Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7 Writing a Literature Review

Hundreds of original investigation research articles on health science topics are published each year. It is becoming harder and harder to keep on top of all new findings in a topic area and – more importantly – to work out how they all fit together to determine our current understanding of a topic. This is where literature reviews come in.

In this chapter, we explain what a literature review is and outline the stages involved in writing one. We also provide practical tips on how to communicate the results of a review of current literature on a topic in the format of a literature review.

7.1 What is a literature review?

Literature reviews provide a synthesis and evaluation of the existing literature on a particular topic with the aim of gaining a new, deeper understanding of the topic.

Published literature reviews are typically written by scientists who are experts in that particular area of science. Usually, they will be widely published as authors of their own original work, making them highly qualified to author a literature review.

However, literature reviews are still subject to peer review before being published. Literature reviews provide an important bridge between the expert scientific community and many other communities, such as science journalists, teachers, and medical and allied health professionals. When the most up-to-date knowledge reaches such audiences, it is more likely that this information will find its way to the general public. When this happens, – the ultimate good of science can be realised.

A literature review is structured differently from an original research article. It is developed based on themes, rather than stages of the scientific method.

In the article Ten simple rules for writing a literature review , Marco Pautasso explains the importance of literature reviews:

Literature reviews are in great demand in most scientific fields. Their need stems from the ever-increasing output of scientific publications. For example, compared to 1991, in 2008 three, eight, and forty times more papers were indexed in Web of Science on malaria, obesity, and biodiversity, respectively. Given such mountains of papers, scientists cannot be expected to examine in detail every single new paper relevant to their interests. Thus, it is both advantageous and necessary to rely on regular summaries of the recent literature. Although recognition for scientists mainly comes from primary research, timely literature reviews can lead to new synthetic insights and are often widely read. For such summaries to be useful, however, they need to be compiled in a professional way (Pautasso, 2013, para. 1).

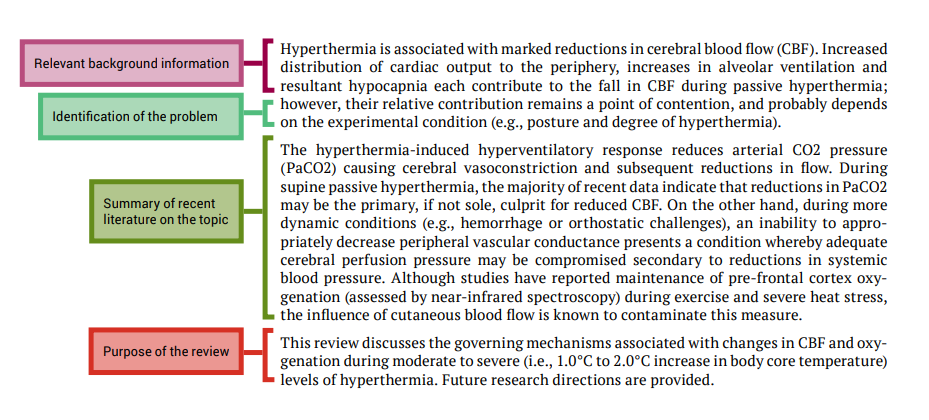

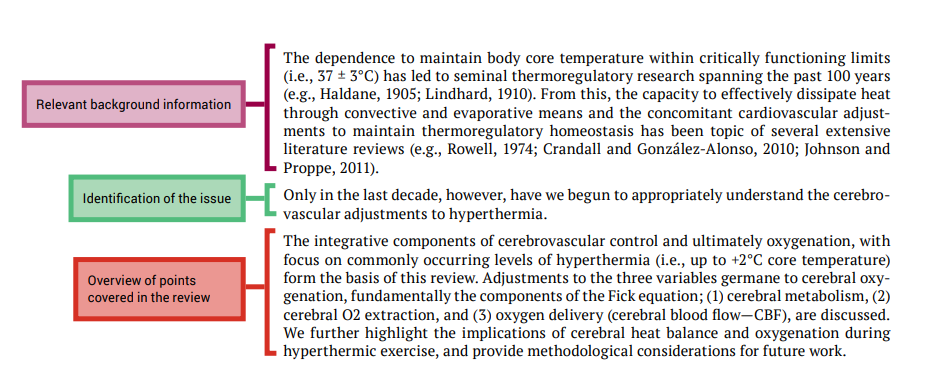

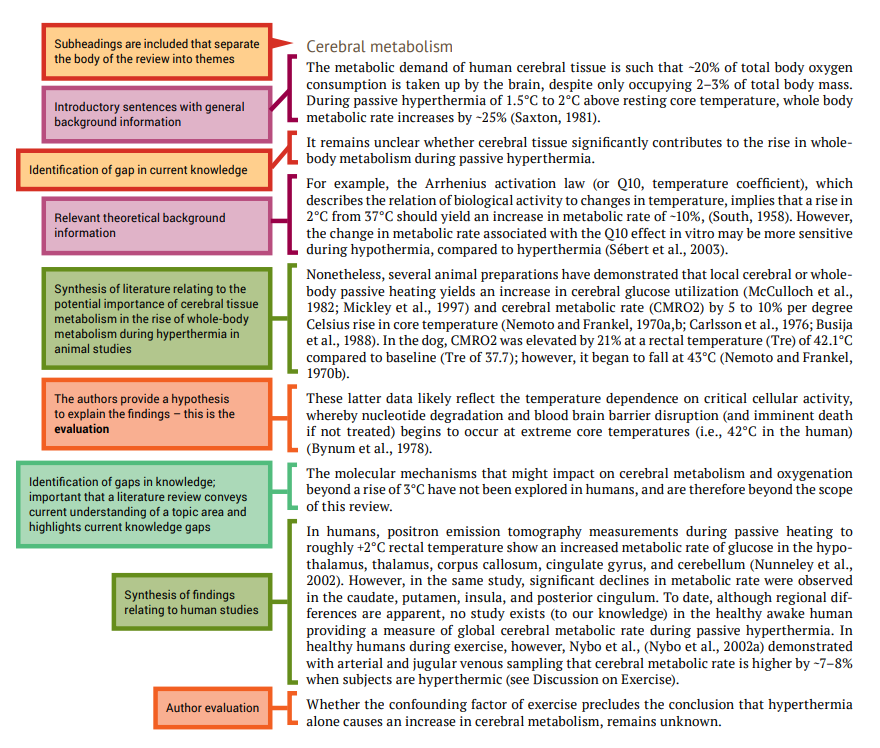

An example of a literature review is shown in Figure 7.1.

Video 7.1: What is a literature review? [2 mins, 11 secs]

Watch this video created by Steely Library at Northern Kentucky Library called ‘ What is a literature review? Note: Closed captions are available by clicking on the CC button below.

Examples of published literature reviews

- Strength training alone, exercise therapy alone, and exercise therapy with passive manual mobilisation each reduce pain and disability in people with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review

- Traveler’s diarrhea: a clinical review

- Cultural concepts of distress and psychiatric disorders: literature review and research recommendations for global mental health epidemiology

7.2 Steps of writing a literature review

Writing a literature review is a very challenging task. Figure 7.2 summarises the steps of writing a literature review. Depending on why you are writing your literature review, you may be given a topic area, or may choose a topic that particularly interests you or is related to a research project that you wish to undertake.

Chapter 6 provides instructions on finding scientific literature that would form the basis for your literature review.

