- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

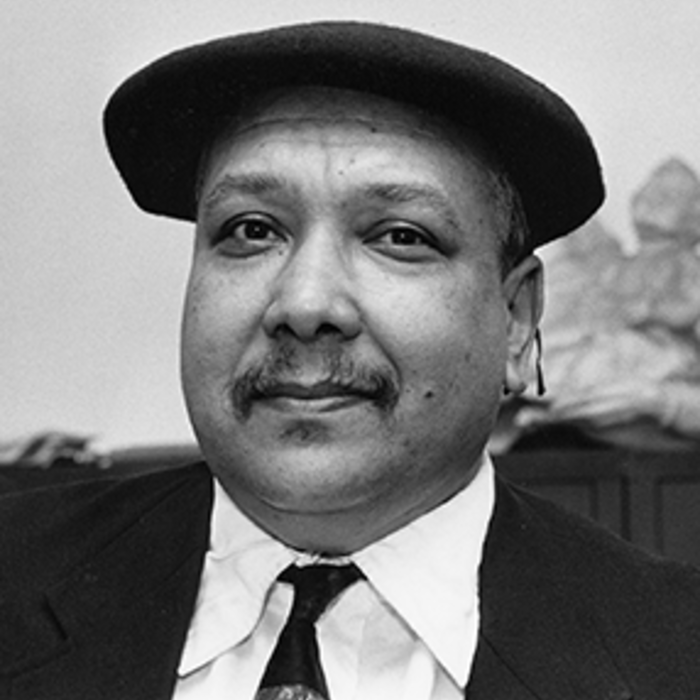

Langston Hughes

By: History.com Editors

Updated: December 15, 2023 | Original: January 24, 2023

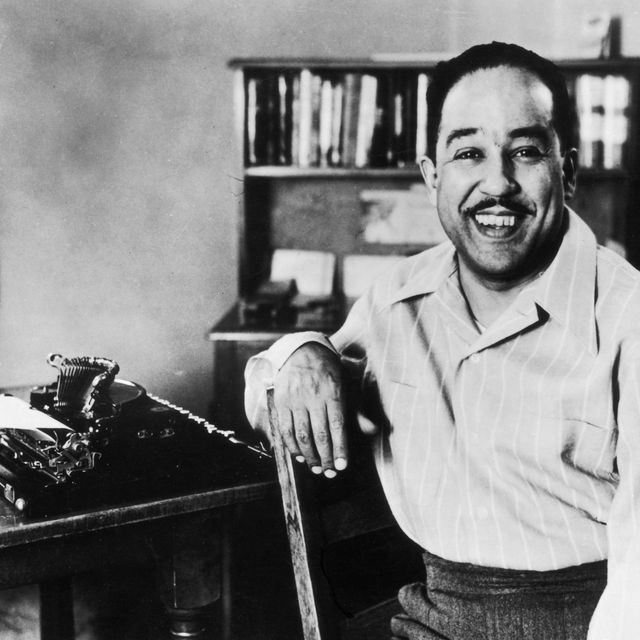

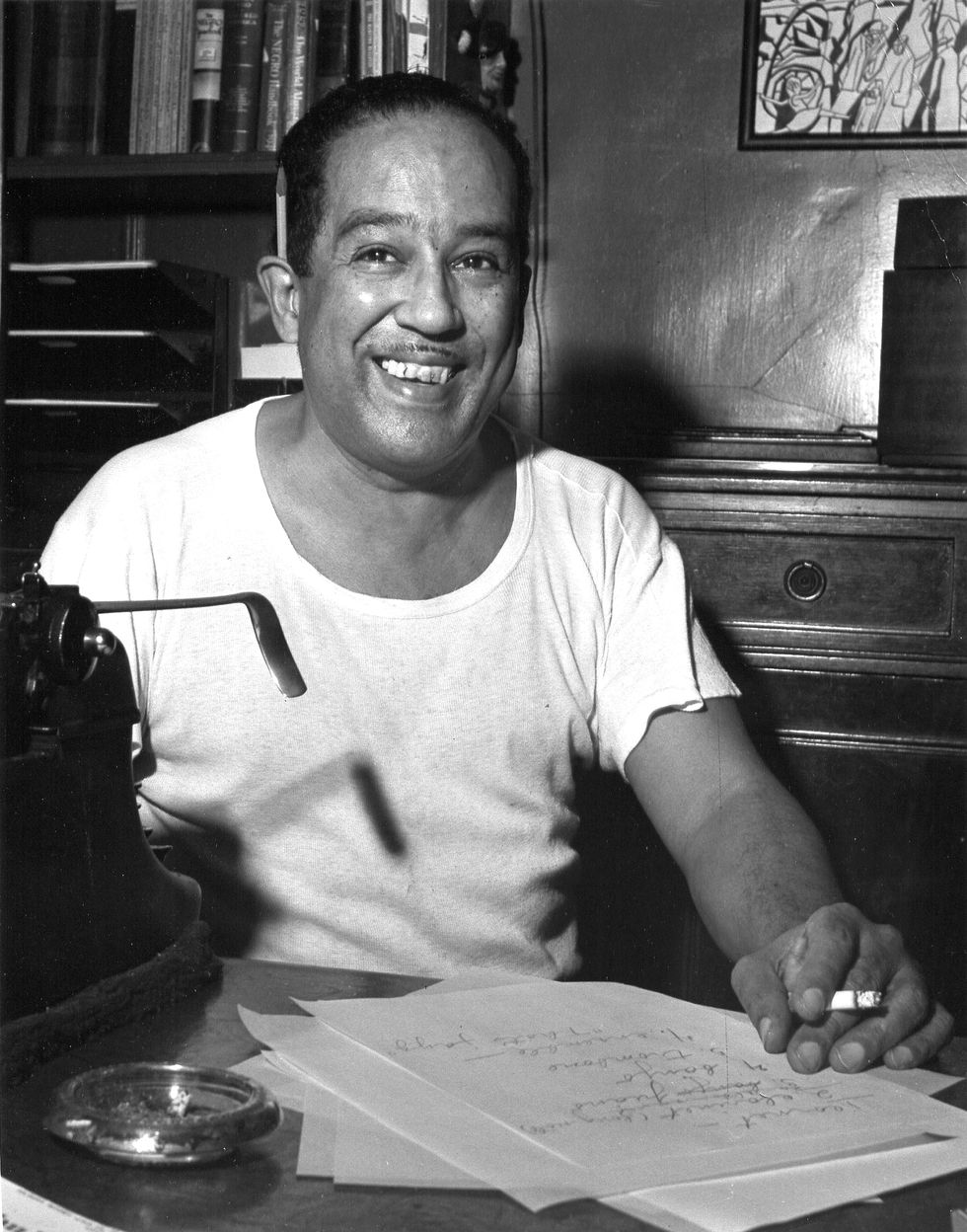

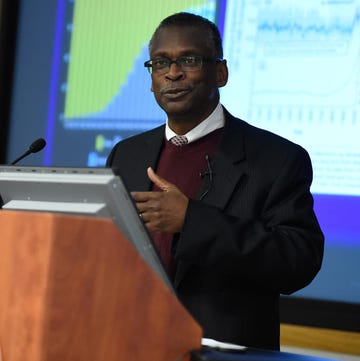

Langston Hughes was a defining figure of the 1920s Harlem Renaissance as an influential poet, playwright, novelist, short story writer, essayist, political commentator and social activist. Known as a poet of the people, his work focused on the everyday lives of the Black working class, earning him renown as one of America’s most notable poets.

Hughes was born February 1, 1902 (although some evidence shows it may have been 1901 ), in Joplin, Missouri, to James and Caroline Hughes. When he was a young boy, his parents divorced, and, after his father moved to Mexico, and his mother, whose maiden name was Langston, sought work elsewhere, he was raised by his grandmother, Mary Langston, in Lawrence, Kansas. Mary Langston died when Hughes was around 12 years old, and he relocated to Illinois to live with his mother and stepfather. The family eventually landed in Cleveland.

According to the first volume of his 1940 autobiography, The Big Sea , which chronicled his life until the age of 28, Hughes said he often used reading to combat loneliness while growing up. “I began to believe in nothing but books and the wonderful world in books—where if people suffered, they suffered in beautiful language, not in monosyllables, as we did in Kansas,” he wrote.

In his Ohio high school, he started writing poetry, focusing on what he called “low-down folks” and the Black American experience. He would later write that he was influenced at a young age by Carl Sandburg, Walt Whitman and Paul Laurence Dunbar. Upon graduating in 1920, he traveled to Mexico to live with his father for a year. It was during this period that, still a teenager, he wrote “ The Negro Speaks of Rivers ,” a free-verse poem that ran in the NAACP ’s The Crisis magazine and garnered him acclaim. It read, in part:

“I’ve known rivers:

I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.”

Traveling the World

Hughes returned from Mexico and spent one year studying at Columbia University in New York City . He didn’t love the experience, citing racism, but he became immersed in the burgeoning Harlem cultural and intellectual scene, a period now known as the Harlem Renaissance.

