiality and privacy

- Power dynamics

- Reflexivity

Case studies

Case studies are essential to qualitative research , offering a lens through which researchers can investigate complex phenomena within their real-life contexts. This chapter explores the concept, purpose, applications, examples, and types of case studies and provides guidance on how to conduct case study research effectively.

Whereas quantitative methods look at phenomena at scale, case study research looks at a concept or phenomenon in considerable detail. While analyzing a single case can help understand one perspective regarding the object of research inquiry, analyzing multiple cases can help obtain a more holistic sense of the topic or issue. Let's provide a basic definition of a case study, then explore its characteristics and role in the qualitative research process.

Definition of a case study

A case study in qualitative research is a strategy of inquiry that involves an in-depth investigation of a phenomenon within its real-world context. It provides researchers with the opportunity to acquire an in-depth understanding of intricate details that might not be as apparent or accessible through other methods of research. The specific case or cases being studied can be a single person, group, or organization – demarcating what constitutes a relevant case worth studying depends on the researcher and their research question .

Among qualitative research methods , a case study relies on multiple sources of evidence, such as documents, artifacts, interviews , or observations , to present a complete and nuanced understanding of the phenomenon under investigation. The objective is to illuminate the readers' understanding of the phenomenon beyond its abstract statistical or theoretical explanations.

Characteristics of case studies

Case studies typically possess a number of distinct characteristics that set them apart from other research methods. These characteristics include a focus on holistic description and explanation, flexibility in the design and data collection methods, reliance on multiple sources of evidence, and emphasis on the context in which the phenomenon occurs.

Furthermore, case studies can often involve a longitudinal examination of the case, meaning they study the case over a period of time. These characteristics allow case studies to yield comprehensive, in-depth, and richly contextualized insights about the phenomenon of interest.

The role of case studies in research

Case studies hold a unique position in the broader landscape of research methods aimed at theory development. They are instrumental when the primary research interest is to gain an intensive, detailed understanding of a phenomenon in its real-life context.

In addition, case studies can serve different purposes within research - they can be used for exploratory, descriptive, or explanatory purposes, depending on the research question and objectives. This flexibility and depth make case studies a valuable tool in the toolkit of qualitative researchers.

Remember, a well-conducted case study can offer a rich, insightful contribution to both academic and practical knowledge through theory development or theory verification, thus enhancing our understanding of complex phenomena in their real-world contexts.

What is the purpose of a case study?

Case study research aims for a more comprehensive understanding of phenomena, requiring various research methods to gather information for qualitative analysis . Ultimately, a case study can allow the researcher to gain insight into a particular object of inquiry and develop a theoretical framework relevant to the research inquiry.

Why use case studies in qualitative research?

Using case studies as a research strategy depends mainly on the nature of the research question and the researcher's access to the data.

Conducting case study research provides a level of detail and contextual richness that other research methods might not offer. They are beneficial when there's a need to understand complex social phenomena within their natural contexts.

The explanatory, exploratory, and descriptive roles of case studies

Case studies can take on various roles depending on the research objectives. They can be exploratory when the research aims to discover new phenomena or define new research questions; they are descriptive when the objective is to depict a phenomenon within its context in a detailed manner; and they can be explanatory if the goal is to understand specific relationships within the studied context. Thus, the versatility of case studies allows researchers to approach their topic from different angles, offering multiple ways to uncover and interpret the data .

The impact of case studies on knowledge development

Case studies play a significant role in knowledge development across various disciplines. Analysis of cases provides an avenue for researchers to explore phenomena within their context based on the collected data.

This can result in the production of rich, practical insights that can be instrumental in both theory-building and practice. Case studies allow researchers to delve into the intricacies and complexities of real-life situations, uncovering insights that might otherwise remain hidden.

Types of case studies

In qualitative research , a case study is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Depending on the nature of the research question and the specific objectives of the study, researchers might choose to use different types of case studies. These types differ in their focus, methodology, and the level of detail they provide about the phenomenon under investigation.

Understanding these types is crucial for selecting the most appropriate approach for your research project and effectively achieving your research goals. Let's briefly look at the main types of case studies.

Exploratory case studies

Exploratory case studies are typically conducted to develop a theory or framework around an understudied phenomenon. They can also serve as a precursor to a larger-scale research project. Exploratory case studies are useful when a researcher wants to identify the key issues or questions which can spur more extensive study or be used to develop propositions for further research. These case studies are characterized by flexibility, allowing researchers to explore various aspects of a phenomenon as they emerge, which can also form the foundation for subsequent studies.

Descriptive case studies

Descriptive case studies aim to provide a complete and accurate representation of a phenomenon or event within its context. These case studies are often based on an established theoretical framework, which guides how data is collected and analyzed. The researcher is concerned with describing the phenomenon in detail, as it occurs naturally, without trying to influence or manipulate it.

Explanatory case studies

Explanatory case studies are focused on explanation - they seek to clarify how or why certain phenomena occur. Often used in complex, real-life situations, they can be particularly valuable in clarifying causal relationships among concepts and understanding the interplay between different factors within a specific context.

Intrinsic, instrumental, and collective case studies

These three categories of case studies focus on the nature and purpose of the study. An intrinsic case study is conducted when a researcher has an inherent interest in the case itself. Instrumental case studies are employed when the case is used to provide insight into a particular issue or phenomenon. A collective case study, on the other hand, involves studying multiple cases simultaneously to investigate some general phenomena.

Each type of case study serves a different purpose and has its own strengths and challenges. The selection of the type should be guided by the research question and objectives, as well as the context and constraints of the research.

The flexibility, depth, and contextual richness offered by case studies make this approach an excellent research method for various fields of study. They enable researchers to investigate real-world phenomena within their specific contexts, capturing nuances that other research methods might miss. Across numerous fields, case studies provide valuable insights into complex issues.

