ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Is the student-centered learning style more effective than the teacher-student double-centered learning style in improving reading performance.

- 1 Department of Social and Behavioural Sciences, City University of Hong Kong, Kowloon, Hong Kong

- 2 Department of Curriculum and Instruction, The Education University of Hong Kong, Tai Po, Hong Kong

- 3 Faculty of Business, Law and Art, Southampton Business School, University of Southampton, Southampton, United Kingdom

- 4 Faculty of Education and Science, Jiaying University, Meizhou, China

Appropriate learning styles enhance the academic performance of students. This research compares and contrasts the popular effect of teacher-student double centered learning style (TSDCLS) and student-centered learning style (SCLS) on one’s reading, including reading comprehension, inference, main idea abstraction, and reading anxiety. One hundred and fifty one students in grade 4 from three groups (two experimental groups and one control group) participated in the experiment with 18 weeks’ reading comprehension training. The results showed that, first, both learning styles contributed to students’ reading comprehension, inference, main idea abstraction, and reading anxiety. Second, the TSDCLS contributed more to reading anxiety, and the SCLS contributed more to reading comprehension. Both learning styles had similar effects on inference and main idea abstraction. From the correlation test, excluding the correlation between SCLS and reading anxiety which was not significant, all other effects were significant. These findings are discussed along with implications and ideas for future research.

Introduction

Reading comprehension is an ability to gain meaning from the given text through the interaction between word decoding process and background knowledge application ( Cain et al., 2004 ; Ahmed et al., 2016 ). Reading comprehension has received considerable attention as the ultimate goal for reading is to draw a mental image from the given text. The schema in linguistic learning (referred to herein as linguistic schema ) plays a fundamental role in reading comprehension through literacy knowledge search in readers’ knowledge bases. To be more specific, in reading comprehension, linguistic schema works on the reading process through cue retrieval (e.g., vocabulary meaning) from the mental knowledge structure to interpret and integrate selected new information into the existing knowledge base (e.g., Nassaji, 2002 ). In reading comprehension, besides general comprehension ability, the other relevant abilities (e.g., inference and main idea abstract) and reading affect (e.g., reading anxiety) also determine the process of reading comprehension ( Rai et al., 2015 ; Silva and Cain, 2015 ; Stanley et al., 2018 ).

Previous studies have confirmed that appropriate teaching-learning style enhances students’ academic performance ( Komarraju et al., 2011 ; Huang et al., 2012 ), while there remains a general paucity of research comparing the different effects of each teaching-learning style on reading comprehension and the determining factors. Specifically, the effect of different teaching-learning styles on reading performance is a long way from being known. The correlations between different teaching-learning styles and reading factors (e.g., reading comprehension, reading anxiety, inference, and main idea) await discovery.

Literature Review

Linguistic schema on reading process.

Linguistic schema is an individual knowledge base for the reading comprehension process which activates background knowledge from schemata to support reading problem-solving ( Freebody and Anderson, 1983 ; Hebert et al., 2016 ). It mainly works on cognitive reading abilities and cognitive affect ( Cain et al., 2004 ; Sorrell and Brown, 2018 ). As for cognitive reading abilities, past studies showed that linguistic schema enhances readers’ first language (L1) reading comprehension abilities (e.g., inference, main idea abstraction) through meaning-based interpretations of the printed text (e.g., Cain et al., 2004 ).

Teaching Style

Teaching style refers to a belief which teachers used in pedagogy explanation and knowledge transfer to students ( Grasha and Yangarber-Hicks, 2000 ; Hsieh et al., 2011 ; Prescott, 2014 ). Under the guidance of self-determination theory ( Ryan and Deci, 2000 ), teachers’ teaching performance was impacted by competence, autonomy, and relatedness. Extensive studies showed autonomy-supportive and controlling practices directly impacted teachers’ teaching style development (e.g., Balaguer et al., 2018 ; Codina et al., 2018 ; Collie et al., 2019 ). Both autonomy-supportive and controlling practices reflected teachers’ awareness of supporting students’ empowerment on knowledge acquisition, controlling action on feeling, and thinking. Therefore, the current study selected the autonomy-supportive and controlling practices as the framework for teaching style investigation. Moreover, extensive evidences showed teachers’ teaching style usually worked with students’ learning style, if teaching style matched learning style, students would achieve the best learning results than those whose teaching-learning style did not match due to decreased students’ academic anxiety, learning motivation, and task inattentiveness ( Naimie et al., 2010 ; Chen et al., 2011 ; Bartholomew et al., 2018 ). In general, based on self-determination theory ( Ryan and Deci, 2000 ), teaching style could be further divided into teacher-centered style and learner-centered style ( Edmunds et al., 2008 ; Tessier et al., 2010 ; Haerens et al., 2015 ). Teacher-centered style refers to a teachers’ domain teaching approach in which the knowledge transfer was from the teacher to students directly; teacher played the decision-maker role, which determined learning process and designed the learning environment ( Opdenakker and Van Damme, 2006 ; Kahl and Venette, 2010 ; Vasileva-Stojanovska et al., 2015 ). The learner-centered style reflected students who had high involvement in knowledge acquisition with which the teacher played a facilitative role ( Özyurt and Özyurt, 2015 ; Rogowsky et al., 2015 ; Bernard et al., 2017 ). Past studies showed learner-centered style had advantages in increasing students’ deep understanding on knowledge acquisition ( Lin, 2015 ; Hanewicz et al., 2017 ; Yamagata, 2018 ), learning motivation ( McCombs et al., 2008 ; Polly and Hannafin, 2010 ), and improved critical thinking abilities ( Ernst and Monroe, 2004 ; Cornelius-White, 2007 ; Şendağ and Odabaşı, 2009 ). In addition, past studies mainly investigated the effect of teaching-learning style in math, science, or engineering, a few studies examined the effect in the reading field. Therefore, the current study investigated the learner-centered style and investigated the effect on reading factors.

Impact of Different Learning Styles on Reading Comprehension

Two main learner-centered styles drew great attention in the existing literature but still attract debate in the context of reading comprehension: SCLS and TSDCLS ( Souvignier and Mokhlesgerami, 2006 ; Rance-Roney, 2010 ; Law, 2014 ). Past studies showed that the differences between two learning styles on academic performance mainly come from two factors: teachers’ instruction and students’ self-regulated learning. Although these two factors work[ed] cooperatively, they still reflect two distinct bodies in the learning process.

Teachers’ Instruction

Teachers’ instruction worked effectively on students’ reading comprehension through explicit guidance on key information or the application of reading strategies ( Rance-Roney, 2010 ; Law, 2014 ). Some researchers claimed that teachers’ direct guidance (i.e., providing explicit instructions on selected reading task) were more effective than implicit instruction (i.e., pure interactive discussion between students) ( Dole et al., 1991 , 1996 ). For example, Dole et al. (1996) reported that students with direct guidance from the teacher performed better than those who undertook SCLS in narrative and expository texts.

Students’ Self-Regulated Learning

There are two key factors to initiate and maintain readers’ self-learning; cognitive control and motivational control ( Boekaerts, 1999 ). On the one hand, researchers claimed that the provision of external structures to control cognitive and motivational regulation was effective in enhancing reading abilities during text comprehension (e.g., Boekaerts, 1999 ; Pintrich, 2000 ). For example, Souvignier and Mokhlesgerami (2006) reported that students under motivation control performed better in reading comprehension strategy application than the control group did. In a similar vein, previous studies identified that cognitive control enhanced readers’ performance in main idea abstraction and comprehension strategies’ application ( Lau, 2012 ; Lau and Chen, 2013 ). On the other hand, many researchers showed that the explicit instruction in self-regulated learning may reduce the beneficial effects on students’ learning (e.g., Dignath et al., 2008 ; Dignath and Büttner, 2008 ). In two meta-analyses, Dignath et al. (2008) found that risk may be involved when teachers tailor self-regulated instruction; this is because teachers may over-control readers’ cognitive process and motivational process ( Waeytens et al., 2002 ), and such intervention may reduce the effectiveness of self-regulated learning on students’ learning behaviors. There is no doubt that learner effect and teacher effect are both important in teaching-learning cycles. However, which learning style is more effective in enhancing reading comprehension and reading factors remains to be identified.

Reading Anxiety

In the case of cognitive affect response, reading anxiety mainly reflects the emotional experience in reading ( Saito et al., 1999 ). Reading anxiety refers to a distinct complex of self-perceptions, behaviors, and affective feelings related to text reading activity ( Saito et al., 1999 ; Lu and Liu, 2015 ). Reading anxiety has a close relationship with reading comprehension. High reading anxiety inhibits reading performance and passage recall ( Sellers, 2000 ; Rai et al., 2015 ). Different learning styles bring different learning experiences for the readers. For example, the teacher-centered learning style may leave learners feeling bored or disinterested in class ( Schaefer and Zygmont, 2003 ; Lee and Hannafin, 2016 ). However, the effect of the learner-centered style (e.g., TSDCLS and SCLS) on reading anxiety is still unclear. Therefore, research on which learning style is better to reduce students’ reading anxiety is timely.