Once you have your topic and have accessed the literature, the next stages (analysis, synthesis and evaluation) are challenging. Next, we look at these important cognitive skills student scientists will need to develop and employ to successfully write a literature review, and provide some guidance for navigating these stages.

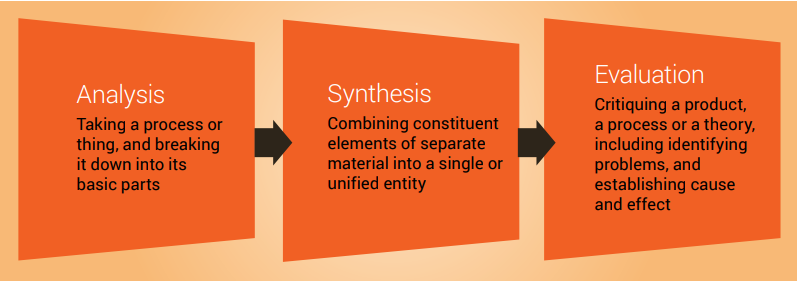

Analysis, synthesis and evaluation

Analysis, synthesis and evaluation are three essential skills required by scientists and you will need to develop these skills if you are to write a good literature review ( Figure 7.3 ). These important cognitive skills are discussed in more detail in Chapter 9.

The first step in writing a literature review is to analyse the original investigation research papers that you have gathered related to your topic.

Analysis requires examining the papers methodically and in detail, so you can understand and interpret aspects of the study described in each research article.

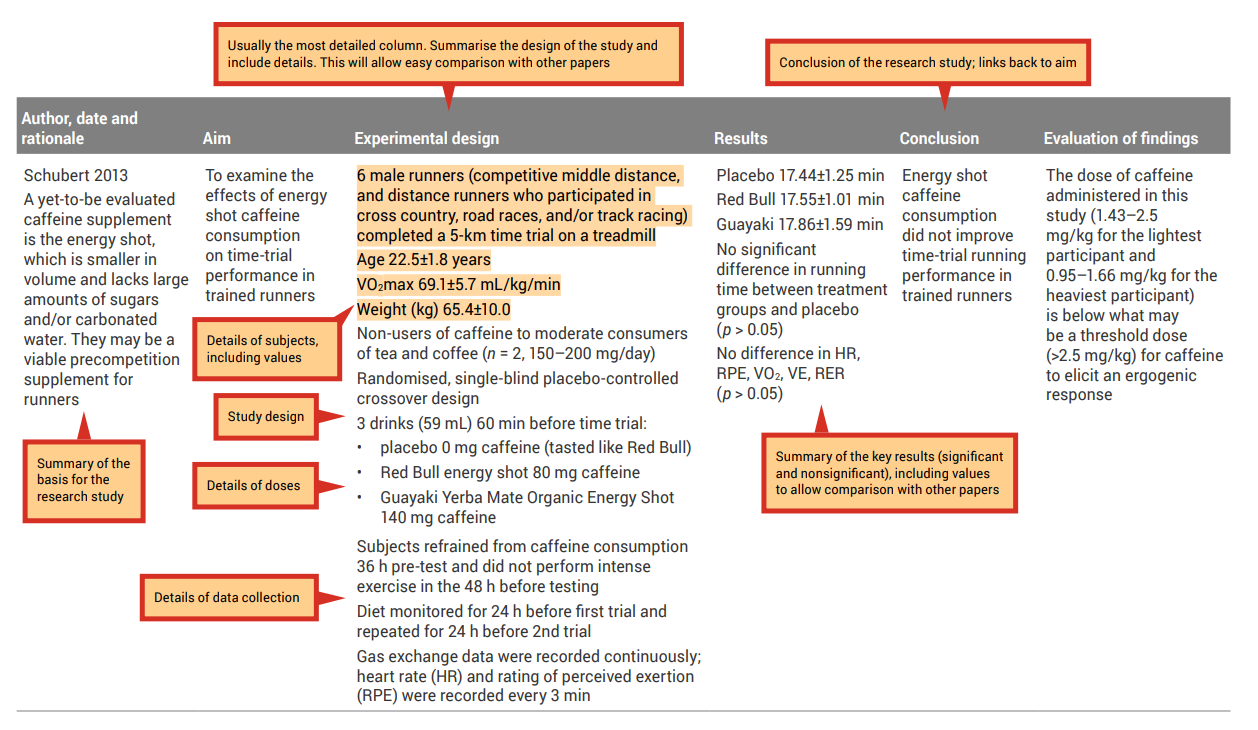

An analysis grid is a simple tool you can use to help with the careful examination and breakdown of each paper. This tool will allow you to create a concise summary of each research paper; see Table 7.1 for an example of an analysis grid. When filling in the grid, the aim is to draw out key aspects of each research paper. Use a different row for each paper, and a different column for each aspect of the paper ( Tables 7.2 and 7.3 show how completed analysis grid may look).

Before completing your own grid, look at these examples and note the types of information that have been included, as well as the level of detail. Completing an analysis grid with a sufficient level of detail will help you to complete the synthesis and evaluation stages effectively. This grid will allow you to more easily observe similarities and differences across the findings of the research papers and to identify possible explanations (e.g., differences in methodologies employed) for observed differences between the findings of different research papers.

Table 7.1: Example of an analysis grid

Table 7.3: Sample filled-in analysis grid for research article by Ping and colleagues

Source: Ping, WC, Keong, CC & Bandyopadhyay, A 2010, ‘Effects of acute supplementation of caffeine on cardiorespiratory responses during endurance running in a hot and humid climate’, Indian Journal of Medical Research, vol. 132, pp. 36–41. Used under a CC-BY-NC-SA licence.

Step two of writing a literature review is synthesis.

Synthesis describes combining separate components or elements to form a connected whole.

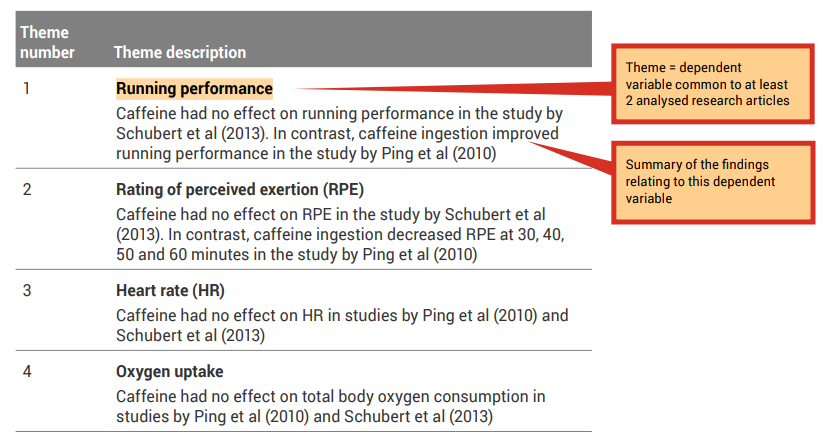

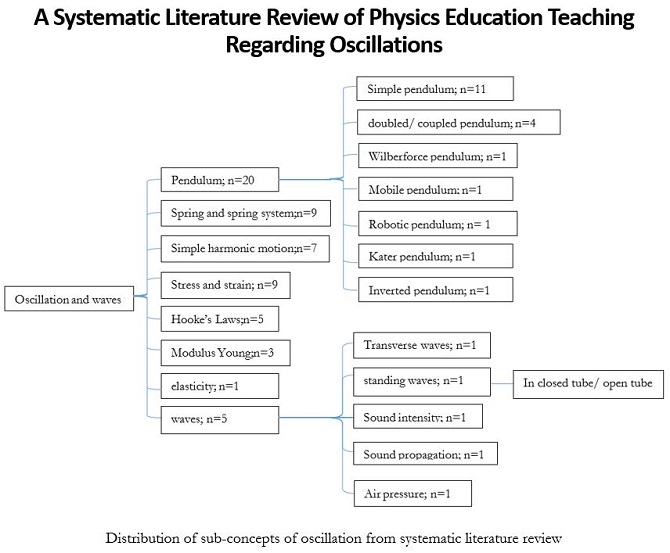

You will use the results of your analysis to find themes to build your literature review around. Each of the themes identified will become a subheading within the body of your literature review.

