Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 14, Issue 5

- How to manage alcohol-related liver disease: A case-based review

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1530-5328 James B Maurice 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5140-517X Samuel Tribich 2 ,

- Ava Zamani 3 ,

- Jennifer Ryan 4

- 1 Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Southmead Hospital , North Bristol NHS Trust , Bristol , UK

- 2 Department of Hepatology, Royal London Hospital , Barts Health NHS Trust , London , UK

- 3 Hammersmith Hospital , Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust , London , UK

- 4 Department of Hepatology and Liver Transplantation, Royal Free Hospital , Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust , London , UK

- Correspondence to Dr James B Maurice, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Southmead Hospital, North Bristol NHS Trust, Bristol BS10 5NB, UK; james.maurice{at}nbt.nhs.uk

https://doi.org/10.1136/flgastro-2022-102270

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

- alcoholic liver disease

- chronic liver disease

What is already known on this topic

Alcohol-related liver disease (ArLD) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality.

What this study adds

We present a typical case to illustrate current evidence-based investigation and management of a patient with ArLD.

This case-based review aims to concisely support the day-to-day decision making of clinicians looking after patients with ArLD, from risk stratification and fibrosis assessment in the community through to managing decompensated disease, escalation care to critical care and assessment for liver transplantation.

How this study might affect research, practice or policy

We summarise the evolving evidence for the benefit of liver transplantation in alcoholic hepatitis, and ongoing controversies shaping future research in this area.

ArLD is fundamentally a public health problem, and further efforts are required to implement effective policies to reduce consumption and prevent disease.

Introduction

Alcohol is the leading risk factor for premature death in young adults, of which alcohol-related liver disease (ArLD) is a major contributor. 1 The management of ArLD often requires complex decision-making, raising challenges for the clinician and wider multidisciplinary team. This case-based review follows the typical journey of a patient through the progressive stages of the disease process, from early diagnosis and risk stratification in the outpatient clinic through to alcoholic hepatitis and referral for liver transplantation. At each stage, we discuss a practical approach to clinical management and summarise the underlying evidence base.

Case part 1

A 47-year-old man is referred to the general hepatology clinic from his General Practitioner with abnormal liver function tests, ordered in the community following several episodes of non-specific abdominal pain which subsequently resolved. He is now asymptomatic. The referral states that he drinks one bottle of wine each weekday night and more at the weekends. He is on no regular medication, has no other significant medical history and works in construction. On clinical examination, there are a few spider naevi on the chest wall but no other stigmata of liver disease, and his body mass index is 26 kg/m 2 . The blood results show alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 65 IU/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 92 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 100 IU/L, gamma-GT (GGT) 350 IU/L, bilirubin 15 µmol/L, albumin 45 g/L, platelets 256×10 9 /L, internation normalised ratio (INR) 1.0 and creatinine 50 µmol/L. Abdominal ultrasound reveals a mildly enlarged, hyperechoic liver but normal spleen and no ascites.

How can we risk-stratify patients with ArLD in the outpatient clinic?

Early diagnosis and risk stratification of patients enables appropriate selection of patients for follow-up in secondary care, while also providing an opportunity for preventative interventions in those with mild disease. Emergency admissions for hepatic decompensation, where up to 75% of patients present for the first time, represent a late stage of the disease process when 1-year mortality is very high. 2 It is therefore vital to make an early diagnosis of liver disease.

Hepatic fibrosis has been traditionally staged by liver biopsy; however, non-invasive methods of fibrosis staging have an emerging role in ArLD. Transient elastography (TE) has been validated against liver biopsy to accurately stage both advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis, 3–6 and current NICE guidance recommends TE for the diagnosis of cirrhosis in patients with ArLD.

Serological markers of fibrosis such as FIB-4 and AST-Platelet Ratio Index (APRI) have generally not performed well in ArLD, although the enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF) test, measuring direct markers of fibrosis in blood, has an Area Under the Receiver Operator Curve (AUROC) of 0.92 in diagnosing advanced fibrosis using a cut-off value of 10.5. 7

How can we screen for alcohol use disorder and ArLD?

The primary screening tools for alcohol use disorders are the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) or abbreviated AUDIT-C questionnaires. 8 Although clear documentation of the amount of alcohol consumed is important, a diagnosis of alcohol use disorder is more nuanced than volume of alcohol alone, hence the improved sensitivity through use of validated questionnaires. Identifying increasing risk (AUDIT 8–15), higher risk (AUDIT 16–19) or possible dependence (AUDIT≥20) 8 provides an opportunity for targeted brief interventions in those who would most benefit and is a cost-effective method for reducing alcohol intake. 9 Typically only comprising a 5–20 min single interaction, brief interventions offer personalised advice using a motivational and empathetic style of interview ( Box 1 ). If delivered to all new patients registered in primary care, this could save 2500 alcohol-related deaths over 20 years. 10 Patients identified to have alcohol dependence through screening should be referred for specialist treatment.

Typical features of brief interventions

Feedback on the person’s alcohol use and any related harm.

Clarification as to what constitutes low-risk consumption.

Information on the harms associated with risky alcohol use.

Benefits of reducing intake.

Motivational enhancement to support change.

Analysis of high-risk situations for drinking.

Coping strategies and the development of a personal plan to reduce consumption.

Adapted from Public Health England Review: the public health burden of alcohol and the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of alcohol control policies. An evidence review. 45

Although routine blood tests may be helpful in supporting a diagnosis of ArLD (eg, AST>ALT, increased GGT, macrocytosis), they are of limited value in determining the severity of liver disease before established cirrhosis has developed with impaired liver synthetic function (low albumin, high INR and bilirubin). Individuals drinking at harmful levels should be screened for liver fibrosis with TE. Hepatology referral should be considered in patients with TE 8–16 kPa, particularly in those who continue to drink at harmful levels. Patients with TE≥16 kPa are at high risk of developing complications of cirrhosis, therefore should be followed up in a specialist hepatology clinic and be screened for hepatocellular carcinoma and oesophageal varices. Screening endoscopy for varices should be offered when TE≥20 kPa or platelets≤150×10 9 /L. 11 In the primary care setting, fibrosis screening of individuals drinking at harmful levels may alternatively be done with the ELF test, although this is not uniformly available ( figure 1 ). 12

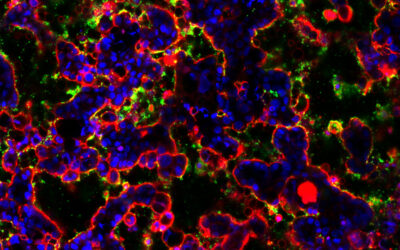

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Screening for cirrhosis in individuals drinking at hazardous and harmful levels. ARFI, Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse; AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test; AUDIT-C, abbreviated Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test; ELF, enhanced liver fibrosis; GGT, Gamma-GT; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; NICE, The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Reproduced with permission from Newsome et al . 46

A high-risk population that should be considered for ArLD screening are the patients admitted to hospital acutely with alcohol-related physical harm, such as acute alcohol withdrawal or alcohol-related trauma. These patients should all be referred to alcohol care teams, and in addition to their expertise in delivering brief interventions, tailored detoxification regimens and vital links to local alcohol support services in the community, some hospitals have trained to perform TE and screen for liver fibrosis. This has provided an opportunity to streamline at risk patients into the hepatology services.

Case part 2

The same patient presents on the acute medical take 1 year later with a 2-week history of jaundice and abdominal swelling. Unfortunately, he has continued drinking alcohol. On examination, he is jaundiced with moderate ascites, tender hepatomegaly and subtle asterixis. He is sarcopenic with arm muscle wasting. He has the following blood results: haemoglobin 100 g/L, mean cell volume 107 fL, white cell count 12×10 9 /L, platelets 135×10 9 /L, INR 2.3, sodium 132 mmol/L, potassium 3.0 mmol/L, creatinine 55 µmol/L, urea 2.0 µmol/L, bilirubin 250 µmol/L, ALT 25 IU/L, AST 60 IU/L, ALP 95 IU/L, GGT 200 IU/L, albumin 35 g/L, c-reative protein (CRP) 45 mg/L. A diagnostic paracentesis reveals an ascitic albumin 16 g/L, white cells 90/mm 3 (80% lymphocytes). An X-ray of the chest is normal. Ultrasound liver demonstrates hepatomegaly 17 cm, splenomegaly 15 cm, moderate ascites and a patent portal vein. A clinical diagnosis of alcoholic hepatitis (AH) is made.

What is the role of liver biopsy in the diagnosis of AH?

AH is a clinical syndrome characterised by jaundice and coagulopathy in the context of recent and prolonged heavy alcohol use. Rapid development of jaundice is accompanied by a systemic inflammatory response with constitutional symptoms and low-grade fever, with or without other features of decompensation.

