Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Abstract : The effects of THE EEFEECTS OF INCREASING FARE OF TRANSPORTATION TO SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS (2018-2019)

Related Papers

Ejay Gumanas

This study seeks to investigate the level of social security satisfaction of Grade 12 beneficiaries towards Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program (4P's). The researchers employed descriptive; cross-sectional research design and utilized a 22-item self-made questionnaire to measure the level of satisfaction with the use of 5-point Likert Scale, 1 as strongly disagree and 5 as strongly agree. The reliability of the questionnaire was evaluated with the use of Cronbach's alpha coefficient. The calculated alpha coefficient through SPSS software for the questionnaire was 0.981, which is an acceptable reliability. A total sample size of one hundred forty-one respondents were randomly chosen for the study. Mean was used to determine the level of satisfaction of the respondents towards 4P's and Paired t-test was utilized to find out the significant difference between two independent variables. Majority of the respondents were female rather than males and are aged 17-18 years old. Most of the respondents had siblings 4 and above. Furthermore, the study found out that the beneficiaries are satisfied with the cash grant provided by the 4P's and it fulfills their needs in terms of financial and educational. It is recommended for the 4P's students to maintain their spending lifestyle while it is advised for parents and school administration to consider the 4P's students given allowance. Observing different factors that may affect their spending lifestyle and satisfaction is also suggested.

Financial Literacy of Senior High School Students in Bacolod City

Angela Somcio

The research entitled LEVEL OF FINANCIAL LITERACY OF SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS FROM PRIVATE SCHOOLS OF BACOLOD CITY has the purpose to determine the level of financial literacy of senior high school students from different private schools of Bacolod City. The researchers made use of the descriptive-analytical scheme and the comparative correlational scheme to determine the objectives of the study. The study dwells on the areas spending habits, saving habits and financial knowledge in order to determine the overall financial knowledge. It uses the sex, grade level, district and family monthly income as variables. The researchers gathered data through thorough research and survey by form of a questionnaires. A total of 140 out of 9636 students from different private schools of Bacolod City were surveyed for this study. The findings of the study include concluding of having no significant difference in the level of financial literacy when participants are grouped according to grade level, district and family monthly income. But there is a significant difference in the level of financial literacy when grouped according to sex. Further results show that there are existing relationships between spending habits, saving habits and financial knowledge amongst each other. The general recommendation for this study was to educate regarding this matter the students may it be at home or in school. Specifically, schools organize seminars, parents are suggested to be examples and to teach their kids financial management at a young age and the local governments may include financial management as part of the current education system.

Mark Jay Lisay

There are no currently abstract for the research paper is not yet finished. Expect some error.

Cheneth Roque

International Journal of Advanced Research (IJAR)

IJAR Indexing

This qualitative study aimed to better understand the needs and challenges faced by SeniorHighSchool(SHS) Accountancy, Business, and Management(ABM) students in their journey of learning real life business problems. It utilizeda case study method in which the unit of analysis is the SHS Grade 11 and 12 ABM students of Simala National High School, a secondary public school in Cebu, Philippines. Analysis of transcribed interviews and observations from 20 key informants revealed the findings encapsulated in the following themes: a) ?Clamor for Work Immersion? which explains the need to expose the learners to hands on real world business activities; b) ?Demand for Learning Resources and Facilities? which entails the need for adequate print and non-print learner?s material, computers, and unlimited internet access; c) ?Request for Skilled and Experienced Teachers? which relates the need to hire teachers who are business graduates or have firsthand business experience; d) ?Time runs fast? which reveals the challenge of allocating enough time in all their projects particularly those involving data gathering outside school; and e) ?Funds empty fast? which shows the challenge of budgeting their allowances to be sufficient for their school requirement expenses. The school administration and teachers shall then address the needs through enhancing the work immersion plan, intensifying the school improvement plan, and hiring of qualified teachers. To cope with the challenges, the students need to develop time management skills and properly set priorities on where to allocate their available finances.

Ivan Vince Longa

Teté Contreras

ARSHI Veterinary Letters

Aji Winarso

Infestasi lalat penghisap darah dan keberadaan lalat pengganggu sangat merugikan bila dilihat dari potensi vektor maupun cekaman yang ditimbulkan terhadap sapi. Perubahan perilaku akibat gangguan lalat menimbulkan kerugian energi, berkurangnya waktu makan, dan hal ini dapat menurunkan produktivitas ternak. Penelitian ini merupakan penelitian survey yang bertujuan menggambarkan perilaku sapi Bali yang diinfestasi lalat penghisap darah dan dikitari lalat pengganggu. Penelitian dilakukan terhadap 8 ekor sapi yang digembalakan di padang gembala umum di Dusun Matani, Desa Penfui Timur, Kecamatan Kupang Tengah, Kabupaten Kupang melalui observasi keberadaan lalat pengganggu yang hinggap pada permukaan tubuh sapi. Selanjutnya perilaku sapi Bali yang dihinggapi lalat-lalat tersebut diamati pada saat sapi dalam kondisi istirahat (n=4) maupun sedang merumput (n=4). Data diolah dan ditampilkan secara statistik deskriptif. Hasil penelitian menunjukkan bahwa respon sapi terhadap keberadaan lalat ...

RELATED PAPERS

Clinical Autonomic Research

Peter Gauger

Clinical Therapeutics

Amy Chappell

Antonius Suparno

Revista Estudos Históricos

Shiguenoli Miyamoto

Ankith Reddy

American Sociological Review

Benjamin Cornwell

Cyprian Mielczarski

IEEE Transactions on Broadcasting

Muhammad Nawaz

Archives of Medical Science

Shaimaa Nasr Amin

Aida Azlina Mohd Bee

獨協大学ドイツ学研究 Dokkyo Universitat Germanistische Forschungsbeitrage

Werner Angelika

Recent Advances in Robotic Systems

Hayssam Serhan

Asian Journal of Medical Sciences

Aderonke Akinpelu

Journal of Advanced Research in Fluid Mechanics and Thermal Sciences

Abrar Muslim

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America

Tal Burstyn-Cohen

Patricia L O Z A N O Mendez

Patricia Canning

SSRN Electronic Journal

Amir Abbass Kazemzadeh Farizhandi

Enrique Perez Zapatero

Revista Brasileira De Terapia Intensiva

Enrique Correger

Photomedicine and laser surgery

Jacopo Lenzi

Sandrine Fréguin-Gresh

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Analyzing equity impacts of transit fare changes: Case study of Alameda-Contra Costa Transit, California

Affiliation.

- 1 University of California Transportation Center Berkeley, CA 94720-1782, United States. [email protected]

- PMID: 19616299

- DOI: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2009.06.009

Many public transit agencies consider increasing fares when faced with budget shortfalls. This paper analyzes the Alameda-Contra Costa (AC) Transit District's five alternative fare proposals introduced for public discussion in March 2005. The proposals combined fare hikes, base fare reductions, eliminations of free transfers, and discontinuation of periodic passes. Using the agency's 2002 on-board survey data, the study assessed the impacts of individual fare proposals on different subsets of riders and evaluated if they were equitable; and estimated potential fare revenues, using alternative price elasticities to estimate changes in ridership due to changes in price. The analysis revealed that proposals that increased the cost of transfers or eliminated unlimited-use passes produced dramatically unequal impacts on certain riders. Proposals for flat fares per ride were found to be least equitable, even when the base fare was lowered, because lower income riders, youth, and minorities made more trips and transferred more frequently than their more affluent counterparts. Proposals that maintained existing pass instruments and allowed transfers for small fees were the most favorable. The paper demonstrates the utility of on-board surveys and details an approach that could be widely used for evaluation of equity in public transit and other areas.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Research Support, U.S. Gov't, Non-P.H.S.

- Costs and Cost Analysis

- Models, Economic*

- Organizational Case Studies

- Program Evaluation*

- Public Sector / economics*

- Public Sector / organization & administration

- Socioeconomic Factors

- Transportation / economics*

- Help & FAQ

ATLANTA TRANSIT PRICING STUDY: MODERATING IMPACT OF FARE INCREASES ON POOR.