A good place to start when identifying themes is with the dependent variables (results/findings) that were investigated in the research studies.

Because all of the research articles you are incorporating into your literature review are related to your topic, it is likely that they have similar study designs and have measured similar dependent variables. Review the ‘Results’ column of your analysis grid. You may like to collate the common themes in a synthesis grid (see, for example Table 7.4 ).

Step three of writing a literature review is evaluation, which can only be done after carefully analysing your research papers and synthesising the common themes (findings).

During the evaluation stage, you are making judgements on the themes presented in the research articles that you have read. This includes providing physiological explanations for the findings. It may be useful to refer to the discussion section of published original investigation research papers, or another literature review, where the authors may mention tested or hypothetical physiological mechanisms that may explain their findings.

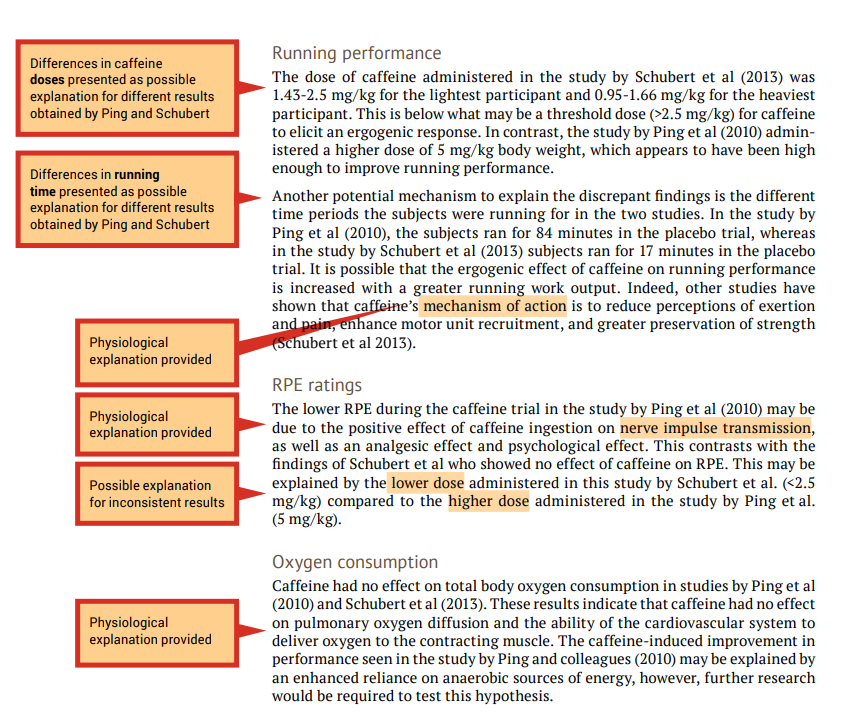

When the findings of the investigations related to a particular theme are inconsistent (e.g., one study shows that caffeine effects performance and another study shows that caffeine had no effect on performance) you should attempt to provide explanations of why the results differ, including physiological explanations. A good place to start is by comparing the methodologies to determine if there are any differences that may explain the differences in the findings (see the ‘Experimental design’ column of your analysis grid). An example of evaluation is shown in the examples that follow in this section, under ‘Running performance’ and ‘RPE ratings’.

When the findings of the papers related to a particular theme are consistent (e.g., caffeine had no effect on oxygen uptake in both studies) an evaluation should include an explanation of why the results are similar. Once again, include physiological explanations. It is still a good idea to compare methodologies as a background to the evaluation. An example of evaluation is shown in the following under ‘Oxygen consumption’.

7.3 Writing your literature review

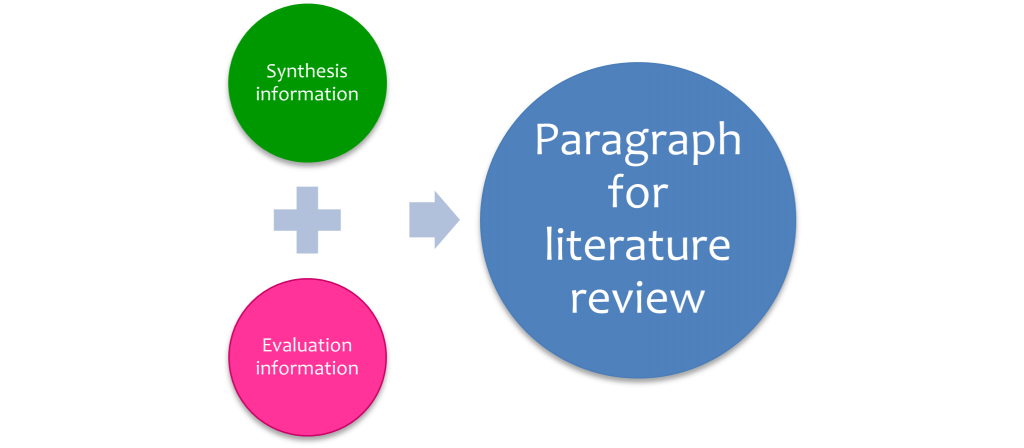

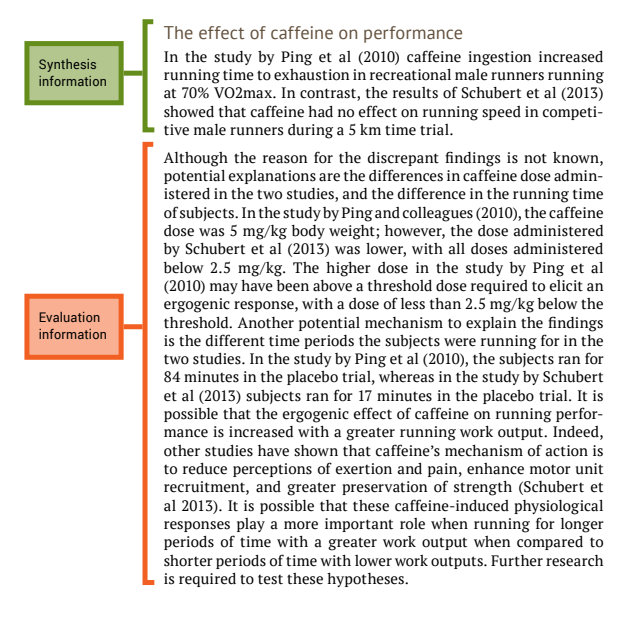

Once you have completed the analysis, and synthesis grids and written your evaluation of the research papers , you can combine synthesis and evaluation information to create a paragraph for a literature review ( Figure 7.4 ).

