- Search Search Please fill out this field.

What Is Brexit?

The referendum, the article 50 negotiating period, brexit negotiations.

- Arguments for and Against

Brexit Economic Response

June 2017 general election.

- Scotland Referendum

Upsides for Some

U.k.-eu trade after brexit, impact on the u.s..

- Who's Next to Leave the EU?

The Bottom Line

- International Markets

Brexit Meaning and Impact: The Truth About the U.K. Leaving the EU

Adam Hayes, Ph.D., CFA, is a financial writer with 15+ years Wall Street experience as a derivatives trader. Besides his extensive derivative trading expertise, Adam is an expert in economics and behavioral finance. Adam received his master's in economics from The New School for Social Research and his Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in sociology. He is a CFA charterholder as well as holding FINRA Series 7, 55 & 63 licenses. He currently researches and teaches economic sociology and the social studies of finance at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/adam_hayes-5bfc262a46e0fb005118b414.jpg)

Gordon Scott has been an active investor and technical analyst or 20+ years. He is a Chartered Market Technician (CMT).

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/gordonscottphoto-5bfc26c446e0fb00265b0ed4.jpg)

Brexit is a portmanteau of the words "British" and "exit" that was coined to refer to the U.K.'s decision in a June 23, 2016, referendum to leave the European Union (EU). Brexit took place at 11 p.m. Greenwich Mean Time, Jan. 31, 2020.

On Dec. 24, 2020, the U.K. and the EU struck a provisional free-trade agreement ensuring the free trade of goods without tariffs or quotas. However, key details of the future relationship remain uncertain, such as trade in services, which make up 80% of the U.K. economy. This prevented a no-deal Brexit, which would have been significantly damaging to the U.K. economy.

A provisional agreement was approved by the U.K. parliament on Jan. 1, 2021. It was approved by the European Parliament on April 28, 2021. While the deal, known as the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA), allowed tariff- and quota-free trade in goods, U.K.-EU trade still faces customs checks. This means that commerce is not as smooth as when the U.K. was a member of the EU.

Key Takeaways

- Brexit refers to Britain's exit from the European Union.

- Brexit took place on Jan. 31, 2020, following the June 2016 referendum in the country.

- The Leave side received 51.9% of the vote, while the Remain side got 48.1%.

- Negotiations took place between the U.K. and the EU between 2017 and 2019 on the terms of a divorce deal.

- There was a transition period following Brexit that expired on Dec. 31, 2020.

Investopedia / Ellen Lindner

The Leave side won the June 2016 referendum with 51.9% of the ballot, or 17.4 million votes, while Remain received 48.1% or 16.1 million votes. Voter turnout was 72.2%. The results were tallied on a U.K.-wide basis, but the overall figures conceal stark regional differences: 53.4% of English voters supported Brexit, compared to just 38% of Scottish voters.

Because England accounts for the vast majority of the U.K.'s population, support there swayed the result in Brexit's favor. If the vote were conducted only in Wales (where Leave voters also won), Scotland, and Northern Ireland, Brexit would have received less than 45% of the vote.

The result defied expectations and roiled global markets, causing the British pound to fall to its lowest level against the dollar in 30 years. Former Prime Minister David Cameron, who called the referendum and campaigned for the U.K. to remain in the EU, announced his resignation the following day. He was replaced as leader of the Conservative Party and Prime Minister by Theresa May in July 2016.

The process of leaving the EU formally began on March 29, 2017, when May triggered Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty. The U.K. initially had two years from that date to negotiate a new relationship with the EU.

Following a snap election on June 8, 2017, May remained the country's leader. However, the Conservatives lost their outright majority in Parliament and agreed on a deal with the Democratic Unionist Party. This later caused May some difficulty getting her Withdrawal Agreement passed in Parliament.

Talks began on June 19, 2017. Questions swirled around the process, partly because Britain's constitution is unwritten and because no country has left the EU using Article 50 before. A similar move, though, happened when Algeria left the EU's predecessor after gaining independence from France in 1962, and Greenland, which was a self-governing territory, left Denmark through a special treaty in 1985.

On Nov. 25, 2018, Britain and the EU agreed on a 599-page Withdrawal Agreement, a Brexit deal that touched upon issues such as citizens' rights, the divorce bill, and the Irish border. Parliament first voted on this agreement on Jan. 15, 2019. Members of Parliament voted 432 to 202 to reject the agreement, the biggest defeat for a government in the House of Commons in recent history.

May stepped down as party leader on June 7, 2019, after failing three times to get the deal she negotiated with the EU approved by the House of Commons. The following month, Boris Johnson, a former Mayor of London, foreign minister, and editor of The Spectator , was elected prime minister.

Johnson, a hardline Brexit supporter, campaigned on a platform to leave the EU by the October deadline "do or die" and said he was prepared to leave the EU without a deal. The U.K. and EU negotiators agreed on a new divorce deal on Oct. 17. The main difference from May's deal was that the Irish backstop clause was replaced with a new arrangement.

Another historic moment occurred in Aug. 2019 when Prime Minister Boris Johnson requested that the Queen suspend Parliament from mid-September until Oct. 14, and she approved. This was seen as a ploy to stop members of Parliament from blocking a chaotic exit and some even called it a coup of sorts. The Supreme Court's 11 judges unanimously deemed the move unlawful on Sept. 24 and reversed it.

The negotiating period also led Britain's political parties to face their own crises. Lawmakers left both the Conservative and Labour parties in protest. There were allegations of antisemitism in the Labour Party, and Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn was criticized for his handling of the issue. In September, Johnson expelled 21 MPs for voting to delay Brexit.

The U.K. was expected to leave the EU by Oct. 31, 2019, but Parliament voted to force the government to seek an extension to the deadline and also delayed a vote on the new deal.

Boris Johnson then called for a general election. In the Dec. 12 election, the third general election in less than five years, Johnson's Conservative Party won a huge majority of 364 seats in the House of Commons out of 650 seats. It managed this despite receiving only 42% of the vote due to its opponents being fractured between multiple parties.

Britain's lead negotiator in the talks with Brussels was David Davis. He was a Yorkshire member of Parliament (MP) until July 9, 2018, when he resigned. He was replaced by housing minister Dominic Raab as Brexit secretary. Raab resigned in protest over May's deal on Nov. 15, 2018. He was replaced by health and social care minister Stephen Barclay the following day.

The EU's chief negotiator was Michel Barnier, a French politician.

Preparatory talks exposed divisions in the two sides' approaches to the process. The U.K. wanted to negotiate the terms of its withdrawal alongside the terms of its post-Brexit relationship with Europe, while Brussels wanted to make sufficient progress on divorce terms by Oct. 2017, only then moving on to a trade deal. In a concession that both pro- and anti-Brexit commentators took as a sign of weakness, U.K. negotiators accepted the EU's sequenced approach.

Citizens' Rights

One of the most politically thorny issues faced by Brexit negotiators was the rights of EU citizens living in the U.K. and U.K. citizens living in the EU.

The Withdrawal Agreement allowed for the free movement of EU and U.K. citizens until the end of the transition or implementation period. Citizens were allowed to keep their residency rights if they continued to work, had sufficient resources, or were related to someone who did. To upgrade their residence status to permanent, they had to apply to the host nation. The rights of these citizens were revocable if Britain left without ratifying a deal.

"EU net migration, while still adding to the population as a whole, has fallen to a level last seen in 2009. We are also now seeing more EU8 citizens—those from Central and Eastern European countries, for example, Poland—leaving the U.K. than arriving," said Jay Lindop, Director of the Centre for International Migration, in a government quarterly report released in Feb. 2019.

Britain's government fought over the rights of EU citizens to remain in the U.K. after Brexit, publicly airing domestic divisions over migration. Following the referendum and Cameron's resignation, May's government concluded that it had the right under the "royal prerogative" to trigger Article 50 and begin the formal withdrawal process on its own.

The U.K. Supreme Court intervened, ruling that Parliament had to authorize the measure, and the House of Lords amended the resulting bill to guarantee the rights of EU-born residents. The House of Commons, which had a Tory majority at the time, struck the amendment down, and the unamended bill became law on March 16, 2017.

Conservative opponents of the amendment argued that unilateral guarantees eroded Britain's negotiating position, while those in favor of it said EU citizens should not be used as bargaining chips.

Some of the economic concerns included the fact that EU migrants were greater contributors to the economy than their U.K. counterparts. "Leave" supporters, though, read the data as pointing to foreign competition for scarce jobs in Britain.

Brexit Financial Settlement

The Brexit bill was the financial settlement the U.K. owed Brussels following its withdrawal.

The Withdrawal Agreement didn't mention a specific figure, but it was estimated to be up to £32.8 billion, according to Downing Street. The total sum included the financial contribution the U.K. would make during the transition period because it was an EU member state and owed a contribution toward the EU's outstanding 2020 budget commitments.

The U.K. also received funding from EU programs during the transition period and a share of its assets at the end of it, which included the capital it paid to the European Investment Bank (EIB).

A Dec. 2017 agreement resolved this long-standing sticking point that threatened to derail negotiations entirely. Barnier's team launched the first volley in May 2017 with the release of a document listing the 70-odd entities it would take into account when tabulating the bill. The Financial Times estimated that the gross amount requested would be €100 billion. Net of certain U.K. assets, the final bill would be "in the region of €55bn to €75bn."

