An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Adv Med Educ Prof

- v.4(4); 2016 Oct

Effective Teaching Methods in Higher Education: Requirements and Barriers

Nahid shirani bidabadi.

1 Psychology and Educational Sciences School, University of Isfahan, Isfahan, Iran;

AHMMADREZA NASR ISFAHANI

Amir rouhollahi.

2 Department of English, Management and Information School, Isfahan University of Medical Science, Isfahan, Iran;

ROYA KHALILI

3 Quality Improvement in Clinical Education Research Center, Education Development Center, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

Introduction:

Teaching is one of the main components in educational planning which is a key factor in conducting educational plans. Despite the importance of good teaching, the outcomes are far from ideal. The present qualitative study aimed to investigate effective teaching in higher education in Iran based on the experiences of best professors in the country and the best local professors of Isfahan University of Technology.

This qualitative content analysis study was conducted through purposeful sampling. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with ten faculty members (3 of them from the best professors in the country and 7 from the best local professors). Content analysis was performed by MAXQDA software. The codes, categories and themes were explored through an inductive process that began from semantic units or direct quotations to general themes.

According to the results of this study, the best teaching approach is the mixed method (student-centered together with teacher-centered) plus educational planning and previous readiness. But whenever the teachers can teach using this method confront with some barriers and requirements; some of these requirements are prerequisite in professors' behavior and some of these are prerequisite in professors’ outlook. Also, there are some major barriers, some of which are associated with the professors’ operation and others are related to laws and regulations. Implications of these findings for teachers’ preparation in education are discussed.

Conclusion:

In the present study, it was illustrated that a good teaching method helps the students to question their preconceptions, and motivates them to learn, by putting them in a situation in which they come to see themselves as the authors of answers, as the agents of responsibility for change. But training through this method has some barriers and requirements. To have an effective teaching; the faculty members of the universities should be awarded of these barriers and requirements as a way to improve teaching quality. The nationally and locally recognized professors are good leaders in providing ideas, insight, and the best strategies to educators who are passionate for effective teaching in the higher education. Finally, it is supposed that there is an important role for nationally and locally recognized professors in higher education to become more involved in the regulation of teaching rules.

Introduction

Rapid changes of modern world have caused the Higher Education System to face a great variety of challenges. Therefore, training more eager, thoughtful individuals in interdisciplinary fields is required ( 1 ). Thus, research and exploration to figure out useful and effective teaching and learning methods are one of the most important necessities of educational systems ( 2 ); Professors have a determining role in training such people in the mentioned field ( 3 ). A university is a place where new ideas germinate; roots strike and grow tall and sturdy. It is a unique space, which covers the entire universe of knowledge. It is a place where creative minds converge, interact with each other and construct visions of new realities. Established notions of truth are challenged in the pursuit of knowledge. To be able to do all this, getting help from experienced teachers can be very useful and effective.

Given the education quality, attention to students’ education as a main product that is expected from education quality system is of much greater demand in comparison to the past. There has always been emphasis on equal attention to research and teaching quality and establishing a bond between these two before making any decision; however, studies show that the already given attention to research in universities does not meet the educational quality requirements.

Attention to this task in higher education is considered as a major one, so in their instruction, educators must pay attention to learners and learning approach; along with these two factors, the educators should move forward to attain new teaching approaches. In the traditional system, instruction was teacher-centered and the students’ needs and interests were not considered. This is when students’ instruction must change into a method in which their needs are considered and as a result of the mentioned method active behavior change occurs in them ( 4 ). Moreover, a large number of graduated students especially bachelor holders do not feel ready enough to work in their related fields ( 5 ). Being dissatisfied with the status quo at any academic institution and then making decision to improve it require much research and assistance from the experts and pioneers of that institute. Giving the aforementioned are necessary, especially in present community of Iran; it seems that no qualitative study has ever been carried out in this area drawing on in-depth reports of recognized university faculties; therefore, in the present study the new global student-centered methods are firstly studied and to explore the ideas of experienced university faculties, some class observations and interviews were done. Then, efficient teaching method and its barriers and requirements were investigated because the faculty ideas about teaching method could be itemized just through a qualitative study.

The study was conducted with a qualitative method using content analysis approach. The design is appropriate for this study because it allows the participants to describe their experiences focusing on factors that may improve the quality of teaching in their own words. Key participants in purposeful sampling consist of three nationally recognized professors introduced based on the criteria of Ministry of Science, Research and Technology (based on education, research, executive and cultural qualifications) and seven other locally recognized professors according to Isfahan University of Technology standards and students votes. The purposive sampling continued until the saturation was reached, i.e. no further information was obtained for the given concept. All the participants had a teaching experience of above 10 years ( Table 1 ). They were first identified and after making appointments, they were briefed about the purpose of the study and they expressed their consent for the interview to be performed. The lack of female nationally recognized professors among respondents (due to lack of them) are restrictions of this research.

The participants’ characteristics

The data were collected using semi-structured in-depth interviews. Interviews began with general topics, such as “Talk about your experiences in effective teaching” and then the participants were asked to describe their perceptions of their expertise. Probing questions were also used to deeply explore conditions, processes, and other factors that the participants recognized as significant. The interview process was largely dependent on the questions that arose in the interaction between the interviewer and interviewees.

In the process of the study, informed consent was obtained from all the participants and they were ensured of the anonymity of their responses and that the audio files will be removed after use; then, after obtaining permission from the participants, the interview was recorded and transcribed verbatim immediately. The interviews were conducted in a private and quiet place and in convenient time. Then, verification of documents and coordination for subsequent interviews were done. The interviews lasted for one hour on average and each interview was conducted in one session with the interviewer’s notes or memos and field notes. Another method of data collection in this study was an unstructured observation in the educational setting. The investigator observed the method of interactions among faculty members and students. The interviews were conducted from November 2014 to April 2015. Each participant was interviewed for one or two sessions. The mean duration of the interviews was 60 minutes. To analyze the data, we used MAXQDA software (version 10, package series) for indexing and charting. Also, we used qualitative content analysis with a conventional approach to analyze the data. The data of the study were directly collected from the experiences of the study participants. The codes, categories and themes were explored through an inductive process, in which the researchers moved from specific to general. The consequently formulated concepts or categories were representative of the participants’ experiences. In content analysis at first, semantic units should be specified, and then the related codes should be extracted and categorized based on their similarities. Finally, in the case of having a high degree of abstraction, the themes can be determined. In the conventional approach, the use of predetermined classes is avoided and classes and their names are allowed to directly come out of the data. To do so, we read the manuscripts and listened to the recorded data for several times until an overall sense was attained. Then, the manuscript was read word by word and the codes were extracted. At the same time, the interviews were continued with other participants and coding of the texts was continued and sub-codes were categorized within the general topics. Then, the codes were classified in categories based on their similarities ( 6 ). Finally, by providing a comprehensive description about the topics, participants, data collection and analysis procedures and limitations of the study, we intend to create transferability so that other researchers clearly follow the research process taken by the researchers.

To improve the accuracy and the rigor of the findings, Lincoln and Cuba’s criteria, including credibility, dependability, conformability, and transferability, were used ( 7 ). To ensure the accuracy of the data, peer review, the researchers’ acceptability, and the long and continuing evaluation through in-depth, prolonged, and repeated interviews and the colleague’s comments must be used ( 8 ). In addition, the findings were repeatedly assessed and checked by supervisors (expert checking) ( 9 ). In this research, the researcher tried to increase the credibility of the data by keeping prolonged engagement in the process of data collection. Then, the accuracy of data analysis was confirmed by one specialist in the field of qualitative research and original codes were checked by some participants to compare the findings with the participants’ experiences. To increase the dependability and conformability of data, maximum variation was observed in the sampling. In addition, to increase the power of data transferability, adequate description of the data was provided in the study for critical review of the findings by other researchers.