Research output : Contribution to journal › Article › peer-review

Alternative methods for moderating the impact of fare increases on low-income groups in Atlanta are described and evaluated. The study, sponsored by the Transportation Systems Center under the Service and Methods Demonstration Program, considers five alternatives to a flat fare increase: direct user subsidies, quality-based fares, reduced fares on designated routes, peak/off-peak fare differentials, and distance-based fares. We evaluate these fare strategies according to a set of standardized criteria that considers the target efficiency, coverage of the target group, administrative cost, total cost, and degree of relief offered by each option. The study finds that a direct user subsidy provides the highest degree of relief to low-income patrons with the lowest revenue loss. This is because user subsidies are more efficient in reaching the target population and offer a higher level of coverage of the poor than do other alternatives.

ASJC Scopus subject areas

- Civil and Structural Engineering

- Mechanical Engineering

Other files and links

- Link to publication in Scopus

- Link to the citations in Scopus

Fingerprint

- Demonstrations Engineering & Materials Science 100%

- Costs Engineering & Materials Science 93%

T1 - ATLANTA TRANSIT PRICING STUDY

T2 - MODERATING IMPACT OF FARE INCREASES ON POOR.

AU - Lovely, Mary E.

AU - Brand, Daniel

N2 - Alternative methods for moderating the impact of fare increases on low-income groups in Atlanta are described and evaluated. The study, sponsored by the Transportation Systems Center under the Service and Methods Demonstration Program, considers five alternatives to a flat fare increase: direct user subsidies, quality-based fares, reduced fares on designated routes, peak/off-peak fare differentials, and distance-based fares. We evaluate these fare strategies according to a set of standardized criteria that considers the target efficiency, coverage of the target group, administrative cost, total cost, and degree of relief offered by each option. The study finds that a direct user subsidy provides the highest degree of relief to low-income patrons with the lowest revenue loss. This is because user subsidies are more efficient in reaching the target population and offer a higher level of coverage of the poor than do other alternatives.

AB - Alternative methods for moderating the impact of fare increases on low-income groups in Atlanta are described and evaluated. The study, sponsored by the Transportation Systems Center under the Service and Methods Demonstration Program, considers five alternatives to a flat fare increase: direct user subsidies, quality-based fares, reduced fares on designated routes, peak/off-peak fare differentials, and distance-based fares. We evaluate these fare strategies according to a set of standardized criteria that considers the target efficiency, coverage of the target group, administrative cost, total cost, and degree of relief offered by each option. The study finds that a direct user subsidy provides the highest degree of relief to low-income patrons with the lowest revenue loss. This is because user subsidies are more efficient in reaching the target population and offer a higher level of coverage of the poor than do other alternatives.

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=0020224885&partnerID=8YFLogxK

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/citedby.url?scp=0020224885&partnerID=8YFLogxK

M3 - Article

AN - SCOPUS:0020224885

SN - 0361-1981

JO - Transportation Research Record

JF - Transportation Research Record

- Siloy is watching

- INQUIRER.net

- RADYO INQUIRER

Fare hike will impact on our budget – commuters

(CDN file photo)

CEBU CITY, Philippines — How do Cebuanos feel about the latest fare increase?

The Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board (LTFRB) approved on Friday, Sept. 16, 2022, the fare hikes for public utility jeepneys, buses, taxis, and ride-hailing applications that will take effect on October 4.

The LTFRB, in a statement, said they approved a P1 hike for traditional and modern jeepneys and a P2 hike for ordinary and aircon city buses as well as provincial buses. They also approved P5 hike for the flag-down rates of taxis and the Transportation Network Vehicle Services (TNVS).

READ: LTFRB OKs fare hike for public utility vehicles, TNVS by Oct. 4.

This weekend news, however, received various reactions from the commuters here in Cebu City.

For instance, Mary Joy Bagares said this was ‘alarming’ news that would impact on her monthly budget.

“Kay mahal na daan ang PUVs di na moroll back bisan ni rollback na ang gas. Nakisabay pud ang pletehan sa increase sa commodities. Hoping lang na there will be minimum wage hike pud,” she told CDN Digital.

(Because the fare for PUVs is already expensive and they won’t rollback their fare if there will be a gas rollback. The fare hike will go with the increase in commodities. We are just hoping that there will also be a minimum wage hike.)

In addition, Kate Denolang of Mandaue City said that she was “quite conflicted” over whether she would be happy with the benefits it would give to the drivers and others in the transportation industry or disheartened for the commuters as this would mean increased expenses.

But she decided to empathize with the common sentiments of the commuters. Though she had been working from home, Denolang said she still would have to commute to get essentials or run personal errands.

“It is quite disappointing that sometimes my transportation fees would own a bigger toll on my whole errand expenses. I usually commute via bus, e-jeep, taxi, and Angkas. From my P50-P100 transportation budget for every errand in 2021. Now, I need to budget at least P150-P300,” she said.

“How much more if the fare increases again? Am I willing to spend as much as P500 just for transportation? I don’t think so. I may be lucky to work from home, and I go out at most three times a week. But how about those who need to go out and travel daily to work? This would be very disheartening for them,” she added.

Likewise, Kent Anthony Jimenez, from Cebu City, said this would really take a toll on commuting employees who were mostly now in a return-to-office setup.

“I, personally, really hate this since I’m working in another city and I travel every day. I have to adjust my budget again even if it’s only a 1-2 pesos increase, since when accumulated, would take a big cut of my salary,” he said, noting that two separate fare hike implementations happened this year in just a couple of months.

The last fare hike took effect last July 1, which made the new minimum jeepney fare across the country at P11.

READ: Cebu PUJ drivers: P2 fare hike not enough to cover fuel costs

Meanwhile, Jolissa Taboada, told CDN Digital that she chose to see this development as a deserved augmentation of drivers’ income.

“Para nako kay okay ra nga gipasaka ang fare kay sa karong panahona, nagkamahal na sad baya ang mga paliton ug ang gas so dako kay ni nga tabang sa mga drivers ilabi na nga naghinay-hinay na ug balik sa normal tanan,” she said.

(For me, I am okay with the increase in the fare at this time, where the prices of commodities have also increased and the gasoline, so this is a big help to the drivers especially that we are all now slowly returning to normal.)

RELATED STORIES

CCTO helps enforce student fare discount law

CCTO ‘stepping up’ in putting order in Cebu City roads

Drivers told to honor 20 percent students fare discount even on weekends, holidays

P1 jeepney fare hike: As commuters pay more, drivers still suffer

Subscribe to our daily newsletter

By providing an email address. I agree to the Terms of Use and acknowledge that I have read the Privacy Policy .

Disclaimer: The comments uploaded on this site do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of management and owner of Cebudailynews. We reserve the right to exclude comments that we deem to be inconsistent with our editorial standards.

PHL Jiu-Jitsu team clinches 2 silver medals in JJIF Asian Youth tilt

Paras beats kyoguchi in a rematch in south korea, latest news, heat index in laoag, aparri may reach 46 °c on sunday – pagasa, embracing pain: the story of a lady cop and single mother, first person to receive a genetically modified pig kidney transplant dies nearly 2 months later, resort charges mayor due to excessive force during closure, featured stories, delayed gratification: cebu topnotcher’s sacrifices for academic success, yuchengco unit reports breakthrough in first solar plant in bohol, raymond garcia is acting cebu city mayor for 6 months, lapu-lapu city drowning: 5-year-old drowned by own half brother.

Subscribe to our regional newsletter

- Environment

© 2024 Cebu Daily News - All Rights Reserved

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. By continuing, you are agreeing to our use of cookies. To find out more, please click this link.

- Subscribe Now

LTFRB to study possibility of jeepney fare hike

Already have Rappler+? Sign in to listen to groundbreaking journalism.

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

FARE HIKE? Commuters inside a passenger jeepney at Tandang Sora, PUJ Terminal in Quezon City on September 15, 2020.

Darren Langit/Rappler

The Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board (LTFRB) will evaluate the possibility of a fare hike for jeepneys, amid the rising costs of fuel products and lower transport capacity.

