Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

A systematic review of intimate partner violence interventions focused on improving social support and/ mental health outcomes of survivors

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation International Centre for Reproductive Health, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Georgia State University Alumna, Atlanta, Georgia, United States of America

Roles Validation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Médecins Sans Frontières-Operational Centre Brussels, Brussels, Belgium

Roles Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

- Emilomo Ogbe,

- Stacy Harmon,

- Rafael Van den Bergh,

- Olivier Degomme

- Published: June 25, 2020

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235177

- Reader Comments

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a key public health issue, with a myriad of physical, sexual and emotional consequences for the survivors of violence. Social support has been found to be an important factor in mitigating and moderating the consequences of IPV and improving health outcomes. This study’s objective was to identify and assess network oriented and support mediated IPV interventions, focused on improving mental health outcomes among IPV survivors.

A systematic scoping review of the literature was done adhering to PRISMA guidelines. The search covered a period of 1980 to 2017 with no language restrictions across the following databases, Medline, Embase, Web of Science, PROQUEST, and Cochrane. Studies were included if they were primary studies of IPV interventions targeted at survivors focused on improving access to social support, mental health outcomes and access to resources for survivors.

337 articles were subjected to full text screening, of which 27 articles met screening criteria. The review included both quantitative and qualitative articles. As the focus of the review was on social support, we identified interventions that were i) focused on individual IPV survivors and improving their access to resources and coping strategies, and ii) interventions focused on both individual IPV survivors as well as their communities and networks. We categorized social support interventions identified by the review as Survivor focused , advocate/case management interventions (15 studies) , survivor focused, advocate/case management interventions with a psychotherapy component (3 studies), community-focused , social support interventions (6 studies) , community-focused , social support interventions with a psychotherapy component (3 studies) . Most of the studies, resulted in improvements in social support and/or mental health outcomes of survivors, with little evidence of their effect on IPV reduction or increase in healthcare utilization.

There is good evidence of the effect of IPV interventions focused on improving access to social support through the use of advocates with strong linkages with community based structures and networks, on better mental health outcomes of survivors, there is a need for more robust/ high quality research to assess in what contexts and for whom, these interventions work better compared to other forms of IPV interventions.

Citation: Ogbe E, Harmon S, Van den Bergh R, Degomme O (2020) A systematic review of intimate partner violence interventions focused on improving social support and/ mental health outcomes of survivors. PLoS ONE 15(6): e0235177. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235177

Editor: Nihaya Daoud, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Faculty of Health Sciences, ISRAEL

Received: March 7, 2019; Accepted: June 9, 2020; Published: June 25, 2020

Copyright: © 2020 Ogbe et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: E.O- University of Gent BOF startkrediet (BOF.STA.2016.0031.01) The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

The global prevalence of intimate partner violence (IPV) has been estimated at about 30% for women aged 15 and over [ 1 ]. We define IPV within this paper as ‘any acts of physical violence, sexual violence, stalking and psychological aggression (including coercive tactics) by a current or former intimate partner’ [ 2 ]. IPV affects men and women, and men or women can be perpetrators or survivors of violence. However, women are the most affected by IPV, and men tend to perpetrate violence more than women [ 3 ]. Survivors of violence are likely to first disclose experiences of intimate partner violence and expect informal support from a friend, family member, neighbour or other members of their social network, prior to seeking support from formal sources like health institutions and legal officers, however, the extent of disclosure differed with age, nature, ethnicity and gender [ 4 ].

IPV has been found to be associated with an increased risk of poor health, depressive symptoms, substance use, chronic disease, chronic mental illness and injury for both men and women [ 5 ]. Social support has been found to be an important factor for mediating, buffering and improving the outcomes of survivors of violence and improving mental health outcomes[ 6 ]. Conversely, social isolation and lack of social support have been found to be linked with poor health outcomes for survivors of violence. Liang et al [ 6 ] discussed the importance, perception of the abuse by the IPV survivor plays on their decision to ask for help and support. They mentioned how cultural factors including stigma and shame around disclosing IPV, perception of the incident as a personal problem and awareness of resources available, play a determining factor on types of resources accessed, especially for IPV survivors with a migrant background or of a low socioeconomic status. IPV survivors who perceive the abuse to be a personal problem were more likely to use placating and avoidant strategies before seeking external support [ 6 ].

In this study, we make use of Shumaker and Brownell’s definition of social support, and define it as any provision of assistance, which may be financial or emotional, that is recognized by both the beneficiary and provider as advantageous to the beneficiary’s welfare. ‘[ 7 ]. IPV interventions that involve the use of social support, have the potential to improve the health seeking behaviour, access to resources and mental health outcomes of IPV survivors. Commonly cited types of social support interventions include but are not limited to the use of peer support, family support and the use of ‘remote interventions like the use of internet or telephones as sources of social support from trained counsellors, as well as information about resources’ [ 8 ]. Goodman and Smyth [ 9 ] discussed the importance of using a ‘network oriented’ approach to provision of domestic violence services that takes into account the value of informal support, from social network members of IPV survivors, as this would promote the well-being of the survivor and sustain some of the benefits of the intervention over time. Given the existing gap in evidence on the effect of different IPV interventions on social support and/ mental health outcomes of IPV survivors, this study aimed to address the evidence gap, by assessing the effects of these different IPV interventions, and network oriented approaches on improving access to social support and improved mental health outcomes for IPV survivors. This is of added benefit, as access to social support improves the mental health outcome of survivors of violence. More evidence of different types of social support interventions targeted at different groups of people, that are effective in addressing mental health outcomes of survivors, are needed.

The systematic review was developed according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses) guidelines. The methods used to screen the studies and define eligibility are described below:

Eligibility criteria

Studies meeting the following criteria were included: Primary research (original articles excluding systematic reviews), targeted at IPV survivors, describing interventions focused on improving access to resources and mental health outcomes for IPV survivors. The interventions had to use a social support or network-oriented approach. There were no restrictions on gender, but most of the studies identified focused on female survivors of violence (See Table 1 ). We defined ‘IPV as physical, sexual and psychological abuse directed against a person, by a current or ex-partner’ [ 10 ].

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235177.t001

Studies had to address the following outcomes: intimate partner violence, social support, mental health outcomes and quality of life. Other outcomes that were also included were those associated with access to resources, utilisation of health services, and safety-promoting behaviours, if they were assessed in addition to the outcomes mentioned earlier. No restrictions were placed on study design or language, to allow for inclusion of all relevant studies.

Information sources

Between May and July 2017, we conducted a search across 5 databases: Medline, Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane and PROQUEST, for studies published between 1980 and 2017. We decided to include studies from the 1980’s because some of the pioneering publications on the use of advocacy and social support, for example, Sullivan et al’s work were published in the late 80’s and early 1990’s and we wanted our review to include some of these publications. Even though the review eventually included only primary studies, we included studies from COCHRANE to allow us to identify additional articles. We did not conduct a separate search for grey literature, as the PROQUEST database also included scholarly journals, newspapers, reports, working papers, and datasets along with e-books. Retrieved references were imported to Endnote and Mendeley and were then transferred to a systematic review software called Co-evidence [ 11 ]. In January 2019, another search was done to update and ensure new articles or information could be included in the review. Table 1 provides an overview and summary of the studies selected, as well as the evidence ranking of the studies.

