UC Berkeley’s Premier Undergraduate Economics Journal

- Growth & Development

The Japanese Economic Miracle

HANNAH SHIOHARA – JANUARY 26TH, 2023

EDITOR: PALLAVI MURTHY

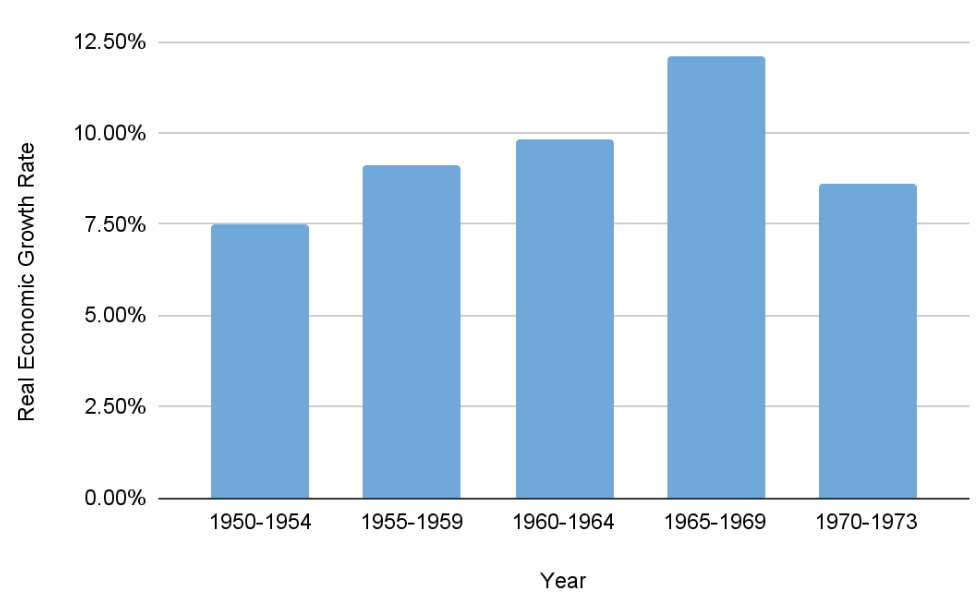

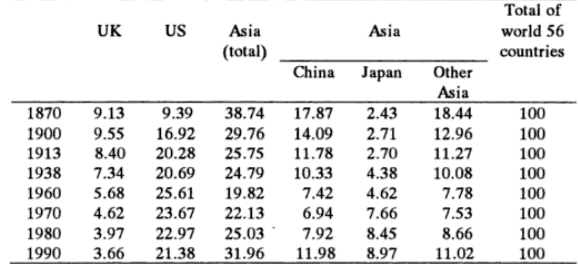

Economist Milton Friedman once said that “The best way to grow rapidly is to have the country bombarded.” Though it is hard to imagine a country prospering after losing everything, the Japanese post-war economy did just that. Japan unconditionally surrendered on August 14th 1945, with World War II costing the country an estimated 2.6 to 3.1 million lives and 56 billion USD . Though Japan was left with almost nothing, their economy recovered at an incredible speed. Known as the Japanese Economic Miracle, Japan experienced rapid and sustained economic growth from 1945 to 1991, the period between post World War II and the end of the Cold War. As depicted in Figure 1, the real growth rate was positive until 1973 and increased for 20 consecutive years. In less than ten years, Japan’s economy was growing at a peak rate last observed in 1939, with the economy growing two times faster than the prewar standard every year past 1955. There are four main factors that allowed for this super rapid growth: technological change, accumulation of capital, increased quantity and quality of labor, and increased international trade. Through strategic planning and cooperation by firms, individuals, and the government, Japan manipulated these factors to become the third-largest economy in the world. Though it has been 77 years since the end of World War II, many elements of Japan’s economic recovery remain relevant to our society and can be applied to countries that have recently emerged from conflict.

Figure 1. Japan’s real economic growth rate between 1950-1973 in 4 year increments.

Factor 1: Technological change

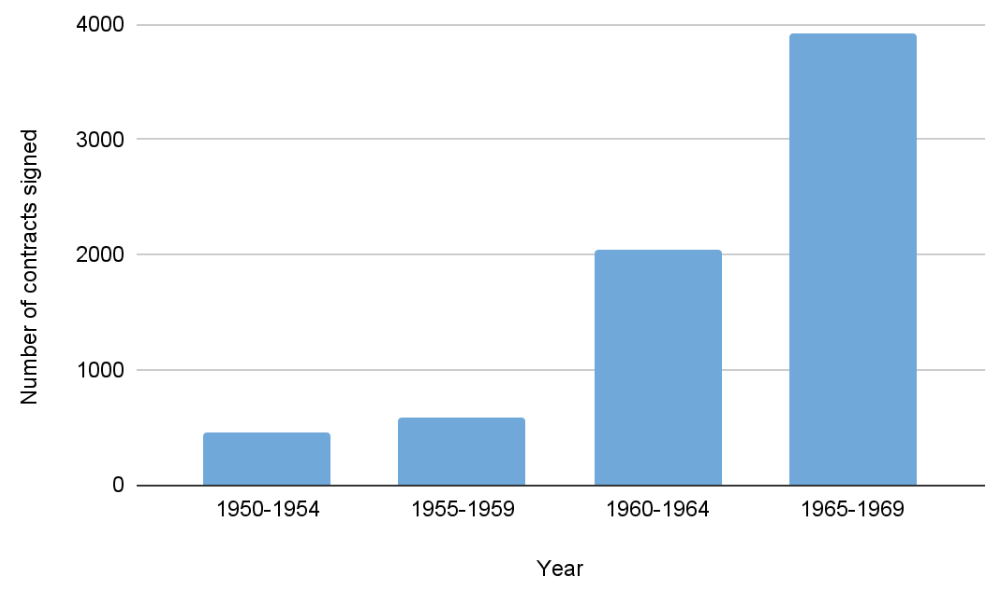

After the war, Japan had lost more than a quarter of its industrial capacity and was only left with over-depreciated capital stock that had no use. This allowed Japan to adopt an abundance of new technologies without having to wait for assets to be fully depreciated, fueling Japan’s voracious appetite to start fresh and innovate. Figure 2 depicts the number of contracts signed to import new technology, mainly in industries such as iron, steel, petrochemicals, electronics, motor manufacturing, and chemical engineering—sectors characterized by extremely high growth rates.

Figure 2. Number of contracts with a life of more than a year and paid in foreign currency that Japan signed to import new technology between 1950 and 1969.

Furthermore, several government policies favoring these technological changes were implemented. First, the government aggressively used expansionary monetary policy to create “cheap money,” such that growing industries had access to low-cost funds. Interest rates were rigid and closely monitored to be kept low, and corporate businesses were over borrowing while banks over loaned. The government also rewarded growing businesses with generous depreciation provisions and tax deductions; large, more rapidly growing corporations had lower tax rates than smaller, slower-growing firms. Personal income taxation was also slowed through partial exemption of interest and dividend incomes from taxation.

Foreign countries greatly influenced and inspired the creation of new technologies, and Japan began importing tremendous amounts of goods as well. For example, machine tools and robots were imported and became widely used in the automobile industry, while imported generators were adapted to improve the efficiency of the electric utility industry. In 1963, the Japan Information Center for Science and Technology wrote 210,000 abstracts of foreign scientific papers to make foreign ideas and knowledge accessible. The Japanese also took the new technologies they imported and improved it themselves, making the technology an estimated 20% more efficient. 9500 large firms reported on spending a third of their R&D expenditure and “modifying and perfecting the imported technique.”

Factor 2: Accumulation of capital

In order to import and implement the new technologies mentioned above, the Japanese concentrated their capital into investing in rapidly growing manufacturing industries. In contrast, people in other countries were investing more in housing or other social overhead capital. This difference came from the Japaneses’ great desire to close the technological gap between Japan and foreign countries and increase their international competitiveness. At the time, the returns of these investments were high because the marginal productivity of capital was so high. In order to balance these large investments and avoid extremely high inflation, there was also a high rate of personal saving. During 1959 and 1970, the ratio of personal savings to disposable income averaged at 18.3% in Japan, while it was only 12% in Germany and 7% in the United States.

Factor 3: Quantity and quality of labor

The increase in quantity and quality of labor also greatly contributed to Japan’s success, with the National Bureau of Economic Research estimating that it accounted for nearly 30% of the postwar Japanese growth. As people returned from war, there was a large increase in labor, allowing for wages to rise less than labor productivity in the 1950s. Even in the 1960s, productivity kept pace with wage increases, giving firms the ability to be efficient and grow. Labor also moved from low-productivity sectors such as agriculture and forestry, to high productivity sectors such as aviation, automobile, and electronics.

