Patient Case #1: 19-Year-Old Male With ADHD

- Craig Chepke, MD, DFAPA, FAPA

- Andrew J. Cutler, MD

Stephen Faraone, PhD, presents the case of a 19-year-old male with ADHD.

EP: 1 . Prevalence of Adult ADHD

Ep: 2 . diagnosis and management of adults adhd compared to children.

EP: 3 . Diagnosing Adults With ADHD Based on Patient Presentation

EP: 4 . Unmet Needs in the Treatment of Adult ADHD

EP: 5 . Efficacy and Safety of Treatment Options Utilized in Adult ADHD

Ep: 6 . future of adult adhd, ep: 7 . patient case #1: 19-year-old male with adhd.

EP: 8 . Patient Case #1: Prompting an ADHD Consultation

Ep: 9 . patient case #1: differentiating between adhd and other psychiatric comorbidities, ep: 10 . patient case #1: co-managing adhd, ep: 11 . patient case #1: dealing with treatment delay in adult adhd, ep: 12 . patient case #2: a 23-year-old patient with adhd, ep: 13 . patient case #2: impressions and challenges in adult adhd, ep: 14 . patient case #2: dealing with comorbidities in adult adhd, ep: 15 . patient case #2: addressing non-adherence and stigma of adult adhd, ep: 16 . patient case #2: importance of an integrative approach in adult adhd, ep: 17 . case 3: 24-year-old patient with adhd, ep: 18 . case 3: treatment goals in adult adhd, ep: 19 . case 3: factors driving treatment selection in adult adhd, ep: 20 . implications of pharmacogenetic testing in adhd, ep: 21 . novel drug delivery systems in adhd and take-home messages.

Stephen Faraone, PhD: That's a good one, yes, I'd like that, it's a very creative one, thank you, thank you. OK, let's move on to the case presentation. This first patient is a 19-year-old male, who presented to his psychiatrist after being referred by his primary care provider, PCP for ADHD consultation, during the interview, he noted he was a sophomore in college and is taking 17 credits. This semester chief complaint includes a lack of ability to focus in class as well as struggling with time management. He complained that every time he's in class, he finds himself thinking about many other responsibilities he must complete at home and feels that he cannot control it. He has had this complaint for the past 6 years, but refused to seek help, because he feared being put on medication. In high school, he was assigned a counselor who taught him behavior techniques such as making a schedule, and going on walks, which he found to be very effective. However, these techniques were less effective once he started college. His symptoms tend to get worse before exams, he often feels very anxious, leading to horrible performance on exams, he claimed that he has been this anxious since he took his LSAT tests. Currently, he is on academic probation, and is not allowed to be part of the Student Work Program, which was his only source of income. The patient has no history of substance abuse, no history of taking any medications for his symptoms, and no history of suicidal thoughts.

Transcript edited for clarity

WHO Addresses Gaps in Mental Health Care Delivery and Quality

Treating ADHD in Children: Concerns, Controversies, Safety Measures

Childhood Physical Health and ADHD Symptoms

ADHD in Older Adults

Longitudinal Study Looks at Risk of Cardiovascular Disease With Long-Term ADHD Medication Use

The Week in Review: May 20-24

2 Commerce Drive Cranbury, NJ 08512

609-716-7777

- Presidential Message

- Nominations/Elections

- Past Presidents

- Member Spotlight

- Fellow List

- Fellowship Nominations

- Current Awardees

- Award Nominations

- SCP Mentoring Program

- SCP Book Club

- Pub Fee & Certificate Purchases

- LEAD Program

- Introduction

- Find a Treatment

- Submit Proposal

- Dissemination and Implementation

- Diversity Resources

- Graduate School Applicants

- Student Resources

- Early Career Resources

- Principles for Training in Evidence-Based Psychology

- Advances in Psychotherapy

- Announcements

- Submit Blog

- Student Blog

- The Clinical Psychologist

- CP:SP Journal

- APA Convention

- SCP Conference

CASE STUDY Jen (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder)

Case study details.

Jen is a 29 year-old woman who presents to your clinic in distress. In the interview she fidgets and has a hard time sitting still. She opens up by telling you she is about to be fired from her job. In addition, she tearfully tells you that she is in a major fight with her husband of 1 year because he is ready to have children but she fears that she is “too disorganized to be a good mother.” As you break down some of the processes that have led to her current crises, you learn that she has a hard time with time management and tends to be disorganized. She chronically misplaces everyday objects like her keys and runs late to appointments. Although she wants her work to be perfect, she is prone to making careless mistakes. The struggle for perfection makes starting a new task feel very stressful, leading her to procrastinate starting in the first place. As a consequence, she has recently received a number of warnings from her boss related to missing deadlines for assignments and errors in her work, which has led to her acute fear of being fired. As her performance at work has plummeted and she has grown increasingly anxious and doubting of herself, she has grown more pessimistic about starting a family. You learn that she received extra time for test taking in school as a child but never had any formal neuropsychological testing. With Jen’s permission, you conduct additional structured assessments, including collecting collateral information from her fiancé, and conclude that she has adult ADHD.

- Concentration Difficulties

- Impulsivity

Diagnoses and Related Treatments

1. attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (adults).

Thank you for supporting the Society of Clinical Psychology. To enhance our membership benefits, we are requesting that members fill out their profile in full. This will help the Division to gather appropriate data to provide you with the best benefits. You will be able to access all other areas of the website, once your profile is submitted. Thank you and please feel free to email the Central Office at [email protected] if you have any questions

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): A Case Study and Exploration of Causes and Interventions

- First Online: 02 March 2019

Cite this chapter

- Bijal Chheda-Varma 5

3360 Accesses

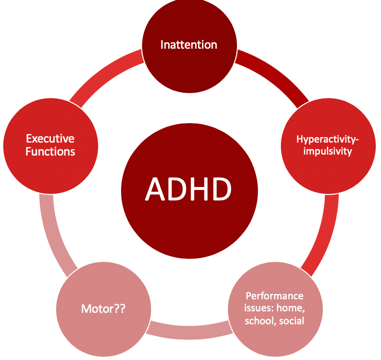

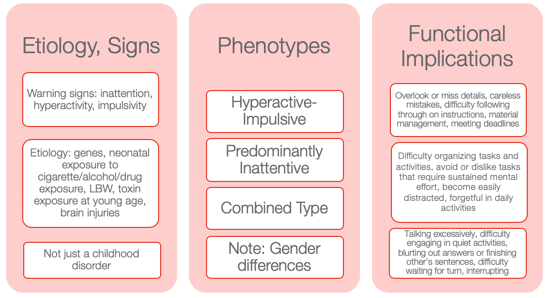

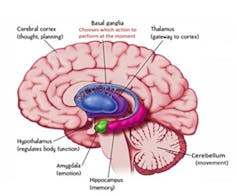

The male to female ratio of ADHD is 4:1. This chapter on ADHD provides a wide perspective on understanding, diagnosis and treatment for ADHD. It relies on a neurodevelopmental perspective of ADHD. Signs and symptoms of ADHD are described through the DSM-V criteria. A case example (K, a patient of mine) is illustrated throughout the chapter to provide context and illustrations, and demonstrates the relative merits of “doing” (i.e. behavioural interventions) compared to cognitive insight, or medication alone. Finally, a discussion of the Cognitive Behavioral Modification Model (CBM) for the treatment of ADHD provides a snapshot of interventions used by clinicians providing psychological help.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

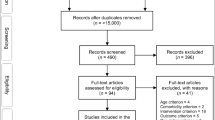

Psychological Treatments in Adult ADHD: A Systematic Review

Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

ADHD and Its Therapeutics

Alderson, R. M., Hudec, K. L., Patros, C. H. G., & Kasper, L. J. (2013). Working memory deficits in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): An examination of central executive and storage/rehearsal processes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122 (2), 532–541. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0031742 .