Ethical considerations

The aim of the research and interview method was explained to the participants and in the process of the study, informed consent was obtained from all the participants and they were ensured of the anonymity of their responses and that audio files were removed after use. Informed consent for interview and its recording was obtained.

The mean age of faculty members in this study was 54.8 years and all of them were married. According to the results of the study, the best teaching approach was the mixed method one (student-centered with teacher-centered) plus educational planning and previous readiness. Meaning units expressed by professors were divided into 19 codes, 4 categories and 2 themes. In the present study, regarding the Effective Teaching Method in Higher Education, Requirements and Barriers, the experiences and perceptions of general practitioners were explored. As presented in Table 2 , according to data analysis, two themes containing several major categories and codes were extracted. Each code and category is described in more details below.

Examples of extracting codes, categories and themes from raw data

New teaching methods and barriers to the use of these methods

Teachers participating in this study believed that teaching and learning in higher education is a shared process, with responsibilities on both student and teacher to contribute to their success. Within this shared process, higher education must engage the students in questioning their preconceived ideas and their models of how the world works, so that they can reach a higher level of understanding. But students are not always equipped with this challenge, nor are all of them driven by a desire to understand and apply knowledge, but all too often aspire merely to survive the course, or to learn only procedurally in order to get the highest possible marks before rapidly moving on to the next subject. The best teaching helps the students to question their preconceptions, and motivates them to learn, by putting them in a situation in which their existing model does not work and in which they come to see themselves as authors of answers, as agents of responsibility for change. That means, the students need to be faced with problems which they think are important. Also, they believed that most of the developed countries are attempting to use new teaching methods, such as student-centered active methods, problem-based and project-based approaches in education. For example, the faculty number 3 said:

“In a project called EPS (European Project Semester), students come together and work on interdisciplinary issues in international teams. It is a very interesting technique to arouse interest, motivate students, and enhance their skills (Faculty member No. 3).”

The faculty number 8 noted another project-based teaching method that is used nowadays especially to promote education in software engineering and informatics is FLOSS (Free/Liber Open Source Software). In recent years, this project was used to empower the students. They will be allowed to accept the roles in a project and, therefore, deeply engage in the process of software development.

In Iran, many studies have been conducted about new teaching methods. For example, studies by Momeni Danaie ( 10 ), Noroozi ( 11 ), and Zarshenas ( 12 ), have shown various required methods of teaching. They have also concluded that pure lecture, regardless of any feedback ensuring the students learning, have lost their effectiveness. The problem-oriented approach in addition to improving communication skills among students not only increased development of critical thinking but also promoted study skills and an interest in their learning ( 12 ).

In this study, the professors noted that there are some barriers to effective teaching that are mentioned below:

As to the use of new methods of training such as problem-based methods or project-based approach, faculty members No. 4 and 9 remarked that "The need for student-centered teaching is obvious but for some reasons, such as the requirement in the teaching curriculum and the large volume of materials and resources, using these methods is not feasible completely" (Faculty member No. 9).

"If at least in the form of teacher evaluation, some questions were allocated to the use of project-based and problem-based approaches, teachers would try to use them further" (Faculty member No. 2).

The faculty members No. 6 and 7 believed that the lack of motivation in students and the lack of access to educational assistants are considered the reasons for neglecting these methods.

"I think one of the ways that can make student-centered education possible is employing educational assistants (Faculty member No. 6).”

"If each professor could attend crowded classes with two or three assistants, they could divide the class into some groups and assign more practical teamwork while they were carefully supervised (Faculty member No. 7).”

Requirements related to faculty outlook in an effective teaching

Having a successful and effective teaching that creates long-term learning on the part of the students will require certain feelings and attitudes of the teachers. These attitudes and emotions strongly influence their behavior and teaching. In this section, the attitudes of successful teachers are discussed.

Coordination with the overall organizational strategies will allow the educational system to move toward special opportunities for innovation based on the guidelines ( 13 ). The participants, 4, 3, 5 and 8 know that teaching effectively makes sense if the efforts of the professors are aligned with the goals of university.

"If faculty members know themselves as an inseparable part of the university, and proud of their employment in the university and try to promote the aim of training educated people with a high level of scientific expertise of university, it will become their goal, too. Thus, they will try as much as possible to attain this goal" (Faculty member No.9).

When a person begins to learn, according to the value of hope theory, he must feel this is an important learning and believe that he will succeed. Since the feeling of being successful will encourage individuals to learn, you should know that teachers have an important role in this sense ( 14 ). The interviewees’ number 1, 2, 3 and 10 considered factors like interest in youth, trust in ability and respect, as motivating factors for students.

Masters 7 and 8 signified that a master had a holistic and systematic view, determined the position of the teaching subject in a field or in the entire course, know general application of issues and determines them for students, and try to teach interdisciplinary topics. Interviewee No. 5 believed that: "Masters should be aware of the fact that these students are the future of the country and in addition to knowledge, they should provide them with the right attitude and vision" (Faculty member No.5).

Participants No. 2, 4 and 8 considered the faculty members’ passion to teach a lesson as responsible and believed that: "If the a teacher is interested in his field, he/she devotes more time to study the scriptures of his field and regularly updates his information; this awareness in his teaching and its influence on students is also very effective" (Faculty member No. 8).

Requirements related to the behavior and performance of faculty members in effective teaching

Teachers have to focus on mental differences, interest, and sense of belonging, emotional stability, practical experience and scientific level of students in training. Class curriculum planning includes preparation, effective transition of content, and the use of learning and evaluating teaching ( 15 ).

Given the current study subjects’ ideas, the following functional requirements for successful teaching in higher education can be proposed.

According to Choi and Pucker, the most important role of teachers is planning and controlling the educational process for students to be able to achieve a comprehensive learning ( 16 ).

"The fact that many teachers don’t have a predetermined plan on how to teach, and just collect what they should teach in a meeting is one reason for the lack of creativity in teaching" Faculty member No.4).

Klug and colleagues in an article entitled “teaching and learning in education” raise some questions and want the faculty members to ask themselves these questions regularly.

1- How to increase the students' motivation.

2- How to help students feel confident in solving problems.

3- How to teach students to plan their learning activities.

4- How to help them to carry out self-assessment at the end of each lesson.

5- How to encourage the students to motivate them for future work.

6- How I can give feedback to the students and inform them about their individual learning ( 14 ).

Every five faculty members who were interviewed cited the need to explain the lessons in plain language, give feedback to students, and explain the causes and reasons of issues.

"I always pay attention to my role as a model with regular self-assessment; I'm trying to teach this main issue to my students" (Faculty member No. 9).

Improving the quality of learning through the promotion of education, using pre-organizers and conceptual map, emphasizing the student-centered learning and developing the skills needed for employment are the strategies outlined in lifelong learning, particularly in higher education ( 17 ).

"I always give a five to ten-minute summary of the last topic to students at first; if possible, I build up the new lesson upon the previous one" (Faculty member No. 4).

The belief that creative talent is universal and it will be strengthened with appropriate programs is a piece of evidence to prove that innovative features of the programs should be attended to continually ( 18 ). Certainly, in addition to the enumerated powers, appropriate fields should be provided to design new ideas with confidence and purposeful orientation. Otherwise, in the absence of favorable conditions and lack of proper motivations, it will be difficult to apply new ideas ( 19 ). Teacher’s No. 3, 5 and 7 emphasized encouraging the students for creativity: "I always encourage the students to be creative when I teach a topic; for example, after teaching, I express some vague hints and undiscovered issues and ask them what the second move is to improve that process" (Faculty member No.3).

