- Current Issue

- Back Issues

- Article Topics

- ASN Events Calendar

- 2023 Leadership Awards Reception

- Editorial Calendar

- Submit an Article

- Sign Up For E-Newsletter

Presentation of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Females: Diagnostic Complexities and Implications for Clinicians

- By: Jessica Scher Lisa, PsyD Harry Voulgarakis, PhD, BCBA St. Joseph’s College

- April 1st, 2020

- assessment , behaviors , diagnosis , females , research , Spring 2020 Issue

- 9694 0

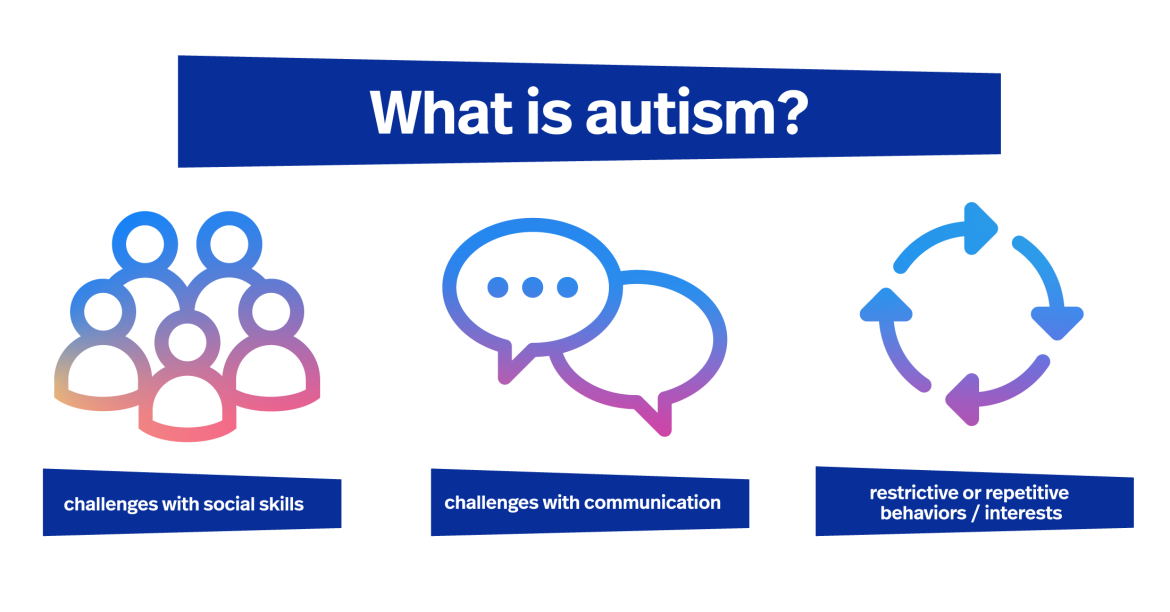

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by pervasive deficits in social communication and patterns of restricted, repetitive, stereotyped behaviors and interests (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Beyond the […]

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by pervasive deficits in social communication and patterns of restricted, repetitive, stereotyped behaviors and interests (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Beyond the main diagnostic criteria, however, there is considerable heterogeneity in the symptom presentations that is demonstrated by people with ASD, including severity, language, cognitive skills, and related deficits (Evans et al, 2018). Regarding sex differences, it has been well established that ASD is diagnosed more often in males than in females, with recent estimates suggesting a 3:3:1 ratio (Hull & Mandy, 2017). Despite the fact that this is well known, there is considerable uncertainty about the nature of this sex discrepancy and how it relates to the ASD diagnostic assessment practice (Evans et al, 2018). Additionally, it has been widely accepted that males and females with ASD present differently, which has implications for the sex discrepancy in diagnostic practices, thus females are generally under-identified (Evans et al, 2018).

The fact that females with ASD are under-identified and often overlooked can be due to a number of factors. First, they often don’t fit the “classic” presentation that is most often associated with the ASD diagnosis; specifically, there is a distinct ASD female phenotype that looks dissimilar to the typical ASD male presentation. Females with ASD tend to present with less restricted interests and repetitive behaviors (RRBs) (Supekar and Menon, 2015), thus standing out less both in society, as well as on screening and diagnostic measures. Fewer RRBs makes ASD appear in a different way, often more subtle, than what is considered to be the norm. It is also important to note that evidence suggests that even when females with ASD are identified, they receive their diagnosis (and related support) later than equivalent males with ASD (Giarelli et al, 2010). The implications for under- or late-identification are enormous and deserve empirical attention in an effort to improve diagnostic methods for ASD in females.

Harry Voulgarakis, PhD, BCBA

Jessica Scher Lisa, PsyD

While no consistent, reliable differences have been found between sex and core ASD symptoms (e.g. Bolte et al, 2011; Holzmann et al, 2007; Mandy et al, 2012), it has been well documented that compared to males, females with ASD that are undiagnosed or are diagnosed at a later age generally present with less severe ASD symptoms and more intact language and cognitive skills (Begeer et al, 2013; Giarelli et al, 2010; Rutherford et al, 2016). Research has also noted that females with ASD may be better able to compensate for symptoms despite having core deficits associated with ASD (Livingston & Happe, 2017; Hull et al, 2017). There has been some suggestion that females must exhibit more severe symptoms, impairment, or co-occurring problems in order to receive diagnoses of ASD (Evans et al, 2018). This finding is due to an analysis of previous research that demonstrates the following: females with ASD perform better on measures of nonverbal communication (which may mask other symptoms), females with ASD face more social, friendship, and language demands than males with ASD, and that females with ASD can exhibit patters of restricted interests and repetitive behaviors, as well as social and communicative problems that are deemed more socially acceptable as compared to the patterns seen in males with ASD (Lai et al, 2015; Rynkiewicz et al, 2016; Dean et al, 2014). This theory also accounts for the findings that females with ASD in general present with more severe behavioral, emotional, and cognitive problems compared to males (Frazier, et al, 2014; Holtmann et al, 2007; Horiuchi et al, 2014; Stacy et al, 2014). Further, Hiller and colleagues (2014) found that females were more likely to show an ability to integrate non-verbal and verbal behaviors, and initiate friendships, and exhibited less restricted interests. Teachers reported fewer concerns for females with ASD than for males, including concerns about behaviors and social skills. These data support the idea that that females with ASD may “look” different from the considerable “classic” presentation of ASD and may also present as less impaired in an academic setting.

The vast differences associated with gender presentation in ASD require that clinicians involved in diagnostic work become more cognizant of these broader phenotypes and adjust their assessment practices accordingly to better detect females presenting with atypical symptoms that still fall on the autism spectrum. Notably, many common diagnostic tools lack sensitivity to such a presentation. To that end, it is important to recognize that generally speaking, the evidence base, and hence the diagnostic criteria for ASD in itself comes from research among male-predominant samples (e.g. Edwards et al, 2012; Watkins et al, 2014). Therefore, while the efforts to study this area further are prominent, it is important to be mindful of the fact that existing assessment tools and diagnostic criteria likely contain sex/gender bias (Evans et al, 2018). Without addressing the neurological and diagnostic challenges pertaining to these sex/gender issues, any research in this area will be influenced by the underlying problem of not knowing how ASD should be defined and diagnosed in males as compared to females (Lai et al, 2015).