A key element to the Japanese Economic Miracle was the keiretsu . Keiretsu were very large business groups that linked banks, trading companies, and industrialists through ownership or stock and long standing exclusive relationships. Their mere size gave them the financial strength and connections they needed to outperform their domestic and foreign rivals, aggressively gaining market share in high-growth sectors with long term potential. The government also worked in favor of the keiretsu, implementing policies that would minimize any competition for the firms. The Ministry of International Trade and Industry allowed “administrative” cartels and collusive activities to take place, with more than 1,500 of them going unprosecuted. For example, mergers amongst the five largest firms in a given industry were approved, supporting anti-competitiveness. At the same time, the workplace culture of keiretsu played a large role in its success, because it improved the quality of labor. The Japanese business environment was extremely competitive, and all companies went to great lengths to keep up with one another. In order to continuously update product designs and implement new production techniques, employees were expected to work extremely long hours and stay loyal to the firm for a lifetime. They were held to high standards with strict rules, such as how low to bow to various superiors, with training for these roles starting at a young age. In fact, several of the world’s most practiced industrial practices such as total quality control, lean production, and cross-functional product teams are said to be first implemented in the keiretsu.

Factor 4: International Trade

Finally, Japan’s exports grew rapidly after the war, boosting the economy. By providing tax deductions for overseas sales expenditures and preferential loans, the government was able to lower the prices of exports, making them relatively cheaper than other countries. The mergers and anticompetitive behavior they encouraged were also mainly in sectors that exported their products. However, the single most important factor in international trade that allowed Japan to stay ahead of its competitors was its ability to change what they were exporting every couple of years. Between 1950 and 1965, Japan went from primarily exporting textiles and sundry goods to machinery, and finally to metals. Due to increased efficiency and corporations’ ability to keep up with changes in the international trading stage, Japan was able to provide goods that were in the most demand, increasing exports and thus real economic growth.

Lessons learned from the Japanese Economic Miracle

Today, most war-stricken countries are developing countries whose economies are primarily based on agriculture . For example, there were 15 countries at war in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2019. Specifically, Ethiopia’s civil war continues to be one of the most devastating conflicts of 2022. Agriculture in Ethiopia accounts for nearly 46% of GDP and 85% of total employment.

Since it is evident that favorable government policies played a crucial role in Japan’s economic recovery, comparable policies should be implemented in today’s post-conflict countries. For example, governments should shift their revenue source away from personal and business income taxes and to natural resource rights . Since these countries are abundant in natural resources and because natural resource extraction tends to decline during war, there will be a large demand for commodity goods in post-war economies. Instead of taxing firms’ operating in the primary sector, the government could tax the sale of the right to extraction, done through an auction that the African Union can oversee in cooperation with the Union African Development Bank and OECD. By making tax cuts in personal and business incomes, citizens and businesses can have some leeway in their post-war recovery. Taxing natural resource rights instead will make it easier for firms in high-growth sectors to make profits, but still ensure revenue for the government.

Furthermore, increased international collaboration will be imperative for the economic growth of post-conflict countries. While increased exports and the sharing of knowledge with foreign countries greatly contributed to Japan’s success, international agreements can help developing economies of today. Since commodities are subject to significant fluctuations in price, some economists have suggested negotiating international “commodity stabilization agreements” to protect vulnerable, but growing sectors. Also known as price band buffer stock programs , governments would purchase a given quantity of goods at a fixed price, and then sell them for a fixed price such that prices are contained within a band. Though these policies are controversial as they cause inefficiency, research shows that price stabilization for coca, coffee, jute, wool, and wheat is greatly beneficial to its exporting countries. They would generate greater export revenue as well as create a positive pure welfare impact. Some of the poorest developing countries located in West Africa, Latin America, and Asia would be greatly supported by these policies.

While the circumstances of a country emerging from war in 1945 is drastically different from today, concentrating on dominating high and long-term growth industries is a key goal that remains relevant and effective for recovering economies. This will require the cooperation of governments and foreign countries through favorable taxation policies and negotiations that give growing but vulnerable firms an advantage. By identifying a country’s comparative advantage and fulfilling that industry’s potential, a country may be able to experience rapid recovery and growth to birth their own “Economic Miracle.”

Featured Image Source: nippon.com

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the Undergraduate Economics Association, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.

Share this article:

Related Articles

A World Without Coffee: The Story Behind a Possible Impending Coffee Crisis

The Fundamental Problem with US Environmental Policy

Country Garden: There’s No Such Thing as “Too Big to Fail”

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

subscribe to our Monthly Newsletter!

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Reinterpreting the Japanese Economic Miracle

- Robert J. Crawford

A balanced view is emerging that does not sugarcoat the reasons for Japan’s success.

Patrick Smith, Japan: A Reinterpretation, (New York: Pantheon Books, 1997).

- Robert J. Crawford is a writer who specializes in case studies at the graduate level for both business and design schools.

Partner Center

- Get Involved

- Editorial Division

- Research Division

- Academic Division

- Marketing Division

Kavanagh,WC (ug)

January 26th, 2022, the miracle of japanese economic growth after wwii.

Estimated reading time: 5 minutes

As an incoming second-year undergraduate in Politics and History, I am thrilled to join the LSEUPR academic team. My name is Yining Gong, a second-year Politics and History student. Meanwhile, I am also a blogger who posts original articles on political science, political history, and international relations for more than two years. I started my blog in 2019 with several essays discussing the aftermath of the Great War and the formation of the Treaty of Versailles. Other than a series of articles discussing historical topics, my blog went on to explore more controversial issues like the effectiveness of the British Civil Service, the long-lasting Polish Constitutional Crisis, and even the recent Afghanistan evacuation. My personally preferred area of study will be the developmental states in East Asia during the Cold War period, especially in the case of Japan.

The piece of work that I am going to discuss regarding this area of study is not a simple article, but rather a book that provided fresh insight into this controversial topic. As many should already have heard or even read about this well-known and appreciated work, “MITI and the Japanese Miracle: The Growth of Industrial Policy, 1925-1975” offered a unique, and later dominating explanation for the Japanese economic miracle after the Second World War. The book consists of 9 chapters, which are then composed in two distinctive writing styles. Chapters 1, 2, and 9 provides an analytical writing style to assess the economic bureaucracy that had existed within the Japanese government since the 1920s. Through these examinations, Johnson explains what sets the Japanese model apart from the rest of the world. The other 6 chapters provided a detailed narrative of the history and identities of MITI: Ministry of International Trade and Industry.

These 6 chapters convey the book’s essential message to the readers, in which he pressed the importance to understand how bureaucratic factions had always influenced the decision-making process around Japan’s economic policy. The MCI (Ministry of Commerce and Industry) that dated to pre-WWII days and its transformation into MITI had been stressed. Furthermore, it was made clear to the readers about the inherent conflict during almost every decision-making process within MITI. This description altered people’s imagination of a consensual Japan. Moreover, a thorough discussion about MITI’s power would reveal that it hold a combination of legal authority, foreign exchange controls, taxation policies, and the capacity to wield several other monetary and fiscal policies.

Perhaps the most important message Johnson incorporated in this book is the analysation of the differences between the United States’ economy and that in Japan. While saying that the United States and a large part of the world are conforming to a “regulatory” system, which means that the free market is the most essential actor in these countries’ economic environment. The governments, or the central authorities, merely plays a regulatory role to keep a fair, open, and competitive market running. Private firms are left alone under these circumstances and governmental interference would only occur when the freedom of the market is threatened or weakened. Whereas in Japan, Johnson argued that there existed a “developmental government”. Instead of being an objective observer to the free market, the Japanese government actively participated in the development of private firms through measures carried out by MITI. The MITI was the key actor to devise and direct the direction of national economic expansion and layout the grand blueprint for Japan’s development trajectory.

Johnson explained this shocking difference through several historical reasons:

- Since the late 19th century, Japan had emphasized national economic security

- Government has close relationships with zaibatsu (financial clique): Mitsui, Mitsubishi, Sumimoto, and Yasuda

- Heavy industrialization since the 1890s to supply munitions and ships marked precedence of state-directed development

- Use of FDI (Foreign Direct Investment) to stimulate import substitution

- In the 1930s, MCI supported greater state control to develop a war economy

These historical factors have made it easy for the MITI to introduce similar state-controlled directions over the national economy. It controlled imports, technical transfers, and international capital movement in Japan, and used its “developmental bank loans” to subsidize and facilitate the growth of certain industrial sectors that is deemed a priority. Though MITI’s power was gradually reduced over time, the developmental bank loans remained its main tool to choose growth industries and provides administrative guidance to private firms in these industries.