The diagnosis of AH can be made using a standard consensus definition based on clinical and biochemical parameters ( table 1 ), originally established to allow inclusion in clinical trials without the need for a liver biopsy but now generalised to clinical practice. 13 Neither European Association for the Study of Liver Disease (EASL) nor American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines recommend liver biopsy in patients meeting the criteria for probable AH, 9 10 and these recommendations have been supported by more recent data, showing that liver biopsy rarely changes the diagnosis when clinical criteria are met for AH. 12 However, if diagnostic uncertainty remains, such as atypical biochemical markers, uncertain alcohol use or a suspected alternative cause of liver injury, a liver biopsy should be undertaken to confirm the diagnosis, particularly if planning to administer AH-directed medical therapies. 14

- View inline

Consensus definition for ‘probable’ alcohol hepatitis 13

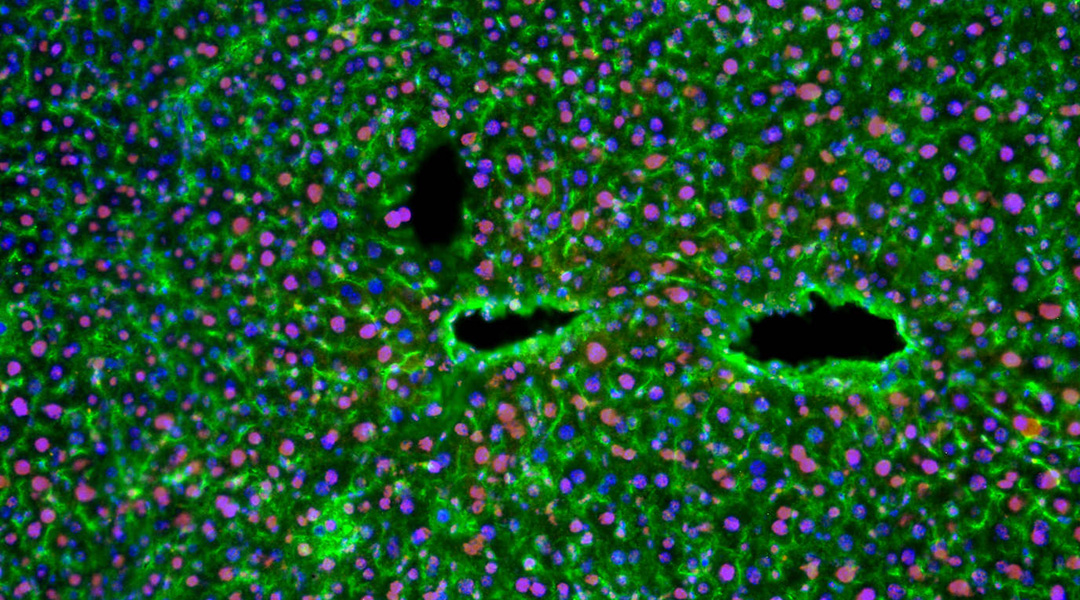

In those patients in whom a biopsy is undertaken, specific histological features such as degree of neutrophil infiltration, fibrosis stage and presence of megamitochondria can be useful for prognostication using the Alcoholic Hepatitis Histologic Score, which is independently predictive of 90-day mortality. 15 However, the utility of this is significantly limited by interobserver variability between reporting pathologists. 16

Should this patient be treated with steroids?

Once a diagnosis of AH is established, patients should be risk stratified using a validated scoring system. The modified Maddrey’s discriminant function (mDF) is a commonly used score, which defines a cut-off of ≥32 as severe AH; however, this is very sensitive and risks over-treating patients with mild disease. 17 The Glasgow Alcoholic Hepatitis Score (GAHS) and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) are better predictors of 28-day and 90-day mortality than mDF 18 19 and are also now included in EASL and ACG guidelines, with severe AH defined as GAHS≥9 or MELD≥21. 20 , 14

The STeroids Or Pentoxifylline for Alcoholic Hepatitis (STOPAH) study is the largest randomised controlled trial to investigate the efficacy of corticosteroids in the treatment of AH. It included 1103 participants with severe AH and the group that received prednisolone only had a small non-significant improvement in 28-day survival (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.01, p=0.06), a benefit which was lost by 90 days and 1 year. In the multivariate analysis adjusting for baseline variables, prednisolone was associated with improved 28-day survival compared with placebo (OR 0.61, p=0.015), although not at 90 days or 1 year. 21 Further meta-analyses of pooled data have replicated these findings. 22

The EASL and ACG guidelines advise to take steroid treatment with prednisolone 40 mg per day in patients with severe AH, as defined by either the mDF, GAHS or MELD Score. Steroid responsiveness should be assessed using the Lille Score, typically on day 7, although there is data to support earlier application on day 4, 23 with steroids stopped in non-responders (Lille Score≥0.45); responders should complete a 28-day course. It may be possible to predict Lille response using a baseline neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), with an NLR of 5–8 predictive of a significant reduction in 90-day mortality with corticosteroid treatment, compared with no reduction when NLR is less than 5 or more than 8. 24 Emerging data is further delineating which patients may derive the greatest benefit from corticosteroids 25 ; however, this remains an area of ongoing research.

Infection is a frequent complication of severe AH, contributing significantly to the high mortality rate and associated in particular with an increased 90-day mortality. 26 Corticosteroids are associated with an increased incidence of infection post-treatment compared with placebo (10% vs 6%), 21 and significantly worse 90-day mortality if patients develop infection within the first week of starting steroids. 26 Therefore, particular caution is required prior to starting prednisolone in patients with active sepsis, bearing in mind that patients with cirrhosis may not mount a classic immune response to infection. 26 Biomarkers to predict risk of incident infection on steroids are an area of research interest; baseline NLR of >8 is also associated with increased infection at day 7 of corticosteroid treatment (OR 2.60, p=0.006), but requires further validation. 24

In clinical practice, the commencement of steroids is delayed until infection is excluded, including negative cultures of blood, urine and ascitic fluid. This period also allows for the assessment of the bilirubin trend which, along with risk stratification scoring, helps to inform the decision to start corticosteroids. 27

What are the considerations in managing alcohol withdrawal in patients with advanced liver disease?

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS) should be assessed using the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for AlcoholScore, with a symptom-based regimen rather than fixed dosing in order to reduce drug accumulation. 28 Benzodiazepines reduce withdrawal symptoms and the risk of both seizures and delirium tremens and are considered the gold standard for treatment of AWS. Long-acting benzodiazepines such as chlordiazepoxide and diazepam should only be used with caution in patients with cirrhosis and impaired synthetic function due to their unpredictable half-life and significant accumulation in the presence of hepatic dysfunction, where the use of shorter-acting lorazepam or oxazepam may be preferable if available. In addition, benzodiazepines can both precipitate and worsen hepatic encephalopathy and so should be used with care.

Abstinence from alcohol remains the only independent predictor of long-term survival in patients presenting with severe AH 29 and early intervention from an alcohol liaison service during the hospital admission is of fundamental importance.

What is the role of nutrition in the management of AH?

Patients with both AH and cirrhosis are characterised by an almost universal state of malnutrition, sarcopenia and B vitamin deficiency, alongside increased resting energy expenditure and impaired metabolism of carbohydrates, lipids and proteins. 30 Early involvement of the dietetic team is vital to ensure patients with AH meet their nutritional requirements.

Increased caloric intake has been associated with a reduced incidence of infection, improved liver function and quicker resolution of hepatic encephalopathy in multiple randomised trials. 30 A recent large trial reported lower rates of infections and improved 1-month and 6-month mortality in patients with severe AH treated with corticosteroids who received a calorie intake of ≥21.5 kcal/kg/day compared with those who received<21.5 kcal/kg/day, regardless of Lille response or of the mode by which the calories were delivered. 31

EASL and European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) guidelines recommend an aim of 35–45 kcal/kg/day and a daily protein intake of 1.2–1.5 g/kg/day, with the oral route as first line and nasogastric feeding advised if oral intake is inadequate. 30 Intravenous thiamine replacement should be given to all patients with a history of alcohol use to reduce the risk of Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Several clinical trials have failed to demonstrate evidence for the use of various specialised dietary formulas and ESPEN recommend using standard nutritional supplements or feed with a high energy density, with a late evening supplement to reduce overnight starvation duration. 30

Case part 3

A full septic screen including blood cultures did not reveal any evidence of sepsis. The patient is managed with nutritional supplements, lactulose 20 mL three times a day and prednisolone 40 mg once daily. At day 7, his blood results are bilirubin 355, INR 3.0, PT 27, Cr 90, albumin 29. Lille Score is 0.60 (>0.45) indicating a poor prognosis, so prednisolone is stopped. Overall 90-day mortality in patients with AH is approximately 30%, increasing to around 45% in patients with a Lille Score>0.45 after 7 days of corticosteroids. 19

Is liver transplantation an option in severe AH?

