What is comparative analysis? A complete guide

Last updated

18 April 2023

Reviewed by

Jean Kaluza

Comparative analysis is a valuable tool for acquiring deep insights into your organization’s processes, products, and services so you can continuously improve them.

Similarly, if you want to streamline, price appropriately, and ultimately be a market leader, you’ll likely need to draw on comparative analyses quite often.

When faced with multiple options or solutions to a given problem, a thorough comparative analysis can help you compare and contrast your options and make a clear, informed decision.

If you want to get up to speed on conducting a comparative analysis or need a refresher, here’s your guide.

Make comparative analysis less tedious

Dovetail streamlines comparative analysis to help you uncover and share actionable insights

- What exactly is comparative analysis?

A comparative analysis is a side-by-side comparison that systematically compares two or more things to pinpoint their similarities and differences. The focus of the investigation might be conceptual—a particular problem, idea, or theory—or perhaps something more tangible, like two different data sets.

For instance, you could use comparative analysis to investigate how your product features measure up to the competition.

After a successful comparative analysis, you should be able to identify strengths and weaknesses and clearly understand which product is more effective.

You could also use comparative analysis to examine different methods of producing that product and determine which way is most efficient and profitable.

The potential applications for using comparative analysis in everyday business are almost unlimited. That said, a comparative analysis is most commonly used to examine

Emerging trends and opportunities (new technologies, marketing)

Competitor strategies

Financial health

Effects of trends on a target audience

- Why is comparative analysis so important?

Comparative analysis can help narrow your focus so your business pursues the most meaningful opportunities rather than attempting dozens of improvements simultaneously.

A comparative approach also helps frame up data to illuminate interrelationships. For example, comparative research might reveal nuanced relationships or critical contexts behind specific processes or dependencies that wouldn’t be well-understood without the research.

For instance, if your business compares the cost of producing several existing products relative to which ones have historically sold well, that should provide helpful information once you’re ready to look at developing new products or features.

- Comparative vs. competitive analysis—what’s the difference?

Comparative analysis is generally divided into three subtypes, using quantitative or qualitative data and then extending the findings to a larger group. These include

Pattern analysis —identifying patterns or recurrences of trends and behavior across large data sets.

Data filtering —analyzing large data sets to extract an underlying subset of information. It may involve rearranging, excluding, and apportioning comparative data to fit different criteria.

Decision tree —flowcharting to visually map and assess potential outcomes, costs, and consequences.

In contrast, competitive analysis is a type of comparative analysis in which you deeply research one or more of your industry competitors. In this case, you’re using qualitative research to explore what the competition is up to across one or more dimensions.

For example

Service delivery —metrics like the Net Promoter Scores indicate customer satisfaction levels.

Market position — the share of the market that the competition has captured.

Brand reputation —how well-known or recognized your competitors are within their target market.

- Tips for optimizing your comparative analysis

Conduct original research

Thorough, independent research is a significant asset when doing comparative analysis. It provides evidence to support your findings and may present a perspective or angle not considered previously.

Make analysis routine

To get the maximum benefit from comparative research, make it a regular practice, and establish a cadence you can realistically stick to. Some business areas you could plan to analyze regularly include:

Profitability

Competition

Experiment with controlled and uncontrolled variables

In addition to simply comparing and contrasting, explore how different variables might affect your outcomes.

For example, a controllable variable would be offering a seasonal feature like a shopping bot to assist in holiday shopping or raising or lowering the selling price of a product.

Uncontrollable variables include weather, changing regulations, the current political climate, or global pandemics.

Put equal effort into each point of comparison

Most people enter into comparative research with a particular idea or hypothesis already in mind to validate. For instance, you might try to prove the worthwhileness of launching a new service. So, you may be disappointed if your analysis results don’t support your plan.

However, in any comparative analysis, try to maintain an unbiased approach by spending equal time debating the merits and drawbacks of any decision. Ultimately, this will be a practical, more long-term sustainable approach for your business than focusing only on the evidence that favors pursuing your argument or strategy.

Writing a comparative analysis in five steps

To put together a coherent, insightful analysis that goes beyond a list of pros and cons or similarities and differences, try organizing the information into these five components:

1. Frame of reference

Here is where you provide context. First, what driving idea or problem is your research anchored in? Then, for added substance, cite existing research or insights from a subject matter expert, such as a thought leader in marketing, startup growth, or investment

2. Grounds for comparison Why have you chosen to examine the two things you’re analyzing instead of focusing on two entirely different things? What are you hoping to accomplish?

3. Thesis What argument or choice are you advocating for? What will be the before and after effects of going with either decision? What do you anticipate happening with and without this approach?

For example, “If we release an AI feature for our shopping cart, we will have an edge over the rest of the market before the holiday season.” The finished comparative analysis will weigh all the pros and cons of choosing to build the new expensive AI feature including variables like how “intelligent” it will be, what it “pushes” customers to use, how much it takes off the plates of customer service etc.

Ultimately, you will gauge whether building an AI feature is the right plan for your e-commerce shop.

4. Organize the scheme Typically, there are two ways to organize a comparative analysis report. First, you can discuss everything about comparison point “A” and then go into everything about aspect “B.” Or, you alternate back and forth between points “A” and “B,” sometimes referred to as point-by-point analysis.

Using the AI feature as an example again, you could cover all the pros and cons of building the AI feature, then discuss the benefits and drawbacks of building and maintaining the feature. Or you could compare and contrast each aspect of the AI feature, one at a time. For example, a side-by-side comparison of the AI feature to shopping without it, then proceeding to another point of differentiation.

5. Connect the dots Tie it all together in a way that either confirms or disproves your hypothesis.

For instance, “Building the AI bot would allow our customer service team to save 12% on returns in Q3 while offering optimizations and savings in future strategies. However, it would also increase the product development budget by 43% in both Q1 and Q2. Our budget for product development won’t increase again until series 3 of funding is reached, so despite its potential, we will hold off building the bot until funding is secured and more opportunities and benefits can be proved effective.”

Get started today

Go from raw data to valuable insights with a flexible research platform

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 21 December 2023

Last updated: 16 December 2023

Last updated: 6 October 2023

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 12 May 2023

Last updated: 15 February 2024

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 18 May 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 10 April 2023

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

Qualitative Vs. Quantitative Research — A step-wise guide to conduct research

A research study includes the collection and analysis of data. In quantitative research, the data are analyzed with numbers and statistics, and in qualitative research, the data analyzed are non-numerical and perceive the meaning of social reality.

What Is Qualitative Research?

Qualitative research observes and describes a phenomenon to gain a deeper understanding of a subject. It is also used to generate hypotheses for further studies. In general, qualitative research is explanatory and helps understands how an individual perceives non-numerical data, like video, photographs, or audio recordings. The qualitative data is collected from diary accounts or interviews and analyzed by grounded theory or thematic analysis.

When to Use Qualitative Research?

Qualitative research is used when the outcome of the research study is to disseminate knowledge and understand concepts, thoughts, and experiences. This type of research focuses on creating ideas and formulating theories or hypotheses .

Benefits of Qualitative Research

- Unlike quantitative research, which relies on numerical data, qualitative research relies on data collected from interviews, observations, and written texts.

- It is often used in fields such as sociology and anthropology, where the goal is to understand complex social phenomena.

