- See us on facebook

- See us on twitter

- See us on youtube

- See us on linkedin

- See us on instagram

Researchers treat depression by reversing brain signals traveling the wrong way

A new study led by Stanford Medicine researchers is the first to reveal how magnetic stimulation treats severe depression: by correcting the abnormal flow of brain signals.

May 15, 2023 - By Nina Bai

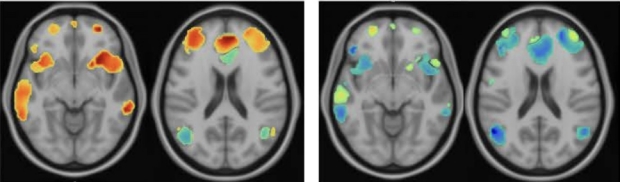

Brain images from a patient with major depression before (left) and after treatment with Stanford neuromodulation therapy, which restores the normal timing of activity in the anterior cingulate cortex. Nolan Williams Lab

Powerful magnetic pulses applied to the scalp to stimulate the brain can bring fast relief to many severely depressed patients for whom standard treatments have failed. Yet it’s been a mystery exactly how transcranial magnetic stimulation, as the treatment is known, changes the brain to dissipate depression. Now, research led by Stanford Medicine scientists has found that the treatment works by reversing the direction of abnormal brain signals.

The findings also suggest that backward streams of neural activity between key areas of the brain could be used as a biomarker to help diagnose depression.

“The leading hypothesis has been that TMS could change the flow of neural activity in the brain,” said Anish Mitra , MD, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in psychiatry and behavioral sciences. “But to be honest, I was pretty skeptical. I wanted to test it.”

Mitra had just the tool to do it. As a graduate student at Washington University in Saint Louis, in the lab of Mark Raichle, MD, he developed a mathematical tool to analyze functional magnetic resonance imaging, or fMRI — commonly used to locate active areas in the brain. The new analysis used minute differences in timing between the activation of different areas to also reveal the direction of that activity.

In the new study , published May 15 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , Mitra and Raichle teamed up with Nolan Williams , MD, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, whose team has advanced the use of magnetic stimulation, personalized to each patient’s brain anatomy, to treat profound depression. The FDA-cleared treatment, known as Stanford neuromodulation therapy , incorporates advanced imaging technologies to guide stimulation with high-dose patterns of magnetic pulses that can modify brain activity related to major depression. Compared with traditional TMS, which requires daily sessions over several weeks or months, SNT works on an accelerated timeline of 10 sessions each day for just five days.

“This was the perfect test to see if TMS has the ability to change the way that signals flow through the brain,” said Mitra, who is lead author of the study. “If this doesn’t do it, nothing will.”

Raichle and Williams are senior authors of the study.

Anish Mitra

Timing is everything

The researchers recruited 33 patients who had been diagnosed with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. Twenty-three received SNT treatment, and 10 received a sham treatment that mimicked SNT but without magnetic stimulation. They compared data from these patients with that of 85 healthy controls without depression.

When they analyzed fMRI data across the whole brain, one connection stood out. In the normal brain, the anterior insula, a region that integrates bodily sensations, sends signals to a region that governs emotions, the anterior cingulate cortex.

“You could think of it as the anterior cingulate cortex receiving this information about the body — like heart rate or temperature — and then deciding how to feel on the basis of all these signals,” Mitra said.

In three-quarters of the participants with depression, however, the typical flow of activity was reversed: The anterior cingulate cortex sent signals to the anterior insula. The more severe the depression, the higher the proportion of signals that traveled the wrong way.

“What we saw is that who’s the sender and who’s the receiver in the relationship seems to really matter in terms of whether someone is depressed,” Mitra said.

“It’s almost as if you’d already decided how you were going to feel, and then everything you were sensing was filtered through that,” he said. “The mood has become primary.”

“That’s consistent with how a lot of psychiatrists see depression,” he added. “Even things that are quite joyful to a patient normally are suddenly not bringing them any pleasure.”

When depressed patients were treated with SNT, the flow of neural activity shifted to the normal direction within a week, coinciding with a lifting of their depression.

Those with the most severe depression — and the most misdirected brain signals — were the most likely to benefit from the treatment.

“We’re able to undo the spatio-temporal abnormality so that people’s brains look like those of normal, healthy controls,” Williams said.

Nolan Williams

A biomarker for depression

A challenge of treating depression has been the lack of insight into its biological mechanisms. If a patient has a fever, there are various tests — for a bacterial or viral infection, for example — that could determine the appropriate treatment. But for a patient with depression, there are no analogous tests.

“This is the first time in psychiatry where this particular change in biology — the flow of signals between these two brain regions — predicts the change in clinical symptoms,” Williams said.

Not everyone with depression has this abnormal flow of neural activity, and it may be rare in less severe cases of depression, Williams said, but it could serve as an important biomarker for triaging treatment for the disorder. “The fMRI data that allows precision treatment with SNT can be used both as a biomarker for depression and a method of personalized targeting to treat its underlying cause,” he said.

“When we get a person with severe depression, we can look for this biomarker to decide how likely they are to respond well to SNT treatment,” Mitra said.

“Behavioral conditions like depression have been difficult to capture with imaging because, unlike an obvious brain lesion, they deal with the subtlety of relationships between various parts of the brain,” said Raichle, who has studied brain imaging for more than four decades. “It’s incredibly promising that the technology now is approaching the complexity of the problems we’re trying to understand."

The researchers plan to replicate the study in a larger group of patients. They also hope others will adopt their analytic technique to uncover more clues about the direction of brain activity hidden in fMRI data. “As long as you have good clean fMRI data, you can study this property of the signals,” Mitra said.

The study was funded by a Brain and Behavior Research Foundation Young Investigator Award, the NIMH Biobehavioral Research Awards for Innovative New Scientists award (grant R01 5R01MH122754-02), Charles R. Schwab, the David and Amanda Chao Fund II, the Amy Roth PhD Fund, the Neuromodulation Research Fund, the Lehman Family, the Still Charitable Trust, the Marshall and Dee Ann Payne Fund, the Gordie Brookstone Fund, the Mellam Family Foundation, and the Baszucki Brain Research Fund.

About Stanford Medicine

Stanford Medicine is an integrated academic health system comprising the Stanford School of Medicine and adult and pediatric health care delivery systems. Together, they harness the full potential of biomedicine through collaborative research, education and clinical care for patients. For more information, please visit med.stanford.edu .

Artificial intelligence

Exploring ways AI is applied to health care

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 18 June 2020

Advances in depression research: second special issue, 2020, with highlights on biological mechanisms, clinical features, co-morbidity, genetics, imaging, and treatment

- Julio Licinio 1 &

- Ma-Li Wong 1

Molecular Psychiatry volume 25 , pages 1356–1360 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

11 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

The current speed of progress in depression research is simply remarkable. We have therefore been able to create a second special issue of Molecular Psychiatry , 2020, focused on depression, with highlights on mechanisms, genetics, clinical features, co-morbidity, imaging, and treatment. We are also very proud to present in this issue a seminal paper by Chottekalapanda et al., which represents some of the last work conducted by the late Nobel Laureate Paul Greengard [ 1 ]. This brings to four the number of papers co-authored by Paul Greengard and published in our two 2020 depression special issues [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ].

