Chapter 11. Interviewing

Introduction.

Interviewing people is at the heart of qualitative research. It is not merely a way to collect data but an intrinsically rewarding activity—an interaction between two people that holds the potential for greater understanding and interpersonal development. Unlike many of our daily interactions with others that are fairly shallow and mundane, sitting down with a person for an hour or two and really listening to what they have to say is a profound and deep enterprise, one that can provide not only “data” for you, the interviewer, but also self-understanding and a feeling of being heard for the interviewee. I always approach interviewing with a deep appreciation for the opportunity it gives me to understand how other people experience the world. That said, there is not one kind of interview but many, and some of these are shallower than others. This chapter will provide you with an overview of interview techniques but with a special focus on the in-depth semistructured interview guide approach, which is the approach most widely used in social science research.

An interview can be variously defined as “a conversation with a purpose” ( Lune and Berg 2018 ) and an attempt to understand the world from the point of view of the person being interviewed: “to unfold the meaning of peoples’ experiences, to uncover their lived world prior to scientific explanations” ( Kvale 2007 ). It is a form of active listening in which the interviewer steers the conversation to subjects and topics of interest to their research but also manages to leave enough space for those interviewed to say surprising things. Achieving that balance is a tricky thing, which is why most practitioners believe interviewing is both an art and a science. In my experience as a teacher, there are some students who are “natural” interviewers (often they are introverts), but anyone can learn to conduct interviews, and everyone, even those of us who have been doing this for years, can improve their interviewing skills. This might be a good time to highlight the fact that the interview is a product between interviewer and interviewee and that this product is only as good as the rapport established between the two participants. Active listening is the key to establishing this necessary rapport.

Patton ( 2002 ) makes the argument that we use interviews because there are certain things that are not observable. In particular, “we cannot observe feelings, thoughts, and intentions. We cannot observe behaviors that took place at some previous point in time. We cannot observe situations that preclude the presence of an observer. We cannot observe how people have organized the world and the meanings they attach to what goes on in the world. We have to ask people questions about those things” ( 341 ).

Types of Interviews

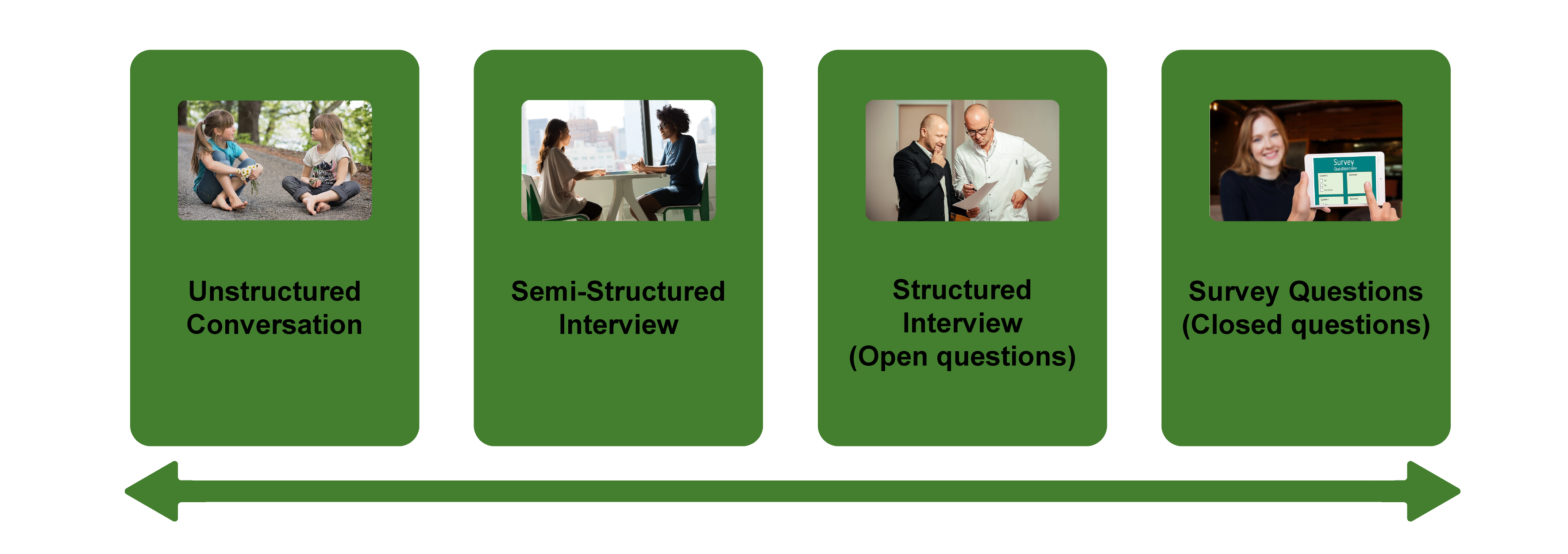

There are several distinct types of interviews. Imagine a continuum (figure 11.1). On one side are unstructured conversations—the kind you have with your friends. No one is in control of those conversations, and what you talk about is often random—whatever pops into your head. There is no secret, underlying purpose to your talking—if anything, the purpose is to talk to and engage with each other, and the words you use and the things you talk about are a little beside the point. An unstructured interview is a little like this informal conversation, except that one of the parties to the conversation (you, the researcher) does have an underlying purpose, and that is to understand the other person. You are not friends speaking for no purpose, but it might feel just as unstructured to the “interviewee” in this scenario. That is one side of the continuum. On the other side are fully structured and standardized survey-type questions asked face-to-face. Here it is very clear who is asking the questions and who is answering them. This doesn’t feel like a conversation at all! A lot of people new to interviewing have this ( erroneously !) in mind when they think about interviews as data collection. Somewhere in the middle of these two extreme cases is the “ semistructured” interview , in which the researcher uses an “interview guide” to gently move the conversation to certain topics and issues. This is the primary form of interviewing for qualitative social scientists and will be what I refer to as interviewing for the rest of this chapter, unless otherwise specified.

Informal (unstructured conversations). This is the most “open-ended” approach to interviewing. It is particularly useful in conjunction with observational methods (see chapters 13 and 14). There are no predetermined questions. Each interview will be different. Imagine you are researching the Oregon Country Fair, an annual event in Veneta, Oregon, that includes live music, artisan craft booths, face painting, and a lot of people walking through forest paths. It’s unlikely that you will be able to get a person to sit down with you and talk intensely about a set of questions for an hour and a half. But you might be able to sidle up to several people and engage with them about their experiences at the fair. You might have a general interest in what attracts people to these events, so you could start a conversation by asking strangers why they are here or why they come back every year. That’s it. Then you have a conversation that may lead you anywhere. Maybe one person tells a long story about how their parents brought them here when they were a kid. A second person talks about how this is better than Burning Man. A third person shares their favorite traveling band. And yet another enthuses about the public library in the woods. During your conversations, you also talk about a lot of other things—the weather, the utilikilts for sale, the fact that a favorite food booth has disappeared. It’s all good. You may not be able to record these conversations. Instead, you might jot down notes on the spot and then, when you have the time, write down as much as you can remember about the conversations in long fieldnotes. Later, you will have to sit down with these fieldnotes and try to make sense of all the information (see chapters 18 and 19).