- Qualitative research is considered to be more flexible and adaptive, as it is used to study a wide range of social aspects.

- Additionally, qualitative research often leads to deeper insights into the research study. This helps researchers and scholars in designing their research methods .

Qualitative Research Example

In research, to understand the culture of a pharma company, one could take an ethnographic approach. With an experience in the company, one could gather data based on the —

- Field notes with observations, and reflections on one’s experiences of the company’s culture

- Open-ended surveys for employees across all the company’s departments via email to find out variations in culture across teams and departments

- Interview sessions with employees and gather information about their experiences and perspectives.

What Is Quantitative Research?

Quantitative research is for testing hypotheses and measuring relationships between variables. It follows the process of objectively collecting data and analyzing it numerically, to determine and control variables of interest. This type of research aims to test causal relationships between variables and provide generalized results. These results determine if the theory proposed for the research study could be accepted or rejected.

When to Use Quantitative Research?

Quantitative research is used when a research study needs to confirm or test a theory or a hypothesis. When a research study is focused on measuring and quantifying data, using a quantitative approach is appropriate. It is often used in fields such as economics, marketing, or biology, where researchers are interested in studying trends and relationships between variables .

Benefits of Quantitative Research

- Quantitative data is interpreted with statistical analysis . The type of statistical study is based on the principles of mathematics and it provides a fast, focused, scientific and relatable approach.

- Quantitative research creates an ability to replicate the test and results of research. This approach makes the data more reliable and less open to argument.

- After collecting the quantitative data, expected results define which statistical tests are applicable and results provide a quantifiable conclusion for the research hypothesis

- Research with complex statistical analysis is considered valuable and impressive. Quantitative research is associated with technical advancements like computer modeling and data-based decisions.

Quantitative Research Example

An organization wishes to conduct a customer satisfaction (CSAT) survey by using a survey template. From the survey, the organization can acquire quantitative data and metrics on the brand or the organization based on the customer’s experience. Various parameters such as product quality, pricing, customer experience, etc. could be used to generate data in the form of numbers that is statistically analyzed.

Data Collection Methods

1. qualitative data collection methods.

Qualitative data is collected from interview sessions, discussions with focus groups, case studies, and ethnography (scientific description of people and cultures with their customs and habits). The collection methods involve understanding and interpreting social interactions.

Qualitative research data also includes respondents’ opinions and feelings, which is conducted face-to-face mostly in focus groups. Respondents are asked open-ended questions either verbally or through discussion among a group of people, related to the research topic implemented to collect opinions for further research.

2. Quantitative Data Collection Methods

Quantitative research data is acquired from surveys, experiments, observations, probability sampling, questionnaire observation, and content review. Surveys usually contain a list of questions with multiple-choice responses relevant to the research topic under study. With the availability of online survey tools, researchers can conduct a web-based survey for quantitative research.

Quantitative data is also assimilated from research experiments. While conducting experiments, researchers focus on exploring one or more independent variables and studying their effect on one or more dependent variables.

A Step-wise Guide to Conduct Qualitative and Quantitative Research

- Understand the difference between types of research — qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods-based research.

- Develop a research question or hypothesis. This research approach will define which type of research one could choose.

- Choose a method for data collection. Depending on the process of data collection, the type of research could be determined.

- Analyze and interpret the collected data. Based on the analyzed data, results are reported.

- If observed results are not equivalent to expected results, consider using an unbiased research approach or choose both qualitative and quantitative research methods for preferred results.

Qualitative Vs. Quantitative Research – A Comparison

With an awareness of qualitative vs. quantitative research and the different data collection methods , researchers could use one or both types of research approaches depending on their preferred results. Moreover, to implement unbiased research and acquire meaningful insights from the research study, it is advisable to consider both qualitative and quantitative research methods .

Through this article, you would have understood the comparison between qualitative and quantitative research. However, if you have any queries related to qualitative vs. quantitative research, do comment below or email us.

Well explained and easy to understand.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Reporting Research

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for data interpretation

In research, choosing the right approach to understand data is crucial for deriving meaningful insights.…

Demystifying the Role of Confounding Variables in Research

In the realm of scientific research, the pursuit of knowledge often involves complex investigations, meticulous…

Research Interviews: An effective and insightful way of data collection

Research interviews play a pivotal role in collecting data for various academic, scientific, and professional…

Planning Your Data Collection: Designing methods for effective research

Planning your research is very important to obtain desirable results. In research, the relevance of…

- Manuscripts & Grants

- Trending Now

Unraveling Research Population and Sample: Understanding their role in statistical inference

Research population and sample serve as the cornerstones of any scientific inquiry. They hold the…

6 Steps to Evaluate the Effectiveness of Statistical Hypothesis Testing

How to Use Creative Data Visualization Techniques for Easy Comprehension of…

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

This website may not work correctly because your browser is out of date. Please update your browser .

Qualitative comparative analysis

Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) is a means of analysing the causal contribution of different conditions (e.g. aspects of an intervention and the wider context) to an outcome of interest.

QCA starts with the documentation of the different configurations of conditions associated with each case of an observed outcome. These are then subject to a minimisation procedure that identifies the simplest set of conditions that can account for all the observed outcomes, as well as their absence.

The results are typically expressed in statements expressed in ordinary language or as Boolean algebra. For example:

- A combination of Condition A and condition B or a combination of condition C and condition D will lead to outcome E.

- In Boolean notation this is expressed more succinctly as A*B + C*D→E

QCA results are able to distinguish various complex forms of causation, including:

- Configurations of causal conditions, not just single causes. In the example above, there are two different causal configurations, each made up of two conditions.

- Equifinality, where there is more than one way in which an outcome can happen. In the above example, each additional configuration represents a different causal pathway

- Causal conditions which are necessary, sufficient, both or neither, plus more complex combinations (known as INUS causes – insufficient but necessary parts of a configuration that is unnecessary but sufficient), which tend to be more common in everyday life. In the example above, no one condition was sufficient or necessary. But each condition is an INUS type cause

- Asymmetric causes – where the causes of failure may not simply be the absence of the cause of success. In the example above, the configuration associated with the absence of E might have been one like this: A*B*X + C*D*X →e Here X condition was a sufficient and necessary blocking condition.

- The relative influence of different individual conditions and causal configurations in a set of cases being examined. In the example above, the first configuration may have been associated with 10 cases where the outcome was E, whereas the second might have been associated with only 5 cases. Configurations can be evaluated in terms of coverage (the percentage of cases they explain) and consistency (the extent to which a configuration is always associated with a given outcome).

QCA is able to use relatively small and simple data sets. There is no requirement to have enough cases to achieve statistical significance, although ideally there should be enough cases to potentially exhibit all the possible configurations. The latter depends on the number of conditions present. In a 2012 survey of QCA uses the median number of cases was 22 and the median number of conditions was 6. For each case, the presence or absence of a condition is recorded using nominal data i.e. a 1 or 0. More sophisticated forms of QCA allow the use of “fuzzy sets” i.e. where a condition may be partly present or partly absent, represented by a value of 0.8 or 0.2 for example. Or there may be more than one kind of presence, represented by values of 0, 1, 2 or more for example. Data for a QCA analysis is collated in a simple matrix form, where rows = cases and columns = conditions, with the rightmost column listing the associated outcome for each case, also described in binary form.

