- Research Skills

50 Mini-Lessons For Teaching Students Research Skills

Please note, I am no longer blogging and this post hasn’t updated since April 2020.

For a number of years, Seth Godin has been talking about the need to “ connect the dots” rather than “collect the dots” . That is, rather than memorising information, students must be able to learn how to solve new problems, see patterns, and combine multiple perspectives.

Solid research skills underpin this. Having the fluency to find and use information successfully is an essential skill for life and work.

Today’s students have more information at their fingertips than ever before and this means the role of the teacher as a guide is more important than ever.

You might be wondering how you can fit teaching research skills into a busy curriculum? There aren’t enough hours in the day! The good news is, there are so many mini-lessons you can do to build students’ skills over time.

This post outlines 50 ideas for activities that could be done in just a few minutes (or stretched out to a longer lesson if you have the time!).

Learn More About The Research Process

I have a popular post called Teach Students How To Research Online In 5 Steps. It outlines a five-step approach to break down the research process into manageable chunks.

This post shares ideas for mini-lessons that could be carried out in the classroom throughout the year to help build students’ skills in the five areas of: clarify, search, delve, evaluate , and cite . It also includes ideas for learning about staying organised throughout the research process.

Notes about the 50 research activities:

- These ideas can be adapted for different age groups from middle primary/elementary to senior high school.

- Many of these ideas can be repeated throughout the year.

- Depending on the age of your students, you can decide whether the activity will be more teacher or student led. Some activities suggest coming up with a list of words, questions, or phrases. Teachers of younger students could generate these themselves.

- Depending on how much time you have, many of the activities can be either quickly modelled by the teacher, or extended to an hour-long lesson.

- Some of the activities could fit into more than one category.

- Looking for simple articles for younger students for some of the activities? Try DOGO News or Time for Kids . Newsela is also a great resource but you do need to sign up for free account.

- Why not try a few activities in a staff meeting? Everyone can always brush up on their own research skills!

- Choose a topic (e.g. koalas, basketball, Mount Everest) . Write as many questions as you can think of relating to that topic.

- Make a mindmap of a topic you’re currently learning about. This could be either on paper or using an online tool like Bubbl.us .

- Read a short book or article. Make a list of 5 words from the text that you don’t totally understand. Look up the meaning of the words in a dictionary (online or paper).

- Look at a printed or digital copy of a short article with the title removed. Come up with as many different titles as possible that would fit the article.

- Come up with a list of 5 different questions you could type into Google (e.g. Which country in Asia has the largest population?) Circle the keywords in each question.

- Write down 10 words to describe a person, place, or topic. Come up with synonyms for these words using a tool like Thesaurus.com .

- Write pairs of synonyms on post-it notes (this could be done by the teacher or students). Each student in the class has one post-it note and walks around the classroom to find the person with the synonym to their word.

- Explore how to search Google using your voice (i.e. click/tap on the microphone in the Google search box or on your phone/tablet keyboard) . List the pros and cons of using voice and text to search.

- Open two different search engines in your browser such as Google and Bing. Type in a query and compare the results. Do all search engines work exactly the same?

- Have students work in pairs to try out a different search engine (there are 11 listed here ). Report back to the class on the pros and cons.

- Think of something you’re curious about, (e.g. What endangered animals live in the Amazon Rainforest?). Open Google in two tabs. In one search, type in one or two keywords ( e.g. Amazon Rainforest) . In the other search type in multiple relevant keywords (e.g. endangered animals Amazon rainforest). Compare the results. Discuss the importance of being specific.

- Similar to above, try two different searches where one phrase is in quotation marks and the other is not. For example, Origin of “raining cats and dogs” and Origin of raining cats and dogs . Discuss the difference that using quotation marks makes (It tells Google to search for the precise keywords in order.)

- Try writing a question in Google with a few minor spelling mistakes. What happens? What happens if you add or leave out punctuation ?

- Try the AGoogleADay.com daily search challenges from Google. The questions help older students learn about choosing keywords, deconstructing questions, and altering keywords.

- Explore how Google uses autocomplete to suggest searches quickly. Try it out by typing in various queries (e.g. How to draw… or What is the tallest…). Discuss how these suggestions come about, how to use them, and whether they’re usually helpful.

- Watch this video from Code.org to learn more about how search works .

- Take a look at 20 Instant Google Searches your Students Need to Know by Eric Curts to learn about “ instant searches ”. Try one to try out. Perhaps each student could be assigned one to try and share with the class.

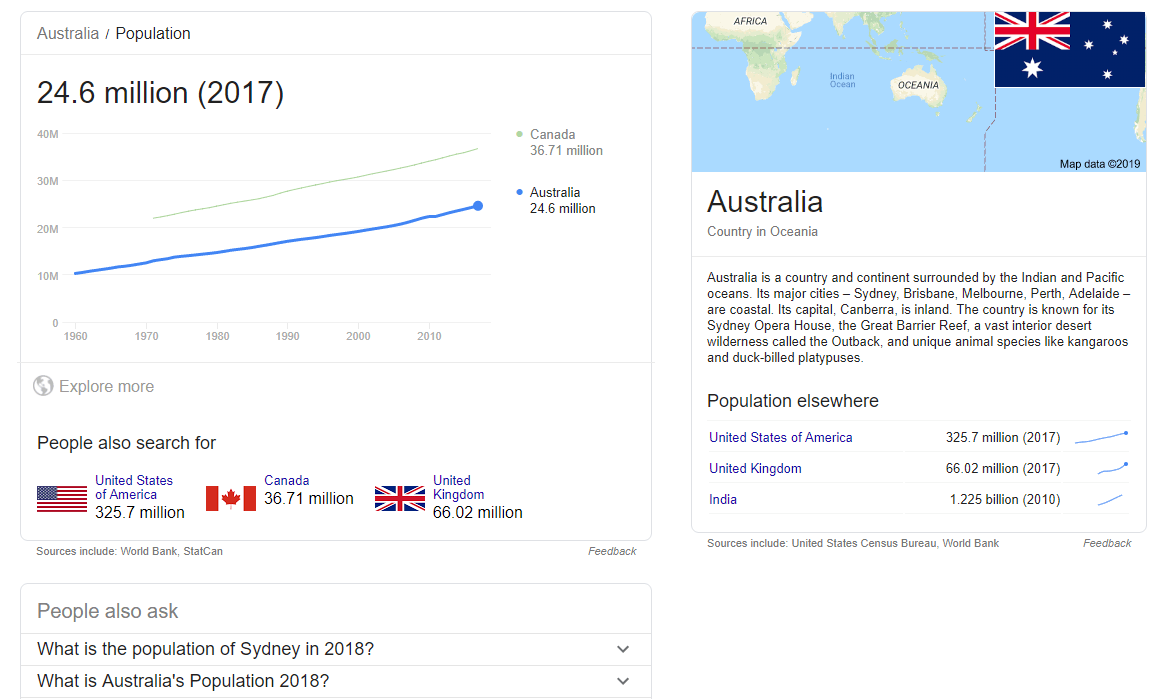

- Experiment with typing some questions into Google that have a clear answer (e.g. “What is a parallelogram?” or “What is the highest mountain in the world?” or “What is the population of Australia?”). Look at the different ways the answers are displayed instantly within the search results — dictionary definitions, image cards, graphs etc.

- Watch the video How Does Google Know Everything About Me? by Scientific American. Discuss the PageRank algorithm and how Google uses your data to customise search results.

- Brainstorm a list of popular domains (e.g. .com, .com.au, or your country’s domain) . Discuss if any domains might be more reliable than others and why (e.g. .gov or .edu) .

- Discuss (or research) ways to open Google search results in a new tab to save your original search results (i.e. right-click > open link in new tab or press control/command and click the link).

- Try out a few Google searches (perhaps start with things like “car service” “cat food” or “fresh flowers”). A re there advertisements within the results? Discuss where these appear and how to spot them.

