Change in the Context of Mergers & Acquisitions

Case Studies of Business Mergers and What They Teach Us!

- First Online: 09 February 2023

Cite this chapter

- Thomas Lauer 2

1331 Accesses

The following chapter presents a series of current case studies on change management in the context of mergers and acquisitions (M&A), which were researched on the basis of guided interviews. The aim of the case studies is to make the challenges of change transparent by means of practical examples and to show practical solutions for these challenges in accordance with the success factors of change management.

In the context of mergers and acquisitions (M&A), this primarily concerns the following challenges:

Overcoming different corporate cultures

Power imbalances due to enormous size differences

Cultural differences in international M&A

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Bühler, M., & Klose, N. (2017). Mehr als nur Zahlen. Warum M&A-Transaktionen scheitern und wie ein ganzheitliches Controlling zum Gelingen beitragen kann. In W. Funk & J. Rossmanith (Eds.), Internationale Rechnungslegung und Internationales controlling (pp. 445–467). Springer Gabler.

Chapter Google Scholar

Fischer, T.M., & Rademacher, M. (23. Sept. 2013). Controlling von M&A-Projekten – Konzeption und empirische Befunde in deutschen börsennotierten Unternehmen. DER BETRIEB , 13 , 645–655.

Google Scholar

Grosse-Hornke, S., & Gurk, S. (2009). Erfolgsfaktor Unternehmenskultur bei Mergers & Acquisitions. Finanzbetrieb, 2 (2009), 100–104.

IMAA Institut. (2021). https://imaa-institute.org/mergers-acquisitions-germany/ . Accessed: 25. Feb. 2021.

Jansen, S.A. (2016). Mergers & Acquisitions (6. Aufl.). Springer Gabler.

Lauer, T. (2021). Change management . Springer.

Book Google Scholar

Mercer Bing, C., & Wingrove, C. (2012). Mergers and acquisitions: Increasing the speed of change. Employment Relations Today, 2012 , 43–50.

Article Google Scholar

Weinert, S. (2008). Mergers & acquisitions. Change management als Erfolgsfaktor. In D. Fink (Ed.), Consulting Kompendium (S. 94–97) . FAZ-Institut.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Business and Law, Technical University Aschaffenburg, Aschaffenburg, Germany

Thomas Lauer

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer-Verlag GmbH, DE, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Lauer, T. (2023). Change in the Context of Mergers & Acquisitions. In: Quick Guide Change Management for all Cases . Springer Gabler, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-66625-8_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-66625-8_3

Published : 09 February 2023

Publisher Name : Springer Gabler, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN : 978-3-662-66624-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-662-66625-8

eBook Packages : Business and Management Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Successful mergers start at the top

To integrate companies following a merger, arguably the most important challenges involve the top of the organization—appointing the right top team, structuring it appropriately, defining its agenda, and building the trust that enables its members to work well together. Executives who fail to overcome these challenges are responsible for the ego clashes and politics that are often the root cause of spectacular failed mergers.

Unfortunately, recent thinking about change management no longer emphasizes the pivotal role of the top team. The consensus on how to manage change has shifted to a dispersed approach because too many initiatives designed to cascade down the hierarchy have delivered disappointing results. The usual interpretation is that top-down change fails because at every step messages get diluted, so that each succeeding one seems less compelling and less authentic.

While this may be true in certain circumstances, a merger requires direction from the top because that is the only way to initiate change throughout an organization. The change required to integrate companies cannot be driven from an entrepreneurial business unit, an innovative functional unit, or the front line. Too much coordinated, programmatic change must be achieved in too short a time for such approaches to succeed. The spirit of the project is determined at the top, where the conditions are set for the whole integration effort.

But the top team must do more than just talk about the new company, adopt its language and trappings, and act according to its norms. The team must become the new company in the full sense (see sidebar, “Who’s on the top team?”). Its messages, processes, and targets must deeply incorporate the aspirations of the new company in a way that is visible to managers, employees, and even outside observers. As the top team goes on to integrate the company down the line, it in effect re-creates itself. The company is not just rolling out messages, processes, and a set of targets; it is rolling out itself.

Who’s on the top team?

Loosely speaking, the top team includes senior managers at the relevant level—generally the corporation as a whole, but in some cases a group, a division, or a business unit that engages in mergers. The team shares general responsibility for the organization’s future. The number of people in the top team and the organizational levels represented on it are highly context specific. In some cases, the top team may be the dozen (or fewer) people who will interact regularly with the CEO, but we have seen teams with 40 or more members.

A handful of our interviewees provocatively insisted that the boards of the merging companies should be counted as part of the top team. After all, the board’s performance could have a major impact on the creation of value during the integration period and beyond. One CEO observed, “Very few companies actually change their boards as a result of a merger, but in the same way that the management team needs to be tested for whether it has the right skill set, so should the board be. The capabilities of incumbent directors should also be tested and the best chosen. After all, if the board members strike deals among themselves, what signal does this send to the management team? And if the board is polarized, it cannot provide the required leadership and support to the CEO.” The people who should serve on the board are those who can best help the new company create value.

In the best cases, members of the top team signal the kind of company they are creating and their commitment to that new company. In other cases, the team visibly lacks the requisite quality, and its weaknesses inevitably spread throughout the merging companies. The power of the signals emanating from the top team reflects the fact that they are not just signals: they create concrete realities. The important signals fall into three categories: senior appointments, the top team’s alignment, and clarity about roles.

Senior appointments

One of the most memorable things during an integration effort is the way managers, employees, and even other stakeholders closely watch to see who ends up on the top team. This attentiveness represents much more than a voyeuristic interest in the human drama taking place. The appointments provide strong clues about the new company’s direction and, more subtly, about the degree of its commitment to its proclaimed course. Managers and employees will, of course, also interpret appointments to the top team as signals about their own future.

Timing is crucial: in general, the earlier the decision-making process begins and ends, the better. In our study of 161 mergers, the early appointment of a top team was a strong predictor of the long-term performance of the combined organization.

Understanding the impact of these signals on each side of the boundary between the merging companies is critical because the signals may depart from expectations in very different ways. In the case of LSG Sky Chefs’ 1995 acquisition of Cater Air, former CEO Michael Kay told us that early decisions signaled to employees and managers of both companies that they were deeply committed to high performance. Cater Air managers faced a moment of truth when they encountered Sky Chefs’ stringent performance standards. The Sky Chefs managers faced a similar moment when they realized that their position as the acquiring company would not give them an edge in the competition for appointments. Indeed, managers on both teams, at both companies, were surprised when a number of Cater Air managers were selected for senior leadership roles in the combined company.

Appointing managers to the top team for the wrong reasons can have disastrous effects. Consider, for example, the aborted three-way merger of equals among Alcan, Algroup, and Pechiney in 1999. During early negotiations, the need to achieve at least the appearance of balance among the three partners drove the decision making. Two of their six business groups were allocated to each of them, irrespective of whether the resulting six appointees were best positioned to carry the new company forward. Had the deal gone through, Alcan CEO Dick Evans believes the same goal of political balance would have had a host of deleterious effects on decision making. “That’s probably the way we would have allocated capital and a lot of other things,” he told us. Thus, the poor handling of a standard people issue—the strongly felt need to signal inclusiveness by appointing senior managers in an equitable fashion—could have compromised the merged company’s value creation efforts long after integration was complete. In the end, the deal fell through because the three companies could not agree about which operations should be divested to meet EU conditions for antitrust approval. (After the deal fell through, Alcan acquired Algroup in 2000 and then separately acquired Pechiney in 2003, completing the original three-way merger plan of 1999.)