The following paragraphs are an example of combining the outcome of the synthesis and evaluation stages to produce a paragraph for a literature review.

Note that this is an example using only two papers – most literature reviews would be presenting information on many more papers than this ( (e.g., 106 papers in the review article by Bain and colleagues discussed later in this chapter). However, the same principle applies regardless of the number of papers reviewed.

The next part of this chapter looks at the each section of a literature review and explains how to write them by referring to a review article that was published in Frontiers in Physiology and shown in Figure 7.1. Each section from the published article is annotated to highlight important features of the format of the review article, and identifies the synthesis and evaluation information.

In the examination of each review article section we will point out examples of how the authors have presented certain information and where they display application of important cognitive processes; we will use the colour code shown below:

This should be one paragraph that accurately reflects the contents of the review article.

Introduction

The introduction should establish the context and importance of the review

Body of literature review

The reference section provides a list of the references that you cited in the body of your review article. The format will depend on the journal of publication as each journal has their own specific referencing format.

It is important to accurately cite references in research papers to acknowledge your sources and ensure credit is appropriately given to authors of work you have referred to. An accurate and comprehensive reference list also shows your readers that you are well-read in your topic area and are aware of the key papers that provide the context to your research.

It is important to keep track of your resources and to reference them consistently in the format required by the publication in which your work will appear. Most scientists will use reference management software to store details of all of the journal articles (and other sources) they use while writing their review article. This software also automates the process of adding in-text references and creating a reference list. In the review article by Bain et al. (2014) used as an example in this chapter, the reference list contains 106 items, so you can imagine how much help referencing software would be. Chapter 5 shows you how to use EndNote, one example of reference management software.

Click the drop down below to review the terms learned from this chapter.

Copyright note:

- The quotation from Pautasso, M 2013, ‘Ten simple rules for writing a literature review’, PLoS Computational Biology is use under a CC-BY licence.

- Content from the annotated article and tables are based on Schubert, MM, Astorino, TA & Azevedo, JJL 2013, ‘The effects of caffeinated ‘energy shots’ on time trial performance’, Nutrients, vol. 5, no. 6, pp. 2062–2075 (used under a CC-BY 3.0 licence ) and P ing, WC, Keong , CC & Bandyopadhyay, A 2010, ‘Effects of acute supplementation of caffeine on cardiorespiratory responses during endurance running in a hot and humid climate’, Indian Journal of Medical Research, vol. 132, pp. 36–41 (used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence ).

Bain, A.R., Morrison, S.A., & Ainslie, P.N. (2014). Cerebral oxygenation and hyperthermia. Frontiers in Physiology, 5 , 92.

Pautasso, M. (2013). Ten simple rules for writing a literature review. PLoS Computational Biology, 9 (7), e1003149.

How To Do Science Copyright © 2022 by University of Southern Queensland is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 04 December 2020

- Correction 09 December 2020

How to write a superb literature review

Andy Tay is a freelance writer based in Singapore.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Literature reviews are important resources for scientists. They provide historical context for a field while offering opinions on its future trajectory. Creating them can provide inspiration for one’s own research, as well as some practice in writing. But few scientists are trained in how to write a review — or in what constitutes an excellent one. Even picking the appropriate software to use can be an involved decision (see ‘Tools and techniques’). So Nature asked editors and working scientists with well-cited reviews for their tips.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03422-x

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Updates & Corrections

Correction 09 December 2020 : An earlier version of the tables in this article included some incorrect details about the programs Zotero, Endnote and Manubot. These have now been corrected.

Hsing, I.-M., Xu, Y. & Zhao, W. Electroanalysis 19 , 755–768 (2007).

Article Google Scholar

Ledesma, H. A. et al. Nature Nanotechnol. 14 , 645–657 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Brahlek, M., Koirala, N., Bansal, N. & Oh, S. Solid State Commun. 215–216 , 54–62 (2015).

Choi, Y. & Lee, S. Y. Nature Rev. Chem . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41570-020-00221-w (2020).

Download references

Related Articles

- Research management

How I harnessed media engagement to supercharge my research career

Career Column 09 APR 24

How we landed job interviews for professorships straight out of our PhD programmes

Career Column 08 APR 24

Three ways ChatGPT helps me in my academic writing

How two PhD students overcame the odds to snag tenure-track jobs

Adopt universal standards for study adaptation to boost health, education and social-science research

Correspondence 02 APR 24

Is ChatGPT corrupting peer review? Telltale words hint at AI use

News 10 APR 24

Rwanda 30 years on: understanding the horror of genocide

Editorial 09 APR 24

Junior Group Leader Position at IMBA - Institute of Molecular Biotechnology

The Institute of Molecular Biotechnology (IMBA) is one of Europe’s leading institutes for basic research in the life sciences. IMBA is located on t...

Austria (AT)

IMBA - Institute of Molecular Biotechnology

Open Rank Faculty, Center for Public Health Genomics

Center for Public Health Genomics & UVA Comprehensive Cancer Center seek 2 tenure-track faculty members in Cancer Precision Medicine/Precision Health.

Charlottesville, Virginia

Center for Public Health Genomics at the University of Virginia

Husbandry Technician I

Memphis, Tennessee

St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (St. Jude)

Lead Researcher – Department of Bone Marrow Transplantation & Cellular Therapy

Researcher in the center for in vivo imaging and therapy.

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Research in the Biological and Life Sciences: A Guide for Cornell Researchers: Literature Reviews

- Books and Dissertations

- Databases and Journals

- Locating Theses

- Resource Not at Cornell?

- Citing Sources

- Staying Current

- Measuring your research impact

- Plagiarism and Copyright

- Data Management

- Literature Reviews

- Evidence Synthesis and Systematic Reviews

- Writing an Honors Thesis

- Poster Making and Printing

- Research Help

What is a Literature Review?

A literature review is a body of text that aims to review the critical points of current knowledge on a particular topic. Most often associated with science-oriented literature, such as a thesis, the literature review usually proceeds a research proposal, methodology and results section. Its ultimate goals is to bring the reader up to date with current literature on a topic and forms that basis for another goal, such as the justification for future research in the area. (retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Literature_review )

Writing a Literature Review

The literature review is the section of your paper in which you cite and briefly review the related research studies that have been conducted. In this space, you will describe the foundation on which your research will be/is built. You will:

- discuss the work of others

- evaluate their methods and findings

- identify any gaps in their research

- state how your research is different

The literature review should be selective and should group the cited studies in some logical fashion.

If you need some additional assistance writing your literature review, the Knight Institute for Writing in the Disciplines offers a Graduate Writing Service .

Demystifying the Literature Review

For more information, visit our guide devoted to " Demystifying the Literature Review " which includes:

- guide to conducting a literature review,

- a recorded 1.5 hour workshop covering the steps of a literature review, a checklist for drafting your topic and search terms, citation management software for organizing your results, and database searching.

