Your browser is out-of-date!

Internet Explorer 11 has been retired by Microsoft as of June 15, 2022. To get the best experience on this website, we recommend using a modern browser, such as Safari, Chrome or Edge.

What Is Transgender Affirming Surgery? (video)

Scripps plastic surgeon explains types of surgery and preparation.

Manish Champaneria, MD , a plastic surgeon at Scripps Clinic Del Mar and Scripps Clinic Rancho Bernardo explains the steps involved in preparing for gender confirmation surgery , and discusses male-to-female and female-to-male procedures.

Video transcript

How do you prepare for gender confirmation surgery.

First seek counsel with your endocrinologist or your family medicine doctor, as well as a mental health professional. That mental health professional can be a psychiatrist, a licensed social worker or a family medicine physician who specializes in mental health.

Once that’s done, then you visit with a surgeon who is capable and skilled in the art of transgender or gender confirmation surgery and take it from there.

What is top sex reassignment surgery?

Top sex reassignment surgery is also known as gender confirmation surgery. For our transgender male patients, that involves a mastectomy. For our transgender female patients, that means making a breast. And typically that’s a bilateral breast augmentation with implants or with fat.

What is transgender or gender confirmation plastic surgery?

Transgender surgery encompasses a lot of different types of surgery. It’s also known as gender confirmation surgery for our patients who are transitioning to become either male or female.

For patients who are transitioning to become female, that involves facial feminization. That means softening the contour of the face and giving a more feminine appearance. That also involves enhancing the breast with either an implant or with their own fat. For our patients who are becoming male, that involves a mastectomy where the breasts are removed and a masculinized chest is made.

Watch more Ask the Expert videos now for quick answers to common medical questions.

Related tags:

- Health and Wellness

Transgender surgery: Videos demonstrate cutting-edge techniques

- Aaron Grotas, MD

- Miroslav L. Djordjevic, MD, PhD

- Geolani W. Dy, MD

- Thomas J. Walsh, MD

- James M. Hotaling, MD, MS

In these videos, expert surgeons demonstrate robot-assisted penile inversion vaginoplasty, single-stage metoidioplasty, and simple orchiectomy for transgender patients.

Transgender surgery is a burgeoning field in urology and, with nearly 700,000 people in the United States alone identifying as transgender, this represents a significant unmet patient need. Although the field is new and encompasses both plastic surgery and urology, urologists are more familiar with the anatomy (both male and female) than any other specialty. Thus, they are uniquely positioned to play a key role in the surgical management of transgender patients. It is very likely that there will soon be transgender surgical fellowships in the future. Work by these surgeons and others will, hopefully, ensure that these fellowships remain within the purview of urology. Commentary on each video is provided by Lee Zhao, MD, assistant professor of urology at New York University Langone Medical Center, New York, and by 'Y'tube Section Editor James M. Hotaling, MD, MS, assistant professor of surgery (urology) at the Center for Reconstructive Urology and Men's Health, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Continue to the next page to watch the videos.

Vaginoplasty using penile and scrotal skin is performed for male-to-female transgender patients who desire genital reconstruction. However, short vaginal length, vaginal stenosis, or complications in the perineal dissection are limitations of current open techniques in vaginoplasty. We demonstrate our technique for the robot-assisted penile inversion vaginoplasty, for which the deep pelvic dissection is performed with robotic assistance, allowing for increased vaginal depth.

Dr. Hotaling: This video demonstrates how reconstructive surgeons trained in the robotic era are applying the tools and techniques of abdominal robotic surgery to gender confirmation surgery. Vaginal stenosis can be a devastating problem for patients undergoing male-to-female gender confirmation surgery. The approach described here, wherein Dr. Zhao performs a perineal dissection first and then uses the robot to ensure that the neovagina is appropriately developed, is a nice application of robotic surgery to reconstructive urology.

Lee Zhao, MD, is assistant professor of urology at New York University Langone Medical Center, New York.

Metoidioplasty is an operation to construct a phallus sufficient for voiding standing up in a transgender man. This operation is performed after a patient who was born female or intersex has undergone psychologic assessment and has decided to take male hormone (testosterone) to phenotypically match their identified gender male. Preoperative clitoral hypertrophy is essential to the success of achieving voiding while standing. This video reflects a variant of the operation because no laminectomy was performed at the patient's request. This technique would increase the risk of proximal fistula.

Dr. Zhao: This video describes how the hypertrophied clitoris can be transformed into a male-appearing phallic organ that allows for standing to void. For those in the audience that are unfamiliar with gender-affirming surgery, there are many similarities between metoidioplasty and proximal hypospadias repair. Division of the vaginal mucosa results in release of a “chordee,” and straightening of the clitoris. This division results in a gap between the native female urethra and the distal glans that is bridged by a tubularized flap of labia minora. The neourethral reconstruction is then buttressed by a flap of de-epithelialized labia minora. Reduction of mons pubis via monsplasty helps to accentuate the appearance of a prominent phallus.

Dr. Hotaling: Here, Dr. Grotas demonstrates how a hypertrophied clitoris can be reconstructed to allow a standing void. The most important take-home point of this video is how crucial the maintenance of proper anatomic planes is in reconstructive gender confirmation surgery. This allows the reconstruction of a neo-urethra from existing tissue.

David Shi, MD, is a urology resident and Aaron Grotas, MD, is clinical assistant professor of urology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Dr. Grotas is also the urologist at the Center of Transgender Medicine and Surgery at Mount Sinai. Miroslav L. Djordjevic, MD, PhD, is professor of urology and surgery at the School of Medicine, University of Belgrade, Serbia.

In this video, we demonstrate our technique and special considerations for orchiectomy in transgender patients. Principles include use of a vertical midline scrotal incision and maximal preservation of underlying tissue to facilitate potential future genital reconstruction.

Dr. Zhao: There are several psychologic and medical benefits of orchiectomy for male-to-female transgender patients. This video elegantly demonstrates how orchiectomy for gender affirmation differs from orchiectomy for oncologic purposes. For transgender patients, preservation of scrotal skin and Dartos is important as some patients will eventually undergo penile inversion vaginoplasty, in which the scrotal skin is used to line the neovagina, and the Dartos is used to add volume to the labia majora.

Dr. Hotaling: Here, Dr. Walsh and colleagues from the University of Washington demonstrate meticulous tissue handling and preservation of the anatomic planes during an orchiectomy for a male-to-female transgender patient. They show how optimal exposure allows a relatively high orchiectomy through a scrotal approach while preserving tissue for future reconstruction.

Geolani W. Dy, MD, is a fifth-year urology resident and Thomas J. Walsh, MD, MS, is associate professor of urology at the University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle.

Section Editor James M. Hotaling, MD, MS, is assistant professor of surgery (urology) at the Center for Reconstructive Urology and Men's Health, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

The urologist's role in dispelling men's health myths

“I think it's really important to understand the role of prevention and early detection,” says Michael Lutz, MD.

Investigators identify new target for VTE prevention

"This study identifies a new target for VTE prevention," writes Kate Gessner, MD, PhD, and Philip Abbosh, MD, PhD.

Destigmatizing Urology: Dr. Espinosa discusses lifestyle changes

“I think that the audience should know that there is a movement going on,” says Geo Espinosa, ND.

Study initiated to explore effect of oral TRT on spermatogenesis

The oral TRT study plans to enroll 20 male patients aged 18 to 49 years who meet the American Urological Association’s criteria for hypogonadism and who have not previously used TRT.

FDA grants IDE approval for study of vasectomy device

The study is set to begin in January 2024.

2 Commerce Drive Cranbury, NJ 08512

609-716-7777

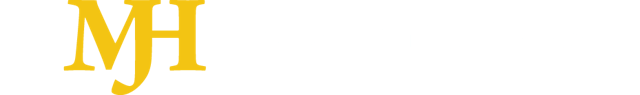

How Gender Reassignment Surgery Works (Infographic)

Bradley Manning, the U.S. Army private who was sentenced Aug. 21 to 35 years in a military prison for releasing highly sensitive U.S. military secrets, is seeking gender reassignment. Here’s how gender reassignment works:

Converting male anatomy to female anatomy requires removing the penis, reshaping genital tissue to appear more female and constructing a vagina.

An incision is made into the scrotum, and the flap of skin is pulled back. The testes are removed.

A shorter urethra is cut. The penis is removed, and the excess skin is used to create the labia and vagina.

People who have male-to-female gender-reassignment surgery retain a prostate. Following surgery, estrogen (a female hormone) will stimulate breast development, widen the hips, inhibit the growth of facial hair and slightly increase voice pitch.

Female-to-male surgery has achieved lesser success due to the difficulty of creating a functioning penis from the much smaller clitoral tissue available in the female genitals.