Critical information systems research

Case studies provide a detailed understanding of the role and impact of information systems in different contexts. They offer a platform to explore how information systems are designed, implemented, and used and how they interact with various social, economic, and political factors. Case studies in this field often focus on examining the intricate relationship between technology, organizational processes, and user behavior, helping to uncover insights that can inform better system design and implementation.

Health research

Health research is another field where case studies are highly valuable. They offer a way to explore patient experiences, healthcare delivery processes, and the impact of various interventions in a real-world context.

Case studies can provide a deep understanding of a patient's journey, giving insights into the intricacies of disease progression, treatment effects, and the psychosocial aspects of health and illness.

Asthma research studies

Specifically within medical research, studies on asthma often employ case studies to explore the individual and environmental factors that influence asthma development, management, and outcomes. A case study can provide rich, detailed data about individual patients' experiences, from the triggers and symptoms they experience to the effectiveness of various management strategies. This can be crucial for developing patient-centered asthma care approaches.

Other fields

Apart from the fields mentioned, case studies are also extensively used in business and management research, education research, and political sciences, among many others. They provide an opportunity to delve into the intricacies of real-world situations, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of various phenomena.

Case studies, with their depth and contextual focus, offer unique insights across these varied fields. They allow researchers to illuminate the complexities of real-life situations, contributing to both theory and practice.

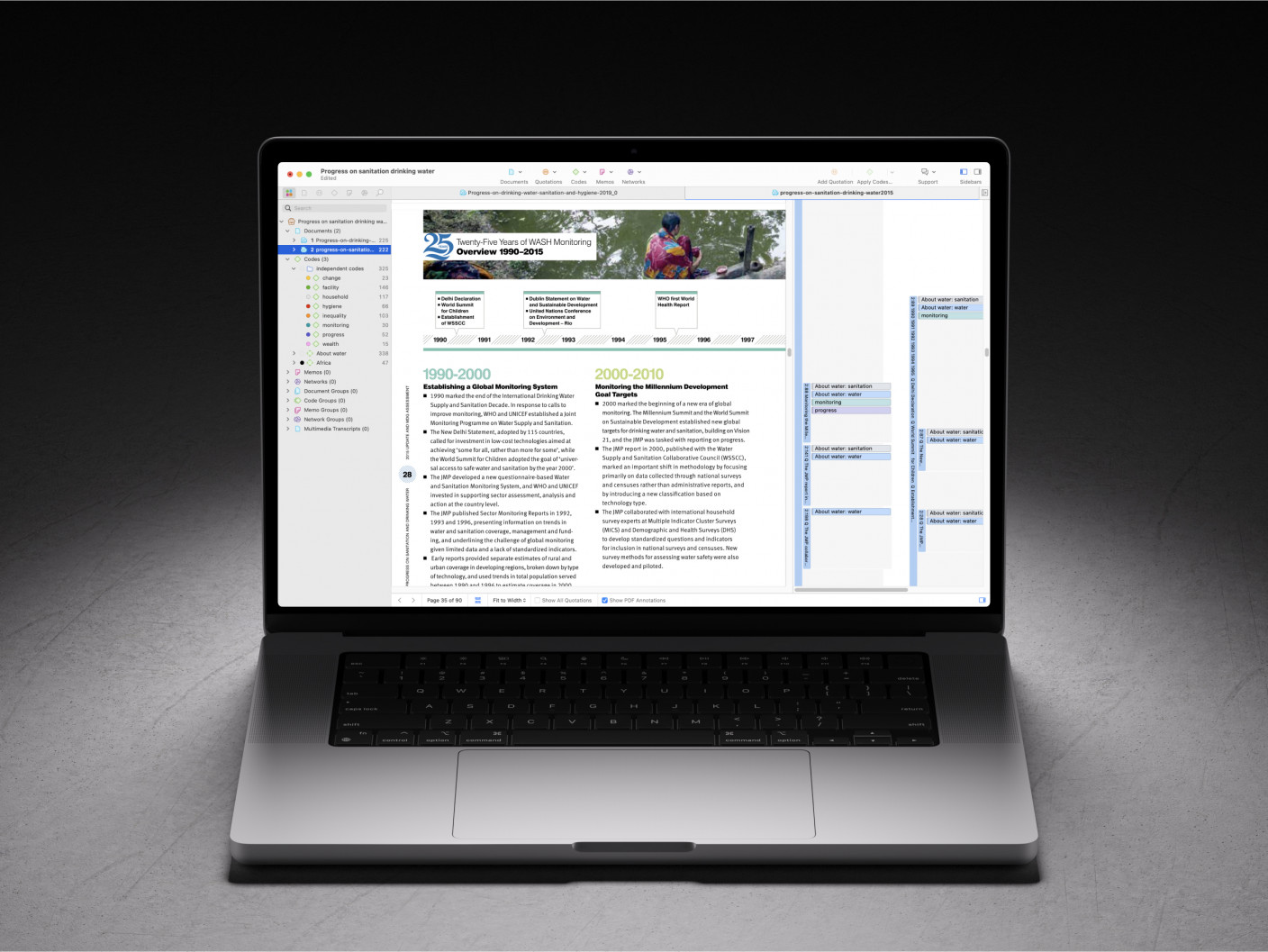

Whatever field you're in, ATLAS.ti puts your data to work for you

Download a free trial of ATLAS.ti to turn your data into insights.

Understanding the key elements of case study design is crucial for conducting rigorous and impactful case study research. A well-structured design guides the researcher through the process, ensuring that the study is methodologically sound and its findings are reliable and valid. The main elements of case study design include the research question , propositions, units of analysis, and the logic linking the data to the propositions.

The research question is the foundation of any research study. A good research question guides the direction of the study and informs the selection of the case, the methods of collecting data, and the analysis techniques. A well-formulated research question in case study research is typically clear, focused, and complex enough to merit further detailed examination of the relevant case(s).

Propositions

Propositions, though not necessary in every case study, provide a direction by stating what we might expect to find in the data collected. They guide how data is collected and analyzed by helping researchers focus on specific aspects of the case. They are particularly important in explanatory case studies, which seek to understand the relationships among concepts within the studied phenomenon.

