History of the Soviet Union

Education in the Soviet Union

Education in the Soviet Union was guaranteed as a constitutional right to all people provided through state schools and universities. The education system that emerged after the establishment of the Soviet Union in 1922 became internationally renowned for its successes in eradicating illiteracy and cultivating a highly educated population. Its advantages were total access for all citizens and post-education employment. The Soviet Union recognized that the foundation of their system depended upon an educated population and development in the broad fields of engineering, the natural sciences, the life sciences and social sciences, along with basic education.

An important aspect of the early campaign for literacy and education was the policy of "indigenisation" (korenizatsiya). This policy, which lasted essentially from the mid-1920s to the late 1930s, promoted the development and use of non-Russian languages in the government, the media, and education. Intended to counter the historical practices of Russification, it had as another practical goal assuring native-language education as the quickest way to increase educational levels of future generations. A huge network of so-called "national schools" was established by the 1930s, and this network continued to grow in enrollments throughout the Soviet era. Language policy changed over time, perhaps marked first of all in the government's mandating in 1938 the teaching of Russian as a required subject of study in every non-Russian school, and then especially beginning in the latter 1950s a growing conversion of non-Russian schools to Russian as the main medium of instruction. However, an important legacy of the native-language and bilingual education policies over the years was the nurturing of widespread literacy in dozens of languages of indigenous nationalities of the USSR, accompanied by widespread and growing bilingualism in which Russian was said to be the "language of internationality communication."

In 1923 a new school statute and curricula were adopted. Schools were divided into three separate types, designated by the number of years of instruction: "four year", "seven year" and "nine year" schools. Seven and nine-year (secondary) schools were scarce, compared to the "four-year" (primary) schools, making it difficult for the pupils to complete their secondary education. Those who finished seven-year schools had the right to enter Technicums. Only nine-year school led directly to university-level education.

The curriculum was changed radically. Independent subjects, such as reading, writing, arithmetic, the mother tongue, foreign languages, history, geography, literature or science were abolished. Instead school programmes were subdivided into "complex themes", such as "the life and labour of the family in village and town" for the first year or "scientific organisation of labour" for the 7th year of education. Such a system was a complete failure, however, and in 1928 the new programme completely abandoned the complex themes and resumed instruction in individual subjects.

All students were required to take the same standardised classes. This continued until the 1970s when older students began being given time to take elective courses of their own choice in addition to the standard courses. Since 1918 all Soviet schools were co-educational. In 1943, urban schools were separated into boys and girls schools. In 1954 the mixed-sex education system was restored.

Soviet education in 1930s–1950s was inflexible and suppressive. Research and education, in all subjects but especially in the social sciences, was dominated by Marxist-Leninist ideology and supervised by the CPSU. Such domination led to abolition of whole academic disciplines such as genetics. Scholars were purged as they were proclaimed bourgeois during that period. Most of the abolished branches were rehabilitated later in Soviet history, in the 1960s–1990s (e.g., genetics was in October 1964), although many purged scholars were rehabilitated only in post-Soviet times. In addition, many textbooks - such as history ones - were full of ideology and propaganda, and contained factually inaccurate information (see Soviet historiography). The educational system’s ideological pressure continued, but in the 1980s, the government’s more open policies influenced changes that made the system more flexible . Shortly before the Soviet Union collapsed, schools no longer had to teach subjects from the Marxist-Leninist perspective at all.

Another aspect of the inflexibility was the high rate at which pupils were held back and required to repeat a year of school. In the early 1950s, typically 8–10% of pupils in elementary grades were held back a year. This was partly attributable to the pedagogical style of teachers, and partly to the fact that many of these children had disabilities that impeded their performance. In the latter 1950s, however, the Ministry of Education began to promote the creation of a wide variety of special schools (or "auxiliary schools") for children with physical or mental handicaps. Once those children were taken out of the mainstream (general) schools, and once teachers began to be held accountable for the repeat rates of their pupils, the rates fell sharply. By the mid-1960s the repeat rates in the general primary schools declined to about 2%, and by the late 1970s to less than 1%.

The number of schoolchildren enrolled in special schools grew fivefold between 1960 and 1980. However, the availability of such special schools varied greatly from one republic to another. On a per capita basis, such special schools were most available in the Baltic republics, and least in the Central Asian ones. This difference probably had more to do with the availability of resources than with the relative need for the services by children in the two regions.

In the 1970s and 1980s, approximately 99.7% of Soviet people were literate.

We value your feedback. If you find any missing, misleading, or false information, please let us know. Please cite the specific story and event, briefly explain the issue, and (if possible) include your source(s). Also, if you encounter any content on our site you suspect might infringe copyright protections, do let us know. We are committed to respecting intellectual property rights and will promptly address any issues raised. Thank you.

Soviet Education

on the World Today

MANY Soviet refugees in Western Europe and America count the Soviet system of education as the best feature of the Soviet social order. Certainly tremendous emphasis is placed upon education both by the rulers and by the ruled. The regime has an immediate interest in the training of specialists to carry out its program of rapid economic, political, and military expansion, as well as a long-range interest in molding the “new Soviet man.” The people have different but parallel interests: to attain the economic and social privileges of the new Soviet intelligentsia and to satisfy their own genuine thirst for knowledge.

Soviet leaders have given no indication that they share the fear attributed to an early nineteenth century tsarist minister of education, that “to teach the mass of people, or even the majority of them, how to read will bring more harm than good.” Despite rapid strides toward popular education in the latter nineteenth and early twentieth century, 67 per cent of the people of Russia were illiterate in 1914. In 1939 less than 20 per cent were illiterate, and of those more than half were over fifty years of age. With the end of World War II, strong measures were undertaken to combat increases in illiteracy caused by wartime disruptions of schooling.

The reduction of illiteracy has been accomplished largely by the introduction of universal compulsory education through the seventh grade. The school population of Russia in 1914 was under 8 million; in 1939, with a total population increase of about 20 per cent, the school population was over 32 million.

Equally impressive is the increase in facilities for higher education. In 1914 there were in Russia about 90 institutions of higher education, with about 110,000 students. In 1952 there were some 900 institutions of higher education, with about 974,000 full-time students.

A small percentage of Soviet children between the ages of three and seven go to kindergarten, for which a small tuition fee must be paid. Compulsory schooling starts at the age of seven, and continues through seven grades. Those who intend to go on enter so-called ten-year schools, instead of the seven-year schools. The avowed aim of Soviet educators, from the beginning, has been to make the ten-year education compulsory. Nevertheless, in 1940 tuition fees — 200 rubles a year in Moscow, Leningrad, and the capitals of the republics, 150 rubles elsewhere — were introduced for the eighth, ninth, and tenth grades, with exemptions for certain groups, such as children of disabled veterans. Even before this, however, less than 20 per cent went on from seventh grade to “junior high.”

Some—probably less than 8 per cent—of the graduates of the seven-year school go to special four-year professional and technical high schools (technicums), to be trained as junior specialists in some branch of science, industry, the arts, medicine, education, and the like. There the tuition fees are the same as for the eighth, ninth, and tenth grades.

Something like 20 per cent of the graduates of the seven-year school are conscripted into the State Labor Reserves for four years, where they receive free on-the-job schooling.

Soviet colleges

Upon graduation from ten-year secondary schools and from professional and technical high schools (and usually after two years of military training), roughly one out of five enters higher educational institutions for specialized training. Admission is on the basis of nation-wide competitive examinations. Tuition fees are from 300 to 500 rubles a year — again with exemptions for certain groups, including Heroes of the Soviet Union and Heroes of Socialist Labor as well as “A ” students. Stipends are paid to “good” students, who comprise about 80 per cent of the total number.