Davis' team, meanwhile, refused EU demands to submit the U.K.'s preferred methodology for tallying the bill. In August, he told the BBC he would not commit to a figure by October, the deadline for assessing "sufficient progress" on issues such as the bill.

The following month he told the House of Commons that Brexit bill negotiations could go on "for the full duration of the negotiation."

Davis presented this refusal to the House of Lords as a negotiating tactic, but domestic politics probably explained his reticence. Boris Johnson, who campaigned for Brexit, called EU estimates "extortionate" on July 11, 2017, and agreed with a Tory MP that Brussels could "go whistle" if they wanted "a penny."

In her Sept. 2017 speech in Florence, however, May said the U.K. would "honor commitments we have made during the period of our membership." Michel Barnier confirmed to reporters in October 2019 that Britain would pay what was owed.

The Northern Irish Border

The new Withdrawal Agreement replaced the controversial Irish backstop provision with a protocol. According to the revised deal, the entire U.K. left the EU customs union upon Brexit, but Northern Ireland continued following EU regulations and VAT laws for goods, while the U.K. government collected the VAT on behalf of the EU.

This meant there was a limited customs border in the Irish Sea with checks at major ports. The Northern Ireland assembly can vote on this arrangement up to four years after the end of the transition period.

The backstop emerged as the main reason for the Brexit impasse. It was a guarantee that there was no "hard border" between Northern Ireland and Ireland. It was an insurance policy that kept Britain in the EU customs union with Northern Ireland following EU single market rules.

The backstop, which was meant to be temporary and was superseded by a subsequent agreement, could only be removed if both Britain and the EU gave their consent.

May was unable to garner enough support for her deal due to it. Euroskeptic MPs wanted her to add legally binding changes as they feared it would compromise the country's autonomy and could last indefinitely. EU leaders refused to remove it and also ruled out a time limit on granting Britain the power to remove it. On March 11, 2019, the two sides signed a pact in Strasbourg that did not change the Withdrawal Agreement but added "meaningful legal assurances." But it wasn't enough to convince hardline Brexiteers.

For decades during the second half of the 20th century, violence between Protestants and Catholics marred Northern Ireland, and the border between the U.K. countryside and the Republic of Ireland to the south was militarized. The 1998 Good Friday Agreement turned the border almost invisible, except for speed limit signs, which switch from miles per hour in the north to kilometers per hour in the south.

Negotiators in the U.K. and EU worried about the consequences of reinstating border controls, as Britain had to do in order to end freedom of movement from the EU. Yet leaving the customs union without imposing customs checks at the Northern Irish border or between Northern Ireland and the rest of Britain left the door wide open for smuggling . This significant and unique challenge was one of the reasons soft Brexit advocates cited in favor of staying in the EU's customs union and perhaps its single market.

The issue was further complicated by the Tories' choice of the Northern Irish Democratic Unionist Party as a coalition partner. The party opposed the Good Friday Agreement and, unlike the Conservative leader at the time, campaigned for Brexit.

Under the Good Friday Agreement, the U.K. government was required to oversee Northern Ireland with "rigorous impartiality." That proved difficult for a government that depended on the cooperation of a party with an overwhelmingly Protestant support base and historical connections to Protestant paramilitary groups.

Arguments for and Against Brexit

Leave voters based their support for Brexit on a variety of factors, including the European debt crisis , immigration, terrorism, and the perceived drag of Brussels' bureaucracy on the U.K. economy.

Britain was wary of the European Union's projects, which Leavers felt threatened the U.K.'s sovereignty; the country never opted into the European Union's monetary union, meaning that it used the pound instead of the euro . It also remained outside the Schengen Area, meaning that it did not share open borders with a number of other European nations.

Opponents of Brexit also cited a number of rationales for their position:

- The risk involved in pulling out of the EU's decision-making process, given that it was the largest destination for U.K. exports

- The economic and societal benefits of the EU's four freedoms: the free movement of goods, services, capital, and people across borders

A common thread in both arguments was that leaving the EU would destabilize the U.K. economy in the short term and make the country poorer in the long term.

In July 2018, May's cabinet suffered another shake-up when Boris Johnson resigned as the U.K.'s Foreign Minister and David Davis resigned as Brexit Minister over May's plans to keep close ties to the EU. Johnson was replaced by Jeremy Hunt, who favored a soft Brexit.

Some state institutions backed the Remainers' economic arguments: Bank of England governor Mark Carney called Brexit "the biggest domestic risk to financial stability" in March 2016, and the following month, the Treasury projected lasting damage to the economy under any of three possible post-Brexit scenarios:

- European Economic Area (EEA) membership

- A negotiated bilateral trade deal

- World Trade Organization (WTO) membership

Adapted from HM Treasury analysis: the long-term economic impact of EU membership and the alternatives, April 2016.

Leave supporters discounted such economic projections under the label "Project Fear." A pro-Brexit outfit associated with the U.K. Independence Party (UKIP), which was founded to oppose EU membership, responded by saying that the Treasury's "worst-case scenario of £4,300 per household is a bargain-basement price for the restoration of national independence and safe, secure borders."

Although Leavers stressed issues of national pride, safety, and sovereignty, they also mustered economic arguments. For example, Boris Johnson said on the eve of the vote, "EU politicians would be banging down the door for a trade deal " the day after the vote, in light of their "commercial interests."

Vote Leave, the official pro-Brexit campaign, topped the "Why Vote Leave" page on its website with the claim that the U.K. could save £350 million per week: "We can spend our money on our priorities like the NHS [National Health Service], schools, and housing."

In May 2016, the U.K. Statistics Authority, an independent public body, said the figure was gross rather than net, which was "misleading and undermines trust in official statistics." A mid-June poll by Ipsos MORI, however, found that 47% of the country believed the claim.

The day after the referendum, Nigel Farage, who co-founded UKIP and led it until that November, disavowed the figure and said that he was not closely associated with Vote Leave. May also declined to confirm Vote Leave's NHS promises since taking office.

Though Britain officially left the EU, 2020 was a transition and implementation period. Trade and customs continued during that time, so there wasn't much on a day-to-day basis that seemed different to U.K. residents. Even so, the decision to leave the EU had an effect on Britain's economy.

The country's GDP growth slowed down to around 1.7% in 2018 from 2.2% in 2016 and 2.4% in 2017 as business investment slumped. The IMF predicted that the country's economy would grow at 1.3% in 2019 and 1.4% in 2020. Instead, growth was 1.6% in 2019 but -11% in 2020. GDP rebounded, however, touching 7.6% in 2021 before slowing to 4.1% in 2022.

The U.K. unemployment rate hit a 44-year low at 3.9% in the three months leading up to Jan. 2019. Experts attribute this to employers preferring to retain workers instead of investing in new major projects.

While the fall in the value of the pound after the Brexit vote helped exporters, the higher price of imports was passed onto consumers and had a significant impact on the annual inflation rate. CPI inflation hit 3.1% in the 12 months leading up to Nov. 2017, a near six-year high that well exceeded the Bank of England's 2% target. Inflation fell in 2018 with the decline in oil and gas prices but soared after the global pandemic, rising 8.7% in the 12 months preceding April 2023.

A July 2017 report by the House of Lords cited evidence that U.K. businesses would have to raise wages to attract native-born workers following Brexit, which was "likely to lead to higher prices for consumers."

International trade was expected to fall due to Brexit, even with the possibility of a raft of free trade deals. Dr. Monique Ebell, former associate research director at the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, forecasted a -22% reduction in total U.K. goods and services trade if EU membership was replaced by a free trade agreement.

Other free trade agreements were not predicted to pick up the slack. In fact, Ebell saw a pact with the BRIICS (Brazil, Russia, India, Indonesia, China, and South Africa) boosting total trade by 2.2% while a pact with the U.S., Canada, Australia, and New Zealand was expected to do slightly better, at 2.6%.

"The single market is a very deep and comprehensive trade agreement aimed at reducing non-tariff barriers," Ebell wrote in Jan. 2017, "while most non-EU [free trade agreements] seem to be quite ineffective at reducing the non-tariff barriers that are important for services trade."

On April 18, May called for a snap election to be held on June 8, despite previous promises not to hold one until 2020. Polling at the time suggested May would expand on her slim Parliamentary majority of 330 seats (there are 650 seats in the Commons). Labor gained rapidly in the polls, however, aided by an embarrassing Tory flip-flop on a proposal for estates to fund end-of-life care.

The Conservatives lost their majority, winning 318 seats to Labor's 262. The Scottish National Party won 35, with other parties taking 35. The resulting hung Parliament cast doubts on May's mandate to negotiate Brexit and led the leaders of Labor and the Liberal Democrats to call on May to resign.

Speaking in front of the prime minister's residence at 10 Downing Street, May batted away calls for her to leave her post, saying, "It is clear that only the Conservative and Unionist Party"—the Tories' official name—"has the legitimacy and ability to provide that certainty by commanding a majority in the House of Commons." The Conservatives struck a deal with the Democratic Unionist Party of Northern Ireland, which won 10 seats, to form a coalition.

May presented the election as a chance for the Conservatives to solidify their mandate and strengthen their negotiating position with Brussels. But this backfired.