Creating a new company at the top is particularly problematic in a merger of equals because managers are sorely tempted to maintain the identities of the predecessor organizations. To be sure, the proclaimed strategy usually calls for their full integration. Yet compromises on people issues may fatally obstruct this effort and ultimately undermine the merged company’s pursuit of value. The resulting mess will often be attributed to “incompatible cultures,” as if the failure of integration was the inevitable result of trying to mix oil and water.

Another source of failure at the top is an unwillingness to face the prospect of job losses among close colleagues who have performed well for years—even though many more job losses are likely among people further down the line. John McGrath, the CEO of Grand Metropolitan during its 1997 combination with Guinness to form Diageo (and afterward CEO of the combined company), emphasized the importance of quickly reaching dispassionate decisions about who remains in the top team in a merger while dealing humanely with the people involved: “Just be completely ruthless in your decisions on people. If you’ve got your right people in place, I think it’s very difficult for it [a merger] not to work. Make those decisions quickly, and then treat the people decently.”

New appointments and the treatment of those who fail to get them speak volumes about the combined company’s business focus and values. One example involves a conversation McGrath had with a colleague after the integration of Grand Metropolitan and Guinness. The colleague told McGrath that people who had been let go seemed, strangely, not to feel resentful. He speculated that they didn’t, because they felt they had been treated fairly and decently. “It’s not always the size of the check; sometimes it’s how people are handled emotionally. You need to explain to them why they lost out. I must have seen 100 or 120 people on exit interviews. I cannot tell you how many references I wrote. And I still get Christmas cards from them! Although we were viewed as a fairly rough bunch at Grand Met, it was all done in quite a caring way.”

Alignment of the top team

Although appointment decisions can be difficult, at least in the end it is clear to all what has been decided. Top-team alignment, by contrast, is a rather nebulous outcome of many diverse activities. People know when a company really has it, but at various stages along the way they ask, “Are we aligned yet?”

To secure genuine alignment, many CEOs demand open debate. Kevin Sharer of Amgen, for example, insisted that each of his eight executive-committee members take a position on the planned acquisition of Immunex (a deal that closed in 2002). Amgen’s culture fostered independent thinking, but in the end every committee member felt able to support the deal publicly. That support held up throughout the integration process. “There has never been a minute of recrimination about whose deal this is,” Sharer told us. When a new company has been created at the top, senior managers become strongly aligned. It is never “my deal” or “your deal” but always “our deal.”

In a merger, the top team must fashion its own identity vis-à-vis the external world of business partners, competitors, customers, and regulators to reach this level of agreement. Our research shows that when top teams turn their attention to the external environment, they often experience a catalytic effect, which carries them past the usual internal frictions much more quickly. Compared with the pressing need to thrive in the marketplace, these frictions simply do not matter very much. As Michael Kay told us, “Whenever there were any tensions on the team, I would change the subject to customers. They got the message after a while.”

This effect is particularly striking when an external crisis suddenly emerges. At one merging company, for example, the integration of the top team had been superficial. After a period of polite behavior, open politicking broke out—a phenomenon that had undermined other mergers in the same industry. However, when a financial scandal that seriously threatened the company erupted, the team finally closed ranks. A senior manager noted that in the wake of the scandal, “Everybody knew that there was just no room anymore for internal turf battles.”

Getting to that level of agreement without a crisis is mostly a matter of discipline. A carefully limited dose of team-building exercises can also help, but with two important caveats. First, managers on both sides may have very different perspectives on what constitutes a constructive, business-like exercise. If one side perceives an activity to be a touchy-feely distraction, it is not worth doing and could be counter-productive. Second, senior managers the world over have very limited patience for time spent on anything other than “real work.” This is all the more true under the intense pressure of integration. It is best to focus on outputs whose value is clear even if they are intangible (for example, a set of behavioral norms for the new company).

Role clarity

The members of the top team share responsibility for the merging companies’ future as a whole, but they also have distinct individual responsibilities. They must work together in a complementary way not only to help the companies integrate successfully but also to lead the combined one through its other concurrent and future challenges. To do so, the team must define roles very clearly and quickly—particularly roles directly involved in the integration effort. At Diageo, that explains why McGrath accelerated the appointment process: “We had to put the center together incredibly rapidly because we needed absolute clarity on the people who were going to run the business in each of the functions and below. These people had an awful lot of involvement in the integration.”

From the perspective of a company’s long-term corporate health, the future needs of the business are an equally strong factor in defining roles. Creating the top echelon of the new company is as important for its long-term performance as for the near-term success of the integration effort.

As we saw in the case of the aborted Alcan-Algroup-Pechiney merger of 1999, it was clear that the top team could not even integrate the companies, much less lead a merged one into the future. So when Alcan acquired Algroup (2000) and Pechiney (2003), Dick Evans and his colleagues at Alcan wanted to make sure the top team could play both roles. The roles of its members were therefore defined in the clearest possible way before the company turned to identifying synergies and planning the transitions. As Evans explained, “We needed to know where the ‘ownership’ was. This meant naming the top couple of layers of management, defining the organizational structure, and settling boundary issues, such as which assets go into which business groups. That way, there is some certainty as to who is going to own any future action that needs to be taken. We felt that until you have made those decisions, it is useless to try to form an integration team.”

This example illustrates the rationale for firming up the new company at the top. Although the top team may be heavily involved in the integration effort, it is far more than a project team. It carries the responsibility for leading the company in the indefinite future and must therefore be set up with this larger responsibility in mind.

Establishing the top team poses a critical and immediate challenge for merging companies. The new company’s leaders must appoint the best possible top team for achieving its goals, and the top team’s members must be aligned around them. To collaborate effectively, its members must be clear about their individual roles. All this is sensible enough and easy to say, but in practice that degree of leadership can be hard to achieve during the hectic period leading up to a merger or even in its immediate aftermath.

David Fubini is a partner in McKinsey’s Boston office, and Colin Price is a partner in the London office. Maurizio Zollo is the Shell fellow in business and the environment and an associate professor of strategy at INSEAD, in Fontainebleau, France.

This article is adapted from the authors’ forthcoming book, Mergers: Leadership, Performance, and Corporate Health , Hampshire, (UK): Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

The authors would like to thank Jim Wendler for his contributions to this article.

This article was first published in the Autumn 2006 issue of McKinsey on Finance . Visit McKinsey’s corporate finance site to view the full issue.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Smoothing postmerger integration

M&A Change Management Strategy: High-Growth Approach (2024)

.webp)

Kison Patel is the Founder and CEO of DealRoom, a Chicago-based diligence management software that uses Agile principles to innovate and modernize the finance industry. As a former M&A advisor with over a decade of experience, Kison developed DealRoom after seeing first hand a number of deep-seated, industry-wide structural issues and inefficiencies.

Transformation. Evolution. Revolution.

Whatever world you choose, there is no denying that M&A at its core is about change - for the acquirer and the target.

