How to organize research for your novel

Follow this step-by-step guide to learn the modern process of organizing research in Milanote, a free tool used by top creatives.

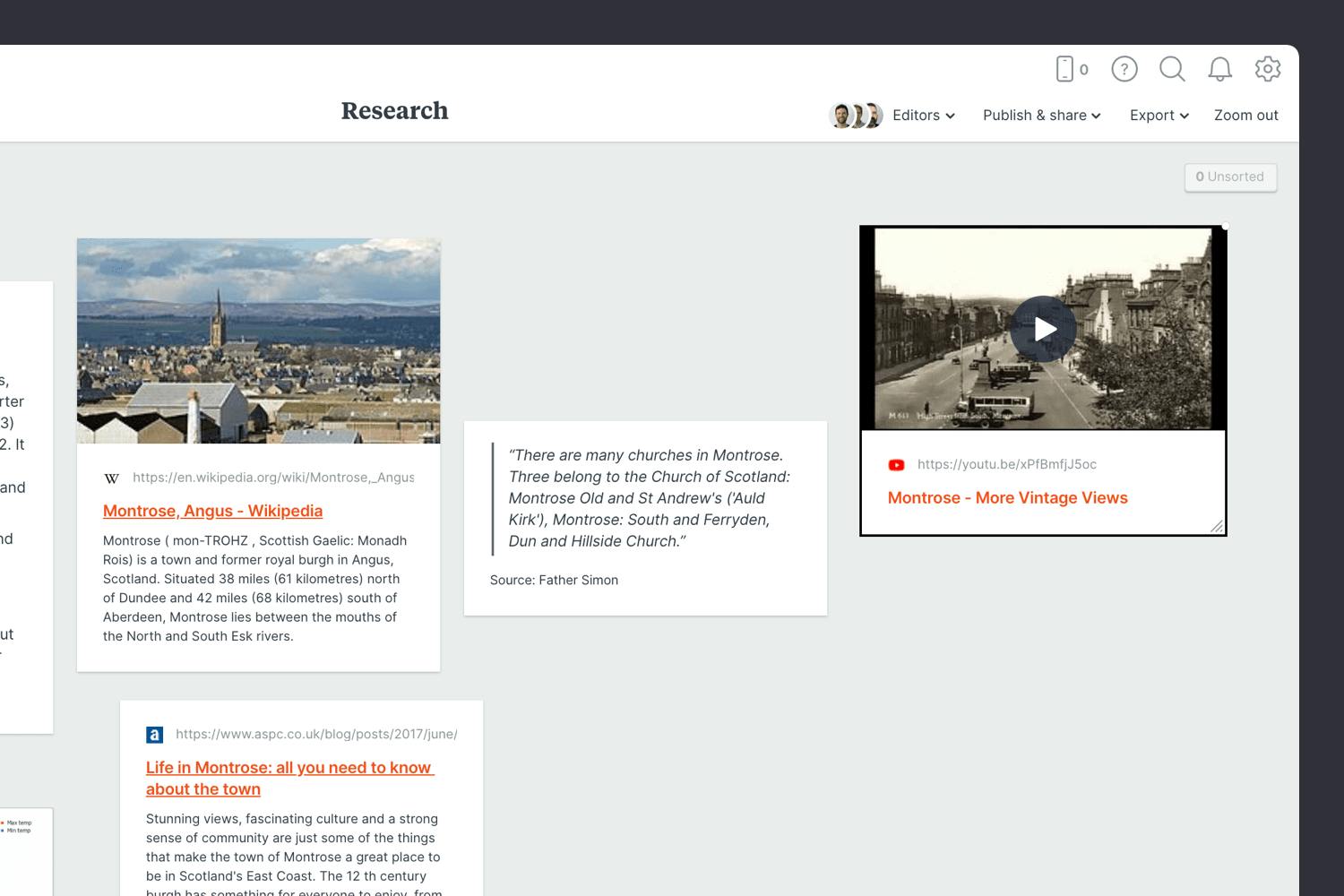

How to organize your research in 7 easy steps

Whether you're writing a sci-fi thriller or historical fiction, research is a crucial step in the early writing process. It's a springboard for new ideas and can add substance and authenticity to your story. As author Robert McKee says "when you do enough research, the story almost writes itself. Lines of development spring loose and you'll have choices galore."

But collecting research can be messy. It's often scattered between emails, notes, documents, and even photos on your phone making it hard to see the full picture. When you bring your research into one place and see things side-by-side, new ideas and perspectives start to emerge.

In this guide, you'll learn the modern approach to collecting and organizing research for your novel using Milanote. Remember, the creative process is non-linear, so you may find yourself moving back and forth between the steps as you go.

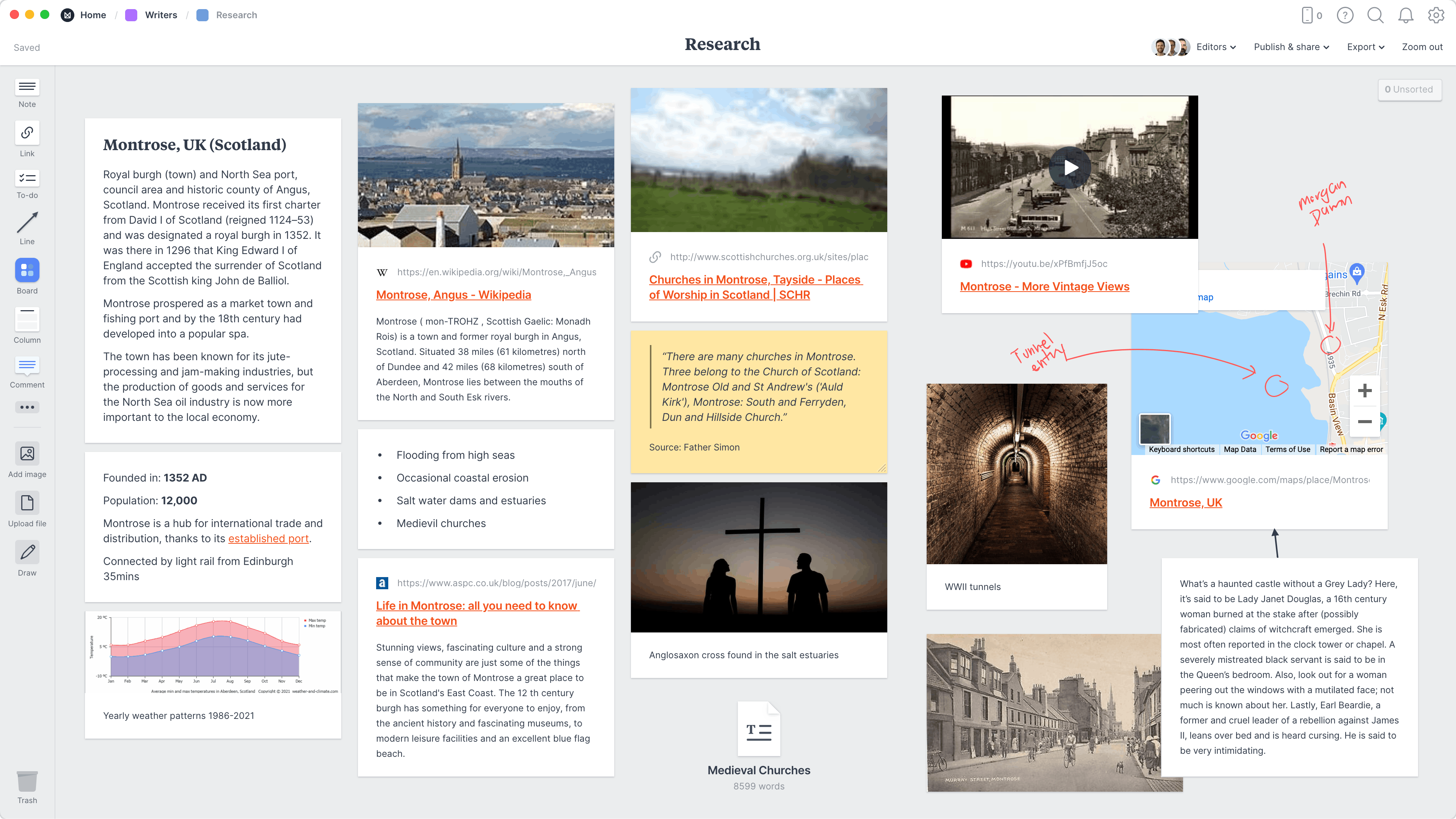

1. First, add any existing notes

You probably know a lot about your chosen topic or location already. Start by getting the known facts and knowledge out of your head. Even if these topics seem obvious to you, they can serve as a bridge to the rest of your research. You might include facts about the location, period, fashion or events that take place in your story.

Create a new board to collect your research.

Create a new board

Drag a board out from the toolbar. Give it a name, then double click to open it.

Add a note to capture your existing knowledge on the topic.

Drag a note card onto your board

Start typing then use the formatting tools in the left hand toolbar.

