Substance and Non-Substance Related Addictions pp 205–209 Cite as

Drug Policy

- Olaniyi Olayinka 2

- First Online: 03 January 2022

996 Accesses

Drug policies play a role in protecting the public’s health and reducing drug-related crimes at the local, national, and international levels. This chapter mainly focuses on key drug control treaties and policies, providing a brief historical context on how some of the policies were established. The goal is to present the reader with a general overview of international drug policies and how they might apply to drug control nationally.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Degenhardt L, Hall W. Extent of illicit drug use and dependence, and their contribution to the global burden of disease. Lancet. 2012;379(9810):55–70.

Article Google Scholar

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report 2018. 2018. Available from: https://www.unodc.org/wdr2018/prelaunch/WDR18_Booklet_1_EXSUM.pdf .

Crowley R, Kirschner N, Dunn AS, Bornstein SS. Health and public policy to facilitate effective prevention and treatment of substance use disorders involving illicit and prescription drugs: an American College of Physicians position paper. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(10):733–6.

Ammerman S, Ryan S, Adelman WP, Abuse CS. The impact of marijuana policies on youth: clinical, research, and legal update. Pediatrics. 2015;peds:2014–4147.

Google Scholar

MacGregor S, Singleton N, Trautmann F. Towards good governance in drug policy: evidence, stakeholders and politics. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(5):931–4.

Sweileh WM, Zyoud SH, Al-Jabi SW, Sawalha AF. Substance use disorders in Arab countries: research activity and bibliometric analysis. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2014;9:33.

United Nations. The international drug control conventions. Vienna 2013. Available from: http://www.unodc.org/documents/commissions/CND/Int_Drug_Control_Conventions/Ebook/The_International_Drug_Control_Conventions_E.pdf .

Cooper HL, Linton S, Kelley ME, Ross Z, Wolfe ME, Chen Y-T, et al. Racialized risk environments in a large sample of people who inject drugs in the United States. Int J Drug Policy. 2016;27:43–55.

Pauly B. Harm reduction through a social justice lens. Int J Drug Policy. 2008;19(1):4–10.

World Health Organization. Guidance on the WHO review of psychoactive substances for international control. 2010. Available from: http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/quality_safety/GLS_WHORev_PsychoactSubst_IntC_2010.pdf .

United Nations. United Nations treaty collection. 2018. Available from: https://treaties.un.org/pages/viewdetails.aspx?src=treaty&mtdsg_no=vi-16&chapter=6&lang=en .

Beletsky L, Davis CS. Today’s fentanyl crisis: Prohibition’s Iron Law, revisited. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;46:156–9.

Cooper HL. War on drugs policing and police brutality. Subst Use Misuse. 2015;50(8–9):1188–94.

Astorga L, Shirk DA. Drug trafficking organizations and counter-drug strategies in the US-Mexican context. 2010.

BBC News. Canada becomes second country to legalise recreational cannabis. 2018. Available from: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-45806255 .

Hetzer H, Walsh J. Pioneering cannabis regulation in Uruguay. NACLA Rep Am. 2014;47(2):33–5.

Volkow ND, Baler RD, Compton WM, Weiss SR. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(23):2219–27.

Wilkinson ST, Yarnell S, Radhakrishnan R, Ball SA, D’Souza DC. Marijuana legalization: impact on physicians and public health. Annu Rev Med. 2016;67:453–66.

Watson TM, Erickson PG. Cannabis legalization in Canada: how might ‘strict’ regulation impact youth? Taylor & Francis; 2018.

World Health Organization. Cannabis and cannabis resin. 2014. Available from: http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/quality_safety/8_2_Cannabis.pdf .

Kolodny A, Courtwright DT, Hwang CS, Kreiner P, Eadie JL, Clark TW, et al. The prescription opioid and heroin crisis: a public health approach to an epidemic of addiction. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:559–74.

Volkow ND, Frieden TR, Hyde PS, Cha SS. Medication-assisted therapies—tackling the opioid-overdose epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2063–6.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Interfaith Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY, USA

Olaniyi Olayinka

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Psychiatry New Jersey Medical School, Rutgers University, Newark, NJ, USA

Evaristo Akerele

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Olayinka, O. (2022). Drug Policy. In: Akerele, E. (eds) Substance and Non-Substance Related Addictions. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-84834-7_18

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-84834-7_18

Published : 03 January 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-84833-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-84834-7

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Introduction

- Conclusions

- Article Information

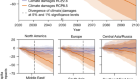

Figure shows the cumulative number of opioid-related state policies implemented, with Medicaid expansion included as a control (A), the number of enacted state policies as of 2018 (B), and the transition rate of the state policies (C). PDMP indicates prescription drug monitoring program.

The error bars represent the 95% CIs, and the shaded backgrounds represent positive (orange) and negative (blue) associations. The solid horizontal line represents the estimated mean effect size across all quarterly effect sizes from random-effects meta-analysis models. Quarters are a period of three months. MAT indicates medication-assisted treatment; open circle, 95% CIs overlap with 0; OUD, opioid use disorder; solid circle, 95% CIs do not overlap with 0.

The error bars represent the 95% CIs, and the shaded backgrounds represent positive (orange) and negative (blue) associations. Open circles indicate that 95% CIs overlap with 0; solid circle, 95% CIs do not overlap with 0.

eAppendix 1. Introduction to Optum Database

eAppendix 2. State Policies

eAppendix 3. Application of Panel Matching Under the Parallel Trends Assumption

eTable 1. Population Coverage of the Optum Database by State

eTable 2. International Classification of Diseases (ICD), Ninth and Tenth Revision Codes to Identify Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) and Overdose Diagnosis (OD)

eTable 3. Characteristics of the Study Samples From the Optum Database

eTable 4. Summary Statistics for Six Indicators Across Medicare Beneficiary Status

eTable 5. Overdose Death Counts Across Different Causes of Death

eTable 6. Mandatory PDMP Implementation Dates

eTable 7. State Policy Implementation Dates

eTable 8. The Meta-Analysis of Quarterly Effects of State Policy Implementation on Indicators of Prescription Opioid Misuse and Opioid Overdose From a Commercially Insured Population

eTable 9. The Meta-Analysis of Quarterly Effects of State Policy Implementation on Overdose Deaths

eFigure 1. Illustration of Parallel Trends Assumption Under the Difference-in-Difference Framework: The Impact of Mandatory PDMPs on All Overdose Deaths

eFigure 2. Pre-Post Trends for Six Outcomes From a Commercially Insured Population Across Six Policies

eFigure 3. Pre-Post Trends for Different Types of Drug-Related Deaths Across Six Policies

eFigure 4. Trends for Major Outcomes

eFigure 5. The Association of State Policy Implementation With Indicators of Prescription Opioid Misuse and Opioid Overdose From a Commercially Insured Population

eFigure 6. The Association of State Policy Implementation With Different Types of Drug Overdose Deaths

eTable 10. Regression Tables for Effects of State Policies on All Outcomes With 95% Confidence Intervals

eReferences

- Error in the Supplement JAMA Network Open Correction March 10, 2021

See More About

Sign up for emails based on your interests, select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Get the latest research based on your areas of interest.

Others also liked.

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

Lee B , Zhao W , Yang K , Ahn Y , Perry BL. Systematic Evaluation of State Policy Interventions Targeting the US Opioid Epidemic, 2007-2018. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2036687. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36687

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

Systematic Evaluation of State Policy Interventions Targeting the US Opioid Epidemic, 2007-2018

- 1 Department of Sociology, Indiana University-Bloomington, Bloomington

- 2 Luddy School of Informatics, Computing, and Engineering, Indiana University-Bloomington, Bloomington

- 3 Network Science Institute, Department of Sociology, Indiana University-Bloomington, Bloomington

- Correction Error in the Supplement JAMA Network Open

Question Are US state drug policies associated with variation in opioid misuse, opioid use disorder, and drug overdose mortality?