Even growth, the most commonly cited motive for undertaking M&A given by managers is just a different word for change.

It’s a mystery, then, why the M&A community has largely overlooked the value of change management. This is a potentially costly oversight.

Where a business stands at the other side of change is ultimately a measure of how well it was managed.

The Change Manager Role

The easiest way to think of the change manager role is as a project manager, where the project is fundamental change for your organization.

The bigger the acquisition, the more processes, technology, job roles, structures and culture can (and indeed, should) change.

Traditional manager have neither the time nor the experience to oversee this transition, which is where change managers come in.

What is Change Management?

Change management is the process through which a company creates value from change. It takes an analytical approach and considers all of the areas which traditional M&A overlooks in the M&A process from people and values to processes and technologies.

Underestimating the Power of Change

A well-trodden maxim goes that the biggest investment anybody will make over the course of their lifetimes is their house.

And for a company?

If we’re talking about one-time investments, invariably the biggest investment that a company will ever make involves some element of M&A. That is as true for tech firms as it is for the thousands of medium-sized firms whose deals fill Capital IQ every year.

And yet, despite the transformative impact that M&A has on businesses of all sizes, change management is almost never mentioned. Perhaps managers equate the acquisition of companies with that of capital expenditure - a balance sheet addition.

Whatever the reason, it’s a potentially disastrous mistake to make. Having had privileged access to the inner workings of thousands of deals, we believe that change management deserves a role all on its own in the M&A process.

As competent as you believe your office manager or HR director to be, you can’t put them in charge of change management. Nor is it good enough to say that it’s a ‘collective responsibility.’ Being serious about M&A involves creating a dedicated change management role.

This could be a hired hand brought on board for an extended period, or someone who will fulfill the role over a series of acquisitions that your company is planning. Bringing someone of this nature onto your M&A team has several benefits:

Within your business, having a dedicated role for change creates a culture prepared for M&A. It moves from being a process based on ad hoc procedures to one where the goal is to maximize value at every stage of the process (particularly after the deal has closed).

Outside the business, the presence of a change management officer creates a smoother relationship between the buyer and its targets, before, during and after any transaction has taken place.

Perhaps this is best captured by renowned change management expert Dawn White, who says that when it comes to change management: “Methodology is the driver.”

Related : Reasons for Mergers and Acquisitions .

Methodology is the driver

Putting Dawn White’s advice into practice, we recommend that companies implement some variant of the methodology that DealRoom has constructed (see below), which is based on findings from thousands of deals.

This constitutes change management best practice and should include:

Change Management Best Practices

- Set up one-to-one interviews and focus group sessions

- Use surveys to find the big picture

- Produce a comprehensive report of your findings and present it to stakeholders

- Be sure the comprehensive report includes personalized calls to action

- Consider conducting a potential resistance analysis

Let’s now take a detailed look at these points in order.

1. One-to-one interviews and focus group sessions with the target company

Nothing sends shockwaves through a group of employees like telling them that their company is being acquired.

The mere mention of another firm on the horizon can create a siege mentality among target company employees, who all start to look around wondering whose job is first to go.

Facetime between these employees and the change manager serves to reduce this anxiety, bringing a more human aspect to the process. Employees who may have become hostile, or even left the target company, can be won over to the new vision being proposed.

Furthermore, by interviewing a broad swathe of employees within the firm - from top to bottom - the change manager can learn about the company’s internal workings, its culture and possibly even some problems that wouldn’t have been encountered without the face-to-face interaction.

2. Use surveys to flesh out the big picture

What people may be reluctant to put across in a face-to-face meeting, they should be more willing to express in a confidential survey that allows them to vent their emotions. A well-designed survey should draw out insightful answers.

For example, suppose one of the employee concerns that came up again and again during your interviews was the lack of opportunities for promotion within the firm. Fantastic - it could be that you’re going to inherit an ambitious workload. Structure the survey around this. Ask questions like “how can you contribute more to the company?” and “How could we value your contribution more than it is being valued now?”

Thus, well thought-through surveys will build on the findings from the interviews to paint a clearer picture of what’s going on.

3. Produce a comprehensive report of your findings and present it to stakeholders

By now, you should have some insightful findings which can be presented to stakeholders within the acquiring firm.

There could be a number of issues which the findings show up. For example - a lack of knowledge in a certain area, cultural problems that exist within the workforce or any number of so-called ‘soft’ (human) issues which, left unchecked, have the potential to bring down deals.

The positives and negatives drawn from the findings should be laid out in the clearest terms possible: “The positives we see in acquiring this firm are _____________ while we are somewhat concerned about _________________.”

4. Be sure the above report includes personalized calls to action

This is possibly the area in which the change management expert adds most value to the acquisition process.

By adding personalized calls to action, they assign responsibility (and by extension, accountability) to important tasks which could become sidelined otherwise. If drawn up - and of course, implemented - well, this report should be the basis for the company to drive value generating changes from this point on.

5. Consider conducting a potential resistance analysis

Similar to the face-to-face sessions with employees, a potential resistance analysis allows both sides of the acquisition to see what potential resistance (i.e. value destroyers) are within the organizations.

At this step, don’t fall into the same trap that employees may have fallen into at an earlier stage - i.e. a ‘them and us’ mentality. The idea here is to drive this forward, not to drive people out. Uncover what employees on each side are anxious about, what they see as being the negative points about the deal for them and for others, and - where they see their roles in the company’s future.

Create a mood of transparency and this will almost certainly yield some valuable insights.

Six months after the transaction, conduct a climate survey and present findings to executives

This is a repeat of the previous steps with a change in perspective: You’re now asking the questions after the fact. Some of the initial concerns expressed by employees six to nine months before could now be shown to have had real foresight. Other concerns - hopefully - will have been unfounded.

The purpose of the climate survey is to work out one from the other, how everyone is adapting to the new changes and what concerns still remain (or, more worryingly, have arisen) since the companies merged. This should all be presented to management, as before, to be dealt with as soon as possible.

Why change management is often forgotten in M&A

Because it is not tangible .

We cannot always see what is being done like we can with traditional project management - change management is often overlooked or inadvertently forgotten. Unfortunately, it is when you start seeing what is not happening (people are not embracing new culture, work is not getting done properly, and synergies are not being met) that you realize change management is not being implemented.

To combat this, M&A change management needs to be brought to the forefront and differentiated from project management .

Specifically, change management cannot be thought of in terms of tasks and checkmarks, rather it needs to be seen as an approach to make sure the people on both the acquiring side and target side are being “taken care” of across all functions.

Using change management to identify and prioritize roadblocks

One of the areas in which change management can garner the largest impact is identifying deal and synergy killers.

Using an impact analysis, change management team members can look at areas such as foreseen debt, differences in operational styles, and benefits and bring them to the forefront early on. Once these issues are identified, mitigation can begin, which ultimately gives these roadblocks less destructive power.

When early identification of issues is not wielded as a weapon against roadblocks, small issues can wreak havoc on a deal later on. We have witnessed something as seemingly simple as payroll moving from weekly to biweekly lead to problems and lack of employee retention.

Here are some strategies for prioritizing and addressing issues related to culture and change management

- Look at what is high priority to employees and ensure they are dealt with quickly - again, people are key.

- Examine and gravitate towards roadblocks that line up with the key objectives of your integration.