In Europe, ArLD is the leading indication for liver transplant (LT), but the timing and selection of patients for liver transplantation with ArLD is controversial. A period of abstinence is vital to understand the extent of hepatic recompensation that can occur without the need to undergo LT and to ensure the patient is engaged with the process. However, although pretransplant abstinence is one important predictor of post-LT sobriety, it is not the only factor, and there is data that the risk of relapse is no higher in carefully selected patients transplanted with severe alcoholic hepatitis (SAH) compared with those with alcohol-related cirrhosis under standard selection criteria. 32

Challenging the traditional exclusion of patients with SAH from consideration for LT, a multicentre cohort study in France offered LT to patients with SAH who met specific stringent selection criteria, including non-response to steroid therapy, a first presentation of liver decompensation and a robust social support network. 33 This study showed significantly improved survival in the group offered LT at 2 years (71% vs 23%), a benefit almost entirely gained in the first 6 months. Long-term follow-up data was recently presented, showing overall survival at 1, 5 and 10 years of 83%, 70% and 56%, respectively. Severe alcohol relapse was evident in 10%, similar to other cohorts transplanted for ArLD using standard selection criteria. 34

The largest study in the USA on LT in SAH is a retrospective review of United Network for Organ Sharing data. In 147 patients transplanted with SAH between 2006 and 2017, with no previous decompensation and abstinence of less than 6 months, 1-year and 3-year survival was 94% and 84%, while return to sustained drinking occurred in 10% at 1 year and 17% at 3 years. 35 Interestingly, in a smaller retrospective case-controlled study comparing patients transplanted with SAH with<6 months abstinence (n=46) with a group transplanted for standard ArLD criteria and>6 months abstinence (n=34), the two groups had comparable 1-year survival (97% vs 100%, p=1) and return to harmful drinking after median follow-up of 532 days (17% vs 12%, p=0.5). 32

The only prospective trial of early liver transplantation in SAH was a non-randomised, non-inferiority, controlled trial recently published by the group in France. Over 2 years of follow-up, patients with SAH offered early liver transplant (n=68) had a small but non-significant increased risk of alcohol relapse compared with those transplanted for alcohol-related cirrhosis after ≥6 months of abstinence (n=93, relative risk 1.45, 95% CI 0.82 to 2.60), but also a greater risk of high levels of alcohol intake (RR 4.10, 95% CI 1.56 to 10.75). The 2-year post-transplantation survival was similar between these groups (89.7% and 88.2% respectively, HR 0.87, 95% CI 0.33 to 2.26), whereas the overall 2-year survival of patients with SAH who were not transplanted (n=47) was significantly reduced compared with those who were (28.3% vs 70.6%, HR 0.27, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.47). 36

The landscape of public and medical opinion on offering transplantation for SAH is changing in light of this data. However, concerns remain that predictive models are suboptimal and over 50% of patients with an unfavourable prognosis based on the Lille Score will survive without LT. 37 As such, the UK pilot on LT in SAH failed to recruit any patients over a 3-year period and was closed. 38 The current UK position recommends that if liver insufficiency persists after 3 months of documented alcohol abstinence in individuals with an index presentation of severe AH, consideration should be given to referral for liver transplantation if their psychosocial risk profile is favourable. 37

Case part 4

The patient’s clinical condition deteriorates over the following week. He becomes febrile, an ascitic tap confirms spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (white cells 700 cells/mL, neutrophils>90%) and he develops an oliguric acute kidney injury with haemodynamic instability requiring regular fluid boluses. His liver function remains poor (UK Model for End Stage Liver Disease (UKELD) 68). You call the intensive care unit (ITU) to review the patient, but questions are raised about his suitability for level 3 care.

Should this patient be escalated to critical care?

This patient now requires organ support with inotropes and likely renal replacement therapy. Historically, patients with ArLD have experienced barriers to timely escalation to ITU due to a perceived poor prognosis. Data in the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death report in 2013 confirmed this practice, showing that 31% of patients deemed to require and be appropriate for escalation of care on independent review of the case notes did not receive such treatment. 39

In the same report, a review by the treating clinicians identified only 7% of cases who were appropriate for escalation but did not receive it. Subjective judgements detrimentally influenced these decisions and led the report to conclude that failure to escalate was due to clinicians having a prior view that it was not appropriate to escalate care in patients with ArLD.’ 39

Over the last 20 years, there has been a significant improvement in survival of patients admitted to ITU with organ failure complicating decompensated chronic liver disease, with mortality falling from 41.0% to 32.5% over this period, despite comparable scores for severity of illness at presentation. Although ArLD was associated with worse survival, improvements were also reported in this group over the same period (50.9% mortality to 41.9%, mean (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II Score 20 vs 19), such that the majority admitted to ITU will survive. 40

However, mortality rates for patients with ArLD and acute-on-chronic liver failure admitted to the ITU remain high, and escalation decisions require careful discussion and shared decision-making between the medical and critical care teams, alongside patients and their families as required. One of the first questions posed by the ITU team may be whether they are a transplant candidate. This is not a straightforward question to answer and may not be the most pertinent issue at this point in the patient’s care: in his case, the immediate answer would be ‘no’ in the UK, for reasons discussed above. But if he survives this admission, maintains abstinence but continues to have a qualifying UKELD Score he may be considered for a transplant assessment in 3 months.

In this instance, the patient’s age and the fact this is a first presentation with hepatic decompensation strongly support escalation at this stage, but the CLIF-ACLF prognostic scoring system can be helpful to add objective data to discussions between the managing team and ICU. While not including some increasingly recognised prognostic factors such as the presence of sarcopenia, the European Foundation for the Study of Chronic Liver Failure Acute-on-chronic Liver Failure (CLIF-C ACLF) Score has nevertheless been validated in a large dataset of patients with decompensated chronic liver disease and organ failure. 41 Days 3–7 on the ITU may be the optimal time to calculate this score, when an accurate assessment on the trajectory and likely outcome can be made. 42 Applying it in this way can support decision-making between the patient’s primary team and the ITU and provide timescales and goals with which to assess the benefits of level 3 care when there is disagreement or uncertainty.

However, even in the setting of treatment escalation it is important to remember that his overall prognosis is poor at this stage and, therefore, early involvement of the palliative care (PC) team should be considered. This can be done in parallel with full active medical care; it is important to bear in mind that PC is not synonymous with ‘end-of-life care’ and they are excellently equipped to optimise symptom control and begin to address wider holistic issues in the care of a patient at high risk of death. As such, early involvement of PC has been shown to improve symptom control and quality of life. 43

Case part 5

After 2 weeks in the ITU and a prolonged inpatient stay, the patient makes sufficient recovery to be discharged home. He continues to have moderate ascites managed with spironolactone and significant liver synthetic dysfunction (UKELD 60). He begins to attend his local alcohol support group and his partner has removed all alcohol from the house to support his abstinence.

When should you refer for transplant assessment?

Although he has made significant progress, this patient remains very unwell and at high risk of further deterioration. His ‘window of opportunity’ for transplant assessment is small. There is no fixed rule on this, but recent guidelines suggest that referral should be considered after 3 months of abstinence, or even sooner if the patient is actively engaged in alcohol cessation support, if there are issues that may complicate the workup assessment, or if the risk of death within 3 months is high. 44 In parallel to referral, every effort should be made to optimise his physical fitness, including dietician input and a graded exercise plan.

The patient maintains abstinence, is referred and successfully receives a life-saving liver transplant. A multidisciplinary team approach is required for patients admitted with decompensated ArLD, in which a dedicated alcohol care team is vital, but preventative measures on a population (eg, minimum unit pricing) and individual (eg, brief interventions and fibrosis stratification) level early in the disease course will have the greatest impact.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication.

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

- Griswold MG ,

- Fullman N ,

- Williams R ,

- Aspinall R ,

- Bellis M , et al

- Kettaneh A ,

- Tengher-Barna I , et al

- Pavlov CS ,

- Casazza G ,

- Nikolova D , et al

- Detlefsen S ,

- Sevelsted Møller L , et al

- Lackner C ,

- Bataller R ,

- Burt A , et al

- Madsen BS ,

- Hansen JF , et al

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- Anderson P ,

- Chisholm D ,

- Gillespie D ,

- Ally A , et al

- de Franchis R , Baveno VI Faculty

- Forrest E ,

- Chalasani NP , et al

- Altamirano J ,

- Katoonizadeh A , et al

- Horvath B ,

- Allende D ,

- Xie H , et al

- Forrest EH ,

- Atkinson SR ,

- Richardson P , et al

- Singal AK ,

- Ahn J , et al

- Thursz MR ,

- Richardson P ,

- Allison M , et al

- Chandar AK , et al

- Garcia-Saenz-de-Sicilia M ,

- Altamirano J , et al

- Sinha R , et al

- Baeza N , et al

- Knapp S , et al

- Cabezas J ,

- Mirijello A ,

- D’Angelo C ,

- Ferrulli A , et al

- Labreuche J ,

- Artru F , et al

- Bischoff SC ,

- Dasarathy S , et al

- Deltenre P ,

- Senterre C , et al

- McCaul ME , et al

- Mathurin P ,

- Samuel D , et al

- Dharancy S ,

- Dumortier J , et al

- Platt L , et al

- Moreno C , et al

- Aldersley H ,

- Leithead JA , et al

- Juniper M ,

- Kelly K , et al

- McPhail MJW ,

- Parrott F ,

- Wendon JA , et al

- Pavesi M , et al

- Fernandez J ,

- Garcia E , et al

- Woodland H ,

- Forbes K , et al

- Millson C ,

- Considine A ,

- Cramp ME , et al

- Newsome PN ,

- Davison SM , et al

Twitter @jamesbmaurice

Contributors JBM conceptualised the original article and the case. JBM, ST and AZ drafted the initial version of the manuscript. JBM and ST contributed further editing of various sections. JR provided senior critical review and edited the manuscript. All authors agreed upon the final version.