As Johnson emphasized, readers should not mistake the Japanese developmental state with the socialist planned economy. Under the developmental state model, government permits the existence of free competition. Various companies that emerged during the post-WWII period like Sony furtherfurther proved this statement. For the developmental state model to work, it is essential that the private commercial companies in various specific industries are willing to cooperate with the government, and accept the administrative guidance provided by the MITI.

“MITI and the Japanese Miracle: The Growth of Industrial Policy, 1925-1975” is the first systematic study in the United States to analyze the causes of the Japanese economic miracle after the Second World War. In the 1950s and 1960s, the orthodox interpretation among the United States historians is that Japan’s success is a result of the U.S. occupation and continuous support during the late 1940s and early 1950s. This opinion was related to figures like Edwin Reischauer and Marius Jansen. They believed that Japan was an example of the U.S. modernization theory. While admitting that the nuclear umbrella provided by the U.S. had allowed Japan to catch the “free ride” and devote its resources to economic development, Johnson coined the term “developmental state” and provided a novel insight into how the Japanese government guided and cooperated with the private businesses to achieve their economic miracle. Although this work is bound to be controversial since it is difficult to account for the Japanese economic success with one theory, this work serves as one of the best studies into the Japanese economic model and its bureaucrat-business relationship

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

About the author

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Related Posts

Research Amidst Volatility: Measuring GDP in a Pandemic

February 15th, 2022.

November 29th, 2021

The Indian Citizenship (Amendment) Act 2019, Vis-à-vis The Assam Accord: A Political Legal Commentary

December 10th, 2021.

Recruiting in a digital age: pitfalls and strategies for automated hiring

March 26th, 2021, top posts & pages.

- Is Mill’s principle of Liberty compatible with his Utilitarianism?

- The Need for Absolute Sovereignty: How Peace is Envisaged in Hobbes’ Leviathan

- Orientalism: in review

- Globalisation and State Sovereignty: A Mixed Bag

Postwar Japan: From the Economic Miracle to the Bubble Economy

Cite this chapter.

- John Marangos

341 Accesses

The Japanese economy was once one of the most successful in the world. A small country scattered over four major islands with little arable land (less than 20 percent) and a mountainous terrain. Japan has to import much of its food and nearly all of its energy.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

References and Further Reading

Angresano, J., (1996), Comparative Economics, Second Edition , Pearson, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

Google Scholar

Anonymous, (1994), “The Secrets of Japan’s Safe Streets,” The Economist , April 16–22.

Austin, G. and S. Harris, (2001), Japan and Greater China. Political Economy and Military Power in the Asian Century , University of Hawaii, Honolulu.

Cobet, A. E. and G. A. Wilson, (2002), “Comparing 50 Years of Labor Productivity in the U.S. and Foreign Manufacturing,” Monthly Labor Review , 125(6), 51–65.

Freedman, C., (1999), Why Did Japan Stumble?: Causes and Cures , Macquarie University. Centre for Japanese Economic Studies, Edward Elgar.

Gao, B., (2001), Japan’s Economic Dilemma , Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Book Google Scholar

Gardner, H. S., (1998), Comparative Economic Systems, Second Edition , The Dryden Press, Fort Worth, TX.

Gregory, R. and R. Stuart, (2004), Comparing Economic Systems in the Twenty-First Century , Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston.

Hoshi, T. and A. K. Kashyap, (2004), “Japan’s Financial Crisis and Economic Stagnation,” Journal of Economic Perspectives , 18(1), 3–26.

Article Google Scholar

Hutchison, M. M. and F. Westermann, (2006), Japan’s Great Stagnation Financial and Monetary Lessons for Advanced Economies , MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Katz, R., (2003), Japanese Phoenix: The Long Road to Economic Revival , East Gate Book, New York City.

Kennett, D., (2004), A New View of Comparative Economics , South-Western, Mason, Ohio.

Kingston, J., (2013), Contemporary Japan: History, Politics, and Social Change since the 1980s, Second edition , Backwell Publishing, Chichester, West Sussex.

Maswood, S. J., (2002), Japan in Crisis , Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

McCargo, D., (2000), Contemporary Japan , Palgrave Macmillan New York City.

Miyashita, K. and D. Russell, (1995), Keiretsu: Inside the Hidden Japanese Conglomerates , New York: McGraw-Hill.

OECD, (1996), Economic Surveys of Japan, 1995–96 , OECD, Paris.

Posen, A. S., (1998), Restoring Japan’s Economic Growth , Institute for International Economics, Washington, D.C.

Rosser, J. B. and M. V. Rosser, (2004), Comparative Economics in a Transforming World Economy , MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Schnitzer, M. C., (2000), Comparative Economic Systems, 8th Edition , South-Western Publishing Com Singapore.

Smith, D. B., (1995), Japan since 1945: The Rise of an Economic Superpower , St. Martin’s Press, New York City.

Tabb, W. K., (1995), The Postwar Japanese System , Oxford University Press, New York City.

United Nations Development Program, (1995), Human Development Report 1995 , Oxford University Press, New York City.

Vogel, K. S., (2006), Japan Remodeled- How Government and Industry Are Reforming Japanese Capitalism , Cornell University Press, Ithaca.

Wall Street Journal , (1990), January 9, pp. 1.

World Bank, (1997), World Development Report 1997: The State in a Changing World , Oxford University Press, New York.

Download references

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Copyright information

© 2013 John Marangos

About this chapter

Marangos, J. (2013). Postwar Japan: From the Economic Miracle to the Bubble Economy. In: Consistency and Viability of Capitalist Economic Systems. Palgrave Macmillan, New York. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137080875_5

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137080875_5

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Print ISBN : 978-1-349-29303-2

Online ISBN : 978-1-137-08087-5

eBook Packages : Palgrave Economics & Finance Collection Economics and Finance (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- AsianStudies.org

- Annual Conference

- EAA Articles

- 2025 Annual Conference March 13-16, 2025

- AAS Community Forum Log In and Participate

Education About Asia: Online Archives

The japanese economy in us eyes: from model to lesson.

Japan’s meteoric rise from the ashes of World War II has been described by many as an economic miracle. Between 1960 and 1985, real income per person in Japan grew three times as fast as in the U.S. Remarkably, with few natural resources of its own, the Japanese economy became second in size only to the United States without creating serious inequality of income and wealth among its citizens. Indeed, of all industrialized countries, Japan has the most equal distribution of income.

Many of us grew up with newspaper and magazine stories about the technological wonders of Japan in the 1970s and the managerial and economic wonders of the Japanese corporations in the 198 0s. It was a surprise to learn that a part of Japan’s postwar economic miracle might have been a bubble that burst in the 1990s. While the sharp drop in land and stock prices 1 has been singled out as the chief source of the ensuing recession, the slow and sputtering economic recovery and declining productivity growth suggest that the collapse of the real estate and stock markets may have been mere symptoms, not causes, of the problem. Many experts now believe that the Japanese economy needs structural overhaul before it can be expected to resume sustained, long-term economic growth. 2

In his superb book, Frederick L. Schodt sketches the development of four American views of Japan: friend, foe, model, and mirror. 3 In the 1970s and 1980s, Japan served as a model for other aspiring countries in Asia. However, in the nineties, a fifth view of Japan as a “lesson” is emerging. The “lesson,” as the Japanese are painfully discovering, is that economic institutions and policies that worked so well to enable the country to catch up to the Western industrialized countries might not work very well when the country has caught up to, and in many cases leap-frogged past, its competitors.

THE JAPANESE POSTWAR ECONOMIC MODEL

Professor Takatoshi Ito of Hitotsubashi University recently identified several key policies and institutional features of the Japanese economy which he believes contributed to Japan’s rapid economic growth in the post-World War II period. 4

INDUSTRIAL POLICY— During the 1950s and 1960s, the Japanese government picked certain “sunrise” industries thought to be potential winners in the global economic race and helped them through low-interest loans and allocation of scarce foreign exchange so they could import what they needed. Pushing exports lay at the heart of this so-called “industrial policy” to promote economic development. The government protected the producers in these favored industries by restricting domestic competition and by raising tariff and quota barriers to keep imports out. Given breathing room to learn and become efficient, these favored infant industries were supposed to grow into world-class competitors and then be weaned from government protection. Import restrictions would then be reduced and Japanese domestic markets opened to foreign goods.

