- No category

The Castle - Language, Identity and Culture - Multimodal Assessment Task – Sample Scaffold - 2024

Related documents

Add this document to collection(s)

You can add this document to your study collection(s)

Add this document to saved

You can add this document to your saved list

Suggest us how to improve StudyLib

(For complaints, use another form )

Input it if you want to receive answer

Join Now to View Premium Content

GradeSaver provides access to 2360 study guide PDFs and quizzes, 11007 literature essays, 2767 sample college application essays, 926 lesson plans, and ad-free surfing in this premium content, “Members Only” section of the site! Membership includes a 10% discount on all editing orders.

The Castle (1997 Film)

Language and connections to culture in the castle anonymous 12th grade.

Texts employ language to urge readers to think more thoroughly about people's cultural ties. Language is used in a variety of ways to communicate cultural differences and group identity. This can be seen in Rob Sitch’s 1997 iconic film ‘The Castle’. Sitch highlights lanage and uses the characters to represent the Australian stereotypes and the Kerrigan families simplicity. The protagonist Darryl Kerrigan, who passionately depicts himself as an underdog and "Aussie battler" who tries to defend his family and his "Castle" against superior government power, is primarily responsible for the film's unique Australian vernacular language. Through this Daryl emphasises the value of a loving and respected family culture, which he feels is worth defending and gives an overall reflection of Australia's language, identity, and culture.

A person's or a group's identity is defined by the traits, beliefs, character, personality, appearance, or expressions that define them. Through language the Kerrigan family distinguishes themselves as a typical hard working Australian family who is fortunate and appreciative of being living and well which displays Australian identity .The Kerrigan family and their neighborhood's usage of language is highly...

GradeSaver provides access to 2312 study guide PDFs and quizzes, 10989 literature essays, 2751 sample college application essays, 911 lesson plans, and ad-free surfing in this premium content, “Members Only” section of the site! Membership includes a 10% discount on all editing orders.

Already a member? Log in

Language, Identity & Culture

In this module, you will examine how language is used to represent identity and culture. The culture in question is middle class Australia.

Context & Purpose

Although The Castle was released in the late 1990s, its aesthetic qualities are more reminiscent of the 1980s, and the values it explores are considered to be equally outdated – that is, the patriarchal family structure and conservatism of the Kerrigans evokes the idealised 1950s nuclear family and society more broadly.

That the film blends mid-century values with late-century aesthetics is not a coincidence; the 1980s and 1990s was a period of rapid change for not only Australia but the world, as globalisation prompted rapid urbanisation and the proliferation of technology – developments that were supported by rising immigration and multiculturalism. This was obviously extremely disruptive and presented a challenge to many Australians who could not keep up with the pace of change. It was during the late twentieth century that existing divisions between the working and upper classes became more prominent, as the wealth that came from globalisation was not distributed equally.

More immediately, the film was produced during a period of declining interest and funding in Australian media and entertainment. In consequence, the film was made on a low budget.

Relationship between Language and Collective Identity

The Castle makes the scope of the Kerrigans’ world immediately clear; they are a small-town family whose concerns do not extend beyond their neighbourhood, or even their home. From the outset, it is clear that language plays a crucial role in the formation and maintenance of their sense of identity: family dinners, and direct conversations are key. It is ultimately because this way of life is challenged that the Kerrigans find the legal battle with the government so destabilising and traumatic; they are unused to dealing with legal briefs, communicating through lawyers and, most obviously, the complex legal jargon used by the government and the courts.

We can track the disruption the legal battle causes to the Kerrigan’s sense of the world through the growing tension during dinnertime conversations, and gradual withdrawal of individual family members from family discussions.

It is then significant that it is ultimately Lawrence Hammill, with his distinctively sophisticated demeanour, is the person who is responsible for rescuing the Kerrigans from their crisis. Despite the glaring differences in their backgrounds, values and the ways in which they present themselves, the men are somehow able to form an alliance, as Hammill uses his legal knowledge, ostensibly provided to him by virtue of his privileged position in society, to aid Darryl. Indeed, the men are able to overcome their differences – best represented by their completely different use of language – to take down corporate Australia and the elitism it embodies.

The film also makes a comment on the nature of the relationship between White Australia and Australia’s Aboriginal heritage. This is most clearly represented when Darryl states ‘I’m really starting to understand how the Aborigines feel’ as he describes his anguish over the potential loss of his family home. Obviously, this is extremely insensitive, but it does capture the lack of understanding many Australians have of the history of colonisation and capitalism, which the film suggests is partly because of educational and class disparities.

Plot Summary

The film follows the story of the Kerrigan family, led by patriarch Darryl, as they engage in a legal battle against a private company, Airlink, and the local government over the planned expansion of the airport.

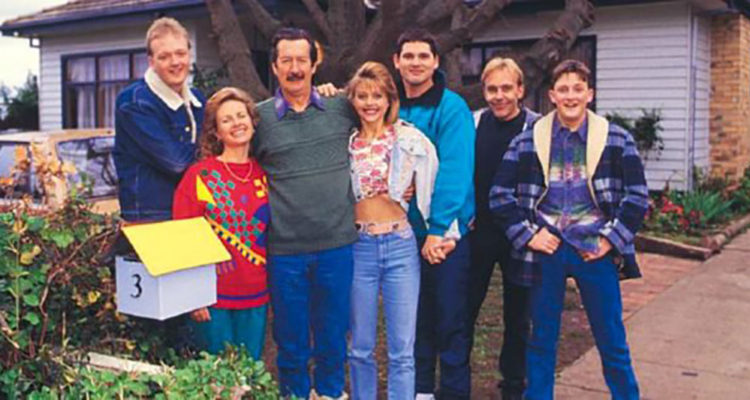

Dale, the eldest son, introduces us to his family via narration. He paints a portrait of a family that is as loving as it is unique and quirky. And yet, there is a degree of comfort and family that is found in the apparent wholesomeness of the Kerrigan situation.