Hughes worked several jobs over the next several years, including cook, elevator operator and laundry hand. He was employed as a steward on a ship, traveling to Africa and Europe, and lived in Paris, mingling with the expat artist community there, before returning to America and settling down in Washington, D.C. It was in the nation’s capital that, while working as a busboy, he slipped his poetry to the noted poet Vachel Lindsay, cited as the father of modern singing poetry, who helped connect Hughes to the literary world.

Hughes’ first book of poetry, The Weary Blues was published in 1926, and he received a scholarship to and, in 1929, graduated from, Pennsylvania’s Lincoln University. He soon published Not Without Laughter , his first novel, which was awarded the Harmon Gold Medal for literature.

Jazz Poetry

Called the “Poet Laureate of Harlem,” he is credited as the father of jazz poetry, a literary genre influenced by or sounding like jazz, with rhythms and phrases inspired by the music.

“But jazz to me is one of the inherent expressions of Negro life in America; the eternal tom-tom beating in the Negro soul—the tom-tom of revolt against weariness in a white world, a world of subway trains, and work, work, work; the tom-tom of joy and laughter, and pain swallowed in a smile,” he wrote in the 1926 essay, “ The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain .”

Writing for a general audience, his subject matter continued to focus on ordinary Black Americans. Hughes wrote that his 1927 work, “Fine Clothes to the Jew,” was about “workers, roustabouts, and singers, and job hunters on Lenox Avenue in New York, or Seventh Street in Washington or South State in Chicago—people up today and down tomorrow, working this week and fired the next, beaten and baffled, but determined not to be wholly beaten, buying furniture on the installment plan, filling the house with roomers to help pay the rent, hoping to get a new suit for Easter—and pawning that suit before the Fourth of July."

He also did not shy from writing about his experiences and observations.

“We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame,” he wrote in the The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain . “If white people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn’t matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly too.”

Ever the traveler, Hughes spent time in the South, chronicling racial injustices, and also the Soviet Union in the 1930s, showing an interest in communism . (He was called to testify before Congress during the McCarthy hearings in 1953.)

In 1930, Hughes wrote “Mule Bone” with Zora Neale Hurston , his first play, which would be the first of many. “Mulatto: A Tragedy of the Deep South,” about race issues, was Broadway’s longest-running play written by a Black author until Lorraine Hansberry’s 1958 play, “A Raisin in the Sun.” Hansberry based the name of her play on Hughes’ 1951 poem, “ Harlem ” in which he writes,

"What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?...”

Hughes wrote the lyrics for “Street Scene,” a 1947 Broadway musical, and set up residence in a Harlem brownstone on East 127th Street. He co-founded the New York Suitcase Theater, as well as theater troupes in Los Angeles and Chicago. He attempted screenwriting in Hollywood, but found racism blocked his efforts.

He worked as a newspaper war correspondent in 1937 for the Baltimore Afro American , writing about Black American soldiers fighting for the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War . He also wrote a column from 1942-1962 for the Chicago Defender , a Black newspaper, focusing on Jim Crow laws and segregation , World War II and the treatment of Black people in America. The column often featured the fictitious Jesse B. Semple, known as Simple.

In the 1950s and ’60s, Hughes wrote a “First Book” series of children's books, patriotic stories about Black culture and achievements, including The First Book of Negroes (1952), The First Book of Jazz (1955), and The Book of Negro Folklore (1958). Among the stories in the 1958 volume is "Thank You, Ma'am," in which a young teenage boy learns a lesson about trust and respect when an older woman he tries to rob ends up taking him home and giving him a meal.

Hughes died in New York from complications during surgery to treat prostate cancer on May 22, 1967, at the age of 65. His ashes are interred in Harlem’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. His Harlem home was named a New York landmark in 1981, and a National Register of Places a year later.

"I, too, am America," a quote from his 1926 poem, " I, too, " is engraved on the wall of the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

“ Langston Hughes ,” The Library of Congress

“ Langston Hughes: The People's Poet ,” Smithsonian Magazine

“ The Blues and Langston Hughes ,” Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh

“ Langston Hughes ,” Poets.org

HISTORY Vault: Black History

Watch acclaimed Black History documentaries on HISTORY Vault.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- National Poetry Month

- Materials for Teachers

- Literary Seminars

- American Poets Magazine

Main navigation

- Academy of American Poets

User account menu

Search more than 3,000 biographies of contemporary and classic poets.

Page submenu block

- literary seminars

- materials for teachers

- poetry near you

Langston Hughes

James Mercer Langston Hughes was born on February 1, 1901, in Joplin, Missouri. Hughes’s birth year was revised from 1902 to 1901 after new research from 2018 uncovered that he had been born a year earlier. His parents, James Nathaniel Hughes and Carrie Langston Hughes, divorced when he was a young child, and his father moved to Mexico. He was raised by his maternal grandmother, Mary Sampson Patterson Leary Langston, who was nearly seventy when Hughes was born, until he was thirteen. He then moved to Lincoln, Illinois, to live with his mother and her husband, before the family eventually settled in Cleveland. It was in Lincoln that Hughes began writing poetry.

After graduating from high school, he spent a year in Mexico followed by a year at Columbia University. During this time, he worked as an assistant cook, a launderer, and a busboy. He also traveled to Africa and Europe working as a seaman. In November 1924, he moved to Washington, D.C. Hughes’s first book of poetry, The Weary Blues , (Knopf, 1926) was published by Alfred A. Knopf in 1926 with an introduction by Harlem Renaissance arts patron Carl Van Vechten . Criticism of the book from the time varied, with some praising the arrival of a significant new voice in poetry, while others dismissed Hughes’s debut collection. He finished his college education at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania three years later. In 1930 his first novel, Not Without Laughter (Knopf, 1930), won the Harmon gold medal for literature.

Hughes, who cited Paul Laurence Dunbar , Carl Sandburg , and Walt Whitman as his primary influences, is particularly known for his insightful portrayals of Black life in America from the 1920s to the 1960s. He wrote novels, short stories, plays, and poetry, and is also known for his engagement with the world of jazz and the influence it had on his writing, as in his book-length poem Montage of a Dream Deferred (Holt, 1951). His life and work were enormously important in shaping the artistic contributions of the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s. Unlike other notable Black poets of the period, such as Claude McKay , Jean Toomer , and Countee Cullen , Hughes refused to differentiate between his personal experience and the common experience of Black America. He wanted to tell the stories of his people in ways that reflected their actual culture, including their love of music, laughter, and language, alongside their suffering.

The critic Donald B. Gibson noted in the introduction to Modern Black Poets: A Collection of Critical Essays (Prentice Hall, 1973) that Hughes

differed from most of his predecessors among black poets… in that he addressed his poetry to the people, specifically to black people. During the twenties when most American poets were turning inward, writing obscure and esoteric poetry to an ever decreasing audience of readers, Hughes was turning outward, using language and themes, attitudes and ideas familiar to anyone who had the ability simply to read... Until the time of his death, he spread his message humorously—though always seriously—to audiences throughout the country, having read his poetry to more people (possibly) than any other American poet.

In addition to leaving us a large body of poetic work, Hughes wrote eleven plays and countless works of prose, including the well-known “Simple” books: Simple’s Uncle Sam (Hill and Wang, 1965); Simple Stakes a Claim (Rinehart, 1957); Simple Takes a Wife (Simon & Schuster, 1953); Simple Speaks His Mind (Simon & Schuster, 1950). He coedited the The Poetry of the Negro, 1746–1949 (Doubleday & Co., Inc., 1949) with Arna Bontemps , edited The Book of Negro Folklore (Dodd, Mead & Company, 1958), and wrote an acclaimed autobiography, The Big Sea (Knopf, 1940). Hughes also cowrote the play Mule Bone (HarperCollins, 1991) with Zora Neale Hurston.

Langston Hughes died of complications from prostate cancer on May 22, 1967, in New York City. In his memory, his residence at 20 East 127th Street in Harlem has been given landmark status by the New York City Preservation Commission, and East 127th Street has been renamed “Langston Hughes Place.”

Related Poets

Michael S. Harper

Michael S. Harper was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1938.

Sterling A. Brown

Sterling Brown was born in Washington, D.C., in 1901. He was educated

Sonia Sanchez

Sonia Sanchez received the 2018 Wallace Stevens Award , given annually to recognize outstanding and proven mastery in the art of poetry.

Leslie Pinckney Hill

Leslie Pinckney Hill was born in Lynchburg, Virginia, on May 14, 1880.

