- Marketing Strategy

- Five Forces

- Business Lists

- Competitors

- Marketing and Strategy ›

Extensive Problem Solving - Definition, Importance & Example

What is extensive problem solving.

Extensive problem solving is the purchase decision marking in a situation in which the buyer has no information, experience about the products, services and suppliers. In extensive problem solving, lack of information also spreads to the brands for the product and also the criterion that they set for segregating the brands to be small or manageable subsets that help in the purchasing decision later. Consumers usually go for extensive problem solving when they discover that a need is completely new to them which requires significant effort to satisfy it.

The decision making process of a customer includes different levels of purchase decisions, i.e. extensive problem solving, limited problem solving and routinized choice behaviour.

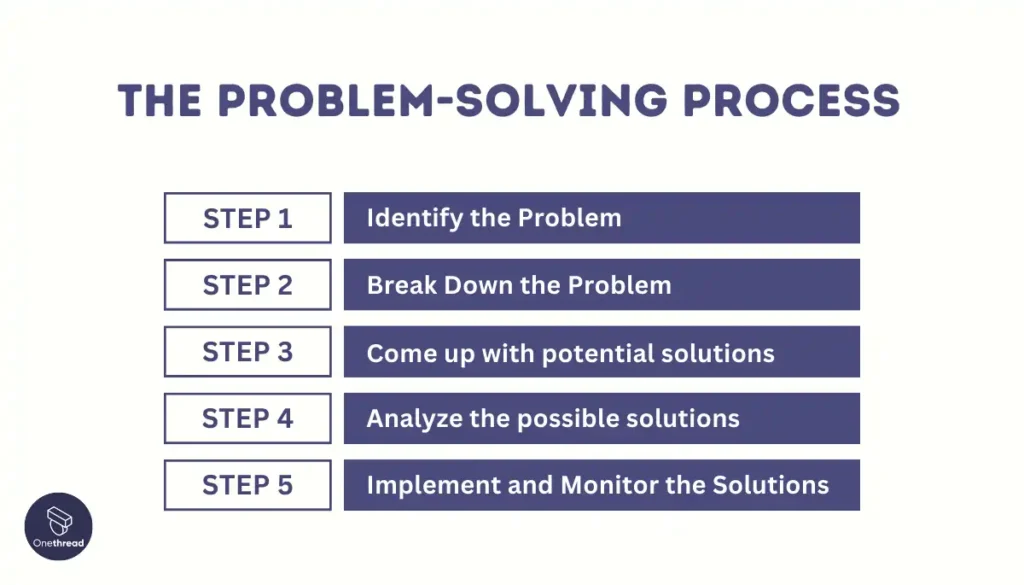

Elements of Extensive Problem Solving

The various parameters which leads to extensive problem solving are:

1. Highly Priced Products: Like a car, house

2. Infrequent Purchases: Purchasing an automobile, HD TV

3. More Customer Participation: Purchasing a laptop with selection of RAM, ROM, display etc

4. Unfamiliar Product Category: Real-estate is a very unexplored category

5. Extensive Research & Time: Locality of buying house, proximity to hospital, station, market etc.

All these parameters or elements leads to extensive problem solving for the customer while taking a decision to make a purchase.

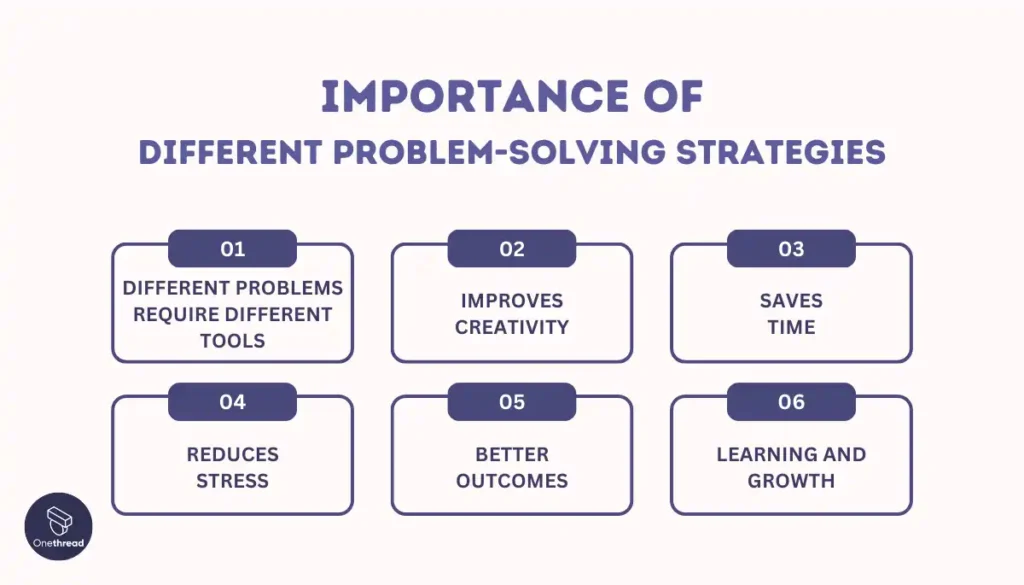

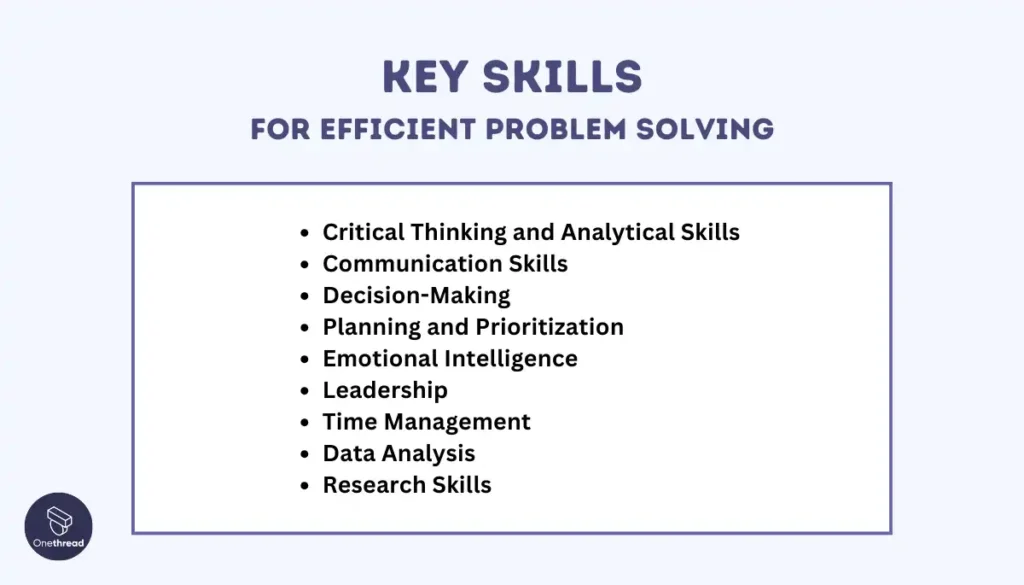

Importance of Extensive Problem Solving

It is very important for marketers to know the process that customers go through before purchasing. They cannot rely upon re-buys and word of mouth all the time for acquiring new customers. The customer in general goes through problem recognition, information search, evaluation, purchase decision and post-purchase evaluation. Closely related to a purchase decision is the problem solving phase. A new product with long term investment leads to extensive problem solving from a customer. This signifies that not all buying situations are same. A rebuy is very much different from a first choice purchase. The recognition that a brand enjoys in a customer’s mind helps the customer to make purchase decisions easily. If the brand has a dedicated marketing communication effort, whenever a consumer feels the need for a new product, they instantly go for it.

To help customers in extensive problem solving, companies must have clear transparent communication. It is thus very important for marketers to use a proper marketing mix so that they can have some cognition from their customers when they think of new products. With the advent of social media, the number of channels for promotion have hugely developed and they require a clear understanding on the segment of customer that each channel serves. The communication channels should lucidly differentiate themselves from other brands so that they are purchased quickly and easily.

Example of Extensive Problem Solving

Let us suppose, that Amber wants to buy a High Definition TV. The problem being, she has no idea regarding it. This is a case of extensive problem solving as the amount of information is low, the risk she is taking is high as she is going with the opinion that she gathers from her peers, the item is expensive and at the same time it also demands huge amount of involvement from the customer. Similarly, buying high price and long-term assets or products like car, motorcycle, house etc leads to extensive problem solving decision for the customers.

Hence, this concludes the definition of Extensive Problem Solving along with its overview.

This article has been researched & authored by the Business Concepts Team . It has been reviewed & published by the MBA Skool Team. The content on MBA Skool has been created for educational & academic purpose only.

Browse the definition and meaning of more similar terms. The Management Dictionary covers over 1800 business concepts from 5 categories.

Continue Reading:

- Sales Management

- Market Segmentation

- Brand Equity

- Positioning

- Selling Concept

- Marketing & Strategy Terms

- Human Resources (HR) Terms

- Operations & SCM Terms

- IT & Systems Terms

- Statistics Terms

What is MBA Skool? About Us

MBA Skool is a Knowledge Resource for Management Students, Aspirants & Professionals.