The positive energy and humour radiated by the Kerrigans is disrupted when the local council orders for the land their house sits on to be valued. Shortly after, the Kerrigans receive a letter from the council, saying that their house has been compulsorily acquired. Outraged and confused, Darryl visits the local council, where he discovers that it is working in partnership with the state government and a private company, Airlink, to expand the airport. Darryl seeks legal counsel from the family solicitor, Dennis Denuto.

Dennis arranges for Darryl to attend the administrative affairs tribunal the following Monday, where he will make his case to retain his family home. Wanting to escape the bad energy created by the looming crisis, Darryl takes his family to Bonnie Doon in the meantime, where Tracey and Con (Dale’s older sister and her husband) recount a recent trip to Thailand and their experience of a new culture there. The family returns to their home revitalised and encouraged, but their energy is crushed when Darryl, accompanied to the tribunal by his neighbour Farouk, loses the case. Despite the loss, his determination remains intact.

A man arrives at the Kerrigan household and threatens Darryl to take the money offered by the government. Steve (Dale’s older brother) scares him off with a shotgun. This motivates Darryl to step up his protest campaign, and the next day, at a meeting with his neighbours, he organises to have Denis represent them at the Supreme Court.

As Darryl awaits the verdict at the Supreme Court, he speaks with Lawrence Hammill, the father of a barrister appearing for the first time. Darryl reveals the dilemma he’s in, before discovering that he’s lost his case.

A short while later, as Darryl is putting the contents of the pool room in his house into moving boxes and reminisces on the memories the room contains, he is visited by Lawrence Hammill. Hammill offers to represent Darryl at the High Court of Australia, pro bono (for free).

At the High Court, Hammill makes an emotional and passionate appeal, making reference to the Australian Constitution throughout. He is successful, and Darryl returns home victorious.

The film ends with a montage depicting the happy futures of the different residents. We see Wayne (another of Dale’s older brothers) released from prison, and most significantly, the unexpected friendship between Darryl and Hammill.

Cultural Assumptions

The text examines the following cultural assumptions that audiences, and society more broadly, may have about the Australian lower-middle class

That they are uneducated

The Castle demonstrates how language is used by people in positions of power to manipulate others, especially individuals who are already in a less privileged or powerful position, resulting in further disempowerment and marginalisation. The complex vocabulary and refined accent of the people working for Airlink and the lawyers is contrasted with the exaggerated accents of the Kerrigans, to further highlight their lack of education.

Throughout the text, the Kerrigans are constantly depicted making statements that are at most wildly ignorant, and at the very least reflective of a lack of education or knowledge about the world in which they exist. An example of this is Darryl’s ‘over-simplification’ of the Australian constitution, ‘it’s the vibe of the thing!’ makes clear his lack of education, even if his poor choice of words in this moment is mostly because of the strong emotions he’s feeling.

They have strong family values

The Castle reflects the extent to which long-held assumptions about what was valued by Australians came under threat by the growth of the corporate and political worlds. This is perhaps best encapsulated in the exchange between the Airlink lawyer and Darryl: the lawyer calls the Kerrigan family home ‘an eyesore,’ failing to see its sentimental significance as a symbol of the family’s hard work, and Darryl replies with ‘What are you calling an eyesore? It’s a home, you dickhead!’

The Kerrigans’ belief in the right to a home and the stability it provides is not shared by Denis and the others involved in the legal proceedings, who have a better grasp of the realities of the power of corporations and the relative insignificance of the Kerrigans’ position.

From the outset, the film emphasises the value the Kerrigans, especially the patriarch, Darryl, place on family. Think of the opening sequence, in which we see a vibrant, family dinner taking place. In the opening sequence depicts the Kerrigans sitting down for family dinner, with Darryl at the head of the table symbolising his importance as the patriarch and reaffirming conservative views of gender roles and family structure. This is reaffirmed by Dale’s narration, in which he characterises his father as the ‘backbone’ of the family.

That they are ignorant on racial issues

This is shown to be a product of Kerrigans’ ostensible lack of education. They frequently make racially insensitive comments or assumptions about their ethnic neighbours or friends. The film presents their racism in such a way so that we laugh and take pity on them for it. The Kerrigan’s ignorance towards racial issues is encapsulated within what is arguably the film’s most famous line: ‘I’m beginning to understand how the Aborigines feel… This house is like their land.’ Darryl’s reference to the issue of land rights reveals his basic understanding of the horrors and trauma suffered by Indigenous peoples, and his overall failure to grasp the inappropriateness of drawing a parallel between his situation and the attempted genocide of that population.

That they are suspicious of the upper classes

The Kerrigans believe hard, honest work is the only legitimate means to wealth and success. They simultaneously believe that ideals such as wealth and success are vapid, and that they shouldn’t be valued. It is this belief that forms the core of their suspicion of the upper classes; they do not think people who find fulfilment in making money from the exploitation and suffering of others should be respected. In the courtroom scene, the use of a high angle shot when the camera is pointed towards Darryl, depicting him from the judge’s perspective, and a low angle shot to represent his view of the judge, captures the resentment with which he interacts with the upper classes, and his grasp of the inequality that exists between his world and that of the judge’s.

The value of hard work

In a similar vein to their suspicion of the upper classes, the Kerrigans also believe that honest, hard work should be respected and valued. Whether the film affirms or challenges this assumption is a question with no clear answer. Indeed, it does both. But ultimately, it challenges it: we see the Kerrigans’ hard work and earnestness completely dismissed, and it is only by seeking the help of Hammill, a barrister, that they are able to win the court case. In the example ‘You know why people like that get their way? Because people like us don’t stand up to them. You’ve just got to play by the rules.’ This quote from Darryl reflects his belief in the Australian values of fairness and respect – values he does not see in the Airlink people.