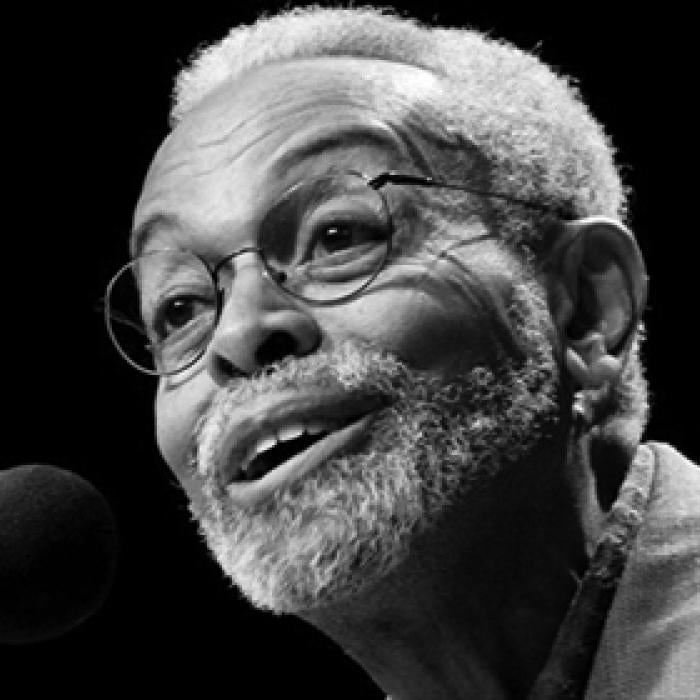

Amiri Baraka

Poet, playwright, and social advocate Amiri Baraka, considered one of the founders of the Black Arts movement, was known for his outspoken stance against police brutality and racial discrimination, his divisive politics, and his leadership in the Pan-Africanist movement.

Jessie Redmon Fauset

Jessie Redmon Fauset, born in 1882, played a crucial role in the Harlem Renaissance during her time as literary editor of The Crisis.

Newsletter Sign Up

- Academy of American Poets Newsletter

- Academy of American Poets Educator Newsletter

- Teach This Poem

Biography of Langston Hughes, Poet, Key Figure in Harlem Renaissance

Hughes wrote about the African-American experience

Underwood Archives / Getty Images

- Favorite Poems & Poets

- Poetic Forms

- Best Sellers

- Classic Literature

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/JS800-800-5b70ad0c46e0fb00501895cd.jpg)

- B.A., English, Rutgers University

Langston Hughes was a singular voice in American poetry, writing with vivid imagery and jazz-influenced rhythms about the everyday Black experience in the United States. While best-known for his modern, free-form poetry with superficial simplicity masking deeper symbolism, Hughes worked in fiction, drama, and film as well.

Hughes purposefully mixed his own personal experiences into his work, setting him apart from other major Black poets of the era, and placing him at the forefront of the literary movement known as the Harlem Renaissance . From the early 1920s to the late 1930s, this explosion of poetry and other work by Black Americans profoundly changed the artistic landscape of the country and continues to influence writers to this day.

Fast Facts: Langston Hughes

- Full Name: James Mercer Langston Hughes

- Known For: Poet, novelist, journalist, activist

- Born: February 1, 1902 in Joplin, Missouri

- Parents: James and Caroline Hughes (née Langston)

- Died: May 22, 1967 in New York, New York

- Education: Lincoln University of Pennsylvania

- Selected Works: The Weary Blues, The Ways of White Folks, The Negro Speaks of Rivers, Montage of a Dream Deferred

- Notable Quote: "My soul has grown deep like the rivers."

Early Years

Langston Hughes was born in Joplin, Missouri, in 1902. His father divorced his mother shortly thereafter and left them to travel. As a result of the split, he was primarily raised by his grandmother, Mary Langston, who had a strong influence on Hughes, educating him in the oral traditions of his people and impressing upon him a sense of pride; she was referred to often in his poems. After Mary Langston died, Hughes moved to Lincoln, Illinois, to live with his mother and her new husband. He began writing poetry shortly after enrolling in high school.

Hughes moved to Mexico in 1919 to live with his father for a short time. In 1920, Hughes graduated high school and returned to Mexico. He wished to attend Columbia University in New York and lobbied his father for financial assistance; his father did not think writing was a good career, and offered to pay for college only if Hughes studied engineering. Hughes attended Columbia University in 1921 and did well, but found the racism he encountered there to be corrosive—though the surrounding Harlem neighborhood was inspiring to him. His affection for Harlem remained strong for the rest of his life. He left Columbia after one year, worked a series of odd jobs, and traveled to Africa working as a crewman on a boat, and from there on to Paris. There he became part of the Black expatriate community of artists.

The Crisis to Fine Clothes to the Jew (1921-1930)

- The Negro Speaks of Rivers (1921)

- The Weary Blues (1926)

- The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain (1926)

- Fine Clothes to the Jew (1927)

- Not Without Laughter (1930)

Hughes wrote his poem The Negro Speaks of Rivers while still in high school, and published it in The Crisis , the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The poem gained Hughes a great deal of attention; influenced by Walt Whitman and Carl Sandburg, it is a tribute to Black people throughout history in a free verse format:

I’ve known rivers: I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins. My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

Hughes began to publish poems on a regular basis, and in 1925 won the Poetry Prize from Opportunity Magazine . Fellow writer Carl Van Vechten, who Hughes had met on his overseas travels, sent Hughes’ work to Alfred A. Knopf, who enthusiastically published Hughes’ first collection of poetry, The Weary Blues in 1926.

Around the same time, Hughes took advantage of his job as a busboy in a Washington, D.C., hotel to give several poems to poet Vachel Lindsay, who began to champion Hughes in the mainstream media of the time, claiming to have discovered him. Based on these literary successes, Hughes received a scholarship to Lincoln University in Pennsylvania and published The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain in The Nation . The piece was a manifesto calling for more Black artists to produce Black-centric art without worrying whether white audiences would appreciate it—or approve of it.

In 1927, Hughes published his second collection of poetry, Fine Clothes to the Jew. He graduated with a bachelor’s degree in 1929. In 1930, Hughes published Not Without Laughter , which is sometimes described as a "prose poem" and sometimes as a novel, signaling his continued evolution and his impending experiments outside of poetry.

By this point, Hughes was firmly established as a leading light in what is known as the Harlem Renaissance. The literary movement celebrated Black art and culture as public interest in the subject soared.

Fiction, Film, and Theater Work (1931-1949)

- The Ways of White Folks (1934)

- Mulatto (1935)

- Way Down South (1935)

- The Big Sea (1940)

Hughes traveled through the American South in 1931 and his work became more forcefully political, as he became increasingly aware of the racial injustices of the time. Always sympathetic to communist political theory, seeing it as an alternative to the implicit racism of capitalism, he also traveled extensively through the Soviet Union during the 1930s.

He published his first collection of short fiction, The Ways of White Folks , in 1934. The story cycle is marked by a certain pessimism in regards to race relations; Hughes seems to suggest in these stories that there will never be a time without racism in this country. His play Mulatto , first staged in 1935, deals with many of the same themes as the most famous story in the collection, Cora Unashamed , which tells the story of a Black servant who develops a close emotional bond with the young white daughter of her employers.

Hughes became increasingly interested in the theater, and founded the New York Suitcase Theater with Paul Peters in 1931. After receiving a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1935, he also co-founded a theater troupe in Los Angeles while co-writing the screenplay for the film Way Down South . Hughes imagined he would be an in-demand screenwriter in Hollywood; his failure to gain much success in the industry was put down to racism. He wrote and published his autobiography The Big Sea in 1940 despite being only 28 years old; the chapter titled Black Renaissance discussed the literary movement in Harlem and inspired the name "Harlem Renaissance."

Continuing his interest in theater, Hughes founded the Skyloft Players in Chicago in 1941 and began writing a regular column for the Chicago Defender , which he would continue to write for two decades. After World War II and the Civil Rights Movement ’s rise and successes, Hughes found that the younger generation of Black artists, coming into a world where segregation was ending and real progress seemed possible in terms of race relations and the Black experience, saw him as a relic of the past. His style of writing and Black-centric subject matter seemed passé .

Children’s Books and Later Work (1950-1967)

- Montage of a Dream Deferred (1951)

- The First Book of the Negroes (1952)

- I Wonder as I Wander (1956)

- A Pictorial History of the Negro in America (1956)

- The Book of Negro Folklore (1958)

Hughes attempted to interact with the new generation of Black artists by directly addressing them, but rejecting what he saw as their vulgarity and over-intellectual approach. His epic poem "suite," Montage of a Dream Deferred (1951) took inspiration from jazz music, collecting a series of related poems sharing the overarching theme of a "dream deferred" into something akin to a film montage—a series of images and short poems following quickly after each other in order to position references and symbolism together. The most famous section from the larger poem is the most direct and powerful statement of the theme, known as Harlem :

What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun? Or fester like a sore— And then run? Does it stink like rotten meat? Or crust and sugar over— like a syrupy sweet? Maybe it just sags like a heavy load. Or does it explode ?

In 1956, Hughes published his second autobiography, I Wonder as I Wander . He took a greater interest in documenting the cultural history of Black America, producing A Pictorial History of the Negro in America in 1956, and editing The Book of Negro Folklore in 1958.

Hughes continued to work throughout the 1960s and was considered by many to be the leading writer of Black America at the time, although none of his works after Montage of a Dream Deferred approached the power and clarity of his work during his prime.

