Paris, 1951. Photo by Elliot Erwitt/Magnum

Loved, yet lonely

You might have the unconditional love of family and friends and yet feel deep loneliness. can philosophy explain why.

by Kaitlyn Creasy + BIO

Although one of the loneliest moments of my life happened more than 15 years ago, I still remember its uniquely painful sting. I had just arrived back home from a study abroad semester in Italy. During my stay in Florence, my Italian had advanced to the point where I was dreaming in the language. I had also developed intellectual interests in Italian futurism, Dada, and Russian absurdism – interests not entirely deriving from a crush on the professor who taught a course on those topics – as well as the love sonnets of Dante and Petrarch (conceivably also related to that crush). I left my semester abroad feeling as many students likely do: transformed not only intellectually but emotionally. My picture of the world was complicated, my very experience of that world richer, more nuanced.

After that semester, I returned home to a small working-class town in New Jersey. Home proper was my boyfriend’s parents’ home, which was in the process of foreclosure but not yet taken by the bank. Both parents had left to live elsewhere, and they graciously allowed me to stay there with my boyfriend, his sister and her boyfriend during college breaks. While on break from school, I spent most of my time with these de facto roommates and a handful of my dearest childhood friends.

When I returned from Italy, there was so much I wanted to share with them. I wanted to talk to my boyfriend about how aesthetically interesting but intellectually dull I found Italian futurism; I wanted to communicate to my closest friends how deeply those Italian love sonnets moved me, how Bob Dylan so wonderfully captured their power. (‘And every one of them words rang true/and glowed like burning coal/Pouring off of every page/like it was written in my soul …’) In addition to a strongly felt need to share specific parts of my intellectual and emotional lives that had become so central to my self-understanding, I also experienced a dramatically increased need to engage intellectually, as well as an acute need for my emotional life in all its depth and richness – for my whole being, this new being – to be appreciated. When I returned home, I felt not only unable to engage with others in ways that met my newly developed needs, but also unrecognised for who I had become since I left. And I felt deeply, painfully lonely.

This experience is not uncommon for study-abroad students. Even when one has a caring and supportive network of relationships, one will often experience ‘reverse culture shock’ – what the psychologist Kevin Gaw describes as a ‘process of readjusting, reacculturating, and reassimilating into one’s own home culture after living in a different culture for a significant period of time’ – and feelings of loneliness are characteristic for individuals in the throes of this process.

But there are many other familiar life experiences that provoke feelings of loneliness, even if the individuals undergoing those experiences have loving friends and family: the student who comes home to his family and friends after a transformative first year at college; the adolescent who returns home to her loving but repressed parents after a sexual awakening at summer camp; the first-generation woman of colour in graduate school who feels cared for but also perpetually ‘ in-between ’ worlds, misunderstood and not fully seen either by her department members or her family and friends back home; the travel nurse who returns home to her partner and friends after an especially meaningful (or perhaps especially psychologically taxing) work assignment; the man who goes through a difficult breakup with a long-term, live-in partner; the woman who is the first in her group of friends to become a parent; the list goes on.

Nor does it take a transformative life event to provoke feelings of loneliness. As time passes, it often happens that friends and family who used to understand us quite well eventually fail to understand us as they once did, failing to really see us as they used to before. This, too, will tend to lead to feelings of loneliness – though the loneliness may creep in more gradually, more surreptitiously. Loneliness, it seems, is an existential hazard, something to which human beings are always vulnerable – and not just when they are alone.

In his recent book Life Is Hard (2022), the philosopher Kieran Setiya characterises loneliness as the ‘pain of social disconnection’. There, he argues for the importance of attending to the nature of loneliness – both why it hurts and what ‘that pain tell[s] us about how to live’ – especially given the contemporary prevalence of loneliness. He rightly notes that loneliness is not just a matter of being isolated from others entirely, since one can be lonely even in a room full of people. Additionally, he notes that, since the negative psychological and physiological effects of loneliness ‘seem to depend on the subjective experience of being lonely’, effectively combatting loneliness requires us to identify the origin of this subjective experience.

S etiya’s proposal is that we are ‘social animals with social needs’ that crucially include needs to be loved and to have our basic worth recognised. When we fail to have these basic needs met, as we do when we are apart from our friends, we suffer loneliness. Without the presence of friends to assure us that we matter, we experience the painful ‘sensation of hollowness, of a hole in oneself that used to be filled and now is not’. This is loneliness in its most elemental form. (Setiya uses the term ‘friends’ broadly, to include close family and romantic partners, and I follow his usage here.)

Imagine a woman who lands a job requiring a long-distance move to an area where she knows no one. Even if there are plenty of new neighbours and colleagues to greet her upon her arrival, Setiya’s claim is that she will tend to experience feelings of loneliness, since she does not yet have close, loving relationships with these people. In other words, she will tend to experience feelings of loneliness because she does not yet have friends whose love of her reflects back to her the basic value as a person that she has, friends who let her see that she matters. Only when she makes genuine friendships will she feel her unconditional value is acknowledged; only then will her basic social needs to be loved and recognised be met. Once she feels she truly matters to someone, in Setiya’s view, her loneliness will abate.

Setiya is not alone in connecting feelings of loneliness to a lack of basic recognition. In The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), for example, Hannah Arendt also defines loneliness as a feeling that results when one’s human dignity or unconditional worth as a person fails to be recognised and affirmed, a feeling that results when this, one of the ‘basic requirements of the human condition’, fails to be met.

These accounts get a good deal about loneliness right. But they miss something as well. On these views, loving friendships allow us to avoid loneliness because the loving friend provides a form of recognition we require as social beings. Without loving friendships, or when we are apart from our friends, we are unable to secure this recognition. So we become lonely. But notice that the feature affirmed by the friend here – my unconditional value – is radically depersonalised. The property the friend recognises and affirms in me is the same property she recognises and affirms in her other friendships. Otherwise put, the recognition that allegedly mitigates loneliness in Setiya’s view is the friend’s recognition of an impersonal, abstract feature of oneself, a quality one shares with every other human being: her unconditional worth as a human being. (The recognition given by the loving friend is that I ‘[matter] … just like everyone else.’)

Just as one can feel lonely in a room full of strangers, one can feel lonely in a room full of friends

Since my dignity or worth is disconnected from any particular feature of myself as an individual, however, my friend can recognise and affirm that worth without acknowledging or engaging my particular needs, specific values and so on. If Setiya is calling it right, then that friend can assuage my loneliness without engaging my individuality.

Or can they? Accounts that tie loneliness to a failure of basic recognition (and the alleviation of loneliness to love and acknowledgement of one’s dignity) may be right about the origin of certain forms of loneliness. But it seems to me that this is far from the whole picture, and that accounts like these fail to explain a wide variety of familiar circumstances in which loneliness arises.

When I came home from my study-abroad semester, I returned to a network of robust, loving friendships. I was surrounded daily by a steadfast group of people who persistently acknowledged and affirmed my unconditional value as a person, putting up with my obnoxious pretension (so it must have seemed) and accepting me even though I was alien in crucial ways to the friend they knew before. Yet I still suffered loneliness. In fact, while I had more close friendships than ever before – and was as close with friends and family members as I had ever been – I was lonelier than ever. And this is also true of the familiar scenarios from above: the first-year college student, the new parent, the travel nurse, and so on. All these scenarios are ripe for painful feelings of loneliness even though the individuals undergoing such experiences have a loving network of friends, family and colleagues who support them and recognise their unconditional value.

So, there must be more to loneliness than Setiya’s account (and others like it) let on. Of course, if an individual’s worth goes unrecognised, she will feel awfully lonely. But just as one can feel lonely in a room full of strangers, one can feel lonely in a room full of friends. What plagues accounts that tie loneliness to an absence of basic recognition is that they fail to do justice to loneliness as a feeling that pops up not only when one lacks sufficiently loving, affirmative relationships, but also when one perceives that the relationships she has (including and perhaps especially loving relationships) lack sufficient quality (for example, lacking depth or a desired feeling of connection). And an individual will perceive such relationships as lacking sufficient quality when her friends and family are not meeting the specific needs she has, or recognising and affirming her as the particular individual that she is.

We see this especially in the midst or aftermath of transitional and transformational life events, when greater-than-usual shifts occur. As the result of going through such experiences, we often develop new values, core needs and centrally motivating desires, losing other values, needs and desires in the process. In other words, after undergoing a particularly transformative experience, we become different people in key respects than we were before. If after such a personal transformation, our friends are unable to meet our newly developed core needs or recognise and affirm our new values and central desires – perhaps in large part because they cannot , because they do not (yet) recognise or understand who we have become – we will suffer loneliness.

