Self Reflection Essay

What goes through your mind when you have to write a self reflection essay? Do you ponder on your life choices, the actions you take to get where you want to be or where you are now? If you answered yes and yes to both of the questions, you are on the right track and have some idea on what a reflection essay would look like. This article would help give you more ideas on how to write a self reflection essay , how it looks like, what to put in it and some examples for you to use. So what are you waiting for? Check these out now.

10+ Self Reflection Essay Examples

1. self reflection essay template.

Size: 27 KB

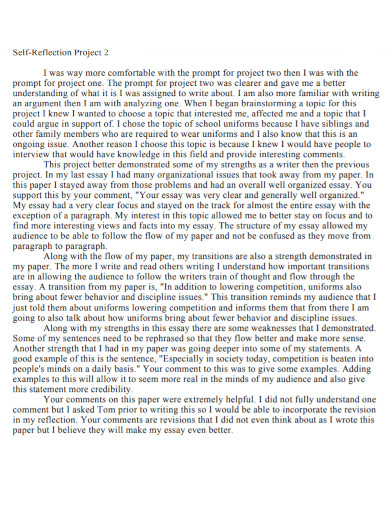

2. Project Self Reflection Essay

Size: 35 KB

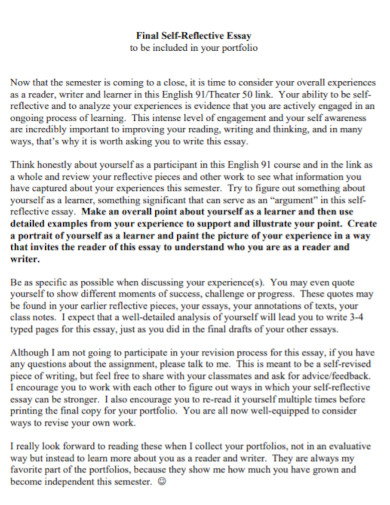

3. Final Self Reflection Essay

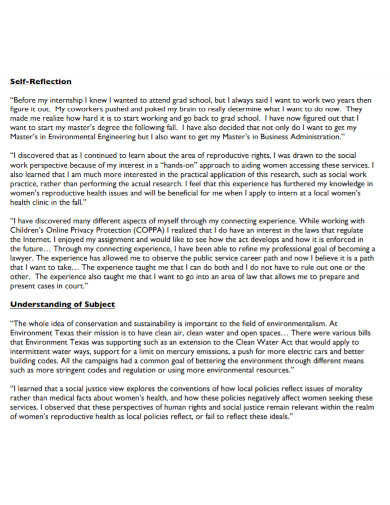

4. Internship Self Reflection Essay

Size: 36 KB

5. Student Self Reflection Essay

Size: 267 KB

6. Basic Self Reflection Essay

Size: 123 KB

7. College Self Reflection Essay

Size: 256 KB

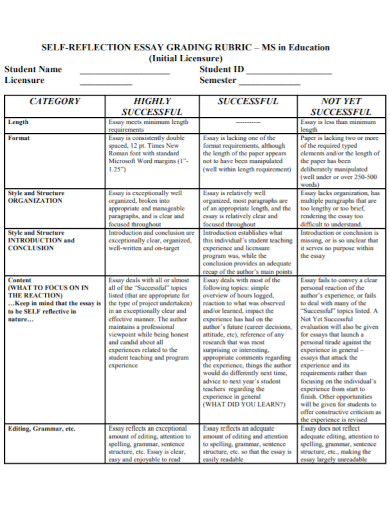

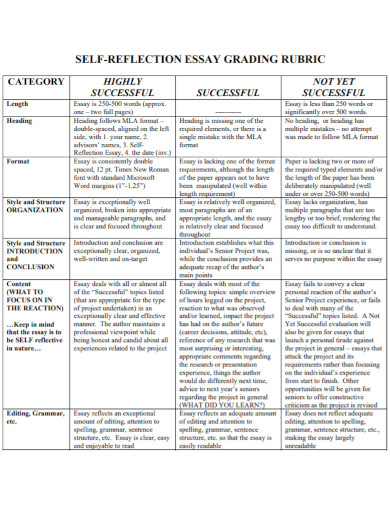

8. Self Reflection Essay Rubric

Size: 16 KB

9. Standard Self Reflection Essay

Size: 30 KB

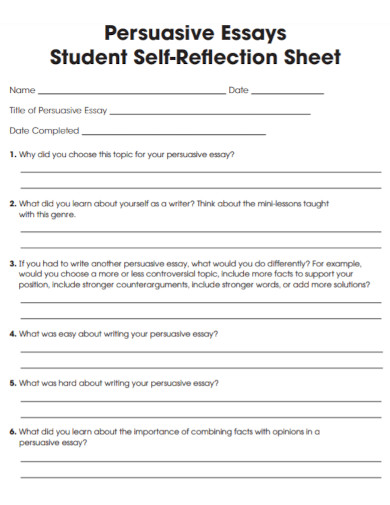

10. Persuasive Essays Student Self-Reflection

Size: 24 KB

11. Self Reflection Essay in Higher Education

Size: 139 KB

Defining Self

A person’s self that is different from the rest. On occasions it is considered as an object of a person’s view.

Defining Self Reflection

A self reflection is often described as taking a step back to reflect on your life. To take a break and observe how far you have become, the obstacles you have gone through and how they have affected your life, behavior and belief.