- Another approach is to identify low hanging fruit - simple issues that can be quickly and easily rectified - this will allow you to gain some momentum.

Overall, consider impact and effort when deciding where to start. Once you believe you have fixed an issue, change management teams should check in with both sides to see if employees truly feel/see a difference.

Where and Why You Might Face Resistance?

It is essential to remember employees from the target company might be resistant.

Remember, they did not ask to come to the purchasing company.

Some common feelings and signs of resistance are members of the target company may feel as though the purchasing company is of less value than them, or they are not interested in being a part of a new organization.

Finally, resistance may come about because the purchasing company has not put in the extra effort to truly teach the acquired company about its organization's structure and core practices or how to be successful in the new work environment.

These feelings often result in acquired employees not bringing all their energy and talent to the table.

Conclusions

Just reading through this article, you can probably get a feel for just some of the issues that tend to arise during the integration phase.

But imagine trying to conduct a deal without going through the steps we’ve just outlined.

Change management is an ongoing process.

Coming to terms with this and taking the necessary steps within your organization to accommodate for change is the first step to ensuring a successful M&A process.

Get your M&A process in order. Use DealRoom as a single source of truth and align your team.

Publications Effective Management Of Change During Merger And Acquisition

- Publications

Effective Management Of Change During Merger And Acquisition

- July 14, 2014

- Christopher Kummer

Symbiosis Institute of Management Studies Annual Research Conference (SIMSARC13)

The on-going dance of merger and acquisition happening every week is hard to miss. But it has been found that most mergers and acquisition fail because of poor handling of change management. Change is the only thing that will never change so let’s learn to adopt by change management. This paper will analyse all the factors that lead to change. The major reasons that lead to change are system dynamics, structure-focused changed, person-focused change, and profitability issues. The resistance to change can be attributed to the lack of communication, no clear vision, no proper reward system, confusion and frustration, force of habit, fear of unknown, fear of insecurity, loss of competency and lack of support.

It presents different model that can be used for change management and different theories that can be used to handle change during M&A. It also highlights the strategies this can be followed by the leaders of the organization: Integration plan, Employee Involvement, Clear Vision, Customer Focus, HR structuring and Downsizing. The factors discussed are based on the empirical findings, case study and earlier papers. To, support that the change can be managed effectively and efficiently, the paper shows as to how change was managed in the merger of ICICI bank and Bank of Madura.

1. Introduction

In mergers, two or more companies engage in some negotiation which ultimately leads to transaction. Acquisition also involves two or more companies but in acquisition the bigger company swallows the smaller company. So merger and acquisition is the process of integrating two or more companies with different values, cultures and forces into one cohesive unit. From an economic point of view, there are 2 types of mergers: Horizontal mergers and Vertical mergers. Horizontal mergers involve companies with similar area of work e.g., Chevron and Texaco. Vertical mergers involve companies with diverse area of work e.g. AOL and Time Warner.

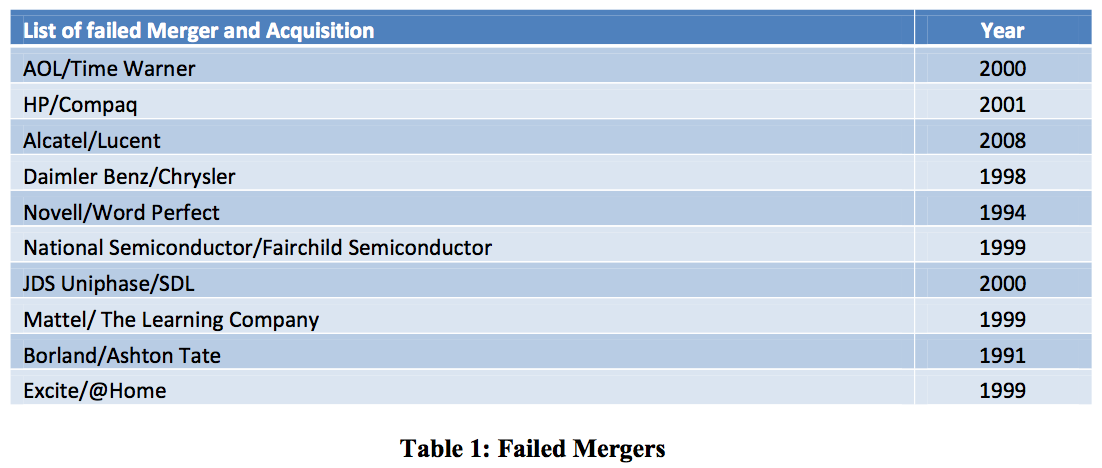

The merger is not only seen from the financial perspectives but it is the union of two different companies and two different cultures which is bound to bring some anomalies. It is very important that the concern departments should be actively involved in the process so that they under these difference and plan in an orderly manner for the smooth transition During M&A, the leaders of both the companies face many challenges: cultural management, stress management, redundancies, HR restructuring, resistance to change, job insecurity, talent drainage, low motivation etc. All the aforementioned factors are responsible for change. KPMG has found that 80% of the mergers and acquisitions fail because of improper handling of change management. Below is the list of few companies which failed miserably because of poor handling of the aforementioned reasons.

2024 M&A Mid-Year Outlook

M&A Trends and Figures in Transportation

Analysis of M&A Trends in the Metals and Mining Sector

Stay up to date with M&A news!

Subscribe to our newsletter

Keep me informed about M&A and Institute news.

M&A Statistics & Valuation

M&A Worldwide and by Region

M&A by Industries

M&A by Deal Types

M&A Education & Trainings

International M&A Certificate

Post Merger Integration

Mergers & Acquisitions Professional

In the news

Testimonials

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Privacy Overview

Are you sure you want to log out.

In order to become a charterholder you need to complete one of the IMAA programs

Unilever Change Management Case Study

In today’s fast-paced business environment, change is inevitable.

Companies need to evolve and adapt to remain competitive, but managing change is not an easy task. Effective change management is crucial to the success of any organizational transformation, as it ensures that the changes are implemented smoothly and effectively.

In this blog post, we will examine a case study of change management at Unilever, one of the world’s largest consumer goods companies.

We will explore the challenges faced by Unilever, the change management approach it took, and the results of its initiatives.

Brief History and Growth of Unilever

Unilever is a British-Dutch multinational consumer goods company that was founded in 1929 through a merger between Dutch margarine producer Margarine Unie and British soap maker Lever Brothers.

Unilever has a long history of growth through mergers and acquisitions, with notable acquisitions including Bestfoods, Ben & Jerry’s, and Dollar Shave Club.

The company operates in over 190 countries and has a diverse portfolio of products, including food and beverages, cleaning agents, beauty and personal care products.

Unilever has also been committed to sustainability and social responsibility, and in 2010, it launched the Unilever Sustainable Living Plan, which aims to reduce the company’s environmental impact and improve the health and well-being of its customers.

Today, Unilever is one of the world’s largest consumer goods companies, with a revenue of over €50 billion in 2020.