Senior instructors try to engage in self-management and consultation, tracking their usage of classroom management skills and developing action plans to modify their practices based on data. Through consultation, instructors work with their colleagues to collect and implement data to gauge the students’ strengths and weaknesses, and then use protocols to turn the weaknesses into strengths. The most effective teachers monitor progress and assess how their changed practices have impacted the students’ outcomes ( 20 ).

"It is important that what is taught be relevant to the students' career; however, in the future with the same information they have learned in university, they want to work in the industry of their country" (Faculty member No.1).

Skills in documenting the results of the process of teaching-learning cannot only facilitate management in terms of studying the records, but also provides easier access to up to date information ( 21 ). Faculty members No. 7 and 3 stressed the need for documenting learning experiences by faculty.

"I have a notebook in my office that I usually refer to after each class. Then, I write down every successful strategy that was highly regarded by students that day" (Faculty member No.3).

Developing a satisfactory interaction with students

To connect with students and impact their lives personally and professionally, teachers must be student-centered and demonstrate respect for their background, ideologies, beliefs, and learning styles. The best instructors use differentiated instruction, display cultural sensitivity, accentuate open communication, offer positive feedback on the students’ academic performance ( 20 ), and foster student growth by allowing them to resubmit assignments prior to assigning a grade ( 22 ).

"I pay attention to every single student in my class and every time when I see a student in class is not focused on a few consecutive sessions, I ask about his lack of focus and I help him solve his problem" (Faculty member No. 5).

The limitation in this research was little access to other nationally recognized university faculty members; also their tight schedule was among other limitations in this study that kept us several times from interviewing such faculties. To overcome such a problem, they were briefed about the importance of this study and then some appointments were set with them.

This study revealed the effective teaching methods, requirements and barriers in Iranian Higher Education. Teachers participating in this study believed that teaching and learning in higher education is a shared process, with responsibilities on both student and teacher to contribute to their success. Within this shared process, higher education must engage the students in questioning their preconceived ideas and their models of how the world works, so that they can reach a higher level of understanding. They believed that to grow successful people to deal with the challenges in evolving the society, most developed countries are attempting to use new teaching methods in higher education. All these methods are student-centered and are the result of pivotal projects. Research conducted by Momeni Danaei and colleagues also showed that using a combination of various teaching methods together will lead to more effective learning while implementing just one teaching model cannot effectively promote learning ( 10 ). However, based on the faculty member’s experiences, effective teaching methods in higher education have some requirements and barriers.

In this study, barriers according to codes were divided two major categories: professor-related barriers and regulation-related ones; for these reasons, the complete use of these methods is not possible. However, teachers who are aware of the necessity of engaging the student for a better understanding of their content try to use this method as a combination that is class speech presentation and involving students in teaching and learning. This result is consistent with the research findings of Momeni Danaei and colleagues ( 10 ), Zarshenas et al. ( 12 ) and Noroozi ( 11 ).

Using student-centered methods in higher education needs some requirements that according to faculty members who were interviewed, and according to the codes, such requirements for effective teaching can be divided into two categories: First, things to exist in the outlook of faculties about the students and faculties' responsibility towards them, to guide them towards effective teaching methods, the most important of which are adaptation to the organizational strategies, interest in the students and trust in their abilities, systemic approach in higher education, and interest in their discipline.

Second, the necessary requirements should exist in the faculties’ behavior to make their teaching methods more effective. This category emerged from some codes, including having lesson plan; using appropriate educational strategies and metacognition training and self-assessment of students during teaching; using concept and pre-organizer maps in training, knowledge; and explaining how to resolve problems in professional career through teaching discussion, documenting of experience and having satisfactory interaction with the students. This result is consistent with the findings of Klug et al., Byun et al., and Khanyfr et al. ( 14 , 17 , 18 ).

In addition and according to the results, we can conclude that a major challenge for universities, especially at a time of resource constraints, is to organize teaching so as to maximize learning effectiveness. As mentioned earlier, a major barrier to change is the fact that most faculty members are not trained for their teaching role and are largely ignorant of the research literature on effective pedagogy. These findings are in agreement with the research of Knapper, indicating that the best ideas for effective teaching include: Teaching methods that focus on the students’ activity and task performance rather than just acquisition of facts; Opportunities for meaningful personal interaction between the students and teachers; Opportunities for collaborative team learning; More authentic methods of assessment that stress task performance in naturalistic situations, preferably including elements of peer and self-assessment; Making learning processes more explicit, and encouraging the students to reflect on the way they learn; Learning tasks that encourage integration of information and skills from different fields ( 23 ).

In the present study, it was illustrated that a good teaching method helps the students to question their preconceptions, and motivates them to learn, by putting them in a situation in which they come to see themselves as the authors of answers and the agents of responsibility for change. But whenever the teachers can teach by this method, they are faced with some barriers and requirements. Some of these requirements are prerequisite of the professors' behavior and some of these are prerequisite of the professors’ outlook. Also, there are some major barriers some of which are associated with the professors’ behavior and others are related to laws and regulations. Therefore, to have an effective teaching, the faculty members of universities should be aware of these barriers and requirements as a way to improve the teaching quality.

Effective teaching also requires structural changes that can only be brought about by academic leaders. These changes include hiring practices reward structures that recognize the importance of teaching expertise, quality assurance approaches that measure learning processes, outcomes in a much more sophisticated way than routine methods, and changing the way of attaining university accreditation.

The nationally and locally recognized professors are good leaders in providing ideas, insight, and the best strategies to educators who are passionate for effective teaching in the higher education. Finally, it is supposed that there is an important role for nationally and locally recognized professors in higher education to become more involved in the regulation of teaching rules. This will help other university teachers to be familiar with effective teaching and learning procedures. Therefore, curriculum planners and faculty members can improve their teaching methods.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank all research participants of Isfahan University of Technology (faculties) who contributed to this study and spent their time to share their experiences through interviews.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

Advertisement

Effective instructional strategies and technology use in blended learning: A case study

- Open access

- Published: 08 June 2021

- Volume 26 , pages 6143–6161, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Meina Zhu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5901-9924 1 ,

- Sarah Berri 1 &

- Ke Zhang 1

22k Accesses

12 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This case study explored effective instructional strategies and technology use in blended learning (BL) in a graduate course in the USA. Varied forms of data were collected, including (1) semi-structured interviews with students, (2) mid-term and final course evaluations, (3) two rounds of online debates, (4) four weeks of online reflection journals, and (5) the instructor’s reflections. Thematical analysis and descriptive statistics were conducted to analyze qualitative and quantitative data respectively. Multiple methods were employed to establish trustworthiness of the study. Effective and ineffective instructional strategies and technology uses were identified in BL. The findings indicated that students valued real-time interactions with peers and the instructor. However, inappropriate asynchronous discussions were considered less effective in BL. In addition, immediate feedback from peers and the instructor motivated learners and improved the quality of their work. Learning technologies played a critical role in BL, but the use of learning technologies should be simplified and streamlined. Technical support was essential to reduce learners’ cognitive load.

Similar content being viewed by others

Adoption of online mathematics learning in Ugandan government universities during the COVID-19 pandemic: pre-service teachers’ behavioural intention and challenges

Geofrey Kansiime & Marjorie Sarah Kabuye Batiibwe

Online learning in higher education: exploring advantages and disadvantages for engagement

Amber D. Dumford & Angie L. Miller

A Systematic Review of Research on Personalized Learning: Personalized by Whom, to What, How, and for What Purpose(s)?