This is what happened to me after Italy. By the time I got back, I had developed new core needs – as one example, the need for a certain level and kind of intellectual engagement – which were unmet when I returned home. What’s more, I did not think it particularly fair to expect my friends to meet these needs. After all, they did not possess the conceptual frameworks for discussing Russian absurdism or 13th-century Italian love sonnets; these just weren’t things they had spent time thinking about. And I didn’t blame them; expecting them to develop or care about developing such a conceptual framework seemed to me ridiculous. Even so, without a shared framework, I felt unable to meet my need for intellectual engagement and communicate to my friends the fullness of my inner life, which was overtaken by quite specific aesthetic values, values that shaped how I saw the world. As a result, I felt lonely.

I n addition to developing new needs, I understood myself as having changed in other fundamental respects. While I knew my friends loved me and affirmed my unconditional value, I did not feel upon my return home that they were able to see and affirm my individuality. I was radically changed; in fact, I felt in certain respects totally unrecognisable even to those who knew me best. After Italy, I inhabited a different, more nuanced perspective on the world; beauty, creativity and intellectual growth had become core values of mine; I had become a serious lover of poetry; I understood myself as a burgeoning philosopher. At the time, my closest friends were not able to see and affirm these parts of me, parts of me with which even relative strangers in my college courses were acquainted (though, of course, those acquaintances neither knew me nor were equipped to meet other of my needs which my friends had long met). When I returned home, I no longer felt truly seen by my friends .

One need not spend a semester abroad to experience this. For example, a nurse who initially chose her profession as a means to professional and financial stability might, after an especially meaningful experience with a patient, find herself newly and centrally motivated by a desire to make a difference in her patients’ lives. Along with the landscape of her desires, her core values may have changed: perhaps she develops a new core value of alleviating suffering whenever possible. And she may find certain features of her job – those that do not involve the alleviation of suffering, or involve the limited alleviation of suffering – not as fulfilling as they once were. In other words, she may have developed a new need for a certain form of meaningful difference-making – a need that, if not met, leaves her feeling flat and deeply dissatisfied.

Changes like these – changes to what truly moves you, to what makes you feel deeply fulfilled – are profound ones. To be changed in these respects is to be utterly changed. Even if you have loving friendships, if your friends are unable to recognise and affirm these new features of you, you may fail to feel seen, fail to feel valued as who you really are. At that point, loneliness will ensue. Interestingly – and especially troublesome for Setiya’s account – feelings of loneliness will tend to be especially salient and painful when the people unable to meet these needs are those who already love us and affirm our unconditional value.

Those with a strong need for their uniqueness to be recognised may be more disposed to loneliness

So, even with loving friends, if we perceive ourselves as unable to be seen and affirmed as the particular people we are, or if certain of our core needs go unmet, we will feel lonely. Setiya is surely right that loneliness will result in the absence of love and recognition. But it can also result from the inability – and sometimes, failure – of those with whom we have loving relationships to share or affirm our values, to endorse desires that we understand as central to our lives, and to satisfy our needs.

Another way to put it is that our social needs go far beyond the impersonal recognition of our unconditional worth as human beings. These needs can be as widespread as a need for reciprocal emotional attachment or as restricted as a need for a certain level of intellectual engagement or creative exchange. But even when the need in question is a restricted or uncommon one, if it is a deep need that requires another person to meet yet goes unmet, we will feel lonely. The fact that we suffer loneliness even when these quite specific needs are unmet shows that understanding and treating this feeling requires attending not just to whether my worth is affirmed, but to whether I am recognised and affirmed in my particularity and whether my particular, even idiosyncratic social needs are met by those around me.

What’s more, since different people have different needs, the conditions that produce loneliness will vary. Those with a strong need for their uniqueness to be recognised may be more disposed to loneliness. Others with weaker needs for recognition or reciprocal emotional attachment may experience a good deal of social isolation without feeling lonely at all. Some people might alleviate loneliness by cultivating a wide circle of not-especially-close friends, each of whom meets a different need or appreciates a different side of them. Yet others might persist in their loneliness without deep and intimate friendships in which they feel more fully seen and appreciated in their complexity, in the fullness of their being.

Yet, as ever-changing beings with friends and loved ones who are also ever-changing, we are always susceptible to loneliness and the pain of situations in which our needs are unmet. Most of us can recall a friend who once met certain of our core social needs, but who eventually – gradually, perhaps even imperceptibly – ultimately failed to do so. If such needs are not met by others in one’s life, this situation will lead one to feel profoundly, heartbreakingly lonely.

In cases like these, new relationships can offer true succour and light. For example, a lonely new parent might have childless friends who are clueless to the needs and values she develops through the hugely complicated transition to parenthood; as a result, she might cultivate relationships with other new parents or caretakers, people who share her newly developed values and better understand the joys, pains and ambivalences of having a child. To the extent that these new relationships enable her needs to be met and allow her to feel genuinely seen, they will help to alleviate her loneliness. Through seeking relationships with others who might share one’s interests or be better situated to meet one’s specific needs, then, one can attempt to face one’s loneliness head on.

But you don’t need to shed old relationships to cultivate the new. When old friends to whom we remain committed fail to meet our new needs, it’s helpful to ask how to salvage the situation, saving the relationship. In some instances, we might choose to adopt a passive strategy, acknowledging the ebb and flow of relationships and the natural lag time between the development of needs and others’ abilities to meet them. You could ‘wait it out’. But given that it is much more difficult to have your needs met if you don’t articulate them, an active strategy seems more promising. To position your friend to better meet your needs, you might attempt to communicate those needs and articulate ways in which you don’t feel seen.

Of course, such a strategy will be successful only if the unmet needs provoking one’s loneliness are needs one can identify and articulate. But we will so often – perhaps always – have needs, desires and values of which we are unaware or that we cannot articulate, even to ourselves. We are, to some extent, always opaque to ourselves. Given this opacity, some degree of loneliness may be an inevitable part of the human condition. What’s more, if we can’t even grasp or articulate the needs provoking our loneliness, then adopting a more passive strategy may be the only option one has. In cases like this, the only way to recognise your unmet needs or desires is to notice that your loneliness has started to lift once those needs and desires begin to be met by another.

Design and fashion

Sitting on the art

Given its intimacy with the body and deep play on form and function, furniture is a ripely ambiguous artform of its own

Emma Crichton Miller

Learning to be happier

In order to help improve my students’ mental health, I offered a course on the science of happiness. It worked – but why?

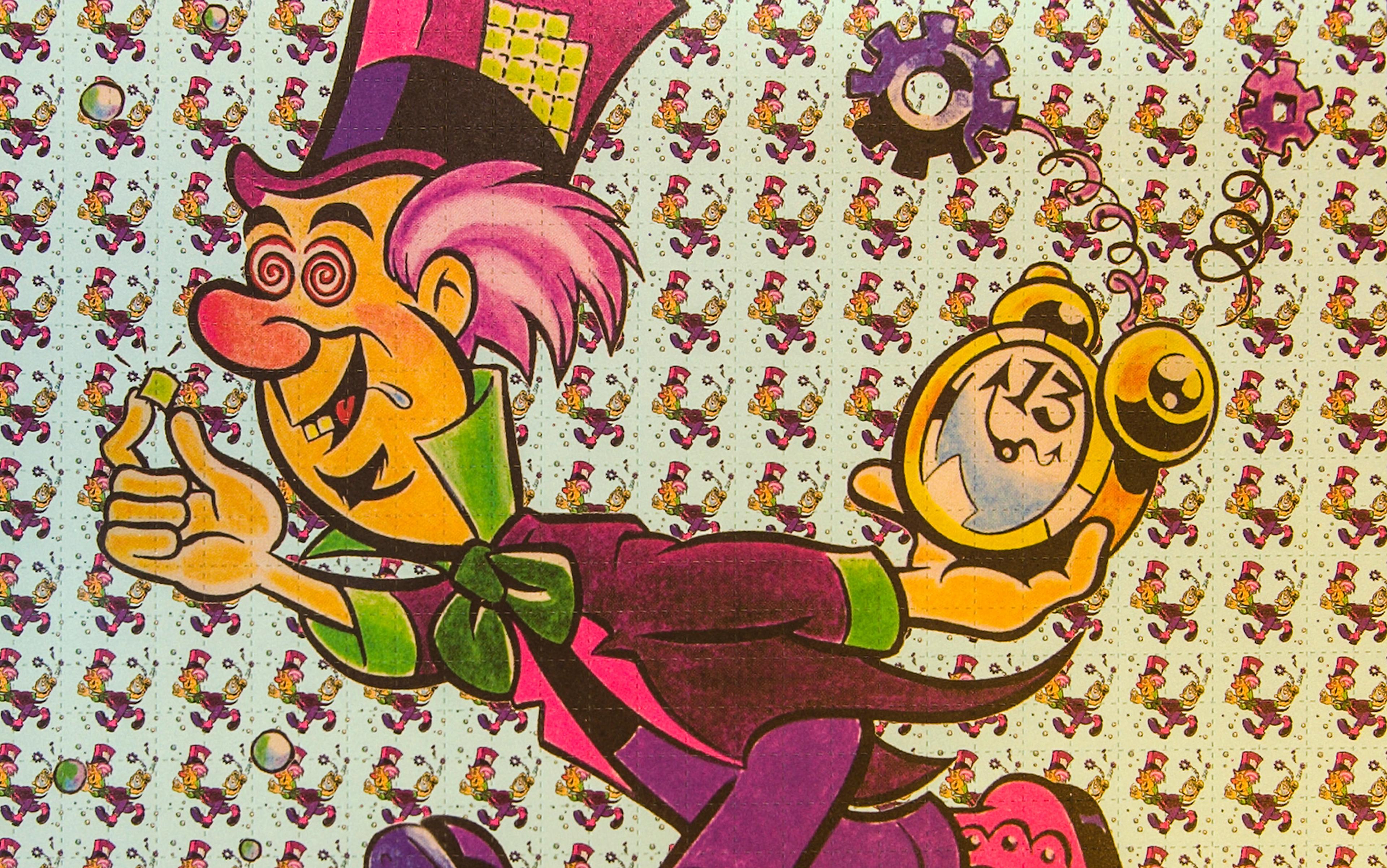

Consciousness and altered states

How perforated squares of trippy blotter paper allowed outlaw chemists and wizard-alchemists to dose the world with LSD

