Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Download Free PDF

The Impact of Job Satisfaction on Job Performance: An Empirical Analysis

Employee attitudes are important to management because they determine the behavior of workers in the organization. The commonly held opinion is that “A satisfied worker is a productive worker”. A satisfied work force will create a pleasant atmosphere within the organization to perform well. Hence job satisfaction has become a major topic for research studies. The specific problem addressed in this study is to examine the impact of job satisfaction on performance. It considered which rewards (intrinsic and extrinsic) determine job satisfaction of an employee. It also considered influence of age, sex and experience of employees on level of job satisfaction. In addition it investigated in most satisfying event of an employee in the job, why employees stay and leave the organization. Data were collected through a field survey using a questionnaire from three employee groups, namely Professionals, Managers and Non-managers from twenty private sector organizations covering five industries...

Related papers

Employee attitudes are important to management because they determine the behaviour of workers in the organization. The commonly held opinion is that “A satisfied worker is a productive worker”. A satisfied work force will create a pleasant atmosphere within the organization to perform well. It investigated the most satisfying event of an employee in the job, why employees stay and leave the organization. Job satisfaction is a general attitude towards one’s job, the difference between the amount of reward workers receive and the amount they believe they should receive. Employee is a back bone of every organization, without employee no work can be done. So employee’s satisfaction is very important. Employees will be more satisfied if they get what they expected, job satisfaction relates to inner feelings of workers. Key words: Job satisfaction, Rewards, Effort, Performance INTRODUCTION The correlation between the Job

Employee attitude is very important for management to determine the behavior of workers in the organization. The usually judgment about employees is that " A satisfied worker is a productive worker ". If employees are satisfied then it will create a pleasant atmosphere within the organization to perform in a better and efficient manner, therefore, job satisfaction and its relation with organizational performance has become a major topic for research studies. The specific problem covered in this study is to scrutinize the impact of job satisfaction on organizational performance. It considered which rewards (intrinsic and extrinsic) determine job satisfaction of an employee and its relation with organizational performance. It also reviewed the influence of age, sex and experience of employees on level of job satisfaction. It also covered and investigated different events which can satisfy the employees on jobs, their retention in the job, and why employees stay and leave the organization. Data were collected through conducting detailed field survey using questionnaires from different employee (exit interview of outgoing employees) groups like management, senior managers, managers, professionals and support staff from five profit/non-profit sector organizations. The data analysis shows that there exists positive correlation between job satisfaction and organizational performance. Introduction Job satisfaction of employees plays a very vital role on the performance of an organization. It is essential to know as to how employees can be retained through making them satisfied and motivated to achieve extraordinary results. Target and achievement depends on employee satisfaction and in turn contribute for organizational success and growth, enhances the productivity, and increases the quality of work.

Review of Behavioral Aspect in Organizations and Society, 2019

Basically, performance is something that is individual because each employee has a different level of ability to do their jobs. Performance depends on the combination of ability, effort, and opportunity obtained. Employee performance is capital for companies to survive and develop in responding to business and business competition today, advanced and developing companies are very dependent on reliable human resources so that the output is high performance on employee performance which will later affect the company's performance. However, it is not easy to maintain and improve employee performance. There are many factors that can affect performance. Many employee turnovers occur due to a lack of satisfaction with work. Employee performance is very dependent on the value of employee satisfaction in the workplace. The fulfillment of employee rights greatly affects the performance of the organization. So, in this study the focus of the study would like to see the extent of the influ...

The research reported in this thesis was on “Effects of job satisfaction on employee‟s performance”. The purpose of research was to study the various factors that have been significant in determining employee performance and their importance with respect to the employees of Pakistan. The secondary data was collected by Internet and also from the material printed by different Scholars from all over the world. The primary data was gathered by floating questionnaires in Hassan leather industry Sheikhupura, Pakistan. SPSS was applied to analyze the gathered information through running Correlation tests on the variables in the study. The reliability of the data was measured with the help of the Cronbach‟s Alpha value which too was calculated using the SPSS software. The findings provided an insight and estimation towards the impact of financial and Non-Financial reward system on employee‟s performance. All the variables have been found to be significant in determining employee‟s performa...

In today's increasing competitive environment, organizations recognize the internal human element as a fundamental source of improvement. On one hand, managers are concentrating on employees' wellbeing, wants, needs, personal goals and desires, to understand the job satisfaction. And on the other hand, managers take organizational decisions based on the employees' performance. The purpose of this study is to identify the factors influencing job satisfaction and the determinants of employee performance, and accordingly reviewing the relationship between them. This study is an interpretivist research that focuses on exploring the influence of job satisfaction on employee performance and vice, the influence of employee performance on job satisfaction. The study also examines the nature of the relationship between these two variables. The study reveals the dual direction of the relationship that composes a cycle cause and effect relationship, so satisfaction leads to performance and performance leads to satisfaction through number of mediating factors. Successful organizations are those who apply periodic satisfaction and performance measurement tests to track the level of these important variables and set the corrective actions.

Job satisfaction or employee satisfaction is a measure of the level of satisfaction of workers with their type of work which is related to the nature of their job duties, the results of the work achieved, the form of supervision obtained and the feeling of relief and liking for the work they are engaged in. Job satisfaction is an individual thing because each individual will have different levels of satisfaction according to the values that apply in each individual. This study is a qualitative research with a case study approach. Data collection was carried out by means of semi structured interviews to 10 staff working in private universities in Jakarta. Interview was also conducted with 2 HRD directors to dig deeper the efforts to provide job satisfaction which can improve employee performance. The results of this study indicate that job satisfaction has a big role in improving the quality of employee performance.

http://www.scie.org.au/ Abstract: The purpose of this paper is to discuss on the concept of job satisfaction and how job satisfaction can make impact on the performance of employees in an organization. The paper will be limited to the positive and negative effects of Job satisfaction. Secondly, the literature review will discuss the relationship between employee motivation, job satisfaction and employee performance

Purpose: To investigates the causes of job satisfaction among the employees of different organizations and how can maximize the performance of employees through job satisfaction. Design/ Methodology - Questionnaires were designed and distributed to all the employees of different organization. This measures perceived levels of job satisfaction amongst the employees of organizations and potential effects of job satisfaction on the performance of employees. Practical implications-The findings of this research emphasis on organization culture, work place conditions and job rank in order to optimize the performance of the employees through job satisfaction. There is also a need to undertake longitudinal research to investigate Findings: Findings suggested that there is a positive relationship exists between stress, time management and Family conflict problems. Increase in lack of support from family increase the stress level of a student similarly if a student could not manage its time this also increase the stress of a student. Research limitations- The research was carried out in five organizations and therefore results cannot be generalized to cover the whole organization sector. Value-This research paper highlights the causes of job satisfaction and their positive impacts on employee’s performance. Key Words- Job satisfaction, Organization culture, Job rank, Work place conditions.

The optimistic attitude of an employee’s experience based on their desired result is acknowledged as job satisfaction. This shows how the expectations of the employees for job are fulfilled in comparison to the veracity of their job. There are six important facets of job satisfaction and these are- Salaries, Promotion opportunities, Supervision, Nature of work and Colleagues. The objective of this study is to identify the factors that affect the job satisfaction of employees and to analyze the impact of compensation, organizational policy, working condition, job stress and promotion opportunities on job satisfaction of employees. The findings of the study suggest that the taken factors have explained the job satisfaction and the policy framers and managers have to think about inclusion of the factors that affect satisfaction to enhance their business. The study suggests that working condition, organizational policy and strategies, promotion, job stress and compensation package are k...