Interview guide ( semistructured interview ). This is the primary type employed by social science qualitative researchers. The researcher creates an “interview guide” in advance, which she uses in every interview. In theory, every person interviewed is asked the same questions. In practice, every person interviewed is asked mostly the same topics but not always the same questions, as the whole point of a “guide” is that it guides the direction of the conversation but does not command it. The guide is typically between five and ten questions or question areas, sometimes with suggested follow-ups or prompts . For example, one question might be “What was it like growing up in Eastern Oregon?” with prompts such as “Did you live in a rural area? What kind of high school did you attend?” to help the conversation develop. These interviews generally take place in a quiet place (not a busy walkway during a festival) and are recorded. The recordings are transcribed, and those transcriptions then become the “data” that is analyzed (see chapters 18 and 19). The conventional length of one of these types of interviews is between one hour and two hours, optimally ninety minutes. Less than one hour doesn’t allow for much development of questions and thoughts, and two hours (or more) is a lot of time to ask someone to sit still and answer questions. If you have a lot of ground to cover, and the person is willing, I highly recommend two separate interview sessions, with the second session being slightly shorter than the first (e.g., ninety minutes the first day, sixty minutes the second). There are lots of good reasons for this, but the most compelling one is that this allows you to listen to the first day’s recording and catch anything interesting you might have missed in the moment and so develop follow-up questions that can probe further. This also allows the person being interviewed to have some time to think about the issues raised in the interview and go a little deeper with their answers.

Standardized questionnaire with open responses ( structured interview ). This is the type of interview a lot of people have in mind when they hear “interview”: a researcher comes to your door with a clipboard and proceeds to ask you a series of questions. These questions are all the same whoever answers the door; they are “standardized.” Both the wording and the exact order are important, as people’s responses may vary depending on how and when a question is asked. These are qualitative only in that the questions allow for “open-ended responses”: people can say whatever they want rather than select from a predetermined menu of responses. For example, a survey I collaborated on included this open-ended response question: “How does class affect one’s career success in sociology?” Some of the answers were simply one word long (e.g., “debt”), and others were long statements with stories and personal anecdotes. It is possible to be surprised by the responses. Although it’s a stretch to call this kind of questioning a conversation, it does allow the person answering the question some degree of freedom in how they answer.

Survey questionnaire with closed responses (not an interview!). Standardized survey questions with specific answer options (e.g., closed responses) are not really interviews at all, and they do not generate qualitative data. For example, if we included five options for the question “How does class affect one’s career success in sociology?”—(1) debt, (2) social networks, (3) alienation, (4) family doesn’t understand, (5) type of grad program—we leave no room for surprises at all. Instead, we would most likely look at patterns around these responses, thinking quantitatively rather than qualitatively (e.g., using regression analysis techniques, we might find that working-class sociologists were twice as likely to bring up alienation). It can sometimes be confusing for new students because the very same survey can include both closed-ended and open-ended questions. The key is to think about how these will be analyzed and to what level surprises are possible. If your plan is to turn all responses into a number and make predictions about correlations and relationships, you are no longer conducting qualitative research. This is true even if you are conducting this survey face-to-face with a real live human. Closed-response questions are not conversations of any kind, purposeful or not.

In summary, the semistructured interview guide approach is the predominant form of interviewing for social science qualitative researchers because it allows a high degree of freedom of responses from those interviewed (thus allowing for novel discoveries) while still maintaining some connection to a research question area or topic of interest. The rest of the chapter assumes the employment of this form.

Creating an Interview Guide

Your interview guide is the instrument used to bridge your research question(s) and what the people you are interviewing want to tell you. Unlike a standardized questionnaire, the questions actually asked do not need to be exactly what you have written down in your guide. The guide is meant to create space for those you are interviewing to talk about the phenomenon of interest, but sometimes you are not even sure what that phenomenon is until you start asking questions. A priority in creating an interview guide is to ensure it offers space. One of the worst mistakes is to create questions that are so specific that the person answering them will not stray. Relatedly, questions that sound “academic” will shut down a lot of respondents. A good interview guide invites respondents to talk about what is important to them, not feel like they are performing or being evaluated by you.

Good interview questions should not sound like your “research question” at all. For example, let’s say your research question is “How do patriarchal assumptions influence men’s understanding of climate change and responses to climate change?” It would be worse than unhelpful to ask a respondent, “How do your assumptions about the role of men affect your understanding of climate change?” You need to unpack this into manageable nuggets that pull your respondent into the area of interest without leading him anywhere. You could start by asking him what he thinks about climate change in general. Or, even better, whether he has any concerns about heatwaves or increased tornadoes or polar icecaps melting. Once he starts talking about that, you can ask follow-up questions that bring in issues around gendered roles, perhaps asking if he is married (to a woman) and whether his wife shares his thoughts and, if not, how they negotiate that difference. The fact is, you won’t really know the right questions to ask until he starts talking.

There are several distinct types of questions that can be used in your interview guide, either as main questions or as follow-up probes. If you remember that the point is to leave space for the respondent, you will craft a much more effective interview guide! You will also want to think about the place of time in both the questions themselves (past, present, future orientations) and the sequencing of the questions.

Researcher Note

Suggestion : As you read the next three sections (types of questions, temporality, question sequence), have in mind a particular research question, and try to draft questions and sequence them in a way that opens space for a discussion that helps you answer your research question.

Type of Questions

Experience and behavior questions ask about what a respondent does regularly (their behavior) or has done (their experience). These are relatively easy questions for people to answer because they appear more “factual” and less subjective. This makes them good opening questions. For the study on climate change above, you might ask, “Have you ever experienced an unusual weather event? What happened?” Or “You said you work outside? What is a typical summer workday like for you? How do you protect yourself from the heat?”

Opinion and values questions , in contrast, ask questions that get inside the minds of those you are interviewing. “Do you think climate change is real? Who or what is responsible for it?” are two such questions. Note that you don’t have to literally ask, “What is your opinion of X?” but you can find a way to ask the specific question relevant to the conversation you are having. These questions are a bit trickier to ask because the answers you get may depend in part on how your respondent perceives you and whether they want to please you or not. We’ve talked a fair amount about being reflective. Here is another place where this comes into play. You need to be aware of the effect your presence might have on the answers you are receiving and adjust accordingly. If you are a woman who is perceived as liberal asking a man who identifies as conservative about climate change, there is a lot of subtext that can be going on in the interview. There is no one right way to resolve this, but you must at least be aware of it.

Feeling questions are questions that ask respondents to draw on their emotional responses. It’s pretty common for academic researchers to forget that we have bodies and emotions, but people’s understandings of the world often operate at this affective level, sometimes unconsciously or barely consciously. It is a good idea to include questions that leave space for respondents to remember, imagine, or relive emotional responses to particular phenomena. “What was it like when you heard your cousin’s house burned down in that wildfire?” doesn’t explicitly use any emotion words, but it allows your respondent to remember what was probably a pretty emotional day. And if they respond emotionally neutral, that is pretty interesting data too. Note that asking someone “How do you feel about X” is not always going to evoke an emotional response, as they might simply turn around and respond with “I think that…” It is better to craft a question that actually pushes the respondent into the affective category. This might be a specific follow-up to an experience and behavior question —for example, “You just told me about your daily routine during the summer heat. Do you worry it is going to get worse?” or “Have you ever been afraid it will be too hot to get your work accomplished?”