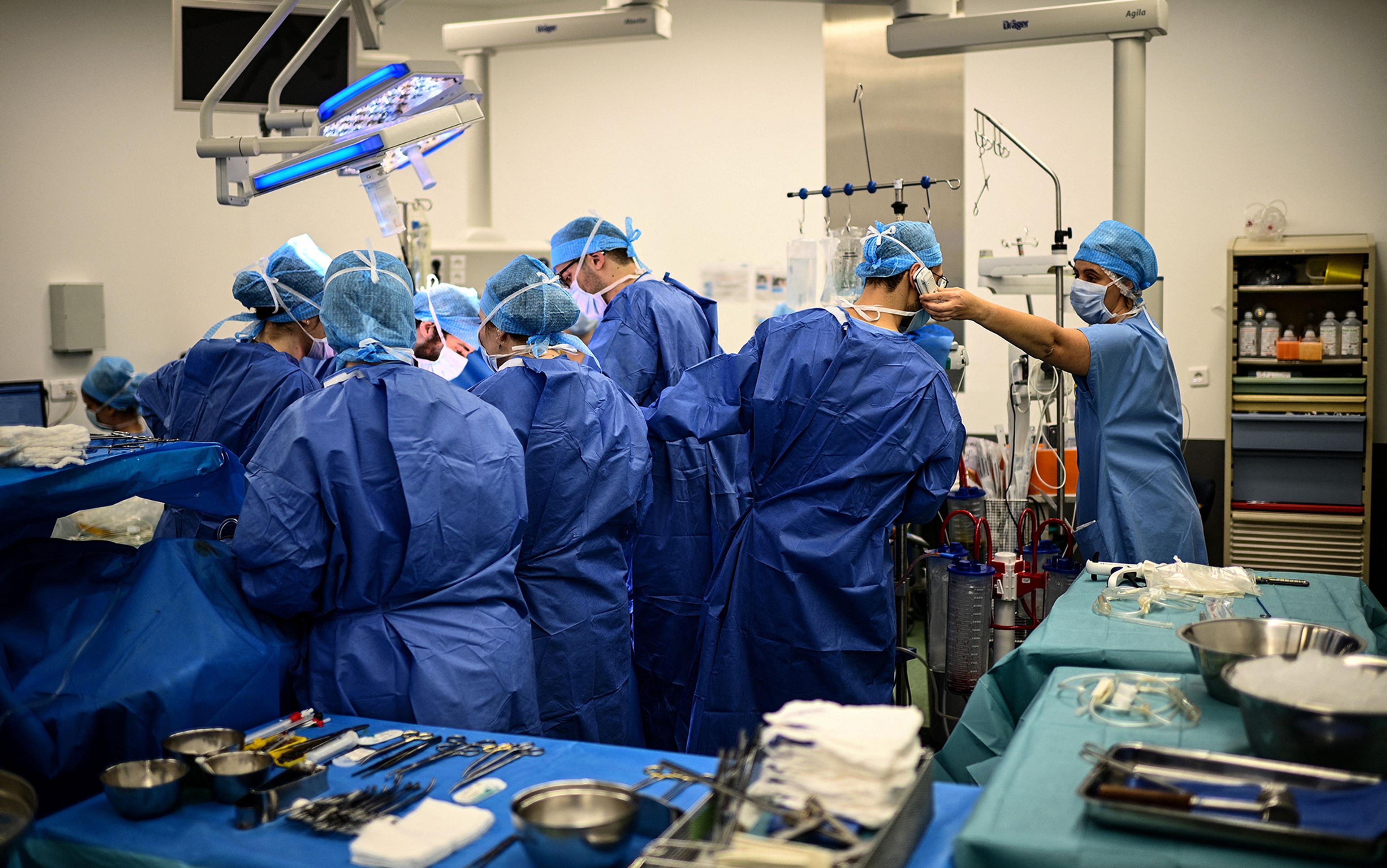

Last hours of an organ donor

In the liminal time when the brain is dead but organs are kept alive, there is an urgent tenderness to medical care

Ronald W Dworkin

Archaeology

Why make art in the dark?

New research transports us back to the shadowy firelight of ancient caves, imagining the minds and feelings of the artists

Izzy Wisher

Stories and literature

Do liberal arts liberate?

In Jack London’s novel, Martin Eden personifies debates still raging over the role and purpose of education in American life

We use cookies to enhance our website for you. Proceed if you agree to this policy or learn more about it.