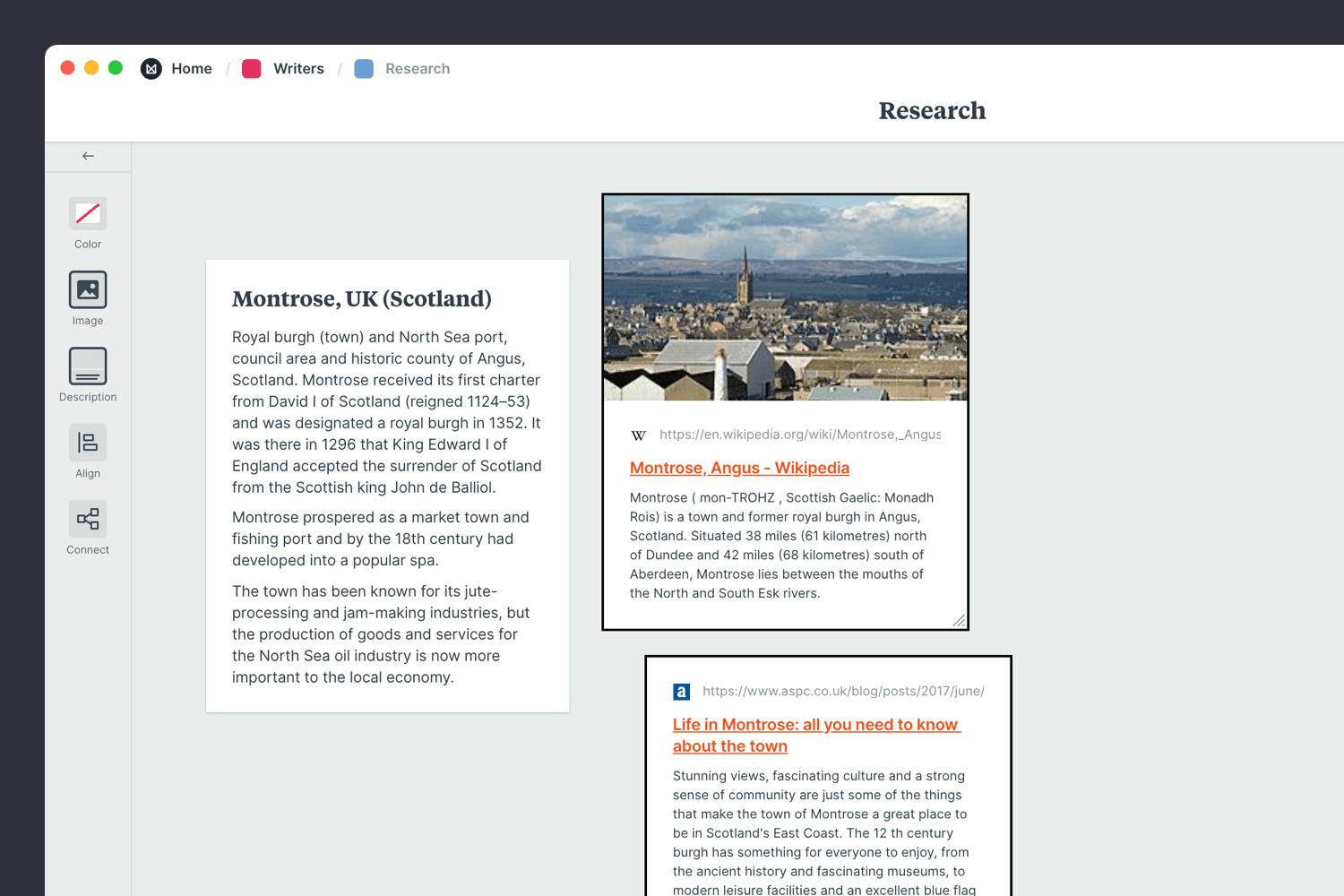

2. Save links to articles & news

Wikipedia, blogs, and news websites are a goldmine for researchers. It's here you'll find historical events and records, data, and opinions about your topic. We're in the 'collecting' phase so just save links to any relevant information you stumble across. You can return and read the details at a later stage.

Drag a link card onto your board to save a website.

Install the Milanote Web Clipper

Save websites and articles straight to your board.

Save content from the web

With the Web Clipper installed, save a website, image or text. Choose the destination in Milanote. Return to your board and find the content in the "Unsorted" column on the right.

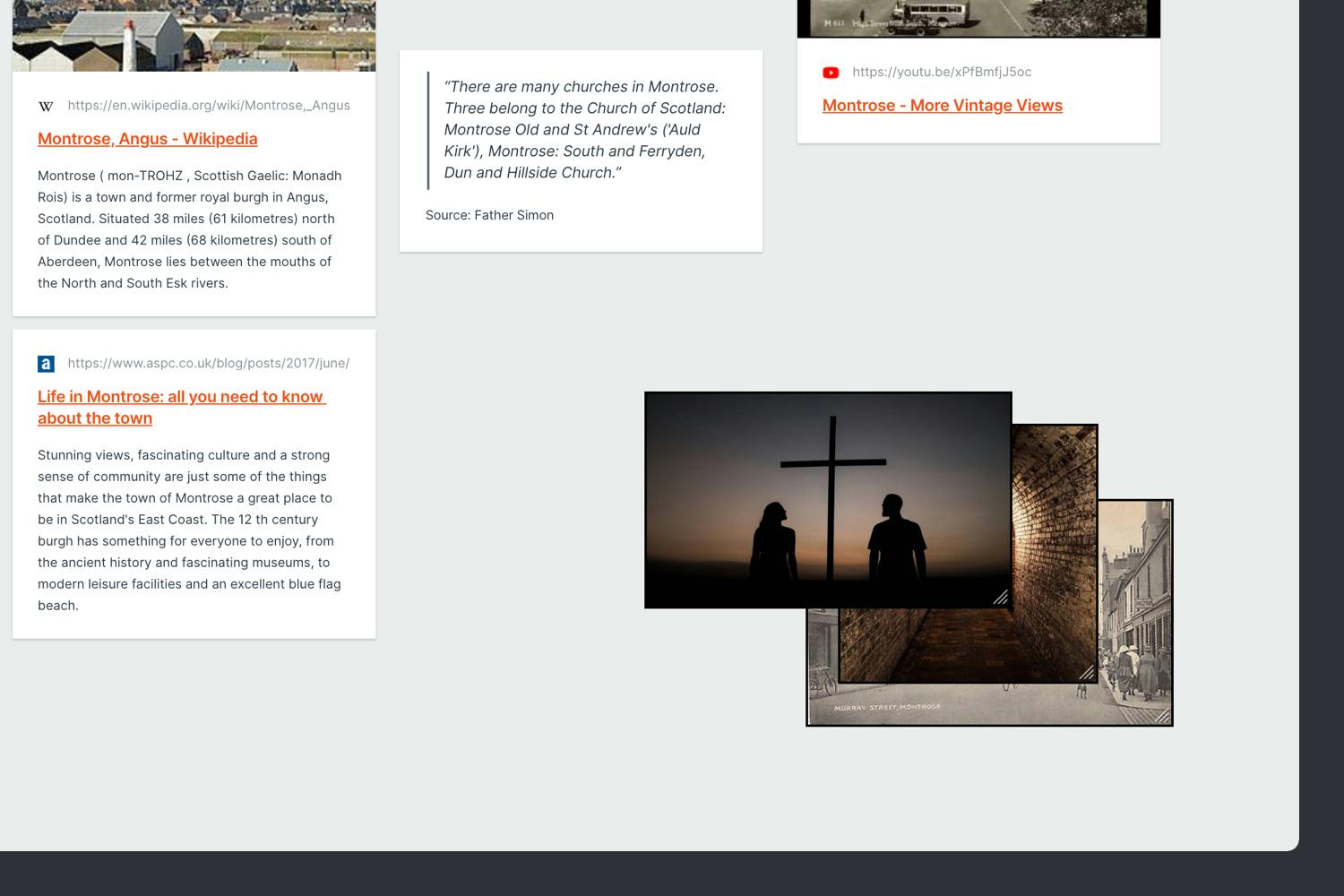

3. Save quotes & data

Quotes are a great way to add credibility and bring personality to your topic. They're also a handy source of inspiration for character development, especially if you're trying to match the language used in past periods. Remember to keep the source of the quote in case you need to back it up.

Add a note to capture a quote.

4. Collect video & audio

Video and movie clips can help you understand a mood or feeling in a way that words sometimes can't. Try searching for your topic or era on Vimeo , or Youtube . Podcasts are another great reference. Find conversations about your topic on Spotify or any podcast platform and add them into the mix.

Embed Youtube videos or audio in a board.

Embed Youtube videos or audio tracks in a board

Copy the share link from Youtube, Vimeo, Soundcloud or many other services. Drag a link card onto your board, paste your link and press enter.

5. Collect important images

Sometimes the quickest way to understand a topic is with an image. They can transport you to another time or place and can help you describe things in much more detail. They're also easier to scan when you return to your research. Try saving images from Google Images , Pinterest , or Milanote's built-in image library.

Use the built-in image library.

Use the built-in image library

Search over 500,000 beautiful photos powered by Unsplash then drag images straight onto your board.

Save images from other websites straight to your board.

Roll over an image (or highlight text), click Save, then choose the destination in Milanote. Return to your board and find the content in the "Unsorted" column on the right.

