No evidence that depression is caused by low serotonin levels, finds comprehensive review

After decades of study, there remains no clear evidence that serotonin levels or serotonin activity are responsible for depression, according to a major review of prior research led by UCL scientists.

The new umbrella review -- an overview of existing meta-analyses and systematic reviews -- published in Molecular Psychiatry , suggests that depression is not likely caused by a chemical imbalance, and calls into question what antidepressants do. Most antidepressants are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which were originally said to work by correcting abnormally low serotonin levels. There is no other accepted pharmacological mechanism by which antidepressants affect the symptoms of depression.

Lead author Professor Joanna Moncrieff, a Professor of Psychiatry at UCL and a consultant psychiatrist at North East London NHS Foundation Trust (NELFT), said: "It is always difficult to prove a negative, but I think we can safely say that after a vast amount of research conducted over several decades, there is no convincing evidence that depression is caused by serotonin abnormalities, particularly by lower levels or reduced activity of serotonin.

"The popularity of the 'chemical imbalance' theory of depression has coincided with a huge increase in the use of antidepressants. Prescriptions for antidepressants have risen dramatically since the 1990s, with one in six adults in England and 2% of teenagers now being prescribed an antidepressant in a given year.

"Many people take antidepressants because they have been led to believe their depression has a biochemical cause, but this new research suggests this belief is not grounded in evidence."

The umbrella review aimed to capture all relevant studies that have been published in the most important fields of research on serotonin and depression. The studies included in the review involved tens of thousands of participants.

Research that compared levels of serotonin and its breakdown products in the blood or brain fluids did not find a difference between people diagnosed with depression and healthy control (comparison) participants.

Research on serotonin receptors and the serotonin transporter, the protein targeted by most antidepressants, found weak and inconsistent evidence suggestive of higher levels of serotonin activity in people with depression. However, the researchers say the findings are likely explained by the use of antidepressants among people diagnosed with depression, since such effects were not reliably ruled out.

The authors also looked at studies where serotonin levels were artificially lowered in hundreds of people by depriving their diets of the amino acid required to make serotonin. These studies have been cited as demonstrating that a serotonin deficiency is linked to depression. A meta-analysis conducted in 2007 and a sample of recent studies found that lowering serotonin in this way did not produce depression in hundreds of healthy volunteers, however. There was very weak evidence in a small subgroup of people with a family history of depression, but this only involved 75 participants, and more recent evidence was inconclusive.

Very large studies involving tens of thousands of patients looked at gene variation, including the gene for the serotonin transporter. They found no difference in these genes between people with depression and healthy controls. These studies also looked at the effects of stressful life events and found that these exerted a strong effect on people's risk of becoming depressed -- the more stressful life events a person had experienced, the more likely they were to be depressed. A famous early study found a relationship between stressful events, the type of serotonin transporter gene a person had and the chance of depression. But larger, more comprehensive studies suggest this was a false finding.

These findings together led the authors to conclude that there is "no support for the hypothesis that depression is caused by lowered serotonin activity or concentrations."

The researchers say their findings are important as studies show that as many as 85-90% of the public believes that depression is caused by low serotonin or a chemical imbalance. A growing number of scientists and professional bodies are recognising the chemical imbalance framing as an over-simplification. There is also evidence that believing that low mood is caused by a chemical imbalance leads people to have a pessimistic outlook on the likelihood of recovery, and the possibility of managing moods without medical help. This is important because most people will meet criteria for anxiety or depression at some point in their lives.

The authors also found evidence from a large meta-analysis that people who used antidepressants had lower levels of serotonin in their blood. They concluded that some evidence was consistent with the possibility that long-term antidepressant use reduces serotonin concentrations. The researchers say this may imply that the increase in serotonin that some antidepressants produce in the short term could lead to compensatory changes in the brain that produce the opposite effect in the long term.

While the study did not review the efficacy of antidepressants, the authors encourage further research and advice into treatments that might focus instead on managing stressful or traumatic events in people's lives, such as with psychotherapy, alongside other practices such as exercise or mindfulness, or addressing underlying contributors such as poverty, stress and loneliness.

Professor Moncrieff said: "Our view is that patients should not be told that depression is caused by low serotonin or by a chemical imbalance, and they should not be led to believe that antidepressants work by targeting these unproven abnormalities. We do not understand what antidepressants are doing to the brain exactly, and giving people this sort of misinformation prevents them from making an informed decision about whether to take antidepressants or not."

Co-author Dr Mark Horowitz, a training psychiatrist and Clinical Research Fellow in Psychiatry at UCL and NELFT, said: "I had been taught that depression was caused by low serotonin in my psychiatry training and had even taught this to students in my own lectures. Being involved in this research was eye-opening and feels like everything I thought I knew has been flipped upside down.

"One interesting aspect in the studies we examined was how strong an effect adverse life events played in depression, suggesting low mood is a response to people's lives and cannot be boiled down to a simple chemical equation."

Professor Moncrieff added: "Thousands of people suffer from side effects of antidepressants, including the severe withdrawal effects that can occur when people try to stop them, yet prescription rates continue to rise. We believe this situation has been driven partly by the false belief that depression is due to a chemical imbalance. It is high time to inform the public that this belief is not grounded in science."

The researchers caution that anyone considering withdrawing from antidepressants should seek the advice of a health professional, given the risk of adverse effects following withdrawal. Professor Moncrieff and Dr Horowitz are conducting ongoing research into how best to gradually stop taking antidepressants.

- Mental Health

- Disorders and Syndromes

- Intelligence

- Neurotransmitter

- Methamphetamine

- Bipolar disorder

- Psychometrics

- Clinical depression

- Confirmation bias

Story Source:

Materials provided by University College London . Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Journal Reference :

- Joanna Moncrieff, Ruth E. Cooper, Tom Stockmann, Simone Amendola, Michael P. Hengartner, Mark A. Horowitz. The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence . Molecular Psychiatry , 2022; DOI: 10.1038/s41380-022-01661-0

Cite This Page :

Explore More

- Mice Given Mouse-Rat Brains Can Smell Again

- New Circuit Boards Can Be Repeatedly Recycled

- Collisions of Neutron Stars and Black Holes

- Advance in Heart Regenerative Therapy

- Bioluminescence in Animals 540 Million Years Ago

- Profound Link Between Diet and Brain Health

- Loneliness Runs Deep Among Parents

- Food in Sight? The Liver Is Ready!

- Acid Reflux Drugs and Risk of Migraine

- Do Cells Have a Hidden Communication System?

Trending Topics

Strange & offbeat.

Depression is probably not caused by a chemical imbalance in the brain – new study

Senior Clinical Lecturer, Critical and Social Psychiatry, UCL

Clinical Research Fellow in Psychiatry, UCL

Disclosure statement

Joanna Moncrieff is a co-investigator on a National Institute of Health Research funded study exploring methods of antidepressant discontinuation. She is co-chair person of the Critical Psychiatry Network, an informal and unfunded group of psychiatrists and an unpaid board member of the voluntary group, the Council for Evidence-based Psychiatry.

Mark Horowitz is co-founder of a company aiming to help people safely stop unnecessary antidepressants in Canada. He is an (unpaid) associate of the International Institute of Psychiatric Drug Withdrawal (IIPDW) and a member of the Critical Psychiatry Network.

University College London provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

- Bahasa Indonesia

For three decades, people have been deluged with information suggesting that depression is caused by a “chemical imbalance” in the brain – namely an imbalance of a brain chemical called serotonin. However, our latest research review shows that the evidence does not support it.

You can listen to more articles from The Conversation, narrated by Noa, here .

Although first proposed in the 1960s , the serotonin theory of depression started to be widely promoted by the pharmaceutical industry in the 1990s in association with its efforts to market a new range of antidepressants, known as selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors or SSRIs. The idea was also endorsed by official institutions such as the American Psychiatric Association, which still tells the public that “differences in certain chemicals in the brain may contribute to symptoms of depression”.