Arcia, E., & Conners, C. K. (1998). Gender differences in ADHD? Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 19 (2), 77–83. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004703-199804000-00002 .

Barkley, R. A. (1990). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment . New York: Guildford.

Google Scholar

Barkley, R. A. (1997). ADHD and the nature of self-control . New York: Guilford Press.

Barkley, R. A. (2000). Commentary on the multimodal treatment study of children with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 28 (6), 595–599. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005139300209 .

Article Google Scholar

Barkley, R., Knouse, L., & Murphy, K. Correction to Barkley et al. (2011). Psychological Assessment [serial online]. June 2011; 23 (2), 446. Available from: PsycINFO, Ipswich, MA. Accessed December 11, 2014.

Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders . New York, NY: International Universities Press.

Brown, T. E. (2005). Attention deficit disorder: The unfocused mind in children and adults . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Brown, T. (2013). A new understanding of ADHD in children and adults . New York: Routledge.

Chacko, A., Kofler, M., & Jarrett, M. (2014). Improving outcomes for youth with ADHD: A conceptual framework for combined neurocognitive and skill-based treatment approaches. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-014-0171-5 .

Chronis, A., Jones, H. A., Raggi, V. L. (2006, August). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 26 (4), 486–502. ISSN 0272-7358. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.01.002 .

Curatolo, P., D’Agati, E., & Moavero, R. (2010). The neurobiological basis of ADHD. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 36 , 79. http://doi.org/10.1186/1824-7288-36-79 . http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0272735806000031 .

Curtis, D. (2010). ADHD symptom severity following participation in a pilot, 10-week, manualized, family-based behavioral intervention. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 32 , 231–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317107.2010.500526 .

De Young, R. (2014). Using the Stroop effect to test our capacity to direct attention: A tool for navigating urgent transitions. http://www.snre.umich.edu/eplab/demos/st0/stroopdesc.html .

Depue, B. E., Orr, J. M., Smolker, H. R., Naaz, F., & Banich, M. T. (2015). The organization of right prefrontal networks reveals common mechanisms of inhibitory regulation across cognitive, emotional, and motor processes. Cerebral Cortex (New York, NY: 1991), 26 (4), 1634–1646.

D’Onofrio, B. M., Van Hulle, C. A., Waldman, I. D., Rodgers, J. L., Rathouz, P. J., & Lahey, B. B. (2007). Causal inferences regarding prenatal alcohol exposure and childhood externalizing problems. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64, 1296–1304 [PubMed].

DSM-V. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders . American Psychological Association.

Eisenberg, D., & Campbell, B. (2009). Social context matters. The evolution of ADHD . http://evolution.binghamton.edu/evos/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/eisenberg-and-campbell-2011-the-evolution-of-ADHD-artice-in-SF-Medicine.pdf .

Gizer, I. R., Ficks, C., & Waldman, I. D. (2009). Hum Genet, 126 , 51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-009-0694-x .

Hinshaw, S. P., & Scheffler, R. M. (2014). The ADHD explosion: Myths, medication, money, and today’s push for performance . New York: Oxford University Press.

Kapalka, G. M. (2008). Efficacy of behavioral contracting with students with ADHD . Boston: American Psychological Association.

Kapalka, G. (2010). Counselling boys and men with ADHD . New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Book Google Scholar

Knouse, L. E., et al. (2008, October). Recent developments in psychosocial treatments for adult ADHD. National Institute of Health, 8 (10), 1537–1548. https://doi.org/10.1586/14737175.8.10.1537 .

Laufer, M., Denhoff, E., & Solomons, G. (1957). Hyperkinetic impulse disorder in children’s behaviour problem. Psychosomatic Medicine, 19, 38–49.

Raggi, V. L., & Chronis, A. M. (2006). Interventions to address the academic impairment of children and adolescents with ADHD. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 9 (2), 85–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-006-0006-0 .

Ramsay, J. R. (2011). Cognitive behavioural therapy for adult ADHD. Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management, 18 (11), 526–536.

Retz, W., & Retz-Junginger, P. (2014). Prediction of methylphenidate treatment outcome in adults with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience . https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-014-0542-4 .

Safren, S. A., Otto, M. W., Sprich, S., Winett, C. L., Wilens, T. E., & Biederman, J. (2005, July). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for ADHD in medication-treated adults with continued symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43 (7), 831–842. ISSN 0005-7967. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2004.07.001 . http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0005796704001366 .

Sibley, M. H., Kuriyan, A. B., Evans, S. W., Waxmonsky, J. G., & Smith, B. H. (2014). Pharmacological and psychosocial treatments for adolescents with ADHD: An updated systematic review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 34 (3), 218–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.02.001 .

Simchon, Y., Weizman, A., & Rehavi, M. (2010). The effect of chronic methylphenidate administration on presynaptic dopaminergic parameters in a rat model for ADHD. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 20 (10), 714–720. ISSN 0924-977X. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2010.04.007 . http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0924977X10000891 .

Swanson, J. M., & Castellanos, F. X. (2002). Biological bases of ADHD: Neuroanatomy, genetics, and pathophysiology. In P. S. Jensen & J. R. Cooper (Eds.), Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: State if the science, best practices (pp. 7-1–7-20). Kingston, NJ: Civic Research Institute.

Toplak, M. E., Connors, L., Shuster, J., Knezevic, B., & Parks, S. (2008, June). Review of cognitive, cognitive-behavioral, and neural-based interventions for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Clinical Psychology Review, 28 (5), 801–823. ISSN 0272-7358. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2007.10.008 . http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0272735807001870 .

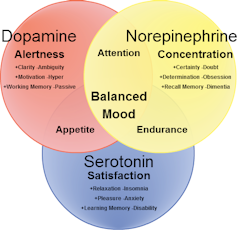

Wu, J., Xiao, H., Sun, H., Zou, L., & Zhu, L.-Q. (2012). Role of dopamine receptors in ADHD: A systematic meta-analysis. Molecular Neurobiology, 45 , 605–620. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-012-8278-5 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Foundation for Clinical Interventions, London, UK

Bijal Chheda-Varma

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

UCL, London, UK

John A. Barry

Norfolk and Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust, Wymondham, UK

Roger Kingerlee

Change, Grow, Live, Dagenham/Southend, Essex, UK

Martin Seager

Community Interest Company, Men’s Minds Matter, London, UK

Luke Sullivan

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Chheda-Varma, B. (2019). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): A Case Study and Exploration of Causes and Interventions. In: Barry, J.A., Kingerlee, R., Seager, M., Sullivan, L. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Male Psychology and Mental Health. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04384-1_15

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04384-1_15

Published : 02 March 2019

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-04383-4

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-04384-1

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

A Case Study in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: An Innovative Neurofeedback-Based Approach

- University of Oviedo

Abstract and Figures

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Int J Environ Res Publ Health

- Malgorzata Nermend

- Kesra Nermend

- Giada Viviani

- Nerea Aldunate

- Luis J Fuentes

- APPL PSYCHOPHYS BIOF

- Howard Lightstone

- Curr Psychiatr Rep

- J PSYCHIATR RES

- Siyuan Wang

- CLIN NEUROPHYSIOL

- Adam R Clarke

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults: A case study

Affiliations.

- 1 University of North Dakota, United States of America. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 University of North Dakota, United States of America.

- 3 Dana Wiley, MD PA.

