- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Discourse Analysis – Methods, Types and Examples

Discourse Analysis – Methods, Types and Examples

Table of Contents

Discourse Analysis

Definition:

Discourse Analysis is a method of studying how people use language in different situations to understand what they really mean and what messages they are sending. It helps us understand how language is used to create social relationships and cultural norms.

It examines language use in various forms of communication such as spoken, written, visual or multi-modal texts, and focuses on how language is used to construct social meaning and relationships, and how it reflects and reinforces power dynamics, ideologies, and cultural norms.

Types of Discourse Analysis

Some of the most common types of discourse analysis are:

Conversation Analysis

This type of discourse analysis focuses on analyzing the structure of talk and how participants in a conversation make meaning through their interaction. It is often used to study face-to-face interactions, such as interviews or everyday conversations.

Critical discourse Analysis

This approach focuses on the ways in which language use reflects and reinforces power relations, social hierarchies, and ideologies. It is often used to analyze media texts or political speeches, with the aim of uncovering the hidden meanings and assumptions that are embedded in these texts.

Discursive Psychology

This type of discourse analysis focuses on the ways in which language use is related to psychological processes such as identity construction and attribution of motives. It is often used to study narratives or personal accounts, with the aim of understanding how individuals make sense of their experiences.

Multimodal Discourse Analysis

This approach focuses on analyzing not only language use, but also other modes of communication, such as images, gestures, and layout. It is often used to study digital or visual media, with the aim of understanding how different modes of communication work together to create meaning.

Corpus-based Discourse Analysis

This type of discourse analysis uses large collections of texts, or corpora, to analyze patterns of language use across different genres or contexts. It is often used to study language use in specific domains, such as academic writing or legal discourse.

Descriptive Discourse

This type of discourse analysis aims to describe the features and characteristics of language use, without making any value judgments or interpretations. It is often used in linguistic studies to describe grammatical structures or phonetic features of language.

Narrative Discourse

This approach focuses on analyzing the structure and content of stories or narratives, with the aim of understanding how they are constructed and how they shape our understanding of the world. It is often used to study personal narratives or cultural myths.

Expository Discourse

This type of discourse analysis is used to study texts that explain or describe a concept, process, or idea. It aims to understand how information is organized and presented in such texts and how it influences the reader’s understanding of the topic.

Argumentative Discourse

This approach focuses on analyzing texts that present an argument or attempt to persuade the reader or listener. It aims to understand how the argument is constructed, what strategies are used to persuade, and how the audience is likely to respond to the argument.

Discourse Analysis Conducting Guide

Here is a step-by-step guide for conducting discourse analysis:

- What are you trying to understand about the language use in a particular context?

- What are the key concepts or themes that you want to explore?

- Select the data: Decide on the type of data that you will analyze, such as written texts, spoken conversations, or media content. Consider the source of the data, such as news articles, interviews, or social media posts, and how this might affect your analysis.

- Transcribe or collect the data: If you are analyzing spoken language, you will need to transcribe the data into written form. If you are using written texts, make sure that you have access to the full text and that it is in a format that can be easily analyzed.

- Read and re-read the data: Read through the data carefully, paying attention to key themes, patterns, and discursive features. Take notes on what stands out to you and make preliminary observations about the language use.

- Develop a coding scheme : Develop a coding scheme that will allow you to categorize and organize different types of language use. This might include categories such as metaphors, narratives, or persuasive strategies, depending on your research question.

- Code the data: Use your coding scheme to analyze the data, coding different sections of text or spoken language according to the categories that you have developed. This can be a time-consuming process, so consider using software tools to assist with coding and analysis.

- Analyze the data: Once you have coded the data, analyze it to identify patterns and themes that emerge. Look for similarities and differences across different parts of the data, and consider how different categories of language use are related to your research question.

- Interpret the findings: Draw conclusions from your analysis and interpret the findings in relation to your research question. Consider how the language use in your data sheds light on broader cultural or social issues, and what implications it might have for understanding language use in other contexts.

- Write up the results: Write up your findings in a clear and concise way, using examples from the data to support your arguments. Consider how your research contributes to the broader field of discourse analysis and what implications it might have for future research.

Applications of Discourse Analysis

Here are some of the key areas where discourse analysis is commonly used:

- Political discourse: Discourse analysis can be used to analyze political speeches, debates, and media coverage of political events. By examining the language used in these contexts, researchers can gain insight into the political ideologies, values, and agendas that underpin different political positions.

- Media analysis: Discourse analysis is frequently used to analyze media content, including news reports, television shows, and social media posts. By examining the language used in media content, researchers can understand how media narratives are constructed and how they influence public opinion.

- Education : Discourse analysis can be used to examine classroom discourse, student-teacher interactions, and educational policies. By analyzing the language used in these contexts, researchers can gain insight into the social and cultural factors that shape educational outcomes.

- Healthcare : Discourse analysis is used in healthcare to examine the language used by healthcare professionals and patients in medical consultations. This can help to identify communication barriers, cultural differences, and other factors that may impact the quality of healthcare.

- Marketing and advertising: Discourse analysis can be used to analyze marketing and advertising messages, including the language used in product descriptions, slogans, and commercials. By examining these messages, researchers can gain insight into the cultural values and beliefs that underpin consumer behavior.

When to use Discourse Analysis

Discourse analysis is a valuable research methodology that can be used in a variety of contexts. Here are some situations where discourse analysis may be particularly useful:

- When studying language use in a particular context: Discourse analysis can be used to examine how language is used in a specific context, such as political speeches, media coverage, or healthcare interactions. By analyzing language use in these contexts, researchers can gain insight into the social and cultural factors that shape communication.

- When exploring the meaning of language: Discourse analysis can be used to examine how language is used to construct meaning and shape social reality. This can be particularly useful in fields such as sociology, anthropology, and cultural studies.

- When examining power relations: Discourse analysis can be used to examine how language is used to reinforce or challenge power relations in society. By analyzing language use in contexts such as political discourse, media coverage, or workplace interactions, researchers can gain insight into how power is negotiated and maintained.

- When conducting qualitative research: Discourse analysis can be used as a qualitative research method, allowing researchers to explore complex social phenomena in depth. By analyzing language use in a particular context, researchers can gain rich and nuanced insights into the social and cultural factors that shape communication.

Examples of Discourse Analysis

Here are some examples of discourse analysis in action:

- A study of media coverage of climate change: This study analyzed media coverage of climate change to examine how language was used to construct the issue. The researchers found that media coverage tended to frame climate change as a matter of scientific debate rather than a pressing environmental issue, thereby undermining public support for action on climate change.

- A study of political speeches: This study analyzed political speeches to examine how language was used to construct political identity. The researchers found that politicians used language strategically to construct themselves as trustworthy and competent leaders, while painting their opponents as untrustworthy and incompetent.

- A study of medical consultations: This study analyzed medical consultations to examine how language was used to negotiate power and authority between doctors and patients. The researchers found that doctors used language to assert their authority and control over medical decisions, while patients used language to negotiate their own preferences and concerns.

- A study of workplace interactions: This study analyzed workplace interactions to examine how language was used to construct social identity and maintain power relations. The researchers found that language was used to construct a hierarchy of power and status within the workplace, with those in positions of authority using language to assert their dominance over subordinates.

