Group Writing

What this handout is about.

Whether in the academic world or the business world, all of us are likely to participate in some form of group writing—an undergraduate group project for a class, a collaborative research paper or grant proposal, or a report produced by a business team. Writing in a group can have many benefits: multiple brains are better than one, both for generating ideas and for getting a job done. However, working in a group can sometimes be stressful because there are various opinions and writing styles to incorporate into one final product that pleases everyone. This handout will offer an overview of the collaborative process, strategies for writing successfully together, and tips for avoiding common pitfalls. It will also include links to some other handouts that may be especially helpful as your group moves through the writing process.

Disclaimer and disclosure

As this is a group writing handout, several Writing Center coaches worked together to create it. No coaches were harmed in this process; however, we did experience both the pros and the cons of the collaborative process. We have personally tested the various methods for sharing files and scheduling meetings that are described here. However, these are only our suggestions; we do not advocate any particular service or site.

The spectrum of collaboration in group writing

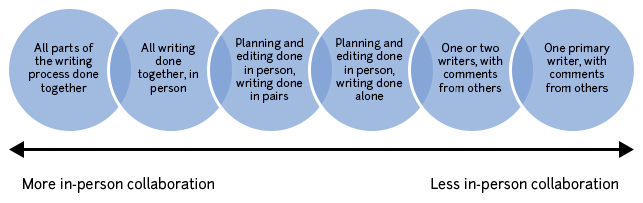

All writing can be considered collaborative in a sense, though we often don’t think of it that way. It would be truly surprising to find an author whose writing, even if it was completed independently, had not been influenced at some point by discussions with friends or colleagues. The range of possible collaboration varies from a group of co-authors who go through each portion of the writing process together, writing as a group with one voice, to a group with a primary author who does the majority of the work and then receives comments or edits from the co-authors.

Group projects for classes should usually fall towards the middle to left side of this diagram, with group members contributing roughly equally. However, in collaborations on research projects, the level of involvement of the various group members may vary widely. The key to success in either case is to be clear about group member responsibilities and expectations and to give credit (authorship) to members who contribute an appropriate amount. It may be useful to credit each group member for their various contributions.

Overview of steps of the collaborative process

Here we outline the steps of the collaborative process. You can use these questions to focus your thinking at each stage.

- Share ideas and brainstorm together.

- Formulate a draft thesis or argument .

- Think about your assignment and the final product. What should it look like? What is its purpose? Who is the intended audience ?

- Decide together who will write which parts of the paper/project.

- What will the final product look like?

- Arrange meetings: How often will the group or subsets of the group meet? When and where will the group meet? If the group doesn’t meet in person, how will information be shared?

- Scheduling: What is the deadline for the final product? What are the deadlines for drafts?

- How will the group find appropriate sources (books, journal articles, newspaper articles, visual media, trustworthy websites, interviews)? If the group will be creating data by conducting research, how will that process work?

- Who will read and process the information found? This task again may be done by all members or divided up amongst members so that each person becomes the expert in one area and then teaches the rest of the group.

- Think critically about the sources and their contributions to your topic. Which evidence should you include or exclude? Do you need more sources?

- Analyze the data. How will you interpret your findings? What is the best way to present any relevant information to your readers-should you include pictures, graphs, tables, and charts, or just written text?

- Note that brainstorming the main points of your paper as a group is helpful, even if separate parts of the writing are assigned to individuals. You’ll want to be sure that everyone agrees on the central ideas.

- Where does your individual writing fit into the whole document?

- Writing together may not be feasible for longer assignments or papers with coauthors at different universities, and it can be time-consuming. However, writing together does ensure that the finished document has one cohesive voice.

- Talk about how the writing session should go BEFORE you get started. What goals do you have? How will you approach the writing task at hand?

- Many people find it helpful to get all of the ideas down on paper in a rough form before discussing exact phrasing.

- Remember that everyone has a different writing style! The most important thing is that your sentences be clear to readers.

- If your group has drafted parts of the document separately, merge your ideas together into a single document first, then focus on meshing the styles. The first concern is to create a coherent product with a logical flow of ideas. Then the stylistic differences of the individual portions must be smoothed over.

- Revise the ideas and structure of the paper before worrying about smaller, sentence-level errors (like problems with punctuation, grammar, or word choice). Is the argument clear? Is the evidence presented in a logical order? Do the transitions connect the ideas effectively?

- Proofreading: Check for typos, spelling errors, punctuation problems, formatting issues, and grammatical mistakes. Reading the paper aloud is a very helpful strategy at this point.

Helpful collaborative writing strategies

Attitude counts for a lot.

Group work can be challenging at times, but a little enthusiasm can go a long way to helping the momentum of the group. Keep in mind that working in a group provides a unique opportunity to see how other people write; as you learn about their writing processes and strategies, you can reflect on your own. Working in a group inherently involves some level of negotiation, which will also facilitate your ability to skillfully work with others in the future.

Remember that respect goes along way! Group members will bring different skill sets and various amounts and types of background knowledge to the table. Show your fellow writers respect by listening carefully, talking to share your ideas, showing up on time for meetings, sending out drafts on schedule, providing positive feedback, and taking responsibility for an appropriate share of the work.

Start early and allow plenty of time for revising

Getting started early is important in individual projects; however, it is absolutely essential in group work. Because of the multiple people involved in researching and writing the paper, there are aspects of group projects that take additional time, such as deciding and agreeing upon a topic. Group projects should be approached in a structured way because there is simply less scheduling flexibility than when you are working alone. The final product should reflect a unified, cohesive voice and argument, and the only way of accomplishing this is by producing multiple drafts and revising them multiple times.

Plan a strategy for scheduling

One of the difficult aspects of collaborative writing is finding times when everyone can meet. Much of the group’s work may be completed individually, but face-to-face meetings are useful for ensuring that everyone is on the same page. Doodle.com , whenisgood.net , and needtomeet.com are free websites that can make scheduling easier. Using these sites, an organizer suggests multiple dates and times for a meeting, and then each group member can indicate whether they are able to meet at the specified times.

It is very important to set deadlines for drafts; people are busy, and not everyone will have time to read and respond at the last minute. It may help to assign a group facilitator who can send out reminders of the deadlines. If the writing is for a co-authored research paper, the lead author can take responsibility for reminding others that comments on a given draft are due by a specific date.

Submitting drafts at least one day ahead of the meeting allows other authors the opportunity to read over them before the meeting and arrive ready for a productive discussion.

Find a convenient and effective way to share files

There are many different ways to share drafts, research materials, and other files. Here we describe a few of the potential options we have explored and found to be functional. We do not advocate any one option, and we realize there are other equally useful options—this list is just a possible starting point for you:

- Email attachments. People often share files by email; however, especially when there are many group members or there is a flurry of writing activity, this can lead to a deluge of emails in everyone’s inboxes and significant confusion about which file version is current.

- Google documents . Files can be shared between group members and are instantaneously updated, even if two members are working at once. Changes made by one member will automatically appear on the document seen by all members. However, to use this option, every group member must have a Gmail account (which is free), and there are often formatting issues when converting Google documents back to Microsoft Word.

- Dropbox . Dropbox.com is free to join. It allows you to share up to 2GB of files, which can then be synched and accessible from multiple computers. The downside of this approach is that everyone has to join, and someone must install the software on at least one personal computer. Dropbox can then be accessed from any computer online by logging onto the website.

- Common server space. If all group members have access to a shared server space, this is often an ideal solution. Members of a lab group or a lab course with available server space typically have these resources. Just be sure to make a folder for your project and clearly label your files.

Note that even when you are sharing or storing files for group writing projects in a common location, it is still essential to periodically make back-up copies and store them on your own computer! It is never fun to lose your (or your group’s) hard work.