QCA is a theory-driven approach, in that the choice of conditions being examined needs to be driven by a prior theory about what matters. The list of conditions may also be revised in the light of the results of the QCA analysis if some configurations are still shown as being associated with a mixture of outcomes. The coding of the presence/absence of a condition also requires an explicit view of that condition and when and where it can be considered present. Dichotomisation of quantitative measures about the incidence of a condition also needs to be carried out with an explicit rationale, and not on an arbitrary basis.

Although QCA was originally developed by Charles Ragin some decades ago it is only in the last decade that its use has become more common amongst evaluators. Articles on its use have appeared in Evaluation and the American Journal of Evaluation.

For a worked example, see Charles Ragin’s What is Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA)? , slides 6 to 15 on The bare-bones basics of crisp-set QCA.

[A crude summary of the example is presented here]

In his presentation Ragin provides data on 65 countries and their reactions to austerity measures imposed by the IMF. This has been condensed into a Truth Table (shown below), which shows all possible configurations of four different conditions that were thought to affect countries’ responses: the presence or absence of severe austerity, prior mobilisation, corrupt government, rapid price rises. Next to each configuration is data on the outcome associated with that configuration – the numbers of countries experiencing mass protest or not. There are 16 configurations in all, one per row. The rightmost column describes the consistency of each configuration: whether all cases with that configuration have one type of outcome, or a mixed outcome (i.e. some protests and some no protests). Notice that there are also some configurations with no known cases.

Ragin’s next step is to improve the consistency of the configurations with mixed consistency. This is done either by rejecting cases within an inconsistent configuration because they are outliers (with exceptional circumstances unlikely to be repeated elsewhere) or by introducing an additional condition (column) that distinguishes between those configurations which did lead to protest and those which did not. In this example, a new condition was introduced that removed the inconsistency, which was described as “not having a repressive regime”.

The next step involves reducing the number of configurations needed to explain all the outcomes, known as minimisation. Because this is a time-consuming process, this is done by an automated algorithm (aka a computer program) This algorithm takes two configurations at a time and examines if they have the same outcome. If so, and if their configurations are only different in respect to one condition this is deemed to not be an important causal factor and the two configurations are collapsed into one. This process of comparisons is continued, looking at all configurations, including newly collapsed ones, until no further reductions are possible.

[Jumping a few more specific steps] The final result from the minimisation of the above truth table is this configuration:

SA*(PR + PM*GC*NR)

The expression indicates that IMF protest erupts when severe austerity (SA) is combined with either (1) rapid price increases (PR) or (2) the combination of prior mobilization (PM), government corruption (GC), and non-repressive regime (NR).

This slide show from Charles C Ragin, provides a detailed explanation, including examples, that clearly demonstrates the question, 'What is QCA?'

This book, by Schneider and Wagemann, provides a comprehensive overview of the basic principles of set theory to model causality and applications of Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA), the most developed form of set-theoretic method, for research ac

This article by Nicolas Legewie provides an introduction to Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA). It discusses the method's main principles and advantages, including its concepts.

COMPASSS (Comparative methods for systematic cross-case analysis) is a website that has been designed to develop the use of systematic comparative case analysis as a research strategy by bringing together scholars and practitioners who share its use as

This paper from Patrick A. Mello focuses on reviewing current applications for use in Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) in order to take stock of what is available and highlight best practice in this area.

Marshall, G. (1998). Qualitative comparative analysis. In A Dictionary of Sociology Retrieved from https://www.encyclopedia.com/social-sciences/dictionaries-thesauruses-pictures-and-press-releases/qualitative-comparative-analysis

Expand to view all resources related to 'Qualitative comparative analysis'

- An introduction to applied data analysis with qualitative comparative analysis

- Qualitative comparative analysis: A valuable approach to add to the evaluator’s ‘toolbox’? Lessons from recent applications

'Qualitative comparative analysis' is referenced in:

- 52 weeks of BetterEvaluation: Week 34 Generalisations from case studies?

- Week 18: is there a "right" approach to establishing causation in advocacy evaluation?

Framework/Guide

- Rainbow Framework : Check the results are consistent with causal contribution

- Data mining

Back to top

© 2022 BetterEvaluation. All right reserved.

- Open access

- Published: 07 May 2021

The use of Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) to address causality in complex systems: a systematic review of research on public health interventions

- Benjamin Hanckel 1 ,

- Mark Petticrew 2 ,

- James Thomas 3 &

- Judith Green 4

BMC Public Health volume 21 , Article number: 877 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

21k Accesses

42 Citations

34 Altmetric

Metrics details

Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) is a method for identifying the configurations of conditions that lead to specific outcomes. Given its potential for providing evidence of causality in complex systems, QCA is increasingly used in evaluative research to examine the uptake or impacts of public health interventions. We map this emerging field, assessing the strengths and weaknesses of QCA approaches identified in published studies, and identify implications for future research and reporting.

PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science were systematically searched for peer-reviewed studies published in English up to December 2019 that had used QCA methods to identify the conditions associated with the uptake and/or effectiveness of interventions for public health. Data relating to the interventions studied (settings/level of intervention/populations), methods (type of QCA, case level, source of data, other methods used) and reported strengths and weaknesses of QCA were extracted and synthesised narratively.

The search identified 1384 papers, of which 27 (describing 26 studies) met the inclusion criteria. Interventions evaluated ranged across: nutrition/obesity ( n = 8); physical activity ( n = 4); health inequalities ( n = 3); mental health ( n = 2); community engagement ( n = 3); chronic condition management ( n = 3); vaccine adoption or implementation ( n = 2); programme implementation ( n = 3); breastfeeding ( n = 2), and general population health ( n = 1). The majority of studies ( n = 24) were of interventions solely or predominantly in high income countries. Key strengths reported were that QCA provides a method for addressing causal complexity; and that it provides a systematic approach for understanding the mechanisms at work in implementation across contexts. Weaknesses reported related to data availability limitations, especially on ineffective interventions. The majority of papers demonstrated good knowledge of cases, and justification of case selection, but other criteria of methodological quality were less comprehensively met.

QCA is a promising approach for addressing the role of context in complex interventions, and for identifying causal configurations of conditions that predict implementation and/or outcomes when there is sufficiently detailed understanding of a series of comparable cases. As the use of QCA in evaluative health research increases, there may be a need to develop advice for public health researchers and journals on minimum criteria for quality and reporting.

Peer Review reports

Interest in the use of Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) arises in part from growing recognition of the need to broaden methodological capacity to address causality in complex systems [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. Guidance for researchers for evaluating complex interventions suggests process evaluations [ 4 , 5 ] can provide evidence on the mechanisms of change, and the ways in which context affects outcomes. However, this does not address the more fundamental problems with trial and quasi-experimental designs arising from system complexity [ 6 ]. As Byrne notes, the key characteristic of complex systems is ‘emergence’ [ 7 ]: that is, effects may accrue from combinations of components, in contingent ways, which cannot be reduced to any one level. Asking about ‘what works’ in complex systems is not to ask a simple question about whether an intervention has particular effects, but rather to ask: “how the intervention works in relation to all existing components of the system and to other systems and their sub-systems that intersect with the system of interest” [ 7 ]. Public health interventions are typically attempts to effect change in systems that are themselves dynamic; approaches to evaluation are needed that can deal with emergence [ 8 ]. In short, understanding the uptake and impact of interventions requires methods that can account for the complex interplay of intervention conditions and system contexts.

To build a useful evidence base for public health, evaluations thus need to assess not just whether a particular intervention (or component) causes specific change in one variable, in controlled circumstances, but whether those interventions shift systems, and how specific conditions of interventions and setting contexts interact to lead to anticipated outcomes. There have been a number of calls for the development of methods in intervention research to address these issues of complex causation [ 9 , 10 , 11 ], including calls for the greater use of case studies to provide evidence on the important elements of context [ 12 , 13 ]. One approach for addressing causality in complex systems is Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA): a systematic way of comparing the outcomes of different combinations of system components and elements of context (‘conditions’) across a series of cases.

The potential of qualitative comparative analysis

QCA is an approach developed by Charles Ragin [ 14 , 15 ], originating in comparative politics and macrosociology to address questions of comparative historical development. Using set theory, QCA methods explore the relationships between ‘conditions’ and ‘outcomes’ by identifying configurations of necessary and sufficient conditions for an outcome. The underlying logic is different from probabilistic reasoning, as the causal relationships identified are not inferred from the (statistical) likelihood of them being found by chance, but rather from comparing sets of conditions and their relationship to outcomes. It is thus more akin to the generative conceptualisations of causality in realist evaluation approaches [ 16 ]. QCA is a non-additive and non-linear method that emphasises diversity, acknowledging that different paths can lead to the same outcome. For evaluative research in complex systems [ 17 ], QCA therefore offers a number of benefits, including: that QCA can identify more than one causal pathway to an outcome (equifinality); that it accounts for conjectural causation (where the presence or absence of conditions in relation to other conditions might be key); and that it is asymmetric with respect to the success or failure of outcomes. That is, that specific factors explain success does not imply that their absence leads to failure (causal asymmetry).

QCA was designed, and is typically used, to compare data from a medium N (10–50) series of cases that include those with and those without the (dichotomised) outcome. Conditions can be dichotomised in ‘crisp sets’ (csQCA) or represented in ‘fuzzy sets’ (fsQCA), where set membership is calibrated (either continuously or with cut offs) between two extremes representing fully in (1) or fully out (0) of the set. A third version, multi-value QCA (mvQCA), infrequently used, represents conditions as ‘multi-value sets’, with multinomial membership [ 18 ]. In calibrating set membership, the researcher specifies the critical qualitative anchors that capture differences in kind (full membership and full non-membership), as well as differences in degree in fuzzy sets (partial membership) [ 15 , 19 ]. Data on outcomes and conditions can come from primary or secondary qualitative and/or quantitative sources. Once data are assembled and coded, truth tables are constructed which “list the logically possible combinations of causal conditions” [ 15 ], collating the number of cases where those configurations occur to see if they share the same outcome. Analysis of these truth tables assesses first whether any conditions are individually necessary or sufficient to predict the outcome, and then whether any configurations of conditions are necessary or sufficient. Necessary conditions are assessed by examining causal conditions shared by cases with the same outcome, whilst identifying sufficient conditions (or combinations of conditions) requires examining cases with the same causal conditions to identify if they have the same outcome [ 15 ]. However, as Legewie argues, the presence of a condition, or a combination of conditions in actual datasets, are likely to be “‘quasi-necessary’ or ‘quasi-sufficient’ in that the causal relation holds in a great majority of cases, but some cases deviate from this pattern” [ 20 ]. Following reduction of the complexity of the model, the final model is tested for coverage (the degree to which a configuration accounts for instances of an outcome in the empirical cases; the proportion of cases belonging to a particular configuration) and consistency (the degree to which the cases sharing a combination of conditions align with a proposed subset relation). The result is an analysis of complex causation, “defined as a situation in which an outcome may follow from several different combinations of causal conditions” [ 15 ] illuminating the ‘causal recipes’, the causally relevant conditions or configuration of conditions that produce the outcome of interest.

QCA, then, has promise for addressing questions of complex causation, and recent calls for the greater use of QCA methods have come from a range of fields related to public health, including health research [ 17 ], studies of social interventions [ 7 ], and policy evaluation [ 21 , 22 ]. In making arguments for the use of QCA across these fields, researchers have also indicated some of the considerations that must be taken into account to ensure robust and credible analyses. There is a need, for instance, to ensure that ‘contradictions’, where cases with the same configurations show different outcomes, are resolved and reported [ 15 , 23 , 24 ]. Additionally, researchers must consider the ratio of cases to conditions, and limit the number of conditions to cases to ensure the validity of models [ 25 ]. Marx and Dusa, examining crisp set QCA, have provided some guidance to the ‘ceiling’ number of conditions which can be included relative to the number of cases to increase the probability of models being valid (that is, with a low probability of being generated through random data) [ 26 ].

There is now a growing body of published research in public health and related fields drawing on QCA methods. This is therefore a timely point to map the field and assess the potential of QCA as a method for contributing to the evidence base for what works in improving public health. To inform future methodological development of robust methods for addressing complexity in the evaluation of public health interventions, we undertook a systematic review to map existing evidence, identify gaps in, and strengths and weakness of, the QCA literature to date, and identify the implications of these for conducting and reporting future QCA studies for public health evaluation. We aimed to address the following specific questions [ 27 ]:

1. How is QCA used for public health evaluation? What populations, settings, methods used in source case studies, unit/s and level of analysis (‘cases’), and ‘conditions’ have been included in QCA studies?

2. What strengths and weaknesses have been identified by researchers who have used QCA to understand complex causation in public health evaluation research?

3. What are the existing gaps in, and strengths and weakness of, the QCA literature in public health evaluation, and what implications do these have for future research and reporting of QCA studies for public health?

This systematic review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) on 29 April 2019 ( CRD42019131910 ). A protocol was prepared in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement [ 28 ], and published in 2019 [ 27 ], where the methods are explained in detail. EPPI-Reviewer 4 was used to manage the process and undertake screening of abstracts [ 29 ].

Search strategy

We searched for peer-reviewed published papers in English, which used QCA methods to examine causal complexity in evaluating the implementation, uptake and/or effects of a public health intervention, in any region of the world, for any population. ‘Public health interventions’ were defined as those which aim to promote or protect health, or prevent ill health, in the population. No date exclusions were made, and papers published up to December 2019 were included.

Search strategies used the following phrases “Qualitative Comparative Analysis” and “QCA”, which were combined with the keywords “health”, “public health”, “intervention”, and “wellbeing”. See Additional file 1 for an example. Searches were undertaken on the following databases: PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus. Additional searches were undertaken on Microsoft Academic and Google Scholar in December 2019, where the first pages of results were checked for studies that may have been missed in the initial search. No additional studies were identified. The list of included studies was sent to experts in QCA methods in health and related fields, including authors of included studies and/or those who had published on QCA methodology. This generated no additional studies within scope, but a suggestion to check the COMPASSS (Comparative Methods for Systematic Cross-Case Analysis) database; this was searched, identifying one further study that met the inclusion criteria [ 30 ]. COMPASSS ( https://compasss.org/ ) collates publications of studies using comparative case analysis.

We excluded studies where no intervention was evaluated, which included studies that used QCA to examine public health infrastructure (i.e. staff training) without a specific health outcome, and papers that report on prevalence of health issues (i.e. prevalence of child mortality). We also excluded studies of health systems or services interventions where there was no public health outcome.

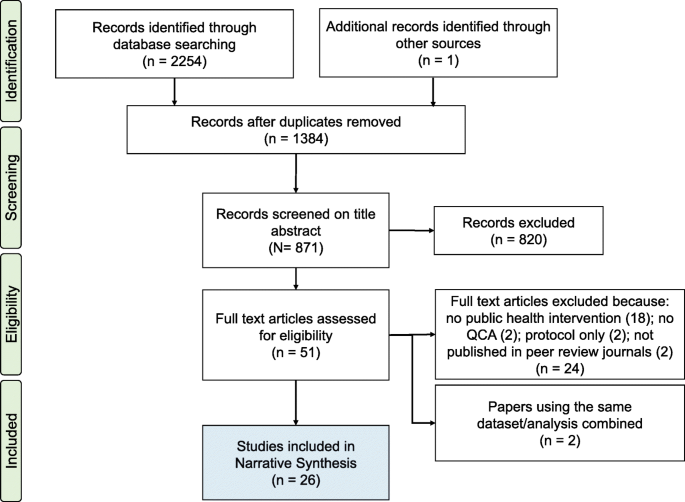

After retrieval, and removal of duplicates, titles and abstracts were screened by one of two authors (BH or JG). Double screening of all records was assisted by EPPI Reviewer 4’s machine learning function. Of the 1384 papers identified after duplicates were removed, we excluded 820 after review of titles and abstracts (Fig. 1 ). The excluded studies included: a large number of papers relating to ‘quantitative coronary angioplasty’ and some which referred to the Queensland Criminal Code (both of which are also abbreviated to ‘QCA’); papers that reported methodological issues but not empirical studies; protocols; and papers that used the phrase ‘qualitative comparative analysis’ to refer to qualitative studies that compared different sub-populations or cases within the study, but did not include formal QCA methods.

Flow Diagram

Full texts of the 51 remaining studies were screened by BH and JG for inclusion, with 10 papers double coded by both authors, with complete agreement. Uncertain inclusions were checked by the third author (MP). Of the full texts, 24 were excluded because: they did not report a public health intervention ( n = 18); had used a methodology inspired by QCA, but had not undertaken a QCA ( n = 2); were protocols or methodological papers only ( n = 2); or were not published in peer-reviewed journals ( n = 2) (see Fig. 1 ).

Data were extracted manually from the 27 remaining full texts by BH and JG. Two papers relating to the same research question and dataset were combined, such that analysis was by study ( n = 26) not by paper. We retrieved data relating to: publication (journal, first author country affiliation, funding reported); the study setting (country/region setting, population targeted by the intervention(s)); intervention(s) studied; methods (aims, rationale for using QCA, crisp or fuzzy set QCA, other analysis methods used); data sources drawn on for cases (source [primary data, secondary data, published analyses], qualitative/quantitative data, level of analysis, number of cases, final causal conditions included in the analysis); outcome explained; and claims made about strengths and weaknesses of using QCA (see Table 1 ). Data were synthesised narratively, using thematic synthesis methods [ 31 , 32 ], with interventions categorised by public health domain and level of intervention.

Quality assessment

There are no reporting guidelines for QCA studies in public health, but there are a number of discussions of best practice in the methodological literature [ 25 , 26 , 33 , 34 ]. These discussions suggest several criteria for strengthening QCA methods that we used as indicators of methodological and/or reporting quality: evidence of familiarity of cases; justification for selection of cases; discussion and justification of set membership score calibration; reporting of truth tables; reporting and justification of solution formula; and reporting of consistency and coverage measures. For studies using csQCA, and claiming an explanatory analysis, we additionally identified whether the number of cases was sufficient for the number of conditions included in the model, using a pragmatic cut-off in line with Marx & Dusa’s guideline thresholds, which indicate how many cases are sufficient for given numbers of conditions to reject a 10% probability that models could be generated with random data [ 26 ].

Overview of scope of QCA research in public health

Twenty-seven papers reporting 26 studies were included in the review (Table 1 ). The earliest was published in 2005, and 17 were published after 2015. The majority ( n = 19) were published in public health/health promotion journals, with the remainder published in other health science ( n = 3) or in social science/management journals ( n = 4). The public health domain(s) addressed by each study were broadly coded by the main area of focus. They included nutrition/obesity ( n = 8); physical activity (PA) (n = 4); health inequalities ( n = 3); mental health ( n = 2); community engagement ( n = 3); chronic condition management ( n = 3); vaccine adoption or implementation (n = 2); programme implementation ( n = 3); breastfeeding ( n = 2); or general population health ( n = 1). The majority ( n = 24) of studies were conducted solely or predominantly in high-income countries (systematic reviews in general searched global sources, but commented that the overwhelming majority of studies were from high-income countries). Country settings included: any ( n = 6); OECD countries ( n = 3); USA ( n = 6); UK ( n = 6) and one each from Nepal, Austria, Belgium, Netherlands and Africa. These largely reflected the first author’s country affiliations in the UK ( n = 13); USA ( n = 9); and one each from South Africa, Austria, Belgium, and the Netherlands. All three studies primarily addressing health inequalities [ 35 , 36 , 37 ] were from the UK.

Eight of the interventions evaluated were individual-level behaviour change interventions (e.g. weight management interventions, case management, self-management for chronic conditions); eight evaluated policy/funding interventions; five explored settings-based health promotion/behaviour change interventions (e.g. schools-based physical activity intervention, store-based food choice interventions); three evaluated community empowerment/engagement interventions, and two studies evaluated networks and their impact on health outcomes.

Methods and data sets used

Fifteen studies used crisp sets (csQCA), 11 used fuzzy sets (fsQCA). No study used mvQCA. Eleven studies included additional analyses of the datasets drawn on for the QCA, including six that used qualitative approaches (narrative synthesis, case comparisons), typically to identify cases or conditions for populating the QCA; and four reporting additional statistical analyses (meta-regression, linear regression) to either identify differences overall between cases prior to conducting a QCA (e.g. [ 38 ]) or to explore correlations in more detail (e.g. [ 39 ]). One study used an additional Boolean configurational technique to reduce the number of conditions in the QCA analysis [ 40 ]. No studies reported aiming to compare the findings from the QCA with those from other techniques for evaluating the uptake or effectiveness of interventions, although some [ 41 , 42 ] were explicitly using the study to showcase the possibilities of QCA compared with other approaches in general. Twelve studies drew on primary data collected specifically for the study, with five of those additionally drawing on secondary data sets; five drew only on secondary data sets, and nine used data from systematic reviews of published research. Seven studies drew primarily on qualitative data, generally derived from interviews or observations.

Many studies were undertaken in the context of one or more trials, which provided evidence of effect. Within single trials, this was generally for a process evaluation, with cases being trial sites. Fernald et al’s study, for instance, was in the context of a trial of a programme to support primary care teams in identifying and implementing self-management support tools for their patients, which measured patient and health care provider level outcomes [ 43 ]. The QCA reported here used qualitative data from the trial to identify a set of necessary conditions for health care provider practices to implement the tools successfully. In studies drawing on data from systematic reviews, cases were always at the level of intervention or intervention component, with data included from multiple trials. Harris et al., for instance, undertook a mixed-methods systematic review of school-based self-management interventions for asthma, using meta-analysis methods to identify effective interventions and QCA methods to identify which intervention features were aligned with success [ 44 ].

The largest number of studies ( n = 10), including all the systematic reviews, analysed cases at the level of the intervention, or a component of the intervention; seven analysed organisational level cases (e.g. school class, network, primary care practice); five analysed sub-national region level cases (e.g. state, local authority area), and two each analysed country or individual level cases. Sample sizes ranged from 10 to 131, with no study having small N (< 10) sample sizes, four having large N (> 50) sample sizes, and the majority (22) being medium N studies (in the range 10–50).

Rationale for using QCA

Most papers reported a rationale for using QCA that mentioned ‘complexity’ or ‘context’, including: noting that QCA is appropriate for addressing causal complexity or multiple pathways to outcome [ 37 , 43 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 ]; noting the appropriateness of the method for providing evidence on how context impacts on interventions [ 41 , 50 ]; or the need for a method that addressed causal asymmetry [ 52 ]. Three stated that the QCA was an ‘exploratory’ analysis [ 53 , 54 , 55 ]. In addition to the empirical aims, several papers (e.g. [ 42 , 48 ]) sought to demonstrate the utility of QCA, or to develop QCA methods for health research (e.g. [ 47 ]).

Reported strengths and weaknesses of approach

There was a general agreement about the strengths of QCA. Specifically, that it was a useful tool to address complex causality, providing a systematic approach to understand the mechanisms at work in implementation across contexts [ 38 , 39 , 43 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 55 , 56 , 57 ], particularly as they relate to (in) effective intervention implementation [ 44 , 51 ] and the evaluation of interventions [ 58 ], or “where it is not possible to identify linearity between variables of interest and outcomes” [ 49 ]. Authors highlighted the strengths of QCA as providing possibilities for examining complex policy problems [ 37 , 59 ]; for testing existing as well as new theory [ 52 ]; and for identifying aspects of interventions which had not been previously perceived as critical [ 41 ] or which may have been missed when drawing on statistical methods that use, for instance, linear additive models [ 42 ]. The strengths of QCA in terms of providing useful evidence for policy were flagged in a number of studies, particularly where the causal recipes suggested that conventional assumptions about effectiveness were not confirmed. Blackman et al., for instance, in a series of studies exploring why unequal health outcomes had narrowed in some areas of the UK and not others, identified poorer outcomes in settings with ‘better’ contracting [ 35 , 36 , 37 ]; Harting found, contrary to theoretical assumptions about the necessary conditions for successful implementation of public health interventions, that a multisectoral network was not a necessary condition [ 30 ].

Weaknesses reported included the limitations of QCA in general for addressing complexity, as well as specific limitations with either the csQCA or the fsQCA methods employed. One general concern discussed across a number of studies was the problem of limited empirical diversity, which resulted in: limitations in the possible number of conditions included in each study, particularly with small N studies [ 58 ]; missing data on important conditions [ 43 ]; or limited reported diversity (where, for instance, data were drawn from systematic reviews, reflecting publication biases which limit reporting of ineffective interventions) [ 41 ]. Reported methodological limitations in small and intermediate N studies included concerns about the potential that case selection could bias findings [ 37 ].

In terms of potential for addressing causal complexity, the limitations of QCA for identifying unintended consequences, tipping points, and/or feedback loops in complex adaptive systems were noted [ 60 ], as were the potential limitations (especially in csQCA studies) of reducing complex conditions, drawn from detailed qualitative understanding, to binary conditions [ 35 ]. The impossibility of doing this was a rationale for using fsQCA in one study [ 57 ], where detailed knowledge of conditions is needed to make theoretically justified calibration decisions. However, others [ 47 ] make the case that csQCA provides more appropriate findings for policy: dichotomisation forces a focus on meaningful distinctions, including those related to decisions that practitioners/policy makers can action. There is, then, a potential trade-off in providing ‘interpretable results’, but ones which preclude potential for utilising more detailed information [ 45 ]. That QCA does not deal with probabilistic causation was noted [ 47 ].

Quality of published studies

Assessment of ‘familiarity with cases’ was made subjectively on the basis of study authors’ reports of their knowledge of the settings (empirical or theoretical) and the descriptions they provided in the published paper: overall, 14 were judged as sufficient, and 12 less than sufficient. Studies which included primary data were more likely to be judged as demonstrating familiarity ( n = 10) than those drawing on secondary sources or systematic reviews, of which only two were judged as demonstrating familiarity. All studies justified how the selection of cases had been made; for those not using the full available population of cases, this was in general (appropriately) done theoretically: following previous research [ 52 ]; purposively to include a range of positive and negative outcomes [ 41 ]; or to include a diversity of cases [ 58 ]. In identifying conditions leading to effective/not effective interventions, one purposive strategy was to include a specified percentage or number of the most effective and least effective interventions (e.g. [ 36 , 40 , 51 , 52 ]). Discussion of calibration of set membership scores was judged adequate in 15 cases, and inadequate in 11; 10 reported raw data matrices in the paper or supplementary material; 21 reported truth tables in the paper or supplementary material. The majority ( n = 21) reported at least some detail on the coverage (the number of cases with a particular configuration) and consistency (the percentage of similar causal configurations which result in the same outcome). The majority ( n = 21) included truth tables (or explicitly provided details of how to obtain them); fewer ( n = 10) included raw data. Only five studies met all six of these quality criteria (evidence of familiarity with cases, justification of case selection, discussion of calibration, reporting truth tables, reporting raw data matrices, reporting coverage and consistency); a further six met at least five of them.

Of the csQCA studies which were not reporting an exploratory analysis, four appeared to have insufficient cases for the large number of conditions entered into at least one of the models reported, with a consequent risk to the validity of the QCA models [ 26 ].

QCA has been widely used in public health research over the last decade to advance understanding of causal inference in complex systems. In this review of published evidence to date, we have identified studies using QCA to examine the configurations of conditions that lead to particular outcomes across contexts. As noted by most study authors, QCA methods have promised advantages over probabilistic statistical techniques for examining causation where systems and/or interventions are complex, providing public health researchers with a method to test the multiple pathways (configurations of conditions), and necessary and sufficient conditions that lead to desired health outcomes.

The origins of QCA approaches are in comparative policy studies. Rihoux et al’s review of peer-reviewed journal articles using QCA methods published up to 2011 found the majority of published examples were from political science and sociology, with fewer than 5% of the 313 studies they identified coming from health sciences [ 61 ]. They also reported few examples of the method being used in policy evaluation and implementation studies [ 62 ]. In the decade since their review of the field [ 61 ], there has been an emerging body of evaluative work in health: we identified 26 studies in the field of public health alone, with the majority published in public health journals. Across these studies, QCA has been used for evaluative questions in a range of settings and public health domains to identify the conditions under which interventions are implemented and/or have evidence of effect for improving population health. All studies included a series of cases that included some with and some without the outcome of interest (such as behaviour change, successful programme implementation, or good vaccination uptake). The dominance of high-income countries in both intervention settings and author affiliations is disappointing, but reflects the disproportionate location of public health research in the global north more generally [ 63 ].

The largest single group of studies included were systematic reviews, using QCA to compare interventions (or intervention components) to identify successful (and non-successful) configurations of conditions across contexts. Here, the value of QCA lies in its potential for synthesis with quantitative meta-synthesis methods to identify the particular conditions or contexts in which interventions or components are effective. As Parrott et al. note, for instance, their meta-analysis could identify probabilistic effects of weight management programmes, and the QCA analysis enabled them to address the “role that the context of the [paediatric weight management] intervention has in influencing how, when, and for whom an intervention mix will be successful” [ 50 ]. However, using QCA to identify configurations of conditions that lead to effective or non- effective interventions across particular areas of population health is an application that does move away in some significant respects from the origins of the method. First, researchers drawing on evidence from systematic reviews for their data are reliant largely on published evidence for information on conditions (such as the organisational contexts in which interventions were implemented, or the types of behaviour change theory utilised). Although guidance for describing interventions [ 64 ] advises key aspects of context are included in reports, this may not include data on the full range of conditions that might be causally important, and review research teams may have limited knowledge of these ‘cases’ themselves. Second, less successful interventions are less likely to be published, potentially limiting the diversity of cases, particularly of cases with unsuccessful outcomes. A strength of QCA is the separate analysis of conditions leading to positive and negative outcomes: this is precluded where there is insufficient evidence on negative outcomes [ 50 ]. Third, when including a range of types of intervention, it can be unclear whether the cases included are truly comparable. A QCA study requires a high degree of theoretical and pragmatic case knowledge on the part of the researcher to calibrate conditions to qualitative anchors: it is reliant on deep understanding of complex contexts, and a familiarity with how conditions interact within and across contexts. Perhaps surprising is that only seven of the studies included here clearly drew on qualitative data, given that QCA is primarily seen as a method that requires thick, detailed knowledge of cases, particularly when the aim is to understand complex causation [ 8 ]. Whilst research teams conducting QCA in the context of systematic reviews may have detailed understanding in general of interventions within their spheres of expertise, they are unlikely to have this for the whole range of cases, particularly where a diverse set of contexts (countries, organisational settings) are included. Making a theoretical case for the valid comparability of such a case series is crucial. There may, then, be limitations in the portability of QCA methods for conducting studies entirely reliant on data from published evidence.

QCA was developed for small and medium N series of cases, and (as in the field more broadly, [ 61 ]), the samples in our studies predominantly had between 10 and 50 cases. However, there is increasing interest in the method as an alternative or complementary technique to regression-oriented statistical methods for larger samples [ 65 ], such as from surveys, where detailed knowledge of cases is likely to be replaced by theoretical knowledge of relationships between conditions (see [ 23 ]). The two larger N (> 100 cases) studies in our sample were an individual level analysis of survey data [ 46 , 47 ] and an analysis of intervention arms from a systematic review [ 50 ]. Larger sample sizes allow more conditions to be included in the analysis [ 23 , 26 ], although for evaluative research, where the aim is developing a causal explanation, rather than simply exploring patterns, there remains a limit to the number of conditions that can be included. As the number of conditions included increases, so too does the number of possible configurations, increasing the chance of unique combinations and of generating spurious solutions with a high level of consistency. As a rule of thumb, once the number of conditions exceeds 6–8 (with up to 50 cases) or 10 (for larger samples), the credibility of solutions may be severely compromised [ 23 ].

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

A systematic review has the potential advantages of transparency and rigour and, if not exhaustive, our search is likely to be representative of the body of research using QCA for evaluative public health research up to 2020. However, a limitation is the inevitable difficulty in operationalising a ‘public health’ intervention. Exclusions on scope are not straightforward, given that most social, environmental and political conditions impact on public health, and arguably a greater range of policy and social interventions (such as fiscal or trade policies) that have been the subject of QCA analyses could have been included, or a greater range of more clinical interventions. However, to enable a manageable number of papers to review, and restrict our focus to those papers that were most directly applicable to (and likely to be read by) those in public health policy and practice, we operationalised ‘public health interventions’ as those which were likely to be directly impacting on population health outcomes, or on behaviours (such as increased physical activity) where there was good evidence for causal relationships with public health outcomes, and where the primary research question of the study examined the conditions leading to those outcomes. This review has, of necessity, therefore excluded a considerable body of evidence likely to be useful for public health practice in terms of planning interventions, such as studies on how to better target smoking cessation [ 66 ] or foster social networks [ 67 ] where the primary research question was on conditions leading to these outcomes, rather than on conditions for outcomes of specific interventions. Similarly, there are growing number of descriptive epidemiological studies using QCA to explore factors predicting outcomes across such diverse areas as lupus and quality of life [ 68 ]; length of hospital stay [ 69 ]; constellations of factors predicting injury [ 70 ]; or the role of austerity, crisis and recession in predicting public health outcomes [ 71 ]. Whilst there is undoubtedly useful information to be derived from studying the conditions that lead to particular public health problems, these studies were not directly evaluating interventions, so they were also excluded.

Restricting our search to publications in English and to peer reviewed publications may have missed bodies of work from many regions, and has excluded research from non-governmental organisations using QCA methods in evaluation. As this is a rapidly evolving field, with relatively recent uptake in public health (all our included studies were after 2005), our studies may not reflect the most recent advances in the area.

Implications for conducting and reporting QCA studies

This systematic review has reviewed studies that deployed an emergent methodology, which has no reporting guidelines and has had, to date, a relatively low level of awareness among many potential evidence users in public health. For this reason, many of the studies reviewed were relatively detailed on the methods used, and the rationale for utilising QCA.

We did not assess quality directly, but used indicators of good practice discussed in QCA methodological literature, largely written for policy studies scholars, and often post-dating the publication dates of studies included in this review. It is also worth noting that, given the relatively recent development of QCA methods, methodological debate is still thriving on issues such as the reliability of causal inferences [ 72 ], alongside more general critiques of the usefulness of the method for policy decisions (see, for instance, [ 73 ]). The authors of studies included in this review also commented directly on methodological development: for instance, Thomas et al. suggests that QCA may benefit from methods development for sensitivity analyses around calibration decisions [ 42 ].

However, we selected quality criteria that, we argue, are relevant for public health research> Justifying the selection of cases, discussing and justifying the calibration of set membership, making data sets available, and reporting truth tables, consistency and coverage are all good practice in line with the usual requirements of transparency and credibility in methods. When QCA studies aim to provide explanation of outcomes (rather than exploring configurations), it is also vital that they are reported in ways that enhance the credibility of claims made, including justifying the number of conditions included relative to cases. Few of the studies published to date met all these criteria, at least in the papers included here (although additional material may have been provided in other publications). To improve the future discoverability and uptake up of QCA methods in public health, and to strengthen the credibility of findings from these methods, we therefore suggest the following criteria should be considered by authors and reviewers for reporting QCA studies which aim to provide causal evidence about the configurations of conditions that lead to implementation or outcomes:

The paper title and abstract state the QCA design;

The sampling unit for the ‘case’ is clearly defined (e.g.: patient, specified geographical population, ward, hospital, network, policy, country);

The population from which the cases have been selected is defined (e.g.: all patients in a country with X condition, districts in X country, tertiary hospitals, all hospitals in X country, all health promotion networks in X province, European policies on smoking in outdoor places, OECD countries);

The rationale for selection of cases from the population is justified (e.g.: whole population, random selection, purposive sample);

There are sufficient cases to provide credible coverage across the number of conditions included in the model, and the rationale for the number of conditions included is stated;

Cases are comparable;

There is a clear justification for how choices of relevant conditions (or ‘aspects of context’) have been made;

There is sufficient transparency for replicability: in line with open science expectations, datasets should be available where possible; truth tables should be reported in publications, and reports of coverage and consistency provided.