Findings In this cross-sectional study of state-level drug overdose mortality data and claims data from 23 million commercially insured patients in the US between 2007 and 2018, state policies were associated with a reduction in known indicators of prescription opioid misuse as well as deaths from prescription opioid overdose and increases in diagnosis of opioid use disorder, overdose, and drug overdose mortality from illicit drugs.

Meaning Although existing state-level drug policies have been associated with a decrease in the misuse of prescription opioids, these policies may have had the unintended consequence of motivating those with opioid use disorders to switch to alternative illicit substances, inducing higher overdose mortality.

Importance In response to the increase in opioid overdose deaths in the United States, many states recently have implemented supply-controlling and harm-reduction policy measures. To date, an updated policy evaluation that considers the full policy landscape has not been conducted.

Objective To evaluate 6 US state-level drug policies to ascertain whether they are associated with a reduction in indicators of prescription opioid abuse, the prevalence of opioid use disorder and overdose, the prescription of medication-assisted treatment (MAT), and drug overdose deaths.

Design, Setting, and Participants This cross-sectional study used drug overdose mortality data from 50 states obtained from the National Vital Statistics System and claims data from 23 million commercially insured patients in the US between 2007 and 2018. Difference-in-differences analysis using panel matching was conducted to evaluate the prevalence of indicators of prescription opioid abuse, opioid use disorder and overdose diagnosis, the prescription of MAT, and drug overdose deaths before and after implementation of 6 state-level policies targeting the opioid epidemic. A random-effects meta-analysis model was used to summarize associations over time for each policy and outcome pair. The data analysis was conducted July 12, 2020.

Exposures State-level drug policy changes to address the increase of opioid-related overdose deaths included prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) access, mandatory PDMPs, pain clinic laws, prescription limit laws, naloxone access laws, and Good Samaritan laws.

Main Outcomes and Measures The outcomes of interests were quarterly state-level mortality from drug overdoses, known indicators for prescription opioid abuse and doctor shopping, MAT, and prevalence of drug overdose and opioid use disorder.

Results This cross-sectional study of drug overdose mortality data and insurance claims data from 23 million commercially insured patients (12 582 378 female patients [55.1%]; mean [SD] age, 45.9 [19.9] years) in the US between 2007 and 2018 found that mandatory PDMPs were associated with decreases in the proportion of patients taking opioids (−0.729%; 95% CI, −1.011% to −0.447%), with overlapping opioid claims (−0.027%; 95% CI, −0.038% to −0.017%), with daily morphine milligram equivalent greater than 90 (−0.095%; 95% CI, −0.150% to −0.041%), and who engaged in drug seeking (−0.002%; 95% CI, −0.003% to −0.001%). The proportion of patients receiving MAT increased after the enactment of mandatory PDMPs (0.015%; 95% CI, 0.002% to 0.028%), pain clinic laws (0.013%, 95% CI, 0.005%-0.021%), and prescription limit laws (0.034%, 95% CI, 0.020% to 0.049%). Mandatory PDMPs were associated with a decrease in the number of overdose deaths due to natural opioids (−518.5 [95% CI, −728.5 to −308.5] per 300 million people) and methadone (−122.7 [95% CI, −207.5 to −37.8] per 300 million people). Prescription drug monitoring program access policies showed similar results, although these policies were also associated with increases in overdose deaths due to synthetic opioids (380.3 [95% CI, 149.6-610.8] per 300 million people) and cocaine (103.7 [95% CI, 28.0-179.5] per 300 million people). Except for the negative association between prescription limit laws and synthetic opioid deaths (−723.9 [95% CI, −1419.7 to −28.1] per 300 million people), other policies were associated with increasing overdose deaths, especially those attributed to non–prescription opioids such as synthetic opioids and heroin. This includes a positive association between naloxone access laws and the number of deaths attributed to synthetic opioids (1338.2 [95% CI, 662.5 to 2014.0] per 300 million people).

Conclusions and Relevance Although this study found that existing state policies were associated with reduced misuse of prescription opioids, they may have the unintended consequence of motivating those with opioid use disorders to access the illicit drug market, potentially increasing overdose mortality. This finding suggests that there is no easy policy solution to reverse the epidemic of opioid dependence and mortality in the US.

The current opioid epidemic in the US has its historical roots in the movement during the 1990s to address undertreated chronic pain. In response, opioid-producing pharmaceutical companies engaged in aggressive marketing and prescribers overcorrected, relying on powerful opioid analgesics to treat acute and minor pain in addition to chronic and severe pain. Subsequently, the widespread use of opioid analgesic agents created demand for long-term and non-medical use of prescription and illicit opioids. 1 , 2 To address the growing opioid epidemic, policy makers have focused largely on controlling the prescription and use of opioid analgesics through the implementation of supply-side drug policies. These include prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs), pain clinic laws, and prescription limit laws to reduce inappropriate prescribing behavior. In tandem, policy measures to reduce harms and barriers associated with treating and reporting drug overdose, including naloxone access laws and Good Samaritan laws, have been introduced.

Previous studies have provided mixed evidence on the impact that these state policies have had on opioid misuse, nonfatal overdose, and opioid mortality. For example, some research indicates that access to a PDMP, which allows prescribers to review patients’ prescription histories, substantially reduces prescription of opioids by 6 percentage points and oxycodone distribution by 8 percentage points. 3 , 4 In contrast, other studies have found that PDMP access is ineffective 5 - 7 or is only effective if a review of patient records is mandatory. 8 , 9 Other types of policies such as naloxone access and pain clinic laws have reported contradictory evidence. 10 - 12 For example, naloxone access laws were estimated by 1 study to reduce opioid-related fatal overdose by 0.387 per 100 000 people in 3 or more years after adoption, 10 whereas another study reported that there were no significant changes in mean opioid-related mortality but a 14% increase in the Midwest after the implementation of naloxone access laws. 11

A likely explanation for the conflicting evidence on opioid policy outcomes is methodological limitations of existing work. First, discrepant findings may be attributable to differences in data coverage, such as variation in the states and time periods included in analyses. 13 , 14 This sample selection issue makes it difficult to compare and synthesize existing evidence. Second, there is disagreement about how to operationalize and model the timing of policy implementation. 15 Third, the most common modeling approach, the 2-way fixed-effects model in difference-in-differences analysis (ie, controlling for both state and period indicators) has an important limitation: likely violation of the parallel trends assumption. 16 , 17 Because many states enacted new policies after 2013, it is urgent to conduct an updated assessment of the impact of state opioid policy using more recent data.

Herein, we present the most comprehensive study to date on state policies that target the US opioid epidemic, focusing on the consequences of policies for both prescription opioid misuse and overdose mortality. Are state drug policies significantly associated with variations in opioid misuse, opioid use disorder, and drug overdose mortality? To answer this question, we use panel matching to implement a rigorous difference-in-differences approach in conjunction with extensive data coverage that includes observations through 2018 (2007–2018; across 50 states). We also assemble and refine the policy timing data across the 6 most widely studied policies; to our knowledge, these data have never before been investigated in tandem.

This analysis draws on medical and pharmacy claims data from the Optum Clinformatics Data Mart Database (2007-2018) and a publicly available mortality data set from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). The Optum database is a large deidentified database from a national private insurance provider 18 - 20 that includes medical and prescription claims for the full population of patients ever prescribed any controlled substance between 2007 and 2018 (approximately 23 million). eAppendix 1 and eTable 1 in the Supplement include a description of the Optum database and the population coverage by state. Excluded from the study were patients with cancer and those receiving palliative care because they are expected to be outliers with respect to (medically necessary) opioid consumption. We measured all indicators at the patient level and aggregated them to the level of state of residence. We obtained state-level overdose mortality data from the NCHS Multiple Cause of Death file from 1999 to 2018. In addition, we obtained data on several confounders (ie, the proportion of female individuals; those aged <40 years, 40-60 years, and >60 years; White, Black, Asian, and Hispanic individuals, and individuals of other races [American Indian, Pacific Islander, and multiple racial categories except for Hispanic]; those who were unemployed; those living below the poverty line; the state population; and state implementation of Medicaid expansion) from current population surveys. We aggregated individual-level data to quarterly state-level data using the provided survey weights. Herein we report results across quarterly units because we find that these units generate more precise estimates. This study was approved by the institutional review board at Indiana University, and the requirement for informed consent was waived because deidentified data were used. We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology ( STROBE ) reporting guideline.