During the Laging Handa briefing on Tuesday, October 12, LTFRB Executive Director Joel Bolano said that the agency has yet to receive an official petition on the matter, but it will “automatically” study the implications of a fare increase once the petition has been filed.

“Naiintindihan po natin ‘yung mataaas na fuel ngayon pero tinitignan din natin ‘yung capacity ng pasahero saka ng ating commuters sa ganitong sitwasyon na pandemic pa rin tayo,” Bolano said.

(We understand that fuel has been increasing but we also have to see if the passengers and the commuters can deal with it, given that we are still in a pandemic.)

In 2019, the LTFRB set a fare adjustment formula to account for fuel pump prices. This supposedly removes the need for transport groups to file for a petition when seeking fare increases.

According to Bolano, there should be a P1.26 increase if the formula is to be followed. With the current minimum fare, the total should be at P10.26 for the first four kilometers.

Transport group Pasang Masda earlier said it might seek for a P2 to P3 jeepney fare hike, unless the government either gives drivers fuel subsidy or allows them to carry more passengers.

Bolano on Tuesday did not categorically say that the regulatory board will provide fuel subsidy but he said that this program, which was implemented in 2018 and in 2019 , already has been proven to work.

“Yung mga beneficiaries, mga operators, may mga card na ito na galing sa Landbank. Mas mabilis-bilis kung ipappatupad uli ito. Ang challenge lang nito… Una, ‘yung iba po nagagamit hindi para sa fuel. May iilan na ginamit for ibang purpose. Pangalawa, may mga request din na dagdagan ang mga gas stations na pwede silang gumamit ng card,” Bolano said.

(The beneficiaries, the operators, they already have cash cards from Landbank. It would be faster if we implement this again. The challenges are, first, others did not use this for fuel. Some of them used the money for other purposes. Second, there were requests to increase the gas stations where they can use the card.)

On the request of Pasang Masda to increase the capacity of public utility vehicles, Bolano deferred to the Inter-Agency Task Force. In 2020, the Department of Transportation’s decision to reduce social distancing in public transport was met with criticism by health experts and the public.

Bolano said the LTFRB can only recommend the matter to the Department of Transportation, which represents the agency at the IATF.

In the past seven weeks, diesel price increases reached a total of P7.15.

The Department of Energy has said that it could not do anything with the increasing pump prices as it was due to increasing barrel prices in the global market.

US crude benchmark West Texas Intermediate hit a high of over $80 per barrel on Friday, October 8, the first time since November 2014 according to reports. The rallying prices were attributed to demand recovery, following the economic slump in 2020 . – Rappler.com

Add a comment

Please abide by Rappler's commenting guidelines .

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.

How does this make you feel?

Related Topics

Recommended Stories

{{ item.sitename }}, {{ item.title }}, new ride-hailing app indrive anticipates metro manila launch in may.

Bacolod legislators make last-ditch effort to avert jeepney crisis, unrest

LTFRB: 60% jeepney consolidation in NCR ‘more than enough’ for commuters

After deadline, unconsolidated jeepneys have until mid-May before LTFRB crackdown

Cagayan de Oro transport group at crossroads amid franchise consolidation deadline

Checking your Rappler+ subscription...

Upgrade to Rappler+ for exclusive content and unlimited access.

Why is it important to subscribe? Learn more

You are subscribed to Rappler+

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 08 May 2024

A meta-analysis on global change drivers and the risk of infectious disease

- Michael B. Mahon ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9436-2998 1 , 2 na1 ,

- Alexandra Sack 1 , 3 na1 ,

- O. Alejandro Aleuy 1 ,

- Carly Barbera 1 ,

- Ethan Brown ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0827-4906 1 ,

- Heather Buelow ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3535-4151 1 ,

- David J. Civitello 4 ,

- Jeremy M. Cohen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9611-9150 5 ,

- Luz A. de Wit ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3045-4017 1 ,

- Meghan Forstchen 1 , 3 ,

- Fletcher W. Halliday 6 ,

- Patrick Heffernan 1 ,

- Sarah A. Knutie 7 ,

- Alexis Korotasz 1 ,

- Joanna G. Larson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1401-7837 1 ,

- Samantha L. Rumschlag ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3125-8402 1 , 2 ,

- Emily Selland ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4527-297X 1 , 3 ,

- Alexander Shepack 1 ,

- Nitin Vincent ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8593-1116 1 &

- Jason R. Rohr ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8285-4912 1 , 2 , 3 na1

Nature ( 2024 ) Cite this article

2465 Accesses

432 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Infectious diseases

Anthropogenic change is contributing to the rise in emerging infectious diseases, which are significantly correlated with socioeconomic, environmental and ecological factors 1 . Studies have shown that infectious disease risk is modified by changes to biodiversity 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , climate change 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , chemical pollution 12 , 13 , 14 , landscape transformations 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 and species introductions 21 . However, it remains unclear which global change drivers most increase disease and under what contexts. Here we amassed a dataset from the literature that contains 2,938 observations of infectious disease responses to global change drivers across 1,497 host–parasite combinations, including plant, animal and human hosts. We found that biodiversity loss, chemical pollution, climate change and introduced species are associated with increases in disease-related end points or harm, whereas urbanization is associated with decreases in disease end points. Natural biodiversity gradients, deforestation and forest fragmentation are comparatively unimportant or idiosyncratic as drivers of disease. Overall, these results are consistent across human and non-human diseases. Nevertheless, context-dependent effects of the global change drivers on disease were found to be common. The findings uncovered by this meta-analysis should help target disease management and surveillance efforts towards global change drivers that increase disease. Specifically, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, managing ecosystem health, and preventing biological invasions and biodiversity loss could help to reduce the burden of plant, animal and human diseases, especially when coupled with improvements to social and economic determinants of health.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Towards common ground in the biodiversity–disease debate

Biological invasions facilitate zoonotic disease emergences

Measuring the shape of the biodiversity-disease relationship across systems reveals new findings and key gaps

Data availability.

All the data for this Article have been deposited at Zenodo ( https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8169979 ) 52 and GitHub ( https://github.com/mahonmb/GCDofDisease ) 53 .

Code availability

All the code for this Article has been deposited at Zenodo ( https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8169979 ) 52 and GitHub ( https://github.com/mahonmb/GCDofDisease ) 53 . R markdown is provided in Supplementary Data 1 .

Jones, K. E. et al. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature 451 , 990–994 (2008).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Civitello, D. J. et al. Biodiversity inhibits parasites: broad evidence for the dilution effect. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci USA 112 , 8667–8671 (2015).

Halliday, F. W., Rohr, J. R. & Laine, A.-L. Biodiversity loss underlies the dilution effect of biodiversity. Ecol. Lett. 23 , 1611–1622 (2020).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Rohr, J. R. et al. Towards common ground in the biodiversity–disease debate. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4 , 24–33 (2020).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Johnson, P. T. J., Ostfeld, R. S. & Keesing, F. Frontiers in research on biodiversity and disease. Ecol. Lett. 18 , 1119–1133 (2015).

Keesing, F. et al. Impacts of biodiversity on the emergence and transmission of infectious diseases. Nature 468 , 647–652 (2010).

Cohen, J. M., Sauer, E. L., Santiago, O., Spencer, S. & Rohr, J. R. Divergent impacts of warming weather on wildlife disease risk across climates. Science 370 , eabb1702 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Rohr, J. R. et al. Frontiers in climate change-disease research. Trends Ecol. Evol. 26 , 270–277 (2011).

Altizer, S., Ostfeld, R. S., Johnson, P. T. J., Kutz, S. & Harvell, C. D. Climate change and infectious diseases: from evidence to a predictive framework. Science 341 , 514–519 (2013).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Rohr, J. R. & Cohen, J. M. Understanding how temperature shifts could impact infectious disease. PLoS Biol. 18 , e3000938 (2020).

Carlson, C. J. et al. Climate change increases cross-species viral transmission risk. Nature 607 , 555–562 (2022).