Whether this policy of nurturing selected industries to become winners achieved the goal of accelerating Japanese economic growth is still being researched and debated. We do know that during this high-growth period the composition of Japanese exports changed rapidly from low-quality, cheap goods such as textiles and toys in the 1950s to world-class quality automobiles and semiconductors in the 1980s. Japan sold far more goods abroad than it imported and accumulated persistent and large annual trade surpluses.

H IGH H OUSEHOLD S AVINGS R ATE — A high rate of household savings financed Japan’s economic growth. Between 1960 and 1994, Japanese households saved about one-sixth of their after-tax incomes, more than twice that of American households. One popular theory attributes Japan’s high household savings rate to culture, tradition, or national character. However, the fact that Japan’s household savings rate was not always high (it was neg ative before World War II) suggests that culture is not the principal explanation.

The country’s high rates of economic growth in the postwar period, government programs and tax breaks to promote savings, lack of consumer credit to buy big-ticket items such as homes, household furniture and appliances, and low level of social security benefits until the early 1970s are some of the reasons why Japanese have saved so much more of their incomes than Americans. Japan’s high savings rate has been a major contributor to its high rate of investment to create productive capacity. It also financed direct and indirect investment abroad, including in the U.S.

E DUCATION AND L ITERACY — Japan has one of the highest literacy rates in the world. The Ministry of Education tightly oversees an egalitarian primary and lower secondary public education system by exercising its broad authority over school curriculum, teaching manuals, and textbooks. Admission to coveted schools, from primary through college levels, is determined by competitive entrance examinations. Although students in Japan are only required to go to school through the ninth grade (i.e., junior high school), 95 percent of them now continue on to high school (compared to only 58 percent in 1960). This is among the highest rate of high school attendance in the world.

Until recently, Japanese children went to school six days per week; Saturday morning classes have been cut back to twice monthly. Compared to students in the U.S., Japanese (and other Asian) students score high in literacy, standardized mathematics, and science tests. About 44 percent of male and 48 percent of female Japanese high school graduates go on to higher education. 5 Female students are more likely to go to junior college, while male students overwhelmingly choose to go to four-year universities. Japan’s educated and industrious labor force is an important reason for its postwar economic success.

EMPLOYMENT SECURITY —New graduates leave Japanese schools and universities in March of each year and officially begin their employment in April. Among college graduates, the best and the fortunate, usually from the most prestigious schools, are hired by large, well-established companies or enter civil service and can expect (though not contractually guaranteed) lifetime employment. Lifetime employment essentially means that a new employee is expected to work for the same company until he retires. Smaller companies do not offer the assurance of long-term employment.

The Japanese compensation system is designed to encourage workers to stay with the company. Typically a regular employee’s starting pay is relatively low, but rises rapidly with age and seniority. If the employee quits the company, he may have difficulty finding a comparable job, and even if he does, his pay is likely to be substantially lower than what he left behind. There would also be a huge reduction in his future lump sum retirement payment if he changes employers.

Thus, the steep age-wage profile in Japan encourages the worker to work hard, improve his skills, demonstrate unquestioned loyalty, and stay with his company. The employer is also more willing to invest in training employees who are expected to stay with the company. As a result, the high level of employment security contributes to the growth of Japanese firms, which in turn enables companies to provide secure employment to their employees.

The Japanese today enjoy a high level and equality of income, little poverty, universal access to health care, and the highest life expectancy in the world.

K EIRETSU AND THE M AIN B ANK S YS TEM — Many businesses in Japan are affiliated with groups called keiretsu . Members of horizontal keiretsu represent diverse businesses, tend to borrow mainly from a primary lender, the main bank, hold one another’s shares, and sometimes exchange personnel. The president, chief executives, and directors of the core corporations meet monthly. Well known companies such as Mitsubishi Bank, Mitsubishi Corporation, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, and Mitsubishi Motors are all affiliated companies that belong to one of six major horizontal keiretsu in Japan. In the vertical keiretsu , member firms are linked through the supply and distribution chains of a major manufacturer—its core firm. Toyota, the well-known automobile manufacturer, is an example of this type of keiretsu . Japanese automobile manufacturers, like Toyota, produce only about 20 percent of the parts they use in-house and buy the rest from parts manufacturers; by contrast, American and European automobile manufacturers produce about 50 percent of the parts they use. 6 Toyota itself belongs to a major horizontal keiretsu with Mitsui as its main bank. 7

Horizontal keiretsu permit the main bank to gain access to detailed insider information, use it to monitor the member firms, and to influence their policies. Outsiders also may rely on monitoring by the main bank, and invest in these companies without incurring investigative costs of their own. Membership within a (vertical) keiretsu facilitates technology transfers among member firms. Keiretsu members may also assist other members in financial distress by providing preferential loans, prices, and buying their products. For example, Sumitomo Bank extended substantial credit and sent some key bank personnel to advise the troubled Mazda automobile company. Mutual shareholdings protect member firms from hostile takeovers, so they can focus on longterm strategies instead of short-term profitability. This longer term focus has frequently been cited as a competitive advantage of Japanese corporations.

UNBALANCED PROGRESS

The Japanese today enjoy a high level and equality of income, little poverty, universal access to health care, and the highest life expectancy in the world. Compared to Americans, the Japanese also have lower crime, unemployment, and divorce rates, lower infant mortality, fewer teenage pregnancies, and lower drug addiction.

However, in many aspects of their daily lives, the Japanese do not live as well as Americans. Japanese workers take fewer days of vacation each year and spend more time commuting to and from work. Until a few years ago, Japanese manufacturing production employees worked more hours per year than Americans. However, a sharp drop in hours worked in Japan and a smaller rise in the U.S. since the early nineties has reversed this relationship. 8

Except for its excellent system of public transportation, Japan lags behind the U.S. in roads, ports, airports, sewage treatment, parks, and other social infrastructure. Japanese consumers face higher domestic prices than those in the rest of the world. Japan’s Economic Planning Agency (EPA) estimates that in 1996 prices of goods and services in Tokyo were 33 percent higher than in New York, 28 percent higher than in London, 19 percent higher than in Paris, 24 percent higher than in Berlin, but 8 percent lower than in Geneva. Housing is cramped and expensive. Food, even rice—the staple of Japanese diet—is more expensive than in the U.S. 9

Although Japan is one of the leading industrial countries in the world, Japanese economic policies continue to favor businesses at the expense of consumers. For example, in the financial sector banks were expected to support industry by lending to and investing in Japanese corporations; they were not encouraged to provide consumer loans or other consumer services.

The Bank of Japan gave low interest money to banks to lend to businesses, and used its “window guidance” as a form of moral suasion to get the banks to comply with government policy. Even as capital controls were relaxed, bank services for consumers remain poor. Commercial banks offer checking accounts to businesses but not to individuals (except a few very wealthy individuals). Until very recently, bank ATM machines closed around 7 p.m. and are only open for limited hours on Saturdays. 10 Compared to American banks, Japanese banks have shorter business hours (9:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m., Monday-Friday) and are not open on weekends.

Japan’s postwar industrial policy requires close coordination between government and businesses. This coordination function is relegated to powerful bureaucrats who staff government ministries. Retired high-level government bureaucrats typically end up working for the same corporations that they were previously assigned to monitor. This cozy relationship provides a fertile environment for bribery and corruption, and hurts Japanese consumers. The early 1998 resignations of high-level Ministry of Finance officials (who allegedly tipped off banks on forthcoming surprise inspections in exchange for bribes) should come as no surprise.

Even though Japan has antimonopoly laws, price-fixing and market-sharing among businesses are still tolerated by the government. As a result, Japanese firms prefer not to compete on the basis of price. American visitors traveling in Japan may find it curious that prices at vending machines, movie theatres, and taxicabs are remarkably uniform across the country.

Despite an egalitarian income distribution and a narrow wage gap between top-level managers and rank-and-file employees, Japan remains a hierarchical society in many areas of everyday socioeconomic relationships.

Women, the elderly, and ethnic minorities in Japan face widespread employment discrimination. Employment advertisements routinely specify age limits for job openings; and most employees are required by their employers to retire between the ages of 55 and 60. The average wage of female workers is only 62 percent of the average male wage in Japan, compared to 71 percent in the U.S. Forty-six percent of the women polled recently replied that their companies pushed women to quit when they became pregnant or after they gave birth. Japan’s Labor Standards Law contains a female “protective provision” that restricts overtime, night shift, and holiday work for women. 11

Don’t bother to look for wheelchair-accessible buses, trains, and public bathrooms, or wheelchair ramps in public buildings and sidewalks; you are not likely to find any.