Although Hughes had previously published a book for children in 1932 ( Popo and Fifina ), in the 1950s he began publishing books specifically for children regularly, including his First Book series, which was designed to instill a sense of pride in and respect for the cultural achievements of African Americans in its youth. The series included The First Book of the Negroes (1952), The First Book of Jazz (1954), The First Book of Rhythms (1954), The First Book of the West Indies (1956), and The First Book of Africa (1964).

The tone of these children’s books was perceived as very patriotic as well as focused on the appreciation of Black culture and history. Many people, aware of Hughes’ flirtations with communism and his run-in with Senator McCarthy , suspected he attempted to make his children’s books self-consciously patriotic in order to combat any perception that he might not be a loyal citizen.

Personal Life

While Hughes reportedly had several affairs with women during his life, he never married or had children. Theories concerning his sexual orientation abound; many believe that Hughes, known for strong affections for Black men in his life, seeded clues about his homosexuality throughout his poems (something Walt Whitman, one of his key influences, was known to do in his own work). However, there is no overt evidence to support this, and some argue that Hughes was, if anything, asexual and uninterested in sex.

Despite his early and long-term interest in socialism and his visit to the Soviet Union, Hughes denied being a communist when called to testify by Senator Joseph McCarthy. He then distanced himself from communism and socialism, and was thus estranged from the political left that had often supported him. His work dealt less and less with political considerations after the mid-1950s as a result, and when he compiled the poems for his 1959 collection Selected Poems, he excluded most of his more politically-focused work from his youth.

Hughes was diagnosed with prostate cancer, and entered the Stuyvesant Polyclinic in New York City on May 22, 1967 to undergo surgery to treat the disease. Complications arose during the procedure, and Hughes passed away at the age of 65. He was cremated, and his ashes interred in the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, where the floor bears a design based on his poem The Negro Speaks of Rivers , including a line from the poem inscribed on the floor.

Hughes turned his poetry outward at a time in the early 20th century when Black artists were increasingly turning inward, writing for an insular audience. Hughes wrote about Black history and the Black experience, but he wrote for a general audience, seeking to convey his ideas in emotional, easily-understood motifs and phrases that nevertheless had power and subtlety behind them.

Hughes incorporated the rhythms of modern speech in Black neighborhoods and of jazz and blues music, and he included characters of "low" morals in his poems, including alcoholics, gamblers, and prostitutes, whereas most Black literature sought to disavow such characters because of a fear of proving some of the worst racist assumptions. Hughes felt strongly that showing all aspects of Black culture was part of reflecting life and refused to apologize for what he called the "indelicate" nature of his writing.

- Als, Hilton. “The Elusive Langston Hughes.” The New Yorker, The New Yorker, 9 July 2019, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/02/23/sojourner.

- Ward, David C. “Why Langston Hughes Still Reigns as a Poet for the Unchampioned.” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 22 May 2017, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/why-langston-hughes-still-reigns-poet-unchampioned-180963405/.

- Johnson, Marisa, et al. “Women in the Life of Langston Hughes.” US History Scene, http://ushistoryscene.com/article/women-and-hughes/.

- McKinney, Kelsey. “Langston Hughes Wrote a Children's Book in 1955.” Vox, Vox, 2 Apr. 2015, https://www.vox.com/2015/4/2/8335251/langston-hughes-jazz-book.

- Poets.org, Academy of American Poets, https://poets.org/poet/langston-hughes.

- 5 Writers of the Harlem Renaissance

- Men of the Harlem Renaissance

- Arna Bontemps, Documenting the Harlem Renaissance

- Literary Timeline of the Harlem Renaissance

- Black History Timeline: 1920–1929

- Harlem Renaissance Women

- Biography of James Weldon Johnson

- Black History Timeline: 1930–1939

- 5 Leaders of the Harlem Renaissance

- Biography of Georgia Douglas Johnson, Harlem Renaissance Writer

- An Early Verson of Flash Fiction by Poet Langston Hughes

- Women of the Harlem Renaissance

- 4 Publications of the Harlem Renaissance

- Zora Neale Hurston

- Biography of Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, African History Expert

- Poems to Read on Thanksgiving Day

Find anything you save across the site in your account

The Elusive Langston Hughes

By Hilton Als

By the time the British artist Isaac Julien’s iconic short essay-film “Looking for Langston” was released, in 1989, Julien’s ostensible subject, the enigmatic poet and race man Langston Hughes, had been dead for twenty-two years, but the search for his “real” story was still ongoing. There was a sense—particularly among gay men of color, like Julien, who had so few “out” ancestors and wanted to claim the prolific, uneven, but significant writer as one of their own—that some essential things about Hughes had been obscured or disfigured in his work and his memoirs. Born in Joplin, Missouri, in 1902, and transplanted to New York City as a strikingly handsome nineteen-year-old, Hughes became, with the publication of his first book of poems, “The Weary Blues” (1926), a prominent New Negro: modern, pluralistic in his beliefs, and a member of what the folklorist and novelist Zora Neale Hurston called “the niggerati,” a loosely formed alliance of black writers and intellectuals that included Hurston, the author and diplomat James Weldon Johnson, the openly gay poet and artist Richard Bruce Nugent, and the novelists Nella Larsen, Jessie Fauset, and Wallace Thurman (whose 1929 novel about color fixation among blacks, “The Blacker the Berry,” conveys some of the energy of the time).

In a 1926 essay for The Nation , “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” Hughes described the group, which came together during the Harlem Renaissance, when hanging out uptown was considered a lesson in cool:

We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. If white people are pleased, we are glad. If they are not, it doesn’t matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly too. The tom-tom cries and the tom-tom laughs. If colored people are pleased we are. If they are not, their displeasure doesn’t matter either. We build our temples for tomorrow, strong as we know how, and we stand on top of the mountain, free within ourselves.

And yet, in his personal life, Hughes did not stand on top of the mountain, proclaiming who he was or what he thought. One of the architects of black political correctness, he saw as threatening any attempt to expose black difference or weakness in front of a white audience. In his approach to the work of other black artists, in particular, he was excessively inclusive, enthusiastic to the point of self-effacement, as if black creativity were a great wave that would wash away the psychic scars of discrimination. Hughes was uncomfortable when younger black writers, such as James Baldwin and Ralph Ellison (whom Hughes mentored from the day after he arrived in Harlem, in 1936, until it was no longer convenient for Ellison to be associated with the less careful craftsman), criticized other black writers. Hughes’s reluctance to reveal the cracks in the black world—which is to say, his own world—curtailed not only what he was able to achieve as an artist but what he was able to express as a man.

Instead of coming to grips with himself and his potential, he developed what he considered to be a palatable or marketable public persona. There he is, smiling, humble, industrious, and hidden, in Arnold Rampersad’s two-volume biography, “The Life of Langston Hughes” (1986 and 1988), not to mention in such important recent works about the period as Carla Kaplan’s “Miss Anne in Harlem” and Farah Jasmine Griffin’s “Harlem Nocturne” (both 2013). Even in much of his own correspondence—in the recently published “The Selected Letters of Langston Hughes,” edited by Rampersad and David Roessel, with Christa Fratantoro—one senses that Hughes is performing a version of himself that he feels is socially acceptable. (While “The Selected Letters” is a good place to start finding out about Hughes and his world, one sees more of his naughtiness and sense of play in some of the narrower collections, including “Remember Me to Harlem: The Letters of Langston Hughes and Carl Van Vechten,” which was edited with verve and insight by Emily Bernard.) The Hughes persona also appears in his most celebrated verses, which marry down-home Southern locutions with urban rhythms. From “The Weary Blues”:

I heard a Negro play. Down on Lenox Avenue the other night By the pale dull pallor of an old gas light He did a lazy sway. . . . He did a lazy sway. . . . To the tune o’ those Weary Blues. With his ebony hands on each ivory key He made that poor piano moan with melody. . . . In a deep song voice with a melancholy tone I heard that Negro sing, that old piano moan— “Ain’t got nobody in all this world, Ain’t got nobody but ma self. I’s gwine to quit ma frownin’ And put ma troubles on the shelf.”

Writing about Hughes’s “Selected Poems” in the Times in 1959, Baldwin—who chastised his elder for reducing blackness to a kind of pleasant Negro simplicity—began with a bang:

Every time I read Langston Hughes I am amazed all over again by his genuine gifts—and depressed that he has done so little with them. . . . Hughes, in his sermons, blues and prayers, has working for him the power and the beat of Negro speech and Negro music. Negro speech is vivid largely because it is private. It is a kind of emotional shorthand—or sleight of hand—by means of which Negroes express not only their relationship to each other but their judgment of the white world. . . . Hughes knows the bitter truth behind these hieroglyphics: what they are designed to protect, what they are designed to convey. But he has not forced them into the realm of art, where their meaning would become clear and overwhelming.