Currently, the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition (ADOS-2) is arguably the most commonly relied upon diagnostic instrument for ASD. The ADOS-2 is a semi-structured observational assessment designed to evaluate aspects of communication, social interaction, and stereotyped behaviors and restricted interests (Lord et al, 2000; 2012). In contrast to what has been documented with regard to the strong differences in the prevalence of ASD, differences between the sexes in the phenotypic presentation of ASD have been found to be much smaller in size, with inconsistencies in the findings with regard to severity level of the core symptoms, as well as age and general level of functioning. For example, some studies have found no significant differences between sexes with regard to the behavioral presentation of ASD on the ADOS (e.g. Lord et al., 2000; Lord et al., 2012, Ratto et al, 2017), while others have reported some differences (e.g. Lai et al., 2015).

In order to examine these inconclusive findings further, Tillman et al (2018) looked at data containing 2684 individuals with ASD from over 100 different sites across 37 countries. Children and adults were administered one of four ADOS modules (modules are determined by expressive language level). The Autism Diagnostic Interview, Revised (ADI-R) was also administered as well as a general intellectual ability instrument, such as the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, or a different measure depending on age and verbal capabilities. Effects of sex were determined after excluding non-verbal IQ as a predictor. No main effect of sex was found for ADOS symptom severity, or on the specific ADOS subscales. Females showed lower scores on the RRB scale with increasing age. This result is similar to previous meta-analytic research on small-scale studies as well as large-scale studies (Van Wijngaarden-Cremers et al, 2014; Mandy et al, 2012, Supekar & Menon, 2015; Wilson et al, 2016; Charman et al., 2017). The researchers concluded that this adds to the current body of literature that supports the notion that females with ASD show lower levels of RRBs than males, but exhibit a more similar autistic phenotype to boys in relation to social communication deficits across ages (Tillman et al, 2018). Thus, it is possible to surmise that females with ASD are being under-identified as a result of exhibiting fewer RRBs. Notably, research has found that clinicians are hesitant to diagnose ASD without the presence of RRB (Mandy et al, 2012), as the diagnosis of ASD in the DSM-5 requires at least two types of RRBs. Lai et al. (2015) made the case that females with ASD may simply be exhibiting different RRBs rather than fewer, and it is possible that these less common forms of RRBs are being missed during diagnostic assessments.

Understanding the phenotypic differences in the presentation of autism is critical for diagnosticians for several reasons. It is crucial to understand that aspects of the diagnostic criteria for ASD may present on other ways in females though not be elevated on standard measure scales. As a result, those who do not receive an appropriate diagnosis will subsequently not receive an appropriate intervention. Beyond the obvious concern associated with females on the autism spectrum not receiving intervention associated with their autism symptomatology, there are a range of other mental health concerns that may dually go unaddressed. Higher functioning adolescents with ASD, which is often the presentation consistent with females that get “missed” in the diagnostic process, are at greater risk for developing depression (Greenlee et al, 2016) and anxiety (Steensel, Bogels, & Dirksen, 2012). Adults with high-functioning ASD are also at increased risk for suicidality (Hedley et al, 2017). More recent, emerging research suggests that while those with ASD may be able to mask their symptoms the majority of the day and thus not reach the diagnostic threshold in scandalized measures, doing so causes them significant distress and puts them at increased risks for such co-occurring mental health concerns.

The under-diagnosis of ASD in females with ASD lends itself to a population of women who end up wondering “what is wrong” with them. Females who do not have the opportunity to understand themselves in the context of neurodiversity tend to waste time and efforts on imitating and trying to fit-in (Bargiela et al, 2016). They are at far greater risk of bullying, as well as being taken advantage of socially, with subtle difficulties in perceiving and responding appropriately to social cues rendering them inept in certain situations that require a degree of social assimilation. These females have missed out on the benefits of early intervention, most often in the social realm, and can be plagued with identity issues later in life as they try to play catch-up in light of a new diagnosis. The timely identification of ASD can mitigate some of these risks and problems by improving the quality of life, increasing access to services, reducing self-criticism, and helping to foster a positive sense of identity. As such, diagnostic experts have a responsibility to continue to stay abreast of research developing in this area and adjusting their assessment practices accordingly.

Drs. Scher Lisa and Voulgarakis are Assistant Professors in the Department of Child Study at Saint Joseph’s College, New York. They are both also clinicians in private practice. You can find more information about their respective practices at www.drjessicascherlisa.com and www.drharryv.com .

Bölte, S., Duketis, E., Poustka, F., & Holtmann, M. (2011). Sex differences in cognitive domains and their clinical correlates in higher-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 15(4), 497–511. doi: 10.1177/1362361310391116

Charman, T., Loth, E., Tillman, J., Crawley, D., Wooldridge, C., Goyard, D. et al (2017). The EU-AIMS Longitudinal European Autism Project (LEAP): Clinical characterization. Molecular Autism, 8(1), 27.

Evans, S. C., Boan, A. D., Bradley, C., & Carpenter, L. A. (2018). Sex/Gender Differences in Screening for Autism Spectrum Disorder: Implications for Evidence-Based Assessment. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 48(6), 840–854. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2018.1437734

Giarelli, E., Wiggins, L.D., Rice, C. E., Levy, S. E., Kirby, R. S., Pinto-Martin, J., et al. (2010). Sex differences in the evaluation and diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders among children. Disability and Health Journal , 3 (2), 107-116. doi:10.1016/jdhjo.2009.07.001.

Hiller, R. M., Young, R. L., & Weber, N. (2014). Sex Differences in Autism Spectrum Disorder based on DSM-5 Criteria: Evidence from Clinician and Teacher Reporting. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(8), 1381–1393. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9881-x

Holtmann, M., Bolte, S., & Poustka, F. (2007). Autism spectrum disorders: Sex differences in autistic behavior domains and coexisting psychopathology. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 49, 361-366. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.2007.49.issue-5

Horiuchi, F., Oka, Y., Uno, H., Kawabe, K., Okada, F., Saito, I., Ueno, S. I. (2014). Age-and sex-related emotional and behavioral problems in children with autism spectrum disorders: Comparison with control children. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 68, 542-550. doi:10.1111/psc.12164

Hull, L., Petrides, K.V., Allison, C., Smith, P., Baron-Cohen, S., Lai, M.C., & Mandy, W. (2017). “Putting on my best normal”: Social camouflaging in adults with autism spectrum conditions. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47, 2519-2534. doi:10.1007/s10803-017-3166-5

Lai, M.C., Lombardo, M., Auyeung, B., Chakrabarti, B., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2015). Sex/gender differences and autism: Setting the scene for future research. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 54, 11-24.

Livingston, L.A., & Happe, F. (2017). Conceptualizing compensation in neurodevelopmental disorders: Reflections from autism spectrum disorder. Neuroscience & Behavioral Reviews, 80, 729-742. doi: 10.1016/j. neubiorev.2017.06.005

Lord, C., Risi, S., Lambrecht, L., Cook, E.H., Leventhal, B.L., DiLavore, P.C. et al (2000). The autism diagnostic observation schedule – generic: A standard measure of social communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30(3), 205-223.

Lord, C., Rutter, M., DiLavore, P.C., Risi, S., Gotham, K., & Bishop, S. (2012). Autism diagnostic observation schedule, Second edition (ADOS-2) Manual (Part I): Modules 1-4. Torrance: CA: western Psychological Services.

Mandy, W. P., Chilvers, R., Chowdhury, U., Salter, G., Seigal, A., & Skuse, D. (2012). Sex differences in autism spectrum disorder: Evidence from a large sample of children and adolescents. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42, 1304-1313. doi: 1007/s10803-011-1356-0

Ratto, A.B., Kenworthy, L. Yerys, B.E., Bascom, J., Wieckowski, A.T., White, S., et al (2017). What about the girls? Sex-based differences in autistic traits and adaptive skills. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48, 1698-1711.