As in Europe generally, there is no liberal arts college. A higher educational institution falls into one of the following categories: industry and construction, transport and communications, agriculture, public health, teacher training, social sciences, the arts. The emphasis is on the training of specialists— though that training is by no means narrow. Only about 10 per cent of the Soviet colleges are devoted to either the arts or the social sciences.

Moscow University, with over 14,000 students, including those taking correspondence courses, has eleven different divisions and trains students in fifty different specialties. Leningrad University is slightly larger. Other large universities are at Tiflis, Kiev, Riga (once Latvian), and Lvov (once Polish). All told there are twenty-three city universities.

The organization of Soviet schools and colleges is highly centralized. The general pattern is set by the Council of Ministers of the U.S.S.R., which issues decrees, allocates funds, and determines basic educational policies. Institutions of higher education are directly under the All-Union Ministry of Higher Education. Most of the other schools are under the ministry of education of the republic in which they are situated. Teachers are appointed and given their salaries — which are quite low in the Soviet scale—by the ministry through its local branches.

What they study

The ministries of education implement decisions of the Council of Ministers through detailed instructions which cover every aspect of the curriculum. Each course has its syllabus, from first grade up through postgraduate studies. There is no choice of subjects. From the fourth grade on there are national examinations, written and oral, held at particular times throughout the country.

At the end of the ten-year school, students are examined in the following subjects: Russian language, literature, mathematics (algebra, geometry, trigonometry), physics, chemistry, history (history of the U.S.S.R., modern history), and a foreign language. In non-Russian-speaking areas an examination is also given in the students’ native language. Besides the subjects in which there are examinations before graduation, the ten-year school curriculum includes natural history, geography, Constitution of the U.S.S.R., astronomy, military and physical training, design, drawing, and singing.

Since 1940, either English, German, or French has been required from the fifth grade on. Which language is taught in any school depends on the teacher; in one school it may be English only, in another German. In addition, there is at least one Soviet school where the language of instruction is English, and the students while in school are supposed to converse with each other only in English. Latin, which was reintroduced in the law schools and some other higher educational institutions in the thirties, was in 1952 restored in the secondary schools as well.

Dewey in Russia

With education as with almost everything else of importance in Soviet society, it has not always been so. Soviet education in the twenties and early thirties was dominated by radical ideas similar to those which have caused a stir in the United States. Emphasis was on “spontaneous education,” “learning from life”; the classroom was conceived as a kind of laboratory in which the teacher organized the work around projects, many of which were left to the pupils’ own initiative. Instruction was played down. Special subjects were not taught, but instead were supposed to be learned incidentally, by “doing.” American educational experiments, such as the Dalton Plan evolved by Helen Parkhurst in Dalton, Massachusetts, and others undertaken by the followers of John Dewey, had a great influence on this first phase of Soviet educational development.

Characteristically, Soviet extremism made our reforms seem modest. The Soviets anticipated the gradual “withering away” of the school altogether.

Hy a series of sweeping decrees starting in 103*2 and continuing through 1949 and 1914, Soviet progressive education has been almost entirely scrapped. A 1992 decree abolished the Dalton Plan and the project method, and introduced the three IPs. In 1994 a decree on the teaching of history ordered “the observance of historical and chronological sequence in the exposition of historical events,” and stated that facts, names, and dates should receive due emphasis. In 1997 “polytcchnism” — that is, the organization of the curriculum around labor — was under heavy fire.

Research in problems of polytechnics was abandoned, and subjects of the conventional type came to prevail in the curricula. Iiy 1999 polyteehnism was out, though the name crops up from time to time.

In 1943, separate schools for boys and for girls were introduced in eighty large cities, and later elsewhere. “Coeducation,” said the then People’s Commissar for Education, “makes no allowance for differences in the physical development of boys and girls, for variations required by the sexes in preparing each for their future life work.” However, coeducation was not completely abolished, and there has been a frank and vigorous debate in the Soviet press on the relative merits of the two systems.

The new discipline

The proponents of separate education have stressed the practical desirability of military training for schoolboys and of special training for girls in homemaking and motherhood; more fundamentally, however, the argument has been that separate education promotes better discipline. A few weeks after the decree on separate education, the education authorities promulgated twenty “Rules for School Children,” imposing obligations of conscientious study, good behavior in school and after school, neatness, respect for teachers, and so forth. Rule 9 states that pupils must rise when the teacher enters or leaves the room. Rule 12 requires that upon meeting a teacher in the streets students must give a polite bow, and the boys must remove their hats. A “pupil’s card,” on the back of which the rules are printed, must be carried at all times.

Punishments may now be administered, including admonition, ordering the delinquent to rise from his seat or to leave the room, and expulsion from sehool “The absence of punishment demoralizes the will of the school child,” Pravda stated in 1944. However, corporal punishment is forbidden— though it is apparently sometimes practiced.

The changes in educational policy in the past fifteen to twenty years represent a new philosophy not only of education but of human nature itself. A 1936 decree of the Central Committee of the Party, which attacked psychological testing of school children, established the basic premises of the new educational policy by emphasizing the power of man, by training and self-training, to overcome both his heredity and his environment. Man can lift himself by his bootstraps. More than that, he is responsible for doing so — and for failing to do so. The new policy stresses the responsibility of the pupil. He is no longer an end in himself. His sense of duty must be actively directed and developed.

The schooling of patriots

The political implications of this philosophy are not concealed. The schools are required “to educate the youth in the spirit of unrestrained love for the Motherland and devotion to Soviet authority.” The Young Communist League (Komsomol) with 16 million members between the ages of fourteen and twenty-six is supposed to “show the way” in combating “ideological neutrality.” “The most important task of the Komsomol organization,” states a handbook of 1947, “is to instill into all the youth Soviet patriotism, Soviet national pride, the aspiration to make our Soviet State even stronger.”

The patriotic, military, and moral emphasis of Komsomol and school activity is implemented by indoctrination in Marxist theory, as redefined by Lenin and Stalin. Political propaganda permeates the curriculum. School children are taught the superiority of the “Soviet” biology of Michurin and Lysenko over “bourgeois” biology. In studying Shakespeare, students are taught Marx’s views of the development of English capitalism; Hamlet is seen in part as an exposure of a decadent court aristocracy.

“Marxism-Leninism" is a required course in all Soviet institutions of higher education. Doctors’ dissertations in all fields must be ideologically correct, and there is even some indication that degrees may be revoked years later if “mistakes” in them are discovered.

In many fields, education is open to talent. But “pull" is also an importanl factor: the son of a high Party official gets many privileges in education as elsewhere. Also any indication of dissent from Party doctrine can have serious consequences extending even to imprisonment. For the student without high Party connections, the main criterion in admission to engineering schools or law schools or agronomist schools or teachers colleges is ability, as shown in examinations— including, of course, the examination in Marxism-Leninism.

From the “Best-in-the World” Soviet School to a Modern Globally Competitive School System

- Open Access

- First Online: 24 April 2020

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Isak Froumin 2 &

- Igor Remorenko 3

27k Accesses

5 Citations

2 Altmetric

The dramatic story of moving from knowledge-based to competence-based education is the main focus of the chapter. This transition was very difficult because many people believed that the Soviet schools were best-in-the-world, because teachers and parents were not ready to change the schools. The paradigm change in Russian education has still heterogenic impact on schools, assessment system, education policy, curricula.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Russian Federation: At a Conceptual Crossroads

Poland: the learning environment that brought about a change.

Competence-based Education in the Italian Context: State of Affairs and Overcoming Difficulties

9.1 introduction: quarter century of major transformations.