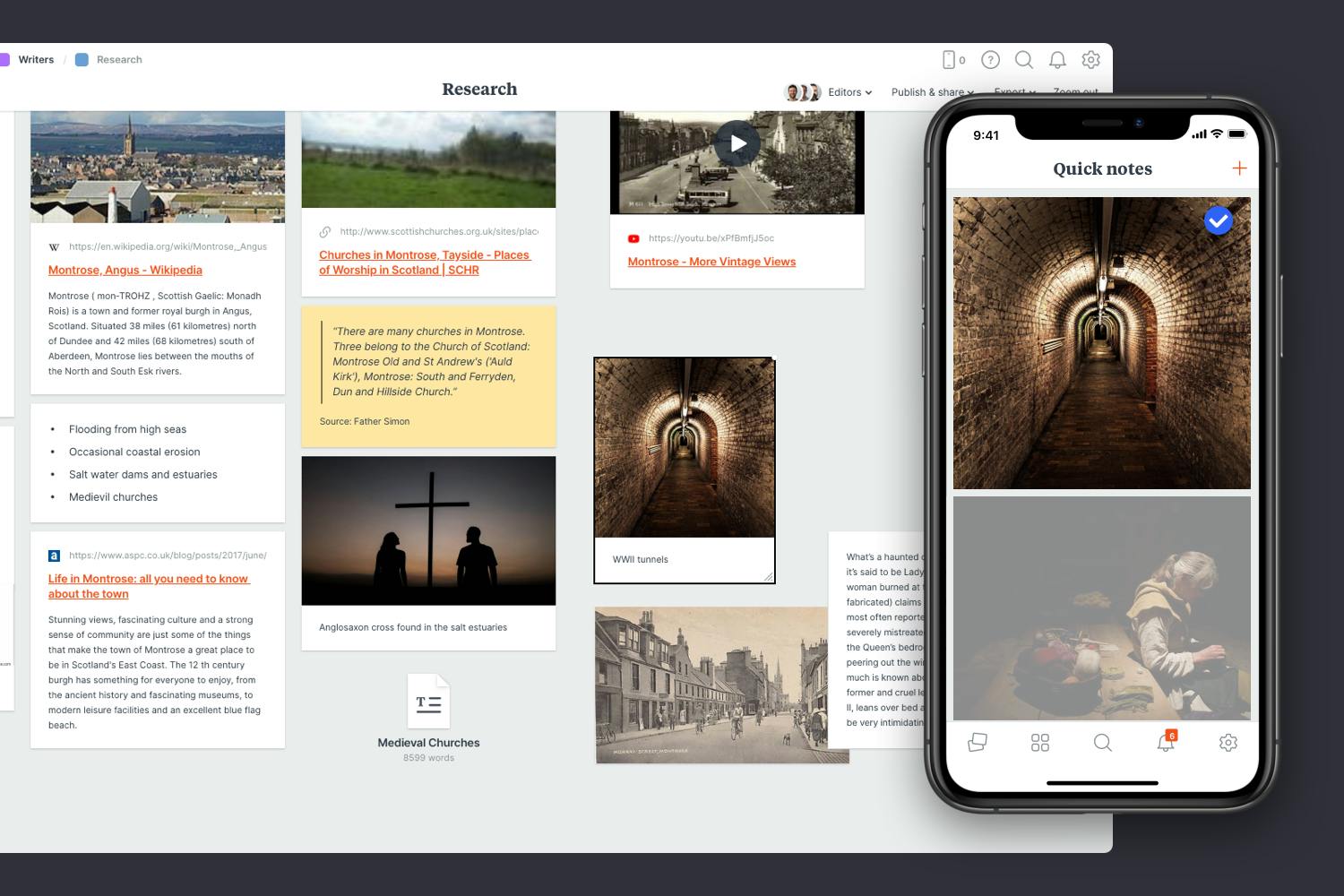

Allow yourself the time to explore every corner of your topic. As author A.S. Byatt says "the more research you do, the more at ease you are in the world you're writing about. It doesn't encumber you, it makes you free".

6. Collect research on the go

You never know where or when you'll find inspiration—it could strike you in the shower, or as you're strolling the aisles of the grocery store. So make sure you have an easy way to capture things on the go. As creative director Grace Coddington said, "Always keep your eyes open. Keep watching. Because whatever you see can inspire you."

Download the Milanote mobile app

Save photos straight to your Research board.

Take photos on the go

Shoot or upload photos directly to your board. When you return to a bigger screen you'll find them in the "Unsorted" column of the board.

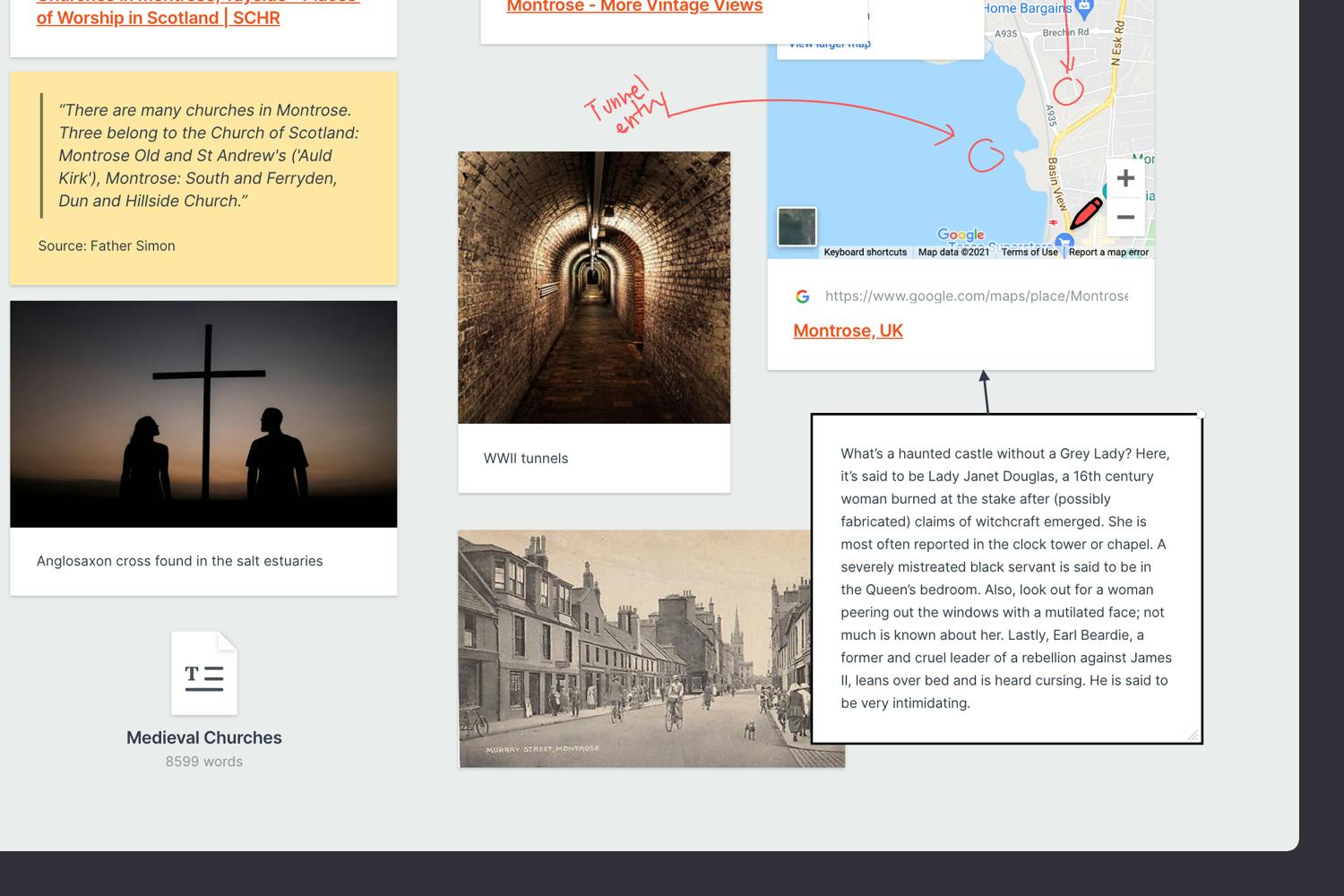

7. Connect the dots

Now that you have all your research in one place, it's time to start drawing insights and conclusions. Laying out your notes side-by-side is the best way to do this. You might see how a quote from an interviewee adds a personal touch to some data you discovered earlier. This is the part of the process where you turn a collection of disparate information into your unique perspective on the topic.

That's a great start!

Research is an ongoing process and you'll probably continue learning about your topic throughout your writing journey. Reference your research as you go to add a unique perspective to your story. Use the template below to start your research or read our full guide on how to plan a novel .

Start your research

Get started for free with one of Milanote's beautiful templates.

Sign up for free with no time limit

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

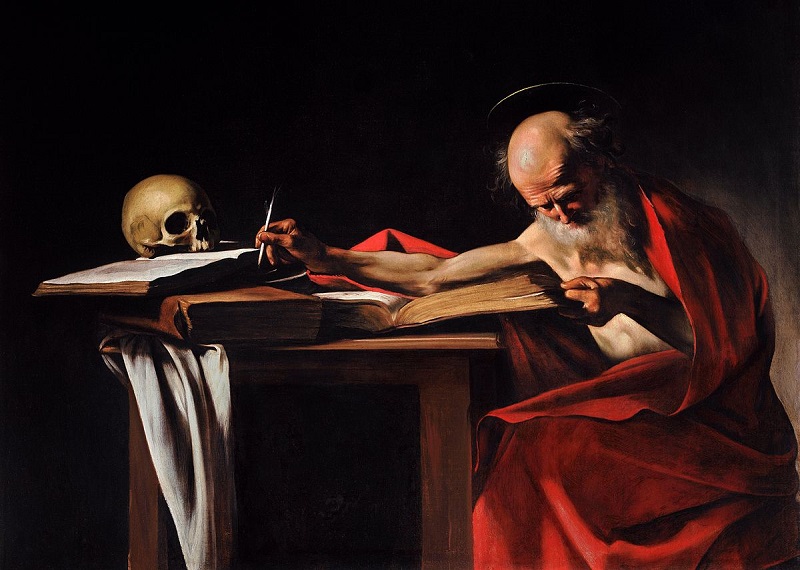

On the Fine Art of Researching For Fiction

Jake wolff: how to write beyond the borders of your experience.

The first time I considered the relationship between fiction and research was during a writing workshop—my first—while I watched the professor eviscerate some poor kid’s story about World War II. And yeah, the story was bad. I remember the protagonist being told to “take cover” and then performing several combat rolls to do so.

“You’re college students,” the professor said. “Write about college students.”

Later, better professors would clarify for me that research, with a touch of imagination, can be a perfectly valid substitute for experience. But that’s always where the conversation stopped. If we ever uttered the word “research” in a workshop, we did so in a weaponized way to critique a piece of writing: “This desperately needs more research,” we’d all agree, and then nothing more would be said. We’d all just pretend that everyone in the room already knew how to integrate research into fiction and that the failures of the story were merely a lack of effort rather than skill. Secretly, though, I felt lost.

I knew research was important, and I knew how to research. My questions all had to do with craft. How do I incorporate research into fiction? How do I provide authenticity and detail without turning the story into a lecture? How much research is too much? Too little?

How do I allow research to support the story without feeling obligated to remain in the realm of fact—when I am, after all, trying to write fiction?