The research content of this special depression issue starts with Chottekalapanda et al.’s outstanding contribution aimed at determining whether neuroadaptive processes induced by antidepressants are modulated by the regulation of specific gene expression programs [ 1 ]. That team identified a transcriptional program regulated by activator protein-1 (AP-1) complex, formed by c-Fos and c-Jun that is selectively activated prior to the onset of the chronic SSRI response. The AP-1 transcriptional program modulated the expression of key neuronal remodeling genes, including S100a10 (p11), linking neuronal plasticity to the antidepressant response. Moreover, they found that AP-1 function is required for the antidepressant effect in vivo. Furthermore, they demonstrated how neurochemical pathways of BDNF and FGF2, through the MAPK, PI3K, and JNK cascades, regulate AP-1 function to mediate the beneficial effects of the antidepressant response. This newly identified molecular network provides “a new avenue that could be used to accelerate or potentiate antidepressant responses by triggering neuroplasticity.”

A superb paper by Schouten et al. showed that oscillations of glucocorticoid hormones (GC) preserve a population of adult hippocampal neural stem cells in the aging brain [ 5 ]. Moreover, major depressive disorder (MDD) is characterized by alterations in GC-related rhythms [ 6 , 7 ]. GC regulate neural stem/precursor cells (NSPC) proliferation [ 8 , 9 ]. The adrenals secrete GC in ultradian pulses that result in a circadian rhythm. GC oscillations control cell cycle progression and induce specific genome-wide DNA methylation profiles. Schouten et al. studied primary hippocampal NSPC cultures and showed that GC oscillations induced lasting changes in the methylation state of a group of gene promoters associated with cell cycle regulation and the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. Furthermore, in a mouse model of accelerated aging, they showed that disruption of GC oscillations induced lasting changes in dendritic complexity, spine numbers and morphology of newborn granule neurons. Their results indicate that GC oscillations preserve a population of GR-expressing NSPC during aging, preventing their activation possibly by epigenetic programming through methylation of specific gene promoters. These important observations suggest a novel mechanism mediated by GC that controls NSPC proliferation and preserves a dormant NSPC pool, possibly contributing to neuroplasticity reserve in the aging brain.

MDD has a critical interface with addiction and suicide, which is of immense clinical and research importance [ 10 ]. Peciña et al. have reviewed a growing body of research indicating that the endogenous opioid system is directly involved in the regulation of mood and is dysregulated in MDD [ 11 ]. Halikere et al. provide evidence that addiction associated N40D mu-opioid receptor variant modulates synaptic function in human neurons [ 12 ].

Two papers by Amare et al. and Coleman et al. examine different genetic substrates for MDD, identifying novel depression-related loci as well as studying the interface with trauma [ 13 , 14 ].

The dissection of MDD clinical phenotypes, including their interface with other illnesses is a topic of several articles in this special issue. Belvederi Murri et al. examined the symptom network structure of depressive symptoms in late-life in a large European population in the 19 country Survey of Health, Ageing, and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) (mean age 74 years, 59% females, n = 8557) [ 15 ]. They showed that the highest values of centrality were in the symptoms of death wishes, depressed mood, loss of interest, and pessimism. Another article focused on a specific feature of MDD, namely changes in appetite. Simmons et al. aimed at explaining why some individuals lose their appetite when they become depressed, while others eat more, and brought together data on neuroimaging, salivary cortisol, and blood markers of inflammation and metabolism [ 16 ]. Depressed participants experiencing decreased appetite had higher cortisol levels than other subjects, and their cortisol values correlated inversely with the ventral striatal response to food cues. In contrast, depressed participants experiencing increased appetite exhibited marked immunometabolic dysregulation, with higher insulin, insulin resistance, leptin, c-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin 1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA), and IL-6, and lower ghrelin than subjects in other groups, and the magnitude of their insulin resistance correlated positively with the insula response to food cues. Their findings support the existence of pathophysiologically distinct depression subtypes for which the direction of appetite change may be an easily measured behavioral marker.

Mulugeta et al. studied the association between major depressive disorder and multiple disease outcomes in the UK Biobank ( n = 337,536) [ 17 ]. They performed hypothesis-free phenome-wide association analyses between MDD genetic risk score (GRS) and 925 disease outcomes. MDD was associated with several inflammatory and hemorrhagic gastrointestinal diseases, and intestinal E. coli infections. MDD was also associated with disorders of lipid metabolism and ischemic heart disease. Their results indicated a causal link between MDD and a broad range of diseases, suggesting a notable burden of co-morbidity. The authors concluded that “early detection and management of MDD is important, and treatment strategies should be selected to also minimize the risk of related co-morbidities.” Further information on the shared mechanisms between coronary heart disease and depression in the UK Biobank ( n = 367,703) was explored by Khandaker et al. [ 18 ]. They showed that family history of heart disease was associated with a 20% increase in depression risk; however, a genetic risk score that is strongly associated with CHD risk was not associated with depression. Their data indicate that comorbidity between depression and CHD arises largely from shared environmental factors.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies, Wang et al. examined the interface of depression and anxiety in relation to cancer incidence and mortality [ 19 ]. Their analyses suggest that depression and anxiety may have an etiologic role and prognostic impact on cancer, although there is potential reverse causality.

Several papers in this issue examine imaging in MDD, either to unravel the underlying disease processes or to identify imaging biomarkers of treatment response. Let us first look at the studies focused on elucidating brain circuitry alterations in MDD. Arterial spin labeling (ASL) was used by Cooper et al. to measure cerebral blood flow (CBF; perfusion) in order to discover and replicate alterations in CBF in MDD [ 20 ]. Their analyses revealed reduced relative CBF (rCBF) in the right parahippocampus, thalamus, fusiform, and middle temporal gyri, as well as the left and right insula, for those with MDD. They also revealed increased rCBF in MDD in both the left and the right inferior parietal lobule, including the supramarginal and angular gyri. According to the authors, “these results (1) provide reliable evidence for ASL in detecting differences in perfusion for multiple brain regions thought to be important in MDD, and (2) highlight the potential role of using perfusion as a biosignature of MDD.” Further data on imaging in MDD was provided by a coordinated analysis across 20 international cohorts in the ENIGMA MDD working group. In that paper, van Velzen et al. showed that in a coordinated and harmonized multisite diffusion tensor imaging study there were subtle, but widespread differences in white matter microstructure in adult MDD, which may suggest structural disconnectivity [ 21 ].

Four articles in this special issue examine imaging biomarkers of treatment response. Greenberg et al. studied reward-related ventral striatal activity and differential response to sertraline versus placebo in depressed using functional magnetic resonance imaging while performing a reward task [ 22 ]. They found that ventral striatum (VS) dynamic response to reward expectancy (expected outcome value) and prediction error (difference between expected and actual outcome), likely reflecting serotonergic and dopaminergic deficits, was associated with better response to sertraline than placebo. Their conclusion was that treatment measures of reward-related VS activity may serve as objective neural markers to advance efforts to personalize interventions by guiding individual-level choice of antidepressant treatment. Utilizing whole-brain functional connectivity analysis to identify neural signatures of remission following antidepressant treatment, and to identify connectomic predictors of treatment response, Korgaonkar et al. showed that intrinsic connectomes are a predictive biomarker of remission in major depressive disorder [ 23 ]. Based on their results that team proposed that increased functional connectivity within and between large-scale intrinsic brain networks may characterize acute recovery with antidepressants in depression. Repple et al. created connectome matrices via a combination of T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and tractography methods based on diffusion-weighted imaging severity of current depression and remission status in 464 MDD patients and 432 healthy controls [ 24 ]. Reduced global fractional anisotropy (FA) was observed specifically in acute depressed patients compared to fully remitted patients and healthy controls. Within the MDD patients, FA in a subnetwork including frontal, temporal, insular, and parietal nodes was negatively associated with symptom intensity, an effect remaining when correcting for lifetime disease severity. Their findings provide new evidence of MDD to be associated with structural, yet dynamic, state-dependent connectome alterations, which covary with current disease severity and remission status after a depressive episode. The effects of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), the most effective treatment for depression, on the dentate gyrus (DG) were studied by Nuninga et al. through an optimized MRI scan at 7-tesla field strength, allowing sensitive investigation of hippocampal subfields [ 25 , 26 ]. They documented a large and significant increase in DG volume after ECT, while other hippocampal subfields were unaffected. Furthermore, an increase in DG volume was related to a decrease in depression scores, and baseline DG volume predicted clinical response. These findings suggest that the volume change of the DG is related to the antidepressant properties of ECT, possibly reflecting neurogenesis.