Try separating the tasks of revising and editing/proofreading

It may be helpful to assign giving feedback on specific items to particular group members. First, group members should provide general feedback and comments on content. Only after revising and solidifying the main ideas and structure of the paper should you move on to editing and proofreading. After all, there is no point in spending your time making a certain sentence as beautiful and correct as possible when that sentence may later be cut out. When completing your final revisions, it may be helpful to assign various concerns (for example, grammar, organization, flow, transitions, and format) to individual group members to focus this process. This is an excellent time to let group members play to their strengths; if you know that you are good at transitions, offer to take care of that editing task.

Your group project is an opportunity to become experts on your topic. Go to the library (in actuality or online), collect relevant books, articles, and data sources, and consult a reference librarian if you have any issues. Talk to your professor or TA early in the process to ensure that the group is on the right track. Find experts in the field to interview if it is appropriate. If you have data to analyze, meet with a statistician. If you are having issues with the writing, use the online handouts at the Writing Center or come in for a face-to-face meeting: a coach can meet with you as a group or one-on-one.

Immediately dividing the writing into pieces

While this may initially seem to be the best way to approach a group writing process, it can also generate more work later on, when the parts written separately must be put together into a unified document. The different pieces must first be edited to generate a logical flow of ideas, without repetition. Once the pieces have been stuck together, the entire paper must be edited to eliminate differences in style and any inconsistencies between the individual authors’ various chunks. Thus, while it may take more time up-front to write together, in the end a closer collaboration can save you from the difficulties of combining pieces of writing and may create a stronger, more cohesive document.

Procrastination

Although this is solid advice for any project, it is even more essential to start working on group projects in a timely manner. In group writing, there are more people to help with the work-but there are also multiple schedules to juggle and more opinions to seek.

Being a solo group member

Not everyone enjoys working in groups. You may truly desire to go solo on this project, and you may even be capable of doing a great job on your own. However, if this is a group assignment, then the prompt is asking for everyone to participate. If you are feeling the need to take over everything, try discussing expectations with your fellow group members as well as the teaching assistant or professor. However, always address your concerns with group members first. Try to approach the group project as a learning experiment: you are learning not only about the project material but also about how to motivate others and work together.

Waiting for other group members to do all of the work

If this is a project for a class, you are leaving your grade in the control of others. Leaving the work to everyone else is not fair to your group mates. And in the end, if you do not contribute, then you are taking credit for work that you did not do; this is a form of academic dishonesty. To ensure that you can do your share, try to volunteer early for a portion of the work that you are interested in or feel you can manage.

Leaving all the end work to one person

It may be tempting to leave all merging, editing, and/or presentation work to one person. Be careful. There are several reasons why this may be ill-advised. 1) The editor/presenter may not completely understand every idea, sentence, or word that another author wrote, leading to ambiguity or even mistakes in the end paper or presentation. 2) Editing is tough, time-consuming work. The editor often finds himself or herself doing more work than was expected as they try to decipher and merge the original contributions under the time pressure of an approaching deadline. If you decide to follow this path and have one person combine the separate writings of many people, be sure to leave plenty of time for a final review by all of the writers. Ask the editor to send out the final draft of the completed work to each of the authors and let every contributor review and respond to the final product. Ideally, there should also be a test run of any live presentations that the group or a representative may make.

Entirely negative critiques

When giving feedback or commenting on the work of other group members, focusing only on “problems” can be overwhelming and put your colleagues on the defensive. Try to highlight the positive parts of the project in addition to pointing out things that need work. Remember that this is constructive feedback, so don’t forget to add concrete, specific suggestions on how to proceed. It can also be helpful to remind yourself that many of your comments are your own opinions or reactions, not absolute, unquestionable truths, and then phrase what you say accordingly. It is much easier and more helpful to hear “I had trouble understanding this paragraph because I couldn’t see how it tied back to our main argument” than to hear “this paragraph is unclear and irrelevant.”

Writing in a group can be challenging, but it is also a wonderful opportunity to learn about your topic, the writing process, and the best strategies for collaboration. We hope that our tips will help you and your group members have a great experience.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Cross, Geoffrey. 1994. Collaboration and Conflict: A Contextual Exploration of Group Writing and Positive Emphasis . Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Ede, Lisa S., and Andrea Lunsford. 1990. Singular Texts/Plural Authors: Perspectives on Collaborative Writing . Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Speck, Bruce W. 2002. Facilitating Students’ Collaborative Writing . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Eberly Center

Teaching excellence & educational innovation, what are the benefits of group work.

“More hands make for lighter work.” “Two heads are better than one.” “The more the merrier.”

These adages speak to the potential groups have to be more productive, creative, and motivated than individuals on their own.

Benefits for students

Group projects can help students develop a host of skills that are increasingly important in the professional world (Caruso & Woolley, 2008; Mannix & Neale, 2005). Positive group experiences, moreover, have been shown to contribute to student learning, retention and overall college success (Astin, 1997; Tinto, 1998; National Survey of Student Engagement, 2006).

Properly structured, group projects can reinforce skills that are relevant to both group and individual work, including the ability to:

- Break complex tasks into parts and steps

- Plan and manage time

- Refine understanding through discussion and explanation

- Give and receive feedback on performance

- Challenge assumptions

- Develop stronger communication skills.

Group projects can also help students develop skills specific to collaborative efforts, allowing students to...

- Tackle more complex problems than they could on their own.

- Delegate roles and responsibilities.

- Share diverse perspectives.

- Pool knowledge and skills.

- Hold one another (and be held) accountable.

- Receive social support and encouragement to take risks.

- Develop new approaches to resolving differences.

- Establish a shared identity with other group members.

- Find effective peers to emulate.

- Develop their own voice and perspectives in relation to peers.

While the potential learning benefits of group work are significant, simply assigning group work is no guarantee that these goals will be achieved. In fact, group projects can – and often do – backfire badly when they are not designed , supervised , and assessed in a way that promotes meaningful teamwork and deep collaboration.

Benefits for instructors

Faculty can often assign more complex, authentic problems to groups of students than they could to individuals. Group work also introduces more unpredictability in teaching, since groups may approach tasks and solve problems in novel, interesting ways. This can be refreshing for instructors. Additionally, group assignments can be useful when there are a limited number of viable project topics to distribute among students. And they can reduce the number of final products instructors have to grade.

Whatever the benefits in terms of teaching, instructors should take care only to assign as group work tasks that truly fulfill the learning objectives of the course and lend themselves to collaboration. Instructors should also be aware that group projects can add work for faculty at different points in the semester and introduce its own grading complexities .

Astin, A. (1993). What matters in college? Four critical years revisited. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Caruso, H.M., & Wooley, A.W. (2008). Harnessing the power of emergent interdependence to promote diverse team collaboration. Diversity and Groups. 11, 245-266.

Mannix, E., & Neale, M.A. (2005). What differences make a difference? The promise and reality of diverse teams in organizations. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 6(2), 31-55.

National Survey of Student Engagement Report. (2006). http://nsse.iub.edu/NSSE_2006_Annual_Report/docs/NSSE_2006_Annual_Report.pdf .

Tinto, V. (1987). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Business Teamwork

My Experience Working in a Group: a Reflection

Table of contents, challenges of group work, benefits and learning opportunities, lessons learned.

- Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (2009). An educational psychology success story: Social interdependence theory and cooperative learning. Educational researcher, 38(5), 365-379.

- Belbin, R. M. (2012). Team roles at work. Taylor & Francis.

- Tuckman, B. W. (1965). Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 63(6), 384-399.

- Forsyth, D. R. (2014). Group dynamics (6th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Katzenbach, J. R., & Smith, D. K. (2015). The wisdom of teams: Creating the high-performance organization. Harvard Business Review Press.