- PMID: 35461644

- DOI: 10.1016/j.apnu.2021.12.003

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is often misdiagnosed or mistreated in adults because it is often thought of as a childhood problem. If a child is diagnosed and treated for the disorder, it often persists into adulthood. In adult ADHD, the symptoms may be comorbid or mimic other conditions making diagnosis and treatment difficult. Adults with ADHD require an in-depth assessment for proper diagnosis and treatment. The presentation and treatment of adults with ADHD can be complex and often requires interdisciplinary care. Mental health and non-mental health providers often overlook the disorder or feel uncomfortable treating adults with ADHD. The purpose of this manuscript is to discuss the diagnosis and management of adults with ADHD.

Keywords: Adult; Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder; Misuse; Psychoeducation; Stimulant.

Copyright © 2022 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- [Awareness of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in Greece]. Pehlivanidis A. Pehlivanidis A. Psychiatriki. 2012 Jun;23 Suppl 1:60-5. Psychiatriki. 2012. PMID: 22796974 Review. Greek, Modern.

- Practical considerations for the evaluation and management of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in adults. Weibel S, Menard O, Ionita A, Boumendjel M, Cabelguen C, Kraemer C, Micoulaud-Franchi JA, Bioulac S, Perroud N, Sauvaget A, Carton L, Gachet M, Lopez R. Weibel S, et al. Encephale. 2020 Feb;46(1):30-40. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2019.06.005. Epub 2019 Oct 11. Encephale. 2020. PMID: 31610922 Review.

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults: conceptual and clinical issues. Trollor JN. Trollor JN. Med J Aust. 1999 Oct 18;171(8):421-5. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1999.tb123723.x. Med J Aust. 1999. PMID: 10590746 Review.

- Health-related quality of life in children and adolescents who have a diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Klassen AF, Miller A, Fine S. Klassen AF, et al. Pediatrics. 2004 Nov;114(5):e541-7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0844. Pediatrics. 2004. PMID: 15520087

- Clinical assessment and treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults. Asherson P. Asherson P. Expert Rev Neurother. 2005 Jul;5(4):525-39. doi: 10.1586/14737175.5.4.525. Expert Rev Neurother. 2005. PMID: 16026236 Review.

- Acoustic and Text Features Analysis for Adult ADHD Screening: A Data-Driven Approach Utilizing DIVA Interview. Li S, Nair R, Naqvi SM. Li S, et al. IEEE J Transl Eng Health Med. 2024 Feb 26;12:359-370. doi: 10.1109/JTEHM.2024.3369764. eCollection 2024. IEEE J Transl Eng Health Med. 2024. PMID: 38606391 Free PMC article.

- Search in MeSH

Related information

Linkout - more resources, full text sources.

- Elsevier Science

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

- Genetic Alliance

- MedlinePlus Health Information

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

An ADHD diagnosis in adulthood comes with challenges and benefits

For adults, undiagnosed ADHD symptoms can lead to chronic stress and low self-esteem

Vol. 54 No. 2 Print version: page 52

- Perception and Attention

When Terry Matlen, a clinical social worker, was in her 40s, she was diagnosed with ADHD. “My entire life, there was something off,” Matlen said. This included significant anxiety as well as academic and behavioral issues, all of which started at a young age. Although Matlen was initially quite skeptical of her diagnosis, going so far as to seek out a second and third opinion, she eventually came to accept that she had ADHD.

“This makes sense now. I can’t concentrate; I can’t finish projects; my house is a disaster; I can’t get dinner on the table,” Matlen said. “Anxiety doesn’t explain the extent of my disorganization.”

Matlen was diagnosed in the mid-1990s, when many specialists still didn’t understand what ADHD looked like in either girls or adults. Matlen didn’t look like the stereotypical little boy who couldn’t sit still. Although she struggled a lot with her symptoms, which included being unable to pay attention in class or stay organized, no one recognized that the underlying issue was undiagnosed ADHD.

ADHD has three subtypes, which include hyperactive impulsive, primarily inattentive, and combined. With inattentive type, the restlessness is internal. “A lot of kids with inattentive ADHD get overlooked,” said Peter Jaksa, PhD, a psychologist who specializes in treating ADHD. “The behavioral problems get more attention.” For many with inattentive ADHD, they are the ones daydreaming in class rather than paying attention. However, since they aren’t being disruptive, their symptoms can easily go unnoticed.

This is especially true with women and girls, as ADHD is more often diagnosed and treated in males than females, due to differences in how symptoms look ( Skogli, E. W., et al., BMC Psychiatry , Vol. 13, 2013 ). As a number of studies show, untreated ADHD leads to adverse effects on long-term academic performance ( Arnold, L. E., et al., Journal of Attention Disorders , Vol. 24, No. 1, 2015 ). In addition, a number of studies show that those with untreated ADHD fare worse than those with treated ADHD or no ADHD ( Harpin, V., et al., Journal of Attention Disorders , Vol. 20, No. 4, 2013 ).

The process of diagnosing adults

For symptoms to be considered ADHD, they must have started before the age of 12. This makes diagnosing adults more complicated, as the process requires creating a timeline of when symptoms first appeared. In addition to talking with his patient, Jaksa finds that it can be helpful to look at old report cards, where comments such as “Struggles to pay attention during class,” “Often forgets homework at home,” or “Isn’t living up to potential” can help give him a sense of when symptoms started appearing.

“We have a much longer history to look at,” he said. “The best diagnostic indicator for ADHD is not test scores; it’s history.” For the diagnostic process, Jaksa conducts a very structured interview—one that delves into their social, emotional, and academic history. If possible, he interviews a family member who can provide perspective on childhood behaviors.

Jaksa said adults often have comorbidities, such as anxiety and depression. With these comorbidities, untreated ADHD can either cause them or make them worse. “When ADHD is not diagnosed—when it’s not treated effectively—over time, chronic stress and frustration lead to anxiety,” Jaksa said. “This has a very negative impact on self-esteem. It’s very common to see adults with ADHD grow up with a strong sense of underachievement.” Continually hearing messages like “try harder” or “you should be doing better,” can get internalized and lead to anxiety and/or depression, Jaksa said.

In some patients, providers may recognize signs right away, such as tardiness, forgetting valuable personal items, or fidgeting while in the waiting room. Although no one symptom can be definitive, all of this added up can paint a picture of what the symptoms look like, how long they have been going on, and the degree of functional impairment. “My mind is shifting constantly,” said Lisa Green, an oncology nurse who was diagnosed with ADHD in her 40s.

It also helps the diagnosis if there is a family history of ADHD, as it is a highly heritable disorder. For Matlen, the process of seeking a diagnosis for her younger daughter was when she realized that she also had the disorder. “It’s pretty well established that ADHD is about 70% to 80% heritable,” said Eugene Arnold, a professor emeritus at The Ohio State University whose research focuses on ADHD.

Difficulties with diagnosing

One of the challenging aspects of diagnosing an adult is the presence of other comorbidities, some of which can mimic ADHD symptoms. These comorbidities can either be due to a separate disorder or be caused by the ADHD. For many people with ADHD, Matlen included, the lack of early treatment, combined with symptoms of ADHD, can lead to developing mood disorders such as anxiety and depression. If their underlying ADHD is not diagnosed and treated, treatment for their other comorbidities is often ineffective. ( Ginsberg, Y., et al., Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders , Vol. 16, No. 3, 2014 ). “My anxiety is triggered a lot by being disorganized, by not being prepared, by being constantly overwhelmed,” Matlen said.

There’s also an overlap between ADHD and autism spectrum disorder (ASD). “About half of people with autism also have ADHD,” Arnold said. With ADHD being more common than ASD, the reverse is not true—with a lower proportion of people with ADHD also having ASD.