Countless doctors have repeated the message all over the world, in their private surgeries and in the media. People accepted what they were told. And many started taking antidepressants because they believed they had something wrong with their brain that required an antidepressant to put right. In the period of this marketing push, antidepressant use climbed dramatically, and they are now prescribed to one in six of the adult population in England , for example.

For a long time, certain academics , including some leading psychiatrists , have suggested that there is no satisfactory evidence to support the idea that depression is a result of abnormally low or inactive serotonin. Others continue to endorse the theory . Until now, however, there has been no comprehensive review of the research on serotonin and depression that could enable firm conclusions either way.

At first sight, the fact that SSRI-type antidepressants act on the serotonin system appears to support the serotonin theory of depression. SSRIs temporarily increase the availability of serotonin in the brain, but this does not necessarily imply that depression is caused by the opposite of this effect.

There are other explanations for antidepressants’ effects. In fact, drug trials show that antidepressants are barely distinguishable from a placebo (dummy pill) when it comes to treating depression. Also, antidepressants appear to have a generalised emotion-numbing effect which may influence people’s moods, although we do not know how this effect is produced or much about it.

First comprehensive review

There has been extensive research on the serotonin system since the 1990s, but it has not been collected systematically before. We conducted an “umbrella” review that involved systematically identifying and collating existing overviews of the evidence from each of the main areas of research into serotonin and depression. Although there have been systematic reviews of individual areas in the past, none have combined the evidence from all the different areas taking this approach.

One area of research we included was research comparing levels of serotonin and its breakdown products in the blood or brain fluid. Overall, this research did not show a difference between people with depression and those without depression.

Another area of research has focused on serotonin receptors , which are proteins on the ends of the nerves that serotonin links up with and which can transmit or inhibit serotonin’s effects. Research on the most commonly investigated serotonin receptor suggested either no difference between people with depression and people without depression, or that serotonin activity was actually increased in people with depression – the opposite of the serotonin theory’s prediction.

Research on the serotonin “transporter” , that is the protein which helps to terminate the effect of serotonin (this is the protein that SSRIs act on), also suggested that, if anything, there was increased serotonin activity in people with depression. However, these findings may be explained by the fact that many participants in these studies had used or were currently using antidepressants.

We also looked at research that explored whether depression can be induced in volunteers by artificially lowering levels of serotonin . Two systematic reviews from 2006 and 2007 and a sample of the ten most recent studies (at the time the current research was conducted) found that lowering serotonin did not produce depression in hundreds of healthy volunteers. One of the reviews showed very weak evidence of an effect in a small subgroup of people with a family history of depression, but this only involved 75 participants.

Very large studies involving tens of thousands of patients looked at gene variation, including the gene that has the instructions for making the serotonin transporter . They found no difference in the frequency of varieties of this gene between people with depression and healthy controls.

Although a famous early study found a relationship between the serotonin transporter gene and stressful life events, larger, more comprehensive studies suggest no such relationship exists. Stressful life events in themselves, however, exerted a strong effect on people’s subsequent risk of developing depression.

Some of the studies in our overview that included people who were taking or had previously taken antidepressants showed evidence that antidepressants may actually lower the concentration or activity of serotonin.

Not supported by the evidence

The serotonin theory of depression has been one of the most influential and extensively researched biological theories of the origins of depression. Our study shows that this view is not supported by scientific evidence. It also calls into question the basis for the use of antidepressants.

Most antidepressants now in use are presumed to act via their effects on serotonin. Some also affect the brain chemical noradrenaline. But experts agree that the evidence for the involvement of noradrenaline in depression is weaker than that for serotonin .

There is no other accepted pharmacological mechanism for how antidepressants might affect depression. If antidepressants exert their effects as placebos, or by numbing emotions, then it is not clear that they do more good than harm.

Although viewing depression as a biological disorder may seem like it would reduce stigma, in fact, research has shown the opposite , and also that people who believe their own depression is due to a chemical imbalance are more pessimistic about their chances of recovery.

It is important that people know that the idea that depression results from a “chemical imbalance” is hypothetical. And we do not understand what temporarily elevating serotonin or other biochemical changes produced by antidepressants do to the brain. We conclude that it is impossible to say that taking SSRI antidepressants is worthwhile, or even completely safe.

If you’re taking antidepressants, it’s very important you don’t stop doing so without speaking to your doctor first. But people need all this information to make informed decisions about whether or not to take these drugs.

- SSRI antidepressants

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Regional Engagement Officer - Shepparton

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Deputy Social Media Producer

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Systematic Review

- Open access

- Published: 20 July 2022

The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence

- Joanna Moncrieff 1 , 2 ,

- Ruth E. Cooper 3 ,

- Tom Stockmann 4 ,

- Simone Amendola 5 ,

- Michael P. Hengartner 6 &

- Mark A. Horowitz 1 , 2

Molecular Psychiatry volume 28 , pages 3243–3256 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

1.26m Accesses

233 Citations

9425 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Diagnostic markers

The serotonin hypothesis of depression is still influential. We aimed to synthesise and evaluate evidence on whether depression is associated with lowered serotonin concentration or activity in a systematic umbrella review of the principal relevant areas of research. PubMed, EMBASE and PsycINFO were searched using terms appropriate to each area of research, from their inception until December 2020. Systematic reviews, meta-analyses and large data-set analyses in the following areas were identified: serotonin and serotonin metabolite, 5-HIAA, concentrations in body fluids; serotonin 5-HT 1A receptor binding; serotonin transporter (SERT) levels measured by imaging or at post-mortem; tryptophan depletion studies; SERT gene associations and SERT gene-environment interactions. Studies of depression associated with physical conditions and specific subtypes of depression (e.g. bipolar depression) were excluded. Two independent reviewers extracted the data and assessed the quality of included studies using the AMSTAR-2, an adapted AMSTAR-2, or the STREGA for a large genetic study. The certainty of study results was assessed using a modified version of the GRADE. We did not synthesise results of individual meta-analyses because they included overlapping studies. The review was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42020207203). 17 studies were included: 12 systematic reviews and meta-analyses, 1 collaborative meta-analysis, 1 meta-analysis of large cohort studies, 1 systematic review and narrative synthesis, 1 genetic association study and 1 umbrella review. Quality of reviews was variable with some genetic studies of high quality. Two meta-analyses of overlapping studies examining the serotonin metabolite, 5-HIAA, showed no association with depression (largest n = 1002). One meta-analysis of cohort studies of plasma serotonin showed no relationship with depression, and evidence that lowered serotonin concentration was associated with antidepressant use ( n = 1869). Two meta-analyses of overlapping studies examining the 5-HT 1A receptor (largest n = 561), and three meta-analyses of overlapping studies examining SERT binding (largest n = 1845) showed weak and inconsistent evidence of reduced binding in some areas, which would be consistent with increased synaptic availability of serotonin in people with depression, if this was the original, causal abnormaly. However, effects of prior antidepressant use were not reliably excluded. One meta-analysis of tryptophan depletion studies found no effect in most healthy volunteers ( n = 566), but weak evidence of an effect in those with a family history of depression ( n = 75). Another systematic review ( n = 342) and a sample of ten subsequent studies ( n = 407) found no effect in volunteers. No systematic review of tryptophan depletion studies has been performed since 2007. The two largest and highest quality studies of the SERT gene, one genetic association study ( n = 115,257) and one collaborative meta-analysis ( n = 43,165), revealed no evidence of an association with depression, or of an interaction between genotype, stress and depression. The main areas of serotonin research provide no consistent evidence of there being an association between serotonin and depression, and no support for the hypothesis that depression is caused by lowered serotonin activity or concentrations. Some evidence was consistent with the possibility that long-term antidepressant use reduces serotonin concentration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Genetic contributions to brain serotonin transporter levels in healthy adults

The kynurenine pathway in major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of 101 studies

The complex clinical response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in depression: a network perspective

Introduction.