Units of analysis

The unit of analysis refers to the case, or the main entity or entities that are being analyzed in the study. In case study research, the unit of analysis can be an individual, a group, an organization, a decision, an event, or even a time period. It's crucial to clearly define the unit of analysis, as it shapes the qualitative data analysis process by allowing the researcher to analyze a particular case and synthesize analysis across multiple case studies to draw conclusions.

Argumentation

This refers to the inferential model that allows researchers to draw conclusions from the data. The researcher needs to ensure that there is a clear link between the data, the propositions (if any), and the conclusions drawn. This argumentation is what enables the researcher to make valid and credible inferences about the phenomenon under study.

Understanding and carefully considering these elements in the design phase of a case study can significantly enhance the quality of the research. It can help ensure that the study is methodologically sound and its findings contribute meaningful insights about the case.

Ready to jumpstart your research with ATLAS.ti?

Conceptualize your research project with our intuitive data analysis interface. Download a free trial today.

Conducting a case study involves several steps, from defining the research question and selecting the case to collecting and analyzing data . This section outlines these key stages, providing a practical guide on how to conduct case study research.

Defining the research question

The first step in case study research is defining a clear, focused research question. This question should guide the entire research process, from case selection to analysis. It's crucial to ensure that the research question is suitable for a case study approach. Typically, such questions are exploratory or descriptive in nature and focus on understanding a phenomenon within its real-life context.

Selecting and defining the case

The selection of the case should be based on the research question and the objectives of the study. It involves choosing a unique example or a set of examples that provide rich, in-depth data about the phenomenon under investigation. After selecting the case, it's crucial to define it clearly, setting the boundaries of the case, including the time period and the specific context.

Previous research can help guide the case study design. When considering a case study, an example of a case could be taken from previous case study research and used to define cases in a new research inquiry. Considering recently published examples can help understand how to select and define cases effectively.

Developing a detailed case study protocol

A case study protocol outlines the procedures and general rules to be followed during the case study. This includes the data collection methods to be used, the sources of data, and the procedures for analysis. Having a detailed case study protocol ensures consistency and reliability in the study.

The protocol should also consider how to work with the people involved in the research context to grant the research team access to collecting data. As mentioned in previous sections of this guide, establishing rapport is an essential component of qualitative research as it shapes the overall potential for collecting and analyzing data.

Collecting data

Gathering data in case study research often involves multiple sources of evidence, including documents, archival records, interviews, observations, and physical artifacts. This allows for a comprehensive understanding of the case. The process for gathering data should be systematic and carefully documented to ensure the reliability and validity of the study.

Analyzing and interpreting data

The next step is analyzing the data. This involves organizing the data , categorizing it into themes or patterns , and interpreting these patterns to answer the research question. The analysis might also involve comparing the findings with prior research or theoretical propositions.

Writing the case study report

The final step is writing the case study report . This should provide a detailed description of the case, the data, the analysis process, and the findings. The report should be clear, organized, and carefully written to ensure that the reader can understand the case and the conclusions drawn from it.

Each of these steps is crucial in ensuring that the case study research is rigorous, reliable, and provides valuable insights about the case.

The type, depth, and quality of data in your study can significantly influence the validity and utility of the study. In case study research, data is usually collected from multiple sources to provide a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case. This section will outline the various methods of collecting data used in case study research and discuss considerations for ensuring the quality of the data.

Interviews are a common method of gathering data in case study research. They can provide rich, in-depth data about the perspectives, experiences, and interpretations of the individuals involved in the case. Interviews can be structured , semi-structured , or unstructured , depending on the research question and the degree of flexibility needed.

Observations

Observations involve the researcher observing the case in its natural setting, providing first-hand information about the case and its context. Observations can provide data that might not be revealed in interviews or documents, such as non-verbal cues or contextual information.

Documents and artifacts

Documents and archival records provide a valuable source of data in case study research. They can include reports, letters, memos, meeting minutes, email correspondence, and various public and private documents related to the case.

These records can provide historical context, corroborate evidence from other sources, and offer insights into the case that might not be apparent from interviews or observations.

Physical artifacts refer to any physical evidence related to the case, such as tools, products, or physical environments. These artifacts can provide tangible insights into the case, complementing the data gathered from other sources.

Ensuring the quality of data collection

Determining the quality of data in case study research requires careful planning and execution. It's crucial to ensure that the data is reliable, accurate, and relevant to the research question. This involves selecting appropriate methods of collecting data, properly training interviewers or observers, and systematically recording and storing the data. It also includes considering ethical issues related to collecting and handling data, such as obtaining informed consent and ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of the participants.

Data analysis

Analyzing case study research involves making sense of the rich, detailed data to answer the research question. This process can be challenging due to the volume and complexity of case study data. However, a systematic and rigorous approach to analysis can ensure that the findings are credible and meaningful. This section outlines the main steps and considerations in analyzing data in case study research.

Organizing the data

The first step in the analysis is organizing the data. This involves sorting the data into manageable sections, often according to the data source or the theme. This step can also involve transcribing interviews, digitizing physical artifacts, or organizing observational data.

Categorizing and coding the data

Once the data is organized, the next step is to categorize or code the data. This involves identifying common themes, patterns, or concepts in the data and assigning codes to relevant data segments. Coding can be done manually or with the help of software tools, and in either case, qualitative analysis software can greatly facilitate the entire coding process. Coding helps to reduce the data to a set of themes or categories that can be more easily analyzed.

Identifying patterns and themes

After coding the data, the researcher looks for patterns or themes in the coded data. This involves comparing and contrasting the codes and looking for relationships or patterns among them. The identified patterns and themes should help answer the research question.

Interpreting the data

Once patterns and themes have been identified, the next step is to interpret these findings. This involves explaining what the patterns or themes mean in the context of the research question and the case. This interpretation should be grounded in the data, but it can also involve drawing on theoretical concepts or prior research.