- Essay Database >

- Essay Examples >

- Essays Topics >

- Essay on Money

The Human Connection Of Love And Loneliness Essay Examples

Type of paper: Essay

Topic: Money , Love , Parents , Life , Family , America , United States , Women

Words: 1800

Published: 01/15/2020

ORDER PAPER LIKE THIS

In Short-Story Characters

Loneliness is a human condition that people almost universally wrestle with, at least during some point in their lives, which is why it is such a compelling subject for writers to depict with their characters. According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, “lonely” is defined as “being without company, cut off from others, not frequented by human beings, sad from being alone, and producing a feeling of bleakness or desolation” (n.d.). A person may feel lonely when all his friends are going away to college but he is still in his hometown working at the same job he has had through high school, when burdened with a secret that only he knows, or when other people make fun of him for some personal quality that he can do nothing about. The girl named Jig from Ernest Hemingway’s story, “Hills Like White Elephants,” Paul from D.H. Lawrence’s story, “The Rocking Horse Winner,” and Dee from Alice Walker’s story, “Everyday Use,” all feel loneliness for different reasons. The loneliness that these characters feel is because of either a lack of or a perceived lack of love in their lives. In Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants,” Jig and an American man, whom she is in a relationship with, are waiting for a train to arrive in the town of Ebro, Spain. Her loneliness and the reason for it is never mentioned specifically in the text. Instead, much is revealed through the dialogue of the characters. As Jig and the American drink beers while waiting for the train’s arrival, she observes the hills in the distance and says, “They look like white elephants,” to which he responds, “I’ve never seen one,” and she replies, “No, you wouldn’t have” (167). These sentences they exchange reveal a lot about the character of their relationship. In a literal sense, Jig is commenting fancifully on the landscape, and rather than join in her imaginings, the American says, “I’ve never seen one,” which dismisses her observation as if it lacked connection to reality and is therefore not rational (167). When Jig replies, “No, you wouldn’t have,” she implies, insultingly, that the American has a limited mind and experience, as well as acknowledges that he is unwilling to make a real connection with her. Additionally, the term “white elephant” is an English language idiom meaning “an expensive burden” (“White elephant,” n.d.). It is unlikely that Jig herself is conscious of the idiomatic meaning of “white elephant,” and her observation comes from the rising of the literally white hills from the bleak landscape surrounding Ebro. However, Hemingway is certainly aware of the term and its use is no coincidence as it foreshadows another revelation in the story, when the American says, “It’s really a simple operation, Jig” (168). Although subtle, it is obvious that one of the problems in the couple’s relationship is that Jig is pregnant, and the American wants her to have an abortion. The couple’s relationship lacks love. It seems as if the American lacks love for Jig, and as a result she feels lonely. The pregnancy, he says, is “the only thing that bothers us. It’s the only thing that’s made us unhappy” (168). Jig seems to be more aware that there is a greater problem with their relationship, the lack of love, when she says, “But if I do it, then it will be nice again if I say things are like white elephants, and you’ll like it?” (168). Through this query, she questions the idea that the connection caused by love can exist between them. Jig is at least unconsciously aware that if her relationship with the American had love, she would never need to ask the question, “But if I do it, then it will be nice again if I say things are like white elephants, and you’ll like it?” (168). It is easy to imagine the difference it would have made from the beginning of the story if, instead of responding dismissively, “I’ve never seen one,” the American had instead clapped his hands and said, “Well, I’ll be! You’re right. They look like a whole pack of white elephants, a whole crowd over there!” (169). The two of them would have laughed, enjoyed the moment, the waiting for the train, their beers, and the observation that only the two of them noticed. Jig would not feel so lonely if she was surer that the father of her unborn child loved her. In D.H. Lawrence’s “The Rocking Horse Winner,” Paul is a young boy living in a household in which his parents value money over their children. They live in a fancy house, yet there was enough money to satisfy the parents. Even though the mother “married for love, and the love turned to dust,” she is unable to find any place in her heart for her three children, and “she herself knew that at the center of her heart was a hard little place that could not feel love, no, not for anybody” (750). The values of the mother, to believe that luck is the source of money, and her lack of love, greatly influence Paul, who is a naturally curious child. It is impossible for a child who knows his mother does not love him not to try to find a reason why and a way to make himself lovable. He begins to equate being lucky and getting money with the thing that will bring him the love he needs in his life, so his mother will love him, and so that he will not feel this lack and so lonely. By the end of the story, Paul has acquired a great deal of money through his luck at betting on horses, but he dies from his exertions. The lack of love in Paul’s life originates with his mother. She is incapable of focusing on anything else but the acquiring of money, neglecting her children emotionally. The lack of love also comes from the father, who is apparently never present, and his Uncle Oscar, who is more interested in Paul as a curiosity and experiment rather than as the person he is. If just one person had taken the curious Paul under his or her wing and showed him love, his value to them as a human being, his own passion and love would not be misdirected in a single-minded frenzied quest to seek out the money that became a substitute for the nutrition his soul lacked. Paul is unable to steer away from his focus on luck and making money because he has no better example to show him that there is more to life than that. In Alice Walker’s “Everyday Use,” Dee is the brilliant older daughter that the narrator, the mother, compares to her duller younger daughter, Maggie. The mother describes Dee as almost a perfect person, with “nicer hair and a fuller figure” than Maggie, “determined to stare down any disaster in her efforts,” and as a person so put-together that “At sixteen she had a style of her own: and knew what style was” (719). Dee seems to be a person who knows who she is, what she wants, and has a bright future ahead of her because of it. However, Dee lacks love. She hates the house she grew up in, is critical of her mother and Maggie’s words and habits, and had few friends (719). Her focus is completely on herself and her appearance. It is some surprise to the mother when Dee comes to visit with her man, Hakim-a-barber, and is apparently friendly. “Oh, Mama! . . . O never knew how lovely these benches are,” she observes, surprising her mother, who thought that Dee would probably hate the house and be critical of everything about it during her visit (720). This is, however, not a reversal in attitude for Dee. When she finds out that some quilts she admires are going to go to Maggie when Maggie gets married, and that Maggie would use the quilts in the way quilts were designed to be used, she objects to it. Mama says, “What would you do with them?” and Dee responds, “Hang them” (721). When Mama rejects the idea of giving the quilts to Dee, Dee leaves. It is apparent that Dee has not changed, no matter how different she looks on the outside. Dee may not realize it because she is so selfish, but she is a very lonely character, without real admirers or anything of lasting value. Dee fails to love anything in life other than her own self. If she had felt love for her family, for her heritage, or anything else, she would not be such a lonely character because everything in her life would have a real value, one that she could share with others. She is able to see the physical beauty of the quilt, but her lack of love fails to acknowledge or appreciate who made the quilt or why it was created. If she had love in her life for anything or anyone but herself, she could see the value of things beyond a pretty façade, and would not spend her life on an endless quest to find fulfillment by surrounding herself with pretty things whose origin she cannot understand. The characters in these stories, who suffer from loneliness, show the many ways that the value of love is important to having a fulfilling life. Love is a value that helps keep a community of people healthy, emotionally and even physically. In fellow students, love and a sense of community are often forgotten in exchange for a focus on rivalry and putting each other down. A student who receives the best grade in a paper receives jeers from other students. If love and the other things that accompany it, such as respect, appreciation, and cooperation, replaced this rivalry, students would not put each other down for a job well done, but would ask the successful one how he or she did it in order to improve their own work. With love, all could attain more success, as well as a healthier, happier sense of community. With love, everyone would be less lonely.

Works Cited

Hemingway, Ernest. “Hills Like White Elephants.” Introduction to Literature. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2012. 166-169. Print. Lawrence, D.H. “The Rocking Horse Winner.” Introduction to Literature. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2012. 750-757 Print. “Lonely.” Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Merriam-Webster, Inc., n.d. Web. 22 Nov. 2012. Walker, Alice. “Everyday Use.” [Class Materials], n.d. 717-723. Print. “White elephant.” UsingEnglish.com. UsingEnglish.com, Ltd., n.d. Web. 22 Nov. 2012.

Cite this page

Share with friends using:

Removal Request

Finished papers: 1684

This paper is created by writer with

ID 284469167

If you want your paper to be:

Well-researched, fact-checked, and accurate

Original, fresh, based on current data

Eloquently written and immaculately formatted

275 words = 1 page double-spaced

Get your papers done by pros!

Other Pages

Essay on the articles of confederation, on line module 8 essay sample, example of sociology essay 4, good argumentative essay on youre name, essay on comparing college students geographically close and long distance friendships, good psychological disorders course work example, good example of research paper on autism, mediatory should the paintings value that much essay examples, example of course work on letter of complaint, example of course work on data interpretation practicum, example of research paper on stage 2, essay on bayeux tapestry experience, review report sample, communication processes course work samples, free essay on language analysis, example of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder research paper, good example of certification preparation course work, good course work about investment analysis, report on accessing coolschool and scrubs companies, good comparison paper essay example, branigan essays, bolles essays, bogey essays, breta essays, bodner essays, birks essays, bouck essays, brindley essays, bonny essays, birgit essays, brendon essays, boycotting essays, man and a woman essays, brue essays, buddy essays, national cancer institute essays, agro reports, bao reports, balmer reports, arstechnica reports, bcc reports, aspect movie reviews, appealing movie reviews.

Password recovery email has been sent to [email protected]

Use your new password to log in

You are not register!

By clicking Register, you agree to our Terms of Service and that you have read our Privacy Policy .

Now you can download documents directly to your device!

Check your email! An email with your password has already been sent to you! Now you can download documents directly to your device.

or Use the QR code to Save this Paper to Your Phone

The sample is NOT original!

Short on a deadline?

Don't waste time. Get help with 11% off using code - GETWOWED

No, thanks! I'm fine with missing my deadline

Sylvia Plath and the Loneliness of Love

By maria popova.

Yet always, always, there is an undertone of loneliness in even the most symphonic love — not the gladsome “neighboring solitudes” Rilke placed at the center of healthy companionship, but the hollowing loneliness of unbelonging, of never feeling fully and completely seen, which another great poet placed at the center of her poetry and her private anguish before she perished by that loneliness.

Sylvia Plath (October 27, 1932–February 11, 1963) was still a teenager when she began facing the deepest existential questions, untangling them with uncommon lucidity on the pages of her diary, which now survive as The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath ( public library ) — the dazzling and at times discomposing posthumous echo of personhood that gave us the young Plath on finding nonreligious divinity in nature , the ecsatsy of curiosity , and her thoughts on life, death, hope and happiness .

In an entry from the winter of her freshman year at Smith College, upon returning to her dorm room after a four-day blur with her family for Thanksgiving, she writes:

Now I know what loneliness is, I think. Momentary loneliness, anyway. It comes from a vague core of the self — like a disease of the blood, dispersed throughout the body so that one cannot locate the matrix, the spot of contagion. […] This loneliness will blur and diminish, no doubt, when tomorrow I plunge again into classes, into the necessity of studying for exams. But now, that false purpose is lifted and I am spinning in a temporary vacuum… The routine is momentarily suspended and I am lost. There is no living being on earth at this moment except myself. I could walk down the halls, and empty rooms would yawn mockingly at me from every side.

Peering beyond the immediate situation, beyond this particular moment in life, she casts a darkly prognostic eye toward the rosary of moments stringing her uncertain future — a future that would soon include a passionate but damaging love , a future cut short by her lonely pain — and adds:

God, but life is loneliness, despite all the opiates, despite the shrill tinsel gaiety of “parties” with no purpose, despite the false grinning faces we all wear. And when at last you find someone to whom you feel you can pour out your soul, you stop in shock at the words you utter — they are so rusty, so ugly, so meaningless and feeble from being kept in the small cramped dark inside you so long. Yes, there is joy, fulfillment and companionship — but the loneliness of the soul in it’s appalling self-consciousness, is horrible and overpowering.