I heavily researched my debut novel, in which nearly every chapter is science-oriented, historical, or both. I’d like to share a method I used throughout the research and writing process to help deal with some of my questions. This method is not intended to become a constant fixture in your writing practice. But if you’re looking for ways to balance or check the balance of the amount of research in a given chapter, story, or scene, you might consider these steps: identify, lie, apply.

I recently had a conversation with a former student, now a friend, about a short story he was writing. He told me he was worried he’d packed it too full of historical research.

“Well,” I said, “how much research is in there?”

“Uhhh,” he answered. “I’m not sure?”

That’s what we might call a visualization problem. It’s hard to judge the quantity of something you can’t see.

I’ve faced similar problems in my own work. I once received a note from my editor saying that a certain chapter of my novel read too much like a chemistry textbook. At first, I was baffled—I didn’t think of the chapter as being overly research-forward. But upon reading it again, I realized I had missed the problem. After learning so much about chemistry, I could no longer “see” the amount of research I had crammed into twenty pages.

Literature scholars don’t have this problem because they cite their sources; endnotes, footnotes, and the like don’t merely provide a tool for readers to verify claims, but also provide a visual reminder that research exists within the text. Thankfully, creative writers generally don’t have to worry about proper MLA formatting (though you should absolutely keep track of your sources). Still, finding a quick way to visually mark the research in your fiction is the least exciting but also the most important step in recognizing its role in your work.

Personally, I map my research in blue. So when my editor flagged that chapter for me, I went back to the text and began marking the research. By the end of the process, the chapter was filled with paragraphs that looked like this one:

Progesterone is a steroid hormone that plays an especially important role in pregnancy. Only a few months before Sammy arrived in Littlefield, a group of scientists found the first example of progesterone in plants. They’d used equipment I would never be able to access, nuclear magnetic resonance and mass spectroscopy, to search for the hormone in the leaves of the English Walnut trees. In humans, aging was associated with a drop in progesterone and an increase in tumor formation—perhaps a result of its neurosteroidal function.

My editor was spot-on: this barely qualified as fiction. But I truly hadn’t seen it. As both a writer and teacher, I’m constantly amazed by how blind we can become to our own manuscripts. Of course, this works the other way, too: if you’re writing a story set in medieval England but haven’t supported that setting with any research, you’ll see it during this step. It’s such an easy, obvious exercise, but I know so few writers who do this.

Before moving on, I’ll pause to recommend also highlighting research in other people’s work. If there’s a story or novel you admire that is fairly research-forward, go through a few sections and mark anything that you would have needed research to write. This will help you see the spacing and balance of research in the fiction you’re hoping to emulate.

(Two Truths and a) Lie

You’ve probably heard of the icebreaker Two Truths and a Lie: you tell two truths and one lie about yourself, and then the other players have to guess which is the lie. I’d rather die than play this game in real life, but it works beautifully when adapted as a solo research exercise.

It’s very simple. When I’m trying to (re)balance the research in my fiction, I list two facts I’ve learned from my research and then invent one “fact” that sounds true but isn’t. The idea is to acquaint yourself with the sound of the truth when it comes to a given subject and then to recreate that sound in a fictive sentence. It’s a way to provide balance and productivity, ensuring that you’re continuing to imagine and invent —to be a fiction writer— even as you’re researching.

I still have my notes from the first time I used this exercise. I was researching the ancient Chinese emperor Qin Shi Huang for a work of historical fiction I would later publish in One Story. I was drowning in research, and the story was nearing fifty pages (!) with no end in sight. My story focused on the final years of the emperor’s life, so I made a list of facts related to that period, including these:

1. The emperor was obsessed with finding the elixir of life and executed Confucian scholars who failed to support this obsession.

2. If the emperor coughed, everyone in his presence had to cough in order to mask him as the source.

3. The emperor believed evil spirits were trying to kill him and built secret tunnels to travel in safety from them.

Now, the second of those statements is a lie. My facts were showing me that the emperor was afraid of dying and made other people the victims of that fear—my lie, in turn, creates a usable narrative detail supporting these facts. I ended up using this lie as the opening of the story. I was a graduate student at the time, and when I workshopped the piece, my professor said something about how the opening worked because “It’s the kind of thing you just can’t make up.” I haven’t stopped using this exercise since.

We have some facts; we have some lies. The final step is to integrate these details into the story. We’ll do this by considering their relationship to the beating heart of fiction: conflict. You can use this step with both facts and lies. My problem tends to be an overload of research rather than the opposite, so I’ll show you an example of a lie I used to help provide balance.

In a late chapter in my book, three important characters—Sammy and his current lover Sadiq and his ex- lover Catherine—travel to Rapa Nui (Easter Island). They’ve come to investigate a drug with potential anti-aging properties that originates in the soil there (that’s a fact; the drug is called rapamycin). As I researched travel to Easter Island, my Two Truths and a Lie exercise produced the following lie:

There are only two airports flying into Easter Island; these airports constantly fight with each other.

In reality, while there are two airports serving Easter Island (one in Tahiti; the other in Chile), nearly everyone flies from Chile, and it’s the same airline either way. On its surface, this is the kind of lie I would expect to leave on the cutting room floor—it’s a dry, irrelevant detail.

But when I’m using the ILA method, I try not to pre-judge. Instead, I make a list of the central conflicts in the story or chapter and a list of the facts and lies. Then I look for applications—i.e., for ways in which each detail may feel relevant to the conflicts. To my surprise, I found that the airport lie fit the conflicts of the chapter perfectly:

Ultimately, the airport lie spoke to the characters, all of whom were feeling the painful effects of life’s capriciousness, the way the choices we make can seem under our control but also outside it, arbitrary but also fateful. I used this lie to introduce these opposing forces and to divide the characters: Sammy and Sadiq fly from Tahiti; Catherine flies from Chile.

Two airports in the world offered flights to Rapa Nui—one in Tahiti, to the west, and one in Chile, to the east. Most of the scientists stayed in one of those two countries. There was no real meaning to it. But still, it was hard, in a juvenile way, not to think of the two groups as opposing teams in a faction. There was the Tahiti side, and there was the Chile side, and only one could win.

This sort of schematic—complete with a table and headers—may seem overly rigid to you, to which I’d respond, Gee, you sound like one of my students. What can I say? I’m a rigid guy. But when you’re tackling a research-intensive story, a little rigidity isn’t the worst thing. Narrative structure does not supply itself. It results from the interplay between the conflicts, the characters, and the details used to evoke them. I’m presenting one way, of many, to visualize those relationships whenever you’re feeling lost.

Zora Neal Hurston wrote, “Research is formalized curiosity. It is poking and prying with a purpose.” Maybe that’s why I’m thinking of structure and rigidity—research, for me, is bolstering in this way. It provides form. But it’s also heavy and hard to work with. It doesn’t bend. If you’re struggling with the burden of it, give ILA a shot and see if unsticks whatever is holding you back. If you do try this approach, let me know if it works for you—and if it doesn’t, feel free to lie.

__________________________________

Jake Wolff’s The History of Living Forever is out now from FSG.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Previous Article

Next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

How to Eulogize an Animal

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Fiction as Research Practice Short Stories Novellas and Novels

Related Papers

Alberta Journal of Educational Research

Frances Kalu

Fiction as Method

Theo Reeves-Evison

See the world through the eyes of a search engine, if only for a millisecond; throw the workings of power into sharper relief by any media necessary; reveal access points to other worlds within our own. In the anthology Fiction as Method, a mixture of new and established names in the fields of contemporary art, media theory, philosophy, and speculative fiction explore the diverse ways fiction manifests, and provide insights into subjects ranging from the hive mind of the art collective 0rphan Drift to the protocols of online self-presentation. With an extended introduction by the editors, the book invites reflection on how fictions proliferate, take on flesh, and are carried by a wide variety of mediums—including, but not limited to, the written word. In each case, fiction is bound up with the production and modulation of desire, the enfolding of matter and meaning, and the blending of practices that cast the existing world in a new light with those that participate in the creation of new openings of the possible.

Markku S. Hannula

Barbara Barter

mathias bejean

Nike Pamela

Perspectives on Psychological Science

Keith Oatley

Fiction literature has largely been ignored by psychology researchers because its only function seems to be entertainment, with no connection to empirical validity. We argue that literary narratives have a more important purpose. They offer models or simulations of the social world via abstraction, simplification, and compression. Narrative fiction also creates a deep and immersive simulative experience of social interactions for readers. This simulation facilitates the communication and understanding of social information and makes it more compelling, achieving a form of learning through experience. Engaging in the simulative experiences of fiction literature can facilitate the understanding of others who are different from ourselves and can augment our capacity for empathy and social inference.

Cambridge Scholars

Michelangelo Paganopoulos

This volume invites the reader to join in with the recent focus on subjectivity and self-reflection, as the means of understanding and engaging with the social and historical changes in the world through storytelling. It examines the symbiosis between anthropology and fiction, on the one hand, by looking at various ways in which the two fields co-emerge in a fruitful manner, and, on the other, by re-examining their political, aesthetic, and social relevance to world history. Following the intellectual crisis of the 1970s, anthropology has been criticized for losing its ethnographic authority and vocation. However, as a consequence of this, ethnographic scope has opened towards more subjective and self-reflexive forms of knowledge and representations, such as the crossing of the boundaries between autobiography and ethnography. The collection of essays re-introduces the importance of authorship in relationship to readership, making a ground-breaking move towards the study of fictional texts and images as cultural, sociological, and political reflections of the time and place in which they were produced. In this way, the contributors here contribute to the widening of the ethnographic scope of contemporary anthropology. A number of the chapters were presented as papers in two conferences organised by the Association of Social Anthropologists of the UK and Commonwealth at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, entitled “Arts and aesthetics in a globalising world” (2012), and at the University of Exeter, entitled “Symbiotic Anthropologies” (2015). Each chapter offers a unique method of working in the grey area between and beyond the categories of fiction and non-fiction, while creatively reflecting upon current methodological, ethical, and theoretical issues, in anthropology and cultural studies. This is an important book for undergraduate and post-graduate students of anthropology, cultural and media studies, art theory, and creative writing, as well as academic researchers in these fields.

Carl Leggo , Pauline Sameshima

Fiction (with its etymological connections to the Latin fingere, to make) is a significant way for researching and representing lived and living experiences. As fiction writers, poets, and education researchers, we promote connections between fictional knowing and inquiry in educational research. We need to compose and tell our stories as creative ways of growing in humanness. We need to question our understanding of who we are in the world. We need opportunities to consider other versions of identity. This is ultimately a pedagogic work, the work of growing in wisdom through education, learning, research, and writing. The real purpose of telling our stories is to tell them in ways that open up new possibilities for understanding and wisdom and transformation. So, our stories need to be told in creative ways that hold our attention, that call out to us, that startle us.

British Journal of Aesthetics

Karen Simecek

RELATED PAPERS

Anvar UMAROV

Teriya Ogden

Radinaalivia Sutrijingga

Miskolc Mathematical Notes

Ali Armandnejad

Journal of NeuroInterventional Surgery

The Journal of Chemical Physics

Stefan Reinsch

Victoria Vidal

Erolcan ÖZEROL

Revista Electrónica de LEEME

Rodrigo Montes Anguita

Tạp chí phát triển Khoa học và Công nghệ

Lịch Nguyễn

Ljubica Ivanović Bibić

dragos voicu

Estudios Sobre El Mensaje Periodistico

Concha E D O Bólos

Abdelhafid Chafi

Professional Development in Education

Aileen Kennedy

Advances in Analytical Chemistry of Scientific & Academic Publishing

Abdullahi Usman

Rev Méd IMSS

Rolando Neri-Vela

Applied Mathematics and Computation

md alim alim

2011 Proceedings IEEE INFOCOM

Mihaela van der Schaar

Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences

Friedrich Affolter

Wiadomości Lekarskie

Denys Novikov

BIO Web of Conferences

Manuel Feliciano

The Journal of Experimental Biology

Betty Sisken

The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation

Martin Sirois

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

How to Research a Book

by Sarah Gribble | 0 comments

I’m prepping for a new novel that I’m super excited about. My characters are floating around in my head, becoming more real as I write my first draft, and I have a decently detailed synopsis written.

My problem: I know next to nothing about my setting and my main character’s profession. Which means I need to do massive amounts of research. Yes, I have to conduct research for a book, even if it's a novel.

You might think you don’t need to do much research because you’re writing fiction. (Isn't fiction just making stuff up?!) You’d be wrong.

Your readers expect to be transported to your setting and to understand your characters so fully, they seem like real people. Little things like using the wrong jargon or having your main character wear the wrong type of bodice can jar your reader out of the story and cause them to lose respect for you as a writer. If they can’t trust you to get the facts right, why should they trust you to guide them through a story?

Like it or not, research is a writer's best friend. (Next to caffeine, anyway.) So let's talk about how to conduct research for a book.

The True Purpose of Research for Fiction

When you first start the research process for a novel, you’re going to be looking at the big picture. You want to get a general overview of the time period, location, and/or character profession. You want to immerse yourself in everything you can find that comes within your story's scope.

This isn’t because you’re going to regurgitate all that to your readers. It’s because you need to have a clear picture of what’s going on in order to successfully write your story. All of your research is for you so that you can translate your world to your reader.

It will also help speed up your writing process, since you'll know the details you need to include without getting bogged down in how something should work in your story.

Don't mistake this with the thought that you need to include everything you research in your book (especially if you're writing historical fiction, which can require more research than other genres).

Book research is a tool that should serve your story, not the other way around. You’re not writing an academic paper, so resist the urge to shove everything you’ve learned into your story. You’ll end up info dumping if you try.

Your story is the main purpose and your research should support it, not overwhelm it. Choose what you need to further the story and leave the rest.

How to Conduct Research for a Book

Okay, let's get to it! Here’s how to get started with researching your novel:

Lists are your friends

Because you’ll be dealing with a vast amount of (mostly useless) information, the first thing you need to do is get organized. Some fiction writers like to use Scrivener to keep track of their research. Others might use Evernote.

Really, the writing software you want to use is based on your preference of documenting subject matter.

It could be as simple as detailed notecards or thoughts in a journal.

Whatever method you use to research your own work, you'll want to make lists.

Do this for everything you need to look up. You don’t want to forget something hugely important and have to spend a lot of time in the middle of writing your novel to look it up.

In my case, my setting is on a small island and my main character is a commercial fisherman. I need to know island life, weather patterns, boat types, fishing jargon, etc. I have memoirs and nonfiction books about the area and the fishing industry. I’m reading them cover-to-cover, not because I’ll end up using all the information, but because I need to establish an overarching picture for myself .

If I can’t mentally place myself there, I can’t place my readers there.

Where can you collect these lists? Tons of places, some including:

- Local libraries (are also your friends)

- Field research (find someone who has had a personal experience in what you're writing)

- Search engines like Google (for setting, you might explore Google maps—just don't get too distracted and waste a ton of time here)

- Wikipedia (but make sure you fact check)

- Podcasts about what you're writing about

- Other books from bestselling authors (as long as you don't plagiarize content)

Establish a system

You need to be able to call up your research as needed, so establishing an organized, consistent system of keeping track of everything you’ve learned is a must.

Personally, since I spent so many years in school, I go with the standard method of taking notes (in a notebook that only serves my current project and nothing else) and then highlighting and sticky-noting facts I definitely want to use. There are plenty of note-taking apps out there if you'd rather not be so old school.

For fun, try establishing a system for a short story first. This decrease the pressure on trying out the same system for a longer creative writing work.

If the system works well for you, take it to the next level and use it to write a novella or novel.

Expand your idea of research

Don’t just scour the internet. Get a book. Better yet, get twelve. There’s no such thing as researching too much.

Talk to your librarian or a book seller (they’re magnificent at helping with this). Watch documentaries and YouTube videos. Look at pictures. Talk to people in person or online. Go to a museum. Read fiction novels that cover similar ground. Find all the information you can on your subject.

First-hand experience is always best, but don't worry if you can't afford a trip to France for your quirky French bookstore novel. You can go to a French restaurant. The taste of the food, the smells, and how the waiter pronounces the menu items are all fodder for your story.

Pay attention to details when you’re out and about. You never know what might inspire, fill in plot holes, or add an interesting tic to your character.

Stop researching

Once you have a solid overarching picture of your setting and your characters, stop researching and start writing. You can’t spend months researching without writing a word. That’s not writing. At some point, you have to put away the research and get moving on your novel.

You know you've researched enough when you already know the information you're reading in the umpteenth book you've checked out from the library.

(Hmm. Library again. A pattern, maybe? Seriously, ask your librarians for help.)

Remember how I said all this research was for you? Eventually, you'll have enough information. You have all that in your head (and hopefully in a nicely organized set of notes), so when you go to write, you’ll be able to recall details as you go along.

Your understanding of your setting, era, and character's profession is what will give you the ability to weave details seamlessly and organically into your story.

This goes for your first novel, up until your last one.

While it’s true you shouldn’t have to research anything major after you begin writing, you will find you need to look up some minor details as you delve into your story. There will always be some iota of information you don’t know you need until you need it. For instance, the most common types of knots fishermen use or the instruments on a surgical tray in an operating room.

These are things that are important to get right but are most likely not important to the flow of the story. Don't interrupt your writing flow to go back to researching for weeks on end.

When you come across the need to know something minor, make a note and keep writing . You can always look up small stuff later. Keep writing!

What's your favorite part of researching? What do you struggle with? Let me know in the comments !

Today I want you to do something a little different. I want you to think of a story you want to write. Any story, any genre, but it must be in a setting you don't know much (if anything!) about. Take fifteen minutes to brainstorm a list of things you'd need to research in order for that setting to come alive for your reader—and you!

Share your list in the comments and see if you can help your fellow writers think of anything else they need to look up!

Sarah Gribble

Sarah Gribble is the author of dozens of short stories that explore uncomfortable situations, basic fears, and the general awe and fascination of the unknown. She just released Surviving Death , her first novel, and is currently working on her next book.

Follow her on Instagram or join her email list for free scares.

Work with Sarah Gribble?

Bestselling author with over five years of coaching experience. Sarah Gribble specializes in working with Dark Fantasy, Fantasy, Horror, Speculative Fiction, and Thriller books. Sound like a good fit for you?

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- 5 Essential Traits You Will Need to Achieve Success as a Writer! - Writer's Motivation - […] Aside from being confident, you will need to be as meticulous as possible. This is because potential readers can…

- 10 Idiom Examples That Will Make Your Writing a Lot More Vibrant! - Writer's Motivation - […] Aside from being confident, you will need to be as meticulous as possible. This is because potential readers can…

- The Week in Links 11/16/18: Stan Lee, Detective Pikachu, Harry Potter - Auden Johnson - […] A NaNoWriMo Survival Boost 6 Tips for Writing Social Media Ad Copy That Converts Writing for Audiobook How to…

- Research Pitfalls, Solutions, and My New Process - Writing Mayhem - […] the first issue, Sarah Gribble of The Write Practice says that she will get an idea of what she…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Submit Comment

Join over 450,000 readers who are saying YES to practice. You’ll also get a free copy of our eBook 14 Prompts :

Popular Resources

Book Writing Tips & Guides Creativity & Inspiration Tips Writing Prompts Grammar & Vocab Resources Best Book Writing Software ProWritingAid Review Writing Teacher Resources Publisher Rocket Review Scrivener Review Gifts for Writers

Books By Our Writers

You've got it! Just us where to send your guide.

Enter your email to get our free 10-step guide to becoming a writer.

You've got it! Just us where to send your book.

Enter your first name and email to get our free book, 14 Prompts.

Want to Get Published?

Enter your email to get our free interactive checklist to writing and publishing a book.