Halstead, N. T. et al. Agrochemicals increase risk of human schistosomiasis by supporting higher densities of intermediate hosts. Nat. Commun. 9 , 837 (2018).

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Martin, L. B., Hopkins, W. A., Mydlarz, L. D. & Rohr, J. R. The effects of anthropogenic global changes on immune functions and disease resistance. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1195 , 129–148 (2010).

Rumschlag, S. L. et al. Effects of pesticides on exposure and susceptibility to parasites can be generalised to pesticide class and type in aquatic communities. Ecol. Lett. 22 , 962–972 (2019).

Allan, B. F., Keesing, F. & Ostfeld, R. S. Effect of forest fragmentation on Lyme disease risk. Conserv. Biol. 17 , 267–272 (2003).

Article Google Scholar

Brearley, G. et al. Wildlife disease prevalence in human‐modified landscapes. Biol. Rev. 88 , 427–442 (2013).

Rohr, J. R. et al. Emerging human infectious diseases and the links to global food production. Nat. Sustain. 2 , 445–456 (2019).

Bradley, C. A. & Altizer, S. Urbanization and the ecology of wildlife diseases. Trends Ecol. Evol. 22 , 95–102 (2007).

Allen, T. et al. Global hotspots and correlates of emerging zoonotic diseases. Nat. Commun. 8 , 1124 (2017).

Sokolow, S. H. et al. Ecological and socioeconomic factors associated with the human burden of environmentally mediated pathogens: a global analysis. Lancet Planet. Health 6 , e870–e879 (2022).

Young, H. S., Parker, I. M., Gilbert, G. S., Guerra, A. S. & Nunn, C. L. Introduced species, disease ecology, and biodiversity–disease relationships. Trends Ecol. Evol. 32 , 41–54 (2017).

Barouki, R. et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and global environmental change: emerging research needs. Environ. Int. 146 , 106272 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Nova, N., Athni, T. S., Childs, M. L., Mandle, L. & Mordecai, E. A. Global change and emerging infectious diseases. Ann. Rev. Resour. Econ. 14 , 333–354 (2021).

Zhang, L. et al. Biological invasions facilitate zoonotic disease emergences. Nat. Commun. 13 , 1762 (2022).

Olival, K. J. et al. Host and viral traits predict zoonotic spillover from mammals. Nature 546 , 646–650 (2017).

Guth, S. et al. Bats host the most virulent—but not the most dangerous—zoonotic viruses. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119 , e2113628119 (2022).

Nelson, G. C. et al. in Ecosystems and Human Well-Being (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment) Vol. 2 (eds Rola, A. et al) Ch. 7, 172–222 (Island Press, 2005).

Read, A. F., Graham, A. L. & Raberg, L. Animal defenses against infectious agents: is damage control more important than pathogen control? PLoS Biol. 6 , 2638–2641 (2008).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Medzhitov, R., Schneider, D. S. & Soares, M. P. Disease tolerance as a defense strategy. Science 335 , 936–941 (2012).

Torchin, M. E. & Mitchell, C. E. Parasites, pathogens, and invasions by plants and animals. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2 , 183–190 (2004).

Bellay, S., de Oliveira, E. F., Almeida-Neto, M. & Takemoto, R. M. Ectoparasites are more vulnerable to host extinction than co-occurring endoparasites: evidence from metazoan parasites of freshwater and marine fishes. Hydrobiologia 847 , 2873–2882 (2020).

Scheffer, M. Critical Transitions in Nature and Society Vol. 16 (Princeton Univ. Press, 2020).

Rohr, J. R. et al. A planetary health innovation for disease, food and water challenges in Africa. Nature 619 , 782–787 (2023).

Reaser, J. K., Witt, A., Tabor, G. M., Hudson, P. J. & Plowright, R. K. Ecological countermeasures for preventing zoonotic disease outbreaks: when ecological restoration is a human health imperative. Restor. Ecol. 29 , e13357 (2021).

Hopkins, S. R. et al. Evidence gaps and diversity among potential win–win solutions for conservation and human infectious disease control. Lancet Planet. Health 6 , e694–e705 (2022).

Mitchell, C. E. & Power, A. G. Release of invasive plants from fungal and viral pathogens. Nature 421 , 625–627 (2003).

Chamberlain, S. A. & Szöcs, E. taxize: taxonomic search and retrieval in R. F1000Research 2 , 191 (2013).

Newman, M. Fundamentals of Ecotoxicology (CRC Press/Taylor & Francis Group, 2010).

Rohatgi, A. WebPlotDigitizer v.4.5 (2021); automeris.io/WebPlotDigitizer .

Lüdecke, D. esc: effect size computation for meta analysis (version 0.5.1). Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1249218 (2019).

Lipsey, M. W. & Wilson, D. B. Practical Meta-Analysis (SAGE, 2001).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing Vol. 2022 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020); www.R-project.org/ .

Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J. Stat. Softw. 36 , 1–48 (2010).

Pustejovsky, J. E. & Tipton, E. Meta-analysis with robust variance estimation: Expanding the range of working models. Prev. Sci. 23 , 425–438 (2022).

Lenth, R. emmeans: estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means. R package v.1.5.1 (2020).

Bartoń, K. MuMIn: multi-modal inference. Model selection and model averaging based on information criteria (AICc and alike) (2019).

Burnham, K. P. & Anderson, D. R. Multimodel inference: understanding AIC and BIC in model selection. Sociol. Methods Res. 33 , 261–304 (2004).

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Marks‐Anglin, A. & Chen, Y. A historical review of publication bias. Res. Synth. Methods 11 , 725–742 (2020).

Nakagawa, S. et al. Methods for testing publication bias in ecological and evolutionary meta‐analyses. Methods Ecol. Evol. 13 , 4–21 (2022).

Gurevitch, J., Koricheva, J., Nakagawa, S. & Stewart, G. Meta-analysis and the science of research synthesis. Nature 555 , 175–182 (2018).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67 , 1–48 (2015).

Mahon, M. B. et al. Data and code for ‘A meta-analysis on global change drivers and the risk of infectious disease’. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8169979 (2024).

Mahon, M. B. et al. Data and code for ‘A meta-analysis on global change drivers and the risk of infectious disease’. GitHub github.com/mahonmb/GCDofDisease (2024).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank C. Mitchell for contributing data on enemy release; L. Albert and B. Shayhorn for assisting with data collection; J. Gurevitch, M. Lajeunesse and G. Stewart for providing comments on an earlier version of this manuscript; and C. Carlson and two anonymous reviewers for improving this paper. This research was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation (DEB-2109293, DEB-2017785, DEB-1518681, IOS-1754868), National Institutes of Health (R01TW010286) and US Department of Agriculture (2021-38420-34065) to J.R.R.; a US Geological Survey Powell grant to J.R.R. and S.L.R.; University of Connecticut Start-up funds to S.A.K.; grants from the National Science Foundation (IOS-1755002) and National Institutes of Health (R01 AI150774) to D.J.C.; and an Ambizione grant (PZ00P3_202027) from the Swiss National Science Foundation to F.W.H. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

These authors contributed equally: Michael B. Mahon, Alexandra Sack, Jason R. Rohr

Authors and Affiliations

Department of Biological Sciences, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, USA

Michael B. Mahon, Alexandra Sack, O. Alejandro Aleuy, Carly Barbera, Ethan Brown, Heather Buelow, Luz A. de Wit, Meghan Forstchen, Patrick Heffernan, Alexis Korotasz, Joanna G. Larson, Samantha L. Rumschlag, Emily Selland, Alexander Shepack, Nitin Vincent & Jason R. Rohr

Environmental Change Initiative, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, USA

Michael B. Mahon, Samantha L. Rumschlag & Jason R. Rohr

Eck Institute of Global Health, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN, USA

Alexandra Sack, Meghan Forstchen, Emily Selland & Jason R. Rohr

Department of Biology, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA

David J. Civitello

Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA

Jeremy M. Cohen

Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA

Fletcher W. Halliday

Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Institute for Systems Genomics, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, USA

Sarah A. Knutie

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

J.R.R. conceptualized the study. All of the authors contributed to the methodology. All of the authors contributed to investigation. Visualization was performed by M.B.M. The initial study list and related information were compiled by D.J.C., J.M.C., F.W.H., S.A.K., S.L.R. and J.R.R. Data extraction was performed by M.B.M., A.S., O.A.A., C.B., E.B., H.B., L.A.d.W., M.F., P.H., A.K., J.G.L., E.S., A.S. and N.V. Data were checked for accuracy by M.B.M. and A.S. Analyses were performed by M.B.M. and J.R.R. Funding was acquired by D.J.C., J.R.R., S.A.K. and S.L.R. Project administration was done by J.R.R. J.R.R. supervised the study. J.R.R. and M.B.M. wrote the original draft. All of the authors reviewed and edited the manuscript. J.R.R. and M.B.M. responded to reviewers.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jason R. Rohr .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information.