Knowledge questions ask respondents what they actually know about something factual. We have to be careful when we ask these types of questions so that respondents do not feel like we are evaluating them (which would shut them down), but, for example, it is helpful to know when you are having a conversation about climate change that your respondent does in fact know that unusual weather events have increased and that these have been attributed to climate change! Asking these questions can set the stage for deeper questions and can ensure that the conversation makes the same kind of sense to both participants. For example, a conversation about political polarization can be put back on track once you realize that the respondent doesn’t really have a clear understanding that there are two parties in the US. Instead of asking a series of questions about Republicans and Democrats, you might shift your questions to talk more generally about political disagreements (e.g., “people against abortion”). And sometimes what you do want to know is the level of knowledge about a particular program or event (e.g., “Are you aware you can discharge your student loans through the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program?”).

Sensory questions call on all senses of the respondent to capture deeper responses. These are particularly helpful in sparking memory. “Think back to your childhood in Eastern Oregon. Describe the smells, the sounds…” Or you could use these questions to help a person access the full experience of a setting they customarily inhabit: “When you walk through the doors to your office building, what do you see? Hear? Smell?” As with feeling questions , these questions often supplement experience and behavior questions . They are another way of allowing your respondent to report fully and deeply rather than remain on the surface.

Creative questions employ illustrative examples, suggested scenarios, or simulations to get respondents to think more deeply about an issue, topic, or experience. There are many options here. In The Trouble with Passion , Erin Cech ( 2021 ) provides a scenario in which “Joe” is trying to decide whether to stay at his decent but boring computer job or follow his passion by opening a restaurant. She asks respondents, “What should Joe do?” Their answers illuminate the attraction of “passion” in job selection. In my own work, I have used a news story about an upwardly mobile young man who no longer has time to see his mother and sisters to probe respondents’ feelings about the costs of social mobility. Jessi Streib and Betsy Leondar-Wright have used single-page cartoon “scenes” to elicit evaluations of potential racial discrimination, sexual harassment, and classism. Barbara Sutton ( 2010 ) has employed lists of words (“strong,” “mother,” “victim”) on notecards she fans out and asks her female respondents to select and discuss.

Background/Demographic Questions

You most definitely will want to know more about the person you are interviewing in terms of conventional demographic information, such as age, race, gender identity, occupation, and educational attainment. These are not questions that normally open up inquiry. [1] For this reason, my practice has been to include a separate “demographic questionnaire” sheet that I ask each respondent to fill out at the conclusion of the interview. Only include those aspects that are relevant to your study. For example, if you are not exploring religion or religious affiliation, do not include questions about a person’s religion on the demographic sheet. See the example provided at the end of this chapter.

Temporality

Any type of question can have a past, present, or future orientation. For example, if you are asking a behavior question about workplace routine, you might ask the respondent to talk about past work, present work, and ideal (future) work. Similarly, if you want to understand how people cope with natural disasters, you might ask your respondent how they felt then during the wildfire and now in retrospect and whether and to what extent they have concerns for future wildfire disasters. It’s a relatively simple suggestion—don’t forget to ask about past, present, and future—but it can have a big impact on the quality of the responses you receive.

Question Sequence

Having a list of good questions or good question areas is not enough to make a good interview guide. You will want to pay attention to the order in which you ask your questions. Even though any one respondent can derail this order (perhaps by jumping to answer a question you haven’t yet asked), a good advance plan is always helpful. When thinking about sequence, remember that your goal is to get your respondent to open up to you and to say things that might surprise you. To establish rapport, it is best to start with nonthreatening questions. Asking about the present is often the safest place to begin, followed by the past (they have to know you a little bit to get there), and lastly, the future (talking about hopes and fears requires the most rapport). To allow for surprises, it is best to move from very general questions to more particular questions only later in the interview. This ensures that respondents have the freedom to bring up the topics that are relevant to them rather than feel like they are constrained to answer you narrowly. For example, refrain from asking about particular emotions until these have come up previously—don’t lead with them. Often, your more particular questions will emerge only during the course of the interview, tailored to what is emerging in conversation.

Once you have a set of questions, read through them aloud and imagine you are being asked the same questions. Does the set of questions have a natural flow? Would you be willing to answer the very first question to a total stranger? Does your sequence establish facts and experiences before moving on to opinions and values? Did you include prefatory statements, where necessary; transitions; and other announcements? These can be as simple as “Hey, we talked a lot about your experiences as a barista while in college.… Now I am turning to something completely different: how you managed friendships in college.” That is an abrupt transition, but it has been softened by your acknowledgment of that.

Probes and Flexibility

Once you have the interview guide, you will also want to leave room for probes and follow-up questions. As in the sample probe included here, you can write out the obvious probes and follow-up questions in advance. You might not need them, as your respondent might anticipate them and include full responses to the original question. Or you might need to tailor them to how your respondent answered the question. Some common probes and follow-up questions include asking for more details (When did that happen? Who else was there?), asking for elaboration (Could you say more about that?), asking for clarification (Does that mean what I think it means or something else? I understand what you mean, but someone else reading the transcript might not), and asking for contrast or comparison (How did this experience compare with last year’s event?). “Probing is a skill that comes from knowing what to look for in the interview, listening carefully to what is being said and what is not said, and being sensitive to the feedback needs of the person being interviewed” ( Patton 2002:374 ). It takes work! And energy. I and many other interviewers I know report feeling emotionally and even physically drained after conducting an interview. You are tasked with active listening and rearranging your interview guide as needed on the fly. If you only ask the questions written down in your interview guide with no deviations, you are doing it wrong. [2]

The Final Question

Every interview guide should include a very open-ended final question that allows for the respondent to say whatever it is they have been dying to tell you but you’ve forgotten to ask. About half the time they are tired too and will tell you they have nothing else to say. But incredibly, some of the most honest and complete responses take place here, at the end of a long interview. You have to realize that the person being interviewed is often discovering things about themselves as they talk to you and that this process of discovery can lead to new insights for them. Making space at the end is therefore crucial. Be sure you convey that you actually do want them to tell you more, that the offer of “anything else?” is not read as an empty convention where the polite response is no. Here is where you can pull from that active listening and tailor the final question to the particular person. For example, “I’ve asked you a lot of questions about what it was like to live through that wildfire. I’m wondering if there is anything I’ve forgotten to ask, especially because I haven’t had that experience myself” is a much more inviting final question than “Great. Anything you want to add?” It’s also helpful to convey to the person that you have the time to listen to their full answer, even if the allotted time is at the end. After all, there are no more questions to ask, so the respondent knows exactly how much time is left. Do them the courtesy of listening to them!