EH -- Researching Short Stories: Strategies for Short Story Research

- Find Articles

- Strategies for Short Story Research

Page Overview

This page addresses the research process -- the things that should be done before the actual writing of the paper -- and strategies for engaging in the process. Although this LibGuide focuses on researching short stories, this particular page is more general in scope and is applicable to most lower-division college research assignments.

Before You Begin

Before beginning any research process, first be absolutely sure you know the requirements of the assignment. Things such as

- the date the completed project is due

- the due dates of any intermediate assignments, like turning in a working bibliography or notes

- the length requirement (minimum word count), if any

- the minimum number and types (for example, books or articles from scholarly, peer-reviewed journals) of sources required

These formal requirements are as much a part of the assignment as the paper itself. They form the box into which you must fit your work. Do not take them lightly.

When possible, it is helpful to subdivide the overall research process into phases, a tactic which

- makes the idea of research less intimidating because you are dealing with sections at a time rather than the whole process

- makes the process easier to manage

- gives a sense of accomplishment as you move from one phase to the next

Characteristics of a Well-written Paper

Although there are many details that must be given attention in writing a research paper, there are three major criteria which must be met. A well-written paper is

- Unified: the paper has only one major idea; or, if it seeks to address multiple points, one point is given priority and the others are subordinated to it.

- Coherent: the body of the paper presents its contents in a logical order easy for readers to follow; use of transitional phrases (in addition, because of this, therefore, etc.) between paragraphs and sentences is important.

- Complete: the paper delivers on everything it promises and does not leave questions in the mind of the reader; everything mentioned in the introduction is discussed somewhere in the paper; the conclusion does not introduce new ideas or anything not already addressed in the paper.

Basic Research Strategy

- How to Research From Pellissippi State Community College Libraries: discusses the principal components of a simple search strategy.

- Basic Research Strategies From Nassau Community College: a start-up guide for college level research that supplements the information in the preceding link. Tabs two, three, and four plus the Web Evaluation tab are the most useful for JSU students. As with any LibGuide originating from another campus, care must be taken to recognize the information which is applicable generally from that which applies solely to the Guide's home campus. .

- Information Literacy Tutorial From Nassau Community College: an elaboration on the material covered in the preceding link (also from NCC) which discusses that material in greater depth. The quizzes and surveys may be ignored.

Things to Keep in Mind

Although a research assignment can be daunting, there are things which can make the process less stressful, more manageable, and yield a better result. And they are generally applicable across all types and levels of research.

1. Be aware of the parameters of the assignment: topic selection options, due date, length requirement, source requirements. These form the box into which you must fit your work.

2. Treat the assignment as a series of components or stages rather than one undivided whole.

- devise a schedule for each task in the process: topic selection and refinement (background/overview information), source material from books (JaxCat), source material from journals (databases/Discovery), other sources (internet, interviews, non-print materials); the note-taking, drafting, and editing processes.

- stick to your timetable. Time can be on your side as a researcher, but only if you keep to your schedule and do not delay or put everything off until just before the assignment deadline.

3. Leave enough time between your final draft and the submission date of your work that you can do one final proofread after the paper is no longer "fresh" to you. You may find passages that need additional work because you see that what is on the page and what you meant to write are quite different. Even better, have a friend or classmate read your final draft before you submit it. A fresh pair of eyes sometimes has clearer vision.

4. If at any point in the process you encounter difficulties, consult a librarian. Hunters use guides; fishermen use guides. Explorers use guides. When you are doing research, you are an explorer in the realm of ideas; your librarian is your guide.

A Note on Sources

Research requires engagement with various types of sources.

- Primary sources: the thing itself, such as letters, diaries, documents, a painting, a sculpture; in lower-division literary research, usually a play, poem, or short story.

- Secondary sources: information about the primary source, such as books, essays, journal articles, although images and other media also might be included. Companions, dictionaries, and encyclopedias are secondary sources.

- Tertiary sources: things such as bibliographies, indexes, or electronic databases (minus the full text) which serve as guides to point researchers toward secondary sources. A full text database would be a combination of a secondary and tertiary source; some books have a bibliography of additional sources in the back.

Accessing sources requires going through various "information portals," each designed to principally support a certain type of content. Houston Cole Library provides four principal information portals:

- JaxCat online catalog: books, although other items such as journals, newspapers, DVDs, and musical scores also may be searched for.

- Electronic databases: journal articles, newspaper stories, interviews, reviews (and a few books; JaxCat still should be the "go-to" portal for books). JaxCat indexes records for the complete item: the book, journal, newspaper, CD but has no records for parts of the complete item: the article in the journal, the editorial in the newspaper, the song off the CD. Databases contain records for these things.

- Discovery Search: mostly journal articles, but also (some) books and (some) random internet pages. Discovery combines elements of the other three information portals and is especially useful for searches where one is researching a new or obscure topic about which little is likely to be written, or does not know where the desired information may be concentrated. Discovery is the only portal which permits simul-searching across databases provided by multiple vendors.

- Internet (Bing, Dogpile, DuckDuckGo, Google, etc.): primarily webpages, especially for businesses (.com), government divisions at all levels (.gov), or organizations (.org). as well as pages for primary source-type documents such as lesson plans and public-domain books. While book content (Google Books) and journal articles (Google Scholar) are accessible, these are not the strengths of the internet and more successful searches for this type of content can be performed through JaxCat and the databases.

NOTE: There is no predetermined hierarchy among these information portals as regards which one should be used most or gone to first. These considerations depend on the task at hand and will vary from assignment o assignment.

The link below provides further information on the different source types.

- Research Methods From Truckee Meadows Community College: a guide to basic research. The tab "What Type of Source?" presents an overview of the various types of information sources, identifying the advantages and disadvantages of each.

- << Previous: Find Books

- Last Updated: Nov 8, 2023 1:49 PM

- URL: https://libguides.jsu.edu/litresearchshortstories

- Our Mission

Making Research More Exciting Through Fiction Writing

Narrative writing that incorporates research can be a more engaging alternative to a classic research paper.

For many students, writing a research paper can be a dull task. A more exciting option is for students to write fictional narratives about their topics and to embed facts from their research. With this approach, students learn both the elements of fiction and the research process simultaneously.

Set Expectations

When planning the course, find or create a place in the curriculum where students could research specific topics. Either make a list of topics that you know will have enough age-appropriate information or require students to create a list of self-generated topics that are then approved by the teacher. Either way, student choice is crucial.

Set clear expectations about the dual purposes of this project: Students need to find lots of facts about their topic and then incorporate those facts into a short work of fiction. Students are often inspired by story-writing because so many ideas will come to them during the research process.

Set a low word limit for the short story, and require students to include a set number of facts within it. For example, for my middle school students, I set a maximum word count of 750 words, and I require a minimum of 20 interesting facts from their research.

Essentially, students have ongoing, built-in writing prompts. For example, if a student is researching orcas and comes across the fact that orcas can jump out of the water to snatch penguins or seals, they might be inspired to write an exciting—and true-to-life—penguin-snatching scene in their story.

The Research and Writing Process

Once students know the specific expectations, begin the research process. A few mini-lessons about research can help students set the parameters of their work. Talk with students about how to find good sources, why it’s important to use a variety of sources, and how to use keywords. Even if these lessons are just reminders, students will have a clearer sense of how to be efficient.

If your class doesn’t already have a note-taking system in place, set one up. For younger students, a mini-lesson on paraphrasing is probably in order. Ask students to paraphrase the relevant information they find during the research process in bulleted form, with each bit of information they find functioning as a “fact” they can use in their story. After each fact, have them include their source in parentheses—hyperlinked, if possible.

About halfway through the research process, students should begin drafting their stories. Make the transition from mini-lessons on researching to mini-lessons on writing short fiction. Students can alternate days of research and writing, or they can split the period and do research for half and writing for half.

The first fiction mini-lesson could be sharing and discussing an age-appropriate example of flash fiction in which the author manages to tell a compelling story with a satisfying ending in very few words. I tend to prioritize mini-lessons on creating and sustaining conflict, applying various methods of characterization, and using their authentic voice.

I discourage students from writing non-endings like “To be continued” or “It was all a dream!” because these are easy-outs from the difficult work of crafting a complete story. Ask them to imagine they are the reader and not the writer of their story: Would they find the ending satisfying or not?

Most important, throughout the drafting process, students should find creative ways to embed facts into their story. As they write, they underline or highlight the facts they’ve included. Help them find ways to sneak the facts into the story. For example, if a student is researching the geography of a state, he or she could use specific geographic features to describe the setting in the narrative.

Share Successes

To assess the projects, ask students to submit both their research notes and their stories. Create a simple rubric that includes all the skills from the mini-lessons, such as paraphrasing, source citing, and characterization. When the projects are complete, organize a listening party. Encourage students to listen on two levels: to enjoy the stories as stories and to identify the facts within them.

Whenever we successfully tap into students’ creativity, they naturally become more curious and see that they really do have interesting stories to tell.

Table of Contents

Tip 1: Start with Your Positioning and Outline

Tip 2: make a research plan, tip 3: ask the internet, tip 4: read books, tip 5: talk to experts, tip 6: collect survey data, tip 7: keep everything organized.

- Tip 8: Set a Deadline & Stop Early

Tip 9: Write the First Draft

How to conduct research for your book: 9 tips that work.

If you’re like many first-time nonfiction writers, you’ve probably wondered, “How do I research for my book?”

I get this question a lot, and there are plenty of tips I can share. But before I dive into it, I’m going to throw you a curveball:

Don’t assume you have to do research for your book.

Because the purpose of nonfiction is to help the reader solve a problem or create change in their life (or both) by sharing what you know. If you can do this without a lot of research, then don’t do research.

We’ve had many Authors who knew their topic so inside and out that they didn’t need research. That is perfectly fine. They still wrote incredible books.

When it boils down to it, there are only 2 reasons to do research for your book:

- You know enough to write the book, but you want to add sources and citations to make the book more persuasive to a specific audience.

- You don’t know enough, and you need to learn more to make the book complete.