Three articles report new directions for antidepressant therapeutics. Papakostas et al. presented the results of a promising phase 2, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of NSI-189 phosphate, a novel neurogenic compound, in MDD patients [ 27 ]. As the endogenous opioid system is thought to play an important role in the regulation of mood, Fava et al. studied the buprenorphine/samidorphan combination as an investigational opioid system modulator for adjunctive treatment of MDD in two phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies that utilized the same sequential parallel-comparison design [ 28 ]. One of the studies achieved the primary endpoint, namely change from baseline in Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)-10 at week 5 versus placebo) and the other study did not achieve the primary endpoint. However, the pooled analysis of the two studies demonstrated consistently greater reduction in the MADRS-10 scores from baseline versus placebo at multiple timepoints, including end of treatment. These data provide cautious optimism and support further controlled trials for this potential new treatment option for patients with MDD who have an inadequate response to currently available antidepressants. Fava et al. also report the results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trial of intravenous (IV) ketamine as adjunctive therapy in treatment-resistant depression, using four doses of ketamine and a control [ 29 , 30 ]. They show that there was evidence for the efficacy of the two higher doses of IV ketamine and no clear or consistent evidence for clinically meaningful efficacy of the two lower doses studied.

Overall, in this issue, immense progress in depression research is provided by outstanding studies that highlight advances in our understanding of MDD biology, clinical features, co-morbidity, genetics, brain imaging (including imaging biomarkers), and treatment. Building on the groundbreaking articles from our previous 2020 special issues on stress and behavior [ 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 ] and on depression [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 ], we are proud that the stunning progress presented here found its home in our pages. From inception in 1996, we have aimed at making Molecular Psychiatry promote the integration of molecular medicine and clinical psychiatry [ 63 ]. It is particularly rewarding to see that goal achieved so spectacularly in this second 2020 special issue on MDD, a disorder of gene-environment interactions that represents a pressing public health challenge, with an ever increasing impact on society [ 64 , 65 , 66 ]. We are privileged to have in these two 2020 depression special issues four remarkable papers from Paul Greengard’s teams that provide substantial new data on the mechanisms of antidepressant action [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. Such profound advances in basic science are needed to facilitate and guide future translational efforts needed to advance therapeutics [ 67 , 68 ].

Chottekalapanda R, et al. AP-1 controls the p11-dependent antidepressant response. Mol Psychiatry. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-020-0767-8 .

Sagi Y, et al. Emergence of 5-HT5A signaling in parvalbumin neurons mediates delayed antidepressant action. Mol Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0379-3 .

Oh SJ, et al. Hippocampal mossy cell involvement in behavioral and neurogenic responses to chronic antidepressant treatment. Mol Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0384-6 .

Shuto T, et al. Obligatory roles of dopamine D1 receptors in the dentate gyrus in antidepressant actions of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, fluoxetine. Mol Psychiatry. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0316-x .

Schouten M, et al. Circadian glucocorticoid oscillations preserve a population of adult hippocampal neural stem cells in the aging brain. Mol Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0440-2 .

Kling MA, et al. Effects of electroconvulsive therapy on the CRH-ACTH-cortisol system in melancholic depression: preliminary findings. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1994;30:489–94.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Sternberg EM, Licinio J. Overview of neuroimmune stress interactions. Implications for susceptibility to inflammatory disease. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1995;771:364–71.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Bornstein SR, et al. Stress-inducible-stem cells: a new view on endocrine, metabolic and mental disease? Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24:2–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0244-9 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Rubin de Celis MF, et al. The effects of stress on brain and adrenal stem cells. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:590–3. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2015.230 .

Soares-Cunha C, et al. Nucleus accumbens medium spiny neurons subtypes signal both reward and aversion. Mol Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0484-3 .

Pecina M, et al. Endogenous opioid system dysregulation in depression: implications for new therapeutic approaches. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24:576–87, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0117-2 .

Halikere A, et al. Addiction associated N40D mu-opioid receptor variant modulates synaptic function in human neurons. Mol Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0507-0 .

Amare AT, et al. Bivariate genome-wide association analyses of the broad depression phenotype combined with major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder or schizophrenia reveal eight novel genetic loci for depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0336-6 .

Coleman JRI, et al. Genome-wide gene-environment analyses of major depressive disorder and reported lifetime traumatic experiences in UK Biobank. Mol Psychiatry. 2020 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0546-6 .

Belvederi Murri M, Amore M, Respino M, Alexopoulos GS. The symptom network structure of depressive symptoms in late-life: results from a European population study. Mol Psychiatry. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0232-0 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Simmons WK, et al. Appetite changes reveal depression subgroups with distinct endocrine, metabolic, and immune states. Mol Psychiatry. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0093-6 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Mulugeta A, Zhou A, King C, Hypponen E. Association between major depressive disorder and multiple disease outcomes: a phenome-wide Mendelian randomisation study in the UK Biobank. Mol Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0486-1 .

Khandaker GM, et al. Shared mechanisms between coronary heart disease and depression: findings from a large UK general population-based cohort. Mol Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0395-3 .

Wang YH, et al. Depression and anxiety in relation to cancer incidence and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0595-x .

Cooper CM, et al. Discovery and replication of cerebral blood flow differences in major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0464-7 .

van Velzen LS, et al. White matter disturbances in major depressive disorder: a coordinated analysis across 20 international cohorts in the ENIGMA MDD working group. Mol Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0477-2 .

Greenberg T, et al. Reward related ventral striatal activity and differential response to sertraline versus placebo in depressed individuals. Mol Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0490-5 .

Korgaonkar MS, Goldstein-Piekarski AN, Fornito A & Williams, LM Intrinsic connectomes are a predictive biomarker of remission in major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0574-2 .

Repple J, et al. Severity of current depression and remission status are associated with structural connectome alterations in major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0603-1 .

Nuninga JO, et al. Volume increase in the dentate gyrus after electroconvulsive therapy in depressed patients as measured with 7T. Mol Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0392-6 .

Koch SBJ, Morey RA & Roelofs K. The role of the dentate gyrus in stress-related disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0572-4 .

Papakostas GI, et al. A phase 2, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of NSI-189 phosphate, a neurogenic compound, among outpatients with major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0334-8 .

Fava M, et al . Opioid system modulation with buprenorphine/samidorphan combination for major depressive disorder: two randomized controlled studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0284-1 .

Fava M, et al. Correction: double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trial of intravenous ketamine as adjunctive therapy in treatment-resistant depression (TRD). Mol Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0311-2 .

Fava M, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trial of intravenous ketamine as adjunctive therapy in treatment-resistant depression (TRD). Mol Psychiatry. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0256-5 (2018).

Licinio J. Advances in research on stress and behavior: special issue, 2020. Mol Psychiatry 2020;25:916–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-020-0741-5 .