That less-financially able individuals are able to be bought out

The idea that people like the Kerrigans, who have no real political influence or financial power, can simply be bought out by more powerful entities, is disrupted by Darryl’s decision to challenge the council and Airlink. Because of the value they place on family and hard work, and their suspicion of the upper classes, they refuse to simply be bought out. Darryl’s resistance to the idea that less-financially able individuals can simply be bought out is captured in his emotive declaration ‘You just can’t walk in and take a man’s house… It’s the law of bloody common sense.’ Notice too his use of distinctively Australian language to describe his situation – here, it becomes clear that he believes that what he is standing up for is at the heart of what it means to be Australian.

Studying The Crucible for your HSC?

quote table

< back to module a, the castle - visual aid.

- Festival Reports

- Book Reviews

- Great Directors

- Great Actors

- Special Dossiers

- Past Issues

- Support us on Patreon

Subscribe to Senses of Cinema to receive news of our latest cinema journal. Enter your email address below:

- Thank you to our Patrons

- Style Guide

- Advertisers

- Call for Contributions

Over-identification in The Castle : Recovering an Australian Classic’s Subversive Edge

“My name is Dale Kerrigan, and this is my story. Our family lives at 3 Highview Crescent, Coolaroo. Dad bought this place 15 years ago for a steal.” With these words, that open The Castle (Rob Sitch, 1997), the ideology that motivates the characters and that drives the film’s narrative becomes immediately manifest: identity is inextricably linked to home ownership, the foundation of the “Australian Dream”. Over the course of the film, tow‑truck driving, working class “battler” and Kerrigan patriarch, Darryl, defies a government agency’s attempts to compulsorily acquire his family’s home. Against all odds he succeeds in his appeal to the High Court, establishing the legal precedent that “a man’s home is his castle” – effectively codifying the ideology of the Australian Dream as law and recording a victory for the “ordinary man”.

In 2006, Mark Vaile, then Deputy Prime Minister of Australia, shared his admiration for The Castle . He is quoted as praising it for showing that “there is nothing more important than family and that sticking together through the tough times is what gets you through 2 .” Vaile is not alone in his appreciation of the film, which has become adored in Australia. Indeed, many Australians strongly identify with the The Castle ’s characters. A 2010 survey found that the general public felt the film best represented the “real Australia”, and that Darryl Kerrigan was their favourite Australian film character 3 . Select lines from the film, meanwhile, have become a part of Australian vernacular – most notably, “it’s the vibe of the thing,”, and Darryl’s oft-repeated “tell him he’s dreaming.”

Yet while The Castle ’s popularity may have proven beneficial for Australian cinema, it has also had the effect of dulling the film’s subversive edge. The purpose of this essay is to bring that subversive quality back to the fore. Throughout The Castle , audiences are amused by Darryl’s delight in the most simple of pleasures: his wife’s uninspiring cooking, the serenity experienced at the family’s kit home in rural Bonnie Doon, securing a bargain through the newspaper’s classifieds sections, or the many items that take pride of place in his home’s pool room. Yet our laughter at these “simple” figures – caricatures of naïve working‑class individuals, or “Aussie Battlers” – and the distance this laughter creates between the viewer and the character, actually operates as a self-denial on the part of the supposedly more enlightened audience of their own subjection to the very same ideology that informs the Kerrigans’ actions. Discussing the function of laughter, Mladen Dolar, a prominent member of the Ljubljana Lacanian School, writes:

Laughter is a condition of ideology. It provides us with the very space in which ideology can take its full swing. It is only with laughter that we become ideological subjects, withdrawn from the immediate pressure of ideological claims to a free enclave. It is only when we laugh and breathe freely that ideology truly has a hold on us – it is only here that it starts functioning fully as ideology, with the specifically ideological means, which are supposed to assure our free content and the appearance of spontaneity, eliminating the need for the non-ideological means of outside constraint. [emphasis in the original] 4

Yet our laughter at the The Castle ’s principal characters and their adherence to the ideology of the Australian Dream in fact reflects an obliviousness to our own embeddedness within this very same ideological framework. The way in which we establish ourselves as the father to the “children” that are the Kerrigans masks our own position as children in relation to the Ideological State Apparatuses (ISAs) that Louis Althusser identifies as operating to construct subjectivity 5 . The film’s exposure of patriarchal structures – Darryl taking charge to save his home and his family, and then his ultimate “rescue” thanks to the upper-crust Lawrence Hammill QC – reflects a political turn in Australia which, under the conservative government of John Howard that was elected in 1996, adopted a “leave it to the government” approach. As Lisa Milner has written, this was an era in which Australians were encouraged to feel at ease about their disengagement from politics 6

Developing on the above, this paper will argue that in The Castle ’s reflection of this ideological system, and of the individual’s ultimate powerlessness under it, there also exists the possibility for its very subversion. While for many The Castle may simply be a tale about a battler beating “the man” (as the Kerrigans’ comically incompetent lawyer Dennis Denuto puts it in court, “it’s your classic case of big business trying to take land and they couldn’t”), the film can also operate as a demystification and critique of prevailing ideology. Indeed, The Castle can be understood as overidentifying with ideology, and in the “surplus” of ideology in the film – this excessive association with the Australian Dream – there is a simultaneous affirmation and destabilisation of this very concept. This “subversive affirmation” – which will be explicated with reference to the writings of Inke Arns and Sylvia Sasse as well as through a consideration of Slovene musical group Laibach, early proponents of such strategies – in actuality has a political effect. However comic The Castle may be, its overt representation of ideology can actually be understood as enacting a self-reflexivity on the part of the viewer that undermines the disengagement from politics that was being encouraged in late 1990s Australia.