Search strategy

The search strategy was developed in collaboration with a librarian, as well as a review of other existing systematic reviews on IPV or social support interventions. Search terms combined MeSH terms, and specific terms related to IPV and were adapted to each of the databases searched. This is presented in Table 2 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235177.t002

Study selection

Inclusion of retrieved studies and their eligibility were independently assessed by two reviewers, EO and SH, in a two-step process. First, the authors independently screened all study titles and abstracts using Co-evidence (the systematic review software), which notified each author of conflicts. When a conflict was identified, articles were again independently reviewed, and discordance was resolved through discussion, using the systematic review protocol as a guide. The same process was also used for the full text-screening phase of the study. While this process lengthened the screening process, it allowed for transparency and made it possible for both reviewers to continually reference the study protocol and ensure that the study objectives were adhered to, through the review process.

Data extraction

A standardized data collection form was developed by EO and SH, adapted from the Cochrane data collection grid. EO extracted all the data from the studies, SH and RB reviewed the data and it was agreed that OD would provide input if there was any disagreement about the data extracted.

Risk of bias

The quality and risk of bias in the studies were independently assessed by EO and SH, using the appropriate quality assessment tool. As the studies selected included quantitative and qualitative studies, there was an agreement to assess quantitative and qualitative studies separately. Quantitative studies were assessed using the Quality Assessment Tool for quantitative studies developed by the Effective Public Health Practice Project, see Table 3 for an overview of the components of this tool [ 12 ]. This tool had been used in another systematic review focused on interventions [ 13 ]. Qualitative studies were assessed, using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative Research Checklist [ 14 ], the main components focused on assessing the methodological limitations, coherence, adequacy of data and relevance of research. See Table 4 for an overview.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235177.t003

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235177.t004

Information about studies selected

The initial search across the different databases retrieved 3712 articles, of which 3364 articles were irrelevant based on the screening criteria. 337 articles were assessed at the full text screening stage, and 27 articles selected to be part of the systematic review, the overview is presented in Fig 1

From : Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). P referred R eporting I tems for S ystematic Reviews and M eta- A nalyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed1000097 For more information, visit www.prisma-statement.org .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235177.g001

Results/Key findings from the systematic review

The interventions were classified based on the methodology or type of social support provided to the survivors of violence. Most of the studies identified involved the use of an ‘advocate/ case manager’ or ‘interventionist’ (which referred to a nurse, psychologist or volunteer trained to administer the IPV intervention). The advocate was often responsible for offering the survivor information on resources and helping them identify safety strategies. The interventions usually consisted of weekly sessions or phone calls for a certain period of time. These interventions were mostly in the United States and from other countries like China, Canada, Denmark, Netherlands, Uganda and the United Kingdom. Other interventions involved the use of advocacy with an added psychotherapy component, and interventions that focused on community education, as well as empowerment of the IPV survivors. One of such community focused interventions used an empowerment model and encouraged survivors of violence to take photos of their safety strategies. These photos were used to educate the community about the consequences of intimate partner violence and advocate for community support to prevent intimate partner violence and encourage access to services. In our paper, the term ‘community focused’ included interventions targeted at the community which used participatory and non-participatory methods in the design and implementation of the programmes. The interventions identified in this systematic review had different target groups, pregnant women, survivors of violence resident in shelters, community members and IPV survivors, substance abusing women, and women with small children.

Types of social support interventions for intimate partner violence survivor

Survivor- focused social support interventions..

The interventions described below were all focused on providing social support and improving mental health outcomes for the survivors of violence, all of them involved the use of advocacy/case management approaches, through remote or ‘face to face’ methods. We also identified advocacy interventions with a strong therapeutic component, which we have discussed separately.

Advocacy/ Case management interventions

These interventions involved the use of community-based advocacy interventions focused on individuals that were survivors of violence, these interventions were focused on assisting the survivors identify and access resources, supportive relationships and cope with the effects of intimate partner violence. Fifteen of the studies reviewed (11 RCTs, 2 pre-post evaluation, 1 retrospective study, 1 quasi-experimental study with randomization) described experiences with social support interventions that provided some sort of advocacy service in combination with community support for survivors of violence, on an individual level [ 15 – 29 ].

Advocacy interventions may include ‘helping abused women to access services, guiding them through the process of safety planning, and improving abused women’s physical or psychological health’ [ 30 ]. For the review, interventions grouped under this category included mentor-mother interventions (these interventions involved the training of IPV survivors who were mothers as counsellors and mentors, for other IPV survivors), and use of home-based or in-clinic advocates. Most of the studies reported a decrease in depression, fear, post-traumatic stress disorder, and increased access to social support for the IPV survivors included in the study.

In Tiwari et al’s study, where an advocacy intervention was compared to the usual community services, the reduction in depression and other mental outcomes, was not significant but the reduction in ‘partner aggression’ and increase in access to social support in the intervention arm was significant [ 15 ]. Two of the studies, an in-clinic advocacy intervention by Coker et al [ 23 ] and a home-based advocate intervention by Sharps et al [ 20 ] resulted in a significant reduction in the experience of intimate partner violence by the survivors (decrease in experience of IPV in the intervention arm compared to the control group). The two mentor mothers’ studies included in this review, showed an increase in uptake of support services and mental health services. Prosman et al’s study [ 18 ] specifically showed evidence that the mentor mother intervention led to a decrease of in experience of IPV (decreased Composite Abuse Scale (CAS) mean score by 37.7 (SD 25.7) after 16 weeks), as well as in depression scores. This study had a component that focused on uptake of therapy, which may have influenced the outcomes. Four of these studies compared ‘face to face’ case management/ advocacy services to remote modes of care and assessed the impact on social support and IPV. Gilbert et al’s study [ 24 ] compared online and case manager implemented screening, assessment, and referral to treatment intervention for IPV survivors who were substance abusing, the intervention was guided by social cognitive theory, and focused on short screening, an intervention and referral to treatment (SBIRT) model. There were no significant differences between both groups in terms of impact of the interventions, the study found both groups has an increase in access to social support, IPV self-efficacy (ability to protect themselves from IPV) and abstinence from substance use, irrespective of the type of intervention they received. McFarlane et al [ 26 ] assessed the differences between nurse case management and a referral card on reduction of violence and use of community resources among IPV survivors, and found no differences in outcome between both groups, but found compared to baseline, participants who received either intervention (nurse case management or referral card) had a significant reduction in experiences of violence (threats of abuse, assaults, risks of homicide and work harassment) between baseline and 24 months post-intervention. There were no significant differences in outcome for participants who were in the referral card or case management intervention arm. Other outcomes like improved safety behaviors and a reduction in the utilization of community resources were also found across both groups. Stevens et al’s [ 27 ] study focused on using telephone based support/referral services for IPV survivors compared to enhanced usual care (, the intervention was based on a social support and empowerment model. The study found no significant difference in outcomes between the intervention arm (telephone-based arm) and the control arm (enhanced usual care- community services provided by the community center including health, social, educational, and recreational services). Research participants reported a decrease in experiences of IPV across both groups, associated with ‘higher levels of social support’ at baseline and at 3 months post-intervention. However, the reduced levels of violence did not influence the capacity to obtain or utilize community resources among the research participants. Constantino et al’s [ 29 ] study compared an advocacy based intervention across different methods (online and face to face) and found the intervention reduced depression, anxiety and increased personal and social support among the online group compared to the control group. The intervention included a module that addressed interpersonal relationships, thoughts and emotions as well as access to referral services like legal aid. Another study by Constantino [ 28 ] involved a nurse led intervention focused on providing information on resources and services for IPV survivors living in a domestic violence shelter. The intervention was compared to usual care in the shelter. The intervention group had reduced psychological distress, increased levels of social support and reduced reporting of health care issues. Most of the studies we found in this category showed moderate levels of quality of evidence.