Martinez ME, et al. Thyroid hormone overexposure decreases DNA methylation in germ cells of newborn male mice. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:915 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-020-0732-6 .

Martinez ME, et al. Thyroid hormone influences brain gene expression programs and behaviors in later generations by altering germ line epigenetic information. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:939–50. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0281-4 .

Le-Niculescu H, et al. Towards precision medicine for stress disorders: diagnostic biomarkers and targeted drugs. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:918–38. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0370-z .

Torres-Berrio A, et al. MiR-218: a molecular switch and potential biomarker of susceptibility to stress. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:951–64. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0421-5

Sillivan SE, et al. Correction: MicroRNA regulation of persistent stress-enhanced memory. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:1154 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0452-y .

Sillivan SE, et al. MicroRNA regulation of persistent stress-enhanced memory. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:965–76. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0432-2 .

Shi MM, et al. Hippocampal micro-opioid receptors on GABAergic neurons mediate stress-induced impairment of memory retrieval. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:977–92. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0435-z .

Mayo LM, et al. Protective effects of elevated anandamide on stress and fear-related behaviors: translational evidence from humans and mice. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:993–1005. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0215-1 .

Qu N, et al. A POMC-originated circuit regulates stress-induced hypophagia, depression, and anhedonia. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:1006–21. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0506-1 .

Fox ME, et al. Dendritic remodeling of D1 neurons by RhoA/Rho-kinase mediates depression-like behavior. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:1022–34. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0211-5 .

Jin J, et al. Ahnak scaffolds p11/Anxa2 complex and L-type voltage-gated calcium channel and modulates depressive behavior. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:1035–49. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0371-y .

Ben-Yehuda H, et al. Maternal Type-I interferon signaling adversely affects the microglia and the behavior of the offspring accompanied by increased sensitivity to stress. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:1050–67. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0604-0 .

Pearson-Leary J, et al. The gut microbiome regulates the increases in depressive-type behaviors and in inflammatory processes in the ventral hippocampus of stress vulnerable rats. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:1068–79. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0380-x .

Walker WH 2nd, et al. Acute exposure to low-level light at night is sufficient to induce neurological changes and depressive-like behavior. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:1080–93. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0430-4 .

Lei Y, et al. SIRT1 in forebrain excitatory neurons produces sexually dimorphic effects on depression-related behaviors and modulates neuronal excitability and synaptic transmission in the medial prefrontal cortex. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:1094–111. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0352-1 .

Sargin D, et al. Mapping the physiological and molecular markers of stress and SSRI antidepressant treatment in S100a10 corticostriatal neurons. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:1112–29. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0473-6 .

Article Google Scholar

Iob E, Kirschbaum C, Steptoe A. Persistent depressive symptoms, HPA-axis hyperactivity, and inflammation: the role of cognitive-affective and somatic symptoms. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:1130–40. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0501-6 .

Cabeza de Baca T, et al. Chronic psychosocial and financial burden accelerates 5-year telomere shortening: findings from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:1141–53. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0482-5 .

Licinio J & Wong ML. Advances in depression research: special issue, 2020, with three research articles by Paul Greengard. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:1156–58. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-020-0781-x .

Teissier A, et al. Early-life stress impairs postnatal oligodendrogenesis and adult emotional behaviour through activity-dependent mechanisms. Mol Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0493-2 .

Zhang Y, et al. CircDYM ameliorates depressive-like behavior by targeting miR-9 to regulate microglial activation via HSP90 ubiquitination. Mol Psychiatry. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0285-0 .

Tan A, et al. Effects of the KCNQ channel opener ezogabine on functional connectivity of the ventral striatum and clinical symptoms in patients with major depressive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0283-2 .

Kin K, et al. Cell encapsulation enhances antidepressant effect of the mesenchymal stem cells and counteracts depressive-like behavior of treatment-resistant depressed rats. Mol Psychiatry. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0208-0 .

Orrico-Sanchez A, et al. Antidepressant efficacy of a selective organic cation transporter blocker in a mouse model of depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0548-4 .

Han Y, et al. Systemic immunization with altered myelin basic protein peptide produces sustained antidepressant-like effects. Mol Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0470-9 .

Wittenberg GM, et al. Effects of immunomodulatory drugs on depressive symptoms: a mega-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials in inflammatory disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0471-8 .

Beydoun MA, et al. Systemic inflammation is associated with depressive symptoms differentially by sex and race: a longitudinal study of urban adults. Mol Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0408-2 .

Felger JC, et al. What does plasma CRP tell us about peripheral and central inflammation in depression? Mol Psychiatry. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0096-3 .

Clark SL, et al. A methylation study of long-term depression risk. Mol Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0516-z .

Aberg KA, et al. Methylome-wide association findings for major depressive disorder overlap in blood and brain and replicate in independent brain samples. Mol Psychiatry. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0247-6 .

Wei YB, et al. A functional variant in the serotonin receptor 7 gene (HTR7), rs7905446, is associated with good response to SSRIs in bipolar and unipolar depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-019-0397-1 .

Licinio J. Molecular Psychiatry: the integration of molecular medicine and clinical psychiatry. Mol Psychiatry. 1996;1:1–3.

Steenblock C, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and the neuroendocrine stress axis. Mol Psychiatry. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-020-0758-9 .

Wong ML, Dong C, Andreev V, Arcos-Burgos M, Licinio J. Prediction of susceptibility to major depression by a model of interactions of multiple functional genetic variants and environmental factors. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17:624–33. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2012.13 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Lee SH, Paz-Filho G, Mastronardi C, Licinio J, Wong ML. Is increased antidepressant exposure a contributory factor to the obesity pandemic? Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6:e759 https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2016.25 .

Bornstein SR, Licinio J. Improving the efficacy of translational medicine by optimally integrating health care, academia and industry. Nat Med. 2011;17:1567–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.2583 .

Licinio J, Wong ML. Launching the ‘war on mental illness’. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2013.180 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

State University of New York, Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY, 13210, USA

Julio Licinio & Ma-Li Wong

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Julio Licinio .

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Licinio, J., Wong, ML. Advances in depression research: second special issue, 2020, with highlights on biological mechanisms, clinical features, co-morbidity, genetics, imaging, and treatment. Mol Psychiatry 25 , 1356–1360 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-020-0798-1

Download citation

Published : 18 June 2020

Issue Date : July 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-020-0798-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Upregulation of carbonic anhydrase 1 beneficial for depressive disorder.

Acta Neuropathologica Communications (2023)

Introducing a depression-like syndrome for translational neuropsychiatry: a plea for taxonomical validity and improved comparability between humans and mice

- Iven-Alex von Mücke-Heim

- Lidia Urbina-Treviño

- Jan M. Deussing

Molecular Psychiatry (2023)

Reply to: “The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence” published by Moncrieff J, Cooper RE, Stockmann T, Amendola S, Hengartner MP, Horowitz MA in Molecular Psychiatry (2022 Jul 20. doi: 10.1038/s41380-022-01661-0)

- Lucie Bartova

- Rupert Lanzenberger

- Siegfried Kasper

Is the serotonin hypothesis/theory of depression still relevant? Methodological reflections motivated by a recently published umbrella review

- Hans-Jürgen Möller

- Peter Falkai

European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience (2023)

The heterogeneity of late-life depression and its pathobiology: a brain network dysfunction disorder

- Kurt A. Jellinger

Journal of Neural Transmission (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Logo Left Content

Logo Right Content

Stanford University School of Medicine blog

Imagining virtual reality as a simple tool to treat depression

Some of the 17 million Americans afflicted with major depressive disorder each year may soon receive a surprising new prescription from their clinician: Have fun on a virtual reality device.