The Australian Dream and the Kerrigans

In order to better understand the context out of which The Castle emerges, some discussion of the “Australian Dream”, to which the Kerrigans subscribe, and which has become ingrained in the collective Australian psyche, is necessary. While comparable in many respects to its more famous American counterpart, the Australian Dream centres on ownership of a detached house on a fenced-off block of land – complete with that iconic Australian invention, the Hills Hoist rotary clothes line 7 . In a nation principally populated by those of a migrant background, home ownership has developed an integral importance as the ultimate reflection of the opportunity presented by a new start in Australia.

In fact, home ownership is so important in Australia that its achievement has been identified as the “defining moment” in the housing careers of nearly 70 per cent of households at any one point since the 1960s 8 . So common was home ownership by the 1990s, that in 1991, only five years before The Castle was filmed, nearly 90 per cent of households became home owners at some stage of their lives 9 . Fundamentally, home ownership operates as a safety net for Australian families, and a footing for economic and personal independence.

On more structural terms, the importance of home ownership is also predicated on its position as a cornerstone of the Australian welfare state. In his examination of this welfare state’s institutional design elements, Francis G. Castles concludes:

It is impossible to understand the adequacy of Australian income support provision … without some consideration of the role of home ownership. … In Australia, where the prevailing social policy strategy has involved the modification of the primary income distribution via wage control, but state welfare expenditure is relatively low, horizontal redistribution becomes primarily a responsibility of the individual rather than the State. Individuals must save enough from their current wages to meet future eventualities, by far the most significant of which is the need for adequate income support in old age. Under these circumstances, therefore, home ownership and occupational welfare become the major guarantees of horizontal distribution for most families 10 .

A working paper by the Australian Institute of Family Studies explains that Australia’s statutory mandate that a living wage be paid also brings with it the responsibility to save to provide for oneself in old age 11 . The age pension is modest, and claimants are always income and asset tested (and are barred from disposing of assets in the five years prior to making a claim for a pension). This has meant that the primary way Australians have saved for retirement is through the purchase of owner-occupied housing which then enables forced savings to accumulate as the asset value of the house transfers to the owner-occupier through mortgage repayments. The house is generally paid off by retirement, minimising both housing costs and the amount of income support needed in later life. Thus, as Castles identifies, saving for retirement in Australia is more individually centred, as opposed to the collective saving for social security provisions that typifies many European welfare states 12 .

Through The Castle , we can appreciate that it is the security of home ownership that allows Darryl to delight in those very simple pleasures we mock him for enjoying. Yet Darryl’s ambitions ultimately mirror those of the many viewers who identify with him. While we may laugh at him, we also share his concerns. Thus, at stake in Darryl’s attempts to resist the compulsory acquisition of 3 Highview Crescent is not simply retention of the family home, but those very freedoms and securities that stem from its possession and which are coveted by the film’s audience.

The viewer as father

Having provided an admittedly brief illumination of the Australian Dream, I wish now to offer an explanation, through the writings of Sigmund Freud, of how a viewer’s initial response to The Castle may operate. In his 1928 journal article on humour, Freud writes:

If we turn to consider the situation in which one person adopts a humorous attitude towards others, one view … is this: that the one is adopting towards the other the attitude of an adult towards a child, and smiling at the triviality of the interests and sufferings which seem to the child so big. Thus the humourist acquires his superiority by assuming the role of the grown-up, identifying himself to some extent with the father, while he reduces the other people to the position of children. 13

A superficial reading of The Castle may do just this. When a viewer giggles at the Kerrigans and what they enjoy, when they are amused by Dennis Denuto’s incompetence, they are laughing at them. After all, even if viewers of The Castle can relate to the Kerrigans, as indeed many do, it is unlikely they truly see themselves mirrored in the exaggerated caricatures on the screen. When we parrot dialogue from the film there is a tacit acknowledgement that, in repeating this dialogue, we are “stepping down” to the Kerrigans’ level. On Freudian terms, we are the “father” to the foolish Kerrigan children.

Yet in this laughter, and one’s positioning themselves in this way, what is really occurring is a denial of one’s own status as “child” to a broader ideological structure. Freud’s essay continues by stating:

…a man adopts a humorous attitude towards himself in order to ward off possible suffering. Is there any sense in saying that someone is treating himself like a child and is at the same time playing the part of the superior adult in relation to this child? 14

This is what ultimately occurs in this common response to The Castle . The laughter of the viewer, as they witness the Kerrigans’ almost cultish dedication and devotion to their house and the accompanying ideology around the Australian Dream, masks that very same viewer’s own embeddedness within that ideology (in the Australian context at least). As described above, the idea of home ownership is so fundamental to the constitution of the Australian state that the rhetoric of the Australian Dream is inescapable. It infiltrates every aspect of life in the country, every sector of society, and is ultimately unavoidable. The only difference between the “father” and the “child” in this instance, however, is that the Kerrigans are open about their identification with this ideology, while the amused viewer thinks themselves above interpellation.