Advocacy/Case management interventions with a psychotherapy component

3 of the studies (3 RCTs) [ 31 – 33 ] were focused on interventions that included specific types of psychotherapy, sometimes delivered remotely or through individual or group sessions. Zlotnick et al [ 31 ] described the use of interpersonal psychotherapy among pregnant women focused at improving social support among the survivors of violence during individual psychotherapy sessions. Though there was a moderate change in depression and PTSD scores (reduction) between the control and intervention groups at post-intake (5–6 weeks), this difference was not sustained at the post-partum period. Hansen et al [ 33 ] describes the use of psychotherapy using either the ‘Trauma Recovery Group’ (TRG) method developed by ‘a private Danish organization called ‘‘The Mothers’ Aid”‘ or regular trauma therapy for individual or groups of women who were survivors of IPV. The study reported significant changes in PTSD, depression and anxiety symptoms and increased levels of social support (high effect sizes); however, our assessment with the EPHPP grading revealed that the study design was weak. Miller et al’s [ 32 ] study shows the effect of a ‘mom empowerment programme’ focused on improving mental health outcomes and ability to access resources among IPV survivors participating in the programme, with resulting improvement in PTSD, depression and anxiety symptoms.

Community-focused/ network social support interventions

These group of studies, distinct from the ones described above focused on community education and change, so the focus of the studies was not just the individual survivor of violence, but the community as a whole. 9 (3 RCTs, 3 pre-post evaluations, 3 qualitative research) of the studies we reviewed consisted of interventions described as being community-based [ 34 – 42 ]. The definitions of community-focused interventions used for classifying the studies followed the typology by McLeroy et al [ 43 ], which refers to interventions where:

- The setting of the intervention is the community

- The target population of the intervention is the community

- The intervention uses community members as a resource

- The community serves as an agent for the intervention (i.e. interventions working with already existing structures within the community)

We have focused on interventions in this category where the focus of the intervention is the community. The interventions described include community participatory research, like those described by Ragavan et al’s systematic review on community participatory research on domestic violence [ 44 ], as well as interventions that are ‘community placed’, where the community is a target of the intervention, and might not have been involved in the design of the intervention, in a participatory way.

All the interventions were focused on IPV reduction and improving social support and mental health outcomes for survivors of violence. Interventions like SASA [ 34 , 39 ], used community members as a resource for the intervention. In the SASA intervention, community activists in the intervention sites were trained on GBV prevention, power inequalities and gender norms. After training, they carried out advocacy activities, engaging different stakeholders and members of their social networks to address harmful social norms around GBV. At the end of the intervention, there were reported lower rates of IPV among the intervention community. Other interventions like the ‘Framing Safety project’ [ 35 ], which focused on promoting agency and self-empowerment among survivors of violence, found that by providing means through which survivors of violence could tell their own stories and take ownership of this process, there was a resulting feeling of empowerment among the women. Other interventions used group therapy sessions that were community-based and culturally tailored to the specific target population. Wuest et al [ 41 ] described a collaborative partnership with different stakeholders (academic, NGOs and community members) to develop a comprehensive intervention to IPV, ‘Intervention for Health Enhancement After Leaving (iHEAL), a primary health care intervention for women recently separated from violent/abusive partners’. The post evaluation revealed significant reduction in depression and PTSD from baseline to 6 months post-intervention, these improvements in mental health outcomes, were present at 12 months post-intervention. Other outcomes, like social support, showed some initial improvement from baseline to 6 months post-intervention but these changes were not sustained till 12 months post-intervention.

Community focused/ network interventions with a psychotherapy component

Three of the nine studies (1 RCT and 2 pre-post study) by Kelly et al [ 36 ], McWhirter et al [ 37 ], and Nicolaidis et al [ 38 ] described group therapy interventions that were designed in collaboration with the target population in a participatory way. These studies reported significant reductions in severity of mental health conditions like depression and PTSD, as well as an increase in social support and self-efficacy for the women who were involved in the study.

The focus of this systematic review was to assess the existing evidence available on IPV interventions focused on improving social support and/or mental health outcomes. To ensure that we included all relevant studies, we included both quantitative and qualitative articles. 27 articles were included in the systematic review out of 337 full text articles assessed. The following interventions were identified via the review: Survivor focused interventions (18 studies: 15 of these studies were focused on advocacy/case management services; 3 of these on advocacy/case management services with a psychotherapy component), community-based social support interventions (9 studies:4 out of these were community coordinated interventions with a psychotherapy component). The heterogeneity of the studies made it difficult to conduct a meta-analysis because of the variability in outcome measures, study design and processes and duration of interventions implemented. Survivor focused advocacy/case management IPV interventions made up most of the interventions identified (18 out of 27). The studies showed good to moderate evidence of the positive impact of these interventions on mental health outcomes and also access to social support for the IPV survivors included in the study, and in a few studies, a reduction in partner aggression or experience of IPV (IPV scores) [ 15 – 23 ]. In one study, by De Prince et al [ 42 ], where a community-based advocacy intervention was compared to an advocacy intervention that was focused on referral, both groups showed improvement in mental health outcomes, but the community-based advocacy intervention group (outreach) had slightly better mental health outcomes. A specific approach of the intervention was that it was community-led/ coordinated, the community based organisation reached out directly to the survivors of violence based on information from the systems based advocate, hence removing the need for survivors to seek out services themselves based on the referrals received from the system based advocate. This study might have important lessons for future advocacy interventions, as just provision of referrals might not ensure uptake of services, and a community coordinated follow up of IPV survivors might be more effective in ensuring uptake. However, it must be noted that only few of the advocate-based studies and 1 of the community-focused interventions reported an impact on IPV, with good level of evidence [ 15 , 20 – 23 , 34 ], similar to what has been found in other reviews of advocate-based interventions on intimate partner violence [ 45 ]. Tiwari et al’s study, which focused on the use of an empowerment, social support and advocacy-focused telephone intervention, found improved mental health outcomes among the intervention group. In comparison, Cripe et al’s [ 46 ] study also compared the effect of an empowerment-based intervention in comparison to usual care among abused pregnant women and found higher scores of improved safety behaviours among the intervention group compared to the control group but ‘no statistically significant difference in health-related quality of life, adoption of safety behaviours, and use of community resources between women in the intervention and control groups’. These differences we attribute to the study design, context and characteristics of the study participant. Goodman et al has described the importance of integrating a ‘social network’ approach into IPV interventions, and linking interventions with social networks of IPV survivors to ensure sustained access to social support for the survivors [ 9 , 47 ]. Many of the advocacy/case management interventions described above have created these linkages by assisting IPV survivors identify sources of support within their existing networks and also engage in forming new social relationships [ 16 , 18 , 48 ]. However, more IPV interventions should integrate this approach in a coordinated systemic manner, as engaging with social network members of the IPV survivors ensures sustainability of the programme’s effects over time [ 9 ].