Engaging in activities that make you feel good may seem like overly simplistic advice, especially when directed at people with severe depression. But the science behind this idea, called "behavioral activation," is well established. Multiple studies have found that encouraging people to get outside, exercise, socialize, volunteer or immerse themselves in enjoyable activities in a prescribed, systematic way can help ease the symptoms of depression.

- Virtual reality helps people with hoarding disorder practice decluttering

Now, Stanford researchers have discovered that engaging in these behaviors within a virtual reality system may show just as much efficacy in treating depression as carrying them out in the real world. And for those depressed to a level that makes leaving the house a challenge, it could provide the benefits of getting outside -- and even motivate them to get out.

"People who might otherwise have barriers to getting treatment might be open to using this technology in their own homes," said Kim Bullock, MD , a clinical professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences.

The study by Bullock's team, published in JMIR Mental Health , followed 26 people with major depressive disorder. Half were assigned traditional behavioral activation, and half used a virtual reality headset to participate in activities ranging from table tennis and mini-golf to touring foreign cities or attending shows. People in both groups saw their depression scores decrease by similar amounts.

"We've found that using virtual reality in an outpatient group of patients was both simple and efficacious in treating symptoms of depression," said Bullock, founder and director of Stanford's Neurobehavioral Clinic and Virtual Reality and Immersive Technologies (VRIT) program. "It can reduce the barriers to getting mental health treatment in a number of ways."

Bullock and her colleagues at the Stanford VRIT program have long studied the diverse ways to treat mental illnesses with virtual reality (VR) platforms, in which users donning headsets are immersed in simulated, three-dimensional environments.

Previous studies have examined how VR can be used to conduct therapy appointments, help people overcome anxieties and phobias, ease pain, learn social skills, and treat eating disorders and hoarding . But few research projects had focused on how to use the technology to treat anything as pervasive as major depressive disorder or other mood disorders

Depression impacts so many people right now, and we thought VR could have a large impact. Kim Bullock

"Depression impacts so many people right now, and we thought VR could have a large impact," said Bullock, who received support for the project from the Neuroscience:Translate Grant Program . "There can be significant barriers to behavioral activation in some patients -- they might be stuck in a hospital bed, or not have the means to access joyful activities or the motivation to leave their house. We started wondering whether simulated, pleasant activities might be a good first step for some people."

Bullock, along with clinical assistant professor Margot Paul, PsyD , first carried out a small feasibility study to see whether people with depression could use a VR headset with pre-loaded videos to engage in behavioral activation homework assigned by their therapist. After positive feedback from participants, the researchers conducted the randomized, controlled trial to test the efficacy of a more immersive and interactive VR approach.

The participants in the trial, all adults diagnosed with major depressive disorder who had not recently changed medications, met weekly with a clinical psychologist at Stanford who assigned them behavioral activation homework between sessions -- scheduling and committing to at least four pleasurable activities each week, either in virtual reality or real life.

Thirteen people in the study received a VR Meta Quest 2 headset as well as a list of potential activity ideas they could engage in using the headset, including games, travel videos, fitness classes, chat programs and education apps. The other 13 people were told to plan and partake in real life activities in a more typical fashion -- by going on outings in their community or socializing with friends.

After four weeks, both groups saw a significant decrease in their symptoms of depression and their depression rating on a widely used scale. Moreover, many people who had used the VR devices said the virtual activities had helped push them to get out of the house and be more involved in in-person activities.

"One of the most common pieces of feedback we got was that using the VR inspired people to get out and do things in the real world," Paul said. "These virtual activities got their motors running just enough to get out of bed."

- Stanford Medicine uses augmented reality for real-time data visualization during surgery

The only negative feedback pertained to learning how to set up the device, as well as the need for alerts or reminders to keep people accountable for engaging in the behavioral activation. Paul and Bullock have since developed a companion VR behavioral activation app that will help address some of these concerns.

The team says larger and longer-term studies are needed to find the best ways to administer virtual behavioral activation, as well as which patient populations might be best targeted with the VR treatment. They also think more efforts are needed to inform clinicians -- from therapists and psychologists to primary care doctors -- about how to prescribe VR behavioral activation appropriately.

These virtual activities got their motors running just enough to get out of bed. Margot Paul

But Paul, Bullock and their colleagues at Stanford VRIT believe the cost and ease of many VR platforms -- especially those that use mobile phones inserted into cheap cardboard headsets -- make it an easy treatment to scale up. They also believe the technology's relatability to a younger audience can only bring more openness to treating serious conditions like depression.

"As something that seems cool to young people, it serves not only to enhance but also de-stigmatize mental health treatments," Bullock said.

Illustration: Emily Moskal

More news about depression

- Serious talk about moods with bipolar disorder expert Po Wang

- Pilot study shows ketogenic diet improves severe mental illness

- Psychoactive drug ibogaine effectively treats traumatic brain injury in special ops military vets

- Human Neural Circuitry program seeks to investigate deepest mysteries of brain function, dysfunction

- Ketamine's effect on depression may hinge on hope

- Stanford Medicine-led research identifies a subtype of depression

- Researchers treat depression by reversing brain signals traveling the wrong way

- Stanford Medicine researchers find possible cause of depression after stroke

Popular posts

Are long COVID sufferers falling through the cracks?

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Biological, Psychological, and Social Determinants of Depression: A Review of Recent Literature

Olivia remes.

1 Institute for Manufacturing, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB3 0FS, UK

João Francisco Mendes

2 NOVA Medical School, Universidade NOVA de Lisboa, 1099-085 Lisbon, Portugal; ku.ca.mac@94cfj

Peter Templeton

3 IfM Engage Limited, Institute for Manufacturing, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB3 0FS, UK; ku.ca.mac@32twp

4 The William Templeton Foundation for Young People’s Mental Health (YPMH), Cambridge CB2 0AH, UK

Associated Data

Depression is one of the leading causes of disability, and, if left unmanaged, it can increase the risk for suicide. The evidence base on the determinants of depression is fragmented, which makes the interpretation of the results across studies difficult. The objective of this study is to conduct a thorough synthesis of the literature assessing the biological, psychological, and social determinants of depression in order to piece together the puzzle of the key factors that are related to this condition. Titles and abstracts published between 2017 and 2020 were identified in PubMed, as well as Medline, Scopus, and PsycInfo. Key words relating to biological, social, and psychological determinants as well as depression were applied to the databases, and the screening and data charting of the documents took place. We included 470 documents in this literature review. The findings showed that there are a plethora of risk and protective factors (relating to biological, psychological, and social determinants) that are related to depression; these determinants are interlinked and influence depression outcomes through a web of causation. In this paper, we describe and present the vast, fragmented, and complex literature related to this topic. This review may be used to guide practice, public health efforts, policy, and research related to mental health and, specifically, depression.

1. Introduction

Depression is one of the most common mental health issues, with an estimated prevalence of 5% among adults [ 1 , 2 ]. Symptoms may include anhedonia, feelings of worthlessness, concentration and sleep difficulties, and suicidal ideation. According to the World Health Organization, depression is a leading cause of disability; research shows that it is a burdensome condition with a negative impact on educational trajectories, work performance, and other areas of life [ 1 , 3 ]. Depression can start early in the lifecourse and, if it remains unmanaged, may increase the risk for substance abuse, chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, and premature mortality [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ].