Purpose of Discourse Analysis

The purpose of discourse analysis is to examine the ways in which language is used to construct social meaning, relationships, and power relations. By analyzing language use in a systematic and rigorous way, discourse analysis can provide valuable insights into the social and cultural factors that shape communication and interaction.

The specific purposes of discourse analysis may vary depending on the research context, but some common goals include:

- To understand how language constructs social reality: Discourse analysis can help researchers understand how language is used to construct meaning and shape social reality. By analyzing language use in a particular context, researchers can gain insight into the cultural and social factors that shape communication.

- To identify power relations: Discourse analysis can be used to examine how language use reinforces or challenges power relations in society. By analyzing language use in contexts such as political discourse, media coverage, or workplace interactions, researchers can gain insight into how power is negotiated and maintained.

- To explore social and cultural norms: Discourse analysis can help researchers understand how social and cultural norms are constructed and maintained through language use. By analyzing language use in different contexts, researchers can gain insight into how social and cultural norms are reproduced and challenged.

- To provide insights for social change: Discourse analysis can provide insights that can be used to promote social change. By identifying problematic language use or power imbalances, researchers can provide insights that can be used to challenge social norms and promote more equitable and inclusive communication.

Characteristics of Discourse Analysis

Here are some key characteristics of discourse analysis:

- Focus on language use: Discourse analysis is centered on language use and how it constructs social meaning, relationships, and power relations.

- Multidisciplinary approach: Discourse analysis draws on theories and methodologies from a range of disciplines, including linguistics, anthropology, sociology, and psychology.

- Systematic and rigorous methodology: Discourse analysis employs a systematic and rigorous methodology, often involving transcription and coding of language data, in order to identify patterns and themes in language use.

- Contextual analysis : Discourse analysis emphasizes the importance of context in shaping language use, and takes into account the social and cultural factors that shape communication.

- Focus on power relations: Discourse analysis often examines power relations and how language use reinforces or challenges power imbalances in society.

- Interpretive approach: Discourse analysis is an interpretive approach, meaning that it seeks to understand the meaning and significance of language use from the perspective of the participants in a particular discourse.

- Emphasis on reflexivity: Discourse analysis emphasizes the importance of reflexivity, or self-awareness, in the research process. Researchers are encouraged to reflect on their own positionality and how it may shape their interpretation of language use.

Advantages of Discourse Analysis

Discourse analysis has several advantages as a methodological approach. Here are some of the main advantages:

- Provides a detailed understanding of language use: Discourse analysis allows for a detailed and nuanced understanding of language use in specific social contexts. It enables researchers to identify patterns and themes in language use, and to understand how language constructs social reality.

- Emphasizes the importance of context : Discourse analysis emphasizes the importance of context in shaping language use. By taking into account the social and cultural factors that shape communication, discourse analysis provides a more complete understanding of language use than other approaches.

- Allows for an examination of power relations: Discourse analysis enables researchers to examine power relations and how language use reinforces or challenges power imbalances in society. By identifying problematic language use, discourse analysis can contribute to efforts to promote social justice and equality.

- Provides insights for social change: Discourse analysis can provide insights that can be used to promote social change. By identifying problematic language use or power imbalances, researchers can provide insights that can be used to challenge social norms and promote more equitable and inclusive communication.

- Multidisciplinary approach: Discourse analysis draws on theories and methodologies from a range of disciplines, including linguistics, anthropology, sociology, and psychology. This multidisciplinary approach allows for a more holistic understanding of language use in social contexts.

Limitations of Discourse Analysis

Some Limitations of Discourse Analysis are as follows:

- Time-consuming and resource-intensive: Discourse analysis can be a time-consuming and resource-intensive process. Collecting and transcribing language data can be a time-consuming task, and analyzing the data requires careful attention to detail and a significant investment of time and resources.

- Limited generalizability: Discourse analysis is often focused on a particular social context or community, and therefore the findings may not be easily generalized to other contexts or populations. This means that the insights gained from discourse analysis may have limited applicability beyond the specific context being studied.

- Interpretive nature: Discourse analysis is an interpretive approach, meaning that it relies on the interpretation of the researcher to identify patterns and themes in language use. This subjectivity can be a limitation, as different researchers may interpret language data differently.

- Limited quantitative analysis: Discourse analysis tends to focus on qualitative analysis of language data, which can limit the ability to draw statistical conclusions or make quantitative comparisons across different language uses or contexts.

- Ethical considerations: Discourse analysis may involve the collection and analysis of sensitive language data, such as language related to trauma or marginalization. Researchers must carefully consider the ethical implications of collecting and analyzing this type of data, and ensure that the privacy and confidentiality of participants is protected.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Cluster Analysis – Types, Methods and Examples

Discriminant Analysis – Methods, Types and...

MANOVA (Multivariate Analysis of Variance) –...

Documentary Analysis – Methods, Applications and...

ANOVA (Analysis of variance) – Formulas, Types...

Graphical Methods – Types, Examples and Guide

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Exploring the role of discourse in marketing and consumer research

2014, Journal of Consumer Behaviour

Related Papers

Organization

Robert Chia

Baramee Kheovichai

Christoph Gutknecht

Janet Holmes

Discourse Approaches to Politics, Society and Culture

Jaffer Sheyholislami

claire roederer

Review of Research in Education

The Journal of Consumer Research

Journal of Second Language Writing

Diane Belcher

Management Communication Quarterly

Elizabeth K . Eger

RELATED PAPERS

Maria Teresa V N Abdo

Gestion Y Politica Publica

Israel Velasco

Journal of Pedagogy

Heny Djoehaeni

Law, Technology and Humans

Pamela Ugwudike

IDS Bulletin

Tim Kelsall

Flavien Falantin

Ari Nuraeni

Ornella Pacifico

Rodica Soare

Emerging Infectious Diseases

Ariana Perez

Vera Valdemarin

Bayburt Aktuel Dergisi

Bayburt Gündem

Journal of the Chemical Society D: Chemical Communications

Loren Barber

Carlos Antonio Mondino Silva

Anesthesia & Analgesia

Anette Severing

Masalah-Masalah Hukum

imam koeswahyono

George Rajna

Revista Española de Cardiología

Leonardo Zambrano

Neurobiology of Disease

Jurgen Del Favero

Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy

Mehreen Anjum

Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences

Minakshi sharma

IEEE Transactions on Magnetics

Brock Huntsman

International Journal of Pharmaceutics

Sudaxshina Murdan

L. Verderame, A New Set of Strings for the Lute of Dada, Rivista degli studi orientali 96/2–4 (2023), pp. 243–247

Lorenzo Verderame

See More Documents Like This

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Exploring the role of discourse in marketing and consumer research

Summary ( 3 min read), introduction.

- Marketing and consumption depend largely on discourse for the creation, ordering, dissemination and reinforcement of product knowledge.

- In its modern reconfiguration marketing and consumer research theory has, the authors would argue, been less compatible with discourse based readings because of the ontological status of the consumer as a sovereign, autonomous and individuated agency who has freedom to act in accordance with his or her own interests in the market.

- Critical marketing offers a number of appealing directions for discourse based readings although controversial questions remain over the extent to which the distance that critical marketers seek to establish is actually a separation of some sorts.