We used an extensive set of prescription opioid outcomes. First, we measured the proportion of patients who received any opioid during a given period (ie, quarter). Second, using the subset of patients who received any opioid between 2007 and 2018, we computed 5 additional measures. The International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision ( ICD-9 ) and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision ( ICD-10 ) codes were used to identify opioid use disorder and overdose diagnosis (eTable 2 in the Supplement ) and measure the proportion of patients with the disorder or overdose diagnosis. We also calculated the proportion of patients who received opioid doses higher than the maximum daily morphine milligram equivalent (MME) of 90, which was generated by enumerating daily MME (Strength per Unit × [Number of Units/Days Supply] × MME Conversion Factor) 21 of all opioid prescriptions over time for each patient.

In addition, we measured the traditional doctor-shopping indicator (ie, the proportion of patients who visit ≥4 unique doctors and ≥4 unique pharmacies for opioids within 90 days) 22 and the proportion of patients with overlapping opioid prescriptions. We also examined opioid treatment, which was defined as the proportion of patients who were prescribed any medication-assisted treatment (MAT) drug that includes buprenorphine, buprenorphine/naloxone, buprenorphine hydrochloride and naltrexone. 23 We excluded methadone from the MAT drug list because it is often used as an opioid analgesic when prescribed by primary care physicians and other physicians for purposes other than substance use treatment, although results were similar when methadone was included in the list. Across all measures, we used the number of total enrollees, excluding those with cancer and those receiving palliative care in each state and year-quarter as denominators. eTable 3 in the Supplement details the basic characteristics of the analytic sample. eTable 4 in the Supplement includes summary statistics for the 6 indicators across patients with the Medicare low-income subsidy, Medicare beneficiaries, and patients without Medicare.

We used ICD-10 codes to identify overdose mortality and to differentiate the cause of death. Deaths with drug overdose as the underlying cause were first identified using codes X40-X44 (unintentional), X60-X64 (suicide), X85 (homicide), and Y10-Y14 (undetermined intent). Of those codes, drug-related deaths were further identified based on codes T40.0-T40.6, including those for heroin (T40.1), natural and semisynthetic opioids (T40.2), methadone (T40.3), synthetic opioids excluding methadone (T40.4), cocaine (T40.5), and other unspecified drugs (T40.6). We included opioid and nonopioid overdose-inducing drugs because of the high incidence of polysubstance use among those with opioid use disorder. 24 , 25 We repeated our query through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s CDC Wonder online database across different causes of death ( ICD-10 codes T40.1-T40.6) between 1999 and 2018 except for 1 month, and then subtracted the total number of deaths excluding each month from the total number of deaths across 2007 to 2018 (a total of 144 queries) to identify the number of deaths each month. This method can was used to recover the monthly death counts (eTable 5 in the Supplement includes the annual counts across different causes of deaths).

We compiled a data set on 6 opioid-related policies with 2 broad objectives: to control the supply of prescription opioids or reduce harms and barriers to medical assistance for overdose. eTables 6 and 7 in the Supplement show the exact year and month of all policy implementation dates by state. The opioid-related policies include (1) PDMP access laws that provide access to the PDMP, an electronic database that tracks controlled substance prescriptions in a state; (2) mandatory PDMPs that require prescribers under certain circumstances to access the PDMP database prior to prescribing opioids; (3) prescription limit laws that impose limitations on the number of days that medical professionals dispense opioids for acute pain; (4) pain clinic laws that regulate the operation of pain clinics; (5) Good Samaritan laws that provide immunity or other legal protection for those who call for help during overdose events; and (6) naloxone access laws that provide civil or criminal immunity to licensed health care clinicians or lay responders for administration of opioid antagonists, such as naloxone hydrochloride, to reverse overdose. eAppendix 2 in the Supplement describes the information collection process for these state policies. Based on the dates of these policies, we defined treatment indicators , which were assigned a value of 1 if the law was active in a given quarter, otherwise a value of 0 was assigned. In addition, we created a separate indicator for state implementation of Medicaid expansion that we obtained from the Kaiser Family Foundation to control for its potential impact on the statistical inferences.

To ascertain whether state policy altered the prevalence of opioid abuse and misuse indicators, we used a difference-in-differences approach. A state was considered to be a treated case if the policy had been changed at a specified time , otherwise it was considered to be an untreated case. The goal was to compare the outcomes of interest for a state under the new policy regime at a specific time with the outcome under the old policy regime if the policy was not enacted at the same time. The key challenge was to find a suitable control case for the treated case. The difference-in-differences approach imputed the change of outcomes in the control case as a comparison case for the change of outcomes in the treatment case under the parallel trends assumption (ie, potential outcomes have a parallel time trend for the treatment and control groups). Namely, the difference of outcomes between the treated case and the control case before the policy change would stay the same after the change in the absence of treatment.

To mitigate potential violations of the parallel trends assumption, we used panel matching to construct a matched data set to make trends of pretreatment outcomes parallel across control and treatment cases in addition to other observed confounders (ie, the proportion of female individuals; individuals aged <40 years, 40-60 years, and >60 years; individuals of White, Black, Asian, and Hispanic race and those of other races [American Indian, Pacific Islander, and multiple racial categories except for Hispanic], unemployed individuals, those living below the poverty line, as well as the state population and state implementation of Medicaid expansion) through covariate-balancing propensity scores (CBPS). eAppendix 3 in the Supplement describes the application of panel matching.

We used the PanelMatch package in R, version 4.0.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing), 26 to estimate the effect sizes of the temporal associations between policies and leading outcomes of interest for each quarter for 3 years (ie, up to 12 quarters). We used the metafor package in R 27 for the random-effects meta-analysis model to summarize temporal associations for each policy and outcome pair (eAppendix 3 in the Supplement ). We present uncertainty associated with effect sizes using 95% CIs to shift focus away from the null hypothesis testing toward showing the full range of effect sizes, we define an association as negative if the mean effect across all quarters is negative and a positive association if the mean effect is positive. In addition, associations are defined as significant if their 95% CIs do not overlap with zero. The data analysis was conducted July 12, 2020. All codes and data to replicate analyses are available at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/bk .

This cross-sectional study includes data on drug overdose mortality from the Optum Clinformatics Data Mart database and insurance claims data from the NCHS for 23 million commercially insured patients in 50 states between 2007 and 2018. Of these patients, 12 582 378 (55.1%) were women, and the mean (SD) age was 45.9 (19.9) years. Figure 1 depicts the cumulative count of opioid-related policies implemented by 50 states from 2007 to 2018. The monthly count of opioid policies started to increase substantially after 2012 to 2013. The implementation of Good Samaritan and naloxone access laws have been the largest contributor to the overall increase in policy adoption since 2013. In the first quarter of 2018, states adopted a mean of 4.1 policies, and 22 states adopted all but 1 policy. Access to PDMPs was implemented first by most states followed by the implementation of Good Samaritan and naloxone access laws, whereas mandatory PDMP and prescription limit laws were implemented in later periods. In 2014, Medicaid expansion laws were enacted in approximately half of the states, which may have biased the impact of other state drug policies. We accounted for this issue by controlling for an indicator of Medicaid expansion in the statistical models.