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

Advances in economics, business and management research, 2022

The Relationship between Job Satisfaction and Individual Performance, 2018

Contemporary Economics, 2014

International Journal of Education, Modern Management, Applied Science & Social Science, 2021

Journal of Human Resources Management Research, 2019

Asia Pacific Journal of Management and Education

Journal of emerging technologies and innovative research, 2021

Psychological Bulletin, 2001

European Journal of Business and Management, 2011

Related topics

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Corpus ID: 167015654

THE IMPACT OF JOB SATISFACTION ON JOB PERFORMANCE: AN EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS

- D. K. S. Navale

- Published 1 June 2008

- Business, Psychology

Figures and Tables from this paper

152 Citations

A study on the impact of job satisfaction on job performance of employees working in automobile industry, punjab, india, impact of job satisfaction on job performance, analysis of the effect of individual characteristics, employees’ competency and organizational climate on job satisfaction and employees’ performance at a state-owned trading company in indonesia, job satisfaction, employee loyalty and job performance in the hospitality industry: a moderated model, the impact of perceived organizational support program on employee performance in the presence of job satisfaction, an analysis on the relationship between job satisfaction and work performance among academic staff in malaysian private universities, the impact of employee job satisfaction towards employee job performance at pt.y.

- Highly Influenced

Job satisfaction of garments sector employees in Bangladesh

The determinants of organizational commitment with job satisfaction as an intervening variable, employee job satisfaction and organizational performance : an insight from selected hotels in lagos nigeria, 21 references, tenure, commitment, and satisfaction of college graduates in an engineering firm, sources of job motivation and satisfaction among british and nigerian employees, one more time: how do you motivate employees, effects of inequity on job satisfaction and self-evaluation in a national sample of african-american workers., behaviour in organizations, behaviour in organizations, management: tasks, responsibilities, practices, the effect of performance on job satisfaction, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

The Impact of Work Environment on Job Satisfaction

Nursing is challenging work. Burnout, dissatisfaction, disengagement, as well as exodus from the profession are rampant, and COVID-19 has amplified these issues. Although nurse leaders cannot change the work, they can create work environments that support nurse satisfaction, enjoyment, and meaning at work. A literature review on work environment and job satisfaction conducted pre-COVID for a dissertation project revealed several factors that support healthy work environments. This article defines and describes the qualities of both unhealthy and healthy work environments, discusses the impact they have on employees, and offers suggestions for nurse leaders to improve the work environment in their organization.

- • The psychosocial work environment is created by the interactions of staff and leadership and impacts how people behave and how they feel about their work.

- • Work environment and the experience one has at work impact employee health, well-being, and satisfaction.

- • Managers play a key role in creating and supporting the psychosocial work environment.

Health care is challenging work; it is emotionally and physically demanding. The environment within which work is performed can either support or hinder productivity and worker health. Toxic and unhealthy work environments create negative outcomes for staff, management, and the organization, as well as the community at large because the individual returns to the community following interactions in the work environment. Facing escalating suicide rates, burnout, turnover, and exodus from health care professions, leaders seek new ways of managing staff to support personal and professional well-being.

COVID-19 has amplified and intensified these issues, especially within the nursing profession. The pandemic has shined a spotlight on the problems faced by nursing professionals and the damage the problems cause physically, mentally, emotionally, and spiritually. Strategies for improving the nursing work environment are more important than ever before.

Although nurse leaders cannot necessarily change the work, they can behave in ways that support the workforce by creating safe, healthy work environments where all staff can be their best, be productive, and thrive. Managers play a key role in shaping the work environment through the procedures they implement and how they behave as a leader. A literature review conducted pre-COVID on work environment and job satisfaction revealed several factors that support a healthy work environment. Nurse leaders can use this information to inform decisions that will shape the future of health care today by creating work environments that support staff well-being and increase employee engagement and organizational commitment.

The Demands of the Work

Health care workers must create a safe space for patients to heal and improve. Because the nature of nursing service work is about caring for people, there is great personal responsibility for providing good, high quality service; connecting with patients; and caring for patient well-being. 1 High workloads, increased acuity, and emotional demands for caring for other’s well-being places physical and emotional demands on staff. Because nursing professionals typically assume great responsibility in providing quality care, they often put the needs of others first and do whatever is necessary to help the patient. This often means working long hours with little opportunity to rest and recover.

The nature of health care places staff at risk due to the stressful situations faced daily. Combine the normal demands of health care service with a lack of teamwork, poor communication, bullying, lateral violence, lack of support from leadership, equipment issues, a blaming and fearful culture, an inability to share one’s expertise or make decisions, and a work environment that discourages free expression of ideas and concerns, and this becomes a recipe for disaster.

Work Environment Defined

The work environment is the space that we create within which people come together to perform their work and achieve outcomes. It’s how we experience our work together. Also known as psychological climate, the work environment causes a psychological impact on the individual’s well-being. 2 The person–environment interaction determines the psychological and social dimensions of that environment, which then influences how one behaves in that environment. 3 This is an important definition because how the individual behaves in the environment and the reactions to that behavior then determines how the environment supports continued actions within that environment.

Nursing Job Satisfaction

Feelings of satisfaction or dissatisfaction occur in response to the individuals’ experience within the environment. In other words, satisfaction is an emotional response to the job and results from mentally challenging and interesting work, positive recognition for performance, feelings of personal accomplishment, and the support received from others. 4 This corresponds with the research on burnout, which is contrary and includes cynicism, exhaustion, and inefficacy. 5 Researchers found burnout to be a function of factors within the organizational context including work environment and leader effectiveness. 6 Whether positive or negative, research concludes that leader effectiveness and work environment affect employee outcomes.

The Impact of the Work Environment

As social beings, the environment created by the interactions of staff and leadership impacts how people behave and how they feel about their work. The experience people have at work impacts their personal well-being as well as job satisfaction. The occupational health movement of the 1960s grew from a need to explore the environmental hazards that created dangerous conditions for workers and to provide adequate safety interventions for protecting employees. 7 Over the past few decades, much research has focused on the psychosocial impact of the work environment on individual health and well-being.

The psychosocial work environment encompasses those factors that impact individuals and contribute to worker health, including both individual factors and the social work environment. Psychosocial factors include work demands; work organization including influence, freedom, meaning of work, and possibilities for development; interpersonal relations such as leadership and coworkers, a sense of community, role clarity, feedback, and support; and individual health and personal factors, including one’s ability to cope and family supports. 8 All these factors come together to create a space within which people interact and perform. Depending on how these elements support or hurt the individual determines the outcomes to that individual and how effectively they perform.

The pandemic has forced people to explore their personal resources for well-being and resilience and implement self-care strategies. People are taking more of an interest in health affirming activities. Family time has a different meaning today and people are re-exploring their priorities. Restorative practices have been found to lessen the sufferings, anxieties, and concerns generated in the workplace and provide inner peace and spiritual support. 9 Assuming responsibility for one’s health and well-being is important to being a contributing member of the workforce and to society at large. Managers must find ways to support these efforts as part of life at work.