- The authors intention in this paper is to advance the use of discourse analysis both as a critical mirror and methodological lens for marketing and consumer researchers.

- Upon this broad conception of discourse the authors set about to introduce, position, distinguish and develop discourse analysis as a pathway to disciplinary reflexivity and empirical insight.

Consumption and markets as text

- There was a growing interest in discourse based approaches among some consumer researchers and, to a lesser extent marketing research, in the 1980s and 1990s, following and mirroring a much broader trend in the social sciences and humanities.

- This broad movement sought to focus analysis on a range of text and discourse practices, including text production, dissemination and 10 communication, and consumption.

- This preference for analysing advertising text is probably a major factor that has limited the development of more varied approaches to discourse and discourse analysis in other areas of consumer research such as considering other types of text and broader notions of discourse beyond the study of advertisements (Humphreys, 2010a; Kelly et al., 2005).

- A recurring tension however remains around how to conceptualise and render the power of discourse to shape and frame consumer experience on the one hand (for example Tuncay 14 Zayer et al 2012), and the capacity of consumers to utilise the opportunities made possible by the fluid potentiality of discourse to actualise their own identities.

- Discourse Analysis demonstrates and re-emphasises clear synergies and links within marketing academia, especially between Critical marketing, macromarketing and consumer culture theory.

Orientating Discourse Analysis to Marketing and Consumer Research

- There are a variety of styles and uses of discourse analysis (Alvesson and Karreman.

- This section seeks to illuminate three key approaches, distinguished by their technical, constitutive and political research orientations (Table 1), and elaborating on the possible ways they might be employed in marketing (Table 2).

- The rationale for this relational categorisation is that discourse constitutes knowledge of subjects in relationships and that, similarly, discourse is both content and relational context (Boje at al., 2004).

- Interpretations of marketing/consumer discourse do not stand alone from the relational contexts in which they are situated.

Technical orientation to DA

- First, associated with ethnomethodology and conversation analysis, are approaches where discourse is taken as a technical interaction produced in the skilled accomplishment of everyday social life (Garfinkel, 1967; Gergen 1999; Goffman, 1974; Schegloff, 1992; Sinclair and Coultard, 1975).

- The unit of analysis – commonly, but not exclusively, ‘talk’ – is examined through a technical, micro-linguistic lens (Schegloff, 1992), identifying the rules that govern the organisation of talk such as “speech rights” and “turn-taking” (i.e. who may talk next and when).

- Consumer researchers would be attuned to grammatical structures like cues, turn-taking, discourse markers (but, however), personal pronouns (me, I), as well as more complex linguistic forms such as juxtapositions (good/bad), rhetorical devices, metaphors (linking concepts), metonyms and even narratives (ideal story types) that organise local consumer texts.

- These linguistic features are interpreted for the organising function they play in certain market relationships.

Constitutive orientation to DA

- The second cluster of DA picks up on this observation that discourse not only creates rules of talk in local texts but is constitutive of social reality (Berger and Luckmann, 1971; Potter and Wetherell, 1987; Wetherell, 1998).

- Analysis at this level consequently concerns the situated nature of the text under investigation, not only in terms of who it is produced by and for but how it is produced by drawing upon wider social discourses.

- Macromarketing researchers interested in how relations between marketing and society have evolved (see Fougère and Skålén 2013) can examine how historical social discourses (e.g. the ‘free market’, ‘economy’ and ‘social justice’) employed in key texts, (re-)constitute certain kinds of marketing-society relations, such as ‘social capitalism’, ‘social marketing’, ‘sustainable development’ or ‘ethical consumption’.

- How consumers integrate these discourses into their own accounts, how they use them to connect their self to or, contrastingly, disassociate their self from products, brands, corporations, and other consumers (Holt, 2002) are fruitful avenues here.

- With a concern for content-context dynamics, this orientation to DA also provides marketing research with a means to examine marketing subjectivities and relations within corporations.

Political orientation to DA

- The technical and constitutive orientations to DA can be seen as implicitly critical views in the sense that they challenge functionalist assumptions about marketing subjects independent of discourses that render them knowable in some way.

- Yet they do not begin with or focus on critical questions.

- In exploring market-society relations, for example, Schroeder and Borgerson (1999) show how marketing texts commodify Hawaii for western tourist consumers by drawing upon a dominant paradisal, neo-colonial discourses of the ‘exotic other’.

Framing Critical Discourse Analysis for Marketing

- Drawing upon contributions from sociology, consumer and organisational research.the authors.

- The interpretive context constructed in this dialectic hails to consumers (Parker, 1992), as hardworking, economically concerned patriots, to “reject climate regulation and keep filing up your cars at the pump!”.

- Power may be interpreted by analysts along different relational axes (see Table 2.) and between subjects who are present as well as those ostensibly absent from the same discourse.

- Third, they show how the consumer’s use of an ‘independent guidebook’ – a toolkit for ‘how to do’ independent tourism- paradoxically engenders dependency in tourist’s relations with the market.

Opening up consumer discourse

- Its 25 ‘de-naturalising’ agenda (Kress, 1990) renders CDA uniquely poised to help analysts understand how marketing discourse renders certain consumer realities ‘seeable’, whilst others ‘unseeable’.

- Caruana and Crane (2008), for instance, show how the marketing discourse of ‘Responsible Tourism’ depicts tourist practices and relations with local people and ecosystems as responsible, ‘trouble and guilt-free’.

- CDA can be used here to highlight paradox and contradiction as well as the processes that sustain their subversion.

- Yet at the same time, the discipline – as a conventional ‘way of knowing’ markets and ‘being marketers’ - is essentially constituted by and from a constellation of heuristic devices, concepts and definitions that reify marketing as a self-evidently natural subject (Hackley, 2003).

Conclusions

- Discourse analysis, and CDA in particular, offers a valuable methodological and epistemological direction for marketers who, while willing to subject the mainstream marketing discourse to scrutiny and analysis are also able to examine some of the reasons why dominant discourses about marketing remain powerful and widely accepted.

- This broader view opens up a whole range of 27 empirical, conceptual and ethical questions, for instance, concerning the cultural functions of various marketing texts, how consumers and marketers construct and are constructed in them, how important objects and relationships are legitimized and sustained and how power relations operate therein.

- As Humphreys (2010b) demonstrates, analysis of discourse can illustrate market-making and creation, i.e. as products of certain discourse practices.

- Djavlonbek and Varey (2013) illustrate these kinds of outcomes in their examination of green consumer behaviour, showing how meaning structures (interaction and discourse) in this context reproduce inconsistent behaviour as necessary and practical outcomes of a market structure.

Did you find this useful? Give us your feedback

Figures ( 2 )

Content maybe subject to copyright Report

123 citations

100 citations

View 3 citation excerpts

Cites background from "Exploring the role of discourse in ..."

... Discourse-based analysis provides an approach for reflecting on marketing thought, especially ‘amongst countervailing discourses’ on sustainable consumption, the environment and justice, for example (Fitchett & Caruana, 2015, p. 2). ...

... Further, discourse analysis allows a reflection and identification of the wider political and economic assumptions in marketing thought (Fitchett & Caruana, 2015). ...

... In the same vein, similar contentious concepts such as consumer–citizen divide and consumer sovereignty (Fitchett & Caruana, 2015; Sandberg & Polsa, 2015) should be reflected upon through discourse-based analysis to understand the power dynamics and various conceptualisations at play. ...