In the wake of the election, many expected the government's Brexit position to soften, and they were right. May released a Brexit white paper in July 2018 that mentioned an "association agreement" and a free-trade area for goods with the EU. David Davis resigned as Brexit secretary, and Boris Johnson resigned as Foreign Secretary in protest.

But the election also increased the possibility of a no-deal Brexit. The Financial Times predicted that the result made May more vulnerable to pressure from Euroskeptics and her coalition partners. This was evident with the Irish backstop tussle.

With her position weakened, May struggled to unite her party behind her deal and keep control of Brexit.

Scotland's Independence Referendum

Politicians in Scotland pushed for a second independence referendum in the wake of the Brexit vote, but the results of the June 8, 2017, election cast a pall over their efforts. The Scottish National Party (SNP) lost 21 seats in the Westminster Parliament, and on June 27, 2017, Scottish First Minister Nicola Sturgeon said her government at Holyrood would "reset" its timetable on independence to focus on delivering a "soft Brexit."

Not one Scottish local area voted to leave the EU, according to the U.K.'s Electoral Commission, though Moray came close at 49.9%. The country as a whole rejected the referendum by 62.0% to 38.0%.

But because Scotland only contains 8.4% of the U.K.'s population, its vote to Remain (along with that of Northern Ireland, which accounts for just 2.9% of the U.K.'s population) was vastly outweighed by support for Brexit in England and Wales.

Scotland joined England and Wales to form Great Britain in 1707, and the relationship has been tumultuous at times. The SNP, which was founded in the 1930s, had just six of 650 seats in Westminster in 2010. The following year, however, it formed a majority government in the devolved Scottish Parliament at Holyrood, partly owing to its promise to hold a referendum on Scottish independence.

2014 Scottish Independence Referendum

That referendum, held in 2014, saw the pro-independence side lose with 44.7% of the vote. Turnout was 84.6%. Far from putting the independence issue to rest, though, the vote fired up nationalist support.

The SNP won 56 of 59 Scottish seats at Westminster the following year, overtaking the Lib Dems to become the third-largest party in the U.K. overall. Britain's electoral map suddenly showed a glaring divide between England and Wales, which was dominated by Tory blue with the occasional patch of Labour red, and all-yellow Scotland.

When Britain voted to leave the EU, Scotland fulminated. A combination of rising nationalism and strong support for Europe led almost immediately to calls for a new independence referendum. On Nov. 3, 2017, when the Supreme Court ruled that devolved national assemblies such as Scotland's parliament could not veto Brexit, the demands grew louder.

On March 13 of that year, Sturgeon called for a second referendum to be held in the autumn of 2018 or spring of 2019. Holyrood backed her by a vote of 69 to 59 on March 28, the day before May's government triggered Article 50.

Sturgeon's preferred timing was significant since the two-year countdown initiated by Article 50 ended in the spring of 2019 when the politics surrounding Brexit could be particularly volatile.

What Would Independence Look Like?

Scotland's economic situation also raised questions about its hypothetical future as an independent country. The crash in oil prices dealt a blow to government finances. In May 2014, its government forecasted 2015–2016 tax receipts from North Sea drilling of £3.4 billion to £9 billion but only collected £60 million, less than 1% of the forecasts' midpoint.

In reality, these figures were hypothetical since Scotland's finances were not (and are not) fully devolved, but the estimates were based on the country's geographical share of North Sea drilling, so they illustrated what it might expect as an independent nation.

The debate over what currency an independent Scotland would use was revived. Former SNP leader Alex Salmond, who was Scotland's First Minister until Nov. 2014, told The Financial Times that the country could abandon the pound and introduce its own currency, allowing it to float freely or pegging it to sterling. He ruled out joining the euro, but others contended that it would be required for Scotland to join the EU. Another possibility would be to use the pound, which would mean forfeiting control over monetary policy .

On the other hand, a weak currency that floats on global markets can be a boon to U.K. producers who export goods. Industries that rely heavily on exports could actually see some benefit.

In 2023, the top 10 exports from the U.K. were (in USD):

- Gems, precious metals: $62 billion

- Aircraft, engines, and parts manufacturing: $23.4 billion

- Vehicles: $18.8 billion

- Pharmaceuticals: $16.5 billion

- Oil refining: $12.2 billion

- Petroleum and gas: $9.8 billion

- Off-road vehicle manufacturing: $7.2 billion

- Jewelry manufacturing: $6.9 billion

- Organic chemicals: $5.9 billion

- Clothing: $5.7 billion

Some sectors were prepared to benefit from the exit. Multinationals listed on the FTSE 100 saw earnings rise as a result of a soft pound. A weak currency was also a boon to the tourism, energy, and service industries.

In May 2016, the State Bank of India, India's largest commercial bank, suggested that Brexit would benefit India economically. While leaving the Eurozone meant that the U.K. no longer had unfettered access to Europe's single market, it would allow for more focus on trade with India. India would also have more wiggle room if the U.K. were no longer under European trade rules and regulations.

May advocated a "hard" Brexit. By that, she meant that Britain should leave the EU's single market and customs union and negotiate a trade deal to govern their future relationship. These negotiations would have been conducted during a transition period once a divorce deal was ratified.

The Conservatives' poor showing in the June 2017 snap election called popular support for a hard Brexit into question. Many in the press speculated that the government could take a softer line. The Brexit White Paper released in July 2018 revealed plans for a softer Brexit. It was too soft for many MPs in her party and too audacious for the EU.

The white paper said the government planned to leave the EU single market and customs union. However, it proposed the creation of a free trade area for goods, which would "avoid the need for customs and regulatory checks at the border and mean that businesses would not need to complete costly customs declarations. And it would enable products to only undergo one set of approvals and authorizations in either market, before being sold in both." This meant the U.K. would follow EU single market rules regarding goods.

The White Paper acknowledged that a borderless customs arrangement with the EU—one that allowed the U.K. to negotiate free trade agreements with third countries—was "broader in scope than any other that exists between the EU and a third country."

The government was correct that there was no example of this kind of relationship in Europe. The four broad precedents that existed were the EU's relationship with Norway, Switzerland, Canada, and WTO members.

The Norway Model: Join the EEA

The first option was for the U.K. to join Norway, Iceland, and Lichtenstein in the European Economic Area (EEA), which provides access to the EU's single market for most goods and services (agriculture and fisheries are excluded). At the same time, the EEA is outside the customs union, so Britain could have entered into trade deals with non-EU countries.

But the arrangement was hardly a win-win. The U.K. would be bound by some EU laws while losing its ability to influence those laws through the country's European Council and European Parliament voting rights. In Sept. 2017, May called this arrangement an unacceptable "loss of democratic control."

David Davis expressed interest in the Norway model in response to a question he received at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce in Washington. "It's something we've thought about but it's not at the top of our list," he said. He was referring specifically to the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), which, like the EEA, offers access to the single market but not the customs union.

EFTA was once a large organization, but most of its members left to join the EU. Today, it comprises Norway, Iceland, Lichtenstein, and Switzerland; all but Switzerland are also members of the EEA.

The Switzerland Model

Switzerland's relationship with the EU, which is governed by around 20 major bilateral pacts with the bloc, is broadly similar to the EEA arrangement. Along with these three, Switzerland is a member of the European Free Trade Association. Switzerland helped set up the EEA, but its people rejected membership in a 1992 referendum.

The country allows the free movement of people and is a member of the passport-free Schengen Area. It is subject to many single-market rules without having much say in making them.

It is outside the customs union, allowing it to negotiate free trade agreements with third countries; usually, but not always, it has negotiated alongside the EEA countries. Switzerland has access to the single market for goods (with the exception of agriculture) but not services (except insurance). It pays a modest amount into the EU's budget.

Brexit supporters who wanted to "take back control" wouldn't have embraced the concessions the Swiss made on immigration, budget payments, and single market rules. The EU would probably not have wanted a relationship modeled on the Swiss example, either: Switzerland's membership in EFTA but not the EEA, Schengen but not the EU, is a messy product of the complex history of European integration and—not surprisingly—a referendum.

The Canada Model: A Free Trade Agreement

A third option was to negotiate a free trade agreement with the EU along the lines of the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), a pact the EU finalized but didn't fully ratify with Canada. The most obvious problem with this approach is that the U.K. had only two years from triggering Article 50 to negotiate such a deal. The EU refused to discuss a future trading relationship until December of that year at the earliest.

To give a sense of how tight that timetable was, CETA negotiations began in 2009 and concluded in 2014. But just over half of the EU's 28 national parliaments actually ratified the deal. Persuading the rest could take years. Even subnational legislatures can stand in the way of a deal: the Walloon regional parliament, which represents fewer than four million mainly French-speaking Belgians, single-handedly blocked CETA for a few days in 2016.

In order to extend the two-year deadline for leaving the EU, Britain needed unanimous approval from the EU. Several U.K. politicians, including Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond, stressed the need for a transitional deal of a few years so that (among other reasons) Britain could negotiate EU and third-country trade deals. But this notion was met with resistance from hard-line Brexiteers.

Problems With a CETA-Style Agreement

In some ways, comparing Britain's situation to Canada's is misleading. Canada already enjoys free trade with the U.S. through the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which was built on the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). This means that a trade deal with the EU was not as crucial as it is for the U.K. Canada's and Britain's economies are also very different: CETA does not include financial services, one of Britain's biggest exports to the EU.