It was Plath’s tragedy that after chance had dealt her neurochemistry and nurture far from optimal, and that the delicious illusion of choice had led her to a complicated love that deepened her art and deepened the pain from which it sprang. But her concrete tragedy — which is a common tragedy: so often our unhealed wounds lead us to people whose claws fit those wounds and deepen them — is contoured by the luminous negative space of the opposite possibility: Some loves can unseal, irradiate, and heal those small dark old places in us where joy has been compacted into a hard dense loneliness. This possibility is folded into a glorious, maddening Möbius strip of trust: The very relationships in which we can begin to grow those twin roots of the soul require a level of trust to begin the terrifying process of being known — a process Adrienne Rich placed at the heart of every relationship in which two people have together earned the right to use the word “love,” a truly honorable relationship shaped by “a process, delicate, violent, often terrifying to both persons involved, a process of refining the truths they can tell each other.”

— Published June 18, 2021 — https://www.themarginalian.org/2021/06/18/sylvia-plath-journals-loneliness-love/ —

www.themarginalian.org

PRINT ARTICLE

Email article, filed under, books culture diaries love philosophy psychology sylvia plath, view full site.

The Marginalian participates in the Bookshop.org and Amazon.com affiliate programs, designed to provide a means for sites to earn commissions by linking to books. In more human terms, this means that whenever you buy a book from a link here, I receive a small percentage of its price, which goes straight back into my own colossal biblioexpenses. Privacy policy . (TLDR: You're safe — there are no nefarious "third parties" lurking on my watch or shedding crumbs of the "cookies" the rest of the internet uses.)

New Philosophical Essays on Love and Loving

- © 2021

- Simon Cushing 0

University of Michigan–Flint, Flint, USA

You can also search for this editor in PubMed Google Scholar

- New philosophical essays on love by a diverse group of international scholars

- Includes contributions to the ongoing debate on whether love is arational or if there are reasons for love

- Also whether love can explain the difference between nationalism and patriotism

5406 Accesses

3 Citations

1 Altmetric

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

Table of contents (14 chapters)

Front matter, introduction.

Simon Cushing

Making Room for Love in Kantian Ethics

- Ernesto V. Garcia

Iris Murdoch and the Epistemic Significance of Love

- Cathy Mason

‘Love’ as a Practice: Looking at Real People

- Lotte Spreeuwenberg

Love, Choice, and Taking Responsibility

- Christopher Cowley

Not All’s Fair in Love and War: Toward Just Love Theory

- Andrew Sneddon

Doubting Love

- Larry A. Herzberg

Love and Free Agency

- Ishtiyaque Haji

Sentimental Reasons

- Edgar Phillips

Wouldn’t It Be Nice: Enticing Reasons for Love

- N. L. Engel-Hawbecker

Love, Motivation, and Reasons: The Case of the Drowning Wife

- Monica Roland

Can Our Beloved Pets Love Us Back?

- Ryan Stringer

Romantic Love Between Humans and AIs: A Feminist Ethical Critique

- Andrea Klonschinski, Michael Kühler

Patriotism and Nationalism as Two Distinct Ways of Loving One’s Country

- Maria Ioannou, Martijn Boot, Ryan Wittingslow, Adriana Mattos

Back Matter

- Rationality

- Artificial Intelligence

- Iris Murdoch

- Non-Human Animals

About this book

Editors and affiliations, about the editor, bibliographic information.

Book Title : New Philosophical Essays on Love and Loving

Editors : Simon Cushing

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-72324-8

Publisher : Palgrave Macmillan Cham

eBook Packages : Religion and Philosophy , Philosophy and Religion (R0)

Copyright Information : The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2021

Hardcover ISBN : 978-3-030-72323-1 Published: 21 September 2021

Softcover ISBN : 978-3-030-72326-2 Published: 22 September 2022

eBook ISBN : 978-3-030-72324-8 Published: 20 September 2021

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XII, 322

Topics : Philosophy of Mind , Ethics , Social Philosophy , Emotion

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Essay About Being Alone: 5 Examples and 8 Prompts

To explore your understanding of this subject, read the following examples of an essay about being alone and prompts to use in your next essay.

Being alone and lonely are often used interchangeably, but they don’t have the same meaning.

Everyone has a different notion of what being alone means. Some think it’s physically secluding yourself from people, while others regard it as the feeling of serenity or hopelessness even in the middle of a crowd.

Being alone offers various benefits, such as finding peace and solitude to reflect and be creative. However, too much isolation can negatively impact physical and mental health .

By understanding the contrast between the meaning of being alone and being lonely, you’ll be able to express your thoughts clearly and deliver a great essay.

1. Why I Love Being Alone by Role Reboot and Chanel Dubofsky

2. why do i like being alone so much [19 possible reasons] by sarah kristenson, 3. things to do by yourself by kendra cherry, 4. the art of being alone, but not lonely by kei hysi, 5. my biggest fear was being alone by jennifer twardowski, 8 writing prompts on essay about being alone, 1. why you prefer to be alone, 2. things learned from being alone, 3. pros and cons of being alone, 4. being alone vs. being lonely, 5. the difference between being alone vs. being with someone else, 6. the fear of being alone, 7. how to enjoy your own company without being lonely.

“For me, being alone is something I choose, loneliness is the result of being alone, or feeling alone when I haven’t chosen it, but they aren’t the same, and they don’t necessarily lead to one another.”

In this essay, the authors make it clear that being alone is not the same as being lonely. They also mention that it’s a choice to be alone or be lonely with someone. Being alone is something that the authors are comfortable with and crave to find peace and clarity in their minds. For more, see these articles about being lonely .

“It’s important to know why you want to be alone. It can help you make the best of that time and appreciate this self-quality. Or, if you’re alone for negative reasons, it can help you address things in your life that may need to be changed.”

Kristenson’s essay probes the positive and negative reasons a person likes being alone. Positive reasons include creativity, decisiveness, and contentment as they remove themselves from drama.

The negative reasons for being alone are also critical to identify because they lead to unhealthy choices and results such as depression. The negative reasons listed are not being able to separate your emotions from others, thinking the people around you dislike you and being unable to show your authentic self to others because you’re afraid people might not like you.

“Whether you are an introvert who thrives on solitude or a gregarious extrovert who loves socializing, a little high-quality time to yourself can be good for your overall well-being.”

In this essay, Cherry points out the importance of being alone, whether you’re an introvert or an extrovert. She also mentions the benefits of allocating time for yourself and advises on how to enjoy your own company. Letting yourself be alone for a while will help you improve your memory, creativity, and attention to detail, making them more productive.

“You learn to love yourself first. You need to explore life, explore yourselves, grow through challenges, learn from mistakes, get out of your comfort zone, know your true potential, and feel comfortable in your own skin. The moment you love yourself, you become immune to loneliness.”

Hysi explores being alone without feeling lonely. He argues that people must learn to love and put themselves first to stop feeling lonely. This can be challenging, especially for those who put themselves last to serve others. He concludes that loving ourselves leads to a better life.

“We have to be comfortable in our own skin and be willing to be who we truly are, unapologetically. We have to love ourselves unconditionally and, through that love, be willing to seek out what our hearts truly desire — both in our relationships and in our life choices.”

The author discusses why she’s afraid of being alone and how she overcame it. Because she was scared of getting left alone, she always did things to please anyone, even if she wasn’t happy about it. What was important to her then was that she was not alone. But she realized she would still feel lonely even if she wasn’t alone.

Learning to be true to herself helped her overcome what she was afraid of. One key to happiness and fulfillment is loving yourself and always being genuine.

Did you finally have ideas about how to convey your thoughts about being alone after reading the samples above? If you’re now looking for ideas on what to talk about in your essay, here are 8 prompts to consider.

Read the best essay writing tips to incorporate them into your writing.

Today, many people assume that individuals who want to be alone are lonely. However, this is not the case for everyone.

You can talk about a universal situation or feeling your readers will easily understand. Such as wanting to be alone when you’re mad or when you’re burnout from school or work. You can also talk about why you want to be alone after acing a test or graduating – to cherish the moment.

People tend to overthink when they are alone. In this essay, discuss what you learned from spending time alone. Perhaps you have discovered something about yourself, found a new hobby, or connected with your emotions.

Your essay can be an eye-opener for individuals contemplating if they want to take some time off to be alone. Explain how you felt when alone and if there were any benefits from spending this time by yourself.

While being alone has several benefits, such as personal exploration or reflection, time to reboot, etc., too much isolation can also have disadvantages. Conduct research into the pros and cons of alone time, and pick a side to create a compelling argumentative essay . Then, write these in your essay. Knowing the pros and cons of being alone will let others know when being alone is no longer beneficial and they’ll need someone to talk to.

We all have different views and thoughts about being alone and lonely. Write your notion and beliefs about them. You can also give examples using your real-life experiences. Reading different opinions and ideas about the same things broadens your and your readers’ perspectives.

Some people like being with their loved ones or friends rather than spending time alone. In this prompt, you will share what you felt or experienced when you were alone compared to when you were with someone else. For you, what do you prefer more? You can inform your readers about your choice and why you like it over the other.