45 citations

32 citations

View 1 citation excerpt

Cites methods from "Exploring the role of discourse in ..."

... In this paper, we analyse marketing of PST through parents’ consumer narratives (Fitchett and Caruana 2015) published on the website of one of the largest PST companies in Sweden. ...

26 citations

View 5 citation excerpts

... Multiple sources also allow a broader understanding of the phenomenon by creating informative patterns (Besley, 2015; Fitchett & Caruana, 2015; Gee, 2005; Olsson & Heizmann, 2015; Thompson, 2004; Wetherell, 1998). ...

... The concept of intertextuality importantly allows such diverse texts to be viewed relationally, which adds multiplicity of relevance (Allen, 2011; Joy & Li, 2012; Fitchett & Caruana, 2015). ...

... Reproducing social and cultural perspectives but self-structured towards on-site uses (Caruana & Crane, 2008; Thompson, 2004), which make consumers, institutions and groups behave in certain ways (Fitchett & Caruana, 2015). ...

... 3.3.8 Presentation of the Cool Self Micro-level practices also create discourses which derive from every day occurrences, although it is unclear where they originate from and who propagates them (Fitchett & Caruana, 2015). ...

... 4.3.2 Literary and Textual Analysis Literary, cultural, market and consumer texts are legitimate sources for research in CCT as they improve understanding of phenomena (Fitchett, et al., 2014; Fitchett & Caruana, 2015; Joy & Lin, 2012; Macinnes & Folkes, 2009). ...

16,935 citations

11,533 citations

View 1 reference excerpt

"Exploring the role of discourse in ..." refers background in this paper

... Technical orientation to DA First, associated with ethnomethodology and conversation analysis, are approaches where discourse is taken as a technical interaction produced in the skilled accomplishment of everyday social life (Garfinkel, 1967; Goffman, 1974; Sinclair and Coulthard, 1975; Schegloff, 1992; Gergen, 1999). ...

9,210 citations

7,012 citations

4,972 citations

Related Papers (5)

Frequently asked questions (14), q1. what are the contributions mentioned in the paper "exploring the role of discourse in marketing and consumer research" .

This paper reviews the development of discourse based analysis in marketing and consumer research and outlines the application of various forms of discourse analysis ( DA ) as an approach. The paper locates this development alongside broader disciplinary movements and restates the potential for Critical Discourse Analysis ( CDA ) in marketing and consumer behaviour research. The authors argue that discourse based approaches have considerable potential and application particularly in terms of supporting disciplinary reflexivity and research criticality. The paper outlines some of the ways that discourse analysis, and especially Critical Discourse Analysis, could be developed and applied in marketing and consumer research. The authors provide a critical review of the development of discourse and text based studies in marketing and consumer research, and show how this has shaped, framed and limited the application and utilization of discourse analysis in particular ways. The paper offers an up to date critical reflection on the development of discourse based approaches, promoting reflexivity whilst providing empirical pathways to mainstream and critical research.

Q2. What future works have the authors mentioned in the paper "Exploring the role of discourse in marketing and consumer research" ?

This is probably one of the most exciting and transformative aspects of CDA for marketing because it opens up the possibility of examining marketing ideology and discourse through analysis of everyday, common-place activities and processes. Dobscha, S. and Ozanne, J. L. ( 2001 ), “ An ecofeminist analysis of environmentally friendly women using qualitative methodology: the emancipatory potential of an ecological life, ” Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 20 ( 2 ), pp. 201-214.

Q3. What is the purpose of this paper?

Their intention in this paper is to advance the use of discourse analysis both as a critical mirror and methodological lens for marketing and consumer researchers.

Q4. What is the significance of discourse analysis?

The pioneering research on discourse and textual analysis became foundational to amore general cultural turn in consumer research throughout the 2000s.

Q5. What are the disciplines of marketing and consumer behaviour?

Beyond marketing practice, the disciplines of marketing and consumer behaviour arealso naturalising and thus potentially subverting discourses.

Q6. What is the significance of Scott’s support for reader-response?

Scott’s (1994b) support for reader-response has particular resonance because it calls back to an underlying preference in consumer and marketing research to afford some kind of priority or sovereignty to the agent-consumer (or reader).

Q7. What is the main impediment to the uptake of discourse analysis?

An additional impediment to the uptake of discourse analysis, though not unique to marketing, is the commonly held belief in very limited views of language itself:“Language is not only content; it is also context and a way to recontextualize content.

Q8. What is the key aspect of CDA?

A key aspect of CDA is the idea that discourses emerge from micro-level practices, orto put it another way, they are a ‘bottom up’ phenomenon that derive from everyday conditions and practices.

Q9. What is the main reason why the literature is underrepresented in marketing and consumer research?

This 4 underrepresentation is manifest in part through resistance to the ontological view that marketing is socially constructed (Berger and Luckmann, 1971; Hackley, 2001) and in part in scepticism over language as a viable unit of analysis (Boje et al., 2004).

Q10. What is the main purpose of the critical marketing movement?

From a Critical Management Studies perspective however, marketing is generally considered as a relatively marginal ‘specialism’ of management somewhat subordinate to the ‘core’ organizational theory, behaviour and culture (Alvesson 2011).

Q11. What is the main point of departure?

The main point of departure here is that marketing is generally acknowledged as a culturally or socially constructed unit of analysis (Burton 2001; Hackley 2001).

Q12. What is the real value of discourse analysis?

Though rather than wielding the ‘critical stick’ at marketing, the real value of such discourse-based approaches is that they provide a methodological tool with which to firmly anchor critical research questions about the nature and implications of marketing realities, so that they may be positively transformed (Fairclough, 1992, 1995).

Q13. What was the need for ad-based analysis?

Only relatively minor adaptations or redefinition of the ad as text, the consumer/receiver as reader, and the agency as author/producer, was needed in order to introduce literary and text-based analysis.

Q14. What does the term ‘discourse analysis’ mean?

Discourse analysis does not imply a deterministic or structuralist view of the world, that somehow the ‘discourse of the market’ causes people, institutions and organisations to conform and behave in certain kinds of ways.

Ask Copilot

Related papers

Contributing institutions

Related topics

What (Exactly) Is Discourse Analysis? A Plain-Language Explanation & Definition (With Examples)

By: Jenna Crosley (PhD). Expert Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2021

Discourse analysis is one of the most popular qualitative analysis techniques we encounter at Grad Coach. If you’ve landed on this post, you’re probably interested in discourse analysis, but you’re not sure whether it’s the right fit for your project, or you don’t know where to start. If so, you’ve come to the right place.

Overview: Discourse Analysis Basics

In this post, we’ll explain in plain, straightforward language :

- What discourse analysis is

- When to use discourse analysis

- The main approaches to discourse analysis

- How to conduct discourse analysis

What is discourse analysis?

Let’s start with the word “discourse”.

In its simplest form, discourse is verbal or written communication between people that goes beyond a single sentence . Importantly, discourse is more than just language. The term “language” can include all forms of linguistic and symbolic units (even things such as road signs), and language studies can focus on the individual meanings of words. Discourse goes beyond this and looks at the overall meanings conveyed by language in context . “Context” here refers to the social, cultural, political, and historical background of the discourse, and it is important to take this into account to understand underlying meanings expressed through language.