External factors that led to organizational changes at Unilever

Unilever is a multinational consumer goods company that has undergone several organizational changes over the years. Here are three external factors that led to organizational changes at Unilever:

- Changing Consumer Preferences: The changing preferences and behaviors of consumers can have a significant impact on a company’s strategy and operations. For example, as more consumers started to prioritize eco-friendliness and sustainability, Unilever had to shift its focus towards more sustainable products and packaging. This led to the introduction of products like the “Dove Refillable Deodorant” and “Omo EcoActive” laundry detergent, as well as a commitment to reduce its plastic packaging by half by 2025.

- Competitive Pressure: Competition is another external factor that can force companies to make organizational changes. For example, when Unilever faced increasing competition from other consumer goods companies in emerging markets like India and China, it had to restructure its operations to be more efficient and cost-effective. This led to the consolidation of its global supply chain, as well as a greater emphasis on localizing its products and marketing strategies to better appeal to these markets.

- Technological Advancements: Advances in technology can also lead to organizational changes, as companies need to adapt to new ways of doing business. For example, as more consumers started to shop online, Unilever had to develop a strong e-commerce presence and optimize its digital marketing efforts. This led to the creation of Unilever Digital, a team dedicated to digital marketing and e-commerce, as well as a partnership with Alibaba to expand its online distribution in China.

Internal factors that led to organizational changes at Unilever

In addition to external factors, internal factors can also lead to organizational changes at Unilever. Here are three examples of internal factors that have led to organizational changes at the company:

- Management Changes: Changes in top management can often lead to organizational changes. For example, when Paul Polman became CEO of Unilever in 2009, he initiated a major restructuring of the company that aimed to streamline operations and focus on sustainable growth. This led to the consolidation of Unilever’s foods and personal care divisions, as well as a greater focus on emerging markets and sustainability.

- Financial Performance: Poor financial performance can also prompt organizational changes. For example, in 2017, Unilever reported slower-than-expected sales growth, leading the company to undertake a strategic review of its operations. This resulted in a decision to sell or spin off Unilever’s spreads business and focus on higher-growth areas like beauty and personal care.

- Organizational Culture: Organizational culture can also drive organizational change. For example, when Unilever identified a need to become more agile and innovative, it undertook a major cultural transformation initiative called “Connected 4 Growth.” This involved restructuring the company into smaller, more autonomous business units and giving employees greater freedom to experiment and take risks. The initiative aimed to foster a more entrepreneurial culture within the company and enable faster decision-making and innovation.

05 biggest steps taken by Unilever to implement changes

Unilever is a multinational consumer goods company that has undergone several organizational changes over the years. Here are the five biggest steps taken by Unilever to implement changes:

1. Sustainable Living Plan

In 2010, Unilever launched its Sustainable Living Plan, a comprehensive sustainability strategy that aimed to reduce the company’s environmental footprint, improve social impact, and drive profitable growth. The plan set ambitious targets for Unilever to achieve by 2020, such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 50% and improving the livelihoods of millions of people in its supply chain. The Sustainable Living Plan has been a driving force behind many of Unilever’s organizational changes, such as the introduction of sustainable products and packaging and a greater emphasis on transparency and accountability.

2. Organizational Restructuring

Unilever has undertaken several major organizational restructuring initiatives over the years to streamline its operations and focus on high-growth areas. For example, in 2016, Unilever announced a plan to consolidate its foods and personal care businesses into a single division, with the goal of achieving greater efficiency and cost savings. Similarly, in 2017, Unilever announced a strategic review of its operations in response to slower-than-expected sales growth, resulting in a decision to sell or spin off its spreads business and focus on higher-growth areas like beauty and personal care.

3. Digital Transformation

As more consumers started to shop online, Unilever recognized the need to invest in its digital capabilities to stay competitive. In 2017, the company launched Unilever Digital, a team dedicated to digital marketing and e-commerce, and entered into a partnership with Alibaba to expand its online distribution in China. Unilever also invested in technology startups and acquired several digital companies to enhance its digital capabilities and drive innovation.

4. Cultural Transformation

Unilever recognized that its organizational culture needed to change to foster greater agility and innovation. In 2016, the company launched its “Connected 4 Growth” initiative, which involved restructuring the company into smaller, more autonomous business units and empowering employees to take more risks and experiment. The initiative aimed to create a more entrepreneurial culture within the company and enable faster decision-making and innovation.

5. Portfolio Transformation

Unilever has undergone several portfolio transformations over the years to focus on its core brands and divest non-core businesses. For example, in 2018, Unilever acquired the personal care and home care brands of Quala, a Latin American consumer goods company, to strengthen its presence in emerging markets. At the same time, the company divested its spreads business and announced plans to exit its tea business to focus on higher-growth areas. These portfolio transformations have helped Unilever to stay agile and adapt to changing market conditions.

05 Results of change management implemented at Unilever

The change management initiatives implemented at Unilever have had several positive outcomes and impacts. Here are some of the key examples:

- Increased Sustainability: The Sustainable Living Plan has been a key driver of Unilever’s sustainability efforts, and the company has made significant progress in reducing its environmental footprint and improving social impact. For example, by 2020, Unilever had achieved its target of sending zero non-hazardous waste to landfill from its factories, and had also reduced its greenhouse gas emissions by 46% per tonne of production.

- Improved Financial Performance: Unilever’s focus on portfolio transformation and strategic acquisitions has helped the company to improve its financial performance. For example, in 2020, the company reported a 1.9% increase in underlying sales growth and a 2.4% increase in operating profit margin.

- Enhanced Digital Capabilities: Unilever’s investments in digital transformation have enabled the company to stay competitive in a rapidly evolving digital landscape. For example, Unilever’s partnership with Alibaba has helped the company to expand its online distribution in China, while its investments in technology startups have helped to drive innovation and enhance its digital capabilities.

- Improved Organizational Agility: Unilever’s organizational restructuring and cultural transformation initiatives have helped to create a more agile and entrepreneurial company culture. This has enabled Unilever to make faster decisions and respond more quickly to changing market conditions.

- Increased Customer Satisfaction: Unilever’s focus on innovation and product development has resulted in the launch of several successful new products and brands, such as the plant-based meat alternative brand, The Vegetarian Butcher. These products have helped to increase customer satisfaction and drive growth for the company.

Final Words

Unilever’s successful implementation of change management is a testament to the company’s commitment to innovation, sustainability, and organizational excellence. By undertaking a variety of initiatives, such as the Sustainable Living Plan, organizational restructuring, digital transformation, cultural transformation, and portfolio transformation, Unilever has been able to adapt to changing market conditions and position itself for long-term success.

One key factor in Unilever’s success has been its ability to align its change management initiatives with its overall business strategy. By focusing on high-growth areas, investing in sustainability, and enhancing its digital capabilities, Unilever has been able to drive growth and improve profitability while also achieving its sustainability goals.

Another key factor has been Unilever’s emphasis on collaboration and stakeholder engagement. By working closely with suppliers, customers, and other stakeholders, Unilever has been able to create a shared sense of purpose and drive greater alignment around its sustainability and innovation goals.

About The Author

Tahir Abbas

Related posts.

Change Management Plan – Purpose and 07 Steps to Create it

05 Key Performance Indicators for Quality Assurance Department

Exploring the Types of Crisis Communication

JavaScript seems to be disabled in your browser. For the best experience on our site, be sure to turn on Javascript in your browser.

Hello! You are viewing this site in English language. Is this correct?