Jon Stevens, MD, a psychiatrist based in Houston, compares the onset of symptoms as being like layers of an onion: The deepest layer is developmental disorders, such as autism; the second deepest layer is ADHD, for which the symptoms can be observed quite early, followed by mood disorders such as anxiety and depression, which can develop as early as middle or high school. Finally, the outermost layer is schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, which tend to emerge during college years or a little later.

“These conditions, in my experience, develop inside out,” Stevens said. Symptoms of developmental disorders such as autism show up the earliest, while ADHD symptoms will show up a little later. Some of the more noticeable symptoms, such as hyperactivity, parents will start noticing early on, while other symptoms, such as inattentiveness, will start becoming more noticeable once children start school.

Another major difference is the persistence of symptoms. “If you think about anxiety and depression, those disorders and the symptoms that flow from them, tend to be more situational and more cyclic,” said Will Canu, PhD, a professor of psychology at Appalachian State University. With a disorder like ADHD, the symptoms are always there, with the caveat that they can be exacerbated under certain conditions, such as during times of stress or from anxiety or depression.

The effect of Covid -19 on adults with ADHD

The Covid -19 pandemic was particularly hard on those with ADHD because of the disruption in routine. Routines are important for people with ADHD, as they can help with executive functioning issues, such as staying organized and staying on track. However, developing and maintaining these routines is harder, which means that major changes in working and home life have been particularly hard to navigate.

[ Related: Helping adults and children with ADHD in a pandemic world ]

In Stevens’ clinical practice, he has seen patients cope with stress from the pandemic in a number of ways. For adults who were actively receiving treatment, the shift to working from home offered some benefits. “Provided they kept taking their medication, they generally fared well,” he said. “A lot of my patients found [working from home] more helpful, because there were fewer distractions of the water cooler chatter or someone coming to your cubicle.” The big exception was if patients started self-medicating with alcohol or other substances.

Constant upheaval, combined with childcare disruptions, created extremely difficult conditions for women with undiagnosed ADHD and young children, Canu said. In addition to major disruptions in routines, the unpredictability of school and daycare closures has been particularly challenging for parents with young children.

The advantage of diagnosis and treatment

For many patients whose symptoms were overlooked during their early years, diagnosis can be both life changing, and bittersweet. In a 2020 study, researchers compared 444 adults with diagnosed ADHD with 1,055 adults who exhibited symptoms but had no formal diagnosis. After matching for age and gender, those with a diagnosis reported a higher quality of life, which included metrics for work productivity, self-esteem, and functional performance ( Pawaskar, M., et al., Journal of Attention Disorders , Vol. 24, No. 1, 2020 ).

Canu said being diagnosed helps people understand themselves better, which includes gaining perspective on the reasons for some of their struggles. “That can change the way they feel about themselves, which can cascade into a lot of positive things,” Canu said.

Treatments include behavioral strategies for managing their symptoms, for which working with an expert, such as a psychologist who is experienced in treating patients with ADHD, can be invaluable. This includes cognitive behavioral therapy for ADHD, which focuses on managing executive functioning difficulties such as time management, organizational skills, impulse control, and emotional self-regulation.

When necessary, medication can also help manage symptoms. For psychologists who do not have prescribing privileges, this can mean working in concert with integrated care teams, primary-care providers, or psychiatrists. For many patients, their most effective treatment regimen is a combination of behavioral strategies and medication. “With that in place, if it’s effective, they’re able to function better,” Canu said.

In a 2014 study, 250 previously nonmedicated adults who received the ADHD medication methylphenidate for the first time were followed for a full year, with those patients who either couldn’t tolerate or didn’t experience relief in symptoms switched to either an alternate stimulant medication or the nonstimulant medication atomoxetine. Compared with their peers who discontinued medication, those who were still on medication had reduced severity of symptoms ( Fredriksen, M., et al., European Neuropsychopharmacology , Vol. 24, No. 12, 2014 ). “Medication slows me down enough to breathe and to think,” Green said.

Dealing with late-life diagnosis

Receiving a diagnosis as an adult can often bring up some complicated emotions, whether it’s grief over lost opportunities, relief at finally understanding certain struggles, or anger over symptoms having been overlooked for so long. For Matlen, she felt an overwhelming sense of relief. “There was a concrete explanation,” she said.

For others, receiving a diagnosis later in life can lead to regrets about lost opportunities, whether it was failing out of school, struggling to establish a career, or experiencing relationship issues because of their ADHD symptoms going overlooked and untreated. “There is a lot of grief work that needs to be done to help work through the many years of struggling and not knowing why,” Matlen said. However, in her experience, “Once all those parts and pieces are looked at with this new understanding, people really take off, in a good way,” she said. Often, therapy is an important component of thriving after a diagnosis.

For Matlen, in addition to gaining a better understanding of why she was struggling so much, receiving a diagnosis and treatment changed her entire life. It ended up being the missing piece that helped ease her anxiety. Once she had a diagnosis and started treatment, her issues with anxiety started improving in a way that years of therapy and antianxiety medication had never been able to accomplish.

Given how life-changing her diagnosis was, combined with the lack of information and resources available, especially for women, Matlen ultimately made a career switch, combining her own experience of growing up with undiagnosed ADHD with her background as a clinical social worker. She went on to write the books The Queen of Distraction and Survival Tips for Women With AD/HD . She also founded a Facebook group for women with ADHD, which now has over 36,000 members, and she often consults with specialists on the realities of living with ADHD.

Now, almost 30 years after her initial diagnosis, Matlen still hasn’t seen nearly as much progress in the field as she had hoped, especially for girls and women. “I see the same stories even now,” she said.

Further reading

Meta-analysis of cognitive–behavioral treatments for adult ADHD Knouse, L. E., et al., Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 2017

Association between psychiatric symptoms and executive function in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder Arellano-Virto, P. T., et al., Psychology & Neuroscience , 2021

The ADHD Symptom Infrequency Scale (ASIS): A novel measure designed to detect adult ADHD simulators Courrégé, S. C., et al., Psychological Assessment , 2019

A randomized controlled trial examining CBT for college students with ADHD Anastopoulos, A. D., et al., Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 2021

Succeeding With Adult ADHD: Daily Strategies to Help You Achieve Your Goals and Manage Your Life Levrini, A., APA LifeTools Series, 2023

Recommended Reading

Related topic

Six things psychologists are talking about.

The APA Monitor on Psychology ® sister e-newsletter offers fresh articles on psychology trends, new research, and more.

Welcome! Thank you for subscribing.

Speaking of Psychology

Subscribe to APA’s audio podcast series highlighting some of the most important and relevant psychological research being conducted today.

Subscribe to Speaking of Psychology and download via:

Contact APA

You may also like.

Faculty and Disclosures

Disclosure of conflicts of interest, disclosure of unlabeled use.

Attention-deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Two Case Studies

- Authors: Authors: Joseph Biederman, MD; Stephen V. Faraone, PhD

- THIS ACTIVITY HAS EXPIRED FOR CREDIT

Target Audience and Goal Statement

This activity has been designed to meet the educational needs of pediatricians, family practitioners, child and adolescent psychiatrists, and general psychiatrists involved in the management of patients with ADHD.