A popular way of viewing discourse is as language used in specific social contexts, and as such language serves as a means of prompting some form of social change or meeting some form of goal.

Now that we’ve defined discourse, let’s look at discourse analysis .

Discourse analysis uses the language presented in a corpus or body of data to draw meaning . This body of data could include a set of interviews or focus group discussion transcripts. While some forms of discourse analysis center in on the specifics of language (such as sounds or grammar), other forms focus on how this language is used to achieve its aims. We’ll dig deeper into these two above-mentioned approaches later.

As Wodak and Krzyżanowski (2008) put it: “discourse analysis provides a general framework to problem-oriented social research”. Basically, discourse analysis is used to conduct research on the use of language in context in a wide variety of social problems (i.e., issues in society that affect individuals negatively).

For example, discourse analysis could be used to assess how language is used to express differing viewpoints on financial inequality and would look at how the topic should or shouldn’t be addressed or resolved, and whether this so-called inequality is perceived as such by participants.

What makes discourse analysis unique is that it posits that social reality is socially constructed , or that our experience of the world is understood from a subjective standpoint. Discourse analysis goes beyond the literal meaning of words and languages

For example, people in countries that make use of a lot of censorship will likely have their knowledge, and thus views, limited by this, and will thus have a different subjective reality to those within countries with more lax laws on censorship.

When should you use discourse analysis?

There are many ways to analyze qualitative data (such as content analysis , narrative analysis , and thematic analysis ), so why should you choose discourse analysis? Well, as with all analysis methods, the nature of your research aims, objectives and research questions (i.e. the purpose of your research) will heavily influence the right choice of analysis method.

The purpose of discourse analysis is to investigate the functions of language (i.e., what language is used for) and how meaning is constructed in different contexts, which, to recap, include the social, cultural, political, and historical backgrounds of the discourse.

For example, if you were to study a politician’s speeches, you would need to situate these speeches in their context, which would involve looking at the politician’s background and views, the reasons for presenting the speech, the history or context of the audience, and the country’s social and political history (just to name a few – there are always multiple contextual factors).

Discourse analysis can also tell you a lot about power and power imbalances , including how this is developed and maintained, how this plays out in real life (for example, inequalities because of this power), and how language can be used to maintain it. For example, you could look at the way that someone with more power (for example, a CEO) speaks to someone with less power (for example, a lower-level employee).

Therefore, you may consider discourse analysis if you are researching:

- Some form of power or inequality (for example, how affluent individuals interact with those who are less wealthy

- How people communicate in a specific context (such as in a social situation with colleagues versus a board meeting)

- Ideology and how ideas (such as values and beliefs) are shared using language (like in political speeches)

- How communication is used to achieve social goals (such as maintaining a friendship or navigating conflict)

As you can see, discourse analysis can be a powerful tool for assessing social issues , as well as power and power imbalances . So, if your research aims and objectives are oriented around these types of issues, discourse analysis could be a good fit for you.

Discourse Analysis: The main approaches

There are two main approaches to discourse analysis. These are the language-in-use (also referred to as socially situated text and talk ) approaches and the socio-political approaches (most commonly Critical Discourse Analysis ). Let’s take a look at each of these.

Approach #1: Language-in-use

Language-in-use approaches focus on the finer details of language used within discourse, such as sentence structures (grammar) and phonology (sounds). This approach is very descriptive and is seldom seen outside of studies focusing on literature and/or linguistics.

Because of its formalist roots, language-in-use pays attention to different rules of communication, such as grammaticality (i.e., when something “sounds okay” to a native speaker of a language). Analyzing discourse through a language-in-use framework involves identifying key technicalities of language used in discourse and investigating how the features are used within a particular social context.

For example, English makes use of affixes (for example, “un” in “unbelievable”) and suffixes (“able” in “unbelievable”) but doesn’t typically make use of infixes (units that can be placed within other words to alter their meaning). However, an English speaker may say something along the lines of, “that’s un-flipping-believable”. From a language-in-use perspective, the infix “flipping” could be investigated by assessing how rare the phenomenon is in English, and then answering questions such as, “What role does the infix play?” or “What is the goal of using such an infix?”

Need a helping hand?

Approach #2: Socio-political

Socio-political approaches to discourse analysis look beyond the technicalities of language and instead focus on the influence that language has in social context , and vice versa. One of the main socio-political approaches is Critical Discourse Analysis , which focuses on power structures (for example, the power dynamic between a teacher and a student) and how discourse is influenced by society and culture. Critical Discourse Analysis is born out of Michel Foucault’s early work on power, which focuses on power structures through the analysis of normalized power .

Normalized power is ingrained and relatively allusive. It’s what makes us exist within society (and within the underlying norms of society, as accepted in a specific social context) and do the things that we need to do. Contrasted to this, a more obvious form of power is repressive power , which is power that is actively asserted.

Sounds a bit fluffy? Let’s look at an example.

Consider a situation where a teacher threatens a student with detention if they don’t stop speaking in class. This would be an example of repressive power (i.e. it was actively asserted).

Normalized power, on the other hand, is what makes us not want to talk in class . It’s the subtle clues we’re given from our environment that tell us how to behave, and this form of power is so normal to us that we don’t even realize that our beliefs, desires, and decisions are being shaped by it.

In the view of Critical Discourse Analysis, language is power and, if we want to understand power dynamics and structures in society, we must look to language for answers. In other words, analyzing the use of language can help us understand the social context, especially the power dynamics.

While the above-mentioned approaches are the two most popular approaches to discourse analysis, other forms of analysis exist. For example, ethnography-based discourse analysis and multimodal analysis. Ethnography-based discourse analysis aims to gain an insider understanding of culture , customs, and habits through participant observation (i.e. directly observing participants, rather than focusing on pre-existing texts).

On the other hand, multimodal analysis focuses on a variety of texts that are both verbal and nonverbal (such as a combination of political speeches and written press releases). So, if you’re considering using discourse analysis, familiarize yourself with the various approaches available so that you can make a well-informed decision.

How to “do” discourse analysis

As every study is different, it’s challenging to outline exactly what steps need to be taken to complete your research. However, the following steps can be used as a guideline if you choose to adopt discourse analysis for your research.

Step 1: Decide on your discourse analysis approach

The first step of the process is to decide on which approach you will take in terms. For example, the language in use approach or a socio-political approach such as critical discourse analysis. To do this, you need to consider your research aims, objectives and research questions . Of course, this means that you need to have these components clearly defined. If you’re still a bit uncertain about these, check out our video post covering topic development here.

While discourse analysis can be exploratory (as in, used to find out about a topic that hasn’t really been touched on yet), it is still vital to have a set of clearly defined research questions to guide your analysis. Without these, you may find that you lack direction when you get to your analysis. Since discourse analysis places such a focus on context, it is also vital that your research questions are linked to studying language within context.

Based on your research aims, objectives and research questions, you need to assess which discourse analysis would best suit your needs. Importantly, you need to adopt an approach that aligns with your study’s purpose . So, think carefully about what you are investigating and what you want to achieve, and then consider the various options available within discourse analysis.

It’s vital to determine your discourse analysis approach from the get-go , so that you don’t waste time randomly analyzing your data without any specific plan.