Explore the Levels of Change Management

9 Successful Change Management Examples for Inspiration

Joelle Goodwin

Published: October 1, 2024

Whether you're a new change practitioner or an experienced pro, this guide of helpful change management examples can help you demonstrate its power in several contexts. Share it with others to show change management's value as a tool for resilience, growth, innovation, and employee-morale enhancement.

Read on for strategies to promote an innovative, adaptable work environment and boost employee morale. You'll also explore real-world examples and Prosci's established methodology in action.

What is Change Management?

Prosci defines change management as "the application of a structured process and set of tools for leading the people side of change to achieve a desired outcome."

Simply put, it's a strategy for guiding an organization and its people through change. It goes beyond top-down orders, involving employees at all levels. A truly people-focused approach, it encourages everyone to participate actively, helping them adapt and use changes in their everyday work.

Effective change management aligns closely with a company's culture, values and beliefs. When change fits well with these cultural aspects, it feels more natural and can be easier for employees to adopt. This contributes to smoother transitions and leads to more successful organizational changes.

Why is Change Management Important?

Change management is pivotal for guiding organizations through transitions, and ensuring impactful and long-lasting results.

For example, a $28B electronic components and services company with 18,000 employees realized the importance of enhancing its processes. They knew to adopt more streamlined, efficient approaches known as Lean initiatives. However, they encountered challenges because they needed a more structured method for effectively managing the human aspects of these changes.

The company formed a specialized group focused on change to address their challenges and initiate key projects. These projects aligned with their culture of innovation and precision, which helped ensure that the changes were well-received and effectively implemented within the organization.

Matching change management to an organization's unique style and structure contributes to more effective transformations and strengthens the business for future challenges.

What Are the Main Types of Change Management?

Prosci's change management methodology includes a model for individual change, organizational strategies, enterprise-wide integration approaches, and effective portfolio management—all are vital for transformative success.

Individual change management

At Prosci, we understand that successful change begins with the individual.

The Prosci ADKAR ® Model ( Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability and Reinforcement) is expertly designed to equip change managers with tools and strategies to engage your team. It's a model that will guide and support you in helping people confidently navigate and adapt to changes.

Organizational change management

In organizational change management , we focus on the core elements of your company to fully understand and address each aspect of the change. Our approach bridges the gap between individual and organizational change, enable you to scale projects and initiatives effectively. The process includes creating tailored strategies and detailed plans that enable you to manage challenges effectively with:

- Clear communication

- Strong leadership support

- Personalized coaching

- Practical training

Our strategies are specifically aimed at meeting the diverse needs within your organization, ensuring a smooth and well-supported transition for everyone involved.

Enterprise change management capability

At the enterprise level, change management becomes an embedded practice, a core competency woven throughout the organization.

When you implement change capabilities:

- Employees know what to ask during change to reach success

- Leaders and managers have the training and skills to guide their teams during change

- Organizations consistently apply change management to initiatives

- Organizations embed change management in roles, structures, processes, projects and leadership competencies

It's a tactical effort to integrate change management into the very DNA of an organization—nurturing a culture that's ready and able to adapt to any change.

Change portfolio management

While distinct from project-level change management, managing a change portfolio is vital for an organization to stay flexible and responsive.

9 Dynamic Change Management Success Stories to Revolutionize Your Business

Prosci case studies reveal how diverse organizations spanning different sectors address and manage change. These cases illustrate how change management can provide transformative solutions from healthcare to finance:

1. Hospital system

A major healthcare organization implemented an extensive enterprise resource planning (ERP) system and adapted to healthcare reform. This case study highlights overcoming significant challenges through strategic change management:

Industry: Healthcare Revenue: $3.7 billion Employees: 24,000 Facilities: 11 hospitals

Major changes:

- Implemented a new ERP system across all hospitals

- Prepared for healthcare reform

Challenges:

- Managing significant, disruptive changes

- Difficulty in gaining buy-in for change management

- Align with culture: Strategically implemented change management to support staff, reflecting the hospital's core value of caring for people

- Focus on a key initiative: Applied change management in the electronic health record system implementation

- Integrate with existing competencies: Recognized change leadership as crucial at various leadership levels

This example shows that when change management matches a healthcare organization's values, it can lead to successful and smooth transitions.

2. Transportation department

A state government transportation department leveraged change management to effectively manage business process improvements amid funding and population challenges. This highlights the value of comprehensive change management in a public sector setting:

Industry: State Government Transportation Revenue: $1.3 billion Employees: 3,000 Challenges:

- Reduced funding

- Growing population

- Increasing transportation needs

Initiative:

- Major business process improvement

Hurdles encountered:

- Change fatigue

- Need for widespread employee adoption

- Focus on internal growth

- Implemented change management in process improvement

This department's experience teaches us the vital role of change management in successfully navigating government projects with multiple challenges.

3. Pharmaceuticals

A global pharmaceutical company navigated post-merger integration challenges. Using a proactive change management approach, they addressed resistance and streamlined operations in a competitive industry:

Industry: Pharma (Global Biopharmaceutical Company) Revenue: $6 billion Number of employees: 5,000

Recent activities: Experienced significant merger and acquisition activity

- Encountered resistance post-implementation of SAP (Systems, Applications and Products in Data Processing)

- They found themselves operating in a purely reactive mode

- Align with your culture: In this Lean Six Sigma-focused environment, where measurement is paramount, the ADKAR Model's metrics were utilized as the foundational entry point for initiating change management processes.

This company's journey highlights the need for flexible and responsive change management.

4. Home fixtures

A home fixtures manufacturing company’s response to the recession offers valuable insights on effectively managing change. They focused on aligning change management with their disciplined culture, emphasizing operational efficiency:

Industry: Home Fixtures Manufacturing Revenue: $600 million Number of employees: 3,000

Context: Facing the lingering effects of the recession

Necessity: Need to introduce substantial changes for more efficient operations

Challenge: Change management was considered a low priority within the company

- Align with your culture: The company's culture, characterized by discipline in projects and processes, ensured that change management was implemented systematically and disciplined.

This company’s experience during the recession proves that aligning change with company culture is key to overcoming tough times.

5. Web services

A web services software company transformed its culture and workspace. They integrated change management into their IT strategy to overcome resistance and foster innovation:

Industry : Web Services Software Revenue : $3.3 billion Number of employees : 10,000

Initiatives : Cultural transformation; applying an unassigned seating model

Challenges : Resistance in IT project management

- Focus on a key initiative: Applied change management in workspace transformation

- Go where the energy is: Establishing a change management practice within its IT department, developing self-service change management tools, and forming thoughtful partnerships

- I ntegrate with existing competencies: "Leading change" was essential to the organization's newly developed leadership competency model.

This case demonstrates the importance of weaving change management into the fabric of tech companies, especially for cultural shifts.

6. Security systems

A high-tech security company effectively managed a major restructuring. They created a change network that shifted change management from HR to business processes:

Industry : High-Tech (Security Systems) Revenue : $10 billion Number of employees: 57,000

Major changes : Company separation; division into three segments

Challenge : No unified change management approach

- Formed a network of leaders from transformation projects

- Go where the energy is: Shifted change management from HR to business processes

- Integrate with existing competencies: Included principles of change management in the training curriculum for the project management boot camp.