Treatment for depression exists, such as pharmacotherapy, cognitive behavioural therapy, and other modalities. A meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials of patients shows that 56–60% of people respond well to active treatment with antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants) [ 9 ]. However, pharmacotherapy may be associated with problems, such as side-effects, relapse issues, a potential duration of weeks until the medication starts working, and possible limited efficacy in mild cases [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. Psychotherapy is also available, but access barriers can make it difficult for a number of people to get the necessary help.

Studies on depression have increased significantly over the past few decades. However, the literature remains fragmented and the interpretation of heterogeneous findings across studies and between fields is difficult. The cross-pollination of ideas between disciplines, such as genetics, neurology, immunology, and psychology, is limited. Reviews on the determinants of depression have been conducted, but they either focus exclusively on a particular set of determinants (ex. genetic risk factors [ 15 ]) or population sub-group (ex. children and adolescents [ 16 ]) or focus on characteristics measured predominantly at the individual level (ex. focus on social support, history of depression [ 17 ]) without taking the wider context (ex. area-level variables) into account. An integrated approach paying attention to key determinants from the biological, psychological, and social spheres, as well as key themes, such as the lifecourse perspective, enables clinicians and public health authorities to develop tailored, person-centred approaches.

The primary aim of this literature review: to address the aforementioned challenges, we have synthesized recent research on the biological, psychological, and social determinants of depression and we have reviewed research from fields including genetics, immunology, neurology, psychology, public health, and epidemiology, among others.

The subsidiary aim: we have paid special attention to important themes, including the lifecourse perspective and interactions between determinants, to guide further efforts by public health and medical professionals.

This literature review can be used as an evidence base by those in public health and the clinical setting and can be used to inform targeted interventions.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a review of the literature on the biological, psychological, and social determinants of depression in the last 4 years. We decided to focus on these determinants after discussions with academics (from the Manchester Metropolitan University, University of Cardiff, University of Colorado, Boulder, University of Cork, University of Leuven, University of Texas), charity representatives, and people with lived experience at workshops held by the University of Cambridge in 2020. In several aspects, we attempted to conduct this review according to PRISMA guidelines [ 18 ].

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are the following:

- - We included documents, such as primary studies, literature reviews, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, reports, and commentaries on the determinants of depression. The determinants refer to variables that appear to be linked to the development of depression, such as physiological factors (e.g., the nervous system, genetics), but also factors that are further away or more distal to the condition. Determinants may be risk or protective factors, and individual- or wider-area-level variables.

- - We focused on major depressive disorder, treatment-resistant depression, dysthymia, depressive symptoms, poststroke depression, perinatal depression, as well as depressive-like behaviour (common in animal studies), among others.

- - We included papers regardless of the measurement methods of depression.

- - We included papers that focused on human and/or rodent research.

- - This review focused on articles written in the English language.

- - Documents published between 2017–2020 were captured to provide an understanding of the latest research on this topic.

- - Studies that assessed depression as a comorbidity or secondary to another disorder.

- - Studies that did not focus on rodent and/or human research.

- - Studies that focused on the treatment of depression. We made this decision, because this is an in-depth topic that would warrant a separate stand-alone review.

- Next, we searched PubMed (2017–2020) using keywords related to depression and determinants. Appendix A contains the search strategy used. We also conducted focused searches in Medline, Scopus, and PsycInfo (2017–2020).

- Once the documents were identified through the databases, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to the titles and abstracts. Screening of documents was conducted by O.R., and a subsample was screened by J.M.; any discrepancies were resolved through a communication process.

- The full texts of documents were retrieved, and the inclusion and exclusion criteria were again applied. A subsample of documents underwent double screening by two authors (O.R., J.M.); again, any discrepancies were resolved through communication.

- a. A data charting form was created to capture the data elements of interest, including the authors, titles, determinants (biological, psychological, social), and the type of depression assessed by the research (e.g., major depression, depressive symptoms, depressive behaviour).

- b. The data charting form was piloted on a subset of documents, and refinements to it were made. The data charting form was created with the data elements described above and tested in 20 studies to determine whether refinements in the wording or language were needed.

- c. Data charting was conducted on the documents.

- d. Narrative analysis was conducted on the data charting table to identify key themes. When a particular finding was noted more than once, it was logged as a potential theme, with a review of these notes yielding key themes that appeared on multiple occasions. When key themes were identified, one researcher (O.R.) reviewed each document pertaining to that theme and derived concepts (key determinants and related outcomes). This process (a subsample) was verified by a second author (J.M.), and the two authors resolved any discrepancies through communication. Key themes were also checked as to whether they were of major significance to public mental health and at the forefront of public health discourse according to consultations we held with stakeholders from the Manchester Metropolitan University, University of Cardiff, University of Colorado, Boulder, University of Cork, University of Leuven, University of Texas, charity representatives, and people with lived experience at workshops held by the University of Cambridge in 2020.

We condensed the extensive information gleaned through our review into short summaries (with key points boxes for ease of understanding and interpretation of the data).

Through the searches, 6335 documents, such as primary studies, literature reviews, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, reports, and commentaries, were identified. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 470 papers were included in this review ( Supplementary Table S1 ). We focused on aspects related to biological, psychological, and social determinants of depression (examples of determinants and related outcomes are provided under each of the following sections.

3.1. Biological Factors

The following aspects will be discussed in this section: physical health conditions; then specific biological factors, including genetics; the microbiome; inflammatory factors; stress and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis dysfunction, and the kynurenine pathway. Finally, aspects related to cognition will also be discussed in the context of depression.

3.1.1. Physical Health Conditions

Studies on physical health conditions—key points:

- The presence of a physical health condition can increase the risk for depression

- Psychological evaluation in physically sick populations is needed

- There is large heterogeneity in study design and measurement; this makes the comparison of findings between and across studies difficult

A number of studies examined the links between the outcome of depression and physical health-related factors, such as bladder outlet obstruction, cerebral atrophy, cataract, stroke, epilepsy, body mass index and obesity, diabetes, urinary tract infection, forms of cancer, inflammatory bowel disorder, glaucoma, acne, urea accumulation, cerebral small vessel disease, traumatic brain injury, and disability in multiple sclerosis [ 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 ]. For example, bladder outlet obstruction has been linked to inflammation and depressive behaviour in rodent research [ 24 ]. The presence of head and neck cancer also seemed to be related to an increased risk for depressive disorder [ 45 ]. Gestational diabetes mellitus has been linked to depressive symptoms in the postpartum period (but no association has been found with depression in the third pregnancy trimester) [ 50 ], and a plethora of other such examples of relationships between depression and physical conditions exist. As such, the assessment of psychopathology and the provision of support are necessary in individuals of ill health [ 45 ]. Despite the large evidence base on physical health-related factors, differences in study methodology and design, the lack of standardization when it comes to the measurement of various physical health conditions and depression, and heterogeneity in the study populations makes it difficult to compare studies [ 50 ].

The next subsections discuss specific biological factors, including genetics; the microbiome; inflammatory factors; stress and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis dysfunction, and the kynurenine pathway; and aspects related to cognition.

3.1.2. Genetics

Studies on genetics—key points:

There were associations between genetic factors and depression; for example:

- The brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) plays an important role in depression

- Links exist between major histocompatibility complex region genes, as well as various gene polymorphisms and depression

- Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of genes involved in the tryptophan catabolites pathway are of interest in relation to depression

A number of genetic-related factors, genomic regions, polymorphisms, and other related aspects have been examined with respect to depression [ 61 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 97 , 98 , 99 , 100 , 101 , 102 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 106 , 107 , 108 , 109 , 110 , 111 , 112 , 113 , 114 , 115 , 116 , 117 , 118 , 119 , 120 , 121 , 122 , 123 , 124 , 125 , 126 , 127 , 128 , 129 , 130 , 131 , 132 , 133 , 134 , 135 , 136 , 137 , 138 , 139 , 140 ]. The influence of BDNF in relation to depression has been amply studied [ 117 , 118 , 141 , 142 , 143 ]. Research has shown associations between depression and BDNF (as well as candidate SNPs of the BDNF gene, polymorphisms of the BDNF gene, and the interaction of these polymorphisms with other determinants, such as stress) [ 129 , 144 , 145 ]. Specific findings have been reported: for example, a study reported a link between the BDNF rs6265 allele (A) and major depressive disorder [ 117 ].