The idea that depression is the result of abnormalities in brain chemicals, particularly serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine or 5-HT), has been influential for decades, and provides an important justification for the use of antidepressants. A link between lowered serotonin and depression was first suggested in the 1960s [ 1 ], and widely publicised from the 1990s with the advent of the Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants [ 2 , 3 , 4 ]. Although it has been questioned more recently [ 5 , 6 ], the serotonin theory of depression remains influential, with principal English language textbooks still giving it qualified support [ 7 , 8 ], leading researchers endorsing it [ 9 , 10 , 11 ], and much empirical research based on it [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. Surveys suggest that 80% or more of the general public now believe it is established that depression is caused by a ‘chemical imbalance’ [ 15 , 16 ]. Many general practitioners also subscribe to this view [ 17 ] and popular websites commonly cite the theory [ 18 ].

It is often assumed that the effects of antidepressants demonstrate that depression must be at least partially caused by a brain-based chemical abnormality, and that the apparent efficacy of SSRIs shows that serotonin is implicated. Other explanations for the effects of antidepressants have been put forward, however, including the idea that they work via an amplified placebo effect or through their ability to restrict or blunt emotions in general [ 19 , 20 ].

Despite the fact that the serotonin theory of depression has been so influential, no comprehensive review has yet synthesised the relevant evidence. We conducted an ‘umbrella’ review of the principal areas of relevant research, following the model of a similar review examining prospective biomarkers of major depressive disorder [ 21 ]. We sought to establish whether the current evidence supports a role for serotonin in the aetiology of depression, and specifically whether depression is associated with indications of lowered serotonin concentrations or activity.

Search strategy and selection criteria

The present umbrella review was reported in accordance with the 2009 PRISMA statement [ 22 ]. The protocol was registered with PROSPERO in December 2020 (registration number CRD42020207203) ( https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=207203 ). This was subsequently updated to reflect our decision to modify the quality rating system for some studies to more appropriately appraise their quality, and to include a modified GRADE to assess the overall certainty of the findings in each category of the umbrella review.

In order to cover the different areas and to manage the large volume of research that has been conducted on the serotonin system, we conducted an ‘umbrella’ review. Umbrella reviews survey existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses relevant to a research question and represent one of the highest levels of evidence synthesis available [ 23 ]. Although they are traditionally restricted to systematic reviews and meta-analyses, we aimed to identify the best evidence available. Therefore, we also included some large studies that combined data from individual studies but did not employ conventional systematic review methods, and one large genetic study. The latter used nationwide databases to capture more individuals than entire meta-analyses, so is likely to provide even more reliable evidence than syntheses of individual studies.

We first conducted a scoping review to identify areas of research consistently held to provide support for the serotonin hypothesis of depression. Six areas were identified, addressing the following questions: (1) Serotonin and the serotonin metabolite 5-HIAA–whether there are lower levels of serotonin and 5-HIAA in body fluids in depression; (2) Receptors - whether serotonin receptor levels are altered in people with depression; (3) The serotonin transporter (SERT) - whether there are higher levels of the serotonin transporter in people with depression (which would lower synaptic levels of serotonin); (4) Depletion studies - whether tryptophan depletion (which lowers available serotonin) can induce depression; (5) SERT gene – whether there are higher levels of the serotonin transporter gene in people with depression; (6) Whether there is an interaction between the SERT gene and stress in depression.

We searched for systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and large database studies in these six areas in PubMed, EMBASE and PsycINFO using the Healthcare Databases Advanced Search tool provided by Health Education England and NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence). Searches were conducted until December 2020.

We used the following terms in all searches: (depress* OR affective OR mood) AND (systematic OR meta-analysis), and limited searches to title and abstract, since not doing so produced numerous irrelevant hits. In addition, we used terms specific to each area of research (full details are provided in Table S1 , Supplement). We also searched citations and consulted with experts.

Inclusion criteria were designed to identify the best available evidence in each research area and consisted of:

Research synthesis including systematic reviews, meta-analysis, umbrella reviews, individual patient meta-analysis and large dataset analysis.

Studies that involve people with depressive disorders or, for experimental studies (tryptophan depletion), those in which mood symptoms are measured as an outcome.

Studies of experimental procedures (tryptophan depletion) involving a sham or control condition.

Studies published in full in peer reviewed literature.

Where more than five systematic reviews or large analyses exist, the most recent five are included.

Exclusion criteria consisted of:

Animal studies.

Studies exclusively concerned with depression in physical conditions (e.g. post stroke or Parkinson’s disease) or exclusively focusing on specific subtypes of depression such as postpartum depression, depression in children, or depression in bipolar disorder.

No language or date restrictions were applied. In areas in which no systematic review or meta-analysis had been done within the last 10 years, we also selected the ten most recent studies at the time of searching (December 2020) for illustration of more recent findings. We performed this search using the same search string for this domain, without restricting it to systematic reviews and meta-analyses.

Data analysis

Each member of the team was allocated one to three domains of serotonin research to search and screen for eligible studies using abstract and full text review. In case of uncertainty, the entire team discussed eligibility to reach consensus.

For included studies, data were extracted by two reviewers working independently, and disagreement was resolved by consensus. Authors of papers were contacted for clarification when data was missing or unclear.

We extracted summary effects, confidence intervals and measures of statistical significance where these were reported, and, where relevant, we extracted data on heterogeneity. For summary effects in the non-genetic studies, preference was given to the extraction and reporting of effect sizes. Mean differences were converted to effect sizes where appropriate data were available.

We did not perform a meta-analysis of the individual meta-analyses in each area because they included overlapping studies [ 24 ]. All extracted data is presented in Table 1 . Sensitivity analyses were reported where they had substantial bearing on interpretation of findings.

The quality rating of systematic reviews and meta-analyses was assessed using AMSTAR-2 (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews) [ 25 ]. For two studies that did not employ conventional systematic review methods [ 26 , 27 ] we used a modified version of the AMSTAR-2 (see Table S3 ). For the genetic association study based on a large database analysis we used the STREGA assessment (STrengthening the REporting of Genetic Association Studies) (Table S4 ) [ 28 ]. Each study was rated independently by at least two authors. We report ratings of individual items on the relevant measure, and the percentage of items that were adequately addressed by each study (Table 1 , with further detail in Tables S3 and S4 ).

Alongside quality ratings, two team members (JM, MAH) rated the certainty of the results of each study using a modified version of the GRADE guidelines [ 29 ]. Following the approach of Kennis et al. [ 21 ], we devised six criteria relevant to the included studies: whether a unified analysis was conducted on original data; whether confounding by antidepressant use was adequately addressed; whether outcomes were pre-specified; whether results were consistent or heterogeneity was adequately addressed if present; whether there was a likelihood of publication bias; and sample size. The importance of confounding by effects of current or past antidepressant use has been highlighted in several studies [ 30 , 31 ]. The results of each study were scored 1 or 0 according to whether they fulfilled each criteria, and based on these ratings an overall judgement was made about the certainty of evidence across studies in each of the six areas of research examined. The certainty of each study was based on an algorithm that prioritised sample size and uniform analysis using original data (explained more fully in the supplementary material), following suggestions that these are the key aspects of reliability [ 27 , 32 ]. An assessment of the overall certainty of each domain of research examining the role of serotonin was determined by consensus of at least two authors and a direction of effect indicated.