The case of education reform in Russia (just as in all other post-socialist countries) is very complex and difficult to analyze insofar as it combines planned educational policies with the spontaneous adaption of the system to the tectonic social and economic transformations of post-socialist societies (Silova and Palandjian 2018 ). The post-Soviet transformation of Russian education since 1991 should be considered in the context of social, political, cultural and economic change. At each stage of this transformation, the following aspects of these contextual changes should be kept in mind (Ben-Peretz 2008 ; Silova and Palandjian 2018 ):

Political – from a totalitarian one-party regime to democratic governance and rule of law; new federal-regional relationships

Social – from forced equality to growing inequality

Cultural – from government censorship and atheism to a pluralistic culture and the active role of the Church

Economic – from a planned economy to the free market

There is a general consensus that the transformation of education policy in post-Soviet Russia went through three major stages:

1991: Disappearance of Soviet ideological and centralized administrative control; borrowing curricular ideas and teaching approaches from the West; experimentation (Birzea 1994 )

2000: Nationwide construction of new institutional mechanisms in education, including per-capita financing, public engagement, quality assurance (including a national school leaving exam), modernization of school infrastructure, and greater student choice

2012: Achieving global competitiveness in education while assuring the equality of educational opportunities by raising the status of teachers (including significant salary increases), continuing to develop quality control mechanisms, and introducing new curricular standards

2016: Conservative turn. Since this time, the new leadership of the Ministry of Education has striven to return national curriculum policy to the Soviet model. Using the idea of a “common education space for all schools,” it initiated the revision of federal education standards to reduce the curricular autonomy of schools and teachers

There is a significant body of studies on the post-Soviet education transformation of 1991–2000. This period is often called the “policy of no policy” – it was a time of adaptation rather than targeted reform. Every region and almost every municipality elaborated its own education policy and strategy, often without any link to the federal government. As a rule, these policies were driven by factors external to education – primarily economic, social and technological changes. In this chapter, we shall consider the period from 2000 on.

Many researchers have studied financial and organizational reforms (The World Bank 2019 ; Cerych 1997 ). Therefore, we shall focus here on changes in teaching- and learning-related areas (curriculum, assessment, textbooks, technology, teacher training) within the education system. The specific focus of our analysis leads us to the conclusion that the reforms paid little attention to the true nature of teaching and learning and therefore did not fulfill their transformative potential.

Our analysis is based on personal experience, Footnote 1 data from various sources, an analysis of literature, and 12 interviews with former and current education policymakers in Russia.

9.2 Post-Socialist Education System as the Result of Path Dependence, Modernization and Global Integration

This chapter includes a discussion of the specific context of the transformation, which makes the Russian case very particular. One of the largest education systems in the world had to modernize itself, move away from a socialist institutional organization, and enter the global education scene. The approach of this chapter is based on the simultaneous analysis of three processes:

Transformation (abandonment or strengthening) of the post-Soviet educational legacy that derives from socialist education

Modernization (introduction of new elements and processes) of education, reflecting changes in the economic, political and social context within the country

Changes in education that reflect global processes in which Russia is participating

These processes could contradict or reinforce each other at different times. In addition, each had its own logic and interest groups.

9.2.1 Soviet Legacy

The early Soviet school was characterized by three distinct features: forced equalization and a preference for previously disadvantaged groups; communist ideological education (upbringing) in the absence of traditional religion-based values; and an innovative curriculum that aimed to connect school and “real life” (labor). The Bolsheviks initially rejected the “old school rules” inherited from Continental European traditions.

Attempts to assure a broader and more equal access to education led not only to structural changes and organizational expansion but also to very important policies on curriculum and teaching. First, the idea of cultural capital (even the Bolsheviks were not familiar with this term) served as a basis for the policy of early childhood development within the extensive public system of pre-school education. This system helped children from formerly underprivileged groups to prepare for school. Secondly, the idea of equality led to the practice of uniform requirements for student knowledge and teacher qualifications. Thirdly, the equalization policy included affirmative action and special curriculum options to support girls, children from rural families, and children from poor families (Bereday 1960 ).

These approaches evolved during the Soviet era, existing until its very end. The rigid uniformity manifested itself in the compulsory detailed curriculum that was followed by every Soviet school. Daily tasks, exams and textbooks were universally enforced in 11 time zones. Attempts to increase the variability of curricula in high school resulted in 1% of high-school students attending schools with in-depth curricula in math, science or foreign language (Bereday and Pennar 1976 ).

Soviet education was extremely politicized from the very beginning. Every teacher and parent learned Lenin’s famous maxim: “School without politics is nothing but lie and hypocrisy.” Therefore, political and ideological education was part of the Russian education system. The Marxist theory of education rejected religion as an element of human moral and social development and did not consider the family to be an important partner in children’s upbringing. The public school was considered the only actor in this process. Political indoctrination included teaching ideologically biased school subjects (history, social studies, literature, geography and science) and mandatory extracurricular activities in communist youth organizations (Long 1984 ; Judge 1975 ). The system exerted ideological control over every aspect of school life, including political rituals. It is important to note that this politicized education also attempted to inculcate morality and social skills and assist in career development. Soviet authorities established a unique system of publicly funded after-school education, including sport clubs, art and music lessons, etc. More than 70% of students participated in different activities within this system (Holmes et al. 1995 ).

During the post-Revolutionary period of the 1920s (Kerr 1997 ), the People’s Commissariat for Education developed a strategy aimed at promoting a comprehensive labor-centered educational model. This largely resonated with the imperative of creating a new socialist generation as an indispensable foundation for building a totally new society. This policy was also associated with substantive changes in educational design and the instructional framework itself. For example, students were expected to participate primarily in practice-oriented project-based learning rather than conventional “drill and repetition” activities. Accordingly, the teacher was also assigned the new role of a facilitator who tried to motivate and engage children in this kind of schooling. As a result, new institutions for experimental education began to be established in large numbers across the Soviet Union at the time. In Moscow alone, there were eight schools that entered into close cooperation with the U.S. psychologist and innovative educator John Dewey and his followers. On the whole, the pedagogical principles of comprehensive, labor-centered learning and development experienced a marked upswing in the USSR during the 1920s. As John Dewey himself noted when reflecting on early Soviet Russia, the country’s post-Revolutionary schooling came to favor pedagogical novelty and experimentation of various kinds, which would definitely not have been possible in Russia’s imperial past. It should be noted that this new pedagogical framework put special emphasis on such aspects as interacting with students’ families, promoting after-school study (after-school activities, summer camps, etc.), and introducing new models of collective work and study (Dewey 1928 ).

Despite the fact that ideological propaganda and the forced inculcation of communist values became deeply entrenched in Soviet education, it must be recognized that the creative legacy accumulated by Russian pedagogy during the 1920s – primarily the experience of project-based schooling – proved useful and beneficial. We should mention the inception of Lev Vygotsky’s cultural-historical approach in this context, as the essential groundwork and first practical applications of this framework date to the 1920s. However, as the country entered the industrial era of the 1930s, the momentum of pedagogical creativity and experimentation dwindled, and Soviet education largely returned to more rigid models. The connection with “real life” was achieved not through project methods but through a detailed curriculum with a strong emphasis on science, mathematics, and engineering and the early separation of students into academic and vocational/technical tracks. These changes were accompanied by a major expansion of the higher education system that influenced the expectations of students and families.

In the late 1950s and 1960s, after the end of Joseph Stalin’s regime, attempts were made to reform the “industrial school model” yet proved unsuccessful. A group of psychologists and philosophers proposed an “activity-based approach” grounded in Vygotsky’s ideas of the social situation of the zone of proximal development. It was directly connected with the concept of high-level generic skills (one of the manifestos of this approach was “Schools must teach children to think”) (Ilyenkov 1964 ). The Academy of Pedagogical Sciences established a number of experimental schools in different parts of the Soviet Union. Teachers got new textbooks, and numerous training and retraining courses were developed. This approach got attention worldwide (Simon and Dougherty 2014 ).