The rate of overdose deaths as well as the diagnosis of overdose and opioid use disorder increased as states implemented more policies (eFigure 4 in the Supplement ), although indicators of opioid misuse and “doctor shopping” declined. For example, states without any of 6 policies exhibited a lower proportion of patients with overdose and opioid use disorder (0.14%) and a higher proportion of patients with a daily MME of 90 or higher (2.54%) vs states with all 6 policies (0.95% and 2.01%, respectively). Associations between mandatory PDMP and naloxone access law on 3 indicators from the commercially insured population are presented in Figure 2 . eFigure 5 in the Supplement shows the consequences of implementation of all 6 policies for all 6 indicators. Figure 2 summarizes the temporal associations for each policy and outcome pair; the effect sizes with 95% CIs are presented with shaded panel backgrounds if the 95% CIs did not overlap with 0 effects (in eTable 8 in the Supplement ).

First, supply-controlling policies were associated with reduction in 4 known prescription opioid misuse indicators: the proportion of patients who take opioids, have overlapping claims, receive higher opioid doses (daily MME ≥90), and visit multiple providers and pharmacies. For example, a mandatory PDMP was associated with a reduction of 0.729% (95% CI, −1.011% to −0.447%) in the proportion of patients taking opioids, those with overlapping opioid claims (−0.027%; 95% CI, −0.038% to −0.017%), those with a daily MME of 90 or higher (−0.095%; 95% CI, −0.150% to −0.041%), and in those who engaged in drug seeking behavior (−0.002%; 95% CI, −0.003% to −0.001%. In contrast, PDMP access was associated with a 0.17% (95% CI, 0.07%-0.26%) increase in the proportion of patients taking opioids and a 0.04% (95% CI, 0.007%-0.075%) increase in patients with a daily MME of 90 or higher. Second, the harm-reduction policies (ie, Good Samaritan laws and naloxone access laws) were associated with modest increases in the proportion of patients with overdose (0.014%; 95% CI, 0.002%-0.027%) and opioid use disorder (0.05%; 95% CI, 0.03%-0.07%). Third, the proportion of patients receiving MAT drugs increased following the implementation of supply-controlling policies, including mandatory PDMP (0.015%; 95% CI, 0.002%-0.028%), pain clinic laws (0.013%; 95% CI, 0.005%-0.021%), and prescription limit laws (0.034%; 95% CI, 0.020%-0.049%). Methadone as MAT produces similar results, including for pain clinic laws (0.024%; 95% CI, 0.009% to 0.039%) and prescription limit laws (0.014%, 95% CI, 0.003% to 0.025%). In general, the policy effect sizes became larger when estimating later outcomes, suggesting that the policy implementation does not produce immediate changes, but rather takes time to be effective (ie, a policy response lag).

Figure 3 shows the rate of drug overdose mortality after enactment of mandatory PDMPs and naloxone access laws. eFigure 6 in the Supplement shows the rate of drug overdose mortality after enactment of all 6 policies, and eTable 9 in the Supplement shows the temporal associations for overall drug overdose deaths and deaths from specific opioids (eg, natural, synthetic, heroin). First, all overdose deaths increased following the implementation of naloxone access laws (1344.3 [95% CI, 627.1-2061.6] per 300 million people), especially deaths attributable to heroin (280.3 per 300 million people), synthetic opioids (1338.2 [95% CI, 662.5-2014.0] per 300 million people), and cocaine (557.6 [95% CI, 328.3-787.0] per 300 million people). Good Samaritan laws were also associated with increases in overall overdose deaths (403.7 [95% CI, 172.7-634.8] per 300 million people). Second, mandatory PDMPs were associated with a reduction of overdose deaths from natural opioids (−518.5 [95% CI, −728.5 to −308.5] per 300 million people) and methadone (−122.7 [95% CI, −207.5 to −37.8] per 300 million people), although the effect size was smaller than those of harm-reduction policies. Prescription drug monitoring program access policies showed similar results, although these policies were also associated with increases in overdose deaths from synthetic opioids (380.3 [95% CI, 149.6-610.8] per 300 million people) and cocaine (103.7 [95% CI, 28.0-179.5] per 300 million people). The implementation of pain clinic laws was associated with an increase in the number of overdose deaths from heroin (336.3 [95% CI, 79.5-593.0] per 300 million people) and cocaine (97.3 [95% CI, 23.9-170.8] per 300 million people). As an exception, having a prescription limit law was associated with a decrease in overdose deaths from synthetic opioids (−723.9 [95% CI, −1419.7 to −28.1] per 300 million people). In line with the results from analysis of 6 policies using medical claims data, we found a substantial policy response lag. All effect sizes from 0 to 12 quarters across 12 outcomes and 6 policies are presented in eTable 10 in the Supplement .

Recent trends in the US opioid epidemic present a paradox: opioid overdose mortality has continued to increase despite declines in opioid prescriptions since 2012. 28 , 29 The opioid paradox may arise from the success—not failure—of state interventions to control opioid prescriptions. This finding is supported by a comprehensive assessment of multiple opioid policies on a range of outcomes, including opioid misuse and overdose mortality with extensive data coverage. We found that supply-controlling policies were associated with a reduction in the amount of prescription opioid misuse and the number of overdose deaths attributable to natural opioids as well as an increase in the number of patients receiving MAT drugs. In tandem, the significant increase of overdose deaths from synthetic opioids, heroin, and cocaine after the enactment of PDMP access, pain clinic laws, and naloxone access laws suggests that current drug policies may have the unintended consequence of motivating opioid users to switch to illicit drugs. An important implication of our findings is that there is no easy policy solution to reverse the epidemic of opioid dependence and mortality in the US. Hence, to resolve the opioid paradox, it is imperative to design policies to address the fundamental causes of overdose deaths (eg, lack of economic opportunity, persistent physical, and mental pain) and enhance treatment for drug dependence and overdose rather than focusing on opioid analgesic agents as the cause of harm. 2 , 30

Prescription drug monitoring programs are the most widely studied policy responses to the opioid epidemic. Previous research on their impact indicates that providing access to PDMPs is not associated with significant improvement, but PDMPs have reduced prescription opioid misuse when accessing the databases was required for physicians. 8 , 22 , 31 The present study found that mandatory PDMPs also reduced opioid misuse in a commercially insured population. In addition, we found that prescription limit laws and pain clinic laws were associated with a reduction in opioid abuse and an increase in the proportion of patients receiving MAT drugs. A study found that these laws as designed significantly reduce the length of initial prescription, although they also increase the likelihood of new (ie, first time) opioid use and the strength of initial prescription. 32 In addition, pain clinic laws have been associated with modest decreases in opioid prescribing in Florida and Texas. 33 , 34 The results of the present study are broadly consistent with those of other studies.

This extensive analysis may settle some of the contradictory findings in the literature and contributes to the previous research on opioid policy outcomes. Previous research on naloxone access and Good Samaritan laws has yielded inconsistent results. Namely, the enactment of naloxone access laws has been associated with substantial reductions in a fatal overdose but increased nonfatal overdoses. 10 , 12 These results, however, have been contradicted by other studies that suggested that expansion of naloxone access laws leads to more opioid-related emergency department visits and thefts without any substantial reductions in opioid mortality. 11 , 35 Likewise, previous research has suggested that Good Samaritan laws are not associated with heroin-related mortality, but substantially reduce mortality from other opioids. 12 The situation is similar to studies examining the association between PDMPs and overdose mortality. 6 , 7 , 13 , 14 Differences between our results and those of previous studies may be explained by our rigorous and extensive analytic approach, which uses panel matching for difference-in-differences analysis to mitigate the violation of the parallel trends assumption and the use of more recent data while simultaneously examining temporal associations. Given that most state policies were enacted after 2013, the present study used data through 2018 to provide the most up-to-date evidence on the opioid policy landscape.