Contributions to and Costs of Unhealthy Work Environments

Several factors contribute to a negative work environment. Traditionally, poor salaries and working conditions, and a lack of respect for nurses have led to high turnover and an increase in nurses leaving the profession. 10 Other factors include the lack of support, being short staffed, and an increased workload. 11 Lateral violence, bullying, and abuse by coworkers and physicians, as well as ineffective responses to such incidents by leadership, cause job strain, turnover, and exodus from the profession. 12

Much research has been done on bullying and its impact on the individuals involved, the organization, as well as the quality of patient care. Researchers found these negative behaviors led to increased errors, decreased quality, absenteeism, lost productivity, and turnover. 12 As the profession of nursing is already struggling to retain the nursing workforce and attract needed newcomers, creating a work environment that is supportive, satisfying, and one where people feel a sense of belonging is essential.

The stress and strain of work has been linked to physical and mental health issues. Unhealthy work environments lead to increased use of sick time, lost productivity, turnover, increased cost to care provision, and strain felt in personal relationships. 13 The costs in terms of absenteeism, turnover, and lost productivity are estimated in the billions of dollars annually. 14

Nurse leaders play a key role in creating work environments where people feel safe by implementing procedures for minimizing bullying and lateral violence and facilitating harmonious relationships by supporting respectful interactions. 12 , 13 , 15 Left unattended, the cycle of bullying and bad behavior is perpetuated as nurses move into academia from the bedside and continue the behaviors. 15 Although one of the toughest things to do as a leader, and the most time-consuming, upholding expectations and following through on such procedures is critical for creating a supportive and safe work environment.

Qualities of a Healthy Work Environment and Its Impact on Employee Outcomes

A healthy work environment is described as one where people are valued, treated respectfully and fairly, where personal and professional growth is supported, communication and collaboration are championed, and there is a sense of community and trust at all levels, which enables effective decision-making. A healthy work environment comprises competent employees, appropriate workloads, effective communication, collaboration, and empowerment, which leads to positive outcomes for patients, employees, and the organization. 14 The American Association of Critical-Care Nurses identified 6 areas for establishing and sustaining a healthy work environment including skilled communication, true collaboration, effective decision-making, appropriate staffing, meaningful recognition, and authentic leadership. 16 These align with the practices identified in psychologically healthy workplaces which emphasize employee involvement, work-life balance, employee growth and development, employee recognition, and health and safety. 17

A healthy and safe work environment correlates significantly with job satisfaction as well as other positive employee outcomes including engagement, productivity, and organizational commitment. Additionally, when people feel good and experience satisfaction at work, they report increased self-efficacy, autonomy, higher levels of personal accomplishment, and organizational commitment.

Significant qualities identified in the literature on healthy work environments are presented in Table 1 . Those include areas of collaboration and teamwork, growth and development, recognition, employee involvement, accessible and fair leaders, autonomy and empowerment, appropriate staffing, skilled communication, and a safe physical workplace. 18 Other factors contributing to satisfaction and retention include positive orientation experiences, good teamwork, clear procedures and instructions, appropriate workloads, managerial support, and autonomy. 11 Additionally, leader support and leader effectiveness protect against negative consequences from a stressful environment, 19 contribute to the provision of high quality and timely care, 20 decrease burnout, 6 and reduce turnover. 21

Table 1

Key Qualities Found in Healthy Work Environments

What Nurse Leaders Can Do to Improve the Work Environment

Nurse leaders can take a proactive role to shift the work environment and create the space for health and well-being, and for nurses to thrive at work. There are 2 aspects to changing the work environment. The first is creating and communicating a new vision, setting the tone, being clear about expectations, and ensuring staff understand that what was tolerated previously may no longer be acceptable. Nurse leaders must ensure staff know what is being asked of everyone and paint a picture for how it will feel in the new environment. And second, nurse leaders must uphold the new standards by teaching staff new ways of interacting and correcting behaviors when they do not align with the new vision.

A collaborative approach with positive interactions and active participation requires nurse leaders to encourage and facilitate teamwork. Staff rely heavily on interpersonal relationships and teamwork for cooperation, collaboration, and safety. 20 Interpersonal relationships are a key element of satisfaction at work. Collaboration, professional cohesion, and positive interactions with colleagues help create a sense of value and become a buffer for the demands of managing complex and challenging patients. 21 Nurse leaders need to champion teamwork and collaboration to ensure that staff work together to accomplish required work demands. Respectful interactions must be encouraged, and disrespectful ones addressed promptly and eliminated.

Nurse managers, through their behaviors and attitudes, create an environment which induces motivation, they demonstrate belief in their ability, listen thoughtfully, and bring out the best in the team. Nurse leader behavior directly impacts job satisfaction, morale, and employee performance which are critical factors to organizational success. Effective communication by leaders includes honesty, respect, good listening, and empathy, which impacts team effectiveness and outcomes and can create an environment of inclusiveness that supports team members to aid in their retention. 22 The leaders’ failure to address employee feelings and not win their respect leads to the failure of the manager, increases the stress of the team, and decreases organizational effectiveness. 15

Other themes in the literature include the use of acknowledgement and appreciation to help employees feel valued. Nurse leaders can find ways to coach, encourage, recognize, and support their staff and create an environment that reinforces the positive feelings that come from celebrating one another. It requires attention and consistent effort, but the effects are very impactful. Formal and informal acknowledgement serves to garner positive feelings within the work environment and can spread throughout the team.

Another important factor for job satisfaction is autonomy or job control, the ability of the individual to make decisions impacting their work. Staff who are permitted a sense of autonomy, and the perceived capacity to influence decisions at work, reported higher levels of personal accomplishment and lower rates of burnout. 11 Nurses need a work environment that offers respect and supports their scope of practice. Nurse managers can assist individuals to gain job control by ensuring adequate onboarding and orientation, ongoing training, and promoting an environment where questions and asking for help are encouraged and supported.

Organizations that offer opportunities for personal growth and professional development have a competitive advantage. Some individuals enjoy the bedside and want to remain there for their careers, yet they still want to learn, grow, and develop within that scope of practice and they want to be recognized and appreciated for their years of service. Other persons may want to advance in their roles and responsibilities. Nurse managers must take an interest in the individuals on their team, discover their desires for learning and growth, and identify their strengths so they can find ways to maximize them.

Healthy Work Environments Post-pandemic

Although the pandemic has shifted people’s attention to the self-care strategies implemented by individual employees, caring for employee well-being must include management strategies that support a healthy, safe work environment. The problems facing the health care workforce—burnout, stress, disengagement, and dissatisfaction—existed well before the pandemic and will continue to exist after it unless leaders change their approach to the work environment and how people behave within the workspace. Now is the time to envision a new work environment and to do things differently so that nurses, health care leaders, and workers at all levels can be productive, engaged, and thrive at work. By attending to the psychosocial work environment, health care can course correct for the factors troubling the health care workforce today and produce different outcomes—satisfaction, enjoyment, growth, joy, and meaning.

Julie Donley, EdD, MBA, BSN, RN, PCC, is an ICF professional certified coach, certified team coach, author, speaker, award-winning thought leader, adjunct professor, and prior executive nurse in behavioral health. She partners with established and aspiring leaders so they lead with confidence, communicate effectively, and create work environments that support the wellbeing and productivity of employees and create a fulfilling work experience. Visit her online at www.DrJulieDonley.com .