Conducting the Interview

Once you have your interview guide, you are on your way to conducting your first interview. I always practice my interview guide with a friend or family member. I do this even when the questions don’t make perfect sense for them, as it still helps me realize which questions make no sense, are poorly worded (too academic), or don’t follow sequentially. I also practice the routine I will use for interviewing, which goes something like this:

- Introduce myself and reintroduce the study

- Provide consent form and ask them to sign and retain/return copy

- Ask if they have any questions about the study before we begin

- Ask if I can begin recording

- Ask questions (from interview guide)

- Turn off the recording device

- Ask if they are willing to fill out my demographic questionnaire

- Collect questionnaire and, without looking at the answers, place in same folder as signed consent form

- Thank them and depart

A note on remote interviewing: Interviews have traditionally been conducted face-to-face in a private or quiet public setting. You don’t want a lot of background noise, as this will make transcriptions difficult. During the recent global pandemic, many interviewers, myself included, learned the benefits of interviewing remotely. Although face-to-face is still preferable for many reasons, Zoom interviewing is not a bad alternative, and it does allow more interviews across great distances. Zoom also includes automatic transcription, which significantly cuts down on the time it normally takes to convert our conversations into “data” to be analyzed. These automatic transcriptions are not perfect, however, and you will still need to listen to the recording and clarify and clean up the transcription. Nor do automatic transcriptions include notations of body language or change of tone, which you may want to include. When interviewing remotely, you will want to collect the consent form before you meet: ask them to read, sign, and return it as an email attachment. I think it is better to ask for the demographic questionnaire after the interview, but because some respondents may never return it then, it is probably best to ask for this at the same time as the consent form, in advance of the interview.

What should you bring to the interview? I would recommend bringing two copies of the consent form (one for you and one for the respondent), a demographic questionnaire, a manila folder in which to place the signed consent form and filled-out demographic questionnaire, a printed copy of your interview guide (I print with three-inch right margins so I can jot down notes on the page next to relevant questions), a pen, a recording device, and water.

After the interview, you will want to secure the signed consent form in a locked filing cabinet (if in print) or a password-protected folder on your computer. Using Excel or a similar program that allows tables/spreadsheets, create an identifying number for your interview that links to the consent form without using the name of your respondent. For example, let’s say that I conduct interviews with US politicians, and the first person I meet with is George W. Bush. I will assign the transcription the number “INT#001” and add it to the signed consent form. [3] The signed consent form goes into a locked filing cabinet, and I never use the name “George W. Bush” again. I take the information from the demographic sheet, open my Excel spreadsheet, and add the relevant information in separate columns for the row INT#001: White, male, Republican. When I interview Bill Clinton as my second interview, I include a second row: INT#002: White, male, Democrat. And so on. The only link to the actual name of the respondent and this information is the fact that the consent form (unavailable to anyone but me) has stamped on it the interview number.

Many students get very nervous before their first interview. Actually, many of us are always nervous before the interview! But do not worry—this is normal, and it does pass. Chances are, you will be pleasantly surprised at how comfortable it begins to feel. These “purposeful conversations” are often a delight for both participants. This is not to say that sometimes things go wrong. I often have my students practice several “bad scenarios” (e.g., a respondent that you cannot get to open up; a respondent who is too talkative and dominates the conversation, steering it away from the topics you are interested in; emotions that completely take over; or shocking disclosures you are ill-prepared to handle), but most of the time, things go quite well. Be prepared for the unexpected, but know that the reason interviews are so popular as a technique of data collection is that they are usually richly rewarding for both participants.

One thing that I stress to my methods students and remind myself about is that interviews are still conversations between people. If there’s something you might feel uncomfortable asking someone about in a “normal” conversation, you will likely also feel a bit of discomfort asking it in an interview. Maybe more importantly, your respondent may feel uncomfortable. Social research—especially about inequality—can be uncomfortable. And it’s easy to slip into an abstract, intellectualized, or removed perspective as an interviewer. This is one reason trying out interview questions is important. Another is that sometimes the question sounds good in your head but doesn’t work as well out loud in practice. I learned this the hard way when a respondent asked me how I would answer the question I had just posed, and I realized that not only did I not really know how I would answer it, but I also wasn’t quite as sure I knew what I was asking as I had thought.

—Elizabeth M. Lee, Associate Professor of Sociology at Saint Joseph’s University, author of Class and Campus Life , and co-author of Geographies of Campus Inequality

How Many Interviews?

Your research design has included a targeted number of interviews and a recruitment plan (see chapter 5). Follow your plan, but remember that “ saturation ” is your goal. You interview as many people as you can until you reach a point at which you are no longer surprised by what they tell you. This means not that no one after your first twenty interviews will have surprising, interesting stories to tell you but rather that the picture you are forming about the phenomenon of interest to you from a research perspective has come into focus, and none of the interviews are substantially refocusing that picture. That is when you should stop collecting interviews. Note that to know when you have reached this, you will need to read your transcripts as you go. More about this in chapters 18 and 19.

Your Final Product: The Ideal Interview Transcript

A good interview transcript will demonstrate a subtly controlled conversation by the skillful interviewer. In general, you want to see replies that are about one paragraph long, not short sentences and not running on for several pages. Although it is sometimes necessary to follow respondents down tangents, it is also often necessary to pull them back to the questions that form the basis of your research study. This is not really a free conversation, although it may feel like that to the person you are interviewing.

Final Tips from an Interview Master

Annette Lareau is arguably one of the masters of the trade. In Listening to People , she provides several guidelines for good interviews and then offers a detailed example of an interview gone wrong and how it could be addressed (please see the “Further Readings” at the end of this chapter). Here is an abbreviated version of her set of guidelines: (1) interview respondents who are experts on the subjects of most interest to you (as a corollary, don’t ask people about things they don’t know); (2) listen carefully and talk as little as possible; (3) keep in mind what you want to know and why you want to know it; (4) be a proactive interviewer (subtly guide the conversation); (5) assure respondents that there aren’t any right or wrong answers; (6) use the respondent’s own words to probe further (this both allows you to accurately identify what you heard and pushes the respondent to explain further); (7) reuse effective probes (don’t reinvent the wheel as you go—if repeating the words back works, do it again and again); (8) focus on learning the subjective meanings that events or experiences have for a respondent; (9) don’t be afraid to ask a question that draws on your own knowledge (unlike trial lawyers who are trained never to ask a question for which they don’t already know the answer, sometimes it’s worth it to ask risky questions based on your hypotheses or just plain hunches); (10) keep thinking while you are listening (so difficult…and important); (11) return to a theme raised by a respondent if you want further information; (12) be mindful of power inequalities (and never ever coerce a respondent to continue the interview if they want out); (13) take control with overly talkative respondents; (14) expect overly succinct responses, and develop strategies for probing further; (15) balance digging deep and moving on; (16) develop a plan to deflect questions (e.g., let them know you are happy to answer any questions at the end of the interview, but you don’t want to take time away from them now); and at the end, (17) check to see whether you have asked all your questions. You don’t always have to ask everyone the same set of questions, but if there is a big area you have forgotten to cover, now is the time to recover ( Lareau 2021:93–103 ).

Sample: Demographic Questionnaire

ASA Taskforce on First-Generation and Working-Class Persons in Sociology – Class Effects on Career Success

Supplementary Demographic Questionnaire

Thank you for your participation in this interview project. We would like to collect a few pieces of key demographic information from you to supplement our analyses. Your answers to these questions will be kept confidential and stored by ID number. All of your responses here are entirely voluntary!

What best captures your race/ethnicity? (please check any/all that apply)

- White (Non Hispanic/Latina/o/x)

- Black or African American

- Hispanic, Latino/a/x of Spanish

- Asian or Asian American

- American Indian or Alaska Native

- Middle Eastern or North African

- Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

- Other : (Please write in: ________________)

What is your current position?

- Grad Student

- Full Professor

Please check any and all of the following that apply to you:

- I identify as a working-class academic

- I was the first in my family to graduate from college

- I grew up poor

What best reflects your gender?