While being alone can be beneficial and something some people crave, being alone for a long time can be scary for others. Write about the things you are most afraid of, such as, “What if I die alone, would there be people who will mourn for me?” This will create an emotive and engaging essay for your next writing project.

Learning to be alone and genuinely enjoying it contributes to personal growth. However, being comfortable in your skin can still be challenging. This essay offers the reader tips to help others get started in finding happiness and tranquillity in their own company. Discuss activities that you can do while being alone. Perhaps create a list of hobbies and interests you can enjoy while being alone.

Interested in learning more? Read our guide on descriptive essay s for more inspiration!

Maria Caballero is a freelance writer who has been writing since high school. She believes that to be a writer doesn't only refer to excellent syntax and semantics but also knowing how to weave words together to communicate to any reader effectively.

View all posts

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

A Conceptual Review of Loneliness in Adults: Qualitative Evidence Synthesis

Louise mansfield.

1 Centre for Health and Wellbeing across the Lifecourse, College of Health, Medicine & Life Sciences, Brunel University London, Uxbridge UB8 3PH, UK; [email protected] (C.V.); moc.liamg@yargrck (K.G.); moc.liamg@37gnidlogxela (A.G.)

Christina Victor

Catherine meads.

2 Faculty of Health, Education, Medicine and Social Care, Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge CB1 1PT, UK; [email protected]

Norma Daykin

3 New Social Research, Faculty of IT and Communication Sciences, Tampere University, 33100 Tampere, Finland; [email protected]

Alan Tomlinson

4 Centre for Arts and Wellbeing, School of Humanities, University of Brighton, Brighton BN2 4AT, UK; [email protected] (A.T.); [email protected] (J.L.)

Alex Golding

Associated data.

All summaries of data are available in the Supplementary Material .

The paper reports an evidence synthesis of how loneliness is conceptualised in qualitative studies in adults. Using PRISMA guidelines, our review evaluated exposure to or experiences of loneliness by adults (aged 16+) in any setting as outcomes, processes, or both. Our initial review included any qualitative or mixed-methods study, published or unpublished, in English, from 1945 to 2018, if it employed an identified theory or concept for understanding loneliness. The review was updated to include publications up to November 2020. We used a PEEST (Participants, Exposure, Evaluation, Study Design, Theory) inclusion criteria. Data extraction and quality assessment (CASP) were completed and cross-checked by a second reviewer. The Evidence of Reviews of Qualitative Research (CERQual) was used to evaluate confidence in the findings. We undertook a thematic synthesis using inductive methods for peer-reviewed papers. The evidence identified three types of distinct but overlapping conceptualisations of loneliness: social, emotional, and existential. We have high confidence in the evidence conceptualising social loneliness and moderate confidence in the evidence on emotional and existential loneliness. Our findings provide a more nuanced understanding of these diverse conceptualisations to inform more effective decision-making and intervention development to address the negative wellbeing impacts of loneliness.

1. Introduction

Most of us will encounter loneliness at some point in our lives. Indeed, some philosophers argue that loneliness is a universal human experience [ 1 , 2 ]. This experience may be momentary or protracted, occur frequently or rarely, and vary in intensity. Loneliness is characterised as a homogeneous, static, and/or linear experience that is quantitatively accessible (i.e., we can measure it), and it is understood as a problem about which ‘something’ can and should be done to prevent or cure it [ 3 ]. In public health, for example, loneliness has been problematised and medicalised because of the associations with a range of negative mental and physical health outcomes [ 4 ], including increased mortality, morbidity, poorer health behaviours and excess service use [ 5 ], cardiovascular disease [ 6 , 7 ], reduced physical activity [ 8 , 9 ], poorer cognitive function [ 10 , 11 ] and depression [ 12 , 13 ]. Distinct but related concepts, most notably loneliness and social isolation, but also living alone, aloneness, and solitude are often conflated despite not being linguistically, empirically, or conceptually interchangeable. Despite the almost universality of the experience of loneliness, and an extensive research literature, it remains an enigmatic concept for individuals, researchers, policymakers, and practitioners since it is the outcome of an individual’s subjective experience.

Understanding loneliness is made more challenging because it is characterised by differing antecedents across varying populations and across individual life courses [ 14 ]. There is a lack of clarity about theories of loneliness and their application in empirical studies, and how they should be evaluated, measured, and applied in policy and practice [ 4 , 15 , 16 , 17 ]. When interpreting and using evidence about loneliness, these conceptual challenges are important to identify and address because they will have a profound influence on the generation, interpretation, and potential impact of evidence on policy, practice, and research in the field. In addition, there is a growing body of qualitative research that has not been fully explored for its contribution to bringing conceptual clarity to loneliness research. We undertook a synthesis of qualitative studies to start to address this evidence gap in 2018 with the aim of identifying, synthesising, and reporting on how the included studies have conceptualised loneliness as a way of enriching thinking and informing decision-making and practice in the field. We were not developing a new concept of loneliness. Following guidelines that reviews should be updated two years after publication, we updated the previous review to include relevant papers published up to 2020. This paper combines both reviews and summarises all the relevant literature on conceptualisations of social, emotional, and existential loneliness in diverse populations, their positive and negative attributes, and the ways people have found to alleviate loneliness as reported in academic journal articles and grey literature.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. methods.

The protocol was registered with the PROSPERO database (registration number: CRD42019124565). We followed PRISMA guidelines for conducting and reporting in this updated evidence review [ 18 ]. We employed a two-stage method, based on that proposed by key authors in the field [ 19 ]. Stage 1 identified evidence on conceptualisations, models, frameworks, and theories of loneliness and related concepts or domains. We made provision for a Stage 2 process to include additional evidence reviews for specific concepts and theories identified in Stage 1. This was not deemed necessary given the extensive evidence found at Stage 1. Our review was produced with stakeholder engagement on a project advisory board constituting personnel from key UK government departments, colleagues at the What Works Centre for Wellbeing, local and regional public health experts, and community groups. Stakeholder engagement consisted of an inception meeting to agree the protocol for the review and ongoing update meetings to discuss preliminary findings, implications of the evidence, and translation and dissemination activities.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

We used a bespoke framework, PEEST (Participants, Exposure, Evaluation, Study Design, Theory), to identify relevant literature. The inclusion criteria were agreed through peer review with our stakeholder group to reflect the focus of their work on loneliness on adults aged 16 or over and from high- or middle-income countries, using the United Nations (UN) criteria, and including both clinical and community populations. The included studies evaluated participants’ exposure to or experiences of loneliness, however conceptualised, in any setting, reported as outcomes, processes, or both. Any qualitative or mixed-methods study with qualitative component in English, published between 1945 and November 2018 (for the previous review) and December 2018 and December 2020 (for the new review) was eligible if employing an identified theory, model, concept, or framework for understanding loneliness beyond a simple definition. Studies were considered off-PEEST if they included only a simple definition of loneliness with no conceptual analysis or were background literature reviews.

2.3. Data Sources and Search Strategy

The search strategy was informed by engaging in the peer review process with our stakeholder group, bringing expertise in policymaking, practice, and academic work on loneliness, the librarians at Brunel University London and the University of Brighton, and through advice from a systematic review expert, in accordance with PRISMA guidelines [ 18 ] for reviews in public health. Full details of our search strategy are in Supplementary S1 . Eight electronic databases (Scopus, Medline (via Ovid), Eric, PsycINFO (via EBSCO), CINAHL Plus, and the Science, Social Science, Arts, and Humanities Citation Indices (via Web of Science) were searched using a combination of MeSH terms and text words. All database searches were framed by this strategy, but individual searches were appropriately revised to suit the precise requirements for each database. We hand-searched reference lists of reviews and systematic reviews published between 1945 and 2020, following PRISMA guidelines [ 18 ]. Grey literature was sought via an online call for evidence, employment of expert input, review of key-sector websites, and a Google search (a keyword search and review of titles of the first 100 hits) for the previous and new reviews.

2.4. Study Selection

Search results (titles and abstracts) were independently checked by two review authors. Where eligibility was unclear, the full article was checked. Disagreements were resolved through consensus, or a third team member considered the citation and a majority decision was made.

2.5. Data Extraction

We extracted data as reported by authors on: (a) the conceptualisation(s) of loneliness, (b) population defined by age, identity, or context, (c) positive and negative attributes of loneliness identified, and (d) mechanisms for alleviating loneliness. Data were extracted onto standardised forms independently by one reviewer and cross-checked by a second. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. Our protocol allowed us to contact authors if the required information could not be extracted and if this was essential for interpretation of their results, but we did not need to follow this procedure.

2.6. Quality Assessment

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) quality checklist for qualitative studies was used for published studies [ 20 ]. Two authors independently applied the criteria to each included study, and disagreements were resolved through discussion. For grey literature, the Public Health England (PHE) Arts for Health and Wellbeing Evaluation Framework [ 21 ] was used to judge the quality in terms of the appropriateness of the evaluation design, the rigour of the data collection and analysis and the precision of the reporting. This checklist was employed by agreement with stakeholders in the project on account of the methods and context for collecting evidence in the grey literature being less well established than the published literature.