Still, the innovations in curricula and teaching that were introduced in the 1960s and 1970s came to play a significant and sustained role in the overall development of Soviet schooling. A good example is the practice that emerged among school teachers of complementing their standard daily lesson plans with tasks aimed at developing students’ critical thinking skills and personal traits. Furthermore, supervisors began to monitor how such skills were developed both in the classroom and during extracurricular activities offered at each school. Students at different levels of education were expected to display a solid knowledge of ethical principles and codes of conduct. They were encouraged to prepare personal growth plans and work persistently and independently to become honest, responsible, considerate and hardworking Soviet citizens (Dunstan and Suddaby 1992 ).

9.2.2 Early Post-Soviet Period: Innovation and Adaptation

The period between the late 1980s and the late 1990s witnessed a mass revival of interest in educational innovation in three areas: the rejection of the Soviet legacy; the modernization of curricula and the reform of the system to respond to the changing needs of Russian society; and opening education to globalization (Collier 2011 ; Bolotov and Lenskaya 1997 ). We should note that this interest was an even stronger driving force of change than government policy. The only real policy at that time was to give more freedom to different stakeholders.

During this period, there appeared a large number of experimental schools where a new generation of innovative educators adopted and built upon the ideas of developmental learning in order to nurture different student qualities and abilities similar to what we call “21st-century skills” today. Among the novel frameworks that enjoyed the greatest popularity among teaching professionals during this period were “humanistic pedagogy” and the ideas of “collective learning.” This led to the creation of a nationwide movement of innovative teachers and educators, whose “Manifesto for the Pedagogy of Cooperation” summarized their common goals and the key curricular and instructional approaches of innovative schooling. This document stressed such pivotal principles as promoting cooperation between teachers, students and parents; all-around personal and professional development; and self-governance (Eklof and Dneprov 1993 ). As the national teacher community started to participate in global educational networking, a growing number of overseas educators began to come to Russian universities, teacher associations, and other organizations to talk about international innovative experiences in learning and development. This led to the growing popularity in Russian schools of pedagogical ideas and approaches advanced by Maria Montessori, Rudolf Steiner, and Célestin Freinet, among others.

It should be noted that, during the period in question, educational innovations began to get more recognition and support from various public and state institutions in Russia. This was evidenced by multiple facts, including the increasing appointment of innovative teachers to major positions at different governmental levels, their growing interaction with professional development organizations and universities for sharing their views and disseminating novel practices in education development, and the growing focus of academia and policy agencies on exploring and discussing the ideas of innovative teachers (Eklof and Seregny 2005 ). During the same period, Russian central authorities vested regional bodies with the right to make and administer education development policies at their own discretion. As a rule, these policies varied significantly between regions, reflecting the different conceptions of and approaches to innovative education across Russia (Webber 2000 ; Johnson 1997 ).

With time, the public movement of educational innovators started to lose ground, however. This was due to several different reasons. First of all, despite the substantial experience accumulated by progressive teachers in Russia and their efforts to disseminate various novel practices, the institutional and regulatory foundations of the national education system remained basically intact and were unable to provide the necessary conditions for fostering innovative development. For example, statutory education standards retained their traditional content and structure, in which the conventional principles of drill, repetition and knowledge reproduction were emphasized (Kerr 1994 ). In addition, many of the proposed pedagogical innovations lacked the necessary financial support for being effectively implemented at a large scale. Secondly, no substantial changes had been made to the national system for teacher training and professional development. Nevertheless, despite these factors that precluded any systemic deployment of innovative practices in the educational sphere, positive changes took place during this period. They included increased levels of autonomy and flexibility in designing curricula and teaching at both regional and institutional levels (e.g., school- and regional-level components were introduced into curricula; schools were allowed to complement the mandatory core curriculum with extra disciplines to adapt the content of education to changing socioeconomic needs and stakeholder expectations; etc.) (Sutherland 1999 ; Jones 1994 ).

In the meantime, Russia sank into the prolonged and disastrous disarray of the 1990s. This included a series of painful trial-and-error economic reforms, the lack of a robust legal system, the misappropriation and redistribution of industrial assets, severe delays in salary payments, and an escalating crime rate. These events were further exacerbated by the 1998 sovereign default and its dramatic aftermath of hyperinflation and shrinking disposable incomes. These pernicious circumstances called for major remedies to rectify the deep economic downswing. This time was also characterized by drastic changes in every domain of social life, as the country transitioned to the new market-driven economy (Khrushcheva 2000 ).

As the 1990s drew to a close, the Russian education system was confronted with a series of severe problems and constraints at different levels, including curtailed public funding; deteriorating facilities and outdated equipment; a lack of qualified young teachers and the falling prestige of the teaching profession; and non-transparent and often corrupt systems for evaluating education quality. There was a pressing need for a new, systemic approach to national education (Reform of the System of Education 2002 ).

9.3 Return of the State to Policy Development and Implementation

The onset of systems transformations in the Russian education system dates back to December 2001, when the Russian government adopted the “Concept for Modernizing Russian Education through 2010.” This enactment was the first to include imperatives related to the so-called “competency-based approach” that called for the development of a holistic, up-to-date set of relevant skills and abilities in schools. However, even a cursory glance at the list of adopted measures shows that policymakers had no intention at that stage to amend the national education standards already in place. At the time, policy discussions were largely confined to such topics as shifting from a K–11 to a K–12 schooling model, simplifying curricula, expanding the list of elective courses, and increasing the number of hours of physical education. There was no explicit focus on the 21st-century skills agenda.

In the spring of 2004, only days before the incumbent Russian Minister of Education was dismissed as part of an ongoing administrative reform, the new state education standards were approved. They included provisions for “… shaping education in such a way as not only to provide students with certain bodies of specific disciplinary knowledge but also to ensure the comprehensive development of their personality traits and multifaceted cognitive and creative abilities.” In addition, references were made in this document to the objectives of inculcating up-to-date competencies and skills in children, echoing the provisions of the “Concept for Modernizing Russian Education through 2010” (Concept for Modernisation 2010 ): “General schooling must be able to inculcate a cohesive system of universal core literacies, skills and abilities, as well as to nurture in children a sound capacity to exercise adequate degrees of autonomy and self-direction, to take personal responsibility, etc., i.e., those competencies that reflect modern standards for the content and quality of education.” However, the new standards also did not try to list or describe any of the specific competencies and skills to which they referred, only setting out basic learning outcomes for every curriculum subject to be evaluated throughout the general schooling ladder in elementary, middle and high school. It should be noted that the wording of some learning outcomes already implies the pragmatically oriented, goal-centered educational focus adopted in this document. For example: “[students must be able:] to adequately comprehend live speech by adults and peers, children’s radio broadcasts, audio recordings of different types, etc.; to work with a dictionary; to produce short coherent texts on topics relevant to their age, both orally and in writing; to display the mastery of generally accepted Russian conversational patterns as relevant to different contexts of basic daily communication…” While these attempts to harmonize the regulatory framework with the imperatives of competency-based training for “real life” represented a real step forward in state education policy, the document nevertheless failed to relate any subject-specific learning and development (L&D) outcomes to the framework of universal core competencies and skills of the 21st century. Similarly, the 2004 secondary education standards still mostly focused on simply establishing “basic core curricula” or detailed lists of study topics for every subject and stage of the education ladder. Thus, if we take a look at any 2004 standard, whether in literature, history, or physics, we will only find detailed itemized lists of specific thematic areas and questions to be addressed during the course (e.g., book titles, historical events, natural phenomena). This hardly dovetails with modern effective curriculum and instructional design (Silova 2009 ).