We believe that our findings on the role of harm reduction policies in accelerating drug overdose deaths, especially those attributable to synthetic opioids and heroin, have important implications. Good Samaritan laws are designed to remove the threat of liability for people who call for emergency assistance in the event of a drug overdose. It is theoretically possible that provision of immunity may lead to greater reporting of overdose events in the absence of actual increases, although it is less likely to explain the increase of overdose deaths after the enactment of a Good Samaritan law. Naloxone laws provide civil immunity to licensed health care professionals or lay responders for opioid antagonist administration. Although expanded access to naloxone can reverse an opioid overdose and save lives, we found that naloxone access laws were associated with a substantial increase rather than a decrease in overdose deaths, especially deaths from illicit drugs. It is possible that the prospect of getting access to overdose-reversing treatment may instead induce moral hazards by encouraging people to use opioids and other drugs in riskier ways than they would have without the safety net of naloxone. 11 Although naloxone access laws were estimated to increase naloxone dispensing, 36 a recent study found that only 2135 of 138 108 high-risk patients (1.5%) in the US were prescribed naloxone in 2016. 37 This finding suggests that policies designed to dramatically improve treatment for overdose are needed.

Several important limitations of this study are worth noting. First, a difference-in-differences approach through panel matching cannot account for spillover effects between states and between policies. 26 Although we believe that considering multiple types of drug policies simultaneously is important, teasing out the association between a single policy and outcome from those of other policies is difficult because of correlated policy responses. Likewise, because prior research suggests that states’ adoption of Medicaid expansion has led to an increase in opioid overdose-related mortality 38 but a decrease in opioid-related hospital use, 39 we accounted for this factor by adjusting for Medicaid expansion in the modeling framework. However, identifying policy consequences on outcomes while controlling for the adoption of Medicaid expansion may produce underestimates or overestimates given the policy response lag and overlaps among different policy responses. Future research may consider, for example, sequence analysis or other clustering methods combined with the difference-in-differences approach to examine the impact of correlated policy responses.

Second, because we draw on data from a commercially insured population, these findings may not extend to other populations or to those individuals with insurance who pay cash for opioid prescriptions. Opioid misuse and overdose rates are higher among Medicare beneficiaries in our patient population with a low-income subsidy (eTable 4 in the Supplement ), which suggests that this analysis may be missing a substantial proportion of the population at risk for opioid problems. Although the results on opioid misuse are consistent with those of an earlier report on mandatory PDMPs up to 2013 using a Medicare part D sample, 8 future research is needed to ascertain whether the findings of the present analysis can be generalized to other patient populations. Third, there are potential limitations of using ICD-10 codes to identify fatal overdose owing to inaccuracy and incompleteness of death classification. 40 In addition, the transition of overdose coding from ICD-9 to ICD-10 may have contributed to the increase in overdose cases after October of 2015. 41 Because systematic misreporting on fatal and nonfatal overdoses may induce bias in our estimates, it is crucial to examine and account for factors that affect the identification of overdose deaths in future work.

The cause of opioid dependence is multifactorial, rooted in complex interactions between social, psychological, biological, and genetic factors. 42 Heightened demand for diverted and illicit drugs might arise from limiting the supply of prescription opioids under certain conditions. 43 These unintended consequences may occur if the fundamental causes of demand for opioids are not addressed and if the ability to reverse overdose is expanded without increasing treatment of opioid overdose. We believe that policy goals should be shifted from easy solutions (eg, dose reduction) to more difficult fundamental ones, focusing on improving social conditions that create demand for opioids and other illicit drugs. 2

Accepted for Publication: December 19, 2020.

Published: February 12, 2021. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36687

Correction: This article was corrected on March 10, 2021, to fix errors in the data reported in eTable 4 in the Supplement.

Open Access: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY License . © 2021 Lee B et al. JAMA Network Open .

Corresponding Author: Brea L. Perry, PhD, Department of Sociology, Indiana University-Bloomington, 1020 E Kirkwood Ave, 767 Ballantine Hall, Bloomington, IN 47405 ( [email protected] ).

Author Contributions : Drs Lee and Perry had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Concept and design: Lee, Perry.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Lee.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Lee.

Obtained funding: Perry.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Lee, Zhao, Yang, Ahn.

Supervision: Lee, Ahn.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Funding/Support: This research was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA039928; Dr Perry), and an Indiana University Addictions Grand Challenge Grant (Dr Perry).

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Additional Contributions: We would like to thank the information technology team at the Indiana University Network Science Institute for their technical support. The team received no compensation, other than the usual salary, for contributions to this work.

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

People & Community

Research & Impact

Career Services

Working Papers

0 results found.

Publications about Drug Policy

Do citizens know whether their state has decriminalized marijuana a test of the perceptual assumpti.

, Rosalie Liccardo Pacula, Jamie F. Chriqui, Katherine M. Harris , Peter H. Reuter

Working Paper: GSPP08-011 (April 2008)

Deterrence theory proposes that legal compliance is influenced by the anticipated risk of legal sanctions. This implies that changes in law will produce corresponding changes in behavior, but the marijuana decriminalization literature finds only fragmentary support for this prediction. But few studies have directly assessed the accuracy of citizens' perceptions of legal sanctions. The heterogeneity in state statutory penalties for marijuana possession across the United States provides an opportunity to examine this issue. Using national survey data, we find that the percentages who believe they could be jailed for marijuana possession are quite similar in both states that have removed those penalties and those that have not. Our results help to clarify why statistical studies have found inconsistent support for an effect of decriminalization on marijuana possession.

Drug Use and Drug Policy in a Prohibition Regime

, Karin D. Martin

Working Paper: GSPP08-008 (April 2008)

Prohibition makes some drug use and drug selling a crime by statute, but licit drugs like alcohol are also associated with criminality in myriad ways. Within a prohibition regime, it is difficult but important to distinguish a drug's "intrinsic" psychopharmacological harms from the harms created or exacerbated by prohibition and its enforcement. Rather than debating the merits of legalization (see MacCoun & Reuter, 2001), we evaluate current epidemiological patterns and mainstream policy instruments within the US prohibition regime, but we go beyond the standard criterion of prevalence reduction by considering harm reduction and quantity reduction as well. We close by speculating about some emerging challenges, including the "thizzle" scene and the future of performance enhancing drugs.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- 15 April 2024

- Correction 22 April 2024

Revealed: the ten research papers that policy documents cite most

- Dalmeet Singh Chawla 0

Dalmeet Singh Chawla is a freelance science journalist based in London.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Policymakers often work behind closed doors — but the documents they produce offer clues about the research that influences them. Credit: Stefan Rousseau/Getty

When David Autor co-wrote a paper on how computerization affects job skill demands more than 20 years ago, a journal took 18 months to consider it — only to reject it after review. He went on to submit it to The Quarterly Journal of Economics , which eventually published the work 1 in November 2003.

Autor’s paper is now the third most cited in policy documents worldwide, according to an analysis of data provided exclusively to Nature . It has accumulated around 1,100 citations in policy documents, show figures from the London-based firm Overton (see ‘The most-cited papers in policy’), which maintains a database of more than 12 million policy documents, think-tank papers, white papers and guidelines.

“I thought it was destined to be quite an obscure paper,” recalls Autor, a public-policy scholar and economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. “I’m excited that a lot of people are citing it.”

The most-cited papers in policy

Economics papers dominate the top ten papers that policy documents reference most.

Data from Overton as of 15 April 2024

The top ten most cited papers in policy documents are dominated by economics research; the number one most referenced study has around 1,300 citations. When economics studies are excluded, a 1997 Nature paper 2 about Earth’s ecosystem services and natural capital is second on the list, with more than 900 policy citations. The paper has also garnered more than 32,000 references from other studies, according to Google Scholar. Other highly cited non-economics studies include works on planetary boundaries, sustainable foods and the future of employment (see ‘Most-cited papers — excluding economics research’).

These lists provide insight into the types of research that politicians pay attention to, but policy citations don’t necessarily imply impact or influence, and Overton’s database has a bias towards documents published in English.

Interdisciplinary impact

Overton usually charges a licence fee to access its citation data. But last year, the firm worked with the publisher Sage to release a free web-based tool , based in Thousand Oaks, California, that allows any researcher to find out how many times policy documents have cited their papers or mention their names. Overton and Sage said they created the tool, called Sage Policy Profiles, to help researchers to demonstrate the impact or influence their work might be having on policy. This can be useful for researchers during promotion or tenure interviews and in grant applications.