Step 2: Design your collection method and gather your data

Once you’ve got determined your overarching approach, you can start looking at how to collect your data. Data in discourse analysis is drawn from different forms of “talk” and “text” , which means that it can consist of interviews , ethnographies, discussions, case studies, blog posts.

The type of data you collect will largely depend on your research questions (and broader research aims and objectives). So, when you’re gathering your data, make sure that you keep in mind the “what”, “who” and “why” of your study, so that you don’t end up with a corpus full of irrelevant data. Discourse analysis can be very time-consuming, so you want to ensure that you’re not wasting time on information that doesn’t directly pertain to your research questions.

When considering potential collection methods, you should also consider the practicalities . What type of data can you access in reality? How many participants do you have access to and how much time do you have available to collect data and make sense of it? These are important factors, as you’ll run into problems if your chosen methods are impractical in light of your constraints.

Once you’ve determined your data collection method, you can get to work with the collection.

Step 3: Investigate the context

A key part of discourse analysis is context and understanding meaning in context. For this reason, it is vital that you thoroughly and systematically investigate the context of your discourse. Make sure that you can answer (at least the majority) of the following questions:

- What is the discourse?

- Why does the discourse exist? What is the purpose and what are the aims of the discourse?

- When did the discourse take place?

- Where did it happen?

- Who participated in the discourse? Who created it and who consumed it?

- What does the discourse say about society in general?

- How is meaning being conveyed in the context of the discourse?

Make sure that you include all aspects of the discourse context in your analysis to eliminate any confounding factors. For example, are there any social, political, or historical reasons as to why the discourse would exist as it does? What other factors could contribute to the existence of the discourse? Discourse can be influenced by many factors, so it is vital that you take as many of them into account as possible.

Once you’ve investigated the context of your data, you’ll have a much better idea of what you’re working with, and you’ll be far more familiar with your content. It’s then time to begin your analysis.

Step 4: Analyze your data

When performing a discourse analysis, you’ll need to look for themes and patterns . To do this, you’ll start by looking at codes , which are specific topics within your data. You can find more information about the qualitative data coding process here.

Next, you’ll take these codes and identify themes. Themes are patterns of language (such as specific words or sentences) that pop up repeatedly in your data, and that can tell you something about the discourse. For example, if you’re wanting to know about women’s perspectives of living in a certain area, potential themes may be “safety” or “convenience”.

In discourse analysis, it is important to reach what is called data saturation . This refers to when you’ve investigated your topic and analyzed your data to the point where no new information can be found. To achieve this, you need to work your way through your data set multiple times, developing greater depth and insight each time. This can be quite time consuming and even a bit boring at times, but it’s essential.

Once you’ve reached the point of saturation, you should have an almost-complete analysis and you’re ready to move onto the next step – final review.

Step 5: Review your work

Hey, you’re nearly there. Good job! Now it’s time to review your work.

This final step requires you to return to your research questions and compile your answers to them, based on the analysis. Make sure that you can answer your research questions thoroughly, and also substantiate your responses with evidence from your data.

Usually, discourse analysis studies make use of appendices, which are referenced within your thesis or dissertation. This makes it easier for reviewers or markers to jump between your analysis (and findings) and your corpus (your evidence) so that it’s easier for them to assess your work.

When answering your research questions, make you should also revisit your research aims and objectives , and assess your answers against these. This process will help you zoom out a little and give you a bigger picture view. With your newfound insights from the analysis, you may find, for example, that it makes sense to expand the research question set a little to achieve a more comprehensive view of the topic.

Let’s recap…

In this article, we’ve covered quite a bit of ground. The key takeaways are:

- Discourse analysis is a qualitative analysis method used to draw meaning from language in context.

- You should consider using discourse analysis when you wish to analyze the functions and underlying meanings of language in context.

- The two overarching approaches to discourse analysis are language-in-use and socio-political approaches .

- The main steps involved in undertaking discourse analysis are deciding on your analysis approach (based on your research questions), choosing a data collection method, collecting your data, investigating the context of your data, analyzing your data, and reviewing your work.

If you have any questions about discourse analysis, feel free to leave a comment below. If you’d like 1-on-1 help with your analysis, book an initial consultation with a friendly Grad Coach to see how we can help.

Psst… there’s more (for free)

This post is part of our dissertation mini-course, which covers everything you need to get started with your dissertation, thesis or research project.

You Might Also Like:

30 Comments

This was really helpful to me

I would like to know the importance of discourse analysis analysis to academic writing

In academic writing coherence and cohesion are very important. DA will assist us to decide cohesiveness of the continuum of discourse that are used in it. We can judge it well.

Thank you so much for this piece, can you please direct how I can use Discourse Analysis to investigate politics of ethnicity in a particular society

Fantastically helpful! Could you write on how discourse analysis can be done using computer aided technique? Many thanks

I would like to know if I can use discourse analysis to research on electoral integrity deviation and when election are considered free & fair

I also to know the importance of discourse analysis and it’s purpose and characteristics

Thanks, we are doing discourse analysis as a subject this year and this helped a lot!

Please can you help explain and answer this question? With illustrations,Hymes’ Acronym SPEAKING, as a feature of Discourse Analysis.

What are the three objectives of discourse analysis especially on the topic how people communicate between doctor and patient

Very useful Thank you for your work and information

thank you so much , I wanna know more about discourse analysis tools , such as , latent analysis , active powers analysis, proof paths analysis, image analysis, rhetorical analysis, propositions analysis, and so on, I wish I can get references about it , thanks in advance

Its beyond my expectations. It made me clear everything which I was struggling since last 4 months. 👏 👏 👏 👏

Thank you so much … It is clear and helpful

Thanks for sharing this material. My question is related to the online newspaper articles on COVID -19 pandemic the way this new normal is constructed as a social reality. How discourse analysis is an appropriate approach to examine theese articles?

This very helpful and interesting information

This was incredible! And massively helpful.

I’m seeking further assistance if you don’t mind.

Found it worth consuming!

What are the four types of discourse analysis?

very helpful. And I’d like to know more about Ethnography-based discourse analysis as I’m studying arts and humanities, I’d like to know how can I use it in my study.

Amazing info. Very happy to read this helpful piece of documentation. Thank you.

is discourse analysis can take data from medias like TV, Radio…?

I need to know what is general discourse analysis

Direct to the point, simple and deep explanation. this is helpful indeed.

Thank you so much was really helpful

really impressive

Thank you very much, for the clear explanations and examples.

It is really awesome. Anybody within just in 5 minutes understand this critical topic so easily. Thank you so much.

Thank you for enriching my knowledge on Discourse Analysis . Very helpful thanks again

This was extremely helpful. I feel less anxious now. Thank you so much.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Discourse analysis, trust and marketing

Cite this chapter.