However, in late 2004 the national government took steps to update learning and development in education policy by adopting the “Priority Development Areas for the Russian Education System.” Subsequently, a comprehensive action plan for implementing the provisions was elaborated in the spring of 2005. These measures represented a more transparent policy intention to systematically revise the education standards in place in order to enable a more up-to-date framework based on well-defined L&D objectives and outcomes. It was proposed at this stage that conventional lists of study topics by subject area should be eliminated from education standards altogether. However, such innovative shifts took place in a rather slow and uneven fashion, as the Russian government had not yet understood how to transition to 21st-century competency-based pedagogical principles (Concept for National Standards 2005 ).

In 2005, the priority national project “Education” initiated by Russian President Vladimir Putin established a system of grants to support the country’s best teachers and innovative schools. This suggested the state had decided to stake the successful implementation of further education reforms on the practical experience and vision of a national corps of progressive teachers.

On September 13, 2007, during the discussion of the priority national project “Education” at the Federation Council, the Russian President called for measures to be taken to design and deploy “… a new model of education that would effectively address the target of the sustained innovative development of the national economy and that would, in particular, be based on totally new statutory education standards as its regulatory core, creating the conditions for students to acquire adequate knowledge and the relevant skills allowing them to put this knowledge to effective practical use.” The presidential appeal prompted the policy framework to accord more attention to the conceptual domain of 21st-century skills, while also heralding yet another turnaround in the standardization of national education.

The year 2008 witnessed a series of legislative amendments and the revision of Russian national education standards. An important novelty was the inclusion in the standards of so-called “meta-discipline learning outcomes” deriving from a more or less explicit competency-centered learning and development model. Structurally, the approach of the new standards to framing learning outcomes closely resonated with the groundwork of the 21st-century skills agenda: both distinguished between the following three groups of outcomes: subject outcomes (functional literacy, knowledge and understanding), meta-discipline outcomes (competencies), and personal outcomes (values and mindsets) (Silova 2010 ).

In 2009–2010, the new Russian federal education standards (FES) were drafted and pilot-tested with the participation of multiple stakeholders at different levels, including policy officials, experts from the Russian Academy of Education, providers of upskilling/reskilling programs, and universities. In the course of FES development, project team members engaged in fieldwork across Russian regions, where they held seminars on FES documents and feedback sessions. Public reactions and proposals were then forwarded for further discussion to the FES Council at the Russian Ministry of Education and Science. However, a major shortcoming of this method was the fact that the aforementioned corps of national education progressives represented by the most resourceful teachers at innovative schools was hardly involved at all in public discussions on the proposed FES. The failure of the agencies implementing the FES project to organize the drafting and pilot-testing process in a cohesive and transparent manner made it impossible for many representatives of the innovative teaching community to contribute to the project in a meaningful way. For example, venues for FES discussions were mostly chosen by local state authorities at their sole discretion, often without due consideration for the interests and requirements of other stakeholders; little reference was made to innovative school experiences when explaining and validating the new FES; and expert councils for the project were created at the federal level only. University professors and specialists in individual disciplines had the strongest voice in these councils, while teachers and parents were not properly represented. As a result, the standards were written in a very formal and academic language that alienated teachers (Silova 2011 ).

Nevertheless, the aforementioned shortcomings and inconsistencies notwithstanding, the Russian Education and Science Ministry completed in 2010–2012 the drafting and approval of the new FES package for K–11 education with separate regulations for each stage of learning and development, including preschool and elementary, middle, and high school. All of the FES followed the educational paradigm of 21st-century skills, as they specified not only learning outcomes for individual disciplines but also included expected meta-subject competencies and personality development outcomes for students at every stage of learning and development.

It should be noted that, during the transition to the new FES framework, Russian school teachers were left to their own resources to decide on how the new imperative of inculcating 21st-century skills should be actualized in their classrooms. To enable a smoother transition to the new FES, a number of continuing education opportunities were offered to teachers across Russia, including methodological seminars, best-practice workshops, and upskilling courses. It was also decided to develop model study programs based on the new FES as practical guidelines for individual teachers and schools in elaborating their own curricula and class schedules in accordance with the FES (in 2010–2014, such model programs were developed for every stage of K–11 education).

At the same time, it was assumed that the secondary schools themselves would be able to reconfigure and harmonize their systems for monitoring and evaluating the conformity of learning outcomes to the new imperatives of competency-centered learning and development. The centralized state assessment of student performance under the new FES framework was only planned for 2020 and 2022 (given that the first-graders of 2011, which was the first year of schooling under the new FES, would take their K–9 and K–11 state exams in 2020 and 2022, respectively).

9.4 Reform and New Understanding of Learning Outcomes

As we mentioned above, the curricular standards included three groups of outcomes: subject outcomes (discipline-specific; functional literacy, knowledge and understanding), meta-subject (meta-discipline) outcomes (competencies), and personal outcomes (values and mindsets). The first two groups covered cognitive development, while the third group addressed social and emotional development.

The following examples illustrate the differences between these groups.

For example, subject outcomes in mathematics were described as follows:

Use of basic knowledge in mathematics for describing and explaining surrounding objects, processes, and phenomena and evaluating their quantitative and spatial relationships

Mastering the fundamentals of logical and algorithmic thinking for spatial imagination and mathematical recording, measurement, and calculation and executing algorithms

Ability to operate with numbers orally and in writing, ability to perform textual tasks and use algorithms, develop simple algorithms, research, recognize and draw geometrical figures, work with tables, graphs, diagrams, chains and aggregates, and present, analyze and interpret data

These descriptions show a certain degree of orientation on the application of theoretical knowledge to practical situations, even though the statements are too general and do not help teachers to plan their work. In later versions of the standards, the descriptions became more detailed and specific. Still, they continued to be oriented on subject knowledge and had little to do with 21st-century skills.

Here are some examples of metacognitive learning outcomes:

Developing the ability to select and pursue educational aims and objectives, finding the proper means for their implementation

Developing the ability to solve creative and research problems

Developing the ability to plan, control and evaluate learning activities from the standpoint of the task and the conditions of its implementation and to find the most effective means to attain the result

As these descriptions of outcomes show, many were related to 21st-century skills, even if most of them were formulated as processes rather than outcomes. Moreover, the authors of the standards failed to explain how metacognitive outcomes were to be addressed in school subjects. Some teachers believed these outcomes should not be targeted in their work because they were not formally assessed.

Below are some descriptions of personal learning outcomes:

Developing Russian civic identity, taking pride in one’s motherland, the Russian people and Russian history, recognizing one’s ethnic and national identity; developing the values of multinational Russian society; developing humanistic democratic values

Developing a respect for the opinions of others and the history and culture of other ethnic groups

Taking personal responsibility for one’s actions, based on values, norms, and social justice and freedom

Developing cooperation skills with adults and peers in different social situations and the ability to avoid conflicts and resolve disputes

This language was not clear for teachers. Moreover, it was not entirely clear how these results could be attained in school. At the same time, the standards stated that personal outcomes were not assessed.

The authors of the standards tried to present the aims and objectives of the standards in language which would be comprehensible to ordinary citizens. To this end, they introduced a special section called “primary school student profile.” It indicated that primary school graduates

Love their people, region and motherland

Respect and accept values of family and society

Actively learn about the environment

Learn and organize their own activities

Act independently and take responsibility for their actions

Have a friendly attitude, listen to and understand their interlocutors, and are able to present their views and opinions

Follow the rules of a safe and healthy way of life

As the above statements show, the authors of the standards tried to assuage society by emphasizing the absence of risks in the reforms. They focused on the most popular and traditional mindsets: patriotism, goodwill, a healthy life style, and family values. As a result, they presented the abilities to think critically, cooperate, solve problems, and communicate effectively in a less clear way. They tried to balance the new learning outcomes with a “know everything” approach (Muckle 2003 ).