Several of the studies focused on psychotherapy interventions, which were individual, or group based. We classified these interventions separately as these interventions combined community-based advocacy with a therapeutic component, as opposed to advocacy/case management alone or community focused interventions. These interventions either used interpersonal therapy [ 31 ], traumatic treatment therapy [ 33 ], empowerment based group therapy [ 32 ], and a multicomponent intervention that combined therapeutic education sessions with information on resources and legal help remotely or ‘face to face’ [ 29 ]. All the interventions showed some impact on mental health outcomes and social support, with a weaker level of evidence of an impact on IPV. Although Zlotnick et al’s study[ 31 ] on a therapeutic intervention for pregnant IPV survivors, described an improvement of mental health outcomes (moderate effect on PTSD and depression), this finding was not sustained in the postpartum period, drawing attention to the need to assess the efficacy of interventions in this particular group, taking into account time dependent factors and participant attributes. A review done by Trabold et al [ 49 ], found that clinically focused interventions and group-based cognitive or cognitive behavioural interventions had a significant effect on depression and PTSD, as well as the uses of Interpersonal therapy (time dependent). However, as our review focused on therapies focused on improving social support and mental health outcomes, we included fewer studies. Although we found a similar trend as described by Trabold et al, among community-based interventions (including those that were psychotherapy focused), we could not assign the effect specifically to the type of psychotherapy method, but rather to the length, associated support services and context of the intervention. Sullivan et al [ 50 ] discussed the positive effect of trauma informed practice on mental health outcomes of IPV survivors in Shelters, showing evidence of the importance of IPV interventions to include a comprehensive ‘therapeutic or mental health component’. They also discussed the six components of what ‘trauma informed practice’ which includes: (a) reflecting and understanding of trauma and its many impacts on health and behaviour, (b) addressing both physical and psychological safety concerns, (c) using a culturally informed strengths-based approach, (d) helping to illuminate the nature and impact of trauma on survivors’ everyday experience, and (e) providing opportunities for clients to regain control over their lives’. These components were useful for advocacy/case management interventions for IPV survivors, to ensure a focus on improving mental health outcomes, intersectional collaboration between stakeholders, and that the intervention is survivor-centred and addresses cultural factors.

Interventions that compared remote and ‘face to face’ methods of support and advocacy mostly resulted in a reduction in IPV victimization and increased access to social support. In cases where different modes of intervention delivery were tested, for example a comparison between remotely delivered interventions (telephone or online) and ‘face to face’ interventions, no difference was noted between both modes of intervention. Krasnoff and Moscati’s study [ 51 ] discussed a multi-component referral, support and case management intervention that reported similar reduction in perceived IPV victimization as seen in studies included in our review. There were some differences in the telephone support interventions included, Stevens et al’s study [ 27 ] reported no difference in mental health outcomes compared to Tiwari et al’s study[ 15 ] which found an improvement in mental health outcomes among the intervention group. We postulate differences in outcome could be attributable to the fact that Tiwari’s intervention was more advocacy, empowerment and support focused than the intervention described in Stevens et al study, which was more information and referral focused.

Summary of key findings and recommendations

- Most of the interventions that used advocacy with strong community linkages and a focus on community networks showed significant effects on mental health outcomes and access to social support, we assume a reason for this could be that because these interventions were rooted in the community, there were more sources of support that allowed the survivors of violence to develop better coping strategies, for example in the SASA study that included a strong community engagement component, community responses to cases of IPV were supportive of the survivor, and this had an effect on incidence of IPV. Future research and interventions on IPV should focus on ensuring stronger community linkages and outreach programmes to enhance the impact of the interventions on IPV survivors.

- This review found that when remote modes of intervention delivery were compared to ‘in person’ delivery of an intervention, there were no significant differences in outcome. This finding is of specific importance to hard-to-reach and vulnerable populations whom might be unwilling to access care at hospitals and registered clinics. More research focused on the use of remote support interventions among vulnerable populations (specifically IPV survivors), should be encouraged.

- There was a lot of heterogeneity in outcome measurements, especially measures of social support, drawing attention to the need for research and discussions around standardization and synthesis of evidence-based research on social support and IPV.

- In some of the studies, the ‘dosage of the intervention’, as well as some participant characteristics like age or ethnicity are often cited as potential moderators of some of the outcomes, more research on IPV intervention should examine the time dependent nature of interventions and their effect on outcomes similar to what was done by Bybee et al[ 16 ].

Limitations

Although there were no language restrictions included in our search strategy, most of the studies retrieved and subsequently reviewed were in English, which could have influenced some of our conclusions.

Conclusions

This systematic review presented the findings from IPV interventions focused on social support and mental health outcomes for IPV survivors. Advocacy/case management interventions that had strong linkages with communities, and were community focused seemed to have significant effects on mental health outcomes and access to resources for IPV survivors. However, all IPV survivors are not the same, and culture, socioeconomic background and the perception of abuse by the IPV survivor, have a mediating effect on their decision to access social support and utilize referral services. ‘An intersectional trauma informed practice’[ 50 ] [ 52 ] that addresses psychological and physical effects of IPV, is culturally appropriate and is empowering for the survivor, in addition to a ‘social network oriented approach’ might provide a way to ensure that IPV interventions are responsive to the needs of the IPV survivor[ 47 ]. This will ensure the interventions are targeted at ensuring survivors are able to access social support from their existing networks or new social relationships, and might also promote community education about IPV and promote community support for IPV prevention and mitigation. Future studies on IPV interventions should assess how these approaches impact the incidence of IPV, social and mental health outcomes across different populations’ of IPV survivors.

Supporting information

S1 checklist. prisma 2009 checklist..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235177.s001

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 2. Breiding M, Basile KC, Smith SG, Black MC, Mahendra RR. Intimate partner violence surveillance: Uniform definitions and recommended data elements. Version 2.0. 2015.

- 12. Thomas H. Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies. Toronto: Effective Public Health Practice Project McMaster University; 2003.

- 14. Programme CAS. CASP Qualitative Research Checklist. 2018.

- 43. McLeroy KR, Norton BL, Kegler MC, Burdine JN, Sumaya CV. Community-based interventions. American Public Health Association; 2003.

- Publisher Home

- Editorial Board

- Submit Manuscript

REVIEW ARTICLE

Intimate partner violence: a literature review, article information.

Identifiers and Pagination:

Article history:, article metrics, crossref citations:, total statistics:, unique statistics:.

Background:

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) is a complex issue that appears to be more prevalent in developing nations. Many factors contribute to this problem.

This article aimed to review and synthesize available knowledge on the subject of Intimate Partner Violence. It provides specific information that fills the knowledge gap noted in more global reports by the World Health Organization.