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Linked Articles

- Highlights from this issue UpFront R Mark Beattie Frontline Gastroenterology 2023; 14 357-358 Published Online First: 07 Aug 2023. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2023-102519

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Cirrhosis Case Study (45 min)

Watch More! Unlock the full videos with a FREE trial

Included In This Lesson

Study tools.

Access More! View the full outline and transcript with a FREE trial

Mr. Garcia is a 43-year-old male who presented to the ED complaining of nausea and vomiting x 3 days. The nurse notes a large, distended abdomen and yellowing of the patient’s skin and eyes. The patient reports a history of alcoholic cirrhosis.

What initial nursing assessments should be performed?

- Full abdominal assessment, including assessing for ascites

- Heart and lung sounds

- Skin assessment – color, turgor, etc.

- Full set of vital signs

- Neurological assessment

What diagnostic testing do you anticipate for Mr. Garcia?

- LFT’s, CBC, BMP

Mr. Garcia’s vitals are stable, BP 100/58, bowel sounds are active but distant, and the nurse notes a positive fluid wave test on his abdomen. The patient denies itching but is constantly scratching at his chest. He is oriented to person only and his brother at the bedside reports he hasn’t been himself today. He keeps trying to get out of bed

Which finding is most concerning and needs to be reported to the provider? Why?

- Confusion, disorientation – this could indicate hepatic encephalopathy, which could lead to seizures and death if left untreated

What further diagnostic and lab tests should be ordered to determine Mr. Garcia’s priority problems?

- Abdominal X-ray and/or Abdominal ultrasound to visualize liver and whether the distended abdomen is related to ascites or other sources

- Ammonia level to determine if hepatic encephalopathy is the source of Mr. Garcia’s altered mental status.

The provider places orders for the following:

Keep SpO 2 > 92%

Keep HOB > 30 degrees

Insert 2 large bore PIV’s

500 mL NS IV bolus STAT

100 mL/hr NS IV continuous infusion

Hydrocodone/Acetaminophen 5-500 mg 1-2 tabs q4h PRN moderate to severe pain

Diphenhydramine 25 mg PO q8h PRN itching

Ondansetron 4 mg IV q6h PRN nausea

Lactulose 20 mg PO q6h

Mr. Garcia’s LFT’s and Ammonia level are elevated. He is extremely confused and agitated and appears somewhat short of breath. The patient’s current vital signs are as follows:

HR 82 RR 22

BP 94/56 SpO 2 93%

Temp 98.9°F

Which order should be implemented first? Why?

- Insert two large-bore IV’s. The patient requires IV fluids and has other IV meds ordered and will likely need labs drawn. This needs to be a priority.

- You could also say elevate the HOB to 30 degrees or higher, if there was indication that he was lying flat

- His SpO2 is >92%, so no intervention is required there.

- Lactulose should be the next priority intervention – to get the ammonia levels down – but it may take a bit for pharmacy to profile it, send it to the unit, etc.

Which order should be questioned? Why?

- Hydrocodone/Acetaminophen – Acetaminophen can be toxic for patients with liver disease. The way this order is written, this patient could receive anywhere from 3 g – 6 g of Acetaminophen in a 24-hour period. The max for a healthy person is 4 g, but for liver patients, it is 2 g max.

- Either the dose and frequency should be lowered significantly, or the medication should be changed altogether

The order is changed to Fentanyl 25 mcg IV q4h PRN moderate to severe pain. The provider notes somewhat shallow breathing and severe ascites and requests for you to set up for paracentesis. At this time, you express your concern that the patient is extremely confused and agitated and trying to get out of bed. You do not feel that he will be still enough for the procedure. The provider agrees and plans to postpone the paracentesis for now, but orders for you to report any signs of respiratory depression or hypoxia.

Why is Mr. Garcia so confused and agitated?

- His ammonia levels are elevated due to his liver failure – this causes hepatic encephalopathy – damage to the brain cells

- This causes altered mental status, agitation, confusion, and can eventually lead to seizures and death if left untreated

What is the rationale for performing a paracentesis for Mr. Garcia?

- The excess fluid in Mr. Garcia’s belly is compressing his thoracic cavity, causing him to feel short of breath and to only take shallow breaths. Draining this fluid will not only relieve some discomfort, but it can also help improve Mr. Garcia’s breathing

After 6 doses of lactulose, Mr. Garcia is much more calm and cooperative. He is oriented times 2-3 most times. The provider performs the paracentesis and is able to remove 1.5 L of fluid. The patient’s shortness of breath is relieved, and his breathing is less shallow. Ultrasound of the liver showed severe scarring on the liver. Mr. Garcia’s condition continues to improve, and the plan is to discharge him home tomorrow.

What discharge teaching should be included for Mr. Garcia, including nutrition?

- Mr. Garcia should not be eating a high protein diet as this can contribute to the increased ammonia levels and development of hepatic encephalopathy.

- Mr. Garcia should avoid drinking alcohol at all times

- Medication instructions for any new or changed medications

- Especially the importance of taking Lactulose regularly as ordered

- Signs to report to the provider of exacerbation or encephalopathy

View the FULL Outline

When you start a FREE trial you gain access to the full outline as well as:

- SIMCLEX (NCLEX Simulator)

- 6,500+ Practice NCLEX Questions

- 2,000+ HD Videos

- 300+ Nursing Cheatsheets

“Would suggest to all nursing students . . . Guaranteed to ease the stress!”

Nursing Case Studies

This nursing case study course is designed to help nursing students build critical thinking. Each case study was written by experienced nurses with first hand knowledge of the “real-world” disease process. To help you increase your nursing clinical judgement (critical thinking), each unfolding nursing case study includes answers laid out by Blooms Taxonomy to help you see that you are progressing to clinical analysis.We encourage you to read the case study and really through the “critical thinking checks” as this is where the real learning occurs. If you get tripped up by a specific question, no worries, just dig into an associated lesson on the topic and reinforce your understanding. In the end, that is what nursing case studies are all about – growing in your clinical judgement.

Nursing Case Studies Introduction

Cardiac nursing case studies.

- 6 Questions

- 7 Questions

- 5 Questions

- 4 Questions

GI/GU Nursing Case Studies

- 2 Questions

- 8 Questions

Obstetrics Nursing Case Studies

Respiratory nursing case studies.

- 10 Questions

Pediatrics Nursing Case Studies

- 3 Questions

- 12 Questions

Neuro Nursing Case Studies

Mental health nursing case studies.

- 9 Questions

Metabolic/Endocrine Nursing Case Studies

Other nursing case studies.

Citation, DOI, disclosures and case data

At the time the case was submitted for publication Bruno Di Muzio had no recorded disclosures.

Presentation

Previous history of heavy alcoholism.

Patient Data

The liver echotexture appears coarse although the liver surface and hepatic vein walls remain smooth in appearance. There is biphasic flow demonstrated within the main portal vein suggestive of portal hypertension. No other features however of portal hypertension with no upper abdominal masses, flow within the ligamentum teres or splenomegaly. No ascites demonstrated. The hepatic veins were patent. No focal liver lesion. No abnormal biliary dilatation.

The gallbladder was collapsed down. Right upper pole renal cyst. No hydronephrosis bilaterally.

1 case question available

Q: Is the portal vein trace on Doppler normal? show answer

A: No, the flow, although predominantly antegrade, is pulsatile and has biphasic-bidirectional pattern.

Case Discussion

These ultrasound images demonstrate coarsened liver echotexture concerning for cirrhosis and signs of portal hypertension.

The portal vein shows a predominantly antegrade, pulsatile, and biphasic-bidirectional flow. Biphasic flows are commonly seen in patients with tricuspid regurgitation, right-heart cardiac failure, and cirrhosis. In this case, the normal appearances of the hepatic veins and the morphological features of cirrhosis make it the most likely cause for the abnormal portal vein flow.

The portal venous normal waveform should undulate smoothly and must always remain above the baseline.

Case courtesy of Dr Kenny Sim .