Verification of the data

The last step in the analysis is verification. This involves checking the accuracy and consistency of the analysis process and confirming that the findings are supported by the data. This can involve re-checking the original data, checking the consistency of codes, or seeking feedback from research participants or peers.

Like any research method , case study research has its strengths and limitations. Researchers must be aware of these, as they can influence the design, conduct, and interpretation of the study.

Understanding the strengths and limitations of case study research can also guide researchers in deciding whether this approach is suitable for their research question . This section outlines some of the key strengths and limitations of case study research.

Benefits include the following:

- Rich, detailed data: One of the main strengths of case study research is that it can generate rich, detailed data about the case. This can provide a deep understanding of the case and its context, which can be valuable in exploring complex phenomena.

- Flexibility: Case study research is flexible in terms of design , data collection , and analysis . A sufficient degree of flexibility allows the researcher to adapt the study according to the case and the emerging findings.

- Real-world context: Case study research involves studying the case in its real-world context, which can provide valuable insights into the interplay between the case and its context.

- Multiple sources of evidence: Case study research often involves collecting data from multiple sources , which can enhance the robustness and validity of the findings.

On the other hand, researchers should consider the following limitations:

- Generalizability: A common criticism of case study research is that its findings might not be generalizable to other cases due to the specificity and uniqueness of each case.

- Time and resource intensive: Case study research can be time and resource intensive due to the depth of the investigation and the amount of collected data.

- Complexity of analysis: The rich, detailed data generated in case study research can make analyzing the data challenging.

- Subjectivity: Given the nature of case study research, there may be a higher degree of subjectivity in interpreting the data , so researchers need to reflect on this and transparently convey to audiences how the research was conducted.

Being aware of these strengths and limitations can help researchers design and conduct case study research effectively and interpret and report the findings appropriately.

Ready to analyze your data with ATLAS.ti?

See how our intuitive software can draw key insights from your data with a free trial today.

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Statistics By Jim

Making statistics intuitive

What is a Case Study? Definition & Examples

By Jim Frost Leave a Comment

Case Study Definition

A case study is an in-depth investigation of a single person, group, event, or community. This research method involves intensively analyzing a subject to understand its complexity and context. The richness of a case study comes from its ability to capture detailed, qualitative data that can offer insights into a process or subject matter that other research methods might miss.

A case study strives for a holistic understanding of events or situations by examining all relevant variables. They are ideal for exploring ‘how’ or ‘why’ questions in contexts where the researcher has limited control over events in real-life settings. Unlike narrowly focused experiments, these projects seek a comprehensive understanding of events or situations.

In a case study, researchers gather data through various methods such as participant observation, interviews, tests, record examinations, and writing samples. Unlike statistically-based studies that seek only quantifiable data, a case study attempts to uncover new variables and pose questions for subsequent research.

A case study is particularly beneficial when your research:

- Requires a deep, contextual understanding of a specific case.

- Needs to explore or generate hypotheses rather than test them.

- Focuses on a contemporary phenomenon within a real-life context.

Learn more about Other Types of Experimental Design .

Case Study Examples

Various fields utilize case studies, including the following:

- Social sciences : For understanding complex social phenomena.

- Business : For analyzing corporate strategies and business decisions.

- Healthcare : For detailed patient studies and medical research.

- Education : For understanding educational methods and policies.

- Law : For in-depth analysis of legal cases.

For example, consider a case study in a business setting where a startup struggles to scale. Researchers might examine the startup’s strategies, market conditions, management decisions, and competition. Interviews with the CEO, employees, and customers, alongside an analysis of financial data, could offer insights into the challenges and potential solutions for the startup. This research could serve as a valuable lesson for other emerging businesses.

See below for other examples.

| What impact does urban green space have on mental health in high-density cities? | Assess a green space development in Tokyo and its effects on resident mental health. |

| How do small businesses adapt to rapid technological changes? | Examine a small business in Silicon Valley adapting to new tech trends. |

| What strategies are effective in reducing plastic waste in coastal cities? | Study plastic waste management initiatives in Barcelona. |

| How do educational approaches differ in addressing diverse learning needs? | Investigate a specialized school’s approach to inclusive education in Sweden. |

| How does community involvement influence the success of public health initiatives? | Evaluate a community-led health program in rural India. |

| What are the challenges and successes of renewable energy adoption in developing countries? | Assess solar power implementation in a Kenyan village. |

Types of Case Studies

Several standard types of case studies exist that vary based on the objectives and specific research needs.

Illustrative Case Study : Descriptive in nature, these studies use one or two instances to depict a situation, helping to familiarize the unfamiliar and establish a common understanding of the topic.

Exploratory Case Study : Conducted as precursors to large-scale investigations, they assist in raising relevant questions, choosing measurement types, and identifying hypotheses to test.

Cumulative Case Study : These studies compile information from various sources over time to enhance generalization without the need for costly, repetitive new studies.

Critical Instance Case Study : Focused on specific sites, they either explore unique situations with limited generalizability or challenge broad assertions, to identify potential cause-and-effect issues.

Pros and Cons

As with any research study, case studies have a set of benefits and drawbacks.

- Provides comprehensive and detailed data.

- Offers a real-life perspective.

- Flexible and can adapt to discoveries during the study.

- Enables investigation of scenarios that are hard to assess in laboratory settings.

- Facilitates studying rare or unique cases.

- Generates hypotheses for future experimental research.

- Time-consuming and may require a lot of resources.

- Hard to generalize findings to a broader context.

- Potential for researcher bias.

- Cannot establish causality .

- Lacks scientific rigor compared to more controlled research methods .

Crafting a Good Case Study: Methodology

While case studies emphasize specific details over broad theories, they should connect to theoretical frameworks in the field. This approach ensures that these projects contribute to the existing body of knowledge on the subject, rather than standing as an isolated entity.

The following are critical steps in developing a case study:

- Define the Research Questions : Clearly outline what you want to explore. Define specific, achievable objectives.

- Select the Case : Choose a case that best suits the research questions. Consider using a typical case for general understanding or an atypical subject for unique insights.

- Data Collection : Use a variety of data sources, such as interviews, observations, documents, and archival records, to provide multiple perspectives on the issue.

- Data Analysis : Identify patterns and themes in the data.

- Report Findings : Present the findings in a structured and clear manner.

Analysts typically use thematic analysis to identify patterns and themes within the data and compare different cases.

- Qualitative Analysis : Such as coding and thematic analysis for narrative data.

- Quantitative Analysis : In cases where numerical data is involved.

- Triangulation : Combining multiple methods or data sources to enhance accuracy.

A good case study requires a balanced approach, often using both qualitative and quantitative methods.

The researcher should constantly reflect on their biases and how they might influence the research. Documenting personal reflections can provide transparency.

Avoid over-generalization. One common mistake is to overstate the implications of a case study. Remember that these studies provide an in-depth insights into a specific case and might not be widely applicable.

Don’t ignore contradictory data. All data, even that which contradicts your hypothesis, is valuable. Ignoring it can lead to skewed results.

Finally, in the report, researchers provide comprehensive insight for a case study through “thick description,” which entails a detailed portrayal of the subject, its usage context, the attributes of involved individuals, and the community environment. Thick description extends to interpreting various data, including demographic details, cultural norms, societal values, prevailing attitudes, and underlying motivations. This approach ensures a nuanced and in-depth comprehension of the case in question.

Learn more about Qualitative Research and Qualitative vs. Quantitative Data .

Morland, J. & Feagin, Joe & Orum, Anthony & Sjoberg, Gideon. (1992). A Case for the Case Study . Social Forces. 71(1):240.

Share this:

Reader Interactions

Comments and questions cancel reply.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

A case study is a research method that involves an in-depth examination and analysis of a particular phenomenon or case, such as an individual, organization, community, event, or situation.

It is a qualitative research approach that aims to provide a detailed and comprehensive understanding of the case being studied. Case studies typically involve multiple sources of data, including interviews, observations, documents, and artifacts, which are analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, and grounded theory. The findings of a case study are often used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Types of Case Study

Types and Methods of Case Study are as follows:

Single-Case Study

A single-case study is an in-depth analysis of a single case. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand a specific phenomenon in detail.

For Example , A researcher might conduct a single-case study on a particular individual to understand their experiences with a particular health condition or a specific organization to explore their management practices. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a single-case study are often used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Multiple-Case Study

A multiple-case study involves the analysis of several cases that are similar in nature. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to identify similarities and differences between the cases.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a multiple-case study on several companies to explore the factors that contribute to their success or failure. The researcher collects data from each case, compares and contrasts the findings, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as comparative analysis or pattern-matching. The findings of a multiple-case study can be used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Exploratory Case Study

An exploratory case study is used to explore a new or understudied phenomenon. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to generate hypotheses or theories about the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an exploratory case study on a new technology to understand its potential impact on society. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as grounded theory or content analysis. The findings of an exploratory case study can be used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Descriptive Case Study

A descriptive case study is used to describe a particular phenomenon in detail. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to provide a comprehensive account of the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a descriptive case study on a particular community to understand its social and economic characteristics. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a descriptive case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Instrumental Case Study

An instrumental case study is used to understand a particular phenomenon that is instrumental in achieving a particular goal. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand the role of the phenomenon in achieving the goal.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an instrumental case study on a particular policy to understand its impact on achieving a particular goal, such as reducing poverty. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of an instrumental case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Case Study Data Collection Methods

Here are some common data collection methods for case studies:

Interviews involve asking questions to individuals who have knowledge or experience relevant to the case study. Interviews can be structured (where the same questions are asked to all participants) or unstructured (where the interviewer follows up on the responses with further questions). Interviews can be conducted in person, over the phone, or through video conferencing.

Observations

Observations involve watching and recording the behavior and activities of individuals or groups relevant to the case study. Observations can be participant (where the researcher actively participates in the activities) or non-participant (where the researcher observes from a distance). Observations can be recorded using notes, audio or video recordings, or photographs.

Documents can be used as a source of information for case studies. Documents can include reports, memos, emails, letters, and other written materials related to the case study. Documents can be collected from the case study participants or from public sources.

Surveys involve asking a set of questions to a sample of individuals relevant to the case study. Surveys can be administered in person, over the phone, through mail or email, or online. Surveys can be used to gather information on attitudes, opinions, or behaviors related to the case study.

Artifacts are physical objects relevant to the case study. Artifacts can include tools, equipment, products, or other objects that provide insights into the case study phenomenon.

How to conduct Case Study Research

Conducting a case study research involves several steps that need to be followed to ensure the quality and rigor of the study. Here are the steps to conduct case study research:

- Define the research questions: The first step in conducting a case study research is to define the research questions. The research questions should be specific, measurable, and relevant to the case study phenomenon under investigation.

- Select the case: The next step is to select the case or cases to be studied. The case should be relevant to the research questions and should provide rich and diverse data that can be used to answer the research questions.

- Collect data: Data can be collected using various methods, such as interviews, observations, documents, surveys, and artifacts. The data collection method should be selected based on the research questions and the nature of the case study phenomenon.

- Analyze the data: The data collected from the case study should be analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, or grounded theory. The analysis should be guided by the research questions and should aim to provide insights and conclusions relevant to the research questions.

- Draw conclusions: The conclusions drawn from the case study should be based on the data analysis and should be relevant to the research questions. The conclusions should be supported by evidence and should be clearly stated.

- Validate the findings: The findings of the case study should be validated by reviewing the data and the analysis with participants or other experts in the field. This helps to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Write the report: The final step is to write the report of the case study research. The report should provide a clear description of the case study phenomenon, the research questions, the data collection methods, the data analysis, the findings, and the conclusions. The report should be written in a clear and concise manner and should follow the guidelines for academic writing.