We’ve had many Authors who–despite knowing their stuff–wanted to include additional data, expert opinions, or testimonials to ensure that readers would find their arguments credible. This is important to consider if you’re writing for a scientific or technical audience that expects you to cite evidence.

Likewise, we see many Authors who know their industry but have a few knowledge gaps they’d like to fill in order to make their arguments more robust.

In fact, that’s the whole key to understanding how much research you should do. Ask yourself:

What evidence does a reader need to believe your argument is credible and trustworthy?

Research can be complicated, though. Many Authors don’t know where to start, and they get bogged down in the details. Which, of course, derails the book writing process and stalls them–or worse, it stops them from finishing.

The bad news? There’s no “right way” to make a book research plan.

The good news? The basic research tips apply for either person.

In this post, I’ll give you 9 effective research tips that will help you build a stronger, more convincing book.

More importantly, these tips will also show you how to get through the research process without wasting time.

9 Research Tips for Writing Your Book

Don’t jump into research blindly. Treat it like any other goal. Plan, set a schedule, and follow through.

Here are 9 tips that will help you research effectively.

Before you start researching or writing, you need to figure out two main things: your audience and your message.

This is called book positioning , and it’s an essential part of the book writing process.

Your job as an Author is to convince readers that your book will help them solve their problems.

Every piece of research you include in the book–whether it’s a survey, pie chart, or expert testimonial–should help you accomplish that.

Once your positioning is clear, you can put together your book outline.

Your outline is a comprehensive guide to everything in your book, and it is your best defense against procrastination, fear, and all the other problems writers face . It’s crucial if you don’t want to waste time on research you don’t need.

With an outline, you’ll already know what kind of data you need, where your information gaps are, and what kinds of sources might help you support your claims.

We’ve put together a free outline template to make the process even easier.

All this to say: without solid positioning and a comprehensive outline, you’ll wander. You’ll write, throw it away, write some more, get frustrated, and eventually, give up.

You’ll never finish a draft, much less publish your book .

If you don’t know your subject well enough to figure out your positioning and make a good outline, it means you don’t know enough to write that book—at least not right now.

Your plan will vary widely depending on whether you are:

- An expert who knows your field well

- Someone who needs to learn more about your field before writing about it

The majority of you are writing a book because you’re experts. So most of the information you need will already be in your head.

If you’re an expert, your research plan is probably going to be short, to the point, and about refreshing your memory or filling small gaps.

If you’re a non-expert, your research plan is probably going to be much longer. It could entail interviewing experts, reading lots of books and articles, and surveying the whole field you are writing about.

The outline should highlight those places where your book will need more information.

Are there any places where you don’t have the expertise to back up your claims?

What key takeaways require more evidence?

Would the book be stronger if you had another person’s point of view?

These are the kinds of gaps that research can fill.

Go back through your outline and find the places where you know you need more information. Next to each one, brainstorm ways you might fulfill that need.

For example, let’s say you’re writing a book that includes a section on yoga’s health benefits. Even if you’re a certified yoga instructor, you may not know enough physiology to explain the health benefits clearly.

Where could you find that information?

- Ask a medical expert

- A book on yoga and medicine

- A website that’s well respected in your field

- A study published in a medical journal

You don’t have to get too specific here. The point is to highlight where you need extra information and give yourself leads about where you might find it.

The kinds of research you need will vary widely, depending on what kind of nonfiction book you’re writing.

For example, if you’re giving medical advice for other experts, you’ll likely want to substantiate it with peer-reviewed, professional sources.

If you’re explaining how to grow a company, you might refer to statistics from your own company or recount specific anecdotes about other successful companies.

If you’re writing a memoir, you won’t need any quantitative data. You might simply talk with people from your past to fill in some gaps or use sources like Wikipedia to gather basic facts.

Different subject matter calls for different sources. If you’re having trouble figuring out what sources your subject needs, ask yourself the same question as above:

Ask yourself what evidence does a reader need to believe your argument is credible and trustworthy?

Generally speaking, an expert can do their research before they start writing, during, or even after (depending on what they need).

If you’re a non-expert, you should do your research before you start writing because what you learn will form the basis of the book.

It may sound obvious, but the internet is a powerful research tool and a great place to start. But proceed with caution: the internet can also be one of the greatest sources of misinformation.

If you’re looking for basic info, like for fact-checking, it’s fantastic.

If you’re looking for academic information, like scientific studies, it can be useful. (You might hit some paywalls, but the information will be there.)

If you’re looking for opinions, they’ll be abundant.

Chances are, though, as you look for all these things, you’re going to come across a lot of misleading sources—or even some that straight-up lie.

Here are some tips for making sure your internet research is efficient and effective:

- Use a variety of search terms to find what you need. For example, if you’re looking for books on childhood development, you might start with basic terms like “childhood development,” “child psychology,” or “social-emotional learning.”

- As you refine your knowledge, refine your searches. A second round of research might be more specific, like “Piaget’s stages of development” or “Erikson’s psychosocial theories.”

- Don’t just stop with the first result on Google. Many people don’t look past the first few results in a Google search. That’s fine if you’re looking for a recipe or a Wikipedia article, but the best research sources don’t always have the best SEO. Look for results that seem thorough or reputable, not just popular.

- Speaking of Wikipedia, don’t automatically trust it. It can be a great place to start if you’re looking for basic facts or references, but remember, it’s crowd-sourced. That means it’s not always accurate. Get your bearings on Wikipedia, then look elsewhere to verify any information you’re going to cite.

- Make sure your data is coming from a reputable source. Google Scholar, Google Books, and major news outlets like NPR, BBC, etc. are safe bets. If you don’t recognize the writer, outlet, or website, you’re going to have to do some digging to find out if you can trust them.

- Verify the credentials of the Author before you trust the site. People often assume that anything with a .edu domain is reputable. It’s not. You might be reading some college freshman’s last-minute essay on economics. If it’s a professor, you’re probably safe.

Using a few random resources from the internet is not equivalent to conducting comprehensive research.

If you want to dive deeper into a topic, books are often your best resources.

They’re reliable because they’re often fact-checked, peer-reviewed, or vetted. You know you can trust them.

Many Authors are directly influenced by other books in their field. If you’re familiar with any competing books, those are a great place to start.

Use the internet to find the best books in each field, and then dive into those.

Your book will have a different spin from the ones already out there, but think of it this way: you’re in the same conversation, which means you’ll probably have many of the same points of reference.

Check out the bibliographies or footnotes in those books. You might find sources that are useful for your own project.

You might want to buy the books central to your research. But if you aren’t sure if something’s going to be useful, hold off on hitting Amazon’s “one-click buy.”

Many Authors underestimate the power of their local libraries. Even if they don’t have the book you’re looking for, many libraries participate in extensive interlibrary loan programs. You can often have the books you need sent to your local branch.

Librarians are also indispensable research resources. Many universities have subject-specific research librarians who are willing to help you find sources, even if you aren’t a student.

Research doesn’t always require the internet or books. Sometimes you need an answer, story, or quotation from a real person.

But make sure you have a decent understanding of your field BEFORE you go to experts with your questions.

I’m an expert at writing nonfiction books, so I speak from personal experience. It’s annoying as hell when people come to you with questions without having done at least a little research on the topic beforehand—especially when you already have a 3,000 word blog post about it.

Experts love it when you’ve done some research and can speak their language. They hate it when you ask them to explain fundamentals.

But once you find a good expert, it condenses your learning curve by at least 10x.

To figure out who you need to talk to, think about the kind of nonfiction book you’re writing.

Is it a book about your own business, products, or methods? You may want to include client stories or testimonials.

In Driven , Doug Brackmann relied on his experience with clients to teach highly driven people how to master their gifts.

Is it a book that requires expert knowledge outside your own area of expertise (for example, a doctor, IT specialist, lawyer, or business coach)? You might want to ask them to contribute brief passages or quotations for your book.

Colin Dombroski did exactly that for his book The Plantar Fasciitis Plan . He consulted with various colleagues, each of whom contributed expert advice for readers to follow.

It’s much easier to contact people who are already in your network. If you don’t personally know someone, ask around. Someone you already know may be able to connect you with the perfect expert.

If that doesn’t work out, you can always try the cold call method. Send a polite email that briefly but clearly explains what your book is about and why you’re contacting them.

If you do this, though, do your research first. Know the person’s name. Don’t use “To whom it may concern.” Know their specialty. Know exactly what type of information you’re seeking. Basically, know why they are the person you want to feature in your book.

Some Authors like to collect surveys for their books. This is very optional, and it’s only applicable in certain books, so don’t assume you need this.

But if you want to include a section in your book that includes how people feel about something (for example, to back up a point you’re making), you might want to have survey data.

You might have access to data you can already cite. The internet is full of data: infographics, Pew data, Nielsen ratings, scholarly research, surveys conducted by private companies.

If you don’t have access to data, you can conduct your own surveys with an online platform like SurveyMonkey. Here’s how:

- Consider your research goals. What are you trying to learn?

- Formulate the survey questions. Most people prefer short, direct survey questions. They’re also more likely to answer multiple-choice questions.

- Invite participants. If you want a reliable survey, it’s best to get as many participants as possible. Surveying three family members won’t tell you much.

- Collect and analyze the data.

That will work for more informal purposes, but surveys are a science unto themselves. If you require a lot of data, want a large sample size, or need high statistical accuracy, it’s better to hire pros. Quantitative data is more effective and trustworthy when it’s properly conducted.

Don’t go overboard with statistics, though. Not all books need quantitative data. There are many other ways to convince readers to listen to your message.

Organize your research as you go. I can’t stress this enough.

If you research for months on end, you might end up with dozens of articles, quotations, or anecdotes. That’s a lot of material.

If you have to dig through every single piece when you want to use something, it’ll take you years to write.

Don’t rely on your memory, either. Three months down the line, you don’t want to ask, “Where did I find this piece of information?” or “Where did that quotation come from?”

I suggest creating a research folder on your computer where you collect everything.

Inside the main folder, create subfolders for each individual chapter (or even each individual subsection of your chapters). This is where your outline will come in handy.