Other research focused on major histocompatibility complex region genes, endocannabinoid receptor gene polymorphisms, as well as tissue-specific genes and gene co-expression networks and their links to depression [ 99 , 110 , 112 ]. The SNPs of genes involved in the tryptophan catabolites pathway have also been of interest when studying the pathogenesis of depression.

The results from genetics studies are compelling; however, the findings remain mixed. One study indicated no support for depression candidate gene findings [ 122 ]. Another study found no association between specific polymorphisms and major depressive disorder [ 132 ]. As such, further research using larger samples is needed to corroborate the statistically significant associations reported in the literature.

3.1.3. Microbiome

Studies on the microbiome—key points:

- The gut bacteria and the brain communicate via both direct and indirect pathways called the gut-microbiota-brain axis (the bidirectional communication networks between the central nervous system and the gastrointestinal tract; this axis plays an important role in maintaining homeostasis).

- A disordered microbiome can lead to inflammation, which can then lead to depression

- There are possible links between the gut microbiome, host liver metabolism, brain inflammation, and depression

The common themes of this review have focused on the microbiome/microbiota or gut metabolome [ 146 , 147 , 148 , 149 , 150 , 151 , 152 , 153 , 154 , 155 , 156 , 157 , 158 , 159 , 160 , 161 ], the microbiota-gut-brain axis, and related factors [ 152 , 162 , 163 , 164 , 165 , 166 , 167 ]. When there is an imbalance in the intestinal bacteria, this can interfere with emotional regulation and contribute to harmful inflammatory processes and mood disorders [ 148 , 151 , 153 , 155 , 157 ]. Rodent research has shown that there may be a bidirectional association between the gut microbiota and depression: a disordered gut microbiota can play a role in the onset of this mental health problem, but, at the same time, the existence of stress and depression may also lead to a lower level of richness and diversity in the microbiome [ 158 ].

Research has also attempted to disentangle the links between the gut microbiome, host liver metabolism, brain inflammation, and depression, as well as the role of the ratio of lactobacillus to clostridium [ 152 ]. The literature has also examined the links between medication, such as antibiotics, and mood and behaviour, with the findings showing that antibiotics may be related to depression [ 159 , 168 ]. The links between the microbiome and depression are complex, and further studies are needed to determine the underpinning causal mechanisms.

3.1.4. Inflammation

Studies on inflammation—key points:

- Pro-inflammatory cytokines are linked to depression

- Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as the tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, may play an important role

- Different methods of measurement are used, making the comparison of findings across studies difficult

Inflammation has been a theme in this literature review [ 60 , 161 , 164 , 169 , 170 , 171 , 172 , 173 , 174 , 175 , 176 , 177 , 178 , 179 , 180 , 181 , 182 , 183 , 184 ]. The findings show that raised levels of inflammation (because of factors such as pro-inflammatory cytokines) have been associated with depression [ 60 , 161 , 174 , 175 , 178 ]. For example, pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, have been linked to depression [ 185 ]. Various determinants, such as early life stress, have also been linked to systemic inflammation, and this can increase the risk for depression [ 186 ].

Nevertheless, not everyone with elevated inflammation develops depression; therefore, this is just one route out of many linked to pathogenesis. Despite the compelling evidence reported with respect to inflammation, it is difficult to compare the findings across studies because of different methods used to assess depression and its risk factors.

3.1.5. Stress and HPA Axis Dysfunction

Studies on stress and HPA axis dysfunction—key points:

- Stress is linked to the release of proinflammatory factors

- The dysregulation of the HPA axis is linked to depression

- Determinants are interlinked in a complex web of causation

Stress was studied in various forms in rodent populations and humans [ 144 , 145 , 155 , 174 , 176 , 180 , 185 , 186 , 187 , 188 , 189 , 190 , 191 , 192 , 193 , 194 , 195 , 196 , 197 , 198 , 199 , 200 , 201 , 202 , 203 , 204 , 205 , 206 , 207 , 208 , 209 , 210 , 211 ].

Although this section has some overlap with others (as is to be expected because all of these determinants and body systems are interlinked), a number of studies have focused on the impact of stress on mental health. Stress has been mentioned in the literature as a risk factor of poor mental health and has emerged as an important determinant of depression. The effects of this variable are wide-ranging, and a short discussion is warranted.

Stress has been linked to the release of inflammatory factors, as well as the development of depression [ 204 ]. When the stress is high or lasts for a long period of time, this may negatively impact the brain. Chronic stress can impact the dendrites and synapses of various neurons, and may be implicated in the pathway leading to major depressive disorder [ 114 ]. As a review by Uchida et al. indicates, stress may be associated with the “dysregulation of neuronal and synaptic plasticity” [ 114 ]. Even in rodent studies, stress has a negative impact: chronic and unpredictable stress (and other forms of tension or stress) have been linked to unusual behaviour and depression symptoms [ 114 ].

The depression process and related brain changes, however, have also been linked to the hyperactivity or dysregulation of the HPA axis [ 127 , 130 , 131 , 182 , 212 ]. One review indicates that a potential underpinning mechanism of depression relates to “HPA axis abnormalities involved in chronic stress” [ 213 ]. There is a complex relationship between the HPA axis, glucocorticoid receptors, epigenetic mechanisms, and psychiatric sequelae [ 130 , 212 ].

In terms of the relationship between the HPA axis and stress and their influence on depression, the diathesis–stress model offers an explanation: it could be that early stress plays a role in the hyperactivation of the HPA axis, thus creating a predisposition “towards a maladaptive reaction to stress”. When this predisposition then meets an acute stressor, depression may ensue; thus, in line with the diathesis–stress model, a pre-existing vulnerability and stressor can create fertile ground for a mood disorder [ 213 ]. An integrated review by Dean and Keshavan [ 213 ] suggests that HPA axis hyperactivity is, in turn, related to other determinants, such as early deprivation and insecure early attachment; this again shows the complex web of causation between the different determinants.

3.1.6. Kynurenine Pathway

Studies on the kynurenine pathway—key points:

- The kynurenine pathway is linked to depression

- Indolamine 2,3-dioxegenase (IDO) polymorphisms are linked to postpartum depression

The kynurenine pathway was another theme that emerged in this review [ 120 , 178 , 181 , 184 , 214 , 215 , 216 , 217 , 218 , 219 , 220 , 221 ]. The kynurenine pathway has been implicated not only in general depressed mood (inflammation-induced depression) [ 184 , 214 , 219 ] but also postpartum depression [ 120 ]. When the kynurenine metabolism pathway is activated, this results in metabolites, which are neurotoxic.

A review by Jeon et al. notes a link between the impairment of the kynurenine pathway and inflammation-induced depression (triggered by treatment for various physical diseases, such as malignancy). The authors note that this could represent an important opportunity for immunopharmacology [ 214 ]. Another review by Danzer et al. suggests links between the inflammation-induced activation of indolamine 2,3-dioxegenase (the enzyme that converts tryptophan to kynurenine), the kynurenine metabolism pathway, and depression, and also remarks about the “opportunities for treatment of inflammation-induced depression” [ 184 ].