Confidence in the Evidence of Reviews of Qualitative Research (CERQual) was used to judge confidence in the review findings, specifically the methodological limitations, relevance, coherence, and adequacy of the data [ 22 ]. Confidence was decreased if there were serious or very serious limitations in the design or conduct of the study, the evidence was not relevant to the study objectives, the findings/conclusions were not supported by the evidence, or the data were of inferior quality and inadequate in supporting the findings. Confidence was increased if the study was well designed with few limitations, the evidence was applicable to the context specified in the objectives, the findings/conclusions were supported by evidence and provided convincing explanation for any patterns found, or the data supporting findings were rich and of high quality.

2.7. Data Synthesis

The synthesis was conducted thematically using the principles of inductive and reflexive methods (see for example [ 23 ]) through the development of a broadly inductive and iterative framework or typology that identified three types of loneliness: (i) social loneliness, (ii) emotional loneliness, and (iii) existential loneliness. This framework was drafted by L.M. and N.D. and refined by the research team. Each paper was categorised as representing one or more of the types of loneliness, bringing a more nuanced understanding to the analysis, anchored in a recognition of the complex social, emotional, and contextual factors which characterise loneliness.

3.1. Search Results

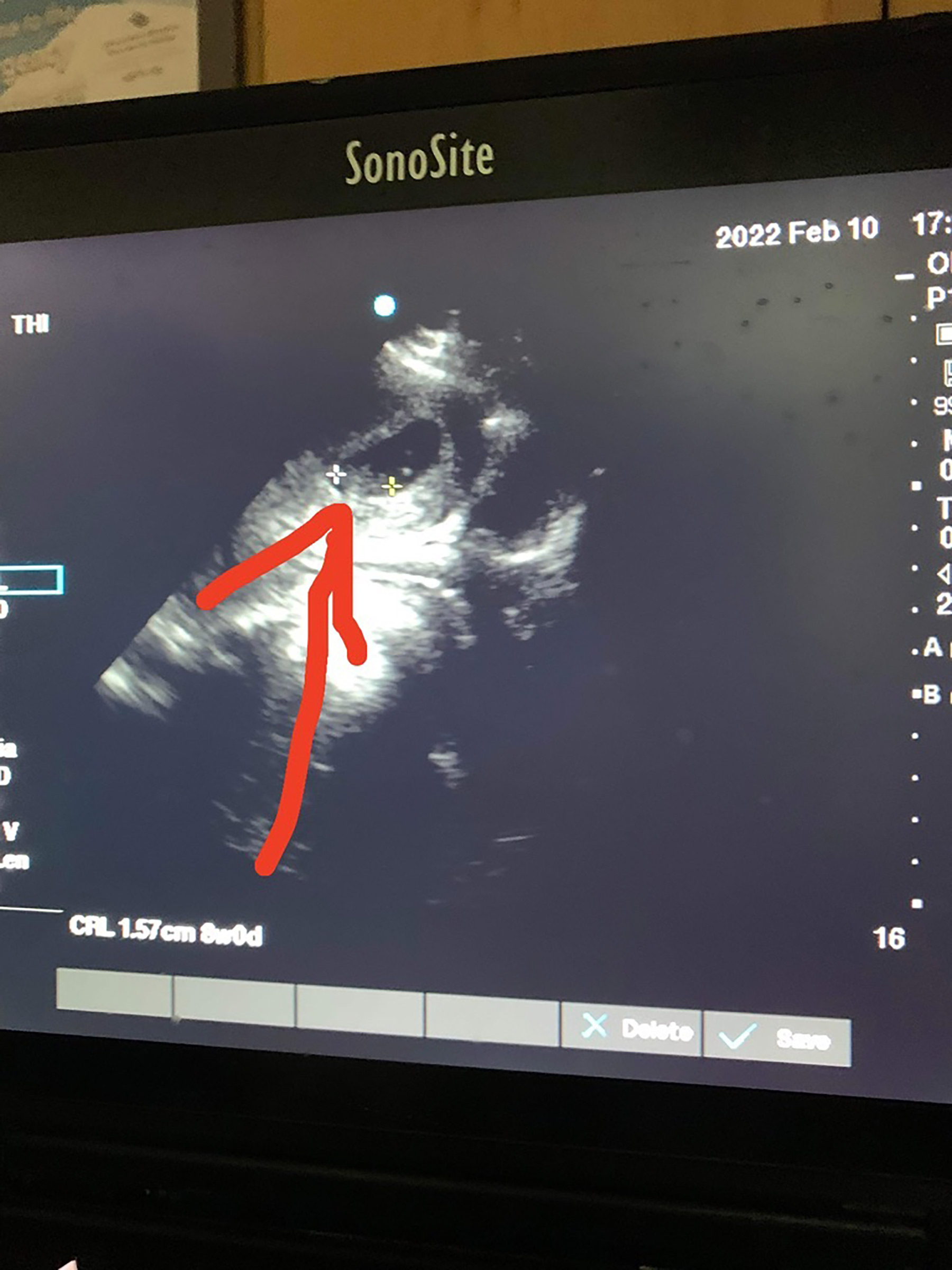

The previous review returned 5117 citations after the removal of duplicates and 15 records from additional searches (total 5192) of which 223 full texts were assessed for eligibility. From the previous review, 127 published studies and 16 grey literature reports (total 143) were included. The new review returned 3449 citations after the removal of duplicates, of which 25 full texts were assessed for eligibility. There were 10 published studies and 2 grey literature reports that were included from the new review (a total of 12). In total, 137 published studies and 18 grey literature reports are included in this systematic review, providing 155 sources of evidence conceptualising loneliness: 116 qualitative studies in journal articles and 7 book chapters (including interviews, observation, document analysis, diaries, and focus group methods); 14 mixed-methods studies (only the qualitative findings met inclusion criteria); and 18 grey literature reports. The search-screening process is illustrated in the PRISMA flowchart (see Figure 1 ). A table of excluded studies with reasons for exclusion can be found in Supplementary S2 .

PRISMA flowchart.

3.2. Study Characteristics

A summary of the characteristics of included studies can be found in a list in Supplementary S3 (with full details of study objectives, description, participants, design and analysis employed, how it conceptualises loneliness, the predominant themes, and study conclusions). In terms of populations, 68 studies reported that participants were solely aged 50+ years (43%). However, the included studies also demonstrated considerable heterogeneity including groups specified by youth and middle age, cultural, ethnic, gender and sexual orientation, people living with physical and mental illness, those living in care homes, people in clinical settings, homeless people, healthcare professionals, volunteers, parents, and prisoners. Studies were reported for 26 different countries with the largest representation from the UK ( n = 37) and the USA ( n = 33), and the earliest published study, by Jerrome, was dated 1983. Loneliness was conceptualised in the included studies principally by three types: social loneliness ( n = 108), emotional loneliness ( n = 27), and existential loneliness ( n = 20). Studies emphasised one of these three types of loneliness, and some considered the interconnections between two or more different types, which we discuss later in the section on multidimensional concepts of loneliness.

3.3. Study Quality

Following the CASP quality checklist, articles were scored out of 8, where 8 is the highest. In general, the quality was good for the published journal articles, with a relatively high number of studies (73/155) receiving scores of 7 and 8, but less so for the book chapters, most likely due to the different publishing requirements. Study quality varied across the types of loneliness studies with ratings of 7 or 8 for 48% of the social loneliness (52/108), 65% of existential loneliness (13/20), and 37% of emotional loneliness (10/27) studies. Methodological weaknesses included a lack of exact details of the researcher’s role, potential bias, and influence on the sample recruitment, setting, and responses of participants. Published studies identified ethical issues but did not always include an official record. The grey literature was of mixed quality with high-quality reports, including details of methods, theoretical analysis and recognition of limitations, and low-quality (credibility) reports providing little detail of the methods, commonly taking participant accounts at face value without theoretical analysis. A summary of quality checklist results and scores is presented in Supplementary S4 for published studies. Supplementary S5 presents quality ratings for the grey literature. The CERQual qualitative evidence profile is shown in Supplementary S6 (providing a succinct summary of the methodological limitations of all the included studies). This shows that there was much more evidence for social loneliness than emotional and existential loneliness, and we have high confidence in the social loneliness results and moderate confidence in the emotional and existential loneliness results.

3.4. Social Loneliness

Studies of social loneliness dominate the evidence accounting for 70% (108/155) of sources in the review and included populations of different ages, family carers, and a range of different employment groups [ 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 72 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 , 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94 , 95 , 96 , 97 , 98 , 99 , 100 , 101 , 102 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 106 , 107 , 108 , 109 , 110 , 111 , 112 , 113 , 114 , 115 , 116 , 117 , 118 , 119 , 120 , 121 , 122 , 123 , 124 , 125 , 126 , 127 , 128 , 129 , 130 , 131 ]. The typical conceptualisation of social loneliness was as an ‘objective’ condition framed by numbers of social connections and explained as a subjective evaluation of feeling isolated, deprived of companionship, lacking a sense of belonging, and lacking access to a satisfying social network; that is, it describes a sense of disconnection from others. How this concept was manifest and the underpinning contributary mechanisms varied across populations and contexts.