Rutherford, M., McKenzie, K., Johnson, T., Catchpole, C., O’Hare, A., McClure, I., Murray, A. (2016). Gender ratio in a clinical population sample, age of diagnosis and duration of assessment in children and adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 20, 628-634. doi10.1177/1362361315617879

Supekar, K., Menon, V. (2015). Sex differences in structural organization of motor systems and their dissociable links with repetitive/restricted behaviors in children with autism. Super and Menon Molecular Autism, 6, 50 doi: 10.1186/s13229-015-0042-z.

Tillman, J., Ashwood, K., Absoud, M., olte, S., Bonnet-Brilhalut, F., Buitelaar, J.K. et al (2018). Evaluation sex and age differences in ADI-R and ADOS scores in a large European Multi-site sample of individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(7), 2490-2505.

Van Wijngaarden-Cremers, P.J., van Eeten, E., Groen, W.B., Van Deurzen, P.A., Oosterling, I.J., & Van der Gaag, R.J. (2014). Gender and age differences in the core triad of impariments in autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(3), 627-635.

Wilson, C.E., Murphy, C.M., McAlonan, G., Robertson, D.M., Spain, D., Haywayrd, H. et al (2016) Does sex influence the diagnostic evaluation of autism spectrum disorder in adults? autism, 20(7), 808-819.

Related Articles

Genetics, diagnosis, and the male-female gender gap in autism.

I hesitated to write this article. What business does a psychologist like me have writing about genetics and the gender gap in autism? I am not a geneticist. At most, […]

Your Child Has Just Been Diagnosed with Autism – Now What?

Every family has their own personal journey towards an autism diagnosis for their child. Whether it brings the confirmation of what may have been suspected or the news of something […]

Beyond the Autism Diagnosis: Understanding the Multifaceted Needs of Parents

As the number of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) increases, so does the number of parents trying to navigate the complexities that accompany an autism diagnosis. Raising an […]

Bridging the Gap: Empowering Families Awaiting an Autism Diagnosis

The prevalence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) continues to rise. According to the CDC, 1 in 36 children are diagnosed with autism by the age 81 and as a result, […]

A Mother’s Journey Advocating for Her Child’s Autism Diagnosis and What Fellow Educators Can Learn

As a registered occupational therapist (OTR) and Director of Portfolio Management and Delivery at Pearson Clinical Assessment, I have extensive experience working with students who have been diagnosed with a […]

Have a Question?

Have a comment.

You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Individuals, Families, and Service Providers

View our extensive library of over 1,500 articles for vital autism education, information, support, advocacy, and quality resources

Reach an Engaged Autism Readership Over the past year, the ASN website has had 550,000 pageviews and 400,000 unique readers. ASN has over 55,000 social media followers

View the Current Issue

ASN Winter 2024 Issue "Understanding and Accommodating Varying Sensory Profiles"

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Autism spectrum disorder

Autism spectrum disorder is a condition related to brain development that impacts how a person perceives and socializes with others, causing problems in social interaction and communication. The disorder also includes limited and repetitive patterns of behavior. The term "spectrum" in autism spectrum disorder refers to the wide range of symptoms and severity.

Autism spectrum disorder includes conditions that were previously considered separate — autism, Asperger's syndrome, childhood disintegrative disorder and an unspecified form of pervasive developmental disorder. Some people still use the term "Asperger's syndrome," which is generally thought to be at the mild end of autism spectrum disorder.

Autism spectrum disorder begins in early childhood and eventually causes problems functioning in society — socially, in school and at work, for example. Often children show symptoms of autism within the first year. A small number of children appear to develop normally in the first year, and then go through a period of regression between 18 and 24 months of age when they develop autism symptoms.

While there is no cure for autism spectrum disorder, intensive, early treatment can make a big difference in the lives of many children.

Products & Services

- Children’s Book: My Life Beyond Autism

Some children show signs of autism spectrum disorder in early infancy, such as reduced eye contact, lack of response to their name or indifference to caregivers. Other children may develop normally for the first few months or years of life, but then suddenly become withdrawn or aggressive or lose language skills they've already acquired. Signs usually are seen by age 2 years.

Each child with autism spectrum disorder is likely to have a unique pattern of behavior and level of severity — from low functioning to high functioning.

Some children with autism spectrum disorder have difficulty learning, and some have signs of lower than normal intelligence. Other children with the disorder have normal to high intelligence — they learn quickly, yet have trouble communicating and applying what they know in everyday life and adjusting to social situations.

Because of the unique mixture of symptoms in each child, severity can sometimes be difficult to determine. It's generally based on the level of impairments and how they impact the ability to function.

Below are some common signs shown by people who have autism spectrum disorder.

Social communication and interaction

A child or adult with autism spectrum disorder may have problems with social interaction and communication skills, including any of these signs:

- Fails to respond to his or her name or appears not to hear you at times

- Resists cuddling and holding, and seems to prefer playing alone, retreating into his or her own world

- Has poor eye contact and lacks facial expression

- Doesn't speak or has delayed speech, or loses previous ability to say words or sentences

- Can't start a conversation or keep one going, or only starts one to make requests or label items

- Speaks with an abnormal tone or rhythm and may use a singsong voice or robot-like speech

- Repeats words or phrases verbatim, but doesn't understand how to use them

- Doesn't appear to understand simple questions or directions

- Doesn't express emotions or feelings and appears unaware of others' feelings

- Doesn't point at or bring objects to share interest

- Inappropriately approaches a social interaction by being passive, aggressive or disruptive

- Has difficulty recognizing nonverbal cues, such as interpreting other people's facial expressions, body postures or tone of voice

Patterns of behavior

A child or adult with autism spectrum disorder may have limited, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests or activities, including any of these signs:

- Performs repetitive movements, such as rocking, spinning or hand flapping

- Performs activities that could cause self-harm, such as biting or head-banging

- Develops specific routines or rituals and becomes disturbed at the slightest change

- Has problems with coordination or has odd movement patterns, such as clumsiness or walking on toes, and has odd, stiff or exaggerated body language

- Is fascinated by details of an object, such as the spinning wheels of a toy car, but doesn't understand the overall purpose or function of the object

- Is unusually sensitive to light, sound or touch, yet may be indifferent to pain or temperature

- Doesn't engage in imitative or make-believe play

- Fixates on an object or activity with abnormal intensity or focus

- Has specific food preferences, such as eating only a few foods, or refusing foods with a certain texture

As they mature, some children with autism spectrum disorder become more engaged with others and show fewer disturbances in behavior. Some, usually those with the least severe problems, eventually may lead normal or near-normal lives. Others, however, continue to have difficulty with language or social skills, and the teen years can bring worse behavioral and emotional problems.

When to see a doctor

Babies develop at their own pace, and many don't follow exact timelines found in some parenting books. But children with autism spectrum disorder usually show some signs of delayed development before age 2 years.

If you're concerned about your child's development or you suspect that your child may have autism spectrum disorder, discuss your concerns with your doctor. The symptoms associated with the disorder can also be linked with other developmental disorders.

Signs of autism spectrum disorder often appear early in development when there are obvious delays in language skills and social interactions. Your doctor may recommend developmental tests to identify if your child has delays in cognitive, language and social skills, if your child:

- Doesn't respond with a smile or happy expression by 6 months

- Doesn't mimic sounds or facial expressions by 9 months

- Doesn't babble or coo by 12 months

- Doesn't gesture — such as point or wave — by 14 months

- Doesn't say single words by 16 months

- Doesn't play "make-believe" or pretend by 18 months

- Doesn't say two-word phrases by 24 months

- Loses language skills or social skills at any age

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

Autism spectrum disorder has no single known cause. Given the complexity of the disorder, and the fact that symptoms and severity vary, there are probably many causes. Both genetics and environment may play a role.