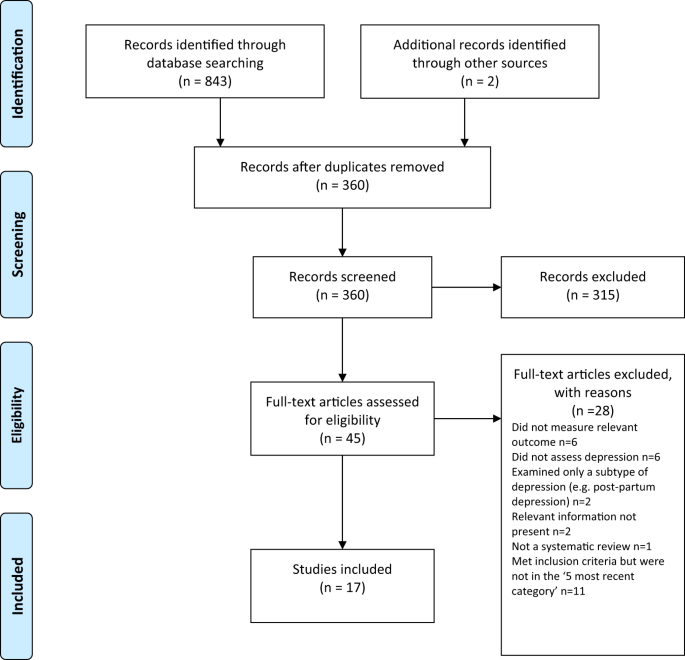

Search results and quality rating

Searching identified 361 publications across the 6 different areas of research, among which seventeen studies fulfilled inclusion criteria (see Fig. 1 and Table S1 for details of the selection process). Included studies, their characteristics and results are shown in Table 1 . As no systematic review or meta-analysis had been performed within the last 10 years on serotonin depletion, we also identified the 10 latest studies for illustration of more recent research findings (Table 2 ).

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagramme.

Quality ratings are summarised in Table 1 and reported in detail in Tables S2 – S3 . The majority (11/17) of systematic reviews and meta-analyses satisfied less than 50% of criteria. Only 31% adequately assessed risk of bias in individual studies (a further 44% partially assessed this), and only 50% adequately accounted for risk of bias when interpreting the results of the review. One collaborative meta-analysis of genetic studies was considered to be of high quality due to the inclusion of several measures to ensure consistency and reliability [ 27 ]. The large genetic analysis of the effect of SERT polymorphisms on depression, satisfied 88% of the STREGA quality criteria [ 32 ].

Serotonin and 5-HIAA

Serotonin can be measured in blood, plasma, urine and CSF, but it is rapidly metabolised to 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA). CSF is thought to be the ideal resource for the study of biomarkers of putative brain diseases, since it is in contact with brain interstitial fluid [ 33 ]. However, collecting CSF samples is invasive and carries some risk, hence large-scale studies are scarce.

Three studies fulfilled inclusion criteria (Table 1 ). One meta-analysis of three large observational cohort studies of post-menopausal women, revealed lower levels of plasma 5-HT in women with depression, which did not, however, reach statistical significance of p < 0.05 after adjusting for multiple comparisons. Sensitivity analyses revealed that antidepressants were strongly associated with lower serotonin levels independently of depression.

Two meta-analyses of a total of 19 studies of 5-HIAA in CSF (seven studies were included in both) found no evidence of an association between 5-HIAA concentrations and depression.

Fourteen different serotonin receptors have been identified, with most research on depression focusing on the 5-HT 1A receptor [ 11 , 34 ]. Since the functions of other 5-HT receptors and their relationship to depression have not been well characterised, we restricted our analysis to data on 5-HT 1A receptors [ 11 , 34 ]. 5-HT 1A receptors, known as auto-receptors, inhibit the release of serotonin pre-synaptically [ 35 ], therefore, if depression is the result of reduced serotonin activity caused by abnormalities in the 5-HT 1A receptor, people with depression would be expected to show increased activity of 5-HT 1A receptors compared to those without [ 36 ].

Two meta-analyses satisfied inclusion criteria, involving five of the same studies [ 37 , 38 ] (see Table 1 ). The majority of results across the two analyses suggested either no difference in 5-HT 1A receptors between people with depression and controls, or a lower level of these inhibitory receptors, which would imply higher concentrations or activity of serotonin in people with depression. Both meta-analyses were based on studies that predominantly involved patients who were taking or had recently taken (within 1–3 weeks of scanning) antidepressants or other types of psychiatric medication, and both sets of authors commented on the possible influence of prior or current medication on findings. In addition, one analysis was of very low quality [ 37 ], including not reporting on the numbers involved in each analysis and using one-sided p-values, and one was strongly influenced by three studies and publication bias was present [ 38 ].

The serotonin transporter (SERT)

The serotonin transporter protein (SERT) transports serotonin out of the synapse, thereby lowering the availability of serotonin in the synapse [ 39 , 40 ]. Animals with an inactivated gene for SERT have higher levels of extra-cellular serotonin in the brain than normal [ 41 , 42 , 43 ] and SSRIs are thought to work by inhibiting the action of SERT, and thus increasing levels of serotonin in the synaptic cleft [ 44 ]. Although changes in SERT may be a marker for other abnormalities, if depression is caused by low serotonin availability or activity, and if SERT is the origin of that deficit, then the amount or activity of SERT would be expected to be higher in people with depression compared to those without [ 40 ]. SERT binding potential is an index of the concentration of the serotonin transporter protein and SERT concentrations can also be measured post-mortem.

Three overlapping meta-analyses based on a total of 40 individual studies fulfilled inclusion criteria (See Table 1 ) [ 37 , 39 , 45 ]. Overall, the data indicated possible reductions in SERT binding in some brain areas, although areas in which effects were detected were not consistent across the reviews. In addition, effects of antidepressants and other medication cannot be ruled out, since most included studies mainly or exclusively involved people who had a history of taking antidepressants or other psychiatric medications. Only one meta-analysis tested effects of antidepressants, and although results were not influenced by the percentage of drug-naïve patients in each study, numbers were small so it is unlikely that medication-related effects would have been reliably detected [ 45 ]. All three reviews cited evidence from animal studies that antidepressant treatment reduces SERT [ 46 , 47 , 48 ]. None of the analyses corrected for multiple testing, and one review was of very low quality [ 37 ]. If the results do represent a positive finding that is independent of medication, they would suggest that depression is associated with higher concentrations or activity of serotonin.

Depletion studies

Tryptophan depletion using dietary means or chemicals, such as parachlorophenylalanine (PCPA), is thought to reduce serotonin levels. Since PCPA is potentially toxic, reversible tryptophan depletion using an amino acid drink that lacks tryptophan is the most commonly used method and is thought to affect serotonin within 5–7 h of ingestion. Questions remain, however, about whether either method reliably reduces brain serotonin, and about other effects including changes in brain nitrous oxide, cerebrovascular changes, reduced BDNF and amino acid imbalances that may be produced by the manipulations and might explain observed effects independent of possible changes in serotonin activity [ 49 ].

One meta-analysis and one systematic review fulfilled inclusion criteria (see Table 1 ). Data from studies involving volunteers mostly showed no effect, including a meta-analysis of parallel group studies [ 50 ]. In a small meta-analysis of within-subject studies involving 75 people with a positive family history, a minor effect was found, with people given the active depletion showing a larger decrease in mood than those who had a sham procedure [ 50 ]. Across both reviews, studies involving people diagnosed with depression showed slightly greater mood reduction following tryptophan depletion than sham treatment overall, but most participants had taken or were taking antidepressants and participant numbers were small [ 50 , 51 ].

Since these research syntheses were conducted more than 10 years ago, we searched for a systematic sample of ten recently published studies (Table 2 ). Eight studies conducted with healthy volunteers showed no effects of tryptophan depletion on mood, including the only two parallel group studies. One study presented effects in people with and without a family history of depression, and no differences were apparent in either group [ 52 ]. Two cross-over studies involving people with depression and current or recent use of antidepressants showed no convincing effects of a depletion drink [ 53 , 54 ], although one study is reported as positive mainly due to finding an improvement in mood in the group given the sham drink [ 54 ].