Nature thanks Colin Carlson and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended data fig. 1 prisma flowchart..

The PRISMA flow diagram of the search and selection of studies included in this meta-analysis. Note that 77 studies came from the Halliday et al. 3 database on biodiversity change.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Summary of the number of studies (A-F) and parasite taxa (G-L) in the infectious disease database across ecological contexts.

The contexts are global change driver ( A , G ), parasite taxa ( B , H ), host taxa ( C , I ), experimental venue ( D , J ), study habitat ( E , K ), and human parasite status ( F , L ).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Summary of the number of effect sizes (A-I), studies (J-R), and parasite taxa (S-a) in the infectious disease database for various parasite and host contexts.

Shown are parasite type ( A , J , S ), host thermy ( B , K , T ), vector status ( C , L , U ), vector-borne status ( D , M , V ), parasite transmission ( E , N , W ), free living stages ( F , O , X ), host (e.g. disease, host growth, host survival) or parasite (e.g. parasite abundance, prevalence, fecundity) endpoint ( G , P , Y ), micro- vs macroparasite ( H , Q , Z ), and zoonotic status ( I , R , a ).

Extended Data Fig. 4 The effects of global change drivers and subsequent subcategories on disease responses with Log Response Ratio instead of Hedge’s g.

Here, Log Response Ratio shows similar trends to that of Hedge’s g presented in the main text. The displayed points represent the mean predicted values (with 95% confidence intervals) from a meta-analytical model with separate random intercepts for study. Points that do not share letters are significantly different from one another (p < 0.05) based on a two-sided Tukey’s posthoc multiple comparison test with adjustment for multiple comparisons. See Table S 3 for pairwise comparison results. Effects of the five common global change drivers ( A ) have the same directionality, similar magnitude, and significance as those presented in Fig. 2 . Global change driver effects are significant when confidence intervals do not overlap with zero and explicitly tested with two-tailed t-test (indicated by asterisks; t 80.62 = 2.16, p = 0.034 for CP; t 71.42 = 2.10, p = 0.039 for CC; t 131.79 = −3.52, p < 0.001 for HLC; t 61.9 = 2.10, p = 0.040 for IS). The subcategories ( B ) also show similar patterns as those presented in Fig. 3 . Subcategories are significant when confidence intervals do not overlap with zero and were explicitly tested with two-tailed one sample t-test (t 30.52 = 2.17, p = 0.038 for CO 2 ; t 40.03 = 4.64, p < 0.001 for Enemy Release; t 47.45 = 2.18, p = 0.034 for Mean Temperature; t 110.81 = −4.05, p < 0.001 for Urbanization); all other subcategories have p > 0.20. Note that effect size and study numbers are lower here than in Figs. 3 and 4 , because log response ratios cannot be calculated for studies that provide coefficients (e.g., odds ratio) rather than raw data; as such, all observations within BC did not have associated RR values. Despite strong differences in sample size, patterns are consistent across effect sizes, and therefore, we can be confident that the results presented in the main text are not biased because of effect size selection.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Average standard errors of the effect sizes (A) and sample sizes per effect size (B) for each of the five global change drivers.

The displayed points represent the mean predicted values (with 95% confidence intervals) from the generalized linear mixed effects models with separate random intercepts for study (Gaussian distribution for standard error model, A ; Poisson distribution for sample size model, B ). Points that do not share letters are significantly different from one another (p < 0.05) based on a two-sided Tukey’s posthoc multiple comparison test with adjustment for multiple comparisons. Sample sizes (number of studies, n, and effect sizes, k) for each driver are as follows: n = 77, k = 392 for BC; n = 124, k = 364 for CP; n = 202, k = 380 for CC; n = 517, k = 1449 for HLC; n = 96, k = 355 for IS.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Forest plots of effect sizes, associated variances, and relative weights (A), Funnel plots (B), and Egger’s Test plots (C) for each of the five global change drivers and leave-one-out publication bias analyses (D).

In panel A , points are the individual effect sizes (Hedge’s G), error bars are standard errors of the effect size, and size of the points is the relative weight of the observation in the model, with larger points representing observations with higher weight in the model. Sample sizes are provided for each effect size in the meta-analytic database. Effect sizes were plotted in a random order. Egger’s tests indicated significant asymmetries (p < 0.05) in Biodiversity Change (worst asymmetry – likely not bias, just real effect of positive relationship between diversity and disease), Climate Change – (weak asymmetry, again likely not bias, climate change generally increases disease), and Introduced Species (relatively weak asymmetry – unclear whether this is a bias, may be driven by some outliers). No significant asymmetries (p > 0.05) were found in Chemical Pollution and Habitat Loss/Change, suggesting negligible publication bias in reported disease responses across these global change drivers ( B , C ). Egger’s test included publication year as moderator but found no significant relationship between Hedge’s g and publication year (p > 0.05) implying no temporal bias in effect size magnitude or direction. In panel D , the horizontal red lines denote the grand mean and SE of Hedge’s g and (g = 0.1009, SE = 0.0338). Grey points and error bars indicate the Hedge’s g and SEs, respectively, using the leave-one-out method (grand mean is recalculated after a given study is removed from dataset). While the removal of certain studies resulted in values that differed from the grand mean, all estimated Hedge’s g values fell well within the standard error of the grand mean. This sensitivity analysis indicates that our results were robust to the iterative exclusion of individual studies.

Extended Data Fig. 7 The effects of habitat loss/change on disease depend on parasite taxa and land use conversion contexts.

A) Enemy type influences the magnitude of the effect of urbanization on disease: helminths, protists, and arthropods were all negatively associated with urbanization, whereas viruses were non-significantly positively associated with urbanization. B) Reference (control) land use type influences the magnitude of the effect of urbanization on disease: disease was reduced in urban settings compared to rural and peri-urban settings, whereas there were no differences in disease along urbanization gradients or between urban and natural settings. C) The effect of forest fragmentation depends on whether a large/continuous habitat patch is compared to a small patch or whether disease it is measured along an increasing fragmentation gradient (Z = −2.828, p = 0.005). Conversely, the effect of deforestation on disease does not depend on whether the habitat has been destroyed and allowed to regrow (e.g., clearcutting, second growth forests, etc.) or whether it has been replaced with agriculture (e.g., row crop, agroforestry, livestock grazing; Z = 1.809, p = 0.0705). The displayed points represent the mean predicted values (with 95% confidence intervals) from a metafor model where the response variable was a Hedge’s g (representing the effect on an infectious disease endpoint relative to control), study was treated as a random effect, and the independent variables included enemy type (A), reference land use type (B), or land use conversion type (C). Data for (A) and (B) were only those studies that were within the “urbanization” subcategory; data for (C) were only those studies that were within the “deforestation” and “forest fragmentation” subcategories. Sample sizes (number of studies, n, and effect sizes, k) in (A) for each enemy are n = 48, k = 98 for Virus; n = 193, k = 343 for Protist; n = 159, k = 490 for Helminth; n = 10, k = 24 for Fungi; n = 103, k = 223 for Bacteria; and n = 30, k = 73 for Arthropod. Sample sizes in (B) for each reference land use type are n = 391, k = 1073 for Rural; n = 29, k = 74 for Peri-urban; n = 33, k = 83 for Natural; and n = 24, k = 58 for Urban Gradient. Sample sizes in (C) for each land use conversion type are n = 7, k = 47 for Continuous Gradient; n = 16, k = 44 for High/Low Fragmentation; n = 11, k = 27 for Clearcut/Regrowth; and n = 21, k = 43 for Agriculture.

Extended Data Fig. 8 The effects of common global change drivers on mean infectious disease responses in the literature depends on whether the endpoint is the host or parasite; whether the parasite is a vector, is vector-borne, has a complex or direct life cycle, or is a macroparasite; whether the host is an ectotherm or endotherm; or the venue and habitat in which the study was conducted.

A ) Parasite endpoints. B ) Vector-borne status. C ) Parasite transmission route. D ) Parasite size. E ) Venue. F ) Habitat. G ) Host thermy. H ) Parasite type (ecto- or endoparasite). See Table S 2 for number of studies and effect sizes across ecological contexts and global change drivers. See Table S 3 for pairwise comparison results. The displayed points represent the mean predicted values (with 95% confidence intervals) from a metafor model where the response variable was a Hedge’s g (representing the effect on an infectious disease endpoint relative to control), study was treated as a random effect, and the independent variables included the main effects and an interaction between global change driver and the focal independent variable (whether the endpoint measured was a host or parasite, whether the parasite is vector-borne, has a complex or direct life cycle, is a macroparasite, whether the study was conducted in the field or lab, habitat, the host is ectothermic, or the parasite is an ectoparasite).

Extended Data Fig. 9 The effects of five common global change drivers on mean infectious disease responses in the literature only occasionally depend on location, host taxon, and parasite taxon.

A ) Continent in which the field study occurred. Lack of replication in chemical pollution precluded us from including South America, Australia, and Africa in this analysis. B ) Host taxa. C ) Enemy taxa. See Table S 2 for number of studies and effect sizes across ecological contexts and global change drivers. See Table S 3 for pairwise comparison results. The displayed points represent the mean predicted values (with 95% confidence intervals) from a metafor model where the response variable was a Hedge’s g (representing the effect on an infectious disease endpoint relative to control), study was treated as a random effect, and the independent variables included the main effects and an interaction between global change driver and continent, host taxon, and enemy taxon.

Extended Data Fig. 10 The effects of human vs. non-human endpoints for the zoonotic disease subset of database and wild vs. domesticated animal endpoints for the non-human animal subset of database are consistent across global change drivers.

(A) Zoonotic disease responses measured on human hosts responded less positively (closer to zero when positive, further from zero when negative) than those measured on non-human (animal) hosts (Z = 2.306, p = 0.021). Note, IS studies were removed because of missing cells. (B) Disease responses measured on domestic animal hosts responded less positively (closer to zero when positive, further from zero when negative) than those measured on wild animal hosts (Z = 2.636, p = 0.008). These results were consistent across global change drivers (i.e., no significant interaction between endpoint and global change driver). As many of the global change drivers increase zoonotic parasites in non-human animals and all parasites in wild animals, this may suggest that anthropogenic change might increase the occurrence of parasite spillover from animals to humans and thus also pandemic risk. The displayed points represent the mean predicted values (with 95% confidence intervals) from a metafor model where the response variable was a Hedge’s g (representing the effect on an infectious disease endpoint relative to control), study was treated as a random effect, and the independent variable of global change driver and human/non-human hosts. Data for (A) were only those diseases that are considered “zoonotic”; data for (B) were only those endpoints that were measured on non-human animals. Sample sizes in (A) for zoonotic disease measured on human endpoints across global change drivers are n = 3, k = 17 for BC; n = 2, k = 6 for CP; n = 25, k = 39 for CC; and n = 175, k = 331 for HLC. Sample sizes in (A) for zoonotic disease measured on non-human endpoints across global change drivers are n = 25, k = 52 for BC; n = 2, k = 3 for CP; n = 18, k = 29 for CC; n = 126, k = 289 for HLC. Sample sizes in (B) for wild animal endpoints across global change drivers are n = 28, k = 69 for BC; n = 21, k = 44 for CP; n = 50, k = 89 for CC; n = 121, k = 360 for HLC; and n = 29, k = 45 for IS. Sample sizes in (B) for domesticated animal endpoints across global change drivers are n = 2, k = 4 for BC; n = 4, k = 11 for CP; n = 7, k = 20 for CC; n = 78, k = 197 for HLC; and n = 1, k = 2 for IS.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information.

Supplementary Discussion, Supplementary References and Supplementary Tables 1–3.

Reporting Summary

Peer review file, supplementary data 1.

R markdown code and output associated with this paper.

Supplementary Table 4

EcoEvo PRISMA checklist.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Mahon, M.B., Sack, A., Aleuy, O.A. et al. A meta-analysis on global change drivers and the risk of infectious disease. Nature (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07380-6

Download citation

Received : 02 August 2022

Accepted : 03 April 2024

Published : 08 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07380-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing: Anthropocene newsletter — what matters in anthropocene research, free to your inbox weekly.

Economic Effects of Tighter Lending by Banks

Download PDF (299 KB)

FRBSF Economic Letter 2024-11 | May 6, 2024

Banks tightened the criteria used to approve loans over the past year. Analysis shows that their tighter lending standards can be partially explained by economic conditions that reduce demand for loans and increase their potential risk, such as policy rate increases and a slowing economy. The unexplained part may reflect a restrained credit supply, specifically related to banks being less willing or able to take on risk. What are the potential economic consequences? Past credit supply shocks have had significant long-lasting effects on unemployment but less impact on inflation.

The first half of 2023 was characterized by credit market turbulence, including the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and others. The increased uncertainty in the banking sector that followed these closures led many banks to tighten their credit standards, becoming stricter about the conditions under which they were willing to lend. According to the Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices (SLOOS), lending standards in 2023 tightened to a degree only seen during the Global Financial Crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. This leads to questions about the possible effects on the overall economy, particularly whether tighter standards resulted from an unexpected drop in the credit supply or other economic factors, such as higher interest rates or a slowing of the economy.

In this Economic Letter , I analyze supply and demand factors in credit market conditions and their impact on bank lending standards, like Lown and Morgan (2006) and others. A measure based on reports from bank loan officers shows that credit conditions began tightening in mid-2022, well before the bank closures. Since early 2023, about half of the tightening in lending standards has been due to changes in the credit supply specific to the banking sector, such as banks reevaluating their willingness to take on risk, and the remainder in response to other economic conditions. My analysis also estimates that unexpected changes to credit supply conditions—including the March 2023 bank closures—can account for 0.4 percentage point of unemployment by the end of 2023, meaning that unemployment in that quarter would have been 3.3% without the credit supply shock. My estimates suggest that the effects related to these credit supply shocks will be persistent, lasting through 2026. The contribution of these shocks to inflation is likely to be more subdued, pushing core personal consumption expenditures (PCE) inflation down by less than a 0.1 percentage point through 2026.

Bank lending standards and the economy

Bank lending to businesses depends on two key components: the loan interest rate and the lending standards that businesses need to meet to qualify for a loan. When banks are more willing to take on risk, they impose minimal lending standards; by contrast, when banks prefer to take on less risk, they scrutinize borrowers more and impose stricter conditions. The interest rate on loans responds to both credit supply and credit demand conditions. By contrast, lending standards are more directly related to the willingness or ability of banks to tolerate risk. Thus, they can be used as a proxy for credit supply conditions.

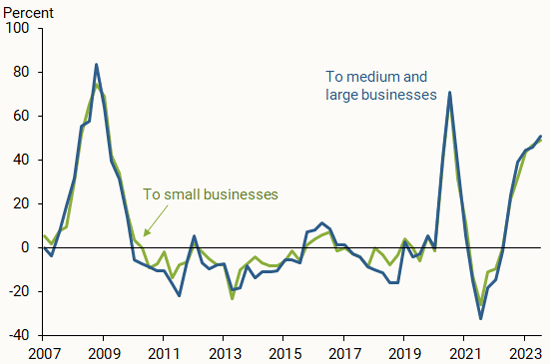

Using SLOOS data, I measure commercial and industrial bank lending conditions as the percentage of responding banks that report tighter lending standards minus the percentage that report easing of lending standards. The resulting measure can range from –100, meaning that all banks are easing standards, to 100, meaning that all banks are tightening standards. A positive (negative) number means that it is harder (easier) for firms to get credit. This method has been used by Lown and Morgan (2006) and other studies to measure credit supply conditions. Figure 1 shows the evolution of this measure from 2007 through 2023 for lending to medium and large businesses (blue line) and to small businesses (green line).

Figure 1 Tightening in commercial and industrial lending standards

The figure shows that lending standards tightened in 2023 to a degree seen only during the Global Financial Crisis in 2008 and the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. It also clearly shows that lending standards began tightening in the second half of 2022, well before the bank collapses in early 2023. Finally, the tightening in 2023 lending standards was very similar for all businesses regardless of their size. Therefore, I use the measure for medium and large firms as representative for the economy.

I use this measure in statistical analysis to estimate how credit conditions interact with the rest of the economy, particularly to understand their impact on unemployment and inflation. To measure unemployment, I focus on the unemployment gap, calculated as the difference between the measured unemployment rate and the Congressional Budget Office measure of the potential unemployment rate, and I use the core personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index to measure inflation.

My approach builds on the work of Lown and Morgan (2006), combining this measure of credit conditions with other measures of financial conditions. These include the effective federal funds rate, the 10-year Treasury constant maturity yield, the 30-year fixed mortgage rate spread relative to the 10-year Treasury yield, the BAA corporate bonds yield spread relative to 10-year Treasury bonds, and bank loans. Finally, to reflect forces that have recently been important in shaping the economy and inflation—namely supply chain pressures and significant changes in energy prices—I also include the West Texas Intermediate spot oil price, and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Global Supply Chain Pressures Index. The analysis uses data from 1998 through the second quarter of 2023.

My statistical model considers interactions between the different variables within the same quarter and over time. The SLOOS lending standards measure is observed early in the quarter and corresponds to bank responses from the previous quarter. Shocks to this measure are thus identified as changes in lending standards that do not respond to other variables within the same quarter. That is, tightening of standards can respond to this identified shock in the same quarter, and to other types of shocks from previous quarters.

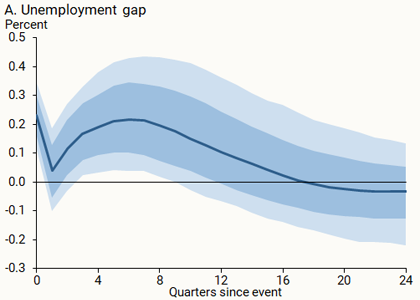

Figure 2 shows how much a 10 percentage point tightening in lending standards affects the unemployment gap and inflation. The horizontal axis shows the number of quarters since the shock took place. The vertical axis shows the increase in percentage points for each variable relative to the absence of tighter lending standards, with zero meaning no change in outcomes. The solid blue line is the median estimate, and the shaded areas represent the 70% (darker) and 90% (lighter) probability ranges of possible estimates.

Figure 2 Response of unemployment and inflation to a 10 percentage point tightening of lending standards

Note: Shading represents 70% (darker) and 90% (lighter) probability estimates around median estimate. Source: Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices and author’s calculations.

Overall, the tightening in lending standards induces a persistent increase in the unemployment gap and a small drop in inflation. The impact on unemployment is expected: tighter lending standards imply that firms cannot invest as much, reducing demand for credit in the economy. With weaker demand, firms will hire fewer workers and lay off some of their workforce, leading to higher unemployment.

The impact on inflation is more nuanced. On the one hand, a weaker demand for credit eases price inflation. On the other hand, as documented in Gilchrist and Zakrajsek (2012), tighter lending standards are also associated with higher interest rates, which increase operational costs for firms. Firms will pass some of those higher costs to their customers, leading to price inflation. Model estimates suggest the demand effect is more likely to prevail, and inflation falls slightly on net in response to tighter lending standards.

What led to tight lending standards in 2023?

Was the 2023 tightening in lending standards a pure credit supply shock, or was it a natural response of banks to evolving economic conditions? To address this question, I compare actual data at each point in time with the model’s predictions for that time to extract each component’s response to past shocks. I use the results to determine how much of the actual response of each component is due to shocks of different sources—for example, how much of the changing lending standards comes from responses to supply chain shocks or credit supply shocks.

The analysis suggests that credit supply shocks account for about 23 percentage points of the tighter lending standards in the first half of 2023. The remaining 22 percentage points of the tightening is associated with the response of lending standards to changes in economic conditions due to supply chain pressures and other factors originating outside the credit market.

The measure also shows that lending standards started to tighten before 2023, as early as the second quarter of 2022, as shown in Figure 1. This suggests that inflationary pressures and monetary policy tightening in previous quarters played a role in banking conditions more generally. Therefore, tighter credit standards may be related to the bank collapses in that they shared similar root causes in recent economic and financial conditions. However, credit supply factors in the first half of 2023 that could be associated with bank closures explain only part of the overall tightening of lending standards. Furthermore, my model estimates that the impact of the credit supply shock on tighter lending standards will be relatively short lived, dissipating by the end of 2024.

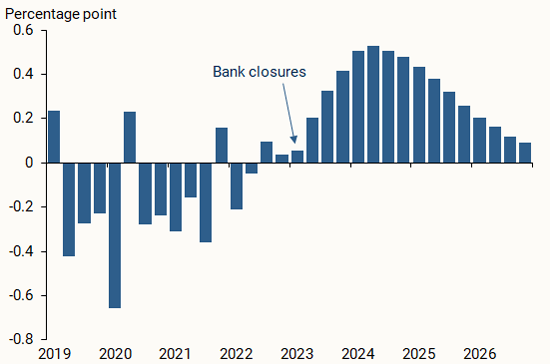

I next use this methodology to estimate how much credit supply shocks contributed to unemployment and inflation in the recent past and how much they are expected to contribute through 2026. To do this, I combine the estimated size of the shocks with the estimated responses of the economy to those shocks. The bars in Figure 3 show the median estimated contribution to unemployment.

Figure 3 Contribution of credit supply shocks to unemployment

The estimated contribution for the last quarter of 2023 is 0.4 percentage point, which means that unemployment would have been 3.3% without the credit supply shock, rather than the 3.7% reported in the data. My analysis shows that, even though the tightening of lending standards is not expected to last long, the effects on unemployment are estimated to persist through 2026. For inflation, the contribution of the credit supply shock is more subdued but more persistent, pulling inflation down by less than 0.1 percentage point through the entire projection into 2026. A persistent increase in corporate bond yield spreads implied by the credit supply shock may explain why the effects on the rest of the economy last so long.

This analysis has several limitations, including the possibility that underlying economic relations changed with the COVID-19 pandemic. Related to this, the model is proportional, implying that a shock of twice the size would have effects that are also twice the reported size. However, the unusually large shocks in this analysis could trigger more than proportional economic responses—for example, if cascading bank failures induced snowball effects in the economy due to an increasingly fragile banking system. Finally, using different measures to proxy for financial and monetary policy conditions could result in different estimates, although my tests using different data yielded similar results to those reported here.

In the first half of 2023, lending standards tightened substantially. This Letter finds that only about half of the tightening resulted from a credit supply shock that would have caused a slowdown in economic activity, while the remainder corresponds to banks’ normal response to overall economic conditions. While a tightening of lending standards is not expected to persist for very long, this analysis suggests it could add half a percentage point to unemployment through 2024 and push down inflation by a small amount.

Lown, Cara, and Donald P. Morgan. 2006. “The Credit Cycle and the Business Cycle: New Findings Using the Loan Officer Opinion Survey.” Journal of Money Credit and Banking 38(6).

Simon Gilchrist and Egon Zakrajsek. 2012. “Credit Spreads and Business Cycle Fluctuations.” American Economic Review 102(4, June), pp. 1,692–1,720.