- Genetics. Several different genes appear to be involved in autism spectrum disorder. For some children, autism spectrum disorder can be associated with a genetic disorder, such as Rett syndrome or fragile X syndrome. For other children, genetic changes (mutations) may increase the risk of autism spectrum disorder. Still other genes may affect brain development or the way that brain cells communicate, or they may determine the severity of symptoms. Some genetic mutations seem to be inherited, while others occur spontaneously.

- Environmental factors. Researchers are currently exploring whether factors such as viral infections, medications or complications during pregnancy, or air pollutants play a role in triggering autism spectrum disorder.

No link between vaccines and autism spectrum disorder

One of the greatest controversies in autism spectrum disorder centers on whether a link exists between the disorder and childhood vaccines. Despite extensive research, no reliable study has shown a link between autism spectrum disorder and any vaccines. In fact, the original study that ignited the debate years ago has been retracted due to poor design and questionable research methods.

Avoiding childhood vaccinations can place your child and others in danger of catching and spreading serious diseases, including whooping cough (pertussis), measles or mumps.

Risk factors

The number of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder is rising. It's not clear whether this is due to better detection and reporting or a real increase in the number of cases, or both.

Autism spectrum disorder affects children of all races and nationalities, but certain factors increase a child's risk. These may include:

- Your child's sex. Boys are about four times more likely to develop autism spectrum disorder than girls are.

- Family history. Families who have one child with autism spectrum disorder have an increased risk of having another child with the disorder. It's also not uncommon for parents or relatives of a child with autism spectrum disorder to have minor problems with social or communication skills themselves or to engage in certain behaviors typical of the disorder.

- Other disorders. Children with certain medical conditions have a higher than normal risk of autism spectrum disorder or autism-like symptoms. Examples include fragile X syndrome, an inherited disorder that causes intellectual problems; tuberous sclerosis, a condition in which benign tumors develop in the brain; and Rett syndrome, a genetic condition occurring almost exclusively in girls, which causes slowing of head growth, intellectual disability and loss of purposeful hand use.

- Extremely preterm babies. Babies born before 26 weeks of gestation may have a greater risk of autism spectrum disorder.

- Parents' ages. There may be a connection between children born to older parents and autism spectrum disorder, but more research is necessary to establish this link.

Complications

Problems with social interactions, communication and behavior can lead to:

- Problems in school and with successful learning

- Employment problems

- Inability to live independently

- Social isolation

- Stress within the family

- Victimization and being bullied

More Information

- Autism spectrum disorder and digestive symptoms

There's no way to prevent autism spectrum disorder, but there are treatment options. Early diagnosis and intervention is most helpful and can improve behavior, skills and language development. However, intervention is helpful at any age. Though children usually don't outgrow autism spectrum disorder symptoms, they may learn to function well.

- Autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/facts.html. Accessed April 4, 2017.

- Uno Y, et al. Early exposure to the combined measles-mumps-rubella vaccine and thimerosal-containing vaccines and risk of autism spectrum disorder. Vaccine. 2015;33:2511.

- Taylor LE, et al. Vaccines are not associated with autism: An evidence-based meta-analysis of case-control and cohort studies. Vaccine. 2014;32:3623.

- Weissman L, et al. Autism spectrum disorder in children and adolescents: Overview of management. https://www.uptodate.com/home. Accessed April 4, 2017.

- Autism spectrum disorder. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-5. 5th ed. Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. http://dsm.psychiatryonline.org. Accessed April 4, 2017.

- Weissman L, et al. Autism spectrum disorder in children and adolescents: Complementary and alternative therapies. https://www.uptodate.com/home. Accessed April 4, 2017.

- Augustyn M. Autism spectrum disorder: Terminology, epidemiology, and pathogenesis. https://www.uptodate.com/home. Accessed April 4, 2017.

- Bridgemohan C. Autism spectrum disorder: Surveillance and screening in primary care. https://www.uptodate.com/home. Accessed April 4, 2017.

- Levy SE, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine treatments for children with autism spectrum disorder. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2015;24:117.

- Brondino N, et al. Complementary and alternative therapies for autism spectrum disorder. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/258589. Accessed April 4, 2017.

- Volkmar F, et al. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;53:237.

- Autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/autism/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed April 4, 2017.

- American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement: Sensory integration therapies for children with developmental and behavioral disorders. Pediatrics. 2012;129:1186.

- James S, et al. Chelation for autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD010766.pub2/abstract;jsessionid=9467860F2028507DFC5B69615F622F78.f04t02. Accessed April 4, 2017.

- Van Schalkwyk GI, et al. Autism spectrum disorders: Challenges and opportunities for transition to adulthood. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2017;26:329.

- Autism. Natural Medicines. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com. Accessed April 4, 2017.

- Autism: Beware of potentially dangerous therapies and products. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm394757.htm?source=govdelivery&utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery. Accessed May 19, 2017.

- Drutz JE. Autism spectrum disorder and chronic disease: No evidence for vaccines or thimerosal as a contributing factor. https://www.uptodate.com/home. Accessed May 19, 2017.

- Weissman L, et al. Autism spectrum disorder in children and adolescents: Behavioral and educational interventions. https://www.uptodate.com/home. Accessed May 19, 2017.

- Huebner AR (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. June 7, 2017.

Associated Procedures

- Cognitive behavioral therapy

News from Mayo Clinic

- 10 significant studies from Mayo Clinic's Center for Individualized Medicine in 2023 Dec. 30, 2023, 12:00 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic 'mini-brain' study reveals possible key link to autism spectrum disorder Aug. 10, 2023, 04:00 p.m. CDT

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

- Doctors & departments

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

Understanding Autism: Online Presentations

Video Presentations

The Understanding Autism: Professional Development Curriculum is a comprehensive professional development training tool that prepares secondary school teachers to serve the autism population.

This page includes two presentations:

- Part 1: Characteristics and Practices for Challenging Behavior

- Part 2: Strategies for Classroom Success and Effective Use of Teacher Supports

Understanding Autism: A Guide for Secondary School Teachers

Presentation a, understanding autism: professional development curriculum.

Developed in collaboration with the Center on Secondary Education for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorders (CSESA) , the Understanding Autism Professional Development Curriculum is built around two 75-minute presentations that school staff can adapt to meet any schedule constraints:

Characteristics and Practices for Challenging Behavior

Start Part 1

Strategies for Classroom Success and Effective use of Teacher Supports

Start Part 2

This ready-made, flexible resource supports all types of professional development – large group (e.g. staff meetings or in-services), small teams (e.g. professional learning communities and department meetings), self-study, and/or one-on-one coaching. Any school or district staff members who are familiar with autism can implement the curriculum. Each presentation includes video clips and comes with slide-by-slide notes for facilitators, handouts, and activity worksheets to help participants apply learned concepts to their own classrooms.

Part 1: Challenging Behaviors

Printable Materials

- Presentation Slides

- Facilitator Notes

- Participant Handout

- Activity Worksheet

- At My School Worksheet

General Characteristics Of Autism (Video Clip 1.1)

Hidden Curriculum (Video Clip 1.2)

Repetitive Behaviors And Restricted Interests (Video Clip 1.3)

Capitalizing On Strengths (Video Clip 1.4)

Rumbling Stage Pt 1 (Video Clip 1.5)

Rumbling Stage Pt 2 (Video Clip 1.6)

Meltdown Stage Pt 1 (Video Clip 1.7)

Meltdown Stage Pt 2 (Video Clip 1.8)

Recovery Stage (Video Clip 1.9)

Part 2: Classroom Strategies

Strategies for classroom success and effective use of teacher supports, classroom supports (video clip 2.1).