In studies focused on older 50+ years and younger populations, social loneliness was articulated as a feeling of disconnection across various domains of life including devaluation, helplessness, powerlessness, and feelings of stigma and shame. The vulnerability created by social loneliness was highlighted by accounts of financial fraud in elderly people [ 38 ]. For older adults, loss, detachment, and boredom were commonly identified as contributors to loneliness in both community and care home settings. Young people noted loneliness to be connected to the need to escape from someone or something and aligned loneliness with submission or resignation to negative feelings, often alongside feelings of shame and stigma [ 67 ]. The stigma of loneliness was reported by a wide range of groups, including people with HIV and with cancer [ 24 ], homeless people [ 25 , 32 , 74 , 111 ], female prisoners [ 43 ], men who have sex with other men [ 53 ], transgender people [ 108 ], and older people living in care settings [ 29 ]. To clarify, within the context of loneliness, stigma is understood to mean some kind of marginalisation, feelings of disgrace, or exclusion. If the papers did not directly use the term ‘stigma’ but used one of these concepts, we took it to mean stigmatisation.

There were groups or contexts where the feeling of disconnection associated with social loneliness took specific forms. Cultural difference was reported as a potential source of social loneliness in older population groups [ 69 , 82 ]. For international students, the absence of intimate personal connections combined with a lack of cultural fit created ‘cultural loneliness’, a version of social loneliness generated by the absence of their cultural and linguistic settings [ 112 ]. This notion of cultural loneliness could persist even when people had good access to social networks. Studies of social loneliness in the employment context identified a lack of support and employment-related ‘distancing’ or isolation from others from a diverse range of employees including long-haul truck drivers [ 26 ], homeworkers [ 46 ], school principals [ 57 , 60 , 113 ], medical educators [ 96 ], professional golfers [ 40 ], and senior corporate managers [ 104 ], as well as family caregivers [ 45 , 98 ]. Homeworkers and family caregivers seem to be especially vulnerable. Both groups experienced a sense of being cut off from their networks, professional and personal, because of the restrictions their respective roles had on their personal life [ 46 , 98 ]. For family caregivers, not feeling understood and being denied recognition for their role was experienced alongside more generic feelings of powerlessness and helplessness to take control of live events.

Experiences of illness and healthcare led to or compounded social loneliness in ways not reported for other population groups. In care homes, feeling lonely was exacerbated by issues preventing carers from providing adequate care (e.g., limited resources, time pressures, and professional rules) [ 83 ]. For stroke patients, a lack of support and contact, a sense of being unable to contribute, and not having an intimate relationship contributed to loneliness [ 109 ]. The design of healthcare environments can generate social loneliness as illustrated by a stroke ward, which while allowing privacy and supporting efficient clinical care, increased loneliness and created barriers to social connection [ 25 ]. This example provides one of the few explanations of loneliness not simply attributable to individual characteristics. In mental health contexts, social loneliness was affected by external environments, activities, and therapies/treatment, as well as people [ 121 ]. Social loneliness arose as a result of physical, cognitive, behavioural, and emotional responses following traumatic brain injury since these changes could affect existing relationships, leading to the loss of old friends and creating difficulties in making new ones [ 85 ].

Solutions to social loneliness were numerous and diverse in this evidence base. For older adults, services to alleviate social loneliness were largely focussed on increasing social contacts. These included friendship clubs [ 44 ], music provision [ 127 ], museum-based social prescribing [ 129 , 131 ], local history cafes [ 119 ], broadly defined community-based approaches [ 30 , 58 , 89 , 100 , 125 ], and health-messaging services [ 49 , 124 ]. Community-based approaches to alleviating social loneliness were explored where community leaders worked with older women [ 100 ]. These suggested that increasing independence, improving communication and developing mentoring, buddying, and intergenerational befriending programmes could provide relevant support to women of older age [ 100 ]. Intergenerational approaches using reverse mentoring in which younger adults trained older people in the use of information technology (IT) were reported as successful in alleviating self-reported social loneliness in older people in one study [ 33 ]. Provision of social activities to alleviate social loneliness in nursing homes could include a range of activities (e.g., self-awareness programmes, humour sessions, social engagements, and faith-based activities), but these were only associated with self-reported reductions in social loneliness if the activities were relevant to older people [ 72 , 80 ].

Young people used a variety of coping strategies for managing social loneliness and preserving and extending social connections. These included distraction, seeking help from professionals and institutions, support seeking, self-reliance, and problem-solving behaviours [ 67 , 112 , 118 ]. Although social loneliness in young people was difficult to identify, youth workers could help to prevent a downward spiral by addressing loneliness risk at key moments, which would differ amongst individuals, but may be related to relationship concerns, mental health issues, and a range of perceived stressors in life [ 128 ].

Studies reported a range of strategies for addressing workplace social loneliness in different contexts, including provision of opportunities to socialise and maintaining connections with people who provide social support [ 26 ]. The use of mobile technologies, such as smartphones, widened possibilities for homeworkers to socialise while retaining access to emails and remaining contactable by clients, although the use of technological devices did not necessarily address professional isolation in homeworkers [ 46 ]. Strategic responses to alleviating social loneliness at the organisational level were noted in the context of academic institutions as part of a wider examination of the role of social support in improving mental wellbeing [ 6 ]. In wider work contexts, the extent to which senior managers felt lonely was also dependent on coping strategies they used, including mental and physical disconnection, adopting a healthy lifestyle, gaining support from one’s network, and affecting and influencing others.

3.5. Emotional Loneliness

A total of 27 of the 155 included studies conceptualised emotional loneliness with a ‘loss model’ or ‘primary relationship deficit’ approach, which was used in all but two of the studies as the explanatory framework [ 132 , 133 , 134 , 135 , 136 , 137 , 138 , 139 , 140 , 141 , 142 , 143 , 144 , 145 , 146 , 147 , 148 , 149 , 150 , 151 , 152 , 153 , 154 , 155 , 156 , 157 , 158 ]. A common theme in conceptualisations of emotional loneliness was the connection with social isolation and a loss or lack of good quality social relationships in all the included studies in this theme. However, in contrast to social loneliness, the sense of loss, disconnection, withdrawal, detachment, or alienation from people and places and feelings of abandonment and exclusion was resultant from a lack of a sense of belonging or recognition and, for older adults, perceptions of agism and stereotyping. Negative emotions identified in conceptualisations of emotional loneliness included sadness, fear, anxiety, and worry. Although it overlaps with social loneliness, the emotional aspect within this conceptualisation of loneliness requires addressing in a distinct way because these negative feelings occur even when one is in close contact with people. Positive emotions connected to emotional loneliness were also conceptualised in terms of optimistic perceptions of aloneness and solitude associated with learning to cope with loneliness and adjusting to imposed loneliness. Emotional loneliness was reported as both acute, temporary, and subject to negotiation and change, but also permanent, long-lasting, and associated with detrimental mental and physical health.

Emotional loneliness was described by older people as a type of inner pain or suffering, a feeling to be kept hidden and silent because of fears of being stigmatised as lonely and old, becoming a burden on family and friends, and feeling responsible for controlling emotional aspects of loneliness [ 140 , 141 , 150 , 151 ]. Negative feelings associated with loss [ 133 , 134 , 135 , 137 , 140 , 141 , 150 , 154 , 156 ], disconnection, withdrawal, detachment, or alienation from people and places [ 135 , 150 , 152 , 156 ], a feeling of abandonment [ 137 , 143 ], exclusion [ 141 ], and a sense of losing or being in conflict with ones’ established identity [ 135 , 140 , 144 , 145 ] were descriptions of emotional loneliness in old age. Two studies focussed on young people, highlighting a dearth of studies in this area [ 139 , 149 ]. Both studies related to young people growing up in particular family contexts: living with a parent diagnosed with cancer and having parents who were Holocaust survivors, highlighting specific exclusionary contexts. For the parental cancer patient context, key exclusionary processes included failure of professionals to explain the situation to them, being left out of decisions and conversations connected to diagnoses, and treatment of their parents. Alongside this, feelings of uncertainty about the future, fear of losing a parent, and a sense that they were not equipped to cope generated a sense of distance or disconnection from others. For children of parents who were Holocaust survivors, emotional loneliness was a cognitive reaction to parental trauma [ 149 ] and a consequence of negative self-comparison to families without such trauma. Alleviating this kind of emotional loneliness was associated with support and comfort offered by family members and being given accurate information by healthcare professionals, which combined to provide a sense of relief from emotional loneliness for the young people.