SERT gene and gene-stress interactions

A possible link between depression and the repeat length polymorphism in the promoter region of the SERT gene (5-HTTLPR), specifically the presence of the short repeats version, which causes lower SERT mRNA expression, has been proposed [ 55 ]. Interestingly, lower levels of SERT would produce higher levels of synaptic serotonin. However, more recently, this hypothesis has been superseded by a focus on the interaction effect between this polymorphism, depression and stress, with the idea that the short version of the polymorphism may only give rise to depression in the presence of stressful life events [ 55 , 56 ]. Unlike other areas of serotonin research, numerous systematic reviews and meta-analyses of genetic studies have been conducted, and most recently a very large analysis based on a sample from two genetic databanks. Details of the five most recent studies that have addressed the association between the SERT gene and depression, and the interaction effect are detailed in Table 1 .

Although some earlier meta-analyses of case-control studies showed a statistically significant association between the 5-HTTLPR and depression in some ethnic groups [ 57 , 58 ], two recent large, high quality studies did not find an association between the SERT gene polymorphism and depression [ 27 , 32 ]. These two studies consist of by far the largest and most comprehensive study to date [ 32 ] and a high-quality meta-analysis that involved a consistent re-analysis of primary data across all conducted studies, including previously unpublished data, and other comprehensive quality checks [ 27 , 59 ] (see Table 1 ).

Similarly, early studies based on tens of thousands of participants suggested a statistically significant interaction between the SERT gene, forms of stress or maltreatment and depression [ 60 , 61 , 62 ], with a small odds ratio in the only study that reported this (1.18, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.28) [ 62 ]. However, the two recent large, high-quality studies did not find an interaction between the SERT gene and stress in depression (Border et al [ 32 ] and Culverhouse et al.) [ 27 ] (see Table 1 ).

Overall results

Table 3 presents the modified GRADE ratings for each study and the overall rating of the strength of evidence in each area. Areas of research that provided moderate or high certainty of evidence such as the studies of plasma serotonin and metabolites and the genetic and gene-stress interaction studies all showed no association between markers of serotonin activity and depression. Some other areas suggested findings consistent with increased serotonin activity, but evidence was of very low certainty, mainly due to small sample sizes and possible residual confounding by current or past antidepressant use. One area - the tryptophan depletion studies - showed very low certainty evidence of lowered serotonin activity or availability in a subgroup of volunteers with a family history of depression. This evidence was considered very low certainty as it derived from a subgroup of within-subject studies, numbers were small, and there was no information on medication use, which may have influenced results. Subsequent research has not confirmed an effect with numerous negative studies in volunteers.

Our comprehensive review of the major strands of research on serotonin shows there is no convincing evidence that depression is associated with, or caused by, lower serotonin concentrations or activity. Most studies found no evidence of reduced serotonin activity in people with depression compared to people without, and methods to reduce serotonin availability using tryptophan depletion do not consistently lower mood in volunteers. High quality, well-powered genetic studies effectively exclude an association between genotypes related to the serotonin system and depression, including a proposed interaction with stress. Weak evidence from some studies of serotonin 5-HT 1A receptors and levels of SERT points towards a possible association between increased serotonin activity and depression. However, these results are likely to be influenced by prior use of antidepressants and its effects on the serotonin system [ 30 , 31 ]. The effects of tryptophan depletion in some cross-over studies involving people with depression may also be mediated by antidepressants, although these are not consistently found [ 63 ].

The chemical imbalance theory of depression is still put forward by professionals [ 17 ], and the serotonin theory, in particular, has formed the basis of a considerable research effort over the last few decades [ 14 ]. The general public widely believes that depression has been convincingly demonstrated to be the result of serotonin or other chemical abnormalities [ 15 , 16 ], and this belief shapes how people understand their moods, leading to a pessimistic outlook on the outcome of depression and negative expectancies about the possibility of self-regulation of mood [ 64 , 65 , 66 ]. The idea that depression is the result of a chemical imbalance also influences decisions about whether to take or continue antidepressant medication and may discourage people from discontinuing treatment, potentially leading to lifelong dependence on these drugs [ 67 , 68 ].

As with all research synthesis, the findings of this umbrella review are dependent on the quality of the included studies, and susceptible to their limitations. Most of the included studies were rated as low quality on the AMSTAR-2, but the GRADE approach suggested some findings were reasonably robust. Most of the non-genetic studies did not reliably exclude the potential effects of previous antidepressant use and were based on relatively small numbers of participants. The genetic studies, in particular, illustrate the importance of methodological rigour and sample size. Whereas some earlier, lower quality, mostly smaller studies produced marginally positive findings, these were not confirmed in better-conducted, larger and more recent studies [ 27 , 32 ]. The identification of depression and assessment of confounders and interaction effects were limited by the data available in the original studies on which the included reviews and meta-analyses were based. Common methods such as the categorisation of continuous measures and application of linear models to non-linear data may have led to over-estimation or under-estimation of effects [ 69 , 70 ], including the interaction between stress and the SERT gene. The latest systematic review of tryptophan depletion studies was conducted in 2007, and there has been considerable research produced since then. Hence, we provided a snapshot of the most recent evidence at the time of writing, but this area requires an up to date, comprehensive data synthesis. However, the recent studies were consistent with the earlier meta-analysis with little evidence for an effect of tryptophan depletion on mood.

Although umbrella reviews typically restrict themselves to systematic reviews and meta-analyses, we aimed to provide the most comprehensive possible overview. Therefore, we chose to include meta-analyses that did not involve a systematic review and a large genetic association study on the premise that these studies contribute important data on the question of whether the serotonin hypothesis of depression is supported. As a result, the AMSTAR-2 quality rating scale, designed to evaluate the quality of conventional systematic reviews, was not easily applicable to all studies and had to be modified or replaced in some cases.

One study in this review found that antidepressant use was associated with a reduction of plasma serotonin [ 26 ], and it is possible that the evidence for reductions in SERT density and 5-HT 1A receptors in some of the included imaging study reviews may reflect compensatory adaptations to serotonin-lowering effects of prior antidepressant use. Authors of one meta-analysis also highlighted evidence of 5-HIAA levels being reduced after long-term antidepressant treatment [ 71 ]. These findings suggest that in the long-term antidepressants might produce compensatory changes [ 72 ] that are opposite to their acute effects [ 73 , 74 ]. Lowered serotonin availability has also been demonstrated in animal studies following prolonged antidepressant administration [ 75 ]. Further research is required to clarify the effects of different drugs on neurochemical systems, including the serotonin system, especially during and after long-term use, as well as the physical and psychological consequences of such effects.

This review suggests that the huge research effort based on the serotonin hypothesis has not produced convincing evidence of a biochemical basis to depression. This is consistent with research on many other biological markers [ 21 ]. We suggest it is time to acknowledge that the serotonin theory of depression is not empirically substantiated.

Data availability

All extracted data is available in the paper and supplementary materials. Further information about the decision-making for each rating for categories of the AMSTAR-2 and STREGA are available on request.

Coppen A. The biochemistry of affective disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 1967;113:1237–64.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association. What Is Psychiatry? 2021. https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/what-is-psychiatry-menu .

GlaxoSmithKline. Paxil XR. 2009. www.Paxilcr.com (site no longer available). Last accessed 27th Jan 2009.

Eli Lilly. Prozac - How it works. 2006. www.prozac.com/how_prozac/how_it_works.jsp?reqNavId=2.2 . (site no longer available). Last accessed 10th Feb 2006.

Healy D. Serotonin and depression. BMJ: Br Med J. 2015;350:h1771.