Hypersensitivities (Video Clip 2.2)

Priming (Video Clip 2.3)

Examples of Academic Modifications (Video Clip 2.4)

Examples of Visual Supports (Video Clip 2.5)

Presentation B

Understanding Autism: A Guide for Secondary School Teachers provides teachers with strategies for supporting their middle and high school students with autism. We produced it in collaboration with Fairfax County (VA) Public Schools and with financial support from the American Legion Child Welfare Foundation and the Doug Flutie Jr. Foundation for Autism

- Download the PDF Guide

Segment One: Characteristics (18M:34S)

At the end of this segment, viewers will be able to:

- Describe how autism impacts learners

- Indicate how the characteristics of autism impacts individuals in a school setting

- Understand that autism manifests itself differently in individual learners

Segment Two: Integrating Supports in the Classroom (15M:28S)

- Match interventions to learner strengths, skills, and interests

- Describe how priming can be used in a classroom setting

- Discuss the types of academic supports that a learner might need to be successful in a general education setting

- Create a home base for a student with autism

- Provide examples of visual supports to enhance the skills acquisition of learners with autism

- Integrate reinforcement into the daily schedule of the student with autism

Segment Three: Practices for Challenging Behavior (17M:47S)

- Understand that meltdown behavior is not purposeful for the learner on the spectrum

- Describe the stages of a meltdown

- Discuss interventions that can be used at each of the stages of a meltdown

Segment Four: Effective Use of Teacher Supports (12M:00S)

- Describe how to use information from the IEP to develop an implementation plan for the learner with autism in the general education classroom

- Identify the multiple ways that general and special educators can work together to support a learner with autism in the general education classroom

- Discuss guidelines for supporting a paraprofessional in working with the learner with autism in the general education classroom

Our Newsletter

You’ll receive periodic updates and articles from OAR

- Common misconceptions

- Set Your Location

- Learn the signs

- Symptoms of autism

- What causes autism?

- Asperger syndrome

- Autism statistics and facts

- Learn about screening

- Screening questionnaire

- First Concern to Action

- Autism diagnosis criteria: DSM-5

- Newly diagnosed

- Associated conditions

- Sensory issues

- Interventions

- Access services

- Caregiver Skills Training (CST)

- Information by topic

- Resource Guide

- Autism Response Team

- Our mission

- Our grantmaking

- Research programs

- Autism by the Numbers

- Fundraising & events

- World Autism Month

- Social fundraising

- Ways to give

- Memorial & tributes

- Workplace giving

- Corporate partnership

- Become a partner

- Ways to engage

- Meet our Partners

- Deteccion de autismo

- Deteccion temprana

- My Autism Guide

- Select Your Location

Please enter your location to help us display the correct information for your area.

- What is autism?

- Autism screening

- What causes autism

- Early signs of autism

- Signs of autism in adults

- Signs of autism in women and girls

- Autism diagnosis criteria

- Autism severity levels

- Child diagnosis

- Adult diagnosis

Autism definition

Autism, or autism spectrum disorder (ASD), refers to a broad range of conditions characterized by challenges with social skills, repetitive behaviors, speech and nonverbal communication. According to the Centers for Disease Control, autism affects an estimated 1 in 36 children and 1 in 45 adults in the United States today.

We know that there is not one type of autism, but many.

Autism looks different for everyone, and each person with autism has a distinct set of strengths and challenges. Some autistic people can speak, while others are nonverbal or minimally verbal and communicate in other ways. Some have intellectual disabilities, while some do not. Some require significant support in their daily lives, while others need less support and, in some cases, live entirely independently.

On average, autism is diagnosed around age 5 in the U.S. , with signs appearing by age 2 or 3. Current diagnostic guidelines in the DSM-5-TR break down the ASD diagnosis into three levels based on the amount of support a person might need: level 1, level 2, and level 3. See more information about each level .

Many people with autism experience other medical, behavioral or mental health issues that affect their quality of life.

Among the most common co-occurring conditions are:

- attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- anxiety and depression

- gastrointestinal (GI) disorders

- seizures and sleep disorders

Anybody can be autistic, regardless of sex, age, race or ethnicity. However, research from the CDC says that boys get diagnosed with autism four times more often than girls. According to the DSM-5-TR, the diagnostic manual for ASD, autism may look different in girls and boys. Girls may have more subtle presentation of symptoms, fewer social and communication challenges, and fewer repetitive behaviors. Their symptoms may go unrecognized by doctors, often leading to underdiagnosis or misdiagnosis. Getting a diagnosis is also harder for autistic adults, who often learn to “mask”, or hide, their autism symptoms.

Autism is a lifelong condition, and an autistic person’s needs, strengths and challenges may change over time. As they transition through life stages, they may need different types of support and accommodations. Early intervention and therapies can make a big difference in a person’s skills and outcomes later in life.

There is no one type of autism, but many. - Stephen Shore

Related resources

- M-CHAT-R Screening Questionnaire : Do you suspect your child might have autism? Take this two-minute screening questionnaire. You can use the results of the screener to discuss any concerns that you may have with your child’s health care provider.

- First Concern to Action Tool Kit : If you have concerns about how your child is communicating, interacting or behaving, you are probably wondering what to do next. This Tool Kit offers resources to help guide you on the journey from your first concern to action.

- We also offer guides for grandparents and siblings .

- 100 Day Kit for Young Children : Knowledge is power, particularly in the days after an autism diagnosis. If your child is age 4 and under, this Tool Kit can help you make the best possible use of the 100 days following the diagnosis.

- 100 Day Kit for School Age Children : If your child is between ages 5 and 13 and was just diagnosed with ASD, this Tool Kit can help you learn more about autism and how to access the services that your child needs.

- Adult Autism Diagnosis Tool Kit : Are you an adult who suspects you may have autism? Have you been recently diagnosed with ASD? Developed by and for autistic adults, this guide can help you figure out what comes next .

- Find local providers and services in your area with the Autism Speaks Resource Guide .

Contact the Autism Response Team

Autism Speaks' Autism Response Team can help you with information, resources and opportunities.

- In English: 888-288-4762 | [email protected]

- En Español: 888-772-9050 | [email protected]

Assessment of Autism in Females and Nuanced Presentations

Integrating Research into Practice

- Terisa P. Gabrielsen ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4955-6419 0 ,

- K. Kawena Begay ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7978-9996 1 ,

- Kathleen Campbell ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0923-8659 2 ,

- Katrina Hahn 3 ,

- Lucas T. Harrington 4

School of Education, Brigham Young Univeristy, Provo, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

School of Education, University of Washington Tacoma, Tacoma, USA

Developmental and behavioral pediatrics, children’s hospital of philadelphia, phildelphia, usa, developmental assessment clinics, university of utah, salt lake city, usa, autism center, university of washington, seattle, usa.

- Examines characteristics of autism in females and atypical presentations

- Provides a comprehensive framework and sensitive approach for assessing autism in females and others

- Discusses improved treatment and support across the lifespan for females and others with autism

4010 Accesses

2 Altmetric

- Table of contents

About this book

Authors and affiliations, about the authors, bibliographic information.

- Publish with us

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

Table of contents (13 chapters)

Front matter, sex, gender, autism, assessment, and equity for females.