The resulting curriculum included some elements contributing to the development of 21st-century skills. However, the content and procedures of the assessment system changed very little, which became the main hindrance to the development of these skills.

Some aspects of the reforms supported the development of 21st-century skills, while others were neutral. We will briefly describe these two groups of elements.

The first group of elements contributing to the development of 21st-century skills included

Per capita financing and school autonomy. It was expected that the uniform distribution of financial resources among schools in proportion to the number of students would stimulate the renewal of the content of education and that financial freedom would give teachers greater autonomy in developing their own curricular programs. In turn, teachers would be more responsible and independent in selecting the methods of attaining new learning outcomes, including meta-discipline and personal outcomes. Many schools reflected these outcomes in their curriculum. The budgets of schools began to depend on the number of students. As a result, some schools tried to develop new courses to attract more students.

Teacher development programs were selected on the basis of teacher needs. Previously, only special teacher in-service training institutions had provided teacher training programs, yet their programs were of low quality. Now, these institutions had to compete with universities and other non-commercial organizations, as individual teachers independently sought professional development opportunities to get acquainted with the new standards. The number of in-service training courses aimed at the development of 21st-century skills has grown since 2012.

The appearance of internet in schools allowed teachers to look for new materials, meet new colleagues, and participate in different professional networks online. New communities of practitioners stimulated teachers to search for new teaching solutions. Many teaching materials supporting the development of 21st-century skills were adapted from foreign resources and non-commercial organizations.

The new curriculum allowed schools to offer more elective courses to students. This innovation played a dual role in the development of 21st-century skills. Some schools gave students more opportunities to select their study tracks, teaching them to make conscious choices, solve problems, and cooperate. Schools transformed traditional courses and subjects and gave students a new choice of courses. These changes were connected with the 21st-century skills approach.

Aspects of the reform that hindered the introduction of the new standards included:

Expanding the curriculum by introducing new subjects, such as “fundamentals of religious cultures” and astronomy. While a lot of resources were invested to introduce these subjects, their content was based primarily on memorization. The same was true of the renewed concepts of teaching history and literature. They were also oriented at the memorization of information and historical facts and reading books from the recommended list.

Russia was still developing its quality control system. Despite the growing number of monitoring and review measures, the instruments remained focused on knowledge control, hindering the orientation of teachers at the development of 21st-century skills.

9.5 Reform Implementation

The implementation stages reflect the stages of the reform.

2001–2004. This stage was more about reform design and discussion rather than reform implementation. Implementation was limited to experimental schools, pilot municipalities and pilot regions. Many schools experimented with their new curricular freedom. They introduced new courses and project-based lessons. Many local publishers also took advantage of the relatively flexible requirements for textbooks and experimented with new contents and formats of learning materials. However, these innovative practices were not supported by analysis and evaluation. Good practices could not be disseminated without such evaluation and horizontal cooperation between teachers and schools. The regional and federal governments did nothing to support and diffuse the best practices.

Some innovations such as the national school leaving/university entrance exam (Unified State Exam) and per capita financing were pilot-tested in several regions prior to their mass introduction nationwide.

2004–2005. During these 2 years, the Russian government established a new system to implement its education policy agenda, including a totally new Russian Ministry of Education and Science along with a Federal Agency for Education, a Federal Agency for Science, and a Federal Service for Education Quality Monitoring. The underlying idea was that a closer integration of the domains of education and research would enable more meaningful, high-payoff reforms that would be better tailored to address all the top-priority development areas. However, the changes at the federal level did not transform the very nature of top-down reform. Nor did they have any significant impact at the regional, municipal and school levels. They increased top-down control in reform implementation without promoting the energy and initiative of lower levels.

2005–2011 . The project approach of reform implementation was pilot-tested during this period. In the fall of 2005, the Russian President launched the strategic national project “Education,” accompanied by a series of similar nationwide initiatives in healthcare, construction and agriculture. The “Education” project framework envisaged the following the key measures:

Paying personal awards of RUB 100,000 annually to the 10,000 best Russian teachers

Allocating grants of RUB 1 million annually to 1000 innovative schools

Regular top-up payments to homeroom teachers (reflecting their extra duties of class supervision, the organization of learning and development extracurricular activities, etc.)

One-off modernization projects addressing specific aspects of education in individual regions (any financial surpluses achieved through such structural reforms were typically used to fund teacher pay raises in the regions)

This period showed that the centralized system of policy implementation could work only with relatively simple project objectives. This partially explains why the government could not really implement the curriculum reform.

2011–2016 . The adoption of the new federal law “On Education” was the central element of reform implementation during this period. The new law provided a favorable regulatory framework for the mass-implementation of new education policies piloted in previous years. It also included the universal implementation of new progressive federal education standards. The mass-deployment of FES also envisaged that the regions themselves would play a major role in facilitating effective teacher transition to the new standards; however, much of this work was impeded by its uneven and intermittent implementation.

2016–2018. During this period, the Russian Ministry of Education and Science underwent a series of administrative changes which, in turn, led to a readjustment of the overall action plan and key priorities in implementing the agenda of 21st-century skills and competencies in the Russian education sphere. Specifically, the newly appointed ministerial executives cast doubt on whether previous policy steps in upgrading the national education standards had in fact been reasonable and justified. Acting under the premise that “the formation of adequate bodies of knowledge should always precede – and serve as a basis for – the process of inculcating individual skills and competencies in students,” the newly formed Ministry initiated yet another massive revision of federal education standards, spawning a vigorous debate in society One of the reasons for such doubt was disappointment of significant part of society with the fact that students don’t remember key facts of Russian history and cultural heritage. In the spring of 2018, the Russian government reorganized the Ministry of Education and Science, creating two separate bodies in charge of secondary education (the Russian Ministry of Education) and tertiary education and science (the Russian Ministry of Science and Higher Education), respectively. In conclusion, we should stress that the dilemma of whether Russian education should more actively effectuate a transition to a competency-centered framework or, on the contrary, prioritize traditional disciplinary knowledge in national schooling has been receiving increasing attention in Russia recently.

9.6 Reform Politics and Main Results

On the whole, one can see a consistent logic in how the Russian government proceeded to reform the sphere of national secondary general education. A holistic conception of a general action plan was first elaborated and then followed by all-around public discussions and the gradual implementation of its individual elements. Looking back at how education reform was implemented in Russia, one can identify the following key factors and considerations facilitating these innovative processes:

It was assumed from the very outset that the reform process would be primarily driven by the country’s educational progressives. A lot of resources were invested in refining and pilot-testing the proposed learning and development innovations. The strategic national project “Education” provided a grant support framework for the best teachers, innovative schools and regional education reform initiatives, promoting the accumulation of a sound social asset of educational leaders and justifying the imperative to shift to competency-centered pedagogy. Moreover, a number of models of innovative schooling and individual innovations in educational design and instruction have become widely acknowledged and received increasing popular support.

Russia became actively involved in a range of global education competitions and evaluation initiatives, including WorldSkills, PISA, TIMSS, PIRLS, and ICILS. Moreover, a number of national and subnational programs in education monitoring and testing were introduced in elementary and secondary schools. Evidence drawn from such assessments and benchmarking frameworks served to substantiate the goals and socioeconomic rationale of upgrading the standards of Russian schooling, as researchers finally got access to reliable cross-national data that could serve as a basis for substantiated judgments on the validity and appropriateness of specific learning and development approaches, models, and policy action.