Why have Japanese workers and consumers tolerated high consumer prices, poor housing conditions and social infrastructure, long work commutes, and demanding employers? Perhaps they were willing to accept these negative side effects of the Japanese “model” in exchange for rising incomes and job security. After the war, the government, businesses, and workers shared a single-minded vision to attain economic parity with the West and worked cooperatively to achieve rapid economic growth. Having achieved affluence, Japan is reassessing the real costs of its past policies and institutions.

Winds of change are blowing hard in Japan. Clearly, a catch-up model is inappropriate for a country that has already caught up.

PUBLIC RELATIONS ABROAD

The postwar economic success of Japan has not come without political and public relations costs abroad. Japan’s persistent trade surplus has been a source of resentment and trade conflict between Japan and its international trading partners. Until the early 1980s, frictions arose over mounting Japanese exports and allegations that Japanese manufacturers often sold their goods abroad too cheaply. 12

Since the 1980s, most of the disputes have focused on foreign access to Japanese markets. Foreign companies see high Japanese domestic prices as opportunities to penetrate Japanese markets and eventually to lower Japanese prices. This has not happened largely because of import restrictions, government regulations that protect high cost domestic producers, and in some cases, even long standing Japanese business practices. In recent years, the keiretsu has come under criticism by outsiders as a source of economic exclusion. Japanese counter-argument has been that many foreign companies (such as Coca Cola, Proctor & Gamble, and Revlon) that made a serious attempt to enter the Japanese market have prospered in Japan.

Yet, a poll conducted in 1995 by Yomiuri Shimbun/Gallup Organization revealed that many American, British, German and French adults regard Japan not only as a major economic power, but also as a “closed” society that does not inspire trust among them (Table 1).

THE LESSONS OF THE 1990S

The policies and institutions that apparently worked so well for Japan during the high growth period are not working as well in the current environment of slow economic growth. 13 Many businesses in Japan are finding it harder not to lay off or terminate workers. The institution of life-time employment is beginning to fray at the edges at least. Increasingly, companies are hiring contract and part-time workers instead of regular workers. Employers are beginning to adopt merit pay instead of compensation based on seniority. Many firms are under pressure to cut their costs.

One wonders how long it would be before employers begin to demand that Japanese universities and colleges do more than screening for talent and do a better job of training their students before they graduate. Japanese universities are tough to get into; but once admitted, most students in humanities and social sciences do little studying and learning, expecting their employers to incur the time and expense of training them on the job.

The economic power of main banks is on the decline. As government regulations on capital controls, corporate bond issues, and new stock offerings are dismantled, Japanese corporations can borrow money directly in domestic and overseas financial markets and no longer have to rely on the main banks for capital. In April 1998, Japan began broad financial deregulation of its banking, brokerage and insurance industries (dubbed the “Big Bang”). There is also growing public pressure on the government to privatize the Postal Savings Bank, Japan’s largest “bank.”

The keiretsu is beginning to show cracks in its armor. As demand declines, the cost of maintaining long-term relationships among member firms has escalated. With sales and profits declining, member companies are not as willing to buy supplies at higher prices from another member company. Thus, the economic glue that held the membership together in the past has weakened as short-run survival gains priority over maintaining long-term relationships. 14

Japanese consumers are less willing to pay exorbitant domestic prices when their wages are not rising and their jobs are not as secure as before. Younger workers earning high nominal incomes today are less interested in being “corporate servants” and in working the marathon hours that their parents used to put in on the job. Most are also not interested in staying with one employer for their lifetime.

Japan’s population is also aging rapidly; by the year 2010, Japan will be the most aged society in the world. As a result, its household savings rate is expected to fall sharply, and there will be less savings to finance investment to fuel future productivity and economic growth. In addition, the aging population will also impose growing healthcare and social welfare costs on society.

Winds of change are blowing hard in Japan. Clearly, a catch-up model is inappropriate for a country that has already caught up. The country needs to set new goals. In the view of many experts, Japan needs to trim unnecessary government regulation and open its markets in order to improve efficiency and productivity that would lower costs and prices and revitalize its economy. The cost of import barriers to Japanese consumers in 1989 was recently estimated at $100 to $110 billion, or 3.6 percent of GNP. 15 Keidanren, the politically influential national organization of major business firms, has placed deregulation at the top of its lobbying agenda.

Americans sometimes express frustration with the seemingly slow pace of Japanese institutional and regulatory reform. However, America’s own experience with deregulation has not been one of fast or even steady progress. For example, deregulation of the U.S. airline industry started in the 1970s and took over a decade. The cable television industry was deregulated, and then re-regulated. In Japan, where decisions are usually based on consensus, change will require even more time.

Economic institutions in Japan, like elsewhere, can be understood as rational responses to historical events. The Japanese have their own history which has shaped their values, expectations, and ways of doing things. Americans should not expect U.S. institutions to be a perfect fit for Japanese conditions. 16 Until Americans learn to appreciate the reasons for their differences, they will continue to be impatient with the pace of Japanese reform. This means that in teaching Americans about Japan, the more we learn about each other’s history and culture, and how each country’s institutions developed into what they are, the less likely we will form stereotypes and offer prescriptions based on our own ethnocentric prejudices. Such a balance in teaching will foster a better understanding of, and fewer surprises, about Japan.

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

1. The Nikkei stock price index has fallen to 40 percent of its peak, and commercial land prices have fallen to around one-third in recent years.

2. For a more pessimistic view of Japan’s ability to transform itself in the coming decades, see Taichi Sakaiya, What Is Japan? Contradictions and Transformations (Translated from Japanese by Steven Karpa). Tokyo: Kodansha Publishing, 1993.

3. Frederik L. Schodt, America and the Four Japans (Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press, 1994).

4. Takatoshi Ito, “Japan’s Economy Needs Structural Change,” Finance and Development, June, 1997, pp. 16–19. While we summarize the main points of Ito’s paper in this section, the descriptions of the institutions are largely taken from the essays in our recent book, James Mak, Shyam Sunder, Shigeyuki Abe, and Kazuhiro Igawa (eds.), Japan: Why It Works, Why It Doesn’t, Economics in Everyday Life (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1998). Twenty-three authors in the U.S. and Japan contributed the twenty-six short essays explaining aspects of everyday life in Japan in economic terms.

5. Monbusho: Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture, Government of Japan, 1997 (Tokyo: Ministry of Education, 1997), 24.

6. NHK , A Bilingual Guide to the Japanese Econo my (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1995), 71.

7. See also, Kenichi Miyashita and David Russell, Keiretsu (New York: McGraw Hill, 1996).

8. See http://www.stat.go.jp/1611m.htm on the Internet and Yoshitaka Fukui in Mak, et al. (1998), 107–8.

9. Japan’s Economic Planning Agency estimates that in 1996 food prices in Tokyo were 45 percent higher than in New York City and 91 percent higher than in St. Louis.

10. The U.S.’s Citibank was the first to offer 24- hour ATM service in Japan. Sumitomo Bank began offering 24-hour ATM service in February, 1998.

11. See Harry Oshima in Mak, et al. (1998, pp. 199–200).

12. The term used was “dumping.”

13. During the decade of the 1980s, the Japanese economy grew at an average annual rate of about 4 percent; by contrast, the average annual rate of growth was less than 2 percent between 1990 and 1997.

14. A recent analysis of data for Mitsubishi group suggests that intra- keiretsu links are much weaker than is widely believed. See Yoshitaka Fukui, Three Essays on Accounting and Reali ty , Chapter 2, Carnegie Mellon University D. Dissertation, 1998.

15. Yoko Sazanami, Shujiro Urata, and Hiroki Kawai, Measuring the Costs of Protection in Japan (Washington D.C.: Institute for International Economics, 1995).

16. For one analyst’s view of why Japanese are slow to deregulate, see Keizo Nagatani, “Japan’s Sagging Credibility: A Crisis of Self Confidence,” Look Japan , vol. 43, no. 504 (March, 1998), 12.