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a chronic condition that affects 8% to 12% of school-aged children and contributes significantly to academic and social impairment. There is currently broad agreement on evidence-based best practices of ADHD identification and diagnosis, therapeutic approach, and monitoring. However, the increasing rate of diagnosis and treatment in the pediatric population has contributed to the significant public debate and misunderstanding of ADHD. Despite increased awareness, Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a chronic condition that affects 8% to 12% of school-aged children and contributes significantly to academic and social impairment. There is currently broad agreement on evidence-based best practices of ADHD identification and diagnosis, therapeutic approach, and monitoring. However, the increasing rate of diagnosis and treatment in the pediatric population has contributed to the significant public debate and misunderstanding of ADHD. Despite increased awareness, ADHD remains underrecognized and may be undertreated by a factor of 10 to 1 in the US population. In order to educate the public and ensure optimal outcomes for ADHD patients, this continuing education activity has been developed to provide physicians and other healthcare providers with the most current information available on assessing and treating ADHD.

Upon completion of this activity, participants should be able to:

- Discuss the incidence of ADHD in adolescents and adults.

- Identify DSM-IV criteria used to make the diagnosis of ADHD in each age group.

- List important comorbidities of ADHD and identify distinguishing features between ADHD and other psychiatric diagnoses with similar manifestations.

- Describe a pharmacologic approach to ADHD treatment, including treatment goals and choice of medication.

- Enumerate self-management skills to be recommended when coaching ADHD patients on how to get along at school, at work, and at home.

Disclosures

Accreditation statements, for physicians.

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and Policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME). The Postgraduate Institute for Medicine is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

The Postgraduate Institute for Medicine designates this educational activity for a maximum of 1.0 Category 1 credit toward the AMA Physician's Recognition Award. Each physician should claim only those credits that he/she actually spent in the activity.

Contact This Provider

For questions regarding the content of this activity, contact the accredited provider for this CME/CE activity noted above. For technical assistance, contact [email protected]

Instructions for Participation and Credit

There are no fees for participating in or receiving credit for this online educational activity. For information on applicability and acceptance of continuing education credit for this activity, please consult your professional licensing board. This activity is designed to be completed within the time designated on the title page; physicians should claim only those credits that reflect the time actually spent in the activity. To successfully earn credit, participants must complete the activity online during the valid credit period that is noted on the title page. Follow these steps to earn CME/CE credit*:

- Read the target audience, learning objectives, and author disclosures.

- Study the educational content online or printed out.

- Online, choose the best answer to each test question. To receive a certificate, you must receive a passing score as designated at the top of the test. In addition, you must complete the Activity Evaluation to provide feedback for future programming.

You may now view or print the certificate from your CME/CE Tracker. You may print the certificate but you cannot alter it. Credits will be tallied in your CME/CE Tracker and archived for 5 years; at any point within this time period you can print out the tally as well as the certificates by accessing "Edit Your Profile" at the top of your Medscape homepage. *The credit that you receive is based on your user profile.

- Policy Statement for Documentation of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Adolescents and Adults (Revised). Princeton, NJ: Office of Disability Policy, Educational Testing Service; June 1999.

- American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed (DSM-IV). Washington, DC: APA, 2000.

- Dulcan MK, Benson RS. AACAP Official Action. Summary of the practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children, adolescents, and adults with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:1311-7.

- Elia J, Ambrosini PJ, Rapoport JL. Treatment of attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:780-8.

- Wender PH. Pharmacotherapy of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59 Suppl 7:76-9.

- Wilens TE, Biederman J, Lerner M; et al. Effects of once-daily osmotic-release methylphenidate on blood pressure and heart rate in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: results from a one-year follow-up study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24:36-41.

- Searight HR, Burke JM, Rottnek F. Adult ADHD: evaluation and treatment in family medicine. Am Fam Physician. 2000;62:2077-86, 2091-2.

- Biederman J, Faraone SV, Monuteaux MC, et al. Growth deficits and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder revisited: Impact of gender, development, and treatment. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1010-6.

- Spencer T, Biederman J, Wilens T. Growth deficits in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 1998;102:501-6.

- Spencer T, Biederman J, Harding M, et al. Growth deficits in ADHD children revisited: evidence for disorder-associated growth delays? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:1460-9.

- Hechtman L, Greenfield B. Long-term use of stimulants in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: safety, efficacy, and long-term outcome. Paediatr Drugs. 2003;5:787-94.

- Spencer T, Biederman, M, Coffey B, et al. The 4-year course of tic disorders in boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:842-7.

- Biederman J, Faraone SV, Spencer T. Pharmacotherapy of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder reduces risk for substance use disorder. Pediatrics. 1999;104:e20.

- Biederman J, Willens TE, Mick E, et al. Does attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder impact the developmental course of drug and alcohol abuse and dependence? Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:269-73.

- Greene RW, Biederman J, Faraone SV, et al. Adolescent outcome of boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and social disability: results from a 4-year longitudinal follow-up study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:758-67.

- Wilens TE, Biederman J, Mick E, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is associated with early onset substance use disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997 Aug;185:475-82.

- Clure C, Brady KT, Saladin ME, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and substance use: symptom pattern and drug choice. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1999;25:441-8.

- Faraone SV, Biederman J, Mick E. The age-dependent decline of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Psychological Medicine. In press.

- Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Am J Psychiatry. In press.

- Biederman J, Faraone SV, Mick E, et al. Clinical correlates of ADHD in females: findings from a large group of girls ascertained from pediatric and psychiatric referral sources. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:966-75.

- Weiss G, Hechtman L. Adult hyperactive subjects' view of their treatment in childhood and adolescence. In: G. Weiss and L. Hechtman, eds. Hyperactive Children Grown Up: ADHD in Children, Adolescents, and Adulthood, 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 1993.

- Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bessler A, et al. Adult outcome of hyperactive boys: educational achievement, occupational rank, and psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:565-76.

- Biederman J. Impact of Comorbidity in Adults with ADHD. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004(Suppl 3);65:3-7.

- Murphy K, Barkley RA. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder adults: comorbidities and adaptive impairments. Compr Psychiatry. 1996;37:393-401.

- Biederman J, Faraone SV, Spencer T, et al. Patterns of psychiatric comorbidity, cognition, and psychosocial functioning in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:1792-8.

- Shekim WO, Asarnow RF, Hess E, et al. A clinical and demographic profile of a sample of adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, residual state. Compr Psychiatry. 1990;31:416-25.

- Hornig M. Addressing comorbidity in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:769-75.

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;40:57-87.

- Pliszka SR, Carlson CL, Swanson JM. ADHD With Comorbid Disorders: Clinical Assessment and Management. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 1999.

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- PubMed/Medline

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

A case study in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: an innovative neurofeedback-based approach.

1. Introduction

1.1. evaluation of adhd, 1.2. adhd intervention, 2. methodology, 2.1. description of the case, 2.1.1. patient identification, 2.1.2. reason for consultation, 2.1.3. history of the problem, 2.2. proposed evaluation and intervention, 2.2.1. evaluation: brainwave analysis with the miniq instrument, 2.2.2. intervention: neurofeedback protocols, 3.1. brainwave evaluation, 3.2. progression following neurofeedback intervention, 4. discussion, 5. conclusions, author contributions, institutional review board statement, informed consent statement, data availability statement, conflicts of interest.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders , 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mirsky, A.F. Disorders of attention: A neuropsychological perspective. In Attention, Memory and Executive Function ; Lyon, R.G., Kranesgor, N.A., Eds.; Paul, H. Brookes: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1996; pp. 71–95. [ Google Scholar ]

- Barkley, R.A. Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: Constructing a unifying theory of ADHD. Psychol. Bull. 1997 , 121 , 65–94. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems , 11th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [ Google Scholar ]

- Klem, G.H.; Lüders, H.O.; Jasper, H.H.; Elger, C. The ten-twenty electrode system of the International Federation. The International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1999 , 52 , 3–6. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lubar, J.F. Neurofeedback for the management of attention deficit disorders. In Biofeedback: A Practitioner’s Guide , 3rd ed.; Schwartz, M.S., Andrasik, F., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, USA, 2003; pp. 409–443. [ Google Scholar ]