2 articles feature images from this case

- Pulsatile portal venous flow

22 public playlists include this case

- 3_114 Liver: Cirrhosis and NASH by RAB Three

- 334433 by Y Tan

- Liver Cases by Zin Min Htun

- UQ Med Yr 3 Hospital practice Orientation week by Craig Hacking ◉ ◈

- abdomen by MD IRFAN ALAM

- UQ Radiology video tutorial: Abdo: Cirrhosis, portal HTN and HCC by Craig Hacking ◉ ◈

- Liver - cirrhosis by Sonam Rosberger

- LIVER by sadrarhami

- Liver Malignant Liver tumor by Hamidou Kourouma

- Vascular ultrasound by Allister Howie

- Abdo - Adult Clinical Conditions - Hepatobiliary by Charlie Handley

- Vascular by Eugene Ng

- Abd Óm by Arnljótur Björn Halldórsson

- Certificate: 3_114 Liver: Cirrhosis and NASH by RAB Three

- Chest by Zin Min Htun

- GD: Hepatobiliary by Gurjeet Dulku

- GK - Abdo - Liver by GLK

- GIT-Liver 2 by Mohamed shweel

- SSS26 by Susheel K

- Hepato case by Nguyen Phu Dang

Promoted articles (advertising)

How to use cases.

You can use Radiopaedia cases in a variety of ways to help you learn and teach.

- Add cases to playlists

- Share cases with the diagnosis hidden

- Use images in presentations

- Use them in multiple choice question

Creating your own cases is easy.

- Case creation learning pathway

ADVERTISEMENT: Supporters see fewer/no ads

By Section:

- Artificial Intelligence

- Classifications

- Imaging Technology

- Interventional Radiology

- Radiography

- Central Nervous System

- Gastrointestinal

- Gynaecology

- Haematology

- Head & Neck

- Hepatobiliary

- Interventional

- Musculoskeletal

- Paediatrics

- Not Applicable

Radiopaedia.org

- Feature Sponsor

- Expert advisers

Liver Cirrhosis Case Study

56 year old Caucasian male with end-stage liver cirrhosis in hospice care, came in for stem cell therapy to help prolong his life. Patient had a history of chronic Hepatitis C, hypertension and diabetes, and did not qualify for liver transplant. Patient had declined steadily over the past year, and over the last month, he had an unintentional weight loss of 30 lbs. He had been struggling with fatigue, weakness, and occasional fever and chills, and also reported of shortness of breath, wheezing, and edema of lower extremities. At the time of treatment, patient presented with an distended abdomen (ascites), with very little energy to even speak.

Pin It on Pinterest

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

CASE STUDY OF PATIENT WITH LIVER CIRRHOSIS

Livercirrhosisisadiseaseinwhichnormaltissueofliverreplacedwithscartissue,livercirrhosisisthe12thleadingcauseofdeathsbydiseaseintheworld.Livercirrhosisiscausedbyanyfactorthatcandamagelivertissues,mostlyfattyliverandchronicliverdiseasesarethemajorcauseoflivercirrhosis. WearepresentingherethecaseofanAsianmanwhowasthevictimoflivercirrhosisthatwascomplicatedbyuntreatedhepatitisc.Hewasexperiencinggeneralizedbodyweakness,brownishtintintheurine,andsuddenweightgainof8-kgswithinaperiodofthreeweeks.Bloodpressurecountwas100/60,pulseratefoundtobe76beats/min,temperature98F,andenlargedumbilical.Laboratorytestsincludingcompletebloodcount,liverfunctiontests,andureatestscameouttobesignificantlyabnormal,complicatingthecase.,ultrasoundreportrevealedthathisliverwasenlarged,urinarybladderpartiallyfilled,umbilicalherniagapereported,ascitespresent(retentionoffluidintheabdomen),Cirrhosisandsplenomegalywerereported.Hisliverwasdamagedandliverfunctioningtestswerenotreturningtonormal,hepatologistrecommendedlivertransplantationasthelastresortforhim. Thereistheneedofgoodclinicalevaluationbyaqualifiedtherapistanduseofappropriateinvestigativestudiestosecurepatientfromsuchacriticalhealthhazard. Keywords:chronicliverdisease,livertransplantation,

Related Papers

Journal of Pharmaceutical Research International

Jaya Khandar

Liver is the second largest organ in human body, more than 5,000 separate bodily functions .including helping blood to clot, cleansing the blood of toxins to converting food into nutrients to control hormone levels, fighting infections and illness, regenerating back after injury and metabolizing cholesterol, glucose, iron and controlling their levels. A 56- years old patient was admitted in AVBRH on date 9/12/2020 in ICU with the chief complaint of abdominal distension, breathlessness on exertion, pedal edema, fever since 8 days. After admitted in hospital all investigation was done including blood test, ECG, fluid cytology, peripheral smear, ultrasonography, etc. All investigation conducted and then final diagnosis confirmed as cirrhosis of liver. Patient was not having any history of communicable disease or any hereditary disease but he has history of hypertension and type II Diabetes mellitus for 12 years. Patient was COVID-19 negative and admitted in intensive care unit. Patient...

The Journal of medical research

Amrendra Yadav

The liver is the multi-functional and vital organ of the body. It is found in the upper abdomen region of the vertebrates. Due to long-term damage, liver stops functioning properly which may lead to cirrhosis. This long-term damage occurred when scar tissue replaces the normal tissue of the liver. This disease develops slowly and has no early symptoms, but when it develops and become worse, then it leads to tiredness, itchiness, weakness, yellow skin, swelling in the lower legs, spider-like blood vessels and an easy bruise on the skin with fluid in the abdomen. The severe complications like bleeding dilated veins in esophagus or stomach, hepatic encephalopathy leading to confusion and unconsciousness and liver cancer may occur in the body. This review article is focusing on the effect of liver damage in the

Asian Australasian Neuro and Health Science Journal (AANHS-J)

Hanun Mahyuddin

Liver cirrhosis is a chronic disease characterized by the presence of fibrosis and regeneration of nodules in the liver, the consequence of which is the development of portal hypertension and liver failure. Usually associated with infectious infectious diseases such as viral hepatitis, alcohol consumption, metabolic syndrome, autoimmune processes, storage diseases, toxic substances and drugs. Major complications include gastrointestinal variceal bleeding, ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis infection, hepatorenal syndrome, hepatic encephalopathy, and hepatocellular carcinoma. A 23-year-old woman comes to the ER, dr. Soegiri Lamongan with complaints of vomiting blood. The patient also complained of black bloody stools. Referred patient from Intan Medika Hospital with the initial complaint of vomiting blood more than 5 times (± equivalent to one medium drinking bottle) four days ago. On examination also found anemic conjunctiva and found splenomegaly. On abdominal ultrasound ex...

Fortune Journals , Umair Akram

Cirrhosis results from chronic liver disease, and is characterized by advanced fibrosis, scarring, and formation of regenerative nodules leading to architectural distortion. The main objective of the study is to find the cirrhosis and its complication, other clinical complications except ACLF and critical illness. This descriptive study was conducted at DHQ hospital, Vehari, Pakistan during June 2022 to January 2023. A comprehensive literature search of the published data was performed in regard with the spectrum, diagnosis, and management of cirrhosis and its complications. Data was also collected from OPD of the hospital record. We include all patients suffering from liver cirrhosis and its complication. It is concluded that patients with cirrhosis have progressive disease and suffer from multiple complications like ascites, HE, variceal bleeding, hepatorenal syndrome, cirrhotic cardiomyopathy, pulmonary syndromes, sarcopenia, frailty, and HCC. The prevention, early diagnosis, treatment, and palliation of these complications are essential in comprehensive clinical care plans.

The Egyptian Journal of Hospital Medicine

ibrahim al rajeh

Clinical Chemistry

Corinne Fantz

Clinical Transplantation

Cyrille Feray

Asian J Pharm Clin Res

Dr Bibhu Prasad Behera

Objective: Efforts can be made to normalize the hematological parameters so that the morbidity and mortality in these patients could be effectively reduced. Methods: This observational study was carried out among 69 cirrhosis patients that fulfills the inclusion and exclusion criteria, attended the medicine outpatient department, and admitted in medicine ward Results: In our study, we had 59 male and 10 female patients with an average age of 49.8±13.19 years. About 92.75% of the patients were alcoholic. Abdominal distension (92.75%) and ascites (84.06%) were the most common presenting complaints. Pallor was present in 42 (60.87%) cases. Splenomegaly was present in 35 (50.72%) cirrhotic patients. Renal dysfunction was present in 23 (33.33%) cases. Sixty-six (95.65%) patients had anemia and 47 (68.12%) patients had thrombocytopenia. Conclusions: From this study, we can conclude that, in cirrhosis of liver patients, various hematological changes are very common which need to be identified and corrected early to reduce morbidity and mortality.