The uterus and the ovaries are removed. Genital reconstructive procedures (GRT) use either the clitoris, which is enlarged by hormones, or rely on free tissue grafts from the arm, the thigh or belly and an erectile prosthetic (phalloplasty).

Breasts need to be surgically altered if they are to look less feminine. This process involves removing breast tissue and excess skin, and reducing and properly positioning the nipples and areolae. Androgens (male hormones) will stimulate the development of facial and chest hair, and cause the voice to deepen.

Reliable statistics are extremely difficult to obtain. Many sexual-reassignment procedures are conducted in private facilities that are not subject to reporting requirements.

The cost for female-to-male reassignment can be more than $50,000. The cost for male-to-female reassignment can be $7,000 to $24,000.

Between 100 to 500 gender-reassignment procedures are conducted in the United States each year.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Man's years of premature ejaculation had a rare cause

Viagra alternatives? Study of mouse erections hints at new ways to treat erectile dysfunction

Scientists may have pinpointed the true origin of the Hope Diamond and other pristine gemstones

Most Popular

- 2 Explosive 'devil comet' 12P will soon be at its brightest and best. Here's how to see it before it disappears.

- 3 NASA's downed Ingenuity helicopter has a 'last gift' for humanity — but we'll have to go to Mars to get it

- 4 Giant, 82-foot lizard fish discovered on UK beach could be largest marine reptile ever found

- 5 Nightmare fish may explain how our 'fight or flight' response evolved

- 2 Giant, 82-foot lizard fish discovered on UK beach could be largest marine reptile ever found

- 3 What's the largest waterfall in the world?

- 4 Southern Grasshopper mouse: The tiny super-predator that howls at the moon before it kills

- 5 Rare 'porcelain gallbladder' found in 100-year-old unmarked grave at Mississippi mental asylum cemetery

Jump to content

American Urological Association

You are here, single port surgery (2012 svl), v2160: gender reassignment surgery. male to female. technique.

- Return to Course Home

- Return to Parent Home

Funding: none

Course navigation

You are not yet complete for this activity.

If you are attending a virtual event or viewing video content, you must meet the minimum participation requirement to proceed.

When the virtual event or video content is complete, please press "Next" again.

If you think this message was received in error, please contact an administrator.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

The New Girl in School: Transgender Surgery at 18

Rebirth of a transgender teenager, as katherine boone, 18, recovered from gender reassignment surgery, she and her family talked about what they went through..

It was not easy. For days afterward, she had dry heaves. She lost weight from her already frail frame. She did not seem empowered; she seemed regressed. “I just want to hold Emma,” she said in her darkened room at the bed and breakfast in New Hope, Pa., run by the doctor who performed the surgery in a hospital nearby. Emma is her black and white cat, at home outside Syracuse, N.Y., 200 miles away. Her childlike reaction was, perhaps, not surprising. Kat, whose side-parted hair was dyed fire engine red, is just 18, and about to graduate from high school. It is a transgender moment. President Obama was hailed just for saying the word “transgender” in his State of the Union speech this year, in a list of people who should not be discriminated against. They are characters in popular TV shows. Bruce Jenner’s transition from male sex symbol to a comely female named Caitlyn has elevated him back to his public profile as a gold-medal decathlete at the 1976 Summer Olympics.

By Anemona Hartocollis

- June 16, 2015

In a cozy cottage decorated with butterflies to symbolize transformation, Katherine Boone was recovering in April from the operation that had changed her, in the most intimate part of her body, from a biological male into a female.

It was not easy. She retched for days afterward. She could hardly eat. She did not seem empowered; she seemed regressed.

“I just want to hold Emma,” she said in her darkened room at the bed-and-breakfast in New Hope, Pa., run by the doctor who performed the operation in a hospital nearby. Emma is her black and white cat, at her home outside Syracuse in central New York State, 250 miles away.

Her childlike reaction was, perhaps, not surprising. Kat, whose side-parted hair was dyed a sassy red, is just 18, and about to graduate from high school.

It is a transgender moment. President Obama was hailed just for saying the word “transgender” in his State of the Union address this year, in a list of people who should not be discriminated against. They are characters in popular television shows. Bruce Jenner’s transition from male sex symbol to a comely female named Caitlyn has elevated her back to her public profile as a gold-medal decathlete at the 1976 Summer Olympics.

With growing tolerance, the question is no longer whether gender reassignment is an option but rather how young should it begin.

No law prohibits minors from receiving sex-change hormones or even surgery, but insurers, both private and public, have generally refused to extend coverage for these procedures to those under 18. In March, New York’s Medicaid drew a line at that age, and at 21 for some procedures.

But the number of teenagers going through gender reassignment has been growing amid wider acceptance of transgender identity, more parental comfort with the treatment and the emergence of a number of willing practitioners. Now advocates like Empire State Pride Agenda are fighting for coverage at an earlier age, beginning with hormone blockers at the onset of puberty, saying it is more seamless for a teenage boy to transition to becoming an adult woman, for example, if he does not first become a full-bodied man.

“Some of these women are passing, but barely, when they transition at 40 or 50,” said Dr. Irene Sills, an endocrinologist who just retired from a busy practice in the Syracuse area treating transgender children, including Kat. “At 16 or 17, you are going to have such an easier life with this.”

Given that there are no proven biological markers for what is known as gender dysphoria , however, there is no consensus in the medical community on the central question: whether teenagers, habitually trying on new identities and not known for foresight, should be granted an irreversible physical fix for what is still considered a psychological condition.

The debates invoke biology, ideology and emotion. Is gender dysphoria governed by a miswiring of the brain or by genetic coding? How much does it stem from the pressure to fit into society’s boxes — pink and dolls for girls, blue and sports for boys? Has the Internet liberated teenagers like Kat from a narrow view of how they should live their life, or has it seduced them by offering them, for the first time, an answer to their self-searching, an answer they might later choose to reject?

Some experts argue that the earlier the decision is made, the more treacherous, because it is impossible to predict which children will grow up to be transgender and which will not.

“Basically you have clinics working by the seat of the pants, making these decisions, and depending on which clinic you go to, you get a different response,” said Dr. Jack Drescher , a New York City psychiatrist and psychoanalyst who helped develop the latest diagnostic criteria for gender dysphoria.

On the other hand, Dr. Drescher said, “Is it fair to make a child who’s never going to change wait till 16 or 18 to get treatment?”

A Teenager’s Pain

Kat Boone did not fit the stereotype of a girl trapped in a boy’s body.

As a child, she dressed in jeans and shirts, like all the other boys, and her best friend was a boy. She liked to play with cars and slash bad guys in the Legend of Zelda video games. She still shuns dresses, preferring skinny jeans and band T-shirts.

But as a freshman in high school in Cazenovia, N.Y., she became depressed and withdrawn. “I knew that the changes going on with puberty were not me,” Kat said. “I started to really hate my life, myself. I was uncomfortable with my body, my voice, and I just felt like I was really a girl.”

When she discovered the transgender world on the Internet, she had a flash of recognition. “I was reading through some symptoms, not really symptoms, but some of the attributes of it did click,” she recalled.

It took a few months, but one night, she crept into her mother’s room and sat on the bed, crying. When she finally came out with what was bothering her, her mother’s first impulse was to comfort her, holding her hand and saying: “It’s O.K. It’s O.K.”

But inside, Gail Boone was terrified. She had wondered if her son was gay, and that, she says, would have been easier to deal with than a child who wanted to be the opposite sex.

“There’s this fear,” Ms. Boone said, “what is this going to do to my kid, what are people going to think, what are people going to think about me?”

Kat’s father, Andrew, had moved out when she was in fifth grade, and it took a few months for Kat and her mother to find the courage to tell him. Gail Boone had a background in psychology, which helped her understand. Mr. Boone, an operations and project manager, had a harder time, but was brought around for the sake of his child.

He read books about being transgender and raked his memory for clues in Kat’s early childhood, but could not find any. “Maybe she thinks this is the thing, and there’s something else going on,” he remembered thinking. “How do we know?” He wished there were something scientific like a blood test that would give him 100 percent certainty.

Mr. Boone recalls going into “a zombie trance,” a period of mourning for the child he thought he knew. “I was really eating myself up because I couldn’t help this overwhelming feeling as if my child had died,” he said. “But here was my child right in front of me.”

At 16 and a half, after seeing a therapist, Kat began taking estrogen and a blood pressure drug, spironolactone, that is also used to block the actions of testosterone, to help her look more female. In the fall of junior year, she showed up at school wanting to be called Katherine, or Kat, because she likes cats. She does not want anything to do with her birth name, Caden. She also has discovered that she likes girls. “I identify as a lesbian,” she said, though her attractions have not been reciprocated.

It was the cutting that convinced them that if she could not live as a girl, Kat would kill herself. She still has two angry scars on her left forearm. “It became clear to me that this wasn’t a passing phase or some choice or reaction,” Mr. Boone said. “This was truly the basis of what she was.”

Part of what brought her father around was the support network that has sprung up around transgender issues. In Syracuse, it is the Q (for queer or questioning) Center, run by the nonprofit ACR Health .

It is not easy to find. Visitors have to be buzzed in through an unmarked back door in a shabby neighborhood. But inside, it is homey, with a well-appointed library, a kitchen and a meeting room outfitted with beanbag chairs.

A meeting of teenagers in April began with each one declaring a name and pronoun of the day. Their choices were not always intuitively obvious. A young man with a scruffy beard and shaggy hair asked to be called Jackie and with the pronoun “she.”

“One of the nice things a trans person gets to do during transition is pick a new name,” said the facilitator, Mallory Livingston, a lawyer, “assigned male at birth,” now looking feminine in a tight pink camisole, black lace-up boots and miniskirt. “I went with the name of a character from my kids’ favorite movie, a strong female swordsperson.”

But there were hints of the pain the children had to endure. One child was required to use a separate bathroom at school, and a hidden camera was later found there.

Kat told the group that she was looking forward to surgery in six days. They clapped. “I’m scared,” she confessed.

A Young Movement

The ability to alter a child’s gender physically has never been greater.

But the drive to treat children is relatively new. One of the first and biggest hormone programs for young teenagers in the United States is led by a Harvard-affiliated pediatric endocrinologist, Dr. Norman Spack , at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Dr. Spack recalled being at a meeting in Europe about 15 years ago, when he learned that the Dutch were using puberty blockers in transgender early adolescents.

“I was salivating,” he recalled. “I said we had to do this.”

The puberty-blocking protocol gained legitimacy in 2009, when it was endorsed by the Endocrine Society, the leading association of hormone experts, on the recommendation of a task force including Dr. Spack.

The protocol calls for administering puberty-blocking drugs, generally Lupron, an injection, or histrelin, an implant, that are normally used to treat precocious puberty as well as prostate cancer and endometriosis, abnormal growth of uterine tissue.

The theory is that this drug-induced lull from about 12 to 16, sometimes younger, will help teenagers decide if they truly are transgender, without committing to irreversible physical changes. Puberty blockers are reversible. But in practice, some experts warn, once children have “socially transitioned” it is very difficult to go back.

If a psychological evaluation confirms gender dysphoria, teenagers are treated with cross-sex hormones (estrogen for boys, testosterone for girls), so they will, in effect, go through opposite-sex puberty. A consequence of going through the whole protocol is infertility.

The blockers cost thousands of dollars a year, and like all drugs used for transgender treatment, have not been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for that use, though they may be legally prescribed “off label.”

Dr. Spack said his clinic had treated about 200 children since 2007, and less than 20 percent had been covered by insurance. “That’s where the dilemma came in: Who the hell could afford it?” he said.

Doctors say that if children are started on puberty blockers young enough, insurance is less likely to question it. Some doctors have been able to drive the price down to $120 a month by getting the adult implant, which is much cheaper than the pediatric one, from sympathetic urologists and stretching it out over two years instead of just one.

While hormones for minors are sometimes covered by insurance, surgery almost never is. But several doctors said they had performed surgery on minors. Kat’s surgeon, Dr. Christine McGinn, estimated that she had done more than 30 operations on children under 18, about half of them vaginoplasties for biological boys becoming girls, and the other half double mastectomies for girls becoming boys.

“We’re trying to find the sweet spot,” Dr. McGinn said. “The problem is, it’s not an age, it’s a situation.”

Advocates say that extending treatment to teenagers will alleviate depression and suicide. With that in mind, Oregon’s Medicaid began covering the gamut of treatment, regardless of age, in January. Patients as young as 15 do not need parental consent.

The evidence is mixed. A large-scale Swedish study at the Karolinska Institute found that starting about a decade after gender reassignment surgery, transgender people were still more than 19 times as likely to die by suicide as the general population.

Complicating matters, studies suggest that most young children with gender dysphoria eventually lose any desire to change sex, and may grow up to be gay, rather than transgender. Once into adolescence, however, their dysphoria is more likely to stick.

Dr. Paul McHugh , a professor of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins University Medical School and its hospital’s former psychiatrist in chief, is skeptical of the use of surgery for a psychological condition, and even more so for children. “Bruce Jenner — who cares?” said Dr. McHugh, who said he played a role in closing a transgender surgery program at Johns Hopkins about 35 years ago. “He’s a wonderfully successful person. He’s got all kinds of social networks. He’s got plenty of money. No one’s objecting to him if he wants to live as a woman. This is America, be my guest.

“But we’re talking about children with a future ahead of them.”

A New Beginning

Kat went into the surgery on April 7 with high hopes.

Dr. McGinn was far from Cazenovia, in Lower Bucks Hospital in Pennsylvania. But Kat’s parents trusted her not only as a specialist, but also as a role model: She had been a dashing male doctor in the Navy, before becoming a beautiful female doctor in civilian life.

Kat had been accepted at Champlain College in Vermont, where she planned to use her artistic talent (she designed the rose tattoo on her shoulder) to study video game design. Her goal was to start college as a woman. Through luck — a cancellation — they were able to book a date during spring break, when Dr. McGinn’s calendar begins filling up with college-bound patients.

Gail Boone’s insurance plan initially denied coverage for the operation. A customer service agent told her genital reconstructive surgery was allowed only for conditions like birth defects. “You got it,” Ms. Boone retorted.

They prevailed.

It was too late to change some things, like Kat’s tenor voice and facial hair. “I hate my voice,” she said. “I shave.” She chose not to save sperm — to her, a revolting reminder of masculinity — so she cannot have children, the one sacrifice that gave her father a pang.

The operation involved deconstructing her male genitals and repurposing the nerves and skin as female anatomy.

When it was over, Kat developed aspiration pneumonia and had vomiting and dry heaves for days, normal reactions to anesthesia, narcotics and antibiotics, but Dr. McGinn said Kat was hit harder than most.

Before the surgery, she had been impish and playful. Now she buried her nose in her Nintendo 3DS and cracked a rare smile at an old text message consisting entirely of “Meow,” “Meow.”

Her father felt helpless as she refused food and lost about 20 pounds. Dr. McGinn said it was not unusual for patients to become depressed after surgery and compared this to postpartum depression.

Kat was anxious about having enough privacy in college, since her new vagina needs constant care or it will close off like a wound. “The only thing I’m thinking about now is the room situation,” she said.

Six weeks after the operation, she was still so weak that she had to take the elevator at school instead of the stairs.

At her two-month checkup, she had gained back half the weight she had lost, but still looked frail and self-conscious. She treated herself to a new hair color — strawberry blond — for graduation.

Kat said she had “zero regrets.”

But it was clear to all of them that the operation was not a quick fix.

It is not a “yippie, jump up and down fireworks situation,” Mr. Boone said. “It’s a grand relief that something that’s been such a bother to her is finally gone.”

Because of an editing error, an earlier version of this article erroneously attributed a distinction to New York’s Medicaid program. It is not the nation’s largest (the state with the largest Medicaid enrollment is California).

An earlier version of a picture caption with this article misstated the circumstances of Katherine Boone’s suicide threat. She cut herself when she was 17, not 16, and when she had already begun gender reassignment, not before.

How we handle corrections

Susan C. Beachy contributed research.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Dtsch Arztebl Int

- v.116(15); 2019 Apr

Quality of Life Following Male-To-Female Sex Reassignment Surgery

Géraldine weinforth.

1 Department of Plastic Surgery and Hand Surgery, Universitätsspital Zürich

Richard Fakin

Pietro giovanoli, david garcia nuñez.

2 Department of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery and Hand Surgery, Center for Gender Variance, Universitätsspital Basel

Associated Data

Additional points regarding the study method

We conducted a systematic key word guided literature search of four databases (PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, PsycINFO) in March 2017 in order to identify the current medical literature relating to our research question. Among the search terms we used were “transsexualism”, “reassignment surgery”, and “quality of life” ( etable 1 ). The article search was adapted to the technical requirements (for example, the option of using MeSH terms) of each database and undertaken by GW and DGN independently, supported by the recommendations summarized in the PRISMA statement ( 16 ).

Inclusion criteria

We included only articles that focused on the topic of the quality of life of trans women who had had sex reassignment surgery, independently of the studies’ population sizes and publication dates. GW, RF, and DGN operationalized the search terms by using an iterative process following the PICO method ( e1 ) ( etable 1 ) and a search string was created with these ( eTabelle 2 ) . The search for publications intentionally identified only studies reported in English or German.