Possibly, Baldwin—the author of the landmark gay love story “Giovanni’s Room”—was upset less by Hughes’s failures as a poet than by his refusal to reveal the truth behind his own hieroglyphics: his sexuality, which appears only in glimpses in his work. (And in the work of others, including Richard Bruce Nugent’s 1926 story “Smoke, Lilies, and Jade,” which Hughes published in Fire!! , a literary magazine that Wallace Thurman edited, and in which a young man walking in Harlem bumps into “Langston,” who’s in the company of a striking boy.) Thurman, expressing his frustration at how little he knew about Hughes’s private self, wrote to him once, “You are in the final analysis the most consarned and diabolical creature, to say nothing of being either the most egregiously simple or excessively complex person I know.” Even Rampersad’s biography, which is as rich a study of a life as one could wish for, was criticized by gay readers for its emphatic I-don’t-know-anything-specific-about-his-romantic-life pronouncements. In Rampersad’s work, Hughes emerges as a constantly striving, almost asexual entity—which is pretty much the image that Hughes himself put forth.

Reading Hughes’s work, one is reminded of these lines by the black poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, one of Hughes’s early enthusiasms:

We wear the mask that grins and lies, It hides our cheeks and shades our eyes,— This debt we pay to human guile; With torn and bleeding hearts we smile, And mouth with myriad subtleties.

That mask was what kept Hughes from including such works as “Café: 3 A.M. ” in his “Selected Poems,” which he edited:

Detectives from the vice squad with weary sadistic eyes spotting fairies. Degenerates , some folks say. But God, Nature, or somebody made them that way. Police lady or Lesbian over there? Where?

And where was Langston? His tight-lippedness when it came to his own “degenerate” behavior kept him from identifying such people as “F.S.,” the dedicatee of another poem (who may have been Ferdinand Smith, a Jamaican merchant seaman Hughes met in Harlem) that appeared in “The Weary Blues”:

I loved my friend. He went away from me. There is nothing more to say. The poem ends, Soft as it began— I loved my friend.

Hughes’s genial, generous, and guarded persona was self-protective, certainly. It’s important to remember that he came of age in an era during which gay men—and blacks—were physically and mentally abused for being what they were. (He was self-preserving in other areas of his life as well. To protect his career, he testified at the House Un-American Activities Committee proceedings, which cost him his friendships with W.E.B. Du Bois and Paul Robeson.) Hughes’s mask was likely also a bulwark against his personal history, which he rarely discussed, even in his elusive autobiographies, “The Big Sea” (1940) and “I Wonder as I Wander” (1956), one of the most apt titles ever penned by Hughes: his memoir is littered with short sojourns and partings, a pattern he learned in a home where the laughter was often derisive and love was a form of humiliation.

Hughes’s mother, the impulsive and vibrant Carrie Langston, was born in Lawrence, Kansas, in 1873, of African, Native American, and French ancestry. Her father, Charles Langston, an enterprising farmer and grocer, was also a fierce abolitionist, whose youngest brother, John Mercer Langston, became a prominent figure in nineteenth-century black America—a professor of law, a dean, and then the acting president of Howard University. As a girl, Carrie Langston was known as “the Belle of Black Lawrence.” Hungry for attention, she aspired to a career on the stage, but her dreams were stymied by prejudice and by the limits of a nineteenth-century woman’s life. With few real options open to her, she completed a course in elementary-school education, and in 1898, already in love with travel, moved to Guthrie, in the Oklahoma Territory, some ten miles from Langston, a town named for her famous uncle. There the light-skinned Carrie met and married James Nathaniel Hughes, a handsome, hardworking man of color, with African, Native American, French, and Jewish blood. (His grandfathers were both slave traders.) But there was a crucial difference between the newlyweds: whereas Carrie had been brought up to be proud of her race, the color-struck James despised blackness, which he equated with poverty and powerlessness.

In 1899, the young, ambitious couple moved to Joplin, where Carrie gave birth to Langston in 1902. (Their first child, a boy, born in 1900, died in infancy.) A year later, when James secured a position in Mexico City, where he felt that he stood a better chance of success, Carrie dropped Langston off at her mother’s, and followed him south. The couple bickered, reconciled, parted, sometimes with Langston in tow, often not; for the most part, the boy was reared by his judicious but loving grandmother, Mary. By 1907, they had separated permanently.

There’s nothing like family to remind you of life’s essential loneliness. As a boy, Hughes absorbed his mother’s bitterness about her marriage and her thwarted career, as well as his father’s anxiety and rancor over racism in America and what he presumed to be its cause: blacks themselves. (Hughes recalled a train journey through Arkansas, during which his father, seeing some blacks at work in a cotton field, sneered, “Look at the niggers.”) Carrie never hesitated to tell her son that he resembled his father—“that devil”—and that he was as “evil as Jim Hughes.” His grandmother, angry about segregation—as a black person, she couldn’t join the church of her choice—forbade her grandson to go out after school: Why risk degradation in their sty?

Hughes grew up in an atmosphere of hatred and small-mindedness. While he was in elementary school, a white teacher warned one of Hughes’s white classmates against eating licorice, for fear that he would end up looking like Langston. A bright, genial boy, Hughes also suffered for his talents. From his poem “Genius Child”:

Nobody loves a genius child. Can you love an eagle, Tame or wild? Can you love an eagle, Wild or tame? Can you love a monster Of frightening name? Nobody loves a genius child. Kill him —and let his soul run wild.

Still, there was solace. There were books by W. E. B. Du Bois, and the formality and strange wisdom of the Bible. (Hughes read widely and deeply in the black and white American canons. And, throughout his career, he excitedly read the writers of color who were published in Europe, the Caribbean, and Africa, including René Maran, Graziella Garbalosa, and Richard Rive.) There was black pride, too. In 1910, Mary and her grandson went to Osawatomie, Kansas, where former President Theodore Roosevelt honored her first husband, Lewis Sheridan Leary, who had died during the 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry.

Mary herself died in 1915, and the thirteen-year-old Hughes soon left Kansas for Lincoln, Illinois, where his mother now lived with her second husband, Homer Clark, a sometime “chef cook,” and his son. In Lincoln, a teacher asked Hughes’s eighth-grade class to appoint a class poet who understood rhythm. Hughes’s fellow-students unanimously nominated Hughes, the only black boy in the class. Hughes wrote his first poem for the class graduation, and was so impressed by the applause he received that he wondered whether he had found his vocation. As Homer sought better career opportunities that never seemed to materialize, Hughes followed his mother and her new family to Cleveland, where he began contributing poems and stories to his high-school magazine. When his mother and his stepfather moved on again, to Chicago, Hughes stayed behind to finish high school, which he did in 1920. Although he was pretty much on his own from then on, his parents exercised a pull over him for as long as they lived. (“My Dear Boy: Carrie Hughes’s Letters to Langston Hughes, 1926-1938,” edited by Carmaletta M. Williams and John Edgar Tidwell, is valuable testimony to Carrie’s never-ending attempts to manipulate her son.)

Open to Hughes was the great wide world, the adventure of travel, and those writers—Carl Sandburg, Walt Whitman—who not only freed the young writer from traditional literary forms but showed him that he could sing his America, too. In 1921, he moved to New York to study at Columbia University, but what he fell in love with was the “Negro city”: Harlem. (He eventually dropped out of Columbia, and graduated from Lincoln University, in Pennsylvania, in 1929.) Before coming to New York, he had spent more than a year in patriarchal purgatory in Mexico; now he was “hungry” to be with his people. Exiting the subway at 135th Street, he said, “I stood there, dropped my bags, took a deep breath and felt happy again.”

Harlem in the twenties offered up a cultural richness that made everything seem possible. Jervis Anderson, writing in this magazine in 1981, noted, “Harlem has never been more high-spirited and engaging than it was during the nineteen-twenties. Blacks from all over America and the Caribbean were pouring in, reviving the migration that had abated toward the end of the war—word having reached them about the ‘city,’ in the heart of Manhattan, that blacks were making their own.” The headquarters for Du Bois’s magazine Crisis , to which Hughes had been contributing from Mexico, was there; so was Messenger , co-edited by the activist A. Philip Randolph. Soon Hughes found a new source of the kind of support that his grandmother had given him as a boy: a wealthy white woman named Charlotte Osgood Mason, who provided Hughes and other black artists, including Hurston, with financial backing, as long as they promoted blackness. (Despite the awkwardness of the arrangement, Hughes remained loyal to Mason—“I want to be your spirit child forever,” he wrote to her—and when he ceased to be a favorite, in 1930, he was devastated. That pain shows in his forced 1933 short story “Slave on the Block,” which he included in his passionate but ill-considered collection “The Ways of White Folks,” the following year.)

The charming Hughes also managed to melt the heart of the glacial Du Bois, who had lost a son, and counted Jessie Fauset, an editor at Crisis , and the poet Countee Cullen as champions of a sort. In 1923, Cullen introduced Hughes to Alain Locke, a gay Harvard-educated thinker, who published the influential anthology “The New Negro” in 1925. As one can intuit from “The Selected Letters,” the two embarked on a kind of cat-and-mouse game: Hughes needed Locke’s patronage, and, sensing the older man’s attraction to him, kept him at arm’s length to increase the mystery. Soon Hughes was a citizen of a bright black world that included Paul Robeson, who, in 1924, would star downtown in Eugene O’Neill’s “The Emperor Jones.” Putting his ear to the concrete, he heard poems like “Aesthete in Harlem,” which combined, within a short, intense form, the sound of the laughing and crying tom-tom he described in his 1926 Nation essay:

Strange, That in this nigger place I should meet life face to face; When, for years, I had been seeking Life in places gentler speaking— Before I came to this vile street And found Life—stepping on my feet!