A literature search was conducted in English and Spanish in EBSCO and Scopus and included the keywords “Intimate, Partner, Violence, IPV.” The articles included in this review cover the results of empirical studies published from 2004 to 2020.

The results show that IPV is associated with cultural, socioeconomic, and educational influences. Childhood experiences also appear to contribute to the development of this problem.

Conclusion:

Only a few studies are focusing on empirically validated interventions to solve IPV. Well-implemented cultural change strategies appear to be a solution to the problem of IPV. Future research should focus on examining the results of strategies or interventions aimed to solve the problem of IPV.

1. INTRODUCTION

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) is the most prevalent type of violence against women worldwide. It is defined as a “behavior by an intimate partner or ex-partner that causes physical, sexual or psychological harm, including physical aggression, sexual coercion, psychological abuse, and controlling behaviors” [ 1 ]. The United Nations has defined violence against women as “any act of gender-based violence that results in or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life” [ 2 ].

The percentage of women experiencing violence in various parts of the world has been recorded. Different factors appear to influence the incidence of this worldwide problem. However, there are no single studies that summarize findings on the subject. The aim of this article was to review available knowledge regarding Intimate Partner Violence. There is a need to understand this problem so that viable solutions and or preventive measures could be implemented.

2. METHODOLOGY

2.1. searching strategy.

The literature search was conducted in English and Spanish using EBSCO (Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, Academic Search Premier, and Fuente Academica Premiere) and Scopus. It included the keywords “Intimate, Partner, Violence, IPV” and thematic issues on the subject, such as “depression, anxiety, body, ache.” Only the findings of empirical studies were considered. The articles ranged from 2004 to 2020. The analysis of full texts of articles was carried out several times and data were extracted according to the aim of this study.

3.1. Percentage of Women Experiencing Violence

Data presented by Women UN (2019) indicates that approximately 35 percent of women worldwide have experienced some form of violence in their lifetime [ 3 ]. One-third of women worldwide who have ever been involved in a relationship have experienced physical or sexual violence inflicted by an intimate partner [ 4 ].

With a focus on the Americas, the percentage of women who have experienced physical or sexual IPV in the past 12 months progressively increases as one examines data from North, Central and South America (1.1% in Canada, 6.6% in the United States, 7.8% in Costa Rica, and 27.1% in Bolivia) [ 5 ]. Compared to countries in Central and South America, Bolivia reports the highest percentage (52.3%) of women ever experiencing physical violence by an intimate partner. However, the percentage of women reporting ever experiencing sexual violence by an intimate partner was similar across nations ( i.e. , Bolivia 15.2%, Nicaragua 13.1%, Guatemala 12.3%, Colombia 11.8%, Ecuador 11.5%, El Salvador 11.5%, Haiti 10.8%, and Peru 9.4%). Moreover, the percentage of women who reported ever experiencing IPV in the form of emotional abuse (insults, humiliation, intimidation, and threats of harm) also occurred relatively equally across nations ( e.g. , Nicaragua 47.8%, El Salvador 44.2%, Guatemala 42.2%, Colombia, 41.5%, Ecuador 40.7%), with a few exceptions (Haiti 17.0%, Dominican Republic 26.1%) [ 6 ].

Data from Colombia indicates that 31.1% of women in that country reported experiencing economic or patrimonial violence from an intimate partner, 7.6% experienced IPV in the form of sexual violence, and 64% experienced psychological violence from a partner [ 7 ]. Similar numbers have been recorded in Ecuador. The National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INEC 2019) notes that 43 out of 100 women in the country have experienced some form of IPV. Of this group, 40.8% of women reported experiencing psychological violence ( e.g. , humiliation, insults, being threatened with a weapon), 25% said they were victims of physical violence and 8.3% were victims of sexual violence [ 8 ].

3.2. Social Norms and Sociodemographic Factors

Women must contend with societal norms related to domestic violence. For example, in some countries, male dominance or patriarchal systems in which the wife is considered a possession or property of the husband are considered the societal norm. Some studies have shown that social attitudes justifying and or accepting IPV in some developing nations or specific localities increase the incidence of this problem in those areas. Women in these places are likely more tolerant of this problem if it were to happen to them and are less likely to leave a violent relationship [ 9 - 12 ]. Likewise, exposure to violence perpetrated by political groups ( e.g. , police, armed forces) also seems to increase the prevalence of IPV in nations [ 13 - 15 ].

Sociodemographic factors also appear to affect the prevalence of IPV. Studies around the globe indicate that a low level of education in women may put them at a higher risk for IPV [ 16 - 19 ]. This low level of educational attainment could be related to existent socioeconomic disadvantages, a culturally upheld belief that women do not need education because their assigned role is to stay at home and take care of household duties, including the raising of children, and a lack of a network of support that could potentially encourage their educational advancement. For example, a recent study suggested that Latinas who experience IPV “tend to be younger, have more socioeconomic disadvantage, and are fearful of seeking help from authorities” [ 20 ].

The marital status of female victims of IPV has been extensively studied, with common findings of IPV appearing to happen less often to married women in comparison to divorced or separated women in most countries [ 21 , 22 ]. However, the findings must be considered within cultural contexts. As previously stated, in some countries, married women are viewed as property of the husband, and physical aggression or violence towards the wife is tolerated or accepted within the culture. In general, cohabitating couples worldwide report higher rates of IPV. The higher rates could be related to socioeconomic status or to the perception that the relationship is less permanent. More studies need to address the contributing factors as to why cohabitating women tend to have a higher rate of IPV compared to married women, as well as examine the norms by varying cultures and their effect on IPV. Single women typically report less rates of IPV in comparison to married, divorced or separated women. However, this trend appears to vary by country. Single women in Canada and Australia, for example, report higher rates of IPV in comparison to married women in these two nations [ 22 ]. Possible contributing factors for the increase in IPV among single women in Canada and Australia could be related to age or to lifestyle choices. Riskier lifestyles could potentially expose younger women to a greater chance of experiencing intimate partner violence. Latin American and Caribbean nations, data indicate that IPV typically occurs more often among urban women in comparison to rural women [ 23 ]. Nonetheless, some studies in the United States suggest that IPV typically occurs more often in rural settings and small towns [ 24 , 25 ]. Further studies are needed to address the underlying causes of the link between sociodemographic factors and IPV.

3.3. Childhood Victimization

In addition to possible social factors influencing the rates of IPV, women impacted by childhood victimization can experience long term negative effects, and data suggest that “childhood victimization and domestic violence are highly correlated” [ 26 ]. For example, women who witnessed IPV during their childhood are more prone to experiencing IPV as adults [ 27 - 30 ]. Similarly, studies suggest that women who have been physically abused [ 31 - 34 ] or sexually abused [ 35 - 38 ] in childhood also are more likely to experience IPV in adulthood.