Opinions expressed in FRBSF Economic Letter do not necessarily reflect the views of the management of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. This publication is edited by Anita Todd and Karen Barnes. Permission to reprint portions of articles or whole articles must be obtained in writing. Please send editorial comments and requests for reprint permission to [email protected]

Can heavy snowfall trigger earthquakes? A new study suggests a link

A new theory suggests that heavy snowfall could be a factor in triggering swarms of earthquakes — evidence that what’s happening on and above the Earth’s surface may play a role in events underground.

That’s according to a study published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances , which points to a potential link between heavy snowfall on Japan’s Noto Peninsula and thousands of quakes measured there since late 2020.

It’s one of the first studies to link changes in weather or climate to earthquake activity.

"Those big snowfall events seem to correlate well with the start of these big earthquake swarms," said William Frank, an author of the study and an assistant professor of Earth, atmospheric and planetary sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. "We shouldn’t forget the climate itself can also play a role in changing the stress state at depth where earthquakes are happening."

The study does not say that changes in climate or weather are directly causing earthquakes. Instead, it suggests that the rate of earthquakes in a given area could increase or decrease because of changes in how water is moving beneath the surface and how much pressure the weight of the snow exerts.

David Shelly, a research geophysicist with the United States Geological Society, said the study raises interesting questions, but more research is needed to validate its findings.

“What they’re showing is that seismicity seems to initiate and ramp up following these times of snowfall. It’s an intriguing observation, I’m not sure it’s conclusive,” he said.

Still, Shelly expects other seismologists to be keenly interested in the research.

“The sequence is a subject of a lot of interest in the community. This is the first paper that suggests there might be an environmental factor,” Shelly said.

The study evaluated thousands of earthquakes on Japan’s Noto Peninsula, which is located about 190 miles northwest of Tokyo on the Sea of Japan. In 2021, after a heavy snow, the rate of earthquakes in the area rose substantially — with hundreds recorded each day.

“They were seeing a factor-10 increase in the number of earthquakes in this region compared to what was happening previously,” Frank said.

The biggest in the swarm was a magnitude-7.5 earthquake on New Year’s Day of this year. More than 240 deaths were linked to this mainshock event, according to the Japanese Red Cross Society .

The timing of the swarm was also unusual compared to a typical sequence of aftershocks, according to Frank.

“They have this statistical signature of earthquakes being driven by something else,” he said.

He and the other study authors compared the pattern of earthquakes in the Noto Peninsula with a model of pressure within pores under the Earth’s surface. The model accounts for above-ground factors that change the pressure within the rock underneath — such as seasonal sea-level changes, fluctuations in atmospheric pressure and heavy rain or snow events.

The results indicated that the weight of the snowpack on the Noto Peninsula increased the pressure in those pores. Pressure changes from adding and removing weight as snow accumulates and then melts can destabilize pre-existing faults, the researchers think.

“If you have enough snow, you’ll actually be pushing the earth down and if you take the snow off, it will bounce back up,” Frank said.

Some previous research has also suggested that environmental factors can play a role in initiating earthquakes. In a 2019 study , Shelly and his colleagues found that spring snowmelt flowing into cracks in the earth near a caldera in the area around Mammoth Lakes, California, likely triggered a swarm of earthquakes.

The snowmelt recharged groundwater rapidly, and the pressure changes appeared to trigger activity on relatively shallow faults. The researchers found that seismic activity in the region was historically about 37 times more likely during wet periods than dry.

Research like this has piqued scientists’ curiosity about whether climate change could have a small influence on earthquake behavior.

“There are more studies that show a connection in some cases between the timing of earthquakes and these processes happening on the surface,” Shelly said. “What I understand of climate change forecasts is that there’s more extreme weather, more periods of prolonged drought and extreme wet periods. That might make these effects more obvious.”

Evan Bush is a science reporter for NBC News. He can be reached at [email protected].

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Environmental Changes Are Fueling Human, Animal and Plant Diseases, Study Finds

Biodiversity loss, global warming, pollution and the spread of invasive species are making infectious diseases more dangerous to organisms around the world.

By Emily Anthes

Several large-scale, human-driven changes to the planet — including climate change, the loss of biodiversity and the spread of invasive species — are making infectious diseases more dangerous to people, animals and plants, according to a new study.

Scientists have documented these effects before in more targeted studies that have focused on specific diseases and ecosystems. For instance, they have found that a warming climate may be helping malaria expand in Africa and that a decline in wildlife diversity may be boosting Lyme disease cases in North America.

But the new research, a meta-analysis of nearly 1,000 previous studies, suggests that these patterns are relatively consistent around the globe and across the tree of life.

“It’s a big step forward in the science,” said Colin Carlson, a biologist at Georgetown University, who was not an author of the new analysis. “This paper is one of the strongest pieces of evidence that I think has been published that shows how important it is health systems start getting ready to exist in a world with climate change, with biodiversity loss.”

In what is likely to come as a more surprising finding, the researchers also found that urbanization decreased the risk of infectious disease.

The new analysis, which was published in Nature on Wednesday, focused on five “global change drivers” that are altering ecosystems across the planet: biodiversity change, climate change, chemical pollution, the introduction of nonnative species and habitat loss or change.

The researchers compiled data from scientific papers that examined how at least one of these factors affected various infectious-disease outcomes, such as severity or prevalence. The final data set included nearly 3,000 observations on disease risks for humans, animals and plants on every continent except for Antarctica.

The researchers found that, across the board, four of the five trends they studied — biodiversity change, the introduction of new species, climate change and chemical pollution — tended to increase disease risk.

“It means that we’re likely picking up general biological patterns,” said Jason Rohr, an infectious disease ecologist at the University of Notre Dame and senior author of the study. “It suggests that there are similar sorts of mechanisms and processes that are likely occurring in plants, animals and humans.”

The loss of biodiversity played an especially large role in driving up disease risk, the researchers found. Many scientists have posited that biodiversity can protect against disease through a phenomenon known as the dilution effect.

The theory holds that parasites and pathogens, which rely on having abundant hosts in order to survive, will evolve to favor species that are common, rather than those that are rare, Dr. Rohr said. And as biodiversity declines, rare species tend to disappear first. “That means that the species that remain are the competent ones, the ones that are really good at transmitting disease,” he said.

Lyme disease is one oft-cited example. White-footed mice, which are the primary reservoir for the disease, have become more dominant on the landscape, as other rarer mammals have disappeared, Dr. Rohr said. That shift may partly explain why Lyme disease rates have risen in the United States. (The extent to which the dilution effect contributes to Lyme disease risk has been the subject of debate, and other factors, including climate change, are likely to be at play as well.)

Other environmental changes could amplify disease risks in a wide variety of ways. For instance, introduced species can bring new pathogens with them, and chemical pollution can stress organisms’ immune systems. Climate change can alter animal movements and habitats, bringing new species into contact and allowing them to swap pathogens .

Notably, the fifth global environmental change that the researchers studied — habitat loss or change — appeared to reduce disease risk. At first glance, the findings might appear to be at odds with previous studies, which have shown that deforestation can increase the risk of diseases ranging from malaria to Ebola. But the overall trend toward reduced risk was driven by one specific type of habitat change: increasing urbanization.

The reason may be that urban areas often have better sanitation and public health infrastructure than rural ones — or simply because there are fewer plants and animals to serve as disease hosts in urban areas. The lack of plant and animal life is “not a good thing,” Dr. Carlson said. “And it also doesn’t mean that the animals that are in the cities are healthier.”

And the new study does not negate the idea that forest loss can fuel disease; instead, deforestation increases risk in some circumstances and reduces it in others, Dr. Rohr said.

Indeed, although this kind of meta-analysis is valuable for revealing broad patterns, it can obscure some of the nuances and exceptions that are important for managing specific diseases and ecosystems, Dr. Carlson noted.

Moreover, most of the studies included in the analysis examined just a single global change drive. But, in the real world, organisms are contending with many of these stressors simultaneously. “The next step is to better understand the connections among them,” Dr. Rohr said.

Emily Anthes is a science reporter, writing primarily about animal health and science. She also covered the coronavirus pandemic. More about Emily Anthes

Explore the Animal Kingdom