The poem, like many of Hughes’s early lyrics, is both interesting and uninspiring. We admire him for the pre-spoken-word cadences and the energy of the enterprise, but without ever knowing who his “I” is we have no anchor in the poem. The ungrounded first-person voice allows Hughes to be humanity, but not a specific human.

Once the Depression put an end to all the champagne and sexy miscegenation of the Harlem Renaissance, the “niggerati” scattered to other gigs, some in other countries. Hughes travelled in Russia during the thirties, finding in Communism, at least for a time, the political hope that was missing in his own country, but he always returned to Harlem, even as the neighborhood suffered through race riots and the drug and civic wars of the fifties and sixties. It was his home until he died, in 1967—his ashes are now entombed in the lobby of the Langston Hughes Auditorium at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, in Harlem—visible evidence of all that Hughes’s father despised and he embraced, in what may very well have been the most unresolvable relationship of his life.

In 1961, twenty-seven years after James Hughes died, his son wrote a brief, intense tale called “Blessed Assurance.” Published posthumously, it begins:

Unfortunately (and to John’s distrust of God) it seemed his son was turning out to be a queer. He was a brilliant queer, on the Honor Roll in high school, and likely to be graduated in the spring at the head of the class. But the boy was colored. Since colored parents always like to put their best foot forward, John was more disturbed about his son’s transition than if they had been white. Negroes have enough crosses to bear.

When the boy sings a solo in the church choir and his voice soars, a male organist faints, and the boy’s father pleads for him to shut up. But the song goes on. What is natural to John’s son is the music, a world of sound which he can both hide behind and expose himself through.

In the final years of his life, Hughes did seem to see the tide turning. His last, and best, collection of poems, “The Panther and the Lash” (1967), reflects, with a haiku-like flatness and lift, a Vietnam-era world that was changing and needed to change. His poem “Corner Meeting”:

Ladder, flag, and amplifier now are what the soapbox used to be.

The speaker catches fire, Looking at listeners’ faces.

His words jump down to stand in their places.

Here Hughes writes with the force of a good journalist; he is no longer an abstract Negro everyman but a reporter weighing in on the heat and confusion of the time, without too much self-conscious hipster jive.

The novelist Paule Marshall recalls, in her 2009 memoir, “Triangular Road,” a 1965 government-sponsored tour of Europe on which she accompanied Hughes. It was during the heady days of the civil-rights movement. In Paris, a city that Hughes loved—“There you can be whatever you want to be. Totally yourself,” he said—Marshall noticed that when the subject of the movement came up Hughes let others do the talking. He knew what his own struggles had been, and he knew that the present struggle would lead to if not a different day then a different kind of day, one in which erasing lines from one’s own story might make less sense than just saying them. ♦

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Maya Binyam

By Lauren Michele Jackson

Langston Hughes' Impact on the Harlem Renaissance

Hughes not only made his mark in this artistic movement by breaking boundaries with his poetry, he drew on international experiences, found kindred spirits amongst his fellow artists, took a stand for the possibilities of Black art and influenced how the Harlem Renaissance would be remembered.

Hughes stood up for Black artists

George Schuyler, the editor of a Black paper in Pittsburgh, wrote the article "The Negro-Art Hokum" for an edition of The Nation in June 1926.

The article discounted the existence of "Negro art," arguing that African-American artists shared European influences with their white counterparts, and were, therefore, producing the same kind of work. Spirituals and jazz, with their clear links to Black performers, were dismissed as folk art.

Invited to make a response, Hughes penned "The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain." In it, he described Black artists rejecting their racial identity as "the mountain standing in the way of any true Negro art in America." But he declared that instead of ignoring their identity, "We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual, dark-skinned selves without fear or shame."

This clarion call for the importance of pursuing art from a Black perspective was not only the philosophy behind much of Hughes' work, but it was also reflected throughout the Harlem Renaissance.

Some critics called Hughes' poems "low-rate"

Hughes broke new ground in poetry when he began to write verse that incorporated how Black people talked and the jazz and blues music they played. He led the way in harnessing the blues form in poetry with "The Weary Blues," which was written in 1923 and appeared in his 1926 collection The Weary Blues .

Hughes' next poetry collection — published in February 1927 under the controversial title Fine Clothes to the Jew — featured Black lives outside the educated upper and middle classes, including drunks and prostitutes.

A preponderance of Black critics objected to what they felt were negative characterizations of African Americans — many Black characters created by whites already consisted of caricatures and stereotypes, and these critics wanted to see positive depictions instead. Some were so incensed that they attacked Hughes in print, with one calling him "the poet low-rate of Harlem."

But Hughes believed in the worthiness of all Black people to appear in art, no matter their social status. He argued, "My poems are indelicate. But so is life." And though many of his contemporaries might not have seen the merits, the collection came to be viewed as one of Hughes' best. (The poet did end up agreeing that the title — a reference to selling clothes to Jewish pawnbrokers in hard times — was a bad choice.)

Hughes' travels helped give him different perspectives

Hughes came to Harlem in 1921, but was soon traveling the world as a sailor and taking different jobs across the globe. In fact, he spent more time outside Harlem than in it during the Harlem Renaissance.

His journeys, along with the fact that he'd lived in several different places as a child and had visited his father in Mexico, allowed Hughes to bring varied perspectives and approaches to the work he created.

In 1923, when the ship he was working on visited the west coast of Africa, Hughes, who described himself as having "copper-brown skin and straight black hair," had a member of the Kru tribe tell him he was a White man, not a Black one.

Hughes lived in Paris for part of 1924, where he eked out a living as a doorman and met Black jazz musicians. And in the fall of 1924, Hughes saw many white sailors get hired instead of him when he was desperate for a ship to take him home from Genoa, Italy. This led to his plaintive, powerful poem "I, Too," a meditation on the day that such unequal treatment would end.

Hughes and other young Black artists formed a support group

By 1925 Hughes was back in the United States, where he was greeted with acclaim. He was soon attending Lincoln University in Pennsylvania but returned to Harlem in the summer of 1926.

There, he and other young Harlem Renaissance artists like novelist Wallace Thurman, writer Zora Neale Hurston , artist Gwendolyn Bennett and painter Aaron Douglas formed a support group together.

Hughes was part of the group's decision to collaborate on Fire!! , a magazine intended for young Black artists like themselves. Instead of the limits on content they faced at more staid publications like the NAACP 's Crisis magazine, they aimed to tackle a broader, uncensored range of topics, including sex and race.

Unfortunately, the group only managed to put out a single issue of Fire!! . (And Hughes and Hurston had a falling out after a failed collaboration on a play called Mule Bone .) But by creating the magazine, Hughes and the others had still taken a stand for the kind of ideas they wanted to pursue going forward.

He continued to spread the word of the Harlem Renaissance long after it was over

In addition to what he wrote during the Harlem Renaissance, Hughes helped make the movement itself more well known. In 1931, he embarked on a tour to read his poetry across the South. His fee was ostensibly $50, but he would lower the amount, or forego it entirely, at places that couldn't afford it.

His tour and willingness to deliver free programs when necessary helped many get acquainted with the Harlem Renaissance.

And in his autobiography The Big Sea (1940), Hughes provided a firsthand account of the Harlem Renaissance in a section titled "Black Renaissance." His descriptions of the people, art and goings-on would influence how the movement was understood and remembered.

Hughes even played a part in shifting the name for the era from "Negro Renaissance" to "Harlem Renaissance," as his book was one of the first to use the latter term.

Black History

10 Famous Langston Hughes Poems

5 Crowning Achievements of Maya Angelou

Ava DuVernay

Octavia Spencer

Inventor Garrett Morgan’s Lifesaving 1916 Rescue

Get to Know 5 History-Making Black Country Singers

Frederick Jones

Lonnie Johnson

10 Black Authors Who Shaped Literary History

Benjamin Banneker

- A to Z Alphabet Drawing

- Vikram Betal Ki Kahaniya

- Hatim Tai Ki Kahaniya

- Panchatantra Stories in Hindi

- Hatim Tai Story

- Fascinating Stories

- Mysterious Stories

- Prince and Princess story

- Animal Stories

- Famous kids stories

- Tenali Raman Stories

- Hitopadesha Tales

- Bible Stories

- short stories

- Moral Stories

- Panchatantra Stories

- Arabian Nights Stories

- Chinese Mythology

- Roman Mythology

- Egyptian Mythology

- Greek Mythology

- Hindu Mythology

- Norse mythology

- Akbar Birbal Stories

- bedtime stories

- Scary Stories For Kids

- Aesop Fables

- Fairy Tales Stories

- Anime Coloring Pages

- Attack on Titan

- Indian emperors

- Roman emperor

- Russian emperor

- Japanese emperor

- British Emperor

- Egypt Emperor

- Chinese emperor

- Mongol Emperor

- Corporate Sagas

- Essay Writing

- Best Hindi Muhavare

- Paryayvachi Shabd

Printable Eren JAEGER Coloring Pages sheet for Kids | Storiespub

Printable armin arlert coloring pages sheet for kids | storiespub, printable stegosaurus dinosaur coloring pages sheet for kids | storiespub, printable therizinosaurus dinosaur coloring pages sheet for kids | storiespub, from zero to hero: rise to the top of fortnite leaderboards, how to win at among us , mario kart fun game, minecraft: games for kids, how roblox boosts creativity adventures skills in kids, essential guide to the 13 best tips for exercise after childbirth, power of positive parenting: transformative solutions for becoming a better parent, 5 parenting tips for helping your newborn sleep through the night, getting breastfeeding and tattoos: what moms should consider, newborn not pooping but passing gas: tips for parents.