Online Resources

- A Guide to Library Research at Cornell University

- Literature Reviews: An Overview for Graduate Students North Carolina State University

- The Literature Review: A Few Tips on Conducting Written by Dena Taylor, Director, Health Sciences Writing Centre, and Margaret Procter, Coordinator, Writing Support, University of Toronto

- How to Write a Literature Review University Library, University of California, Santa Cruz

- Review of Literature The Writing Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Print Resources

- << Previous: Writing

- Next: Evidence Synthesis and Systematic Reviews >>

- Last Updated: Oct 25, 2023 11:28 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.cornell.edu/bio

How to Write a Good Scientific Literature Review

Nowadays, there is a huge demand for scientific literature reviews as they are especially appreciated by scholars or researchers when designing their research proposals. While finding information is less of a problem to them, discerning which paper or publication has enough quality has become one of the biggest issues. Literature reviews narrow the current knowledge on a certain field and examine the latest publications’ strengths and weaknesses. This way, they are priceless tools not only for those who are starting their research, but also for all those interested in recent publications. To be useful, literature reviews must be written in a professional way with a clear structure. The amount of work needed to write a scientific literature review must be considered before starting one since the tasks required can overwhelm many if the working method is not the best.

Designing and Writing a Scientific Literature Review

Writing a scientific review implies both researching for relevant academic content and writing , however, writing without having a clear objective is a common mistake. Sometimes, studying the situation and defining the work’s system is so important and takes equally as much time as that required in writing the final result. Therefore, we suggest that you divide your path into three steps.

Define goals and a structure

Think about your target and narrow down your topic. If you don’t choose a well-defined topic, you can find yourself dealing with a wide subject and plenty of publications about it. Remember that researchers usually deal with really specific fields of study.

It is time to be a critic and locate only pertinent publications. While researching for content consider publications that were written 3 years ago at the most. Write notes and summarize the content of each paper as that will help you in the next step.

Time to write

Check some literature review examples to decide how to start writing a good literature review . When your goals and structure are defined, begin writing without forgetting your target at any moment.

Related: Conducting a literature survey? Wish to learn more about scientific misconduct? Check out this resourceful infographic.

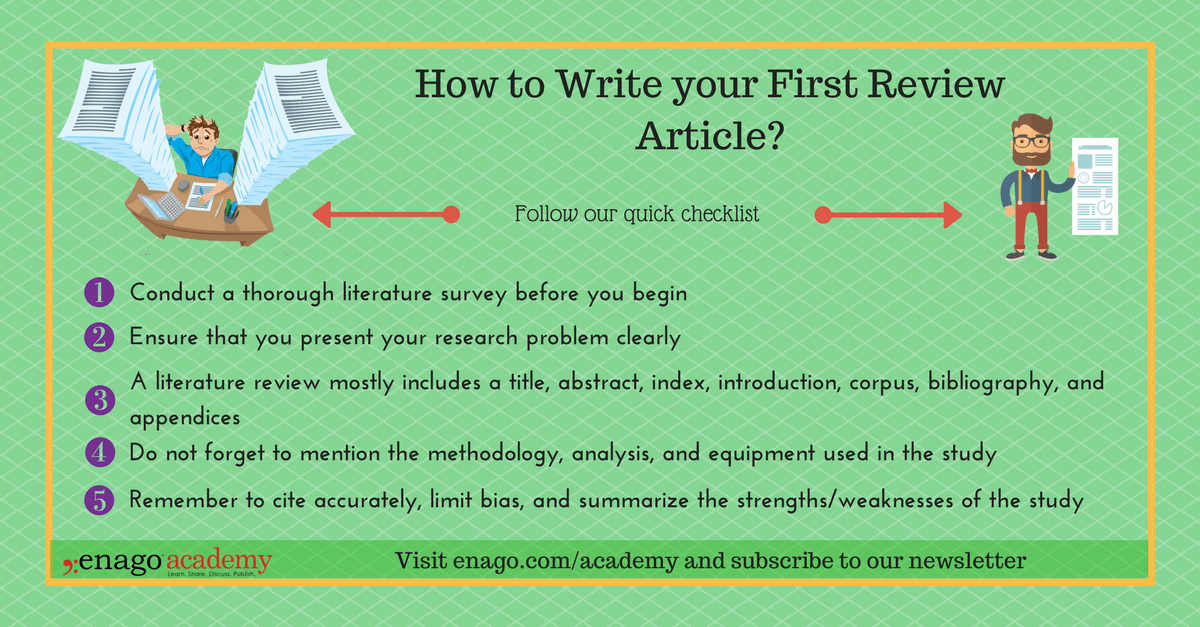

Here you have a to-do list to help you write your review :

- A scientific literature review usually includes a title, abstract, index, introduction, corpus, bibliography, and appendices (if needed).

- Present the problem clearly.

- Mention the paper’s methodology, research methods, analysis, instruments, etc.

- Present literature review examples that can help you express your ideas.

- Remember to cite accurately.

- Limit your bias

- While summarizing also identify strengths and weaknesses as this is critical.

Scholars and researchers are usually the best candidates to write scientific literature reviews, not only because they are experts in a certain field, but also because they know the exigencies and needs that researchers have while writing research proposals or looking for information among thousands of academic papers. Therefore, considering your experience as a researcher can help you understand how to write a scientific literature review.

Have you faced challenges while drafting your first literature review? How do you think can these tips help you in acing your next literature review? Let us know in the comments section below! You can also visit our Q&A forum for frequently asked questions related to copyrights answered by our team that comprises eminent researchers and publication experts.

Thank you for your information. It adds knowledge on critical review being a first time to do it, it helps a lot.

yes. i would like to ndertake the course Bio ststistics

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Reporting Research

AI Assistance in Academia for Searching Credible Scholarly Sources

The journey of academia is a grand quest for knowledge, more specifically an adventure to…

- Manuscripts & Grants

Writing a Research Literature Review? — Here are tips to guide you through!

Literature review is both a process and a product. It involves searching within a defined…

- AI in Academia

How to Scan Through Millions of Articles and Still Cut Down on Your Reading Time — Why not do it with an AI-based article summarizer?

Researcher 1: “It’s flooding articles every time I switch on my laptop!” Researcher 2: “Why…

How to Master at Literature Mapping: 5 Most Recommended Tools to Use

This article is also available in: Turkish, Spanish, Russian, and Portuguese

- Old Webinars

- Webinar Mobile App

Improving Your Chances of Publication in International Peer-reviewed Journals

Types of literature reviews Tips for writing review articles Role of meta-analysis Reporting guidelines

How to Scan Through Millions of Articles and Still Cut Down on Your Reading Time —…

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

How To Write An A-Grade Literature Review

3 straightforward steps (with examples) + free template.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | October 2019

Quality research is about building onto the existing work of others , “standing on the shoulders of giants”, as Newton put it. The literature review chapter of your dissertation, thesis or research project is where you synthesise this prior work and lay the theoretical foundation for your own research.

Long story short, this chapter is a pretty big deal, which is why you want to make sure you get it right . In this post, I’ll show you exactly how to write a literature review in three straightforward steps, so you can conquer this vital chapter (the smart way).

Overview: The Literature Review Process

- Understanding the “ why “

- Finding the relevant literature

- Cataloguing and synthesising the information

- Outlining & writing up your literature review

- Example of a literature review

But first, the “why”…

Before we unpack how to write the literature review chapter, we’ve got to look at the why . To put it bluntly, if you don’t understand the function and purpose of the literature review process, there’s no way you can pull it off well. So, what exactly is the purpose of the literature review?

Well, there are (at least) four core functions:

- For you to gain an understanding (and demonstrate this understanding) of where the research is at currently, what the key arguments and disagreements are.

- For you to identify the gap(s) in the literature and then use this as justification for your own research topic.

- To help you build a conceptual framework for empirical testing (if applicable to your research topic).

- To inform your methodological choices and help you source tried and tested questionnaires (for interviews ) and measurement instruments (for surveys ).

Most students understand the first point but don’t give any thought to the rest. To get the most from the literature review process, you must keep all four points front of mind as you review the literature (more on this shortly), or you’ll land up with a wonky foundation.

Okay – with the why out the way, let’s move on to the how . As mentioned above, writing your literature review is a process, which I’ll break down into three steps:

- Finding the most suitable literature

- Understanding , distilling and organising the literature

- Planning and writing up your literature review chapter

Importantly, you must complete steps one and two before you start writing up your chapter. I know it’s very tempting, but don’t try to kill two birds with one stone and write as you read. You’ll invariably end up wasting huge amounts of time re-writing and re-shaping, or you’ll just land up with a disjointed, hard-to-digest mess . Instead, you need to read first and distil the information, then plan and execute the writing.

Step 1: Find the relevant literature

Naturally, the first step in the literature review journey is to hunt down the existing research that’s relevant to your topic. While you probably already have a decent base of this from your research proposal , you need to expand on this substantially in the dissertation or thesis itself.

Essentially, you need to be looking for any existing literature that potentially helps you answer your research question (or develop it, if that’s not yet pinned down). There are numerous ways to find relevant literature, but I’ll cover my top four tactics here. I’d suggest combining all four methods to ensure that nothing slips past you:

Method 1 – Google Scholar Scrubbing

Google’s academic search engine, Google Scholar , is a great starting point as it provides a good high-level view of the relevant journal articles for whatever keyword you throw at it. Most valuably, it tells you how many times each article has been cited, which gives you an idea of how credible (or at least, popular) it is. Some articles will be free to access, while others will require an account, which brings us to the next method.

Method 2 – University Database Scrounging

Generally, universities provide students with access to an online library, which provides access to many (but not all) of the major journals.

So, if you find an article using Google Scholar that requires paid access (which is quite likely), search for that article in your university’s database – if it’s listed there, you’ll have access. Note that, generally, the search engine capabilities of these databases are poor, so make sure you search for the exact article name, or you might not find it.

Method 3 – Journal Article Snowballing

At the end of every academic journal article, you’ll find a list of references. As with any academic writing, these references are the building blocks of the article, so if the article is relevant to your topic, there’s a good chance a portion of the referenced works will be too. Do a quick scan of the titles and see what seems relevant, then search for the relevant ones in your university’s database.

Method 4 – Dissertation Scavenging

Similar to Method 3 above, you can leverage other students’ dissertations. All you have to do is skim through literature review chapters of existing dissertations related to your topic and you’ll find a gold mine of potential literature. Usually, your university will provide you with access to previous students’ dissertations, but you can also find a much larger selection in the following databases:

- Open Access Theses & Dissertations

- Stanford SearchWorks

Keep in mind that dissertations and theses are not as academically sound as published, peer-reviewed journal articles (because they’re written by students, not professionals), so be sure to check the credibility of any sources you find using this method. You can do this by assessing the citation count of any given article in Google Scholar. If you need help with assessing the credibility of any article, or with finding relevant research in general, you can chat with one of our Research Specialists .

Alright – with a good base of literature firmly under your belt, it’s time to move onto the next step.

Need a helping hand?

Step 2: Log, catalogue and synthesise

Once you’ve built a little treasure trove of articles, it’s time to get reading and start digesting the information – what does it all mean?

While I present steps one and two (hunting and digesting) as sequential, in reality, it’s more of a back-and-forth tango – you’ll read a little , then have an idea, spot a new citation, or a new potential variable, and then go back to searching for articles. This is perfectly natural – through the reading process, your thoughts will develop , new avenues might crop up, and directional adjustments might arise. This is, after all, one of the main purposes of the literature review process (i.e. to familiarise yourself with the current state of research in your field).

As you’re working through your treasure chest, it’s essential that you simultaneously start organising the information. There are three aspects to this:

- Logging reference information

- Building an organised catalogue

- Distilling and synthesising the information

I’ll discuss each of these below:

2.1 – Log the reference information

As you read each article, you should add it to your reference management software. I usually recommend Mendeley for this purpose (see the Mendeley 101 video below), but you can use whichever software you’re comfortable with. Most importantly, make sure you load EVERY article you read into your reference manager, even if it doesn’t seem very relevant at the time.

2.2 – Build an organised catalogue

In the beginning, you might feel confident that you can remember who said what, where, and what their main arguments were. Trust me, you won’t. If you do a thorough review of the relevant literature (as you must!), you’re going to read many, many articles, and it’s simply impossible to remember who said what, when, and in what context . Also, without the bird’s eye view that a catalogue provides, you’ll miss connections between various articles, and have no view of how the research developed over time. Simply put, it’s essential to build your own catalogue of the literature.

I would suggest using Excel to build your catalogue, as it allows you to run filters, colour code and sort – all very useful when your list grows large (which it will). How you lay your spreadsheet out is up to you, but I’d suggest you have the following columns (at minimum):

- Author, date, title – Start with three columns containing this core information. This will make it easy for you to search for titles with certain words, order research by date, or group by author.

- Categories or keywords – You can either create multiple columns, one for each category/theme and then tick the relevant categories, or you can have one column with keywords.

- Key arguments/points – Use this column to succinctly convey the essence of the article, the key arguments and implications thereof for your research.

- Context – Note the socioeconomic context in which the research was undertaken. For example, US-based, respondents aged 25-35, lower- income, etc. This will be useful for making an argument about gaps in the research.

- Methodology – Note which methodology was used and why. Also, note any issues you feel arise due to the methodology. Again, you can use this to make an argument about gaps in the research.

- Quotations – Note down any quoteworthy lines you feel might be useful later.

- Notes – Make notes about anything not already covered. For example, linkages to or disagreements with other theories, questions raised but unanswered, shortcomings or limitations, and so forth.

If you’d like, you can try out our free catalog template here (see screenshot below).

2.3 – Digest and synthesise

Most importantly, as you work through the literature and build your catalogue, you need to synthesise all the information in your own mind – how does it all fit together? Look for links between the various articles and try to develop a bigger picture view of the state of the research. Some important questions to ask yourself are:

- What answers does the existing research provide to my own research questions ?

- Which points do the researchers agree (and disagree) on?

- How has the research developed over time?

- Where do the gaps in the current research lie?

To help you develop a big-picture view and synthesise all the information, you might find mind mapping software such as Freemind useful. Alternatively, if you’re a fan of physical note-taking, investing in a large whiteboard might work for you.

Step 3: Outline and write it up!

Once you’re satisfied that you have digested and distilled all the relevant literature in your mind, it’s time to put pen to paper (or rather, fingers to keyboard). There are two steps here – outlining and writing:

3.1 – Draw up your outline

Having spent so much time reading, it might be tempting to just start writing up without a clear structure in mind. However, it’s critically important to decide on your structure and develop a detailed outline before you write anything. Your literature review chapter needs to present a clear, logical and an easy to follow narrative – and that requires some planning. Don’t try to wing it!

Naturally, you won’t always follow the plan to the letter, but without a detailed outline, you’re more than likely going to end up with a disjointed pile of waffle , and then you’re going to spend a far greater amount of time re-writing, hacking and patching. The adage, “measure twice, cut once” is very suitable here.

In terms of structure, the first decision you’ll have to make is whether you’ll lay out your review thematically (into themes) or chronologically (by date/period). The right choice depends on your topic, research objectives and research questions, which we discuss in this article .

Once that’s decided, you need to draw up an outline of your entire chapter in bullet point format. Try to get as detailed as possible, so that you know exactly what you’ll cover where, how each section will connect to the next, and how your entire argument will develop throughout the chapter. Also, at this stage, it’s a good idea to allocate rough word count limits for each section, so that you can identify word count problems before you’ve spent weeks or months writing!

PS – check out our free literature review chapter template…

3.2 – Get writing

With a detailed outline at your side, it’s time to start writing up (finally!). At this stage, it’s common to feel a bit of writer’s block and find yourself procrastinating under the pressure of finally having to put something on paper. To help with this, remember that the objective of the first draft is not perfection – it’s simply to get your thoughts out of your head and onto paper, after which you can refine them. The structure might change a little, the word count allocations might shift and shuffle, and you might add or remove a section – that’s all okay. Don’t worry about all this on your first draft – just get your thoughts down on paper.

Once you’ve got a full first draft (however rough it may be), step away from it for a day or two (longer if you can) and then come back at it with fresh eyes. Pay particular attention to the flow and narrative – does it fall fit together and flow from one section to another smoothly? Now’s the time to try to improve the linkage from each section to the next, tighten up the writing to be more concise, trim down word count and sand it down into a more digestible read.

Once you’ve done that, give your writing to a friend or colleague who is not a subject matter expert and ask them if they understand the overall discussion. The best way to assess this is to ask them to explain the chapter back to you. This technique will give you a strong indication of which points were clearly communicated and which weren’t. If you’re working with Grad Coach, this is a good time to have your Research Specialist review your chapter.

Finally, tighten it up and send it off to your supervisor for comment. Some might argue that you should be sending your work to your supervisor sooner than this (indeed your university might formally require this), but in my experience, supervisors are extremely short on time (and often patience), so, the more refined your chapter is, the less time they’ll waste on addressing basic issues (which you know about already) and the more time they’ll spend on valuable feedback that will increase your mark-earning potential.

Literature Review Example

In the video below, we unpack an actual literature review so that you can see how all the core components come together in reality.

Let’s Recap

In this post, we’ve covered how to research and write up a high-quality literature review chapter. Let’s do a quick recap of the key takeaways:

- It is essential to understand the WHY of the literature review before you read or write anything. Make sure you understand the 4 core functions of the process.

- The first step is to hunt down the relevant literature . You can do this using Google Scholar, your university database, the snowballing technique and by reviewing other dissertations and theses.

- Next, you need to log all the articles in your reference manager , build your own catalogue of literature and synthesise all the research.

- Following that, you need to develop a detailed outline of your entire chapter – the more detail the better. Don’t start writing without a clear outline (on paper, not in your head!)

- Write up your first draft in rough form – don’t aim for perfection. Remember, done beats perfect.

- Refine your second draft and get a layman’s perspective on it . Then tighten it up and submit it to your supervisor.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling Udemy Course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

38 Comments

Thank you very much. This page is an eye opener and easy to comprehend.

This is awesome!

I wish I come across GradCoach earlier enough.

But all the same I’ll make use of this opportunity to the fullest.

Thank you for this good job.

Keep it up!

You’re welcome, Yinka. Thank you for the kind words. All the best writing your literature review.

Thank you for a very useful literature review session. Although I am doing most of the steps…it being my first masters an Mphil is a self study and one not sure you are on the right track. I have an amazing supervisor but one also knows they are super busy. So not wanting to bother on the minutae. Thank you.

You’re most welcome, Renee. Good luck with your literature review 🙂

This has been really helpful. Will make full use of it. 🙂

Thank you Gradcoach.

Really agreed. Admirable effort

thank you for this beautiful well explained recap.

Thank you so much for your guide of video and other instructions for the dissertation writing.

It is instrumental. It encouraged me to write a dissertation now.

Thank you the video was great – from someone that knows nothing thankyou

an amazing and very constructive way of presetting a topic, very useful, thanks for the effort,

It is timely

It is very good video of guidance for writing a research proposal and a dissertation. Since I have been watching and reading instructions, I have started my research proposal to write. I appreciate to Mr Jansen hugely.

I learn a lot from your videos. Very comprehensive and detailed.

Thank you for sharing your knowledge. As a research student, you learn better with your learning tips in research

I was really stuck in reading and gathering information but after watching these things are cleared thanks, it is so helpful.

Really helpful, Thank you for the effort in showing such information

This is super helpful thank you very much.

Thank you for this whole literature writing review.You have simplified the process.

I’m so glad I found GradCoach. Excellent information, Clear explanation, and Easy to follow, Many thanks Derek!

You’re welcome, Maithe. Good luck writing your literature review 🙂

Thank you Coach, you have greatly enriched and improved my knowledge

Great piece, so enriching and it is going to help me a great lot in my project and thesis, thanks so much

This is THE BEST site for ANYONE doing a masters or doctorate! Thank you for the sound advice and templates. You rock!

Thanks, Stephanie 🙂

This is mind blowing, the detailed explanation and simplicity is perfect.

I am doing two papers on my final year thesis, and I must stay I feel very confident to face both headlong after reading this article.

thank you so much.

if anyone is to get a paper done on time and in the best way possible, GRADCOACH is certainly the go to area!

This is very good video which is well explained with detailed explanation

Thank you excellent piece of work and great mentoring

Thanks, it was useful

Thank you very much. the video and the information were very helpful.

Good morning scholar. I’m delighted coming to know you even before the commencement of my dissertation which hopefully is expected in not more than six months from now. I would love to engage my study under your guidance from the beginning to the end. I love to know how to do good job

Thank you so much Derek for such useful information on writing up a good literature review. I am at a stage where I need to start writing my one. My proposal was accepted late last year but I honestly did not know where to start

Like the name of your YouTube implies you are GRAD (great,resource person, about dissertation). In short you are smart enough in coaching research work.

This is a very well thought out webpage. Very informative and a great read.

Very timely.

I appreciate.

Very comprehensive and eye opener for me as beginner in postgraduate study. Well explained and easy to understand. Appreciate and good reference in guiding me in my research journey. Thank you

Thank you. I requested to download the free literature review template, however, your website wouldn’t allow me to complete the request or complete a download. May I request that you email me the free template? Thank you.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 5. The Literature Review

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A literature review surveys prior research published in books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, and by so doing, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of these works in relation to the research problem being investigated. Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have used in researching a particular topic and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within existing scholarship about the topic.

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . Fourth edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2014.

Importance of a Good Literature Review

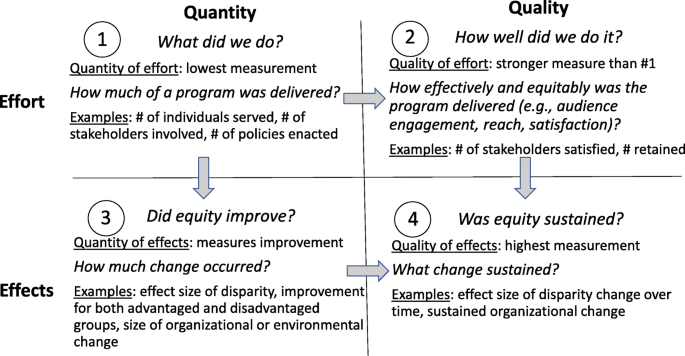

A literature review may consist of simply a summary of key sources, but in the social sciences, a literature review usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

Given this, the purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important].