Autor thinks his study stands out because his paper was different from what other economists were writing at the time. It suggested that ‘middle-skill’ work, typically done in offices or factories by people who haven’t attended university, was going to be largely automated, leaving workers with either highly skilled jobs or manual work. “It has stood the test of time,” he says, “and it got people to focus on what I think is the right problem.” That topic is just as relevant today, Autor says, especially with the rise of artificial intelligence.

Most-cited papers — excluding economics research

When economics studies are excluded, the research papers that policy documents most commonly reference cover topics including climate change and nutrition.

Walter Willett, an epidemiologist and food scientist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts, thinks that interdisciplinary teams are most likely to gain a lot of policy citations. He co-authored a paper on the list of most cited non-economics studies: a 2019 work 3 that was part of a Lancet commission to investigate how to feed the global population a healthy and environmentally sustainable diet by 2050 and has accumulated more than 600 policy citations.

“I think it had an impact because it was clearly a multidisciplinary effort,” says Willett. The work was co-authored by 37 scientists from 17 countries. The team included researchers from disciplines including food science, health metrics, climate change, ecology and evolution and bioethics. “None of us could have done this on our own. It really did require working with people outside our fields.”

Sverker Sörlin, an environmental historian at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, agrees that papers with a diverse set of authors often attract more policy citations. “It’s the combined effect that is often the key to getting more influence,” he says.

Has your research influenced policy? Use this free tool to check

Sörlin co-authored two papers in the list of top ten non-economics papers. One of those is a 2015 Science paper 4 on planetary boundaries — a concept defining the environmental limits in which humanity can develop and thrive — which has attracted more than 750 policy citations. Sörlin thinks one reason it has been popular is that it’s a sequel to a 2009 Nature paper 5 he co-authored on the same topic, which has been cited by policy documents 575 times.

Although policy citations don’t necessarily imply influence, Willett has seen evidence that his paper is prompting changes in policy. He points to Denmark as an example, noting that the nation is reformatting its dietary guidelines in line with the study’s recommendations. “I certainly can’t say that this document is the only thing that’s changing their guidelines,” he says. But “this gave it the support and credibility that allowed them to go forward”.

Broad brush

Peter Gluckman, who was the chief science adviser to the prime minister of New Zealand between 2009 and 2018, is not surprised by the lists. He expects policymakers to refer to broad-brush papers rather than those reporting on incremental advances in a field.

Gluckman, a paediatrician and biomedical scientist at the University of Auckland in New Zealand, notes that it’s important to consider the context in which papers are being cited, because studies reporting controversial findings sometimes attract many citations. He also warns that the list is probably not comprehensive: many policy papers are not easily accessible to tools such as Overton, which uses text mining to compile data, and so will not be included in the database.

The top 100 papers

“The thing that worries me most is the age of the papers that are involved,” Gluckman says. “Does that tell us something about just the way the analysis is done or that relatively few papers get heavily used in policymaking?”

Gluckman says it’s strange that some recent work on climate change, food security, social cohesion and similar areas hasn’t made it to the non-economics list. “Maybe it’s just because they’re not being referred to,” he says, or perhaps that work is cited, in turn, in the broad-scope papers that are most heavily referenced in policy documents.

As for Sage Policy Profiles, Gluckman says it’s always useful to get an idea of which studies are attracting attention from policymakers, but he notes that studies often take years to influence policy. “Yet the average academic is trying to make a claim here and now that their current work is having an impact,” he adds. “So there’s a disconnect there.”

Willett thinks policy citations are probably more important than scholarly citations in other papers. “In the end, we don’t want this to just sit on an academic shelf.”

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-00660-1

Updates & Corrections

Correction 22 April 2024 : The original version of this story credited Sage, rather than Overton, as the source of the policy papers’ citation data. Sage’s location has also been updated.

Autor, D. H., Levy, F. & Murnane, R. J. Q. J. Econ. 118 , 1279–1333 (2003).

Article Google Scholar

Costanza, R. et al. Nature 387 , 253–260 (1997).

Willett, W. et al. Lancet 393 , 447–492 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Steffen, W. et al. Science 347 , 1259855 (2015).

Rockström, J. et al. Nature 461 , 472–475 (2009).

Download references

Reprints and permissions

Related Articles

Will AI accelerate or delay the race to net-zero emissions?

Comment 22 APR 24

We must protect the global plastics treaty from corporate interference

World View 17 APR 24

UN plastics treaty: don’t let lobbyists drown out researchers

Editorial 17 APR 24

CERN’s impact goes way beyond tiny particles

Spotlight 17 APR 24

The economic commitment of climate change

Article 17 APR 24

Last-mile delivery increases vaccine uptake in Sierra Leone

Article 13 MAR 24

Postdoctoral Associate- Artificial Intelligence

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Postdoctoral Research Fellow

Looking for postdoctoral fellowship candidates to advance genomic research in the study of lung diseases at Brigham and Women's Hospital and HMS.

Boston, Massachusetts

Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH)

Position Opening for Principal Investigator GIBH

We aim to foster cutting-edge scientific and technological advancements in the field of molecular tissue biology at the single-cell level.

Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

Guangzhou Institutes of Biomedicine and Health(GIBH), Chinese Academy of Sciences

PostDoc grant- 3D histopathology image analysis

Join a global pharmaceutical company as a Postdoctoral researcher and advance 3D histopathology image analysis! Apply with your proposals today.

Biberach an der Riß, Baden-Württemberg (DE)

Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH

Postdoctoral Position

We are seeking highly motivated and skilled candidates for postdoctoral fellow positions

Boston, Massachusetts (US)

Boston Children's Hospital (BCH)

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

This website uses cookies to improve your user experience. By continuing to use the site, you are accepting our use of cookies. Read the ACS privacy policy.

- ACS Publications

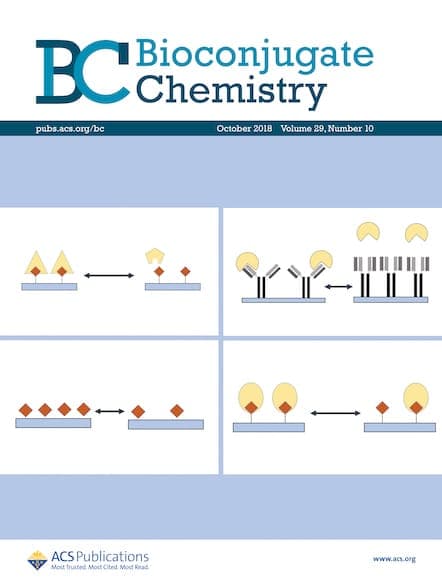

Call for Papers: Brain Targeted Drug Delivery

- Apr 19, 2024

This Special Issue will focus on the latest research in brain targeted drug delivery. Submit your manuscript by June 30, 2024.

The prevalence of central nervous diseases poses significant challenges to society, particularly with the global aging population. While various potential chemical agents, antibodies, and genes have been developed for the treatment of these diseases, the effectiveness of these treatments is greatly hindered by the presence of the blood-brain barrier.

We are pleased to announce that the American Chemical Society journal Bioconjugate Chemistry will publish a Special Issue titled “Brain Targeted Drug Delivery.” With this issue we aim to bring together researchers from different disciplines to share their knowledge and expertise in brain targeted drug delivery.

We welcome topics including, but not limited to:

- Novel approaches to overcome the blood-brain barrier

- Intranasal delivery methods for efficient drug transport to the brain

- Innovative drug delivery strategies for a variety of central nervous system diseases

- Emerging combinations of therapies for the treatment of glioma and Alzheimer’s disease

Guest Editors

Dr. Huile Gao Sichuan University, China

Dr. Zhiqing Pang Fudan University, China

Dr. Yang Liu Sun Yat-Sen University, China

Dr. Jia Li Macquarie University, Australia

How to Submit

- Log in to the ACS Paragon Plus submission site.

- Choose Bioconjugate Chemistry as your journal.

- Select your manuscript type.

- Under “Special Issue Selection” choose “ Brain Targeted Drug Delivery .”

Please see Bioconjugate Chemistry ’s Author Guidelines for more information on submission requirements. The deadline for submissions is June 30, 2024 .

Open Access

There are diverse open access options for publications in American Chemical Society journals. Please visit our Open Science Resource Center for more information.

Stay Connected

Want the latest stories delivered to your inbox each month, bioconjugate chemistry.

More than 1 in 4 deaths among young people in Canada were opioid-related in 2021, study finds

Nationally, annual number of opioid overdose deaths surged from 3,007 to 6,222 over three years.

Social Sharing

Opioid-related deaths doubled in Canada between 2019 and the end of 2021, with Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta experiencing a dramatic jump, mostly among men in their 20s and 30s, says a new study that calls for targeted harm-reduction policies.

Researchers from the University of Toronto analyzed accidental opioid-related deaths between Jan. 1, 2019 and Dec. 31, 2021 in those provinces as well as British Columbia, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, and the Northwest Territories.

Manitoba saw the sharpest rise in overdose deaths for those aged 30 to 39 — reaching 500 deaths per million population, more than five times the 89 deaths per million population recorded at the beginning of the study period.

In Saskatchewan, the death toll for that age group nearly tripled to 424 per million, up from 146 per million, while Alberta's rate spiked more than 2.5 times to 729 fatalities per million, up from 272 per million. Ontario's death rate reached 384, up from 210 per million.

B.C., which has been the epicentre of the overdose crisis, recorded 229 deaths per million for that age group in 2019, climbing to 394 in 2020. All data for 2021 from that province's coroners service was not yet available when researchers completed their work based on information collected by the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Push to better understand the long-term harms of opioid use

Nationally, the annual number of opioid overdose deaths surged from 3,007 to 6,222 over the three-year study period, which researchers note coincided with pandemic public health measures that reduced access to harm reduction programs and imposed border restrictions that may have increased the toxicity of the drug supply.

"In addition, for many, the pandemic exacerbated feelings of anxiety, uncertainty and loneliness, contributing to increased substance use globally," they said.

The study was published Monday in the Canadian Medical Association Journal .

Senior author Tara Gomes said one in four deaths involved people in their 20s and 30s. More than 70 per cent of the overall deaths were among men.

A spokesperson with the coroners service in B.C. said 78 per cent of people that fatally overdosed in that province between 2019 and the end of 2021 were men.

Devastating impacts

The sharp surge in fatal overdoses — especially among young adults on the Prairies — suggests provinces must act quickly, said Gomes, an epidemiologist who called for more harm-reduction services including supervised consumption sites.

"Being slow and not being as nimble as we would like to be in our responses can have really devastating impacts," said Gomes, also lead principal investigator of the Ontario Drug Policy Research Network.

Response to opioid crisis must be multipronged, says drug policy expert

Bernadette Smith, Manitoba's minister of housing, addiction, homelessness and mental health, said the province plans to open its first supervised consumption site in Winnipeg next year and will also offer drug-testing machines so people can check if their illicit substances are toxic.

"We came out of a previous government that didn't take a harm-reduction approach, unfortunately," said the New Democrat, whose party defeated the Progressive Conservatives last fall.

'They wouldn't have enough beds'

"We're working with front-line organizations because they have not been listened to or worked with for the last seven years in our province, which has been a real problem," Smith said.

Manitoba plans to train family doctors to treat addiction with medications including Suboxone and methadone, said Smith, noting the physicians typically refer patients to detox for care.

"We're creating a model so that folks aren't having to go to a bunch of different places to get different services," said Smith.

She declined to say whether Manitobans will have access to a prescribed safer supply of drugs.

Tanya Hornbuckle of Edmonton said her son Joel Wolstenholme was 30 when he died in 2022. He became addicted to illicit substances at about age 14, starting with cannabis before shifting to methamphetamine, cocaine and other drugs that were increasingly laced with fentanyl.

He also battled a mental illness, but getting help for both that issue and addiction in a single service was challenging, Hornbuckle said.

Wolstenholme tried multiple times to detox, but there were never enough beds at a clinic where people had to line up at 8 a.m., she said.

"It would happen over and over and then he would call me. I went and stood in line or I drove him there and waited with him in the lineup. They wouldn't have enough beds."

Her son's anxieties and addiction worsened when pandemic restrictions prevented her from entering an emergency room with him because he did not trust staff, Hornbuckle said.

On Feb. 6, 2022, Hornbuckle went to her son's home so they could cook together. She found him dead.

- 8 years and 14,000 deaths later, B.C.'s drug emergency rages on

- Why staff at an Ontario cottage country restaurant took naloxone training

The Alberta government's strategy of focusing more on recovery and abstinence-based treatment than harm reduction, mental health and housing is the wrong approach, said Hornbuckle, noting that for a time her son slept in parks and abandoned houses after losing his vehicle and apartment to addiction.

Rebecca Haines-Saah, an associate professor of community health services at the University of Calgary, called the deaths of young people from overdose a tragedy, and said many more suffer from brain injury due to toxic substances.

Halifax doctor calls for safer opioid access

"Obviously, we have the incorrect response. We do not have the approach and services available to keep people alive," said Haines-Saah, who also called for more harm-reduction services.

"We don't have a full-scale public health response that is required. We don't have any plans to fund anything that relates to what we would call harm reduction."

Much of the current approach to addiction excludes a large number of recreational drug users, said Gomes. She said between a third and half of the deaths in Ontario involved people without an opioid use disorder diagnosis.

"So, focusing on [residential treatment] alone is something that really concerns me because we really need to make sure that we have different options for different people."

Canadian Press health coverage receives support through a partnership with the Canadian Medical Association. CP is solely responsible for this content.

Related Stories

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Partisan divides over K-12 education in 8 charts

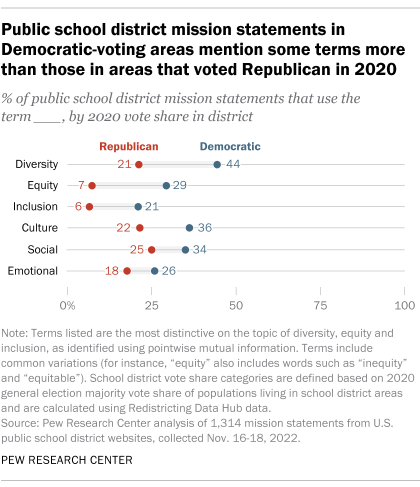

K-12 education is shaping up to be a key issue in the 2024 election cycle. Several prominent Republican leaders, including GOP presidential candidates, have sought to limit discussion of gender identity and race in schools , while the Biden administration has called for expanded protections for transgender students . The coronavirus pandemic also brought out partisan divides on many issues related to K-12 schools .

Today, the public is sharply divided along partisan lines on topics ranging from what should be taught in schools to how much influence parents should have over the curriculum. Here are eight charts that highlight partisan differences over K-12 education, based on recent surveys by Pew Research Center and external data.

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to provide a snapshot of partisan divides in K-12 education in the run-up to the 2024 election. The analysis is based on data from various Center surveys and analyses conducted from 2021 to 2023, as well as survey data from Education Next, a research journal about education policy. Links to the methodology and questions for each survey or analysis can be found in the text of this analysis.

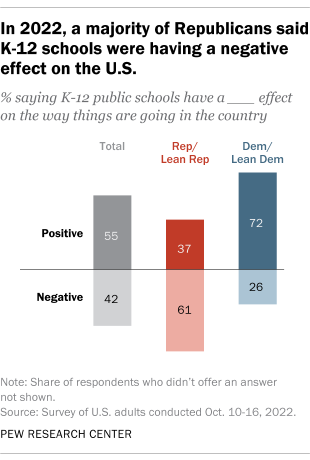

Most Democrats say K-12 schools are having a positive effect on the country , but a majority of Republicans say schools are having a negative effect, according to a Pew Research Center survey from October 2022. About seven-in-ten Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (72%) said K-12 public schools were having a positive effect on the way things were going in the United States. About six-in-ten Republicans and GOP leaners (61%) said K-12 schools were having a negative effect.