- Monastra, V.J.; Lubar, J.F.; Linden, M.; VanDeusen, P.; Green, G.; Wing, W.; Phillips, A.; Fenger, T.N. Assessing attention deficit hyperactivity disorder via quantitative electroencephalography: An initial validation study. Neuropsychology. 1999 , 13 , 424–433. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Martella, D.; Aldunate, N.; Fuentes, L.J.; Sánchez-Pérez, N. Arousal and executive alterations in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Front. Psychol. 2020 , 11 , 1991. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Rodríguez, C.; González-Castro, P.; Cueli, M.; Areces, D.; González-Pienda, J.A. Attention deficity/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) diagnosis: An activation-execution model. Front. Psychol. 2016 , 7 , 1406. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Clarke, A.; Barry, R.; McCarthy, R.; Selikowitz, M. Age and sex effects in the EEG: Development of the normal child. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2001 , 112 , 806–814. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Clarke, A.R.; Barry, R.J.; Johnstone, S.J.; McCarthy, R.; Selikowitz, M. EEG development in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: From child to adult. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2019 , 130 , 1256–1262. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Kerson, C.; deBeus, R.; Lightstone, H.; Arnold, L.E.; Barterian, J.; Pan, X.; Monastra, V.J. EEG theta/beta ratio calculations differ between various EEG neurofeedback and assessment software packages: Clinical interpretation. Clin. EEG Neurosci. 2020 , 51 , 114–120. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Caye, A.; Swanson, J.M.; Coghill, D.; Rohde, L.A. Treatment strategies for ADHD: An evidence-based guide to select optimal treatment. Mol. Psychiatry 2019 , 24 , 390–408. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Arns, M.; Heinrich, H.; Strehl, U. Evaluation of neurofeedback in ADHD: The long and winding road. Biol. Psychol. 2014 , 95 , 108–115. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Arns, M.; Clark, C.R.; Trullinger, M.; deBeus, R.; Mack, M.; Aniftos, M. Neurofeedback and attention-defcit/hyperactivity-disorder (ADHD) in children: Rating the evidence and proposed guidelines. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 2020 , 45 , 39–48. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ] [ Green Version ]

- Cueli, M.; Rodríguez, C.; Cabaleiro, P.; García, T.; González-Castro, P. Differential efficacy of neurofeedback in children with ADHD presentations. J. Clin. Med. 2019 , 8 , 204. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ] [ Green Version ]

- Lubar, J.F.; Shouse, M.N. EEG and behavioral changes in a hyperkinetic child concurrent with training ofthe sensorimotor rhythm (SMR): A preliminary report. Biofeedback Self-Regul. 1976 , 1 , 293–306. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- González-Castro, P.; Cueli, M.; Rodríguez, C.; García, T.; Álvarez, L. Efficacy of neurofeedback versus pharmacological support in subjects with ADHD. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 2016 , 41 , 17–25. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lambez, B.; Harwood-Gross, A.; Golumbic, E.Z.; Rassovsky, Y. Non-pharmacological interventions for cognitive difficulties in ADHD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatry Res. 2020 , 120 , 40–55. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Yan, L.; Wang, S.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, J. Effects of neurofeedback versus methylphenidate for the treatment of ADHD: Systematic review ad meta-analysis of head-to-head trials. Medicine 2019 , 97 , 12623. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Van Doren, J.; Arns, M.; Heinrich, H.; Vollebregt, M.A.; Strehl, U.; Loo, L.K. Sustained effects of neurofeedback in ADHD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019 , 28 , 293–305. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Vivani, G.; Vallesi, A. EEG-neurofeedback and executive function enhancement in healthy adults: A systematic review. Psychophysiology 2021 , 58 , 13874. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Danielson, M.L.; Visser, S.N.; Chronis-Tuscano, A.; DuPaul, G.J. A national description of treatment among United States children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Pediatrics 2018 , 192 , 240–246. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Enriquez-Geppert, S.; Smit, D.; Garcia-Pimenta, M.; Arns, A. Neurofeedback as a treatment intervention in ADHD: Current evidence and practice. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019 , 21 , 46. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ] [ Green Version ]

- Duric, N.S.; Abmus, J.; Elgen, I.B. Self-reported efficacy of neurofeedback treatment in a clinical randomized controlled study of ADHD children and adolescents. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2014 , 10 , 1645–1654. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Sterman, M.B. Epilepsy and its treatment with EEG feedback therapy. Ann. Behav. Med. 1986 , 8 , 21–25. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Jarrett, M.A.; Gable, P.A.; Rondon, A.T.; Neal, L.B.; Price, H.F.; Hilton, D.C. An EEG study of children with and without ADHD symptoms: Between-group differences and associations with sluggish cognitive tempo symptoms. J. Atten. Disord. 2017 , 24 , 1002–1010. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- van Dijk, H.; deBeus, R.; Kerson, C.; Roley-Roberts, M.E.; Monastra, V.J.; Arnold, L.E.; Pan, X.; Arns, M. Different spectral analysis methods for the theta/beta ratio calculate different ratios but do not distinguish ADHD from controls. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 2020 , 45 , 165–173. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Janssen, T.W.P.; Bink, M.; Weeda, W.D.; Geladé, K.; van Mourik, R.; Maras, A.; Oosterlaan, J. Learning curves of theta/beta neurofeedback in children with ADHD. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017 , 26 , 573–582. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Doppelmayr, M.; Weber, E. Effects on SMR and theta/beta neurofeedback on reaction times, spatial abilities and creativity. J. Neurother. 2011 , 15 , 115–129. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Vernon, D.; Egner, T.; Cooper, N.; Compton, T.; Neilands, C.; Sheri, A.; Gruzelier, J. The effect of training distinct neurofeedback protocols on aspects of cognitive performance. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2003 , 47 , 75–85. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Gevensleben, H.; Holl, B.; Albrecht, B.; Schlamp, D.; Kratz, O.; Studer, P.; Wangler, S.; Rothenberger, A.; Moll, G.H.; Heinrich, H. Distinct EEG effects related to neurofeedback training in children with ADHD: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2009 , 74 , 149–157. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Leins, U.; Goth, G.; Hinterberger, T.; Klinger, C.; Rumpf, N.; Strehl, U. Neurofeedback for children with ADHD: A comparison of SCP and theta/beta protocols. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 2007 , 32 , 73–88. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Cortese, S.; Ferrin, M.; Brandeis, D.; Holtmann, M.; Aggensteiner, P.; Daley, D.; Santosh, P.; Simonoff, E.; Stevenson, J.; Stringaris, A.; et al. Neurofeedback for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Meta-Analysis of clinical and neuropsychological outcomes from randomized controlled trials. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016 , 55 , 444–455. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Logemann, H.N.; Lansbergen, M.M.; Van Os, T.W.; Bocker, K.B.; Kenemans, J.L. The effectiveness of EEG-feedback on attention, impulsivity and EEG: A sham feedback controlled study. Neurosci. Lett. 2010 , 479 , 49–53. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Holtmann, M.; Pniewski, B.; Wachtlin, D.; Wörz, S.; Strehl, U. Neurofeedback in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)–A controlled multicenter study of a non-pharmacological treatment approach. BMC Pediatrics 2014 , 14 , 202. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Su, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Fang, F.; Xu, T.; Lu, H.; Xie, L.; Zhuo, J.; Qu, J.; Yang, L.; et al. Remission rate and functional outcomes during a 6-month treatment with osmotic-release oral-system methylphenidate in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2015 , 35 , 525–534. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Blume, F.; Hudak, J.; Dresler, T.; Ehlis, A.C.; Kühnhausen, J.; Renner, T.J.; Gawrilow, C. NIRS-based neurofeedback training in a virtual reality classroom for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2017 , 18 , 41. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ] [ Green Version ]