Examples of Case Study

Here are some examples of case study research:

- The Hawthorne Studies : Conducted between 1924 and 1932, the Hawthorne Studies were a series of case studies conducted by Elton Mayo and his colleagues to examine the impact of work environment on employee productivity. The studies were conducted at the Hawthorne Works plant of the Western Electric Company in Chicago and included interviews, observations, and experiments.

- The Stanford Prison Experiment: Conducted in 1971, the Stanford Prison Experiment was a case study conducted by Philip Zimbardo to examine the psychological effects of power and authority. The study involved simulating a prison environment and assigning participants to the role of guards or prisoners. The study was controversial due to the ethical issues it raised.

- The Challenger Disaster: The Challenger Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion in 1986. The study included interviews, observations, and analysis of data to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

- The Enron Scandal: The Enron Scandal was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Enron Corporation’s bankruptcy in 2001. The study included interviews, analysis of financial data, and review of documents to identify the accounting practices, corporate culture, and ethical issues that led to the company’s downfall.

- The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster : The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the nuclear accident that occurred at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan in 2011. The study included interviews, analysis of data, and review of documents to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

Application of Case Study

Case studies have a wide range of applications across various fields and industries. Here are some examples:

Business and Management

Case studies are widely used in business and management to examine real-life situations and develop problem-solving skills. Case studies can help students and professionals to develop a deep understanding of business concepts, theories, and best practices.

Case studies are used in healthcare to examine patient care, treatment options, and outcomes. Case studies can help healthcare professionals to develop critical thinking skills, diagnose complex medical conditions, and develop effective treatment plans.

Case studies are used in education to examine teaching and learning practices. Case studies can help educators to develop effective teaching strategies, evaluate student progress, and identify areas for improvement.

Social Sciences

Case studies are widely used in social sciences to examine human behavior, social phenomena, and cultural practices. Case studies can help researchers to develop theories, test hypotheses, and gain insights into complex social issues.

Law and Ethics

Case studies are used in law and ethics to examine legal and ethical dilemmas. Case studies can help lawyers, policymakers, and ethical professionals to develop critical thinking skills, analyze complex cases, and make informed decisions.

Purpose of Case Study

The purpose of a case study is to provide a detailed analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. A case study is a qualitative research method that involves the in-depth exploration and analysis of a particular case, which can be an individual, group, organization, event, or community.

The primary purpose of a case study is to generate a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case, including its history, context, and dynamics. Case studies can help researchers to identify and examine the underlying factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and detailed understanding of the case, which can inform future research, practice, or policy.

Case studies can also serve other purposes, including:

- Illustrating a theory or concept: Case studies can be used to illustrate and explain theoretical concepts and frameworks, providing concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Developing hypotheses: Case studies can help to generate hypotheses about the causal relationships between different factors and outcomes, which can be tested through further research.

- Providing insight into complex issues: Case studies can provide insights into complex and multifaceted issues, which may be difficult to understand through other research methods.

- Informing practice or policy: Case studies can be used to inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

Advantages of Case Study Research

There are several advantages of case study research, including:

- In-depth exploration: Case study research allows for a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. This can provide a comprehensive understanding of the case and its dynamics, which may not be possible through other research methods.

- Rich data: Case study research can generate rich and detailed data, including qualitative data such as interviews, observations, and documents. This can provide a nuanced understanding of the case and its complexity.

- Holistic perspective: Case study research allows for a holistic perspective of the case, taking into account the various factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the case.

- Theory development: Case study research can help to develop and refine theories and concepts by providing empirical evidence and concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Practical application: Case study research can inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

- Contextualization: Case study research takes into account the specific context in which the case is situated, which can help to understand how the case is influenced by the social, cultural, and historical factors of its environment.

Limitations of Case Study Research

There are several limitations of case study research, including:

- Limited generalizability : Case studies are typically focused on a single case or a small number of cases, which limits the generalizability of the findings. The unique characteristics of the case may not be applicable to other contexts or populations, which may limit the external validity of the research.

- Biased sampling: Case studies may rely on purposive or convenience sampling, which can introduce bias into the sample selection process. This may limit the representativeness of the sample and the generalizability of the findings.

- Subjectivity: Case studies rely on the interpretation of the researcher, which can introduce subjectivity into the analysis. The researcher’s own biases, assumptions, and perspectives may influence the findings, which may limit the objectivity of the research.

- Limited control: Case studies are typically conducted in naturalistic settings, which limits the control that the researcher has over the environment and the variables being studied. This may limit the ability to establish causal relationships between variables.

- Time-consuming: Case studies can be time-consuming to conduct, as they typically involve a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific case. This may limit the feasibility of conducting multiple case studies or conducting case studies in a timely manner.

- Resource-intensive: Case studies may require significant resources, including time, funding, and expertise. This may limit the ability of researchers to conduct case studies in resource-constrained settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Mixed Methods Research – Types & Analysis

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Quasi-Experimental Research Design – Types...

Phenomenology – Methods, Examples and Guide

Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types...

Triangulation in Research – Types, Methods and...

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 30 January 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organisation, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating, and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyse the case.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

| Research question | Case study |

|---|---|

| What are the ecological effects of wolf reintroduction? | Case study of wolf reintroduction in Yellowstone National Park in the US |

| How do populist politicians use narratives about history to gain support? | Case studies of Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán and US president Donald Trump |

| How can teachers implement active learning strategies in mixed-level classrooms? | Case study of a local school that promotes active learning |

| What are the main advantages and disadvantages of wind farms for rural communities? | Case studies of three rural wind farm development projects in different parts of the country |

| How are viral marketing strategies changing the relationship between companies and consumers? | Case study of the iPhone X marketing campaign |

| How do experiences of work in the gig economy differ by gender, race, and age? | Case studies of Deliveroo and Uber drivers in London |

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

Unlike quantitative or experimental research, a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

If you find yourself aiming to simultaneously investigate and solve an issue, consider conducting action research . As its name suggests, action research conducts research and takes action at the same time, and is highly iterative and flexible.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience, or phenomenon.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews, observations, and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data .