Speaking in Florence in Sept. 2017, May said the U.K. and EU "can do so much better" than a CETA-style trade agreement since they were beginning from the "unprecedented position" of sharing a body of rules and regulations. She did not elaborate on what "much better" looked like besides calling on both parties to be "creative as well as practical."

Monique Ebell, formerly of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, stressed that even with an agreement in place, non-tariff barriers were likely to be a significant drag on Britain's trade with the EU. She expected total U.K. foreign trade—not just flows to and from the EU—under an EU-U.K. trade pact. She reasoned that free-trade deals did not generally handle services trade well. Services are a major component of Britain's international trade; the country enjoys a trade surplus in that segment, which is not the case for goods.

Free trade deals also struggle to rein in non- tariff barriers. Admittedly, Britain and the EU started from a unified regulatory scheme, but divergences would only multiply post-Brexit.

WTO: Go It Alone

If Britain and the EU weren't able to come to an agreement about their relationship, they would have had to revert to WTO terms. But this default solution wouldn't have been straightforward either. Since Britain was a WTO member through the EU, it would have to split tariff schedules with the bloc and divvy out liabilities arising from ongoing trade disputes.

Trading with the EU on WTO terms was the "no-deal" scenario the Conservative government presented as an acceptable fallback, though most observers see this as a negotiating tactic. In July 2017, U.K. Secretary of State for International Trade Liam Fox said, "People talk about the WTO as if it would be the end of the world. But they forget that is how they currently trade with the United States, with China, with Japan, with India, with the Gulf, and our trading relationship is strong and healthy."

But for certain industries, the EU's external tariff would have hit hard: Britain exports 77% of the cars it manufactures, and 58% of these go to Europe. The EU levies 10% tariffs on imported cars. Monique Ebell of the NIESR estimated that leaving the EU single market would reduce overall U.K. goods and services trade—not just that with the EU—by 22% to 30%.

Nor would the U.K. only be giving up its trade arrangements with the EU; under any of the scenarios above, it would probably have lost the trade agreements the bloc struck with 63 developing countries, as well as progress in negotiating other deals. Replacing these and adding new ones would have been an uncertain prospect. In a Sept. 2017 interview with Politico, Trade Secretary Liam Fox said his office, which was formed in July 2016, turned away some developing countries looking to negotiate free trade deals because it lacked the capacity to negotiate.

Fox wanted to roll the terms of existing EU trade deals over into new agreements, but some countries were unwilling to give Britain (66 million people, $2.6 trillion GDP) the same terms as the EU (excluding Britain, around 440 million people, $13.9 trillion GDP).

Companies in the U.S. across a wide variety of sectors have made large investments in the U.K. over many years. In fact, American corporations have derived 9% of global foreign affiliate profit from the United Kingdom since 2000. The U.S. also hires a lot of Brits, making U.S. companies one of the U.K.'s largest job markets. The output of U.S. affiliates in the United Kingdom was $129.3 billion in 2021.

The United Kingdom plays a vital role in corporate America's global infrastructure, from assets under management (AUM) to international sales and research and development (R&D) advancements.

American companies have viewed Britain as a strategic gateway to other countries in the European Union. Brexit is believed to jeopardize the affiliate earnings and stock prices of many companies strategically aligned with the United Kingdom.

American companies and investors that have exposure to European banks and credit markets may be affected by credit risk. European banks may have to replace $123 billion in securities depending on how the exit unfolds. Furthermore, U.K. debt may not be included in European banks' emergency cash reserves , creating liquidity problems. European asset-backed securities have been in decline since 2007.

Who's Next to Leave the EU?

Political wrangling over the EU wasn't limited to Britain. Even following Britain's departure, most EU members had strong Euroskeptic movements that, while they struggled to win power at the national level, heavily influenced the tenor of national politics in the years that followed. There is still a chance that such movements could secure referendums on EU membership in a few countries at some point in the future.

In May 2016, global research firm Ipsos released a report showing that a majority of respondents in Italy and France believe their countries should hold a referendum on EU membership.

The fragile Italian banking sector has driven a wedge between the EU and the Italian government, which provided bailout funds to save mom-and-pop bondholders from being "bailed-in," as EU rules stipulate. The government abandoned its 2019 budget when the EU threatened it with sanctions. It lowered its planned budget deficit from 2.5% of GDP to 2.04%.

Matteo Salvini, the far-right head of Italy's Northern League and the country's deputy prime minister, called for a referendum on EU membership hours after the Brexit vote, saying, "This vote was a slap in the face for all those who say that Europe is their own business and Italians don't have to meddle with that."

The Northern League has an ally in the populist Five Star Movement, whose founder, former comedian Beppe Grillo, called for a referendum on Italy's membership in the euro—though not the EU. The two parties formed a coalition government in 2018 and made Giuseppe Conte prime minister. Conte ruled out the possibility of "Italexit" in 2018 during the budget standoff.

Marine Le Pen, the leader of France's Euroskeptic National Front, hailed the Brexit vote as a win for nationalism and sovereignty across Europe: "Like a lot of French people, I'm very happy that the U.K. people held on and made the right choice. What we thought was impossible yesterday has now become possible." She lost the French presidential election to Emmanuel Macron in May 2017, gaining just 33.9% of votes. He won the election again in 2022, beating Le Pen once more.

Macron has warned that the demand for "Frexit" will grow if the EU does not see reforms. According to a European Social Survey poll between 2020 and 2022, 16% of French citizens want the country to leave the EU, down from 24.3% between 2016 and 2017.

When Did Britain Officially Leave the European Union?

Britain officially left the EU on Jan. 31, 2020, at 11 p.m. GMT. The move came after a referendum voted in favor of Brexit on June 23, 2016.

What Were the Reasons Behind Brexit?

There were many reasons why Britain voted to leave the European Union. But some of the main issues behind Brexit included a rise in nationalism, immigration, political autonomy, and the economy. The Leave side garnered almost 52% of the votes, while the Remain side received about 48%.

How Many Countries Are Part of the EU Post-Brexit?

Britain's departure from the European Union left 27 member states. They are Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, and Sweden.

The European Union was established in Nov. 1993 with the Maastricht Treaty. The original members included Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Fifteen other countries would gain membership in the union.

Rising nationalist sentiment, coupled with concerns over the economy and British sovereignty, led the majority of voters in the U.K. to vote to leave the EU. Britain left the union at the end of Jan. 2020 in what is commonly called Brexit. But the move didn't come without challenges. It required two years of negotiating a deal and a year-long transition period before everything became final.

BBC. " Brexit: What Is the Transition Period? "

The New York Times. " Brexit Trade Deal Gets a Final OK From E.U. Parliament ."

The New York Times. " Pound Rises as Britain and E.U. Announce a Post-Brexit Trade Deal . "

The New York Times. " E.U. Referendum: After the ‘Brexit’ Vote ."

BBC. " EU Referendum Results ."

CNN. " Theresa May Becomes New British Prime Minister ."

Gov.UK. " Prime Minister’s Letter to Donald Tusk Triggering Article 50 ."

Library of Congress. " BREXIT: Sources of Information ."

Gov.UK. " Withdrawal Agreement and Political Declaration ."

UK Parliament. " Government Loses 'Meaningful Vote' in the Commons ."

Gov.UK. " Prime Minister's Statement in Downing Street: 24 May 2019 ."

UK Parliament. " A No-Deal Brexit: The Johnson Government ."

European Union. " Brexit ."

BBC. " UK Results: Conservatives Win Majority ,"

Gov.UK. " Agreement on the Withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community, as Endorsed by Leaders at a Special Meeting of the European Council on 25 November 2018 ," Pages 20 and 28.

Office for National Statistics. " Migration Statistics Quarterly Report: February 2019 ,"

Center for Economic Performance. " CEP Brexit Analysis No. 5 ."

Office for Budget Responsibility. " Fiscal Risks Report ," Page 172.

European Commission. " Essential Principles on Financial Settlement ," Pages 6–8.

The Financial Times. " Britain’s €100bn Brexit Bill in Context ."

Politico. "' Britain Will Not Commit to Brexit Bill Figure by October,' says David Davis ."

UK Parliament, House of Hansard Commons. " EU Exit Negotiations ."

UK Parliament, House of Hansard Commons. " Oral Answers to Questions ."

Gov.UK. " PM's Florence Speech: a New Era of Cooperation and Partnership Between the UK and the EU ."

European Commission. " Protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland ."

European Commission. " Remarks by President Jean-Claude Juncker at Today's Joint Press Conference with UK Prime Minister Theresa May ."

Gov.UK. " The Belfast Agreement ," Page 4.

UK Parliament. " The Short-Term Effects of Leaving the EU ."

HM Government. " HM Treasury Analysis: The Long-Term Economic Impact of EU Membership and the Alternatives ," Page 6.

HM Government. " HM Treasury Analysis: the Long-term Economic Impact of EU Membership and the Alternatives ," Page 8.

The Guardian. " George Osborne: Brexit Would Force Income Tax Up by 8p in Pound ."

The Financial Times. " EU 'Foolish' to Erect Trade Barriers Against Britain ."

Vote Leave. " Why Vote Leave ."

U.K. Statistics Authority. " UK Statistics Authority Statement on the Use of Official Statistics on Contributions to the European Union ."

Ipsos MORI. " Ipsos MORI June 2016 Political Monitor ," Page 6.