Matthew L. Bernacki, Meghan J. Greene & Nikki G. Lobczowski

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

An increasing number of universities are adopting blended learning (BL) (Porter et al., 2014 ), which combines face-to-face (F2F) instruction with online instruction (Bonk & Graham, 2006 ; Voos, 2003 ). As a paradigm shift from teaching to learning (Nunan et al., 2000 ), researchers predicted that BL has the potential to be widely adopted in higher education (Norberg et al., 2011 ) and to transform F2F learning (Donnelly, 2010 ). Currently, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, BL is likely to increase in various forms around the world (Kim, 2020 ).

Research has found a range of positive effects of BL (Means et al., 2013 ; Vella et al., 2016 ), such as engaging learners (Henrie et al., 2015 ; Owston et al., 2013 ), reducing dropout rates (López-Pérez et al., 2011 ), enhancing knowledge construction and problem-solving abilities (Bridges et al., 2015 ), improving performance (Deschacht & Goeman, 2015 ; Shea & Bidjerano, 2014 ), increasing attendance and satisfaction (Stockwell et al., 2015 ), and providing a strong sense of community in the learning experiences (Rovai & Jordan, 2004 ). Researchers have also found that effective blended course design and instruction could make students feel connected with others (e.g., Cocquyt et al., 2017 ). In addition to the benefits of BL, some research focused on the affordance of the emerging technologies for collaborative learning (Gan et al., 2015 ). However, studies also show that technologies could hinder teaching and learning if not used properly (Bower et al., 2015 ; Park & Bonk, 2007 ). Understanding the specific strategies and technology use will be critical to the design of effective BL.

Despite its proven and potential advantages, more research on effective instructional strategies in BL is imperative. This study investigated both instructional strategies and technology uses in BL in a graduate course in the USA. It intended to inform researchers and practitioners of effective instructional strategies in BL and to help leverage learning technologies in blended courses.

2 Literature review

2.1 blended learning.

BL is a type of delivery mode that integrates both F2F and online instructions (Bonk & Graham, 2006 ; Graham, 2004 ). Online instruction through synchronous or asynchronous communications is supported with emerging learning technologies (Norberg et al., 2011 ), so, to succeed in such an environment, students must be comfortable using the technologies (Holley & Oliver, 2010 ; Song et al., 2004 ). However, not all students are familiar with all learning technologies, thus technical support is essential in BL (Graham, 2004 ; Johnson, 2017 ). In addition, scholars (e.g., Lee et al., 2011 ) believe that effective technical support can positively influence students’ learning satisfaction. Students who are more familiar with learning technologies are also found more active in learning activities (Min, 2010 ).

Research has identified diverse advantages of BL. For example, Graham and colleagues identified three primary benefits of BL: (1) enhancing pedagogy, (2) increasing access and flexibility, and (3) improving cost-efficiency (Graham et al., 2005 ). Research indicates that BL increases learning effectiveness, efficiency, satisfaction (Garrison & Kanuka, 2004 ; Graham, 2013 ; Martínez-Caro & Campuzano-Bolarin, 2011 ), performance (Boyle et al., 2003 ; Lim & Morris, 2009 ), engagement (Owston et al., 2013 ), attendance (Stockwell et al., 2015 ), and fosters collaboration (So & Brush, 2008 ). For instance, research conducted at the University of Central Florida has found that the success rates for BL were higher than either fully traditional face-to-face or completely online courses (Graham, 2013 ). Some studies also suggest that BL improved students’ knowledge construction and problem-solving skills (Bridges et al., 2015 ). Second, BL has great potentials to increase access and flexibility (Graham, 2006 ; Moskal et al., 2013 ). With flexibility in time and location for learning (King & Arnold, 2012 ), BL potentially increases access to education (Shea, 2007 ). Last, BL may improve the cost-effectiveness of education (Graham, 2013 ), as it reduces operational costs compared to traditional on-campus learning (Vaughan, 2007 ; Woltering et al., 2009 ).

2.2 Interactions and discussions in BL

Learning interactions are essential for knowledge acquisition and skill development (Barker, 1994 ). Moore ( 1989 ) categorized three types of interactions, those amongst learners, between learner and instructor, and learner-content interactions. Learner-learner interactions may stimulate two-way collaborative learning (Kuo & Belland, 2016 ; Moore, 1989 ), and they are particularly important in online courses (Anderson, 2008 ). Learner-instructor interactions streamline communications between learner and instructor and also facilitates the delivery of instructions, guidance, and support to learners (Kuo & Belland, 2016 ; Moore, 1989 ). Learner-content interaction is typically one-way communication, in which learners interact with the content (Kuo & Belland, 2016 ; Moore, 1989 ), although emerging technologies have made it possible to dynamically generate highly customized content or learning experiences. Students can interact with peers, instructors, and learning content in BL (Moore, 1989 ), especially through interactive technologies (Anderson, 2008 ) and appropriate pedagogies.

One of the strengths of BL is that both online and face-to-face (F2F) sessions may facilitate ample opportunities for interactions (Fryer & Bovee, 2018 ; Johnson, 2017 ). Evidently, interactions are positively related to learning outcomes and learners’ satisfaction in BL (Kang & Im, 2013 ; Kuo & Belland, 2016 ; Kurucay & Inan, 2017 ; Wei et al., 2015 ). Particularly, learner-learner interaction is important for their achievement and sense of belongings (Bernard et al., 2009 ; Diep et al., 2017 ), which strengthens a sense of community (Lidstone & Shield, 2010 ).

Successful discussions serve as a powerful instructional strategy in higher education (Ellis & Goodyear, 2010 ; Rovai, 2007 ), as peer discussions encourage students to construct knowledge through active communications (Hamann et al., 2012 ; Huerta, 2007 ; Vonderwell, 2003 ). While learners demanding emotional or cognitive support would require timely and considerate facilitations from the instructor in BL (Butz et al., 2014 ; Szeto & Cheng, 2016 ). Discussions in BL could happen in either F2F or online sessions or continue in both settings. In F2F discussions, learners could share ideas and receive an immediate response; whereas, online discussions added advantages that could not be achieved in F2F settings (Joubert & Wishart, 2012 ; Richardson & Ice, 2010 ). For example, in online asynchronous discussions, students have more time to read, digest, and reflect upon learning materials, which promotes critical thinking (Putman et al., 2012 ; Williams & Lahman, 2011 ). However, online discussions, if without sufficient support or stimulus, can be superficial or wordy yet without depth (Angeli et al., 2003 ; Wallace, 2003 ). Therefore, researchers have proposed different strategies to organize discussions in F2F or online instructions (Guiller et al., 2008 ). Darabi and Jin ( 2013 ), for example, suggested sharing example posts with students for discussions. However, how to increase interaction and promote effective discussion is still an open question.

2.3 Online debate

Structured debates may increase motivation, enhance critical thinking, and trigger affective communication skills in learners (Alen et al., 2015 ; Howell & Brembeck, 1952 ; Jagger, 2013 ; Liberman et al., 2000 ; Zare & Othman, 2015 ). Participating in debates can enhance learners’ confidence, and promote substantive knowledge and practice skills (Alen et al., 2015 ; Blackmer et al., 2014 ; Doody & Condon, 2012 ; Keller et al., 2001 ). With time flexibility, online debates also allow extended reflections and autonomy (Mutiaraningrum & Cahyono, 2015 ; Park et al., 2011 ; Weeks, 2013 ). Despite the rich literature on F2F debates, few research is available on online debates for learning (Mitchel, 2019 ). Thus, exploring how to leverage debate in online environment is imperative.