Faridpur Medical College Journal

Shahin Ul Islam

Liver cirrhosis is an important cause of death and disability globally. This cross-sectional study was carried out in Faridpur Medical College Hospital from November 2018 to April 2019 to see the patterns of clinical presentations and associated factors among admitted liver cirrhosis patients. A total of 89 patients were included. Data were collected by detailed history from patients or their relatives followed by thorough physical examination as well as diagnostic evaluation; then those were checked, verified for consistency and edited for result. Among total respondents, the majority were male (69.7%) with a male to female ratio of 1:0.44. Age of patients ranged between 22-106 years with mean age of 52.33 year. The patients predominantly presented with ascites (49.4%), gastrointestinal bleeding (27%), peripheral edema (24.7%), and encephalopathy (21.3%). The in-hospital case fatality rate was 11.2% and the patients presented with decreased urinary output, peripheral edema and ence...

RELATED PAPERS

PabrikKulit PangsitDimsum

Global Journal of Pharmacology

Sharavana Bhava

European Journal of Organic Chemistry

Francesca Martina

Journal of the Korean Institute of Illuminating and Electrical Installation Engineers

Economia & Região

Érica de lima

Comunicação & Sociedade

Claudemir Bertuolo

Abdo mohamed

F. Abachi , Banan Aldewachi

Acta Materialia

Nobuhiro Tsuji

Ismael Possamai

Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science

Sheetal Chauhan

Call/WA :0856 0651 6159 | Jual Bunga Sedap Malam Palangkaraya

Agen Bunga Sedap Malam

Applied and Environmental Microbiology

Brent Christner

Water research

Mirjana Stojanovic

Tatiana Engel Gerhardt

San Diego Law Review

Jesus Silva

Indian Journal of Dental Advancements

shwetang goswami

Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery

Zeliha Sert

A.M. Rabasco-Alvarez

Journal of Geography in Higher Education

Kelly Dombroski

Sustainability

Marinko Stojkov

Proceedings of the 5th Universitas Ahmad Dahlan Public Health Conference (UPHEC 2019)

meiske koraag

Corrosion Science

Patrik Schmutz

Future Oncology

Ahmed Shelbaya

See More Documents Like This

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 18 March 2024

- Epidemiology

Routes to diagnosis for hepatocellular carcinoma patients: predictors and associations with treatment and mortality

- Anya Burton ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4416-0538 1 , 2 ,

- Jennifer Wilburn 1 ,

- Robert J. Driver 3 ,

- David Wallace 4 , 5 ,

- Sean McPhail 1 ,

- Tim J. S. Cross ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0625-8726 6 ,

- Ian A. Rowe ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1288-0749 3 &

- Aileen Marshall 7

British Journal of Cancer ( 2024 ) Cite this article

246 Accesses

Metrics details

- Gastrointestinal cancer

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) incidence has increased rapidly, and prognosis remains poor. We aimed to explore predictors of routes to diagnosis (RtD), and outcomes, in HCC cases.

HCC cases diagnosed 2006–2017 were identified from the National Cancer Registration Dataset and linked to Hospital Episode Statistics and the RtD metric. Multivariable logistic regression was used to explore associations between RtD, diagnosis year, 365-day mortality and receipt of potentially curative treatment.

23,555 HCC cases were identified; 36.1% via emergency presentation (EP), 30.2% GP referral (GP), 17.1% outpatient referral, 11.0% two-week wait and 4.6% other/unknown routes. Odds of 365-day mortality was >70% lower via GP or OP routes than EP, and odds of curative treatment 3–4 times higher. Further adjustment for cancer/cirrhosis stage attenuated the associations with curative treatment. People who were older, female, had alcohol-related liver disease, or were more deprived, were at increased risk of an EP. Over time, diagnoses via EP decreased, and via GP increased.

Conclusions

HCC RtD is an important predictor of outcomes. Continuing to reduce EP and increase GP and OP presentations, for example by identifying and regularly monitoring patients at higher risk of HCC, may improve stage at diagnosis and survival.

Similar content being viewed by others

An overview of clinical decision support systems: benefits, risks, and strategies for success

Reed T. Sutton, David Pincock, … Karen I. Kroeker

Deep whole-genome analysis of 494 hepatocellular carcinomas

Lei Chen, Chong Zhang, … Hongyang Wang

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Josep M. Llovet, Robin Kate Kelley, … Richard S. Finn

Introduction

Cancer survival in the UK is improving but remains poor compared to other European [ 1 ] and high income countries [ 2 ]. Improving cancer survival in the UK is a key challenge set out by the Department of Health, the NHS and the Independent Cancer Taskforce [ 3 , 4 , 5 ]. Survival rates vary greatly between cancers [ 1 ]. Primary liver cancer has a particularly poor prognosis compared to many other cancers [ 1 ]. Furthermore, incidence increased over three-fold for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common form of liver cancer, between 1997 and 2017 [ 6 ]. HCC diagnosis is strongly associated with liver cirrhosis such that approximately 80% of patients with HCC also have liver cirrhosis. Early detection at a treatable stage improves cancer prognosis [ 7 ]. As such, 6-monthly liver ultrasounds for cancer detections are recommended for people at high risk of HCC [ 8 ].

The route a person takes to their diagnosis of cancer is strongly predictive of 1-year survival [ 9 ]. The Routes to Diagnosis (RtD) metric uses an algorithm to assess information about interactions with health care prior to a cancer diagnosis to assign each patient to a route [ 9 ]. Emergency presentations (via A&E, or emergency GP referral, transfer, consultant outpatient referral, admission or attendance) [ 9 ], have the poorest survival for the majority of cancers ( https://www.cancerdata.nhs.uk/routestodiagnosis/survival ). Conversely, in general, routine and urgent GP referral have the best prognosis. Overall, one in five cancers are diagnosed as an emergency; for HCC it is one in three. Understanding the differences in RtD presentations over time and predictors of RtDs can help us understand the survival gap and indicate ways to address it. Here we aim to explore, in HCC cases for the first time, (1) predictors of RtD, (2) differences in RtD presentations over time, (3) associations with mortality, and (4) associations with receipt of potentially curative treatment.

Registry data

Patient-level data on England residents diagnosed with HCC (defined as 10th edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) code C22.0 and the second edition ICD Oncology (ICD-O) morphology code M8170) between 1st January 2006 and 31st December 2017 were extracted from the National Cancer Registration Dataset [ 10 ]. The Registration Dataset uses data from a wide range of sources including hospital activity records, multidisciplinary teams meetings, patient administration systems, pathology reports, molecular test reports and death certificates from the Office for National Statistics. It includes all cases of cancer diagnosed and treated in the National Health Service (NHS) in England (which funds 98–99% of all hospital activity [ 11 ]), as well as some treated privately [ 10 ]. A marker of registration quality is the proportion of cancers identified through death certification alone. In the English National Cancer Registration Database this is less than 1%, indicating that the vast majority of data relevant to a cancer diagnosis is being captured and the cancer registry has very high population completeness [ 10 ].

If a patient had two HCC tumours diagnosed during the study period, only the first tumour was included. Only patients aged 20 or over were included, due to rare aetiologies and subtypes of HCC in young people (47 aged <20 years excluded). HCC diagnoses were based on clinical investigations (imaging) in 60% of cases (as recommended for cirrhotic patients by EASL [ 12 ]), pathology in 35% of cases, and death certificate only or unknown in the remaining 5%. Data extracted included diagnosis date, death date, vital status (alive/dead/emigrated), date of last vital status (follow-up to 02/03/2020), age at diagnosis, gender, ethnicity (broad groups) and Charlson comorbidity score (categorical: no known comorbidities, 1, 2, 3 or more) and index of multiple (IMD) deprivation quintile (depending on year of diagnosis, income domains 2007, 2010, 2015, or 2019 as measured for each lower super output area (administrative areas of approximately 400–1200 households) was used, linked via patient postal address code at diagnosis [ 13 ]). Data on these variables was complete except for 3 people in which a Charlson score had not been derived.

Hospital episode statistics

These data were linked to the Hospital Episode Statistics Admitted Patient Care dataset (HES APC) [ 14 ]. HES data were used to identify cirrhosis status and underlying primary liver disease: cirrhosis status was defined as either compensated, decompensated, or none/unknown based on relevant diagnostic and therapeutic codes, as detailed in Driver et al. [ 15 ] and in the supplementary information. Underlying cause of primary liver disease (PLD) was assigned based on diagnostic codes recorded between five years before and one year after diagnosis. Including diagnostic codes up to one year after diagnosis showed improved PLD identification (supplementary information). The following hierarchy was applied based on relative risk of HCC associated with each PLD to give one primary PLD per patient [ 16 ]: hepatitis C (HCV) > hepatitis B (HBV) > primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) > autoimmune hepatitis > haemochromatosis > alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) > non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). NAFLD was assigned when a patient had fatty (change of) liver, not elsewhere classified, or cirrhosis combined with obesity or diabetes, without any other PLD. Those with no relevant diagnostic codes were designated as ‘Other/unknown’.