- Terisa P. Gabrielsen, K. Kawena Begay, Kathleen Campbell, Katrina Hahn, Lucas T. Harrington

Early Identification of Females with Autism: Comprehensive Evaluation

Communication and language assessment in females with autism, assessment for sleep, feeding, sensory issues, and motor skills in females with autism, autism assessment of female social skills, play, imitation, camouflaging, intense interests, stimming behaviors, and safety, interpreting female social relationships: autism friendships and pragmatic language, autism assessment including reading, learning, and executive function in females, differential or co-occurring other common diagnoses prior to autism assessment, guidance for medical issues in female puberty, gender identity, pregnancy, parenting and menopause, underlying autism female eating disorders, self-injury, suicide, sexual victimization, and substance abuse, autism diagnosis in adult females: post-secondary education, careers, and autistic burnout, adult autism and social connections: living authentically, sexuality, partnering, parenting, and vulnerabilities, advocacy for neurodiversity, back matter.

- Autism, assessment, females

- ASD, identification, females

- Asperger syndrome, females

- Atypical autism, females

- Autism spectrum disorder (ASD), females

- Autism spectrum disorder diagnosis, females

- Autism, females

- Camouflaging, masking behaviors, autism

- Culture, autism, females

- Early childhood development, females, autism

- Eating disorder, autism, females

- Gender identity, autism, females

- Girls, autism, assessment

- Infants, toddlers, females, autism

- Language differences, autism, females

- Misdiagnosis, autism, females

- Race, autism, females

- Sex differences, autism, females

- Suicide, autism, females,

- Women, autism, assessment

This book examines autism characteristics that may be different than expected (atypical), primarily found in females, but also in others and are likely to be missed or misdiagnosed when identification and support are needed. It follows a lifespan framework, guiding readers through comprehensive assessment processes at any age. The book integrates interpretations of standardized measures, information from scientific literature, and context from first-person accounts to provide a more nuanced and sensitive approach to assessment. It addresses implications for improved treatment and supports based on comprehensive assessment processes and includes case studies within each age range to consolidate and illustrate assessment processes.

Key areas of coverage include:

- Interdisciplinary assessment processes, including psychology, speech and language pathology, education, and health care disciplines.

- Lifespan approach to comprehensive assessment of autism in females/atypical autism.

- Guide to interpretation of standardized measures in females/atypical autism.

- Additional assessment tools and processes to provide diagnostic clarity.

- Descriptions of barriers in diagnostic processes from first-person accounts.

- Intervention and support strategies tied to assessment data.

- In-depth explanations of evidence and at-a-glance summaries.

Assessment of Autism in Females and Nuanced Presentations is a must-have resource for researchers, professors, and graduate students as well as clinicians, practitioners, and policymakers in developmental and clinical psychology, speech language pathology, medicine, education, social work, mental health, and all interrelated disciplines.

Terisa P. Gabrielsen

K. Kawena Begay

Kathleen Campbell

Katrina Hahn

Lucas T. Harrington

Terisa P. Gabrielsen, Ph.D., NCSP, is an associate professor of School Psychology in the School of Education at Brigham Young University and a licensed psychologist. She has 15 years of interdisciplinary clinical and research experience in toddler, PreK-12, hospital, clinical, and research settings. Her specialties are early identification of autism, social skills interventions, and building community capacity in autism services.

Kristin Kawena Begay, Ph.D., NCSP, is an assistant professor in the School of Education at the University of Washington, Tacoma. She is a licensed psychologist and nationally certified school psychologist with 20 years of experience working in culturally and linguistically diverse PreK-12, university, and clinic settings. Dr. Begay has served in a variety of roles, including classroom teacher, counselor, school psychologist, licensed psychologist, trainer, and consultant.

Kathleen Campbell, M.D., MHSc, isa pediatrician and pursuing fellowship training in developmental and behavioral pediatrics at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. She has clinical experience and has published research relating to screening, diagnosis, and medical care of autistic children.

Katrina Hahn, MEd, CCC-SLP, is a speech and language pathologist with the University of Utah Developmental Assessment Clinics. She has 19 years of experience in various capacities in early intervention, PreK-12, and clinical settings. Ms. Hahn specializes in the identification, evaluation, and therapy planning for social-emotional development and pragmatic language for individuals with autism.

Lucas T. Harrington, PsyD is a licensed clinical psychologist at the University of Washington Autism Center. He is autistic and personally experienced the challenges of seeking evaluation as an adult who was assigned female at birth. Dr. Harrington provides neurodiversity-affirming services for autistic people and their supporters in various areas, including diagnostic evaluation, individual therapy, parent coaching, and consultation/training. Dr. Harrington has also been known professionally as Natasha Harrington, PsyD.

Book Title : Assessment of Autism in Females and Nuanced Presentations

Book Subtitle : Integrating Research into Practice

Authors : Terisa P. Gabrielsen, K. Kawena Begay, Kathleen Campbell, Katrina Hahn, Lucas T. Harrington

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-33969-1

Publisher : Springer Cham

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology , Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Copyright Information : The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2023

Hardcover ISBN : 978-3-031-33968-4 Published: 10 September 2023

Softcover ISBN : 978-3-031-33971-4 Due: 11 October 2023

eBook ISBN : 978-3-031-33969-1 Published: 09 September 2023

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XXX, 259

Number of Illustrations : 3 b/w illustrations

Topics : Developmental Psychology , Child and Adolescent Psychiatry , Child and School Psychology , Education, general , Clinical Psychology , Public Health

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Recognizing Autism in Females

What makes women different..

Posted March 31, 2022 | Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

- What Is Autism?

- Find a therapist to help with autism

- Autism presents very differently in females and it is important to recognize these differences

- Females are very good at camouflaging the symptoms of autism, which can lead to increased anxiety and depression.

- Early intervention in females can lead to improved outcomes and reduced risk for victimization.

Research shows females receive Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) diagnoses later than males and that they are underdiagnosed and often misdiagnosed (Leedham, Thompson, smith, Freeth, 2019). It is believed this can partly be attributed to the fact that our knowledge of autism has largely been based on male samples (Gould & Ashton- Smith, 2011). Females’ ability to mask and hide their symptoms has also made it harder for clinicians and parents to recognize the signs of ASD in females. It can also be argued that it isn’t just our scientific study of ASD that has been based on male samples, but that our pop culture and cultural understandings of ASD are also usually based on male images. When most of us think of people with autism in pop culture, we think of males. I missed the symptoms of autism in myself for years because I couldn't relate to the images of autism I had been shown in the media.

So what does autism look like in women? Although women meet the same diagnostic criteria as their male counterparts, there are many ways in which it is unique in females.

Camouflaging or Masking

Unlike the media representations of autism, females on the spectrum usually report being painfully aware that they are not like their peers, and they attempt to adjust for this by mimicking the behaviors of others and trying to hide behaviors they perceive as abnormal. It is important to note that males mask too, but not as frequently as females. They try to act like the “normal” kids, or what they perceive normal to be. They mask.

This process causes significant anxiety and can cause meltdowns and emotional exhaustion because it is exhausting for those of us with autism. For me, masking feels like you are being asked to perform in a new play with no script and no director to an audience composed entirely of critics.

- Eating Disorders

Many females with autism are misdiagnosed with eating disorders, according to Spek et al. (2020, Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders). People with ASD experience a multitude of eating problems and women with ASD are often recognized as having eating disorders. As sensory issues are one of the hallmarks of autism, it isn’t a surprise that people with ASD struggle with eating. In females, this can be mixed with societal pressure to conform to social norms regarding eating and commonly leads to symptoms of anorexia, bulimia, and binge eating disorder .

Restricted Interests That Are Intense but Not as Obvious

Females have restricted interests in different things than are expected. Studies have shown that males tend to be more interested in mechanical topics as females tend to be more interested in relationships, people, animals, fictional characters and worlds, or psychology (Grove et al. 2018). Males and females both have hyper-fixated and restricted interests but many of my female clients get fixated on things like Dungeons and Dragons, animals, world-building, books, bones, autism itself, and television shows.