2.4 Feedback in BL

Through learner-learner interactions, learners support each other on academic and non-academic issues (Lee et al., 2011 ). Research indicates that peer interactions and support correlate positively with learning outcomes (Ashwin, 2003 ; Chu & Chu, 2010 ; Lee et al., 2011 ). Peer feedback, a type of learner-learner interaction, invites learners to review their peers’ drafts or work in progress and provides feedback for improvement (Topping et al., 2000 ). It further encourages learners to make revisions or modifications according to peer feedback (Li et al., 2010 ; Zhang & Toker, 2011 ). Formative peer-feedback encourages learners to focus on learning rather than grades (Fluckiger et al., 2010 ). Thus, it enhances the quality of students’ work (Aghaee & Keller, 2016 ) and helps to build a learning community together (Rovai, 2002 ). It is also effective in enhancing knowledge acquisition as found in computer science courses (Venables & Summit, 2003 ). Reportedly, learners value the experience of reviewing others’ work and learning from fellow students (Li et al., 2010 ). Immediate feedback is critical in motivating learners (Denton et al., 2008 ) and increasing learners’ satisfaction (Lee et al., 2011 ). Otherwise, when feedback is delayed or not available, learners may lose motivation (Higgins et al., 2002 ) and miss opportunities to seek alternative strategies for solutions (Earley et al., 1990 ; Stein & Wanstreet, 2008 ). Therefore, it is vital to explore feedback strategies from both instructor and peers in BL.

The purpose of this study is to investigate effective, as well as ineffective instructional strategies and technology usage in a blended course. The following three research questions guided this study:

In BL, what instructional strategies are more effective or ineffective, and why?

From graduate students’ perspective, what are the advantages and disadvantages of BL?

How can BL leverage learning technologies?

3 Research design

A case study can provide an in-depth and detailed examination of the situation and its contextual conditions (Thomas, 2011 ; Yin, 1994 ). Thus, a mixed-method single case study was designed to explore learners’ experiences in BL within the authentic context.

3.1 Context and participants

The study was conducted in a graduate-level blended course at a public university in the Midwest of the USA in the Fall semester of 2019. This course introduced the foundations of instructional technology. Participants were volunteers recruited from the class, including both male (n = 2) and female (n = 4). Five participants were advanced Ph.D. students, and one was in a certificate program, and they were all majoring in learning design and technology. Participants were non-traditional students with a full-/part- time job while enrolled in the course. All participants had professional experiences as teachers, trainers, or instructional designers. Five of the six participants were native English speakers.

The learning activities in this BL course included paper analyses, online reading reflection journals or discussions, online debates, annotated bibliographies, presentations, and a final exam. The blended course included seven bi-weekly F2F sessions and eight weeks of online sessions. All F2F class meetings were arranged in the evening to accommodate students’ working schedules. In four out of eight online sessions, students were required to read weekly articles related to the topics and to post reading reflection journals in Canvas, a course learning management system (LMS). They were also encouraged to comment on peers’ reading reflection journals.

In addition, between Week 2 and 6, students participated in two rounds of online debates via Nuclino, a free online team collaborative tool with graduate students in a similar course at another university. Five groups of four were formed from the two classes, with two students from each university per group. Students conducted online debates within each group. The two students with the Authors’ role summarized the chapter from the authors’ perspective as well as presented their personal thoughts. Then, the two students from the other university followed the same procedure from the Responders’ perspective. Last, the two students with the Author’s role rejoined the conversation. Only discourses of the consenting participants were analyzed for this study. On Zoom, students also had the opportunity to meet with five guest speakers, who were either the authors of the textbooks or the authors of the readings assigned in the course. In general, each talk lasted 40–50 min, including 10–15 min for questions and answers.

To provide detailed feedback on students’ online discussions and assignments, the instructor used One Drive, an online collaboration tool adopted by the university. In One Drive, the instructor created a folder for each student and uploaded the feedback on the assignments into each folder. In F2F sessions, the instructor summarized students’ achievements and progress from the previous week and then presented new content. To create a personalized learning environment, the instructor used individual student’s names and provided examples that are highly related to students’ education and job backgrounds. After that, students presented their paper analysis, and the rest of the class provided feedback according to the same rubric. To ensure openness and effectiveness of peer feedback, the instructor highlighted that the peer evaluation scores would not be counted toward the final grade and constructive peer feedback was more important than just polite compliments.

3.2 Data sources

Data sources in this study included: (1) semi-structured interviews with six students, (2) mid-term and final course evaluations from seven students, (3) two rounds of online debates, (4) four weeks of online reading reflection journals, and (5) the instructor’s reflections. Six semi-structured interviews were conducted at the end of the semester via Zoom. The interview protocol included eight questions, such as background information of interviewees, the activities that students thought effective or ineffective, the role of technologies, and suggestions on technology use in BL. Each interview lasted approximately 30 min and was audio-recorded (Table 1 ).

The two rounds of online debates of five groups generated 30 discussion posts in total. Each group generated six discussion posts with three posts per round. The first-round of online debate generated 9,397 words, and the second round generated 7,283 words in total.

The online reading reflection journals and comments were posted on Canvas. In each week, students addressed three questions: (1) What are the important ideas in the readings? (2) Why are they important to you? And (3) what are the implications for your research or practice? Students were asked to post their original post, a reading reflection journal, to earn points. They were also encouraged to comment on peers’ posts, while such comments were not graded.

All students anonymously completed a mid-term course evaluation and a final course evaluation during F2F sessions without the instructor’s presence. Qualitative data were collected from the course evaluations and analyzed for this study.

3.3 Data analyses

All qualitative data were analyzed by two researchers to ensure trustworthiness. The researchers used thematical analysis (Braun et al., 2014 ) to analyze the interviews, online debate and discussion, and the qualitative data from the course evaluations. The interviews were transcribed by the researchers, and first-level member checking was conducted with the interviewees. Once the researchers transcribed the data verbatim (Paulus et al., 2013 ) and confirmed the transcripts, thematic analysis was conducted. One of the researchers read the interview transcripts and suggested initial codes, categories, and themes, and two of the researchers then discussed them, resolved any disagreements, and finalized coding. The same protocol was followed to analyze online debate discourse and reflection journals.

4.1 Research question 1 (RQ1)

4.1.1 effective strategies.

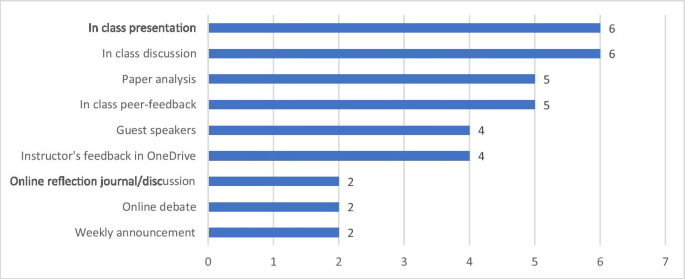

Students had positive perceptions of the effectiveness of learning in the blended course. In the mid-term evaluation, regarding item “overall, this course has provided an effective learning experience,” students rated 4.3/5. The specific activities favored by students were in-class presentations, discussions, peer-feedback, and paper analyses. Figure 1 shows the activities valued by students from the mid-term evaluation. Regarding the reasons why they thought F2F discussions and presentations effective, they expressed that these activities helped construct knowledge and build a learning community. For instance, in the interview, Lana said, “I would say that the presentations were really helpful for me both planning a presentation and watching my colleagues’ presentations.” Shawn shared a similar opinion in the interview “I would say that to be quite honest, the most effective thing that we did was just talking in class… I really enjoyed the conversation. I felt like because we were a smaller group… But I really acquired knowledge and really tried to listen to what people had to say.” In addition, in the course evaluation, one student mentioned: “I enjoy an interactive class atmosphere that allows us to test ideas and explain our understanding from our different perspectives.” The final course evaluation also supported that students had a positive attitude towards group interaction (M = 4.9). As the instructor of the course, the first author also noticed that students actively participated in the classroom discussion and shared their teaching or instructional design experiences and opinions with each other.