Main Idea Abstraction

Main idea abstraction refers to an ability to abstract the mental message from the given test, which is the ultimate goal of reading comprehension. The main idea has a close relationship with reading performance, which in turn determines the reading process (e.g., reading speed) and how the readers can abstract/select the proper reading strategies from their knowledge bases ( Hebert et al., 2018 ; Stevens et al., 2019 ). Previous studies confirmed that main idea abstraction is a key factor of executive function in reading comprehension. Usually, a higher main idea abstraction ability predicts higher reading performance. Learning style is essentially a habit that is adopted during the reading learning process, how readers’ learning style impacts the ability to develop the main idea remains unknown.

Inference is a key ability in reading, which reflects readers’ ability to take in vocabulary knowledge and grammar knowledge in sentence reading comprehension ( Cain et al., 2004 , 2004 ). Inference is another important ability in reading executive function. Past researchers tried to improve readers’ inference ability to enhance reading comprehension (e.g., Bensoussan and Laufer, 1984 ), and studies confirmed that self-internal reading factors (e.g., vocabulary knowledge, reading strategies) predicted inference ( Cromley and Azevedo, 2007 ; Ahmed et al., 2016 ). Learning style, as an external factor of learning, determined the learning process; however, it remains to be established whether the learning style has a positive impact on inference.

The Current Study

There are two main aims of this research. The first is to compare and contrast the effectiveness of both SCLS and TSDCLS in enhancing readers’ reading experience, which includes overall reading comprehension performance, specific reading abilities (e.g., main idea abstraction and inference), and reading anxiety. Second, the research examines the relationship between each learning style as well as reading comprehension, inference ability, main idea, and reading anxiety.

Participants

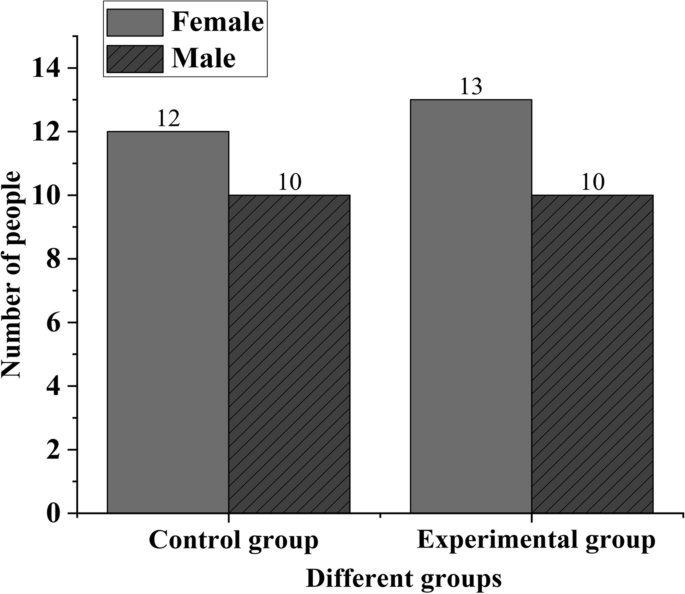

Participants for the research were randomly selected from three Grade 4 classes. Of these classes, all students come from low socio-economic status families and the three selected schools were in suburban districts in China. In previous learning, all students’ learning curricula followed standard instructions designed and approved by China’s Ministry of Education. All students were randomly divided into different classes after they finished the registration procedure for the school program. Consent was obtained from students and their parents before the formers’ participation in the research. No participants have received any form of reading ability training. In total, 151 students with no special education needs and from low socio-economic status families were randomly recruited and randomly allocated to three groups. About 49 (25 boys and 24 girls, mean age = 10.12 years old, SD age = 0.61) participated in the TSDCLS group, and 52 students (26 boys and 26 girls, mean age = 9.98 years old, SD age = 0.79) participated in SCLS group. Finally, 50 students (28 boys and 22 girls, mean age = 9.82 years old, SD age = 0.67) formed the control group.

To examine the effectiveness of SCLS and TSDCLS in enhancing reading comprehension and reading factors, inference ability and main idea abstraction ability from the normal reading comprehension (NRC); NRC tests were used to measure students’ reading performance in primary school. The measurement details are listed in the following paragraph.

Normal Reading Comprehension

We examined students’ NRC reading abilities through three selected narrative passages (version 2015, version 2016, and version 2017), which were widely used, well-established, and with both high reliability (Cronbach’s α -coefficients yielded 0.90) and validity translation tests, which were applied to measure the Chinese children’s NRC reading ability in primary school from 2015 to 2017 ( Xia, 2013 ; Zhang, 2018 ). Each reading comprehension test had similar difficulty indicators (e.g., correct answer rate in all samples around China was 60%), and the maximum score for each reading battery was 30 with 12 items. Three items for the main idea had a maximum score of six, and four items (e.g., what is the target word meaning in the passage) for inference had the total maximum score of eight (two scores for each). One item for the detailed search was awarded a score of four, and the remaining four items had a total score of 12. The length of each passage was around 900 words, a total of around 2,700 words for all three reading comprehension tests. Version 2015 reading comprehension test was used for pre-test, version 2016 reading comprehension test was used for post-test, and version 2017 reading comprehension test was used for the delayed test.

Students’ reading anxiety was assessed by the Chinese Language Reading Anxiety Scale (CLRAS), which was developed by Zhao (2013) ; the original scale was developed by Saito et al. (1999) . The CLRAS contains 20 items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “ strongly disagree ” to “ strongly agree .” An example item is: “When reading a Chinese passage, I get nervous and confused when I don’t understand each word.” The scale assessed factors that may contribute to reading anxiety and considered students’ perceptions of the difficulties they encounter. A high score would indicate high levels of anxiety. The maximum mean score of the scale was 5 and Cronbach’s α for the scale was 0.90.

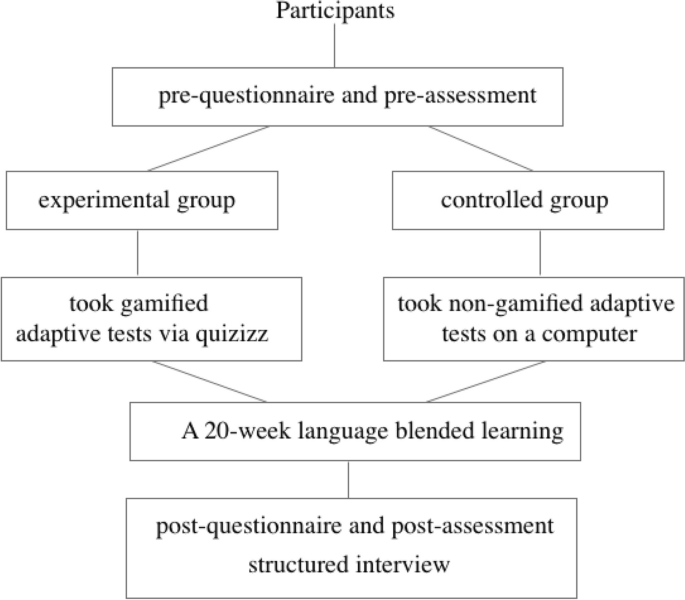

Research Design

We applied a quasi-experimental design to measure students’ performance in pretest, post-test, and lasting effect (hereafter, we called delayed post-test in the current study). First, we collected the consent forms from potential students and randomly selected students from three classes as our participants. Second, we randomly assigned a research design to each class. Random allocation resulted in 49 students in the TSDCLS group and 52 students in the SCLS group. The remaining 50 students were assigned to the control group. The control group received regular classroom instruction during the reading comprehension program training. The three classes were taught by one of the training tutors, who is also working as a part-time teacher in that school. All expectation teaching outcomes followed the curriculum outline design, which was approved by the Ministry of Education in China for both primary school and secondary school learning periods. Third, to control for irrelevant learning effects (e.g., NRC familiarity learning effect), we selected classical reading comprehension (CRC) for the study. The content structure of CRC is similar to straightforward poems, short works, and fresh but with lively literacy information ( Wang, 2016 ). Specifically, all CRC vocabulary has at least two different meanings: phonetic radical meaning and semantic radical meaning ( Shu and Anderson, 1997 ; Chen et al., 2016 ). Past studies in Chinese reading comprehension confirmed that CRC was a useful predictor of reading performance ( Shu and Anderson, 1997 ; Wang, 2017 ). For CRC learning materials, normally, students begin to learn CRC at grade 5 of primary school, which means that, at the time of this study, participants had not done any CRC tasks in normal school test or school learning. The difference between CRC and NRC is that most CRC texts are narrative passages, the average length of each sentence of NRC is longer than that of CRC, and the meaning of each character is unique in NRC. Both TSDCLS and SCLS students were required to learn 21 CRC passages from the textbooks. The total training duration was from late February to late June (18 weeks).