I have had so many collections and interests over the years, I can hardly keep count. I once became so interested in collecting ghost stories, a publishing house noticed my activity and offered me a publishing deal, which lead to three books. This was not my job; it was a consuming and restricted interest. People definitely thought I was odd and told me to my face that I was odd, but because I didn’t meet the stereotype, no one would have thought I had ASD. I worked with one girl who spent 8-10 hours a day crafting different role-playing game worlds for their friends to play online. I had another who collected bones. The restricted interests are there but they aren't what people expect.

Social Interactions Are Difficult and Draining

According to a survey we conducted here at Tree of Life Behavioral Health, many females with autism have difficulty obtaining and maintaining friendships and acquaintances. They lose friends and they don’t usually understand why. They feel rejected and isolated because the nuanced interactions that lead to deep bonding are a constant mystery.

Although females with ASD may appear normal in social interactions, if you talk to them, they will tell you that those interactions are a constant source of stress and anxiety. Females with ASD describe themselves as aliens and outsiders who can never quite navigate other humans. They struggle constantly with feelings of isolation and alienation.

Most Females Are Misdiagnosed Prior to Their Autism Diagnosis

Most females with autism are diagnosed with anxiety, depression , borderline personality disorder , or bipolar disorder prior to their diagnosis with autism. In general, people with autism do have higher rates of depression and anxiety. They feel like outsiders, aliens, and they struggle with social isolation , all of which can lead to both depression and anxiety. Females are often misdiagnosed with borderline personality disorder because they have difficulty regulating their emotions and they struggle with relationships and social interactions. This inability to regulate their emotions often leads to bipolar diagnoses as well.

These factors, combined with the fact that many clinicians don’t understand autism well and understand the presentation of autism in females even less well, contribute to a perfect storm in which many clinicians adhere to preconceived notions and give females the diagnoses that are more common to females.

Fantasy Worlds

According to Hendrickx (2015), one of the most common differences between male and female ASD presentation is the presence of imaginary play. One of the things most people who test and screen for ASD look for is a lack of imagination or limited imaginary play. However, girls with autism have described this to be almost the opposite: They may live in an atypically rich world of imagination with multiple imaginary friends.

Most of my clients get lost in role-playing games and books and the fictional characters in their books and movies can be more real to them than their peers. They can relate to fictional characters and understand their motives and backstories as real people are hidden and difficult.

One of my projects over the last year has been looking at females with autism and trauma . According to Buuren et al. (2021), people with autism show a higher risk of adverse events and trauma. Females with autism are even more at risk. In a survey done at my clinic, 90% of the sample of females with ASD also met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD . This makes it very difficult to see the symptoms of autism because often they are mixed with symptoms of PTSD. Many of the females we surveyed felt they were more vulnerable to being victimized because of their undiagnosed and untreated ASD. In a world filled with people they don’t understand, how can they tell which people are dangerous and which are safe?

Buuren, Ella Logregt-van, Hoekert, Marjolijn, &Sizoo, Bram (2021). Autism Adverse Events, and Trauma. Autism Spectrum Disorders. Chapter 3.

Agniezka, Rynkiewicz, Janas-Kozik, Malgorzata, & Slopien, Agniezka (2019), Girls and women with autism. Psychiatry Poland. 53(4):737-752

Gould, J & Ashton Smith, J. (2011). Missed diagnosis or misdiagnosis? Girls and women on th3e autism Spectrum. Good Autism Practice. 12

Grove, R., Hoekstra, R.A., Wierda, M, Begeer, S ( 2018). Special Interests and subjective wellbeing in autistic adults. Autism Research. 11(%), 766-775.

Hendrickx, Sarah. (2015). Women and Girls with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Understanding Life Experiences from Early Childhood to Old Age. Jessica Kinsley Publisher. London

Lai, Meng-Chuan, Baron-Cohen, Simon, & Buxbaum, Joseph D. (2015). Understanding autism in the light of sex/gender. Molecular Autism. 6:24

Leedham, Alexandra, Thompson A. R. Smith, R, Freeth, M (2019). ‘I was exhausted trying to figure it out: The experiences of females receiving an autism diagnosis in middle to late adulthood. Autsim.

Spek, A. Rijnsoever, Wendy. % Kiep, Michele (2020), Eating Problems in Men and Women with an Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders.

Jessica Penot, LPC, is the founder and director of Tree of Life Behavioral Health in Madison, Alabama and the author of 10 books including the bestselling novel, The Accidental Witch.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Signs and Symptoms of Autism Spectrum Disorder

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a developmental disability caused by differences in the brain. People with ASD often have problems with social communication and interaction, and restricted or repetitive behaviors or interests. People with ASD may also have different ways of learning, moving, or paying attention. It is important to note that some people without ASD might also have some of these symptoms. But for people with ASD, these characteristics can make life very challenging.

Learn more about ASD

Social Communication and Interaction Skills

Social communication and interaction skills can be challenging for people with ASD.

Examples of social communication and social interaction characteristics related to ASD can include

- Avoids or does not keep eye contact

- Does not respond to name by 9 months of age

- Does not show facial expressions like happy, sad, angry, and surprised by 9 months of age

- Does not play simple interactive games like pat-a-cake by 12 months of age

- Uses few or no gestures by 12 months of age (for example, does not wave goodbye)

- Does not share interests with others by 15 months of age (for example, shows you an object that they like)

- Does not point to show you something interesting by 18 months of age

- Does not notice when others are hurt or upset by 24 months of age

- Does not notice other children and join them in play by 36 months of age

- Does not pretend to be something else, like a teacher or superhero, during play by 48 months of age

- Does not sing, dance, or act for you by 60 months of age

Restricted or Repetitive Behaviors or Interests

People with ASD have behaviors or interests that can seem unusual. These behaviors or interests set ASD apart from conditions defined by problems with social communication and interaction only.

Examples of restricted or repetitive behaviors and interests related to ASD can include

- Lines up toys or other objects and gets upset when order is changed

- Repeats words or phrases over and over (called echolalia)

- Plays with toys the same way every time

- Is focused on parts of objects (for example, wheels)

- Gets upset by minor changes

- Has obsessive interests

- Must follow certain routines

- Flaps hands, rocks body, or spins self in circles

- Has unusual reactions to the way things sound, smell, taste, look, or feel

Other Characteristics

Most people with ASD have other related characteristics. These might include

- Delayed language skills

- Delayed movement skills

- Delayed cognitive or learning skills

- Hyperactive, impulsive, and/or inattentive behavior

- Epilepsy or seizure disorder

- Unusual eating and sleeping habits

- Gastrointestinal issues (for example, constipation)

- Unusual mood or emotional reactions

- Anxiety, stress, or excessive worry

- Lack of fear or more fear than expected

It is important to note that children with ASD may not have all or any of the behaviors listed as examples here.

Learn more about screening and diagnosis of ASD

Learn more about treating the symptoms of ASD

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Grabrucker AM, editor. Autism Spectrum Disorders [Internet]. Brisbane (AU): Exon Publications; 2021 Aug 20. doi: 10.36255/exonpublications.autismspectrumdisorders.2021.diagnosis

Autism Spectrum Disorders [Internet].

Chapter 2 autism spectrum disorders: diagnosis and treatment.

Ronan Lordan , Cristiano Storni , and Chiara Alessia De Benedictis .