Two sources were used to derive receipt of potentially curative treatment: HES APC records [ 14 ] and the Registration Dataset treatment data [ 10 ]. Treatments given from 60 days before diagnosis until death or 2 years (730 days) after diagnosis were included. Pre-diagnosis treatment was included as HCC may be diagnosed clinically and treated prior to the official registry date of incidence which may take histological tissue as the gold standard for diagnosis and reassign date of diagnosis once tissue is received [ 17 ]. The most definitive HCC treatment a patient received during this time was captured based on the following hierarchy of potentially curable treatments: liver transplant > liver resection > radiofrequency or microwave ablation > irreversible electroporation > percutaneous ethanol injection.

Route to diagnosis

Each HCC case was assigned a route to diagnosis (RtD). Details of methods used to identify and assign these are given in Elliss-Brookes et al. [ 9 ]. In brief, the algorithm interrogates cancer registration data linked to routine data from immediately prior to diagnosis (including HES, Cancer Wait Times, and NHS Screening programme data), and assigns a main RtD category: emergency presentation (EP), general practice (GP) referral, Two Week Wait (TWW, urgent GP referral with a suspicion of cancer), inpatient elective (IP), other outpatient (OP), death certification only (DCO, no data available other than a death certificate flagged by the registry) and Unknown. The methodology was developed using data for all patients with newly diagnosed malignant cancer registered in the English National Cancer Registration system between 2006 and 2008 (739,667 tumours). Since then, the metric has been derived yearly for all cancer new registrations and forms part of the cancer registration dataset.

Patient and public involvement statement

No patients were involved in forming the research question or selecting the outcome measures, nor were they involved in developing the study design. No patients were asked to advise on interpretation or writing up of results. Results will be shared through patient charities, regionally and nationally, including the British Liver Trust and on the NDRS and British Association for the Study of the Liver websites.

Statistical methods

Descriptive.

The distribution of demographic and clinical factors in cases by RtD were described using means and standard deviation (for normally distributed continuous data), medians and IQRs (skewed continuous data) and absolute numbers and percentages (categorical data).

Associations with RtD and differences over time

Associations of the four main HCC routes to diagnosis (EP, OP, TWW and GP) with demographic and clinical variables (year of diagnosis, age, person stated gender, area-based deprivation quintile, ethnicity, Charlson comorbidity score, cirrhosis stage, PLD) were examined using multivariable logistic regression models. Unknown, DCO and IP were not examined due to smaller numbers. Proportions presenting via each route by year of diagnosis, unadjusted, demographic-adjusted (age, gender, ethnicity and deprivation quintile) and fully-adjusted (demographic variables and Charlson comorbidity score, cirrhosis stage, primary liver disease) were calculated.

Association with curative treatment

Associations of RtD with receipt of potentially curative treatment, unadjusted, and adjusted for multiple factors (age, gender, diagnosis year, deprivation quintile, ethnicity, Charlson comorbidity score, cirrhosis stage, and PLD) were assessed using logistic regression to calculate odds ratios (ORs). Those with DCO as the RtD were excluded from these analyses as none received curative treatment ( n = 92). Sensitivity analyses were conducted excluding those that died within 90 days of diagnosis, adjusted for TNM stage (not included in the main model as stage was only available for 27% of cases), and stratified by cirrhosis status, age (< or ≥65years), and PLD.

Those with vital status uncertainty due to discrepancies with recorded date of death (date of death before date of diagnosis ( n = 9), date of death before date of treatment ( n = 15), patient traced alive after date of death ( n = 11)) and those lost to follow up (i.e. emigrated ( n = 50), or with missing vital status ( n = 5), were excluded. Those with DCO as the RtD were also excluded ( n = 92) as there was no variation in survival in this group (date of death and date of diagnosis were the same). This left 23,373 individuals for mortality analysis. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression (adjusted for age, gender, diagnosis year, deprivation quintile, ethnicity, Charlson comorbidity score, cirrhosis status, and PLD) were used to calculate odds of 90-day and 365-day (one-year) mortality from diagnosis date, by RtD. Sensitivity analyses were conducted adjusting for TNM stage, and additionally for receipt of curative treatment, and stratified by cirrhosis status, age (< or ≥ 65years), and PLD.

Model assumptions were checked and met for all analyses performed. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 17.1 StataCorp. 2017. Stata Statistical Software: Release 17 . College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC.

Overall, in England 23,555 HCCs were diagnosed between 2006 and 2017. 36.1% of these presented via an emergency route, 30.2% via GP referral, 17.1% via Outpatient referral and 11.0% via Two Week Wait, 1.3% Inpatient Elective, 0.4% DCO and 3.9% had no data available (‘Unknown’ route) (Table 1 ).

Patient characteristics and routes to diagnosis

The characteristics of cases varied by RtD (Table 1 ). People presenting via IP and OP were younger at diagnosis on average (66.0 and 66.4 years, respectively), and TWW and EP (71.9 and 70.2 years, respectively) older. After adjustment for other characteristics (Table 2 ), the odds of EP and TWW were higher for patients with older age at diagnosis and the odds of GP referral and OP lower. 78.1% of HCC cases were in men, and the proportion varied by RtD. After adjustment, the odds of an EP compared to any other route were 24% higher in women, and of a GP or TWW presentation 11 and 17% lower, respectively. Area-based deprivation was strongly associated with RtD; over 27% of EPs were in people in the most deprived quintile of the population and only 13.8% in the least deprived. A similar pattern was seen for GP and OP presentations, but not for TWW and IP presentations. After adjustment for other characteristics, odds of an EP presentation were 45% higher for those in the most deprived quintile compared to the least. In contrast, odds of OP presentation were 25% lower. The ethnicities of those diagnosed via EP, GP and OP were broadly similar, but a higher proportion of those diagnosed via TWW were white (87.2%), and for those diagnosed via IP a lower proportion were white (77.5%) and a higher proportion (6.7%) black. Ethnicity data was missing for a large proportion of DCOs (57%). After adjustment, there was no strong associations of ethnicity with EP, but odds of GP referral or TWW were highest for white people, and odds of OP were highest for Asian and other ethnicities.

Underlying PLD could be established from HES records in 13,777 (58.5%) cases. The remaining 41.5% either had one of the forms of PLD on our list but no record of a corresponding HES code for it, had a different PLD, or had no PLD. Overall, ALD (20.7% of cases) was the most common PLD, followed by NAFLD (15.1%) and then HCV (13.2%) and this varied by RtD. The odds of an EP presentation were highest for those with ALD compared to other PLDs, after adjustment for other characteristics. In comparison, the odds of a GP referral was higher for PLDs other than ALD. More people presenting via OP had a known PLD than those presenting via other routes. People with AIH, PBC, haemochromatosis, and viral hepatitis were more likely to have an OP presentation than those with ALD, or NAFLD. The odds of TWW presentation was highest in those with NAFLD and with no/unknown PLD.

41.7% of cases had no co-morbidity codes recorded in HES and 29.7% had a score of three or more. Those presenting via TWW or IP had fewest recorded comorbidities (57.2% and 55.9% had none, respectively) and those presenting via OP the most (52.0% had a score of two or more). After adjustment, those with known comorbidities were less likely to present via TWW (OR 0.32 [95%CI 0.28–0.36] in those with a score of ≥3 comorbidities compared to those with no recorded comorbidities), and more likely to present via OP (OR 2.08 [95%CI 1.90–2.28] for ≥3). The highest proportion of patients with decompensated cirrhosis was seen in those presenting via EP (accounting for 39.1% of all EPs). After adjustment, those with decompensated cirrhosis were over 4 times more likely to present via EP than those with compensated cirrhosis (OR 4.21 [95%CI 3.91–4.54]). TWW presentations were less likely to have any recorded cirrhosis. TNM stage was only available for 27.3% of cases. The stage distribution was more favourable in those presenting via GP or OP and least favourable for those presenting via EP.