Defining Self Reflection Essay

A self- reflection essay is a type of essay that makes you express the experiences you have gone through in life based on a topic you have chosen to write about. It is a personal type of essay that you write about. It makes you reflect on your life and journey to who you are today. The struggles, the fears, the triumphs and the actions you have taken to arrive at your current situation.

Tips on Writing a Self Reflection Essay

When writing a self reflection essay, there are some guidelines and formats to follow. But I am here to give you some tips to write a very good self reflection essay. These tips are easy to follow and they are not as complicated as some might believe them to be. Let’s begin. To write a good self reflection essay, one must first do:

- Think : Think about what you want to write. This is true for the title of your essay as well. Thinking about what to write first can save you a lot of time. After this tip, we move on to the next one which is:

- Drafting : As much as it sounds like a waste of time and effort, drafting what you are preparing to write is helpful. Just like in the first tip, drafting is a good way of writing down what you want and to add or take out what you will be writing later.

- State the purpose : Why are you writing this essay? State the purpose of the essay . As this is a self reflective essay, your purpose is to reflect on your life, the actions you did to reach this point of your life. The things you did to achieve it as well.

- Know your audience : Your self reflection essay may also depend on your audience. If you are planning on reading out loud your essay, your essay should fit your audience. If your audience is your team members, use the correct wording.

- Share your tips: This essay gives you the opportunity to share how you have achieved in life. Write down some tips for those who want to be able to achieve the same opportunity you are in right now.

How long or short can my self reflection essay be?

This depends on you. You may write a short self reflection essay, and you may also write a long one. The important thing there is stating the purpose of you writing your essay.

Writing a self reflection essay, am I allowed to write everything about my life?

The purpose of the self reflection essay is to reflect on a topic you choose and to talk about it.

Is there a limit of words to write this type of essay?

Yes, as much as possible stick to 300-700 words. But even if it may be this short, don’t forget to get creative and true in your essay.

A self reflective essay is a type of essay that people write to reflect on their lives. To reflect on a certain topic of their life and talk about it. Most of the time, this type of essay is short because this is merely to take a step back and watch your life throughout the beginning till the present time. Writing this type of essay may be a bit difficult for some as you have to dive deep into your life and remember the triumphs and the loss. The beauty of this essay though is the fact that you are able to see how far you have reached, how far you have overcome.

Self Reflection Essay Generator

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

Write a Self Reflection Essay on a time you overcame a personal obstacle.

Reflect on your personal growth over the last year in your Self Reflection Essay.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

The Importance of Self-Reflection: How Looking Inward Can Improve Your Mental Health

Sanjana is a health writer and editor. Her work spans various health-related topics, including mental health, fitness, nutrition, and wellness.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/SanjanaGupta-d217a6bfa3094955b3361e021f77fcca.jpg)

Dr. Sabrina Romanoff, PsyD, is a licensed clinical psychologist and a professor at Yeshiva University’s clinical psychology doctoral program.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/SabrinaRomanoffPhoto2-7320d6c6ffcc48ba87e1bad8cae3f79b.jpg)

Sunwoo Jung / Getty Images

Why Is Self-Reflection So Important?

When self-reflection becomes unhealthy, how to practice self-reflection, what to do if self-reflection makes you uncomfortable, incorporating self-reflection into your routine.

How well do you know yourself? Do you think about why you do the things you do? Self-reflection is a skill that can help you understand yourself better.

Self-reflection involves being present with yourself and intentionally focusing your attention inward to examine your thoughts, feelings, actions, and motivations, says Angeleena Francis , LMHC, executive director for AMFM Healthcare.

Active self-reflection can help grow your understanding of who you are , what values you believe in, and why you think and act the way you do, says Kristin Wilson , MA, LPC, CCTP, RYT, chief experience officer for Newport Healthcare.

This article explores the benefits and importance of self-reflection, as well as some strategies to help you practice it and incorporate it into your daily life. We also discuss when self-reflection can become unhealthy and suggest some coping strategies.

Self-reflection is important because it helps you form a self-concept and contributes toward self-development.

Builds Your Self-Concept

Self-reflection is critical because it contributes to your self-concept, which is an important part of your identity.

Your self-concept includes your thoughts about your traits, abilities, beliefs, values, roles, and relationships. It plays an influential role in your mood, judgment, and behavioral patterns.

Reflecting inward allows you to know yourself and continue to get to know yourself as you change and develop as a person, says Francis. It helps you understand and strengthen your self-concept as you evolve with time.

Enables Self-Development

Self-reflection also plays a key role in self-development. “It is a required skill for personal growth ,” says Wilson.

Being able to evaluate your strengths and weaknesses, or what you did right or wrong, can help you identify areas for growth and improvement, so you can work on them.

For instance, say you gave a presentation at school or work that didn’t go well, despite putting in a lot of work on the project. Spending a little time on self-reflection can help you understand that even though you spent a lot of time working on the project and creating the presentation materials, you didn’t practice giving the presentation. Realizing the problem can help you correct it. So, the next time you have to give a presentation, you can practice it on your colleagues or loved ones first.

Or, say you’ve just broken up with your partner. While it’s easy to blame them for everything that went wrong, self-reflection can help you understand what behaviors of yours contributed to the split. Being mindful of these behaviors can be helpful in other relationships.

Without self-reflection, you would continue to do what you’ve always done and as a result, you may continue to face the same problems you’ve always faced.

Benefits of Self-Reflection

These are some of the benefits of self-reflection, according to the experts:

- Increased self-awareness: Spending time in self-reflection can help build greater self-awareness , says Wilson. Self-awareness is a key component of emotional intelligence. It helps you recognize and understand your own emotions, as well as the impact of your emotions on your thoughts and behaviors.

- Greater sense of control: Self-reflection involves practicing mindfulness and being present with yourself at the moment. This can help you feel more grounded and in control of yourself, says Francis.

- Improved communication skills: Self-reflection can help you improve your communication skills, which can benefit your relationships. Understanding what you’re feeling can help you express yourself clearly, honestly, and empathetically.

- Deeper alignment with core values: Self-reflection can help you understand what you believe in and why. This can help ensure that your words and actions are more aligned with your core values, Wilson explains. It can also help reduce cognitive dissonance , which is the discomfort you may experience when your behavior doesn’t align with your values, says Francis.

- Better decision-making skills: Self-reflection can help you make better decisions for yourself, says Wilson. Understanding yourself better can help you evaluate all your options and how they will impact you with more clarity. This can help you make sound decisions that you’re more comfortable with, says Francis.

- Greater accountability: Self-reflection can help you hold yourself accountable to yourself, says Francis. It can help you evaluate your actions and recognize personal responsibility. It can also help you hold yourself accountable for the goals you’re working toward.

Self-reflection is a healthy practice that is important for mental well-being. However, it can become harmful if it turns into rumination, self-criticism, self-judgment, negative self-talk , and comparison to others, says Wilson.

Here’s what that could look like:

- Rumination: Experiencing excessive and repetitive stressful or negative thoughts. Rumination is often obsessive and interferes with other types of mental activity.

- Self-judgment: Constantly judging yourself and often finding yourself lacking.

- Negative self-talk: Allowing the voice inside your head to discourage you from doing things you want to do. Negative self-talk is often self-defeating.

- Self-criticism: Constantly criticizing your actions and decisions.

- Comparison: Endlessly comparing yourself to others and feeling inferior.

Kristin Wilson, LPC, CCTP

Looking inward may activate your inner critic, but true self-reflection comes from a place of neutrality and non-judgment.

When anxious thoughts and feelings come up in self-reflection, Wilson says it’s important to practice self-compassion and redirect your focus to actionable insights that can propel your life forward. “We all have faults and room for improvement. Reflect on the behaviors or actions you want to change and take steps to do so.”

It can help to think of what you would say to a friend in a similar situation. For instance, if your friend said they were worried about the status of their job after they gave a presentation that didn’t go well, you would probably be kind to them, tell them not to worry, and to focus on improving their presentation skills in the future. Apply the same compassion to yourself and focus on what you can control.

If you are unable to calm your mind of racing or negative thoughts, Francis recommends seeking support from a trusted person in your life or a mental health professional. “Patterns of negative self-talk, self-doubt , or criticism should be addressed through professional support, as negative cognitions of oneself can lead to symptoms of depression if not resolved.”

Wilson suggests some strategies that can help you practice self-reflection:

- Ask yourself open-ended questions: Start off by asking yourself open-ended questions that will prompt self-reflection, such as: “Am I doing what makes me happy?” “Are there things I’d like to improve about myself?” or “What could I have done differently today?” “Am I taking anything or anyone for granted?” Notice what thoughts and feelings arise within you for each question and then begin to think about why. Be curious about yourself and be open to whatever comes up.

- Keep a journal: Journaling your thoughts and responses to these questions is an excellent vehicle for self-expression. It can be helpful to look back at your responses, read how you handled things in the past, assess the outcome, and look for where you might make changes in the future.

- Try meditation: Meditation can also be a powerful tool for self-reflection and personal growth. Even if it’s only for five minutes, practice sitting in silence and paying attention to what comes up for you. Notice which thoughts are fleeting and which come up more often.

- Process major events and emotions: When something happens in your life that makes you feel especially good or bad, take the time to reflect on what occurred, how it made you feel, and either how you can get to that feeling again or what you might do differently the next time. Writing down your thoughts in a journal can help.

- Make a self-reflection board: Create a self-reflection board of positive attributes that you add to regularly. Celebrate your authentic self and the ways you stay true to who you are. Having a visual representation of self-reflection can be motivating.

You may avoid self-reflection if it brings up difficult emotions and makes you feel uncomfortable, says Francis. She recommends preparing yourself to get comfortable with the uncomfortable before you start.

Think of your time in self-reflection as a safe space within yourself. “Avoid judging yourself while you explore your inner thoughts, feelings, and motives of behavior,” says Francis. Simply notice what comes up and accept it. Instead of focusing on fears, worries, or regrets, try to look for areas of growth and improvement.

“Practice neutrality and self-compassion so that self-reflection is a positive experience that you will want to do regularly,” says Wilson.

Francis suggests some strategies that can help you incorporate self-reflection into your daily routine:

- Dedicate time to it: it’s important to dedicate time to self-reflection and build it into your routine. Find a slot that works for your schedule—it could be five minutes each morning while drinking coffee or 30 minutes sitting outside in nature once per week.

- Pick a quiet spot: It can be hard to focus inward if your environment is busy or chaotic. Choose a calm and quiet space that is free of distractions so you can hear your own thoughts.

- Pay attention to your senses: Pay attention to your senses. Sensory input is an important component of self-awareness.

Nowak A, Vallacher RR, Bartkowski W, Olson L. Integration and expression: The complementary functions of self-reflection . J Pers . 2022;10.1111/jopy.12730. doi:10.1111/jopy.12730

American Psychological Association. Self-concept .

Dishon N, Oldmeadow JA, Critchley C, Kaufman J. The effect of trait self-awareness, self-reflection, and perceptions of choice meaningfulness on indicators of social identity within a decision-making context . Front Psychol . 2017;8:2034. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02034

Drigas AS, Papoutsi C. A new layered model on emotional intelligence . Behav Sci (Basel) . 2018;8(5):45. doi:10.3390/bs8050045

American Psychological Association. Rumination .

By Sanjana Gupta Sanjana is a health writer and editor. Her work spans various health-related topics, including mental health, fitness, nutrition, and wellness.

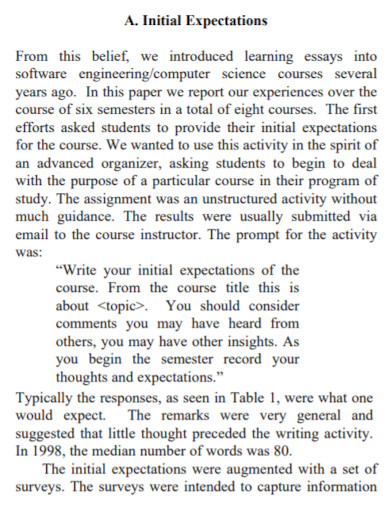

10.5 WRITE: Instructions for the Self-Reflection Essay

Start with the revised paragraphs from the four self-reflection prompts:

- What makes a good academic research essay?

- Why do we learn to write an academic research essay?

- What are your strengths and weaknesses in writing an academic research essay in English?

- How does the use of outside sources of information affect the quality of your academic research essay?

Copy and paste each of your four revised paragraphs into one new document. Organize the four paragraphs in a logical sequence so that each paragraph builds on the previous one. Think carefully about the order of information and how to make connections between the ideas. Add transitions for a smooth flow between sentences and paragraphs. Add an introduction, conclusion, and title. Finally, proofread carefully for grammar and mechanics.

- Use 1-inch margins on all sides

- Use Times Roman 11 or 12 point font or similar

- Use double-spaced lines

- Use page numbers

- Include your full name and date in the upper left-hand of the first page

- Include a title, centered at the top of the page

- Use the TAB key on your keyboard to indent each paragraph

- Use primarily your own words. Outside sources are not required. However, if you use information from an outside source, then you must include in-text citations and a Works Cited page. Follow MLA format.

- For this assignment, you may write in first, second, or third person. You may use an informal tone and informal vocabulary.

- Use six or more paragraphs. The exact number of words, sentences or pages is not important. What is important is that your ideas are clear, compelling, and complete.

- Proofread carefully for grammar, capitalization, punctuation, and spelling.

Each draft is worth 10 points, however each draft is graded differently. The grading rubric for the first draft awards more points for content and organization, while the grading rubric for the second draft awards more points for grammar and mechanics.

- Grading Rubric for Draft Essay – See Appendix B

- Grading Rubric for Revised Essay – See Appendix C

MODEL SELF-REFLECTION ESSAY

ANALYZE THE ASSIGNMENT

- What is the purpose of this essay?

- Who is your primary audience for this essay?

- What type of essay will this be? What will you say or show?

- What voice or point of view should you use in this essay?

- What evidence should you use to support your ideas?

- How long should this essay be?

- When is the draft version of this essay due?

- How will you submit the first draft of your essay?

- When is the revised version of this essay due?

- How will you submit the revised version of your essay?

Synthesis Copyright © 2022 by Timothy Krause is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

11.1: Self-Reflection Essay

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 189672

Coffee, With a Side of Deadline Hectoring

By Ann Tashi Slater

The New Yorker, December 26, 2022

The Restaurant With Many Orders

By Kenji Miyazawa

Translation by Wikisource , April 20, 2021

Introduction

Tokyo's Manuscript Writing Café admits only procrastinating writers facing a deadline. Customers can order coffee with either occasional polite check-ins from the staff or someone to stand over them as they work. Click on the title link to read Ann Tashi Slater's article describing how some customers use the café. Part of the owner's inspiration for the Manuscript Writing Café was a 1924 short story about another eating establishment which provided a different type of orders to its customers. Click on the title link to read the story.

When you've read both articles, consider the questions below.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

- Describe the different meanings of the word "order" in the Manuscript Café. How do these meaning differ from the types of "order" provided in the Wildcat House Restaurant in the story "The Restaurant With Many Orders"?

- Do the customers in each reading react negatively or positively to receiving orders?

- Why do the two gentlemen in the Wildcat House Restaurant respond to increasingly odd orders by repeatedly saying, "Really important people must come here."

- Are you a procrastinator? Would a person monitoring your writing progress and giving orders be a motivator? Why or why not?

- Did you ever use a tutor to cram for a test? If yes, did the tutor or the deadline of meeting with a tutor help you stay on deadline?

- In what ways could you argue that the Manuscript Writing Café would be ineffective, inequitable, or otherwise not useful to students?

- What would improve the Café's ability to help students finish their work?

Ideas for Writing

- What tasks might you typically procrastinate? Do you ever procrastinate writing assignments? What causes you to procrastinate--no time, difficult assignments, or other reasons?

- Imagine what type of Café could help you get started on a task. It could be modeled on the Manuscript Café or it could provide other services to help with problems that prevent you from doing schoolwork, such as tutors or workers to help you with job or family responsibilities, for example.

Works Cited

Slater, Anne Tashi. "Coffee With a Side of Deadline Hectoring." The New Yorker, 26 Dec. 2022, www.newyorker.com/magazine/2023/01/02/coffee-with-a-side-of-deadline-hectoring. Accessed 2 Jan. 2023.

Wikisource contributors. "Translation:The Restaurant With Many Orders." Wikisource , 30 Apr. 2021, The Restaurant With Many Orders - Wikisource, the free online library [en.wikisource.org] . Accessed 2 Jan. 2023.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

MODULE 2 Understanding the Self Unpacking the Self

Related Papers

Arnel Perez

Robee Brooks

masifah hashim

Aemero Asmamaw Chalachew

Series Byzantina

Adriana Adamska

sciepub.com SciEP

Sharby Rementizo

Julieta Newland

Rudy Arzuaga

RELATED PAPERS

Caribbean Journal of Earth Sciences

Serwan Baban

Acta Energetica

Patrycja Jerzyło

Scientific Reports

Journal of Environmental Radioactivity

juan pablo Toso

Food and chemical toxicology : an international journal published for the British Industrial Biological Research Association

Rukset Attar

Hector Ramos

Nieuwe Wiskrant

Mark Timmer

Journal of High Resolution Chromatography

Zilda Morais

Jurnal Basicedu

Ardiana Primasari

JAMA Psychiatry

Maria Petukhova

Nicolas Sarmiento

Lady Fevrian

Mark Anthony

Clinical and Translational Science

BCS Learning & Development

Susan Hazan

IOSR Journal of Engineering

Arun Prakash Agrawal (Professor SET)

JURNAL REKAYASA DAN MANAJEMEN AGROINDUSTRI

Dr. Ir. Amna Hartiati, MP.

RePEc: Research Papers in Economics

Zvika Neeman

Marlies Honingh

eshops12 gr

International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching

Nienke Smit

International Journal of Dynamics and Control

Firoj kabir

Journal of Laryngology and Otology

foster orji

Jornal Brasileiro de Doenças Sexualmente Transmissíveis

Renato Bravo

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

The unpacking of self-acceptance

Do you accept yourself as you are? As working parents and caregivers, many of us are stretched, feeling stressed, and possibly guilty of being too hard on ourselves. Bec Williams of The You Project is here to unpack self-acceptance and remind you that happiness is right in front of you — if you’re paying attention. There’s a lot of unpacking going on lately. Not the kind my Poppa knew — the unpacking of his caravan and preparing the campsite which invariably took a good day by the time he’d set up the awning, toaster, and Nana’s gin cabinet. Rather, ‘unpacking’ in the sense of demystifying a term, breaking down a concept, or explaining an over-inflated thought.

A mentor recently asked me to unpack my concept of self-belief, and I had a go because while I chuckled about all the unpacking — at conferences, at companies — I noticed the term had sneakily weaved its way into my vocabulary. So, today I’m getting on board with the jargon and I’m unpacking self-acceptance.

The self-acceptance formula

Self-acceptance is an acceptance of yourself in entirety (the good, the bad, and the awesome) or, as Nathaniel Branden explains in The Six Pillars of Self Esteem 1 , “My refusal to be in an adversarial relationship with myself”.

Ask yourself

The Latin for ‘accept’ is ‘accipere’, which means ‘to receive, willingly’. Simple question: Do you accept yourself as you are?

Love your unconditioned self

Do you know the difference between your ego and your unconditioned self? Your ego developed during childhood to help cope with being in a family and going to school, and you learned you needed to behave in a certain way to receive approval.

Your unconditioned self is who you are without labels from the outside world. To practice acceptance, you must get to know and love your unconditioned self and not cater to the ego which will constantly be trying to be ‘fixed’.

Stand up to your inner critic

How critical are you? We are usually our own worst critic (often misinterpreted as high standards), translating into, You are not good enough which tells a very bad story for your self-esteem. The amount of judgment we direct towards others is a reflection of how we feel about ourselves.

Practice forgiveness and compassion towards yourself and others. We all make mistakes but we are human, and to live a life where you never accept, learn and move on from these perceived weaknesses will keep you stuck in the past.

Accept your strengths

Do you accept all of your strengths? Most of us struggle to shine at what we’re really great at because we’re afraid of who we might need to be to ‘bare all’. But accepting our talents is an essential step for self-acceptance and will allow you to see limitations as opportunities rather than as obstacles.

Happiness is where you are

“True self-acceptance is the realization that you are what you seek,” Robert Holden.

Make a conscious effort to put it into practice and see the results. Right now, acknowledge three strengths that have contributed to something awesome you have done in the last month. Equally, practice a conscious acceptance of a choice or action you haven’t always loved about yourself but is part of who you are. Note down five ways you are not being very kind to yourself now, and counterbalance that with five ways you can be. Remind yourself: happiness is where I am .

If this all sounds too fluffy for you, that’s okay, but why not spend a day observing your internal dialogue and seeing how kind you are to yourself? If you are, that’s awesome. If not, perhaps it’s something to consider.

Written by Bec Williams, performance coach and owner of @the.you.project .

Source: 1 Branden, N., (1994) The six pillars of self-esteem, New York, Bantam.

Share this post

Other articles you might find interesting.

Rob Sturrock – “I’m a dad that knows the juggle struggle is real”

How are working parents managing the school break juggle?

Why you need to take control of your parental leave journey

I co-founded #PurpleOurWorld in honor of my mother

How motherhood boosted Ghislaine Entwisle’s confidence and ambition

Christmas gift ideas for teachers and early childhood educators

Our product, why circle in.

- Support your people

- Case studies

- Research & guides

- Webinars & events

- Empathy Talks podcast

- Planning for a baby

- Expecting a baby

- On parental leave

- Just back at work

- Working parent

- Real stories

- Our experts

- Press & media

- Work at Circle In

Stay connected

We acknowledge the Traditional Owners of Country throughout Australia and their continuing connection to land, sea and community. We pay our respects to all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, their cultures and to their Elders past, present and emerging.

- Accessibility statement

- Privacy policy

- Terms & conditions

© 2022 Circle In. All rights reserved

Start typing and press enter to search

Here’s your download.

Thank you for being a progressive leader and supporting your working caregivers.

In need of further support? Contact our Circle In Customer Success Team

Unpacking an online peer-mediated and self-reflective revision process in second-language persuasive writing

- Open access

- Published: 13 July 2023

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Albert W. Li ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7472-3517 1 &

- Michael Hebert 1

1768 Accesses

3 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Online peer feedback has become prevalent in university writing classes due to the widespread use of peer learning technology. This paper reports an exploratory study of Chinese-speaking undergraduate students’ experiences of receiving and reflecting on online peer feedback for text revision in an English as a second language (L2) writing classroom at a northeastern-Chinese university. Twelve students were recruited from an in-person writing class taught in English by a Chinese-speaking instructor and asked to write and revise their English persuasive essays. The students sought online peer feedback asynchronously using an instant messaging platform (QQ), completed the revision worksheet that involved coding and reflecting on the peer feedback received, and wrote second drafts. Data included students’ first and second drafts, online peer feedback, analytic writing rubrics, revision worksheets, and semi-structured interviews. The quantitative analysis of students writing performance indicated that peer feedback led to students’ revisions produced meaningful improvements in the scores between drafts. The results of qualitative analyses suggested that: (1) the primary focus of peer feedback was content; (2) students generally followed peer feedback, but ignored disagreements with their peers; (3) students strategically asked for clarification from peers on the QQ platform when feedback was unclear or confusing while collecting information from the internet, e-dictionaries, and Grammarly; and (4) students thought they benefited from experiencing the peer-mediated revision process. Based on the results, we provide recommendations and instructional guidance for university writing instructors for scaffolding L2 students’ text revision practices through receiving and reflecting on online peer feedback.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Impact of Peer Assessment on Academic Performance: A Meta-analysis of Control Group Studies

Kit S. Double, Joshua A. McGrane & Therese N. Hopfenbeck

Impact of ChatGPT on learners in a L2 writing practicum: An exploratory investigation

Not quite eye to A.I.: student and teacher perspectives on the use of generative artificial intelligence in the writing process

Alex Barrett & Austin Pack

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Several studies have documented that students could develop their English writing skills by actively using socio-cognitive learning sources during the writing and revision process (e.g., Duijnhouwer et al., 2010 ; Graham & Alves, 2021 ; Zumbrunn et al., 2016 ). An example of a socio-cognitive learning source is feedback from peer students, which can activate students’ self-reflective thinking for self-assessment while enhancing English writing performance (Graham & Perin, 2007 ; Graham et al., 2015 ; Li, 2023 ; Min & Chiu, 2021 ; Papi et al., 2020 ). Peer feedback is particularly informative in persuasive writing, a genre that requires a fine balance of rhetorical strategy, evidence presentation, and clear language usage to convince the readers of the writer’s opinion (Harris et al., 2019 ; Li, 2022a ). While native English-speaking students are the leading focus group in most studies, few studies have explored text revision processes of English persuasive writing via peer feedback among L2 students, a sizable group still struggling with English persuasive writing and revision practices (Li & Zhang, 2021 ; Zhang et al., 2023 ). Further, given the omnipresence of modern technology in writing teaching and learning, peer feedback is increasingly likely to occur online (Chang, 2015 ; Guardado & Shi, 2007 ; Li, 2022a ). Thus, investigating L2 students’ experiences of receiving and reflecting on online peer feedback, including how it shapes their text revision behavior in English persuasive writing, appears timely.

Enhancing students’ text revision through peer feedback

Studies examining peer feedback in various writing learning contexts, have reported that it contributes to the development of students’ writing learning skills. One notable exploratory intervention study conducted by Lundstrom and Baker ( 2009 ) examined the effectiveness of peer feedback for improving text revision among 91 L2 English students in the United States. Findings revealed that the students’ writing skills before-and-after peer feedback incurred specific gains (i.e., improved writing scores). Similarly, Berggren ( 2015 ), who investigated whether and how Swedish secondary students could improve their revision behavior through peer-to-peer interactions in English writing, found that peer feedback raised students’ audience awareness and motivated them to revise higher-order writing issues (e.g., contents, organization, and logic). Supporting the learning-by-reviewing hypothesis, Cho and MacArthur ( 2010 ) reported that US undergraduates who gave peer feedback could develop their skills of English academic writing and revision across the disciplines more than those who received the feedback. Further, Cho and Cho ( 2011 ) also found that peer reviewers were more able to enhance their L1 academic writing performance when they gave feedback. Specifically, giving microscopic criticism and macroscopic praise significantly benefited them.

Nevertheless, some studies (e.g., Li et al., 2010 ; Nicol, 2010 ) have reported contradictory results that receiving peer feedback could contribute to the reviewer’s revision skills improvement more than providing feedback. Moreover, Trautmann ( 2006 ) examined whether native English-speaking students could improve text revision skills by giving or receiving peer feedback. The finding implied that a critical factor in inducing students to revise was the feedback they received, and 70% of students in their study believed their writing skills are developed because of receiving peers’ suggestions. A more recent study conducted by Min and Chiu ( 2021 ) also found that L2 English students in Taiwan made significantly more macrostructure meaning changes based on the peer feedback they received than on those they gave for the writing draft during the online peer review.