Affiliations

The diagnostic criteria and treatment approaches of autism spectrum disorders (ASD) have changed greatly over the years. Currently, diagnosis is conducted mainly by observational screening tools that measure a child’s social and cognitive abilities. The two main tools used in the diagnosis of ASD are DSM-5 and M-CHAT, which examine persistent deficits in interaction and social communication, and analyze responses to “yes/no” items that cover different developmental domains to formulate a diagnosis. Treatment depends on severity and comorbidities, which can include behavioral training, pharmacological use, and dietary supplement. Behavior-oriented treatments include a series of programs that aim to re-condition target behaviors, and develop vocational, social, cognitive, and living skills. However, to date, no single or combination treatments have been able to reverse ASD completely. This chapter provides an overview of the current diagnostic and treatment strategies of ASD.

- INTRODUCTION

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are complex, highly heritable neurodevelopmental diseases characterized by individuals with a combination of behavioral and cognitive impairments. These include impaired or diminished social communication skills, repetitive behaviors, and restricted sensory processing or interests ( 1 – 3 ). Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler first coined the term autism in 1908 to describe symptoms associated with severe schizophrenia, hallucinations, and unconscious fantasy in infants. Since then, the classification, diagnosis, and meaning of autism have radically changed ( 4 ). Between the 1940s and 1980s, ASD was described as abnormalities in language development, display of ritualistic and compulsive behaviors, and disturbance in interpersonal relationships. In the 1970s, sensory deficits in infancy were recognized in autistic children and became a defining feature of ASD ( 4 ). In 1980, the 3 rd edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-III), listed autism as a subgroup within the diagnostic category of pervasive developmental disorders (PDD) to convey the view that there is a broader spectrum of social communication deficits. The PPD contained four categories: infantile autism, childhood-onset PDD, residual autism, and an atypical form ( 5 ). At this point, it was recognized that the previously described symptomatology resembling schizophrenia was not a component of ASD because of the research conducted by Kolvin Rutter and others in the early 1970s. Consequently, childhood schizophrenia was excluded from DSM-III ( 1 , 4 ). In the 1980s, Wing and Gould placed autistic children on a continuum with other abnormal children and discussed autism in behavioral terms rather than psychosis ( 4 , 6 ).

Asperger’s syndrome, an ASD named after Hans Asperger, who first described its symptomatology in 1944, gained prominence in the ASD literature due to the works of psychiatrist Lorna Wing, who coined the term in 1976 ( 4 ). In 1981, Wing proposed that autism is part of a wider group of conditions that share commonalities, including impairments of communication, imagination, and social interactions. Asperger’s syndrome was eventually included in the DSM-IV in 1994 ( 7 ). In the mid to late 1980s, works by Simon Baron-Cohen, Uta Frith, and Alan Leslie led to the hypothesis that autistic children lacked “theory of mind”, which is the ability to attribute mental states to others and ourselves, an essential component of social interaction ( 8 ). In 1990, autism was first classified as a disability ( 9 ). Moving to the present day, due to the difficulty in defining and distinguishing between the various PDD, DSM-5 and the International Classification of Diseases 11 th revision use ‘ASD’ as a blanket term and distinguish individuals using clinical specifiers and modifiers ( 1 ). Our knowledge of pathology, etiology, and behavior of ASD continues to evolve. Nowadays, ASD is widely recognized as a somewhat common condition that, for many, but not all, requires lifelong support ( 2 ).

The diagnostic features historically associated with ASD are a triad of impaired social interactions, verbal and nonverbal communication deficits, and restricted, repetitive behavior patterns. These core features are observed irrespective of race, ethnicity, culture, or socioeconomic status. However, ASD individuals tend to differ from one another, so one feature may be more prevalent than another ( 2 , 10 ) (see Chapter 1 ). Despite recent advancements, there are currently no reliable biomarkers for ASD ( 11 ). Consequently, today’s clinical diagnosis of ASD is based on assessing behaviors as outlined in APA’s DSM-5 criteria ( 2 , 12 ). Other disorders that may co-occur with ASD. These include psychiatric disorders such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which is considered the most common comorbidity in people with ASD (~ 28%) ( 13 ), along with other conditions and diseases including anxiety and phobias, dissociative disorders, depression, bipolar disorder, and episodic mood disorders ( 13 , 14 ). Physiological disorders (e.g., gastrointestinal disorders) and genetic disorders (e.g., fragile X syndrome) may also be prevalent ( 2 , 14 ).

Hallmarks of ASD and gender prevalence

In 2010, the prevalence of autism was estimated to be 1 in 132 individuals (7.6 per 1,000), affecting approximately 52 million people globally ( 15 ). However, estimates can vary due to the diagnostic methodologies used and the definition of ASD adopted in studies. It was approximated in 2016 that 1 in 54 children in the USA was diagnosed with ASD ( 16 ). Generally, there appears to be epidemiological evidence of ASD sexual dimorphism. ASD is more prevalent in males than females in a ratio of 3:1, ranging from 2:1 to 5:1 ( 17 ). However, it has been proposed that females are more likely to be diagnosed with ASD later than males or may never be diagnosed ( 18 ). Biological determinants are now under investigation to resolve whether females have better adaptation/compensatory behaviors or if diagnostic biases play a role ( 19 , 20 ).

Persistent issues with social communication can manifest in various contexts. For example, ASD individuals may persistently fail to hold a normal conversation or have an unorthodox approach to social situations. Some ASD individuals may also present deficits in non-verbal communication behaviors such as difficulty maintaining eye contact or abnormalities in using or understanding body language or gestures. ASD individuals may also have trouble understanding relationships or social interactions that may lead them to have difficulties developing and maintaining relationships ( 2 ). Repetitive or restricted behavioral patterns include movements, speech, play, use of objects, resistance to change, and insistence on sameness. In addition, fixations on certain interests with abnormal focus or intensity or periods of hyperactivity and hypoactivity in response to sensory inputs are also associated with ASD. These symptoms are mostly present in early life but may not fully manifest until social interaction is warranted. These symptoms can be somewhat masked later in life by coping strategies learned ( 2 ).

Early signs and symptoms

Early identification and evaluation of ASD in children has become an important public health objective due to the potential association between early intervention and improved development of children with ASD ( 21 – 23 ). Early presentation of ASD often occurs due to parental concerns spurred by recognizing some of the hallmarks of ASD previously outlined ( 24 ), which has increased due to greater awareness of ASD hallmarks among parents, healthcare specialists, and childcare workers ( 25 ). Some video studies suggest that it is possible to identify symptoms of ASD in children as young as 6–12 months old ( 26 , 27 ). There is increased interest to monitor the emergence of ASD prodromes such as reduced motor control or abnormal social development in the first year of life ( 24 , 28 ). As research has developed, it is now known that the prevalence of ASD is particularly high in preterm infants ( 29 ), indicating a requirement for additional vigilance in the preterm population.

Diagnostic tools

Numerous diagnostic guidelines of varying quality are available ( 30 ). The essential features of ASD diagnosis include observing a child’s relationship and exchange with their parents and with an individual unknown to the child during unstructured and structured assessment activities and a detailed history of the child’s development ( 1 ). ASD diagnosis can occur at any age but most frequently occurs early in childhood. Although there is a lack of a universal screening instruments, public health systems in various countries in Europe such as Spain and Ireland have programs in place to identify young children with ASD (~ 18–30 months) using M-CHAT (Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers) and similar tools ( 31 ). The sensitivity of these screening methods has been questioned as they fail to identify most children with ASD before their parents have already reported delayed development ( 32 ). There may also be racial disparities in early diagnosis of Black and Hispanic children versus white children, which has been reported in the United States. It was found that the first evaluation of ASD in Black children is less likely to occur by 36 months of age than in white children with ASD (40% early evaluation of black children versus 45% of white children) ( 33 ).