Routes to diagnosis over time

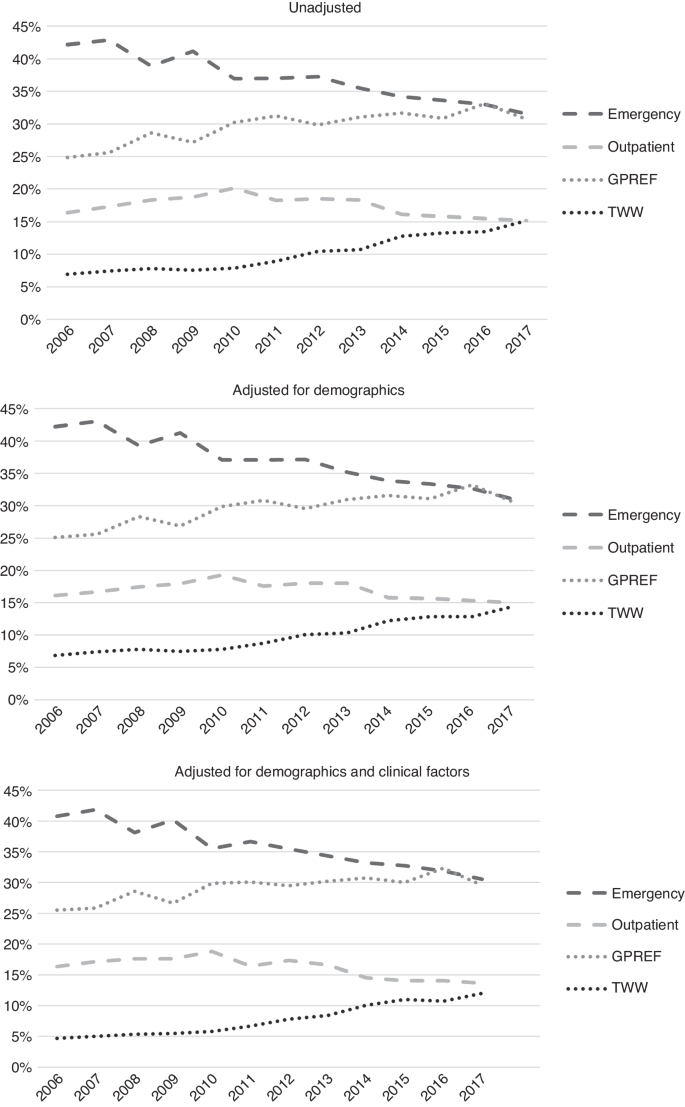

The proportion presenting via EP reduced between 2006 and 2017 from 42.2% to 31.5% of all cases, and the proportion presenting via GP referral and TWW increased (24.9% to 30.7% and 6.9% to 15.2%, respectively). There was no significant change in the proportion presenting via OP (16.4% to 15.2%). These patterns remained after adjustment for demographic and, additionally, for clinical characteristics of patients (Fig. 1 ).

Upper graph: unadjusted. Middle graph: adjusted for demographics. Lower graph: adjusted for demographic and clinical factors.

Associations with mortality

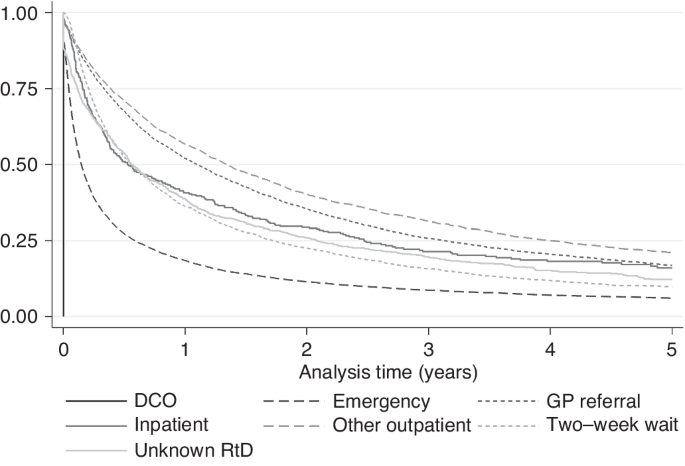

20,671 (87.8%) HCC cases had died by the end of follow-up; median survival was 194 days overall (Table 1 ). Median survival ranged widely from 55 days for diagnoses via EP, to over 400 days for GP and OP (Fig. 2 ). Unadjusted, compared to EPs, those presenting via OP or GP referral had the lowest odds of mortality at 365 days (Table 3 ). In fully adjusted models, associations were only slightly attenuated and those presenting via OP or GP referral continued to have the lowest odds of mortality (OR 0.23 and 0.26, respectively) compared to EP. IP or TWW had intermediate odds (OR 0.37 and 0.42, respectively). In those with stage information, additional adjustment for TNM stage accounted for some of the variation in odds of mortality by RtD and further adjustment for receipt of potentially curative treatment attenuated associations further, but odds of death by 365 days post-diagnosis remained highest for EPs compared to other RtDs.

Kaplan–Meier 5-year survival by route to diagnosis.

In the sensitivity analyses (Table 3 ), for people with decompensated cirrhosis, odds of mortality by 365 days were similar for those diagnosed via TWW and EP, and lowest for GP and OP. Odds of 365-day mortality were highest for EPs irrespective of the underlying cause of PLD, although odds were also high for presentations via TWW for people with haemochromatosis and HCV. For those with AIH, PBC or NAFLD, the lowest odds of 365-day mortality were diagnoses via IP or Unknown RtDs, followed by GP and OP. Analyses were repeated with 90-day mortality as the outcome to assess if associations were different for short term mortality (Supplementary Information 5 ). Associations were broadly similar.

Associations of RtD with curative treatment

20.5% of cases received potentially curative treatment overall, which also varied widely by RtD (Table 1 ); from 9.0% for EP to 35.8% for OP. Unadjusted, compared to EP, the odds of curative treatment were almost six times higher for OP (OR 5.94), four times higher for GP and IP (ORs 3.90 and 3.86, respectively) and two times higher for TWW (OR 1.91), and Unknown RtD (OR 1.92) (Table 4 ). In the fully adjusted model, these associations remained but were slightly attenuated (for example, OR for OP was 4.16 compared to EP). In sensitivity analyses, variations in associations were seen. Excluding those that died in the first 90 days after diagnosis attenuated associations substantially, though odds of curative treatment were still 1.8 to 2.3 times higher for presentations via OP, IP, and GP compared to EP. The same attenuation pattern was also seen following additional adjustment for TNM stage. When stratified by cirrhosis stage, large differences in odds of curative treatment by RtD were seen for those with no known cirrhosis (OR range 6.05 for OP to 1.0 for EP (referent)), and compensated cirrhosis (OR range 4.41 for OP to 1.0 for EP). For those with decompensated cirrhosis, odds were highest in those that presented via OP (OR 3.05) and GP (OR 2.20), but those that presented via TWW, IP or unknown RtD all had similar odds to those presenting via EP. Some differences in range of associations were also seen by PLD. For those with haemochromatosis or HBV, odds of curative treatment in those presenting via OP were over six times that of those presenting via EP. For those with NAFLD, odds of curative treatment were 4–5 times higher in those presenting via IP, OP, or GP referral than via EP. For those with other/unknown/no PLD, odds were much higher for OP (OR 6.01) and GP (OR 4.60), compared to EP. An effect modification by age was also seen; those aged over 65 were over five times more likely to receive curative treatment if presentation was via OP than EP, whereas those under 65 were three times more likely.

Route to diagnosis is strongly associated with odds of 90-day and 365-day mortality and inversely associated with receipt of potentially curative treatment in patients diagnosed with HCC. Patients presenting via EP had the poorest prognosis; <10% received curative treatment and median survival was just 55 days. In comparison, of those presenting via OP, over a third received curative treatment, and median survival was nearly10 times higher than for EP diagnoses. After adjustment for demographic and clinical factors, odds of mortality by 365 days was substantially lower for those presenting via GP or OP routes compared to EP, and odds of curative treatment substantially higher. The differences in rates of potentially curative treatment by RtD were influenced by differences in patient age at diagnosis, PLD, cancer and cirrhosis stage at presentation, and early death. Vulnerable patients including older people, women, those with alcohol-related liver disease, and people residing in more deprived areas, were at increased risk of an EP. Fortunately, the proportion of HCC patients presenting as emergencies is decreasing, and those presenting via GP referrals increasing.

Strengths and limitations

This study used a population-based dataset including the vast majority of HCC cases diagnosed and treated in England. The results are therefore representative of and generalisable to the population. 12 years of data were included which allowed examination of differences over time. The sample size was large ( n = 23,555), despite liver cancer being classified as a rare cancer. RtD is a well-established metric derived from linked routinely-collected population-based datasets. We were able to examine associations of RtD with a wide range of factors known to cause variation in mortality available within and derived from the high-quality National Cancer Registration Dataset. We present a novel method for identification of primary liver cancer from HES codes, validated by comparison with PLD from clinical records.

There are limitations. As data was not collected specifically for the purpose of this study, in common with other observation studies based on routine data, some variables that would have been informative were not available in the dataset. In particular, Barcelona liver cancer stage or variables to derive this (TNM stage, Child-Pugh liver function and ECOG performance status) were not available for the majority of cases. Some important liver cancer risk factors such as BMI, smoking and alcohol consumption, or indicators of liver function, were not available. In our study, underlying cause of primary liver cancer, comorbidity score, and cirrhosis stage were inferred from HES codes, which are dependent on hospital admissions and accurate coding practices. PLD and cirrhosis status were not derivable for around 40% of patients, and it was not possible to know if this was true absence of a PLD or just absence of a code. Furthermore, we used data to identify underlying PLD both before and after the diagnosis of HCC. This was done to improve classification recognising that this is an understudied area, but there is the risk of bias through differential misclassification by RtD. Liver surveillance status was unknown. The deprivation measure used was based on area of residence, therefore there may be residual confounding by socioeconomic status. There were insufficient numbers of inpatient presentations to assess associations with this RtD metric. In addition, we were unable to use cause of death to identify cancer-related death due to the propensity to assign deaths in people with HCC as cancer-related although many would have been due to complications of cirrhosis (77% of deaths were attributed to C220 in our cohort).

Comparison with other literature