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 14 October 2024

Explaining organizational commitment and job satisfaction: the role of leadership and seniority

- Catarina Morais 1 ,

- Francisca Queirós 2 ,

- Sara Couto 2 ,

- A. Rui Gomes ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6390-9866 3 &

- Clara Simães ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9856-2295 4 , 5

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 1363 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

- Business and management

Effective leaders increase organizational success. The Leadership Efficacy Model suggests that leaders’ efficacy increases when leaders are perceived as congruent; that is, when employees perceive the leader to do (practical cycle of leadership) what s/he says will (conceptual cycle of leadership) and there is a close match between what employees expect from leaders and what leaders display. This recent theoretical framework also acknowledges that a number of factors can interfere with the relationship between leadership cycle congruence and leadership efficacy. Such antecedent factors include group members’ characteristics (e.g., organizational seniority). This study aimed to test the assumption that leadership cycles congruence positively predicts leadership efficacy (measured by organizational commitment and job satisfaction, and that this relationship is moderated by employees’ seniority. 318 employees (55% male, with an average seniority of 8 years) completed a questionnaire assessing leadership cycles, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction. Path analysis results showed that the higher leadership cycles congruence, the higher employees’ organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Furthermore, the relationship between leadership cycle congruence and organizational commitment was stronger for more senior members of the organization (but not for job satisfaction). The results highlight the importance of leaders act in a congruent manner with their ideas and of meeting employees’ needs. Moreover, it shows that senior members of the organization are particularly sensitive to leadership congruency.

Similar content being viewed by others

The impact of leader depletion on leader performance: the mediating role of leaders’ trust beliefs and employees’ citizenship behaviors

Ethical leadership, internal job satisfaction and OCB: the moderating role of leader empathy in emerging industries

How does narcissistic leadership influence change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior? Empirical evidence from China

Leadership is key for organizational efficacy and success (Hogan and Kaiser, 2005 ; Kaiser et al., 2008 ) and has been consensually defined as the process that aims to influence employees to achieve organizational goals (Voon et al., 2010 ). From a strategic and effective point of view, leadership enables organizations to increase their productivity, profit and, subsequently, achieve a competitive advantage (Yahaya and Ebrahim, 2016 ). Leaders are primarily responsible for the organizations they represent, and their role involves conveying to employees the need to work towards a common goal (Hogan and Kaiser, 2005 ). Thus, leadership efficacy can be conceptualized as the collective efficacy that results from the process of leading; in other words, that results from the dyad of leaders and followers’ behaviors, and can be operationalized by a wide range of individual, group and organizational level outcomes (cf. Hannah et al., 2008 for a review). For example, previous studies point out that leaders facilitate increased employee organizational commitment (e.g., Sedrine et al., 2020 ; Yahaya and Ebrahim, 2016 ) and job satisfaction (e.g., Kelloway and Gilbert, 2017 ; Yukl, 2008 ), and influence employees toward achieving organizational goals (Chaturvedi et al., 2019 ).

These data from the literature suggests that leadership efficacy can be translated through the impact of the leader’s actions on employees’ behaviors (e.g., Kaiser et al., 2008 ). However, employees’ expectations about their leader, which may arise for different reasons (e.g., previous work experience), may have an impact on leadership efficacy (Fu and Cheng, 2014 ; McDermott et al., 2013 ). For example, Baccili ( 2001 ) in a qualitative study found that employees expect congruency between what the leader says and what the leader does, and when employees perceive lack of congruence they manifest lower work engagement (Jabeen et al., 2015 ). Therefore, to comprehensively understand the leadership process and its impact on employees, it is important to consider the congruence between the leader’s words and actions, and between the leader’s actions and what the employee wants. This assumption is precisely the rationale of the Leadership Efficacy Model (Gomes, 2014 , 2020 ), which suggests that the closer the relationship between what the leader think to do (conceptual cycle of leadership) and what the leader does (practical cycle of leadership), from both the subjective perspectives of leaders and employees, the greater the leadership efficacy (Gomes, 2014 ). Moreover, the model assumes that a number of factors related to behaviors assumed by leaders (leadership styles) and characteristics of leaders, members and context influence (antecedent factors of leadership) moderate the relationship between leadership cycles congruence and leadership efficacy. In other words, leaders can increase efficacy if they assume congruent cycles of leadership and if they use positive behaviors to implement the leadership cycles and if they consider the antecedent factors of leadership.

So far, and to the extent of our knowledge, only two studies have empirically tested the Leadership Efficacy Model (cf. Alves et al., 2021 ; Gomes et al., 2022 ). Both studies were conducted in a sports setting and showed that leadership cycle congruence positively predicts leadership efficacy. Moreover, Gomes and colleagues ( 2022 ) was the first study to also test the role of specific leadership styles (leadership behaviors) and antecedent factors of leadership as facilitators of leadership efficacy. However, this study did not separate the role of leaders, members and context characteristics of antecedent factors of leadership, but computed an overall favorability index, which does not allow to understand the specific role of each variable. Thus, in the present study we aim to expand previous literature by (1) considering the application of the Leadership Efficacy Model in an organizational context and whether leadership cycles congruence is a predictor of important outcomes for organizations, as is the case of commitment and job satisfaction; and (2) by testing the moderating role of group members’ characteristics which, to the extent of our knowledge, is yet to be done. This is important because the moderating role of such factors is a key assumption of the model. In this study, the group members’ (employees) characteristics included was their seniority within the organization. Employees’ seniority was chosen as the member characteristic to be analyzed (i.e., antecedent factor) because previous literature (e.g., English et al., 2010 ; Lee et al., 2018 ; Zeng et al., 2020 ) has shown that employees’ perceptions, evaluations and beliefs about the organization (e.g., organizational commitment and job satisfaction) are shaped by how long they have been in the organization.

Leadership efficacy model

The Leadership Efficacy Model (Gomes, 2014 , 2020 ) was developed as a comprehensive framework that defines different sets of factors that influence leadership efficacy. In a nutshell, this theoretical approach states that leadership efficacy increases if leaders establish linear relations between how they intend to exert leadership (conceptual cycle of leadership) and how they really implement the leadership (practical cycle of leadership), i.e., if there is leadership congruence. Moreover, the model combines Trait, Behavioral and Contingency Leadership Theories to argue that this relationship between leadership congruence and efficacy will be either facilitated or debilitated (i.e., moderated) by the leadership styles adopted and by the antecedent factors (namely leader characteristics, member characteristics, and context characteristics). In this study, the main aim was to test the relationship between leadership congruence and leadership efficacy (measured by organizational commitment and job satisfaction), and the moderating effect of members’ characteristics (measured by employees’ seniority).

The main innovation of the Leadership Efficacy Model is its focus on the congruence of the leadership cycles and leadership efficacy, advocating that the leader’s activity has a dynamic nature, i.e., an influence process that is built over time and not a static phenomenon (Gomes, 2014 , 2020 ). In this sense, it is suggested that leading without a congruence of leadership cycles should be the basis for the leader’s activity; thus, acting by trial and error is less effective and productive for all the involved in the leadership phenomenon (Gomes, 2014 ). Therefore, the Leadership Efficacy Model emphasizes the importance of leaders establishing linear relationship between what is important to them (leadership philosophy), the behaviors they assume to achieve the objectives (leadership practice) and the definition of strategies to evaluate the achievement of their ideas and objectives with the group members (leadership criteria) (Gomes, 2014 , 2020 ). These linear relationships occur in two interdependent leadership cycles, the conceptual and the practical. The conceptual cycle includes the beliefs of leaders and employees about how leadership should be organized in terms of philosophy, practice, and criteria. The practical cycle incudes the beliefs of leaders and employees about how leadership occurs in real contexts, in terms of philosophy, practice, and criteria. Thus, this model advocates that the closer the cycles are to each other, the greater the leadership efficacy will be (Gomes, 2020 ).

The conceptual cycle of leadership occurs through three distinct domains: leadership philosophy, leadership practice, and leadership criteria (Gomes, 2020 ). Leadership philosophy refers to the values, beliefs, assumptions, attitudes, principles, and priorities about what leadership is and how leadership should be assumed (Gomes, 2014 ). In other words, the leadership philosophy can be seen as the beliefs that the leader has about the influence on group members, reflected in a set of mental representations of how to exert the role of the leader. The leadership practice is characterized by the behaviors and actions that the leader considers most appropriate to implement the philosophy of leadership, such as, for example, assuming maximum effort in performing the tasks or represents a role model for the group members. Finally, leadership criteria correspond to the leader’s mental representations of the indicators which can be used to evaluate if the leadership philosophy and the practice are producing the desired effects. For example, leaders can use criteria as the number of goals achieved or number of tasks performed with maximum quality as indicators of success produced by the philosophy and practice of leadership.

On the other hand, the practical cycle consists of the application of the conceptual cycle in daily life, both by the leader and the group members (Gomes, 2020 ). This cycle is characterized by the mental representations of the leader and the group members about what the leader is really doing in each specific situation, and also includes the same three domains: leadership philosophy, leadership in practice and leadership criteria. The processes start when the leaders transmit their ideas and principles (leadership philosophy), how to achieve the leadership philosophy (leadership in practice), and how to evaluate it (leadership criteria). This sharing may take place in a more formal way (e.g., work meetings) or in an informal way (e.g., daily contact between the leader and the group members) (Gomes, 2020 ). Since this cycle is the operationalization of the conceptual cycle, it means that it begins when both the leader and the group members assume the behaviors to achieve the principles defined by the leader and accepted by the members (Gomes, 2020 ). To this extent, leadership cycles congruence also implies that leaders’ activity matches employees’ expectations and needs (i.e., how they think leaders should exert leadership).

According to the model, the characteristics of the leader, of the group members, and of the situation assume a status of moderating variable between the congruency of the two cycles and leadership efficacy, being named antecedent factors of leadership (Gomes, 2020 ). This means that the leader should take these antecedent factors of leadership into account when establishing the leadership cycles, since they can maximize or inhibit their actions. For example, regarding the characteristics of the group members, leaders should consider a wide number of factors, as is the case of professional (e.g., objectives, hierarchical level), demographic (e.g., seniority), and psychological (e.g., self-confidence) variables, because the closer they act according to these characteristics, the more likely their action will be effective (Gomes and Resende, 2015 ).

In sum, the Leadership Efficacy Model proposes that higher levels of congruency between the practical and conceptual cycles of leadership augments the leadership efficacy. Moreover, the model proposes that characteristics of the group members influence the relationship between leadership cycles and leadership efficacy. In our study, we selected organizational commitment and job satisfaction as indicators of leadership efficacy and seniority as moderator of the influence produced by leadership congruency in organizational commitment and job satisfaction.

H1 and H2. Leadership efficacy: organizational commitment and job satisfaction

Leadership efficacy can be understood as the multiple impacts produced by the leader on others, as is the case of employee satisfaction, motivation, and organizational outcomes (Kaiser et al., 2008 ; Malik, 2013 ; Voon et al., 2010 ). Therefore, it can be measured in a variety of ways (e.g., Andrews et al., 2006 ; Kaiser et al., 2008 ; Kanji, 2008 ). A diversity of evaluation measures is important to overcome possible biases, as a single organizational outcome (e.g., productivity measure, financial performance, turnover) does not provide a complete overview (Kaiser et al., 2008 ; Scullen et al., 2000 ). As an influence process, leaders’ behaviors affect employees’ attitudes towards work, such as the organizational commitment, work engagement, and job satisfaction (Rehman et al., 2020 ; Saleem, 2015 ; Voon et al., 2010 ). Specifically, organizational commitment and job satisfaction are relevant variables to the organizational context, as they have been associated with lower absenteeism and turnover, higher motivation, leadership satisfaction, and increases in organizational citizenship behaviors (e.g., Gatling et al., 2016 ; Hanaysha, 2016 ; Joo and Park, 2010 ; Malik, 2013 ). For these reasons, we selected organizational commitment and job satisfaction as indicators of leadership efficacy, as they represent key variables in organizational contexts and because they can represent different constructs of human experience at work, one more related to how the individual feel about the work activity (job satisfaction) and another more related to how the individual feel about the organization (organizational commitment).

Organizational commitment is defined as a force that stimulates the individual’s involvement and identification with an organization, the willingness to put effort and dedication in achieving organizational goals, as well as the desire to remain in the organization (Porter et al., 1974 ). Therefore, it is seen as a significant factor in determining employee behavior (Meyer et al., 2002 ; Yahaya and Ebrahim, 2016 ). Specifically, organizational commitment is perceived as an emotional attachment of the employee to the organization (Ćulibrk et al., 2018 ; Meyer et al., 2004 ), where individuals identify with the values and mission and enjoy being part of the organization (Hanaysha, 2016 ; Meyer and Allen, 1991 ; Pradhan and Pradhan, 2015 ). Employees who report high levels of commitment exhibit aspirations to contribute meaningfully to the organization and a greater willingness to make sacrifices for it and, at the same time, report fewer intentions to leave or resign and tend to feel more satisfied with their work and have higher intrinsic motivation (cf. Ćulibrk et al., 2018 ; Hanaysha, 2016 ).

Mathieu and colleagues ( 2016 ) state that the popular adage “Employees don’t quit their companies, they quit their boss” has been empirically proven, enhancing the importance and influence of the leader’s role in the willingness of employees to remain in the organization. In this sense, there are several studies exploring the relationship between employees’ perceptions of the leaders’ actions on their organizational commitment (Gatling et al., 2016 ; Sedrine et al., 2020 ; Yahaya and Ebrahim, 2016 ). For example, Pradhan and Pradhan ( 2015 ) reported that leaders who demonstrate attentiveness to employees’ personal and professional development, positively influence employee commitment because this demonstration leads to an emotional attachment to the leader and the organization. Additionally, Sedrine and colleagues ( 2020 ), concluded that leaders who seek to involve employees in decision making inspire greater trust and job satisfaction and have a positive impact on organizational commitment. On the other hand, these authors reported that supervision by the leader has an adverse effect on employees’ attitude, reducing their commitment to the organization. This effect is justified by the control of autonomy, feeling of lack of trust and disrespect felt by employees, translated by a low level of commitment (Sedrine et al., 2020 ). Overall, these different findings support the idea that the behaviors adopted by the leader are significantly related to employees’ organizational commitment (cf. Yiing and Ahmad, 2009 ). Similarly, we argue that leadership cycles congruence (i.e., leaders’ words and actions are aligned) feeds a positive relationship between leader and employees. By being congruent in their words and actions, leaders display trustworthiness and assure employees they can trust them and, therefore, increase their commitment with the organization.

H1: Perceived leadership cycles congruence positively predicts employees’ organizational commitment. The higher the perceived congruence, the higher the organizational commitment .

One of the major challenges for leaders is to ensure the job satisfaction of their employees (Asghar and Oino, 2018 ), making it pertinent to understand this construct. Job satisfaction is defined as “the attitudes and feelings people have about their work”, and the more satisfied employees are, the more positive their attitudes will be (Armstrong, 2006 , p. 474). Satisfaction levels can be affected intrinsically, depending for example, on the self-esteem of the group members, or extrinsically, considering, for example, the context or the quantity and quality of the leader’s supervision (Armstrong, 2006 ; Malik, 2013 ).

The existence of a relationship between employees’ job satisfaction and satisfaction with their leaders is described in the literature (Elshout et al., 2013 ; Tsai, 2011 ). In fact, job satisfaction has been associated with leaders who manifest behaviors of inspiration, motivation, concern, and respect for employees (Judge and Kammeyer-Mueller, 2012 ; Saleem, 2015 ). Furthermore, it is suggested that the leader’s behaviors of encouraging and supporting employees, as well as their confidence and clear vision can relate to employee job satisfaction (Tsai, 2011 ). These behaviors, mostly associated with transformational and transactional styles of leadership, are a reflection of how leaders (practical cycle of leadership) act or, in other words, how leaders can exert their influence and increase the congruence between cycles of leadership. Moreover, Alves and colleagues ( 2021 ), who conducted a study based on the Leadership Efficacy Model in a sport context, also found that leadership cycles congruence is associated with satisfaction with leaders. Overall, how employees perceive their leaders is a decisive factor in their overall satisfaction (Hogan and Kaiser, 2005 ). We argue that by perceiving the leader as being congruent with their words (conceptual cycle of leadership) and daily actions (practical cycle of leadership), employees develop a positive image and relationship with the leader which, in turn, leaders to higher job satisfaction. Therefore, we expect that:

H2: Perceived leadership cycles congruence positively predicts employees’ job satisfaction. The higher the perceived congruence of the leader’s cycles, the higher the job satisfaction .

H3. Antecedent factors of leadership: the moderating role of seniority

The actions of leaders do not occur in isolation, depending on some factors that can help to understand the multiple impacts produced by leadership. According to the Leadership Efficacy Model there are three antecedent factors of leadership that can influence the impacts of leadership cycles congruence in leadership efficacy: the personal and professional characteristics of the leader, the personal and professional characteristics of team members, and the specific conditions provided by the organization under which the leader is working (Gomes, 2020 ). These factors influence the relationship between leadership cycles (e.g., how leaders intend to assume leadership and how leaders assume leadership) and leadership efficacy. Seniority is an example of these factors since employees’ perceptions and evaluations change depending on how long they have been with the organization (English et al., 2010 ; Wright and Bonett, 2002 ). The literature highlights the relationship between seniority and commitment (Akinyemi, 2014 ; Hong et al., 2016 ; Lee et al., 2018 ) and seniority and job satisfaction (Lian and Ling, 2018 ; Zeng et al., 2020 ), but there is less knowledge about the moderating effect of seniority on the relationship between how leadership is exerted (e.g., leadership cycles congruence) and leadership efficacy.

Previous research has established that employees’ beliefs regarding the organization vary according to the length of service in the organization (e.g., Low et al., 2016 ), which is also reflected on the psychological contract they hold regarding the organization (cf. Bal et al., 2013 ). Specifically, Bal and colleagues ( 2013 ) found a relationship between the fulfillment of the psychological contract and greater involvement at work by the employee but only for employees with less seniority. According to these authors, this is because employees with less seniority value the norms of reciprocity more highly. On the other hand, employees’ seniority also has implications on the impact of the violation of the psychological contract, as employees respond differently to employers’ non-fulfillment of obligations (cf. Sharif et al., 2017 ; Priesemuth and Taylor, 2016 ). Specifically, more recent employees have higher expectations about the employers when they first join the organization and, the longer they stay, the more they adjust these expectation—therefore, the higher their seniority, the lower employees’ perceptions of employer’s obligations (Payne et al., 2015 ).

In sum, the beliefs and expectations that employees hold about the organizations and their leaders influence the aspects they pay attention to, that they value, their interpretations, and reactions (Rousseau, 2001 , Rousseau et al., 2018 ). According to the aforementioned literature review, employees with lower seniority are more tend to value more the reciprocity between themselves and the organization and to hold higher expectations of the organization. Additionally, the non-fulfilment of expectations has a greater influence on their behaviors and attitudes, compared to employees with greater seniority. For that reason, we argue that employees with lower seniority are more aware and sensitive of their leader’s behaviors. Therefore, and based on the Leadership Efficacy Model (Gomes, 2014 , 2020 ), we expect that if leaders display low congruency, this would affect more negatively employees with lower seniority. Thus, we established the third hypothesis for this study:

H3: Seniority has a moderating effect on the relationship between leadership cycles congruence and leadership efficacy (measured by organizational commitment and job satisfaction). Specifically, it is expected that less seniority amplifies the positive relationship of leadership cycles congruence with (H3a) organizational commitment and (H3b) job satisfaction .

Data collection procedure

As aforementioned, the main aim of this study was to test the relationship between leadership congruence and leadership efficacy (i.e., organizational commitment and job satisfaction), as well as the moderating role of members’ characteristics (i.e., seniority). In order to test this conceptual model, a correlational study was conducted with employees from different organizations who evaluated their leaders. The first step consisted of obtaining approval from the Ethics Committee from the fourth authors’ University. Once approval was obtained [cf. Ethical Statement], the research team created the questionnaire on Qualtrics® platform and a link for dissemination was generated using the same software. A multiple-source approach was used to recruit participants: specifically, the questionnaire was disseminated on online platforms (LinkedIn, Facebook; 38%) and through six organizations from different sectors which were part of the research teams’ network (public administration: 25%, technology: 18%, automotive: 9%, catering: 5%, healthcare: 5%) and who agreed to distribute the study among their employees.

When participants accessed to the questionnaire, a first page with the informed consent, and explaining the study goals and procedure was displayed. Once they agreed to participate in the study, an initial screening question was used to exclude any participants who did not directly report to a leader. If they met this inclusion criteria (having a leader in their organization to whom they report directly), several demographic questions were asked and then they completed the measures regarding leadership congruency, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction. The order of the items and measures was randomized. Completing the whole research protocol took them, on average, about 25 min. The data was collected between February and April 2021.

Participants

A sample of 318 employees (55% male) was considered in the study. Their aged ranged from 21 to 72 years-old ( M = 35.78, SD = 10.54). Most participants held a bachelor’s degree (38%) or a master’s degree or higher (30%), and 27% completed high school.

Participants worked in a wide range of sectors: service industry (22%), health and social care (17%), public administration and defense (17%), manufacturing (8%), administrative activities (7%), education (5%), retail (5%), IT and communication (3%), finance (2%), hospitality (2%), among others (12%). The majority of participants were full-time employees (97%) with permanent employment contract (60%). Regarding participants’ seniority within the organization, it ranged from 1month to 42 years ( M = 8 years, SD = 9.5 years).

Leadership congruency

The Leadership Efficacy Questionnaire (LEQ; Gomes et al., 2022 ) was used to assess the congruency of leadership cycles (conceptual and practical cycles). This measure evaluates three different dimensions: (1) leadership philosophy (5 items, e.g., “My leader tells us the ideas s/he values the most”, α conceptual = 0.87, α practical = 0.91), (2) leadership practice (5 items, e.g., “My leader acts in accordance with the ideas valued”, α conceptual = 0.89, α practical = 0.92), and leadership criteria (5 items, e.g., “My leader evaluates if what is done is in accordance with what we wanted to achieve”, α conceptual = 0.89, α practical = 0.93). A score for each dimension was calculated by averaging participants’ responses (1 = never; 5 = always). For each of the 15 statements, employees answered twice: once regarding their leader’s preferred behaviors (leadership philosophy, practice, and criteria at the conceptual cycle), and another referring to their leader’s current behaviors (leadership philosophy, practice, and criteria at the practical cycle). A final score of leadership congruency was calculated by subtracting participants’ responses in the conceptual cycle from the practical cycle, and negative numbers were mirrored, so the final variable would only include positive numbers. Therefore, values closer to 0 indicate higher congruency between current and preferred leadership behaviors, creating a new variable named the Leadership Cycles Congruence Index (LCCI).

Organizational commitment

Participants’ organizational commitment was assessed using the Organizational Commitment Scale (Conley and Woosley, 2000 ; Mowday et al., 1982 ; Portuguese translation by Gomes, 2007 ). Using a likert scale (1 = completely disagree; 5 = completely agree), participants rated their agreement with nine statements (e.g., “I am proud to tell other people that I am part of this organization”, α = 0.91). A score of organizational commitment was computed by averaging participants’ responses.

Job satisfaction

Employees’ perceptions regarding their job satisfaction were evaluated using the Portuguese version of the Job Satisfaction Questionnaire (Meliá and Peiró, 1989 ; Pocinho and Garcia, 2008 ). Participants were asked to rate their satisfaction (1 = not satisfied at all, 7 = extremely satisfied) to 23 different aspects of their work (e.g., “I am happy about my career progression opportunities”, α = 0.96). Their responses were averaged to create a job satisfaction score.

Data analyses procedure

An a-priori sample size calculator was used to determine the minimum sample required. For a medium effect size of 0.20 and a desired power level of 0.80 (at a probability level of 0.05), a minimum of 223 participants were recommended (cf. Soper, 2022 ). The study sample met this requirement.

Then, the first step consisted of verifying the statistical assumptions of normality and multicollinearity for the four variables of the study: perceptions of leadership congruency, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction, as well as participants’ seniority within their organizations. The normality assumption was tested using Kline’s ( 2015 ) criteria of skewness ≤|3| and kurtosis ≤ |10|. The multicollinearity assumption was checked based on the correlations among variables (which should be <0.80) and VIF (which should be <5) (cf. Marôco, 2014 ).

Path analysis using AMOS Software ® was conducted so the full model could be tested simultaneously. Therefore, perceptions of leadership congruency were included as a predictor, and organizational commitment and job satisfaction as outcomes (H1 and H2). To test the moderating role of seniority (H3a and H3b), the interaction between perceptions of leadership congruency and seniority was calculated and inserted in the model as a predictor. All predictor variables (leadership congruency, seniority, interaction leadership congruency x seniority) were first standardized using z -scores, as they used different unity measures.

The quality of the theoretical model was evaluated using the following criteria: (a) chi-square statistics ( χ 2 ); (b) Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; Steiger, 1990 ), so that adequate fit concluded for values between 0.05 and 0.08, and good fit when below 0.05 (cf. Arbuckle, 2008 ); (c) Standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), considering a good fit was achieved when below 0.10 (cf. Kline, 2015 ); (d) Goodness of Fit (GFI) and Comparative fit index (CFI), for which values above 0.95 indicated a good fit (cf. Bentler, 1990 ; 2007 ; Marôco, 2014 ).

Descriptive statistics and preliminary analysis

Regarding normality assumptions, Using Kline’s ( 2015 ) criteria of skewness ≤|3| and kurtosis ≤|10 | , there were no severe deviations from normality found in the data (−0.65 > sk < 1.39; 0.26 > ku < 1.30). Thus, parametric tests were conducted to test the study hypotheses (cf. Kline, 2015 ).

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics of the study variables (participants’ seniority and perceptions of leadership congruency, organizational commitment and job satisfaction), as well as the two-tailed correlations among them. The higher the participants’ seniority, the less leadership congruency (numbers closer to 0) and the lower the job satisfaction (and vice-versa) they tend to perceive. On the other hand, the more congruency they perceive, the higher the organizational commitment and job satisfaction. The latter variables are also highly correlated. No correlations were above 0.80 and all VIF coefficients ranged from 1.02 to 1.99—therefore, the non-multicollinearity assumption was met.

Path analysis (H1, H2, H3)

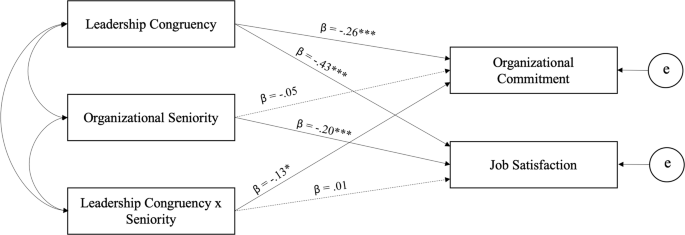

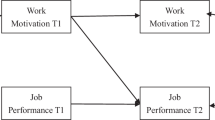

The proposed model (cf. Fig. 1 ) was tested using path analysis. The results show that it is a good fit to the data: χ 2 (1) = 5.96, χ 2 /df = 5.96, RMSEA = 0.125, 95% CI [0.044, 0.230], p RMSEA = 0.061, SRMR = 0.039, GFI = 0.993, CFI = 0.980. A summary of the parameter estimates can be found in Table 2 . It can be concluded that higher perceptions of leadership congruency predict higher organizational commitment and job satisfaction, thus confirming H1 and H2. On the other hand, the longer participants are enrolled in a particular organization (seniority), the lower their job satisfaction, but not their organizational commitment. The leadership congruency x seniority interaction is a predictor of organizational commitment but not job satisfaction (therefore, H3b was not supported). The overall model explained 22% of the variance of participants’ job satisfaction and 10% of the variance of their organizational commitment.

Note : * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. Dash arrows represent non-significant paths.

A closer look at this latter interaction was conducted by splitting the sample into high vs. low seniority and conducting separate regression analyses. The criteria used to compute the two groups was based on previous literature that used 60 months (5 years) as a cut-off point to decide whether an employee would be considered to have a stable tenure with the organization or not (cf. Bal et al., 2013 ; Boswell et al., 2005 ). Thus, following the same criteria, participants were split into high seniority (≥60 months; n = 150) and low seniority (<60 months; n = 168). The results indicated that leadership congruency predicts organizational commitment for more senior members of the organization [ F (1,147) = 30.85, p < 0.001, R 2 = 0.174, b = −0.42, β = −0.42, t = −5.55, p < 0.001] but not for younger members of the staff [ F (1,167) = 2.56, p = 0.111]. Even though the interaction for organizational commitment was significant, its direction does not support H3a.

This study aimed to test the relationship between leadership cycle congruence and leadership efficacy in an organizational setting, considering the analysis of the moderating influence of seniority. This analysis was done by assuming the predictions of the Leadership Efficacy Model (Gomes, 2014 , 2020 ). The results supported the main proposition of the model that congruence between leadership cycles explains higher levels of organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Equally important, our study tested if antecedent factors of leadership can either exacerbate or minimize the influence of leadership cycle congruence on leadership efficacy. The results showed that leadership cycle congruency is a positive predictor of organizational commitment for more senior members of the organization. However, seniority did not moderate the relationship between leadership cycle congruency and job satisfaction.

As aforementioned, the Leadership Efficacy Model (Gomes 2014 , 2020 ) states that higher leadership cycle congruency predicts leadership efficacy. This assumption was corroborated by the study. As expected, when employees perceived higher congruency between conceptual and practical cycles of leadership, they displayed stronger organizational commitment (H1) and job satisfaction (H2). These results support the main theoretical assumption of the Leadership Efficacy Model and are consistent with previous literature that tested this theoretical framework in a sports context, showing that higher congruency in leadership cycles predicted higher satisfaction with leader and perceptions of team performance (Alves et al., 2021 ; Gomes et al., 2022 ). Thus, the results support the idea that when leaders’ daily actions (practical cycle of leadership) are congruent with employees’ desires/needs (conceptual cycle of leadership), it increases leadership efficacy—in our case, it increases employees’ commitment towards the organization and their job satisfaction.

The third hypothesis of the study predicted that seniority would moderate the relationship between the congruence of leadership cycles congruence and leadership efficacy. Specifically, it was expected that less seniority would amplify the positive relationship leadership between efficacy and organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Previous literature (e.g., English et al., 2010 ; Low et al., 2016 ; Phungsoonthorn and Charoensukmongkol, 2018 ) has already established that employees’ perceptions and evaluations regarding the organization change over time. Specifically, research suggests that employees with lower seniority attribute more value to the norms of reciprocity between themselves and the organization and, therefore, the fulfillment or not of the established expectations and their involvement in the work is particularly important to these employees (cf. Bal et al., 2013 ). This idea was supported by Payne and colleagues ( 2015 ), who argued that when someone first joins the organization, they have higher expectations, which are adjusted and, therefore, decrease, over time. Moreover, based on previous research that showed that staff with lower seniority is more aware of leaders’ behaviors (e.g., Rousseau et al., 2018 ), seniority was expected to moderate the relationship between leadership cycles congruence and efficacy in such a way that it would be amplified for less senior members of staff.

However, even though the results show a significant interaction of Leadership Cycles Congruence x Seniority on employees’ organizational commitment, the relationship between the predictor and the outcome is only significant for senior members of the staff. In other words, the results showed that leadership congruency only predicts organizational commitment for senior members of the organization, but not for younger members of the staff, contradicting H3a. No interaction was found for job satisfaction, and, therefore, H3b was also not supported. According to Payne and colleagues ( 2015 ), employees’ expectations adjust over time, with employees’ perceptions of employer obligations significantly decreasing over the years in the organization. Taking this into consideration, one possible justification is that if the non-fulfillment of expectations has a lower influence on more senior members of the organization (cf. Rousseau et al., 2018 ), when a leader fulfills their needs, and shows stronger congruence between their statements (conceptual cycle) and actions (practical cycle) it exceeds their expectations and, therefore, has a more positive impact. An alternative explanation is related to the fact that data was collected during the COVID19 pandemic, which was a time in which leaders were particularly important (cf. Eichenauer et al., 2022 ) in keeping stability and facilitating employees’ work-life balance, which are important features for more senior employees and what they value in the relationship they established with the organization (cf. Low et al., 2016 ).

Limitations and future research

Considering the particular circumstances in which data for this study was collected, future research should aim to test whether these results are stable once the pandemic is over, assuring its replicability. It is also important to note that, even though appropriate to the aims of this particular study, cross-sectional designs encompass a number of limitations. One of those limitations, especially when testing relationships between variables, refers to the common method variance, which is drawn from the fact that the same participants answered both predictor and outcome variables at the same moment. However, this issue was addressed during data collection: an online platform was used to collect data, and the order of items and measures was randomized (cf. Chang et al., 2010 ). An alternative methodological approach would be to partner with an organization to conduct a longitudinal study. This approach would allow (1) to infer the duration of the impact of leadership cycles congruence on efficacy; and (2) the use of objective efficacy measures (e.g., turnover rate, absenteeism), which are important to provide a more comprehensive understanding of leadership efficacy (cf. Gomes, 2014 ; Gomes and Resende, 2015 ). Moreover, even though the present study tested the main assumption of Leadership Efficacy Model (regarding leadership congruence) and tested the moderating role of an antecedent factors of leadership, other variables included in the theoretical model should be included in future research (namely, the leadership styles, and antecedent factors of leadership regarding the leader’s and the situation’s characteristics).

Conclusion and practical implications

Overall, the study results provide support for the Leadership Efficacy Model, showing that leadership cycles congruence increases leadership efficacy (in this case, job satisfaction and organizational commitment), and that antecedent factors of leadership such as group members’ characteristics (namely seniority) can act as moderators of this relationship. Thus, this study results provide empirical support to two key assumptions of this theoretical framework and is, to the extent of our knowledge, the first study to test the Leadership Efficacy Model in an organizational setting. Taken together, the results have important implications for practice, specifically in organizational contexts. First, they show that in order to maximize the efficacy of their leadership, leaders must make clear to employees their conceptual cycle. In other words, leaders need to state what they want and value in their teams (leadership philosophy), how they want those values to be implemented (leadership practice), and which indicators should be used to assess its implementation (leadership criteria). At the same time, leaders need to ensure that this is in line with what they do on a daily basis (practical cycle of leadership); that is, that the leadership they exert is close to what they conceptualize and that it considers the preferences and needs of their teams.

A second important implication refers to the role of the employee’s seniority in perceiving the leader’s actions. How employees perceive and assess the leader depends on how long they are at the organization, which is consistent with the idea that employees look for different things in the organization and, consequently, in their leaders over time. Therefore, the influence of leadership cycle congruence on the relationship employees establish in the organization varies according to seniority. In this study, it showed that the influence of leadership cycles congruence on employees’ organizational commitment was stronger for employees with a longer tenure, when compared to newer members of staff. Thus, the study highlights the importance of leaders being sensitive to the characteristics of their members and to their needs in order to adjust their actions to remain effective.

Data availability

The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Akinyemi BO (2014) Organizational commitment in Nigerian banks: the influence of age, tenure and education. J Mgmt Sustain 4:104–115. https://doi.org/10.5539/jms.v4n4p104

Article Google Scholar

Alves J, Morais C, Gomes AR, Simães C (2021) Liderança no voleibol: Relação entre filosofia, prática e indicadores de liderança. Coleção. Pesqui em Educção FíSci 20:153–161. http://hdl.handle.net/1822/70516

Google Scholar

Andrews R, Boyne GA, Walker RM (2006) Subjective and objective measures of organizational performance. In: Boyne GA, Meier KJ O’Toole LJ Jr, Walker RM (eds). Public service performance: perspectives on measurement and management. Cambridge University Press

Arbuckle JL (2008) Amos 17.0 user’s guide. SPSS Inc

Armstrong M (2006) A handbook of human resource management practice. Kogan Page Publishers

Asghar S, Oino I (2018) Leadership styles and job satisfaction. Mark Forces 13:1–13

Baccili PA (2001) Organization and manager obligations in a framework of psychological contract development and violation. Dissertation, The Claremont Graduate University

Bal PM, De Cooman R, Mol ST (2013) Dynamics of psychological contracts with work engagement and turnover intention: the influence of organizational tenure. Eur J Work Org Psychol 22:107–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2011.626198

Bentler PM (1990) Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull 107:238–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Bentler PM (2007) On tests and indices for evaluating structural models. Pers Individ Dif 42:825–829. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.024

Boswell WR, Boudreau JW, Tichy J (2005) The relationship between employee job change and job satisfaction: the honeymoon-hangover effect. J Appl Psychol 90:882–892. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.5.882

Article PubMed Google Scholar