3.1.7. Cognition

Studies on cognition and the brain—key points:

- Cognitive decline and cognitive deficits are linked to increased depression risk

- Cognitive reserve is important in the disability/depression relationship

- Family history of cognitive impairment is linked to depression

A number of studies have focused on the theme of cognition and the brain. The results show that factors, such as low cognitive ability/function, cognitive vulnerability, cognitive impairment or deficits, subjective cognitive decline, regression of dendritic branching and hippocampal atrophy/death of hippocampal cells, impaired neuroplasticity, and neurogenesis-related aspects, have been linked to depression [ 131 , 212 , 222 , 223 , 224 , 225 , 226 , 227 , 228 , 229 , 230 , 231 , 232 , 233 , 234 , 235 , 236 , 237 , 238 , 239 ]. The cognitive reserve appears to act as a moderator and can magnify the impact of certain determinants on poor mental health. For example, in a study in which participants with multiple sclerosis also had low cognitive reserve, disability was shown to increase the risk for depression [ 63 ]. Cognitive deficits can be both causal and resultant in depression. A study on individuals attending outpatient stroke clinics showed that lower scores in cognition were related to depression; thus, cognitive impairment appears to be associated with depressive symptomatology [ 226 ]. Further, Halahakoon et al. [ 222 ] note a meta-analysis [ 240 ] that shows that a family history of cognitive impairment (in first degree relatives) is also linked to depression.

In addition to cognitive deficits, low-level cognitive ability [ 231 ] and cognitive vulnerability [ 232 ] have also been linked to depression. While cognitive impairment may be implicated in the pathogenesis of depressive symptoms [ 222 ], negative information processing biases are also important; according to the ‘cognitive neuropsychological’ model of depression, negative affective biases play a central part in the development of depression [ 222 , 241 ]. Nevertheless, the evidence on this topic is mixed and further work is needed to determine the underpinning mechanisms between these states.

3.2. Psychological Factors

Studies on psychological factors—key points:

- There are many affective risk factors linked to depression

- Determinants of depression include negative self-concept, sensitivity to rejection, neuroticism, rumination, negative emotionality, and others

A number of studies have been undertaken on the psychological factors linked to depression (including mastery, self-esteem, optimism, negative self-image, current or past mental health conditions, and various other aspects, including neuroticism, brooding, conflict, negative thinking, insight, cognitive fusion, emotional clarity, rumination, dysfunctional attitudes, interpretation bias, and attachment style) [ 66 , 128 , 140 , 205 , 210 , 228 , 235 , 242 , 243 , 244 , 245 , 246 , 247 , 248 , 249 , 250 , 251 , 252 , 253 , 254 , 255 , 256 , 257 , 258 , 259 , 260 , 261 , 262 , 263 , 264 , 265 , 266 , 267 , 268 , 269 , 270 , 271 , 272 , 273 , 274 , 275 , 276 , 277 , 278 , 279 , 280 , 281 , 282 , 283 , 284 , 285 , 286 , 287 , 288 , 289 , 290 ]. Determinants related to this condition include low self-esteem and shame, among other factors [ 269 , 270 , 275 , 278 ]. Several emotional states and traits, such as neuroticism [ 235 , 260 , 271 , 278 ], negative self-concept (with self-perceptions of worthlessness and uselessness), and negative interpretation or attention biases have been linked to depression [ 261 , 271 , 282 , 283 , 286 ]. Moreover, low emotional clarity has been associated with depression [ 267 ]. When it comes to the severity of the disorder, it appears that meta-emotions (“emotions that occur in response to other emotions (e.g., guilt about anger)” [ 268 ]) have a role to play in depression [ 268 ].

A determinant that has received much attention in mental health research concerns rumination. Rumination has been presented as a mediator but also as a risk factor for depression [ 57 , 210 , 259 ]. When studied as a risk factor, it appears that the relationship of rumination with depression is mediated by variables that include limited problem-solving ability and insufficient social support [ 259 ]. However, rumination also appears to act as a mediator: for example, this variable (particularly brooding rumination) lies on the causal pathway between poor attention control and depression [ 265 ]. This shows that determinants may present in several forms: as moderators or mediators, risk factors or outcomes, and this is why disentangling the relationships between the various factors linked to depression is a complex task.

The psychological determinants are commonly researched variables in the mental health literature. A wide range of factors have been linked to depression, such as the aforementioned determinants, but also: (low) optimism levels, maladaptive coping (such as avoidance), body image issues, and maladaptive perfectionism, among others [ 269 , 270 , 272 , 273 , 275 , 276 , 279 , 285 , 286 ]. Various mechanisms have been proposed to explain the way these determinants increase the risk for depression. One of the underpinning mechanisms linking the determinants and depression concerns coping. For example, positive fantasy engagement, cognitive biases, or personality dispositions may lead to emotion-focused coping, such as brooding, and subsequently increase the risk for depression [ 272 , 284 , 287 ]. Knowing the causal mechanisms linking the determinants to outcomes provides insight for the development of targeted interventions.

3.3. Social Determinants

Studies on social determinants—key points:

- Social determinants are the conditions in the environments where people are born, live, learn, work, play, etc.; these influence (mental) health [ 291 ]

- There are many social determinants linked to depression, such as sociodemographics, social support, adverse childhood experiences

- Determinants can be at the individual, social network, community, and societal levels

Studies also focused on the social determinants of (mental) health; these are the conditions in which people are born, live, learn, work, play, and age, and have a significant influence on wellbeing [ 291 ]. Factors such as age, social or socioeconomic status, social support, financial strain and deprivation, food insecurity, education, employment status, living arrangements, marital status, race, childhood conflict and bullying, violent crime exposure, abuse, discrimination, (self)-stigma, ethnicity and migrant status, working conditions, adverse or significant life events, illiteracy or health literacy, environmental events, job strain, and the built environment have been linked to depression, among others [ 52 , 133 , 235 , 236 , 239 , 252 , 269 , 280 , 292 , 293 , 294 , 295 , 296 , 297 , 298 , 299 , 300 , 301 , 302 , 303 , 304 , 305 , 306 , 307 , 308 , 309 , 310 , 311 , 312 , 313 , 314 , 315 , 316 , 317 , 318 , 319 , 320 , 321 , 322 , 323 , 324 , 325 , 326 , 327 , 328 , 329 , 330 , 331 , 332 , 333 , 334 , 335 , 336 , 337 , 338 , 339 , 340 , 341 , 342 , 343 , 344 , 345 , 346 , 347 , 348 , 349 , 350 , 351 , 352 , 353 , 354 , 355 , 356 , 357 , 358 , 359 , 360 , 361 , 362 , 363 , 364 , 365 , 366 , 367 , 368 , 369 , 370 , 371 ]. Social support and cohesion, as well as structural social capital, have also been identified as determinants [ 140 , 228 , 239 , 269 , 293 , 372 , 373 , 374 , 375 , 376 , 377 , 378 , 379 ]. In a study, part of the findings showed that low levels of education have been shown to be linked to post-stroke depression (but not severe or clinical depression outcomes) [ 299 ]. A study within a systematic review indicated that having only primary education was associated with a higher risk of depression compared to having secondary or higher education (although another study contrasted this finding) [ 296 ]. Various studies on socioeconomic status-related factors have been undertaken [ 239 , 297 ]; the research has shown that a low level of education is linked to depression [ 297 ]. Low income is also related to depressive disorders [ 312 ]. By contrast, high levels of education and income are protective [ 335 ].