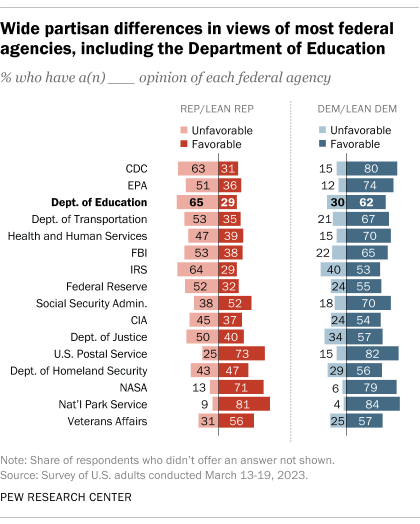

About six-in-ten Democrats (62%) have a favorable opinion of the U.S. Department of Education , while a similar share of Republicans (65%) see it negatively, according to a March 2023 survey by the Center. Democrats and Republicans were more divided over the Department of Education than most of the other 15 federal departments and agencies the Center asked about.

In May 2023, after the survey was conducted, Republican lawmakers scrutinized the Department of Education’s priorities during a House Committee on Education and the Workforce hearing. The lawmakers pressed U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona on topics including transgender students’ participation in sports and how race-related concepts are taught in schools, while Democratic lawmakers focused on school shootings.

Partisan opinions of K-12 principals have become more divided. In a December 2021 Center survey, about three-quarters of Democrats (76%) expressed a great deal or fair amount of confidence in K-12 principals to act in the best interests of the public. A much smaller share of Republicans (52%) said the same. And nearly half of Republicans (47%) had not too much or no confidence at all in principals, compared with about a quarter of Democrats (24%).

This divide grew between April 2020 and December 2021. While confidence in K-12 principals declined significantly among people in both parties during that span, it fell by 27 percentage points among Republicans, compared with an 11-point decline among Democrats.

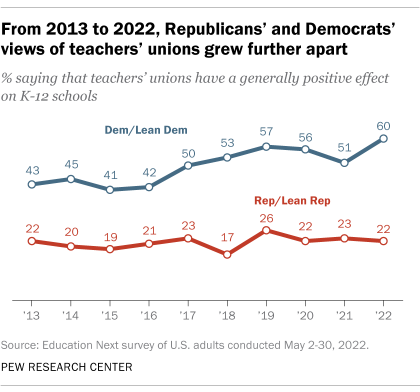

Democrats are much more likely than Republicans to say teachers’ unions are having a positive effect on schools. In a May 2022 survey by Education Next , 60% of Democrats said this, compared with 22% of Republicans. Meanwhile, 53% of Republicans and 17% of Democrats said that teachers’ unions were having a negative effect on schools. (In this survey, too, Democrats and Republicans include independents who lean toward each party.)

The 38-point difference between Democrats and Republicans on this question was the widest since Education Next first asked it in 2013. However, the gap has exceeded 30 points in four of the last five years for which data is available.

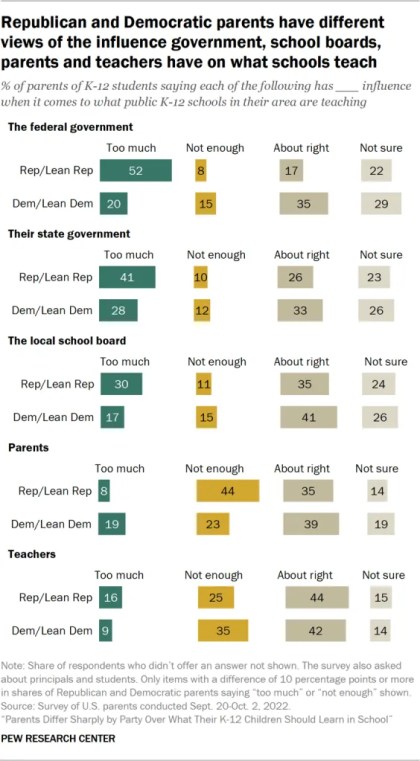

Republican and Democratic parents differ over how much influence they think governments, school boards and others should have on what K-12 schools teach. About half of Republican parents of K-12 students (52%) said in a fall 2022 Center survey that the federal government has too much influence on what their local public schools are teaching, compared with two-in-ten Democratic parents. Republican K-12 parents were also significantly more likely than their Democratic counterparts to say their state government (41% vs. 28%) and their local school board (30% vs. 17%) have too much influence.

On the other hand, more than four-in-ten Republican parents (44%) said parents themselves don’t have enough influence on what their local K-12 schools teach, compared with roughly a quarter of Democratic parents (23%). A larger share of Democratic parents – about a third (35%) – said teachers don’t have enough influence on what their local schools teach, compared with a quarter of Republican parents who held this view.

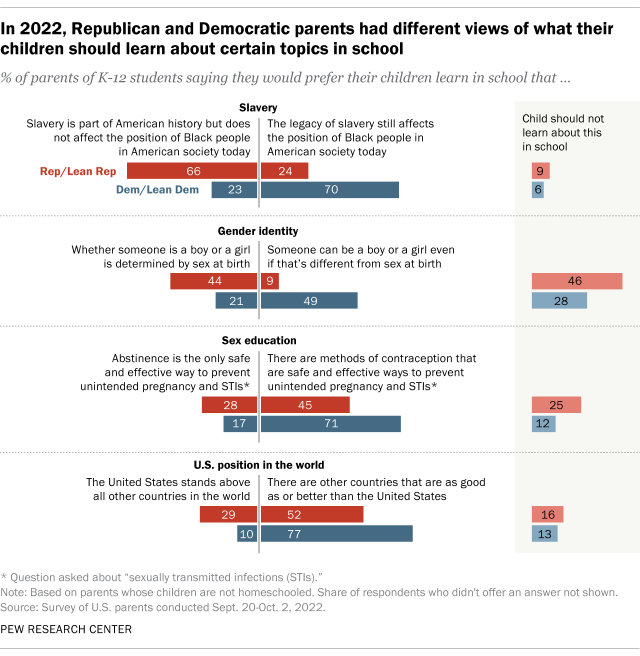

Republican and Democratic parents don’t agree on what their children should learn in school about certain topics. Take slavery, for example: While about nine-in-ten parents of K-12 students overall agreed in the fall 2022 survey that their children should learn about it in school, they differed by party over the specifics. About two-thirds of Republican K-12 parents said they would prefer that their children learn that slavery is part of American history but does not affect the position of Black people in American society today. On the other hand, 70% of Democratic parents said they would prefer for their children to learn that the legacy of slavery still affects the position of Black people in American society today.

Parents are also divided along partisan lines on the topics of gender identity, sex education and America’s position relative to other countries. Notably, 46% of Republican K-12 parents said their children should not learn about gender identity at all in school, compared with 28% of Democratic parents. Those shares were much larger than the shares of Republican and Democratic parents who said that their children should not learn about the other two topics in school.

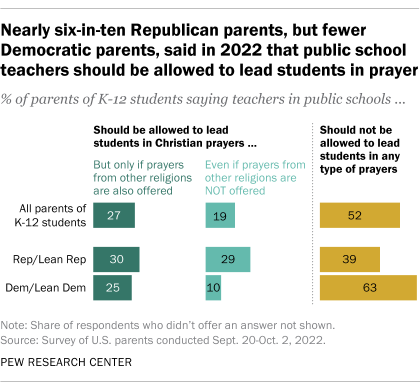

Many Republican parents see a place for religion in public schools , whereas a majority of Democratic parents do not. About six-in-ten Republican parents of K-12 students (59%) said in the same survey that public school teachers should be allowed to lead students in Christian prayers, including 29% who said this should be the case even if prayers from other religions are not offered. In contrast, 63% of Democratic parents said that public school teachers should not be allowed to lead students in any type of prayers.