- Transgender female/Transgender woman

- Transgender male/Transgender man

- Gender queer/ Gender nonconforming

Anything else you would like us to know about you?

Example: Interview Guide

In this example, follow-up prompts are italicized. Note the sequence of questions. That second question often elicits an entire life history , answering several later questions in advance.

Introduction Script/Question

Thank you for participating in our survey of ASA members who identify as first-generation or working-class. As you may have heard, ASA has sponsored a taskforce on first-generation and working-class persons in sociology and we are interested in hearing from those who so identify. Your participation in this interview will help advance our knowledge in this area.

- The first thing we would like to as you is why you have volunteered to be part of this study? What does it mean to you be first-gen or working class? Why were you willing to be interviewed?

- How did you decide to become a sociologist?

- Can you tell me a little bit about where you grew up? ( prompts: what did your parent(s) do for a living? What kind of high school did you attend?)

- Has this identity been salient to your experience? (how? How much?)

- How welcoming was your grad program? Your first academic employer?

- Why did you decide to pursue sociology at the graduate level?

- Did you experience culture shock in college? In graduate school?

- Has your FGWC status shaped how you’ve thought about where you went to school? debt? etc?

- Were you mentored? How did this work (not work)? How might it?

- What did you consider when deciding where to go to grad school? Where to apply for your first position?

- What, to you, is a mark of career success? Have you achieved that success? What has helped or hindered your pursuit of success?

- Do you think sociology, as a field, cares about prestige?

- Let’s talk a little bit about intersectionality. How does being first-gen/working class work alongside other identities that are important to you?

- What do your friends and family think about your career? Have you had any difficulty relating to family members or past friends since becoming highly educated?

- Do you have any debt from college/grad school? Are you concerned about this? Could you explain more about how you paid for college/grad school? (here, include assistance from family, fellowships, scholarships, etc.)

- (You’ve mentioned issues or obstacles you had because of your background.) What could have helped? Or, who or what did? Can you think of fortuitous moments in your career?

- Do you have any regrets about the path you took?

- Is there anything else you would like to add? Anything that the Taskforce should take note of, that we did not ask you about here?

Further Readings

Britten, Nicky. 1995. “Qualitative Interviews in Medical Research.” BMJ: British Medical Journal 31(6999):251–253. A good basic overview of interviewing particularly useful for students of public health and medical research generally.

Corbin, Juliet, and Janice M. Morse. 2003. “The Unstructured Interactive Interview: Issues of Reciprocity and Risks When Dealing with Sensitive Topics.” Qualitative Inquiry 9(3):335–354. Weighs the potential benefits and harms of conducting interviews on topics that may cause emotional distress. Argues that the researcher’s skills and code of ethics should ensure that the interviewing process provides more of a benefit to both participant and researcher than a harm to the former.

Gerson, Kathleen, and Sarah Damaske. 2020. The Science and Art of Interviewing . New York: Oxford University Press. A useful guidebook/textbook for both undergraduates and graduate students, written by sociologists.

Kvale, Steiner. 2007. Doing Interviews . London: SAGE. An easy-to-follow guide to conducting and analyzing interviews by psychologists.

Lamont, Michèle, and Ann Swidler. 2014. “Methodological Pluralism and the Possibilities and Limits of Interviewing.” Qualitative Sociology 37(2):153–171. Written as a response to various debates surrounding the relative value of interview-based studies and ethnographic studies defending the particular strengths of interviewing. This is a must-read article for anyone seriously engaging in qualitative research!

Pugh, Allison J. 2013. “What Good Are Interviews for Thinking about Culture? Demystifying Interpretive Analysis.” American Journal of Cultural Sociology 1(1):42–68. Another defense of interviewing written against those who champion ethnographic methods as superior, particularly in the area of studying culture. A classic.

Rapley, Timothy John. 2001. “The ‘Artfulness’ of Open-Ended Interviewing: Some considerations in analyzing interviews.” Qualitative Research 1(3):303–323. Argues for the importance of “local context” of data production (the relationship built between interviewer and interviewee, for example) in properly analyzing interview data.

Weiss, Robert S. 1995. Learning from Strangers: The Art and Method of Qualitative Interview Studies . New York: Simon and Schuster. A classic and well-regarded textbook on interviewing. Because Weiss has extensive experience conducting surveys, he contrasts the qualitative interview with the survey questionnaire well; particularly useful for those trained in the latter.

- I say “normally” because how people understand their various identities can itself be an expansive topic of inquiry. Here, I am merely talking about collecting otherwise unexamined demographic data, similar to how we ask people to check boxes on surveys. ↵

- Again, this applies to “semistructured in-depth interviewing.” When conducting standardized questionnaires, you will want to ask each question exactly as written, without deviations! ↵

- I always include “INT” in the number because I sometimes have other kinds of data with their own numbering: FG#001 would mean the first focus group, for example. I also always include three-digit spaces, as this allows for up to 999 interviews (or, more realistically, allows for me to interview up to one hundred persons without having to reset my numbering system). ↵

A method of data collection in which the researcher asks the participant questions; the answers to these questions are often recorded and transcribed verbatim. There are many different kinds of interviews - see also semistructured interview , structured interview , and unstructured interview .

A document listing key questions and question areas for use during an interview. It is used most often for semi-structured interviews. A good interview guide may have no more than ten primary questions for two hours of interviewing, but these ten questions will be supplemented by probes and relevant follow-ups throughout the interview. Most IRBs require the inclusion of the interview guide in applications for review. See also interview and semi-structured interview .

A data-collection method that relies on casual, conversational, and informal interviewing. Despite its apparent conversational nature, the researcher usually has a set of particular questions or question areas in mind but allows the interview to unfold spontaneously. This is a common data-collection technique among ethnographers. Compare to the semi-structured or in-depth interview .

A form of interview that follows a standard guide of questions asked, although the order of the questions may change to match the particular needs of each individual interview subject, and probing “follow-up” questions are often added during the course of the interview. The semi-structured interview is the primary form of interviewing used by qualitative researchers in the social sciences. It is sometimes referred to as an “in-depth” interview. See also interview and interview guide .

The cluster of data-collection tools and techniques that involve observing interactions between people, the behaviors, and practices of individuals (sometimes in contrast to what they say about how they act and behave), and cultures in context. Observational methods are the key tools employed by ethnographers and Grounded Theory .

Follow-up questions used in a semi-structured interview to elicit further elaboration. Suggested prompts can be included in the interview guide to be used/deployed depending on how the initial question was answered or if the topic of the prompt does not emerge spontaneously.

A form of interview that follows a strict set of questions, asked in a particular order, for all interview subjects. The questions are also the kind that elicits short answers, and the data is more “informative” than probing. This is often used in mixed-methods studies, accompanying a survey instrument. Because there is no room for nuance or the exploration of meaning in structured interviews, qualitative researchers tend to employ semi-structured interviews instead. See also interview.

The point at which you can conclude data collection because every person you are interviewing, the interaction you are observing, or content you are analyzing merely confirms what you have already noted. Achieving saturation is often used as the justification for the final sample size.

An interview variant in which a person’s life story is elicited in a narrative form. Turning points and key themes are established by the researcher and used as data points for further analysis.