- Biographies

Langston Hughes Biography: Poet, Writer, and Harlem Renaissance Icon

Langston hughes: biography of a literary icon.

In the annals of American literature, few names shine as brightly as Langston Hughes. His life’s narrative weaves through the poetic tapestry of the Harlem Renaissance, his words resonating through generations and his actions echoing the call for social justice. This article takes you on a journey through the life and times of Langston Hughes, a prolific poet , a visionary novelist, and an unyielding advocate for change.

Langston Hughes emerged as a luminary of American literature, etching his name in the chronicles of creativity with an indelible pen. His profound contributions to poetry, fiction, and his unwavering commitment to social activism have left an indomitable mark on the American cultural landscape.

In the pages that follow, we delve into the early chapters of Hughes’ life, tracing the roots of his inspiration, his formative years, and the circumstances that birthed a literary genius. We navigate through the intricate web of his literary career, exploring his celebrated works and their enduring relevance. Moreover, we journey alongside Hughes as he actively engaged in the tumultuous tides of social change, carving his name as a harbinger of civil rights.

This biography strives to uncover the multifaceted layers of Langston Hughes – the poet who ignited imaginations, the novelist who painted vivid narratives, and the activist who championed equality. As we unravel the tapestry of his life, we uncover the profound impact of his words on the Harlem Renaissance and his enduring legacy as a trailblazer in American literature.

Join us in this exploration of Langston Hughes’ life, and be prepared to embark on a voyage through the pages of history, where literature meets activism, and brilliance knows no bounds.

What is the name of Langston Hughes most famous short story?

Langston Hughes is renowned for his impactful contributions to American literature,

particularly in the realm of poetry and prose. While he is widely celebrated for his poetry, his most famous short story is arguably “Salvation.” This poignant narrative is found within his autobiographical essay titled “Salvation” from his collection “The Big Sea,” published in 1940.

In “Salvation,” Hughes recounts a transformative childhood experience he had during a church revival. At the age of twelve, he attended a revivalist meeting with the anticipation of a profound spiritual encounter. The pressure to conform to the congregation’s expectations, particularly from his family, weighed heavily on young Hughes. As the revival reached its climax, Hughes described feeling immense pressure to have a religious experience and see Jesus.

However, when he didn’t experience the anticipated spiritual epiphany, Hughes felt profound disappointment, guilt, and even shame. He explained his predicament as a clash between his own authentic feelings and the external expectations placed upon him. Hughes vividly portrayed the internal struggle of a young boy who grapples with his faith, the influence of society, and the weight of expectations.

“Salvation” remains significant not only for its literary merits but also for its exploration of themes such as identity, societal pressures, and the complexities of faith. Hughes’ ability to depict the inner turmoil of a child in a deeply religious and racially segregated society offers readers a powerful insight into the struggles of African Americans during that era.

This short story stands as a testament to Hughes’ skill in capturing the nuances of the human experience and remains an enduring piece of American literature.

What is unique about Langston Hughes style of writing?

Langston Hughes is celebrated for his unique and influential style of writing, which distinguishes him as a prominent figure in American literature. Several aspects make his writing style distinctive and noteworthy:

- Incorporation of Jazz and Blues: Hughes’ poetry often reflects the rhythms, improvisation, and emotional depth of jazz and blues music. He was a central figure in the Harlem Renaissance, a cultural movement that embraced the vibrancy of African American culture, and his writing echoed the musical traditions of the time. Hughes’ use of syncopated rhythms, repetition, and colloquial language in his poems created a sense of musicality that resonated with readers.

- Authentic Voice of Black America: Hughes’ work authentically captured the voices and experiences of African Americans, particularly those living in urban environments. His poems and stories addressed the challenges, dreams, and aspirations of black people, making his writing a powerful representation of the African American experience during the early 20th century.

- Simple and Accessible Language: Hughes believed in making literature accessible to a broad audience. He used straightforward and everyday language in his works, avoiding overly complex or abstract writing. This accessibility allowed readers from diverse backgrounds to engage with his poetry and prose.

- Social and Political Themes: Hughes’ writing was deeply rooted in social and political issues, especially themes of racial equality, social justice, and the struggles of African Americans. He used his writing as a means of advocacy and empowerment, shedding light on the inequities and prejudices faced by black individuals in America.

- Use of Imagery and Symbolism: Hughes’ poetry often employed vivid imagery and symbolism drawn from both everyday life and African American cultural traditions. He used these elements to convey powerful messages and evoke emotions in his readers. For example, his poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” uses the symbolism of rivers to connect the history and heritage of black people.

- Versatility: Hughes demonstrated versatility in his writing, producing poetry, short stories, essays, plays, and even children’s literature. This wide range of genres allowed him to address a variety of themes and issues, making his work accessible to diverse audiences.

- Celebration of Black Identity: Throughout his writing, Hughes celebrated black identity and culture, countering prevailing stereotypes and negative portrayals of African Americans. His works often emphasized the beauty, resilience, and contributions of black individuals to American society.

In summary, Langston Hughes’ unique writing style is characterized by its musicality, accessibility, authenticity, and its unwavering commitment to addressing social and racial issues. His contributions to American literature continue to be celebrated for their impact and relevance in both literary and cultural contexts.

Personal and Professional Details

Nurturing brilliance: langston hughes’ early life and background.

Langston Hughes, a literary luminary, was born on February 1, 1902, in Joplin, Missouri, a town etched into the tapestry of his life. His birthplace, though rooted in the American Midwest, played a pivotal role in shaping his identity as a prominent figure of the Harlem Renaissance.

The young Langston experienced a childhood marked by turbulence and familial challenges. His parents, James Nathaniel Hughes and Carrie Mercer Langston, separated when he was just a young child. This rupture in his family life cast a shadow, and his mother’s decision to move to Lawrence, Kansas, further compounded the complexity of his early years.

In Lawrence, Langston Hughes was nurtured by his maternal grandmother, Mary Langston, a formidable figure who instilled in him a love for literature and art. It was within the walls of her home that he was first introduced to the world of books, an introduction that would fuel his insatiable appetite for reading and writing. These early encounters with literature, combined with the rich oral storytelling traditions of African American culture, laid the foundation for his future literary endeavors.

As Hughes grew, he encountered the harsh realities of racial prejudice and discrimination, experiences that would profoundly impact his worldview and his literary works. His educational journey took him to several schools, including a brief stay at Columbia University. However, he struggled to find his academic footing, and the siren call of Harlem beckoned him to a vibrant world of artistic expression.

Langston Hughes’ early life and background, marked by a potent mix of familial challenges, literary inspiration, and racial awareness, set the stage for his remarkable journey as a writer, poet, and social advocate. It was a journey that would ultimately transform him into an icon of American literature and civil rights.

Resonating Words: Langston Hughes’ Literary Career and Iconic Works

Langston Hughes’ journey into the realm of literature and poetry was an odyssey sparked by the fiery spirit of the Harlem Renaissance, a cultural and artistic movement that ignited like a beacon during the 1920s. Embracing the vivid pulse of Harlem, Hughes became one of its most prominent voices, leaving an indelible mark on American literature.

In the hallowed streets of New York’s Harlem, Hughes found a canvas for his artistic expression. His initial foray into writing came in the form of poems and essays that captured the essence of African American life, infusing it with a blend of realism and hope. His debut collection, “The Weary Blues” (1926), was a poetic masterpiece that melded the rhythms of blues and jazz with the everyday experiences of Black individuals.

Hughes’ writing was marked by its accessibility and its ability to speak directly to the hearts of his readers. His words painted pictures of resilience, pride, and the longing for a better tomorrow. In works like “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” and “Harlem,” he delved into the rich history and aspirations of his people, weaving together their struggles and dreams with eloquent verse.

Apart from his poetry, Hughes penned poignant short stories and essays that continued to amplify the themes of identity, race, and social justice. “Not Without Laughter” (1930), his first novel, was a literary gem that explored the challenges faced by a young African American boy in a racially divided society.

Hughes’ ability to capture the soul of the African American experience was not limited to his pen alone; he was a prolific essayist and playwright, using these platforms to advocate for social change and challenge the status quo. His impact was not confined to literature; it extended to the broader struggle for civil rights and equality.