ITV. " Nigel Farage labels £350m NHS Promise 'A Mistake.' "

Office for National Statistics. " Gross Domestic Product: Year on Year growth: CVM SA % ."

IMF. " World Economic Outlook, July 2019 ."

Office for National Statistics. " Labour Market Economic Commentary: March 2019 ."

Office for National Statistics. " Consumer Price Inflation, UK: April 2023 ."

Office for National Statistics. " Consumer Price Inflation, UK: November 2018 ."

UK Parliament. " Chapter 3: Adapting the UK Labour Market ."

Economic and Social Research Council. " Will New Trade Deals Soften the Blow of Hard Brexit? "

BBC. " Election 2017 Results ."

Gov.UK. " PM Statement: General Election 2017 ."

Gov.UK. " The Future Relationship Between the United Kingdom and the European Union ," Page 15.

The Financial Times. " How the Election Result Affects Brexit ."

Politico. " Nicola Sturgeon 'Resets' Timetable on Independence Referendum ."

The Electoral Commission. " Results and Turnout at the EU Referendum ."

The Electoral Commission. " Report: Scottish Independence Referendum ."

The Financial Times. " Scotland Could Abandon Currency Union With UK, Says Alex Salmond ."

IBIS. " Biggest Exporting Industries in the UK in 2023 ."

Gov.UK. " The Future Relationship Between the United Kingdom and the European Union ," Page 3.

Gov.UK. " The Future Relationship Between the United Kingdom and the European Union ," Pages 7 and 11.

Gov.UK. " The Future Relationship Between the United Kingdom and the European Union ," Pages 11–12.

Politico. " David Davis: Norway Model Is One Option for UK After Brexit ."

Reuters. " Brexit on WTO Terms Would Not Be the End of the World: Fox ."

Politico. " Liam Fox: Britain Does Not Have Capacity to Strike Trade Deals Now ."

International Trade Administration. " Market Overview ."

Ipsos. " Ipsos Brexit Poll, May 2016 ," Page 6.

European Commission. " Commission Concludes That an Excessive Deficit Procedure Is No Longer Warranted for Italy at This Stage ."

The Wall Street Journal. " Who Else Wants to Break Up With the EU ."

Quartz. " 'This Is a Blow to Europe': Leaders in the EU React to Brexit ."

NPR. " French President Emmanuel Macron Beats His Far-Right Rival to Win Reelection ."

The Guardian. " French Presidential Election May 2017 – Full Second Round Results and Analysis ."

The Guardian. " Support for Leaving EU Has Fallen Significantly Across Bloc Since Brexit ."

European Union. " Country Profiles ."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/GettyImages-1128676901-4e85a8615e614390b2b4cfcf9983c4e2.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

- Share full article

Advertisement

What Is Brexit? And What Happens Next?

By Benjamin Mueller Updated Jan. 31, 2020

Brexit is happening.

After three years of haggling in the British Parliament, convulsions at the top of the government and pleas for Brussels to delay its exit, Britain closes the book on nearly half a century of close ties with Europe on Jan. 31.

Its split with the European Union was sealed when Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s Conservative Party won a resounding victory in December’s general election. That supplied Mr. Johnson with the parliamentary majority he needed to pass legislation in early January setting the terms of Britain’s departure, a goal that repeatedly eluded his predecessor, Theresa May. European lawmakers gave the plan their blessing later in the month.

Mr. Johnson, a brash proponent of withdrawal, will now guide the country through the most critical stage of Brexit: trade negotiations that will determine how closely linked Britain remains with the bloc.

Little will change overnight. At midnight in Brussels on Jan. 31 – 11 p.m. in London, a reminder that the European Union sets the terms of departure – Britain will begin an 11-month transition in which it continues to abide by the bloc’s rules and regulations while deciding what sort of Brexit to pursue.

What ultimately emerges as Britain parts ways with the European Union could determine the shape of the nation and its place in the world for decades. What follows is a basic guide to Brexit: what it is, how it turned into a political mess and how it may ultimately be resolved.

Let’s start with the basics

Why “Brexit”?

A portmanteau of the words Britain and exit, Brexit caught on as shorthand for the proposal that Britain split from the European Union and change its relationship to the bloc on trade, security and migration.

Britain has been debating the pros and cons of membership in a European community of nations almost from the moment the idea was broached. It held its first referendum on membership in what was then called the European Economic Community in 1975, less than three years after it joined. At the time, 67 percent of voters supported staying in the bloc.

But that was hardly the end of the debate.

In 2013, Prime Minister David Cameron promised a national referendum on European Union membership with the idea of settling the question once and for all. The options offered to voters were broad and vague — Remain or Leave — and Mr. Cameron was convinced that Remain would win handily.

That turned out to be a serious miscalculation.

As Britons went to the polls on June 23, 2016, a refugee crisis had made migration a subject of political rage across Europe. Meanwhile, the Leave campaign was hit with accusations that it had relied on lies and that it had broken election laws.

In the end, a withdrawal from the bloc, however ill-defined, emerged with the support of 52 percent of voters.

Debate settled? Hardly.

Brexit advocates had saved for another day the tangled question of what should come next. Even now that Britain has settled the terms of its departure, it remains unclear what sort of relationship with the European Union it wants for the future, a matter that could prove just as divisive as the debate over withdrawal.

How did the referendum vote break down?

Most voters in England and Wales supported Brexit, particularly in rural areas and smaller cities. That overcame majority support for remaining in the European Union among voters in London, Scotland and Northern Ireland. See a detailed map of the vote .

Young people overwhelmingly voted against leaving, while older voters supported it.

Why is it such a big deal?

Europe is Britain’s most important export market and its biggest source of foreign investment, while membership in the bloc has helped London cement its position as a global financial center.

With some regularity, major businesses have announced that they are leaving Britain because of Brexit, or have at least threatened to do so. The list of companies thinking about relocating includes Airbus , which employs 14,000 people and supports more than 100,000 other jobs.

The government has projected that in 15 years, the country’s economy would be 4 percent to 9 percent smaller if Britain left the European Union than if it remained, depending on how it leaves.

Mrs. May had promised that Brexit would mean an end to free movement — that is, the right of people from elsewhere in Europe to live and work in Britain. Working-class people who see immigration as a threat to their jobs viewed that as a triumph. But an end to free movement would cut both ways, and the prospect was dispiriting for young Britons hoping to study or work abroad.

How did we end up with a Jan. 31 deadline?

Before Parliament approved Mr. Johnson’s withdrawal agreement in January, just about the only clear decision it made on Brexit was to give formal notice in 2017 to quit, under Article 50 of the European Union’s Lisbon Treaty, a legal process setting it on a two-year path to departure. That made March 29, 2019, the formal divorce date.

But departure was delayed when it became clear that hard-line pro-Brexit Conservative lawmakers would not accept Mrs. May’s withdrawal deal, which they said would trap Britain in the European market.

The European Union agreed to push the date back to April 12. But the new deadline did not bring about any more agreement in London, and Mrs. May was forced to plead yet again for more time. This time, European leaders insisted on a longer delay, and set Oct. 31 as the date.

Mr. Johnson took office in July, and vowed to take Britain out of the bloc by that deadline, with or without a deal. But opposition lawmakers and rebels in his own party seized control of the Brexit process, and moved to block a no-deal withdrawal, which would have meant Britain leaving without being able to cushion the blow of a sudden divorce.

That forced Mr. Johnson to seek an extension , something he had said he would rather be “dead in a ditch” than do. European leaders agreed to extend the deadline by three months, to Jan. 31, as Britain considered its options.

Ultimately, Mr. Johnson persuaded enough opposition lawmakers to agree to an early general election. His Conservative Party won an 80-seat majority, the largest since Margaret Thatcher in 1987.

What happens next?

Much as Jan. 31 marks a symbolic milestone, it is merely the beginning of a potentially more volatile chapter of the turbulent divorce, in which political and business leaders jockey over what sort of Brexit will come to pass.

Every path holds risks for Mr. Johnson, all the more so after an election in which he was buoyed by voters in ex-Labour heartland seats in northern and central England who stand to suffer from trading barriers with Europe.

And the clock is ticking: The end of the transition period is Dec. 31. Any request to extend that deadline would have to be made by June.

Mr. Johnson, though, has repeatedly vowed to complete the departure by the end of the year. If he sticks to his word, Britain and the European Union will have to strike a deal governing future trade across the English Channel at an unusually fast pace. (It took seven years, for example, for the European Union and Canada to negotiate their 2016 trade deal.)

That will involve negotiations over trade in manufactured goods as well as services, which make up the bulk of the British economy. Should the two sides fail to reach an agreement, even a narrow one that leaves some issues for next year, Britain would crash out of the bloc with no deal at all, raising the prospect of tariffs and border disruption that would mirror the sort of no-deal Brexit that lawmakers have long feared.

Among the points of contention will be Mr. Johnson’s wish to break from European standards on labor, the environment and product safety. The more space Britain puts between its rules and Europe’s, the bloc’s leaders have said, the more they will hamper Britain’s access to the European market. Any restrictions of that sort would threaten British jobs, reliant as many of them are on European customers.

The Brexit timeline

We’ve had no shortage of Brexit-related things to explain to explain in recent months—from the Irish backstop and transition periods, to WTO terms and no deal preparations—but it can be hard to understand how all of the pieces fit together.