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis, with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results , and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyse its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, January 30). Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved 22 July 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/case-studies/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, correlational research | guide, design & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, descriptive research design | definition, methods & examples.

- First Online: 14 December 2017

Cite this chapter

- Marta Strumińska-Kutra 4 &

- Izabela Koładkiewicz 5

6063 Accesses

6 Citations

The main aim of the chapter is to discuss the case study method. We shall begin by confronting its definition. It is quite a challenge, as researchers representing various paradigms embark on this type of research project. These paradigms define the way we perceive the explored reality, our chances of understanding/cognizing it, and the acceptable research methods. As a consequence, not only is the case study subject to various definitions, but it is also employed to achieve manifold goals). Despite these differences, we can point out a number of characteristics that distinguish case study method; they shall be the focus of our discussion. As much as possible, we shall take into account the variety of perspectives in case study-based research, or recommend to readers the sources where they can find more detailed information on a particular issue. In this chapter, the presentation of premises and types of case studies will be followed by a manual, guiding readers in their endeavor to design their own research using the method discussed.

Author’s Note:

This chapter is substantially revised version of a chapter published in Jemielniak, D. ed. (2012) Badania jakościowe, PWN: Warszawa.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Case Study Research

The theory contribution of case study research designs

The concept of strategy, as referred to by Robert Yin ( 2003a , b ), Norman Denzin and Yvonne Lincoln ( 2005 ), means research process design. Here, we shall use it interchangeably with two other terms: approach (Creswell 2007 ) and method. The latter is understood broadly as a set of directives and rules based on ontological and epistemological assumptions, indicating certain ways of conducting research. “Strategy ” and “method” are also referred to as synonyms of the case study methodology (Mills et al. 2010 ).

Even if the starting point of our research is interest in a particular case, we need to bolster our case with a theoretical framework, which will serve as a point of reference for research results.

We must remember that sampling should also involve documents, articles, posts on Internet fora, place and time of observation, and so on.

Here, “case” refers rather to a happening, an expression, or a statement that does not match the emerging pattern, and not to “case” understood as a bounded system/phenomenon.

In fact, the analysis is far less structured and multistage. It comprises abundant feedback and requires the researcher to revert to theoretical reflection; there are periods of “creative impotence” and the process is affected by the other publications read by researchers during the process.

Aaltio, I., & Heilmann, P. (2010). Case Study as a Methodological Approach. In A. J. Mills, G. Durepos, & E. Wiebe (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Case Study Research (pp. 66–76). London: Sage.

Google Scholar

Babbie, E. (2016). The Practice of Social Research (14th ed.). Belmont: Wadsworth/Cengage Learning.

Belz, F. M., & Binder, J. K. (2017). Sustainable Entrepreneurship: A Convergent Process Model. Business Strategy and the Environment, 26 (1), 1–17.

Article Google Scholar

Burawoy, M. (1998). The Extended Case Method. Sociological Theory, 16 , 4–33.

Charmaz, K. (2005). Grounded Theory in the 21st Century. Application for Advancing Social Justice Studies. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research (3rd ed., pp. 507–535). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis . London: Sage.

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design. Choosing Among Five Approaches . Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Davis, R. J. (2010). Case Study Database. In A. J. Mills, G. Durepos, & E. Wiebe (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Case Study Research (pp. 79–80). London: Sage.

Denis, J.-L., Lamothe, L., & Ann, L. (2001). The Dynamics of Collective Leadership and Strategic Change in Pluralistic Organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 44 , 809–837.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). Introduction. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research (3rd ed., pp. 1–32). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1991). Better Stories and Better Constructs. The Case for Rigor and Comparative Logic. The Academy of Management Review, 16 , 620–627.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory Building From Cases. Opportunities and Challenges. The Academy of Management Review, 50 , 25–32.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12 , 219–245.

Foucault, M. (1979). Discipline and Punish: The birth of the Prison . New York: Vintage.

Gawer, A., & Philipps, N. (2013). Institutional Work as Logics Shift: The Case of Intel’s Transformation to Platform Leader. Organization Studies, 34 , 1035–1071.

Gerring, J. (2004). What Is a Case Study and What Is It Good for? American Political Science Review, 98 , 341–354.

Gerring, J. (2007). Case Study Research. Principles and Practices . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research . Chicago: Aldine.

Hammersley, M., & Atkinson, P. (1992). Ethnography. Principles in Practice . London: Routledge.

Hassard, J., & Kelemen, M. (2010). Paradigm Plurality in Case Study Research. In A. J. Mills, G. Durepos, & E. Wiebe (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Case Study Research (pp. 147–152). London: Sage.

Haverland, M., & Yanow, D. (2012). A Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Public Administration Research Universe: Surviving Conversations on Methodologies and Methods. Public Administration Review, 72 , 401–408.

Hijmans, E., & Wester, F. (2010). Comparing Case Study with Other Methodologies. In A. J. Mills, G. Durepos, & E. Wiebe (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Case Study Research (pp. 176–179). London: Sage.

Kostera, M. (2008). Współczesne koncepcje zarządzania . Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Wydziału Zarządzania UW.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry . Beverly Hills: Sage.

Lipset, S. M., Trow, M. A., & Coleman, J. S. (1956). Union Democracy . Glencoe: Free Press.

Martin, J. A., & Eisenhardt, K. M. (2010). Rewiring: Cross-Business-Unit Collaborations in Multibusiness Organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 53 (2), 265–301.

Maxwell, J. A. (1996). Qualitative Research Design . Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Michels, R. (1915). Political Parties . New York: Hearst’s International Library.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook . London: Sage.

Mills, A. J., Durepos, G., & Wiebe, E. (Eds.). (2010). Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . London: Sage Publications.

Moriceau, J.-L. (2010). Generalizability. In A. J. Mills, G. Durepos, & E. Wiebe (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Case Study Research (pp. 419–422). London: Sage.