- Treat growing your capability like a change: Executive roadshow launch to gain support for enterprise-wide change management

This company’s innovative approach to restructuring shows h ow reimagining change management can lead to successful outcomes.

7. Clothing store

A major clothing retailer’s journey to unify its brand model. They overcame siloed change management through collaborative efforts and a community-driven approach:

Industry : Retail (Clothing Store) Revenue : $16 billion Number of employees : 141,000

Major change initiative : Strategic unification of the brand operating model

Historical challenge : Traditional management of change in siloes

- Build a change network : This retailer established a community of practice for change management, involving representatives from autonomous units to foster consensus on change initiatives.

The story of this retailer illustrates how collaborative efforts in change management can unify and strengthen a brand in the retail world.

A major Canadian bank initiative to standardize change management across its organization. They established a Center of Excellence and tailored communities of practice for effective change:

Industry : Financial Services (Canadian Bank) Revenue : $38 billion Number of employees : 78,000

Current state : Absence of enterprise-wide change management standards

Challenge :

- Employees, contractors, and consultants using individual methods for change management

- Reliance on personal knowledge and experience to deploy change management strategies

- Build a change network: The bank established a Center of Excellence and created federated communities of practice within each business unit, aiming to localize and tailor change management efforts.

This bank’s journey in standardizing change management offers valuable insights for large organizations looking to streamline their processes.

9. Municipality

You can learn from a Canadian municipality’s significant shift to enhance client satisfaction. They integrated change management across all levels to achieve profound organizational change and improved public service:

Industry : Municipal Government (Canadian Municipality) Revenue : $1.9 billion Number of employees : 3,000

New mandate:

- Implementing a new deliberate vision focusing on each individual’s role in driving client satisfaction

Nature of shift :

- A fundamental change within the public institution

Scope of impact :

- It affected all levels, from leadership to front-line staff

Solution :

- Treat growing your capability like a change: Change leaders promoted awareness and cultivated a desire to adopt change management as a standard enterprise-wide practice.

The municipality's strategy shows us how effective change management can significantly improve public services and organizational efficiency.

6 Tactics for Growing Enterprise Change Management Capability

Prosci's exploration with 10 industry leaders uncovered six primary tactics for enterprise change growth , demonstrating a "universal theme, unique application" approach.

This framework goes beyond standard procedures, focusing on developing a deep understanding and skill in managing change. It offers transformative tactics, guiding organizations towards excelling in adapting to change. Here, we uncover these transformative tactics, guiding organizations toward mastery of change.

1. Align with Your culture

Organizational culture profoundly influences how change management should be deployed.

Recognizing whether your organization leans towards traditional practices or innovative approaches is vital. This understanding isn't just about alignment; it's an opportunity to enhance and sometimes shift your cultural environment.

When effectively combined with an organization's unique culture, change management can greatly enhance key initiatives. This leads to widespread benefits beyond individual projects and promotes overall growth and development within the organization.

Embrace this as a fundamental tool to strengthen and transform your company's cultural fabric.

2. Focus on key initiatives

In the early phase of developing change management capabilities, selecting noticeable projects with executive backing is important.

This helps demonstrate the real-world impact of change management, making it easier for employees and leadership to understand its benefits. This strategy helps build support and maintain the momentum of change management initiatives within your organization.

Focus on capturing and sharing these successes to encourage buy-in further and underscore the importance of change management in achieving organizational goals.

3. Build a change network

Building change capability isn't just about a few advocates but creating a network of change champions across your organization.

This network, essential in spreading the message and benefits of change management, varies in composition but is universally crucial. It could include departmental practitioners, business unit leaders, or a mix of roles working together to enhance awareness, credibility, and a shared purpose.

Our Best Practices in Change Management study shows that 45% of organizations leverage such networks. These groups boost the effectiveness of change management and keep it moving forward.

4. Go where the energy is

To build change capabilities throughout an organization effectively, the focus should be on matching the organization's current readiness rather than just pushing new methods.

Identify and focus on parts of your organization that are ready for change. Align your change initiatives with these sectors. Involve senior leaders and those enthusiastic about change to naturally generate demand for these transformations.

Showcasing successful initiatives encourages a collaborative culture of change, making it an organic part of your organization's growth.

5. Integrate with existing competencies

Change management is a vital skill across various organizational roles.

Integrating it into competency models and job profiles is increasingly common, yet often lacks the necessary training and tools.

When change management skills expand beyond the experts, they become an integral part of the organization's culture—nurturing a solid foundation of effective change leadership.

This approach embeds change management deeper within the company and cultivates leaders who can support and sustain this essential practice.

6. Treat growing your capability like a change

Growing change capability is a transformative journey for your business and your employees. It demands a structured, strategic approach beyond telling your network that change is coming.

Applying the ADKAR Model universally and focusing on your organization's unique needs is pivotal. It's about building awareness, sparking a desire for change across the enterprise, and equipping employees with the knowledge and skills for effective, lasting change.

Treating capability-building like a change ensures that change management becomes a core part of your organization's fabric, benefitting every team member.

These six tactics are powerful tools for enhancing your organization's ability to adapt and remain resilient in a rapidly changing business environment.

Comprehensive Insights From Change Management Examples

These diverse change management examples provide field-tested savvy and offer a window into how varied organizations successfully manage change. Case studies , from healthcare reform to innovative corporate restructuring, exemplify how aligning with organizational culture, building strong change networks, and focusing on tactical initiatives can significantly impact change management outcomes.

To learn more about partnering with Prosci for your next change initiative, explore our consulting and Advisory Services , enterprise training options, and Change Management Certification Program .

Joelle Goodwin is a Senior Account Manager with six years of experience enabling enterprise clients with customized change management programs and solutions. Her passion is to help clients navigate the right change solution that fits their culture, budget and needs, ultimately driving client success with change maturity. Previously, she held roles supported Prosci program attendees in the classroom as a subject matter expert on the Prosci Methodology and all role-based training. Today, Joelle supports enterprise clients in higher education, government, nonprofit and life sciences as they look to advance their change skills.

See all posts from Joelle Goodwin

You Might Also Like

Enterprise - 8 Mins

The Case for Resistance Prevention in Change Management

Tips on How to Effectively Manage Change in the Workplace

Subscribe here.

- Language English Dari Pashto

- Sign up As Job Seeker As Employer

Agency Coordinating Body for Afghan Relief and Development

Position title: child protection officer ( case management and mhpss).

Activation Date: 24 October, 2024 Announced Date: 23 October, 2024 Expire Date: 02 November, 2024

About Save the Children:

We employ approximately 25,000 people across the globe and work on the ground in over 100 countries to help children affected by crises, or those that need better healthcare, education and child protection. We also campaign and advocate at the highest levels to realize the right of children and to ensure their voices are heard.

We are working towards three breakthroughs in how the world treats children by 2030:

• No child dies from preventable causes before their 5th birthday

• All children learn from a quality basic education and that,

• Violence against children is no longer tolerated

We know that great people make a great organization and that our employees play a crucial role in helping us achieve our ambitions for children. We value our people and offer a meaningful and rewarding career, along with a collaborative and inclusive workplace where ambition, creativity, and integrity are highly valued.

SCI - Afghanistan

Save the Children has been working in Afghanistan since 1976. Our way of working close to people and on their own terms has enabled us to deliver lasting change to tens of thousands of children in the country. The UN Convention of the Rights of the Child is the basis of our work.