- Look at ways to filter search results by using the tabs at the top of the page in Google (i.e. news, images, shopping, maps, videos etc.). Do the same filters appear for all Google searches? Try out a few different searches and see.

- Type a question into Google and look for the “People also ask” and “Searches related to…” sections. Discuss how these could be useful. When should you use them or ignore them so you don’t go off on an irrelevant tangent? Is the information in the drop-down section under “People also ask” always the best?

- Often, more current search results are more useful. Click on “tools” under the Google search box and then “any time” and your time frame of choice such as “Past month” or “Past year”.

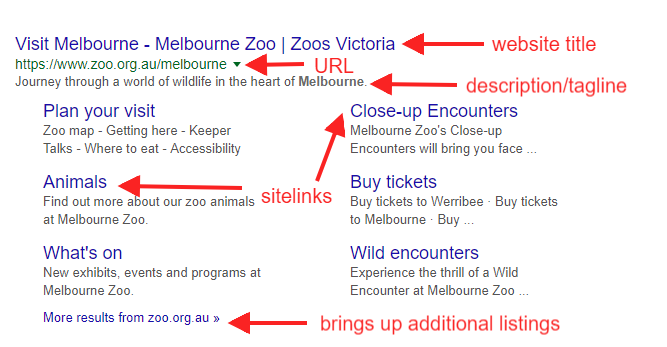

- Have students annotate their own “anatomy of a search result” example like the one I made below. Explore the different ways search results display; some have more details like sitelinks and some do not.

- Find two articles on a news topic from different publications. Or find a news article and an opinion piece on the same topic. Make a Venn diagram comparing the similarities and differences.

- Choose a graph, map, or chart from The New York Times’ What’s Going On In This Graph series . Have a whole class or small group discussion about the data.

- Look at images stripped of their captions on What’s Going On In This Picture? by The New York Times. Discuss the images in pairs or small groups. What can you tell?

- Explore a website together as a class or in pairs — perhaps a news website. Identify all the advertisements .

- Have a look at a fake website either as a whole class or in pairs/small groups. See if students can spot that these sites are not real. Discuss the fact that you can’t believe everything that’s online. Get started with these four examples of fake websites from Eric Curts.

- Give students a copy of my website evaluation flowchart to analyse and then discuss as a class. Read more about the flowchart in this post.

- As a class, look at a prompt from Mike Caulfield’s Four Moves . Either together or in small groups, have students fact check the prompts on the site. This resource explains more about the fact checking process. Note: some of these prompts are not suitable for younger students.

- Practice skim reading — give students one minute to read a short article. Ask them to discuss what stood out to them. Headings? Bold words? Quotes? Then give students ten minutes to read the same article and discuss deep reading.

All students can benefit from learning about plagiarism, copyright, how to write information in their own words, and how to acknowledge the source. However, the formality of this process will depend on your students’ age and your curriculum guidelines.

- Watch the video Citation for Beginners for an introduction to citation. Discuss the key points to remember.

- Look up the definition of plagiarism using a variety of sources (dictionary, video, Wikipedia etc.). Create a definition as a class.

- Find an interesting video on YouTube (perhaps a “life hack” video) and write a brief summary in your own words.

- Have students pair up and tell each other about their weekend. Then have the listener try to verbalise or write their friend’s recount in their own words. Discuss how accurate this was.

- Read the class a copy of a well known fairy tale. Have them write a short summary in their own words. Compare the versions that different students come up with.

- Try out MyBib — a handy free online tool without ads that helps you create citations quickly and easily.

- Give primary/elementary students a copy of Kathy Schrock’s Guide to Citation that matches their grade level (the guide covers grades 1 to 6). Choose one form of citation and create some examples as a class (e.g. a website or a book).

- Make a list of things that are okay and not okay to do when researching, e.g. copy text from a website, use any image from Google images, paraphrase in your own words and cite your source, add a short quote and cite the source.

- Have students read a short article and then come up with a summary that would be considered plagiarism and one that would not be considered plagiarism. These could be shared with the class and the students asked to decide which one shows an example of plagiarism .

- Older students could investigate the difference between paraphrasing and summarising . They could create a Venn diagram that compares the two.

- Write a list of statements on the board that might be true or false ( e.g. The 1956 Olympics were held in Melbourne, Australia. The rhinoceros is the largest land animal in the world. The current marathon world record is 2 hours, 7 minutes). Have students research these statements and decide whether they’re true or false by sharing their citations.

Staying Organised

- Make a list of different ways you can take notes while researching — Google Docs, Google Keep, pen and paper etc. Discuss the pros and cons of each method.

- Learn the keyboard shortcuts to help manage tabs (e.g. open new tab, reopen closed tab, go to next tab etc.). Perhaps students could all try out the shortcuts and share their favourite one with the class.

- Find a collection of resources on a topic and add them to a Wakelet .

- Listen to a short podcast or watch a brief video on a certain topic and sketchnote ideas. Sylvia Duckworth has some great tips about live sketchnoting

- Learn how to use split screen to have one window open with your research, and another open with your notes (e.g. a Google spreadsheet, Google Doc, Microsoft Word or OneNote etc.) .

All teachers know it’s important to teach students to research well. Investing time in this process will also pay off throughout the year and the years to come. Students will be able to focus on analysing and synthesizing information, rather than the mechanics of the research process.

By trying out as many of these mini-lessons as possible throughout the year, you’ll be really helping your students to thrive in all areas of school, work, and life.

Also remember to model your own searches explicitly during class time. Talk out loud as you look things up and ask students for input. Learning together is the way to go!

You Might Also Enjoy Reading:

How To Evaluate Websites: A Guide For Teachers And Students

Five Tips for Teaching Students How to Research and Filter Information

Typing Tips: The How and Why of Teaching Students Keyboarding Skills

8 Ways Teachers And Schools Can Communicate With Parents

10 Replies to “50 Mini-Lessons For Teaching Students Research Skills”

Loving these ideas, thank you

This list is amazing. Thank you so much!

So glad it’s helpful, Alex! 🙂

Hi I am a student who really needed some help on how to reasearch thanks for the help.

So glad it helped! 🙂

seriously seriously grateful for your post. 🙂

So glad it’s helpful! Makes my day 🙂

How do you get the 50 mini lessons. I got the free one but am interested in the full version.

Hi Tracey, The link to the PDF with the 50 mini lessons is in the post. Here it is . Check out this post if you need more advice on teaching students how to research online. Hope that helps! Kathleen

Best wishes to you as you face your health battler. Hoping you’ve come out stronger and healthier from it. Your website is so helpful.

Comments are closed.

Teaching at NYU Libraries

- 1. Orientation to the Instruction Program

- 2. Our Pedagogical Values & Frameworks

- 3. Practicalities & How-To's

- Support Provided by UIS

- Lesson Plans

Sample Lesson Plans

Tours and workshops, foundational classes, subject-specific classes.

- Learning Objects

- Asynchronous Library Modules

Feel free to make a copy any of the sample lesson plans linked to below, to use as is or adapt for your own purposes.

Do you have a lesson plan to share? This collection is meant to be a continually evolving resource and we welcome your contributions. Send your lesson plan to UIS at [email protected] and we'll upload it into this page.

NYU Libraries offers tours and workshops during NYU Welcome, as well as other times throughout the year. Individual students can find out about and sign up for these tours and workshops at library.nyu.edu/classes .

Folder of tour outlines and workshop lesson plans , containing:

- Tours of Bobst Library

- Research 101

- Research 201

- Intro to RefWorks

These classes are requested by course instructors and taught by members of the Libraries Core Instruction Team (i.e. UIS librarians and TLE associates).

First Year Experience

- Cohort Program (CAS)

- New Student Seminar (Steinhardt)

- New Student Seminar for International Graduate Students (Steinhardt)

- First Year Colloquium (HEOP)

First Year Writing

Cas - administered by the expository writing program (ewp).