Business Courses

- Operations & SCM

- Human Resources

Quizzes & Skills

- Management Quizzes

- Skills Tests

Quizzes test your expertise in business and Skill tests evaluate your management traits

Related Content

- Inventory Costs

- Sales Quota

- Quality Control

- Training and Development

- Capacity Management

- Work Life Balance

- More Definitions

All Business Sections

- Business Concepts

- SWOT Analysis

- Marketing Strategy & Mix

- PESTLE Analysis

- Five Forces Analysis

- Top Brand Lists

Write for Us

- Submit Content

- Privacy Policy

- Contribute Content

- Web Stories

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Individual Consumer Decision Making

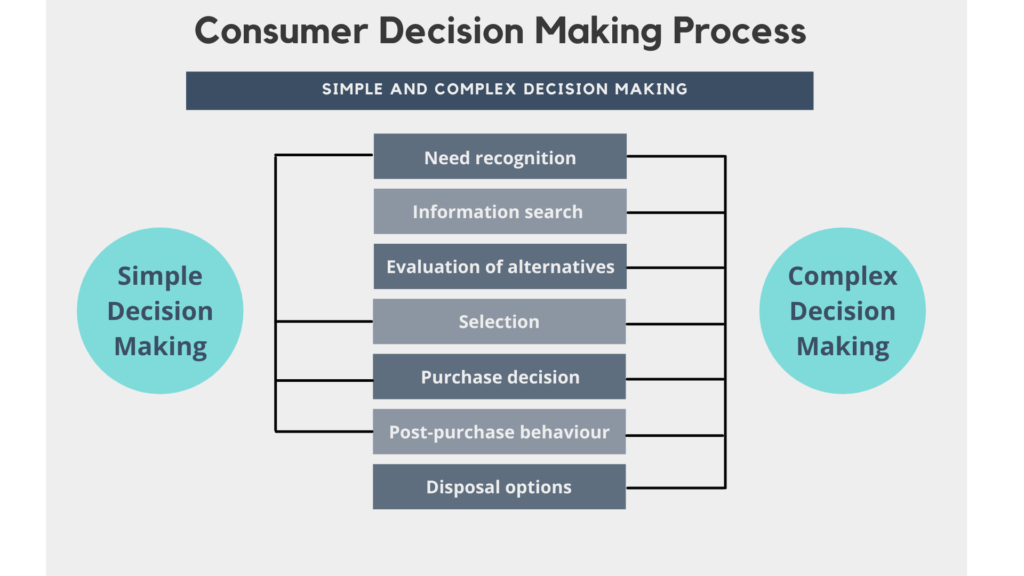

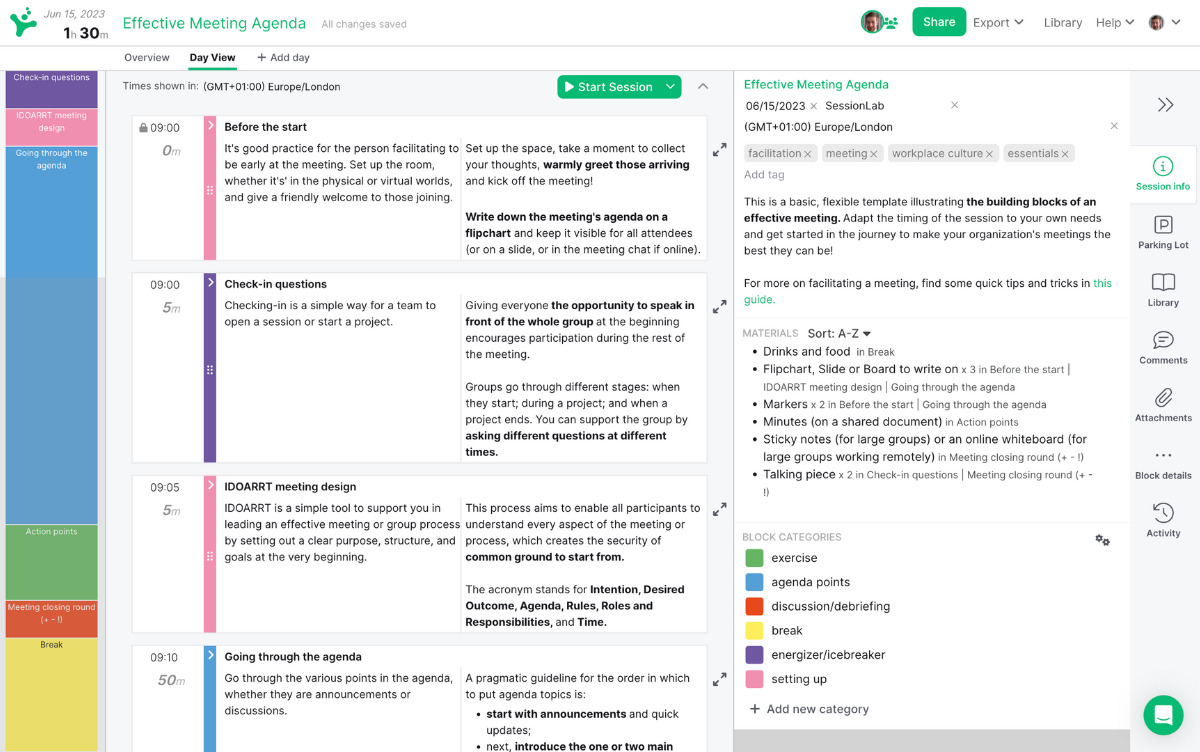

29 Consumer Decision Making Process

An organization that wants to be successful must consider buyer behavior when developing the marketing mix. Buyer behavior is the actions people take with regard to buying and using products. Marketers must understand buyer behavior, such as how raising or lowering a price will affect the buyer’s perception of the product and therefore create a fluctuation in sales, or how a specific review on social media can create an entirely new direction for the marketing mix based on the comments (buyer behavior/input) of the target market.

The Consumer Decision Making Process

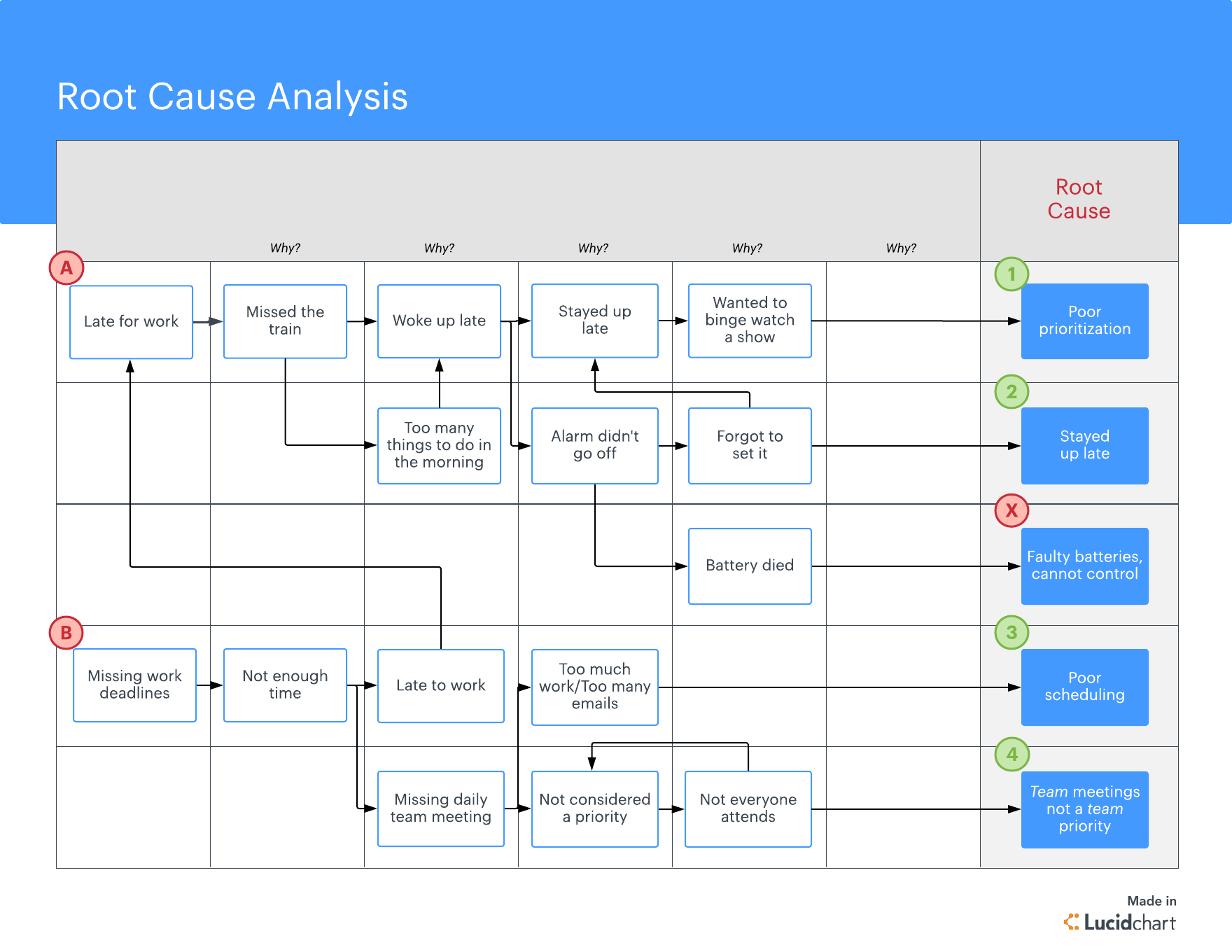

Once the process is started, a potential buyer can withdraw at any stage of making the actual purchase. The tendency for a person to go through all six stages is likely only in certain buying situations—a first time purchase of a product, for instance, or when buying high priced, long-lasting, infrequently purchased articles. This is referred to as complex decision making .

For many products, the purchasing behavior is a routine affair in which the aroused need is satisfied in a habitual manner by repurchasing the same brand. That is, past reinforcement in learning experiences leads directly to buying, and thus the second and third stages are bypassed. This is called simple decision making .

However, if something changes appreciably (price, product, availability, services), the buyer may re-enter the full decision process and consider alternative brands. Whether complex or simple, the first step is need identification (Assael, 1987).

When Inertia Takes Over

Need Recognition

Whether we act to resolve a particular problem depends upon two factors: (1) the magnitude of the discrepancy between what we have and what we need, and (2) the importance of the problem. A consumer may desire a new Cadillac and own a five-year-old Chevrolet. The discrepancy may be fairly large but relatively unimportant compared to the other problems they face. Conversely, an individual may own a car that is two years old and running very well. Yet, for various reasons, they may consider it extremely important to purchase a car this year. People must resolve these types of conflicts before they can proceed. Otherwise, the buying process for a given product stops at this point, probably in frustration.

Once the problem is recognized it must be defined in such a way that the consumer can actually initiate the action that will bring about a relevant problem solution. Note that, in many cases, problem recognition and problem definition occur simultaneously, such as a consumer running out of toothpaste. Consider the more complicated problem involved with status and image–how we want others to see us. For example, you may know that you are not satisfied with your appearance, but you may not be able to define it any more precisely than that. Consumers will not know where to begin solving their problem until the problem is adequately defined.

Marketers can become involved in the need recognition stage in three ways. First they need to know what problems consumers are facing in order to develop a marketing mix to help solve these problems. This requires that they measure problem recognition. Second, on occasion, marketers want to activate problem recognition. Public service announcements espousing the dangers of cigarette smoking is an example. Weekend and night shop hours are a response of retailers to the consumer problem of limited weekday shopping opportunities. This problem has become particularly important to families with two working adults. Finally, marketers can also shape the definition of the need or problem. If a consumer needs a new coat, do they define the problem as a need for inexpensive covering, a way to stay warm on the coldest days, a garment that will last several years, warm cover that will not attract odd looks from their peers, or an article of clothing that will express their personal sense of style? A salesperson or an ad may shape their answers

Information Search

After a need is recognized, the prospective consumer may seek information to help identify and evaluate alternative products, services, and outlets that will meet that need. Such information can come from family, friends, personal observation, or other sources, such as Consumer Reports, salespeople, or mass media. The promotional component of the marketers offering is aimed at providing information to assist the consumer in their problem solving process. In some cases, the consumer already has the needed information based on past purchasing and consumption experience. Bad experiences and lack of satisfaction can destroy repeat purchases. The consumer with a need for tires may look for information in the local newspaper or ask friends for recommendation. If they have bought tires before and was satisfied, they may go to the same dealer and buy the same brand.

Information search can also identify new needs. As a tire shopper looks for information, they may decide that the tires are not the real problem, that the need is for a new car. At this point, the perceived need may change triggering a new informational search. Information search involves mental as well as the physical activities that consumers must perform in order to make decisions and accomplish desired goals in the marketplace. It takes time, energy, money, and can often involve foregoing more desirable activities. The benefits of information search, however, can outweigh the costs. For example, engaging in a thorough information search may save money, improve quality of selection, or reduce risks. The Internet is a valuable information source.

Evaluation of Alternatives

After information is secured and processed, alternative products, services, and outlets are identified as viable options. The consumer evaluates these alternatives , and, if financially and psychologically able, makes a choice. The criteria used in evaluation varies from consumer to consumer just as the needs and information sources vary. One consumer may consider price most important while another puts more weight (importance) upon quality or convenience.

Using the ‘Rule of Thumb’

Consumers don’t have the time or desire to ponder endlessly about every purchase! Fortunately for us, heuristics , also described as shortcuts or mental “rules of thumb”, help us make decisions quickly and painlessly. Heuristics are especially important to draw on when we are faced with choosing among products in a category where we don’t see huge differences or if the outcome isn’t ‘do or die’.

Heuristics are helpful sets of rules that simplify the decision-making process by making it quick and easy for consumers.

Common Heuristics in Consumer Decision Making

- Save the most money: Many people follow a rule like, “I’ll buy the lowest-priced choice so that I spend the least money right now.” Using this heuristic means you don’t need to look beyond the price tag to make a decision. Wal-Mart built a retailing empire by pleasing consumers who follow this rule.

- You get what you pay for: Some consumers might use the opposite heuristic of saving the most money and instead follow a rule such as: “I’ll buy the more expensive product because higher price means better quality.” These consumers are influenced by advertisements alluding to exclusivity, quality, and uncompromising performance.

- Stich to the tried and true: Brand loyalty also simplifies the decision-making process because we buy the brand that we’ve always bought before. therefore, we don’t need to spend more time and effort on the decision. Advertising plays a critical role in creating brand loyalty. In a study of the market leaders in thirty product categories, 27 of the brands that were #1 in 1930 were still at the top over 50 years later (Stevesnson, 1988)! A well known brand name is a powerful heuristic .

- National pride: Consumers who select brands because they represent their own culture and country of origin are making decision based on ethnocentrism . Ethnocentric consumers are said to perceive their own culture or country’s goods as being superior to others’. Ethnocentrism can behave as both a stereotype and a type of heuristic for consumers who are quick to generalize and judge brands based on their country of origin.

- Visual cues: Consumers may also rely on visual cues represented in product and packaging design. Visual cues may include the colour of the brand or product or deeper beliefs that they have developed about the brand. For example, if brands claim to support sustainability and climate activism, consumers want to believe these to be true. Visual cues such as green design and neutral-coloured packaging that appears to be made of recycled materials play into consumers’ heuristics .

The search for alternatives and the methods used in the search are influenced by such factors as: (a) time and money costs; (b) how much information the consumer already has; (c) the amount of the perceived risk if a wrong selection is made; and (d) the consumer’s predisposition toward particular choices as influenced by the attitude of the individual toward choice behaviour. That is, there are individuals who find the selection process to be difficult and disturbing. For these people there is a tendency to keep the number of alternatives to a minimum, even if they have not gone through an extensive information search to find that their alternatives appear to be the very best. On the other hand, there are individuals who feel it necessary to collect a long list of alternatives. This tendency can appreciably slow down the decision-making function.

Consumer Evaluations Made Easier

The evaluation of alternatives often involves consumers drawing on their evoke, inept, and insert sets to help them in the decision making process.

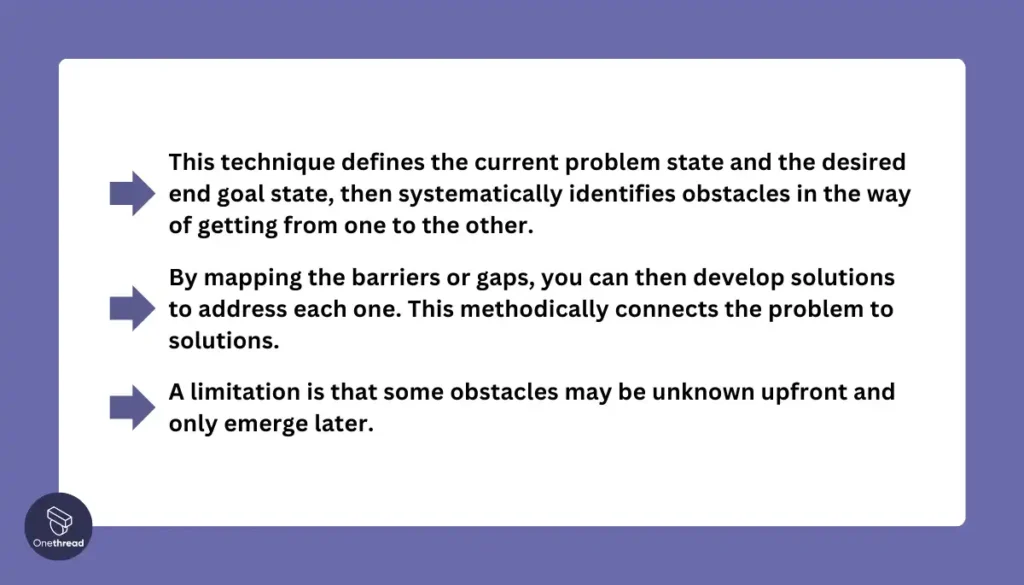

The brands and products that consumers compare—their evoked set – represent the alternatives being considered by consumers during the problem-solving process. Sometimes known as a “consideration” set, the evoked set tends to be small relative to the total number of options available. When a consumer commits significant time to the comparative process and reviews price, warranties, terms and condition of sale and other features it is said that they are involved in extended problem solving. Unlike routine problem solving, extended or extensive problem solving comprises external research and the evaluation of alternatives. Whereas, routine problem solving is low-involvement, inexpensive, and has limited risk if purchased, extended problem solving justifies the additional effort with a high-priced or scarce product, service, or benefit (e.g., the purchase of a car). Likewise, consumers use extensive problem solving for infrequently purchased, expensive, high-risk, or new goods or services.

As opposed to the evoked set, a consumer’s inept set represent those brands that they would not given any consideration too. For a consumer who is shopping around for an electric vehicle, for example, they would not even remotely consider gas-guzzling vehicles like large SUVs.

The inert set represents those brands or products a consumer is aware of, but is indifferent to and doesn’t consider them either desirable or relevant enough to be among the evoke set. Marketers have an opportunity here to position their brands appropriately so consumers move these items from their insert to evoke set when evaluation alternatives.

The selection of an alternative, in many cases, will require additional evaluation. For example, a consumer may select a favorite brand and go to a convenient outlet to make a purchase. Upon arrival at the dealer, the consumer finds that the desired brand is out-of-stock. At this point, additional evaluation is needed to decide whether to wait until the product comes in, accept a substitute, or go to another outlet. The selection and evaluation phases of consumer problem solving are closely related and often run sequentially, with outlet selection influencing product evaluation, or product selection influencing outlet evaluation.

While many consumers would agree that choice is a good thing, there is such a thing as “too much choice” that inhibits the consumer decision making process. Consumer hyperchoice is a term used to describe purchasing situations that involve an excess of choice thus making selection for difficult for consumers. Dr. Sheena Iyengar studies consumer choice and collects data that supports the concept of consumer hyperchoice. In one of her studies, she put out jars of jam in a grocery store for shoppers to sample, with the intention to influence purchases. Dr. Iyengar discovered that when a fewer number of jam samples were provided to shoppers, more purchases were made. But when a large number of jam samples were set out, fewer purchases were made (Green, 2010). As it turns out, “more is less” when it comes to the selection process.

The Purchase Decision

After much searching and evaluating, or perhaps very little, consumers at some point have to decide whether they are going to buy.

Anything marketers can do to simplify purchasing will be attractive to buyers. This may include minimal clicks to online checkout; short wait times in line; and simplified payment options. When it comes to advertising marketers could also suggest the best size for a particular use, or the right wine to drink with a particular food. Sometimes several decision situations can be combined and marketed as one package. For example, travel agents often package travel tours with flight and hotel reservations.

To do a better marketing job at this stage of the buying process, a seller needs to know answers to many questions about consumers’ shopping behaviour. For instance, how much effort is the consumer willing to spend in shopping for the product? What factors influence when the consumer will actually purchase? Are there any conditions that would prohibit or delay purchase? Providing basic product, price, and location information through labels, advertising, personal selling, and public relations is an obvious starting point. Product sampling, coupons, and rebates may also provide an extra incentive to buy.

Actually determining how a consumer goes through the decision-making process is a difficult research task.

Post-Purchase Behaviour

All the behaviour determinants and the steps of the buying process up to this point are operative before or during the time a purchase is made. However, a consumer’s feelings and evaluations after the sale are also significant to a marketer, because they can influence repeat sales and also influence what the customer tells others about the product or brand.

Keeping the customer happy is what marketing is all about. Nevertheless, consumers typically experience some post-purchase anxiety after all but the most routine and inexpensive purchases. This anxiety reflects a phenomenon called cognitive dissonance . According to this theory, people strive for consistency among their cognitions (knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, values). When there are inconsistencies, dissonance exists, which people will try to eliminate. In some cases, the consumer makes the decision to buy a particular brand already aware of dissonant elements. In other instances, dissonance is aroused by disturbing information that is received after the purchase. The marketer may take specific steps to reduce post-purchase dissonance. Advertising that stresses the many positive attributes or confirms the popularity of the product can be helpful. Providing personal reinforcement has proven effective with big-ticket items such as automobiles and major appliances. Salespeople in these areas may send cards or may even make personal calls in order to reassure customers about their purchase.

Media Attributions

- The graphic of the “Consumer Decision Making Process” by Niosi, A. (2021) is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA and is adapted from Introduction to Business by Rice University.

Text Attributions

- The sections under the “Consumer Decision Making Process,” “Need Recognition” (edited), “Information Search,” “Evaluation of Alternatives”; the first paragraph under the section “Selection”; the section under “Purchase Decision”; and, the section under “Post-Purchase Behaviour” are adapted from Introducing Marketing [PDF] by John Burnett which is licensed under CC BY 3.0 .

- The opening paragraph and the image of the Consumer Decision Making Process is adapted from Introduction to Business by Rice University which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

- The section under “Using the ‘Rule of Thumb'” is adapted (and edited) from Launch! Advertising and Promotion in Real Time [PDF] by Saylor Academy which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 .

Assael, H. (1987). Consumer Behavior and Marketing Action (3rd ed.), 84. Boston: Kent Publishing.

Green, P. (2010, March 17). An Expert on Choice Chooses. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/18/garden/18choice.html.

Consumer purchases made when a (new) need is identified and a consumer engages in a more rigorous evaluation, research, and alternative assessment process before satisfying the unmet need.

Consumer purchases made when a need is identified and a habitual ("routine") purchase is made to satisfy that need.

Purchasing decisions made out of habit.

The first stage of the Consumer Decision Making Process, need recognition takes place when a consumer identifies an unmet need.

The second stage of the Consumer Decision Making Process, information search takes place when a consumer seeks relative information that will help them identify and evaluate alternatives before deciding on the final purchase decision.

The third stage of the Consumer Decision Making Process, the evaluation of alternatives takes place when a consumer establishes criteria to evaluate the most viable purchasing option.

Also known as "mental shortcuts" or "rules of thumb", heuristics help consumers by simplifying the decision-making process.

A small set of "go-to" brands that consumers will consider as they evaluate the alternatives available to them before making a purchasing decision.

The brands a consumer would not pay any attention to during the evaluation of alternatives process.

The brands a consumer is aware of but indifferent to, when evaluating alternatives in the consumer decision making process. The consumer may deem these brands irrelevant and will therefore exclude them from any extensive evaluation or consideration.

A term that describes a purchasing situation in which a consumer is faced with an excess of choice that makes decision making difficult or nearly impossible.

A type of cognitive inconsistency, this term describes the discomfort consumers may feel when their beliefs, values, attitudes, or perceptions are inconsistent or contradictory to their original belief or understanding. Consumers with cognitive dissonance related to a purchasing decision will often seek to resolve this internal turmoil they are experiencing by returning the product or finding a way to justify it and minimizing their sense of buyer's remorse.

Introduction to Consumer Behaviour Copyright © 2021 by Andrea Niosi is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

If you still have questions or prefer to get help directly from an agent, please submit a request. We’ll get back to you as soon as possible.

Please fill out the contact form below and we will reply as soon as possible.

- Marketing, Advertising, Sales & PR

- Principles of Marketing

Types of Consumer Decision - Explained

What types of decisions do Consumers Make?

Written by Jason Gordon

Updated at April 17th, 2024

- Marketing, Advertising, Sales & PR Principles of Marketing Sales Advertising Public Relations SEO, Social Media, Direct Marketing

- Accounting, Taxation, and Reporting Managerial & Financial Accounting & Reporting Business Taxation

- Professionalism & Career Development

- Law, Transactions, & Risk Management Government, Legal System, Administrative Law, & Constitutional Law Legal Disputes - Civil & Criminal Law Agency Law HR, Employment, Labor, & Discrimination Business Entities, Corporate Governance & Ownership Business Transactions, Antitrust, & Securities Law Real Estate, Personal, & Intellectual Property Commercial Law: Contract, Payments, Security Interests, & Bankruptcy Consumer Protection Insurance & Risk Management Immigration Law Environmental Protection Law Inheritance, Estates, and Trusts

- Business Management & Operations Operations, Project, & Supply Chain Management Strategy, Entrepreneurship, & Innovation Business Ethics & Social Responsibility Global Business, International Law & Relations Business Communications & Negotiation Management, Leadership, & Organizational Behavior

- Economics, Finance, & Analytics Economic Analysis & Monetary Policy Research, Quantitative Analysis, & Decision Science Investments, Trading, and Financial Markets Banking, Lending, and Credit Industry Business Finance, Personal Finance, and Valuation Principles

What are the types of Consumer Decisions?

Consumer decisions can be categorized into three primary types:

- Routinized Response - This is the kind of decision where you don't really have to think much about it.

- Limited Problem Solving - This type of purchase decision involves a little more thinking or a little more consideration.

- Extensive Problem Solving - This is when we're making a decision to purchase and we are really going to labor over that decision.

Each of these is discussed further below.

What is a Routinized Response?

This is the kind of decision where you don't really have to think much about it. That is, it's a routine. In the context of making a purchase, this is when we make the decision to purchase without going through the consumer decision-making process. Generally, it means we simply follow or repeat a previous course of action. Think of going to the store and buying the same type or brand of grocery item that you buy every week. You do this as a routine, rather than identifying alternatives and comparing them.

What is Limited Problem Solving?

This type of purchase decision involves a little more thinking or a little more consideration. Maybe we consider different products in making our purchase. Maybe we consider how much to buy. Whatever our considerations, we're going to spend more time and effort making this decision or making this purchase.

What is Extensive Problem Solving?

This is when we're making a decision to purchase and we are really going to labor over that decision. That is, we are really going to consider it thoroughly. We may do a great deal of research. We may consult friends or look at customer reviews. We generally use this approach when it is something that we have never bought before, its very technical in nature, or when it is a very expensive item (like a car). Generally, this type of decision involves the most time, information, and effort in the evaluation of alternatives.

Related Articles

- Marketing Mix - Explained

- Captive Pricing - Explained

- Marketing Ethics - Explained

- Publicity - Explained

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Consumer Motivation and Involvement

15 Involvement Levels

Depending on a consumer’s experience and knowledge, some consumers may be able to make quick purchase decisions and other consumers may need to get information and be more involved in the decision process before making a purchase. The level of involvement reflects how personally important or interested you are in consuming a product and how much information you need to make a decision. The level of involvement in buying decisions may be considered a continuum from decisions that are fairly routine (consumers are not very involved) to decisions that require extensive thought and a high level of involvement. Whether a decision is low, high, or limited, involvement varies by consumer, not by product.

Low Involvement Consumer Decision Making

At some point in your life you may have considered products you want to own (e.g. luxury or novelty items), but like many of us, you probably didn’t do much more than ponder their relevance or suitability to your life. At other times, you’ve probably looked at dozens of products, compared them, and then decided not to purchase any one of them. When you run out of products such as milk or bread that you buy on a regular basis, you may buy the product as soon as you recognize the need because you do not need to search for information or evaluate alternatives . As Nike would put it, you “just do it.” Low-involvement decisions are, however, typically products that are relatively inexpensive and pose a low risk to the buyer if a mistake is made in purchasing them.

Consumers often engage in routine response behaviour when they make low-involvement decisions — that is, they make automatic purchase decisions based on limited information or information they have gathered in the past. For example, if you always order a Diet Coke at lunch, you’re engaging in routine response behaviour. You may not even think about other drink options at lunch because your routine is to order a Diet Coke, and you simply do it. Similarly, if you run out of Diet Coke at home, you may buy more without any information search.

Some low-involvement purchases are made with no planning or previous thought. These buying decisions are called impulse buying . While you’re waiting to check out at the grocery store, perhaps you see a magazine with a notable celebrity on the cover and buy it on the spot simply because you want it. You might see a roll of tape at a check-out stand and remember you need one or you might see a bag of chips and realize you’re hungry or just want them. These are items that are typically low-involvement decisions. Low involvement decisions aren’t necessarily products purchased on impulse, although they can be.

High Involvement Consumer Decision Making

By contrast, high-involvement decisions carry a higher risk to buyers if they fail. These are often more complex purchases that may carry a high price tag, such as a house, a car, or an insurance policy. These items are not purchased often but are relevant and important to the buyer. Buyers don’t engage in routine response behaviour when purchasing high-involvement products. Instead, consumers engage in what’s called extended problem solving where they spend a lot of time comparing different aspects such as the features of the products, prices, and warranties.

High-involvement decisions can cause buyers a great deal of post-purchase dissonance, also known as cognitive dissonance which is a form of anxiety consumers experience if they are unsure about their purchases or if they had a difficult time deciding between two alternatives. Companies that sell high-involvement products are aware that post purchase dissonance can be a problem. Frequently, marketers try to offer consumers a lot of supporting information about their products, including why they are superior to competing brands and why the consumer won’t be disappointed with their purchase afterwards. Salespeople play a critical role in answering consumer questions and providing extensive support during and after the purchasing stage.

Limited Problem Solving

Limited problem solving falls somewhere between low-involvement (routine) and high-involvement (extended problem solving) decisions. Consumers engage in limited problem solving when they already have some information about a good or service but continue to search for a little more information. Assume you need a new backpack for a hiking trip. While you are familiar with backpacks, you know that new features and materials are available since you purchased your last backpack. You’re going to spend some time looking for one that’s decent because you don’t want it to fall apart while you’re traveling and dump everything you’ve packed on a hiking trail. You might do a little research online and come to a decision relatively quickly. You might consider the choices available at your favourite retail outlet but not look at every backpack at every outlet before making a decision. Or you might rely on the advice of a person you know who’s knowledgeable about backpacks. In some way you shorten or limit your involvement and the decision-making process.

Distinguishing Between Low Involvement and High Involvement

Products, such as chewing gum, which may be low-involvement for many consumers often use advertising such as commercials and sales promotions such as coupons to reach many consumers at once. Companies also try to sell products such as gum in as many locations as possible. Many products that are typically high-involvement such as automobiles may use more personal selling to answer consumers’ questions. Brand names can also be very important regardless of the consumer’s level of purchasing involvement. Consider a low-versus high-involvement decision — say, purchasing a tube of toothpaste versus a new car. You might routinely buy your favorite brand of toothpaste, not thinking much about the purchase (engage in routine response behaviour), but not be willing to switch to another brand either. Having a brand you like saves you “search time” and eliminates the evaluation period because you know what you’re getting.

When it comes to the car, you might engage in extensive problem solving but, again, only be willing to consider a certain brand or brands (e.g. your evoke set for automobiles). For example, in the 1970s, American-made cars had such a poor reputation for quality that buyers joked that a car that’s not foreign is “crap.” The quality of American cars is very good today, but you get the picture. If it’s a high-involvement product you’re purchasing, a good brand name is probably going to be very important to you. That’s why the manufacturers of products that are typically high-involvement decisions can’t become complacent about the value of their brands.

Ways to Increase Involvement Levels

Involvement levels – whether they are low, high, or limited – vary by consumer and less so by product. A consumer’s involvement with a particular product will depend on their experience and knowledge, as well as their general approach to gathering information before making purchasing decisions. In a highly competitive marketplace, however, brands are always vying for consumer preference, loyalty, and affirmation. For this reason, many brands will engage in marketing strategies to increase exposure, attention, and relevance; in other words, brands are constantly seeking ways to motivate consumers with the intention to increase consumer involvement with their products and services.

Some of the different ways marketers increase consumer involvement are: customization; engagement; incentives; appealing to hedonic needs; creating purpose; and, representation.

1. Customization

With Share a Coke, Coca-Cola made a global mass customization implementation that worked for them. The company was able to put the labels on millions of bottles in order to get consumers to notice the changes to the coke bottle in the aisle. People also felt a kinship and moment of recognition once they spotted their names or a friend’s name. Simultaneously this personalization also worked because of the printing equipment that could make it happen and there are not that many first names to begin with. These factors lead the brand to be able to roll this out globally ( Mass Customization #12 , 2017).

2. Engagement

Have you ever heard the expression, “content is king”? Without a doubt, engaging, memorable, and unique marketing content has a lasting impact on consumers. The marketing landscape is a noisy one, polluted with an infinite number of brands advertising extensively to consumers, vying for a fraction of our attention. Savvy marketers recognize the importance of sparking just enough consumer interest so they become motivated to take notice and process their marketing messages. Marketers who create content (that isn’t just about sales and promotion) that inspires, delights, and even serves an audience’s needs are unlocking the secret to engagement. And engagement leads to loyalty.

There is no trick to content marketing, but the brands who do it well know that stepping away – far away – from the usual sales and promotion lines is critical. While content marketing is an effective way to increase sales, grow a brand, and create loyalty, authenticity is at its core.

Bodyform and Old Spice are two brands who very cleverly applied just the right amount of self-deprecating humour to their content marketing that not only engaged consumers, but had them begging for more!

Content as a Key Driver to Consumer Engagement

Engaging customers through content might involve a two-way conversation online, or an entire campaign designed around a single customer comment.

In 2012, Richard Neill posted a message to Bodyform’s Facebook page calling out the brand for lying to and deceiving its customers and audiences for years. Richard went on to say that Bodyform’s advertisements failed to truly depict any sense of reality and that in fact he felt set up by the brand to experience a huge fall. Bodyform, or as Richard addressed the company, “you crafty bugger,” is a UK company that produces and sells feminine protection products to menstruating girls and women (Bodyform, n.d.). Little did Richard know that when he posted his humorous rant to Bodyform that the company would respond by creating a video speaking directly at Richard and coming “clean” on all their deceitful attempts to make having period look like fun. When Bodyform’s video went viral, a brand that would have otherwise continued to blend into the background, captured the attention of a global audience.

Xavier Izaguirre says that, “[a]udience involvement is the process and act of actively involving your target audience in your communication mix, in order to increase their engagement with your message as well as advocacy to your brand.” Bodyform gained global recognition by turning one person’s rant into a viral publicity sensation (even though Richard was not the customer in this case).

Despite being a household name, in the years leading up to Old Spice’s infamous “The Man Your Man Should Smell Like” campaign, sales were flat and the brand had failed to strike a chord in a new generation of consumers. Ad experts at Wieden + Kennedy produced a single 30-second ad (featuring a shirtless and self-deprecating Isaiah Mustafa) that played around the time of the 2010 Super Bowl game. While the ad quickly gained notoriety on YouTube, it was the now infamous, “ Response Campaign ” that made the campaign a leader of its time in audience engagement.

3. Incentives

Customer loyalty and reward programs successfully motivate consumers in the decision making process and reinforce purchasing behaviours ( a feature of instrumental conditioning ). The rationale for loyalty and rewards programs is clear: the cost of acquiring a new customer runs five to 25 times more than selling to an existing one and existing customers spend 67 per cent more than new customers (Bernazzani, n.d.). From the customer perspective, simple and practical reward programs such as Beauty Insider – a point-accumulation model used by Sephora – provides strong incentive for customer loyalty (Bernazzani, n.d.).

4. Appealing to Hedonic Needs

A particularly strong way to motivate consumers to increase involvement levels with a product or service is to appeal to their hedonic needs. Consumers seek to satisfy their need for fun, pleasure, and enjoyment through luxurious and rare purchases. In these cases, consumers are less likely to be price sensitive (“it’s a treat”) and more likely to spend greater processing time on the marketing messages they are presented with when a brand appeals to their greatest desires instead of their basic necessities.

5. Creating Purpose

Millennial and Digital Native consumers are profoundly different than those who came before them. Brands, particularly in the consumer goods category, who demonstrate (and uphold) a commitment to sustainability grow at a faster rate (4 per cent) than those who do not (1 per cent) (“Consumer-Goods…”, 2015). In a 2015 poll, 30,000 consumers were asked how much the environment, packaging, price, marketing, and organic or health and wellness claims had on their consumer-goods’ purchase decisions, and to no surprise, 66 per cent said they would be willing to pay more for sustainable brands. (Nielsen, 2015). A rising trend and important factor to consider in evaluating consumer involvement levels and ways to increase them. So while cruelty-free, fair trade, and locally-sourced may all seem like buzz words to some, they are non-negotiable decision-making factors to a large and growing consumer market.

6. Representation

Celebrity endorsement can have a profound impact on consumers’ overall attitude towards a brand. Consumers who might otherwise have a “neutral” attitude towards a brand (neither positive nor negative) may be more noticed to take notice of a brand’s messages and stimuli if a celebrity they admire is the face of the brand.

When sportswear and sneaker brand Puma signed Rihanna on to not just endorse the brand but design an entire collection, sales soared in all the regions and the brand enjoyed a new “revival” in the U.S. where Under Armour and Nike had been making significant gains (“Rihanna Designs…”, 2017). “Rihanna’s relationship with us makes the brand actual and hot again with young consumers,” said chief executive Bjorn Gulden (“Rihanna Designs…”, 2017).

Media Attributions

- The image of two different coloured sneakers is by Raka Rachgo on Unsplash .

- The image of a coffee card in a wallet is by Rebecca Aldama on Unsplash .

- The image of an island resort in tropical destination is by Ishan @seefromthesky on Unsplash .

- The image of a stack of glossy magazine covers is by Charisse Kenion on Unsplash .

Text Attributions

- The introductory paragraph; sections on “Low Involvement Consumer Decision Making”, “High Involvement Consumer Decision Making”, and “Limited Problem Solving” are adapted from Principles of Marketing which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0.

About Us . (n.d.). Body Form. Retrieved February 2, 2019, from https://www.bodyform.co.uk/about-us/.

Kalamut, A. (2010, August 18). Old Spice Video “Case Study” . YouTube [Video]. https://youtu.be/Kg0booW1uOQ.

Bernazzani, S. (n.d.). Customer Loyalty: The Ultimate Guide [Blog post]. https://blog.hubspot.com/service/customer-loyalty.

Bodyform Channel. (2012, October 16). Bodyform Responds: The Truth . YouTube [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bpy75q2DDow&feature=youtu.be.

Consumer-Goods’ Brands That Demonstrate Commitment to Sustainability Outperform Those That Don’t. (2015, October 12). Nielsen [Press Release]. https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/press-room/2015/consumer-goods-brands-that-demonstrate-commitment-to-sustainability-outperform.html.

Curtin, M. (2018, March 30). 73 Per Cent of Millennials are Willing to Spend More Money on This 1 Type of Product . Inc. https://www.inc.com/melanie-curtin/73-percent-of-millennials-are-willing-to-spend-more-money-on-this-1-type-of-product.html.

Izaguirre, X. (2012, October 17). How are brands using audience involvement to increase reach and engagement? EConsultancy. https://econsultancy.com/how-are-brands-using-audience-involvement-to-increase-reach-and-engagement/.

Rihanna Designs Help Lift Puma Sportswear Sales . (2017, October 24). Reuters. https://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/news-analysis/rihanna-designs-help-lift-puma-sportswear-sales.

Tarver, E. (2018, October 20). Why the ‘Share a Coke’ Campaign Is So Successful . Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/articles/markets/100715/what-makes-share-coke-campaign-so-successful.asp.

Low involvement decision making typically reflects when a consumer who has a low level of interest and attachment to an item. These items may be relatively inexpensive, pose low risk (can be exchanged, returned, or replaced easily), and not require research or comparison shopping.

This concept describes when consumers make low-involvement decisions that are "automatic" in nature and reflect a limited amount of information the consumer has gathered in the past.

A type of purchase that is made with no previous planning or thought.

High involvement decision making typically reflects when a consumer who has a high degree of interest and attachment to an item. These items may be relatively expensive, pose a high risk to the consumer (can't be exchanged or refunded easily or at all), and require some degree of research or comparison shopping.

Also known as "consumer remorse" or "consumer guilt", this is an unsettling feeling consumers may experience post-purchase if they feel their actions are not aligned with their needs.

Consumers engage in limited problem solving when they have some information about an item, but continue to gather more information to inform their purchasing decision. This falls between "low" and "high" involvement on the involvement continuum.

Introduction to Consumer Behaviour Copyright © by Andrea Niosi is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

4.3: Buyer behavior as problem solving

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 21352

- John Burnett

- Global Text Project

Consumer behavior refers to buyers who are purchasing for personal, family, or group use. Consumer behavior can be thought of as the combination of efforts and results related to the consumer's need to solve problems. Consumer problem solving is triggered by the identification of some unmet need. A family consumes all of the milk in the house or the tires on the family care wear out or the bowling team is planning an end-of-the-season picnic. This presents the person with a problem which must be solved. Problems can be viewed in terms of two types of needs: physical (such as a need for food) or psychological (for example, the need to be accepted by others).

Although the difference is a subtle one, there is some benefit in distinguishing between needs and wants. A need is a basic deficiency given a particular essential item. You need food, water, air, security, and so forth. A want is placing certain personal criteria as to how that need must be fulfilled. Therefore, when we are hungry, we often have a specific food item in mind. Consequently, a teenager will lament to a frustrated parent that there is nothing to eat, standing in front of a full refrigerator. Most of marketing is in the want-fulfilling business, not the need-fulfilling business. Timex does not want you to buy just any watch, they want you to want a Timex brand watch. Likewise, Ralph Lauren wants you to want Polo when you shop for clothes. On the other hand, the American Cancer Association would like you to feel a need for a check-up and does not care which doctor you go to. In the end, however, marketing is mostly interested in creating and satisfying wants.

The decision process

Exhibit 10 outlines the process a consumer goes through in making a purchase decision. Each step is illustrated in the following sections of your text. Once the process is started, a potential buyer can withdraw at any stage of making the actual purchase. The tendency for a person to go through all six stages is likely only in certain buying situations—a first time purchase of a product, for instance, or when buying high priced, long-lasting, infrequently purchased articles. This is referred to as complex decision making .

For many products, the purchasing behavior is a routine affair in which the aroused need is satisfied in a habitual manner by repurchasing the same brand. That is, past reinforcement in learning experiences leads directly to buying, and thus the second and third stages are bypassed. This is called simple decision making . However, if something changes appreciably (price, product, availability, services), the buyer may re-enter the full decision process and consider alternative brands. Whether complex 0r simple, the first step is need identification. 1.

Need identification

Whether we act to resolve a particular problem depends upon two factors: (1) the magnitude of the discrepancy between what we have and what we need, and (2) the importance of the problem. A consumer may desire a new Cadillac and own a five-year-old Chevrolet. The discrepancy may be fairly large but relatively unimportant compared to the other problems he/she faces. Conversely, an individual may own a car that is two years old and running very well. Yet, for various reasons, he/she may consider it extremely important to purchase a car this year. People must resolve these types of conflicts before they can proceed. Otherwise, the buying process for a given product stops at this point, probably in frustration.

Once the problem is recognized it must be defined in such a way that the consumer can actually initiate the action that will bring about a relevant problem solution. Note that, in many cases, problem recognition and problem definition occur simultaneously, such as a consumer running out of toothpaste. Consider the more complicated problem involved with status and image–how we want others to see us. For example, you may know that you are not satisfied with your appearance, but you may not be able to define it any more precisely than that. Consumers will not know where to begin solving their problem until the problem is adequately defined.

Marketers can become involved in the need recognition stage in three ways. First they need to know what problems consumers are facing in order to develop a marketing mix to help solve these problems. This requires that they measure problem recognition. Second, on occasion, marketers want to activate problem recognition. Public service announcements espousing the dangers of cigarette smoking is an example. Weekend and night shop hours are a response of retailers to the consumer problem of limited weekday shopping opportunities. This problem has become particularly important to families with two working adults. Finally, marketers can also shape the definition of the need or problem. If a consumer needs a new coat, does he define the problem as a need for inexpensive covering, a way to stay warm on the coldest days, a garment that will last several years, warm cover that will not attract odd looks from his peers, or an article of clothing that will express his personal sense of style? A salesperson or an ad may shape his answers.

Information search and processing

After a need is recognized, the prospective consumer may seek information to help identify and evaluate alternative products, services, and outlets that will meet that need. Such information can come from family, friends, personal observation, or other sources, such as Consumer Reports , salespeople, or mass media. The promotional component of the marketers offering is aimed at providing information to assist the consumer in their problem solving process. In some cases, the consumer already has the needed information based on past purchasing and consumption experience. Bad experiences and lack of satisfaction can destroy repeat purchases. The consumer with a need for tires may look for information in the local newspaper or ask friends for recommendation. If he has bought tires before and was satisfied, he may go to the same dealer and buy the same brand.

Information search can also identify new needs. As a tire shopper looks for information, she may decide that the tires are not the real problem, that the need is for a new car. At this point, the perceived need may change triggering a new informational search.

Information search involves mental as well as the physical activities that consumers must perform in order to make decisions and accomplish desired goals in the marketplace. It takes time, energy, money, and can often involve foregoing more desirable activities. The benefits of information search, however, can outweigh the costs. For example, engaging in a thorough information search may save money, improve quality of selection, or reduce risks. As noted in the integrated marketing box, the Internet is a valuable information source.

Information processing

When the search actually occurs, what do people do with the information? How do they spot, understand, and recall information? In other words, how do they process information? This broad topic is important for understanding buyer behavior in general as well as effective communication with buyers in particular, and it has received a great deal of study. Assessing how a person processes information is not an easy task. Often observation has served as the basis. Yet there are many theories as to how the process takes place. One widely accepted theory proposes a five-step sequence. 2.

• Exposure . Information processing starts with the exposure of consumers to some source of stimulation such as watching television, going to the supermarket, or receiving direct mail advertisements at home. In order to start the process, marketers must attract consumers to the stimulus or put it squarely in the path of people in the target market.

• Attention . Exposure alone does little unless people pay attention to the stimulus. At any moment, people are bombarded by all sorts of stimuli, but they have a limited capacity to process this input. They must devote mental resources to stimuli in order to process them; in other words, they must pay attention. Marketers can increase the likelihood of attention by providing informational cues that are relevant to the buyer.

• Perception . Perception involves classifying the incoming signals into meaningful categories, forming patterns, and assigning names or images to them. Perception is the assignment of meaning to stimuli received through the senses. (More will be said about perception later.)

• Retention . Storage of information for later reference, or retention, is the fourth step of the information-processing sequence. Actually, the role of retention or memory in the sequence is twofold. First, memory holds information while it is being processed throughout the sequence. Second, memory stores information for future, long-term use. Heavy repetition and putting a message to music are two things marketers do to enhance retention.

• Retrieval and application . The process by which information is recovered from the memory storehouse is called retrieval . Application is putting that information into the right context. If the buyer can retrieve relevant information about a product, brand, or store, he or she will apply it to solve a problem or meet a need.

Variations in how each step is carried out in the information-processing sequence also occur. Especially influential is the degree of elaboration. Elaborate processing, also called central processing, involves active manipulation of information. A person engaged in elaborate processing pays close attention to a message and thinks about it; he or she develops thoughts in support of or counter to the information received. In contrast, nonelaborate, or peripheral, processing involves passive manipulation of information 3. It is demonstrated by most airline passengers while a flight attendant reads preflight safety procedures. This degree of elaboration closely parallels the low-involvement, high-involvement theory, and the same logic applies.

Identification and evaluation of alternatives

After information is secured and processed, alternative products, services, and outlets are identified as viable options. The consumer evaluates these alternatives, and, if financially and psychologically able, makes a choice. The criteria used in evaluation varies from consumer to consumer just as the needs and information sources vary. One consumer may consider price most important while another puts more weight upon quality or convenience.

The search for alternatives and the methods used in the search are influenced by such factors as: (a) time and money costs; (b) how much information the consumer already has; (c) the amount of the perceived risk if a wrong selection is made; and (d) the consumer's pre-disposition toward particular choices as influenced by the attitude of the individual toward choice behavior. That is, there are individuals who find the selection process to be difficult and disturbing. For these people there is a tendency to keep the number of alternatives to a minimum, even if they have not gone through an extensive information search to find that their alternatives appear to be the very best. On the other hand, there are individuals who feel it necessary to collect a long list of alternatives. This tendency can appreciably slow down the decision-making function.

Product/service/outlet selection

The selection of an alternative, in many cases ,will require additional evaluation. For example, a consumer may select a favorite brand and go to a convenient outlet to make a purchase. Upon arrival at the dealer, the consumer finds that the desired brand is out-of-stock. At this point, additional evaluation is needed to decide whether to wait until the product comes in, accept a substitute, or go to another outlet. The selection and evaluation phases of consumer problem solving are closely related and often run sequentially, with outlet selection influencing product evaluation, or product selection influencing outlet evaluation.

The purchase decision

After much searching and evaluating, or perhaps very little, consumers at some point have to decide whether they are going to buy. Anything marketers can do to simplify purchasing will be attractive to buyers. In their advertising marketers could suggest the best size for a particular use, or the right wine to drink with a particular food. Sometimes several decision situations can be combined and marketed as one package. For example, travel agents often package travel tours.

To do a better marketing job at this stage of the buying process, a seller needs to know answers to many questions about consumers' shopping behavior. For instance, how much effort is the consumer willing to spend in shopping for the product? What factors influence when the consumer will actually purchase? Are there any conditions that would prohibit or delay purchase? Providing basic product, price, and location information through labels, advertising, personal selling, and public relations is an obvious starting point. Product sampling, coupons, and rebates may also provide an extra incentive to buy.

Actually determining how a consumer goes through the decision-making process is a difficult research task. As indicated in the Newsline box, there are new research methods to better assess this behavior.

Postpurchase behavior

All the behavior determinants and the steps of the buying process up to this point are operative before or during the time a purchase is made. However, a consumer's feelings and evaluations after the sale are also significant to a marketer, because they can influence repeat sales and also influence what the customer tells others about the product or brand.

Keeping the customer happy is what marketing is all about. Nevertheless, consumers typically experience some postpurchase anxiety after all but the most routine and inexpensive purchases. This anxiety reflects a phenomenon called cognitive dissonance . According to this theory, people strive for consistency among their cognitions (knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, values). When there are inconsistencies, dissonance exists, which people will try to eliminate. In some cases, the consumer makes the decision to buy a particular brand already aware of dissonant elements. In other instances, dissonance is aroused by disturbing information that is received after the purchase 4. The marketer may take specific steps to reduce postpurchase dissonance. Advertising that stresses the many positive attributes or confirms the popularity of the product can be helpful. Providing personal reinforcement has proven effective with big-ticket items such as automobiles and major appliances. Salespeople in these areas may send cards or may even make personal calls in order to reassure customers about their purchase.

Capsule 8: Review

Influencing factors of consumer behavior

While the decision-making process appears quite standardized, no two people make a decision in exactly the same way. As individuals, we have inherited and learned a great many behavioral tendencies: some controllable, some beyond our control. Further, the ways in which all these factors interact with one another ensures uniqueness. Although it is impossible for a marketer to react to the particular profile of a single consumer, it is possible to identify factors that tend to influence most consumers in predictable ways.

The factors that influence the consumer problem-solving process are numerous and complex. For example, the needs of men and women are different in respect to cosmetics; the extent of information search for a low-income person would be much greater when considering a new automobile as opposed to a loaf of bread; a consumer with extensive past purchasing experience in a product category might well approach the problem differently from one with no experience. Such influences must be understood to draw realistic conclusions about consumer behavior.

For purpose of discussion, it may be helpful to group these various influences into related sets. Exhibit 11 provides such a framework. Situational, external, and internal influences are shown as having an impact on the consumer problem solving process. Situation influences include the consumer's immediate buying task, the market offerings that are available to the consumer, and demographic traits. Internal influences relate to the consumer's learning and socialization, motivation and personality, and lifestyle. External influences deal with factors outside the individual that have a strong bearing on personal behaviors. Current purchase behavior is shown as influencing future behavior through the internal influence of learning. Let us now turn to the nature and potential impact of each of these sets of influences on consumer problem solving. Exhibit 11 focuses on the specific elements that influence the consumer's decision to purchase and evaluate products and services.

Situational influences

Buying task

The nature of the buying task has considerable impact on a customer's approach to solving a particular problem. When a decision involves a low-cost item that is frequently purchased, such as bread, the buying process is typically quick and routinized. A decision concerning a new car is quite different. The extent to which a decision is considered complex or simple depends on (a) whether the decision is novel or routine, and on (b) the extent of the customers' involvement with the decision. A great deal of discussion has revolved around this issue of involvement. High-involvement decisions are those that are important to the buyer. Such decisions are closely tied to the consumer's ego and self-image. They also involve some risk to the consumer; financial risk (highly priced items), social risk (products important to the peer group), or psychological risk (the wrong decision might cause the consumer some concern and anxiety). In making these decisions, it is worth the time and energies to consider solution alternatives carefully. A complex process of decision making is therefore more likely for high involvement purchases. Low-involvement decisions are more straightforward, require little risk, are repetitive, and often lead to a habit: they are not very important to the consumer 5. Financial, social, and psychological risks are not nearly as great. In such cases, it may not be worth the consumer's time and effort to search for information about brands or to consider a wide range of alternatives. A low involvement purchase therefore generally entails a limited process of decision making. The purchase of a new computer is an example of high involvement, while the purchase of a hamburger is a low-involvement decision.

When a consumer has bought a similar product many times in the past, the decision making is likely to be simple, regardless of whether it is a high-or low-involvement decision. Suppose a consumer initially bought a product after much care and involvement, was satisfied, and continued to buy the product. The customer's careful consideration of the product and satisfaction has produced brand loyalty, which is the result of involvement with the product decision.

Once a customer is brand-loyal, a simple decision-making process is all that is required for subsequent purchases. The consumer now buys the product through habit, which means making a decision without the use of additional information or the evaluation of alternative choices.

Market offerings

Another relevant set of situational influences on consumer problem solving is the available market offerings. The more extensive the product and brand choices available to the consumer, the more complex the purchase decision process is likely to be.

For example, if you already have purchased or are considering purchasing a DVD (digital versatile disc), you know there are many brands to choose from—Sony, Samsung, Panasonic, Mitsubishi, Toshiba, and Sanyo, to name several. Each manufacturer sells several models that differ in terms of some of the following features–single or multiple event selection, remote control (wired or wireless), slow motion, stop action, variable-speed scan, tracking control, and so on. What criteria are important to you? Is purchasing a DVD an easy decision? If a consumer has a need that can be met by only one product or one outlet in the relevant market, the decision is relatively simple. Either purchase the product or let the need go unmet.

This is not ideal from the customer's perspective, but it can occur. For example, suppose you are a student on a campus in a small town many miles from another marketplace. Your campus and town has only one bookstore. You need a textbook for class; only one specific book will do and only one outlet has the book for sale. The limitation on alternative market offerings can clearly influence your purchase behavior.

As you saw in the DVD example, when the extent of market offerings increases, the complexity of the problem-solving process and the consumers' need for information also increases. A wider selection of market offerings is better from the customer's point of view, because it allows them to tailor their purchases to their specific needs. However, it may confuse and frustrate the consumer so that less-than-optimal choices are made.

Demographic influences

An important set of factors that should not be overlooked in attempting to understand and respond to consumers is demographics. Such variables as age, sex, income, education, marital status, and mobility can all have significant influence on consumer behavior. One study showed that age and education have strong relationships to store selection by female shoppers. This was particularly true for women's suits or dresses, linens and bedding, cosmetics, and women's sportswear.

DeBeers Limited, which has an 80 per cent share of the market for diamonds used in engagement rings, employed a consumer demographic profile in developing their promotional program. Their target market consists of single women and men between the ages of 18 and 24. They combined this profile with some lifestyle aspects to develop their promotional program.

People in different income brackets also tend to buy different types of products and different qualities. Thus various income groups often shop in very different ways. This means that income can be an important variable in defining the target group. Many designer clothing shops, for example, aim at higher-income shoppers, while a store like Kmart appeals to middle-and lower-income groups.

External influences

External factors are another important set of influences on consumer behavior. Among the many societal elements that can affect consumer problem solving are culture, social class, reference groups, and family.

A person's culture is represented by a large group of people with a similar heritage. The American culture, which is a subset of the Western culture, is of primary interest here. Traditional American culture values include hard work, thrift, achievement, security, and the like. Marketing strategies targeted to those with such a cultural heritage should show the product or service as reinforcing these traditional values. The three components of culture-beliefs, values, and customs-are each somewhat different. A belief is a proposition that reflects a person's particular knowledge and assessment of something (that is, "I believe that ..."). Values are general statements that guide behavior and influence beliefs. The function of a value system is to help a person choose between alternatives in everyday life.

Customs are overt modes of behavior that constitute culturally approved ways of behaving in specific situations. For example, taking one's mother out for dinner and buying her presents for Mother's Day is an American custom that Hallmark and other card companies support enthusiastically.

The American culture with its social values can be divided into various subcultures. For example, African-Americans constitute a significant American subculture in most US cities. A consumer's racial heritage can exert an influence on media usage and various other aspects of the purchase decision process.

Social class

Social class , which is determined by such factors as occupation, wealth, income, education, power, and prestige, is another societal factor that can affect consumer behavior. The best-known classification system includes upper-upper, lower-upper, upper-middle, lower-middle, upper-lower, and lower-lower class. Lower-middle and upper-lower classes comprise the mass market.

The upper-upper class and lower-upper class consist of people from wealthy families who are locally prominent. They tend to live in large homes furnished with art and antiques. They are the primary market for rare jewelry and designer originals, tending to shop at exclusive retailers. The upper-middle class is made up of professionals, managers, and business owners. They are ambitious, future-oriented people who have succeeded economically and now seek to enhance their quality of life. Material goods often take on major symbolic meaning for this group. They also tend to be very civic-minded and are involved in many worthy causes. The lower-middle class consists of mid-level white-collar workers. These are office workers, teachers, small business people and the like who typically hold strong American values. They are family-oriented, hard-working individuals. The upper-lower class is made up of blue-collar workers such as production line workers and service people. Many have incomes that exceed those of the lower-middle class, but their values are often very different. They tend to adopt a short-run, live-for-the-present philosophy. They are less future-oriented than the middle classes. The lower-lower class consists of unskilled workers with low incomes. They are more concerned with necessities than with status or fulfillment.

People in the same social class tend to have similar attitudes, live in similar neighborhoods, dress alike, and shop at the same type stores. If a marketer wishes to target efforts toward the upper classes, then the market offering must be designed to meet their expectations in terms of quality, service, and atmosphere. For example, differences in leisure concerts are favored by members of the middle and upper classes, while fishing, bowling, pool, and drive-in movies are more likely to involve members of the lower social classes.

Reference groups

Do you ever wonder why Pepsi used Shaquille O'Neal in their advertisements? The teen market consumes a considerable amount of soft drinks. Pepsi has made a strong effort to capture a larger share of this market, and felt that Shaquille represented the spirit of today's teens. Pepsi is promoted as "the choice of a new generation" and Shaquille is viewed as a role model by much of that generation. Pepsi has thus employed the concept of reference groups.

A reference group helps shape a person's attitudes and behaviors. Such groups can be either formal or informal. Churches, clubs, schools, notable individuals, and friends can all be reference groups for a particular consumer. Reference groups are characterized as having individuals who are opinion leaders for the group. Opinion leaders are people who influence others. They are not necessarily higher-income or better educated, but perhaps are seen as having greater expertise or knowledge related to some specific topic. For example, a local high school teacher may be an opinion leader for parents in selecting colleges for their children. These people set the trend and others conform to the expressed behavior. If a marketer can identify the opinion leaders for a group in the target market, then effort can be directed toward attracting these individuals. For example, if an ice cream parlor is attempting to attract the local high school trade, opinion leaders at the school may be very important to its success.

The reference group can influence an individual in several ways 6. :

• Role expectations: The role assumed by a person is nothing more than a prescribed way of behaving based on the situation and the person's position in the situation. Your reference group determines much about how this role is to be performed. As a student, you are expected to behave in a certain basic way under certain conditions.

• Conformity: Conformity is related to our roles in that we modify our behavior in order to coincide with group norms. Norms are behavioral expectations that are considered appropriate regardless of the position we hold.

• Group communications through opinion leaders: We, as consumers, are constantly seeking out the advice of knowledgeable friends or acquaintances who can provide information, give advice, or actually make the decision. For some product categories, there are professional opinion leaders who are quite easy to identify–e.g. auto mechanics, beauticians, stock brokers, and physicians.

One of the most important reference groups for an individual is the family. A consumer's family has a major impact on attitude and behavior. The interaction between husband and wife and the number and ages of children in the family can have a significant effect on buying behavior.

One facet in understanding the family's impact on consumer behavior is identifying the decision maker for the purchase in question. In some cases, the husband is dominant, in others the wife or children, and still others, a joint decision is made. The store choice for food and household items is most often the wife's. With purchases that involve a larger sum of money, such as a refrigerator, a joint decision is usually made. The decision on clothing purchases for teenagers may be greatly influenced by the teenagers themselves. Thus, marketers need to identify the key family decision maker for the product or service in question.

Another aspect of understanding the impact of the family on buying behavior is the family lifecycle . Most families pass through an orderly sequence of stages. These stages can be defined by a combination of factors such as age, marital status,and parenthood. The typical stages are:

• The bachelor state; young, single people.

• Newly married couples; young, no children.

• The full nest I and II; young married couples with dependent children:

• Youngest child under six (Full nest I)

• Youngest child over six (Full nest II)

• The full nest III; older married couples with dependent children.

• The empty nest I and II; older married couples with no children living with them:

• Adults in labor force (Empty nest I)

• Adults retired (Empty nest II)

• The solitary survivors; older single people:

• In labor force

• Retired