In terms of reading performance examination, the pre-test was held in late February. Before the experiment started, all participants received reading comprehension tests (2015 version) and questionnaires regarding reading anxiety and inference. Regarding the post-test, the 2016 version of the reading comprehension test was used, with the same reading anxiety survey and inference tests. At the delayed post-test, the 2017 version of the reading comprehension test was used, and with the same reading anxiety survey and inference tests.

Training Materials

Training materials comprise three components. Component 1 is a vocabulary list that listed all vocabulary meanings in CRC with higher frequency and the vocabulary that students were required to know from the textbook teaching guidance. For example, “举(ju3)”: meaning 1, “并列 (equal effect),” “举案齐眉 (husband and wife treat each other with respect)”; and meaning 2, “全 (all),” “举国同庆(Nationwide celebration).” Component 2 has 21 passages from the school textbook, which the students were required to learn during the training program. All learning passages are narrative passages, telling a story. For example, “邹忌讽齐王纳谏 (Zou Ji’s Advice to the King).” In each passage, a modern language translation in direct translation style is given under each sentence, which means that we provided each character’s meaning in the second line of the given sentence. In addition, we highlighted the points of difficulty (e.g., grammatical knowledge and vocabulary knowledge) in the initial instructions guide. Component 3 is the after-school exercise, where all items were selected from the textbook. The exercise included main idea abstraction, inference sentence meaning, and detailed information search.

Training Procedure

The major difference between the TSDCLS group and SCLS group is that those students in TSDCLS had more interaction with teachers, which followed the guidance of the TSDCLS ( Rogowsky et al., 2015 ). That is, in each lesson, teachers and students learn the given materials together. The teacher tries to get interaction with students on each kind of knowledge transfer. Specifically, the interaction between teacher and students mainly reflects in heuristic problem solving and knowledge recall through exercise, the average frequency of the interaction on each knowledge item was over four times.

For the SCLS group, at the beginning of each class, the teacher reminded students to read the guidance instructions carefully first and then asked students to learn the given passage, which was followed by the SCLS ( Dignath et al., 2008 ). The teacher would only instruct students if students encountered difficulties and raised their hands. If more than three students had the same question, the teacher explained the knowledge being sought. In each training session, the teacher started class with encouragement on students’ self-learning, which mainly used self-questioning, self-regulated learning, and self-problem solving. The average interaction frequency during the learning period was one time only for time instruction and asked students to move their eyes to exercises to continue learning. All learning materials in the TSDCLS and SCLS group were the same and included the direct translation in modern language, the difficult points, the characters’ different meanings recall notice, grammatical function, and so on.

For the control group, except the material of guidance instructions, all three components’ training materials were provided to control group’s students at the same learning period.

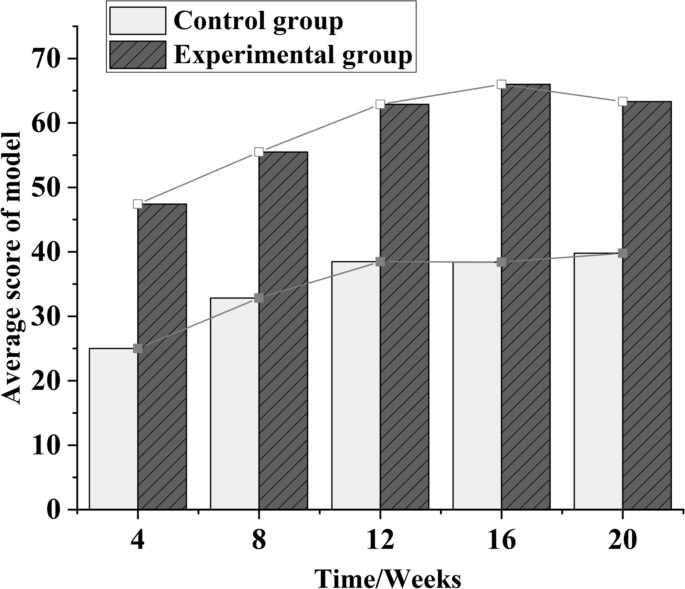

Descriptive Analysis and Comparison Reading Performance From Three Groups

For scores calculation, regarding the main idea test, we used items’ scores from the NRC. Then, we compared each reading factor performance in pre-test, post-test, and delayed post-test contexts.

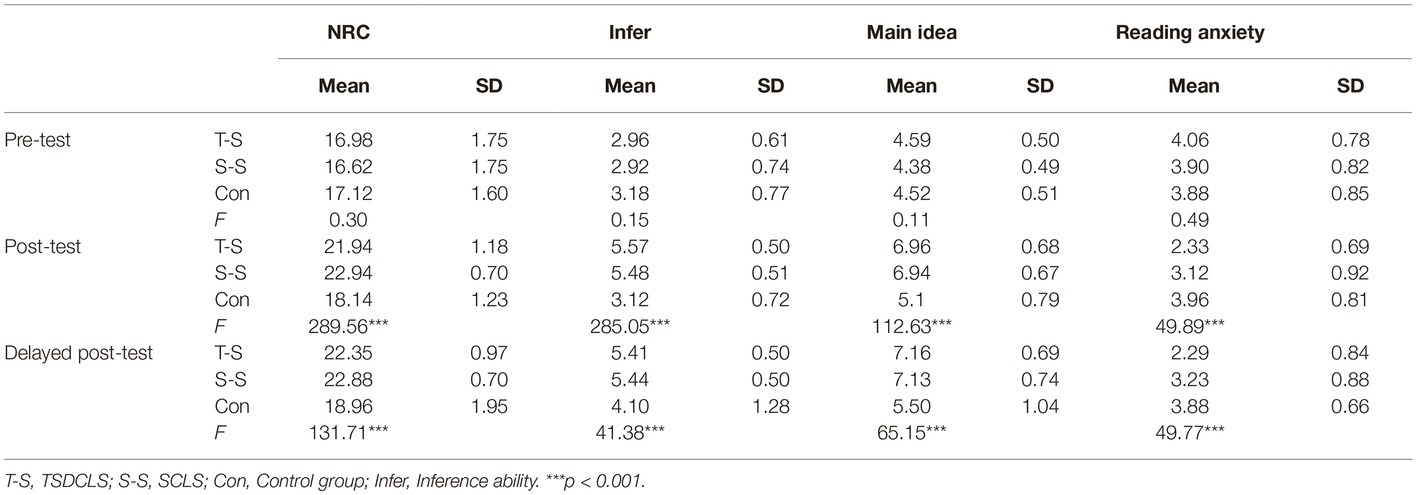

Repeated ANOVA and four-way ANOVA were used for data analysis. From Table 1 , at pre-test, all three groups’ students achieved similar performance in NRC ( F = 0.30, p > 0.05), inference ( F = 0.15, p > 0.05), main idea abstraction ( F = 0.11, p > 0.05), and reading anxiety ( F = 0.49, p > 0.05). At post-test, three groups students performed significant differences in NRC ( F = 289.56, p < 0.001), inference ( F = 285.05, p < 0.001), main idea abstraction ( F = 112.63, p < 0.001), and reading anxiety ( F = 49.89, p < 0.001). Specifically, regarding NRC, SCLS students performed significant higher scores than TSDCLS students (Mean difference = 1.00, p < 0.001), TSDCLS students performed significant higher score than control group (Mean difference = 3.80, p < 0.001). Regarding inference, TSDCLS students had similar scores with SCLS students (Mean difference = 0.09, p > 0.05), control group students had significant lower score with TSDCLS (Mean difference = 2.45, p < 0.001) and SCLS students (Mean difference = 2.36, p < 0.001). Regarding main idea abstraction, TSDCLS students performed similar score with SCLS students (Mean difference = 0.02, p > 0.05), control group students performed significant lower score with TSDCLS students (Mean difference = 1.86, p < 0.001) and SCLS students (Mean difference = 1.84, p < 0.001). Regarding reading anxiety, TSDCLS students had significant lower score than SCLS students (Mean difference = −0.79, p < 0.001), SCLS students performed significant lower score than control group students (Mean difference = −0.85, p < 0.001).

Table 1 . Comparison means and standard deviations for three rounds of data collection from three different groups.