Morse, J. M., & Richards, L. (2002). Readme First for a User’s Guide to Qualitative Methods . Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Rządca, R., & Strumińska-Kutra, M. (2016). Local Governance and Learning: In Search of a Conceptual Framework. Local Government Studies, 42 (6), 916–937. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2016.1223632 .

Seawright, J., & Gerring, J. (2008). Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research. A Menu of Qualitative and Quantitative Options. Political Research Quarterly, 61 , 294–308.

Sharma, B. (2010). Postpositivism. In A. J. Mills, G. Durepos, & E. Wiebe (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Case Study Research (pp. 701–703). London: Sage.

Silverman, D. (2001). Interpreting Qualitative Data. Methods of Analysing Talk, Text and Interaction (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

Silverman, D. (2005). Doing Qualitative Research. A Practical Handbook (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

Stake, R. E. (2005). Qualitative Case Study. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research (3rd ed., pp. 443–466). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Stake, R. E., & Trumbull, D. J. (1982). Naturalistic Generalization. Review Journal of Philosophy and Social Science, 7 , 1–12.

Wadham, H., & Warren, R. C. (2014). Telling Organizational Tales: The Extended Case Method in Practice. Organizational Research Methods, 17 (1), 5–22.

Yin, R. K. (2003a). Case Study Research. Design and Methods . Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Yin, R. K. (2003b). Applications of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Yin, R. K. (2010). Case Study Protocol. In A. J. Mills, G. Durepos, & E. Wiebe (Eds.), Encyclopaedia of Case Study Research (pp. 84–86). London: Sage.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

VID Specialized University, Oslo, Norway

Marta Strumińska-Kutra

Kozminski University, Warsaw, Poland

Izabela Koładkiewicz

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Teesside University Business School, Teesside University, Middlesbrough, United Kingdom

Malgorzata Ciesielska

Akademia Leona Koźmińskiego, Warsaw, Poland

Dariusz Jemielniak

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Strumińska-Kutra, M., Koładkiewicz, I. (2018). Case Study. In: Ciesielska, M., Jemielniak, D. (eds) Qualitative Methodologies in Organization Studies. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65442-3_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65442-3_1

Published : 14 December 2017

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-65441-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-65442-3

eBook Packages : Business and Management Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- General & Introductory Accounting

- Corporate Finance

Lessons in Corporate Finance: A Case Studies Approach to Financial Tools, Financial Policies, and Valuation, 2nd Edition

ISBN: 978-1-119-53783-0

Digital Evaluation Copy

Paul Asquith , Lawrence A. Weiss

An intuitive introduction to fundamental corporate finance concepts and methods

Lessons in Corporate Finance, Second Edition offers a comprehensive introduction to the subject, using a unique interactive question and answer-based approach. Asking a series of increasingly difficult questions, this text provides both conceptual insight and specific numerical examples. Detailed case studies encourage class discussion and provide real-world context for financial concepts. The book provides a thorough coverage of corporate finance including ratio and pro forma analysis, capital structure theory, investment and financial policy decisions, and valuation and cash flows provides a solid foundational knowledge of essential topics. This revised and updated second edition includes new coverage of the U.S. Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 and its implications for corporate finance valuation.

Written by acclaimed professors from MIT and Tufts University, this innovative text integrates academic research with practical application to provide an in-depth learning experience. Chapter summaries and appendices increase student comprehension. Material is presented from the perspective of real-world chief financial officers making decisions about how firms obtain and allocate capital, including how to:

- Manage cash flow and make good investment and financing decisions

- Understand the five essential valuation methods and their sub-families

- Execute leveraged buyouts, private equity financing, and mergers and acquisitions

- Apply basic corporate finance tools, techniques, and policies

Lessons in Corporate Finance , Second Edition provides an accessible and engaging introduction to the basic methods and principles of corporate finance. From determining a firm’s financial health to valuation nuances, this text provides the essential groundwork for independent investigation and advanced study.

PAUL ASQUITH is the Gordon Y. Billard professor of finance at M.I.T.'s Sloan School. He is a specialist in corporate finance and has written on all areas of corporate finance including mergers, LBOs, equity issues, dividend policy, and more.

LAWRENCE A. WEISS is professor of International Accounting at Tufts University. He is a specialist in accounting and finance and has written on corporate bankruptcy, firm performance, international accounting, mergers, and more.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Financial analysis

- Finance and investing

- Corporate finance

Six Rules for Effective Forecasting

- From the July–August 2007 Issue

When Providing Wait Times, It Pays to Underpromise and Overdeliver

- October 21, 2020

Give Your Employees Specific Goals and the Freedom to Figure Out How to Reach Them

- Cathy Engelbert

- February 25, 2019

Putting the Balanced Scorecard to Work

- Robert S. Kaplan

- David P. Norton

- From the September–October 1993 Issue

Strategic Analysis for More Profitable Acquisitions

- Alfred Rappaport

- From the July 1979 Issue

Stop Letting Quarterly Numbers Dictate Your Strategy

- David Hersh

- December 13, 2016

Upgrade Your Company’s Image—and Valuation

- James McNeill Stancill

- From the January 1984 Issue

How Struggling Businesses Can Renegotiate Rent

- Nikodem Szumilo

- Thomas Wiegelmann

- May 05, 2020

Real-World Way to Manage Real Options

- Tom Copeland

- Peter Tufano

- From the March 2004 Issue

What's It Worth?: A General Manager's Guide to Valuation

- Timothy A. Luehrman

- From the May–June 1997 Issue

Hedging Customers

- Rashi Glazer

- From the May 2003 Issue

A Refresher on Payback Method

- April 18, 2016

No More Cozy Management Buyouts

- Louis Lowenstein

- From the January 1986 Issue

You Can Make Your Sales Data a Lot Better with a Little Discipline

- June 13, 2017

Strategy: The Uniqueness Challenge

- Todd Zenger

- From the November 2013 Issue

Can Nokia Reinvent Itself Again?

- Rita Gunther McGrath

- Rita McGrath

- April 16, 2015

When Good Customers Are Bad

- Remko van Hoek

- David S. Evans

- From the September 2005 Issue