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- University Libraries

- Research Guides

- Topic Guides

- Research Methods Guide

- Interview Research

Research Methods Guide: Interview Research

- Introduction

- Research Design & Method

- Survey Research

- Data Analysis

- Resources & Consultation

Tutorial Videos: Interview Method

Interview as a Method for Qualitative Research

Goals of Interview Research

- Preferences

- They help you explain, better understand, and explore research subjects' opinions, behavior, experiences, phenomenon, etc.

- Interview questions are usually open-ended questions so that in-depth information will be collected.

Mode of Data Collection

There are several types of interviews, including:

- Face-to-Face

- Online (e.g. Skype, Googlehangout, etc)

FAQ: Conducting Interview Research

What are the important steps involved in interviews?

- Think about who you will interview

- Think about what kind of information you want to obtain from interviews

- Think about why you want to pursue in-depth information around your research topic

- Introduce yourself and explain the aim of the interview

- Devise your questions so interviewees can help answer your research question

- Have a sequence to your questions / topics by grouping them in themes

- Make sure you can easily move back and forth between questions / topics

- Make sure your questions are clear and easy to understand

- Do not ask leading questions

- Do you want to bring a second interviewer with you?

- Do you want to bring a notetaker?

- Do you want to record interviews? If so, do you have time to transcribe interview recordings?

- Where will you interview people? Where is the setting with the least distraction?

- How long will each interview take?

- Do you need to address terms of confidentiality?

Do I have to choose either a survey or interviewing method?

No. In fact, many researchers use a mixed method - interviews can be useful as follow-up to certain respondents to surveys, e.g., to further investigate their responses.

Is training an interviewer important?

Yes, since the interviewer can control the quality of the result, training the interviewer becomes crucial. If more than one interviewers are involved in your study, it is important to have every interviewer understand the interviewing procedure and rehearse the interviewing process before beginning the formal study.

- << Previous: Survey Research

- Next: Data Analysis >>

- Last Updated: Aug 21, 2023 10:42 AM

Our systems are now restored following recent technical disruption, and we’re working hard to catch up on publishing. We apologise for the inconvenience caused. Find out more: https://www.cambridge.org/universitypress/about-us/news-and-blogs/cambridge-university-press-publishing-update-following-technical-disruption

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Doing Interview-based Qualitative Research

- > Designing the interview guide

Book contents

- Frontmatter

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Some examples of interpretative research

- 3 Planning and beginning an interpretative research project

- 4 Making decisions about participants

- 5 Designing the interview guide

- 6 Doing the interview

- 7 Preparing for analysis

- 8 Finding meanings in people's talk

- 9 Analyzing stories in interviews

- 10 Analyzing talk-as-action

- 11 Analyzing for implicit cultural meanings

- 12 Reporting your project

5 - Designing the interview guide

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 October 2015

This chapter shows you how to prepare a comprehensive interview guide. You need to prepare such a guide before you start interviewing. The interview guide serves many purposes. Most important, it is a memory aid to ensure that the interviewer covers every topic and obtains the necessary detail about the topic. For this reason, the interview guide should contain all the interview items in the order that you have decided. The exact wording of the items should be given, although the interviewer may sometimes depart from this wording. Interviews often contain some questions that are sensitive or potentially offensive. For such questions, it is vital to work out the best wording of the question ahead of time and to have it available in the interview.

To study people's meaning-making, researchers must create a situation that enables people to tell about their experiences and that also foregrounds each person's particular way of making sense of those experiences. Put another way, the interview situation must encourage participants to tell about their experiences in their own words and in their own way without being constrained by categories or classifications imposed by the interviewer. The type of interview that you will learn about here has a conversational and relaxed tone. However, the interview is far from extemporaneous. The interviewer works from the interview guide that has been carefully prepared ahead of time. It contains a detailed and specific list of items that concern topics that will shed light on the researchable questions.

Often researchers are in a hurry to get into the field and gather their material. It may seem obvious to them what questions to ask participants. Seasoned interviewers may feel ready to approach interviewing with nothing but a laundry list of topics. But it is always wise to move slowly at this point. Time spent designing and refining interview items – polishing the wording of the items, weighing language choices, considering the best sequence of topics, and then pretesting and revising the interview guide – will always pay off in producing better interviews. Moreover, it will also provide you with a deep knowledge of the elements of the interview and a clear idea of the intent behind each of the items. This can help you to keep the interviews on track.

Access options

Save book to kindle.

To save this book to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service .

- Designing the interview guide

- Eva Magnusson , Umeå Universitet, Sweden , Jeanne Marecek , Swarthmore College, Pennsylvania

- Book: Doing Interview-based Qualitative Research

- Online publication: 05 October 2015

- Chapter DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107449893.005

Save book to Dropbox

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save book to Google Drive

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

- Request Info

- Pirate Port

Research Methods

- Research Process

- Research Design & Method

- Types of Research

- Resources for Research

- Survey Research

Steps in Designing an Interview

Interview resources.

- Survey & Interview Data Analysis

- Ethical Considerations in Research

- Citation Resources This link opens in a new window

- Consider who will be interviewed

- Consider the kind of information you want from the interviews

- Consider why you want to get in-depth information on your research topic

- Make sure your questions are clear and understandable

- Do not ask leading questions

- Introduce the interviewer and the goals of the interview

- Create an order for the questions grouped by themes

- Make sure one can easily move between questions

- How will you train your interviewer to control the quality?

- Do you want a second interviewer?

- Do you want a notetaker?

- Do you want to record the interviews? If so, do you have time to transcribe the recordings?

- Where will the interview occur?

- How long will each interview take?

- How will you address terms of confidentiality?

- << Previous: Survey Research

- Next: Survey & Interview Data Analysis >>

- Last Updated: Oct 4, 2024 12:18 PM

- URL: https://libguides.whitworth.edu/ResearchMethods

The Guide to Interview Analysis

- What is Interview Analysis?

- Advantages of Interviews in Research

- Disadvantages of Interviews in Research

- Ethical Considerations in Interviews

Introduction

How to prepare for an interview, how to create an interview guide, common errors when preparing for an interview.

- Recruitment & Sampling for Research Interviews

- Interview Design

- How to Formulate Interview Questions

- Rapport in Interviews

- Social Desirability Bias

- Interviewer Effect

- Types of Research Interviews

- Face-to-Face Interviews

- Focus Group Interviews

- Email Interviews

- Telephone Interviews

- Stimulated Recall Interviews

- Interviews vs. Surveys

- Interviews vs Questionnaires

- Interviews and Interrogations

- How to Transcribe Interviews?

- Verbatim Transcription

- Clean Interview Transcriptions

- Manual Interview Transcription

- Automated Interview Transcription

- How to Annotate Research Interviews?

- Formatting and Anonymizing Interviews

- Analyzing Interviews

- Coding Interviews

- Reporting & Presenting Interview Findings

In qualitative research, interviews are invaluable for gathering rich, detailed insights into participants' experiences, perceptions, and emotions. However, the success of these interviews relies heavily on thorough preparation, which ensures that the interview process is both effective and ethical. Without proper planning, researchers risk collecting shallow or irrelevant data, which can undermine the integrity of their study. This article explores the steps necessary to prepare qualitative research interviews, common errors to avoid, and why meticulous preparation is critical for obtaining valuable data.