- Latest News

- Join or Renew

- Education About Asia

- Education About Asia Articles

- Asia Shorts Book Series

- Asia Past & Present

- Key Issues in Asian Studies

- Journal of Asian Studies

- The Bibliography of Asian Studies

- AAS-Gale Fellowship

- Council Grants

- Book Prizes

- Graduate Student Paper Prizes

- Distinguished Contributions to Asian Studies Award

- First Book Subvention Program

- External Grants & Fellowships

- AAS Career Center

- Asian Studies Programs & Centers

- Study Abroad Programs

- Language Database

- Conferences & Events

- #AsiaNow Blog

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Japan and the Asian Economies: A "Miracle" in Transition

1996, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity

Related Papers

Sudha Menon

The spectacular growth of economies in Asia over the past few years has amazed the economics profession and has evoked a torrent of books and articles attempting to explain the phenomenon. Since 1960 Asia, the largest and most populous of the continents has become richer faster than any other region of the world. Asian growth, like that of the Soviet Union in its high-growth era, seems to be driven by extraordinary growth in inputs like labor and capital rather than by gains in efficiency. Of course, this growth has not occurred at the same pace all over the continent. The eastern countries turned in a superior performance, although variations in achievement can be observed here too. This impressive achievement is, however, still modest compared with the phenomenal growth of Developed countries in the west. Strong Total Factor Productivity [TFP] rapid accumulation of physical and Human Capital and trade policy coupled with effective policy intervention played vital role in Asia’s sp...

Munyurwa Alain Pax

Keith Jackson

A review essay that describes and examines processes and measures of economic 'growth' across Asia, taking Japan as its focus. The importance of national institutional contexts rather than 'national cultures' is emphasized.

Vinod Thomas

Robin Grier

Ejesha Ejesh

Southeast Asian Economies

The East Asian Miracle, A World Bank Policy Report

Hilton L . Root

Andrés Felipe Gómez

Jose Gregorio

RELATED PAPERS

Alfa : Revista de Linguística (São José do Rio Preto)

Mariangela Rios de Oliveira

Revista Colombiana De Gastroenterologia

Yolette Martinez

José Falcão Sobrinho

Agronomia: Jornadas Científicas - Volume 2

LORENA BATISTA DE MOURA

Nucleic acids research

Rafał Łętocha

Public Administration Review

Curtis Ventriss

Victor Tsetlin

Revista Tempo e Argumento

Marilda Marques

Cancer/Radiothérapie

Angelica TIOTIU

Expert Systems with Applications

Lidia Alonso-Nanclares

Carlos Mario Mazo Marin

Berengere Fromy

Salim Hiziroglu

Clinical Cancer Research

Vincent Bonagura

Revista Relayn - Micro y Pequeñas empresas en Latinoamérica

Jorge Cuevas Sosa

Physical Review Letters

B. Van Tiggelen

Western Journal of Medicine

vincent figueredo

Human Resources for Health

Immunopharmacology

Mohamed BIDRI

European Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology

Ghalib Ahmed

International Journal of Secondary Metabolite

Yavuz Bağcı

International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control

Ardi Hartono

Food Hydrocolloids

Javier Borderías

Springer eBooks

Peter Moorer

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Japanese Economy: The Lost Decade Essay

Introduction, main body one, main body two, reference list.

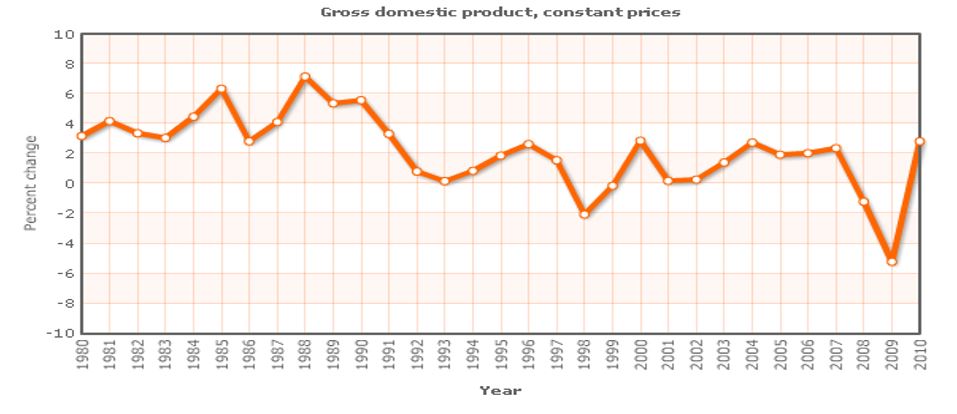

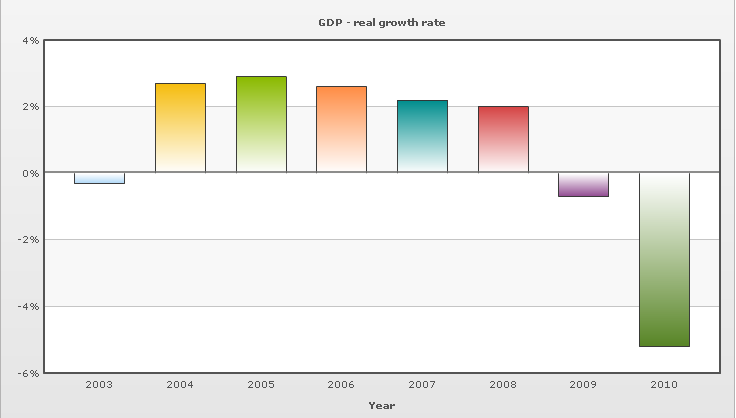

The economy of Japan is considered the most controversial still a rather captivating and educative aspect of Japanese development. Japanese achievements are not that higher in comparison to those of the United States of America and China, still, the history of Japanese economic development has to be considered. According to Teranishi (2005), the economy of this particular country has become noticeable due to “various Japanese-style properties: a firm system based on seniority wages and life-time employment, a bank-dominated financial system with an active role for main banks, heavy government involvement through industrial policy” (p.3). There are three main periods in the history of theJapanese economy after the World War Second: the time when “the Japanese economy lay in total ruin” (Maswood 2002, p. 1), the “economic miracle” (Kopstein & Lichbach 2005), and the lost decade that is known as the period of considerable economic slowdown with numerous inability to take the control over the banks’ actions. The changes which are observed with the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) to predetermine the economic well-being help to realize how significant each period for Japan was. In the Table One, the graph of how GDP varied during the period between the 1980s and the 2010s aims at showing how dramatic the changes could be: unbelievably high rates were observed in 1988 as a result of the post-war miracle that contained effective cooperation of distributors, manufacturers, and banks, numerous unions of powerful enterprises, and lifetime employment and gradual decline that was inherent to 1998 due to the already supported ideas of bank speculations and inabilities to cope with massive borrowings. However, the results achieved tin 2009 prove that the slowdown observed in 1998 was not the most terrible period in Japanese economy.

This is why it is very important to evaluate and to understand the essence of the idea offered by Klingner & Scissors (2009) who admitted that to call the period of 1990s as the lost decade in Japan “is a mistake – the loss has extended well beyond the 1990s. The economy is now smaller than it was the first quarter of 1991, so Japan is actually approaching its second lost decade”. Of course, it is important to choose the steps and make everything possible to overcome the current crisis. However, it is also necessary to realize how to support the recovery for some period of time and overcome the challenges the way they will never bother the country in the nearest future. Japan introduces the example of how radical steps may negatively influence the development of the country’s economy.

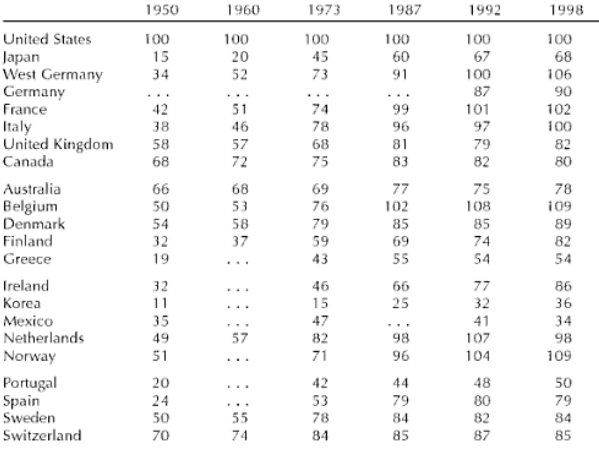

In comparison to other countries which may compete with Japan to take the leading position, it is necessary to define the United States as the world leader and China as the Asian leader. As Teranishi (2005) pointed out that “the Japanese economy experienced a relatively high rate of economic growth, as evidenced by an increasing share of world GDP” for a long period of time (p.11). In Table Two, it is possible to observe the rates of Japan GDP as well as the rates of different countries during more than a century. These calculations show that Japan is one of the countries that did not take some catastrophic and unpredictable steps. Their rates are always gradually arranged:

In fact, it is evident that the ‘lost decade’ expanded considerably during the last years, and it is difficult to define its boundaries. This is why it seems to be effective to investigate the macroeconomic and microeconomic aspects over the last decade and explain the essence of structural and monetary activities taken by the Japanese representatives to save their economic sphere and gain benefits from their investments. Japan has evaluated the conditions under which it has to be developed and found out that certain changes have to be made on a microeconomic basis: the implementation of the structural reform should lead to numerous benefits which help to revitalize the Japanese economy, to enhance the growth, and to secure the desired recovery within the shortest periods of time. In spite of the fact that the Japanese economy remains to struggle with the structural reforms which are dated from the beginning of the 1990s, the existed deflationary gap becomes an intrinsic dilemma in the economic order. As Gao (2001) says the chosen economic dilemma has to reveal the mechanism with the help of which the institutional change and some kind of exogenous shock may be linked logically.

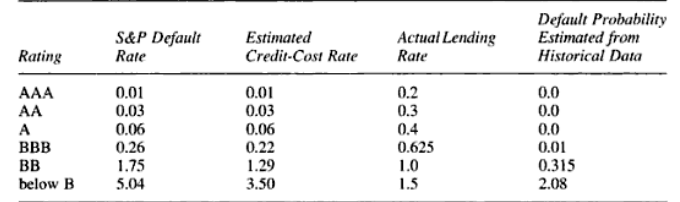

Numerous microeconomic activities in Japan are usually based on the reforms which aim at improving the productivity and changing the structural aspect of the economy (Sato 1999). Japan as many other countries like the USA, the UK, or even Australia made an attempt to rely on the best practice microeconomic policy and open up different markets to competitions with the help of which the process of restructuring could be possible. The example of the most successful structural reform was offered by Lin in 2005. The ideas introduced were based on the possible cooperation between the American and Japanese representatives in the form of an interior equilibrium (Lin 2005). This equilibrium is formed by means of the weakest keiretsu that are the banks, manufacturers, and distributors which have been united during the period of the Japanese economical miracle united in order to improve the economy (Australian Government 2005). In the Table Three, the results show that banks of different levels underwent considerable changes during the post-war period, and the actual lending rates which are based on the borrowings offered are not stable.

Numerous keiretsu unions are able to ensure the collaborations to invest in the development of the Japanese economy. Still, they are not powerful enough to provide the member with long-term profitability (Kim 1998), this is why it is necessary to make use of the main bank that has governmental support as well as a good reputation on the world market.

To struggle with the structural problems, Japan should also evaluate overseas markets in order to compensate for the necessary amount of domestic industries. Export and import of Japan were small during the ‘lost decade’, and it was obligatory to increase the rates of trade both export and import. And it is possible only in case of transformation of the industry and the structure of the trade in order to become more reliant. It is not enough to focus on the automobile or electronic industry that is popular in Asian and European countries. However, the improvement of cosmetic, food and sundries manufacturing will be more appreciated by the competitors.

To understand better the essence of the economic problems and choose the most appropriate steps, it is crucially important to realize the reasons and the challenges which made Japan neglect the success of the bubble-driving miracle, be overwhelmed with the speculations as well as suffer because of stagnation. The observations made by Dasgupta (2009) help to understand that the period of ‘lost decade’ is considered to be an economic as well as socio-cultural change in Japanese history, this is why the changes and difficulties should be evaluated from all these three perspectives. Collective socio-cultural anxiety is one of the reasons why Japan could not continue its economic development during the 1990s. At the beginning of the 1990s, Japan lost its national confidence; this is why certain shifts took place. In addition to personal uncertainty, Japan has to solve the challenges which came from the United States. “America’s comeback was bound up with an orthodox economic strategy of fiscal prudence and continued economic openness, reinforcing central premises of the tree traders” (Kunkel 2003, p. 193). Constant American involvement in Japanese economic activities prevented the required development and improvement of the conditions under which the lost decade was able to develop considerably. It was hard to control the financial activities which predetermined the relations between different keiretsu as well as between the international potential partners. It was clear that some American demands could not be understood and considered by the Japanese representatives, still, it was defined that American pressure may lead to the required success and productivity. “With Japan no longer much of an economic competitor and the U.S. also grappling with the financial crisis, Tokyo could offer reciprocal proposals with some chance of seeing them accepted by Washington” (Klingner & Scissors 2009). In other words, the American push may be of formal or informal nature in order to reduce the dependence of the Japanese economy on the weak export and focus on the domestic economy.

Still, the investigations show that American impact on different countries remains to be a serious challenge for such OECD countries like Japan. Even if Japan takes first place among other countries evaluating the productivity levels, the manufacturing levels remain to be smaller. The potential impact of structural reforms on productivity growth is not easy due to the problems with the regulations on the economic performance from America’s side. Still, a number of attempts have been already made to support the economic development; though the results are a little bit sensitive (Callen, Ostry, & International Monetary Fund 2003), Table Four shows that Japanese attempts are still the most successful.

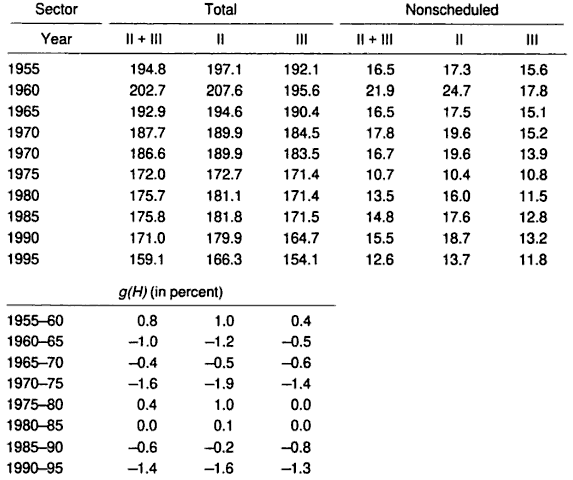

Microeconomic reforms taken during the lost decade to improve the conditions got were usually directed towards considerable improvement of living standards. The way of how this improvement could be achieved was closely connected to the increasing of productivity and efficiency and some macroeconomic impacts which have to be admitted. During the 1990s, Japanese account deficit and growing debts due to constant borrowings attract attention. Many people truly believed that microeconomic reforms will reduce the deficit spreading over the county. Taking into consideration the changes which took place with the Japanese banks and corporations at the microeconomic level, it was important to take the steps which could improve the conditions from the inside at the macroeconomic level. This is why in addition to the outside structural changes; the decision to change the working conditions was made. Macroeconomics is the field that deals with the economic behaviour, and the change of Gross National Product is usually predetermined by the changes in employment and working conditions. Microeconomic change based on working hours may lead to the desirable changes of macroeconomic policy, this is why much attention was paid to the working hours. Sato (1999) admits that “when the slow growth period started, hours declined to around 175 hours per month or 2,100 per year” (p. 35); and before that period, working hours were about 200.

The chosen reform should make some Japanese tradeable industries more competitive: costs were reduced, workers’ needs were met so that they were inspired enough to offer more brilliant ideas for improvement.

Unfortunately, it seemed to be very difficult for the government that has a significant portion of control to take the steps and improve the macroeconomic policies such as monetary and fiscal reforms (Itoh 2010). The point is that the Japanese people will hardly allow some uncontrolled tax increase in case they are not confident in the possibilities of their government to cut down all wastes sufficiently. This is why the government should create a proper plan to encourage fiscal restructuring and to promote long-term sustainability that will touch upon all aspects of the Japanese economy. Such confidence is required to promote appropriate recovery as well as support the country after the recovery is successfully passed.

At the beginning of the 1990s, the makers of macroeconomic policies in Japan underwent certain challenges which have domestic and international origins. Japanese fiscal policy was characterized by numerous economic weaknesses caused by passivity and the desire to avoid risks within a short period of time. However, Japanese indecision in the economic field deprives this country of making some decisions independently. This process is based on the investors’ opinions who find the way and remain to be large shareholders (Cohen 2001). Grimes (2001) admits that “Japan’s macroeconomic pathologies have included an excessive reliance on monetary policy to solve large-scale macroeconomic problems and an extreme aversion to loosening fiscal policy”, and it is very important to underline that all “these pathologies were not the result of incompetence or corruption on the part of policymakers; rather, they were structural in nature” (p. xviii).

The last decade was rather educative for Japanese economic policymakers. First, their mistakes made them re-evaluate their possibilities and their relations with different countries. What the Bank of Japan did was wait until it was too late to take some steps and improve the situation about the incipient deflation problems (Siebert 2004). The results of such inabilities to evaluate the current conditions and learn from the activities taken and the mistakes made were expected: the real growth rate decreased considerably within a short period of time. In Table Six, a dramatic fall may be observed.