So we’ve put together a timeline of the Brexit process. It briefly sums up the key issues and events you might want to know about, presenting them in chronological order (as far as that’s possible) to make it clearer how they all fit together. Throughout, there are links to related content we’ve published if you want to take a deeper dive into certain areas.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

Already in place: Article 50 and the EU Withdrawal Act

After the UK voted to leave the EU in June 2016, the first key step on the road to Brexit was the triggering of Article 50 —the EU’s legal provision for countries wishing to leave the EU. The government did this following parliamentary approval in March 2017 , setting a two-year countdown to when we will officially leave the EU: on 29 March 2019.

It’s possible that Article 50 could be extended or revoked . We’ve written more about this here .

The next key step was for parliament to pass the EU Withdrawal Act , which happened in June 2018. It sets out that, after we exit, the European Union will no longer be the source of any UK laws. That means new EU laws won’t affect the UK, although the government will transfer many existing EU laws (which do affect us) over into UK law.

But the process of exiting is not quite as clean as it might seem. Although we are officially out of the EU from 29 March 2019, the full terms of the Withdrawal Act will probably not apply until further down the line, because UK and EU negotiators don’t think they’ll manage to sort out the whole of our future relationship by next March.

The heart of current negotiations: the Withdrawal Agreement and Transition Period

The UK and EU negotiators agreed on the text of a withdrawal agreement in November 2018.

This agreement sets out the exact terms of the UK and EU’s relationship immediately after exit day on 29 March—but it does not amount to the final word on what the UK and EU’s future relationship will be. Rather, it is a transitional arrangement, designed to make the separation process smoother. It covers things like trade, law, and immigration.

A key part of the withdrawal agreement is that there will be a transition period , running from exit day on 29 March until the end of 2020 (although the UK can apply to extend it by one or two years ). During transition the UK would officially be out of the EU and not be represented on EU bodies, but would still have the same obligations as an EU member. That includes remaining in the EU’s customs union and single market, contributing to the EU’s budget, and following EU law.

The main reason for the transition period is that the UK and EU don’t think they have enough time to agree all the terms of their future relationship by 29 March 2019. The transition period is designed to give them more time to iron out all the details of their future relationship, including a possible free trade deal (we get on to what the future deal could look like further down).

- We explain the difference between the transition period and a free trade agreement in more detail here .

- We also have an explainer on the “ divorce bill ”, which is the amount of money we have to pay the EU as part of leaving.

If a withdrawal agreement is signed off it would come into effect on 29 March 2019. That would then lead to a transition period until the end of 2020, and from 2021 the UK and EU would enter a new relationship, possibly underpinned by a free trade deal.

Possible roadblocks: the Irish backstop

Before it’s made official, the withdrawal agreement has to be approved by the UK parliament. The UK government and EU negotiators have agreed a draft text, but many MPs object to it, and say they will not vote for it.

MPs were set to vote on it on 11 December 2018, but the government has postponed this as it expected to lose the vote in parliament. The Prime Minister is currently seeking to “secure further assurances” from the EU on the agreement before she brings it back to parliament.

One of the main points of contention is the Irish backstop.

- We’ve explained more about what the backstop means here , and why it matters in negotiations here .

In short, the backstop is a position of last resort that kicks in if the UK and EU fail to agree any kind of future relationship by the end of the transition period.

It’s designed to ensure that the Irish border remains open as it is today, even if all other negotiations fail. Some MPs don’t like it because it would result in what’s called a soft Brexit where the UK remains highly aligned with EU markets and rules.

Some also object because the UK can only opt out of the backstop if a joint panel of UK and EU representatives think it’s no longer necessary. The withdrawal agreement states that this will only occur if an alternative arrangement is found). This means the UK cannot leave it without EU consent.

The Democratic Unionist Party in Northern Ireland opposes the backstop because it would lead to some checks on goods entering Northern Ireland from the rest of the UK, with Northern Ireland more closely aligned to EU customs rules. They think this threatens the integrity of the union between the Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK.

Possible roadblocks: the meaningful vote and the possibility of no deal

Parliament’s decision on whether to approve the withdrawal has been called the meaningful vote . If parliament votes in favour of the withdrawal agreement, it’s set to come into force on 29 March 2019.

MPs will also have a chance to suggest amendments to the withdrawal agreement, and if the deal passes in an amended form, it’s possible that the government would have to go back to the EU to seek approval for an amended deal. It’s hard to know how this would pan out.

If parliament rejects the deal, the government has to make a statement on how it proposes to move forward. Parliament would then vote on that plan of action and could vote on amendments—essentially it could instruct government how to proceed with Brexit. We’ve written more about this here .

That could mean the government has to go back and negotiate further with the EU or accept that no deal can be reached.

A no deal Brexit means leaving without the proposed withdrawal agreement to smooth the exit process. It would likely lead to disruption, with overnight changes in how our borders and trade with the EU are regulated on exit day.

- This piece from the independent think tank Institute for Government explains that there are different ways that “no deal” could unfold, and some of the possible consequences of each scenario.

- We’ve looked into some of the things that could happen in the case of no deal here and here .

- We’ve also explained the meaning of WTO terms —on which the UK would trade with the EU in a no deal scenario.

Possible roadblocks: EU pushback

The EU have agreed the current draft of the withdrawal agreement. However Mrs May is trying to seek further reassurances from the EU on the matter of the backstop, following concerns raised by MPs.

Senior EU figures have repeatedly said that there is no option to renegotiate the agreement itself, but there is room to provide additional “ clarifications and interpretations ” on the backstop issue.

(If any renegotiation were to happen, it is more likely that it would be over the non-binding “political declaration” on the intended future trade relationship than the legally binding withdrawal agreement.)

Would could a future trade agreement look like?

If the withdrawal agreement is approved by parliament, the UK and EU would spend the transition period trying to agree on a future relationship. There would be a possibility to extend the transition period for a set period if both sides agree to do so.

The “ political declaration setting out the framework for the future relationship” (a statement of intent accompanying the withdrawal agreement that isn’t legally binding on its own) states that the UK and EU would form “separate markets and distinct legal orders” in a future relationship.

But it also aims for a future “trading relationship on goods that is as close as possible” with the UK and EU having common rules in some areas, and no tariffs on any trade in goods. This would result in the UK having a fairly close alignment with the EU’s customs territory.

- The political declaration alludes to the possibility of “facilitative arrangements and technologies” to manage customs in a future UK-EU trade deal. Such an approach has previously been called “max fac” and we’ve explained what it means here .

This model of trade deal is closer to the one Norway has with the EU than the one Canada has (two oft-referenced deals in debates over what a UK-EU trade deal could look like). The “Norwegian” model is based on a higher degree of access to EU markets, and a higher degree of following EU rules (although the UK’s deal is unlikely to be as closely aligned as Norway’s). Some continue to advocate a “Canadian” model for a trade deal—based on lower market access and lower levels of EU regulation—although it’s unclear that such a shift could be made this late in the negotiations.

- We explain the Norway and Canada models in more detail here .

Update 13 December 2018

We've updated the piece following recent events.

- By Joël Reland

- Share this:

Was this helpful?

Full Fact fights for good, reliable information in the media, online, and in politics.

Related fac t checks

- What’s the cost of preparing for Brexit?

- Brexit withdrawal deal and future trade deal—what’s the difference?

- Video of French president dancing in nightclub is a deepfake

- Diary of Anne Frank not written by American novelist after WW2

- France has not banned halal slaughter ahead of Ramadan

- Did you find this fact check useful?

Full Fact fights bad information

Bad information ruins lives. It promotes hate, damages people’s health, and hurts democracy. You deserve better.

Making social science accessible

What do the public think about Brexit in 2023?

10 Mar 2023

Public Opinion

UK-EU Relations

Sophie Stowers analyses the latest Redfield and Wilton Strategies/UK in a Changing Europe Brexit tracker poll , highlighting the five key trends across public attitudes towards Brexit from the first few months of 2023.

It has certainly been a busy few weeks when it comes to Brexit. The unveiling of the Windsor Framework , the scrapping of the Northern Ireland Protocol Bill and the continued, albeit glacial, progress of the Retained EU Law Bill through Parliament have given those in Westminster plenty to get on with. But what are the public’s views on the future of the UK-EU relationship?

Using our bimonthly Brexit tracker, which looks at public attitudes across all aspects of Brexit, there are five key findings from the first few months of 2023.

Northern Ireland

This month’s polling was conducted before Rishi Sunak and Ursula Von der Leyen unveiled the Windsor Framework. However, our survey allows us to tap into public attitudes concerning the regulatory barriers facing businesses who trade between GB and NI, and the remit of the European Court of Justice. Our data allows us to surmise that, as a whole, the public may be pretty supportive of the deal Sunak has reached with the EU.

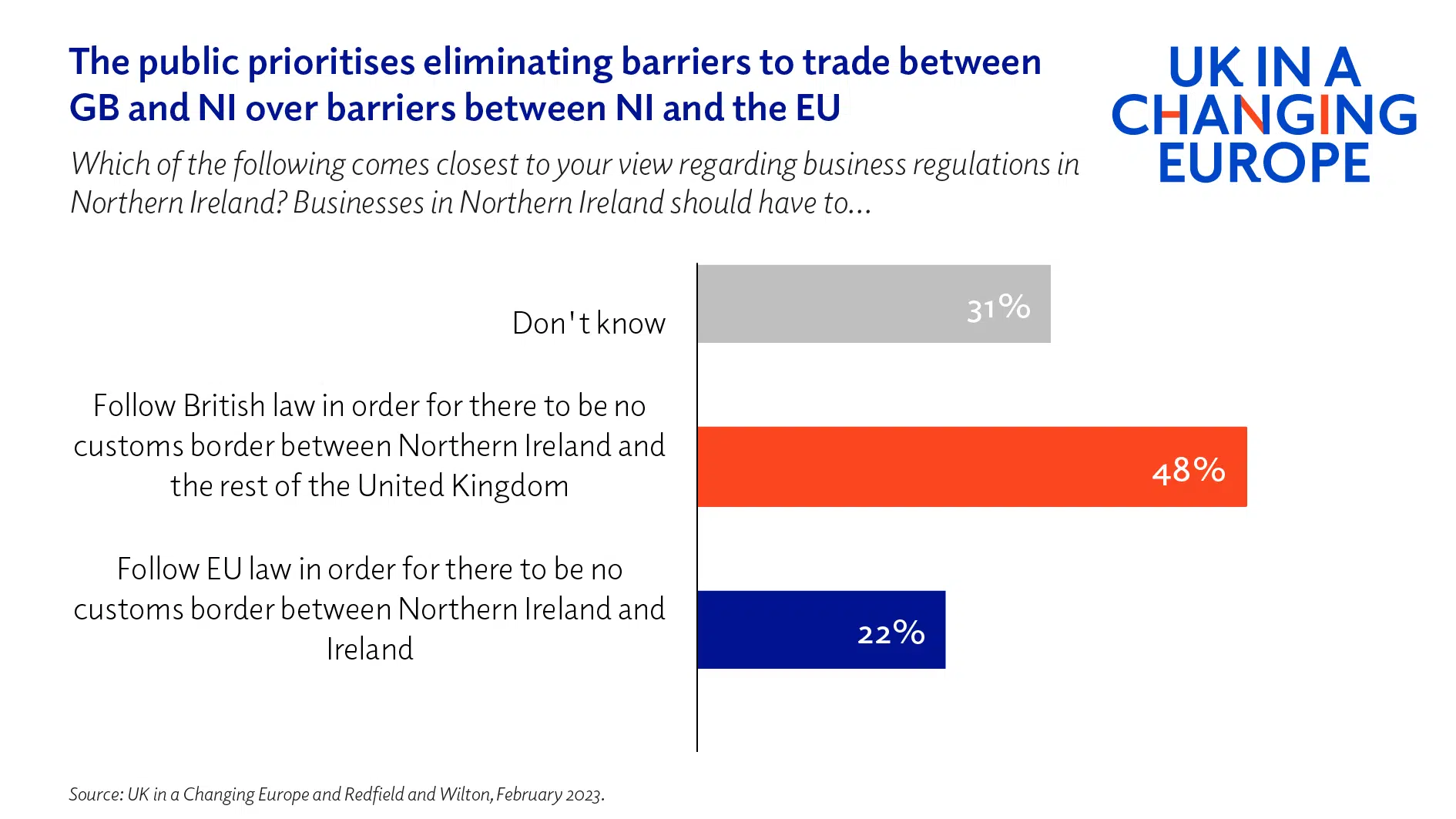

Firstly, voters are twice as likely to prioritise the easing of trade between Great Britain and Northern Ireland as between Northern Ireland and the European Union. The Windsor Framework does indeed put in place measures which make it easier to export products from GB and remain in Northern Ireland by introducing a green and red lane system, reducing checks and paperwork.

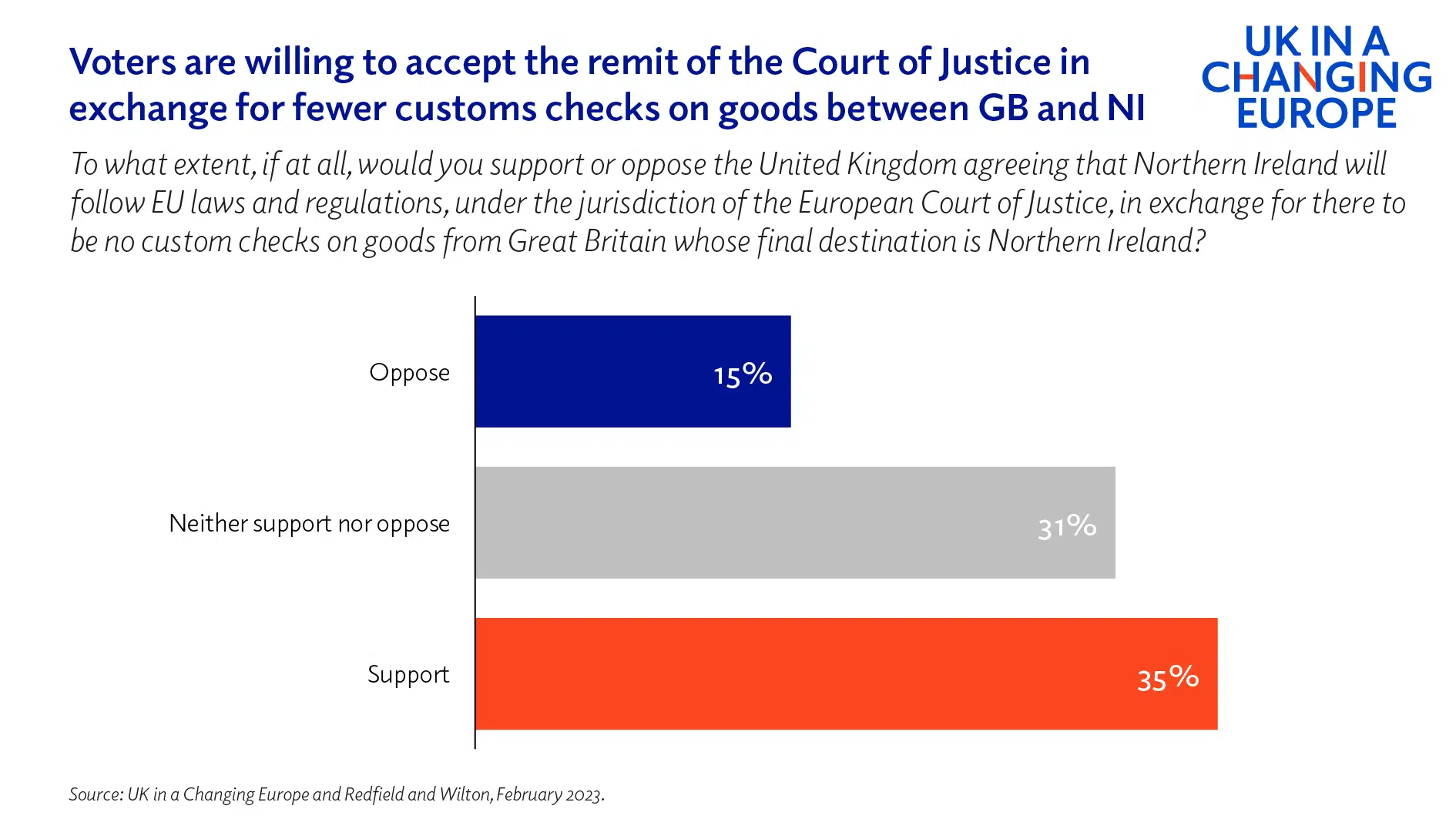

When it comes to the European Court of Justice, while the new deal does little to reduce its role (other than reducing the number of EU laws that will apply in Northern Ireland), this does not seem to be a major concern for the public. We asked our respondents if they would be willing to tolerate a role for the ECJ in the UK-EU relationship in exchange for reduced checks on goods set to remain in Northern Ireland.

The majority of voters either support or are neutral towards ECJ oversight, if this allows fewer checks on goods travelling between GB and NI. This suggests that the public accepts that there is a trade-off between sovereignty and easement of trade, which will be music to the Prime Minister’s ears.

Support for rejoin and another referendum

February’s data shows a slight increase in the number of people who said that they would now vote to re-join the EU if another referendum were to take place. Though some of this increase will be down to sampling variation, it does suggest that we are seeing a gradual increase in the popularity of EU membership amongst voters. The number of 2016 Leave voters who said they would still vote Leave in a second referendum has dropped slightly again to 77%, from 86% a year previously.

However, when asked about re-opening the Brexit question, a large portion of the population (44%) consider the issue of EU membership to be settled. This could suggest that the popularity of ‘rejoin’ in a hypothetical referendum should not be interpreted as support for another vote.

Immigration

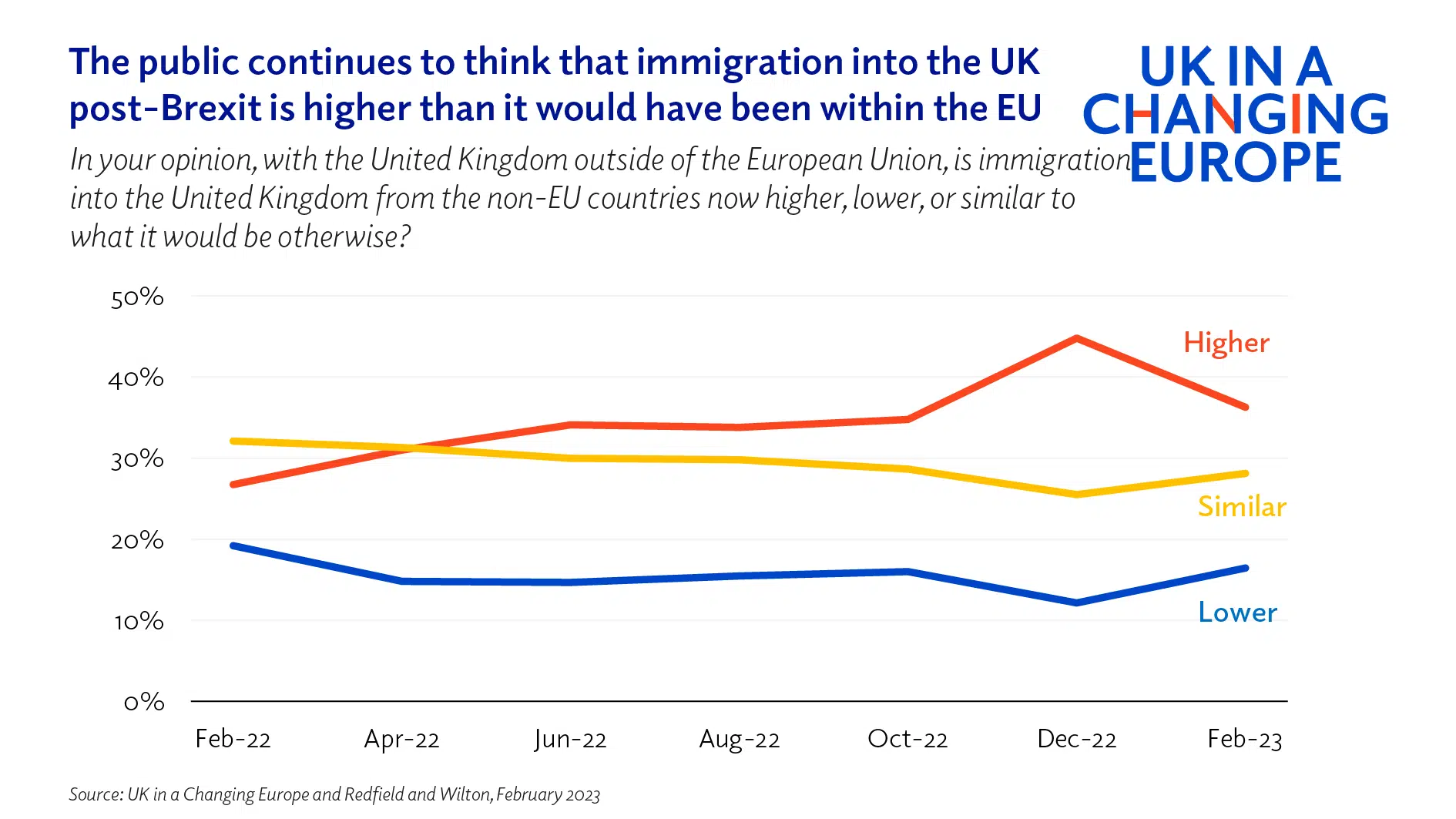

Over the last year, the public has become more likely to say that immigration into the UK from both inside and outside the EU has increased as a result of Brexit. In February we saw a slight drop in this figure, but voters are still more likely to say that immigration into the UK has not reduced as a result of Brexit.

Voters are also more likely (42%) to think that illegal immigration into the United Kingdom is higher than it would have been if the UK has stayed in the EU, including 51% of 2016 Leave voters. The government has, after all failed to agree an alternative to the Dublin Convention with the EU, which would allow the UK to ask other EU countries to ‘take back’ asylum seekers if they had entered via ‘safe countries’ such as France or Italy.

Post-Brexit priorities

When asked what opportunities the UK should take advantage of post-Brexit, voters prioritise the ability to control immigration from the EU into Britain. This is followed by the UK’s ability to sign bilateral trade deals and the ability to redistribute money which would otherwise have been contributed to the EU budget.

Interestingly, we also find that voters are more likely to believe the government has only made use of its ability to diverge from EU law and regulations to a minimal extent, regardless of whether they voted Leave or Remain in 2016. 44% of voters think that the government has either not made use of this ability at all, or only to a limited extent.

The effects of Brexit

The public is split on whether enough time has passed to judge the effect of Brexit: 44% of voters say we are now able to judge the consequences of leaving the EU, compared to 39% who disagree. Interestingly, however, we do see that voters are still more likely to say that the war in Ukraine is having a more tangible impact on their daily lives than Brexit, as they did in December. Before this, a majority of voters would say Covid (or neither Brexit or Covid) was having the most consequential impact day-to-day.

However, 38% of voters say that they have noticed the impact of Brexit ‘a fair amount’ in the last two months, and 35% say that the overall impact of Brexit has been more noticeable than they had thought it would be.

This is particularly evident when we ask voters about economic issues: we find that a majority of voters (57%) say the impact of leaving the EU on the UK economy has been negative, including a third of 2016 voters. In addition, 38% of voters in February said that wages are lower as a result of Brexit, and over 60% say that cost of living is higher.

By Sophie Stowers , researcher, UK in a Changing Europe.

You can download the February 2023 Brexit tracker data tables in full here .

MORE FROM THIS THEME

How the prospect of future homeownership affects vote choice, dissatisfaction with democracy in croatia, apathy in the uk: how does political discontent compare with other european countries, do uk voters feel represented by the major parties, attitudes towards migration for work: the ‘brightest and best’ vs economic and social need, subscribe to the ukice newsletter.

We will not sell or distribute your email address to any third party at any time. View our Privacy Policy .

Subscribe to our newsletter

Recent articles.

The regulatory superpower next door

Joël Reland

17 Apr 2024

Europhoria! Explaining Britain’s Pro-European moment, 1988-92

Dr James Dennison

The Independent Commission on the Constitutional Future of Wales – a different kind of debate?

Dr Anwen Elias

11 Apr 2024

Views expressed in this piece are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily those of UK in a Changing Europe

- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

Become an FT subscriber

Try unlimited access Only $1 for 4 weeks

Then $75 per month. Complete digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Cancel anytime during your trial.

- Global news & analysis

- Expert opinion

- Special features

- FirstFT newsletter

- Videos & Podcasts

- Android & iOS app

- FT Edit app

- 10 gift articles per month

Explore more offers.

Standard digital.

- FT Digital Edition

Premium Digital

Print + premium digital, weekend print + standard digital, weekend print + premium digital.

Today's FT newspaper for easy reading on any device. This does not include ft.com or FT App access.

- 10 additional gift articles per month

- Global news & analysis

- Exclusive FT analysis

- Videos & Podcasts

- FT App on Android & iOS

- Everything in Standard Digital

- Premium newsletters

- Weekday Print Edition

- FT Weekend Print delivery

- Everything in Premium Digital

Essential digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

- Everything in Print

Complete digital access to quality FT journalism with expert analysis from industry leaders. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

Terms & Conditions apply

Explore our full range of subscriptions.

Why the ft.

See why over a million readers pay to read the Financial Times.

International Edition

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

UK to delay start of health and safety checks on EU imports – report

New post-Brexit border checks ‘set to zero’ to avoid what Defra calls risk of serious disruption

The UK government has reportedly told port health authorities it will not “turn on” health and safety checks for EU imports as new post-Brexit border controls begin this month.

A presentation prepared by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) highlighted the risk of “significant disruption” if the new measures were implemented, according to the Financial Times. It made clear that the systems would not be fully ready on time.

In a move designed to avoid big delays, the government said it would ensure the rate of checks was initially “set to zero for all commodity groups”.

The border controls have already been delayed five times over fears that they could cause disruption and further fuel price inflation.

In its presentation, Defra admitted to port health authorities that “challenges” still remained within its systems for registering imports of food and animal products.

These challenges could trigger unmanageable levels of inspections, overwhelming ports, it was reported.

“There is a potential for significant disruption on day one if all commodity codes are turned on at once,” it said.

It was not made clear for how long border checks would be suspended but the presentation was said to indicate that the systems would be “progressively turned on” for different product groups.

Business organisations have repeatedly called for the introduction of the new border checks to be delayed until at least October.

The final big change will come in October, with the government requiring safety and security declarations for medium- and high-risk imports, while also introducing a single trade window, which the government says will reduce the number of forms needed for importers.

As of yet, goods coming from the island of Ireland will not require physical checks but the government has said these will be introduced at some point after 31 October this year.

A Defra spokesperson said: “As we have always said, the goods posing the highest biosecurity risk are being prioritised as we build up to full check rates and high levels of compliance.

“Taking a pragmatic approach to introducing our new border checks minimises disruption, protects our biosecurity and benefits everyone – especially traders.

“There has been extensive engagement with businesses over the past year – with our approach welcomed by several trade associations and port authorities.

“We will continue to work with and support businesses throughout this process to maintain the smooth flow of imported goods.”

- Trade policy

- European Union

- Foreign policy

Sunak rejects offer of youth mobility scheme between EU and UK

New Brexit checks will cause food shortages in UK, importers warn

Brexit plans in ‘complete disarray’ as EU import checks delayed, say businesses