An example of the positive impact of education policy is the growing PISA math scores of Russian schoolchildren. In 2000, Russia’s score was much lower than the OECD average. In 2003, Russia’s results declined. In 2006, the mean OECD score fell, while Russia improved its performance, narrowing the gap. In the next 2012 wave, Russia’s performance grew substantially. Finally, in 2015 Russia’s score surpassed the OECD average for the first time. We should note that, although the mean score of OECD countries fell in 2015 in comparison with the 2012 wave, the 2015 results of Russian schoolchildren were comparable with OECD mean scores in 2006, 2009 and 2012.

Beginning in the late 2000s, improvements started to be felt in the regulatory domain of Russian education as greater levels of transparency, trust, and accountability were achieved with the onset of massive public discussions of different proposed policies (in particular, through the institution of public councils, crowdsourcing techniques, etc.). Authorities organizing such public events were appointed on a regional basis across Russia, and the main results of public discussions began to be disclosed and disseminated through seminars, web sessions, and stakeholder conferences. For example, over 100,000 people took part in discussions about the structure and content of model subject programs under the new competency-centered FES. Ongoing close public focus on the proposed regulatory initiatives in education has facilitated robust critique and multifaceted stakeholder feedback, leading policymakers to revise and expand their initial policy recommendations.

Alongside these positive factors, the reform process has had a number of major shortcomings and limitations:

A major drawback of the reform of Russian schooling was the fact that most of the work on drafting the new FES and related methodological guidelines was performed by institutes of the Russian Academy of Education – a highly reputable academic organization that, nonetheless, failed to engage a sufficient number of education practitioners in the process. As a result, the language of the FES documents was overloaded with technical terminology barely comprehensible to many teachers. Furthermore, the abstruse and intimidating academic language of the new FES framework prevented non-specialists from making a more meaningful contribution to discussions and proposed amendments to the FES. At the same time, few business stakeholders participated in the reform process, making it impossible to bridge the widening gap between the quality of schooling and labor expectations.

The global financial crisis of 2008 heavily affected the Russian economic landscape, leading the government to cut spending on modernizing education for several years. A number of major innovative initiatives had to be downscaled or scrapped altogether as a result. Consequently, the funding of education reforms in Russia became misbalanced. For example, while significant funding was allocated to less important areas (e.g., the new elementary school curricular program “Fundamentals of Religious Culture and Secular Ethics” was launched in 2010–2011, incurring much greater costs than the new FES), such crucial initiatives as purchasing modern equipment, training teachers, and holding stakeholder conferences and seminars remained vastly underfinanced.

While transitioning to the learning and development framework of 21st-century skills, Russian education authorities pursued reform ambitions in a wide range of other areas, including devising new models of cooperation between businesses and professional education organizations, boosting university research, and developing new approaches to the guardianship of orphaned children and children’s summer recreation and healthcare. Confronted with these multiple priorities, the Russian Ministry of Education and Science simply lacked the resources required to develop the reform agenda in secondary schooling more thoroughly.

The number of public organizations and other stakeholders favoring a return to the conventional knowledge-centered paradigm patterned after the fundamental model of Soviet schooling has increased considerably in recent years, impeding a more streamlined transition to 21st-century pedagogy.

The ongoing reforms have not been accompanied by any rigorous evaluation of their impact. However, local and international studies provide evidence that the overall quality of school education has improved, inequality has been reduced, and general public satisfaction with education has increased. Further studies are needed to evaluate the impact of these changes more deeply.

One of the authors (Isak Froumin) was a senior member of the World Bank team in Moscow that provided support for Russian education reform (from 1999 to 2015); the other (Igor Remorenko) was a senior official at the Russian Ministry of Education (from 2004 to 2013), holding, in particular, the position of Deputy Minister (from 2011).

Ben-Peretz, M. (2008). The life cycle of reform in education: From the circumstances of birth to stages of decline . London: Institute of Education-University of London.

Google Scholar

Bereday, G. (1960). The changing soviet school . Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Bereday, G., & Pennar, J. (1976). The politics of soviet education . Westport: Greenwood Press.

Birzea, C. (1994). Educational policies of the countries in transition . Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Bolotov, V., & Lenskaya, E. (1997). The reform of education in new Russia: A background report for the OECD review of Russian education. OECD Thematic Review of Tertiary Education . Moscow: OECD.

Cerych, L. (1997). Educational reforms in central and Eastern Europe: Processes and outcomes. European Journal of Education, 32 (1), 75–97.

Collier, S. (2011). Post-soviet social: Neoliberalism, social modernity, biopolitics . Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Concept for Modernisation. (2010). Concept for Modernisation of Russian Education. Policy Statement by the Government of the Russian Federation. [Electronic] Available from www.mon.gov.ru . Accessed 10 June 2013, p 256.

Concept for National Standards. (2005). Concept of Federal State Educational Standards for Secondary Education. Policy Document by the Government of the Russian Federation. [Electronic] Available from http://standart.edu.ru/catalog.aspx?CatalogId=261 . Accessed 20 Sept 2008.

Dewey, J. (1928). Impressions from revolutionary world . New York: New Republic.

Dunstan, J. (1994). Clever children and curriculum reform: The progress of differentiation in Soviet and Russian state schooling. In A. Jones (Ed.), Education and Society in the new Russia (pp. 75–103). M.E. Sharpe: Armonk.

Dunstan, J., & Suddaby, A. (1992). The progressive tradition in soviet schooling to 1988. In J. Dunstan (Ed.), Soviet education under perestroika (pp. 1–13). London: Routledge.

Eklof, B., & Dneprov, E. (1993). Democracy in the Russian school: The reform movement in education since 1984 . Boulder: Westview Press.

Eklof, B., & Seregny, S. (2005). Teachers in Russia: State, community and profession. In B. Eklof, L. Holmes, & V. Kaplan (Eds.), Educational reform in Post-Soviet Russia (pp. 197–220). London: Cass.

Holmes, B., Read, G., & Voskresenskaya, N. (1995). Russian education: Tradition and transition . New York: Garland Publications.

Ilyenkov, E. V. (1964). On the aesthetic nature of phantasy. Issues of Aesthetics, 6 , 25–42. Moscow: Panorama annual.

Johnson, M. (1997). Visionary hopes and technocratic fallacies in Russian education. Comparative Education Review, 41 (2), 219–225.

Jones, A. (Ed.). (1994). Education and Society in the new Russia . Armonk: M.E. Sharpe.

Judge, J. (1975). Education in the USSR: Russian or Soviet? Comparative Education, 11 (2), 127–136.

Article Google Scholar

Kerr, S. (1994). Diversification in Russian education. In A. Jones (Ed.), Education and Society in the new Russia (pp. 47–75). Armonk: M.E. Sharpe.

Kerr, S. (1997). Why Vygotsky? The role of theoretical psychology in Russian education reform . [Electronic] Available from http://webpages.charter.net/schmolze1/vygotsky/kerr.htm Accessed 10 June 2013.

Khrushcheva, N. (2000). Cultural contradictions of post-communism: Why liberal reforms did not succeed in Russia . New York: Council on Foreign Relations.

Long, D. (1984). Soviet education and the development of communist ethics. Phi Delta Kappan, 65 (7), 469–472.

Muckle, J. (2003). Russian concept of patriotism and their reflection in the education system today. Tertium comparationis, 9 (1), 7–14.

Puzankov, D. Ensuring the Quality of Higher Education: Russia’s Experience in the International Context. Russian Education & Society , 45 (2), 69–88.