Learning activities that students perceived as effective

Students also perceived peer feedback in F2F sessions as effective. In the course evaluation, a student commented: “I enjoy hearing from my colleagues in the class. I feel like everyone in the class practices this in their daily lives, therefore, I value their feedback. I get more out of the discussion than anything else.” In addition, instructor feedback was also valued by students. Students expressed that “your feedback has been thoughtful and helpful.” The value of instructor feedback was supported by the end-of-course evaluation items: “The instructor provided feedback on my performance within the time frame noted in the syllabus.” (M = 4.9) and “The instructor's feedback on my work was helpful” (M = 4.6).

As to the paper analysis activity, students appreciated it as an opportunity to apply academic skills and to develop deeper understandings. For the paper analysis assignments, students read assigned research papers each week and critically analyzed the advantages and disadvantages of the papers regarding the research purpose, research design, data collection, data analysis, findings, conclusions, and implications. As a student noted in the course evaluation, “the thoughtfulness of the paper analysis is helpful to understanding topics at a deeper level.” Shawn also highlighted it in the interview:

I got the most benefit out of the paper analysis. Man, I did not like doing those. But I will say for the first time ever in all of my classes I actually felt like I was doing academic work, where I actually kind of felt like a researcher. I thought I actually used some skills that I never really used before .

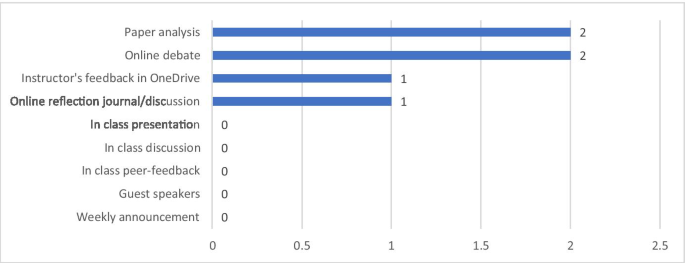

4.1.2 Ineffective strategies

Some students identified the online debates, online discussions, and paper analyses as ineffective strategies (see Fig. 2 ). Students thought that the online debate was ineffective mostly because the rules of the activity limited them in expressing their own thoughts and ideas. In the interview, Lana voiced, “I felt like the online debates with the other school could have been really cool. But they just fell flat because we weren't really debating. We were repeating what had been given to us and basically just summarizing.” Moreover, Cindy said: “I would have preferred a more, you know, an in-person debate, I thought the debate maybe was a misnomer because it wasn't a back-and-forth where we were trying to arrive at a consensus.” In the course evaluation, a student commented, “it was more like a reflection on an article than a debate. It was a great experience collaborating with students from a different university.”

Learning activities that students perceived as ineffective

The analysis of students’ posts in the online debate supported the above claims. Students’ debate was very organized within the group. Students in each group posted six posts in total. However, this organization limited the flexibility of expressing students’ personal thoughts. The instructor reflected on the online debate assignment and noticed that the online debate activities were not well-designed. The online debate should be generated from students’ personal perspectives after the reading, rather than a simple summary of the assigned reading materials. In addition, coordinating among students from two institutions in the asynchronous debate was challenging. If the students from the other university could not finish their part on time, they disrupted the work of the students who were debating with them.

Students’ perceptions of the ineffective online reflection journals/discussions were manifested in their weekly discussions and interviews. Student’s participation in the online reflective journals/discussions decreased as time went by (see Table 2 ). In the first week of the reflective journals/discussions, besides posting their original journals in the discussion forum, students commented on each other’s posts and interacted with peers. However, students were not required to comment on each other’s posts. As the course proceeded, the number of posts and words of posts decreased through four weeks, as indicated in Table 2 . In the interview, Sam explained why he thought it was ineffective:

I didn't feel like I got a lot out of online discussions. I felt that they were better than nothing in terms of learning the material. But they didn't give me the structure that I needed to reflect thoroughly on the reading that we had done .

The paper analysis was considered the most difficult assignment in this course. Two students disliked it and complained that it was difficult and time-consuming. As a student mentioned in the course evaluation, “I actually value the activity; it just takes way too long! I've taken many courses in my life, and this activity has taken the most toll on my emotions.” The instructor noted that this course was the first research-focused course for the graduate students, and thus it would have been better to introduce such a demanding activity with more scaffolding efforts.

Students didn’t like the use of OneDrive for feedback due to the additional cognitive load the technology imposed. They would prefer to minimizing the number of technologies required to succeed in a single course. One student mentioned that “This adds a layer of complexity that is not necessary. It is possible to provide the feedback you give within Canvas.”

4.2 RQ2 From graduate students’ perspective, what are the advantages and disadvantages of BL?

4.2.1 advantages of blended learning.

Participants identified a few advantages of BL, such as learning community, interactions, and immediate feedback. Students valued the learning community they were building tighter in this blended course. Zoe stated that “blended classes create a sense of belonging and give an opportunity to bounce ideas off one another.” Similarly, Lana elaborated that:

Online courses make me feel disconnected from my classmates, whereas with a blended learning situation, you meet occasionally. You get to see people… I felt like in the blended learning environment, I had a chance to get to know my classmates and their strengths. (interviewee transcript A, p2, line 91-94)

In addition, interactions and immediate feedback were other advantages valued by students. In the interview, Sam said, “I think that timeliness of lessons is an advantage in a blended solution, especially if you're going to use synchronous webinars as a part of that blended solution.” Shawn expressed similar thoughts below:

Well, the advantages are the human interaction. The fact that you know when you have an idea or a thought, and you can bounce it off somebody, and they give you feedback within five seconds. It means so much more than if you type up some big paper, you submit it, and then you hear back four or five days later (interviewee transcript B, p3, line166-174)

4.2.2 Disadvantages of blended learning

Participants consistently pointed out a few disadvantages of BL, including both making efforts to attend face-to-face sessions and the various challenges in online learning. Lana expressed the challenges of physically showing up on campus below:

I'd say I'm really fortunate that I have the GRA position as my primary gig. But that's not the norm for most people. For me showing up on campus isn't a big deal. I know for other students, it can be hard to attend classes. (interviewee transcript A, p3, line138-143)

On the contrary, other disadvantages were related to individual learning in online sessions. Sam said: “learners are not physically together [in online sessions]. And by that, I mean adult learners oftentimes learn best from others.” Shawn expressed the motivation perspective of learning on their own “if you're not very motivated intrinsically to just do some of the work on your own, that can be difficult.”