Click here to enlarge figure

| MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

Share and Cite

Cabaleiro, P.; Cueli, M.; Cañamero, L.M.; González-Castro, P. A Case Study in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: An Innovative Neurofeedback-Based Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022 , 19 , 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010191

Cabaleiro P, Cueli M, Cañamero LM, González-Castro P. A Case Study in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: An Innovative Neurofeedback-Based Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health . 2022; 19(1):191. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010191

Cabaleiro, Paloma, Marisol Cueli, Laura M. Cañamero, and Paloma González-Castro. 2022. "A Case Study in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: An Innovative Neurofeedback-Based Approach" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 1: 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010191

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

0203 326 9160

Childhood ADHD – Luke’s story

Posted on Thursday, 05 April 2018, in Child & Teen ADHD

In the final part of her ADHD series, Dr Sabina Dosani, Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist and Clinical Partner London, introduces Luke, a patient she was able to help with his ADHD.

ADHD is one of the most common diagnoses for children in the UK and it is thought that 1 in 10 children will display some signs. For some children, their ADHD is severe and can have a huge impact on their ability to engage in school and to build and sustain relationships. Left untreated, evidence shows that those with ADHD are more likely to get into car accidents, engage in criminal activity and may struggle to keep a job or maintain relationships.

Luke, aged six, gets into trouble a lot at school. His mother gets called by his teacher three or four times a week for incidents of fighting, kicking and running in corridors. He is unable to finish his work and becomes quickly distracted. At home, he seems unable to sit still for any length of time, has had several falls when climbing trees and needs endless prompts to tidy his toys.

At school, he annoys his classmates by his constant interruptions, however if he has one-to-one attention from a student teacher who happens to be in his class on a placement he is able to settle and finish the work set. His father was said to have been a ‘lively’ child, then a ‘bright underachiever’ who occasionally fell foul of the law.

The school thought a visit to the GP might be a good idea. At the GP surgery, Luke ran and jumped about making animal noises. He swung on the back legs of a chair and took the batteries out of an ophthalmoscope. He was referred to a me for an assessment.

After a careful assessment, which included collecting information from school, questionnaires and observations of Luke, a diagnosis of ADHD was made. Following a discussion of the treatment options, the family decided they did not want any medication.

The first-line treatment for school‑age children and young people with severe ADHD and severe impairment is drug treatment. If the family doesn’t want to try a pharmaceutical, a psychological intervention alone is offered but drug treatment has more benefits and is superior to other treatments for children with severe ADHD.

Luke's mother was asked to list the behaviours that most concern her. She was encouraged to accept others like making noises or climbing as part of Luke’s development as long as it is safe.

Now, when Luke fights, kicks others or takes risks like running into the road he is given “time-out” which isolates him for a short time and allows him and his parents or teacher to calm down. To reduce aggression and impulsivity, Luke is taught to respond verbally rather than physically and channel energy into activities such as sports or energetic percussion playing.

Over time, Luke’s parents have become skilled at picking their battles. Home is more harmonious. They fenced their garden, fitted a childproof gate and cut some branches off a tree preventing him climbing it. His parents are concerned about Luke’s use of bad language. They have been supported to allow verbal responses as a short-term interim. Whilst these might be unacceptable in other children they are preferable to physical aggression.

At school, Luke is less aggressive, has a statement of special educational need and now works well with a classroom assistant. He has been moved to the front of the class, where the teacher can keep a close eye on him, and given one task at a time. He is given special tasks, like taking the register to the school office, so he can leave class without being expected to sit still for long periods.

Through parental training, Luke’s parents have been able to help Luke work with his challenges to better manage them. As Luke grows and develops and as he faces new challenges in life, Luke may need to revisit the efficacy of ADHD medication. His parents now feel a lot more confident in being able to help Luke and he is a happier child and more settled.

Dr Sabina Dosani Consultant Child & Adolescent Psychiatrist

Dr Sabina Dosani is a highly experienced Consultant Psychiatrist currently working for the Anna Freud Centre looking after Children and Adolescents. She has a Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery as well as being a member of the Royal College of Psychiatrists . Dr Dosani also has a certificate in Systemic Practice (Family Therapy).

Related Articles

- The real reason you need to take adult ADHD seriously

- 10 signs your child might have ADHD

- What causes ADHD?

- Why is ADHD in women undiagnosed so often?

- Anxiety & Stress (14)

- Behavioural Issues (5)

- Bipolar Disorder (3)

- Child Autism (14)

- Child & Teen ADHD (7)

- Child & Teen Anxiety (12)

- Child & Teen Depression (3)

- Depression (3)

- Eating Disorders (2)

- Education & Mental Health (2)

- Maternal Health (2)

- Parenting & Families (16)

- Treatments & Therapy (20)

Already a patient?

Sign in to manage your care

Learn more and see openings

Work with us as a clinician?

Sign in to your clinician portal

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 12 August 2020

Females with ADHD: An expert consensus statement taking a lifespan approach providing guidance for the identification and treatment of attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder in girls and women

- Susan Young ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8494-6949 1 , 2 ,

- Nicoletta Adamo 3 , 4 ,

- Bryndís Björk Ásgeirsdóttir 2 ,

- Polly Branney 5 ,

- Michelle Beckett 6 ,

- William Colley 7 ,

- Sally Cubbin 8 ,

- Quinton Deeley 9 , 10 ,

- Emad Farrag 11 ,

- Gisli Gudjonsson 2 , 12 ,

- Peter Hill 13 ,

- Jack Hollingdale 14 ,

- Ozge Kilic 15 ,

- Tony Lloyd 16 ,

- Peter Mason 17 ,

- Eleni Paliokosta 18 ,

- Sri Perecherla 19 ,

- Jane Sedgwick 3 , 20 ,

- Caroline Skirrow 21 , 22 ,

- Kevin Tierney 23 ,

- Kobus van Rensburg 24 &

- Emma Woodhouse 10 , 25

BMC Psychiatry volume 20 , Article number: 404 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

231k Accesses

149 Citations

700 Altmetric

Metrics details

There is evidence to suggest that the broad discrepancy in the ratio of males to females with diagnosed ADHD is due, at least in part, to lack of recognition and/or referral bias in females. Studies suggest that females with ADHD present with differences in their profile of symptoms, comorbidity and associated functioning compared with males. This consensus aims to provide a better understanding of females with ADHD in order to improve recognition and referral. Comprehensive assessment and appropriate treatment is hoped to enhance longer-term clinical outcomes and patient wellbeing for females with ADHD.

The United Kingdom ADHD Partnership hosted a meeting of experts to discuss symptom presentation, triggers for referral, assessment, treatment and multi-agency liaison for females with ADHD across the lifespan.

A consensus was reached offering practical guidance to support medical and mental health practitioners working with females with ADHD. The potential challenges of working with this patient group were identified, as well as specific barriers that may hinder recognition. These included symptomatic differences, gender biases, comorbidities and the compensatory strategies that may mask or overshadow underlying symptoms of ADHD. Furthermore, we determined the broader needs of these patients and considered how multi-agency liaison may provide the support to meet them.