The importance of preparing for an interview in qualitative research cannot be overstated. Effective interview preparation facilitates smooth interviews, yielding high-quality data while respecting the participants' rights and comfort. A well-prepared interviewer develops thoughtful, open-ended interview questions directly linked to the research objectives, allowing for richer, more detailed responses. Preparation also allows the interviewer to anticipate potential challenges, such as logistical issues or sensitive topics, and address them proactively. In essence, thorough interview preparation is essential to ensure the ethical conduct of the research and the collection of meaningful, insightful data.

Preparation involves developing questions and becoming familiar with the participant's background and context. This helps build rapport and encourages participants to share openly during the interview. When participants trust the interviewer, they are more likely to provide honest, detailed responses, which enhances the quality of the data. It also helps the researcher to follow up on points of interest more effectively, as familiarity with the participant’s context enables deeper and more informed probing.

Well-prepared interviews minimize the risk of unproductive tangents. You’re less likely to ask leading questions or get sidetracked when you go into an interview with a clear strategy. It also prepares you for potential challenges, such as participants providing incomplete answers or hesitating to engage. Anticipating these issues allows you to have strategies in place to manage them, ensuring the interview remains productive.

In qualitative research, preparing for an interview is not just about drafting questions—it's about creating a conducive environment for meaningful conversation, ensuring the collection of rich, relevant data, and ultimately contributing to the overall rigour of the research.

The success of an interview is based on the quality of the preparation and research conducted before the interview. Preparation will lead to the best questions which will lead to the best data collection possible. Here are some important reminders when preparing for an interview.

Understanding the research question

The foundation of any qualitative interview lies in a clear and well-defined research question. This question shapes the interview questions you explore with your participants and determines the data you will collect. For interview preparation, research is essential to develop a thorough understanding of the topic. Researchers must review existing literature and justify the need for their research to ensure the interview questions address unexplored areas and create meaningful discussions.

Questions should encourage participants to talk freely and in detail, so the interviewer can gather rich information. For example, an interviewer might ask participants to describe a specific experience rather than asking questions that can be answered with a simple "yes" or "no". By developing a clear interview guide, the interviewer can create questions that link directly to the research question while allowing for open-ended answers.

Developing an effective interview guide

An interview guide is a structured framework used in qualitative research to direct the conversation during interviews. It is an essential tool for maintaining focus while allowing for flexibility during the interview. The guide typically consists of a list of open-ended questions or key topics for exploring participants' experiences, opinions, and feelings related to the research topic.

The purpose of an interview guide is twofold. First, it ensures that all relevant topics are covered across different interviews, enhancing consistency. Second, it allows interviewers to probe further into participants’ responses, encouraging deeper insights that align with the research objectives. Although it provides structure, the guide is not rigid, allowing for deviations based on the natural flow of the conversation, ensuring richer data collection.

In qualitative research, interview guides are typically used in semi-structured or unstructured interviews. They are especially useful for creating a balance between guiding the discussion and giving the interviewee enough freedom to share detailed, meaningful information.

Pilot testing

Before conducting the actual interview, a pilot interview is an important step. It allows the interviewer to practice conducting the interview and test the flow of the interview guide. Through a review of the pilot interview, interviewers can identify unclear or irrelevant questions and make adjustments accordingly. This process also helps interviewers estimate the time required for each interview and ensures that the guide covers all relevant topics without overwhelming the participant.

Pilot testing also gives the researcher a chance to practice asking questions naturally, adjusting to the conversational flow that qualitative interviews often require. Pilot tests can be very helpful, significantly developing a researcher's knowledge and understanding of what to expect for the actual interview.

Preparing for ethical considerations

Ethical interview preparation is essential for ensuring that participants provide informed consent and are aware of their rights throughout the study. Ethical considerations are of paramount importance to protect participants’ privacy and emotional well-being. Participants must feel secure that their responses will be kept confidential, and the interviewer must anticipate any potentially sensitive topics that might arise.

Additionally, researchers should examine the emotional or psychological risks associated with certain topics and be prepared to offer support or referrals if needed. This ensures that the interview process remains respectful and professional while collecting useful research data.

Building rapport with participants

The interviewer's ability to build rapport with participants is a vital skill that greatly influences each interview. Establishing trust at the beginning of the interview helps participants feel at ease and encourages them to talk openly. By focusing on the person rather than just the data, interviewers can facilitate more natural conversations.

Strong communication skills are necessary to maintain the flow of conversation and keep the focus on the topic. During the interviewing process, the interviewer must practice active listening, demonstrate empathy, and avoid rushing participants through their responses.

Before the interview, researchers should familiarize themselves with the participants' backgrounds, where relevant, to understand their context. During the interview, the researcher should encourage open dialogue while maintaining a non-judgmental stance. This rapport enables participants to provide richer, more detailed responses, ultimately enhancing the quality of the data collected.

Anticipating logistical challenges

Careful attention to logistics is also part of effective interview preparation. Whether the interview is in-person or remote, the interviewer must ensure the setting is conducive to open and comfortable communication. For example, interviewers should choose a quiet location and test any necessary equipment beforehand.

Being well-prepared and anticipating potential issues, such as technical difficulties or external distractions, helps to foster an enjoyable interview and allows the interviewer to focus on obtaining valuable data.

Scheduling flexibility is also important, as participants' availability may vary. Researchers should be prepared to accommodate different time zones or personal schedules to facilitate participation. This attention to logistics helps create a smooth and uninterrupted interview experience.

Analyze your interviews with ATLAS.ti

Turn your transcriptions into key insights with our powerful tools. Download a free trial today.

Designing an interview guide in qualitative research is essential for structuring in-depth conversations that capture participants' nuanced experiences and reflections. Seidman (2006) emphasizes a flexible, participant-centered approach to guide development, which balances broad thematic direction with open-ended questions, facilitating a natural conversational flow. Below, we outline key considerations for constructing an interview guide that promotes meaningful engagement in qualitative studies:

Define the research question and objectives : Clarifying the research’s focus and the specific experiences under investigation provides the foundation for an effective interview guide (Seidman, 2006). By establishing a clear scope, researchers can ensure that the guide remains aligned with the core objectives of the study.

Create a framework that outlines the main concepts to study : structuring interview guides by organizing questions into overarching themes rather than prescribing fixed questions. The guide should accommodate a series of themes that broadly frame the participant’s narrative. In Seidman’s three-interview series model, these themes progress from a life history focus to current lived experience, and finally to reflection on meaning. Each theme allows the researcher to understand the participant’s experiences deeply and within the context of their personal narrative.

Design open-ended questions about each concept : The questions have to be in every-day language, not include jargon, and reflect on operational definitions of concepts to think about how questions could be crafted about that concept. The effectiveness of an interview guide lies in its capacity to elicit detailed and authentic responses. Seidman (2006) underscores the importance of open-ended questions, which invite participants to reconstruct their experiences rather than simply answer direct prompts. Questions should encourage narrative depth, for example: "Can you describe how you first became interested in your field?" "What does a typical day look like for you in your role?" These non-directive questions foster participant agency, enabling them to emphasize details personally significant to their experience.

Verify the order of questions : Questions need to go from broad to more specific, or more sensitive, challenging and direct. Make sure you have opening and closing questions.

Add prompts and probes to questions : While open-ended questions drive the interview, it is recommended to use specific prompts to deepen understanding when necessary. Prompts such as “Can you give an example?” or “What were your thoughts at that moment?” allow the interviewer to explore topics that emerge naturally from participants' responses, while still maintaining a non-intrusive approach.