- Sue Halliday &

- Maurizio Catulli

Part of the book series: Palgrave Studies in Professional and Organizational Discourse ((PSPOD))

850 Accesses

In order to understand the service encounter, which lies at the heart of all marketing processes, it is necessary to focus on consumer and consumercontact personnel interactions. We view the marketing encounter between the consumer and organisation personnel as a narrative event. Since social life is a narrative (MacIntyre 1981), what we are saying is that marketing processes are part of the narrative of our social lives. We understand narrative as a discursive ‘form of meaning making’ (Polkinghorne 1988, p. 36). We use Potter and Wetherell’s approach to discourse analysis (1987) to focus less on an objective outcome constructed in the marketing encounter (the transaction, the purchase) and more on the variations and consistencies in language use, to discern what collective, interpersonal meaning is being constructed in the encounter. In other words, we look at what people say and consider how this then creates the marketing encounter. In this chapter we explore this encounter and examine discursive processes for capitalising on and building trust in marketing encounters.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Alvesson, M. & Skoldberg, K. (2000) Reflexive Methodology: New vistas for qualitative research . London: Sage.

Google Scholar

AMA [American Marketing Association] (2007) [typesetter run on if possible] http://www.marketingpower.com/Communiry/ARC/Pages/Additional/Definition/de fault.aspx

Ashby, S. & Diacon, S. (2000) Strategic rivalry and crisis management. Risk Management, 2(2): 7–15.

Article Google Scholar

Badot, O. & Cova, B. (2008) The myopia of new marketing panaceas: the case for rebuilding our discipline. Journal of Marketing Management , 24(1–2): 205–19.

Bakhtin, M. & Medvedev P. N. (1928/85) The Formal Method in Literary Scholarship: A critical introduction to sociological poetics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Berger, P. & Luckmann, T. (1967) The Social Construction of Reality . Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Bitner, M. J., Booms, B. H. & Mohr, L. A. (1994) Critical service encounters: the employee’s viewpoint. Journal of Marketing , 58 : 95–106.

Boje, D. M. (1995) Stories of the story telling organization: a postmodern analysis of Disney as ‘Tamara-land'. Academy of Management Journal , 38(4): 997–1036.

Brown, A. D. (1998) Narrative, politics and legitimacy in an IT implementation. Journal of Management Studies , 35(1): 35–58.

Bruner, J. (1986) Actual Minds, Possible Worlds . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. (1990) Acts of Meaning . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Coffey, A. & Atkinson, P. (1996) Making Sense of Qualitative Data . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Cowles, D. L. (1996) The role of trust in customer relationships: asking the right questions. Management Decision , 34(4): 273–82.

Czarniawska, B. (1997) Narrating the Organization . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Housley, W. & Fitzgerald, R. (2002) The reconsidered model of membership categorization analysis. Qualitative Research , 2(1): 59–83.

Gee, J. P. (1999) An Introduction to Discourse Analysis, Theory and Method . London: Routledge.

Girden, E. R. (2001) Evaluating Research Articles . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Grönroos, C. (2009) Marketing as promise management: regaining customer management for marketing. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing , 24(5/6): 351–9.

Gummesson, E. (1987) The new marketing developing long-term interactive relationships. Long Range Planning , 20(4) : 10–20.

Gummesson, E. (1999) Total Relationship Marketing , 2nd edition. Oxford: ButterworthHeinemann.

Gurviez, P. (1997) Trust, a new approach to understanding the brand-consumer relationship. Proceedings of the AMA Special Conference in Relationship Marketing , pp. 505–18. Dublin University, Dublin, June.

Halliday S. V. (2004) How ‘placed trust’ works in a service encounter. Journal of Services Marketing , 18(1) : 45–59.

Halliday S. V. & Cawley, R. (2000) Re-negotiating and re-affirming in cross-border marketing relationships: a learning-based conceptual model and research propositions. Management Decision , 38(8): 584–95.

Han, S.-L., Wilson, D. T. & Dant, S. P. (1993) Buyer-supplier relationships today. Industrial Marketing Management , (22): 331–8.

Hosmer, L. T. (1995) Trust: the connecting link between organizational theory and philosophical ethics. Academy of Management Review , 20(2) : 379–403.

Maclntyre, A. (1981) After Virtue . London: Duckworth.

Marshall, H. (1994) Discourse analysis in an occupational context. In C. Cassell & G. Symon (eds.), Qualitative Methods in Organisational Research: A practical guide (pp. 91–106). London: Sage.

McNeill, P. (1985) Research Methods . London: Tavistock.

Morgan, R. A. & Hunt, S. D. (1994) The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing , 58 : 20–38.

Packard, V. (1957) Hidden Persuaders . Philadelphia: D. McKay Co.

Palmer, A. (1994) Relationship marketing: back to basics? Journal of Marketing Management , 10 : 571–9.

Phillips, N. & Hardy, C. (2002) Discourse Analysis : Investigating processes of social construction . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Book Google Scholar

Polkinghorne, D. E. (1988) Narrative Knowing and the Human Sciences . New York: State University of New York Press.

Potter, J. & Wetherell, M. (1987) Discourse in Social Psychology . London: Sage Publications.

Riessman, C. K. (1993) Narrative Analysis . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Sacks, H. (1992) Lectures on Conversation, Vol. II , Oxford: Blackwell.

Sayer, A. (1992) Method in Social Science: A realist approach . London: Routledge

Trevarthen, C. (1979) Instincts for human understanding and for cultural cooperation: their development in infancy. In M. von Cranach et al . (eds.), Human Ethology: Claims and limits of a new discipline . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Weick K. E. (1995) Sense Making in Organizations . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Williamson, O. E. (1993) Calculativeness, tmst and economic organization. Journal of Law and Economics , 36(1): 453–86.

Download references

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Linguistics, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia

Christopher N. Candlin ( Senior Research Professor Emeritus ) ( Senior Research Professor Emeritus )

Research Centre for Languages and Cultures, University of South Australia, Australia

Jonathan Crichton ( Lecturer in Applied Linguistics and Research Fellow ) ( Lecturer in Applied Linguistics and Research Fellow )

Copyright information

© 2013 Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited

About this chapter

Halliday, S., Catulli, M. (2013). Discourse analysis, trust and marketing. In: Candlin, C.N., Crichton, J. (eds) Discourses of Trust. Palgrave Studies in Professional and Organizational Discourse. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-29556-9_19

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-29556-9_19

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN : 978-1-349-59404-7

Online ISBN : 978-1-137-29556-9

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Join thousands of product people at Insight Out Conf on April 11. Register free.

Insights hub solutions

Analyze data

Uncover deep customer insights with fast, powerful features, store insights, curate and manage insights in one searchable platform, scale research, unlock the potential of customer insights at enterprise scale.

Featured reads

Inspiration

Three things to look forward to at Insight Out

Tips and tricks

Make magic with your customer data in Dovetail

Four ways Dovetail helps Product Managers master continuous product discovery

Events and videos

© Dovetail Research Pty. Ltd.

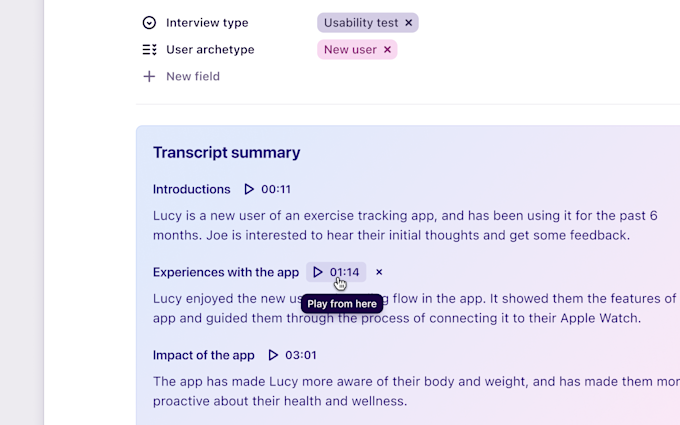

Exploring discourse analysis for making meaningful decisions

Last updated

20 March 2023

Reviewed by

Miroslav Damyanov

Discourse analysis is an interdisciplinary field that studies how conversations are structured and used to create meaning. It examines how language is used in written texts, spoken conversations, and digital media conversations.