Conclusions

This practical approach based upon expert consensus will inform effective identification, treatment and support of girls and women with ADHD. It is important to move away from the prevalent perspective that ADHD is a behavioural disorder and attend to the more subtle and/or internalised presentation that is common in females. It is essential to adopt a lifespan model of care to support the complex transitions experienced by females that occur in parallel to change in clinical presentation and social circumstances. Treatment with pharmacological and psychological interventions is expected to have a positive impact leading to increased productivity, decreased resource utilization and most importantly, improved long-term outcomes for girls and women.

Peer Review reports

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common neurodevelopmental condition described in diagnostic classification systems (ICD-10, DSM-5 [ 1 , 2 ]). It is characterised by difficulties in two subdomains: inattention, and hyperactivity-impulsivity. Three primary subtypes can be identified: predominantly inattentive, hyperactive-impulsive, and combined presentations. Symptoms persist over time, pervade across situations and cause significant impairment [ 3 ].

ADHD is present in childhood and symptoms tend to decline with increasing age [ 4 ], with consistent reductions documented in hyperactive-impulsive symptoms but more mixed results regarding the decline in inattentive symptoms [ 5 , 6 , 7 ]. This trajectory does not appear to be different in affected males or females [ 6 , 8 ]. A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies published in 2005 showed that up to one-third of childhood cases continued to meet full diagnostic criteria into their 20s, with around 65% continuing to experience impairing symptoms [ 9 ]. More recent studies in large clinical cohorts indicate that persistence of ADHD into adulthood may be much more common. Two studies from child mental health clinics in the UK and the Netherlands have reported persistence in around 80% of children with the combined type presentation into early adulthood [ 10 , 11 ], potentially relating to the high severity of ADHD in this group and the use of more objective ratings [ 12 ]. The proportion meeting full diagnostic criteria for ADHD then continues to decline in adult samples [ 13 ]. Simultaneously, experiences of ADHD symptoms often change over the course of development: hyperactivity may be replaced by feelings of ‘inner restlessness’ and discomfort; inattention may manifest as difficulty completing chores or work-based activities (e.g. filling out forms, remembering appointments, meeting deadlines) [ 1 ].

Psychiatric comorbidity is very common, which may complicate identification and treatment [ 14 ]. In children with ADHD this includes conduct disorder (CD), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), developmental coordination disorder, tic disorders, anxiety and depressive disorders, reading disorders, and learning and language disorders [ 15 , 16 , 17 ]. Comorbid conditions are also extremely common in adults and include ASD, anxiety and depressive disorders, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, obsessive compulsive disorder, substance use disorders, personality disorders, and impulse control disorders [ 18 , 19 ].

Prevalence of ADHD is estimated at 7.1% in children and adolescents [ 20 ], and 2.5-5% in adults [ 4 , 21 ], and around 2.8% in older adults [ 22 ]. Sex differences in the prevalence of ADHD are well documented. Clinical referrals in boys typically exceed those for girls, with ratios ranging from 3-1 to 16-1 [ 23 ]. The discrepancy of ADHD rates in community samples remains significant, although it is less extreme, at around a 3-1 ratio of boys to girls [ 4 ]. Nevertheless the discrepancy in the sex-ratio between clinic and community samples highlights that a large number of girls with ADHD are likely to remain unidentified and untreated, with implications for long-term social, educational and mental health outcomes [ 24 ].

This disparity in prevalence between boys and girls may stem from a variety of potential factors. The contribution of greater genetic vulnerability, endocrine factors, psychosocial contributors, or a propensity to respond negatively to certain early life stressors in boys have been proposed or investigated as potential contributors to sexual dimorphism in prevalence and presentation [ 25 , 26 ]. Whilst in childhood there is a clear male preponderance of ADHD, in adult samples sex differences in prevalence are more modest or absent [ 21 , 27 , 28 , 29 ]. This may be due to a variety of factors, with potential contributions from the greater reliance on self-report in older samples, greater persistence in females alongside increased levels of remission in males, and potentially more common late onset cases in females [ 25 , 26 , 28 ].

Comprehensive views of the aetiology of ADHD incorporate biological, environmental and cultural perspectives and influences [ 25 ]. Substantial genetic influences have been identified in ADHD [ 30 ]. Individuals who have ADHD are more likely to have children, parents and/or siblings with ADHD [ 31 , 32 ]. The ‘female protective effect’ theory suggests that girls and women may need to reach a higher threshold of genetic and environmental exposures for ADHD to be expressed, thereby accounting for the lower prevalence in females and the higher familial transmission rates seen in families where females are affected [ 33 , 34 ]. Research suggests that siblings of affected girls have more ADHD symptoms compared with siblings of affected boys [ 33 , 34 ].

There is increasing recognition that females with ADHD show a somewhat modified set of behaviours, symptoms and comorbidities when compared with males with ADHD; they are less likely to be identified and referred for assessment and thus their needs are less likely to be met. It is unknown how often a diagnosis of ADHD is being missed or misdiagnosed in females, but it has become clear that a better understanding of ADHD in girls and women is needed if we are to improve their longer-term wellbeing and functional and clinical outcomes [ 35 , 36 ].

This report provides a selective review the research literature on ADHD in girls and women, and aims to provide guidance to improve identification, treatment and support for girls and women with ADHD across the lifespan, developed through a multidisciplinary consensus meeting according to the clinical expertise and knowledge among attendees. To support medical and mental health practitioners in their understanding of ADHD in females, we provide consensus guidance on the presentation of ADHD in females and triggers for referral. We establish specific advice regarding the assessment, interventions, and multi-agency liaison needs in girls and women with ADHD.

In line with previous definitions, we use the terms sex to identify a biological category (male/female), and gender to define a social role and cultural-social properties [ 37 ]. However, we acknowledge the complex differences between the sexes that occur independently of ADHD status [ 38 ], and discuss both biological differences and social roles in the current consensus.

The consensus aimed to provide practical guidance to professionals working with girls and women with ADHD, drawing on the scientific literature and the professional experience of the authors. To achieve this aim, professionals specialising in ADHD convened in London on 30th November 2018 for a meeting hosted by the United Kingdom ADHD Partnership (UKAP; www.UKADHD.com ). Meeting attendees included experts in ADHD across a range of mental health professions, including healthcare specialists (nursing; general practice; child, adolescent and adult psychiatry; clinical and forensic psychology; counselling), academic, educational and occupational specialists. Service-users and ADHD charity workers were also represented. Attendees engaged in discussions throughout the day, with the aim of reaching consensus.

The meeting commenced with presentations of preliminary data obtained from (1) an ongoing systematic review on the clinical and psychosocial presentation of females in comparison with males with ADHD (currently being led by SY and OK); and (2) epidemiological research on sex differences in self-reported ADHD symptoms in population based adolescent cohorts. Following a question and answer session, attendees then separated into three breakout groups. Each group was tasked with providing practical solutions relevant to their assigned topic. Discussions were facilitated by group leaders and summarized by note-takers. Following the small-group work, all attendees re-assembled. Group leaders then presented findings to all meeting attendees for another round of discussion and debate, until consensus was reached. Group discussions included the following themes:

1: Identification and assessment of ADHD in females

Presentation in females and what might trigger referral?

Considering sex differences when conducting ADHD assessments

2: Interventions and treatments for ADHD in females

Pharmacological

Non-pharmacological

3: Multi-agency liaison

Educational considerations

Other multi-agency considerations

Taking a lifespan perspective, each theme was explored in relation to specific age groups considered to be associated with pertinent periods for environmental and biological change, and change in clinical needs and presentation. Recommendations that differed between age groups are presented separately.

The consensus group incorporated evidence from a broad range of sources. However, the assessment, pharmacological treatment, and multiagency support features reflect clinical practice and legislature in the United Kingdom (UK), and may differ in other countries.