As a leading figure of the Harlem Renaissance, Langston Hughes’ contributions to American literature and culture were immeasurable. Through his evocative words, he became a beacon of hope, resilience, and pride for generations of African Americans and readers worldwide.

Sowing the Seeds of Justice: Langston Hughes’ Social Activism

Langston Hughes’ impact extended far beyond the written word; it resonated through his unrelenting commitment to social and political activism. As a passionate advocate for civil rights and social justice, Hughes was not content to merely observe the struggles of his time; he actively engaged in the fight for equality and justice.

Hughes’ involvement in social activism began at an early age. Growing up in a racially segregated America, he witnessed firsthand the injustices suffered by African Americans. These experiences lit a fire within him, sparking a lifelong dedication to addressing these inequities through his art and activism.

During the height of the Harlem Renaissance, Hughes used his literary platform to amplify the voices of African Americans and shed light on the issues they faced. His poetry, essays, and articles tackled subjects such as racial discrimination, segregation, and the socioeconomic challenges of Black communities. One of his most iconic poems, “Let America Be America Again,” resonated with its call for equality and justice, echoing the aspirations of marginalized communities.

Hughes’ commitment to social justice went beyond his pen; he was an active participant in the Civil Rights Movement. He used his influence to support the cause, attending rallies, marches, and protests alongside other civil rights leaders. His powerful poem “Ballad of Roosevelt” was a direct response to the racism faced by African American soldiers during World War II, shedding light on the hypocrisy of fighting for freedom abroad while facing discrimination at home.

Furthermore, Hughes’ involvement in international activism was notable. He traveled extensively, using his experiences to draw parallels between the struggles of African Americans and oppressed people worldwide. His work as a journalist during the Spanish Civil War and his visits to the Soviet Union allowed him to witness various forms of societal change and inspired his commitment to social justice.

Langston Hughes’ legacy is a testament to the power of art and activism to effect change. Through his relentless pursuit of civil rights and social justice, he paved the way for future generations of activists, leaving an enduring mark on the fight for equality and human rights. His life’s work stands as a reminder that words, when wielded with purpose, can be a catalyst for transformative change.

Langston Hughes: An Enduring Literary Legacy

Langston Hughes’ impact on American literature is immeasurable, and his legacy continues to thrive long after his passing. As one of the most influential figures of the Harlem Renaissance, Hughes left an indelible mark on the literary landscape, inspiring countless writers, poets, and activists to follow in his footsteps.

One of Hughes’ most significant contributions was his ability to capture the essence of Black life in America. Through his poetry, short stories, and essays, he painted vivid pictures of the African American experience, shedding light on both the joys and struggles of Black communities. His work resonated deeply with readers of all backgrounds, forging connections and fostering understanding during a time of racial tension and segregation.

Hughes’ poetry, in particular, is celebrated for its accessibility and emotional depth. His poems often addressed universal themes such as dreams, aspirations, and the human condition, making them relatable to a wide audience. His collection “The Weary Blues” earned him critical acclaim and marked the beginning of a prolific career that would span decades.

The impact of Langston Hughes extends far beyond his writing. His unwavering commitment to civil rights and social justice laid the foundation for future generations of activists. He used his literary prowess to advocate for equality, making him a beacon of hope during the Civil Rights Movement. His poems, such as “I, Too, Sing America,” served as anthems of resistance, inspiring change and challenging the status quo.

Hughes’ influence can be seen in the work of numerous writers and poets who followed in his footsteps. His commitment to representing the African American experience authentically paved the way for writers like Maya Angelou, Toni Morrison, and Alice Walker, who continued to amplify Black voices in literature.

Throughout his lifetime, Hughes received numerous awards and honors, including the NAACP’s Spingarn Medal and the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for lifetime achievement. These accolades recognized not only his literary excellence but also his tireless efforts to champion civil rights and social justice.

Langston Hughes’ legacy as a literary luminary and social activist remains undeniably significant. His words continue to resonate with readers of all backgrounds, and his impact on American literature and the fight for equality endures as a testament to the power of art to effect change. Hughes’ work reminds us that literature has the capacity to illuminate the human experience and serve as a catalyst for social progress.

Langston Hughes: The Man Behind the Words

Langston Hughes, celebrated poet and activist, led a life as rich and diverse as the themes he explored in his works. Beyond the ink and paper, his personal life was marked by fascinating relationships, unique experiences, and a tireless commitment to his craft and ideals.

Hughes was born in Joplin, Missouri, in 1902. His parents’ separation when he was a child had a profound impact on him, sparking a sense of displacement that would become a recurring theme in his writing. Raised primarily by his grandmother in Lawrence, Kansas, Hughes found solace in literature and began to develop his passion for poetry.

As he pursued higher education, Hughes encountered both discrimination and encouragement. He attended Columbia University briefly but left due to racial prejudice. His experiences there and his travels to various countries, including Mexico and France, broadened his horizons and deepened his appreciation for the global Black experience.

Hughes’ personal life was characterized by a network of relationships that fueled his creativity. His close friendship with Zora Neale Hurston, another prominent figure of the Harlem Renaissance, resulted in collaborative works that celebrated African American culture. He also formed a lifelong bond with Carl Van Vechten, a white photographer and patron of the arts, who supported his career and introduced him to influential figures in the literary world.

Throughout his life, Hughes maintained both romantic and platonic relationships with people of various backgrounds. His exploration of love, identity, and desire can be seen in his poetry and fiction. However, Hughes was discreet about his private life, and the specifics of his romantic relationships remain a subject of historical curiosity and speculation.

Langston Hughes’ extensive travels, including his years living in Harlem during the cultural and artistic explosion of the Harlem Renaissance, profoundly influenced his work. The vibrancy of this era, coupled with his interactions with fellow writers, musicians, and intellectuals, informed his poetry and prose, creating a body of work that continues to resonate with readers today.

In conclusion, Langston Hughes’ personal life was marked by the same dynamism and diversity that characterized his literary contributions. His relationships, travels, and unique experiences all played a role in shaping his perspective and enriching his creative endeavors. Langston Hughes, the man behind the words, remains an enduring figure in American literature and history.

In the tapestry of American literature and civil rights, Langston Hughes emerges as a luminary figure whose brilliance continues to shine through the corridors of history. His life was a symphony of words and actions, a testament to the power of poetry and social activism. As we trace the contours of his remarkable journey, we find a man whose legacy transcends the confines of time.

Langston Hughes’ early life, shaped by the intricacies of racial identity and a relentless passion for literature, sowed the seeds of his groundbreaking work. Born in Joplin, Missouri, his odyssey through different places and experiences enriched his perspective, painting the canvas of his words with vibrant strokes of universal truth.

Throughout his career, Hughes wore many hats – poet, essayist, novelist, playwright – each one adding a layer of depth to his literary tapestry. His words were a clarion call for equality and justice, resonating with the rhythm of a generation’s hopes and aspirations. His connection with the Harlem Renaissance marked a pivotal moment in his life, and his collaborations with other luminaries such as Zora Neale Hurston and Carl Van Vechten bore testament to the synergy of artistic souls.

But Hughes was not just a poet of words; he was a poet of the people. His commitment to civil rights was unwavering, and his writings became a powerful tool in the fight for racial equality. His travels, friendships, and loves all found expression in his verses, adding a human dimension to his work that endeared him to countless readers.

Today, Langston Hughes’ legacy lives on, an eternal flame illuminating the path of those who dare to dream and hope for a better world. His words continue to inspire, challenging us to confront the inequities of our time and champion the cause of justice. In the annals of American culture, Langston Hughes stands as an indomitable force, reminding us that literature, when infused with purpose, can change the world.

Hey kids, how much did you like Langston Hughes: Biography of a Literary Icon? Please share your view in the comment box. Also, please share this story with your friends on social media so they can also enjoy it, and for more such biography , please bookmark storiespub.com.

Suggested Biography –

- Bonnie Garmus Biography

Langston Hughes FAQs

Who was langston hughes.

Langston Hughes was a prominent American poet, writer, and social activist known for his contributions to the Harlem Renaissance and his impactful writings on racial and social issues.

What is Langston Hughes most famous for?

Langston Hughes is most famous for his poetry and essays, particularly for poems like "The Negro Speaks of Rivers" and his role in the Harlem Renaissance.

What is the Harlem Renaissance, and how was Langston Hughes involved?

The Harlem Renaissance was a cultural and artistic movement celebrating African American culture in the 1920s. Langston Hughes was a central figure, known for his poetry and writings that captured the spirit of this movement.

What is Langston Hughes' writing style characterized by?

Langston Hughes' writing style is characterized by the use of jazz and blues rhythms in his poetry, accessible language, and a focus on social and racial themes.

What are some of Langston Hughes' famous works?

Some of his famous works include "The Weary Blues" (a poetry collection), "The Ways of White Folks" (a short story collection), and "Montage of a Dream Deferred" (a poetry collection).

Was Langston Hughes involved in the Civil Rights Movement?