In each folder, collect any pdfs, notes, or images relevant to that section.

Every time you download or save something, give the file a clear name.

Immediately put it into the correct folder. If you wait, you might not remember which part of your book you found it useful for.

Also, be sure to collect the relevant citation information:

- Author’s name

- Title of the book, article, etc.

- The outlet it appeared in (e.g., BBC or Wired) or, if it’s a book, the publisher

- The date it was published

- The page number or hyperlink

If you have photocopies or handwritten notes, treat them the same way. Label them, file them, and add the necessary citation information. This will save you a lot of time when you sit down to write.

Some Authors use programs like Scrivener or Evernote to keep track of their research. I personally use the software program Notion, which is similar to Evernote.

These programs allow you to collect references, notes, images, and even drafts, all in one convenient place.

They save you from having to create your own digital organizational system. They also make it easier to consult documents without opening each file individually.

Once you’ve got a system in place, don’t forget: back up your data. Put it on the cloud, an external hard drive, or both. There’s nothing worse than spending hours on research just to have it disappear when your computer crashes.

All of this takes time, and it may seem tedious. But trust me, it’s a lot more tedious when you’re racing toward your publication deadline, and you’re hunting down random data you quoted in your book.

Tip 8: Set a Deadline & Stop Early

Research is one of the most common ways Authors procrastinate.

When they’re afraid of writing or hit roadblocks, they often say, “Well, I just need to do a little more research…”

Fast-forward two years, and they’re still stuck in the same spiral of self-doubt and research.

Don’t fall into that trap. Learn when to stop.

When I’m writing, I set a research deadline and then stop EARLY. It’s a great way to beat procrastination , and it makes me feel like I’m ahead of the curve.

Here’s the thing: there’s always going to be more information out there. You could keep researching forever.

But then you’d never finish the book—which was the point of the research in the first place.

Plus, excessive research doesn’t make better books . No one wants to read six test cases when one would have worked.

You want to have enough data to convincingly make your case, but not so much that your readers get bogged down by all the facts.

So how will you know when you’ve done enough?

When you have enough data, anecdotes, and examples to address every point on your outline.

Your outline is your guide. Once it’s filled in, STOP .

Remember, the goal of data is to support your claims. You’re trying to make a case for readers, not bludgeon them with facts.

If you feel like you have to go out of your way to prove your points, you have 1 of 2 problems:

- You’re not confident enough in your points, or

- You’re not confident enough in your readers’ ability to understand your claims.

If you’re having the first problem, you may need to go back and adjust your arguments. All the research in the world won’t help support a weak claim.

If you’re having the second problem, ask yourself, If I knew nothing about this subject, what would it take to convince me? Follow through on your answer and trust that it’s enough.

When you think you have enough research, start writing your vomit draft.

If it turns out you’re missing small pieces of information, that’s okay. Just make a note of it. Those parts are easy to go back and fill in later.

Notice: I said “later.” Once you start writing, stop researching.

If you stop writing your first draft to look for more sources, you’ll break the flow of your ideas.

Research and writing are two completely different modes of thinking. Most people can’t switch fluidly between them.

Just get the first draft done.

Remember, the first draft is exactly that—the first draft. There will be many more versions in the future.

It’s okay to leave notes to yourself as you go along. Just be sure to leave yourself a way to find them easily later.

I recommend changing the font color or highlighting your comments to yourself in the draft. You can even use different colors: one for missing data and another for spots you need to fact-check.

You can also use the “insert comment” feature on Microsoft Word, Google Docs, or any other writing software you prefer.

Another useful tip is to simply type “TK.” There’s no word in the English language where those two letters appear together. That means, when you’re ready to go back through your draft, you can use the “Find” option (Control+F). It will take you back to all the spots you marked.

Whatever method you choose, don’t stop writing.

Also, don’t worry about how “good” or “bad” it is at this point. No one ever wrote an amazing first draft. Not even bestselling Authors.

Just keep at it until you have a complete first draft.

That won’t be hard because you won’t be missing any huge pieces. The whole point of the outline was to zero in on exactly what you want to write for the exact audience you want to reach. If you followed that outline when you researched, you’ll be able to stay on track during the writing process.

The Scribe Crew

Read this next.

How to Choose the Best Book Ghostwriting Package for Your Book

How to Choose the Best Ghostwriting Company for Your Nonfiction Book

How to Choose a Financial Book Ghostwriter

How Researchers Are Using Fiction to Make Their Reports Accessible to the Public

"Knowledge shouldn't belong to the few who have highly specialized education but must be opened up for review and discussion among the many."

Most research reports are about as interesting to read as car manuals or insurance plans. They're long, boring, inaccessible, jargon-filled and impossible to make sense of. This is how most people feel about research articles across different fields -- medicine, health, psychology, education and so forth -- and with good reason. Honestly, who among us actually reads this stuff?

Here's the issue: because research is too boring and too difficult to read, very few people actually read it. The problem is that much of the research we're not reading is impacting us, or could. Moreover, we may want to be involved in how this information is used or what research receives funding and attention, but it's so inaccessible that we're uninvolved.

In recent years there has been a big push to make research findings more available to the public. The public has become increasingly engaged and aware of a myriad of health and social issues (as a result of Internet-based knowledge sharing). Simultaneously, the hierarchical structure of academic and research institutions has been challenged (with people frustrated at the idea of researchers in 'ivory towers' who seem out of touch and cut off from the communities in which they are enmeshed). As a result, there has been a movement towards using fiction as a vehicle for representing research findings. If this sounds far-fetched, it really isn't at all. Remember, there is a historical precedent for trying to share information by telling good stories. For instance, in recent decades reporters have shifted their writing style to draw on creative nonfiction as a way of making newspaper articles more interesting. Using literary tools to present research findings also makes a lot of sense for several reasons.

First, people like fiction. In fact, most of us like it so much that we elect to spend our free time enjoying it -- at the movies, theatre or reading novels. Let's face it, two of the most crowded places on any given Saturday are your local movie theater and big chain bookstore (which now include coffee shops because people like to hang out there for as long as possible). The turn to fiction as a way of sharing research findings taps into what many people already elect to spend their time doing. This is also important because exposure to research studies promotes learning (we read studies and learn more about something). Learning isn't a passive activity, and it doesn't have to be miserable either. Learning should be engaged and joyful.

Second, conducting research is resource-intensive. It takes money, time and energy. By using fiction as one way to represent the product of that research, our effort becomes more worthwhile because the distribution of the research findings is maximized.

Third, there is an ethical mandate for making research more accessible to the public. Knowledge shouldn't belong to the few who have highly specialized education but must be opened up for review and discussion among the many. This is a foundational principle guiding the structure of our society from our public school system to public libraries to our democratic political system. We need to find ways to bring sophisticated research studies into the public domain as well.

Researchers across different fields are developing ways to use fiction in different mediums in order to reach broad and diverse audiences and to include more stakeholders in the research process.

For example, healthcare researchers have created theatrical productions about topics ranging from living with mental illness to philosophical questions surrounding genetic testing. When these plays are performed in hospitals, schools and other community spaces, audience members are exposed to new learning, prompted to engage in reflection and/or invited to engage in productive debates about issues such as medical ethics, harmful stereotypes, caregiving, health policy, and medical technology and morality (Jeff Nisker chronicles this work in his 2012 book From Calcedonies to Orchids: Plays Promoting Humanity in Health Policy ).

For another example, social scientists are writing novels informed by their research. They are drawing on popular genres like "chick-lit" and mystery in order to share their knowledge about topics ranging from corporate greed to eating disorders to the psychology of dysfunctional relationships and self-esteem. For instance, Sense Publishers, an academic press in the field of education research, is publishing the Social Fictions series which exclusively publishes books written in literary forms but informed by scholarly work. Although the first series of its kind, one imagines there will be more.

Social research is making its way to the silver screen too. Recently the New York Times online edition featured a story about a three-year study out of Bournemouth University in England called "The Gay and Peasant Land Project." Led by sociologist Kip Jones, researchers studied gay identity in older people living in rural areas. Jones partnered with film director Josh Appignanesi to produce the short film Rufus Stone which has since been screened at various festivals and received numerous accolades.

It is clear from even this cursory glance that researchers are developing creative ways to use fiction to make their research available for public consumption and engagement and this seems like a very good thing for all of us.

Follow Patricia Leavy, PhD on Twitter .

Visit Patricia's website: here

Books by Patricia Leavy:

Buy " Fiction as Research Practice: Short Stories, Novellas, and Novels" here .

Buy "Essentials of Transdisciplinary Research: Using Problem-Centered Methodologies" here .

Buy "Method Meets Art: Arts-based Research Practice" here .

- art and science

- interdisciplinarity

- patricia leavy

- science writing

RECOMMENDED FOR YOU

Investing in the Creativity Sector

The Big Lesson of a Little Prince: (Re)capture the Creativity of Childhood

The Art-Research Nexus: An Interview with Dr. Patricia Leavy

A Simple Practice Scheduling Hack That Couldn't Possibly Be as Effective as It Seems

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

How Does Fiction Reading Influence Empathy? An Experimental Investigation on the Role of Emotional Transportation

P. matthijs bal.

1 Department of Management & Organization, VU University Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Martijn Veltkamp

2 FrieslandCampina, Deventer, The Netherlands

Conceived and designed the experiments: PMB MV. Performed the experiments: PMB MV. Analyzed the data: PMB. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: PMB MV. Wrote the paper: PMB MV.

The current study investigated whether fiction experiences change empathy of the reader. Based on transportation theory, it was predicted that when people read fiction, and they are emotionally transported into the story, they become more empathic. Two experiments showed that empathy was influenced over a period of one week for people who read a fictional story, but only when they were emotionally transported into the story. No transportation led to lower empathy in both studies, while study 1 showed that high transportation led to higher empathy among fiction readers. These effects were not found for people in the control condition where people read non-fiction. The study showed that fiction influences empathy of the reader, but only under the condition of low or high emotional transportation into the story.

Introduction