*minimum deadline

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below

- Internal Control

- Advertising

- Strategic Management

Related Essays

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

How to write a Reflection on Group Work Essay

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

Here are the exact steps you need to follow for a reflection on group work essay.

- Explain what Reflection Is

- Explore the benefits of group work

- Explore the challenges group

- Give examples of the benefits and challenges your group faced

- Discuss how your group handled your challenges

- Discuss what you will do differently next time

Do you have to reflect on how your group work project went?

This is a super common essay that teachers assign. So, let’s have a look at how you can go about writing a superb reflection on your group work project that should get great grades.

The essay structure I outline below takes the funnel approach to essay writing: it starts broad and general, then zooms in on your specific group’s situation.

Disclaimer: Make sure you check with your teacher to see if this is a good style to use for your essay. Take a draft to your teacher to get their feedback on whether it’s what they’re looking for!

This is a 6-step essay (the 7 th step is editing!). Here’s a general rule for how much depth to go into depending on your word count:

- 1500 word essay – one paragraph for each step, plus a paragraph each for the introduction and conclusion ;

- 3000 word essay – two paragraphs for each step, plus a paragraph each for the introduction and conclusion;

- 300 – 500 word essay – one or two sentences for each step.

Adjust this essay plan depending on your teacher’s requirements and remember to always ask your teacher, a classmate or a professional tutor to review the piece before submitting.

Here’s the steps I’ll outline for you in this advice article:

Step 1. Explain what ‘Reflection’ Is

You might have heard that you need to define your terms in essays. Well, the most important term in this essay is ‘reflection’.

So, let’s have a look at what reflection is…

Reflection is the process of:

- Pausing and looking back at what has just happened; then

- Thinking about how you can get better next time.

Reflection is encouraged in most professions because it’s believed that reflection helps you to become better at your job – we could say ‘reflection makes you a better practitioner’.

Think about it: let’s say you did a speech in front of a crowd. Then, you looked at video footage of that speech and realised you said ‘um’ and ‘ah’ too many times. Next time, you’re going to focus on not saying ‘um’ so that you’ll do a better job next time, right?

Well, that’s reflection: thinking about what happened and how you can do better next time.

It’s really important that you do both of the above two points in your essay. You can’t just say what happened. You need to say how you will do better next time in order to get a top grade on this group work reflection essay.

Scholarly Sources to Cite for Step 1

Okay, so you have a good general idea of what reflection is. Now, what scholarly sources should you use when explaining reflection? Below, I’m going to give you two basic sources that would usually be enough for an undergraduate essay. I’ll also suggest two more sources for further reading if you really want to shine!

I recommend these two sources to cite when explaining what reflective practice is and how it occurs. They are two of the central sources on reflective practice:

- Describe what happened during the group work process

- Explain how you felt during the group work process

- Look at the good and bad aspects of the group work process

- What were some of the things that got in the way of success? What were some things that helped you succeed?

- What could you have done differently to improve the situation?

- Action plan. What are you going to do next time to make the group work process better?

- What? Explain what happened

- So What? Explain what you learned

- Now What? What can I do next time to make the group work process better?

Possible Sources:

Bassot, B. (2015). The reflective practice guide: An interdisciplinary approach to critical reflection . Routledge.

Brock, A. (2014). What is reflection and reflective practice?. In The Early Years Reflective Practice Handbook (pp. 25-39). Routledge.

Gibbs, G. (1988) Learning by Doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods . Further Education Unit, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford.

Rolfe, G., Freshwater, D., Jasper, M. (2001). Critical reflection in nursing and the helping professions: a user’s guide. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Extension Sources for Top Students

Now, if you want to go deeper and really show off your knowledge, have a look at these two scholars:

- John Dewey – the first major scholar to come up with the idea of reflective practice

- Donald Schön – technical rationality, reflection in action vs. reflection on action

Get a Pdf of this article for class

Enjoy subscriber-only access to this article’s pdf

Step 2. Explore the general benefits of group work for learning

Once you have given an explanation of what group work is (and hopefully cited Gibbs, Rolfe, Dewey or Schon), I recommend digging into the benefits of group work for your own learning.

The teacher gave you a group work task for a reason: what is that reason?

You’ll need to explain the reasons group work is beneficial for you. This will show your teacher that you understand what group work is supposed to achieve. Here’s some ideas:

- Multiple Perspectives. Group work helps you to see things from other people’s perspectives. If you did the task on your own, you might not have thought of some of the ideas that your team members contributed to the project.

- Contribution of Unique Skills. Each team member might have a different set of skills they can bring to the table. You can explain how groups can make the most of different team members’ strengths to make the final contribution as good as it can be. For example, one team member might be good at IT and might be able to put together a strong final presentation, while another member might be a pro at researching using google scholar so they got the task of doing the initial scholarly research.

- Improved Communication Skills. Group work projects help you to work on your communication skills. Communication skills required in group work projects include speaking in turn, speaking up when you have ideas, actively listening to other team members’ contributions, and crucially making compromises for the good of the team.

- Learn to Manage Workplace Conflict. Lastly, your teachers often assign you group work tasks so you can learn to manage conflict and disagreement. You’ll come across this a whole lot in the workplace, so your teachers want you to have some experience being professional while handling disagreements.

You might be able to add more ideas to this list, or you might just want to select one or two from that list to write about depending on the length requirements for the essay.

Scholarly Sources for Step 3

Make sure you provide citations for these points above. You might want to use google scholar or google books and type in ‘Benefits of group work’ to find some quality scholarly sources to cite.

Step 3. Explore the general challenges group work can cause

Step 3 is the mirror image of Step 2. For this step, explore the challenges posed by group work.

Students are usually pretty good at this step because you can usually think of some aspects of group work that made you anxious or frustrated. Here are a few common challenges that group work causes:

- Time Consuming. You need to organize meetups and often can’t move onto the next component of the project until everyone has agree to move on. When working on your own you can just crack on and get it done. So, team work often takes a lot of time and requires significant pre-planning so you don’t miss your submission deadlines!

- Learning Style Conflicts. Different people learn in different ways. Some of us like to get everything done at the last minute or are not very meticulous in our writing. Others of us are very organized and detailed and get anxious when things don’t go exactly how we expect. This leads to conflict and frustration in a group work setting.

- Free Loaders. Usually in a group work project there’s people who do more work than others. The issue of free loaders is always going to be a challenge in group work, and you can discuss in this section how ensuring individual accountability to the group is a common group work issue.

- Communication Breakdown. This is one especially for online students. It’s often the case that you email team members your ideas or to ask them to reply by a deadline and you don’t hear back from them. Regular communication is an important part of group work, yet sometimes your team members will let you down on this part.

As with Step 3, consider adding more points to this list if you need to, or selecting one or two if your essay is only a short one.

8 Pros And Cons Of Group Work At University

| Pros of Group Work | Cons of Group Work |

|---|---|

| Members of your team will have different perspectives to bring to the table. Embrace team brainstorming to bring in more ideas than you would on your own. | You can get on with an individual task at your own pace, but groups need to arrange meet-ups and set deadlines to function effectively. This is time-consuming and requires pre-planning. |

| Each of your team members will have different skills. Embrace your IT-obsessed team member’s computer skills; embrace the organizer’s skills for keeping the group on track, and embrace the strongest writer’s editing skills to get the best out of your group. | Some of your team members will want to get everything done at once; others will procrastinate frequently. You might also have conflicts in strategic directions depending on your different approaches to learning. |

| Use group work to learn how to communicate more effectively. Focus on active listening and asking questions that will prompt your team members to expand on their ideas. | Many groups struggle with people who don’t carry their own weight. You need to ensure you delegate tasks to the lazy group members and be stern with them about sticking to the deadlines they agreed upon. |

| In the workforce you’re not going to get along with your colleagues. Use group work at university to learn how to deal with difficult team members calmly and professionally. | It can be hard to get group members all on the same page. Members don’t rely to questions, get anxiety and shut down, or get busy with their own lives. It’s important every team member is ready and available for ongoing communication with the group. |

You’ll probably find you can cite the same scholarly sources for both steps 2 and 3 because if a source discusses the benefits of group work it’ll probably also discuss the challenges.

