An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.369; 2020

Food for Thought 2020

Food and mood: how do diet and nutrition affect mental wellbeing, joseph firth.

1 Division of Psychology and Mental Health, Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health, Oxford Road, University of Manchester, Manchester M13 9PL, UK

2 NICM Health Research Institute, Western Sydney University, Westmead, Australia

James E Gangwisch

3 Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, USA

4 New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, NY, USA

Alessandra Borsini

5 Section of Stress, Psychiatry and Immunology Laboratory, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, Department of Psychological Medicine, King’s College London, London, UK

Robyn E Wootton

6 School of Psychological Science, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK

7 MRC Integrative Epidemiology Unit, Oakfield House, Bristol, UK

8 NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust and University of Bristol, Bristol, UK

Emeran A Mayer

9 G Oppenheimer Center for Neurobiology of Stress and Resilience, UCLA Vatche and Tamar Manoukian Division of Digestive Diseases, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA

10 UCLA Microbiome Center, David Geffen School of Medicine, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Poor nutrition may be a causal factor in the experience of low mood, and improving diet may help to protect not only the physical health but also the mental health of the population, say Joseph Firth and colleagues

Key messages

- Healthy eating patterns, such as the Mediterranean diet, are associated with better mental health than “unhealthy” eating patterns, such as the Western diet

- The effects of certain foods or dietary patterns on glycaemia, immune activation, and the gut microbiome may play a role in the relationships between food and mood

- More research is needed to understand the mechanisms that link food and mental wellbeing and determine how and when nutrition can be used to improve mental health

Depression and anxiety are the most common mental health conditions worldwide, making them a leading cause of disability. 1 Even beyond diagnosed conditions, subclinical symptoms of depression and anxiety affect the wellbeing and functioning of a large proportion of the population. 2 Therefore, new approaches to managing both clinically diagnosed and subclinical depression and anxiety are needed.

In recent years, the relationships between nutrition and mental health have gained considerable interest. Indeed, epidemiological research has observed that adherence to healthy or Mediterranean dietary patterns—high consumption of fruits, vegetables, nuts, and legumes; moderate consumption of poultry, eggs, and dairy products; and only occasional consumption of red meat—is associated with a reduced risk of depression. 3 However, the nature of these relations is complicated by the clear potential for reverse causality between diet and mental health ( fig 1 ). For example, alterations in food choices or preferences in response to our temporary psychological state—such as “comfort foods” in times of low mood, or changes in appetite from stress—are common human experiences. In addition, relationships between nutrition and longstanding mental illness are compounded by barriers to maintaining a healthy diet. These barriers disproportionality affect people with mental illness and include the financial and environmental determinants of health, and even the appetite inducing effects of psychiatric medications. 4

Hypothesised relationship between diet, physical health, and mental health. The dashed line is the focus of this article.

While acknowledging the complex, multidirectional nature of the relationships between diet and mental health ( fig 1 ), in this article we focus on the ways in which certain foods and dietary patterns could affect mental health.

Mood and carbohydrates

Consumption of highly refined carbohydrates can increase the risk of obesity and diabetes. 5 Glycaemic index is a relative ranking of carbohydrate in foods according to the speed at which they are digested, absorbed, metabolised, and ultimately affect blood glucose and insulin levels. As well as the physical health risks, diets with a high glycaemic index and load (eg, diets containing high amounts of refined carbohydrates and sugars) may also have a detrimental effect on psychological wellbeing; data from longitudinal research show an association between progressively higher dietary glycaemic index and the incidence of depressive symptoms. 6 Clinical studies have also shown potential causal effects of refined carbohydrates on mood; experimental exposure to diets with a high glycaemic load in controlled settings increases depressive symptoms in healthy volunteers, with a moderately large effect. 7

Although mood itself can affect our food choices, plausible mechanisms exist by which high consumption of processed carbohydrates could increase the risk of depression and anxiety—for example, through repeated and rapid increases and decreases in blood glucose. Measures of glycaemic index and glycaemic load can be used to estimate glycaemia and insulin demand in healthy individuals after eating. 8 Thus, high dietary glycaemic load, and the resultant compensatory responses, could lower plasma glucose to concentrations that trigger the secretion of autonomic counter-regulatory hormones such as cortisol, adrenaline, growth hormone, and glucagon. 5 9 The potential effects of this response on mood have been examined in experimental human research of stepped reductions in plasma glucose concentrations conducted under laboratory conditions through glucose perfusion. These findings showed that such counter-regulatory hormones may cause changes in anxiety, irritability, and hunger. 10 In addition, observational research has found that recurrent hypoglycaemia (low blood sugar) is associated with mood disorders. 9

The hypothesis that repeated and rapid increases and decreases in blood glucose explain how consumption of refined carbohydrate could affect psychological state appears to be a good fit given the relatively fast effect of diets with a high glycaemic index or load on depressive symptoms observed in human studies. 7 However, other processes may explain the observed relationships. For instance, diets with a high glycaemic index are a risk factor for diabetes, 5 which is often a comorbid condition with depression. 4 11 While the main models of disease pathophysiology in diabetes and mental illness are separate, common abnormalities in insulin resistance, brain volume, and neurocognitive performance in both conditions support the hypothesis that these conditions have overlapping pathophysiology. 12 Furthermore, the inflammatory response to foods with a high glycaemic index 13 raises the possibility that diets with a high glycaemic index are associated with symptoms of depression through the broader connections between mental health and immune activation.

Diet, immune activation, and depression

Studies have found that sustained adherence to Mediterranean dietary patterns can reduce markers of inflammation in humans. 14 On the other hand, high calorie meals rich in saturated fat appear to stimulate immune activation. 13 15 Indeed, the inflammatory effects of a diet high in calories and saturated fat have been proposed as one mechanism through which the Western diet may have detrimental effects on brain health, including cognitive decline, hippocampal dysfunction, and damage to the blood-brain barrier. 15 Since various mental health conditions, including mood disorders, have been linked to heightened inflammation, 16 this mechanism also presents a pathway through which poor diet could increase the risk of depression. This hypothesis is supported by observational studies which have shown that people with depression score significantly higher on measures of “dietary inflammation,” 3 17 characterised by a greater consumption of foods that are associated with inflammation (eg, trans fats and refined carbohydrates) and lower intakes of nutritional foods, which are thought to have anti-inflammatory properties (eg, omega-3 fats). However, the causal roles of dietary inflammation in mental health have not yet been established.

Nonetheless, randomised controlled trials of anti-inflammatory agents (eg, cytokine inhibitors and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) have found that these agents can significantly reduce depressive symptoms. 18 Specific nutritional components (eg, polyphenols and polyunsaturated fats) and general dietary patterns (eg, consumption of a Mediterranean diet) may also have anti-inflammatory effects, 14 19 20 which raises the possibility that certain foods could relieve or prevent depressive symptoms associated with heightened inflammatory status. 21 A recent study provides preliminary support for this possibility. 20 The study shows that medications that stimulate inflammation typically induce depressive states in people treated, and that giving omega-3 fatty acids, which have anti-inflammatory properties, before the medication seems to prevent the onset of cytokine induced depression. 20

However, the complexity of the hypothesised three way relation between diet, inflammation, and depression is compounded by several important modifiers. For example, recent clinical research has observed that stressors experienced the previous day, or a personal history of major depressive disorders, may cancel out the beneficial effects of healthy food choices on inflammation and mood. 22 Furthermore, as heightened inflammation occurs in only some clinically depressed individuals, anti-inflammatory interventions may only benefit certain people characterised by an “inflammatory phenotype,” or those with comorbid inflammatory conditions. 18 Further interventional research is needed to establish if improvements in immune regulation, induced by diet, can reduce depressive symptoms in those affected by inflammatory conditions.

Brain, gut microbiome, and mood

A more recent explanation for the way in which our food may affect our mental wellbeing is the effect of dietary patterns on the gut microbiome—a broad term that refers to the trillions of microbial organisms, including bacteria, viruses, and archaea, living in the human gut. The gut microbiome interacts with the brain in bidirectional ways using neural, inflammatory, and hormonal signalling pathways. 23 The role of altered interactions between the brain and gut microbiome on mental health has been proposed on the basis of the following evidence: emotion-like behaviour in rodents changes with changes in the gut microbiome, 24 major depressive disorder in humans is associated with alterations of the gut microbiome, 25 and transfer of faecal gut microbiota from humans with depression into rodents appears to induce animal behaviours that are hypothesised to indicate depression-like states. 25 26 Such findings suggest a role of altered neuroactive microbial metabolites in depressive symptoms.

In addition to genetic factors and exposure to antibiotics, diet is a potentially modifiable determinant of the diversity, relative abundance, and functionality of the gut microbiome throughout life. For instance, the neurocognitive effects of the Western diet, and the possible mediating role of low grade systemic immune activation (as discussed above) may result from a compromised mucus layer with or without increased epithelial permeability. Such a decrease in the function of the gut barrier is sometimes referred to as a “leaky gut” and has been linked to an “unhealthy” gut microbiome resulting from a diet low in fibre and high in saturated fats, refined sugars, and artificial sweeteners. 15 23 27 Conversely, the consumption of a diet high in fibres, polyphenols, and unsaturated fatty acids (as found in a Mediterranean diet) can promote gut microbial taxa which can metabolise these food sources into anti-inflammatory metabolites, 15 28 such as short chain fatty acids, while lowering the production of secondary bile acids and p-cresol. Moreover, a recent study found that the ingestion of probiotics by healthy individuals, which theoretically target the gut microbiome, can alter the brain’s response to a task that requires emotional attention 29 and may even reduce symptoms of depression. 30 When viewed together, these studies provide promising evidence supporting a role of the gut microbiome in modulating processes that regulate emotion in the human brain. However, no causal relationship between specific microbes, or their metabolites, and complex human emotions has been established so far. Furthermore, whether changes to the gut microbiome induced by diet can affect depressive symptoms or clinical depressive disorders, and the time in which this could feasibly occur, remains to be shown.

Priorities and next steps

In moving forward within this active field of research, it is firstly important not to lose sight of the wood for the trees—that is, become too focused on the details and not pay attention to the bigger questions. Whereas discovering the anti-inflammatory properties of a single nutrient or uncovering the subtleties of interactions between the gut and the brain may shed new light on how food may influence mood, it is important not to neglect the existing knowledge on other ways diet may affect mental health. For example, the later consequences of a poor diet include obesity and diabetes, which have already been shown to be associated with poorer mental health. 11 31 32 33 A full discussion of the effect of these comorbidities is beyond the scope of our article (see fig 1 ), but it is important to acknowledge that developing public health initiatives that effectively tackle the established risk factors of physical and mental comorbidities is a priority for improving population health.

Further work is needed to improve our understanding of the complex pathways through which diet and nutrition can influence the brain. Such knowledge could lead to investigations of targeted, even personalised, interventions to improve mood, anxiety, or other symptoms through nutritional approaches. However, these possibilities are speculative at the moment, and more interventional research is needed to establish if, how, and when dietary interventions can be used to prevent mental illness or reduce symptoms in those living with such conditions. Of note, a recent large clinical trial found no significant benefits of a behavioural intervention promoting a Mediterranean diet for adults with subclinical depressive symptoms. 34 On the other hand, several recent smaller trials in individuals with current depression observed moderately large improvements from interventions based on the Mediterranean diet. 35 36 37 Such results, however, must be considered within the context of the effect of people’s expectations, particularly given that individuals’ beliefs about the quality of their food or diet may also have a marked effect on their sense of overall health and wellbeing. 38 Nonetheless, even aside from psychological effects, consideration of dietary factors within mental healthcare may help improve physical health outcomes, given the higher rates of cardiometabolic diseases observed in people with mental illness. 33

At the same time, it is important to be remember that the causes of mental illness are many and varied, and they will often present and persist independently of nutrition and diet. Thus, the increased understanding of potential connections between food and mental wellbeing should never be used to support automatic assumptions, or stigmatisation, about an individual’s dietary choices and their mental health. Indeed, such stigmatisation could be itself be a casual pathway to increasing the risk of poorer mental health. Nonetheless, a promising message for public health and clinical settings is emerging from the ongoing research. This message supports the idea that creating environments and developing measures that promote healthy, nutritious diets, while decreasing the consumption of highly processed and refined “junk” foods may provide benefits even beyond the well known effects on physical health, including improved psychological wellbeing.

Contributors and sources: JF has expertise in the interaction between physical and mental health, particularly the role of lifestyle and behavioural health factors in mental health promotion. JEG’s area of expertise is the study of the relationship between sleep duration, nutrition, psychiatric disorders, and cardiometabolic diseases. AB leads research investigating the molecular mechanisms underlying the effect of stress and inflammation on human hippocampal neurogenesis, and how nutritional components and their metabolites can prevent changes induced by those conditions. REW has expertise in genetic epidemiology approaches to examining casual relations between health behaviours and mental illness. EAM has expertise in brain and gut interactions and microbiome interactions. All authors contributed to, read, and approved the paper, and all the information was sourced from articles published in peer reviewed research journals. JF is the guarantor.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following: JF is supported by a University of Manchester Presidential Fellowship and a UK Research and Innovation Future Leaders Fellowship and has received support from a NICM-Blackmores Institute Fellowship. JEG served on the medical advisory board on insomnia in the cardiovascular patient population for the drug company Eisai. AB has received research funding from Johnson & Johnson for research on depression and inflammation, the UK Medical Research Council, the European Commission Horizon 2020, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, and King’s College London. REW receives funding from the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at the University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol. EAM has served on the external advisory boards of Danone, Viome, Amare, Axial Biotherapeutics, Pendulum, Ubiome, Bloom Science, Mahana Therapeutics, and APC Microbiome Ireland, and he receives royalties from Harper & Collins for his book The Mind Gut Connection. He is supported by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and the US Department of Defense. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the organisations above.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This article is part of series commissioned by The BMJ. Open access fees are paid by Swiss Re, which had no input into the commissioning or peer review of the articles. T he BMJ thanks the series advisers, Nita Forouhi, Dariush Mozaffarian, and Anna Lartey for valuable advice and guiding selection of topics in the series.

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- News & Views

- Food and mood: how do...

Food and mood: how do diet and nutrition affect mental wellbeing?

Read our food for thought 2020 collection.

- Related content

- Peer review

This article has a correction. Please see:

- Food and mood: how do diet and nutrition affect mental wellbeing? - November 09, 2020

- Joseph Firth , research fellow 1 2 ,

- James E Gangwisch , assistant professor 3 4 ,

- Alessandra Borsini , researcher 5 ,

- Robyn E Wootton , researcher 6 7 8 ,

- Emeran A Mayer , professor 9 10

- 1 Division of Psychology and Mental Health, Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health, Oxford Road, University of Manchester, Manchester M13 9PL, UK

- 2 NICM Health Research Institute, Western Sydney University, Westmead, Australia

- 3 Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, USA

- 4 New York State Psychiatric Institute, New York, NY, USA

- 5 Section of Stress, Psychiatry and Immunology Laboratory, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, Department of Psychological Medicine, King’s College London, London, UK

- 6 School of Psychological Science, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK

- 7 MRC Integrative Epidemiology Unit, Oakfield House, Bristol, UK

- 8 NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust and University of Bristol, Bristol, UK

- 9 G Oppenheimer Center for Neurobiology of Stress and Resilience, UCLA Vatche and Tamar Manoukian Division of Digestive Diseases, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA

- 10 UCLA Microbiome Center, David Geffen School of Medicine, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA

- Correspondence to: J Firth joseph.firth{at}manchester.ac.uk

Poor nutrition may be a causal factor in the experience of low mood, and improving diet may help to protect not only the physical health but also the mental health of the population, say Joseph Firth and colleagues

Key messages

Healthy eating patterns, such as the Mediterranean diet, are associated with better mental health than “unhealthy” eating patterns, such as the Western diet

The effects of certain foods or dietary patterns on glycaemia, immune activation, and the gut microbiome may play a role in the relationships between food and mood

More research is needed to understand the mechanisms that link food and mental wellbeing and determine how and when nutrition can be used to improve mental health

Depression and anxiety are the most common mental health conditions worldwide, making them a leading cause of disability. 1 Even beyond diagnosed conditions, subclinical symptoms of depression and anxiety affect the wellbeing and functioning of a large proportion of the population. 2 Therefore, new approaches to managing both clinically diagnosed and subclinical depression and anxiety are needed.

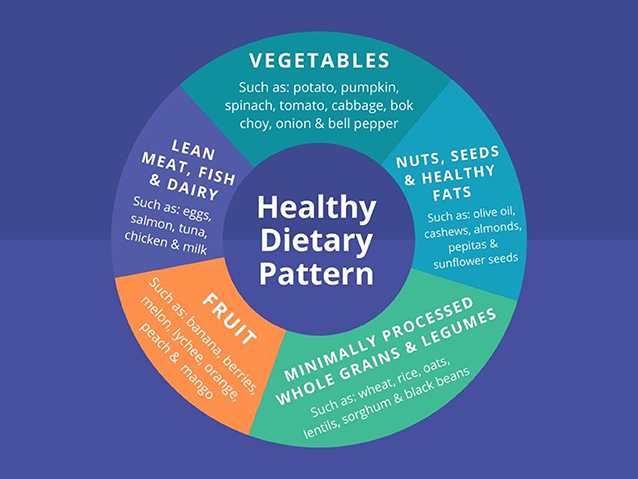

In recent years, the relationships between nutrition and mental health have gained considerable interest. Indeed, epidemiological research has observed that adherence to healthy or Mediterranean dietary patterns—high consumption of fruits, vegetables, nuts, and legumes; moderate consumption of poultry, eggs, and dairy products; and only occasional consumption of red meat—is associated with a reduced risk of depression. 3 However, the nature of these relations is complicated by the clear potential for reverse causality between diet and mental health ( fig 1 ). For example, alterations in food choices or preferences in response to our temporary psychological state—such as “comfort foods” in times of low mood, or changes in appetite from stress—are common human experiences. In addition, relationships between nutrition and longstanding mental illness are compounded by barriers to maintaining a healthy diet. These barriers disproportionality affect people with mental illness and include the financial and environmental determinants of health, and even the appetite inducing effects of psychiatric medications. 4

Hypothesised relationship between diet, physical health, and mental health. The dashed line is the focus of this article.

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

While acknowledging the complex, multidirectional nature of the relationships between diet and mental health ( fig 1 ), in this article we focus on the ways in which certain foods and dietary patterns could affect mental health.

Mood and carbohydrates

Consumption of highly refined carbohydrates can increase the risk of obesity and diabetes. 5 Glycaemic index is a relative ranking of carbohydrate in foods according to the speed at which they are digested, absorbed, metabolised, and ultimately affect blood glucose and insulin levels. As well as the physical health risks, diets with a high glycaemic index and load (eg, diets containing high amounts of refined carbohydrates and sugars) may also have a detrimental effect on psychological wellbeing; data from longitudinal research show an association between progressively higher dietary glycaemic index and the incidence of depressive symptoms. 6 Clinical studies have also shown potential causal effects of refined carbohydrates on mood; experimental exposure to diets with a high glycaemic load in controlled settings increases depressive symptoms in healthy volunteers, with a moderately large effect. 7

Although mood itself can affect our food choices, plausible mechanisms exist by which high consumption of processed carbohydrates could increase the risk of depression and anxiety—for example, through repeated and rapid increases and decreases in blood glucose. Measures of glycaemic index and glycaemic load can be used to estimate glycaemia and insulin demand in healthy individuals after eating. 8 Thus, high dietary glycaemic load, and the resultant compensatory responses, could lower plasma glucose to concentrations that trigger the secretion of autonomic counter-regulatory hormones such as cortisol, adrenaline, growth hormone, and glucagon. 5 9 The potential effects of this response on mood have been examined in experimental human research of stepped reductions in plasma glucose concentrations conducted under laboratory conditions through glucose perfusion. These findings showed that such counter-regulatory hormones may cause changes in anxiety, irritability, and hunger. 10 In addition, observational research has found that recurrent hypoglycaemia (low blood sugar) is associated with mood disorders. 9

The hypothesis that repeated and rapid increases and decreases in blood glucose explain how consumption of refined carbohydrate could affect psychological state appears to be a good fit given the relatively fast effect of diets with a high glycaemic index or load on depressive symptoms observed in human studies. 7 However, other processes may explain the observed relationships. For instance, diets with a high glycaemic index are a risk factor for diabetes, 5 which is often a comorbid condition with depression. 4 11 While the main models of disease pathophysiology in diabetes and mental illness are separate, common abnormalities in insulin resistance, brain volume, and neurocognitive performance in both conditions support the hypothesis that these conditions have overlapping pathophysiology. 12 Furthermore, the inflammatory response to foods with a high glycaemic index 13 raises the possibility that diets with a high glycaemic index are associated with symptoms of depression through the broader connections between mental health and immune activation.

Diet, immune activation, and depression

Studies have found that sustained adherence to Mediterranean dietary patterns can reduce markers of inflammation in humans. 14 On the other hand, high calorie meals rich in saturated fat appear to stimulate immune activation. 13 15 Indeed, the inflammatory effects of a diet high in calories and saturated fat have been proposed as one mechanism through which the Western diet may have detrimental effects on brain health, including cognitive decline, hippocampal dysfunction, and damage to the blood-brain barrier. 15 Since various mental health conditions, including mood disorders, have been linked to heightened inflammation, 16 this mechanism also presents a pathway through which poor diet could increase the risk of depression. This hypothesis is supported by observational studies which have shown that people with depression score significantly higher on measures of “dietary inflammation,” 3 17 characterised by a greater consumption of foods that are associated with inflammation (eg, trans fats and refined carbohydrates) and lower intakes of nutritional foods, which are thought to have anti-inflammatory properties (eg, omega-3 fats). However, the causal roles of dietary inflammation in mental health have not yet been established.

Nonetheless, randomised controlled trials of anti-inflammatory agents (eg, cytokine inhibitors and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) have found that these agents can significantly reduce depressive symptoms. 18 Specific nutritional components (eg, polyphenols and polyunsaturated fats) and general dietary patterns (eg, consumption of a Mediterranean diet) may also have anti-inflammatory effects, 14 19 20 which raises the possibility that certain foods could relieve or prevent depressive symptoms associated with heightened inflammatory status. 21 A recent study provides preliminary support for this possibility. 20 The study shows that medications that stimulate inflammation typically induce depressive states in people treated, and that giving omega-3 fatty acids, which have anti-inflammatory properties, before the medication seems to prevent the onset of cytokine induced depression. 20

However, the complexity of the hypothesised three way relation between diet, inflammation, and depression is compounded by several important modifiers. For example, recent clinical research has observed that stressors experienced the previous day, or a personal history of major depressive disorders, may cancel out the beneficial effects of healthy food choices on inflammation and mood. 22 Furthermore, as heightened inflammation occurs in only some clinically depressed individuals, anti-inflammatory interventions may only benefit certain people characterised by an “inflammatory phenotype,” or those with comorbid inflammatory conditions. 18 Further interventional research is needed to establish if improvements in immune regulation, induced by diet, can reduce depressive symptoms in those affected by inflammatory conditions.

Brain, gut microbiome, and mood

A more recent explanation for the way in which our food may affect our mental wellbeing is the effect of dietary patterns on the gut microbiome—a broad term that refers to the trillions of microbial organisms, including bacteria, viruses, and archaea, living in the human gut. The gut microbiome interacts with the brain in bidirectional ways using neural, inflammatory, and hormonal signalling pathways. 23 The role of altered interactions between the brain and gut microbiome on mental health has been proposed on the basis of the following evidence: emotion-like behaviour in rodents changes with changes in the gut microbiome, 24 major depressive disorder in humans is associated with alterations of the gut microbiome, 25 and transfer of faecal gut microbiota from humans with depression into rodents appears to induce animal behaviours that are hypothesised to indicate depression-like states. 25 26 Such findings suggest a role of altered neuroactive microbial metabolites in depressive symptoms.

In addition to genetic factors and exposure to antibiotics, diet is a potentially modifiable determinant of the diversity, relative abundance, and functionality of the gut microbiome throughout life. For instance, the neurocognitive effects of the Western diet, and the possible mediating role of low grade systemic immune activation (as discussed above) may result from a compromised mucus layer with or without increased epithelial permeability. Such a decrease in the function of the gut barrier is sometimes referred to as a “leaky gut” and has been linked to an “unhealthy” gut microbiome resulting from a diet low in fibre and high in saturated fats, refined sugars, and artificial sweeteners. 15 23 27 Conversely, the consumption of a diet high in fibres, polyphenols, and unsaturated fatty acids (as found in a Mediterranean diet) can promote gut microbial taxa which can metabolise these food sources into anti-inflammatory metabolites, 15 28 such as short chain fatty acids, while lowering the production of secondary bile acids and p-cresol. Moreover, a recent study found that the ingestion of probiotics by healthy individuals, which theoretically target the gut microbiome, can alter the brain’s response to a task that requires emotional attention 29 and may even reduce symptoms of depression. 30 When viewed together, these studies provide promising evidence supporting a role of the gut microbiome in modulating processes that regulate emotion in the human brain. However, no causal relationship between specific microbes, or their metabolites, and complex human emotions has been established so far. Furthermore, whether changes to the gut microbiome induced by diet can affect depressive symptoms or clinical depressive disorders, and the time in which this could feasibly occur, remains to be shown.

Priorities and next steps

In moving forward within this active field of research, it is firstly important not to lose sight of the wood for the trees—that is, become too focused on the details and not pay attention to the bigger questions. Whereas discovering the anti-inflammatory properties of a single nutrient or uncovering the subtleties of interactions between the gut and the brain may shed new light on how food may influence mood, it is important not to neglect the existing knowledge on other ways diet may affect mental health. For example, the later consequences of a poor diet include obesity and diabetes, which have already been shown to be associated with poorer mental health. 11 31 32 33 A full discussion of the effect of these comorbidities is beyond the scope of our article (see fig 1 ), but it is important to acknowledge that developing public health initiatives that effectively tackle the established risk factors of physical and mental comorbidities is a priority for improving population health.

Further work is needed to improve our understanding of the complex pathways through which diet and nutrition can influence the brain. Such knowledge could lead to investigations of targeted, even personalised, interventions to improve mood, anxiety, or other symptoms through nutritional approaches. However, these possibilities are speculative at the moment, and more interventional research is needed to establish if, how, and when dietary interventions can be used to prevent mental illness or reduce symptoms in those living with such conditions. Of note, a recent large clinical trial found no significant benefits of a behavioural intervention promoting a Mediterranean diet for adults with subclinical depressive symptoms. 34 On the other hand, several recent smaller trials in individuals with current depression observed moderately large improvements from interventions based on the Mediterranean diet. 35 36 37 Such results, however, must be considered within the context of the effect of people’s expectations, particularly given that individuals’ beliefs about the quality of their food or diet may also have a marked effect on their sense of overall health and wellbeing. 38 Nonetheless, even aside from psychological effects, consideration of dietary factors within mental healthcare may help improve physical health outcomes, given the higher rates of cardiometabolic diseases observed in people with mental illness. 33

At the same time, it is important to be remember that the causes of mental illness are many and varied, and they will often present and persist independently of nutrition and diet. Thus, the increased understanding of potential connections between food and mental wellbeing should never be used to support automatic assumptions, or stigmatisation, about an individual’s dietary choices and their mental health. Indeed, such stigmatisation could be itself be a casual pathway to increasing the risk of poorer mental health. Nonetheless, a promising message for public health and clinical settings is emerging from the ongoing research. This message supports the idea that creating environments and developing measures that promote healthy, nutritious diets, while decreasing the consumption of highly processed and refined “junk” foods may provide benefits even beyond the well known effects on physical health, including improved psychological wellbeing.

Contributors and sources: JF has expertise in the interaction between physical and mental health, particularly the role of lifestyle and behavioural health factors in mental health promotion. JEG’s area of expertise is the study of the relationship between sleep duration, nutrition, psychiatric disorders, and cardiometabolic diseases. AB leads research investigating the molecular mechanisms underlying the effect of stress and inflammation on human hippocampal neurogenesis, and how nutritional components and their metabolites can prevent changes induced by those conditions. REW has expertise in genetic epidemiology approaches to examining casual relations between health behaviours and mental illness. EAM has expertise in brain and gut interactions and microbiome interactions. All authors contributed to, read, and approved the paper, and all the information was sourced from articles published in peer reviewed research journals. JF is the guarantor.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following: JF is supported by a University of Manchester Presidential Fellowship and a UK Research and Innovation Future Leaders Fellowship and has received support from a NICM-Blackmores Institute Fellowship. JEG served on the medical advisory board on insomnia in the cardiovascular patient population for the drug company Eisai. AB has received research funding from Johnson & Johnson for research on depression and inflammation, the UK Medical Research Council, the European Commission Horizon 2020, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, and King’s College London. REW receives funding from the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at the University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Bristol. EAM has served on the external advisory boards of Danone, Viome, Amare, Axial Biotherapeutics, Pendulum, Ubiome, Bloom Science, Mahana Therapeutics, and APC Microbiome Ireland, and he receives royalties from Harper & Collins for his book The Mind Gut Connection. He is supported by grants from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and the US Department of Defense. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the organisations above.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This article is part of series commissioned by The BMJ. Open access fees are paid by Swiss Re, which had no input into the commissioning or peer review of the articles. T he BMJ thanks the series advisers, Nita Forouhi, Dariush Mozaffarian, and Anna Lartey for valuable advice and guiding selection of topics in the series.

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

- Friedrich MJ

- Johnson J ,

- Weissman MM ,

- Lassale C ,

- Baghdadli A ,

- Siddiqi N ,

- Koyanagi A ,

- Gangwisch JE ,

- Salari-Moghaddam A ,

- Larijani B ,

- Esmaillzadeh A

- de Jong V ,

- Atkinson F ,

- Brand-Miller JC

- Seaquist ER ,

- Anderson J ,

- American Diabetes Association ,

- Endocrine Society

- Towler DA ,

- Havlin CE ,

- McIntyre RS ,

- Nguyen HT ,

- O’Keefe JH ,

- Gheewala NM ,

- Kastorini C-M ,

- Milionis HJ ,

- Esposito K ,

- Giugliano D ,

- Goudevenos JA ,

- Panagiotakos DB

- Teasdale SB ,

- Köhler-Forsberg O ,

- N Lydholm C ,

- Hjorthøj C ,

- Nordentoft M ,

- Yahfoufi N ,

- Borsini A ,

- Horowitz MA ,

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK ,

- Fagundes CP ,

- Andridge R ,

- Osadchiy V ,

- Martin CR ,

- O’Brien C ,

- Sonnenburg ED ,

- Sonnenburg JL

- Rampelli S ,

- Jeffery IB ,

- Tillisch K ,

- Kilpatrick L ,

- Walsh RFL ,

- Wootton RE ,

- Millard LAC ,

- Jebeile H ,

- Garnett SP ,

- Paxton SJ ,

- Brouwer IA ,

- MooDFOOD Prevention Trial Investigators

- Francis HM ,

- Stevenson RJ ,

- Chambers JR ,

- Parletta N ,

- Zarnowiecki D ,

- Fischler C ,

- Sarubin A ,

- Wrzesniewski A

- Harrington D ,

Frontiers for Young Minds

- Download PDF

Nutrition and Mental Health—How the Food We Eat Can Affect Our Mood

Food is vital for our survival, it gives us energy, helps us grow, and keeps us healthy. But can it also affect our mood? Science says it can. In the past, a great deal of research has explored how food can affect our physical health. Although this is important, exciting research is now exploring how food can influence our mood and our mental health. Mental health conditions, such as depression affect a significant number of people. This makes research into the effects of food and mood crucial, as food may offer a strategy to help prevent people from getting depression and also help them when they already have depression. Although we are not yet able to explain the exact ways in which food may affect our mood, this research has the potential to decrease the number of people who suffer from mental health conditions, such as depression.

What is Depression?

Depression is a type of illness that influences how we feel. It may develop slowly over time with no external cause and, unlike a physical injury or illness, we cannot always see it just by looking at someone. This is because depression affects the parts of the brain that control how we feel. Diseases that affect our feelings, thoughts and behaviors are called mental illnesses, so depression is a type of mental illness.

We all have times when we feel happy or sad. However, for someone with depression, the feelings of sadness or low mood do not go away. Depression is more than just being sad or down, or losing interest in activities that were once enjoyed, and it can affect everyone in a different way—symptoms are often unique to each individual. A person might, for instance, feel tired all the time and not have much energy, or might find it hard to concentrate. A depressed person may have changes in sleep patterns, have feelings of guilt or low self-worth, or even have changes in appetite [ 1 ]. Symptoms can vary in severity, from rather minor depressive symptoms up to something called major depressive disorder (MDD) , which is a diagnosed clinical condition where multiple symptoms may last for a long time.

Depression is an important mental illness to study, because it affects more than 300 million people from all around the world [ 1 ]. It is one of the most common mental health conditions and can affect both men and women [ 1 ]. In fact, it is predicted that depression will be the number one health concern in the world by the year 2030 [ 2 ]. These statistics show just how important it is to find ways to help prevent people from developing depression and to help people who already have depression.

There are currently a number of ways depression can be treated. One method includes taking a variety of medications. Another includes talking to specialists, such as psychologists, who are trained in treating mental health issues. Although these methods can be effective, there are many people who cannot access these treatments because of where they live, their income, the availability of specialists, or stigma and shame [ 1 ]. Even when people do have access to these treatment methods, some people who try them do not recover completely [ 1 , 3 ]. For this reason, it is important to find other ways to help people with depression. For example, the food that we eat is one factor that might influence our mental health and our mood.

What is Nutrition?

There are many different components that make up the food that we eat. These include a range of nutrients and chemicals, such as macro and micronutrients. Macronutrients are nutrients we need a lot of in our diets and they include carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. Micronutrients are nutrients we need in smaller amounts and they include vitamins and minerals. Along with these nutrients, there are many other important components of food including fiber, water, and antioxidants . These components work together to contribute to the healthy functioning of the human body.

The food we eat can give us energy, help us grow, and keep us healthy—but nutrition involves much more than this. The field of nutrition considers whether people can access and afford to buy food, how foods vary across different cultures, and why we choose to eat the foods that we do. In fact, new ideas about the effects of food are being explored all the time. One idea that is of great importance is how the food we eat can affect our mood. It is possible that the components in food, such as vitamins and minerals, can influence depression. It also explores how depression can influence our food choices [ 4 ]. Figure 1 highlights the connections between what we eat and our mental and physical health.

- Figure 1 - Dietary improvement can lead to better mental health and better physical health.

- Mental health and physical health also affect each other.

Food and Mood

Researchers have looked at the connection between diet and depression, and there is now a great deal of evidence suggesting that what we eat every day can influence our mood [ 4 , 5 ]. This research shows that a healthy dietary pattern, such as a Mediterranean-style diet, can have a positive effect on mental health [ 4 , 5 ]. A typical healthy diet pattern is shown in Figure 2 . This includes plenty of vegetables, fruit, nuts, seeds, and olive oil, as well as minimally processed whole grains, legumes, and moderate amounts of lean meat, fish, and dairy. A healthy diet is also low in added sugar and saturated and trans fats , and is high in fiber and antioxidants [ 3 ].

- Figure 2 - A typical healthy dietary pattern includes vegetables, fruit, whole grains, lean meats, dairy, and healthy fats.

Recent studies have explored the link between this healthy dietary pattern and depression. These studies collected information from a large number of people over time. This dietary research has shown a link between unhealthy dietary patterns and symptoms of depression. An unhealthy diet contains mainly ultra-processed foods , including sugar-sweetened beverages, such as soft drinks and packaged snacks that are high in added sugar, salt, and saturated and trans fats. The discovery of this link between diet and depression is important because it suggests that following a healthy dietary pattern over time could possibly prevent depression [ 4 , 5 ].

Other research has shown that a healthy dietary pattern may be able to treat depression. This research looked at the effect of a healthy dietary pattern on people who already had depression. In this Australian study, the researchers compared the results of two different groups of people with depression. Only one group was taught how to follow a healthy dietary pattern. Researchers then looked to see if the changes in their diets improved their mood compared with the group that was not taught to follow a healthy diet. The study showed that people who followed a healthy dietary pattern for 3 months reduced their symptoms of depression [ 5 ].

Why Does Food Help With Depression?

We are not yet able to explain exactly how food may positively affect our mood. However, there are a number of theories as to why this might be the case. Some theories explore the function of different components of food, such as vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants. These theories focus on the role these micronutrients play in contributing to the healthy functioning of the human body. Other theories look at the importance of the microorganisms that live in the gut, called the gut microbiome , and how the foods we eat can affect this microbiome. Lastly, other theories suggest that the changes in behavior that happen when people start to eat a healthy diet may provide the beneficial effects on mood. These behavioral changes could include cooking more at home or cooking and eating in a social setting [ 5 ]. The positive experiences associated with the cultural and social aspect of food may help with depressive symptoms. Remember, nutrition is more than just food giving us energy, keeping us healthy and helping us grow—it is also about foods from different cultures, and why we choose to eat the foods that we do. Therefore, cooking in a social setting may not only influence food choice but may also contribute to a positive food experience and a healthy social environment. Cooking more at home may also help to promote more frequent, healthier food choices.

Finally, there are some studies that look at more specific diets (such as a vegetarian diet) and mental health, but this is not something that has been explored in great detail yet. It would be interesting if more research were done on this subject in the future.

Summary: The Food We Eat Can Affect Our Mood

In conclusion, the food we eat is not only important for our physical health, but also for our mental health. Although more studies are needed to help understand how and why this may be the case, there is now plenty of research that shows what we eat can influence our mood. This suggests diet may be able to play an important role in the prevention and treatment of depression, one of the most common mental health conditions in the world.

Author Contributions

ME drafted the manuscript and approved the final version. JF contributed to the drafting of the manuscript and has approved the final version. JS contributed to the drafting of the manuscript and has approved the final version.

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) : ↑ A type of depressive disorder, otherwise known as clinical depression, that may be mild, moderate or severe.

Mental Health : ↑ A person’s psychological and emotional well-being.

Antioxidants : ↑ Plant compounds that protect cells from damage.

Nutrition : ↑ The science that looks at the effects of food on the human body.

Trans Fat : ↑ A type of fat that has been shown by researchers to be unhealthy for your heart.

Ultra-processed Foods : ↑ Foods that have been highly manipulated and have ingredients added that are not usually used in cooking, such as artificial colors and flavors.

Gut Microbiome : ↑ The community of different bacteria and microorganisms living in the intestine.

Conflict of Interest

JF is supported by a University of Manchester Presidential Fellowship (P123958) and a UK Research and Innovation Future Leaders Fellowship (MR/T021780/1) and has received support from a NICM-Blackmores Institute Fellowship. JS has received either presentation honoraria, travel support, clinical trial grants, book royalties, or independent consultancy payments from: Integria Healthcare & MediHerb, Pfizer, Scius Health, Key Pharmaceuticals, Taki Mai, FIT-BioCeuticals, Blackmores, Soho-Flordis, Healthworld, HealthEd, HealthMasters, Kantar Consulting, Grunbiotics, Research Reviews, Elsevier, Chaminade University, International Society for Affective Disorders, Complementary Medicines Australia, SPRIM, Terry White Chemists, ANS, Society for Medicinal Plant and Natural Product Research, Sanofi-Aventis, Omega-3 Center, the National Health and Medical Research Council, CR Roper Fellowship.

The remaining author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

[1] ↑ Lim, G. Y., Tam, W. W., Lu, Y., Ho, C. S., Zhang, M. W., and Ho, R. C. 2018. Prevalence of depression in the community from 30 countries between 1994 and 2014. Sci. Rep. 8:2861. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21243-x

[2] ↑ World Health Organization. 2008. The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update. Geneva: World Health Organization.

[3] ↑ Firth, J., Marx, W., Dash, S., Carney, R., Teasdale, S. B., Solmi, M., et al. 2019. The effects of dietary improvement on symptoms of depression and anxiety: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychosom. Med. 81:265. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000673

[4] ↑ Sarris, J., Logan, A. C., Akbaraly, T. N., Paul Amminger, G., Balanzá-Martínez, V., Freeman, M. P., et al. 2015. International Society for Nutritional Psychiatry Research consensus position statement: nutritional medicine in modern psychiatry. World Psychiatry . 14:370–1. doi: 10.1002/wps.20223

[5] ↑ Jacka, F. N., O'Neil, A., Opie, R., Itsiopoulos, C., Cotton, S., Mohebbi, M., et al. 2017. A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the ‘SMILES’ trial). BMC Med .. 15:23. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0791-y

Home — Essay Samples — Nursing & Health — Eating Habits — Nutrition, Exercise, and Mental Health: An Interconnected Analysis

Nutrition, Exercise, and Mental Health: an Interconnected Analysis

- Categories: Eating Habits Mental Health Physical Exercise

About this sample

Words: 3151 |

16 min read

Published: May 17, 2022

Words: 3151 | Pages: 7 | 16 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, concluding remarks and discussion, what are branched-chain amino acids, uses for bcaas in physically active individuals, bcaas in low protein diets, future research for deficient diets and fat loss.

- Du, Y., Meng, Q., Zhang, Q., & Guo, F. (2011). Isoleucine or valine deprivation stimulates fat loss via increasing energy expenditure and regulating lipid metabolism in WAT. Amino Acids, 43(2), 725-734. doi:10.1007/s00726-011-1123-8

- Dudgeon, W. D., Kelly, E. P., & Scheett, T. P. (2016). In a single-blind, matched group design: Branched-chain amino acid supplementation and resistance training maintains lean body mass during a caloric restricted diet. Journal of the Society of Sports Nutrition, 13(1). doi:10.1186/s12970-015-0112-9

- Foure, A., & Bendahan, D. (2017). Is Branched-Chain Amino Acids Supplementation an Efficient Nutritional Strategy to Alleviate Skeletal Muscle Damage? A Systematic Review. Nutrients, 9(10), 1-15. doi:10.3390/nu9101047

- Gannon, Nicholas P., et al. “BCAA Metabolism and Insulin Sensitivity - Dysregulated by Metabolic Status?” Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, vol. 62, no. 6, 2018, p. 1700756., doi:10.1002/mnfr.201700756.

- Greer, Beau Kjerulf, et al. “Branched-Chain Amino Acid Supplementation and Indicators of Muscle Damage after Endurance Exercise.” International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, vol. 17, no. 6, 2007, pp. 595–607., doi:10.1123/ijsnem.17.6.595

- Holeček, Milan. “Branched-Chain Amino Acids in Health and Disease: Metabolism, Alterations in Blood Plasma, and as Supplements.” Nutrition & Metabolism, vol. 15, no. 1, 2018, doi:10.1186/s12986-018-0271-1.

- Koo, Ga Hee, et al. “Effects of Supplementation with BCAA and L-Glutamine on Blood Fatigue Factors and Cytokines in Juvenile Athletes Submitted to Maximal Intensity Rowing Performance.” Journal of Physical Therapy Science, vol. 26, no. 8, 30 Aug. 2014, pp. 1241–1246., doi:10.1589/jpts.26.1241.

- Pasiakos, S. M., Mcclung, H. L., Mcclung, J. P., Margolis, L. M., Andersen, N. E., Cloutier, G. J., . . . Young, A. J. (2011). Leucine-enriched essential amino acid supplementation during moderate steady state exercise enhances postexercise muscle protein synthesis. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 94(3), 809-818. doi:10.3945/ajcn.111.017061

- Pezeshki, A., Zapata, R. C., Singh, A., Yee, N. J., & Chelikani, P. K. (2016). 0476 Low protein diets produce divergent effects on energy balance. Journal of Animal Science, 94(5), 227-240. doi:10.2527/jam2016-0476

- Shimomura, Y., Murakami, T., Nakai, N., Nagasaki, M., & Harris, R. A. (2004). Exercise Promotes BCAA Catabolism: Effects of BCAA Supplementation on Skeletal Muscle during Exercise. The Journal of Nutrition, 134(6). doi:10.1093/jn/134.6.1583s

- Sowers, S. (2009). A Primer On Branched Chain Amino Acids [PDF]. Knoxville: Huntington College of Health Sciences.

- Wolfe R. R. (2017). Branched-chain amino acids and muscle protein synthesis in humans: myth or reality?. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 14, 30. doi:10.1186/s12970-017-0184-9

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Nursing & Health

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1398 words

2 pages / 1019 words

4 pages / 1775 words

1 pages / 371 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Eating Habits

Campbell, B., Kreider, R. B., Ziegenfuss, T., La Bounty, P., Roberts, M., Burke, D., ... & Antonio, J. (2007). International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: protein and exercise. Journal of the International Society [...]

Community health refers to the health status and outcomes of a community as a whole, encompassing a variety of factors such as access to healthcare, environmental conditions, and individual behaviors. The importance of enhancing [...]

Eating habits are an integral part of human life, as they directly impact our physical health, emotional well-being, and overall quality of life. As an individual, my eating habits have evolved over the years due to various [...]

Healthy carob bars have gained attention as a potential substitute for traditional chocolate products. As a college student studying marketing, it is important to recognize the potential of healthy carob bars and develop a [...]

Whatever healthful food does must for all, regardless of their age. Eating daily never means filling your stomach with anything. Eating nutritious does a topic with a deeper meaning. Moreover, it's an investment and art. Any [...]

Food insecurity is a complex and multifaceted issue that requires urgent attention and action. By understanding the causes and consequences of food insecurity, we can develop effective strategies and solutions to address this [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The effects of certain foods or dietary patterns on glycaemia, immune activation, and the gut microbiome may play a role in the relationships between food and mood. More research is needed to understand the mechanisms that link food and mental wellbeing and determine how and when nutrition can be used to improve mental health. 3 fig 1 4.

Poor nutrition may be a causal factor in the experience of low mood, and improving diet may help to protect not only the physical health but also the mental health of the population, say Joseph Firth and colleagues ### Key messages Depression and anxiety are the most common mental health conditions worldwide, making them a leading cause of disability.1 Even beyond diagnosed conditions ...

Can nutrition affect your mental health? A growing research literature suggests the answer could be yes. Western-style dietary habits, in particular, come under special scrutiny in much of this research. A meta-analysis including studies from 10 countries, conducted by researchers at Linyi People's Hospital in Shandong, China, suggests that ...

If your brain is deprived of good-quality nutrition, or if free radicals or damaging inflammatory cells are circulating within the brain's enclosed space, further contributing to brain tissue injury, consequences are to be expected. ... How the foods you eat affect your mental health. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter that helps regulate sleep ...

The purpose of the 2016 Nutrition Society Winter Meeting, 'Diet, nutrition and mental health and wellbeing' was to review where the evidence is strong, where there are unmet needs for research and to draw together the communities working in this area to share their findings. ... The papers presented demonstrated clear advancements that are ...

One idea that is of great importance is how the food we eat can affect our mood. It is possible that the components in food, such as vitamins and minerals, can influence depression. It also explores how depression can influence our food choices [ 4 ]. Figure 1 highlights the connections between what we eat and our mental and physical health.

Research interest in the impact of nutrition on mental health and well-being has been growing, and a poor diet may be the leading risk factor for poorer mental health [1, 2]. According to the ...

Health and W ell-Being: Insights From. the Literature. Maurizio Muscaritoli. Department of Translational and Precision Medicine, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy. A good nutritional status ...

Diet influences numerous aspects of health, including weight, athletic performance, and risk of chronic diseases, such as heart disease and type 2 diabetes. According to some research, it may ...

A review of the scientific evidence was conducted based on the available literature by typing in phrases related to nutrition and mental health using the methodological tool of the PubMed database ...

The brain consumes 20% of the daily intake of calories, that is, about 400 (out of 2000) calories a day. Structurally, about 60% of the brain is fat, comprising of high cholesterol and ...

Nutrition influences brain function at multiple levels, from molecular and cellular mechanisms to the complex neural networks that underlie human intelligence and mental health. Nutrition and the Brain - Exploring Pathways for Optimal Brain Health Through Nutrition: A Call for Papers - The Journal of Nutrition

large number of scientists and health professionals recognize that balanced nutrition is fundamental for a good state of physical health. The World Health Organization working group focused on nutrition as a key component of disease prevention, indicating that "a balanced and varied diet, composed of a wide range of nutritious and tasty foods ...

The relationship between nutrition and brain health is intricate. Studies suggest that nutrients during early life impact not only human physiology but also mental health. Although the exact molecular mechanisms that depict this relationship remain unclear, there are indications that environmental factors such as eating, lifestyle habits, stress, and physical activity, influence our genes and ...

Background: To address nutrition-related population mental health data gaps, we examined relationships among food insecurity, diet quality, and perceived mental health. Methods: Stratified and logistic regression analyses of respondents aged 19-70 years from the Canadian Community Health Survey, Cycle 2.2 were conducted (n = 15,546).

Mental health problems are believed to be the result of a combination of factors, including age, genetics and environmental factors. One of the most obvious, yet under-recognized factors in the development of major trends in mental health is the role of nutrition.(Associate Parliamentary & Health, 2008).

Food may s park rapid emotions by se nsory stimulation such as taste, savour. and smell, or re lief of hunger, but it can influence mood by slower changes in brain. chemistry as well (Shepherd ...

Introduction. As we all know that nutrition plays an important role in very individual's life. Proper physical activity and proper intake of nutrition are important in maintaining overall health and quality of life. As the research Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, regular exercise and proper nutrition can help maintain a proper weight and reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease ...

June 11, 2015. Effect Of Diet On Mental Health Development Introduction. Mental health problems are believed to be the result of a combination of factors, including age, genetics and environmental factors. One of the most obvious, yet under-recognized factors in the development of major trends in mental health is the role of nutrition .

Special Issue Information. Dear Colleagues, We are pleased to invite contributions of original research, reviews and meta-analyses to extend our understanding on body image, nutrition and mental health. Body image-related problems can play a key role in eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa; in obsessive-compulsive and ...

In conclusion, this area of health and nutrition still needs to further the research on the more specific areas and formulations of branched-chain amino acids for the purpose of fat loss with a low protein diet. Though some studies have shown that leucine, isoleucine, and valine all may have their individual thermogenic properties, science's main focus has been the aftercare of trained ...