The history of subversive affirmation and Laibach

Laibach, Laibach , 1980, linocut, 59 x 43 cm

It is in the Kerrigans’ overt identification with this ideology that a truly subversive edge to The Castle might be identified. It is the film’s excess of ideology that calls into question that ideology itself – a process that, in analogous circumstances, has been labelled “subversive affirmation”. A lucid overview of this concept and its history is provided by Inke Arns and Sylvia Sasse in their essay “Subversive Affirmation: On Mimesis as a Strategy of Resistance”. 15 While they locate its origins in the 1920s, Arns and Sasse attribute the increasing use of subversive affirmation in the West since the second half of the 1990s to the technique’s adoption in socialist Eastern Europe after the 1960s. They describe the practice as follows:

Subversive affirmation is an artistic/political tactic that allows artists/activists to take part in certain social, political or economic discourses and to affirm, appropriate, or consume them while simultaneously undermining them… In subversive affirmation there is always a surplus which destabilises affirmation and turns it into its opposite. 16

A paradigmatic example of this, and one necessary to interrogate before returning to The Castle , is the career of Slovene musical group Laibach – the musical wing of the broader multidisciplinary Neue Slowenische Kunst (NSK) art collective. Of the group, Alexei Monroe writes:

“Laibach” was the name by which the Slovene capital Ljubljana was known during the Nazi occupation of the city (1943-45) and under the Austrian Habsburg Empire (the name was first recorded in 1144). Laibach’s cross was not a direct reference to anything else, but had several associations. … [Among these are] the black cross markings on Second World War German military vehicles and aircraft 17 .

Laibach, The Deadly Dance , 1980, linocut, 59 x 43 cm

The problematic associations of the name Laibach, as well as the appropriation of military symbols and the violence of the posters announcing the group’s formation, naturally proved controversial, and Laibach developed some notoriety for what Marina Gržinić terms their “hyper-literal repetition of the totalitarian ritual 18 .” Arns and Sasse assert that:

With Laibach and NSK, we are dealing with a subversive strategy that Slavoj Žižek termed a radical “over-identification” with the “hidden reverse” of the ruling ideology regulating social relationships. By employing every identifying element delivered either explicitly or implicitly by the official ideology, Laibach Kunst and later Neue Slowenische Kunst appeared on stage and in public as an organisation that seemed “even more total that totalitarianism 19 .”

Two case studies provide examples of such over-identification. The first is an event of 1986-87, when the NSK’s Novi Kolektivizem (New Collectivism) design department submitted a creation based on a Nazi poster to a competition organised for the Day of Youth celebrated on 25 May, Tito’s birthday. They received first prize for their work which simply replaced certain Nazi insignia with Yugoslav equivalents. The committee judging submissions praised NSK for their poster, arguing that it “expresses the highest ideals of the Yugoslavian state.” The Day of Youth poster controversy exemplifies NSK’s working method during this period, which Anthony Gardner explains as follows:

… NSK did not slavishly illustrate the state ideals in the manner of socialist realism or other official aesthetics. Rather, it self-consciously and controversially combined such illustrations with images from earlier totalitarian regimes, suggesting an ideological continuum between post-Tito Yugoslavia and its oppressive antecedents 20 .

New Collectivism’s prize-winning work (left) and its Nazi antecedent (right)

This “hyper-literal repetition of the totalitarian ritual”, to repeat Gržinić’s words, also comes through in the aesthetics of Laibach’s music videos and live performances. Perhaps the best example is 1987’s “Opus Dei (Life is Life)”, which saw Laibach rework Austrian band Opus’ hit single “Live is Life”, turning the Top-40 feel‑good anthem on its head 21 . Gone was its catchy poppiness, replaced by distorted guitars and marching drums. Suddenly the track became a fascistic call-to-arms, with Laibach’s members appearing in olive military attire and polished army boots in the accompanying music video.

Still from the Laibach video Opus Dei (Life is Life), 1987, directed by Daniel Landin, published by Mute Records

When faced with such a video, and a live performance by Laibach that mirrors this same aesthetic, one does not know whether to laugh at the performance they are witnessing, or to be shocked by the overt identification with a totalitarian aesthetic. 22

Yet it is only in the continual replication of nationalist iconography that the totalitarian potential of that language can be revealed. And it is in the uncertainty as to how to respond to this language, and in the accompanying self-reflexivity, that the capacity for a critique of ideology exists.

Over-identification and The Castle

While much more could be written about Laibach and NSK, I wish now to return to The Castle . The concept of subversive affirmation, for which Laibach’s actions stand as a paradigmatic example, provides a useful framework for revisiting the film and unearthing its potential to operate as a critique of ideology. It goes without saying that in The Castle there is far more overt humour and irony than in the work of Laibach. The question of whether or not the film’s content should be taken seriously never arises, nor does the film question whether the state’s conduct is totalitarian in nature. Even if Laibach are mistaken in their positing of post-Tito Yugoslavia as such a totalitarian state, the belief nevertheless infuses their work, endowing it with a gravity arguably absent in a film like The Castle . Given this distinction, and The Castle ’s obviously comical nature, one might argue that there is no “over‑identification” in the film, and that only the Freudian reading of it offered earlier in this paper has currency.

However I wish to suggest, with specific reference to the unique Australian context – particularly in the aftermath of the 1996 election of John Howard’s Liberal Party to government – that over-identification and subversive affirmation are equally valid methods by which to deconstruct The Castle and its operation. As stated earlier, a large number of Australians genuinely identify with the Kerrigans; significantly, this reflects an Australian association with the underdog, and the figure of the “battler”. Crucially, the notion that the self-reliant individual constituted the backbone of Australian society was fostered by the Howard government that had just come to power when The Castle was released, and which would remain in office for eleven years thanks to the votes of working-class Australians termed “Howard’s Battlers”. Indeed, this reconstitution of the Australian as a “do-it-yourselfer” is reflected in the fact that The Castle was produced on a budget of only $750,000 AUD and filmed in a mere ten days. A low budget film that became a hit, it itself evidences the entrepreneurial spirit and self-sufficiency being championed at this time. In his examination of this period in Australian life, political scientist Don Aitken notes an increasing individualism taking hold in the country. He asserts that Australians

…have been advised, and are content, to settle for less, for a more individualistic view of society… we have lost a strong sense of what our country “stands for”, because that is a statement about “us” rather than about “me” 23 .