Implications for future research

In reviewing methods for evaluating natural experiments, Craig et al. focus on statistical techniques for enhancing causal inference, noting only that what they call ‘qualitative’ techniques (the cited references for these are all QCA studies) require “further studies … to establish their validity and usefulness” [ 2 ]. The studies included in this review have demonstrated that QCA is a feasible method when there are sufficient (comparable) cases for identifying configurations of conditions under which interventions are effective (or not), or are implemented (or not). Given ongoing concerns in public health about how best to evaluate interventions across complex contexts and systems, this is promising. This review has also demonstrated the value of adding QCA methods to the tool box of techniques for evaluating interventions such as public policies, health promotion programmes, and organisational changes - whether they are implemented in a randomised way or not. Many of the studies in this review have clearly generated useful evidence: whether this evidence has had more or less impact, in terms of influencing practice and policy, or is more valid, than evidence generated by other methods is not known. Validating the findings of a QCA study is perhaps as challenging as validating the findings from any other design, given the absence of any gold standard comparators. Comparisons of the findings of QCA with those from other methods are also typically constrained by the rather different research questions asked, and the different purposes of the analysis. In our review, QCA were typically used alongside other methods to address different questions, rather than to compare methods. However, as the field develops, follow up studies, which evaluate outcomes of interventions designed in line with conditions identified as causal in prior QCAs, might be useful for contributing to validation.

This review was limited to public health evaluation research: other domains that would be useful to map include health systems/services interventions and studies used to design or target interventions. There is also an opportunity to broaden the scope of the field, particularly for addressing some of the more intractable challenges for public health research. Given the limitations in the evidence base on what works to address inequalities in health, for instance [ 74 ], QCA has potential here, to help identify the conditions under which interventions do or do not exacerbate unequal outcomes, or the conditions that lead to differential uptake or impacts across sub-population groups. It is perhaps surprising that relatively few of the studies in this review included cases at the level of country or region, the traditional level for QCA studies. There may be scope for developing international comparisons for public health policy, and using QCA methods at the case level (nation, sub-national region) of classic policy studies in the field. In the light of debate around COVID-19 pandemic response effectiveness, comparative studies across jurisdictions might shed light on issues such as differential population responses to vaccine uptake or mask use, for example, and these might in turn be considered as conditions in causal configurations leading to differential morbidity or mortality outcomes.

When should be QCA be considered?

Public health evaluations typically assess the efficacy, effectiveness or cost-effectiveness of interventions and the processes and mechanisms through which they effect change. There is no perfect evaluation design for achieving these aims. As in other fields, the choice of design will in part depend on the availability of counterfactuals, the extent to which the investigator can control the intervention, and the range of potential cases and contexts [ 75 ], as well as political considerations, such as the credibility of the approach with key stakeholders [ 76 ]. There are inevitably ‘horses for courses’ [ 77 ]. The evidence from this review suggests that QCA evaluation approaches are feasible when there is a sufficient number of comparable cases with and without the outcome of interest, and when the investigators have, or can generate, sufficiently in-depth understanding of those cases to make sense of connections between conditions, and to make credible decisions about the calibration of set membership. QCA may be particularly relevant for understanding multiple causation (that is, where different configurations might lead to the same outcome), and for understanding the conditions associated with both lack of effect and effect. As a stand-alone approach, QCA might be particularly valuable for national and regional comparative studies of the impact of policies on public health outcomes. Alongside cluster randomised trials of interventions, or alongside systematic reviews, QCA approaches are especially useful for identifying core combinations of causal conditions for success and lack of success in implementation and outcome.

Conclusions

QCA is a relatively new approach for public health research, with promise for contributing to much-needed methodological development for addressing causation in complex systems. This review has demonstrated the large range of evaluation questions that have been addressed to date using QCA, including contributions to process evaluations of trials and for exploring the conditions leading to effectiveness (or not) in systematic reviews of interventions. There is potential for QCA to be more widely used in evaluative research, to identify the conditions under which interventions across contexts are implemented or not, and the configurations of conditions associated with effect or lack of evidence of effect. However, QCA will not be appropriate for all evaluations, and cannot be the only answer to addressing complex causality. For explanatory questions, the approach is most appropriate when there is a series of enough comparable cases with and without the outcome of interest, and where the researchers have detailed understanding of those cases, and conditions. To improve the credibility of findings from QCA for public health evidence users, we recommend that studies are reported with the usual attention to methodological transparency and data availability, with key details that allow readers to judge the credibility of causal configurations reported. If the use of QCA continues to expand, it may be useful to develop more comprehensive consensus guidelines for conduct and reporting.

Availability of data and materials

Full search strategies and extraction forms are available by request from the first author.

Abbreviations

Comparative Methods for Systematic Cross-Case Analysis

crisp set QCA

fuzzy set QCA

multi-value QCA

Medical Research Council

- Qualitative Comparative Analysis

randomised control trial

Physical Activity

Green J, Roberts H, Petticrew M, Steinbach R, Goodman A, Jones A, et al. Integrating quasi-experimental and inductive designs in evaluation: a case study of the impact of free bus travel on public health. Evaluation. 2015;21(4):391–406. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389015605205 .

Article Google Scholar

Craig P, Katikireddi SV, Leyland A, Popham F. Natural experiments: an overview of methods, approaches, and contributions to public health intervention research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38(1):39–56. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044327 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Shiell A, Hawe P, Gold L. Complex interventions or complex systems? Implications for health economic evaluation. BMJ. 2008;336(7656):1281–3. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39569.510521.AD .

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655.

Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, Bond L, Bonell C, Hardeman W, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2015;350(mar19 6):h1258. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h1258 .

Pattyn V, Álamos-Concha P, Cambré B, Rihoux B, Schalembier B. Policy effectiveness through Configurational and mechanistic lenses: lessons for concept development. J Comp Policy Anal Res Pract. 2020;0:1–18.

Google Scholar

Byrne D. Evaluating complex social interventions in a complex world. Evaluation. 2013;19(3):217–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389013495617 .

Gerrits L, Pagliarin S. Social and causal complexity in qualitative comparative analysis (QCA): strategies to account for emergence. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2020;0:1–14, doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2020.1799636 .

Grant RL, Hood R. Complex systems, explanation and policy: implications of the crisis of replication for public health research. Crit Public Health. 2017;27(5):525–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2017.1282603 .

Rutter H, Savona N, Glonti K, Bibby J, Cummins S, Finegood DT, et al. The need for a complex systems model of evidence for public health. Lancet. 2017;390(10112):2602–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31267-9 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Greenhalgh T, Papoutsi C. Studying complexity in health services research: desperately seeking an overdue paradigm shift. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):95. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1089-4 .

Craig P, Di Ruggiero E, Frohlich KL, Mykhalovskiy E and White M, on behalf of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR)–National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Context Guidance Authors Group. Taking account of context in population health intervention research: guidance for producers, users and funders of research. Southampton: NIHR Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre; 2018.

Paparini S, Green J, Papoutsi C, Murdoch J, Petticrew M, Greenhalgh T, et al. Case study research for better evaluations of complex interventions: rationale and challenges. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):301. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01777-6 .