At delayed post-test, three group students performed significant differences in NRC ( F = 131.71, p < 0.001), inference ( F = 41.38, p < 0.001), main idea abstraction ( F = 65.15, p < 0.001), and reading anxiety ( F = 49.77, p < 0.001). Specifically, SCLS students performed significant higher score than TSDCLS students in NRC (Mean difference = 0.54, p < 0.05), TSDCLS students performed significant higher score than control group students (Mean difference = 3.39, p < 0.001). Regarding inference, TSDCLS students had similar score with SCLS students (Mean difference = 0.04, p > 0.05), control group students had significant lower score than TSDCLS students (Mean difference = 1.31, p < 0.001) and SCLS students (Mean difference = 1.34, p < 0.001). Regarding main idea abstraction, TSDCLS students got similar score with SCLS students (Mean difference = 0.03, p > 0.05). Control group students had significant lower score with TSDCLS students (Mean difference = 1.66, p < 0.001) and SCLS students (Mean difference = 1.64, p < 0.001). Regarding reading anxiety, TSDCLS students had significant lower reading anxiety than SCLS students (Mean difference = −0.95, p < 0.001), SCLS students had significant lower reading anxiety than control group students (Mean difference = −0.85, p < 0.001).

The Effect of Both Teacher-Student Double Centered Learning Style and Student-Centered Learning Style on Reading and Reading Factors

To further explore the effect of both TSDCLS and SCLS on reading and reading factors, we created two sub-variables for learning styles and examined the effect on reading comprehension and reading factors.

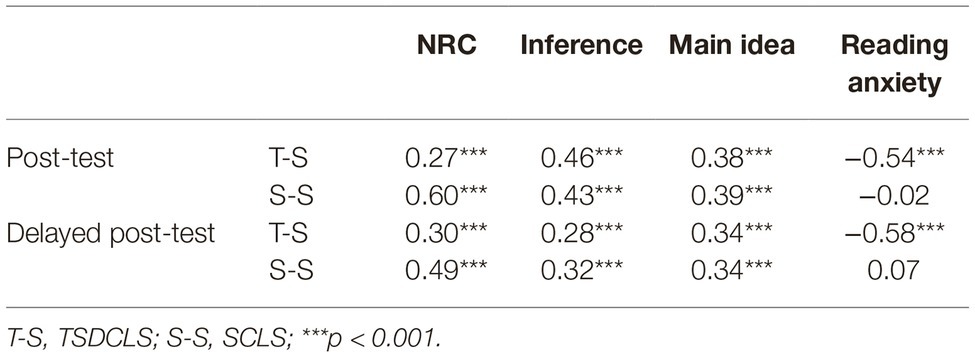

From Table 2 , in both the post-test and delayed post-test, the TSDCLS had significant positive correlations with NRC ( r pre-test = 0.27, p < 0.001; r post-test = 0.30, p < 0.001), inference ( r pre-test = 0.46, p < 0.001; r post-test = 0.28, p < 0.001), main idea ( r pre-test = 0.38, p < 0.001; r post-test = 0.34, p < 0.001), and reading anxiety ( r pre-test = −0.54, p < 0.001; r post-test = −0.58, p < 0.001), while for the SCLS, the SCLS had significant positive correlations with NRC ( r pre-test = 0.60, p < 0.001; r post-test = 0.49, p < 0.001), inference ( r pre-test = 0.43, p < 0.001; r post-test = 0.32, p < 0.001), and main idea ( r pre-test = 0.39, p < 0.001; r post-test = 0.34, p < 0.001), but the correlation between SCLS and reading anxiety was not significant ( r pre-test = −0.02, p > 0.05; r post-test = −0.07, p > 0.05).

Table 2 . The effect of learning styles on reading and reading factors.

We examined the effect of both TSDCLS and SCLS on reading comprehension and relevant reading factors (reading anxiety, main idea abstraction, and inference). The results showed that, firstly, the two experimental groups performed better than the control group in reading comprehension and three selected reading factors. Between TSDCLS and SCLS, the TSDCLS performed better in reading anxiety than the SCLS. However, the SCLS performed better in NRC than the TSDCLS. As for inference ability and main idea abstraction, two experimental groups had similar performance. Secondly, the TSDCLS had a significant positive correlation with reading comprehension and three selected reading factors, in which the results were consistent with the comparison test. However, the SCLS did not have a significant correlation with reading anxiety. We discussed this phenomenon later.

The Advantage of Teacher-Student Double Centered Learning Style

Reading anxiety depends on an individual’s perceptions of a threatening situation and their abilities in handling this threat ( Frenzel et al., 2016 ; Marsh et al., 2017 ). Students following the TSDCLS performed with less reading anxiety than those using the SCLS, which is consistent with those studies that indicated the positive effect of teachers’ support on students’ reading anxiety ( Pratt and Savoy-Levine, 1998 ). Firstly, as Beck’s team (1985) suggested, a lower level of reading anxiety may come from less threatening learning situations, which means that, in the TSDCLS, the teacher’s guidance could be regarded as supportive information for assisting learning. Second, the TSDCLS provides a clear teacher-directed learning track, which could facilitate students to coordinate a goal-directed strategy, thus minimizing threatening emotions and maximizing safety ( Beck, 1985 ). In the current study, in the TSDCLS, the teacher could guide students on how to learn CRC effectively and this teacher-directed learning track reduced students’ threatening experience on CRC learning. In addition, dialog interaction encourages students to solve reading questions at the time they occur, and teachers could immediately provide feedback. Third, the interactive situation may create a decentralized pattern of power, which may encourage students to have more incentive to engage in, and confidence in, knowledge search ( Mezirow, 2000 ). Thus, the threatening emotions might be eased and the teacher’s support may gradually boost their safety awareness.

The Advantage of the Student-Centered Learning Style

Better performance in the NRC test could be explained by two reasons. Firstly, the depth of processing theory shows that deeper encoding facilitates better memory retrieval compared with shallow encoding (e.g., Craik and Lockhart, 1972 ). In the current study, in the SCLS, with less teachers’ guidance, students were forced to make more effort to attain deeper and more levels of elaborating and associating the reading materials with their knowledge retrieval during training, which means they have more comprehensive understanding of reading knowledge (e.g., sentence structure, vocabulary meaning). In this case, they find it easier to retrieve more needed knowledge on a NRC task due to deeper encoding of memory cues. For example, when students need to accomplish a NRC task, they may recall target knowledge (e.g., phrases’ meaning) faster than students, who are exposed to the TSDCLS. Secondly, in the SCLS, students have more problem-solving opportunities to think about how to deal with reading tasks effectively, which means they may cultivate more useful reading strategies for reading comprehension practice. Specifically, with guided questions, students might be more likely to engage in retroactive elaborating on and encoding of learning materials where they tend to frequently regulate their learning strategies to use previously learned similar knowledge to tackle the problems at hand.

Similar Effect Between Teacher-Student Double Centered Learning Style and Student-Centered Learning Style

The findings of similar abilities in main idea abstraction in both TSDCLS and SCLS groups were partially consistent with previous studies (e.g., Stoeger et al., 2014 ), but contrasting with the findings of Mason’s (2004) study, which proved the preference of the SCLS over the TSDCLS in teaching main idea abilities. The equal effect of finding main ideas observed in the current study might be related to the involvement of similar probes (i.e. verbal and written prompts) in the TSDCLS and the SCLS, respectively. Morrow (1985) managed to establish that students’ abilities in retelling stories were facilitated when they were guided with verbal prompts. The explicit guidance in both TSDCLS and SCLS groups may facilitate students to pick out relevant information in supporting the summarization. This result informed the ability of main idea abstraction could be learned through the appropriate track of guidance, no matter the teacher-directed learning or students’ self-learning based on explicit instruction guidance. Under the correct track of guidance, students could increase the ability of main idea abstraction.

As for the equal effect of inferences in both groups, according to the direct and inferential mediation (DIME) model, background knowledge is a significant component for enacting inferences. Prior studies also proved that different kinds of background knowledge about the texts resulted in higher inference scores (e.g., Vidal-Abarca et al., 2000 ). In the current study, in the beginning, from the test and survey, students in both TSDCLS and SCLS groups had similar background knowledge in NRC. As a result, there might be a possibility that similar storage of background knowledge has equal effects on their inferencing abilities in both TSDCLS and SCLS groups. That is to say, the amount of background knowledge acquisition on reading comprehension was similar between TSDCLS and SCLS through training materials.

Other Effects From the Student-Centered Learning Style on Reading Anxiety

Results showed that the SCLS did not have a significant correlation with reading anxiety. However, the reading anxiety score decreased significantly at post-test and delayed post-test. The reason may be due to the students’ feelings of freedom when exposed to SCLS. In particular, during the CRC training, the reader increased other abilities, which decreased threatening feelings when they faced reading comprehension. The reason why the correlation between SCLS and reading anxiety was insignificant might be the compensation or interaction effect with other reading comprehension factors (e.g., word reading and metalinguistic knowledge), resulting in the insignificant correlation.

Limitations and Future Direction

Several limitations of this study should be stated. First, due to the cognitive ability of primary school students, we only measured the effect of learning style on narrative reading comprehension, while other types of reading text such as descriptive reading comprehension and argumentative reading comprehension need further exploration. Second, the current study examined the TSDCLS and SCLS, which are popular nowadays in teaching, while for the teacher-centered learning style, the effect may be different from the learner-centered style (e.g., TSDCLS and SCLS). Third, to the best of our knowledge, there is no standardized and independent scale for inference ability and main idea abstraction measurement. Therefore, for future studies, there is great potential to design a standardized research scale. In addition, this study only investigated students’ general reading anxiety. Previous studies showed that anxiety could be categorized into “trait” and “state” anxiety (e.g., Nelson et al., 2015 ; Waechter and Stolz, 2015 ). Different types of anxiety have different effects on individuals’ executive function (e.g., working memory, inference, and main idea); thus leading to different reading performance efficiencies (e.g., Hadwin et al., 2005 ). Therefore, it is promising to develop scales eliciting different types of reading anxiety. Next, the correlation between SCLS and reading anxiety was not significant, the potential compensation or interaction effect with other reading factors requires further investigation. The factors that decreased reading anxiety are still unknown. Lastly, the current study only investigated two perspectives’ (autonomy-supportive and controlling practices) effects on teaching-learning style; for other perspectives’, effects such as competences and relatedness should be further explored in the future.

Implications

The current study contributes to the correlation between TSDCLS and SCLS and reading comprehension from cognitive processing and affect. First, the SCLS with questions-probing learning materials could further strengthen reading ability development in previously-learned knowledge with some amount of learning foundation. The SCLS could trigger students’ metacognition based on the depth of cognitive processing. This result informed that SCLS increased students’ depth understanding of learning materials, based on the depth of processing model suggestions, more interaction between memory and knowledge acquisition resulted in higher academic performance. Second, it might be that teachers’ guidance in the TSDCLS could generate “safety signals,” thus easing students’ negative cognitive affect, such as decreased threatening feelings of reading anxiety. TSDCLS contributed more to students’ academic affective factors (e.g., reading anxiety) through interaction between teachers and students on problem-solving.

In conclusion, both TSDCLS and SCLS contribute to the development of reading comprehension performance and development of three selected reading factors (main idea abstract, inference, and reading anxiety). Specifically, TSDCLS contributes more in reading anxiety through reducing the threatening feeling, the SCLS leads to better performance in the reading comprehension task, and both learning styles have a similar effect on inference and main idea abstraction. The TSDCLS shows a significant correlation with reading comprehension, inference, main idea abstraction, and reading anxiety, the SCLS has a significant correlation with reading comprehension, inference, and main idea abstraction, and the correlation between SCLS and reading anxiety was not significant, which needs further exploration on the compensation or interaction effect between SCLS and other reading factors. Results implicated more interaction between teacher and students on knowledge acquisition and problem-solving could decrease the threatening situation feeling which contributes more to students’ affective factors development. SCLS contributed more to students’ knowledge of deep understanding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Jiaying Social Science Research Ethics Committee. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

YD and SW drafted the whole paper and did data-analysis. WW and SP provided the comments and helped to revise the draft.

This paper was supported by the Faculty of Social Science of Meizhou City for 2019 project. Reference Number: mz-ybxm-2019018.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ahmed, Y., Francis, D. J., York, M., Fletcher, J. M., Barnes, M., and Kulesz, P. (2016). Validation of the direct and inferential mediation (DIME) model of reading comprehension in grades 7 through 12. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 44, 68–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2016.02.002

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Balaguer, I., Castillo, I., Cuevas, R., and Atienza, F. (2018). The importance of coaches’ autonomy support in the leisure experience and well-being of young footballers. Front. Psychol. 9:840. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00840

Bartholomew, K. J., Ntoumanis, N., Mouratidis, A., Katartzi, E., Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C., and Vlachopoulos, S. (2018). Beware of your teaching style: a school-year long investigation of controlling teaching and student motivational experiences. Learn. Instr. 53, 50–63. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2017.07.006

Beck, A. T. (1985). “Theoretical perspectives on clinical anxiety” in Anxiety and the anxiety disorders . eds. A. H. Tuma and D. Maser (Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum Press), 183–196.

Google Scholar

Bensoussan, M., and Laufer, B. (1984). Lexical guessing in context in EFL reading comprehension. J. Res. Read. 7, 15–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9817.1984.tb00252.x

Bernard, J., Chang, T. W., Popescu, E., and Graf, S. (2017). Learning style identifier: improving the precision of learning style identification through computational intelligence algorithms. Expert Syst. Appl. 75, 94–108. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2017.01.021

Boekaerts, M. (1999). Self-regulated learning: where we are today. Int J. Educ. Res. 31, 445–457. doi: 10.1016/S0883-0355(99)00014-2

Cain, K., Oakhill, J., and Bryant, P. (2004). Children’s reading comprehension ability: concurrent prediction by working memory, verbal ability, and component skills. J. Educ. Psychol. 96, 31–42. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.96.1.31

Cain, K., Oakhill, J., and Lemmon, K. (2004). Individual differences in the inference of word meanings from context: the influence of reading comprehension, vocabulary knowledge, and memory capacity. J. Educ. Psychol. 96, 671–681. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.96.4.671

Chen, N. S., Wei, C. W., and Liu, C. C. (2011). Effects of matching teaching strategy to thinking style on learner’s quality of reflection in an online learning environment. Comput. Educ. 56, 53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2010.08.021

Chen, Q., Zhang, J., Xu, X., Scheepers, C., Yang, Y., and Tanenhaus, M. K. (2016). Prosodic expectations in silent reading: ERP evidence from rhyme scheme and semantic congruence in classic Chinese poems. Cognition 154, 11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2016.05.007

Codina, N., Valenzuela, R., Pestana, J. V., and Gonzalez-Conde, J. (2018). Relations between student procrastination and teaching styles: autonomy-supportive and controlling. Front. Psychol. 9:809. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00809

Collie, R. J., Granziera, H., and Martin, A. J. (2019). Teachers’ motivational approach: links with students’ basic psychological need frustration, maladaptive engagement, and academic outcomes. Teach. Teach. Educ. 86, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2019.07.002

Cornelius-White, J. (2007). Learner-centered teacher-student relationships are effective: a meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 77, 113–143. doi: 10.3102/003465430298563

Craik, F. I., and Lockhart, R. S. (1972). Levels of processing: a framework for memory research. J. Verb Learn. Verb. Behav. 11, 671–684. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5371(72)80001-X

Cromley, J. G., and Azevedo, R. (2007). Testing and refining the direct and inferential mediation model of reading comprehension. J. Educ. Psychol. 99, 311–325. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.99.2.311

Dignath, C., Buettner, G., and Langfeldt, H. P. (2008). How can primary school students learn self-regulated learning strategies most effectively: a meta-analysis on self-regulation training programmes. Educ. Res. Rev. 3, 101–129. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2008.02.003

Dignath, C., and Büttner, G. (2008). Components of fostering self-regulated learning among students. A meta-analysis on intervention studies at primary and secondary school level. Metacogn. Learn. 3, 231–264. doi: 10.1007/s11409-008-9029-x

Dole, J. A., Brown, K. J., and Trathen, W. (1996). The effects of strategy instruction on the comprehension performance of at-risk students. Read. Res. Q. 31, 62–88. doi: 10.1598/RRQ.31.1.4

Dole, J. A., Valencia, S. W., Greer, E. A., and Wardrop, J. L. (1991). Effects of two types of prereading instruction on the comprehension of narrative and expository text. Read. Res. Q. 26, 142–159. doi: 10.2307/747979

Edmunds, J., Ntoumanis, N., and Duda, J. L. (2008). Testing a self-determination theory-based teaching style intervention in the exercise domain. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 38, 375–388. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.463

Ernst, J., and Monroe, M. (2004). The effects of environment-based education on students’ critical thinking skills and disposition toward critical thinking. Environ. Educ. Res. 10, 507–522. doi: 10.1080/1350462042000291038

Freebody, P., and Anderson, R. C. (1983). Effects of vocabulary difficulty, text cohesion, and schema availability on reading comprehension. Read. Res. Q. 18, 277–294. doi: 10.2307/747389

Frenzel, A. C., Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Daniels, L. M., Durksen, T. L., Becker-Kurz, B., et al. (2016). Measuring teachers’ enjoyment, anger, and anxiety: the teacher emotions scales (TES). Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 46, 148–163. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2016.05.003

Grasha, A. F., and Yangarber-Hicks, N. (2000). Integrating teaching styles and learning styles with instructional technology. Coll. Teach. 48, 2–10. doi: 10.1080/87567550009596080

Hadwin, J. A., Brogan, J., and Stevenson, J. (2005). State anxiety and working memory in children: a test of processing efficiency theory. Educ. Psychol. 25, 379–393. doi: 10.1080/01443410500041607

Haerens, L., Aelterman, N., Vansteenkiste, M., Soenens, B., and Van Petegem, S. (2015). Do perceived autonomy-supportive and controlling teaching relate to physical education students’ motivational experiences through unique pathways? Distinguishing between the bright and dark side of motivation. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 16, 26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.08.013

Hanewicz, C., Platt, A., and Arendt, A. (2017). Creating a learner-centered teaching environment using student choice in assignments. Distance Educ. 38, 273–287. doi: 10.1080/01587919.2017.1369349

Hebert, M., Bohaty, J. J., Nelson, J. R., and Brown, J. (2016). The effects of text structure instruction on expository reading comprehension: a meta-analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. 108, 609–629. doi: 10.1037/edu0000082

Hebert, M., Zhang, X., and Parrila, R. (2018). Examining reading comprehension text and question answering time differences in university students with and without a history of reading difficulties. Ann. Dyslexia 68, 15–24. doi: 10.1007/s11881-017-0153-7

Hsieh, S. W., Jang, Y. R., Hwang, G. J., and Chen, N. S. (2011). Effects of teaching and learning styles on students’ reflection levels for ubiquitous learning. Comput. Educ. 57, 1194–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2011.01.004

Huang, E. Y., Lin, S. W., and Huang, T. K. (2012). What type of learning style leads to online participation in the mixed-mode e-learning environment? A study of software usage instruction. Comput. Educ. 58, 338–349. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2011.08.003

Kahl, D. H., and Venette, S. (2010). To lecture or let go: a comparative analysis of student speech outlines from teacher-centered and learner-centered classrooms. Commun. Teach. 24, 178–186. doi: 10.1080/17404622.2010.490232

Komarraju, M., Karau, S. J., Schmeck, R. R., and Avdic, A. (2011). The big five personality traits, learning styles, and academic achievement. Pers. Individ. Differ. 51, 472–477. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.04.019

Lau, K. L. (2012). Instructional practices and self-regulated learning in Chinese language classes. Educ. Psychol. 32, 427–450. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2012.674634

Lau, K. L., and Chen, X. B. (2013). Perception of reading instruction and self-regulated learning: a comparison between Chinese students in Hong Kong and Beijing. Instr. Sci. 41, 1083–1101. doi: 10.1007/s11251-013-9265-6

Law, Y. K. (2014). The role of structured cooperative learning groups for enhancing Chinese primary students’ reading comprehension. Educ. Psychol. 34, 470–494. doi: 10.1080/01443410.2013.860216

Lee, E., and Hannafin, M. J. (2016). A design framework for enhancing engagement in student-centered learning: own it, learn it, and share it. Educ. Tech. Res. Dev. 64, 707–734. doi: 10.1007/s11423-015-9422-5

Lin, M. H. (2015). Learner-centered blogging: a preliminary investigation of EFL student writers? Experience. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 18, 446–458. Available at: http://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=0&sid=d35f9b05-5340-4ebb-919d-5055795e7f49%40sdc-v-sessmgr02

Lu, Z., and Liu, M. (2015). An investigation of Chinese university EFL learner’s foreign language reading anxiety, reading strategy use and reading comprehension performance. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 1, 65–85. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2015.5.1.4

Marsh, H. W., Pekrun, R., Parker, P. D., Murayama, K., Guo, J., Dicke, T., et al. (2017). Long-term positive effects of repeating a year in school: six-year longitudinal study of self-beliefs, anxiety, social relations, school grades, and test scores. J. Educ. Psychol. 109, 425–438. doi: 10.1037/edu0000144

Mason, L. H. (2004). Explicit self-regulated strategy development versus reciprocal questioning: effects on expository reading comprehension among struggling readers. J. Educ. Psychol. 96, 283–296. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.96.2.283

McCombs, B. L., Daniels, D. H., and Perry, K. E. (2008). Children’s and teachers’ perceptions of learner-centered practices, and student motivation: implications for early schooling. Elem. Sch. J. 109, 16–35. doi: 10.1086/592365

Mezirow, J. (2000). “Learning to think like an adult: core concepts of transformation theory” in Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in Progress . ed. J. Mezirow (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass), 3–34.

Morrow, L. M. (1985). Retelling stories: a strategy for improving young children’s comprehension, concept of story structure, and oral language complexity. Elem. Sch. J. 85, 647–661. doi: 10.1086/461427

Naimie, Z., Siraj, S., Piaw, C. Y., Shagholi, R., and Abuzaid, R. A. (2010). Do you think your match is made in heaven? Teaching styles/learning styles match and mismatch revisited. Proc. Soc. Behav. 2, 349–353. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.023

Nassaji, H. (2002). Schema theory and knowledge-based processes in second language reading comprehension: a need for alternative perspectives. Lang. Learn. 52, 439–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9922.2007.00413.x

Nelson, A. L., Purdon, C., Quigley, L., Carriere, J., and Smilek, D. (2015). Distinguishing the roles of trait and state anxiety on the nature of anxiety-related attentional biases to threat using a free viewing eye movement paradigm. Cognit. Emot. 29, 504–526. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2014.922460

Opdenakker, M. C., and Van Damme, J. (2006). Teacher characteristics and teaching styles as effectiveness enhancing factors of classroom practice. Teach. Teach. Educ. 22, 1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2005.07.008

Özyurt, Ö., and Özyurt, H. (2015). Learning style based individualized adaptive e-learning environments: content analysis of the articles published from 2005 to 2014. Comput. Hum. Behav. 52, 349–358. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.06.020

Pintrich, P. R. (2000). Multiple goals, multiple pathways: the role of goal orientation in learning and achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. 92, 544–555. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.92.3.544

Polly, D., and Hannafin, M. J. (2010). Reexamining technology’s role in learner-centered professional development. Educ. Tech. Res. 58, 557–571. doi: 10.1007/s11423-009-9146-5

Pratt, M. W., and Savoy-Levine, K. M. (1998). Contingent tutoring of long-division skills in fourth and fifth graders: experimental tests of some hypotheses about scaffolding. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 19, 287–304. doi: 10.1016/S0193-3973(99)80041-0

Prescott, J. (2014). Teaching style and attitudes towards Facebook as an educational tool. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 15, 117–128. doi: 10.1177/1469787414527392

Rai, M. K., Loschky, L. C., and Harris, R. J. (2015). The effects of stress on reading: a comparison of first-language versus intermediate second-language reading comprehension. J. Educ. Psychol. 107, 348–364. doi: 10.1037/a0037591

Rance-Roney, J. (2010). Jump-starting language and schema for English-language learners: teacher-composed digital jumpstarts for academic reading. J. Adolesc. Adult Lit. 53, 386–395. doi: 10.1598/JAAL.53.5.4

Rogowsky, B. A., Calhoun, B. M., and Tallal, P. (2015). Matching learning style to instructional method: effects on comprehension. J. Educ. Psychol. 107, 64–78. doi: 10.1037/a0037478

Ryan, R. M., and Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55, 68–78. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Saito, Y., Garza, T. J., and Horwitz, E. K. (1999). Foreign language reading anxiety. Mod. Lang. J. 83, 202–218. doi: 10.1111/0026-7902.00016

Schaefer, K. M., and Zygmont, D. (2003). Analyzing the teaching style of nursing faculty: does it promote a student-centered or teacher-centered learning environment? Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 24, 238–245. Available at: https://journals.lww.com/neponline/Abstract/2003/09000/Analyzing_the_Teaching_Style_of_Nursing_Faculty_.7.aspx

Sellers, V. D. (2000). Anxiety and reading comprehension in Spanish as a foreign language. Foreign Lang. Ann. 33, 512–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-9720.2000.tb01995.x

Şendağ, S., and Odabaşı, H. F. (2009). Effects of an online problem based learning course on content knowledge acquisition and critical thinking skills. Comput. Educ. 53, 132–141. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2009.01.008

Shu, H., and Anderson, R. C. (1997). Role of radical awareness in the character and word acquisition of Chinese children. Read. Res. Q. 32, 78–89. doi: 10.1598/RRQ.32.1.5

Silva, M., and Cain, K. (2015). The relations between lower and higher level comprehension skills and their role in prediction of early reading comprehension. J. Educ. Psychol. 107, 321–331. doi: 10.1037/a0037769

Sorrell, D., and Brown, G. T. (2018). A comparative study of two interventions to support reading comprehension in primary-aged students. Int. J. Comp. Educ. Dev. 20, 67–87. doi: 10.1108/IJCED-08-2017-0018

Souvignier, E., and Mokhlesgerami, J. (2006). Using self-regulation as a framework for implementing strategy instruction to foster reading comprehension. Learn. Instr. 16, 57–71. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2005.12.006

Stanley, C. T., Petscher, Y., and Catts, H. (2018). A longitudinal investigation of direct and indirect links between reading skills in kindergarten and reading comprehension in tenth grade. Read. Writ. 31, 133–153. doi: 10.1007/s11145-017-9777-6

Stevens, E. A., Park, S., and Vaughn, S. (2019). A review of summarizing and main idea interventions for struggling readers in grades 3 through 12: 1978–2016. Remedial Spec. Educ. 40, 131–149. doi: 10.1177/0741932517749940

Stoeger, H., Sontag, C., and Ziegler, A. (2014). Impact of a teacher-led intervention on preference for self-regulated learning, finding main ideas in expository texts, and reading comprehension. J. Educ. Psychol. 106, 799–814. doi: 10.1037/a0036035

Tessier, D., Sarrazin, P., and Ntoumanis, N. (2010). The effect of an intervention to improve newly qualified teachers’ interpersonal style, students motivation and psychological need satisfaction in sport-based physical education. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 35, 242–253. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.05.005

Vasileva-Stojanovska, T., Malinovski, T., Vasileva, M., Jovevski, D., and Trajkovik, V. (2015). Impact of satisfaction, personality and learning style on educational outcomes in a blended learning environment. Learn. Individ. Differ. 38, 127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2015.01.018

Vidal-Abarca, E., Martínez, G., and Gilabert, R. (2000). Two procedures to improve instructional text: effects on memory and learning. J. Educ. Psychol. 92, 107–116. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.92.1.107

Waechter, S., and Stolz, J. A. (2015). Trait anxiety, state anxiety, and attentional bias to threat: assessing the psychometric properties of response time measures. Cognitive Ther. Res. 39, 441–458. doi: 10.1007/s10608-015-9670-z

Waeytens, K., Lens, W., and Vandenberghe, R. (2002). Learning to learn’: teachers’ conceptions of their supporting role. Learn. Instr. 12, 305–322. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4752(01)00024-X

Wang, Y. H. (2016). Could a mobile-assisted learning system support flipped classrooms for classical Chinese learning? J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 32, 391–415. doi: 10.1111/jcal.12141

Wang, Y. H. (2017). The effectiveness of using cloud-based cross-device IRS to support classical Chinese learning. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 20, 127–141. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317027514

Xia, S. L. (2013). The analysis of senior high school entrance Chinese examination in the recent ten years from cognitive level. [dissertation/master’s thesis] . Chongqing: Chongqing Normal University. Available at: https://kns.cnki.net/kns/brief/result.aspx?dbprefix=CDMD

Yamagata, S. (2018). Comparing core-image-based basic verb learning in an EFL junior high school: learner-centered and teacher-centered approaches. Lang. Teach. Res. 22, 65–93. doi: 10.1177/1362168816659784

Zhang, X. (2018). Analysis of the textual test questions of the classical Chinese test papers in China senior high school entrance examination for recent 10 years. [dissertation/master’s thesis] . Liaoning: Liaoning Normal University. Available at: https://kns.cnki.net/kns/brief/result.aspx?dbprefix=CDMD

Zhao, X. H. (2013). Chinese reading anxiety research of ethnic Chinese primary and secondary school students . dissertation/master’s thesis. Nanjing: Nanjing University. Available at: http://sg.xy22.top:90/kns/brief/default_result.aspx?

Keywords: learning style, teaching-learning style, reading research, reading comprehension, intervention

Citation: Dong Y, Wu SX, Wang W and Peng S (2019) Is the Student-Centered Learning Style More Effective Than the Teacher-Student Double-Centered Learning Style in Improving Reading Performance? Front. Psychol . 10:2630. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02630

Received: 13 June 2019; Accepted: 07 November 2019; Published: 27 November 2019.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2019 Dong, Wu, Wang and Peng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shuna Peng, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

News and Media

- News & Media Home

- Research Stories

- School's In

- In the Media

You are here

New research shows effectiveness of student-centered learning in closing the opportunity gap.

While, nationally, students of color and low-income students continue to achieve at far lower levels than their more advantaged peers, some schools are breaking that trend. New research from the Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education (SCOPE) is documenting these successes at four such schools in Northern California —schools in which traditionally underserved students are achieving above state and district averages.

Earlier this year SCOPE released individual case studies of these schools as part of its Student-Centered Schools Study — funded by the Nellie Mae Education Foundation. Today, SCOPE has released the culminating research: a cross-case analysis and its technical report, a research brief and policy brief, and an interactive online tool for educators. Together, these pieces offer evidence of the positive impact of student-centered learning and practical hands-on tools educators can use to reflect on and develop their practice.

Student-centered practices emphasize personalization; high expectations, hands-on and group learning experiences, teaching of 21st century skills, performance-based assessments; and opportunities for educators to reflect on their practice and develop their craft as well as shared leadership among teachers, staff, administrators, and parents. These practices are more often found in schools that serve affluent and middle-class students. Schools that incorporate these key features of student-centered practice are more likely to develop students that have transferrable academic skills; feel a sense of purpose and connection to school; as well as graduate, attend, and persist in college at rates that exceed their district and state averages.

"The numbers are compelling," said Stanford University Professor and SCOPE Faculty Director Linda Darling-Hammond , "students in the study schools exhibited greater gains in achievement than their peers, had higher graduation rates, were better prepared for college, and showed greater persistence in college. Student-centered learning proves to be especially beneficial to economically disadvantaged students and students whose parents have not attended college."

"The products from this study not only provide the evidence that student-centered approaches work but practical tools for educators that can be used to foster meaningful learning that enables all students to thrive, especially low-income students and students of color," said Nick Donohue, President and CEO of the Nellie Mae Education Foundation.

The study also addresses the policy changes that are essential to student-centered schools, including funding, human capital policies, and implementation.

Transforming the kinds of learning spaces most needed by underserved students requires educators who are well-prepared to create authentic learning experiences, grounded in students’ experiences while addressing their gaps in knowledge and skills. Educators need strong pre-service training as well as ongoing support to ensure that they are meeting students’ needs.

Transforming schools requires adequate funding to attract and retain high-quality staff and to provide a rich set of curriculum experiences for students both inside and beyond the school. It also requires that federal and state governments support innovative schools more and mandate less; transform their assessment systems to support deeper learning; and develop systemic learning opportunities among educators, schools, districts, and other agencies. This is no small task, but the practices of the schools in this study—and the contexts that surround them—shed light on the types of teaching and policy supports needed to achieve these goals.

For more information, visit: SCOPE .

More Stories

⟵ Go to all Research Stories

Get the Educator

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

Improving lives through learning

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

- Utility Menu

Manja Klemenčič

Associate senior lecturer on sociology and in general education.

Student centered learning and teaching in higher education: student-centered ecosystems framework and student agency and actorhood

Klemenčič's work on student centered learning and teaching (SCLT) in higher education covers two areas.

Student-centred policies and practices in higher education - student centred higher education ecosystems

Klemenčič has investigated European policies and practices on SCLT both analyzing the theoretical underpinnings of policies and offering prescriptive advice. She introduced the concept of student centered learning and teaching ecosystems at the keynote talk during the 20th Anniversary Conference of the Bologna Process (in June 2019). With Sabine Hoidn, Klemenčič further developed the framework and published it as a conclusion to their co-edited Routledge International Handbook of Student Centered Learning and Teaching in Higher Education (Routledge July 2020). Klemenčič and Hoidn (2020) argue that 'SCLT processes are embedded in and enabled by broader institutional (and national and supranational) environments that consist of a variety of components and related elements – both human and material. These components and elements, [...], constitute student-centered ecosystems (SCEs). SCEs are defined as culturally sensitive, flexible and interactive systems of SCLT in higher education which exist both within higher education institutions and in higher education systems'. So the change from the teacher-centered to student-centered paradigm does not involve only a change in classroom practices, but rather conceiving and working on the number of elemnets that constitute the institutional (or system) student-centered ecosystem. The student centred ecosystems framework is also the backbone to the analytical report commissioned by the European Commission and co-authored with Mantis Pupinis and Greta Kirdulytė and published in May 2020 by NESET, an international advisory network to the European Commission and the Publications Office of the European Union.

Relevant publications:

Klemenčič, M. (2020) Successful Design of Student-Centered Learning and Teaching(SCLT) Ecosystems in the European Higher Education Area. In Bologna Process Beyond 2020: Fundamental Values of the EHEA - Proceedings of the 1999-2019 Bologna Process Anniversary Conference, Bologna, June 24-25 2019, edited by Sijbolt Noorda, Peter Scott and Martina Vukasovic. Bologna, Italy: Banonia University Press. pp. 43-60

Klemenčič, M., M. Pupinis and G. Kirdulytė (2020). Mapping and analysis of student-centred learning and teaching practices: usable knowledge to support a more inclusive high-quality higher education. NESET Report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union

Klemenčič, M. & S. Hoidn (2020). Beyond Student-Centered Classrooms: A Comprehensive Approach to Student-Centered Learning and Teaching Through Student-Centered Ecosystems Framework. In Sabine Hoidn and Manja Klemenčič (eds.) Routledge International Handbook on Student-Centred Learning and Teaching in Higher Education (Routledge)

Student agency and actorhood in student centred learning and teaching

Klemenčič argues that shift to student centred learning and teaching in higher education has to focus on student agency as student capabilities to take responsibility for their learning and to influence their learning environments and learning pathways. This proposition corrects the existing theoretical underpinnings of policies on SCLT in higher education which are based on studnet engagement. Klemenčič analyzes the theoretical underpinnings of EHEA (European Higher Education Area) higher education policies and corrects the conceptual bases on which they are based in her article From student engagement to student agency: conceptual considerations of European policies on student-centered learning in higher education (2017). Furthermore she conceptually advances the conceptions of student agency and actorhood in SCLT with some prescriptive advice in a chapter Students as Actors and Agents in Student-Centred Higher Education in the Routledge Handbook (2020).

The conception of students as actors presupposes student agency which refers to students’ capabilities to actively participate in the learning-teaching processes and the design and implementation of the learning environments. In line with this definition, this chapter analyses student agency in SCLT in two distinct, yet interrelated domains. First, in line with constructivist education theories, the chapter explores issues of students’ autonomy, power relations between teachers and students and students’ responsibilities in learning and teaching processes in classroom environments. Second, drawing on perspectives from neo-institutional theories and HE politics, the chapter analyses student agency in institutional governance and administration of SCLT by exploring the concepts of power relations between students and institutional decision-makers/administrators, students’ sense of agency in and student impact on SCLT. Student agency is one of the central tenets of the contemporary scholarship on student-centered education and this chapter elaborates and advances the conceptions of student agency and actorhood in SCLT. The chapter also introduces a novel perspective on students as agents to bring about change in institutional strategies and culture toward more student-centeredness, a view that has so far been neglected in scholarship.

Klemenčič, M. (2020). Students as Actors and Agents in Student-Centred Higher Education. In Sabine Hoidn and Manja Klemenčič (eds.) Routledge International Handbook on Student-Centred Learning and Teaching in Higher Education (Routledge)

KLEMENČIČ, M. (2017). From student engagement to student agency: conceptual considerations of European policies on student-centered learning in higher education. Higher Education Policy 30(1) 2017: 69–85

KLEMENČIČ, M., ASHWIN, P. (2015). New directions for teaching, learning, and student engagement in the European Higher Education Area. In Remus Pricopie, Peter Scott, Jamil Salmi and Adrian Curaj (eds.) Future of Higher Education. Volume I and Volume II. Dordrecht: Springer

Latest News

- Elected into membership of Academia Europaea - The Academy of Europe

- Global Launch Event of the Bloomsbury Handbook on Student Politics and Representation

- Global Launch Event of the Bloomsbury Handbook on Studnet politics and Representation

- New publication (open-access) The Bloomsbury Handbook of Student Politics and Representation in Higher Education

- Visiting Professor of Higher Education at Faculty of Education, University of Ljubljana (July 2023 - June 2024)

- Joined The Taylor & Francis Editorial Advisory Board

- Interview featured in Vestnik

- Interview featured in OnaPlus

- 6th time voted one of the favorite professors of the Harvard College Graduating Class of 2024 to be featured in in Harvard Yearbook Publication 388

- Published "The Rise of the Student Estate"

- Open access

- Published: 14 September 2018

Teachers’ roles and identities in student-centered classrooms

- Leslie S. Keiler ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5640-2178 1

International Journal of STEM Education volume 5 , Article number: 34 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

180k Accesses

99 Citations

12 Altmetric

Metrics details

Students and teachers in twenty-first century STEM classrooms face significant challenges in preparing for post-secondary education, career, and citizenship. Educators have advocated for student-centered instruction as a way to face these challenges, with multiple programs emerging to shape and define such contexts. However, the ways to support teachers as they transition into non-traditional teaching must be developed. The purpose of this study is to explore the impacts on educators of teaching in student-centered, peer-mediated STEM classrooms and preparing student peer leaders for their roles in these classes. Research questions examined how teachers think about themselves as they implement student-centered pedagogy, the difficulties they face as their roles and identities shift, and the ways they grow or resist growth. Qualitative research conducted at two urban secondary schools documents the diverse experiences and responses of teachers in an innovative, student-centered STEM instructional program. The experiences and perceptions of 13 STEM teachers illuminate the possibilities and challenges for teachers in student-centered classrooms.

All participating teachers described multiple benefits of teaching in a student-centered classroom and differences from traditional classrooms. Their transitions to this type of teaching fell into three major categories based upon past identities and current beliefs. Some teachers found the pedagogy consistent with preexisting identities and embraced it without radical change to their concepts of teaching. They described ways in which the model helped them become the teachers they had always wanted to be. Other teachers, who initially identified as deliverers of STEM content, had more difficult experiences adjusting to student-centered instruction. In one case, a teacher resisted change and exited the program, maintaining her identity and deciding not to become student-centered. Other participating teachers made dramatic shifts in their identities in order to implement the program. These teachers described significant learning curves as they shared responsibility for student learning with student leaders.

Conclusions

This study suggests that radically changing the learning environment can affect teachers’ identities and their approaches to teaching in predictable ways that can inform teacher education and professional development programs for STEM teachers, maximizing the success of teachers as they implement student-centered pedagogy.

Students and teachers in twenty-first century secondary STEM classrooms face significant teaching and learning challenges in preparing for post-secondary education, career, and citizenship. This preparation extends far beyond mastery of content knowledge, which has been the focus of traditional STEM instruction. The Partnership for 21st Century Learning ( 2015 ) includes Learning and Innovation Skills in its Framework for 21st Century Learning. They define these learning and innovation skills as creativity and innovation, critical thinking and problem solving, communication, and collaboration. The Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) are consistent with this focus on twenty-first century skills. The argument for why the new standards are important states:

Science—and therefore science education—is central to the lives of all Americans. A high-quality science education means that students will develop an in-depth understanding of content and develop key skills—communication, collaboration, inquiry, problem solving, and flexibility—that will serve them throughout their educational and professional lives (NGSS, Lead States 2013 , Why section)

The National Council of the Teachers of Mathematics ( n.d. ) include in their Six Principles of School Mathematics concepts relevant to twenty-first century skills: 1) Teaching: “Effective mathematics teaching requires understanding what students know and need to learn and then challenging and supporting them to learn it well,” and 2) Learning: “Students must learn mathematics with understanding, actively building new knowledge from experience and previous knowledge” (p.2). The Partnership for 21st Century Learning defines learning environments that will support the development of these critical skills, requiring professional development that will facilitate a significant pedagogical shift.

Reasons for student-centered STEM instruction

Research about student-centered instruction in STEM, with students taking an active role in the learning process rather than being passive recipients of information from the teacher, demonstrates outcomes consistent with developing 21st century skills and STEM mastery. A variety of instructional models in STEM classes define themselves as student-centered (Boddy et al. 2003 ; Kazempour 2009 ; Moustafa et al. 2013 ; Odom and Bell 2015 ; Qhobela, 2012 ; Tamim and Grant 2013 ; Yukhymenko et al. 2014 ). Research about such models has tended to focus on the experiences of and outcomes for the students, which are largely positive in both cognitive and affective domains. Educators have used constructivist theory to develop a variety of student-centered instructional approaches, each with its own research base and consistently positive student impacts. Research about student-centered, constructivist classrooms documents increases in students’ higher order thinking, learning, and motivation, particularly in STEM classes (Boddy et al. 2003 ; Moustafa et al. 2013 ). Research about specific models highlights commonalities across constructivist, student-centered STEM learning environments. For example, inquiry-based instruction, grounded in constructivist theory, has yielded a variety of benefits for students including learning of STEM content and process skills, increased levels of engagement, positive attitudes about science, and enhanced non-cognitive skills (Juntunen and Aksela 2013 ; Kazempour 2009 ; Keys and Bryan 2001 ; Odom and Bell 2015 ). Problem-based learning (PBL), another student-centered approach that requires groups of students to explore real-world problems, has been shown consistently to increase performance in science courses and enhance science content knowledge, as well as improve critical thinking, student dispositions, student behavior, and attitudes about learning (Burris and Garton 2007 ; Gordon et al. 2001 ). Project-based learning (PjBL), a similar student-centered model that extends solving a problem to completing a project, has been linked to gains in student motivation, critical thinking, and academic skills in STEM classes (Tamim and Grant 2013 ). Further, research demonstrates that STEM classes that implement democratic science pedagogy support the development of critical science agency among participating urban students, which “opens doors for students to engage in science and to redress power differentials in their lives” (Basu and Barton 2010 , p. 86). This student empowerment, which happens in urban STEM classes focused on social justice, enacts Friere’s goal of student agency (Gutstein 2007 ). This set of examples from specific student-centered pedagogies illustrates a pattern of positive impacts of student-centered instruction in STEM classes. This diverse range of benefits across multiple studies and contexts justifies the increasing pressure on STEM teachers to implement student-centered instruction (Lew 2010 ), including in current teacher assessment systems (see Danielson 2014 ).

Teachers’ roles and responsibilities in student-centered STEM classrooms