In The Castle , the Kerrigans are ultimately left to fend for themselves. Despite the incorporation of their neighbours into their struggle against the compulsory acquisition of their homes, there is an individualistic streak, as well as a degree of fortune, to their victory. They are the battlers “doing it tough” and their predicament reflects the change occurring in Australia during this period. Their helplessness is reflected by the fact that it is only the charitable intervention of Lawrence Hammill QC that saves the Kerrigans. As David Callahan writes:

Darryl Kerrigan succeeds through the system rather than against it, suggesting that it is only on the level of the personal that the system can be made to work; one can have no faith in civil mechanisms in the maintenance of civility 24 .

The Kerrigans’ slavish devotion to the Australian Dream, but ultimate vulnerability, reveals the absolute absurdity of the dismantling of Australia’s welfare state during this period – a support system which, as demonstrated, is so contingent upon private home ownership. Notwithstanding the Kerrigans’ success in court, by witnessing the family’s plight the film’s audience becomes conscious of their own comparable helplessness under neoliberalism. Responses of this nature are described by Arns and Sasse when they write:

… when speaking of subversive affirmation we are not dealing with critical distance but are confronted with a critique of aesthetic experience that – via identification – is about creating a physical/psychic experience of what is being criticised 25 .

The excess of ideology in The Castle operates to produce such an experience and a kind of subversive affirmation, with the viewer, despite how amusing they might find the Kerrigans, ultimately identifying with and relating to the precarity of their situation. Critically, by coming to realise the similarities they share – something made possible by the film’s excessive spotlighting of the “battler” figure – the viewer takes a critical first step in any attempt to resist the neoliberal turn that demands such self-reliance. Finally, in further support of a reading of The Castle as possessing a subversive quality, I wish to emphasise its conscious engagement with the contemporary political environment in Australia. During the film’s first courtroom scene, lawyer Dennis Denuto argues that the attempt to compulsorily acquire the Kerrigans’ home is in conflict with the “vibe” of the Constitution. In making this argument he cites as precedent 1992’s Mabo v Queensland (No. 2) , a landmark constitutional law case that rejected the doctrine of terra nullius , and in so doing recognised the existence and persistence of native title under common law. While this scene may be read as naïvely associating the struggles of the Kerrigans with those of Australia’s native population and their dispossession at the hands of their European colonisers, it also reflects an awareness and engagement with the Australian political landscape that supports a reading of the film as possessing a politically engaged, and indeed consciously subversive, edge.

While the popularity of The Castle may have blunted its subversive character, this very popularity is integral to the film’s political potential. The excess of ideology in the film allows viewers, particularly those in Australia, to perceive of their own position under neoliberalism, and develop an awareness of their construction as self-reliant “battlers”. However comic The Castle may be, its overt representation of Australia’s turn towards individualism operates as a necessary first step in any attempt to resist the neoliberal paradigm, and recover some sense of collectivity. It is also worth recognising that, even 21 years after its release, The Castle has not lost its relevance. As I write this paper, Australia’s ruling Liberal Party has changed its leader with the hope – amongst other things – that it will improve their prospects of re-election in 2019. In justifying the decision to depose a sitting Prime Minister – an increasingly regular occurrence over the past decade – one parliamentarian stated: “… [a new leader] will be able to reconnect with the Howard battlers [and] bring them back into the … fold 26 .” Not only are “Howard’s Battlers” as relevant as ever, but the importance of home ownership remains as fundamental to the constitution of Australian society, even if the purchase of a home is becoming increasingly unattainable for Australia’s younger generations. Given Australia’s increasingly bleak political outlook, now seems an ideal moment to revisit The Castle and rehabilitate its capacity to critique existing ideological structures, and, most importantly, to subvert their dominant rhetoric.

- This paper developed out of a seminar on cinema and ideology taken with Professor Pavle Levi at Stanford University, and I would like to thank him for his insightful feedback as I worked on a preliminary draft of the piece. ↩

- Mark Vaile, quoted in Lisa Milner, “Kenny: the evolution of the battler figure in Howard’s Australia,” Journal of Australian Studies 33, no. 2 (2009): p. 160. ↩

- See Isabel Hayes, “The Castle best represents Aussies,” The Sydney Morning Herald , 6 October 6 2010, http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/movies/the-castle-best-represents-aussies-20101006-1674q.html ; and “The Castle hero Darryl Kerrigan best represents Australians: survey,” The Australian , 6 October 2010, http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/the-castle-hero-darryl-kerrigan-represents-australians-best-survey/story-e6frg6n6-1225934896300 . ↩

- Mladen Dolar, cited in Alenka Zupančič, The Odd One In: On Comedy (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2008), p. 4. ↩

- See Louis Althusser, “Ideological State Apparatuses: Notes Towards an Investigation” in Lenin and Philosophy and other Essays , Ben Brewster, trans. (London: NLB, 1977), pp. 121-176. ↩

- Milner, “Kenny: the evolution of the battler figure in Howard’s Australia”: p. 157. During this era, social commentator Hugh Mackay also reflected that: ‘It’s really a case of leave it to (Prime Minister) Howard, leave it to the Government. See Hugh Mackay, quoted in Michelle Grattan, “Following Howard’s way to victory in war for a nation’s soul,” The Age , 21 February 2006, p. 1. ↩

- See David Hayward, “The Great Australian Dream reconsidered,” Housing Studies 1 (1986): p. 213; Jim Kemeny, The Myth of Home Ownership (London: Routledge Kegan Paul, 1981); and Ian Winter, The Radical Home Owner: Housing Tenure and Social Change (Basel: Gordon and Breach, 1994). ↩