The method can be used to identify how participants in a conversation influence it and how their words and phrases shape it.

From everyday conversation to political speeches and media representations, discourse analysis can shed light on how language shapes the world.

You can learn the basics of this wide-ranging field in this article.

Make research less tedious

Dovetail streamlines research to help you uncover and share actionable insights

- What is discourse analysis?

This interdisciplinary method relies on the systematic analysis of spoken or written communications, focusing on how language is used to form meaning, convey social identity, and reinforce power relations.

The method is used in several different contexts, ranging from everyday conversations to political speeches and representations in the media.

- What is discourse analysis used for?

Discourse analysis is used whenever researchers want to gain a deeper understanding of the social and cultural contexts that drive language use in a given area.

Some common uses for discourse analysis include the following:

Understanding how language use reflects and reinforces social and cultural norms

Examining how power relations are constructed and maintained through language

Identifying patterns and trends in language use over time and across different contexts

Analyzing how social identities are constructed through language

Investigating how language is used to persuade or influence others

Informing the development of language teaching and learning materials

Supporting policy and decision-making in areas such as media, politics, and education

Understanding how political actors use language to persuade, influence, and mobilize support

Studying how language in media representations constructs social reality and shapes public opinion

Analyzing how legal language is used to construct legal concepts and reinforce power relations

Examining how everyday language is used to negotiate social relationships

- The main approaches to discourse analysis

As an interdisciplinary field, discourse analysis can be approached from radically different perspectives depending on who is performing the analysis and the field they are in.

The broad fields where this method is used are discussed below.

In sociology, discourse analysis is used to study how language is used to construct social reality.

It enables sociologists to examine how language is used to create and maintain social structures, impact social identity, and affect changes to the social order.

One of the key ideas in sociology is that social reality is constructed through the way society uses language. Sociologists believe that language evolves as a reflection of a culture’s existing values and the power hierarchies that have resulted from those values. They argue that the use of language can reinforce those values and structures.

Sociolinguistics

As the study of the relationship between language and society, sociolinguistics can benefit greatly from discourse analysis.

The method allows sociolinguists to examine how language is used in specific social contexts, ranging from conversations the average person has with their neighbor to the speeches a politician broadcasts to millions of listeners.

Sociolinguists believe a variety of social factors inform the language we choose to use.

Philosophers employ discourse analysis to study how language is used to construct meaning and convey philosophical concepts. It is used in this field to examine how language constructs truth, knowledge, meaning, and social and cultural reality.

Linguistics

Linguists can use discourse analysis to examine how a language’s structure evolves over time and how social and cultural factors impact languages. When linguists understand how these social factors change language, they can draw more informed conclusions.

Artificial intelligence

Natural language processing systems are designed by programmers to help computers understand human language. Discourse analysis is used to study the structure and meaning of language in order to develop algorithms that can analyze and interpret language use. It can also help in the development of chatbots, virtual assistants, and other conversational interfaces.

- Steps to conduct discourse analysis

The steps involved in discourse analysis can vary depending on the specific approach and methodology used. Outlined below is a general guide to the process.

1. Define the research question

The first step is to clearly define what you’ll be researching. Identify the key concepts, themes, or issues you’ll explore as you conduct the analysis.

2. Select a data sample

Next, you need to gather the data sample you’ll be using for the research. This could include written or spoken texts.

Depending on the subject being studied, you may gather interviews, speeches, news articles, social media posts, or other relevant forms of communication.

3. Collect and transcribe the data

Spoken data should be transcribed into written form as accurately as possible. This includes both verbal and non-verbal cues.

If you have collected text data, you can skip this step.

4. Analyze the data

Now it’s time to analyze the data to look for patterns or themes that emerge in the way language is used.

The patterns you look for will depend on the subject you’re performing analysis for. Take careful notes of what you notice for further analysis in the next step.

5. Identify themes and categories

With the data analyzed and patterns notated, it’s time to begin looking for common themes among those patterns. These might be specific linguistic features like word choice, metaphor use, or speaking register. They may also be based on broader themes or topics.

6. Interpret the data

Once you have identified themes and categories, you can begin to interpret the data to develop insights and conclusions about the communication being analyzed. This involves reflecting on the data in relation to the research question, drawing connections between the identified items and your research question, and developing a coherent and nuanced interpretation of the data.

7. Write up your findings

Finally, you can write up your findings, drawing on your analysis and interpretation of the data. Your write-up should clearly present your research question , the methods and data used, the themes and categories identified, and your interpretation of the data.

You should also discuss your findings’ implications and any limitations or challenges you encountered during the process.

- Advantages and disadvantages of discourse analysis

Now you understand what discourse analysis is and the basics of how to perform it, you can start evaluating whether or not it’s the right choice for achieving your research goals.

Below is a list of the advantages and disadvantages of using discourse analysis:

Provides a deeper understanding of communication —the method can help identify factors that influence communication, such as power dynamics, social norms, and cultural values.

Provides insights into social issues —by analyzing communication patterns, researchers can gain insights into social issues such as inequality, discrimination, and exclusion.

Uncovers implicit meaning —researchers can reveal hidden meanings and messages in communication.

Reveals changes over time —researchers can gain insights into how the public views and relates to social issues over time by analyzing historical data.

Informs policy and practice —by revealing the underlying social structures and power relations that shape communication, researchers can identify areas for intervention and develop strategies to address social issues.

Disadvantages

Time-consuming —the process of collecting the large amount of data needed for discourse analysis and then transcribing, analyzing, and interpreting it can be time-intensive.

Highly subjective —different researchers may interpret the same data differently, leading to potential disagreements about findings.

Requires advanced training —researchers need to be familiar with the specific methodological approaches and techniques used in discourse analysis

Limited by data availability —conducting a thorough analysis can be challenging if data related to the subject being studied is limited or unavailable.

Doesn’t generalize well —discourse analysis tends to focus on specific instances of communication and may not produce findings that can be generalized to broader populations or contexts.

Discourse analysis is a powerful and versatile research method that can help researchers study how language use reflects and reinforces social structures and identities.

By using the method, researchers can examine the linguistic features of different types of discourse across social contexts. Through that analysis, they can gain insights into how language use is shaped by complex social factors.

Get started today

Go from raw data to valuable insights with a flexible research platform

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 21 December 2023

Last updated: 16 December 2023

Last updated: 17 February 2024

Last updated: 19 November 2023

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 15 February 2024

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 10 April 2023

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

- Open access

- Published: 03 February 2016

A multimodal discourse analysis of the textual and logical relations in marketing texts written by international undergraduate students

- Hesham Suleiman Alyousef ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9280-9282 1

Functional Linguistics volume 3 , Article number: 3 ( 2016 ) Cite this article

23k Accesses

5 Citations

Metrics details