Taking into account the results identified and the conditions under which the Japanese people have to live today Flath (2005) and some other researchers are bothered with one and the same question: whether such mistaken macroeconomic policies did cause the mess. Well, it is true that fiscal policy and the changes within it may cause fluctuations in aggregate demand that leads to recessions. It becomes clear from the following example how aggregate demand may be changed: interest rates are bid up, and citizens are not that interested to be enriched by means of non-interest-bearing money (Flath 2005). And such ignorance of money-making results in a significant increase in aggregate demand. And in case the interest rate falls suddenly, the desire to hold wealth in the money form increases, and aggregate demand decreases. And the Japanese government failed to act quickly as soon as the Bank of Japan got into trouble: disclosure of loan problems should gain priorities to define the correct measurements (Matsuda 2000).

In general, the lost decade in Japan serves as one of the most educative and captivating period to deal with. A number of macroeconomic and microeconomic policy-making processes are observed, and the purpose of each policy is unique. Still, all of them aim at improving the economic situation of the country and identifying the weaknesses which prevent the development. The nature of the lost decade is rather clear: after a considerably growth in numerous spheres at the same time, the Japanese people believed that they had huge powers and the banks believed in their abilities to provide many people with the required economic support and financial aid. However, the banks failed to protect the economic bubble developed, and the result was evident: the termination of the bubble and the huge crash in stock markets. It was not enough for the country to choose the most effective steps and take all of them quickly. It was much more important to take the leading position in the world arena and make other countries admit the power of Japan economy. And the Japanese people made a decision to enrich themselves due to the existed low interest rates and huge land values; and as a result of such actions, a number of borrowings were taken at the expense of foreign stocks and the banks had to under the governmental control. Taking into consideration the borrowings offered, it was hard to overcome the debt crisis: banks became unable to cope with the borrowings, this is why they was obliged to bailed out by the Japanese government. The outcomes were evident: rise of unemployment, necessity to take reforms, and change of working hours. People were in need of some changes to understand their worth and to realize their abilities, and the period called the lost decade was the time when it was obligatory to identify the changes and the needs of the Japanese people. The way of how the Japanese government was able to react to the crisis was all about the revival of growth. The activities chosen by different organizations such as investments and money-making by means of interest rate are the most successful examples of how policymakers may improve the situation. The structural reforms are taken, numerous deregulations and resolutions of the financial crisis are considered to be important elements of the period under discussion. These ideas help to remove the obstacles and cope with the challenges which are usually based on economic globalization. It is difficult to avoid the economic challenges from time to time, still, it is always possible to choose the most effective approaches and take them into account each time the innovation or reform is offered.

Callen, T, Ostry, JD, & International Monetary Fund 2003, Japan’s Lost Decade: Policies for Economic Revival . International Monetary Fund, Washington.

‘Changing Corporate Asia: What Business Needs to Know’, 2005, Australian Government: Department of Foreign Affairs Trade . Chapter 6: Japan. Web.

Cohen, SI 2001, Microeconomic Policy . Routledge, New York.

Dasgupta, R 2009, ‘The Lost Decade of the 1990s and Shifting Masculinities in Japan’, Culture, Society, and Masculinities , vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 79-95.

Flath, D 2005, The Japanese Economy . Oxford University Press, New York.

Gao, B 2001, Japan’s Economic Dilemma: The Institutional Origins of Prosperity and Stagnation . Cambridge University Press, New York.

Grimes, WW 2001, Unmaking the Japanese Miracle: Macroeconomic Politics, 1985-2000. Cornell University Press, New York.

Itoh, M 2010, ‘The Japanese Economy: Tackling Structural Problems’, East Asia Forum . Web.

‘Japan GDP: Real Growth Rate’, 2010, Index Mundi . Web.

Kim, AK 1998, ‘A Test of the Two-Tier Corporative Governance Structure: The Case of Japanese Keiretsu’, Mark Journal of Financial Research , vol. 21.

Klingner, B & Scissors, D 2009, ‘Japan’s Economic Weakness: A Security Problem for America’, The Heritage Foundation . Web.

Kopstein, J & Lichbach, MI 2005, Comparative Politics: Interests, Identities, and Institutions in a Changing Global Order. Cambridge University Press, New York.

Kunkel,J 2003, America’s Trade Policy Towards Japan: Demanding Results . Routledge, New York.

Lin, C 2005, ‘The Transition of the Japanese Keiretsu in the Changing Economy’, Journal of Japanese and International Economies , vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 96-109.

Maswood, SJ 2002, Japan in Crisis. Palgrave MacMilan, New York.

Matsuda, K 2000, ‘Lessons from Japan’s Lost Decade’, ABA Banking Journal , vol. 92, no.9, p. 128.

Sato, K 1999, The Transformation of the Japanese Economy . East Gate Book, New York.

Saxonhouse, G, Stern, RM, & Saxonhouse, GR 2004, Japan’s Lost Decade: Origins, Consequences and Prospects for Recovery . Blackwell Publishing, Malden.

Siebert, H 2004, Macroeconomic Policies in the World Economy . Springer, New York.

Teranishi, J 2005, Evolution of the Economic System in Japan . Edward Elgar Publishing, Northampton.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, March 23). Japanese Economy: The Lost Decade. https://ivypanda.com/essays/japanese-economy-the-lost-decade/

"Japanese Economy: The Lost Decade." IvyPanda , 23 Mar. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/japanese-economy-the-lost-decade/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Japanese Economy: The Lost Decade'. 23 March.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Japanese Economy: The Lost Decade." March 23, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/japanese-economy-the-lost-decade/.

1. IvyPanda . "Japanese Economy: The Lost Decade." March 23, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/japanese-economy-the-lost-decade/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Japanese Economy: The Lost Decade." March 23, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/japanese-economy-the-lost-decade/.

- Roman Borrowings from Greek Architecture

- The European Crisis Problem

- Difference between microeconomics and macroeconomics

- Macroeconomic and Microeconomics: Ubiquity and Popularity

- Science of Economics: Microeconomics and Macroeconomics

- Corporate Social Capital During Financial Crisis

- Basics of Microeconomics and Macroeconomics

- Microeconomics

- Rethinking Microeconomic Competitiveness

- Microeconomics of Customer Relationships

- Saudi and Australian Accountability and Performance Measurement

- The Role of International Finance in the Global Economy

- Economic Landscape of Turkey Since Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

- Causes and Solutions of the 2008 Financial Crisis

- Gross Domestic Product, First Quarter 2020

- Environment

- Globalization

- Japanese Language

- Social Issues

The Bubble Economy and the Lost Decade

Common Core Standards College and Career Readiness Anchor Standards for Reading

- Standard 1. Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text.

- Standard 9. Analyze how two or more texts address similar themes or topics in order to build knowledge or to compare the approaches the authors take.

- Standard 11. Respond to literature by employing knowledge of literary language, textual features, and forms to read and comprehend, reflect upon, and interpret literary texts from a variety of genres and a wide spectrum of American and world cultures.

College and Career Readiness Anchor Standards for Writing

- Standard 11. Develop personal, cultural, textual, and thematic connections within and across genres as they respond to texts through written, digital, and oral presentations, employing a variety of media and genres.

College and Career Readiness Anchor Standards for Speaking and Listening

- Standard 3. Evaluate a speaker’s point of view, reasoning, and use of evidence and rhetoric.

McRel Standard 6. Uses reading skills and strategies to understand and interpret a variety of literary texts

World History

McRel Standard 45. Understands major global trends since World War II

Japan's impressive growth during the Bubble Economy of the 1980s and subsequent challenges of the Lost Decade of the 1990s caused the Japanese to debate questions of national identity and their role in the global economy.

In small groups, have students write down and then compare the first words that come to mind when thinking about the Japanese economy. The class will focus on the changes in the economy and how those changes (and their perception) affected Japanese ideas of national identity and purpose.

Have students list three consequences--social, economic, or international--of Japan's Bubble Economy and the Lost Decade.

Receive Website Updates

Please complete the following to receive notification when new materials are added to the website.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Planet Money

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

Japan had a vibrant economy. Then it fell into a slump for 30 years.

Molly Messick

Emma Peaslee

Last month, Japan's central bank raised interest rates for the first time in 17 years. That is a really big deal, because it means that one of the spookiest stories in modern economics might finally have an ending.

Back in the 1980s, Japan performed something of an economic miracle. It transformed itself into the number two economy in the world. From Walkmans to Toyotas, the U.S. was awash in Japanese imports. And Japanese companies went on a spending spree. Sony bought up Columbia Pictures. Mitsubishi became the new majority owners of Rockefeller Center.

But in the early 1990s, it all came to a sudden halt. Japan went from being one of the fastest growing countries in the world to one of the slowest. And this economic stagnation went on and on and on. For decades.