Exclusion criteria

Studies that did not exclusively focus on trans persons (for example, LGBT [= lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender] studies) or that did not evaluate quality of life by using a standardized questionnaire were not considered. Furthermore, this review did not include review articles, published dissertations, nor congress presentations/commentaries. Studies of trans persons who were under age were excluded too.

Screening process

During the study selection process we excluded according to the mentioned criteria those studies that were not able to contribute to answering our research question ( figure ). Furthermore, we searched the reference lists of all selected articles in order to be able to include further studies that were not found in the databases. This yielded four additional studies that met the inclusion criteria. In a parallel and independent process, DGN checked the results of this search. In cases where discrepancies were found, a solution pertaining to the inclusion of the relevant study was found by consensus.

Study analysis

After the study selection process we viewed full-text articles and collated important key study data ( table 1 ). According to the definitions in the PICO scheme ( e1 ) we collated all relevant parameters from the individual studies in further full-text reviews. The first author extracted the data, and DGN checked these in a second, independent process. All included articles are non-randomized studies of evidence level III ( e2 ). Some studies ( 17 – 21 ) reported on the quality of life of trans women as well as trans men. In these cases we ensured that the data evaluation for trans women was done separately or the ratio M–F/F–M was in favor of trans women. Where information was lacking or lack of clarity existed in individual studies, we contacted the authors. Table 2 shows the quality characteristics of the included studies.

The prevalence of persons who are born with primary and secondary male sexual characteristics but feel that they are female (trans women) is ca. 5.48 per 100 000 males in Germany. In this article, we provide a detailed overview of the currently available data on quality of life after male-to-female sex reassignment surgery.

This review is based on publications retrieved by a systematic literature search that was carried out in the PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and PsycINFO databases in March 2017.

The 13 articles (11 quantitative and 2 mixed quantitative/qualitative studies) that were found to be suitable for inclusion in this review contained information on 1101 study participants. The number of trans women in each study ranged from 3 to 247. Their mean age was 39.9 years (range: 18–76). Seven different questionnaires were used to assess postoperative quality of life. The findings of the studies permit the conclusion that sex reassignment surgery beneficially affects emotional well-being, sexuality, and quality of life in general. In other categories (e.g., “freedom from pain”, “fitness”, and “energy”), some of the studies revealed worsening after the operation. All of the studies were judged to be at moderate to high risk of bias. The drop-out rates, insofar as they were given, ranged from 12% to 77% (median: 56%).

Current studies indicate that quality of life improves after sex reassignment surgery. The available studies are heterogeneous in design. In the future, prospective studies with standardized methods of assessing quality of life and with longer follow-up times would be desirable.

The term “gender incongruence” (GI) describes the situation in which a person does not identify with the gender they were assigned at birth on the basis of physical sexual characteristics and that they consequently experience “a marked and persistent incongruence between. .. experienced gender and the assigned sex” ( 1 ). The term trans women describes persons with congenital primary and secondary male sexual characteristics (assigned male at birth) who feel/identify as women. Trans men are persons who feel/identify as men but who have primary and secondary female sexual characteristics (assigned female at birth). Persons who fully identify with the sex/gender they were assigned at birth are known as cis women and cis men.

A data analysis from 2000 showed a prevalence in Germany of 4.26 trans persons/100 000 population (5.48 trans women/100 000 of the male population and 3.12 trans men/100 000 of the female population) ( 2 ). We are not aware of any more recent data for Germany.

If persons with gender incongruence develop clinically relevant biopsychosocial suffering, they have gender dysphoria (GD), according to the DSM-5 classification ( 3 ). For many trans persons, physical transition is the best option for alleviating the symptoms of gender dysphoria ( 4 ). Sex/gender reassignment hormone treatment as well as surgery have a central role in this setting ( 5 ). The latter comprise surgical procedures involving the genitals (sex reassignment surgery) ( box ), the breasts, and the face and vocal cords, as well as hair epilation ( 6 ).

Principle of male-to-female sex reassignment surgery

- Bilateral orchiectomy

- Preparation of the glans (head) of the penis with the complete neurovascular bundle

- Preparation of the urethra

- Subtotal resection of the cavernous bodies (corpora cavernosa) and the corpus spongiosum of the penis

- Preparation of the neovaginal space in the perineal area between rectum and urethra/bladder

- Penile inversion vaginoplasty (pedicle flap from the skin of the penal shaft: gold standard)

- If required, use of free split-thickness skin grafts

- In selected cases, this is the primary indication—for example, in trans women with penoscrotal hypoplasia or at the patient’s wish (for better natural secretion).

- This procedure can also be used as a secondary intervention in patients after unsatisfactory penile inversion vaginoplasty.

- Construction of a neo-clitoris from the glans (head) of the penis

- Construction of a urethral neo-meatus after urethral shortening as required

- Construction of labia from the remaining scrotal skin, possibly also labia minora

A US study showed that from 2000 to 2011, the rate of surgical sex reassignment measures among trans persons rose from 72% to 83.9% ( 7 ). These data move the question of the effectiveness of such operations increasingly into the focus of clinical attention and awareness ( 8 – 11 ).

In the context of evidence-based medicine, the consensus is now that the success of medical procedures should not be studied merely in terms of objective results (survival and complication rates, measurements of functionality, etc), but that patients’ personal wellbeing should be included in assessing the success of any procedure ( 12 , 13 ). Review articles to date have shown that sex reassignment hormone treatment has a positive effect on the quality of life of trans persons ( 14 , 15 ). By contrast, an overall assessment of quality of life after sex reassignment surgery is so far lacking. In this article we will attempt to provide a review of current studies, and on this basis we will investigate the question of quality of life after sex reassignment surgery.

For the review to be as representative as possible, this article deals with trans women only, whose incidence is notably higher than that of trans men (0.41 male to female/100 000 total male population in Germany and 0.26 female to male/100 000 total female population in Germany) ( 2 ).

We conducted as systematic literature search in PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and PsycINFO in March 2017. GW and DGN independently undertook the article search on the basis of the recommendations summarized in the PRISMA statement ( 16 ). Details of the methods are described in the eMethods section.

We included only articles on the subject of the quality of life of trans women after sex reassignment surgery. GW, RF, and DGN operationalized ( etable 1 ) the search terms in an iterative process according to the PICO method ( e1 ) and set out a search string ( etable 2 ).

* Key words used in accordance with the PI(C)O method

* Catch phrases and key words used in the literature search

Among others, we excluded studies that did not focus exclusively on trans persons or that didn’t collect data on quality of life by using a standardized questionnaire. We also excluded studies in underage trans people.

The Figure shows the study selection process.

Flow chart illustrating the study selection process

All included articles are non-randomized studies with an evidence level of III ( e2 ). In the case of studies that reported on the quality of life of trans women as well as trans men ( 17 – 21 ) we ensured that the data for trans women were evaluated separately or that the ratio of M–F/F–M favored trans women. Table 1 shows further key study data; Table 2 shows the quality characteristics of the studies.

* 1 Numbers of study participants after removal of dropouts ( table 2 ); exception: Lindqvist et al. ( 23 ), see Table 2

* 2 M–F, male-to-female; F–M, female to male, sex reassignment surgery

* 1 M–F male to female; F–M female to male, reassignment surgery

* 2 Prospective study design

* 3 Of originally 190 participants, n = 160 (84.21%) completed the questionnaire preoperatively and n = 47 (24.73%) postoperatively

* 4 Out of a total of 190 study participants, n = 146 (76.84%) completed the questionnaire preoperatively, n = 108 (56.84%) 1 year postoperatively, n = 64 (33.68%) 3 years postoperatively, and n = 43 (22,63%) 5 years postoperatively. Most of the 190 participants completed the questionnaire at least at two follow-up points.

The studies made use of the following instruments:

- 6 studies used the Short Form 36 Health Survey (SF-36) ( 18 , 20 , 22 – 25 );

- 2 studies used the World Health Organization’s Quality of Life 100 questionnaire (WHOQOL-100) ( 17 , 26 );

- 2 studies used the Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS) in combination with the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) and the Cantrils Ladder of Life Scale (CLLS) ( 27 , 28 );

- 2 studies used the FLZ questionnaire ( Fragebogen zur Lebenszufriedenheit ) ( 21 , 29 ); and

- 1 study used the King’s Health Questionnaire (KHQ) ( 19 ).

None of the questionnaires constitutes an investigative tool that is specifically tailored to trans persons. Table 3 shows the result scales. Table 2 shows the confounding variables and, as far as it is possible to assess this, the risk of bias.

*For the studies referenced in parentheses, it was not possible to calculate effect sizes

Quality of life

The SF-36 and WHOQOL-100 are validated, reliable and disease–non-specific instruments for measuring health-related quality of life ( 30 , 31 ). They can be used to gain information on the individual health status and allow for observing disease-related stresses over time. The questionnaires collect data on numerous aspects of daily life, which in their totality reflect quality of life. They are used internationally and therefore make cross-cultural studies an option ( 32 ).

Studies that used the SF-36 to answer the question of postoperative quality of life ( 18 , 20 , 22 – 25 ) observed after sex reassignment surgery an improvement in “social functioning”, “physical” and “emotional role functioning”, “general health perceptions”, “vitality”, and “mental health” (p = 0.025 to p >0.05). In two of these studies ( 22 , 24 ), “mental health” in trans women after sex reassignment surgery did not differ significantly from the standard sample. This explains the formally non-significant result. Ainsworth and Spiegel ( 22 ) showed that trans women without surgical intervention when compared indirectly with cis women from the SF-36 standard sample reported significantly poorer “mental health” (39.5 vs 48.9; p <0.05). Lindqvist et al. ( 23 ) and Weyers et al. ( 24 ) found an improvement in “self-perceived health” in the first postoperative year (p <0.05 and p <0.009), which deteriorated later but did not fall as low as its original score (p <0.0001). Furthermore, the studies concluded that “physical pain” increased postoperatively and “physical functioning” decreased; the postoperative follow-up periods varied between 3 months ( 18 ) and 5 years ( 23 ). According to Lindqvist et al. ( 23 ), “physical pain” in trans women five years postoperatively was comparable to that in the standard population (72.5 vs 72.7; SD 26.5).

Studies that used the WHOQOL-100 came up with the following results: Cardoso da Silva et al. ( 26 ) observed postoperatively an increase in “sexual activity” (p = 0.000) compared with the preoperative evaluation (prospective study design). Furthermore they found a postoperative improvement in the “psychological domain” (p = 0.041) and “social relationships” (p = 0.007), but a deterioration in “physical health” (p = 0.002) and “independence” (p = 0.031). Accordingly, deteriorations were seen in the areas of “energy” and “fatigue”, “sleep”, “negative feelings”, “mobility”, and “activities of daily living” (p <0.05). Castellano et al. ( 17 ) found after sex reassignment surgery for the group of trans women compared with the group of cis women no significant differences relating to “sexual activity” (65.85 vs 66.28; p >0.05), “body image” (64.64 vs 65.47; p >0.05), and the “quality of life score” (67.87 vs 69.49; p >0.05).

Quality of life and urinary incontinence

The King’s Health Questionnaire (KHQ) is a validated questionnaire for evaluating the impact of urinary incontinence on quality of life ( 33 ), a topic of central importance for trans persons ( 34 ). This questionnaire interrogates the quality of life domains always in association with urinary incontinence as the main problem. Kuhn et al. ( 19 ) showed that “general health” in trans persons was experienced as poorer to a relevant extent (Cohen’s d = 4.126; p = 0.019), and “physical” (d = -7.972; p <0.0001) and “personal limitations” (d = -7.016; p <0.001) were experienced to a greater extent. In contrast to this, trans persons felt less limited in terms of “role limitation” (d = 3.311; p = 0.046). For “emotions”, “sleep”, “incontinence”, and “symptom severity”, the differences to the control group did not reach significance. The control group consisted of cis women who had undergone abdominopelvic surgery. The evaluation of the visual analogue scale (VAS) showed a lower (d = 14.136; p <0.0001) degree of general life satisfaction in the group of trans persons.

Life satisfaction

The SHS ( 35 ), SWLS ( 36 ), and CLLS ( 37 ) are validated and internationally used visual analogue scales to evaluate life satisfaction. The SHS evaluates individual happiness and associated physical, mental, and social wellbeing ( 35 ). The SWLS was used as a short-form scale in the cited studies (also known as L-1) and included only the question on general life satisfaction ( 36 ). The CLLS evaluates emotional wellbeing associated with life satisfaction as well as subjective health ( 37 ).

Studies that used the SHS, SWLS, and CLLS ( 27 , 28 ) to evaluate postoperative life satisfaction reported a high degree of “subjective happiness” (5.6; SD 1.4 and 5.9; SD 0.6), of “satisfaction with life“ (27.7; SD 5.8 and 27.1; SD 2.1) and “subjective wellbeing” (8.0 [range: 4–10] and 7.9; SD 0.7) in trans women after intestinal vaginoplasty. The studies cited earlier differ with regard to the following items: Bouman et al. ( 27 ) studied a population of young trans women (mean age: 19.1 years) with penoscrotal hypoplasia after primary laparoscopic intestinal vaginoplasty. The study participants had received puberty blockers during their transition therapy, which resulted in penoscrotal hypoplasia and made penile inversion vaginoplasty ( box ) impossible. Van der Sluis et al. ( 28 ) studied an older population (mean age: 58 years) of trans women after secondary intestinal vaginoplasty—that is, patients who required secondary intestinal reconstruction owing to vaginal stenosis or insufficient vaginal length after penile inversion vaginoplasty. The postoperative follow-up period varied between 1–7.5 years ( 27 ) and 17.2–34.3 years ( 28 ). In spite of the different patient populations, these studies found that sex reassignment surgery had a positive effect on life satisfaction.

The FLZ is a validated multidimensional questionnaire for evaluating individual general life satisfaction ( 38 ). It is used in life quality and rehabilitation research and enables the recording of changes if administered repeatedly. It is available in a German language version only; for this reason, its results apply only to German speaking populations.

Studies that used the FLZ questionnaire ( 21 , 29 ) found that the postoperative life satisfaction of trans women in terms of “health” does not differ from that of the general population. Additionally, Papadopoulos et al. ( 29 ) found no differences for “friends”, “hobbies”, “income”, “work”, and “relationship.” A subanalysis of the module “health” found postoperatively in both studies a relevant decrease in “fitness” (d = 0.521; p <0.001) and “energy” (d = 0.494; p <0.003). Zimmerman et al. ( 21 ) additionally found a significant decrease in “ability to relax/equilibrium” (p = 0.002), “fearlessness/absence of anxiety” (p = 0.015), and “absence of discomfort/pain” (p = 0.037). Both studies ( 21 , 29 ) were retrospective surveys that were undertaken once only in a time period between 6 months and 58 months postoperatively. Papadopoulos et al. ( 29 ) included only subjects into the study who did not require any further corrective surgery after sex reassignment surgery or who had already undergone a second procedure for the purpose of minor corrections.

Two prospective studies documented postoperatively a notable improvement in quality of life ( 23 , 26 ). Four studies found that the life quality of trans women after sex reassignment surgery was no different from that of cis women ( 17 , 20 , 22 , 24 ). Sex reassignment surgery has also been shown to have a positive effect on life satisfaction ( 27 , 28 )—the exception was urinary incontinence, in which case life satisfaction dropped ( 19 ). Lindqvist et al. ( 23 ) and Weyers et al. ( 24 ) observed an improvement in self-perceived health in the first postoperative year, which then drops, albeit not all the way down to its original level. This is consistent with the honeymoon phase described by De Cuypere et al. ( 39 ), which has been described as a euphoric period in the first year after surgery. Several studies ( 18 , 20 – 25 ) showed that physical pain increased after surgery and physical functioning deteriorated. This is easily explained by the surgery itself, however; the postoperative follow-up periods in these studies varied between 3 months ( 18 ) and 5 years ( 23 ).

Altogether the study results imply that sex reassignment surgery has an overall positive effect on partial aspects, such as mental health, sexuality, life satisfaction, and quality of life.

These results were confirmed by Barone et al. ( 40 ) and Murad et al. ( 15 ) in their review articles, which were published in 2017 and 2010, respectively. Barone et al. ( 40 ) in a systematic review evaluated patient reported results after sex reassignment surgery; among others, regarding life satisfaction. Murad et al. ( 15 ) in a meta-analysis focused on quality of life and psychosocial health after hormone therapy (main aspect) and sex reassignment surgery. In sum, both studies found improvements in quality of life and life satisfaction after sex reassignment surgery, and an improvement at the psychosocial level. Hess et al. ( 11 ) concluded that the study participants benefited from sex reassignment surgery—they too found high rates of satisfaction postoperatively in Germany.

As sex reassignment surgery often constitutes the final step of sex reassignment measures, hormone therapy as well as accompanying psychotherapy may have had a confounding effect. Not all studies adjusted for confounding factors. A lack of randomization and control or the use of a matched control group ( 17 , 19 ) in the studies also introduced methodological bias ( table 2 ). Furthermore, the high dropout rates of 12% ( 17 ) to 77% ( 23 ) (median: 56%), which are mainly due to non-respondents, should be assessed critically. In our experience, however, the patient population of trans women is often reticent and is not interested in study participation because of personal reasons (“to not be reminded of that time”). Other authors have shared this observation ( 18 , 24 ), which may also explain the occasionally high dropout rates. There is also the possibility that dissatisfied patients were among the dropouts. Owing to socioeconomic and clinical conditions, the studies from Croatia ( 18 ) and China ( 25 ) need to be evaluated separately. On the one hand, the authors of both studies draw attention to the public’s lack of awareness and understanding (and the associated psychological stress for trans women) in these countries, and, on the other hand, statutory sickness funds did not cover the costs of all treatments, which were therefore accessible to only few patients. This explains the notably lower participant numbers of 3 ( 18 ) and 4 ( 25 ) male-to-female transitions after sex reassignment surgery. None of the included studies reported potential suicide rates.

The strength of this review lies in the fact that we included only studies that used standardized questionnaires. Tests (such as the SF-36 or WHOQOL-100) represent validated and reliable measuring instruments, for some of which reference standard populations exist, and they enable international and intercultural comparison. Furthermore, standardized questionnaires have the advantage of a high degree of objectivity in terms of conducting, evaluating, and interpreting studies.

The available study data show that sex reassignment surgery has a positive effect on partial aspects—such as mental health/wellbeing, sexuality, and life satisfaction—as well as on quality of life overall.

It should be noted that the studies are almost exclusively retrospective analyses of mostly uncontrolled and small cohorts, for which no valid or specific measuring instruments are available to date. Because of the high dropout and non-response rates, the current data should be interpreted with caution.

In spite of the essentially positive results, the data are not satisfactory at this point in time. Due to the studies’ limited follow-up times, no conclusions can be drawn as yet about the long term consequences of such procedures. Furthermore, many studies did not use standardized questionnaires and/or scores, which makes comparisons between individual studies difficult.

Key messages

- Trans persons suffer from the tension between their biologically characterized body and their experienced sex/gender.

- Undergoing medical and/or social transition seems for many trans persons the best possible solution for alleviating their gender dysphoria symptoms.

- Results from studies imply that sex reassignment surgery on the one hand has positive effects in terms of partial aspects of quality of life, such as mental health, sexuality, and life satisfaction, and, on the other hand, on quality of life overall.

- Because of the studies’ high dropout rates (12–77%; median 56%), the results should be interpreted with caution.

- The studies did not include information on potential suicide rates.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

Translated from the original German by Birte Twisselmann, PhD.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

Trends and Techniques in Gender Affirmation Surgery: Is YouTube an Effective Patient Resource?

Affiliations.

- 1 Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery.

- 2 Division of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery.

- 3 Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Rutgers-New Jersey Medical School.

- PMID: 32221268

- DOI: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000006695

- Counseling / standards

- Gender Dysphoria / surgery*

- Information Dissemination / methods

- Information Seeking Behavior

- Marketing of Health Services / statistics & numerical data

- Patient Education as Topic / standards*

- Patient Education as Topic / statistics & numerical data

- Prejudice / psychology

- Prejudice / statistics & numerical data

- Sex Reassignment Surgery / methods

- Sex Reassignment Surgery / trends*

- Social Media / standards

- Social Media / statistics & numerical data*

- Transgender Persons / psychology*

- Transgender Persons / statistics & numerical data

- Video Recording / statistics & numerical data

Dr. Alter’s Before and After IMAGE GALLERY

Female procedures.

LABIAPLASTY (Labia Minora Reduction)

CLITORAL HOOD REDUCTION WITH/WITHOUT CLITOROPEXY

LABIA MAJORA REMODELING

COMBINATION FEMALE GENITAL SURGERIES

REVISION OF BOTCHED LABIAPLASTIES

CLITORIS REDUCTION

PUBIC LIPOSUCTION

PUBIC MONS LIFT

INTERSEX & COMPLEX FEMALE RECONSTRUCTION

Male procedures.

BURIED/HIDDEN PENIS CORRECTIVE SURGERY – ADULT

Buried/hidden penis corrective surgery – child, penoscrotal webbing, scrotum reduction, male genital reconstruction, penis enlargement reconstruction, congenital penile curvature, gender confirmation procedures.

MALE TO FEMALE GENDER CONFIRMATION SURGERY

MALE-TO-FEMALE SEX REASSIGNMENT REVISIONS

Female-to-male chest contouring, female to male metaidoioplasty, gender confirmation breast augmentations, cosmetic procedures.

ABDOMINOPLASTY

Breast augmentation, breast reconstruction & breast reduction, liposuction, patient-first policy.

Dr. Alter and the entire team are dedicated to providing every patient with exceptional individualized care—from consultation to recovery. We take the time to learn about your concerns, goals, and desires, so we can build a plan that addresses your concerns and gets you the results you deserve.

Thoughts & Insights

5 Labiaplasty Benefits You Should Know About

Is Your Penis Curved? How Much Is Too Much?

Have You Thought About Your Sexual Wellness Today?

Top Vaginal Rejuvenation Treatments for Moms

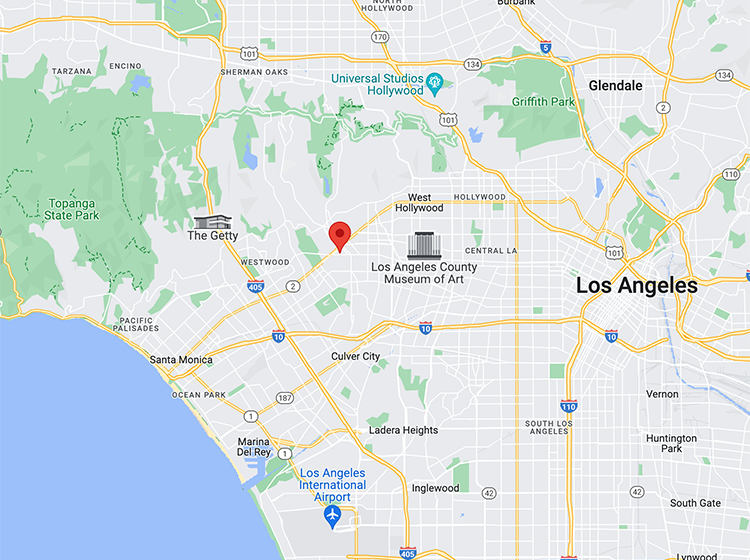

Our locations.

BEVERLY HILLS

NEW YORK CITY

Sweden passes law to make it easier to change legal gender

- Medium Text

Sign up here.

Reporting by Johan Ahlander

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles. New Tab , opens new tab

World Chevron

A coalition vessel successfully engaged one anti-ship ballistic missile (ASBM) launched from the Iranian-backed Houthi "terrorist-controlled areas" in Yemen over the Gulf of Aden, the U.S. Central Command (USCENTCOM) said on Thursday.

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, male-to-female gender-affirming surgery: 20-year review of technique and surgical results.

- 1 Serviço de Urologia, Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre, Brazil

- 2 Serviço de Psiquiatria, Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre, Brazil

- 3 Serviço de Psiquiatria, Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil

Purpose: Gender dysphoria (GD) is an incompatibility between biological sex and personal gender identity; individuals harbor an unalterable conviction that they were born in the wrong body, which causes personal suffering. In this context, surgery is imperative to achieve a successful gender transition and plays a key role in alleviating the associated psychological discomfort. In the current study, a retrospective cohort, we report the 20-years outcomes of the gender-affirming surgery performed at a single Brazilian university center, examining demographic data, intra and postoperative complications. During this period, 214 patients underwent penile inversion vaginoplasty.

Results: Results demonstrate that the average age at the time of surgery was 32.2 years (range, 18–61 years); the average of operative time was 3.3 h (range 2–5 h); the average duration of hormone therapy before surgery was 12 years (range 1–39). The most commons minor postoperative complications were granulation tissue (20.5 percent) and introital stricture of the neovagina (15.4 percent) and the major complications included urethral meatus stenosis (20.5 percent) and hematoma/excessive bleeding (8.9 percent). A total of 36 patients (16.8 percent) underwent some form of reoperation. One hundred eighty-one (85 percent) patients in our series were able to have regular sexual intercourse, and no individual regretted having undergone GAS.

Conclusions: Findings confirm that it is a safety procedure, with a low incidence of serious complications. Otherwise, in our series, there were a high level of functionality of the neovagina, as well as subjective personal satisfaction.

Introduction

Transsexualism (ICD-10) or Gender Dysphoria (GD) (DSM-5) is characterized by intense and persistent cross-gender identification which influences several aspects of behavior ( 1 ). The terms describe a situation where an individual's gender identity differs from external sexual anatomy at birth ( 1 ). Gender identity-affirming care, for those who desire, can include hormone therapy and affirming surgeries, as well as other procedures such as hair removal or speech therapy ( 1 ).

Since 1998, the Gender Identity Program (PROTIG) of the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (HCPA), Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil has provided public assistance to transsexual people, is the first one in Brazil and one of the pioneers in South America. Our program offers psychosocial support, health care, and guidance to families, and refers individuals for gender-affirming surgery (GAS) when indicated. To be eligible for this surgery, transsexual individuals must have been adherent to multidisciplinary follow-up for at least 2 years, have a minimum age of 21 years (required for surgical procedures of this nature), have a positive psychiatric or psychological report, and have a diagnosis of GD.

Gender-affirming surgery (GAS) is increasingly recognized as a therapeutic intervention and a medical necessity, with growing societal acceptance ( 2 ). At our institution, we perform the classic penile inversion vaginoplasty (PIV), with an inverted penis skin flap used as the lining for the neovagina. Studies have demonstrated that GAS for the management of GD can promote improvements in mental health and social relationships for these patients ( 2 – 5 ). It is therefore imperative to understand and establish best practice techniques for this patient population ( 2 ). Although there are several studies reporting the safety and efficacy of gender-affirming surgery by penile inversion vaginoplasty, we present the largest South-American cohort to date, examining demographic data, intra and postoperative complications.

Patients and Methods

Subjects and study setup.

This is a retrospective cohort study of Brazilian transgender women who underwent penile inversion vaginoplasty between January of 2000 and March of 2020 at the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre, Brazil. The study was approved by our institutional medical and research ethics committee.

At our institution, gender-affirming surgery is indicated for transgender women who are under assistance by our program for transsexual individuals. All transsexual women included in this study had at least 2 years of experience as a woman and met WPATH standards for GAS ( 1 ). Patients were submitted to biweekly group meetings and monthly individual therapy.

Between January of 2000 and March of 2020, a total of 214 patients underwent penile inversion vaginoplasty. The surgical procedures were performed by two separate staff members, mostly assisted by residents. A retrospective chart review was conducted recording patient demographics, intraoperative and postoperative complications, reoperations, and secondary surgical procedures. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Hormonal Therapy

The goal of feminizing hormone therapy is the development of female secondary sex characteristics, and suppression/minimization of male secondary sex characteristics.

Our general therapy approach is to combine an estrogen with an androgen blocker. The usual estrogen is the oral preparation of estradiol (17-beta estradiol), starting at a dose of 2 mg/day until the maximum dosage of 8 mg/day. The preferred androgen blocker is spironolactone at a dose of 200 mg twice a day.

Operative Technique

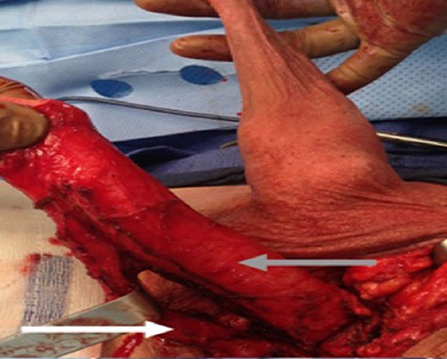

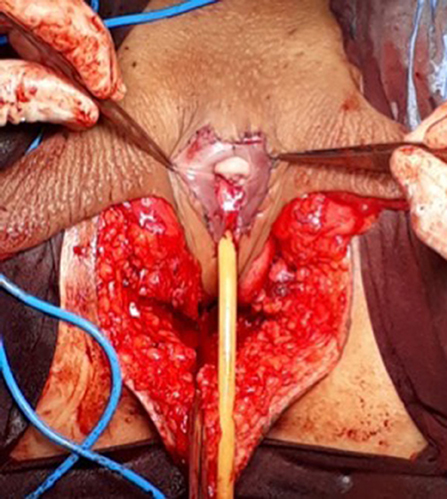

At our institution, we perform the classic penile inversion vaginoplasty, with an inverted penis skin flap used as the lining for the neovagina. For more details, we have previously published our technique with a step-by-step procedure video ( 6 ). All individuals underwent intestinal cleansing the evening before the surgery. A first-generation cephalosporin was used as preoperative prophylaxis. The procedure was performed with the patient in a dorsal lithotomy position. A Foley catheter was placed for bladder catheterization. A inverted-V incision was made 4 cm above the anus and a flap was created. A neovaginal cavity was created between the prostate and the rectum with blunt dissection, in the Denonvilliers space, until the peritoneal fold, usually measuring 12 cm in extension and 6 cm in width. The incision was then extended vertically to expose the testicles and the spermatic cords, which were removed at the level of the external inguinal rings. A circumferential subcoronal incision was made ( Figure 1 ), the penis was de-gloved and a skin flap was created, with the de-gloved penis being passed through the scrotal opening ( Figure 2 ). The dorsal part of the glans and its neurovascular bundle were bluntly dissected away from the penile shaft ( Figure 3 ) as well as the urethra, which included a portion of the bulbospongious muscle ( Figure 4 ). The corpora cavernosa was excised up to their attachments at the symphysis pubis and ligated. The neoclitoris was shaped and positioned in the midline at the level of the symphysis pubis and sutured using interrupted 5-0 absorbable suture. The corpus spongiosum was reduced and the urethra was shortened, spatulated, and placed 1 cm below the neoclitoris in the midline and sutured using interrupted 4-0 absorbable suture. The penile skin flap was inverted and pulled into the neovaginal cavity to become its walls ( Figure 5 ). The excess of skin was then removed, and the subcutaneous tissue and the skin were closed using continuous 3-0 non-absorbable suture ( Figure 6 ). A neo mons pubis was created using a 0 absorbable suture between the skin and the pubic bone. The skin flap was fixed to the pubic bone using a 0 absorbable suture. A gauze impregnated with Vaseline and antibiotic ointment was left inside the neovagina, and a customized compressive bandage was applied ( Figure 7 —shows the final appearance after the completion of the procedures).

Figure 1 . The initial circumferential subcoronal incision.

Figure 2 . The de-gloved penis being passed through the scrotal opening.

Figure 3 . The dorsal part of the glans and its neurovascular bundle dissected away from the penile shaft.

Figure 4 . The urethra dissected including a portion of the bulbospongious muscle. The grey arrow shows the penile shaft and the white arrow shows the dissected urethra.

Figure 5 . The inverted penile skin flap.

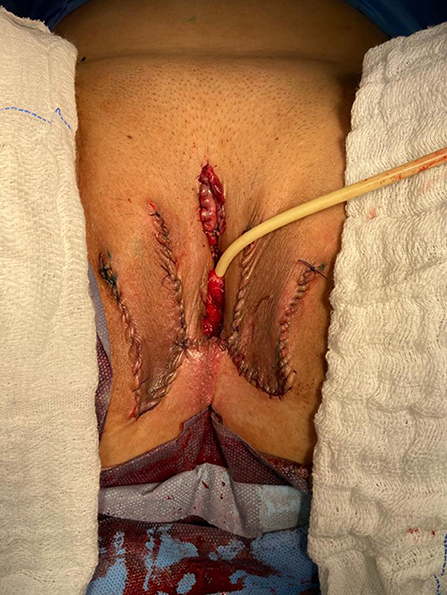

Figure 6 . The neoclitoris and the urethra sutured in the midline and the neovaginal cavity.

Figure 7 . The final appearance after the completion of the procedures.

Postoperative Care and Follow-Up

The patients were usually discharged within 2 days after surgery with the Foley catheter and vaginal gauze packing in place, which were removed after 7 days in an ambulatorial attendance.

Our vaginal dilation protocol starts seven days after surgery: a kit of 6 silicone dilators with progressive diameter (1.1–4 cm) and length (6.5–14.5 cm) is used; dilation is done progressively from the smallest dilator; each size should be kept in place for 5 min until the largest possible size, which is kept for 3 h during the day and during the night (sleep), if possible. The process is performed daily for the first 3 months and continued until the patient has regular sexual intercourse.

The follow-up visits were performed 7 days, 1, 2, 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery ( Figure 8 ), and included physical examination and a quality-of-life questionnaire.

Figure 8 . Appearance after 1 month of the procedure.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted using Statistical Product and Service Solutions Version 18.0 (SPSS). Outcome measures were intra-operative and postoperative complications, re-operations. Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate the study outcomes. Mean values and standard deviations or median values and ranges are presented as continuous variables. Frequencies and percentages are reported for dichotomous and ordinal variables.