3.4. Mental Health

Research has shown that women who experienced IPV report increased levels of mental health symptomatology. For example, women who were abused by an intimate partner reported increased symptoms of depression, anxiety [ 39 , 40 ], and obsessive-compulsive characteristics [ 40 ]. Similarly, women exposed to IPV and who present depressive symptoms exhibit significant weight gain [ 41 ]. Low-income post-partum women in Brazil who experienced IPV are at a greater risk of presenting suicidal ideation [ 42 ], and women living in poverty in Nicaragua who were victims of IPV and perceived they did not receive social support from their families were more likely to indicate they had attempted suicide at some point in their lives [ 43 ]. There appears to be a bidirectional relationship between IPV and mental health problems. More specifically, at least one study has shown that women who experienced child abuse and subsequently developed mental health illnesses ( i.e. , Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, symptoms of depression, binge drinking) were more likely to experience IPV during adulthood [ 44 ].

3.5. Health Complains and Illnesses

In addition to mental health ailments, women victims of intimate partner violence (IPV), in its many forms, have self-reported having frequent health complaints and illnesses. Because of the complexity of physical ailments and symptoms, research studies are limited in addressing the specific correlations of physical health and IVP [ 45 ]. For example, Onur et al. (2020) wrote that women diagnosed with Fibromyalgia Syndrome (characterized by chronic musculoskeletal pain) also reported being victims of partner violence (physical, social, economic, and emotional) [ 46 ]. Raya et al. (2004) observed that Andalusian women victims of IPV perpetration were more likely to suffer from hypertension and asthma [ 47 ]. More recently, Soleimania et al. (2017) observed that Iranian women who had experienced IPV in the form of psychological abuse had a greater incidence of somatic symptoms than women who had not experienced any form of abuse [ 48 ]. There appears to be an additive effect on the body when it comes to experiencing abuse. Women who have experienced various forms of abuse in their life ( e.g. , child abuse, past IPV, present IPV, and financial problems) have reported higher levels of somatic complaints in comparison to women who had only experienced IPV [ 49 ]. At least one study noticed that there was a greater incidence of type 2 diabetes in women who reported experiencing physical intimate partner violence [ 50 ].

3.6. Utilization of Health Care Providers

Aside from the various somatic complaints that are being described by women who have experienced IVP, Lo Fo Wong, et al. (2007), observed that women who had been physically and psychologically abused by their partners used healthcare providers more often and were also prescribed pain medication more frequently [ 51 ]. Also, Comeau, et al. (2012) noticed that women who had been abused by their intimate partners used antidepressants to deal with symptoms of depression [ 52 ]. Lastly, higher use of anxiolytics and antidepressants also has been observed in women who had suffered intimate partner violence [ 53 ].

3.7. Use of Cigarettes

Aside from using various types of medications, Sullivan et al. (2015) noticed that women who had been victims of IPV tend to smoke greater quantities of cigarettes in comparison to women who have not experienced violence [ 54 ]. Furthermore, it has also been observed that women who experienced perinatal IPV were twice as likely to smoke cigarettes in comparison to women without a history of IPV [ 55 ]. It is worth noting that smoking during pregnancy is a strong predictor of low birth weight [ 55 - 57 ] and preterm birth [ 58 ]. Children born under these circumstances are more prone to being described as having more social problems, attention problems, as well as anxiety and depression by age 7 [ 59 ] and low birth weight adolescents show increased levels of mental health problems (emotional symptoms, social problems, and attention deficit) [ 60 ].

3.8. Current Scenario

Many contributing factors impact women suffering from intimate partner violence. These influences could be cultural, socioeconomic, political, and educational, to name a few. Major findings support the notion that women, who are less educated, socioeconomically disadvantaged, reside in patriarchal societies, or cohabitate are at greater risk of IPV. Another contributing factor is mental health symptomology. Further analysis is needed to better understand the correlation between mental health issues and IPV. Is poor mental health a precursor to IPV, or is IPV a potential cause for poor mental health? Various cultures have differing views pertaining to the topic of mental health and address this problem differently. Without proper treatment and proper advocacy for mental health, some women may feel caught in a cycle of hopelessness, stay in abusive relationships, and contribute to the social perception that IPV is an acceptable way of life.

With the current global crisis of COVID-19 and governments issuing stay-at-home orders, psychologists predict an increase in intimate partner violence. The Secretary-General of the United Nations stated the orders have led to a “horrifying global surge” in IPV [ 61 ]. Because of the difficulty to flee from the abusers, women may be at an even higher risk of “IPV-related health issues” [ 61 ]. The global pandemic is a major contributing factor to job loss, economic stress, and evictions. Economic crisis can potentially negatively impact relationships, regardless of marital status. With the looming effects of the pandemic, the World Health Organization will need to consider the level of depression, anxiety, stress, marital status, and socioeconomic status in women across varying cultures, and how the pandemic may have contributed to an increase in IPV.

3.9. Interventions

Empirically validated interventions aimed to address IPV are scarce. One study observed positive results through the implementation of a culturally relevant program with immigrants of Mexican origin. Specifically, the study observed that Latino men benefited from attending group sessions aimed to address, among others, their histories of childhood maltreatment, their challenges encountering different gender roles as they moved to the United States, their sense of control over their wives, and the development of “unequal but non-abusive relationships”. The program included teaching men non-aggressive strategies and problem-solving skills through role-plays. Through these interventions, men became more understanding of their wives’ experiences, as they transition to the United States, learned the impact of their aggressive behavior, and also learned to cooperate more within the home [ 62 ]. In addition to this report, another study focused on the empowerment of Latino women through the Moms’ Empowerment Program. This intervention included providing advocacy services and social support to women. It targeted women’s self-blame for experiencing IPV and helped women set forth goals to promote change in their lives while focusing on preserving their children’s safety. Overall, the program appeared to be successful in helping reduce women’s exposure to mild violence and physical assaults [ 63 ]. Another recent study carried out in Brazil observed positive results with the implementation of cognitive-behavioral interventions in women victims of IPV. Thirteen sessions with a weekly frequency, which included, among others, psychoeducation, problem-solving, and cognitive restructuring, showed effectiveness in reducing women's anxiety and depression and increasing their life satisfaction [ 64 ]. Aside from individual or group interventions, one study carried in Ghana examined the utilization of community-based structures ( i.e. , police, health and welfare organizations, and religious leaders) to raise awareness to the problem of violence against women, to guide talks about gender equality, challenge social norms that endorse violence, provide counseling services to couples experiencing IPV, and create referral structures to help victims.. The prevalence of IPV in the communities that received these types of interventions was lower than that of those areas that did not receive these services [ 65 ].

IVP is a complex issue that needs continued research and attention to provide better interventions. Global findings indicate that certain cultural groups are more tolerant of this problem and that they may tend to normalize it and/or accept it. Overall, IPV is more widespread in developing nations, especially those experiencing political-related-violence. Considering these findings, World Health Organization surveys and future studies should consider assessing the incidence of IPV among immigrants to the United States with histories of having experienced political violence. A study in 2008 showed that eleven percent of immigrant Latinos to the United States had experienced political violence in their countries of origin. Latino women who had lived this type of violence also reported experiences of feeling discriminated [ 66 ]. Future studies should focus their attention on clarifying these findings and their possible relationship with IPV, so that prompt interventions with immigrant populations could be developed.

A recent study shows that Hispanics and Blacks in the United States constantly worry about possibly experiencing violence perpetrated by police, a form of political violence. Hispanics worry about police violence four times more than Whites and Blacks worry about this type of violence five times more than Whites [ 67 ]. Considering these results, the WHO should also explore if reports of police brutality in black or immigrant communities in the United States correlate to rates of IPV in these communities.

Although there is ample information about the various factors associated with IPV, only a few studies have focused on examining empirically validated interventions to address it. Without this knowledge, it would be impossible to truly know if available interventions work or not. Research findings suggest that women, and in particular women from marginalized groups, should receive assistance and guidance to gain access to higher education institutions. Their educational attainment likely will become a protective factor in their life that could prevent them from ever experiencing IPV. Parity in access to higher-paying jobs likely could help reduce the prevalence of IPV. Well-implemented cultural change strategies also appear to be a solution to the problem of IPV. Societal structures ( e.g. , law, religion) and organizations ( e.g. , welfare) seem to be key participants in the development of respectful and nonviolent relationships between men and women that likely could prevent IPV from ever taking place. Early detection of violence within the home and follow-up interventions could prevent children from normalizing such behavior. Health care system screenings could detect early signs and symptomatology of IPV. These screenings could potentially ensure that multisystem interventions be implemented to disrupt the development of IPV and provide survivors with needed support. Lastly, research suggests that governments and their officials should refrain from endorsing politically violent acts. Governmental acts of violence likely could endorse or ignite the problem of IPV in nations.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.

Track Your Manuscript

Published contents, about the editor, journal metrics, readership statistics:, total views/downloads: 2,749,815, unique views/downloads: 594,588, about the journal, table of contents.

- INTRODUCTION

- Searching Strategy

- Percentage of Women Experiencing Violence

- Social Norms and Sociodemographic Factors

- Childhood Victimization

- Mental Health

- Health Complains and Illnesses

- Utilization of Health Care Providers

- Use of Cigarettes

- Current Scenario

- Interventions

Press Release

Bentham open welcomes sultan idris university of education (upsi) as institutional member.

Bentham Open is pleased to welcome Sultan Idris University of Education (UPSI), Malaysia as Institutional Member. The partnership allows the researchers from the university to publish their research under an Open Access license with specified fee discounts. Bentham Open welcomes institutions and organizations from world over to join as Institutional Member and avail a host of benefits for their researchers.

Sultan Idris University of Education (UPSI) was established in 1922 and was known as the first Teacher Training College of Malaya. It is known as one of the oldest universities in Malaysia. UPSI was later upgraded to a full university institution on 1 May, 1997, an upgrade from their previous college status. Their aim to provide exceptional leadership in the field of education continues until today and has produced quality graduates to act as future educators to students in the primary and secondary level.

Bentham Open publishes a number of peer-reviewed, open access journals. These free-to-view online journals cover all major disciplines of science, medicine, technology and social sciences. Bentham Open provides researchers a platform to rapidly publish their research in a good-quality peer-reviewed journal. All peer-reviewed accepted submissions meeting high research and ethical standards are published with free access to all.

Ministry Of Health, Jordan joins Bentham Open as Institutional Member

Bentham Open is pleased to announce an Institutional Member partnership with the Ministry of Health, Jordan . The partnership provides the opportunity to the researchers, from the university, to publish their research under an Open Access license with specified fee concessions. Bentham Open welcomes institutions and organizations from the world over to join as Institutional Member and avail a host of benefits for their researchers.

The first Ministry of Health in Jordan was established in 1950. The Ministry began its duties in 1951, the beginning of the health development boom in Jordan. The first accomplishment was the establishment of six departments in the districts headed by a physician and under the central administration of the Ministry. The Ministry of Health undertakes all health affairs in the Kingdom and its accredited hospitals include AL-Basheer Hospital, Zarqa Governmental Hospital, University of Jordan Hospital, Prince Hashem Military Hospital and Karak Governmental Hospital.

Bentham Open publishes a number of peer-reviewed, open access journals. These free-to-view online journals cover all major disciplines of science, medicine, technology and social sciences. Bentham Open provides researchers a platform to rapidly publish their research in a good-quality peer-reviewed journal. All peer-reviewed, accepted submissions meeting high research and ethical standards are published with free access to all.

Porto University joins Bentham Open as Institutional Member

Bentham Open is pleased to announce an Institutional Member partnership with the Porto University, Faculty of Dental Medicine (FMDUP) . The partnership provides the opportunity to the researchers, from the university, to publish their research under an Open Access license with specified fee concessions. Bentham Open welcomes institutions and organizations from world over to join as Institutional Member and avail a host of benefits for their researchers.

The Porto University was founded in 1911. Porto University create scientific, cultural and artistic knowledge, higher education training strongly anchored in research, the social and economic valorization of knowledge and active participation in the progress of the communities in which it operates.

Join Our Editorial Board

The Open Psychology Journal is an Open Access online journal, which publishes research articles, reviews, letters, case reports and guest-edited single topic issues in all areas of psychology. Bentham Open ensures speedy peer review process and accepted papers are published within 2 weeks of final acceptance.

The Open Psychology Journal is committed to ensuring high quality of research published. We believe that a dedicated and committed team of editors and reviewers make it possible to ensure the quality of the research papers. The overall standing of a journal is in a way, reflective of the quality of its Editor(s) and Editorial Board and its members.

The Open Psychology Journal is seeking energetic and qualified researchers to join its editorial board team as Editorial Board Members or reviewers.

- Experience in psychology with an academic degree.

- At least 20 publication records of articles and /or books related to the field of psychology or in a specific research field.

- Proficiency in English language.

- Offer advice on journals’ policy and scope.

- Submit or solicit at least one article for the journal annually.

- Contribute and/or solicit Guest Edited thematic issues to the journal in a hot area (at least one thematic issue every two years).

- Peer-review of articles for the journal, which are in the area of expertise (2 to 3 times per year).

If you are interested in becoming our Editorial Board member, please submit the following information to [email protected] . We will respond to your inquiry shortly.

- Email address

- City, State, Country

- Name of your institution

- Department or Division

- Website of institution

- Your title or position

- Your highest degree

- Complete list of publications and h-index

- Interested field(s)

Testimonials

"Open access will revolutionize 21 st century knowledge work and accelerate the diffusion of ideas and evidence that support just in time learning and the evolution of thinking in a number of disciplines."

"It is important that students and researchers from all over the world can have easy access to relevant, high-standard and timely scientific information. This is exactly what Open Access Journals provide and this is the reason why I support this endeavor."

"Publishing research articles is the key for future scientific progress. Open Access publishing is therefore of utmost importance for wider dissemination of information, and will help serving the best interest of the scientific community."

"Open access journals are a novel concept in the medical literature. They offer accessible information to a wide variety of individuals, including physicians, medical students, clinical investigators, and the general public. They are an outstanding source of medical and scientific information."

"Open access journals are extremely useful for graduate students, investigators and all other interested persons to read important scientific articles and subscribe scientific journals. Indeed, the research articles span a wide range of area and of high quality. This is specially a must for researchers belonging to institutions with limited library facility and funding to subscribe scientific journals."

"Open access journals represent a major break-through in publishing. They provide easy access to the latest research on a wide variety of issues. Relevant and timely articles are made available in a fraction of the time taken by more conventional publishers. Articles are of uniformly high quality and written by the world's leading authorities."

"Open access journals have transformed the way scientific data is published and disseminated: particularly, whilst ensuring a high quality standard and transparency in the editorial process, they have increased the access to the scientific literature by those researchers that have limited library support or that are working on small budgets."

"Not only do open access journals greatly improve the access to high quality information for scientists in the developing world, it also provides extra exposure for our papers."

"Open Access 'Chemistry' Journals allow the dissemination of knowledge at your finger tips without paying for the scientific content."

"In principle, all scientific journals should have open access, as should be science itself. Open access journals are very helpful for students, researchers and the general public including people from institutions which do not have library or cannot afford to subscribe scientific journals. The articles are high standard and cover a wide area."

"The widest possible diffusion of information is critical for the advancement of science. In this perspective, open access journals are instrumental in fostering researches and achievements."

"Open access journals are very useful for all scientists as they can have quick information in the different fields of science."

"There are many scientists who can not afford the rather expensive subscriptions to scientific journals. Open access journals offer a good alternative for free access to good quality scientific information."

"Open access journals have become a fundamental tool for students, researchers, patients and the general public. Many people from institutions which do not have library or cannot afford to subscribe scientific journals benefit of them on a daily basis. The articles are among the best and cover most scientific areas."

"These journals provide researchers with a platform for rapid, open access scientific communication. The articles are of high quality and broad scope."

"Open access journals are probably one of the most important contributions to promote and diffuse science worldwide."

"Open access journals make up a new and rather revolutionary way to scientific publication. This option opens several quite interesting possibilities to disseminate openly and freely new knowledge and even to facilitate interpersonal communication among scientists."

"Open access journals are freely available online throughout the world, for you to read, download, copy, distribute, and use. The articles published in the open access journals are high quality and cover a wide range of fields."

"Open Access journals offer an innovative and efficient way of publication for academics and professionals in a wide range of disciplines. The papers published are of high quality after rigorous peer review and they are Indexed in: major international databases. I read Open Access journals to keep abreast of the recent development in my field of study."

"It is a modern trend for publishers to establish open access journals. Researchers, faculty members, and students will be greatly benefited by the new journals of Bentham Science Publishers Ltd. in this category."

Intimate Partner Violence: A Bibliometric Review of Literature

Affiliations.

- 1 Institute of Information Resource, Zhejiang University of Technology, Hangzhou 310014, China.

- 2 Library, Zhejiang University of Technology, Hangzhou 310014, China.

- PMID: 32759637

- PMCID: PMC7432288

- DOI: 10.3390/ijerph17155607

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a worldwide public health problem. Here, a bibliometric analysis is performed to evaluate the publications in the Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) field from 2000 to 2019 based on the Science Citation Index (SCI) Expanded and the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) databases. This work presents a detailed overview of IPV from aspects of types of articles, citations, h-indices, languages, years, journals, institutions, countries, and author keywords. The results show that the USA takes the leading position in this research field, followed by Canada and the U.K. The University of North Carolina has the most publications and Harvard University has the first place in terms of h-index. The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine leads the list of average citations per paper. The Journal of Interpersonal Violence , Journal of Family Violence and Violence Against Women are the top three most productive journals in this field, and Psychology is the most frequently used subject category. Keywords analysis indicates that, in recent years, most research focuses on the research fields of "child abuse", "pregnancy", "HIV", "dating violence", "gender-based violence" and "adolescents".

Keywords: HIV; bibilometric; intimate partner violence; keywords analysis; violence.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Bibliometrics*

- Child, Preschool

- Cohort Studies

- Intimate Partner Violence*

Exposure to Family Violence and School Bullying Perpetration among Children and Adolescents: Serial Mediating Roles of Parental Support and Depression

- Published: 12 April 2024

Cite this article

- Wei Nie 1 &

- Liru Gao ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5739-0180 2

14 Accesses

Explore all metrics

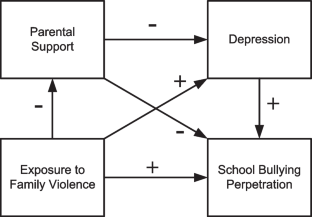

Previous studies have found links of intimate partner violence exposure and child maltreatment with school bullying among children and adolescents. However, little is known about how exposure to family violence may influence child and adolescent bullying perpetration and the mediating mechanism underlying this relationship. This study aimed to examine the relationship between exposure to family violence and school bullying perpetration, as well as the mediating roles of parental support and depression in this relationship. The sample consisted of 3,199 Chinese primary and secondary school students from grades four through twelve (mean age 13.4 years, 50.8% boys). Participants responded to validated self-report questionnaires in 2021. Generalized structural equation modeling was analyzed. The study found that exposure to family violence was significantly and positively associated with school bullying perpetration. Furthermore, parental support and depression, in this order, mediated the effect of exposure to family violence on bullying perpetration. Moreover, the overall mediating effect on traditional bullying perpetration is larger than that on cyber bullying perpetration. Less parental support and depression acted as risk factors for the negative effect of exposure to family violence on child and adolescent bullying perpetration. The importance of these two factors can motivate future intervention initiatives to prevent bullying perpetration from an integrated perspective.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

References

Ainsworth, M. D. (1989). Attachments beyond infancy. American Psychologist, 44 , 709–716. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.4.709

Article Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorder (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

Book Google Scholar

Arslan, G., Allen, K. A., & Tanhan, A. (2021). School bullying, mental health, and wellbeing in adolescents: Mediating impact of positive psychological orientations. Child Indicators Research, 14 , 1007–1026. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-020-09780-2

Baek, H., Roberts, A. M., Seepersad, R., & Swartz, K. (2019). Examining negative emotions as mediators between exposures to family violence and bullying: A gendered perspective. Journal of School Violence, 18 (3), 440–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2018.1519441

Baldry, A. C. (2003). Bullying in schools and exposure to domestic violence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27 (7), 713–732. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(03)00114-5

Benhorin, S., & McMahon, S. D. (2008). Exposure to violence and aggression: Protective roles of social support among urban African American youth. Journal of Community Psychology, 36 (6), 723–743. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20252

Blum, R. W., Li, M., & Naranjo-Rivera, G. (2019). Measuring adverse child experiences among young adolescents globally: Relationships with depressive symptoms and violence perpetration. Journal of Adolescent Health, 65 (1), 86–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.01.020

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Attachment (Vol. 1). Basic Books.

Google Scholar

Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and loss: Loss, sadness and depression (Vol. 3). Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Parent–child attachment and healthy human development . Routledge.

Campbell, A. M. (2020). An increasing risk of family violence during the Covid-19 pandemic: Strengthening community collaborations to save lives. Forensic Science International: Reports, 2 , 100089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsir.2020.100089

Che, Y., Lu, J., Fang, D., Ran, H., Wang, S., Liang, X., Sun, H., Peng, J., Chen, L., & Xiao, Y. (2022). Association between school bullying victimization and self-harm in a sample of Chinese children and adolescents: The mediating role of perceived social support. Frontiers in Public Health, 10 , 995546. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.995546

Chesworth, B., Lanier, P., & Rizo, C. F. (2019). The association between exposure to intimate partner violence and child bullying behaviors. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28 , 2220–2231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01439-z