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2011; Knopf, Jeffrey W. "Doing a Literature Review." PS: Political Science and Politics 39 (January 2006): 127-132; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012.

Types of Literature Reviews

It is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the primary studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally among scholars that become part of the body of epistemological traditions within the field.

In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews. Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are a number of approaches you could adopt depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study.

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply embedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews [see below].

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses or research problems. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication. This is the most common form of review in the social sciences.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [findings], but how they came about saying what they say [method of analysis]. Reviewing methods of analysis provides a framework of understanding at different levels [i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches, and data collection and analysis techniques], how researchers draw upon a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection, and data analysis. This approach helps highlight ethical issues which you should be aware of and consider as you go through your own study.

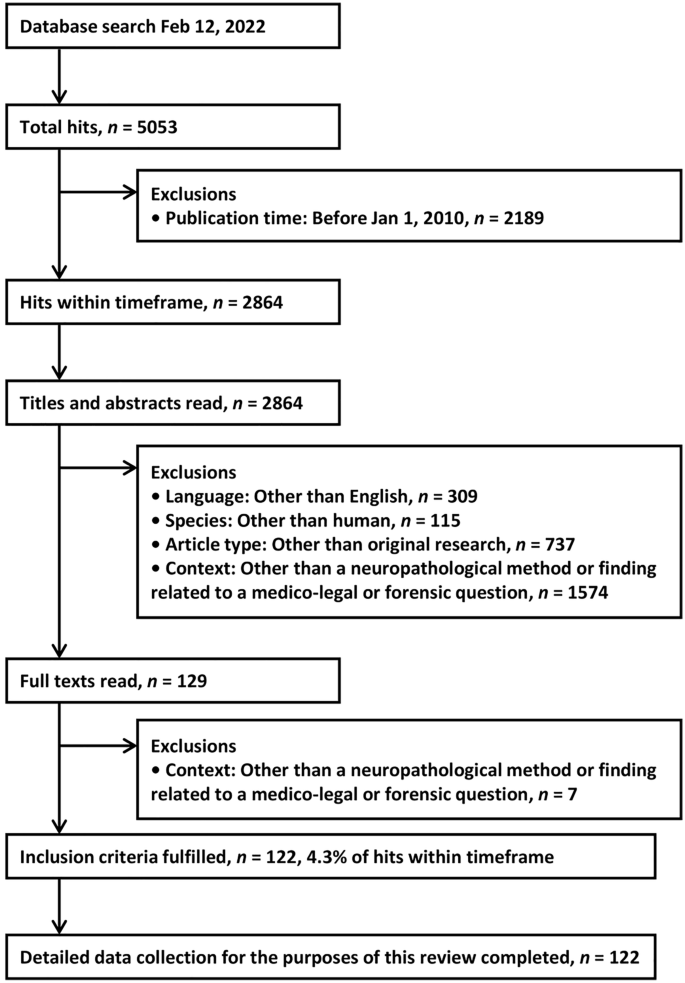

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyze data from the studies that are included in the review. The goal is to deliberately document, critically evaluate, and summarize scientifically all of the research about a clearly defined research problem . Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?" This type of literature review is primarily applied to examining prior research studies in clinical medicine and allied health fields, but it is increasingly being used in the social sciences.

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review helps to establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

NOTE : Most often the literature review will incorporate some combination of types. For example, a review that examines literature supporting or refuting an argument, assumption, or philosophical problem related to the research problem will also need to include writing supported by sources that establish the history of these arguments in the literature.

Baumeister, Roy F. and Mark R. Leary. "Writing Narrative Literature Reviews." Review of General Psychology 1 (September 1997): 311-320; Mark R. Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147; Petticrew, Mark and Helen Roberts. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide . Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2006; Torracro, Richard. "Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples." Human Resource Development Review 4 (September 2005): 356-367; Rocco, Tonette S. and Maria S. Plakhotnik. "Literature Reviews, Conceptual Frameworks, and Theoretical Frameworks: Terms, Functions, and Distinctions." Human Ressource Development Review 8 (March 2008): 120-130; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Thinking About Your Literature Review

The structure of a literature review should include the following in support of understanding the research problem :

- An overview of the subject, issue, or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review,

- Division of works under review into themes or categories [e.g. works that support a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative approaches entirely],

- An explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others,

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research.

The critical evaluation of each work should consider :

- Provenance -- what are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence [e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings]?

- Methodology -- were the techniques used to identify, gather, and analyze the data appropriate to addressing the research problem? Was the sample size appropriate? Were the results effectively interpreted and reported?

- Objectivity -- is the author's perspective even-handed or prejudicial? Is contrary data considered or is certain pertinent information ignored to prove the author's point?

- Persuasiveness -- which of the author's theses are most convincing or least convincing?

- Validity -- are the author's arguments and conclusions convincing? Does the work ultimately contribute in any significant way to an understanding of the subject?

II. Development of the Literature Review

Four Basic Stages of Writing 1. Problem formulation -- which topic or field is being examined and what are its component issues? 2. Literature search -- finding materials relevant to the subject being explored. 3. Data evaluation -- determining which literature makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the topic. 4. Analysis and interpretation -- discussing the findings and conclusions of pertinent literature.

Consider the following issues before writing the literature review: Clarify If your assignment is not specific about what form your literature review should take, seek clarification from your professor by asking these questions: 1. Roughly how many sources would be appropriate to include? 2. What types of sources should I review (books, journal articles, websites; scholarly versus popular sources)? 3. Should I summarize, synthesize, or critique sources by discussing a common theme or issue? 4. Should I evaluate the sources in any way beyond evaluating how they relate to understanding the research problem? 5. Should I provide subheadings and other background information, such as definitions and/or a history? Find Models Use the exercise of reviewing the literature to examine how authors in your discipline or area of interest have composed their literature review sections. Read them to get a sense of the types of themes you might want to look for in your own research or to identify ways to organize your final review. The bibliography or reference section of sources you've already read, such as required readings in the course syllabus, are also excellent entry points into your own research. Narrow the Topic The narrower your topic, the easier it will be to limit the number of sources you need to read in order to obtain a good survey of relevant resources. Your professor will probably not expect you to read everything that's available about the topic, but you'll make the act of reviewing easier if you first limit scope of the research problem. A good strategy is to begin by searching the USC Libraries Catalog for recent books about the topic and review the table of contents for chapters that focuses on specific issues. You can also review the indexes of books to find references to specific issues that can serve as the focus of your research. For example, a book surveying the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict may include a chapter on the role Egypt has played in mediating the conflict, or look in the index for the pages where Egypt is mentioned in the text. Consider Whether Your Sources are Current Some disciplines require that you use information that is as current as possible. This is particularly true in disciplines in medicine and the sciences where research conducted becomes obsolete very quickly as new discoveries are made. However, when writing a review in the social sciences, a survey of the history of the literature may be required. In other words, a complete understanding the research problem requires you to deliberately examine how knowledge and perspectives have changed over time. Sort through other current bibliographies or literature reviews in the field to get a sense of what your discipline expects. You can also use this method to explore what is considered by scholars to be a "hot topic" and what is not.

III. Ways to Organize Your Literature Review