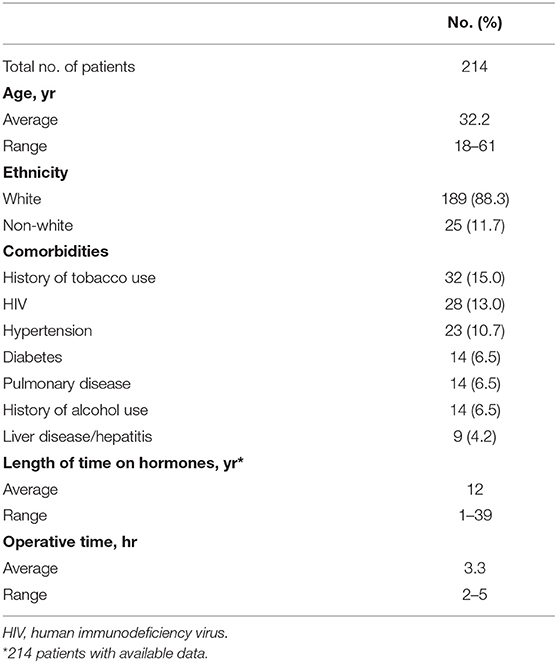

Patient Demographics

During the period of the study, 214 patients underwent penile inversion vaginoplasty, performed by two staff surgeons, mostly assisted by residents ( Table 1 ). The average age at the time of surgery was 32.2 years (range 18–61 years). There was no significant increase or decrease in the ages of patients who underwent SRS over the study period (Fisher's exact test: P = 0.065; chi-square test: X 2 = 5.15; GL = 6; P = 0.525). The average of operative time was 3.3 h (range 2–5 h). The average duration of hormone therapy before surgery was 12 years (range 1–39). The majority of patients were white (88.3 percent). The most prevalent patient comorbidities were history of tobacco use (15 percent), human immunodeficiency virus infection (13 percent) and hypertension (10.7 percent). Other comorbidities are listed in Table 1 .

Table 1 . Patient demographics.

Multidisciplinary follow-up was comprised of 93.45% of patients following up with a urologist and 59.06% of patients continuing psychiatric follow-up, median follow-up time of 16 and 9.3 months after surgery, respectively.

Postoperative Results

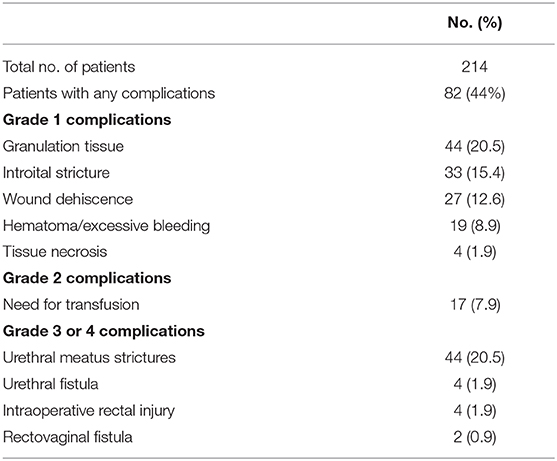

The complications were classified according to the Clavien-Dindo score ( Table 2 ). The most common minor postoperative complications (Grade I) were granulation tissue (20.5 percent), introital stricture of the neovagina (15.4 percent) and wound dehiscence (12.6 percent). The major complications (Grade III-IV) included urethral stenosis (20.5 percent), urethral fistula (1.9 percent), intraoperative rectal injury (1.9 percent), necrosis (primarily along the wound edges) (1.4 percent), and rectovaginal fistula (0.9 percent). A total of 17 patients required blood transfusion (7.9 percent).

Table 2 . Complications after penile inversion vaginoplasty.

A total of 36 patients (16.8 percent) underwent some form of reoperation.

One hundred eighty-one (85 percent) patients in our series were able to have regular sexual vaginal intercourse, and no individual regretted having undergone GAS.

Penile inversion vaginoplasty is the gold-standard in gender-affirming surgery. It has good functional outcomes, and studies have demonstrated adequate vaginal depths ( 3 ). It is recognized not only as a cosmetic procedure, but as a therapeutic intervention and a medical necessity ( 2 ). We present the largest South-American cohort to date, examining demographic data, intra and postoperative complications.

The mean age of transsexual women who underwent GAS in our study was 32.2 years (range 18–61 years), which is lower than the mean age of patients in studies found in the literature. Two studies indicated that the mean ages of patients at time of GAS were 36.7 years and 41 years, respectively ( 4 , 5 ). Another study reported a mean age at time of GAS of 36 years and found there was a significant decrease in age at the time of GAS from 41 years in 1994 to 35 years in 2015 ( 7 ). According to the authors, this decrease in age is associated with greater tolerance and societal approval regarding individuals with GD ( 7 ).

There was no grade IV or grade V complications. Excessive bleeding noticed postoperatively occurred in 19 patients (8.9 percent) and blood transfusion was required in 17 cases (7.9 percent); all patients who required blood transfusions were operated until July 2011, and the reason for this rate of blood transfusion was not identified.

The most common intraoperative complication was rectal injury, occurring in 4 patients (1.9 percent); in all patients the lesion was promptly identified and corrected in 2 layers absorbable sutures. In 2 of these patients, a rectovaginal fistula became evident, requiring fistulectomy and colonic transit deviation. This is consistent with current literature, in which rectal injury is reported in 0.4–4.5 percent of patients ( 4 , 5 , 8 – 13 ). Goddard et al. suggested carefully checking for enterotomy after prostate and bladder mobilization by digital rectal examination ( 4 ). Gaither et al. ( 14 ) commented that careful dissection that closely follows the urethra along its track from the central tendon of the perineum up through the lower pole of the prostate is critical and only blunt dissection is encouraged after Denonvilliers' fascia is reached. Alternatively, a robotic-assisted approach to penile inversion vaginoplasty may aid in minimizing these complications. The proposed advantages of a robotic-assisted vaginoplasty include safer dissection to minimize the risk of rectal injury and better proximal vaginal fixation. Dy et al. ( 15 ) has had no rectal injuries or fistulae to date in his series of 15 patients, with a mean follow-up of 12 months.

In our series, we observed 44 cases (20.5 percent) of urethral meatus strictures. We credit this complication to the technique used in the initial 5 years of our experience, in which the urethra was shortened and sutured in a circular fashion without spatulation. All cases were treated with meatal dilatation and 11 patients required surgical correction, being performed a Y-V plastic reconstruction of the urethral meatus. In the literature, meatal strictures are relatively rare in male-to-female (MtF) GAS due to the spatulation of the urethra and a simple anastomosis to the external genitalia. Recent systematic reviews show an incidence of five percent in this complication ( 16 , 17 ). Other studies report a wide incidence of meatal stenosis ranging from 1.1 to 39.8 percent ( 4 , 8 , 11 ).

Neovagina introital stricture was observed in 33 patients (15.4 percent) in our study and impedes the possibility of neovaginal penetration and/or adversely affects sexual life quality. In the literature, the reported incidence of introital stenosis range from 6.7 to 14.5 percent ( 4 , 5 , 8 , 9 , 11 – 13 ). According to Hadj-Moussa et al. ( 18 ) a regimen of postoperative prophylactic dilation is crucial to minimize the development of this outcome. At our institution, our protocol for vaginal dilation started seven days after surgery and was performed three to four times a day during the first 3 months and was continued until the individual had regular sexual intercourse. We treated stenosis initially with dilation. In case of no response, we propose a surgical revision with diamond-shaped introitoplasty with relaxing incisions. In recalcitrant cases, we proposed to the patient a secondary vaginoplasty using a full-thickness skin graft of the lower abdomen.

One hundred eighty-one (85 percent) patients were classified as having a “functional vagina,” characterized as the capacity to maintain satisfactory sexual vaginal intercourse, since the mean neovaginal depth was not measured. In a review article, the mean neovaginal depth ranged from 10 to 13.5 cm, with the shallowest neovagina depth at 2.5 cm and the deepest at 18 cm ( 17 ). According to Salim et al. ( 19 ), in terms of postoperative functional outcomes after penile inversion vaginoplasty, a mean percentage of 75 percent (range from 33 to 87 percent) patients were having vaginal intercourse. Hess et al. found that 91.4% of patients who responded to a questionnaire were very satisfied (34.4%), satisfied (37.6%), or mostly satisfied (19.4%) with their sexual function after penile inversion vaginoplasty ( 20 ).

Poor cosmetic appearance of the vulva is common. Amend et al. reported that the most common reason for reoperation was cosmetic correction in the form of mons pubis and mucosa reduction in 50% of patients ( 16 ). We had no patient regrets about performing GAS, although 36 patients (16.8 percent) were reoperated due to cosmetic issues. Gaither et al. propose in order to minimize scarring to use a one-stage surgical approach and the lateralization of surgical scars to the groin ( 14 ). Frequently, cosmetic issues outcomes are often patient driven and preoperative patient education is necessary ( 14 ).