Step 4. Explore the specific benefits and challenges your group faced

Step 4 is where you zoom in on your group’s specific challenges. Have a think: what were the issues you really struggled with as a group?

- Was one team member absent for a few of the group meetings?

- Did the group have to change some deadlines due to lack of time?

- Were there any specific disagreements you had to work through?

- Did a group member drop out of the group part way through?

- Were there any communication break downs?

Feel free to also mention some things your group did really well. Have a think about these examples:

- Was one member of the group really good at organizing you all?

- Did you make some good professional relationships?

- Did a group member help you to see something from an entirely new perspective?

- Did working in a group help you to feel like you weren’t lost and alone in the process of completing the group work component of your course?

Here, because you’re talking about your own perspectives, it’s usually okay to use first person language (but check with your teacher). You are also talking about your own point of view so citations might not be quite as necessary, but it’s still a good idea to add in one or two citations – perhaps to the sources you cited in Steps 2 and 3?

Step 5. Discuss how your group managed your challenges

Step 5 is where you can explore how you worked to overcome some of the challenges you mentioned in Step 4.

So, have a think:

- Did your group make any changes part way through the project to address some challenges you faced?

- Did you set roles or delegate tasks to help ensure the group work process went smoothly?

- Did you contact your teacher at any point for advice on how to progress in the group work scenario?

- Did you use technology such as Google Docs or Facebook Messenger to help you to collaborate more effectively as a team?

In this step, you should be showing how your team was proactive in reflecting on your group work progress and making changes throughout the process to ensure it ran as smoothly as possible. This act of making little changes throughout the group work process is what’s called ‘Reflection in Action’ (Schön, 2017).

Scholarly Source for Step 5

Schön, D. A. (2017). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action . Routledge.

Step 6. Conclude by exploring what you will do differently next time

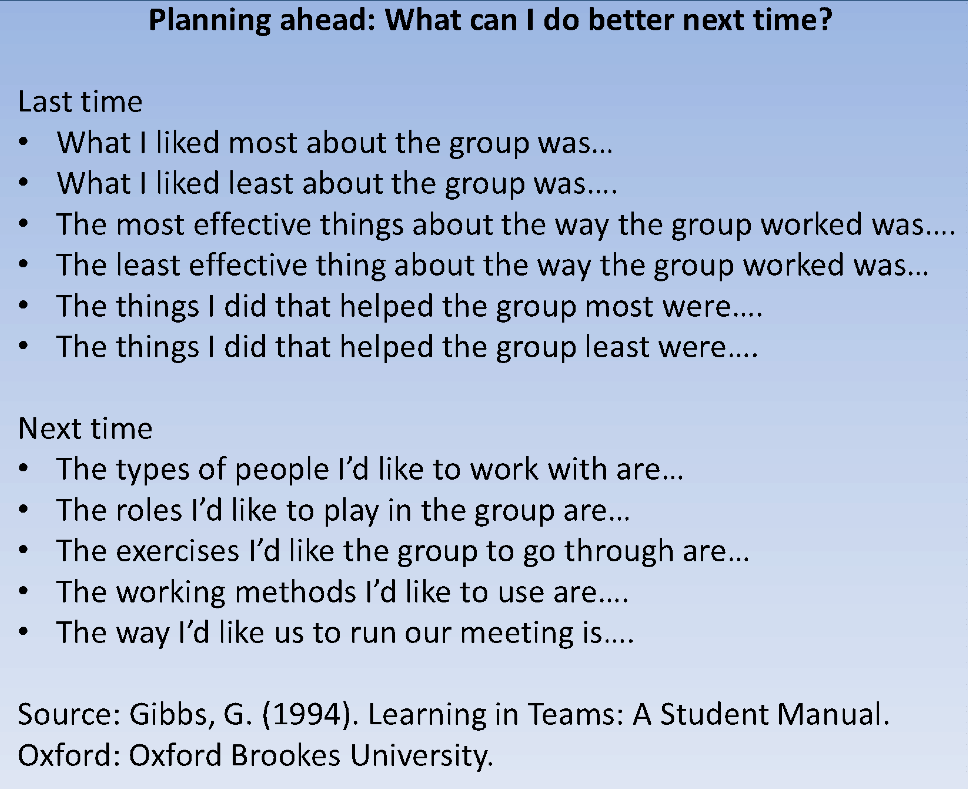

Step 6 is the most important step, and the one far too many students skip. For Step 6, you need to show how you not only reflected on what happened but also are able to use that reflection for personal growth into the future.

This is the heart and soul of your piece: here, you’re tying everything together and showing why reflection is so important!

This is the ‘action plan’ step in Gibbs’ cycle (you might want to cite Gibbs in this section!).

For Step 6, make some suggestions about how (based on your reflection) you now have some takeaway tips that you’ll bring forward to improve your group work skills next time. Here’s some ideas:

- Will you work harder next time to set deadlines in advance?

- Will you ensure you set clearer group roles next time to ensure the process runs more smoothly?

- Will you use a different type of technology (such as Google Docs) to ensure group communication goes more smoothly?

- Will you make sure you ask for help from your teacher earlier on in the process when you face challenges?

- Will you try harder to see things from everyone’s perspectives so there’s less conflict?

This step will be personalized based upon your own group work challenges and how you felt about the group work process. Even if you think your group worked really well together, I recommend you still come up with one or two ideas for continual improvement. Your teacher will want to see that you used reflection to strive for continual self-improvement.

Scholarly Source for Step 6

Step 7. edit.

Okay, you’ve got the nuts and bolts of the assessment put together now! Next, all you’ve got to do is write up the introduction and conclusion then edit the piece to make sure you keep growing your grades.

Here’s a few important suggestions for this last point:

- You should always write your introduction and conclusion last. They will be easier to write now that you’ve completed the main ‘body’ of the essay;

- Use my 5-step I.N.T.R.O method to write your introduction;

- Use my 5 C’s Conclusion method to write your conclusion;

- Use my 5 tips for editing an essay to edit it;

- Use the ProWritingAid app to get advice on how to improve your grammar and spelling. Make sure to also use the report on sentence length. It finds sentences that are too long and gives you advice on how to shorten them – such a good strategy for improving evaluative essay quality!

- Make sure you contact your teacher and ask for a one-to-one tutorial to go through the piece before submitting. This article only gives general advice, and you might need to make changes based upon the specific essay requirements that your teacher has provided.

That’s it! 7 steps to writing a quality group work reflection essay. I hope you found it useful. If you liked this post and want more clear and specific advice on writing great essays, I recommend signing up to my personal tutor mailing list.

Let’s sum up with those 7 steps one last time:

- Explain what ‘Reflection’ Is

- Explore the benefits of group work for learning

- Explore the challenges of group work for learning

- Explore the specific benefits and challenges your group faced

- Discuss how your group managed your challenges

- Conclude by exploring what you will do differently next time

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

2 thoughts on “How to write a Reflection on Group Work Essay”

Great instructions on writing a reflection essay. I would not change anything.

Thanks so much for your feedback! I really appreciate it. – Chris.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Collaborative and Group Writing

Introduction

When it comes to collaborative writing, people often have diametrically opposed ideas. Academics in the sciences often write multi-authored articles that depend on sharing their expertise. Many thrive on the social interaction that collaborative writing enables. Composition scholars Lisa Ede and Andrea Lunsford enjoyed co-authoring so much that they devoted their career to studying it. For others, however, collaborative writing evokes the memories of group projects gone wrong and inequitable work distribution.

Whatever your prior opinions about collaborative writing, we’re here to tell you that this style of composition may benefit your writing process and may help you produce writing that is cogent and compelling. At its best, collaborative writing can help to slow down the writing process, since it necessitates conversation, planning with group members, and more deliberate revising. A study described in Helen Dale’s “The Influence of Coauthoring on the Writing Process” shows that less experienced writers behave more like experts when they engage in collaborative writing. Students working on collaborative writing projects have said that their collaborative writing process involved more brainstorming, discussion, and diverse opinions from group members. Some even said that collaborative writing entailed less of an individual time commitment than solo papers.

Although collaborative writing implies that every part of a collaborative writing project involves working cooperatively with co-author(s), in practice collaborative writing often includes individual work. In what follows, we’ll walk you through the collaborative writing process, which we’ve divided into three parts: planning, drafting, and revising. As you consider how you’ll structure the writing process for your particular project, think about the expertise and disposition of your co-author(s), your project’s due date, the amount of time that you can devote to the project, and any other relevant factors. For more information about the various types of co-authorship systems you might employ, see “Strategies for Effective Collaborative Manuscript Development in Interdisciplinary Science Teams,” which outlines five different “author-management systems.”

The Collaborative Writing Process

Planning includes everything that is done before writing. In collaborative writing, this is a particularly important step since it’s crucial that all members of a team agree about the basic elements of the project and the logistics that will govern the project’s completion.Collaborative writing—by its very definition—requires more communication than individual work since almost all co-authored projects oblige participants to come to an agreement about what should be written and how to do this writing. And careful communication at the planning stage is usually critical to the creation of a strong collaborative paper. We would recommend assigning team members roles. Ensure that you know who will be initially drafting each section, who will be revising and editing these sections, who will be responsible for confirming that all team members complete their jobs, and who will be submitting the finished project.

Drafting refers to the process of actually writing the paper. We’ve called this part of the process drafting instead of writing to highlight the recursive nature of crafting a compelling paper since strong writing projects are often the product of several rounds of drafts. At this point in the writing process, you’ll need to make a choice: will you write together, individually, or in some combination of these two modes?

Individually

Revising is the final stage in the writing process. It will occur after a draft (either of a particular section or the entire paper) has been written. Revising, for most writing projects, will need to go beyond making line-edits that revise at the sentence-level. Instead, you’ll want to thoroughly consider all aspects of the draft in order to create a version of it that satisfies each member of the team. For more information about revision, check out our Writer’s Handbook page about revising longer papers .Even if your team has drafted the paper individually, we would recommend coming together to discuss revisions. Revising together and making choices about how to improve the draft—either online or in-person— is a good way to build consensus among group members since you’ll all need to agree on the changes you make.After you’ve discussed the revisions as a group, you’ll need to how you want to complete these revisions. Just like in the drafting stage above, you can choose to write together or individually.

Person A writes a section Person B gives suggestions for revision on this section Person A edits the section based on these suggestions

Person A writes a section The entire team meets and gives suggestions for revision on this section Person B edits the section based on these suggestions

Think through the strengths of your co-authoring team and choose a system that will work for your needs.

Suggestions for Efficient and Harmonious Collaborative Writing

Establish ground rules.

Although it can be tempting to jump right into your project—especially when you have limited time—establishing ground rules right from the beginning will help your group navigate the writing process. Conflicts and issues will inevitably arise in during the course of many long-term project. Knowing how you’ll navigate issues before they appear will help to smooth out these wrinkles. For example, you may also want to establish who will be responsible for checking in with authors if they don’t seem to be completing tasks assigned to them by their due dates. You may also want to decide how you will adjudicate disagreements. Will the majority rule? Do you want to hold out for full consensus? Establishing some ground rules will ensure that expectations are clear and that all members of the team are involved in the decision-making process.

Respect your co-author(s)

Everyone has their strengths. If you can recognize this, you’ll be able to harness your co-author(s) assets to write the best paper possible. It can be easy to write someone off if they’re not initially pulling their weight, but this type of attitude can be cancerous to a positive group mindset. Instead, check in with your co-author(s) and figure out how each one can best contribute to the group’s effort.

Be willing to argue

Arguing (respectfully!) with the other members of your writing group is a good thing because it means that you are expressing your deeply held beliefs with your co-author(s). While you don’t need to fight your team members about every feeling you have (after all, group work has to involve compromise!), if there are ideas that you feel strongly about—communicate them and encourage other members of your group to do the same even if they conflict with others’ viewpoints.

Schedule synchronous meetings

While you may be tempted to figure out group work purely by email, there’s really no substitute for talking through ideas with your co-author(s) face-to-face—even if you’re looking at your teammates face through the computer. At the beginning of your project, get a few synchronous meetings on the books in advance of your deadlines so that you can make sure that you’re able to have clear lines of communication throughout the writing process.

Use word processing software that enables collaboration

Sending lots of Word document drafts back-and-forth over email can get tiring and chaotic. Instead, we would recommend using word processing software that allows online collaboration. Right now, we like Google Docs for this since it’s free, easy to use, allows many authors to edit the same document, and has robust collaboration tools like chat and commenting.

Dale, Helen. “The Influence of Coauthoring on the Writing Process.” Journal of Teaching Writing , vol. 15, no. 1, 1996, pp. 65-79.

Lunsford, Andrea A., and Lisa Ede. Writing Together: Collaboration in Theory and Practice . Bedford St. Martin, 2011.

Oliver, Samantha K., et al. “Strategies for Effective Collaborative Manuscript Development in Interdisciplinary Science Teams.” Ecosphere , vol. 9, no. 4, Apr. 2018, pp. 1–13., doi:10.1002/ecs2.2206.

Writing Process and Structure

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Getting Started with Your Paper

Interpreting Writing Assignments from Your Courses

Generating Ideas for Your Paper

Creating an Argument

Thesis vs. Purpose Statements

Developing a Thesis Statement

Architecture of Arguments

Working with Sources

Quoting and Paraphrasing Sources

Using Literary Quotations

Citing Sources in Your Paper

Drafting Your Paper

Generating Ideas for Your Paper Introductions Paragraphing Developing Strategic Transitions Conclusions

Revising Your Paper

Peer Reviews

Reverse Outlines

Revising an Argumentative Paper

Revision Strategies for Longer Projects

Developing Strategic Transitions

Finishing your Paper

Twelve Common Errors: An Editing Checklist

How to Proofread your Paper

Writing Collaboratively

Essay on Group Work

Students are often asked to write an essay on Group Work in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Group Work

What is group work.

Group work is when two or more people work together to achieve a common goal. This can happen in many places, like school, work, or even at home. People in a group have to communicate, cooperate, and share their ideas and skills. This way, they can solve problems and complete tasks faster and better.

Benefits of Group Work

Working in a group has many benefits. It helps people learn from each other, build teamwork skills, and understand different viewpoints. It also divides the workload, making it easier for everyone. Group work can also help improve communication and social skills.

Challenges in Group Work

Despite the benefits, group work can also have challenges. Sometimes, people may not agree with each other, leading to conflicts. Some group members may not contribute equally, causing frustration. It’s important to address these issues to make group work effective.

Effective Group Work

To make group work effective, everyone should have a clear role and understand the goal. Good communication and respect for each other’s ideas are also important. Everyone should contribute equally and help each other. This way, the group can achieve its goal effectively and efficiently.

250 Words Essay on Group Work

Group work is when two or more people come together to do a task. It is like a team playing a game. Everyone has a role in the team, and they all work together to win the game. This is the same in group work. Everyone has a job to do, and they work together to finish the task.

Why is Group Work Important?

Group work is important for many reasons. First, it helps us learn from each other. We all have different skills and ideas. When we work in a group, we can share these skills and ideas. This helps us learn new things. Second, group work teaches us how to work with others. We learn how to listen, how to share, and how to solve problems together. These are important skills that we need in life.

Group work has many benefits. One benefit is that it can make a big task easier. If we have to do a big task by ourselves, it can be hard. But if we do it in a group, we can share the work. This makes the task easier and faster. Another benefit is that group work can help us make better decisions. When we make decisions in a group, we can hear many different ideas. This can help us make a better decision.

Challenges of Group Work

Group work also has some challenges. Sometimes, people in the group may not agree. This can cause problems. But if we learn how to listen and respect each other, we can solve these problems.

In conclusion, group work is a good way to learn and work. It has many benefits and can help us in many ways. But like all things, it also has challenges. We need to learn how to work in a group to make the most of it.

500 Words Essay on Group Work

The importance of group work.

Group work is important for many reasons. First, it helps us to learn how to work with others. This is a skill that is very useful in real life, especially in jobs where teamwork is important. Second, group work can make difficult tasks easier. When we work in a group, we can share the workload and help each other. Third, group work can help us to learn new things. By working with others, we can learn from their experiences and knowledge.

There are many benefits of group work. One of the main benefits is that it can improve our problem-solving skills. When we work in a group, we need to solve problems together. This can help us to think in new ways and come up with creative solutions.

Finally, group work can also help us to develop our leadership skills. In a group, we often need to take turns leading the team. This can help us to learn how to lead others and make important decisions.

While group work has many benefits, it can also have some challenges. One of the main challenges is that it can sometimes be difficult to work with others. People have different ideas and ways of doing things, which can lead to disagreements.

In conclusion, group work is a very useful tool that can help us to learn new skills, solve problems, and work more efficiently. While it can have some challenges, the benefits of group work often outweigh the difficulties. By working together in a group, we can achieve more than we could on our own.

In the end, group work is not just about getting the job done. It’s also about learning to work with others, developing new skills, and growing as individuals. And these are things that can help us in many different areas of our lives.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Group Work That Works

Educators weigh in on solutions to the common pitfalls of group work.

Your content has been saved!

Mention group work and you’re confronted with pointed questions and criticisms. The big problems, according to our audience: One or two students do all the work; it can be hard on introverts; and grading the group isn’t fair to the individuals.

But the research suggests that a certain amount of group work is beneficial.

“The most effective creative process alternates between time in groups, collaboration, interaction, and conversation... [and] times of solitude, where something different happens cognitively in your brain,” says Dr. Keith Sawyer, a researcher on creativity and collaboration, and author of Group Genius: The Creative Power of Collaboration .

So we looked through our archives and reached out to educators on Facebook to find out what solutions they’ve come up with for these common problems.

Making Sure Everyone Participates

“How many times have we put students in groups only to watch them interact with their laptops instead of each other? Or complain about a lazy teammate?” asks Mary Burns, a former French, Latin, and English middle and high school teacher who now offers professional development in technology integration.

Unequal participation is perhaps the most common complaint about group work. Still, a review of Edutopia’s archives—and the tens of thousands of insights we receive in comments and reactions to our articles—revealed a handful of practices that educators use to promote equal participation. These involve setting out clear expectations for group work, increasing accountability among participants, and nurturing a productive group work dynamic.

Norms: At Aptos Middle School in San Francisco, the first step for group work is establishing group norms. Taji Allen-Sanchez, a sixth- and seventh-grade science teacher, lists expectations on the whiteboard, such as “everyone contributes” and “help others do things for themselves.”

For ambitious projects, Mikel Grady Jones, a high school math teacher in Houston, takes it a step further, asking her students to sign a group contract in which they agree on how they’ll divide the tasks and on expectations like “we all promise to do our work on time.” Heather Wolpert-Gawron, an English middle school teacher in Los Angeles, suggests creating a classroom contract with your students at the start of the year, so that agreed-upon norms can be referenced each time a new group activity begins.

Group size: It’s a simple fix, but the size of the groups can help establish the right dynamics. Generally, smaller groups are better because students can’t get away with hiding while the work is completed by others.

“When there is less room to hide, nonparticipation is more difficult,” says Burns. She recommends groups of four to five students, while Brande Tucker Arthur, a 10th-grade biology teacher in Lynchburg, Virginia, recommends even smaller groups of two or three students.

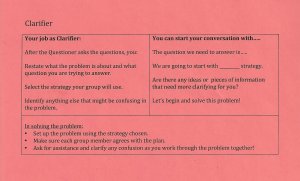

Meaningful roles: Roles can play an important part in keeping students accountable, but not all roles are helpful. A role like materials manager, for example, won’t actively engage a student in contributing to a group problem; the roles must be both meaningful and interdependent.

At University Park Campus School , a grade 7–12 school in Worcester, Massachusetts, students take on highly interdependent roles like summarizer, questioner, and clarifier. In an ongoing project, the questioner asks probing questions about the problem and suggests a few ideas on how to solve it, while the clarifier attempts to clear up any confusion, restates the problem, and selects a possible strategy the group will use as they move forward.

At Design 39, a K–8 school in San Diego, groups and roles are assigned randomly using Random Team Generator , but ClassDojo , Team Shake , and drawing students’ names from a container can also do the trick. In a practice called vertical learning, Design 39 students conduct group work publicly, writing out their thought processes on whiteboards to facilitate group feedback. The combination of randomizing teams and public sharing exposes students to a range of problem-solving approaches, gets them more comfortable with making mistakes, promotes teamwork, and allows kids to utilize different skill sets during each project.

Rich tasks: Making sure that a project is challenging and compelling is critical. A rich task is a problem that has multiple pathways to the solution and that one person would have difficulty solving on their own.

In an eighth-grade math class at Design 39, one recent rich task explored the concept of how monetary investments grow: Groups were tasked with solving exponential growth problems using simple and compound interest rates.

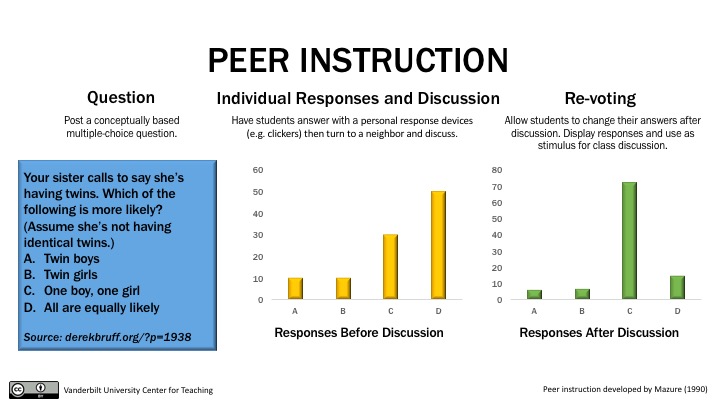

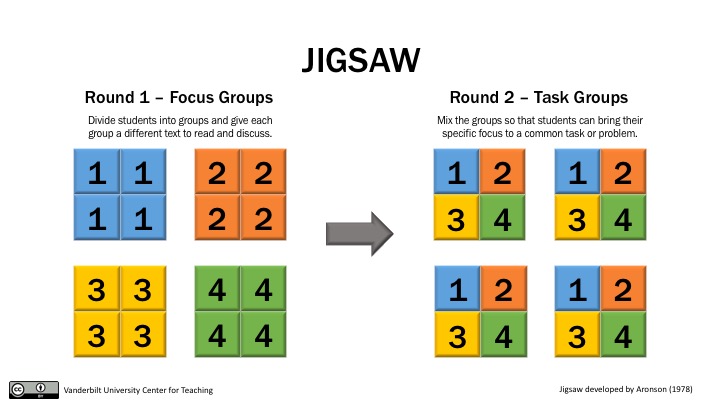

Rich tasks are not just for math class. When Dan St. Louis, the principal of University Park, was a teacher, he asked his English students to come up with a group definition of the word Orwellian . They did this through the jigsaw method, a type of grouping strategy that John Hattie’s study Visible Learning ranked as highly effective.

“Five groups of five students might each read a different news article about the modern world,” says St. Louis. “Then each student would join a new group of five where they need to explain their previous group’s article to each other and make connections to each. Using these connections, the group must then construct a definition of the word Orwellian .” For another example of the jigsaw approach, see this video from Cult of Pedagogy.

Supporting Introverts

Teachers worry about the impact of group work on introverts. Some of our educators suggest that giving introverts choice in who they’re grouped with can help them feel more comfortable.

“Even the quietest students are usually comfortable and confident when they are with peers with whom they connect,” says Shelly Kunkle, a veteran teacher at Wasawee Middle School in North Webster, Indiana. Wolpert-Gawron asks her students to list four peers they want to work with and then makes sure to pair them with one from their list.

Having defined roles within groups—like clarifier or questioner—also provides structure for students who may be less comfortable within complex social dynamics, and ensures that introverts don’t get overshadowed by their more extroverted peers.

Finally, be mindful that introverted students often simply need time to recharge. “Many introverts do not mind and even enjoy interacting in groups as long as they get some quiet time and solitude to recharge. It’s not about being shy or feeling unsafe in a large group,” says Barb Larochelle, a recently retired high school English teacher in Edmonton, Alberta, who taught for 29 years.

“I planned classes with some time to work quietly alone, some time to interact in smaller groups or as a whole class, and some time to get up and move around a little. A whole class of any one of those is going to be hard on one group, but a balance works well.”

Assessing Group Work

Grading group work is problematic. Often, you don’t have a clear understanding of what each student knows, and a single student’s lack of effort can torpedo the group grade. To some degree, strategies that assign meaningful roles or that require public presentations from groups provide a window in to each student’s knowledge and contributions.

But not all classwork needs to be graded. Suzanna Kruger, a high school science teacher in Seaside, Oregon, doesn’t grade group work—there are plenty of individual assignments that receive grades, and plenty of other opportunities for formative assessment.

John McCarthy, a former high school English and social studies teacher and current education consultant and adjunct professor at Madonna University for the graduate department for education, suggests using group presentations or group products as a non-graded review for a test. But if you want to grade group work, he recommends making all academic assessments within group work individual assessments. For example, instead of grading a group presentation, McCarthy grades each student on an essay, which the students then use to create their group presentation.

Laura Moffit, a fifth-grade teacher in Wilmington, North Carolina, uses self and peer evaluations to shed light on how each student is contributing to group work—starting with a lesson on how to do an objective evaluation. “Just have students circle :), :|, or :( on three to five statements about each partner, anonymously,” Moffit commented on Facebook. “Then give the evaluations back to each group member. Finding out what people really think of your performance is a wake-up call.”

And Ted Malefyt, a middle school science teacher in Hamilton, Michigan, carries a clipboard with the class list formatted in a spreadsheet and walks around checking in on students while they do group work.

“Using this spreadsheet, you have your own record of which student is meeting your expectations and who needs extra help,” explains Malefyt. “As formative assessment takes place, quickly document with simple checkmarks.”

- Request a Consultation

- Workshops and Virtual Conversations

- Technical Support

- Course Design and Preparation

- Observation & Feedback

Teaching Resources

Benefits of Group Work

Resource overview.

Why using group work in your class can improve student learning

There are several benefits for including group work in your class. Sharing these benefits with your students in a transparent manner helps them understand how group work can improve learning and prepare them for life experiences (Taylor 2011). The benefits of group work include the following:

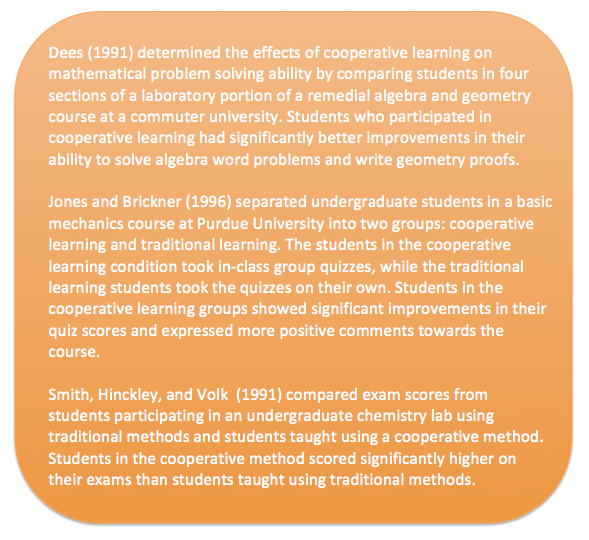

- Students engaged in group work, or cooperative learning, show increased individual achievement compared to students working alone. For example, in their meta-analysis examining over 168 studies of undergraduate students, Johnson et al. (2014) determined that students learning in a collaborative situation had greater knowledge acquisition, retention of material, and higher-order problem solving and reasoning abilities than students working alone. There are several reasons for this difference. Students’ interactions and discussions with others allow the group to construct new knowledge, place it within a conceptual framework of existing knowledge, and then refine and assess what they know and do not know. This group dialogue helps them make sense of what they are learning and what they still need to understand or learn (Ambrose et al. 2010; Eberlein et al. 2008). In addition, groups can tackle more complex problems than individuals can and thus have the potential to gain more expertise and become more engaged in a discipline (Qin et al 1995; Kuh 2007). Group work creates more opportunities for critical thinking and can promote student learning and achievement.

- Student group work enhances communication and other professional development skills. Estimates indicate that 80% of all employees work in group settings (Attle & Baker 2007). Therefore, employers value effective oral and written communication skills as well as the ability to work effectively within diverse groups (ABET 2016-2017; Finelli et al. 2011). Creating facilitated opportunities for group work in your class allows students to enhance their skills in working effectively with others (Bennett & Gadlin 2012; Jackson et al. 2014). Group work gives students the opportunity to engage in process skills critical for processing information, and evaluating and solving problems, as well as management skills through the use of roles within groups, and assessment skills involved in assessing options to make decisions about their group’s final answer. All of these skills are critical to successful teamwork both in the classroom and the workplace.

Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology, Inc. Criteria for accrediting Engineering Programs (ABET), 2016-2017 http://www.abet.org/accreditation/accreditation-criteria/criteria-for-accrediting-engineering-programs-2016-2017/

Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., Lovett, M. C., DiPietro, M., & Norman, M. K. (2010). How learning works: 7 research-based principles for smart teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Attle, S., & Baker, B. 2007 Cooperative learning in a competitive environment: Classroom applications. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education , 19 (1), 77-83.

Bennett, L. M., & Gadlin, H. (2012). Collaboration and team science. Journal of Investigative Medicine , 60 (5), 768-775.

Davidson, N., & Major, C. H. (2014). Boundary crossings: Cooperative learning, collaborative learning, and problem-based learning. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching , 25 (3/4), 7-55.

Eberlein, T., Kampmeier, J., Minderhout, V., Moog, R. S., Platt, T., Varma‐Nelson, P., & White, H. B. (2008). Pedagogies of engagement in science. Biochemistry and molecular biology education , 36 (4), 262-273.

Finelli, C. J., Bergom, I., & Mesa, V. (2011). Student teams in the engineering classroom and beyond: Setting up students for success. CRLT Occasional Papers , 29 .