Minimize directing the conversation : To capture the participant’s authentic experience, the guide should avoid leading or suggestive questions that may direct responses toward particular themes or values. Instead of prompting participants with, "Do you find your work rewarding?" researchers might ask, "How do you feel about your experience in this role?". This non-directive approach ensures that participants provide insights shaped by their unique perspectives rather than conforming to anticipated outcomes.

Allow for flexibility and adapt to participant responses : It is important to maintain flexibility in qualitative interviewing, allowing the guide to adapt according to the participant’s narrative. If a participant organically addresses certain themes, the researcher should adjust questions to avoid redundancy and follow the natural trajectory of the conversation. This flexibility is particularly beneficial in phenomenological approaches, where understanding participants’ lived experiences takes precedence over rigid adherence to a predefined question list.

Embrace silence as a tool for reflection : The guide should remind researchers to utilize silence and pauses strategically. According to Seidman (2006), allowing participants moments of reflection can often lead to deeper, more thoughtful insights. A well-designed guide includes prompts or notes encouraging the interviewer to embrace brief silences, providing space for participants to contemplate and expand upon their answers.

Pilot and revise the interview guide : It is important to check the wording of questions and revise for leading questions that may elicit social desirability bias and other errors.

By following these steps, you can create a well-structured interview guide that balances consistency with the flexibility to explore participant responses in depth. By focusing on open-ended questions and thematic progression, researchers can explore the depth and complexity of participants' lived experiences, fostering a qualitative study rich in insight and authenticity. This method not only respects participants' agency in the interview process but also aligns with qualitative research's broader goal of understanding the human experience from a contextually grounded perspective.

While thorough preparation is key, there are several common errors that researchers may encounter during the interview preparation process.

Overloading the interview guide

One of the most frequent mistakes is creating an interview guide that is too long or packed with too many questions. This can overwhelm participants and limit the depth of their responses. A well-prepared interview guide focuses on key themes and leaves room for follow-up questions, allowing participants to explore their thoughts more fully.

Failing to account for ethical concerns

Ethical considerations are often underestimated during preparation. Researchers may overlook the need for informed consent or underestimate the emotional impact of certain topics. Ensuring that participants understand their rights and the purpose of the study, along with obtaining approval from IRBs or ethics committees, is essential for conducting ethical interviews.

Neglecting rapport-building

Some researchers may jump straight into the interview questions without establishing rapport with the participant. This can create an overly formal or uncomfortable environment where participants may hesitate to share personal insights. Taking time to build trust at the start of the interview leads to more meaningful and open conversations.

Ignoring logistical issues

Poor logistical planning can disrupt the flow of an interview. For instance, technical difficulties during remote interviews, background noise, or interruptions can affect the participant’s comfort and willingness to share. Overlooking these details can undermine the effectiveness of the interview.

Effective interview preparation in qualitative research requires a balance between understanding the research topic, designing thoughtful questions, and planning the logistical and ethical aspects of the process. Researchers can conduct interviews that yield rich, insightful data by avoiding common errors such as overloading the interview guide, leading participants, or neglecting rapport. Properly prepared interviews enhance the quality of the research and ensure a respectful and ethical experience for participants.

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods (5th ed.). Oxford University Press. https://global.oup.com/academic/product/social-research-methods-9780199689453

- Gerson, K., & Damaske, S. (2020). The science and art of interviewing. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199324286.001.0001

- Marecek, J., & Magnusson, E. (2015). Doing interview-based qualitative research: A learner’s guide. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107449893.005

ATLAS.ti is there for you at every step of your interviews

From analyzing your transcript to the key insights, ATLAS.ti is there for you. See how with a free trial.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Structured Interview | Definition, Guide & Examples

Structured Interview | Definition, Guide & Examples

Published on January 27, 2022 by Tegan George and Julia Merkus. Revised on June 22, 2023.

A structured interview is a data collection method that relies on asking questions in a set order to collect data on a topic. It is one of four types of interviews .

In research, structured interviews are often quantitative in nature. They can also be used in qualitative research if the questions are open-ended, but this is less common.

While structured interviews are often associated with job interviews, they are also common in marketing, social science, survey methodology, and other research fields.

- Semi-structured interviews : A few questions are predetermined, whereas the other questions aren’t planned.

- Unstructured interviews : None of the questions are predetermined.

- Focus group interviews : The questions are presented to a group instead of one individual.

Table of contents

What is a structured interview, when to use a structured interview, advantages of structured interviews, disadvantages of structured interviews, structured interview questions, how to conduct a structured interview, how to analyze a structured interview, presenting your results, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about structured interviews.

Structured interviews are the most systematized type of interview. In contrast to semi-structured or unstructured interviews, the interviewer uses predetermined questions in a set order.

Structured interviews are often closed-ended. They can be dichotomous, which means asking participants to answer “yes” or “no” to each question, or multiple-choice. While open-ended structured interviews do exist, they are less common.

Asking set questions in a set order allows you to easily compare responses between participants in a uniform context. This can help you see patterns and highlight areas for further research, and it can be a useful explanatory or exploratory research tool.

Structured interviews are best used when:

- You already have a very clear understanding of your topic, so you possess a baseline for designing strong structured questions.

- You are constrained in terms of time or resources and need to analyze your data efficiently.

- Your research question depends on strong parity between participants, with environmental conditions held constant.

A structured interview is straightforward to conduct and analyze. Asking the same set of questions mitigates potential biases and leads to fewer ambiguities in analysis. It is an undertaking you can likely handle as an individual, provided you remain organized.

Differences between different types of interviews

Make sure to choose the type of interview that suits your research best. This table shows the most important differences between the four types.

| Fixed questions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed order of questions | ||||

| Fixed number of questions | ||||

| Option to ask additional questions |

Reduced bias

Increased credibility, reliability and validity, simple, cost-effective and efficient, formal in nature, limited flexibility, limited scope.

It can be difficult to write structured interview questions that approximate exactly what you are seeking to measure. Here are a few tips for writing questions that contribute to high internal validity :

- Define exactly what you want to discover prior to drafting your questions. This will help you write questions that really zero in on participant responses.

- Avoid jargon, compound sentences, and complicated constructions.

- Be as clear and concise as possible, so that participants can answer your question immediately.

- Do you think that employers should provide free gym memberships?

- Did any of your previous employers provide free memberships?

- Does your current employer provide a free membership?

- a) 1 time; b) 2 times; c) 3 times; d) 4 or more times

- Do you enjoy going to the gym?

Structured interviews are among the most straightforward research methods to conduct and analyze. Once you’ve determined that they’re the right fit for your research topic , you can proceed with the following steps.

Step 1: Set your goals and objectives

Start with brainstorming some guiding questions to help you conceptualize your research question, such as:

- What are you trying to learn or achieve from a structured interview?

- Why are you choosing a structured interview as opposed to a different type of interview, or another research method?

If you have satisfying reasoning for proceeding with a structured interview, you can move on to designing your questions.

Step 2: Design your questions

Pay special attention to the order and wording of your structured interview questions . Remember that in a structured interview they must remain the same. Stick to closed-ended or very simple open-ended questions.

Step 3: Assemble your participants

Depending on your topic, there are a few sampling methods you can use, such as:

- Voluntary response sampling : For example, posting a flyer on campus and finding participants based on responses

- Convenience sampling of those who are most readily accessible to you, such as fellow students at your university