In sum, the inconclusive results on the relative effects of giving versus receiving peer feedback on students’ text revision improvement suggest that more empirical studies should be conducted because peer review is not a simple one-round activity (Papi et al., 2020 ; Yu & Lee, 2016 ). From the peer feedback receiver side, especially for students with high-level self-regulated learning skills, students are more likely to seek further help from their peers by clarifying and negotiating their thoughts, or by accessing other sources in their social learning contexts such as the internet, dictionary, and grammar book for further advice.

Students’ self-reflection on peer feedback for text revision

Although the studies reviewed above have demonstrated that peer review contributes to students’ writing skills development, there has been limited research on how students revise based on self-reflection or peer feedback. As Zimmerman and Kitsantas ( 2002 ) articulated, students could gain revision skills by reflecting and judging peers’ responses to revise their own written text. However, many students do not really draw on self-reflections on their writing and revision learning processes on a timely basis (van Velzen, 2002 ). Additional instructional interventions that motivate students to self-reflect on the peer comments, therefore, may be necessary. Flower ( 1994 ) argued that students must verbalize their own cognitive thinking processes, and that such conscious verbalization is a form of reflective practice and critical thinking. Alitto et al. ( 2016 ) found that when allowing US elementary school students to write their reflective goal and subgoals for revision based on peer-mediated feedback, they outperformed a comparison group on production-dependent writing indices (i.e., the number of words spelled correctly, total number of words written, number of correct word sequences. The decision-making in writing and revision of university-level writing learners has been reported to be based upon the recurrent mental action of their own goals and plan. In an exploratory study of online peer reviews for US undergraduate students in an English for academic (psychology) program, Zhang et al. ( 2017 ) investigated peer feedback as a socio-cognitive source that triggered text revision. Results indicated that students enhanced their writing skills and created significant revisions across high-level (content) and low-level (language) issues. An online retrospective tool called “Lessons Learned” was applied in the study to ask students to draw self-reflections for their future writing and revisions. The researchers suggested that self-reflection should be guided with clear guiding questions about how students can act on their writing on their revision plan before writing the second draft. As integral components in strategy instruction and feedback, self-reflection and revision planning need to be highlighted.

Studies on students’ use of peer feedback in the text revision process have mainly focused on L1 students, with only a few on second-language writing. Among these studies, Duijnhouwer et al. ( 2010 ) found that graduate-level L2 English students in the Netherlands who reflected on their progress via feedback (by completing a reflection journal) could better identify their writing problems and revise them. Similarly, Yang ( 2010 ) observed that Taiwanese university students who reflected on revisions could enhance their L2 English writing during online peer interactions. In other words, by participating in self-evaluation and the self-monitoring of peers’ comments, students could adjust their writing learning strategies and gradually become self-regulating writers.

These findings suggest that students’ reflections can be unveiled by using a revision plan worksheet to document the text revision process when reflecting on peer feedback. Within the worksheet, other qualitative data and analyzing approaches can also be applied, such as drafting self-reflection prompts and developing follow-up interview guidelines to further explore the nature of this peer-mediated revision process.

Online learning environments, peer feedback, and students’ text revision

Incorporating online interactive platforms to facilitate writing instruction and feedback has become popular in recent decades (Li, 2023 ; Li & Zhang, 2021 ; Yu & Hu, 2017 ). With the development of interactive platforms such as WeChat, QQ, and blogs, online peer interaction has emerged as a way to promote the text revision process (Cho & MacArthur, 2010 ; Zhang et al., 2017 ). Studies have highlighted two distinct characteristics of online peer review: time (immediacy), and space (limitless, or beyond geographic borders), both of which have the potential to impact students’ learning outcomes (Li, 2022a ; Xu & Yu, 2018 ; Zhang et al., 2020 ). In this respect, as Lu ( 2016 ) summarized, the benefits of online peer feedback lie in the timeliness of its assessment, negotiation of meaning, and discussion of higher-order writing issues (e.g., contents, organization, and logic), which is quite different from instructors’ written corrective feedback. Furthermore, conducting online peer review provides a comfortable learning environment for students with the possibility to become more self-directed and self-regulated (Zumbrunn et al., 2016 ).

However, research findings on the role and effectiveness of online peer review on the quality of peer feedback and the subsequent text revision made have been mixed. Xu and Yu ( 2018 ) found that online peer review can offer Chinese-speaking students additional learning opportunities to negotiate meaning with their peers motivating them to continue giving feedback on both the structure and content of their L2 English writing. Similarly, Çiftçi and Kocoglu ( 2012 ) reported that L2 English students in Turkey who engaged in blog-based online peer review performed better on their second draft than those who completed traditional face-to-face peer review. However, students have been reported to prefer traditional face-to-face peer feedback when responding to comments on higher-order writing issues (e.g., Chen, 2012 ; Wu et al., 2015 ). Yu and Lee ( 2016 , p. 46) note that a body of studies suggests that online peer review “does not necessarily increase students’ motivation, engagement, and autonomy.” Although online peer review has been observed to increase students’ engagement and enthusiasm for writing and revision, while facilitating the formation and transfer of students’ intrinsic motivation, and developing favorable attitudes toward revision (e.g., Jin & Zhu, 2010 ; Min, 2006 ; Yu & Hu, 2017 ), students’ perceptions toward online peer review are inconsistent (e.g., Guardado & Shi, 2007 ; Ho & Savignon, 2007 ). Guardado and Shi ( 2007 ), for example, in a Canadian university-level L2 English writing class, revealed students’ mixed feelings about conducting online peer review. They reported that many university students considered online peer-to-peer communication more challenging and problematic than face-to-face peer communication because it did not always promote negotiation of meaning among students. As a result, online peer review may be a unidirectional process of communication, with reviewers’ feedback being ignored or misinterpreted. Accordingly, how to enhance two-way peer dialogic communication using online tools appears to be a research area worthy of investigation. Specifically, empirical evidence is needed to demonstrate whether and how online peer review affords space for convenient bidirectional dialogue among peers compared with the unidirectional written form feedback often observed in conventional peer feedback (Nicol, 2010 ).