- First semester course: Writing the Essay

- Second semester course : none

- Resources: Course progressions and BEAM method

GALLATIN - Administered by Gallatin

- Sample lesson plan for FYWS

- Sample lesson plan for FYRS

LIBERAL STUDIES - Administered by Liberal Studies

- Sample lesson plan for Writing as Exploration

- Sample lesson plan for Writing as Critical Inquiry

NURSING - Administered by EWP

- See CAS for sample lesson plan

SILVER - Administered by EWP

Sps - administered by sps.

- Sample lesson plan for Writing Workshop I

- Sample lesson plan for Writing Workshop II

STEINHARDT - Administered by EWP

- Sample lesson plan for ACE: Education

TANDON - Administered by EWP

- Sample lesson plan for ACE

TISCH - Administered by EWP

- Sample lesson plan for WTE: Art

- Sample lesson plan for ACE: Art

Caribbean Cultures (Global Cultures, Global Liberal Studies)

- << Previous: Support Provided by UIS

- Next: Learning Objects >>

- Last Updated: Jan 23, 2024 12:18 PM

- URL: https://guides.nyu.edu/teaching-at-nyu-libs

Think Like a Researcher: Instruction Resources: #6 Developing Successful Research Questions

- Guide Organization

- Overall Summary

- #1 Think Like a Researcher!

- #2 How to Read a Scholarly Article

- #3 Reading for Keywords (CREDO)

- #4 Using Google for Academic Research

- #4 Using Google for Academic Research (Alternate)

- #5 Integrating Sources

- Research Question Discussion

- #7 Avoiding Researcher Bias

- #8 Understanding the Information Cycle

- #9 Exploring Databases

- #10 Library Session

- #11 Post Library Session Activities

- Summary - Readings

- Summary - Research Journal Prompts

- Summary - Key Assignments

- Jigsaw Readings

- Permission Form

Course Learning Outcome: Develop ability to synthesize and express complex ideas; demonstrate information literacy and be able to work with evidence

Goal: Develop students’ ability to recognize and create successful research questions

Specifically, students will be able to

- identify the components of a successful research question.

- create a viable research question.

What Makes a Good Research Topic Handout

These handouts are intended to be used as a discussion generator that will help students develop a solid research topic or question. Many students start with topics that are poorly articulated, too broad, unarguable, or are socially insignificant. Each of these problems may result in a topic that is virtually un-researchable. Starting with a researchable topic is critical to writing an effective paper.

Research shows that students are much more invested in writing when they are able to choose their own topics. However, there is also research to support the notion that students are completely overwhelmed and frustrated when they are given complete freedom to write about whatever they choose. Providing some structure or topic themes that allow students to make bounded choices may be a way mitigate these competing realities.

These handouts can be modified or edited for your purposes. One can be used as a handout for students while the other can serve as a sample answer key. The document is best used as part of a process. For instance, perhaps starting with discussing the issues and potential research questions, moving on to problems and social significance but returning to proposals/solutions at a later date.

- Research Questions - Handout Key (2 pgs) This document is a condensed version of "What Makes a Good Research Topic". It serves as a key.

- Research Questions - Handout for Students (2 pgs) This document could be used with a class to discuss sample research questions (are they suitable?) and to have them start thinking about problems, social significance, and solutions for additional sample research questions.

- Research Question Discussion This tab includes materials for introduction students to research question criteria for a problem/solution essay.

Additional Resources

These documents have similarities to those above. They represent original documents and conversations about research questions from previous TRAIL trainings.

- What Makes a Good Research Topic? - Original Handout (4 pgs)

- What Makes a Good Research Topic? Revised Jan. 2016 (4 pgs)

- What Makes a Good Research Topic? Revised Jan 2016 with comments

Topic Selection (NCSU Libraries)

Howard, Rebecca Moore, Tricia Serviss, and Tanya K. Rodrigues. " Writing from sources, writing from sentences ." Writing & Pedagogy 2.2 (2010): 177-192.

Research Journal

Assign after students have participated in the Developing Successful Research Topics/Questions Lesson OR have drafted a Research Proposal.

Think about your potential research question.

- What is the problem that underlies your question?

- Is the problem of social significance? Explain.

- Is your proposed solution to the problem feasible? Explain.

- Do you think there is evidence to support your solution?

Keys for Writers - Additional Resource

Keys for Writers (Raimes and Miller-Cochran) includes a section to guide students in the formation of an arguable claim (thesis). The authors advise students to avoid the following since they are not debatable.

- "a neutral statement, which gives no hint of the writer's position"

- "an announcement of the paper's broad subject"

- "a fact, which is not arguable"

- "a truism (statement that is obviously true)"

- "a personal or religious conviction that cannot be logically debated"

- "an opinion based only on your feelings"

- "a sweeping generalization" (Section 4C, pg. 52)

The book also provides examples and key points (pg. 53) for a good working thesis.

- << Previous: #5 Integrating Sources

- Next: Research Question Discussion >>

- Last Updated: Apr 26, 2024 10:23 AM

- URL: https://libguides.ucmerced.edu/think_like_a_researcher

- Skip to search box

- Skip to main content

Princeton University Library

Doing research at princeton's library: introduction: sample lesson plans.

- chat widget

- Library Nuts and Bolts

- 1)Background Information

- 4)Specialized Article Databases

- 5)News Sources

- Teaching with Special Collections

- Evaluating Your Sources

- Sample Lesson Plans

- Bibliographies Made Simple!

- Academic Integrity at Princeton

Sample Library Research Lesson Plans

- Intro to the PUL/PWP Collaboration (includes lesson plan ideas)

- The Great Library Scavenger Hunt

- Ideal (or ""Dream") Source Exercise

- << Previous: Evaluating Your Sources

- Next: Bibliographies Made Simple! >>

- Last Updated: Apr 16, 2024 11:35 AM

- URL: https://libguides.princeton.edu/pul4pwp

- Find My Rep

You are here

100 Activities for Teaching Research Methods

- Catherine Dawson - Self-employed researcher and writer

- Description

A sourcebook of exercises, games, scenarios and role plays, this practical, user-friendly guide provides a complete and valuable resource for research methods tutors, teachers and lecturers.

Developed to complement and enhance existing course materials, the 100 ready-to-use activities encourage innovative and engaging classroom practice in seven areas:

- finding and using sources of information

- planning a research project

- conducting research

- using and analyzing data

- disseminating results

- acting ethically

- developing deeper research skills.

Each of the activities is divided into a section on tutor notes and student handouts. Tutor notes contain clear guidance about the purpose, level and type of activity, along with a range of discussion notes that signpost key issues and research insights. Important terms, related activities and further reading suggestions are also included.

Not only does the A4 format make the student handouts easy to photocopy, they are also available to download and print directly from the book’s companion website for easy distribution in class.

Supplements

Catherine's book is a fantastic resource for anyone who is teaching research methods in the social sciences. Covering all aspects of the research process, it is packed full of innovative ideas, useful tips, and structured activities for use within the classroom. If you are a tutor, teacher, or lecturer who is looking to provide interesting and engaging content for your students, this book is an absolute 'must have'.

Every university with a Social Science department has to deliver research methods in some capacity, but there is no need for us all to sit in our institutional silos and reinvent the wheel. Dawson provides a huge and varied list of pre-designed activities for methods teachers to draw upon covering the whole research process and an eclectic range of methodological approaches. The activities are pedagogically engaging, comprehensively resourced and provide us with an opportunity to rethink how social science research methods can be taught in a more interactive and engaging way.

Preview this book

Sample materials & chapters.

100 Activities for Teaching Research Methods: Listening to Interviewees

For instructors

Select a purchasing option, order from:.

- VitalSource

- Amazon Kindle

- Google Play

Related Products

Interactive Research Methods Lab

- Current Students

- Online Only Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Parents & Family

- Alumni & Friends

- Community & Business

- Student Life

- 360 Virtual Tour

- Resources for each step of the process

Lesson Plans

- IRML Virtual Library

- Pocket version of the IRML

- Online Training

- IRML at Universidad del Rosario

- WRITE Boost Grant

- GaDOE-Induction rubric

- Evaluation of Xplorlabs

- Atlanta’s Future in Tech think tank

- Art, Healing & the Aesthetic Experience (AHAE)

- Early Detection of BER

- Hopscotch 4-SoTL

- Hopscotch 4-Teachers

- Literature Review Design

- Pláticas con Maestr@s

- Teacher Emotional Experiences in the “Post-Pandemic” Classroom

- Quasi project

- Teacher Emotional Experiences in the Pandemic

- Who is using the Lab

- Calendar of Events

- Instructional Resources

The lesson plans below have been collaboratively created by the Interactive Research Methods Lab's Team, and colleagues interested in using the lab in their own courses. They can be used as examples of the different learning experiences that can be conducted in the IRML.

Contact Info

Kennesaw Campus 1000 Chastain Road Kennesaw, GA 30144

Marietta Campus 1100 South Marietta Pkwy Marietta, GA 30060

Campus Maps

Phone 470-KSU-INFO (470-578-4636)

kennesaw.edu/info

Media Resources

Resources For

Related Links

- Financial Aid

- Degrees, Majors & Programs

- Job Opportunities

- Campus Security

- Global Education

- Sustainability

- Accessibility

470-KSU-INFO (470-578-4636)

© 2024 Kennesaw State University. All Rights Reserved.

- Privacy Statement

- Accreditation

- Emergency Information

- Report a Concern

- Open Records

- Human Trafficking Notice

Research Building Blocks: "Cite Those Sources!"

- Resources & Preparation

- Instructional Plan

- Related Resources

Children are naturally curious—they want to know "how" and "why." Teaching research skills can help students find answers for themselves. This lesson is taken from a research skills unit where the students complete a written report on a state symbol. Here, students learn the importance of citing their sources to give credit to the authors of their information as well as learn about plagiarism. They explore a Website about plagiarism to learn the when and where of citing sources as well as times when citing sources is not necessary. They look at examples of acceptable and unacceptable paraphrasing. Finally, students practice citing sources and creating a bibliography.

Featured Resources

Avoiding Plagiarism : This resource from Purdue OWL gives comprehensive advice about how to avoid plagiarism.

From Theory to Practice

Teaching the process and application of research should be an ongoing part of all school curricula. It is important that research components are taught all through the year, beginning on the first day of school. Dreher et al. explain that "[S]tudents need to learn creative and multifaceted approaches to research and inquiry. The ability to identify good topics, to gather information, and to evaluate, assemble, and interpret findings from among the many general and specialized information sources now available to them is one of the most vital skills that students can acquire" (39).

Further Reading

Common Core Standards

This resource has been aligned to the Common Core State Standards for states in which they have been adopted. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, CCSS alignments are forthcoming.

State Standards

This lesson has been aligned to standards in the following states. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, standard alignments are not currently available for that state.

NCTE/IRA National Standards for the English Language Arts

- 1. Students read a wide range of print and nonprint texts to build an understanding of texts, of themselves, and of the cultures of the United States and the world; to acquire new information; to respond to the needs and demands of society and the workplace; and for personal fulfillment. Among these texts are fiction and nonfiction, classic and contemporary works.

- 3. Students apply a wide range of strategies to comprehend, interpret, evaluate, and appreciate texts. They draw on their prior experience, their interactions with other readers and writers, their knowledge of word meaning and of other texts, their word identification strategies, and their understanding of textual features (e.g., sound-letter correspondence, sentence structure, context, graphics).

- 4. Students adjust their use of spoken, written, and visual language (e.g., conventions, style, vocabulary) to communicate effectively with a variety of audiences and for different purposes.

- 5. Students employ a wide range of strategies as they write and use different writing process elements appropriately to communicate with different audiences for a variety of purposes.

- 6. Students apply knowledge of language structure, language conventions (e.g., spelling and punctuation), media techniques, figurative language, and genre to create, critique, and discuss print and nonprint texts.

- 7. Students conduct research on issues and interests by generating ideas and questions, and by posing problems. They gather, evaluate, and synthesize data from a variety of sources (e.g., print and nonprint texts, artifacts, people) to communicate their discoveries in ways that suit their purpose and audience.

- 8. Students use a variety of technological and information resources (e.g., libraries, databases, computer networks, video) to gather and synthesize information and to create and communicate knowledge.

- 11. Students participate as knowledgeable, reflective, creative, and critical members of a variety of literacy communities.

- 12. Students use spoken, written, and visual language to accomplish their own purposes (e.g., for learning, enjoyment, persuasion, and the exchange of information).

Materials and Technology

- Chart paper

- Internet access

Student Objectives

Students will

- discuss plagiarism.

- practice paraphrasing.

- credit sources used in research.

Instruction & Activities

- It is very important for students to understand the need for, and purpose of, giving credit to the sources they use in the research process. The students need to learn about the concept of plagiarism. Plagiarism is using others' ideas or words without clearly acknowledging the source of that information. While discussing the concept of plagiarism, use this avoiding plagiarism Web page to learn the when and where of citing sources as well as times when citing sources is not necessary.

- To remind students of the basic rules to avoid plagiarism, write the following on chart paper and post it close to the research area or media center in the classroom.

another person's idea, opinion, or theory.

any facts, statistics, graphs, drawings-any pieces of information-that are not common knowledge.

quotations of another person's actual spoken or written words.

paraphrases of another person's spoken or written words.

- After the discussion, use the example paragraph from How to Recognize Unacceptable and Acceptable Paraphrases to show the appropriate/inappropriate way to paraphrase information.

- providing them with a group of resources to create a bibliography for frequent practice in an activity or learning-center situation. Creating a Bibliography for Your Report discusses the various components of a bibliography.

- modeling the step-by-step development of a bibliography for your class in a variety of settings and subject areas.

- posting the standard bibliography format in a prominent place in your classroom.

Student Assessment / Reflections

As this is only one step in teaching the research process, students need not be graded on the activity. Continued practice in paraphrasing and quoting material is most important, with teacher and peer feedback benefitting the student researcher. Final bibliographies turned in with the research report could then be graded based on accurate information and style.

- Professional Library

- Lesson Plans

Add new comment

- Print this resource

Explore Resources by Grade

- Kindergarten K

Research Lesson Plan: Research to Build and Present Knowledge

*Click to open and customize your own copy of the Research Lesson Plan.

This lesson accompanies the BrainPOP topic Research , and supports the standard of gathering relevant information from multiple sources. Students demonstrate understanding through a variety of projects.

Step 1: ACTIVATE PRIOR KNOWLEDGE

Prompt students to think of a time they had to do research, either for school or for themselves. Ask:

- How did you determine what information to look for?

- What went well? What was challenging?

Step 2: BUILD KNOWLEDGE

- Read aloud the description on the Research topic page .

- Play the Movie , pausing to check for understanding.

- Assign Related Reading .

Step 3: APPLY and ASSESS

Assign Research Challenge and Quiz , prompting students to apply essential literacy skills while demonstrating what they learned about this topic.

Step 4: DEEPEN and EXTEND

Students express what they learned about research while practicing essential literacy skills with one or more of the following activities. Differentiate by assigning ones that meet individual student needs.

- Make-a-Movie : Create a tutorial that explains the steps for writing a research report.

- Make-a-Map : Make a spider map in which you state a research question in the center, and around it, identify sub questions and sources for finding answers in order to write a research report.

- Creative Coding : Code a museum where each artifact represents a component of the research process.

More to Explore

Related BrainPOP Topics : Deepen understanding of research with these topics: Online Sources , Internet Search , and Citing Sources .

Teacher Support Resources:

- Pause Point Overview : Video tutorial showing how Pause Points actively engage students to stop, think, and express ideas.

- Learning Activities Modifications : Strategies to meet ELL and other instructional and student needs.

- Learning Activities Support : Resources for best practices using BrainPOP.

Lesson Plan Common Core State Standards Alignments

- BrainPOP Jr. (K-3)

- BrainPOP ELL

- BrainPOP Science

- BrainPOP Español

- BrainPOP Français

- Set Up Accounts

- Single Sign-on

- Manage Subscription

- Quick Tours

- About BrainPOP

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Trademarks & Copyrights

Interactive Science: How to Design Research-based Science Lessons

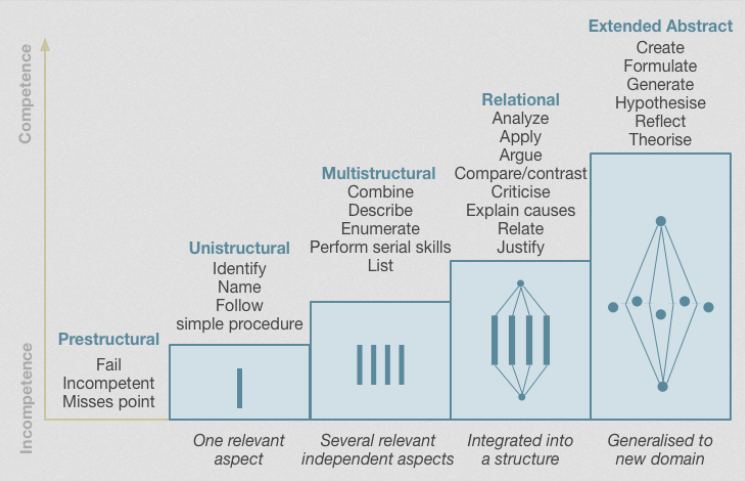

Recently, a school district administrator emailed me and asked, “If you were going to blend strategies that work into a science lesson, how would you do it?” That question really piqued my interest. Mixing instructional strategies that are proven to work with best practices in science teaching and learning sounds like a win/win. After much thinking, here’s how I would accomplish this, based on the research.

Step #1: Set Goals for the Science Lesson

Dr. John Almarode, who wrote Visible Learning for Science , suggests setting the following goals for science lessons. The goals are straightforward and represent a wonderful response to the question asked.

- Get students interested in lifelong learning and science that works.

- Give students more control over their own learning.

- Build in ways to assess students to discover where they are, and then match strategies to what they need to learn.

The first goal is practical and makes learning relevant to the learner. The second ties into John Hattie’s strong belief in the need for students to be self-regulated learners, individuals who must have agency and ownership over their learning and are able to track their progress. In tracking their own growth towards learning targets, they can make decisions, which gives them voice and choice.

Step #2: Pre-Assess Student Learning

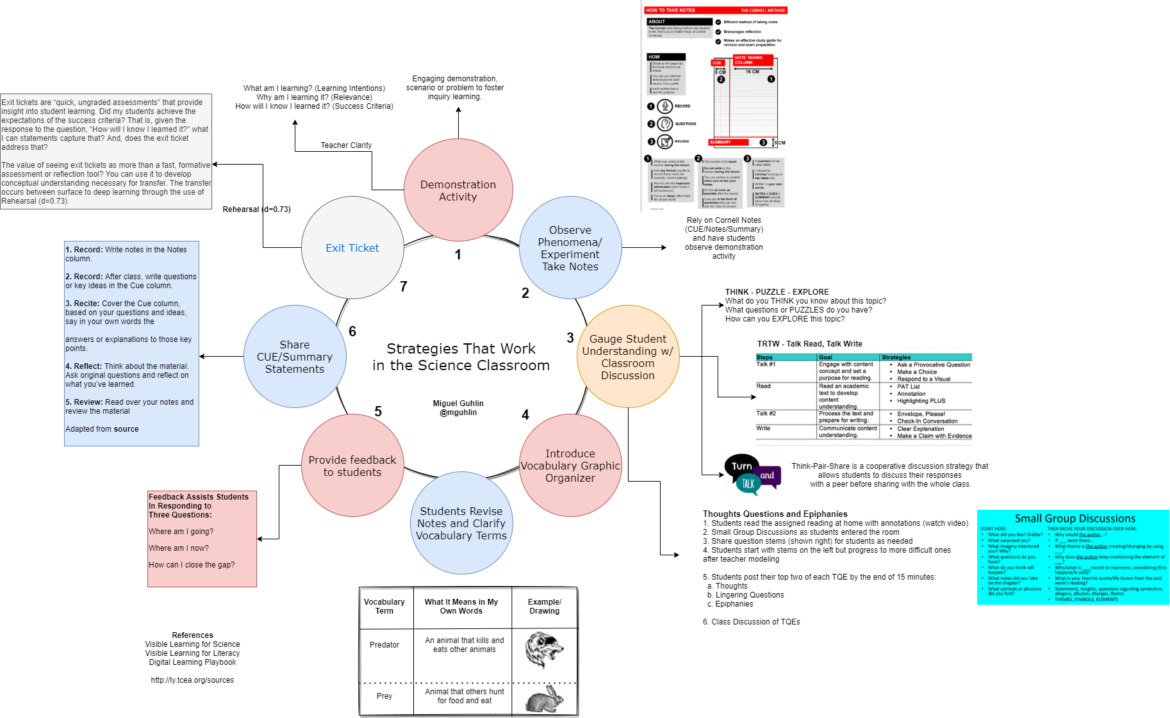

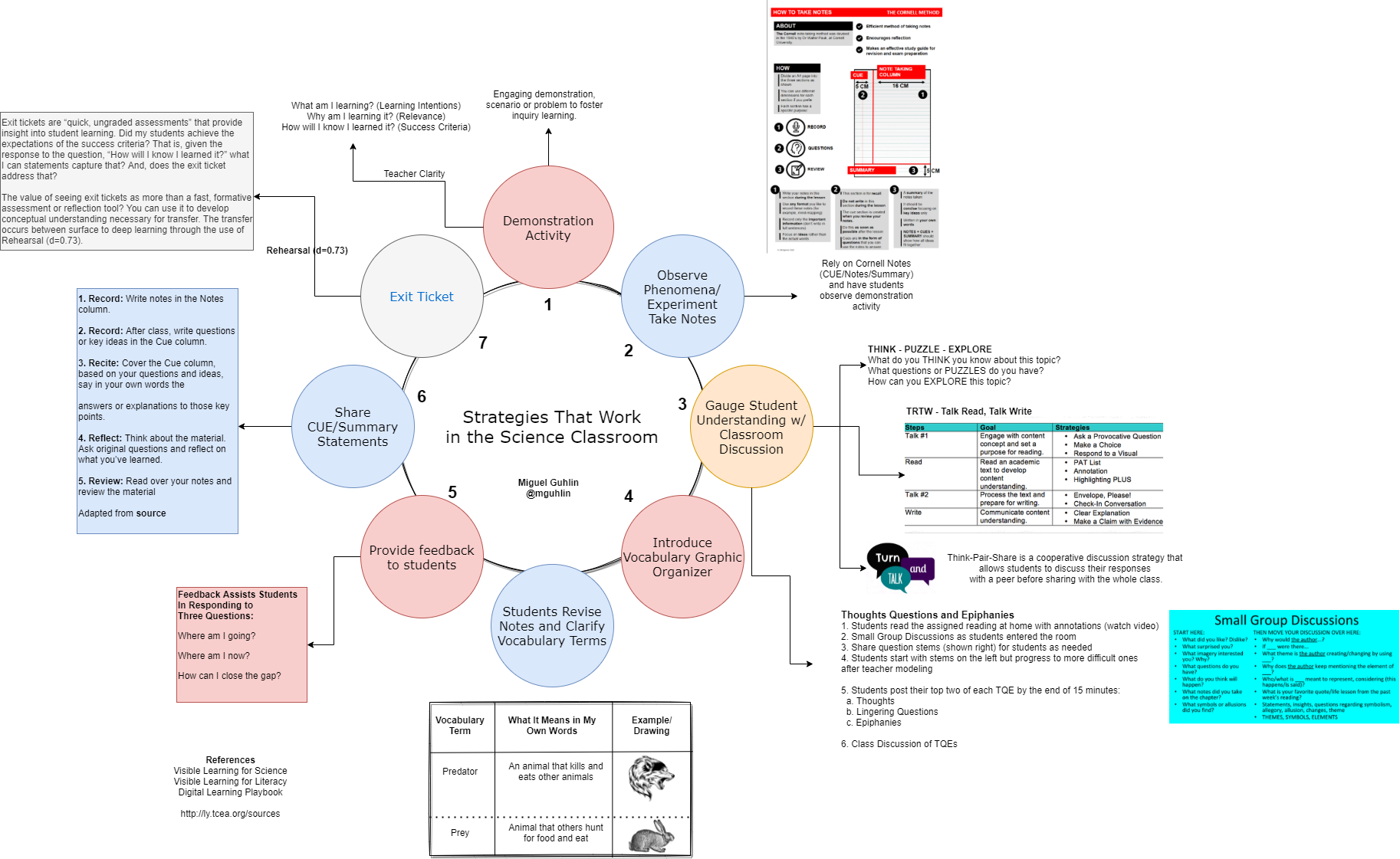

When determining what students already know about a topic or skill, you have to ask, “How do we pre-assess students where they are at?” This leads to the question, “What are some formative assessments we could use?” These assessments provide insights into where students may fall on the SOLO Taxonomy. SOLO stands for “Structure of Observed Learning Outcome.” This isn’t the first time I’ve mentioned SOLO , as have many others.

Let’s revisit what SOLO Taxonomy offers:

SOLO illustrates the qualitative differences. It indicates the differences between student responses and their levels of understanding. It classifies outcomes, relying on complexity and understanding.

SOLO does this so that you can make a judgement on the quality of student responses to assessment tasks . It relies on five levels of understanding:

Prestructural: at this level the learner is missing the point

Unistructural: a response based on a single point.

Multistructural: a response with multiple unrelated points.

Relational: points presented in a logically related answer.

Extended abstract: demonstrating an abstract and deep understanding through unexpected extension.

This FutureLearn chart clarifies the levels:

The Structure of the Observed Learning Outcome (SOLO) taxonomy (Adapted from Biggs & Tang, 2011) as cited in source

The main benefit of the SOLO Taxonomy is that it gives you, as the teacher, a set of specific terms (e.g., Unistructural, Multistructural, Relational) that can describe a student’s level of understanding. This level of understanding pinpoints what strategies may work best for them as they more through the learning process.

For students who are unistructural, they are in the surface phase of learning. This means that you might rely on those types of strategies, which could include vocabulary programs, direct instruction, and/or flipped classroom.

For learners who are relational, in the deep learning phase, different strategies work best. These may include concept mapping, metacognition, and reflection.

Knowing where a child falls on the taxonomy helps identify their level of understanding. It also assists you in knowing what to do next and to set success criteria.

What Is Success Criteria?

This phrase involves students knowing and understanding the answer to a simple question. That is, “How will I know I have learned it?” It is sometimes expressed as a statement, “I’ll know I’ve got it if….” You may want to revisit COLOSO in this blog entry .

Step #3: Build Learning into the Science Lesson

Ready to start on lesson design? Let’s take a look at the process Dr. John Almarode elaborates on. I’ve included a few resources for each area. What would you add?

“Science education needs a mix of demonstrations, labs, and experiments. It also needs reading, writing, and discussing with other scientists,” says Almarode. To that end, the lesson process he describes looks like this:

a) Paired Demonstration and Writing Down Observations

- Demonstration

- Encourage students to write about what they observed

b) Clarifying Terms and Vocabulary

- Discussion about vocabulary terms

- Have students revise their writing using correct terms

- Final wrap-up

One key point that jumped out at me?

Every lesson (surface, deep, transfer) needs to have a clearly articulated learning intention. That learning intention must connect to success criteria. Remember, that is “What am I learning?” (learning intention) and “How will I know I have learned it?” (success criteria).

That’s quite a jump. To help the process make more sense, I put this diagram together that captures my understanding. Don’t be afraid to share your version.

Get a copy of this image via Google Slides or via Diagrams.net (requires you to authorize Diagrams.net in Google Drive account).

As you can see from this diagram, there’s a lot going on. To complicate matters, I’ve included some additional tools and strategy suggestions. How would you approach lesson design in your classroom with these three steps?

Matching Process to Resources

To provide some support, please find some relevant resources organized by the step in the process. I’ve organized them into a meta-collection in Wakelet. Explore and have fun.

Feature Image Source

Photo by author.

Miguel Guhlin

Transforming teaching, learning and leadership through the strategic application of technology has been Miguel Guhlin’s motto. Learn more about his work online at blog.tcea.org , mguhlin.org , and mglead.org /mglead2.org. Catch him on Mastodon @[email protected] Areas of interest flow from his experiences as a district technology administrator, regional education specialist, and classroom educator in bilingual/ESL situations. Learn more about his credentials online at mguhlin.net.

How to Make Interactive Maps with Google Slides and a Digital Whiteboard

Fun icebreaker jamboard templates for back to school, you may also like, the frayer model: transforming vocabulary learning in all..., blast off into learning: celebrate national astronaut day, how to make flexible, data-informed student groups, five stages of k-12 ed tech adoption: part..., earth day ideas to inspire young eco-heroes, four solar eclipse-themed activities, 2024 speakup survey for k-12 leaders, the new k-5 science teks and free, editable..., science activities for critical thinking, unesco’s 2023 gem report: tcea’s solution to the..., leave a comment cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

You've Made It This Far

Like what you're reading? Sign up to stay connected with us.

*By downloading, you are subscribing to our email list which includes our daily blog straight to your inbox and marketing emails. It can take up to 7 days for you to be added. You can change your preferences at any time.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

By subscribing, you will receive our daily blog, newsletter, and marketing emails.

How to write a research plan: Step-by-step guide

Last updated

30 January 2024

Reviewed by

Today’s businesses and institutions rely on data and analytics to inform their product and service decisions. These metrics influence how organizations stay competitive and inspire innovation. However, gathering data and insights requires carefully constructed research, and every research project needs a roadmap. This is where a research plan comes into play.

There’s general research planning; then there’s an official, well-executed research plan. Whatever data-driven research project you’re gearing up for, the research plan will be your framework for execution. The plan should also be detailed and thorough, with a diligent set of criteria to formulate your research efforts. Not including these key elements in your plan can be just as harmful as having no plan at all.

Read this step-by-step guide for writing a detailed research plan that can apply to any project, whether it’s scientific, educational, or business-related.

- What is a research plan?

A research plan is a documented overview of a project in its entirety, from end to end. It details the research efforts, participants, and methods needed, along with any anticipated results. It also outlines the project’s goals and mission, creating layers of steps to achieve those goals within a specified timeline.

Without a research plan, you and your team are flying blind, potentially wasting time and resources to pursue research without structured guidance.

The principal investigator, or PI, is responsible for facilitating the research oversight. They will create the research plan and inform team members and stakeholders of every detail relating to the project. The PI will also use the research plan to inform decision-making throughout the project.

- Why do you need a research plan?

Create a research plan before starting any official research to maximize every effort in pursuing and collecting the research data. Crucially, the plan will model the activities needed at each phase of the research project.

Like any roadmap, a research plan serves as a valuable tool providing direction for those involved in the project—both internally and externally. It will keep you and your immediate team organized and task-focused while also providing necessary definitions and timelines so you can execute your project initiatives with full understanding and transparency.

External stakeholders appreciate a working research plan because it’s a great communication tool, documenting progress and changing dynamics as they arise. Any participants of your planned research sessions will be informed about the purpose of your study, while the exercises will be based on the key messaging outlined in the official plan.

Here are some of the benefits of creating a research plan document for every project:

Project organization and structure

Well-informed participants

All stakeholders and teams align in support of the project

Clearly defined project definitions and purposes

Distractions are eliminated, prioritizing task focus

Timely management of individual task schedules and roles

Costly reworks are avoided

- What should a research plan include?

The different aspects of your research plan will depend on the nature of the project. However, most official research plan documents will include the core elements below. Each aims to define the problem statement, devising an official plan for seeking a solution.

Specific project goals and individual objectives

Ideal strategies or methods for reaching those goals

Required resources

Descriptions of the target audience, sample sizes, demographics, and scopes

Key performance indicators (KPIs)

Project background

Research and testing support

Preliminary studies and progress reporting mechanisms

Cost estimates and change order processes

Depending on the research project’s size and scope, your research plan could be brief—perhaps only a few pages of documented plans. Alternatively, it could be a fully comprehensive report. Either way, it’s an essential first step in dictating your project’s facilitation in the most efficient and effective way.

- How to write a research plan for your project

When you start writing your research plan, aim to be detailed about each step, requirement, and idea. The more time you spend curating your research plan, the more precise your research execution efforts will be.

Account for every potential scenario, and be sure to address each and every aspect of the research.

Consider following this flow to develop a great research plan for your project:

Define your project’s purpose

Start by defining your project’s purpose. Identify what your project aims to accomplish and what you are researching. Remember to use clear language.

Thinking about the project’s purpose will help you set realistic goals and inform how you divide tasks and assign responsibilities. These individual tasks will be your stepping stones to reach your overarching goal.

Additionally, you’ll want to identify the specific problem, the usability metrics needed, and the intended solutions.

Know the following three things about your project’s purpose before you outline anything else:

What you’re doing

Why you’re doing it

What you expect from it

Identify individual objectives

With your overarching project objectives in place, you can identify any individual goals or steps needed to reach those objectives. Break them down into phases or steps. You can work backward from the project goal and identify every process required to facilitate it.

Be mindful to identify each unique task so that you can assign responsibilities to various team members. At this point in your research plan development, you’ll also want to assign priority to those smaller, more manageable steps and phases that require more immediate or dedicated attention.

Select research methods

Research methods might include any of the following:

User interviews: this is a qualitative research method where researchers engage with participants in one-on-one or group conversations. The aim is to gather insights into their experiences, preferences, and opinions to uncover patterns, trends, and data.

Field studies: this approach allows for a contextual understanding of behaviors, interactions, and processes in real-world settings. It involves the researcher immersing themselves in the field, conducting observations, interviews, or experiments to gather in-depth insights.

Card sorting: participants categorize information by sorting content cards into groups based on their perceived similarities. You might use this process to gain insights into participants’ mental models and preferences when navigating or organizing information on websites, apps, or other systems.

Focus groups: use organized discussions among select groups of participants to provide relevant views and experiences about a particular topic.

Diary studies: ask participants to record their experiences, thoughts, and activities in a diary over a specified period. This method provides a deeper understanding of user experiences, uncovers patterns, and identifies areas for improvement.

Five-second testing: participants are shown a design, such as a web page or interface, for just five seconds. They then answer questions about their initial impressions and recall, allowing you to evaluate the design’s effectiveness.

Surveys: get feedback from participant groups with structured surveys. You can use online forms, telephone interviews, or paper questionnaires to reveal trends, patterns, and correlations.

Tree testing: tree testing involves researching web assets through the lens of findability and navigability. Participants are given a textual representation of the site’s hierarchy (the “tree”) and asked to locate specific information or complete tasks by selecting paths.

Usability testing: ask participants to interact with a product, website, or application to evaluate its ease of use. This method enables you to uncover areas for improvement in digital key feature functionality by observing participants using the product.

Live website testing: research and collect analytics that outlines the design, usability, and performance efficiencies of a website in real time.

There are no limits to the number of research methods you could use within your project. Just make sure your research methods help you determine the following:

What do you plan to do with the research findings?

What decisions will this research inform? How can your stakeholders leverage the research data and results?

Recruit participants and allocate tasks

Next, identify the participants needed to complete the research and the resources required to complete the tasks. Different people will be proficient at different tasks, and having a task allocation plan will allow everything to run smoothly.

Prepare a thorough project summary

Every well-designed research plan will feature a project summary. This official summary will guide your research alongside its communications or messaging. You’ll use the summary while recruiting participants and during stakeholder meetings. It can also be useful when conducting field studies.

Ensure this summary includes all the elements of your research project. Separate the steps into an easily explainable piece of text that includes the following:

An introduction: the message you’ll deliver to participants about the interview, pre-planned questioning, and testing tasks.

Interview questions: prepare questions you intend to ask participants as part of your research study, guiding the sessions from start to finish.

An exit message: draft messaging your teams will use to conclude testing or survey sessions. These should include the next steps and express gratitude for the participant’s time.

Create a realistic timeline

While your project might already have a deadline or a results timeline in place, you’ll need to consider the time needed to execute it effectively.

Realistically outline the time needed to properly execute each supporting phase of research and implementation. And, as you evaluate the necessary schedules, be sure to include additional time for achieving each milestone in case any changes or unexpected delays arise.

For this part of your research plan, you might find it helpful to create visuals to ensure your research team and stakeholders fully understand the information.

Determine how to present your results

A research plan must also describe how you intend to present your results. Depending on the nature of your project and its goals, you might dedicate one team member (the PI) or assume responsibility for communicating the findings yourself.

In this part of the research plan, you’ll articulate how you’ll share the results. Detail any materials you’ll use, such as:

Presentations and slides

A project report booklet

A project findings pamphlet

Documents with key takeaways and statistics

Graphic visuals to support your findings

- Format your research plan

As you create your research plan, you can enjoy a little creative freedom. A plan can assume many forms, so format it how you see fit. Determine the best layout based on your specific project, intended communications, and the preferences of your teams and stakeholders.

Find format inspiration among the following layouts:

Written outlines

Narrative storytelling

Visual mapping

Graphic timelines

Remember, the research plan format you choose will be subject to change and adaptation as your research and findings unfold. However, your final format should ideally outline questions, problems, opportunities, and expectations.

- Research plan example

Imagine you’ve been tasked with finding out how to get more customers to order takeout from an online food delivery platform. The goal is to improve satisfaction and retain existing customers. You set out to discover why more people aren’t ordering and what it is they do want to order or experience.

You identify the need for a research project that helps you understand what drives customer loyalty. But before you jump in and start calling past customers, you need to develop a research plan—the roadmap that provides focus, clarity, and realistic details to the project.

Here’s an example outline of a research plan you might put together:

Project title

Project members involved in the research plan

Purpose of the project (provide a summary of the research plan’s intent)

Objective 1 (provide a short description for each objective)

Objective 2

Objective 3

Proposed timeline

Audience (detail the group you want to research, such as customers or non-customers)

Budget (how much you think it might cost to do the research)

Risk factors/contingencies (any potential risk factors that may impact the project’s success)

Remember, your research plan doesn’t have to reinvent the wheel—it just needs to fit your project’s unique needs and aims.

Customizing a research plan template

Some companies offer research plan templates to help get you started. However, it may make more sense to develop your own customized plan template. Be sure to include the core elements of a great research plan with your template layout, including the following:

Introductions to participants and stakeholders

Background problems and needs statement

Significance, ethics, and purpose

Research methods, questions, and designs

Preliminary beliefs and expectations

Implications and intended outcomes

Realistic timelines for each phase

Conclusion and presentations

How many pages should a research plan be?

Generally, a research plan can vary in length between 500 to 1,500 words. This is roughly three pages of content. More substantial projects will be 2,000 to 3,500 words, taking up four to seven pages of planning documents.

What is the difference between a research plan and a research proposal?

A research plan is a roadmap to success for research teams. A research proposal, on the other hand, is a dissertation aimed at convincing or earning the support of others. Both are relevant in creating a guide to follow to complete a project goal.

What are the seven steps to developing a research plan?

While each research project is different, it’s best to follow these seven general steps to create your research plan:

Defining the problem

Identifying goals

Choosing research methods

Recruiting participants

Preparing the brief or summary

Establishing task timelines

Defining how you will present the findings

Get started today

Go from raw data to valuable insights with a flexible research platform

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 21 December 2023

Last updated: 16 December 2023

Last updated: 6 October 2023

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 12 May 2023

Last updated: 15 February 2024

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 18 May 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 10 April 2023

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

Research Based Lesson Design

Here is the presentation used at the Dig Deeper into RBLD training .

In Anaheim Elementary School District, our core audience is English learners. Tier one instruction must be designed to meet the needs of at least 80% of students which typically includes English learners. While all students benefit from Explicit Direct Instruction (EDI), English learners need EL scaffolds in conjunction with EDI. With Research Based Lesson Design (RBLD), English learner strategies are planned for every instructional phases of EDI. For a one page printable handout of the EL scaffolds in RBLD, click here .

Both Concept Development and Guided Practice are taught using a gradual release of responsibility .

For lesson planning, the sequence that RBLD phases are planned differs from the order in which they are taught. Grade level teams are encouraged to collaborate in planning lessons. A lesson using RBLD can be planned using different formats. Some possible options are in a PowerPoint , on paper and pencil, on a poster, or using this optional template (Click “File,” then “Make a copy.”) Contact your Curriculum Coach for any support.

Learning Objectives

Activate prior knowledge, lesson importance, concept development, skill development, guided practice, lesson closure, independent practice, strategies used throughout a lesson.

Content objective is defined, displayed, and reviewed orally.

Visuals/TPR as appropriate for clarification

Highlight, circle, color code

Academic language restated in more comprehensible language

Sentence stem

Prior lesson visual support

Primary language connections (e.g. cognates)

Write, draw, share, TPR during Interact Step

Bridge Map to connect new learning

Multi-Flow Map that shows the effects from learning the lesson’s objective

Examples are visually displayed

Sentence frames or stems

Contextualized definitions and vocabulary charts

Discovery Education clips (Web 2.0 support)

Visual indications for examples v. non-examples

Pictorial support , TPR , realia

Highlighting, circling, underlining, color coding

Thinking Maps

Flow Map for procedure

Note-taking/process grids

Partner support

Sentence frames

Visual support/TPR

Color coding

Access to visuals from the lesson

Structured Think Pair Share

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Step 1: Begin the lesson plan with an image [3 minutes] Show the third slide of the PowerPoint presentation with a picture of stacked books and an apple on the top of the book that is titled "Education.". Begin to discuss the significance of the apple as. a very powerful fruit.

Lesson Plan 1: Research paper Writing: An Overview . Objectives: -SWBAT identify parts that comprise a scientific research paper -SWBAT understand some different ways scientists develop ideas for their research -SWBAT understand the advantages of conducting a literature search -SWBAT understand the process of writing a research paper

Markowski, Brianne and Dineen, Rachel, "Lesson Plan: Characteristics of Effective Research Questions" (2018). Information Literacy. 15. This Lesson Plan is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources @ UNC at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Information Literacy by ...

This lesson plan accompanies the BrainPOP topic, Research, and can be completed over several class periods.See suggested times for each section. OBJECTIVES. Students will: Activate prior knowledge about how to do a research project.. Identify the sequence of events for conducting research.. Use critical thinking skills to analyze how and why having a focus is key to conducting research and ...

The student will learn how to do effective internet research. OBJECTIVE: This two-class lesson plan leads students through a discussion of the difficulties of internet research; provides guidance on how to effectively pre-research; demonstrates online resources available for research through the Brooklyn Collection and Brooklyn Public Library ...

Lesson plans/exercises: Research Clinic. Outline Session #1. One of Audrey's lesson plans for first session. Elana's plan (4 short sessions) Denise's plan for a Freshman Writing Seminar. Research Clinic Research clinic sample plan. Mini exercises. Videos created for flipped classroom ("asychronous" learning)

It outlines a five-step approach to break down the research process into manageable chunks. This post shares ideas for mini-lessons that could be carried out in the classroom throughout the year to help build students' skills in the five areas of: clarify, search, delve, evaluate, and cite. It also includes ideas for learning about staying ...

Feel free to make a copy any of the sample lesson plans linked to below, to use as is or adapt for your own purposes. ... Second semester course: First Year Research Seminar Sample lesson plan for FYRS; LIBERAL STUDIES - Administered by Liberal Studies. First semester course: ...

Course Learning Outcome: Develop ability to synthesize and express complex ideas; demonstrate information literacy and be able to work with evidence Goal: Develop students' ability to recognize and create successful research questions Specifically, students will be able to. identify the components of a successful research question. create a viable research question.

Princeton University Library One Washington Road Princeton, NJ 08544-2098 USA (609) 258-1470

Research Paper Scaffold: This handout guides students in researching and organizing the information they need for writing their research paper.; Inquiry on the Internet: Evaluating Web Pages for a Class Collection: Students use Internet search engines and Web analysis checklists to evaluate online resources then write annotations that explain how and why the resources will be valuable to the ...

Developed to complement and enhance existing course materials, the 100 ready-to-use activities encourage innovative and engaging classroom practice in seven areas: finding and using sources of information. planning a research project. conducting research. using and analyzing data. disseminating results.

The lesson plans below have been collaboratively created by the Interactive Research Methods Lab's Team, and colleagues interested in using the lab in their own courses. They can be used as examples of the different learning experiences that can be conducted in the IRML. Lesson plan for students taking EDSM 8901 (Graduate)

This lesson is taken from a research skills unit where the students complete a written report on a state symbol. Here, students learn the importance of citing their sources to give credit to the authors of their information as well as learn about plagiarism. They explore a Website about plagiarism to learn the when and where of citing sources ...

Step 3: APPLY and ASSESS. Assign Research Challenge and Quiz, prompting students to apply essential literacy skills while demonstrating what they learned about this topic. Step 4: DEEPEN and EXTEND. Students express what they learned about research while practicing essential literacy skills with one or more of the following activities.

Step #1: Set Goals for the Science Lesson. Dr. John Almarode, who wrote Visible Learning for Science, suggests setting the following goals for science lessons. The goals are straightforward and represent a wonderful response to the question asked. Get students interested in lifelong learning and science that works.

A Detailed Lesson Plan in English Grade 10. I. Objectives At the end of this lesson, the students will be able to: a. interpret the primary purpose of an academic research paper.; b. examine ways to get started with the writing process.; and c. explain the importance of research in daily lives

This lesson plan presents the concept of sampling in research. Students will discuss the sampling process, work in teams to design a sampling plan for a research scenario and critique real-world ...

DETAILED LESSON PLAN IN PRACTICAL RESEARCH 1 FOR CLASSROOM OBSERVATION. Date: May 30, 2022 Grade: Grade 11 Section: ABM-Huffington I. Objectives: ... At this time, let us analyse the scenario of a sample research paper on who are the respondents/ participants involved study, in what way do the researchers identify these participants and how the ...

Start by defining your project's purpose. Identify what your project aims to accomplish and what you are researching. Remember to use clear language. Thinking about the project's purpose will help you set realistic goals and inform how you divide tasks and assign responsibilities.

A DETAILED LESSON PLAN IN PRACTICAL RESEARCH 1 I. OBJECTIVES: At the end of the lesson, the students will be able to, Shares research experiences and knowledge, CS_RS11-IIIa-explains the importance of research in daily life, CS_RS11-IIIa-describes characteristics of research CS_RS11-IIIa- II. SUBJECT MATTER A. TOPIC Nature and Inquiry of ...

With Research Based Lesson Design (RBLD), English learner strategies are planned for every instructional phases of EDI. For a one page printable handout of the EL scaffolds in RBLD, click here. Both Concept Development and Guided Practice are taught using a gradual release of responsibility. For lesson planning, the sequence that RBLD phases ...

LESSON PLAN IN PRACTICAL RESEARCH 2 FOR GRADE 12 UNIT 1: NATURE OF INQUIRY AND RESEARCH. Date: June 26-27, 2018. I-OBJECTIVES: At the end of the lesson, the studens must: a. familiarize the nature of non-experimental research b. conduct a practicable survey research c. practice honesty and integrity in researching. II-SUBJECT MATTER: