- International MBA

- MBA with Project Management

- MBA with Healthcare Management

- MBA with Supply Chain Management

- MBA with Hospitality Management

- MSc Management

- MSc Management with Marketing

- MSc Management with HR

- MSc Management with Finance

- BSC (HONS) ADULT NURSING (BLENDED) – NORTH OF ENGLAND

- BSC (HONS) ADULT NURSING (BLENDED) – LONDON

- MSc Computer Science

- MSc Computer Science with Data Science

- MSc Computer Science with Cyber Security

- LLM Master of Laws

- LLM Commercial Law

- LLM International Law

- BSc (Hons) Nursing Studies Top-Up

- MSc Nursing Studies

- On-campus courses

- Start Application

- Start dates

- Admission requirements

- Complete your application

The impact of health inequalities in the UK

Health inequalities have impacted people across the UK for many years, but the conversation around health inequalities has grown louder over the last year, as the impact of coronavirus hit some groups of people harder than others.

One of the core principles in the Constitution of the World Health Organization is that good health is a basic human right. This principle also featured in the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Article 25) in 1948, which states ‘Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and wellbeing of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical, and the necessary social service’.

However, despite the declaration, health inequalities continue to affect many people in today’s society.

What are health inequalities?

NHS England defines health inequalities as ‘unfair and avoidable differences in health across the population, and between different groups within society’. These inequalities arise due to the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age, and influence opportunities for good health, and how people think, feel and act, which shapes mental health, physical health and wellbeing.

Health inequalities can manifest in a number of ways – life expectancy, avoidable mortality, long-term health conditions, and the prevalence of mental ill-health.

What causes health inequalities?

There are multiple factors which influence health and wellbeing , including, but not limited to, social factors, cultural factors, political factors, economic factors, commercial factors, and environmental factors. These factors don’t operate in isolation, more they are interwoven in a reinforcing way into the fabric of some people’s lives.

Disparities in access to education, employment status and income level all contribute to health inequalities, especially as research has shown a link between income and good or poor health levels. As outlined by The Health Foundation , people in the bottom 40% of income distribution in the UK are almost twice as likely to report poor health than those in the top 20%. Poor health is particularly prevalent amongst people who are in persistent poverty – those who do not have access to basic goods or services such as being able to heat the home or the availability of healthy food.

Poor health and lower income are two circumstances which cause further negative outcomes when displayed in tandem – lower income is associated with higher stress levels which can harm both mental and physical health, therefore limiting the opportunity for good and stable employment which affects income.

One cause of low income and insecure employment may be the lack of access to quality education in childhood and continued lifelong learning throughout adulthood. The Office for National Statistics found that people who have a lower life expectancy are three times more likely to have no qualifications compared to people with the highest life expectancies.

Being socially connected to friends, family and communities also impacts health. Those with healthy connections are more likely to live longer and healthier lives, and will experience less physical and mental health problems than those without social ties. The impact of loneliness on mental health is a topic which has long been discussed, but the impact of loneliness on physical health has also been reinforced by research. It has been found that social isolation and loneliness are associated with a 30% increased risk of heart disease and stroke .

Housing and the surroundings in which people live can also have an affect on health inequalities. These are two factors which have an impact on people in childhood, therefore paving the path for the rest of their lives. Being close to green space and places to play enables the opportunity to be physically active and socially connected, yet children in deprived areas are nine times less likely to have access to these . Having a warm, comfortable and stable home also encourages children to flourish, yet children who live in cold homes are more than twice as likely to suffer respiratory problems than children living in warm homes .

With health inequalities across the UK impacting the physical and mental health of many people, it is no surprise that these then feed into the wider issue of the disparity in life expectancy across the country.

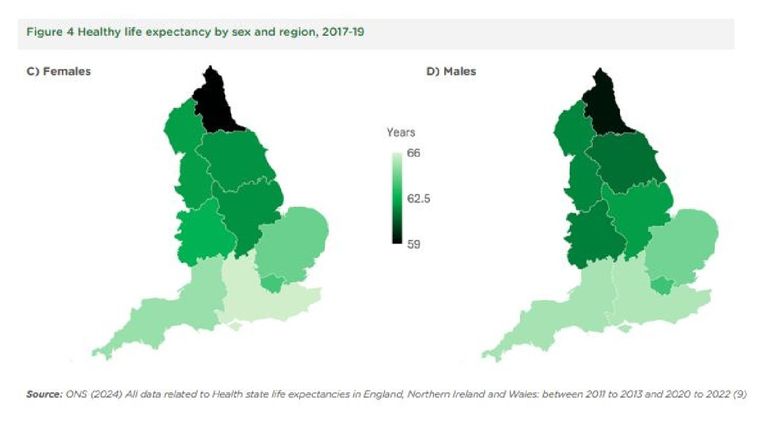

By analysing data sets outlined by the Office for National Statistics, The Health Foundation mapped average incomes against average male healthy life expectancy at birth in areas in England. None of the areas in the north of England surpassed the above average net annual income after housing costs for the country, and the starkest observation of all is the contrast between the area with the lowest life expectancy and the area with the highest annual income. Manchester had the lowest life expectancy of 55.75 years and the third lowest average income of £19,833.05, compared to the City of London which had the second highest life expectancy of 70.85 and the highest annual income of £52,000.

Further research has also uncovered that a baby girl born in Richmond on Thames is expected to live 17.8 more years in good health than a baby girl born in Manchester.

The cases for remedying health inequalities

There are moral, social and economic cases to be made for treating the causes that create health inequalities in the UK.

The moral case relates to the importance of people having what they need to do the things they wish to do, to participate in society, and to live a good quality of life. This is reflected in the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights outlined previously, and also by economist and philosopher Amartya Sen who, in the 1980s, made the case that health and wellbeing is a resource for living, and is a matter of social equity and justice.

Socially, good health is important for positive family and community life. If a family member is in good health, they are more able to build foundations that support other family members to thrive and are able to provide emotional support, and can create strong connections within friends, family and community, thereby reducing the physical and mental health impacts of poor health both within the individual and throughout those connections.

When a person has a job that pays enough to live on, financial security and reduction of stress can positively impact wellbeing and mental and physical health. As well as this, an employee’s health is also beneficial to employers, businesses and the economy more broadly as a healthy working-age population can lead to economic prosperity by being more engaged and productive, and can also enable continued work as they get older rather than poor health causing early retirements.

Learn more about health inequalities

Though access to quality healthcare isn’t the sole solution for health inequalities in the UK, the NHS Long Term Plan aims to reduce these inequalities by taking a more systematic approach to addressing many variables in care provision.

They aim to do this by targeting a higher share of funding towards geographies with higher health inequalities, support local planning and national programmes to reduce inequalities, implement an enhanced continuity of care model in maternity services to improve outcomes for the most vulnerable mothers and babies, increase the number of people receiving physical health checks, do more to ensure healthier, longer lives for people with a learning disability, and much more.

Those working in the NHS and in healthcare provisions have a crucial opportunity to create change, and be part of a better, longer, and healthier future for many people across the country.

To learn more about health inequalities, and to see how you can be part of positive change, our MSc Nursing Studies will equip you for transformational leadership positions in senior nursing, midwifery and healthcare roles.

Study flexibly with our online nursing master’s degree, and continue to work as you fit your learning around your life and career.

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- News & Views

- Health equity in...

Health equity in England: the Marmot review 10 years on

Linked news.

Marmot 10 years on: austerity has damaged nation’s health, say experts

- Related content

- Peer review

- Michael Marmot , director

- Institute of Health Equity, Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, UCL, London

- m.marmot{at}ucl.ac.uk

Ten years after the landmark review on health inequalities in England, coauthor Michael Marmot says the situation has become worse

Britain has lost a decade. And it shows. Health, as measured by life expectancy, has stopped improving, and health inequalities are growing wider. Improvement in life expectancy, from the end of the 19th century on, started slowing dramatically in 2011. Now in parts of England, particularly among women in deprived communities and the north, life expectancy has fallen, and the years people spend in poor health might even be increasing—a shocking development. In the UK, as in other countries, we are used to health improving year on year. Bad as health is in England, the damage to the health of people in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland has been worse.

Put simply, if health has stopped improving, then society has stopped improving. Evidence, assembled globally, shows that health is a good measure of social and economic progress. When a society is flourishing, health tends to flourish. When a society has large social and economic inequalities, it also has large inequalities in health. 1 The health of the population is not just a matter of how well the health service is funded and functions, important as that is, but also the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age, and inequities in power, money, and resources. Taken together, these are the social determinants of health. 2

This damage to the nation’s health need not have happened. In 2010, both the Labour government and the Conservative-led coalition government that followed it were concerned that health inequalities in England were too wide and that action was needed to reduce them. To inform that action the government in 2008 commissioned me to review what it and wider society could do to reduce health inequalities. Colleagues and I at what later became the UCL Institute of Health Equity convened nine task groups of more than 80 experts to review the evidence and assembled a distinguished commission to deliberate on that evidence. The result was the Marmot review, Fair Society Healthy Lives, published in 2010. 3 The review was commissioned by the Labour government and welcomed by the coalition government in a public health white paper.

The Marmot review laid out how public expenditure on policies, through the life course, could act on the social determinants of health to reduce health inequalities. It might have been welcomed in theory, but in reality, under the banner of austerity, public expenditure was cut from 42% of national income in 2009-10 to 35% in 2018-19

In a new report, Health Equity in England: the Marmot Review 10 Years On , 4 we show that austerity has taken its toll in almost all of the areas identified by the Marmot review as important for health inequalities. Child poverty has increased. Children’s centres have closed. Funding for education is down. There is a housing crisis and a rise in homelessness. Growing numbers of people have insufficient money to lead a healthy life and now resort to food banks. There are more left-behind communities living in poor conditions with little reason for hope.

Given the strength of the evidence on social determinants of health inequalities, this rolling back of the state is likely to have had an adverse effect on health and health inequalities. I cannot say with any certainty which of the changes associated with austerity were responsible for the increase in health inequalities and which might cause damage in the future, but the figures show adverse impact across the whole range of domains in the Marmot review on the lives that people are able to lead.

Growing inequalities according to region and deprivation

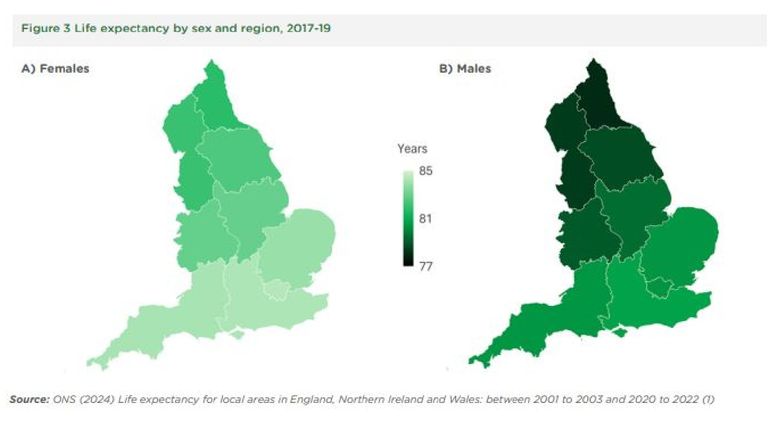

The flattening of the upward curve of life expectancy is marked. From 1981 to 2010 life expectancy increased by about one year every five and a half years among women and every four years among men. From 2011 to 2018 this slowed to one year every 28 years among women and every 15 years among men.

This slowing down is real. But the explanations have been disputed. I claim, based on a general view of health trends globally, that if health stopped improving, then society must have stopped improving. We have considered and can reject more prosaic explanations. First: perhaps we’ve reached peak life expectancy. It has to slow some time. Plausible, but other European countries with longer life expectancies than England or other countries of the UK have continued to increase. We have a way to go before we hit peak. Second, perhaps we had bad winters and bad flu outbreaks. Mortality goes up in a bad winter. Analyses that we did for the new report showed that improvements in mortality slowed in non-winter months, as it did in winter months. At most, winter effects could account for between one sixth and one eighth of the slowing down in improvement.

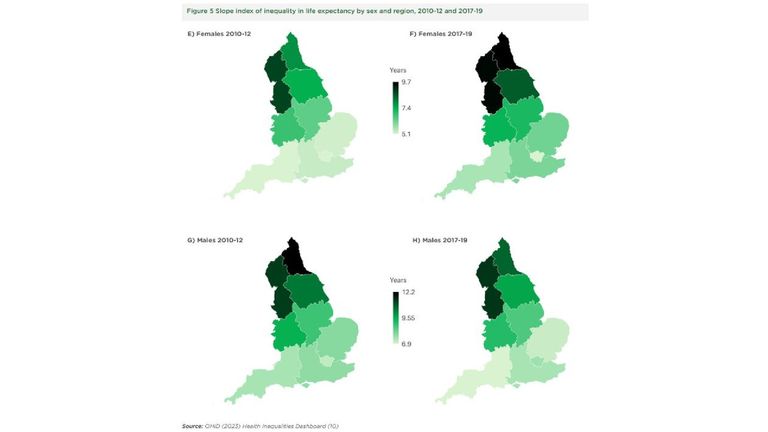

The growing inequalities in health according to deprivation and region support my contention that the real causes of the failure of health to improve are social. The relation between deprivation and health is graded. Classifying areas of the country by the index of multiple deprivation reveals a strong and consistent gradient: the more deprived the area, the lower the life expectancy. In 2016-18, men in the least deprived 10% of England had life expectancy 9.5 years longer than men in the most deprived; for women the gap was 7.7 years ( fig 1 ). Earlier, in 2010-12, the gap was 9.1 years for men and 6.8 years for women. Among women in the most deprived 20% of areas there was no improvement at all, in sharp contrast to the continued improvement for the most fortunate 20%.

Life expectancy at birth by area deprivation deciles and sex, England, 2016–18. Based on data from Public Health England, 2020. 5

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

There are well known regional differences in mortality and life expectancy—people in the north of England are sicker, for example. Deprivation and geography come together in important ways. For people living in in the least deprived 10% of districts, there is little regional difference in life expectancy. If you are among the most fortunate 10% it doesn’t much matter in which region of the country you live in, your demographic subgroup will have experienced improvement in life expectancy. The more deprived your district the greater the disadvantage of living in the north compared with London and the south east. Particularly for women, life expectancy in the most deprived 10% declined in the north east, Yorkshire and Humberside, and other areas outside London and the north west.

Life expectancy is used as an indicator, but health is more than the expectation of length of life. The social gradient in healthy life expectancy is steeper than that of life expectancy. And years spent in poor health increased between 2009-11 and 2015-17: from 15.8 years to 16.2 in men and from 18.7 years to 19.4 years in women.

Cutting back the role of the state

The governments elected in Britain in 2010 and 2015 had austerity as a central plank of policy. The stated aim was to restore the economy to growth by restricting public expenditure. By one measure, at least, it didn’t work: wage growth. International comparisons of wage growth between 2007 and 2018 show that Britain, with minus 2%, was the third worst of 35 rich (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries, only better than Mexico and Greece. 6

If pushed, the governments would probably have denied that the purpose of policy was to make the poor poorer and allow the top 1% to resume the trajectory—briefly interrupted by the global financial crisis—of garnering a larger share of national income and wealth. But that was its effect. Changes to taxes and benefits introduced in 2015 were neatly regressive, leading to those with lower incomes experiencing a greater reduction in income. 7 Cuts to services and to local government hit more deprived areas and families hardest.

It is hardly surprising that ill effects should result from a 40% cut in spending on welfare for families; a 31% cut to local government expenditure in the most deprived 10%, compared with 16% in the least deprived 10%; and funding for sixth form and further education falling by 12% per pupil. 8 If the architects of these policies imagined that all that money had been going to waste, the evidence indicates that they were mistaken—our new report documents substantial harmful effects.

Which of these might be most responsible for an increase in health inequalities is difficult to say because they are inter-related. In the 10 Years On report we examine impacts in five of the six domains of recommendations made in the Marmot review: give every child the best start in life; ensure access to education and lifelong learning; improve employment and working conditions; ensure people have enough money to lead a healthy life; promote sustainable places and communities.

Early childhood and housing

Investing in early childhood creates hope for the future. Adverse trends over the past decade do not explain the health trends of the past decade but might be a harbinger of things to come. Early childhood is crucial; not just for health, but development—cognitive, linguistic, social, emotional, and behavioural skills. Good early child development predicts good school performance, which in turn predicts better educational and occupational opportunities and more salutary living conditions in adulthood. Conversely, adverse childhood experiences cast a long shadow, predicting mental and physical illness in later life.

More generally, both the good and bad things that happen in early childhood influence individuals’ abilities through life. We emphasise the importance of agency—having control over one’s life—as central to health and health inequalities. Agency starts with good early child development and protection from adverse childhood experiences. It continues with having enough resources in adulthood to lead a life that one has reason to value. Having insufficient money to pay rent or feed children is deeply disempowering.

Early childhood contributes to health inequalities in adult life because of the social gradient. Good early child development is less common as deprivation increases and adverse child experiences are more common. Thus, approaches to reducing inequalities in health must include improving services that break the link between deprivation and poor outcomes for children and reducing deprivation in childhood. The signs are not good. It has been estimated that, as a result of cuts to local government, 1000 Sure Start children’s centres have had to close. 9 The welcome support for childcare for older pre-school children does not make up for these closures.

A much used measure of child poverty is the proportion of children living in households with less than 60% of the median income. In 2009-12, child poverty was 18%, rising to 20% in 2015-18. But the cost of housing can drive people into poverty. After housing costs are taken into account, child poverty rose from 28% in 2009-12 to 31% in 2015-18.

Shortage of housing contributes to increased costs. The proportion of people paying more than a third of their income on housing costs unsurprisingly follows the social gradient, but has risen in all income groups. In the lowest 10% of income in 2016-7, 38% of families were paying more than a third of their income on housing, up from 28% a decade earlier.

Time for action

In the Marmot review in 2010, we wrote “Health inequalities are not inevitable and can be significantly reduced. They stem from avoidable inequalities in society.”

A report from the Royal Society for Public Health said that we got the evidence and approach more or less right. The society surveyed its members and a panel of experts on their views on the major UK public health achievements of the 21st century to date. The top three were the smoking ban, the sugar levy, and the Marmot review. 10

Unfortunately, as we point out in the report, there are no routine figures produced for life expectancy based on race or ethnicity. The figures that we do have point to half of minority ethnic groups—mostly black, Asian, and mixed—having significantly lower disability free life expectancy than white British men and women.

We have now laid out a new set of recommendations following the intellectual framework of the Marmot review. It is our firm view that such recommendations are vital to creating a society that is just and sustainable for current and future generations.

Michael Marmot is professor of epidemiology and public health and director of the Institute of Health Equity at UCL. He has chaired various major reviews of the social determinants of health, including the 2010 Marmot review of health inequalities in England published as Fair Society Healthy Lives .

Acknowledgments

The authors of this 10 Years On report were, in addition to MM, Jessica Allen, Peter Goldblatt, Tammy Boyce, and Joana Morrison, the first four of whom were authors with MM of the original Marmot review in 2010. This 10 Years On report was supported by the Health Foundation, who provided important comments on the work as it proceeded.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and have no relevant interests to declare.

- Commission on the Social Determinants of Health

- ↵ Institute of Health Equity. Health equity in England: the Marmot review 10 years on. London; 2020. http://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/the-marmot-review-10-years-on .

- ↵ Public Health England. Public health outcomes framework. https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/public-health-outcomes-framework/data#page/9/gid/1000049/pat/15/par/E92000001/ati/6/are/E12000004/iid/90366/age/1/sex/1

- ↵ Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Average wages (indicator). 2019. https://data.oecd.org/earnwage/average-wages.htm .

- Britton J ,

- Farquharson C ,

- ↵ Royal Society for Public Health. Top 20 UK public health achievements of the 21st century. 23 December 2019. https://www.rsph.org.uk/about-us/news/top-20-public-health-achievements-of-the-21st-century.html .

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 74, Issue 11

- The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1294-6851 Clare Bambra 1 ,

- Ryan Riordan 2 ,

- John Ford 2 ,

- Fiona Matthews 1

- 1 Population Health Sciences Institute, Newcastle University Institute for Health and Society , Newcastle upon Tyne , UK

- 2 School of Clinical Medicine, Cambridge University , Cambridge , UK

- Correspondence to Clare Bambra, Population Health Sciences Institute, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 4LP, UK; clare.bambra{at}newcastle.ac.uk

This essay examines the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for health inequalities. It outlines historical and contemporary evidence of inequalities in pandemics—drawing on international research into the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918, the H1N1 outbreak of 2009 and the emerging international estimates of socio-economic, ethnic and geographical inequalities in COVID-19 infection and mortality rates. It then examines how these inequalities in COVID-19 are related to existing inequalities in chronic diseases and the social determinants of health, arguing that we are experiencing a syndemic pandemic . It then explores the potential consequences for health inequalities of the lockdown measures implemented internationally as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic, focusing on the likely unequal impacts of the economic crisis. The essay concludes by reflecting on the longer-term public health policy responses needed to ensure that the COVID-19 pandemic does not increase health inequalities for future generations.

- DEPRIVATION

- Health inequalities

This article is made freely available for use in accordance with BMJ's website terms and conditions for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic or until otherwise determined by BMJ. You may use, download and print the article for any lawful, non-commercial purpose (including text and data mining) provided that all copyright notices and trade marks are retained.

https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2020-214401

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

INTRODUCTION

In 1931, Edgar Sydenstricker outlined inequalities by socio-economic class in the 1918 Spanish influenza epidemic in America, reporting a significantly higher incidence among the working classes. 1 This challenged the widely held popular and scientific consensus of the time which held that ‘the flu hit the rich and the poor alike’. 2 In the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been similar claims made by politicians and the media - that we are ‘all in it together’ and that the COVID-19 virus ‘does not discriminate’. 3 This essay aims to dispel this myth of COVID-19 as a socially neutral disease, by discussing how, just as 100 years ago, there are inequalities in COVID-19 morbidity and mortality rates—reflecting existing unequal experiences of chronic diseases and the social determinants of health. The essay is structured in three main parts. Part 1 examines historical and contemporary evidence of inequalities in pandemics—drawing on international research into the Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918, the H1N1 outbreak of 2009 and the emerging international estimates of socio-economic, ethnic and geographical inequalities in COVID-19 infection and mortality rates. Part 2 examines how these inequalities in COVID-19 are related to existing inequalities in chronic diseases and the social determinants of health, arguing that we are experiencing a syndemic pandemic . In Part 3, we explore the potential consequences for health inequalities of the lockdown measures implemented internationally as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic, focusing on the likely unequal impacts of the economic crisis. The essay concludes by reflecting on the longer-term public health policy responses needed to ensure that the COVID-19 pandemic does not increase health inequalities for future generations.

PART 1. HISTORICAL AND CONTEMPORARY EVIDENCE OF INEQUALITIES IN PANDEMICS

More recent studies have confirmed Sydenstricker’s early findings: there were significant inequalities in the 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic. The international literature demonstrates that there were inequalities in prevalence and mortality rates: between high-income and low-income countries, more and less affluent neighbourhoods, higher and lower socio-economic groups, and urban and rural areas. For example, India had a mortality rate 40 times higher than Denmark and the mortality rate was 20 times higher in some South American countries than in Europe. 4 In Norway, mortality rates were highest among the working-class districts of Oslo 5 ; in the USA, they were highest among the unemployed and the urban poor in Chicago, 6 and across Sweden, there were inequalities in mortality between the highest and lowest occupational classes—particularly among men. 7 In contrast, countries with smaller pre-existing social and economic inequalities, such as New Zealand, did not experience any socio-economic inequalities in mortality. 8 9 An urban–rural effect was also observed in the 1918 influenza pandemic whereby, for example, in England and Wales, the mortality was 30%–40% higher in urban areas. 10 There is also some evidence from the USA that the pandemic had long-term impacts on inequalities in child health and development. 11

Several studies have also demonstrated inequalities in the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic. For example, globally, Mexico experienced a higher mortality rate than that in higher-income countries. 12 In terms of socio-economic inequalities, themortality rate from H1N1 in the most deprived neighbourhoods of England was three times higher than in the least deprived. 13 It was also higher in urban compared to rural areas. 13 Similarly, a Canadian study in Ontario found that hospitalisation rates for H1N1 were associated with lower educational attainment and living in a high deprivation neighbourhood. 14 Another study found positive associations between people with financial issues (eg, financial barriers to healthcare access) and influenza-like illnesses during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic in the USA. 15 Various studies on cyclical winter influenza in North America have also found associations between mortality, morbidity and symptom severity and socio-economic status among adults and children. 16 17

Just as in 1918 and 2009, evidence of social inequalities is already emerging in relation to COVID-19 from Spain, the USA and the UK. Intermediate data published by the Catalonian government in Spain suggest that the rate of COVID-19 infection is six or seven times higher in the most deprived areas of the region compared to the least deprived. 18 Similarly, in preliminary USA analysis, Chen and Krieger (2020) found area-level socio-spatial gradients in confirmed cases in Illinois and positive test results in New York City, with dramatically increased risk of death observed among residents of the most disadvantaged counties. 19 With regard to ethnic inequalities in COVID-19, data from England and Wales have found that people who are black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) accounted for 34.5% of 4873 critically ill COVID-19 patients (in the period ending April 16, 2020) and much higher than the 11.5% seen for viral pneumonia between 2017 and 2019. 20 Only 14% of the population of England and Wales are from BAME backgrounds. Even more stark is the data on racial inequalities in COVID-19 infections and deaths that are being released by various states and municipalities in the USA. For example, in Chicago (in the period ending April 17, 2020), 59.2% of COVID-19 deaths were among black residents and the COVID-19 mortality rate for black Chicagoans was 34.8 per 100 000 population compared to 8.2 per 100 000 population among white residents. 21 There will likely be an interaction of race and socio-economic inequalities, demonstrating the intersectionality of multiple aspects of disadvantage coalescing to further compound illness and increase the risk of mortality. 22

PART 2. THE SYNDEMIC OF COVID-19, CHRONIC DISEASE AND THE SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH

The COVID-19 pandemic is occurring against a backdrop of social and economic inequalities in existing non-communicable diseases (NCDs) as well as inequalities in the social determinants of health. Inequalities in COVID-19 infection and mortality rates are therefore arising as a result of a syndemic of COVID-19, inequalities in chronic diseases and the social determinants of health. The prevalence and severity of the COVID-19 pandemic is magnified because of the pre-existing epidemics of chronic disease—which are themselves socially patterned and associated with the social determinants of health. The concept of a syndemic was originally developed by Merrill Singer to help understand the relationships between HIV/AIDS, substance use and violence in the USA in the 1990s. 23 A syndemic exists when risk factors or comorbidities are intertwined, interactive and cumulative—adversely exacerbating the disease burden and additively increasing its negative effects: ‘A syndemic is a set of closely intertwined and mutual enhancing health problems that significantly affect the overall health status of a population within the context of a perpetuating configuration of noxious social conditions’ [24 p13]. We argue that for the most disadvantaged communities, COVID-19 is experienced as a syndemic—a co-occurring, synergistic pandemic that interacts with and exacerbates their existing NCDs and social conditions ( figure 1 ).

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

The syndemic of COVID-19, non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and the social determinants of health (adapted from Singer 23 and Dahlgren and Whitehead 25 ).

Minority ethnic groups, people living in areas of higher socio-economic deprivation, those in poverty and other marginalised groups (such as homeless people, prisoners and street-based sex workers) generally have a greater number of coexisting NCDs, which are more severe and experienced at at a younger age. For example, people living in more socio-economically disadvantaged neighbourhoods and minority ethnic groups have higher rates of almost all of the known underlying clinical risk factors that increase the severity and mortality of COVID-19, including hypertension, diabetes, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), heart disease, liver disease, renal disease, cancer, cardiovascular disease, obesity and smoking. 26–29 Likewise, minority ethnic groups in Europe, the USA and other high-income countries experience higher rates of the key COVID-19 risk factors, including coronary heart disease and diabetes. 28 Similarly, the Gypsy/Roma community—one of the most marginalised minority groups in Europe—has a smoking rate that is two to three times the European average and increased rates of respiratory diseases (such as COPD) and other COVID-19 risk factors. 29

These inequalities in chronic conditions arise as a result of inequalities in exposure to the social determinants of health: the conditions in which people ‘live, work, grow and age’ including working conditions, unemployment, access to essential goods and services (eg, water, sanitation and food), housing and access to healthcare. 25 30 By way of example, there are considerable occupational inequalities in exposure to adverse working conditions (eg, ergonomic hazards, repetitive work, long hours, shift work, low wages, job insecurity)—they are concentrated in lower-skill jobs. These working conditions are associated with increased risks of respiratory diseases, certain cancers, musculoskeletal disease, hypertension, stress and anxiety. 31 In addition to these long-term exposures, inequalities in working conditions may well be impacting the unequal distribution of the COVID-19 disease burden. For example, lower-paid workers (where BAME groups are disproportionately represented)—particularly in the service sector (eg, food, cleaning or delivery services)—are much more likely to be designated as key workers and thereby are still required to go to work and rely on public transport for doing so. All these increase their exposure to the virus.

Similarly, access to healthcare is lower in disadvantaged and marginalised communities—even in universal healthcare systems. 32 In England, the number of patients per general practitioner is 15% higher in the most deprived areas than that in the least deprived areas. 33 Medical care is even more unequally distributed in countries such as the USA where around 33 million Americans—from the most disadvantaged and marginalised groups—have insufficient or no healthcare insurance. 27 This reduced access to healthcare—before and during the outbreak—contributes to inequalities in chronic disease and is also likely to lead to worse outcomes from COVID-19 in more disadvantaged areas and marginalised communities. People with existing chronic conditions (eg, cancer or cardiovascular disease (CVD)) are less likely to receive treatment and diagnosis as health services are overwhelmed by dealing with the pandemic.

Housing is also an important factor in driving health inequalities. 34 For example, exposure to poor quality housing is associated with certain health outcomes, for example, damp housing can lead to respiratory diseases such as asthma while overcrowding can result in higher infection rates and increased risk of injury from household accidents. 34 Housing also impacts health inequalities materially through costs (eg, as a result of high rents) and psychosocially through insecurity (eg, short-term leases). 34 Lower socio-economic groups have a higher exposure to poor quality or unaffordable, insecure housing and therefore have a higher rate of negative health consequences. 35 These inequalities in housing conditions may also be contributing to inequalities in COVID-19. For example, deprived neighbourhoods are more likely to contain houses of multiple occupation and smaller houses with a lack of outside space, as well as have higher population densities (particularly in deprived urban areas) and lower access to communal green space. 27 These will likely increase COVID-19 transmission rates—as was the case with H1N1 where strong associations were found with urbanity. 13

The social determinants of health also work to make people from marginalised communities more vulnerable to infection from COVID-19—even when they have no underlying health conditions. Decades of research into the psychosocial determinants of health have found that the chronic stress of material and psychological deprivation is associated with immunosuppression. 36 Psychosocial feelings of subordination or inferiority as a result of occupying a low position on the social hierarchy stimulate physiological stress responses (eg, raised cortisol levels), which, when prolonged (chronic), can have long-term adverse consequences for physical and mental health. 37 By way of example, studies have found consistent associations between low job status (eg, low control and high demands), stress-related morbidity and various chronic conditions including coronary heart disease, hypertension, obesity, musculoskeletal conditions, and psychological ill health. 38 Likewise, there is increasing evidence that living in disadvantaged environments may produce a sense of powerlessness and collective threat among residents, leading to chronic stressors that, in time, damage health. 39 Studies have also confirmed that adverse psychosocial circumstances increase susceptibility—influencing the onset, course and outcome of infectious diseases—including respiratory diseases like COVID-19. 40

PART 3. THE GREAT LOCKDOWN: THE COVID-19 ECONOMIC CRISIS AND HEALTH INEQUALITIES

The impact of COVID-19 on health inequalities will not just be in terms of virus-related infection and mortality, but also in terms of the health consequences of the policy responses undertaken in most countries. While traditional public health surveillance measures of contact tracing and individual quarantine were successfully pursued by some countries (most notably by South Korea and Germany) as a way of tackling the virus in the early stages, most other countries failed to do so, and governments worldwide were eventually forced to implement mass quarantine measures—in the form of lockdowns. These state-imposed restrictions—usually requiring the government to take on emergency powers—have been implemented to varying levels of severity, but all have in common a significant increase in social isolation and confinement within the home and immediate neighbourhood. The aims of these unprecedented measures are to increase social and physical distancing and thereby reduce the effective reproduction number (eR0) of the virus to less than 1. For example, in the UK, individuals were only allowed to leave the home for one of four reasons (shopping for basic necessities, exercise, medical needs, travelling for work purposes). Following Wuhan province in China, most of the lockdowns have been implemented for 8 to 12 weeks.

The immediate pathways through which the COVID-19 emergency lockdowns are likely to have unequal health impacts are multiple—ranging from unequal experiences of lockdown (eg, due to job and income loss, overcrowding, urbanity, access to green space, key worker roles), how the lockdown itself is shaping the social determinants of health (eg, reduced access to healthcare services for non-COVID-19 reasons as the system is overwhelmed by the pandemic) and inequalities in the immediate health impacts of the lockdown (eg, in mental health and gender-based violence). However, arguably, the longer-term and largest consequences of the ‘great lockdown’ for health inequalities will be through political and economic pathways ( figure 1 ). The world economy has been severely impacted by COVID-19—with almost daily record stock market falls, oil prices have crashed and there are record levels of unemployment (eg, 5.2 million people filed for unemployment benefit in just 1 week in April 2020 in the USA), despite the unprecedented interventionist measures undertaken by some governments and central banks—such as the £300 billion injection by the UK government to support workers and businesses. The pandemic has slowed China’s economy with a predicted loss of $65 billion as a minimum in the first quarter of 2020. Economists fear that the economic impact will be far greater than the financial crisis of 2007/2008, and they say that it is likely to be worse in depth than the Great Depression of the 1930s. Just like the 1918 influenza pandemic (which had severe impacts on economic performance and increased poverty rates), the COVID-19 crisis will have huge economic, social and—ultimately—health consequences.

Previous research has found that sudden economic shocks (like the collapse of communism in the early 1990s and the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2008 41 ) lead to increases in morbidity, mental ill health, suicide and death from alcohol and substance use. For example, following the GFC, worldwide an excess of suicides were observed in the USA, England, Spain and Ireland. 42 There is also evidence of other increases in poor mental health after the GFC including self-harm and psychiatric morbidity. 41 42 These health impacts were not shared equally though—areas of the UK with higher unemployment rates had greater increases in suicide rates and inequalities in mental health increased with people living in the most deprived areas experiencing the largest increases in psychiatric morbidity and self-harm. 43 Further, unemployment (and its well-established negative health impacts in terms of morbidity and mortality 38 ) is disproportionately experienced by those with lower skills or who live in less buoyant local labour markets. 27 So, the health consequences of the COVID-19 economic crisis are likely to be similarly unequally distributed—exacerbating heath inequalities.

However, the effects of recessions on health inequalities also vary by public policy response with countries such as the UK, Greece, Italy and Spain who imposed austerity (significant cuts in health and social protection budgets) after the GFC experiencing worse population health effects than those countries such as Germany, Iceland and Sweden who opted to maintain public spending and social safety nets. 41 Indeed, research has found that countries with higher rates of social protection (such as Sweden) did not experience increases in health inequalities during the 1990s economic recession. 44 Similarly, old-age pensions in the UK were protected from austerity cuts after the GFC and research has suggested that this prevented health inequalities increasing amongst the older population. 45 These findings are in keeping with previous studies of the effects of public sector and welfare state contractions and expansions on trends in health inequalities in the UK, USA and New Zealand. 27 46–49 For example, inequalities in premature mortality and infant mortality by income and ethnicity in the USA decreased during the period of welfare expansion in the USA (‘war on poverty’ era 1966 to 1980), but they increased again during the Reagan–Bush period (1980–2002) when welfare services and healthcare coverage were cut. 46 Similarly, in England, inequalities in infant mortality rates reduced as child poverty decreased in a period of public sector and welfare state expansion (from 2000 to 2010), 47 but increased again when austerity was implemented and child poverty rates increased (from 2010 to 2017). 48

So this essay makes for grim reading for researchers, practitioners and policymakers concerned with health inequalities. Historically, pandemics have been experienced unequally with higher rates of infection and mortality among the most disadvantaged communities—particularly in more socially unequal countries. 8 9 Emerging evidence from a variety of countries suggests that these inequalities are being mirrored today in the COVID-19 pandemic. Both then and now, these inequalities have emerged through the syndemic nature of COVID-19—as it interacts with and exacerbates existing social inequalities in chronic disease and the social determinants of health. COVID-19 has laid bare our longstanding social, economic and political inequalities - even before the COVID-19 pandemic, life expectancy amongst the poorest groups was already declining in the UK and the USA and health inequalities in some European countries have been increasing over the last decade. 50 It seems likely that there will be a post-COVID-19 global economic slump—which could make the health equity situation even worse, particularly if health-damaging policies of austerity are implemented again. It is vital that this time, the right public policy responses (such as expanding social protection and public services and pursuing green inclusive growth strategies) are undertaken so that the COVID-19 pandemic does not increase health inequalities for future generations. Public health must ‘win the peace’ as well as the ‘war’.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Chris Orton from the Cartographic Unit, Department of Geography, Durham University, for his assistance with the graphics for figure 1 .

- Sydenstricker E

- Lawrence AJ

- SkyNews (27/03/20)

- Murray CJ ,

- Chin B , et al.

- Mamelund SE

- Grantz KH ,

- Salje H , et al.

- Bengtsson T ,

- Summers JA ,

- Stanley J ,

- Baker MG , et al.

- Chowell G ,

- Bettencourt LMA ,

- Johnson N , et al.

- Majia LSF , et al.

- Rutter PD ,

- Mytton OT ,

- Mak M , et al.

- Lowcock EC ,

- Rosella LC ,

- Foisy J , et al.

- Biggerstaff M ,

- Reed C , et al.

- Yousey-hindes K ,

- Crighton EJ ,

- Elliott SJ ,

- Moineddin R , et al.

- Catalan Agency for Health Quality and Assessment (AQuAS)

- Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre

- Chicago Department of Public Health

- Gkiouleka A ,

- Beckfield J , et al.

- Dahlgren G ,

- Whitehead M

- Zhang X , et al.

- Public health England

- European commission

- WHO - World Health. Organisation

- Copeland A ,

- Kasim A , et al.

- Lacobucci G

- Petticrew M ,

- Bambra C , et al.

- McNamara CL ,

- Thomson KH , et al.

- Segerstrom SC ,

- Whitehead M ,

- Pennington A ,

- Orton L , et al.

- Stuckler D ,

- Corcoran P ,

- Griffin E ,

- Arensman E , et al.

- Kinderman P ,

- Whitehead P

- Nylen L , et al.

- Mattheys K , et al.

- Krieger N ,

- Rehkopf DH ,

- Chen JT , et al.

- Robinson T ,

- Norman P , et al.

- Taylor-Robinson D ,

- Wickham S , et al.

- Beckfield J ,

- Forster T ,

- Kentikelenis A ,

Twitter Clare Bambra @ProfBambra.

Funding CB is a senior investigator in the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) ARC North East and North Cumbria, NIHR Policy Research Unit in Behavioural Science, NIHR School of Public Health Research, the UK Prevention Research Partnership SIPHER: Systems science in Public Health and Health Economics Research consortium, and the Norwegian Research Council Centre for Global Health Inequalities Research. JF is a senior investigator in the NIHR ARC East of England. FM is a senior investigator in the NIHR Policy Research Unit in Ageing and Frailty. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the funders.

Competing interests We have read and understood the BMJ Group policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: none.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Data sharing statement Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 Years On

February 2020

- Professor Sir Michael Marmot

- Jessica Allen

- Tammy Boyce

- Peter Goldblatt

- Joana Morrison

- Publication

- Inequalities

- Public health

- Social determinants of health

- Share on Twitter

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on Facebook

- Share on WhatsApp

- Share by email

- Link Copy link

This report has been produced by the Institute of Health Equity and commissioned by the Health Foundation to mark 10 years on from the landmark study Fair Society, Healthy Lives (The Marmot Review) .

The report highlights that:

- people can expect to spend more of their lives in poor health

- improvements to life expectancy have stalled, and declined for women in the most deprived 10% of areas

- the health gap has grown between wealthy and deprived areas

- place matters – living in a deprived area of the North East is worse for your health than living in a similarly deprived area in London, to the extent that life expectancy is nearly five years less.

The Health Foundation commissioned the Institute of Health Equity to examine progress in addressing health inequalities in England, 10 years on from the landmark study Fair Society, Healthy Lives (The Marmot Review).

Led by Professor Sir Michael Marmot, the review explores changes since 2010 in five policy objectives:

- giving every child the best start in life

- enabling all people to maximise their capabilities and have control over their lives

- ensuring a healthy standard of living for all

- creating fair employment and good work for all

- creating and developing healthy and sustainable places and communities.

For each objective the report outlines areas of progress and decline since 2010 and proposes recommendations for future action, setting out a clear agenda at a national, regional and local level.

Find out more

To hear more about the Health Foundation's work, go to our preference centre where you can sign up to receive email updates on topics including the social determinants of health, inequalities and public health.

Cite this publication

Marmot M, Allen J, Boyce T, Goldblatt P, Morrison J. Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 Years On. Institute of Health Equity; 2020 (health.org.uk/publications/reports/the-marmot-review-10-years-on).

Related reading

Share this page:

You might also like...

Health Foundation @HealthFdn

- Work with us

We look for talented and passionate individuals as everyone at the Health Foundation has an important role to play.

The Q community

Q is an initiative connecting people with improvement expertise across the UK.

Quick links

- News and media

- Events and webinars

Hear from us

Receive the latest news and updates from the Health Foundation

- 020 7257 8000

- [email protected]

- The Health Foundation Twitter account

- The Health Foundation LinkedIn account

- The Health Foundation Facebook account

Copyright The Health Foundation 2024. Registered charity number 286967.

- Accessibility

- Anti-slavery statement

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy policy

Cookies on the NHS England website

We’ve put some small files called cookies on your device to make our site work.

We’d also like to use analytics cookies. These send information about how our site is used to a service called Google Analytics. We use this information to improve our site.

Let us know if this is OK. We’ll use a cookie to save your choice. You can read more about our cookies before you choose.

Change my preferences I'm OK with analytics cookies

What are healthcare inequalities?

Health inequalities are unfair and avoidable differences in health across the population, and between different groups within society. These include how long people are likely to live, the health conditions they may experience and the care that is available to them.

The conditions in which we are born, grow, live, work and age can impact our health and wellbeing. These are sometimes referred to as wider determinants of health.

Wider determinants of health are often interlinked. For example, someone who is unemployed may be more likely to live in poorer quality housing with less access to green space and less access to fresh, healthy food. This means some groups and communities are more likely to experience poorer health than the general population. These groups are also more likely to experience challenges in accessing care.

The reasons for this are complex and may include:

- the availability of services in their local area

- service opening times

- access to transport

- access to childcare

- language (spoken and written)

- poor experiences in the past

- misinformation

People living in areas of high deprivation , those from Black, Asian and minority ethnic communities and those from inclusion health group , for example the homeless, are most at risk of experiencing these inequalities.

COVID-19 has shone a harsh light on some of the health and wider inequalities that persist in our society. Guidance issued by NHS England in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, set out eight urgent actions for tackling health inequalities. This was later refined to five key priority areas which underpin the work of the National Healthcare Inequalities Improvement Programme.

We have also developed our Core20Plus5 approach to support the reduction of healthcare inequalities.

The Kings Fund have some helpful information which explains health inequalities in more detail.

Understanding Health Inequalities Essay

Introduction.

Understanding what is meant by health inequalities is the first step in addressing the issue. Two central and separate UK health inquiries; one from Acheson and the other from the black report, helped to develop extensive debate regarding health inequalities. Subsequently, they triggered the need for policy and action in addressing the issue.

Different conceptual models have been used to explain and demonstrate how various factors influence individual and community health. Some of these factors such as age and sex are beyond d human intervention.

On the other hand, there are other wider factors which affect an individual’s health, and which can be controlled. There are various numerous debates related to the causes of these inequalities as well as on the most plausible action that should be taken to address these inequalities.

Health equity, also known as healthcare inequality or healthcare disparities refers to the differences that prevail with regard to the quality of health and related activities transversely different populations. The concept of health inequalities was not been a priority for the UK government in the 1980s and early 1990s.

In the 21 st century, evidence for escalated inequalities in the social pattern of health is beyond reasonable doubt and there is vast literature to support this. More than 800 empirical and conceptual papers have dedicated their time and effort to this topic since the late 1990s.

The area of research in health inequalities has been greatly politicized, right from the ideological context through explanatory frameworks to the various discourses that propose remedies to the problem. Reducing inequalities in health has become an integral part in as far as the UK Government policy is concerned.

The key debates related to inequalities and health in the UK, are on the causes on these inequalities and how they can be resolved.

Public health in Britain today is more or less of a paradox where despite the fact that Britain now experiences greater health than it has ever experienced in history, health inequalities had remained to be stubbornly ubiquitous. Several authors have come forth to present the setbacks of health inequalities in the United Kingdom.

This paper aims at identifying and critically reviewing what different authors have got say about this issue in their different works. It has analyzed different conceptual and policy debates which are paramount in as far as inequalities in health are concerned. It has pointed out the respective material and psychosocial influences on health inequalities.

The paper is quizzical on the direction ought to be taken by public health professionals in influencing policies, as well as their implementation in relation to health inequalities. This is of concern in a world where much emphasis is on wealth creation as opposed to addressing poverty.

The years 1980-2005 were a period marked by huge growth in international research and vast literature aimed at demonstrating the inequalities in health, and the governance of poverty as a potential cause of these inequalities. Davey Smith and colleagues at the University of Bristol have made great contributions to this concept by generating evidence to support it.

Davey Smith, et al (1999) responded to Acheson’s report (1998) on health inequalities evident in the UK. The Acheson’s report shows the existence of health disparities and their correlation with social class. The findings showed a general decline in mortality between 1970 and 1990, but that of the upper social classes was characterized by a more rapid decline.

Acheson mentions 39 policies that are applicable in ameliorating health inequalities in various sectors of the economy that range from taxation to agriculture. This report had a great influence on “Out Healthier Nation: A Contract for Health”, the 1998 government green paper and the 1999 “Saving Lives: Our Healthier Nation”, white paper.

Davey Smith, et al not only reviewed Acheson’s data indicating the escalation in health inequalities but also argued that the solution to this escalation could be easily solved.

He states, “Any child can tell you how this can be achieved: the poor have too little money so the solution to ending their poverty is to give them more money. Poverty reduction therefore can be really attained by throwing money at the problem”, (Davey Smith, et al., 1999, 378).

Labonte, 1999 has also placed an argument based on Acheson’s report. Labonte says that there is need to go beyond just analyzing health inequalities to grappling with policy options. Labonte notes that Acheson’s and related reports did not bring about change, instead they became legitimizing tools for those who were committed to change.

They are basically ideological tools which are more essential than evidence base in creation and development of policies. However, Acheson did not provide a basis for continued debate on inequalities within the government.

Acheson has been criticized by Labonte as not relating economic practices with social inequalities as he has done with social aspects and health inequalities. Acheson also failed to probe into the existence of poverty hence has left some crucial components related to health and inequalities unturned.

O’Keefe (2000) has argued out the causes of health inequalities based on globalization, which is considered to have an increasing influence on social policy in all countries.

She explains that decisions related to health inequalities are made by “undemocratic trans-national regulatory organizations that include the World Trade Organization”.

O’Keefe suggests that deliberative democracy placed at the heart of such trans-national bodies could be an ideal solution for the health inequalities experienced in the different countries. However, this was dependant on the world-wide strength to question the unjust social structures that operate on a global level.

In her work, Stewart-Brown 2000 probes into the causes of social inequality. Stewart-Brown is puzzled by the impression derived from this question. It has become more or less like a taboo in literature. Stewart-Brown has used a contrary analytical approach different from that of Davey Smith, et al., and Labonte as discussed earlier on. She has borrowed from conflict management and psychotherapeutic theory.

She implies that the problem of social inequalities in health can be resolved by a development in the direction of emotional literacy involving all income groups and especially those with most wealth by so doing (Stewart-Brown, 2000).

Davey Smith, et al., (2000) have demonstrated that ethnic differences in health status in their review on the UK epidemiological evidence on ethnic health inequalities. Various types of explanations have been explored in this review that entail migration, culture, artefact, behaviour, biology, socioeconomic factors and racism.

They conclude by suggesting that influences falling under the different explanations would largely contribute to the production of ethnic differentials in health. However, production of more sensitive socioeconomic indicators is required if clarity and definitiveness is to be achieved.

Bolam, et al., (2003) have focused on an important and current issue of debate on inequalities in health based on the contribution of psychological factors while looking at structural, material and economic factors related to health.

Bolam and others have advanced this debate by coming up with a more complex and entirely socialized theory that examines the key component in psychological explanations known as the “the sense of control over health”. In their article, Bolam and others explore these determinants by analysing interviews where 30 lower socioeconomic status participants engaged in the interviews.

The participants were obtained from two qualitative studies on health inequalities. The major findings were bent on the correlation of two contrasting factors on control over health, that is, “fatalism and positive thought”.

The debate on material and psychosocial explanations for health inequalities has imperative policy implications and especially macro-economic policy and appropriate interventions with regard to health services. There is one important health service intervention in the UK aimed at reducing health inequalities, and this is the nation-wide programme on smoking cessation.

Woods et al (2003) have noted the implementation of this programme during early implementing health action zones. Woods and others are not at all enthusiastic about this programme because it is only a rhetoric act by the government but, despite this, smoking cessation has been categorically and centrally steered.

They argue that despite the fact that smoking cessation may lead to an overall population-level minimization in smoking, it have the potential of causing a wider gap than the current one in as far as health inequality is concerned.

A similar theoretical debate by Muntaner, et al., (2000) in their thought provoking article have brought focus on the worth of the concept of ‘social capital’ with regard to comprehending and identifying an appropriate action on health inequalities. Muntaner and others have challenged the theoretical value as well as the evidence base that shows social capital to be a determinant of health inequalities.

They show the use of social capital as an alternative to party politics and economic redistribution within the state and it is because of this that they are sceptical about its practical benefit in addressing health inequalities.

Morrow (2000) explores the accounts of young people with regard to the community and neighbourhood while using the concept of social capital, and the effect on health inequalities. In his work, it is evident that Morrow realises the limitations of the social capital concept but Morrow has argued out that it is valuable in helping the young people explicitly understand their social environment.

Ostry, et al., (2000) studied the “relationship between unemployment, technological change and psychological work conditions in restructured work places in British Columbian sawmills”. In this study there was a downsizing of the employees where reduction took place in terms of number and job title.

It was evident that psychosocial conditions of work were ameliorated after the downsizing but, only few workers experienced these better work conditions. Even though this was the case there was a need for future improvements based on the lessons learnt.

To start with, a population based approach is very important while assessing the implication of downsizing because a long-term follow-up of the downsized workers is important. Secondly, there is great need to pay attention to the long-term implications associated with employment and their effects on health with regard to the downsized workers and especially those who are less than 35 years.

Also, the downsizing resulted in escalated levels of control, which was more steepened across the different job categories in 1997 as compared with 1965. This was considered to have health implications and mainly so for the unskilled workers where downsizing had taken place. Lastly, the method used for assessing the working conditions needed improvement. Self-reports ought to be used in such future studies.

Methodological challenges are evident in relation to evaluating the policy interventions aimed at reducing health inequalities. Evans Shito and Keskimaki (2000) have placed great attention on the description of the long term Finnish policy goal addressing health inequalities. They have outlined the barriers to successful policy programmes with regard to addressing these inequalities.

In a similar light of debate, Evans and Killoran (2000) have made a report on “realistic evaluation”. In this report they have realistically evaluated five UK projects put in place so as to test the effect of five partnership models in addressing health inequalities.

They identify six key themes, which are “shared strategic vision, leadership and management; relations and local ownership; accountability; organizational readiness and responsiveness to a changing environment”.

The need to understand how the mechanisms used in the project were executed in the light of local and national policy change has been greatly emphasized. Lessons for programmes on health improvement in the UK, primary care groups and health action zones have been identified.

Asthana and Halliday (2006) have argued about health inequalities with regard to how they should be objectively tackled in the UK. This is in accordance with the prevailing scepticisms on the best approach to take while translating broad policy recommendations into practical actions. The value of local level initiatives has remained to be a great concern due to its implicit nature.

In this book, key targets for intervention have been identified via a comprehensive exploration of the directive and procedures that lead to health inequalities across populations. The authors have examined both national policy content and local practice in determining what is applicable in addressing health inequalities, why and how it works.

This book is authoritative but, very much accessible in providing a detailed account of “theory, policy and practice” hence, creating a good debate ground for what works and what does not work in as far as addressing health inequalities in the UK is concerned.

An article by Buch, 2010 on “Health Inequalities in the UK-Our most Pressing Problem” has presented a debate that was held by the British Medical Association on health inequalities. The debate was centred on the most pressing problem at hand: why there was such a great gap between the different sections of the British population in relation to health and what the most ideal solution to the problem was.

Evidence by Professor Marmot showed that there was a seven year gap with regard to life expectancy. There was also a 19 year gap with regard to healthy life expectancy between the lowest and the highest socioeconomic groups. Ameliorating health inequalities via trying to equalize the socioeconomic status of each and every person would be faced by major challenges. Health agenda was considered to rhyme the environmental agenda where walking, moderate consumption of meat and cycling were encouraged (Buch, 2010).

The question therefore was on how health inequalities could be effectively addressed. Lack of commitment and will are some of the suggested reasons for the persistent escalating health inequalities. There is weighted evidence that the gap related to health inequalities can be filled through policies already developed.

However, the politicians are still struggling with the direction in which they would take in implementing the changes. The government continuously comes up with various ideologies on how to address the health inequalities. Unfortunately, they never get to seriously work on them as they are always debating on how these inequalities could be addressed without doing anything.

“The Impact of Inequality: How to make Sick Societies Healthier” by Wilkinson (2005) is a continuation of his book, “Unhealthy Societies: The Afflictions of Inequality”. The current book reviews the present status of knowledge and offers an explanation as to what causes the health inequalities as well as providing potential solutions to the problem.

This book consists of highly assembled and valuable evidence with an articulate and convincing argument suitable for use by epidemiologists, policy makers, social scientists, public health officials and students.

It is Wilkinson’s ideologies that provoke thought like when he wonders of the difference in government’s response to health inequalities if income gradient in relation to health were to be different. An illustration of this is what the response would be if the higher income groups were the ones experiencing worst health.

Wilkinson has written the book from a particular point of view, that which focuses on social justice and reform. He does not criticize capitalism as per se and does not posit extreme ideologies. Wilkinson’s view of social progress is very much in existence in the contemporary UK society, where market is part and parcel of the existing societal structure.

According to Wilkinson, inequalities in health can be reduced, better stress management mechanism developed to reduce social stress and the quality of social relations made to be better. All these efforts would play a very vital role in improving the health and well-being across populations in the society.

His conclusion is on an optimistic stand-point as he acknowledges the health inequalities across populations but then again, he says that change is very much possible and that the health inequalities can be reduced.

The universe is still in the process of expansion in as far as moral democratic values are concerned, this coupled with growing sensitivity to the suffering of others, Wilkinson points out that a decrease in inequality and improvement of well-being across the social classes was very imperative in strengthening political goals.

Carlisle (2001) has presented the debates related to inequalities and health based on three different explanatory discourses as presented by Macintyre (1997). The first, hereditarianism explanations, on class variations in relation to disease have been presented based on the argument that people’s social position is dependent on natural capacity that is biologically determined.

Based on this perception, variations in health are considered to be inevitable and nothing much can be done about them. Behavioural explanations have been used to justify the high mortality rate amongst labouring classes and ill health of the economically poor sections of the population as a subsequent result of working-class maternal ignorance alongside living conditions that are not up to standard.

In this case, education would have been a preferable measure in improving health. The environmental aspect attributed causes of inequalities in health considered to widespread poverty and material components of urban industrial life. Based on the latter, social reforms were considered to be of great value in addressing the environmental aspect in as far as health and inequalities were concerned.

Popay, et al., (1998) in their review of modern research, have presented a debate based on two main constructions that continue to govern research pertaining to health inequalities. The first construction is individual behaviours and lifestyle while the second one is social inequalities and injustice.

There are some elements of continuity with regard to historical environmental explanations on poverty and deprivation, and behavioural/ hereditarianism explanations on lifestyle and culture the causes of health inequalities.

Nonetheless, differences exist in relation to social values and political ideology in the different explanatory discourses and all are directed at identification of appropriate and applicable policies.

Carlisle concludes by suggesting that lack of clarity revolving around competing explanations fosters political skilful moves at the policy level where the UK government seeks leadership in grappling with the issue, while delegating responsibility to community members and individual figures.

Carlisle presents an overview of three but highly contested explanations that are linked to inequalities in health in the contemporary world. These are poverty/deprivation, psychological stress and individual deficit. The deprivation facet is a strong evidence for the inequalities but it is not complete.

Various critics focus on the barrier of the gradient since health inequalities are not only found within the poorer segments of the society but are a sequel of social class gradients (Marmot et al., 1991). Material differences therefore are not adequate in explaining this. The psychosocial stress model was developed to fill in the gaps from the poverty model.

It views the problem as a generative mechanism for inequalities in health based on the relationship between the individual person and social structure. The individual deficit model has similarly acknowledged social inequality but does not focus much on restructuring the society as compared with addressing the problem and at individual level, examining their culture as well.

Heller, et al., (2002) has argued out the widening and large gap in mortality rate between those at the extreme ends of social distribution despite the amelioration in overall mortality rate. It is this gap between the extremes that has been indicated to be the relative mortality variation between those who experience greatest and least deprivation.

Heller and others have shown that the changes in social distribution that transverse the population has been a major contributor to the reduced mortality rate. Heller and others have argued out that based on their findings, there is no widening gap in overall health inequality when redistribution within the social classes is factored in.

According to the review of both Mackenbach and Kunst (1997) on the different methods of overall health inequality assessment in any population, none of them can be pointed out to be the very best.

Heller and others have used a method that does not directly address the issue despite the fact that it is flexible to changes in social class distribution and allows description of mortality within social classes. Unfortunately, Heller and others have used a method that presumes that every member within a certain social class has the same predisposing risk of mortality.

In addition, when one moves from one social class to another, he or she adopts that mortality profile of that new social class. This is not usually the case and especially in the short-term. The method used to sasses the degree of health inequality in relation to the widening gap of mortality between the extremes of social distribution may be inaccurate as the change may be partly attributed to artefact of health selection.