- Steven C. Bourassa, Alastair W. Greig and Patrick N. Troy, “The limits of housing policy: home ownership in Australia,” Housing Studies 10, no. 1 (1995): p. 83. ↩

- Max Neutze and Hal L. Kendig, “Achievement of home ownership among post-war Australian cohorts,” Housing Studies 6, no. 1 (1991): p. 8. ↩

- Francis G. Castles, “The institutional design of the Australian Welfare State,” International Social Security Review 50, no. 2 (1997), pp. 33-4. ↩

- See Australian Institute of Family Studies, Social polarisation and housing careers: Exploring the interrelationship of labour and housing markets in Australia (Working Paper No. 13 – March 1998). ↩

- Francis G. Castles, The Working Class and Welfare (Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 1985). ↩

- Sigmund Freud, “Humour,” in The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis 9 (1928): p. 3. ↩

- Freud, “Humour”: pp. 3-4. ↩

- See Inke Arns and Sylvia Sasse, “Subversive Affirmation: On Mimesis as a Strategy of Resistance,” in East Art Map: Contemporary Art and Eastern Europe , IRWIN, ed. (Cambridge; London: MIT Press; Afterall, 2006), pp. 444-55. ↩

- Arns and Sasse, “Subversive Affirmation: On Mimesis as a Strategy of Resistance,” p. 445. ↩

- Alexei Monroe, Interrogation Machine: Laibach and NSK (Cambridge, Massachussets; London, England: The MIT Press, 2005), p. 3. ↩

- Marina Gržinić, “Neue Slowenische Kunst,” in Impossible Histories: Historical Avant-Gardes, Neo-Avant-Gardes, and Post-Avant-Gardes in Yugoslavia, 1918-1991 , Dubravka Djurić and Miško Šuvaković, eds. (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2003), p. 249. ↩

- Arns and Sasse, “Subversive Affirmation: On Mimesis as a Strategy of Resistance,” p. 448. ↩

- Anthony Gardner, Politically Unbecoming: Postsocialist Art Against Democracy (Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: The MIT Press, 2015), p. 120. ↩

- Monroe, Interrogation Machine , p. 231. ↩

- Don Aitken, “What Was It For?: The Inaugural Don Aitken Lecture,” University of Canberra, 25 November 2005. ↩

- David Callahan, “His Natural Whiteness: Modes of Ethnic Presence and Absence in Some Recent Australian Films,” in Australian Cinema in the 1990s , Ian Craven, ed. (London; Portland: Frank Cass, 2001), p. 105. ↩

- Arns and Sasse, “Subversive Affirmation: On Mimesis as a Strategy of Resistance,” p. 446. ↩

- Mathias Cormann, quoted in “Scott Morrison sworn in as Australia’s 30th prime minister – politics live”, The Guardian , 24 August 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/live/2018/aug/24/liberal-spill-malcolm-turnbull-peter-dutton-scott-morrison-liberal-spill-politics-parliament-live . ↩

'The Castle' - Module A - Language, Identity and Culture

This workshop offers practical ways into the 'Standard: Language, Identity and Culture' module and a fresh look at Sitch's The Castle. Course format: Online Presenter: Peita Mages Audience: Teachers teaching 'Language Identity & Culture’ wanting to expand their textual understanding & consider fresh approaches to teaching it. 5 professional development hours Pricing options Individual enrolment $285 + GST Team enrolment $1250 + GST FREE with subscription

Are you in NSW? If so, this is relevant for you

This course may contribute towards Elective PD hours. Visit https://educationstandards.nsw.edu.au for more details.

General Description

This workshop offers practical ways into the ‘Standard: Language, Identity and Culture’ module, including rubric breakdown. It further offers contextual insights (composer, social, historical) to situate your students in Sitch’s The Castle. Teaching and learning strategies and resources will be suggested to inform a smarter not harder approach in immersing students in the text.

Teachers teaching 'Language Identity & Culture’ wanting to expand their textual understanding & consider fresh approaches to teaching it.

Teaching Standards

2.1.2 Proficient Level - Know the content and how to teach it - Content and teaching strategies of the teaching area: Apply knowledge of the content and teaching strategies of the teaching area to develop engaging teaching activities,

3.2.2 Proficient Level - Plan for and implement Effective Teaching and Learning - Plan, structure and sequence learning programs: Plan and implement well-structured learning and teaching programs or lesson sequences that engage students and promote learning,

3.4.2 Proficient Level - Plan for and implement Effective Teaching and Learning - Select and use resources: Select and/or create and use a range of resources, including ICT, to engage students in their learning

Unlimited Online PD Subscriptions

From $249 +GST per teacher per year 200+ online PD courses across all key learning areas

Features of TTA Online PD

Availability.

Online courses are available 24/7. Designed to be done in your own time at your own pace.

Team Online

All online courses are available for team purchase. Unlimited teachers from the one Campus for any course for $1250 + GST

Money back Guarantee

If you complete less than 25% of an online course and aren't completely satisfied, let us know, and we will cancel your enrolment and provide a full refund.

- International

- Schools directory

- Resources Jobs Schools directory News Search

HSC Standard English Module A: The Castle Sample Essay and Essay Analysis

Subject: English

Age range: 16+

Resource type: Other

Last updated

21 September 2021

- Share through email

- Share through twitter

- Share through linkedin

- Share through facebook

- Share through pinterest

This is a three-part resource for students undertaking the NSW HSC Standard English Module A: Language, Identity, and Culture

A generic essay plan shows students how to compose an essay suitable for Stage 6, progressing them from the simpler PEEL/TEAL models of Stage 4 and 5.

A sample essay for the prescribed text, The Castle answers the 2019 HSC question:

Film relies on dialogue to create cultural tension. To what extent do you agree with this statement?

- There is also a second copy of the essay, marked up to show how it follows the plan, and with five short questions which require students to engage critically with the essay and its form.