Google Scholar

Pies R. Psychiatry’s New Brain-Mind and the Legend of the “Chemical Imbalance.” 2011. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/psychiatrys-new-brain-mind-and-legend-chemical-imbalance . Accessed March 2, 2021.

Geddes JR, Andreasen NC, Goodwin GM. New Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2020.

Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan & Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 10th Editi. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (LWW); 2017.

Cowen PJ, Browning M. What has serotonin to do with depression? World Psychiatry. 2015;14:158–60.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Harmer CJ, Duman RS, Cowen PJ. How do antidepressants work? New perspectives for refining future treatment approaches. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4:409–18.

Yohn CN, Gergues MM, Samuels BA. The role of 5-HT receptors in depression. Mol Brain. 2017;10:28.

Hahn A, Haeusler D, Kraus C, Höflich AS, Kranz GS, Baldinger P, et al. Attenuated serotonin transporter association between dorsal raphe and ventral striatum in major depression. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35:3857–66.

Amidfar M, Colic L, Kim MWAY-K. Biomarkers of major depression related to serotonin receptors. Curr Psychiatry Rev. 2018;14:239–44.

CAS Google Scholar

Albert PR, Benkelfat C, Descarries L. The neurobiology of depression—revisiting the serotonin hypothesis. I. Cellular and molecular mechanisms. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2012;367:2378–81.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Pilkington PD, Reavley NJ, Jorm AF. The Australian public’s beliefs about the causes of depression: associated factors and changes over 16 years. J Affect Disord. 2013;150:356–62.

PubMed Google Scholar

Pescosolido BA, Martin JK, Long JS, Medina TR, Phelan JC, Link BG. A disease like any other? A decade of change in public reactions to schizophrenia, depression, and alcohol dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1321–30.

Read J, Renton J, Harrop C, Geekie J, Dowrick C. A survey of UK general practitioners about depression, antidepressants and withdrawal: implementing the 2019 Public Health England report. Therapeutic Advances in. Psychopharmacology. 2020;10:204512532095012.

Demasi M, Gøtzsche PC. Presentation of benefits and harms of antidepressants on websites: A cross-sectional study. Int J Risk Saf Med. 2020;31:53–65.

Jakobsen JC, Gluud C, Kirsch I. Should antidepressants be used for major depressive disorder? BMJ Evidence-Based. Medicine. 2020;25:130–130.

Moncrieff J, Cohen D. Do antidepressants cure or create abnormal brain states? PLoS Med. 2006;3:e240.

Kennis M, Gerritsen L, van Dalen M, Williams A, Cuijpers P, Bockting C. Prospective biomarkers of major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:321–38.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097.

Fusar-Poli P, Radua J. Ten simple rules for conducting umbrella reviews. Evid Based Ment Health. 2018;21:95–100.

Pollock M, Fernandes RM, Becker LA, Pieper D, Hartling L. Chapter V: Overviews of Reviews. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al., editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.2,. version 6.Cochrane; 2021.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008.

Huang T, Balasubramanian R, Yao Y, Clish CB, Shadyab AH, Liu B, et al. Associations of depression status with plasma levels of candidate lipid and amino acid metabolites: a meta-analysis of individual data from three independent samples of US postmenopausal women. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-020-00870-9 .

Culverhouse RC, Saccone NL, Horton AC, Ma Y, Anstey KJ, Banaschewski T, et al. Collaborative meta-analysis finds no evidence of a strong interaction between stress and 5-HTTLPR genotype contributing to the development of depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23:133–42.

Little J, Higgins JPT, Ioannidis JPA, Moher D, Gagnon F, von Elm E, et al. STrengthening the REporting of Genetic Association Studies (STREGA)— An Extension of the STROBE Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000022.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Vist GE, Falck-Ytter Y, Schünemann HJ. What is quality of evidence and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ. 2008;336:995–8.

Yoon HS, Hattori K, Ogawa S, Sasayama D, Ota M, Teraishi T, et al. Relationships of cerebrospinal fluid monoamine metabolite levels with clinical variables in major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78:e947–56.

Kugaya A, Seneca NM, Snyder PJ, Williams SA, Malison RT, Baldwin RM, et al. Changes in human in vivo serotonin and dopamine transporter availabilities during chronic antidepressant administration. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:413–20.

Border R, Johnson EC, Evans LM, Smolen A, Berley N, Sullivan PF, et al. No support for historical candidate gene or candidate gene-by-interaction hypotheses for major depression across multiple large samples. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176:376–87.

Ogawa S, Tsuchimine S, Kunugi H. Cerebrospinal fluid monoamine metabolite concentrations in depressive disorder: A meta-analysis of historic evidence. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;105:137–46.

Nautiyal KM, Hen R. Serotonin receptors in depression: from A to B. F1000Res. 2017;6:123.

Rojas PS, Neira D, Muñoz M, Lavandero S, Fiedler JL. Serotonin (5‐HT) regulates neurite outgrowth through 5‐HT1A and 5‐HT7 receptors in cultured hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2014;92:1000–9.

Kaufman J, DeLorenzo C, Choudhury S, Parsey RV. The 5-HT1A receptor in Major Depressive Disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;26:397–410.

Nikolaus S, Müller H-W, Hautzel H. Different patterns of 5-HT receptor and transporter dysfunction in neuropsychiatric disorders – a comparative analysis of in vivo imaging findings. Rev Neurosci. 2016;27:27–59.

Wang L, Zhou C, Zhu D, Wang X, Fang L, Zhong J, et al. Serotonin-1A receptor alterations in depression: A meta-analysis of molecular imaging studies. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:1–9.

Kambeitz JP, Howes OD. The serotonin transporter in depression: Meta-analysis of in vivo and post mortem findings and implications for understanding and treating depression. J Affect Disord. 2015;186:358–66.

Meyer JH. Imaging the serotonin transporter during major depressive disorder and antidepressant treatment. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2007;32:86–102.

Mathews TA, Fedele DE, Coppelli FM, Avila AM, Murphy DL, Andrews AM. Gene dose-dependent alterations in extraneuronal serotonin but not dopamine in mice with reduced serotonin transporter expression. J Neurosci Methods. 2004;140:169–81.

Shen H-W, Hagino Y, Kobayashi H, Shinohara-Tanaka K, Ikeda K, Yamamoto H, et al. Regional differences in extracellular dopamine and serotonin assessed by in vivo microdialysis in mice lacking dopamine and/or serotonin transporters. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1790–9.

Hagino Y, Takamatsu Y, Yamamoto H, Iwamura T, Murphy DL, Uhl GR, et al. Effects of MDMA on extracellular dopamine and serotonin levels in mice lacking dopamine and/or serotonin transporters. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2011;9:91–5.

Zhou Z, Zhen J, Karpowich NK, Law CJ, Reith MEA, Wang D-N. Antidepressant specificity of serotonin transporter suggested by three LeuT-SSRI structures. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:652–7.

Gryglewski G, Lanzenberger R, Kranz GS, Cumming P. Meta-analysis of molecular imaging of serotonin transporters in major depression. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34:1096–103.

Benmansour S, Owens WA, Cecchi M, Morilak DA, Frazer A. Serotonin clearance in vivo is altered to a greater extent by antidepressant-induced downregulation of the serotonin transporter than by acute blockade of this transporter. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6766–72.

Benmansour S, Cecchi M, Morilak DA, Gerhardt GA, Javors MA, Gould GG, et al. Effects of chronic antidepressant treatments on serotonin transporter function, density, and mRNA level. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10494–501.

Horschitz S, Hummerich R, Schloss P. Down-regulation of the rat serotonin transporter upon exposure to a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Neuroreport. 2001;12:2181–4.

Young SN. Acute tryptophan depletion in humans: a review of theoretical, practical and ethical aspects. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2013;38:294–305.

Ruhe HG, Mason NS, Schene AH. Mood is indirectly related to serotonin, norepinephrine and dopamine levels in humans: a meta-analysis of monoamine depletion studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12:331–59.

Fusar-Poli P, Allen P, McGuire P, Placentino A, Cortesi M, Perez J. Neuroimaging and electrophysiological studies of the effects of acute tryptophan depletion: A systematic review of the literature. Psychopharmacology. 2006;188:131–43.

Hogenelst K, Schoevers RA, Kema IP, Sweep FCGJ, aan het Rot M. Empathic accuracy and oxytocin after tryptophan depletion in adults at risk for depression. Psychopharmacology. 2016;233:111–20.

Weinstein JJ, Rogers BP, Taylor WD, Boyd BD, Cowan RL, Shelton KM, et al. Effects of acute tryptophan depletion on raphé functional connectivity in depression. Psychiatry Res. 2015;234:164–71.

Moreno FA, Erickson RP, Garriock HA, Gelernter J, Mintz J, Oas-Terpstra J, et al. Association study of genotype by depressive response during tryptophan depletion in subjects recovered from major depression. Mol. Neuropsychiatry. 2015;1:165–74.

Munafò MR. The serotonin transporter gene and depression. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:915–7.

Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Craig IW, Harrington H, et al. Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science 2003;301:386–9.

ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Kiyohara C, Yoshimasu K. Association between major depressive disorder and a functional polymorphism of the 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) transporter gene: A meta-analysis. Psychiatr Genet. 2010;20:49–58.

Oo KZ, Aung YK, Jenkins MA, Win AK. Associations of 5HTTLPR polymorphism with major depressive disorder and alcohol dependence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust N. Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50:842–57.

Culverhouse RC, Bowes L, Breslau N, Nurnberger JI, Burmeister M, Fergusson DM, et al. Protocol for a collaborative meta-analysis of 5-HTTLPR, stress, and depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:1–12.

Karg K, Burmeister M, Shedden K, Sen S. The serotonin transporter promoter variant (5-HTTLPR), stress, and depression meta-analysis revisited. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:444.

Sharpley CF, Palanisamy SKA, Glyde NS, Dillingham PW, Agnew LL. An update on the interaction between the serotonin transporter promoter variant (5-HTTLPR), stress and depression, plus an exploration of non-confirming findings. Behav Brain Res. 2014;273:89–105.

Bleys D, Luyten P, Soenens B, Claes S. Gene-environment interactions between stress and 5-HTTLPR in depression: A meta-analytic update. J Affect Disord. 2018;226:339–45.

Delgado PL. Monoamine depletion studies: implications for antidepressant discontinuation syndrome. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:22–26.

Kemp JJ, Lickel JJ, Deacon BJ. Effects of a chemical imbalance causal explanation on individuals’ perceptions of their depressive symptoms. Behav Res Ther. 2014;56:47–52.

Lebowitz MS, Ahn W-K, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Fixable or fate? Perceptions of the biology of depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2013;81:518.

Zimmermann M, Papa A. Causal explanations of depression and treatment credibility in adults with untreated depression: Examining attribution theory. Psychol Psychother. 2020;93:537–54.

Maund E, Dewar-Haggart R, Williams S, Bowers H, Geraghty AWA, Leydon G, et al. Barriers and facilitators to discontinuing antidepressant use: A systematic review and thematic synthesis. J Affect Disord. 2019;245:38–62.

Eveleigh R, Speckens A, van Weel C, Oude Voshaar R, Lucassen P. Patients’ attitudes to discontinuing not-indicated long-term antidepressant use: barriers and facilitators. Therapeutic Advances in. Psychopharmacology. 2019;9:204512531987234.

Harrell FE Jr. Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic and Ordinal Regression, and Survival Analysis. Springer, Cham; 2015.

Schafer JL, Kang J. Average causal effects from nonrandomized studies: a practical guide and simulated example. Psychol Methods. 2008;13:279–313.

Pech J, Forman J, Kessing LV, Knorr U. Poor evidence for putative abnormalities in cerebrospinal fluid neurotransmitters in patients with depression versus healthy non-psychiatric individuals: A systematic review and meta-analyses of 23 studies. J Affect Disord. 2018;240:6–16.

Fava GA. May antidepressant drugs worsen the conditions they are supposed to treat? The clinical foundations of the oppositional model of tolerance. Therapeutic Adv Psychopharmacol. 2020;10:2045125320970325.

Kitaichi Y, Inoue T, Nakagawa S, Boku S, Kakuta A, Izumi T, et al. Sertraline increases extracellular levels not only of serotonin, but also of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens and striatum of rats. Eur J Pharm. 2010;647:90–6.

Gartside SE, Umbers V, Hajós M, Sharp T. Interaction between a selective 5‐HT1Areceptor antagonist and an SSRI in vivo: effects on 5‐HT cell firing and extracellular 5‐HT. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;115:1064–70.

Bosker FJ, Tanke MAC, Jongsma ME, Cremers TIFH, Jagtman E, Pietersen CY, et al. Biochemical and behavioral effects of long-term citalopram administration and discontinuation in rats: role of serotonin synthesis. Neurochem Int. 2010;57:948–57.

Download references

There was no specific funding for this review. MAH is supported by a Clinical Research Fellowship from North East London NHS Foundation Trust (NELFT). This funder had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Division of Psychiatry, University College London, London, UK

Joanna Moncrieff & Mark A. Horowitz

Research and Development Department, Goodmayes Hospital, North East London NHS Foundation Trust, Essex, UK

Faculty of Education, Health and Human Sciences, University of Greenwich, London, UK

Ruth E. Cooper

Psychiatry-UK, Cornwall, UK

Tom Stockmann

Department of Dynamic and Clinical Psychology, and Health Studies, Faculty of Medicine and Psychology, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

Simone Amendola

Department of Applied Psychology, Zurich University of Applied Sciences, Zurich, Switzerland

Michael P. Hengartner

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

JM conceived the idea for the study. JM, MAH, MPH, TS and SA designed the study. JM, MAH, MPH, TS, and SA screened articles and abstracted data. JM drafted the first version of the manuscript. JM, MAH, MPH, TS, SA, and REC contributed to the manuscript’s revision and interpretation of findings. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Joanna Moncrieff .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author). SA declares no conflicts of interest. MAH reports being co-founder of a company in April 2022, aiming to help people safely stop antidepressants in Canada. MPH reports royalties from Palgrave Macmillan, London, UK for his book published in December, 2021, called “Evidence-biased Antidepressant Prescription.” JM receives royalties for books about psychiatric drugs, reports grants from the National Institute of Health Research outside the submitted work, that she is co-chairperson of the Critical Psychiatry Network (an informal group of psychiatrists) and a board member of the unfunded organisation, the Council for Evidence-based Psychiatry. Both are unpaid positions. TS is co-chairperson of the Critical Psychiatry Network. RC is an unpaid board member of the International Institute for Psychiatric Drug Withdrawal.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary tables, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Moncrieff, J., Cooper, R.E., Stockmann, T. et al. The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence. Mol Psychiatry 28 , 3243–3256 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01661-0

Download citation

Received : 21 June 2021

Revised : 31 May 2022

Accepted : 07 June 2022

Published : 20 July 2022

Issue Date : August 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01661-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

The involvement of serotonin in major depression: nescience in disguise.

- Danilo Arnone

- Catherine J. Harmer

Molecular Psychiatry (2024)

Serotonin effects on human iPSC-derived neural cell functions: from mitochondria to depression

- Iseline Cardon

- Sonja Grobecker

- Christian H. Wetzel

Neither serotonin disorder is at the core of depression nor dopamine at the core of schizophrenia; still these are biologically based mental disorders

- Konstantinos N. Fountoulakis

- Eva Maria Tsapakis

The impact of adult neurogenesis on affective functions: of mice and men

- Mariana Alonso

- Anne-Cécile Petit

- Pierre-Marie Lledo

Biallelic variants identified in 36 Pakistani families and trios with autism spectrum disorder

- Ricardo Harripaul

- John B. Vincent

Scientific Reports (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Alzheimer's disease & dementia

- Arthritis & Rheumatism

- Attention deficit disorders

- Autism spectrum disorders

- Biomedical technology

- Diseases, Conditions, Syndromes

- Endocrinology & Metabolism

- Gastroenterology

- Gerontology & Geriatrics

- Health informatics

- Inflammatory disorders

- Medical economics

- Medical research

- Medications

- Neuroscience

- Obstetrics & gynaecology

- Oncology & Cancer

- Ophthalmology

- Overweight & Obesity

- Parkinson's & Movement disorders

- Psychology & Psychiatry

- Radiology & Imaging

- Sleep disorders

- Sports medicine & Kinesiology

- Vaccination

- Breast cancer

- Cardiovascular disease

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Colon cancer

- Coronary artery disease

- Heart attack

- Heart disease

- High blood pressure

- Kidney disease

- Lung cancer

- Multiple sclerosis

- Myocardial infarction

- Ovarian cancer

- Post traumatic stress disorder

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Schizophrenia

- Skin cancer

- Type 2 diabetes

- Full List »

share this!

July 20, 2022

Depression is probably not caused by a chemical imbalance in the brain, says new study

by Joanna Moncrieff and Mark Horowitz, The Conversation

For three decades, people have been deluged with information suggesting that depression is caused by a "chemical imbalance" in the brain—namely an imbalance of a brain chemical called serotonin. However, our latest research review shows that the evidence does not support it.

Although first proposed in the 1960s , the serotonin theory of depression started to be widely promoted by the pharmaceutical industry in the 1990s in association with its efforts to market a new range of antidepressants, known as selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors or SSRIs. The idea was also endorsed by official institutions such as the American Psychiatric Association, which still tells the public that "differences in certain chemicals in the brain may contribute to symptoms of depression."

Countless doctors have repeated the message all over the world, in their private surgeries and in the media. People accepted what they were told. And many started taking antidepressants because they believed they had something wrong with their brain that required an antidepressant to put right. In the period of this marketing push, antidepressant use climbed dramatically, and they are now prescribed to one in six of the adult population in England , for example.

For a long time, certain academics , including some leading psychiatrists , have suggested that there is no satisfactory evidence to support the idea that depression is a result of abnormally low or inactive serotonin. Others continue to endorse the theory . Until now, however, there has been no comprehensive review of the research on serotonin and depression that could enable firm conclusions either way.

At first sight, the fact that SSRI-type antidepressants act on the serotonin system appears to support the serotonin theory of depression. SSRIs temporarily increase the availability of serotonin in the brain, but this does not necessarily imply that depression is caused by the opposite of this effect.

There are other explanations for antidepressants' effects. In fact, drug trials show that antidepressants are barely distinguishable from a placebo (dummy pill) when it comes to treating depression. Also, antidepressants appear to have a generalized emotion-numbing effect which may influence people's moods, although we do not know how this effect is produced or much about it.

First comprehensive review

There has been extensive research on the serotonin system since the 1990s, but it has not been collected systematically before. We conducted an "umbrella" review that involved systematically identifying and collating existing overviews of the evidence from each of the main areas of research into serotonin and depression. Although there have been systematic reviews of individual areas in the past, none have combined the evidence from all the different areas taking this approach.

One area of research we included was research comparing levels of serotonin and its breakdown products in the blood or brain fluid. Overall, this research did not show a difference between people with depression and those without depression.

Another area of research has focused on serotonin receptors , which are proteins on the ends of the nerves that serotonin links up with and which can transmit or inhibit serotonin's effects. Research on the most commonly investigated serotonin receptor suggested either no difference between people with depression and people without depression, or that serotonin activity was actually increased in people with depression—the opposite of the serotonin theory's prediction.

Research on the serotonin "transporter" , that is the protein which helps to terminate the effect of serotonin (this is the protein that SSRIs act on), also suggested that, if anything, there was increased serotonin activity in people with depression. However, these findings may be explained by the fact that many participants in these studies had used or were currently using antidepressants.

We also looked at research that explored whether depression can be induced in volunteers by artificially lowering levels of serotonin . Two systematic reviews from 2006 and 2007 and a sample of the ten most recent studies (at the time the current research was conducted) found that lowering serotonin did not produce depression in hundreds of healthy volunteers. One of the reviews showed very weak evidence of an effect in a small subgroup of people with a family history of depression, but this only involved 75 participants.

Very large studies involving tens of thousands of patients looked at gene variation , including the gene that has the instructions for making the serotonin transporter . They found no difference in the frequency of varieties of this gene between people with depression and healthy controls.

Although a famous early study found a relationship between the serotonin transporter gene and stressful life events , larger, more comprehensive studies suggest no such relationship exists. Stressful life events in themselves, however, exerted a strong effect on people's subsequent risk of developing depression.

Some of the studies in our overview that included people who were taking or had previously taken antidepressants showed evidence that antidepressants may actually lower the concentration or activity of serotonin.

Not supported by the evidence

The serotonin theory of depression has been one of the most influential and extensively researched biological theories of the origins of depression. Our study shows that this view is not supported by scientific evidence. It also calls into question the basis for the use of antidepressants.

Most antidepressants now in use are presumed to act via their effects on serotonin. Some also affect the brain chemical noradrenaline. But experts agree that the evidence for the involvement of noradrenaline in depression is weaker than that for serotonin .

There is no other accepted pharmacological mechanism for how antidepressants might affect depression. If antidepressants exert their effects as placebos, or by numbing emotions, then it is not clear that they do more good than harm.

Although viewing depression as a biological disorder may seem like it would reduce stigma, in fact, research has shown the opposite, and also that people who believe their own depression is due to a chemical imbalance are more pessimistic about their chances of recovery.

It is important that people know that the idea that depression results from a "chemical imbalance" is hypothetical. And we do not understand what temporarily elevating serotonin or other biochemical changes produced by antidepressants do to the brain. We conclude that it is impossible to say that taking SSRI antidepressants is worthwhile, or even completely safe. People need all this information to make informed decisions about whether or not to take antidepressants.

Explore further

Feedback to editors

Study in Haiti suggests early-onset heart failure is prevalent form of heart disease in low-income countries

38 minutes ago

AI algorithms can determine how well newborns nurse, study shows

Kaposi sarcoma discovery and mouse model could facilitate drug development

Immune cell interaction study unlocks novel treatment targets for chikungunya virus

New method rapidly reveals how protein modifications power T cells

Protein responsible for genetic inflammatory disease identified

3 hours ago

Brain function of older adults catching up with younger generations, finds study

Stem cells improve memory, reduce inflammation in Alzheimer's mouse brains

Laws requiring doctors to report a dementia diagnosis to the DMV may backfire

Researchers explore new cell target for cystic fibrosis treatment

4 hours ago

Related Stories

No evidence that depression is caused by low serotonin levels, finds comprehensive review

Jul 20, 2022

Serotonin transporters increase when depression fades, study shows

May 10, 2021

The effect of taking antidepressants during pregnancy

Dec 16, 2019

New drug can ease the side effects of medication against severe depression

Mar 20, 2020

Common antidepressants won't raise risk for bleeding strokes, shows new study

Feb 26, 2021

Study focuses on atomic structure of the serotonin transporter bound to SSRIs

Jan 29, 2018

Recommended for you

Study suggests that stevia is the most brain-compatible sugar substitute

5 hours ago

Nature's nudge: Study shows green views lead to healthier food choices