4.3 RQ3 How can BL leverage learning technologies?

The variety of data generated a plethora of suggestions, but of which focused on simplicity and minimalism and offering support. The instructor of the course adopted Canvas, OneDrive, email, and Nuclino for content delivery and communications. Participants stressed that using the least amount of technologies possible is a key to a successful learning experience. Having more than one learning management system only adds complications instead of support. In the interview, Shawn said, “It is important to keep just one mode of communication, for example, Canvas, where all the instructions are provided.” To support students’ learning with technology, instructions are necessary on how to use the technologies deployed in the course at the beginning of the semester. As Zoe said, “You can't have the assumption that everyone knows how to use the technology. There needs to be a little bit more of instruction or simplification [of technology].” Similarly, Cindy stated, “I think it's best if the instructor gives some kind of instructions at the beginning of the semester like how to navigate those technologies and how to use them. I think that would be helpful.” In addition, students suggested that technology use should depend on what is available to students. Linda said:

A lot of our students are rural. They don't have high-speed Internet. They can't do Zoom or WebEx because they just don't have a good width. Yeah, a lot of them still don't have computers at home… It's like you may not be able to use technology. It's gonna really depend on the resources your students have . (interviewee transcript C, p5, line275-283)

5 Discussion

A few instructional strategies were found effective in this study, including class discussions, presentations, peer-feedback, and paper analyses. Some of the asynchronous learning activities were less effective, such as online debates and discussions. Students appreciated BL as it fostered community building, increased interactions and interactivities, and empowered them with immediate feedback. However, F2F and online sessions may be challenging in various ways. For example, it was sometimes uneasy to commute to campus for F2F sessions, while students also needed more guidance on how to succeed in online learning. Students would also like to have simplified and streamlined technology applications in BL, and perhaps more importantly, with sufficient training and timely technical support.

5.1 Effective strategies in BL

Interactions are critical in both F2F and online sessions in blended courses. This study found that F2F interactions in class, such as discussions and presentations, were effective in BL. Students reported that discussions in class helped them construct knowledge through active communications and dialogues from diverse perspectives, which was consistent with previous research (i.e., Hamann et al., 2012 ; Huerta, 2007 ; Vonderwell, 2003 ). In addition, interactions with peers also strengthened the sense of belonging and community, as supported by previous research as well (e.g., Bernard et al., 2009 ; Diep et al., 2017 ; Lidstone & Shield, 2010 ). Despite the various potential benefits of online discussions (Putman et al., 2012 ; Williams & Lahman, 2011 ), students considered asynchronous online discussions ineffective in BL. Specifically, the online debate was not successful in this study, partially due to flaws in the design of the activity. Therefore, appropriate design and facilitations of such interactive learning activities are critical in BL (Butz et al., 2014 ; Szeto & Cheng, 2016 ).

Immediate feedback was praised as effective in this study, confirming similar findings from prior studies (Aghaee & Keller, 2016 ; Fluckiger et al., 2010 ). As students provided formative feedback to peers in F2F classes, they were overall satisfied with instant feedback and the enriched learning experiences. Prior resources also acknowledged that immediate feedback could motivate learners (Denton et al., 2008 ) and increase learners’ satisfaction (Lee et al., 2011 ).

5.2 Technology use in BL

Technology use is critical in BL. Participants in this study were not comfortable with the different technologies utilized in BL, even though they were all advanced graduate students in a learning design and technology program. They suggested simplifying and streamlining the use of technology and would request more technical support in BL. Learning technology can support BL in both F2F and online environments (Norberg et al., 2011 ). However, technology applications in BL should carefully address issues like learner’s preferences, access to technology, and students’ technical competencies. Despite the wide range of available learning technologies, BL should carefully limit students’ cognitive load by simplifying and supporting technology usage (Holley & Oliver, 2010 ; Johnson, 2017 ; Song et al., 2004 ).

5.3 Implications for instructors and students in BL

Instructors should use strategies to increase the interaction among learners and build a learning community in blended courses. In the face-to-face class session, instructors could build a learning community by encouraging students to present their class projects, provide feedback to peers and discuss open-ended issues related to the course topics. In addition, instructors could leverage asynchronous discussions for students’ knowledge construction. However, instructors should provide scaffold and guidance to engage learners in asynchronous discussions.

Regarding technology use in BL, given that technical support can improve students’ satisfaction with the course (Lee et al., 2011 ), instructors should provide appropriate technical support. For example, instructors could create tutorial videos and instructions on using the technology in blended courses. Moreover, instructors should consider students’ learning experience regarding the technology in BL by constantly getting feedback from students.

Students in BL should familiarize themselves with the course learning objectives and the purposes and descriptions of each learning activity. Understanding the rationales behind the course design can help them navigate through the course. In addition, students could consider themselves as active knowledge constructors rather than passive information receivers. Being active learners and taking responsibility for their own learning can help them leverage the resources provided in both face-to-face and online sessions in BL.

6 Limitations and suggestions for future research

A few limitations are noteworthy in this study. First, the study context was limited to a small-sized graduate class in learning design and technology, and thus the findings may not be applicable in other disciplines or at other educational levels. Future research could expand the study in diverse educational settings. Second, the number of interviewees was limited. Thus, instructors and instructional designers should be cautious when applying the findings of this study to larger classes. Third, the interviewer and interviewees were peers with a strong rapport, which must have influenced the research in various ways. To establish trustworthiness, the researchers worked collaboratively to address possible biases and conducted interviews two months after the course had concluded. Fourth, even though the research involved multiple data sources, it did not examine students’ learning outcomes. Future studies could investigate more closely the effect of strategies and technologies on students learning outcomes in BL.

Due to the pandemic, BL will most likely continue and increase in varied forms. This study is therefore particularly meaningful for instructors and instructional designers. Instructors and instructional designers should encourage interactions among learners, provide immediate feedback, leverage peer feedback, and simplify technology usage, and facilitate technology use in blended courses.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to their personal and private nature but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Aghaee, N., & Keller, C. (2016). ICT-supported peer interaction among learners in Bachelor’s and Master’s thesis courses. Computers & Education, 94 , 276–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.11.006

Article Google Scholar

Alen, E., Dominguez, T., & Carlos, P. D. (2015). University students’ perceptions of the use of academic debates as a teaching methodology. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 16 , 15–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2014.11.001

Anderson, T. (2008). Towards a theory of online learning. In T. Anderson (Ed.), Theory and practice of online learning. (pp. 45–74). Athabasca University: AU Press.

Google Scholar

Angeli, C., Valanides, N., & Bonk, C. (2003). Communication in a web-based conferencing system: The quality of computer mediated interactions. British Journal of Educational Technology, 34 (1), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8535.d01-4

Ashwin, P. (2003). Peer support: Relations between the context, process and outcomes for the students who are supported. Instructional Science, 31 (3), 159–173. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023227532029

Barker, P. (1994). Designing interactive learning. Design and production of multimedia and simulation-based learning material (pp. 1–30). Springer.

Bernard, R. M., Abrami, P. C., Borokhovski, E., Wade, C. A., Tamim, R. M., Surkes, M. A., et al. (2009). A meta-analysis of three types of interaction treatments in distance education. Review of Educational Research, 79 (3), 1243–1289. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654309333844

Blackmer, A. B., Diez, H. L., & Klein, K. C. (2014). Design, implementation and assessment of clinical debate as an active learning tool in two elective pharmacy courses: Immunizations and Pediatrics. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Leaning, 6 , 254–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cptl.2013.11.005

Bonk, C., & Graham, C. (2006). Handbook of blended learning environments . Pfeiffer.

Bower, M., Dalgarno, B., Kennedy, G. E., Lee, M. J., & Kenney, J. (2015). Design and implementation factors in blended synchronous learning environments: Outcomes from a cross-case analysis. Computers & Education, 86 , 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.03.0060360-1315

Boyle, T., Bradley, C., Chalk, P., Jones, R., & Pickard, P. (2003). Using blended learning to improve student success rates in learning to program. Journal of Educational Media, 28 (2), 165–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/1358165032000153160

Braun, V., Clarke, V., & Rance, N. (2014). How to use thematic analysis with interview data. In A. Vossler & N. Moller (Eds.), The counselling & psychotherapy research handbook (pp. 183–197). Sage.