Tes paid licence How can I reuse this?

Your rating is required to reflect your happiness.

It's good to leave some feedback.

Something went wrong, please try again later.

This resource hasn't been reviewed yet

To ensure quality for our reviews, only customers who have purchased this resource can review it

Report this resource to let us know if it violates our terms and conditions. Our customer service team will review your report and will be in touch.

Not quite what you were looking for? Search by keyword to find the right resource:

ENG 12: The Castle: Home

Image: Creative Commons

Resources and Links

- The Castle: Cheat Sheet. (SBS movies)

- The Castle: rewatching classic Australian films

- National identity

- Measuring the cultural value of Australia's screen sector.

- The Castle best represents Aussies.

- The Castle isn't a tribute to Aussie battlers

- Why are culture and identity important?

- The crisis of identity in Australia

- My Australia: How it has changed (2013)

- National identity: how fear of foreigners shapes us.

- Wikipedia article: Battler (Underdog)

- Families and cultural diversity in Australia

Once logged in to Clickview, see the attached Study Guide in the Chapters and resources section.

Module A: Language identity and culture. (From the NESA English Standard Stage 6 website)

Language has the power to both reflect and shape individual and collective identity. In this module, students consider how their responses to written, spoken, audio and visual texts can shape their self-perception. They also consider the impact texts have on shaping a sense of identity for individuals and/or communities.

Through their responding and composing students deepen their understanding of how language can be used to affirm, ignore, reveal, challenge or disrupt prevailing assumptions and beliefs about themselves, individuals and cultural groups.

Students study one prescribed text in detail, as well as a range of textual material to explore, analyse and assess the ways in which meaning about individual and community identity, as well as cultural perspectives, is shaped in and through texts. They investigate how textual forms and conventions, as well as language structures and features, are used to communicate information, ideas, values and attitudes which inform and influence perceptions of ourselves and other people and various cultural perspectives.

Through reading, viewing and listening, students analyse, assess and critique the specific language features and form of texts. In their responding and composing students develop increasingly complex arguments and express their ideas clearly and cohesively using appropriate register, structure and modality.

Students also experiment with language and form to compose imaginative texts that explore representations of identity and culture, including their own.

Students draft, appraise and refine their own texts, applying the conventions of syntax, spelling and grammar appropriately and for particular effects.

- Last Updated: Mar 15, 2021 11:34 AM

- URL: https://libguides.brigidine.nsw.edu.au/castle

- Texts and Human Experiences

- Shakespeare

- Textual Conversations

- Module A: Language Identity and Culture

- Module B: Critical Study of Texts

- Standard English

- George Orwell

- Module B: Close Study of Text

- Advanced English

- Billy Elliot

- Boy Behind the Curtain

- Crime Essay

- Drovers Wife

- Exam Strategies

- Extension English

- Favel Parrett

- Henry Lawson

- Indigenous Poetry

- Lawson Poetry

- Legal Studies

- Looking For Richard

- Merchant of Venice

- Mrs Dalloway

- Oodgeroo Noonuccal

- Ottawa Charter

- Past the Shallows

- Richard III

- Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes Poetry

- The Hollow Men

- The Truman Show

- Virginia Wolf

The Castle - Quotes and Analysis

Hello all, in this blog post we will be exploring Rob Sitch’s 1997 film ‘The Castle’ and its relation to the Standard English Module A: Language, Identity and Culture.

Let’s jump into the topic sentence:

Sitch utilises the narration of Dale, the protagonist Darryl’s son, and his distinct ‘Aussie’ vernacular to voice his thoughts in appreciation of his father and family. This distinct colloquial language features prevalent in the early stages of the film places the audience immediately in the context and setting of the Kerrigan home, a working class family living in the fictitious neighbourhood of Highview Crescent and provides a snapshot of ordinary Aussies with oversized, ‘larrikin’ personalities.

Remember to always attempt to connect each sentence , i.e. there must be a distinct flow between each sentence .

Darryl is immediately established as the central figure to the film, through his son’s narration, ‘Not Dad. He reckons power lines are a reminder of man’s ability to generate electricity. He’s always saying great things like that.’ The distinct Australian language is coupled with the low angle shot of Darryl hosing the garden, where the camera work and lighting is utilised to bathe Darryl in a positive ‘light’ emphasising not only Dale’s but the family’s appreciation for their father.

LINK to Topic Sentence and Question : Remember to utilise the key words of the question in your analysis...!

Furthermore, this uniquely Australian family identity is also displayed during the dinner scene, the traditional family setting of a dinner table is used with the distinct characterisation of Darryl’s sons. Their attire is simple and resembles Darryl while their haircuts are recognisable working class ‘mullets.’ Yet, this simplicity paves a unique and distinct family bond, conveyed through the voice-over, “Dad had a way of making everyone feel special.” This voice-over is reinforced with visuals of Darryl individually praising family members throughout dinner, specifically through the dialogue, “Go on, tell them, tell them…Dale dug a hole.” The mid shot portrays their elated facial expressions and body language as he sportingly ‘punches’ Dale.

Again, be sure to finish with a linking sentence and be sure to use the key terms of the question throughout the paragraph in order to engage with and answer the question!

*Please note that while this information is a great starting point for these texts, relying solely on the information in this post will not be enough to get a result in the top bands.

- The Castle Sitch Rob Sitch Module B Language Culture Identity Module A: Language Identity and Culture

This product has been added to your cart

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

2 Language, Identity, and Culture: Multiple Identity-Based Perspectives

Stella Ting-Toomey is a Professor of Human Communication Studies at California State University, Fullerton.

Department of Human Communication Studies California State University at Fullerton Fullerton, CA 92834 USA

- Published: 01 April 2014

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions