- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous

- Next chapter >

Introduction

- Published: April 2010

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The only extended attempt at defining Transcendentalism by a participant came from Ralph Waldo Emerson. In a lecture on “The Transcendentalist” delivered at the Masonic Temple in Boston in December 1841, Emerson, whose name was identified by the public as synonymous with the movement, stated, “What is popularly called Transcendentalism among us, is Idealism; Idealism as it appears in 1842” ( EmCW 1:201). A few pages later, in typical Emerson fashion, he gave another definition: “Transcendentalism is the Saturnalia or excess of Faith” (1:206). These definitions did not satisfy skeptics then, and they appeal even less to scholarly inquisitors today. The Oxford Handbook of Transcendentalism presents fifty wide-ranging essays that exhibit this diverse and influential movement's complexity and its contemporary relevance.

These essays suggest that Emerson's broad-based definitions are, in fact, useful overtures for any reader embarking on a study of these remarkable and eclectic figures known as the Transcendentalists. Though they disagreed on many things, as a group they rose to challenge the materialism and the insularity of an expanding United States by bringing to its shores the latest texts from across Europe and Asia: German theology and European post-Kantian philosophy; Romantic poetry and fiction, from Goethe to George Sand to Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Wordsworth, and Thomas Carlyle; Persian poetry and Buddhist and Hindu scriptures. Consolidated as a group by their rebellion against conservatives, who were shocked at such daring cosmopolitanism, various Transcendentalists then diverged to found and contribute to a range of radical reforms in religion, education, literature, science, politics, and economics, centreed especially on securing equal rights for the working classes, women, and slaves. The fate of their movement, as it splintered, diversified, foundered, and triumphed, should rivet every scholar and student of contemporary affairs, for at a time of economic, religious, and political crisis, the Transcendentalists asked key questions: How can art reawaken faith in a reborn cosmos? How can an individual live a moral life in a society rife with injustice and cruelty? Is self-cultivation a means to social reform or a distraction from urgent social issues? How might America—indeed, should America—lead a world that it cannot master or control? Transcendentalists worked out answers to these questions, and though today we might differ with their strategies and solutions as we face our own parallel crises, we have the advantage of their words and experience, their triumphs and defeats, to instruct and inspire us. Never have the Transcendentalists had so much to say to their descendents.

Emerson's lecture demonstrates that he regarded Transcendentalism primarily as a philosophical movement. He argues that humankind was “ever divided into two sects, Materialists and Idealists; the first class founding on experience, the second on consciousness; the first class beginning to think from the data of the senses, the second class perceive that the senses are not final, and say, the senses give us representations of things, but what are the things themselves, they cannot tell” ( EmCW 1:201). In a brilliant analogy, he shows that, while the Transcendentalist views material objects from the perspective of a participant in the physical world, at the same time “he looks at these things as the reverse side of the tapestry, as the other end , each being a sequel or completion of a spiritual fact” (1:202). This analogy shows that Transcendentalism is also a religious or spiritual movement: “The Transcendentalist…believes in miracle, in the perpetual openness of the human mind to new influx of light and power; he believes in inspiration, and in ecstasy” (1:204). But philosophy, religion, and spirituality are not enough: The Transcendentalist cannot take refuge in such pursuits but must derive from them the knowledge and inspiration needed to interact with and, importantly, to reform the day-to-day world, to improve society—and make good on the American promise—for all. As Emerson says, “the good and wise must learn to act, and carry salvation to the combatants and demagogues in the dusty arena below” (1:211).

Scholars through the years have been troubled by the fact that Transcendentalism was not monolithic or easily defined and that it was not, in fact, an organized movement at all. The name “transcendentalism” was initially bestowed by the movement's critics to ridicule that diverse group of philosophical idealists who held that certain beliefs and values transcended mere sensory experience. Some of these idealists were ministers, others former ministers; most were Harvard College or Harvard Divinity School graduates, while others were self-educated; most were men, but women made substantial contributions; most were from the Boston area, but some were from Connecticut and Virginia; most published prose, others poetry, but only one wrote fiction; most left formal religious institutions, but others remained in them; but all, key to their Transcendentalism, sought their own way of leading a purpose-driven life. Starting in the 1830s, these individuals met together, read each other's writings, attended each other's lectures and sermons, and often disagreed. Few of them liked being labeled “Transcendentalists” because such glib identification flattened out the complexity of their individual beliefs.

The Transcendentalists embraced a metaphysical position that placed God within the world and within each person rather than outside humankind's experience and knowledge. Though many of them grew up reading John Locke, they grew to reject his philosophical belief that the mind is a tabula rasa, a blank slate, at birth, on which all sensory impressions are written (the “Understanding”), in favor of the idealism of Immanuel Kant, which held that certain categories of preexisting knowledge could be grasped intuitively (“Reason”). They championed the new European literature and philosophy over traditional British Enlightenment figures. They did not reject but redefined Enlightenment ideals of scientific experimentation, following the latest scientific theories, which sought not only to understand the phenomena of nature through empirical investigation and sensory experience but also to discover behind the screen of appearances nature's underlying truths, its laws or principles. They prized the quintessential American concept of individuality (as evidenced in their two most often read and taught works, Emerson's “Self-Reliance” and Henry David Thoreau's Walden) even as they experimented with new forms of association and community. They worked to transform antebellum educational methods of learning by rote memorization and replaced them with teachers who would draw out their students' own thinking rather than having them parrot conventional views. As ardent believers in social and political reform, they worked to abolish slavery and establish civil rights for women as well as to overhaul the church, the government, prisons, mental institutions, and health and dietary practices. They believed that Nature, like the gnomon on the face of a sundial, points to divine lessons from which we can benefit once we learn to sympathize with the natural world; as such, although the words did not yet exist, they were early ecologists and pioneer environmentalists. The Transcendentalists were, in other words, innovators and precursors of much that we now regard as central to American life, culture, literature, and national identity.

In “The Transcendentalist,” Emerson addresses the state of literary study in the young nation: “Our American literature and spiritual history are, we confess, in the optative mood; but whoso knows these seething brains, these admirable radicals, these unsocial worshippers, these talkers who talk the sun and moon away, will believe that this heresy cannot pass away without leaving its mark” ( EmCW 1:207–8). The contributors to this volume demonstrate that Transcendentalism has indeed left “its mark,” and they shed new light on its rich legacy to American life, letters, and culture. They also adhere to Emerson's admonition: “Each age…must write its own books; or rather, each generation for the next succeeding” (1:56). These essays not only present a survey of previous and current interpretations of Transcendentalism but suggest potential new directions as well for a new generation of creative readers.

The fifty essays in this book are arranged topically and in a broadly chronological order; contributors were encouraged not to review standard coverage of topics but to provide new perspectives on old themes, explore new directions, open new topics, and point to work demanded by a new century. There is naturally some degree of overlap, which the editors hope will provide a variety of fresh perspectives; while we have provided a broad range of topics, we do not aspire to completeness of coverage—were such even possible. The opening section, “Transcendental Contexts,” sets the stage for the rise of Transcendentalism in the early nineteenth-century's transatlantic history and culture, from world literature and philosophy, to world historical movements in history, to the unique conditions of American print culture and religious history, out of which Transcendentalism had its most immediate birth. The second section, “Transcendentalism as a Social Movement,” follows the contested and multifarious diversification of Transcendentalist ideas as they ramified outward into the world, from religion, to politics, to education and self-culture, including abolitionism, women's rights, utopian communities, the vexed legacy of Manifest Destiny, and the origin of American environmentalism.

The third section, “Transcendentalism as a Literary Movement,” turns to the work of Transcendentalists as linguistic performers in a range of genres both oral and written: from conversations, to diaries and journals, to letters, lectures, and sermons, to printed essays, periodicals, and books in genres ranging from poetry and literary criticism to travel, nature, and life writing. The fourth section, “Transcendentalism and the Other Arts,” suggests new opportunities for scholarship by examining visual arts, photography, architecture, and music; the fifth, “Varieties of Transcendental Experience,” points beyond the texts themselves to sketch the diverse experiential worlds that Transcendentalism created for its proponents, geographically from Boston to the globe, culturally from the family living room to high philosophy, and historically from the Transcendentalists' day to our own. Finally, “Transcendental Afterlives” provides a look back, starting with the perspective of the post–Civil War generation, who tried to reconstitute Transcendentalism for their own time, to the various threads—politics, nature and environmental activism, poetry, and electronic texts—through which Transcendentalism has come down to our own day as a living legacy not just for scholars but also for readers, activists, and pilgrims. Given that these essays are thematic rather than bibliographical, appendices provide brief bibliographies of the figures discussed, together with a chronology of the movement and selected historical landmarks.

Part I , “Transcendental Contexts,” begins with the study of Greek and Roman classics, which pervaded education for every literate man and woman. As K. P. Van Anglen establishes, study of the classics pointed the Transcendentalists not only backward to a traditional grounding in concepts of the “good” and the “true” but also forward to redefine a fresh sense of origins, a commitment “to autonomy, independence, and intellectual renewal.” Similarly, Robin Grey shows that though Transcendentalists famously rejected their predecessors, particularly the materialism of Locke and the skepticism of Hume, they also turned to Enlightenment writers, particularly the Scottish School of Common Sense philosophers, to define their concepts of the social and moral dimensions of human nature, a dimension “not always acknowledged by scholars of Transcendentalism, who have tended to focus on their individualism.” A second corrective is offered by Alan Hodder in his essay on Transcendentalism's Asian influences—ironically, a product of British imperialism that allowed Emerson, Thoreau, and Alcott to break the “centuries-long dominion of Christianity in the West.” Frank Shuffelton offers a third corrective by connecting the Transcendentalists' religious hunger for mystical experience to the Puritans' ability to discover God's grace and glory in earthly experience and by redrawing with a difference Perry Miller's line “from Edwards to Emerson.” Dean Grodzins explores in detail the origin of Transcendentalism “as a phase of American, or more precisely New England, Unitarianism” that “forced the expansion of the boundaries of liberal religious fellowship” and opened new possibilities for religious action. By contrast, Michael Ziser sets the Transcendentalists' religious revolution in a world perspective by tracing the powerful line of revolutionary activity that spread from America in 1776, through the French and Haitian revolutions and the Bolivarian wars of independence in South America, to the European Revolution of 1848 and beyond. The resulting “Romantic revolution” in literature and the arts and sciences, centreed in Great Britain and continental Europe, sent shock waves back across the Atlantic that, as Barbara Packer shows, led to what one participant called a “remarkable outburst of Romanticism on Puritan ground.” Finally, these were the years as well of the Industrial Revolution, which completely redefined print and manuscript production, dissemination, and reception as print went from conditions of Revolutionary-era scarcity to antebellum abundance; as Ronald Zboray and Mary Zboray show, while the “sensorium” that emerged was structured by the expressive social technology of print, during this era print culture did not replace but helped maintain “interpersonal relationships under stress from often chaotic socioeconomic conditions.”

Part II takes up “Transcendentalism as a Social Movement.” Although only one extended study, Anne Rose's Transcendentalism as a Social Movement (1981), has focused on the totality of Transcendentalists' efforts to improve their society, numerous studies have recovered their contributions to specific nineteenth-century reform movements. The essays in this section provide historical overviews that establish the breadth of the Transcendentalists' activism as well as point to the conflicted nature and resulting controversy of their often radical speeches and writings. Albert von Frank contends that the relationship of Transcendentalism to Unitarianism is more complex than is commonly supposed and that the most central of the Transcendentalists' religious motives were adopted and ironically refashioned by later nineteenth-century popular movements. Len Gougeon discusses how drastic social changes in antebellum America directly impacted the everyday lives of Transcendentalists—from their personal financial wealth to their ability to secure meaningful employment. Wesley Mott's essay on education reveals the centrality of this subject to the Transcendentalists' concerns, so much so that Mott argues “that ‘the Movement’ might just as fairly be defined as an educational demonstration.” Transcendentalists' critique of their increasingly industrialized society is documented by Lance Newman, who reveals, particularly, how the Transcendentalists' concern with society's disconnection from nature led to a nascent environmental consciousness. Lawrence Buell, in “Manifest Destiny and the Question of the Moral Absolute,” points out the “unresolvable split image” of Transcendentalists' reform identity—the disconnect between their ideals and their pragmatic resolve to live in the world as it is, particularly as individuals attempted to “make sense of the paradox of Transcendentalism's strong antiestablishment tendencies as against the signs of complicity with American expansionism.” Similarly, Joshua Bellin points to the troubling paucity of Transcendentalists' seeming concern or action over U.S. genocide of its native population. Although Sandra Petrulionis demonstrates the pivotal antislavery activism of many Transcendentalists, Bellin notes the disparity between these efforts and those on behalf of Native Americans. With regard to another controversy, Phyllis Cole focuses in “Woman's Rights and Feminism” on the empowering “protofeminism” generated by the rhetoric and the idealism of Transcendentalism. On a more individual level, Mary Shelden demonstrates that self-reform pervaded the immediate reality of Transcendentalists: From austere vegetarian diets to physical activity and homeopathic regimes, they attempted to purify their physical bodies in addition to their spiritual selves. Such efforts were enabled, at least briefly, by joining with a community of the like-minded, as Sterling Delano demonstrates in “Transcendentalist Communities.”

Part III , “Transcendentalism as a Literary Movement,” takes up the subject that most often dominates discussions of Transcendentalism, yet for a movement usually taught in the literature classroom, Transcendentalists were decidedly unconventional and, moreover, rather less productive of canonical works than other American authors. Although two of them, Emerson and Thoreau, are included in F. O. Matthiessen's classic study of the literary “American Renaissance,” the Transcendentalists did not write best-selling fiction, publish the great American novel, or leave behind volumes of classic poetry. However, the wealth and value of their literary output, what Emerson valorized as “literature of the portfolio,” is readily apparent in the array of genres discussed in this section. Ed Folsom leads off with a comprehensive essay on transcendental poetics, which on the one hand assesses the modest output of individual poets, while on the other argues for the instrumental role of Transcendentalism (especially on Emerson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson) in shaping the trajectory of the two poets most central to nineteenth-century American literary studies: Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson. Robert Sattelmeyer investigates journal keeping, this most transcendental of genres, practiced by nearly every figure associated with the movement, the wealth of which “ranged from the occasional notation of daily activities to highly self-conscious literary composition.” Similarly, Robert Hudspeth reveals the often artistic, self-consciously literary “performance[s]” of Transcendentalists' letters—private writings that often allowed the correspondents to achieve a closer connection than was possible in person. The genre with which most Transcendentalists were familiar was an oral one—the sermon, delivered weekly from various New England pulpits, and Susan Roberson shows that these dramatic messages offer a “valuable window into the evolution of Transcendentalism.” Secular outlets for their spoken eloquence included the public venues examined by Kent Ljungquist; not only did Transcendentalists such as Emerson and Alcott exploit the lecture podium to offer literary, philosophical, and historical addresses, but Thoreau, Caroline Healey Dall, and others spoke out on political topics such as slavery and women's rights. The oral nature of the movement's œuvre is further elucidated by Noelle Baker's discussion of Transcendentalist conversations, a practice especially empowering to women that drew on a history and culture rich in informal reading and writing practices. As Baker explains, Bronson Alcott “invested conversation with natural and supernatural attributes and with the agency to reform individuals and society.” The print medium in which Transcendentalists enjoyed the greatest success was the vastly expanded periodical market, the subject of Todd Richardson's work, a study that, as Richardson notes, is now greatly enabled by various digitization projects, in addition to the recent formation of the Research Society for American Periodicals. Premier among periodical outlets for Transcendentalist authors was, of course, the Dial , the focus of Susan Belasco's essay, which assesses the impact of this four-year quarterly on the workload of its editors, Margaret Fuller and Emerson, and on the literary aspirations of its numerous contributors. As critics, Fuller and Emerson differed in their mode of appraising literary works, according to Jeffrey Steele. For Emerson, individual genius transcended time and place—great literature came about “as the expressive acts of exceptional individuals”; in contrast, Fuller valued both the end product and the contexts in which authors created. For Steele, then, Fuller's goal as a critic was not only “to define empowering ideals of selfhood but also to measure the social and psychological obstacles to that imagined development.” Barbara Packer demonstrates that examples of possibly the Transcendentalists' “best writing” are found in the popular antebellum genre of travel writing. From Emerson's travel journals, to Fuller's Summer on the Lakes, in 1843 and dispatches from Europe, to Thoreau's A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers , travel writing permitted the free flow of ideas and individual reflection most suited to Transcendentalist expression. Thanks in large part to Thoreau and Walden , the literary genre most indelibly associated with Transcendentalism is nature writing, which, as Philip Gura's essay on this subject evaluates, reflects the Transcendentalists' attempts both to interrogate and to honor their relation to the external world. Thus, this genre as a whole includes some of the earliest examples of contemporary ecocriticism. Robert Habich elaborates on the Transcendentalists' privileging of self-reflection, particularly as individuals memorialized each other and as biographers have since narrated their life stories. For Emerson, as Habich reminds us, biography trumps history, and his essay usefully weighs how the genre transformed before and after the Civil War, from work that “constructs subjects with an eye to the essential and the philosophical” to studies that do so with a regard for “the individual and the social.”

Part IV , “Transcendentalism and the Other Arts,” expands the range of Transcendentalist interest and practice beyond print culture. Albert von Frank takes the 1839 exhibition of Washington Allston's romantic paintings—rather than the work of Hudson River School artists—as the focus of the Transcendentalists' most intense encounter with the art of painting, and shows that it prompted several quite distinct rhetorics of art criticism. Photography vexed this relation in both creative and disconcerting ways, as Sean Meehan shows; both Emerson and Thoreau were intrigued by early photographic technology, which emerged “alongside Transcendentalists' interest in reproducing in thought and word the legible traces of the invisible in the visible world.” Domestic architecture presented another new aesthetic, one that offered to improve domestic life; indeed, Barksdale Maynard argues that Transcendentalism's most famous house, the one Thoreau built at Walden Pond, was a sophisticated and creative adaptation of the contemporary craze for country “villas,” which allowed the urban dweller to retire to nature and led directly to the suburban American home-and-garden ideal. Finally, Ora Frishberg Saloman shows that Transcendentalism left a rich legacy of music criticism in the writings of John Sullivan Dwight and, moreover, helped build “a strong intellectual foundation for the development of art music in the nation,” including improvements in concert practices and “increased respect for the valuable role of creative and performing artists in American society.”

Part V , “Varieties of Transcendental Experience,” expands the range of Transcendentalism in several directions. By focusing on the local, Ronald Bosco shows how succeeding generations traveled much in Concord, their steps directed by guidebooks to the relics of Transcendentalism—buildings and monuments—that re-created the hometown of Emerson, Thoreau, and the Alcotts as a quaint village outside the stream of time that promised to reenchant the modern world. On the other hand, Robert Scholnick follows a cosmopolitan arc of partnership along the transatlantic axis from Boston to London, recovering the vigorous radicalism of John Chapman's Westminster Review and the channel opened by Chapman and his stable of contributors (including Harriet Martineau and George Eliot), by which Transcendentalism and British radicalism energized and challenged one another. Taking up the global scale, Laura Dassow Walls points to the cosmopolitanism at the heart of Transcendentalism, which paradoxically fused the world's texts into an image of American nationalism while also using them to remake America into a global, planetary ideal that extended a “cosmopolitics” to human and nonhuman planetary partners. As Elizabeth Addison writes, the personal relationships that forged the movement and kept it going are becoming “ever more evident”; this cross-generational project then branched into “lateral connections with others of like mind, writers and reformers well beyond Boston and Concord.” Philip Cafaro's essay on “virtue ethics” takes up the Transcendentalists' challenge to conventional ethics and their attempts to vitalize American ethical thought, as the traditional foundations seemed to be giving way; in response to the challenges of modernity, they emphasized “the full flourishing of the whole human person” and asserted that change and uncertainty are “ineliminable aspects of human life” in an evolving world that is continually bringing radical new possibilities for human life. Lawrence Rhu further examines the ethical philosophy of Transcendentalism through the recent work of Stanley Cavell, who has built on Emerson and Thoreau to deepen our contemporary understanding of the Transcendentalists' skepticism and engagement with tragedy. In Cavell's view, the intractable predicaments we face in life require of us “patience, if not surrender, and the transformation of the self,” a striving toward the perfectable without any assurance that perfection can be reached. Eric Wilson also takes up the Transcendentalists' response to a fluid, changing, and increasingly turbulent world but through aesthetics rather than ethics: In their quest to make words that are alive, “the time-honored distinction between words and things can entirely collapse and thus leave animated words and verbal vitalities,” a “generative coincidence of opposites, a pulsating synthesis of mind and matter.” That science is indeed at the heart of the Transcendentalists' philosophy and theology, not an “extraterrestrial domain” peripheral to the concerns of humanists, is the argument advanced by Laura Dassow Walls, who offers not a detailed study of any one science but a hypothetical portrait of how Transcendentalism might look were science and technology restored to the integral place they held in literature and culture during the nineteenth century. William Rossi tackles head-on the evolutionary science that undergirded the Transcendentalists' understanding of a changing nature. He offers a detailed case study of the way they not only assimilated radical thought from cosmopolitan and continental sources but also fused “moral philosophy and experiential theology with science, grounding all in a species of natural law.” Finally, Richard Kopley looks to the key American writers—“naysayers”—who set themselves in opposition to the Transcendentalist school. To the “prelapsarian” vision of Emerson and the Transcendentalists, Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Herman Melville offered a “postlapsarian” corrective, one that more fully acknowledged the darker side of human life: “Neither vision was ascendant. And the tension between the two endures—for we need both.”

That the tension and the vision do indeed endure is the theme of the final section, “Transcendental Afterlives.” Although its heyday was broadly the three decades prior to the Civil War, Transcendentalism lived on through the thought and writings of subsequent generations. Both in the specific lives of individuals such as Thomas Wentworth Higginson and Caroline Healey Dall, who as young adults imbibed the mantra of self-culture from reading Emerson and attending Fuller's conversations, and in the principled examples of civil protest and calls for an environmental consciousness, the Transcendentalists bequeathed to later generations the urgency—the moral obligation—of the examined life. These various afterlives are taken up in this section, first by David Robinson, whose study of the Free Religion movement traces the role played by Higginson and other second-generation Transcendentalists in the establishment and ensuing success of a “‘pure’” religious community that perpetually reformed itself, after the manner of Transcendentalism. Linck Johnson discusses the now centuries-long afterlife of Thoreau's exemplary political protest in “Civil Disobedience,” and he sets straight the various, often uncontexualized, misinterpretations of this famous essay, whose influence is arguably greater than any single Transcendentalist-authored work; Johnson argues that “Civil Disobedience” “speaks in different voices to those engaged in other protests and social causes.” Robert Burkholder discusses Thoreau's other primary legacy in an essay that evaluates the Transcendentalists' centrality to the genre of nature writing, particularly in their example of humanism coalescing with a political sensibility toward the environment—today's “ecocentrism”—which directly inspired John Muir, John Burroughs, Rachel Carson, and others to environmental activism. Paying homage to the sine qua non of Transcendentalist places is the focus of Leslie Wilson's “Walden: Pilgrimages and Iconographies,” which appraises the afterlife of Thoreau's cabin site at Walden Pond—from the first stone laid at what is now a sprawling cairn to the late twentieth-century crusade to save Walden Woods from development. Wilson points out that, in contrast to the other literary and historical Concord sites, “Walden beckons as a shrine, offering retreat, removal from the distractions of town life, opportunity for contemplation, enhanced receptivity to spirit, and personal transformation.” Saundra Morris argues for the longevity and centrality of Transcendentalist thought on major American poets and stresses Transcendentalism's “fundamental concern with a politically ethical aesthetics that calls us to imagine the poetically beautiful in terms of the politically just.” And in “The Electronic Age,” Amy Earhart situates Transcendentalism scholarship in the surfeit of online search tools, databases, full-text articles, and Google books. She examines resources essential to Transcendentalism studies and authors; while noting the limitations of each, she points to the direction of future technologies.

Given the expansive topics covered in this volume, it is perhaps ironic that we conclude by emphasizing the need for continued scholarship on the Transcendentalists and Transcendentalism. However, most of these essays raise questions and point to unexamined terrain—figures and eras only partially recovered or contextualized. Particularly in light of the ongoing democratization of the archive achieved by a plethora of digitized collections, additional biographical treatments are needed. While we have enjoyed recent studies of Emerson, Fuller, Parker, Whitman, Mary Moody Emerson, the Peabody sisters, and Lydia Maria Child, we await those on William Henry Channing, Caroline Healey Dall, Franklin B. Sanborn, Ednah Dow Cheney, and Moncure Conway. Similarly essential are more published volumes of private writings: The letters and journals of Thomas Wentworth Higginson and Bronson Alcott are only partially available; the letters of most antislavery women and other reformers remain unpublished. The ongoing effort to situate various Transcendentalists in the context of antebellum reform must persist, particularly their role in the woman's rights movement. Additionally beneficial would be studies of Transcendentalists in dialogue with each other and with their society on crucial issues such as manifest destiny and U.S. expansionism, the Mexican War, the nullification crisis, the Fugitive Slave Law, and Charles Darwin's publications. Although the relation of Emerson and Thoreau to nineteenth-century science and evolutionary theory has been established, what of other figures, particularly women like Mary Moody Emerson, Sarah Alden Bradford Ripley, and Susan Fenimore Cooper? How would the conventional picture of this period change if science and technology studies were to become integral to literary and cultural studies instead of supplemental background material? No one doubts that “nature” was a central term in nineteenth-century literature, especially in the United States—Perry Miller's “Nature's Nation”—but too often “nature” is unproblematized and unmediated. Much of this work needs to be pursued through the periodical archive, and indeed, the explosion of the digital archive suggests completely new avenues for periodical studies—for example, how do the letters published in various newspapers from Transcendentalist lecturers and reformers, particularly in their western travels, expand the boundaries of and expectations for travel literature? For literary criticism? For science and exploration? We must also reinforce the transnational, even planetary, scope of the movement through studies that recover the rapidly changing relationships between American national identity and the evolving identities of other nations, whether imperialistic or cosmopolitan, both within (Native American) and without, hemispheric, transatlantic, and transpacific. It is, after all, in their diverse conceptions of America, as well as in their refusal to be more than a “club of the like-minded” (in James Freeman Clarke's words), that the strength and ongoing relevance of the Transcendentalists reside.

Joel Myerson and Laura Dassow Walls are both grateful to Steven Lynn and William Rivers, chairs of the English department at the University of South Carolina, for helping them to do their work (especially in Mr. Myerson's case since he is supposedly retired). They also thank Dean Mary Anne Fitzpatrick for her support and Jessie Bray for her assistance in preparing the volume. Sandra Harbert Petrulionis thanks Penn State Altoona's Division of the Arts and Humanities and Academic Affairs for their ongoing support of her research; for proofreading and other administrative assistance, she thanks Christina Seymour.

All three editors would like to thank the contributors for responding to our invitations with such enthusiasm and creativity and for their patience during the long process of pulling this volume together. We also appreciate the patience of our respective and long-suffering spouses. Finally, we are grateful to Shannon McLachlan for presenting us the challenge and opportunity of preparing this volume and for her continued support as we worked on it.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Social Sciences

© 2024 Inquiries Journal/Student Pulse LLC . All rights reserved. ISSN: 2153-5760.

Disclaimer: content on this website is for informational purposes only. It is not intended to provide medical or other professional advice. Moreover, the views expressed here do not necessarily represent the views of Inquiries Journal or Student Pulse, its owners, staff, contributors, or affiliates.

Home | Current Issue | Blog | Archives | About The Journal | Submissions Terms of Use :: Privacy Policy :: Contact

Need an Account?

Forgot password? Reset your password »

Transcendentalism

I. definition.

Transcendentalism was a short-lived philosophical movement that emphasized transcendence , or “going beyond.” The Transcendentalists believed in going beyond the ordinary limits of thought and experience in several senses:

- transcending society by living a life of independence and contemplative self-reliance, often out in nature

- transcending the physical world to make contact with spiritual or metaphysical realities

- transcending traditional religion by blazing one’s own spiritual trail

- even transcending Transcendentalism itself by creating new philosophical ideas based on individual instinct and experience

II. Transcendentalism vs. Empiricism vs. Rationalism

When the Transcendentalists first came on the scene, philosophy was split between two major schools of thought: empiricism and rationalism . Transcendentalism rejected both schools, arguing that they were both too narrow-minded and failed to account for different kinds of transcendence.

III. Quotes About Transcendentalism

“Go alone…refuse the good models, even those most sacred in the imagination of men, and dare to love God without mediator or veil.” ( Ralph Waldo Emerson )

Probably no one is more strongly associated with transcendentalism than the American essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson. Emerson wrote fiery essays arguing for independence, self-reliance, and going beyond the boundaries of society. In this short quotation, Emerson expresses two of his central ideas: first, that you should follow your own path rather than imitating others, no matter how noble or admirable they may be; and second, traditional religious organizations are unnecessary in our spiritual path and we should seek an independent, one-to-one relationship with God.

“The reason I talk to myself is because I’m the only one whose answers I accept.” (George Carlin)

Stand-up legend George Carlin brought a strong Emersonian flavor to his comedy, a style that continues to be popular with modern stand-up comics. Like Emerson, Carlin hated social rules and was constantly pushing limits – using cursewords in his routines and talking about taboo subjects like race and sexuality at a time when standup comics almost never dared to broach these uncomfortable topics. Emerson would have liked the quote, which celebrates both social awkwardness (talking to yourself) and independent thinking.

IV. The History and Importance of Transcendentalism

Transcendentalism was America’s first major intellectual movement. It arose in the Eastern U.S. in the 1820s, when America had fully established its independence from Britain. At that time, the country was led by the first generation to have been born after the Revolutionary War – a generation that had never known anything other than independence. People in this generation couldn’t understand their parents’ reverence for European culture and philosophy, a reverence that was still strong in spite of the Americans’ desire for political independence. To them, America was its own nation, on its own continent, with its own laws and customs, and it needed to have its own art, culture, and philosophy as well – even its own religion! Transcendentalism was designed to fill all of these roles.

Although Transcendentalism didn’t grow into a flourishing philosophical school as its founders hoped (more on that in section 6), Transcendentalist ideas heavily influenced other movements and continue to have echoes today. The Transcendentalist movement was the main inspiration for William James and other founders of the Pragmatist school, which has been by far America’s most significant contribution to global philosophy.

The Transcendentalists even influenced European philosophy – Nietzsche, a revered if eccentric German philosopher, cited Transcendentalists as one of his main influences. Ironically, this means that the American thinkers were a strong philosophical inspiration to German nationalism and even Nazism, with their themes of strong individual leadership, rejecting traditional religion and morality, and breaking down limits so as to usher in a glorious future. Clearly, Emerson and Nietzsche would have strongly disapproved of Hitler and the Third Reich, but it goes to show how philosophers’ ideas can have unexpected consequences when they enter the realms of society, culture, and politics.

V. Transcendentalism in Popular Culture

There are many Transcendentalist themes in the sci-fi action movie Equilibrium starring Christian Bale. In the movie, John Preston is a Cleric, a law-enforcement officer required to take an emotion-suppressing pill every day so that he can carry out his duties without the interference of feelings. But when he misses his dose, Preston becomes increasingly aware of flaws in the system.

The film is Transcendentalist in a couple of ways: first, the emphasis on emotions rather than logic and duty. Preston’s moral awakening comes when he gets in touch with his emotions, which suggests that true morality is an emotional experience. Second, Preston ends up rejecting authority, social expectations, and the whole system that he’s been raised in. That makes him a very Emersonian sort of hero.

Many video games have “ranger” or “druid” characters (e.g. Dota 2, Warcraft, or Neverwinter Nights), and they often seem a little like transcendentalists. They live out in nature, or on the fringes of society, surviving by their own skills and living by their own rules – transcending the limits of civilization. In some cases, they also have spiritual or magical abilities that allow them to transcend the ordinary, physical world.

VI. Controversies

Is transcendentalism philosophy.

Transcendentalism never really caught on in professional philosophy, possibly because of the structure of its arguments. As we saw in section 2, transcendentalism rejected both rationalism and empiricism, pointing out the limitations in both logic and observation. But logic and observation are our main ways of attaining the truth, and if you push back against both of them, then what is the foundation of your own argument ?

In other words, Transcendentalism was based on an intuition, a feeling – several philosophers got together and had similar feelings about society, religion, and truth, but what they didn’t have was a set of arguments . As a result, they were not able to persuade new followers other than those who already shared their feelings. The Transcendentalists were brilliant writers, crafting expressive essays and compelling poetry, but they did not write philosophical arguments in the traditional sense.

As a result, some people have argued that Transcendentalism was more of a literary or artistic movement than a philosophical one. Whether or not that’s true really comes down to your definition – if you see philosophy as defined by a method of argument, then Transcendentalism isn’t philosophy. If you see philosophy as defined by an interest in musing about life, then Transcendentalism definitely belongs.

a. Logic and duty

b. Religion and community

c. Emotions and independence

d. All of the above

a. Ralph Waldo Emerson

b. Confucius

c. Socrates

a. Logic / Rationality

b. Empirical observation

The Transcendentalists: Their Lives & Writings

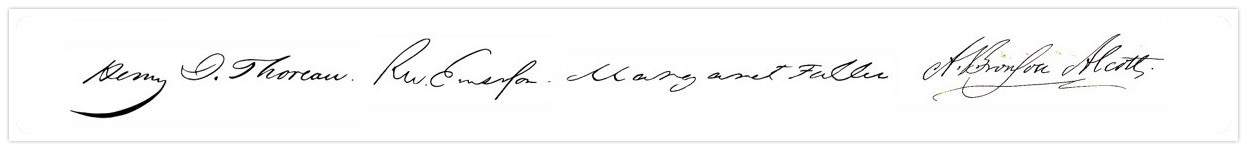

Selected texts and links about the lives, writings, and time of the transcendentalists, including works by and about henry david thoreau, ralph waldo emerson, margaret fuller, bronson alcott and their contemporaries..

What you see here is only the beginning. This is an ongoing project of The Walden Woods Project that will continue to grow so please check back often.

Please report errors to The Walden Woods Project Library .

The views and opinions of authors in the texts or hyperlinks below do not necessarily represent those of The Walden Woods Project but are provided for the purpose of education and the dissemination of information. Reference to any product, service, publication, organization or author does not necessarily constitute or imply an endorsement, recommendation or favoring by The Walden Woods Project. All texts and hyperlinks are provided with the sole purpose of meeting the mission of The Walden Woods Project to collect and disseminate materials relating to the Transcendentalists, their historical context, and their contemporary relevance to environmental and human-rights issues, as well as the work of other environmental writers and social reformers.

About the Transcendentalists

Ackerman, Joy Whiteley — Walden: A Sacred Geography

ALCOTT, AMOS BRONSON (1799-1888)

Alcott, Louisa May (1832-1888)

Angelo, Ray

- Biographical Sketch of Minot Pratt

- Botanical Index to the Journal of Henry D. Thoreau

- Calendar of Flowering Times for Wildflowers and Woody Plants of Concord, Massachusetts

- Place Names of Henry David Thoreau in Concord, Massachusetts (and in Lincoln, Massachusetts) & Other Botanical Sites in Concord

- Thoreau’s Climbing Fern Rediscovered

- Animal Index to the Journal of Henry D. Thoreau

- Gibbons, Prescott (1960- ) — Walden Pond Series

Watson, Amelia Montague (1856-1934)

Blake, Harrison Gray Otis (1816-1898)

Brooks, Charles Timothy (1813-1883)

Brown, John (1800-1859)

Brown, Theophilus (1811-1879)

Cabot, James Elliot (1821-1903)

Channing, Edward Tyrrel (1790-1856)

Channing, William Ellery (1817-1901) — Walks with Ellery Channing ( The Atlantic Monthly , July 1902)

Childs, Christopher — Clear Sky, Pure Light: Encounters with Henry David Thoreau

Cholmondeley, Thomas (1823-1864)

Child, Lydia Maria (1802-1880)

Cranch, Christopher Pearse (1813-1892)

Curtis, George William (1824-1892)

Dickinson, Emily (1830-1886)

Dwight, John Sullivan (1813-1893)

Dymond, Jonathan (1796-1828)

Ells, Stephen F. (1935-2008) — A Bibliography of Biodiversity and Natural History in the Sudbury and Concord River Valley

Emerson, Edward Bliss (1805-1834)

Emerson, Edward Waldo (1844-1930)

Emerson, Ellen Louisa Tucker (1811-1831)

EMERSON, RALPH WALDO (1803-1882)

Freeman, Brister (1744-1822)

Frothingham, Octavius Brooks (1822-1895) — Transcendentalism in New England (from Transcendentalism in New England: A History )

Fruitlands

FULLER, MARGARET (1810-1850)

Fuller, Richard Frederick (1824-1869)

- Recollections of Richard F. Fuller (excerpts)

- The Younger Generation in 1840 ( The Atlantic Monthly , August 1923)

Garrison, William Lloyd (1805-1879)

Gohdes, Clarence L.F. (1901-1997) — Elizabeth Peabody and Her Æsthetic Papers (from The Periodicals of American Transcendentalism )

Greeley, Horace (1811-1872)

Harding, Walter (1917-1996)

Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864)

Hawthorne, Sophia Amelia (Peabody) (1809–1871)

Hecker, Isaac Thomas (1819-1888)

Higginson, Thomas Wentworth (1823-1911)

Hoar, Elizabeth (1814-1878)

Hooper, Ellen Sturgis (1812-1848)

Ingraham, Cato (1751-1805)

James, Henry (1843-1916) — The American Scene: Concord

Japp, Alexander Hay (1837-1905)

Journals and Periodicals

- Æsthetic Papers

- The Atlantic Monthly

- The Dial: A Magazine for Literature, Philosophy, and Religion

Lane, Charles (1800-1870) — The Consociate Family Life

Langton, Jane (1922-2018) — Two Uncollected Talks: The Uses of New England Ecstasy • The War in Vietnam, the First Parish in Lincoln, Me, and Henry Thoreau

Lovejoy, Elijah Parish (1802-1837)

Lowell, James Russell (1819-1891)

Mac Donnell, Kevin — Collecting Henry David Thoreau by Kevin Mac Donnell

McCurdy, Michael (1942-2016) — Clear Sky, Pure Light: Encounters with Henry David Thoreau

Native Americans

- Henry Thoreau and John Muir Among the Indians by Richard F. Fleck (Archon Books, 1985; with errata and addendum, 2009)

- Selections from the “Indian Notebooks” (1847-1861) of Henry D. Thoreau , Transcribed, with an Introduction and additional material, by Richard F. Fleck

- The Liberator

- The New York Tribune

Peabody, Elizabeth Palmer (1804-1894)

PHOTOGRAPHY

- Gleason, Herbert Wendell (1855-1937) — Hebert W. Gleason Photographs (The Writings of Henry David Thoreau 1906)

- Hosmer, Alfred Winslow (1851-1903) — Alfred W. Hosmer Photographs

- Portfolio of Cartes de Visite

Pratt, Minot (1805-1878) — A Biographical Sketch of Minot Pratt by Ray Angelo

Ricketson, Daniel (1813-1898)

Ripley, Sophia (1803–1861) — Woman ( The Dial , January 1841)

Salt, Henry S. (1851-1939)

Sanborn, Franklin Benjamin (1831-1917)

Sattelmeyer, Robert — Thoreau’s Reading: A Study in Intellectual History With Bibliographical Catalogue

Shanley, J. Lyndon (1910-1996) — Transcription of the First Version of Walden

Stearns, Frank Preston (1846-1917) — Sketches from Concord and Appledore: An Excerpt

Thoreau, Helen (1812-1849)

John Thoreau & Co.

Thoreau, Sophia (1819-1876)

THOREAU, HENRY DAVID (1817-1862)

The Transcendental Log: A Digital Documentary Life & Times of the Transcendentalists

Very, Jones (1813-1880)

Ward, Samuel Gray (1817–1907)

Wheeler, Charles Stearns (1816-1843)

White, Zilpah (1738-1820)

Whitman, Walt (1819-1892)

Wilson, William Dexter (1816-1900)

Examining Transcendentalism through Popular Culture

- Resources & Preparation

- Instructional Plan

- Related Resources

After a brief introduction to the transcendentalist movement of the 1800s, students develop a working definition of transcendentalism by answering and discussing a series of questions about their own individualism and relationship to nature. Over the next few sessions, students read and discuss excerpts from Emerson's “Nature” and “Self-Reliance” and Thoreau's Walden . They use a graphic organizer to summarize the characteristics of transcendental thought as they read. Students then examine modern comic strips and songs to find evidence of transcendental thought. They gather additional examples on their own to share with the class. Finally, students complete the chart showing specific examples of transcendental thought from a variety of multimodal genres.

Featured Resources

Examining Transcendentalism through Popular Culture Final Project : Give this handout to students to guide them in their final project for this lesson. Examples of Transcendental Thought : Students can use this chart or the interactive version to record specific examples of transcendental thought in the texts they examine.

From Theory to Practice

In the article that inspired this lesson plan, Colleen A. Ruggieri explains, "As we English educators spend our days in the classroom, we want all of our students to come to love language as much as we do, even if they don't have a natural aptitude for the subject. We also want all of our students to be able to understand the material covered in class, as well as to see its relevance in the real world" (68). Ruggieri's technique of using comics and music to catch the interest of students work well to urge students to think more openly about the language and creative choices that an artist makes-whether a writer, a musician, or a comic strip author. Students are more willing to embrace the world of comic strips and the speaker of lyrics, especially when the songs and comics are left to students' own choice. Once they've identified concepts like transcendentalism in popular culture resources such as these, the relevance of texts by writers such as Emerson and Thoreau becomes simpler to establish.

Note: Because of the importance of this article to the lesson plan, the entire article has been made available. The article is protected by copyright and all rights are reserved. Further Reading

Common Core Standards

This resource has been aligned to the Common Core State Standards for states in which they have been adopted. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, CCSS alignments are forthcoming.

State Standards

This lesson has been aligned to standards in the following states. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, standard alignments are not currently available for that state.

NCTE/IRA National Standards for the English Language Arts

- 1. Students read a wide range of print and nonprint texts to build an understanding of texts, of themselves, and of the cultures of the United States and the world; to acquire new information; to respond to the needs and demands of society and the workplace; and for personal fulfillment. Among these texts are fiction and nonfiction, classic and contemporary works.

- 2. Students read a wide range of literature from many periods in many genres to build an understanding of the many dimensions (e.g., philosophical, ethical, aesthetic) of human experience.

- 3. Students apply a wide range of strategies to comprehend, interpret, evaluate, and appreciate texts. They draw on their prior experience, their interactions with other readers and writers, their knowledge of word meaning and of other texts, their word identification strategies, and their understanding of textual features (e.g., sound-letter correspondence, sentence structure, context, graphics).

- 8. Students use a variety of technological and information resources (e.g., libraries, databases, computer networks, video) to gather and synthesize information and to create and communicate knowledge.

Materials and Technology

- Songs demonstrating transcendental thought (and copies of lyrics)

- Excerpts from Emerson's " Self-Reliance " and " Nature "

- Excerpt from Thoreau's Walden

- Comic strips demonstrating transcendental thought (see the Comic Stip Collections booklist)

- Four to five CD players and/or MP3 players

- Headphones for students (optional)

- Student journals or looseleaf paper

- Examining Transcendentalism through Popular Culture Final Project

- Examining Transcendentalism through Popular Culture Final Project Rubric

- Examples of Transcendental Thought (optional instead of interactive)

Preparation