We are helping children get a better education, we make it possible for more boys and girls to attend school, we help children protect themselves and influence their own conditions. We work with families, communities and health workers in homes, clinics and hospitals to promote basic health in order to save lives of children and mothers.

Job Description:

CHILD SAFEGUARDING:

Level 2: either the role holder will have access to personal data about children and/or young people as part of their work; or they will be working in a ‘regulated’ position (accountant, barrister, solicitor, legal executive); therefore, a police check will be required (at ‘standard’ level in the UK or equivalent in other countries).

ROLE PURPOSE: The CP MHPSS and Case Management Officer will play a critical role in delivering high-quality child protection and psychosocial support (PSS) services to children and families in Maidan Wardak Province. The officer will manage the identification, referral, and case management of children facing protection risks, including survivors of violence, unaccompanied and separated children, children with disabilities, and those affected by family separation. This position involves working closely with local communities and partners to provide integrated services through a community-based approach, including the establishment and oversight of Child-Friendly Spaces (CFS).

SCOPE OF ROLE:

Reports to: Child Protection Coordinator

Staff reporting to this post: Caseworker

Indirect : TBC

Budget Responsibilities: N/A

Role Dimensions: Coordination, communication with stakeholders, team member,beneficiaries)

Case Management and Psychosocial Support

- Lead case management processes for children at risk, including identification, registration, assessment, referral, and follow-up, ensuring compliance with national and international standards.

- Provide direct psychosocial support to children and families, including one-on-one counseling and group activities in Child-Friendly Spaces (CFS).

- Work closely with other team members and external service providers to ensure proper referral mechanisms and the provision of services such as health, education, and legal assistance.

- Facilitate the safe and timely reunification of separated children with their families, where applicable.

- Ensure appropriate documentation and case management tracking for all cases, maintaining confidentiality and data protection in line with Save the Children’s guidelines.

Establishment of Child-Friendly Spaces (CFS)

- Support the establishment, operation, and monitoring of mini and mobile Child-Friendly Spaces (CFS) in collaboration with health centers and outreach teams.

- Develop activity plans for CFS that focus on children’s mental health, emotional well-being, and recreational needs, ensuring participation and inclusion of all children, including girls, children with disabilities, and marginalized groups.

- Ensure the integration of Explosive Ordnance Risk Education (EORE) and awareness on other protection risks such as child labor into CFS programming.

Community Engagement and Mobilization

- Engage with community leaders, parents, caregivers, and local authorities to raise awareness about child protection risks and available services.

- Conduct community-based awareness and capacity-building sessions on child protection and psychosocial well-being.

- Support community Child Protection Action Networks (CPANs) and other community groups to monitor child protection issues, identify risks, and support children in need of assistance.

Monitoring and Reporting

- Work closely with the Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability, and Learning (MEAL) team to collect, analyze, and report on project data, ensuring accuracy and timely submission of reports.

- Contribute to regular project review meetings and evaluations, ensuring that findings and lessons learned are documented and shared for continuous improvement.

- Prepare detailed case management reports, success stories, and case studies for internal use and donor reporting.

Team Leadership and Capacity Building

- Provide training, coaching, and mentorship to Case Workers, community volunteers, and other relevant staff on child protection case management, psychosocial support, and child safeguarding.

- Ensure that team members adhere to Save the Children’s child safeguarding policies and protocols and that any safeguarding concerns are promptly addressed.

Coordination and Networking

- Establish and maintain relationships with relevant stakeholders, including local government authorities, community-based organizations, and national/international NGOs.

- Actively participate in child protection coordination meetings and working groups at the provincial and national levels.

- Work collaboratively with other sectors (Health, Education, Nutrition) to ensure an integrated approach to child protection.

- Any other tasks relate to child protection programs given by line manager

BEHAVIOURS (Values in Practice )

Accountability:

- Holds self-accountable for making decisions, managing resources efficiently, achieving results together with children and role modelling Save the Children values;

- Sets ambitious and challenging goals for self and team, takes responsibility for own personal development and encourages team to do the same;

- Widely shares personal vision for Save the Children, engages and motivates others;

- Future oriented, thinks strategically and on a global scale.

Collaboration:

- Builds and maintains effective relationships, with own team, colleagues at both national and regional level members, donors and partners;

- Values diversity, sees it as a source of competitive strength;

- Approachable, good listener, easy to talk to.

Creativity:

- Develops and encourages new and innovative solutions.

- Willing to take disciplined risks.

- Honest, encourages openness and transparency.

- Always acts in the best interests of children.

Equal Opportunities

The role holder is required to carry out the duties in accordance with the SCI Equal Opportunities and Diversity policies and procedures.

Child Safeguarding:

We need to keep children safe so our selection process, which includes rigorous background checks, reflects our commitment to the protection of children from abuse.

Health and Safety

The role holder is required to carry out the duties in accordance with SCI Health and Safety policies and procedures.

Job Requirements:

QUALIFICATIONS

- 16th grade graduate

- Well communicate in Dari, Pashto and English

- Knowledge of Child Protection, Case management and MHPSS

- University degree in Psychology, Social Work, Law, or a related field.

- At least 2 years of relevant work experience in child protection, case management, and/or psychosocial support, particularly in conflict or post-conflict settings.

- Experience in providing direct psychosocial support and case management to children and families.

- Familiarity with Child-Friendly Spaces (CFS) operations and community-based protection approaches.

- Strong organizational skills and attention to detail in managing cases and maintaining records.

- Ability to work collaboratively with communities and multi-disciplinary teams.

- Knowledge of child protection issues, particularly in emergency settings, including Caring for Child Survivors

- Strong communication and interpersonal skills, with fluency in English and Dari/Pashto (preferred)..

- Should have enough knowledge of case management principles and Do No Harm Policy

- Being able to travel within the province and outside the province.

- Experience working with marginalized and nomadic communities.

- Previous experience working in Afghanistan or similar contexts.

Submission Guideline:

Qualified applicants are highly encouraged to apply for the position by filling in the online application form. In addition to the online application form, they can also attach their CV and cover letter in the online system. Please note that only the applications received through the online portal will be considered for this position.

https://hcri.fa.em2.oraclecloud.com/hcmUI/CandidateExperience/en/sites/CX_1/job/10069/?amp;locationId=300000000345568&locationLevel=country&mode=location&lastSelectedFacet=LOCATIONS&location=Afghanistan&locationId=300000000341839&locationLevel=country&mode=location&selectedLocationsFacet=300000000341839

Applicants can login to the online application system by copying and pasting the following link intro their web browser. Returning users will need to enter their username and password, first time users will need to create a user account.

It is recommended that you save your username and password for future job applications through the online system.

Save the Children International (SCI) is committed to fostering diversity, equity, and inclusion as core to our vision and values. We provide equitable employment opportunities and aim to increase the representation of women, people with disabilities, and individuals from minority groups to effectively meet the diverse needs of the children and communities we serve.

At SCI, we value the authentic selves of everyone, including you! If you have any access needs or require support due to a disability or other reasons, please let us know at the time of your application. We are here to assist you and ensure an accessible and inclusive recruitment experience.

Please note: SCI does not request any fees during any stage of the recruitment process.