Jackson, D., Sibson, R., & Riebe, L. (2014). Undergraduate perceptions of the development of team-working skills. Education+ Training , 56 (1), 7-20.

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Smith, K. A. (2014). Cooperative learning: Improving university instruction by basing practice on validated theory. Journal on Excellence in University Teaching , 25 (4), 1-26.

Kuh, G. D., Kinzie, J., Buckley, J. A., Bridges, B. K., & Hayek, J. C. (2007). Piecing Together the Student Success Puzzle: Research, Propositions, and Recommendations. ASHE Higher Education Report, Volume 32, Number 5. ASHE Higher Education Report , 32 (5), 1-182.

Qin, Z., Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (1995). Cooperative versus competitive efforts and problem solving. Review of educational Research, 65 (2), 129-143.

Taylor, A. (2011). Top 10 reasons students dislike working in small groups… and why I do it anyway. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education , 39 (3), 219-220.

the encyclopaedia of pedagogy and informal education

What is group work?

What is group work while many practitioners may describe what they do as ‘group work’, they often have only a limited appreciation of what group work is and what it entails. in this piece we introduce groups and group work, define some key aspects, and suggest areas for exploration. in particular we focus on the process of working with groups..

Contents : introduction • what is a group? • working with • working with groups – a definition • three foci • exploring the theory and practice of group work • conclusion • further reading and references • how to cite this article

For some group work is just another way of talking about teamwork. In this context, working in groups is often presented as a good way of dividing work and increasing productivity. It can also be argued that it allows for the utilization of the different skills, knowledge and experiences that people have. As a result, in schools and colleges it is often approached as a skill to be learnt – the ability to work in group-based environments. Within schools and colleges, working in groups can also be adopted as a mean of carrying forward curriculum concerns and varying the classroom experience – a useful addition to the teacher or instructor’s repertoire.

In this article our focus is different. We explore the process of working with groups both so that they may undertake particular tasks and become environments where people can share in a common life, form beneficial relationships and help each other. Entering groups or forming them, and then working with them so that members are able be around each other, take responsibility and work together on shared tasks, involves some very sophisticated abilities on the part of practitioners. These abilities are often not recognized for what they are – for when group work is done well it can seem natural. Skilled group workers, like skilled counsellors, have to be able to draw upon an extensive repertoire of understandings, experiences and skills and be able to think on their feet. They have to respond both quickly and sensitively to what is emerging in the exchanges and relationships in the groups they are working with.

Our starting point for this is a brief exploration of the nature of groups. We then turn to the process of working with. We also try to define group work – and discuss some of foci that workers need to attend to. We finish with an overview of the development of group work as a focus for theory-making and exploration.

What is a group?

In a separate article we discuss the nature of groups and their significance for human societies (see What is a group? ). Here I just want to highlight five main points.

First, while there are some very different ways of defining groups – often depending upon which aspect of them that commentators and researchers want to focus upon – it is worthwhile looking to a definition that takes things back to basics. Here, as a starting point, we are using Donelson R. Forsyth’s definition of a group as ‘ two or more individuals who are connected to one another by social relationships ’ [emphasis in original] (2006: 2-3). This definition has the merit of bringing together three elements: the number of individuals involved, connection, and relationship.

Second, groups are a fundamental part of human experience. They allow people to develop more complex and larger-scale activities; are significant sites of socialization and education; and provide settings where relationships can form and grow, and where people can find help and support.

Humans are small group beings. We always have been and we always will be. The ubiquitousness of groups and the inevitability of being in them makes groups one of the most important factors in our lives. As the effectiveness of our groups goes, so goes the quality of our lives. (Johnson and Johnson 2003: 579)

However, there is a downside to all this. The socialization they offer, for example, might be highly constraining and oppressive for some of their members. Given all of this it is easy to see why the intervention of skilled leaders and facilitators is sometimes necessary.

Third, the social relationships involved in groups entail interdependence. As Kurt Lewin wrote, ‘it is not similarity or dissimilarity of individuals that constitutes a group, but interdependence of fate’ (op. cit.: 165). In other words, groups come about in a psychological sense because people realize they are ‘in the same boat’ (Brown 1988: 28). However, even more significant than this for group process, Lewin argued, is some interdependence in the goals of group members. To get something done it is often necessary to cooperate with others.

Fourth, when considering the activities of informal educators and other workers and animateurs operating in local communities it is helpful to consider whether the groups they engage with are planned or emergent. Planned groups are specifically formed for some purpose – either by their members, or by some external individual, group or organization. Emergent groups come into being relatively spontaneously where people find themselves together in the same place, or where the same collection of people gradually come to know each other through conversation and interaction over a period of time. (Cartwright and Zander 1968). Much of the recent literature of group work is concerned with groups formed by the worker or agency. Relatively little has been written over the last decade or so about working with emergent groups or groups formed by their members. As a result some significant dimensions of experience have been left rather unexplored.

Last, considerable insights can be gained into the process and functioning of groups via the literature of group dynamics and of small groups. Of particular help are explorations of group structure (including the group size and the roles people play), group norms and culture, group goals, and the relative cohesiveness of groups (all discussed in What is a group? ). That said, the skills needed for engaging in and with group life – and the attitudes, orientations and ideas associated with them – are learnt, predominantly, through experiencing group life. This provides a powerful rationale for educative interventions.

Working with

Educators and animateurs often have to ‘be around’ for a time in many settings before we are approached or accepted:

It may seem obvious, but for others to meet us as helpers, we have to be available. People must know who we are and where we are to be found. They also need to know what we may be able to offer. They also must feel able to approach us (or be open to our initiating contact). (Smith and Smith 2008: 17)

Whether we are working with groups that we have formed, or are seeking to enter groups, to function as workers we need to be recognized as workers. In other words, the people in the situation need to give us space to engage with them around some experience, issue or task. Both workers and participants need to acknowledge that something called ‘work’ is going on.

The ‘work’ in ‘group work’ is a form of ‘working with’. We are directing our energies in a particular way. This is based in an understanding that people are not machines or objects that can be worked on like motor cars (Jeffs and Smith 2005: 70). We are spending time in the company of others. They have allowed us into their lives – and there is a social, emotional and moral relationship between us. As such, ‘working with’ is a special form of ‘being with’.

To engage with another’s thoughts and feelings, and to attend to our own, we have to be in a certain frame of mind. We have to be open to what is being said, to listen for meaning. To work with others is, in essence, to engage in a conversation with them. We should not seek to act on the other person but join with them in a search for understanding and possibility. (Smith and Smith 2008: 20)

Not surprisingly all this, when combined with the sorts of questions and issues that we have to engage with, the process of working with another can often be ‘a confusing, complex and demanding experience, both mentally and emotionally’ (Crosby 2001: 60).

In the conversations of informal and community educators the notion of ’working with’ is often reserved for describing more formal encounters where there is an explicit effort to help people attend to feelings, reflect on experiences, think about things, and make plans (Smith 1994: 95). It can involve putting aside a special time and agreeing a place to talk things through. Often, though, it entails creating a moment for reflection and exploration then and there (Smith and Smith 2008:20).

As Kerry Young (2006) has argued, ‘Working with’ can also be seen as an exercise in moral philosophy. Often people seeking to answer in some way deep questions about themselves and the situations they face. At root these look to how people should live their lives: ‘what is the right way to act in this situation or that; of what does happiness consist for me and for others; how should I to relate to others; what sort of society should I be working for?’ (Smith and Smith 2008: 20). This inevitably entails us as workers to be asking the same questions of ourselves. There needs to be, as Gisela Konopka (1963) has argued, certain values running through the way we engage with others. In relation to social group work, she looked three ‘humanistic’ concerns. That:

- individuals are of inherent worth.

- people are mutually responsible for each other; and