Reform of the System of Education. (2002). What we are losing (2002). Transcript of a round table. Russian Education & Society, 44 (5), 5–31.

Silova, I. (2009). Varieties of educational transformation: The post-socialist states of central/Southeastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. In R. Cowen & R. Kazamias (Eds.), International handbook of comparative education (Vol. 22, pp. 295–331). Dordrecht: Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

Silova, I. (2010). Rediscovering post-socialism in comparative education. In I. Silova (Ed.), Post-socialism is not dead: (Re)-reading the global in comparative education (pp. 1–24). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing.

Silova, I. (Ed.). (2011). Post-socialism is not dead: (Re)-reading the global in comparative education . Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing.

Silova, I., & Palandjian, G. (2018). Soviet empire, childhood, and education. Revista Española de Educación Comparada, 31 , 147–171. https://doi.org/10.5944/reec.31.2018.21592 .

Simon, M., & Dougherty, B. (2014). Elkonin and Davydov curriculum in mathematics education. In S. Lerman (Ed.), Encyclopedia of mathematics education . Dordrecht: Springer.

Sutherland, J. (1999). Schooling in the new Russia: Innovation and change, 1984–95 . New York: St. Martin’s Press.

The World Bank. (2019). Annual report. Strengthening the organization [Electronic]. Available from https://www.worldbank.org/en/about/annual-report/strengthening-the-organization . Accessed 10 Aug 2019.

Webber, S. (2000). School, reform and Society in the new Russia . New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

National Research University “Higher School of Economics”, Moscow, Russia

Isak Froumin

Moscow City University, Moscow, Russia

Igor Remorenko

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Isak Froumin .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Graduate School of Education, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA

Fernando M. Reimers

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Froumin, I., Remorenko, I. (2020). From the “Best-in-the World” Soviet School to a Modern Globally Competitive School System. In: Reimers, F.M. (eds) Audacious Education Purposes. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41882-3_9

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-41882-3_9

Published : 24 April 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-41881-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-41882-3

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Slovenščina

- Science & Tech

- Russian Kitchen

How Soviet children were raised and educated

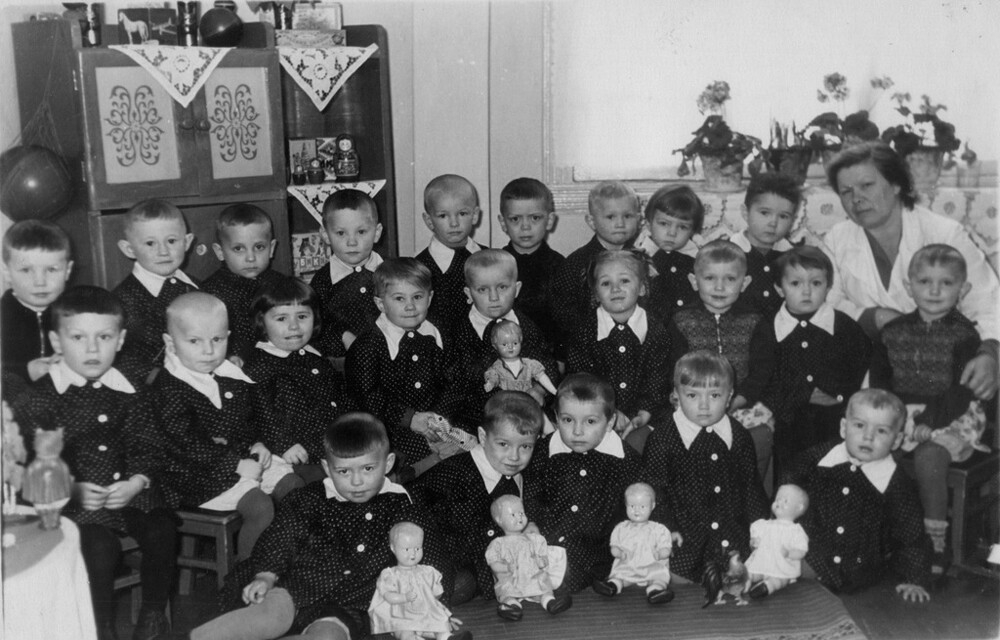

While in the Imperial era the upbringing and education of children were predominantly left to the family, that all changed in the Soviet period. The Communist authorities took charge of these matters. From the point of view of the new regime, it was particularly pertinent in an atmosphere of deep division in society.

People with revolutionary and counter-revolutionary views could be found in the same family. It was considered important to inculcate the ‘correct’ world view in children, independently of the world view of their parents.

Also, the level of education of the vast majority of the country's population was low, so it was important to take children out of their habitual environment and provide a means of social mobility for them. After all, children were the future builders of Communism.

Schools in the Imperial era

Students of a rural school, 1900s

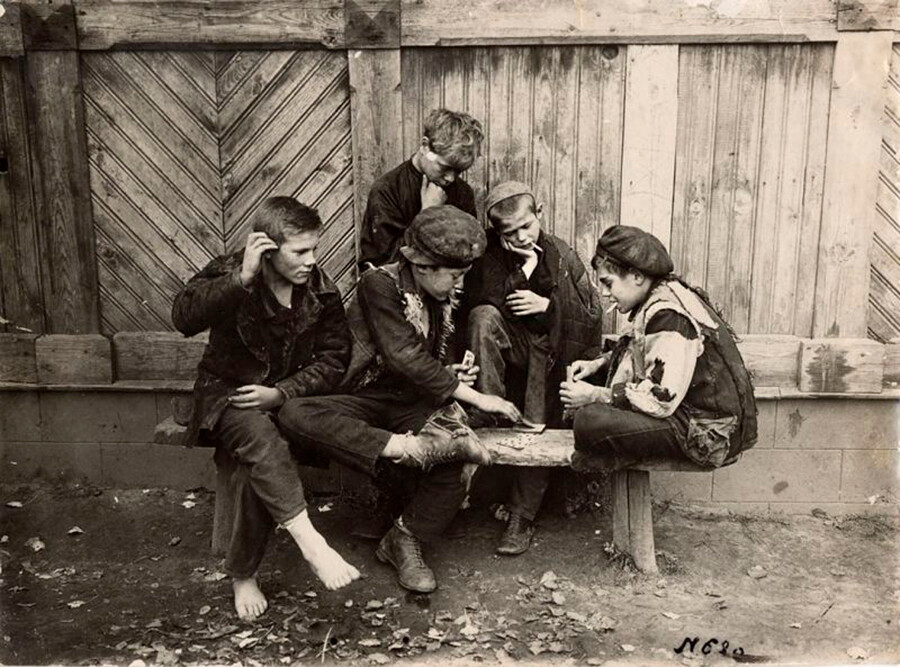

Before the 1917 Revolution, bringing up children was primarily the responsibility of the family. Parents had to decide whether to give their child a home education or send them to school. In the countryside, where families had many children, the older ones often parented their younger siblings and looked after them. Moreover, from an early age everyone was working in the fields and caring for livestock.

Poor parents could "hire out" their children - for example, as apprentices to an artisan. Essentially, this meant servitude. Numerous such examples are described in Russian literature ('In the World' by Maxim Gorky or 'Vanka' by Anton Chekhov).

A school in Samara, 1900s

There was no compulsory school education in the Russian Empire, although discussion of the need to introduce it had been widespread ever since the 1880s.

There were many schools, and new ones appeared all the time, but the responsibility for organizing the educational process (and most of the costs) rested with individual regions - the districts and provinces. Each approached the matter in their own way and there was no single system of inspection. There was no uniform school curriculum either and each teacher, depending on their experience and qualifications, decided for themselves what to teach and how to teach it.

From cradle to high school - a Soviet state education