Bridges, S., Green, J., Botelho, M. G., & Tsang, P. C. S. (2015). Blended learning and PBL: An interactional ethnographic approach to understanding knowledge construction in-situ. In A. Walker, H. Leary, C. Hmelo-Silver, & P. Ertmer (Eds.), Essential readings in problem-based learning , (pp. 107-131). Purdue University Press.

Butz, N. T., Stupnisky, R. H., Peterson, E. S., & Majerus, M. M. (2014). Motivation in synchronous hybrid graduate business programs: A self-determination approach to contrasting online and on-campus students. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 10 (2).

Chu, R. J., & Chu, A. Z. (2010). Multi-level analysis of peer support, Internet self-efficacy and e-learning outcomes – the contextual effects of collectivism and group potency. Computers & Education, 55 (1), 145–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.12.011

Cocquyt, C., Diep, N. A., Zhu, C., De Greef, M., & Vanwing, T. (2017). Examining social inclusion and social capital among adult learners in blended and online learning environments. European journal for Research on the Education and Learning of Adults, 8 (1), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.3384/rela.2000-7426.rela9011

Darabi, A., & Jin, L. (2013). Improving the quality of online discussion: The effects of strategies designed based on cognitive load theory principles. Distance Education, 34 (1), 21–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2013.770429

Denton, P., Madden, J., Roberts, M., & Rowe, P. (2008). Students’ response to traditional and computer-assisted formative feedback: A comparative case study. British Journal of Educational Technology, 39 (3), 486–500. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2007.00745.x

Deschacht, N., & Goeman, K. (2015). The effect of blended learning on course persistence and performance of adult learners: A difference-in-differences analysis. Computers & Education, 87 , 83–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.03.020

Diep, N. A., Cocquyt, C., Zhu, C., Vanwing, T., & De Greef, M. (2017). Effects of core self-evaluation and online interaction quality on adults’ learning performance and bonding and bridging social capital. The Internet and Higher Education, 34 , 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2017.05.002

Donnelly, R. (2010). Harmonizing technology with interaction in blended problem-based learning. Computers & Education, 54 (2), 350–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.08.012

Doody, O., & Condon, M. (2012). Increasing student involvement and learning through using debate as an assessment. Nurse Education in Practice, 12 , 232–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2012.03.002

Earley, P. C., Northcraft, G. B., Lee, C., & Lituchy, T. R. (1990). Impact of process and outcome feedback on the relation of goal setting to task performance. Academy of Management Journal, 33 (1), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.5465/256353

Ellis, R. & Goodyear, P. (2010). Students’ experiences of e-learning in higher education: The ecology of sustainable innovation . New York: Routledge Falmer.

Fluckiger, J., Vigil, Y. T. Y., Pasco, R., & Danielson, K. (2010). Formative feedback: Involving students as partners in assessment to enhance learning. College Teaching, 58 (4), 136–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2010.484031

Fryer, L. K., & Bovee, H. N. (2018). Staying motivated to e-learn: Person-and variable-centred perspectives on the longitudinal risks and support. Computers & Education, 120 , 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.01.006

Gan, B., Menkhoff, T., & Smith, R. (2015). Enhancing students’ learning process through interactive digital media: New opportunities for collaborative learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 51 , 652–663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.048

Garrison, D. R., & Kanuka, H. (2004). Blended learning: Uncovering its transformative potential in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 7 (2), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2004.02.001

Graham, C. R., Allen, S., & Ure, D. (2005). Benefits and challenges of blended learning environments. In Encyclopedia of Information Science and Technology (1st ed.) (pp. 253-259). IGI Global.

Graham, C. R. (2004). Blended learning systems: Definition, current trends, and future directions. In C. J. Bonk & C. R. Graham (Eds.), Handbook of blended learning: Global perspectives, local designs . Pfeiffer Publishing.

Graham, C. R. (2006). Blended learning systems: Definition, current trends, and future directions. In C. J. Bonk & C. R. Graham (Eds.), Handbook of blended learning: Global perspectives, local designs (pp. 3–21). Pfeiffer.

Graham, C. R. (2013). Emerging practice and research in blended learning. In M. G. Moore (Ed.), Handbook of distance education (3rd ed., pp. 333–350). Routledge.

Guiller, J., Durndell, A., & Ross, A. (2008). Peer interaction and critical thinking: Face-to-face or online discussion? Learning and Instruction, 18 (2), 187–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2007.03.001

Hamann, K., Pollock, P. H., & Wilson, B. M. (2012). Assessing student perceptions of the benefits of discussions in small-group large-class and online learning contexts. College Teaching, 60 (2), 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2011.633407

Henrie, C. R., Bodily, R., Manwaring, K. C., & Graham, C. R. (2015). Exploring intensive longitudinal measures of student engagement in blended learning. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning , 16 (3), 131-155. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v16i3.2015

Higgins, R., Hartley, P., & Skelton, A. (2002). The conscientious consumer: Reconsidering the role of assessment feedback in student learning. Studies in Higher Education, 27 (1), 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070120099368

Holley, D., & Oliver, M. (2010). Student engagement and blended learning: Portraits of risk. Computers & Education, 54 (3), 693–700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.08.035

Howell, W. S., & Brembeck, W. L. (1952). Chapter XIV: Experimental studies in debate, discussion, and general public speaking. Bulletin of the National Association of Secondary-School Principals (1926), 36 (187), 175–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/019263655203618715

Huerta, J. C. (2007). Getting active in the large lecture. Journal of Political Science Education, 3 (3), 237–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/15512160701558224

Jagger, S. (2013). Affective learning and the classroom debate. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 50 (1), 38–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2012.746515

Johnson, C. S. (2017). Collaborative technologies, higher order thinking and self-sufficient learning: A case study of adult learners. Research in Learning Technology, 25 , 1–17. http://repository.alt.ac.uk/id/eprint/2377

Joubert, M., & Wishart, J. (2012). Participatory practices: Lessons learnt from two initiatives using online digital technologies to build knowledge. Computers and Education, 59 (1), 110–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.09.024

Kang, M., & Im, T. (2013). Factors of learner – instructor interaction which predict perceived learning outcomes in online learning environment. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 29 , 292–301. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12005

Keller, T. E., Whittaker, J. K., & Burke, T. K. (2001). Student debates in policy courses: Promoting policy practice skills and knowledge through active learning. Journal of Social Work Education, 37 (2), 343–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2001.10779059

Kim, J. (2020). Teaching and learning after Covid-19. Inside Higher Ed . https://www.insidehighered.com/digital-learning/blogs/learning-innovation/teaching-and-learning-after-covid-19

King, S., & Arnold, K. (2012). Blended learning environments in higher education: A case study of how professors make it happen. Mid-Western Educational Researcher , 25 , 44–59. https://www.mwera.org/MWER/volumes/v25/issue1-2/v25n1-2-King-Arnold-GRADUATE-STUDENT-SECTION.pdf

Kuo, Y.-C., & Belland, B. R. (2016). An exploratory study of adult learners’ perceptions of online learning: Minority students in continuing education. Educational Technology Research & Development, 64 (4), 661–680. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-016-9442-9

Kurucay, M., & Inan, F. A. (2017). Examining the effects of learner-learner interactions on satisfaction and learning in an online undergraduate course. Computers & Education, 115 , 20–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.06.010

Lee, S. J., Srinivasan, S., Trail, T., Lewis, D., & Lopez, S. (2011). Examining the relationship among student perception of support, course satisfaction, and learning outcomes in online learning. Internet and Higher Education, 14 (3), 158–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.04.001