The present study

Despite the lack of empirical studies on facilitating L2 students’ text revision through online peer feedback while making revision plans through self-reflection, a few studies have explored peer feedback effects and suggested that online feedback may cultivate positive attitudes toward English writing and revision. However, there are some noticeable research gaps and limitations. First, research findings regarding the effectiveness and role of peer feedback for the improvement of text revision have indicated some links between the two. Still, the relevant findings are not consistent, which may be caused by various research designs. Few studies have applied exploratory qualitative instruments to investigate how L2 students learning English might benefit from online peer review and self-reflection on peer feedback. Second, studies investigating the effects of peer feedback on students’ revision behavior are primarily based on comparing researcher-coded peer feedback and revisions. However, it is unclear whether the researcher’s perspective accurately reflects the student’s view. Thus, by developing a coding worksheet for students to self-code peer feedback and match their codes with self-generated decisions for revision, the current study could provide new insights into this peer-mediated and self-reflective revision process from the student’s view. Further, this study expands on findings in the previous literature described by considering the significant underlying differences, perceptions, and experiences of L2 students during text revision processes. Individual L2 student needs to become more self-regulated to strategically use and reflect on peer feedback for text revision in order to develop comprehensive and robust L2 writing skills. The current study is guided by the following three research questions (RQs):

RQ1. What types and numbers of online peer feedback did students receive?

RQ2. How did students use online peer feedback in the text revision process?

RQ3. How did students perceive the benefits from involving in the peer-mediated revision process?

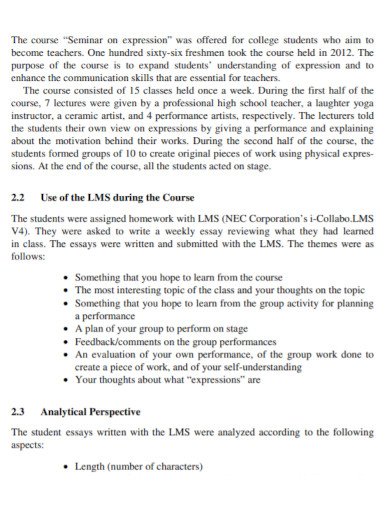

The study was conducted in a first-year in-person course entitled “English Composition I” within an English-medium instruction Footnote 1 program (Bachelor of Arts in English Language Studies) at a research-intensive university in China. The focus of the course was to develop students’ basic English writing skills, such as sentence construction and style in narrative, descriptive, and persuasive essays. The course was taught by a Chinese-speaking instructor with a doctoral degree in English Education who had 20 years of experience teaching academic English writing. The study draws upon numerous sources of empirical data, including student writing and revision drafts, revision worksheets, and semi-structured interviews, to investigate the nature of text revision processes through online peer review.

Participants

Like many English language studies programs in Chinese universities, most of the students (around 18 years old) in the course were female (n = 16, 84%), with only three (16%) males. They were all native speakers of Mandarin Chinese and had learned English for at least 12 years. Their English scores ranged from 120 to 145 (upper-intermediate level across the country) out of a possible score of 150 in the entrance examination to Chinese universities. Their previous writing experience in English was confined to composing notices or short letters of around 150 words. Students used the QQ platform, a popular online interactive platform in China with more than 700 million active users in 2020 (Tencent, 2021 ), to seek and receive comments from peers who also enrolled in the writing class (see Procedures section). Twelve students (9 female and 3 male) who sought online peer feedback on the QQ platform after writing the first draft were recruited to complete the revision worksheet and allow the first author to collect their first and second writing drafts. All 12 students indicated their willingness to participate in a semi-structured interview with the first author to discuss their experiences with the revision process. Seven students who did not participate in the current study (i.e., who did not seek online feedback from peers) still needed to submit their first and second drafts to the writing instructor.

Prior to the formal recruitment, the first author contacted the writing instructor and obtained permission to make an informal visit to the writing class to introduce himself, gave a short presentation about the research purposes and procedures, and observed the writing class. The primary goal of the fourth week’s writing class was to practice an essential genre in English writing: the persuasive essay. Prior to the writing phase, the instructor gave instructions on persuasive writing through close readings and in-class peer-to-peer discussion of how a model essay entitled “A noble career: Attorney” follows genre structure during the first hour of the class. In the second hour of the class, the writing instructor provided three more example essays from the previous writing cohorts asking students to identify writing problems in these essays and then helping them use the scoring rubric (see Measures section) to note specific content (global)- and language (local)-level features of Chinese university-level students’ English writing while trying to assess the three essays. Then, the students were required to spend thirty minutes writing an essay of about 200 words entitled “A career that I wish to pursue” in which they had to give detailed descriptions of an ideal career and explain why the career should be pursued. Students were given the option to type their essays or upload scanned versions of their hand-written essays. To keep the typed and handwritten conditions similar, students who typed the essay were not permitted to access any spell-checking, grammar-checking, or other word-processing resources. At the end of the class, students uploaded their first drafts to the group chat interface on the QQ platform.

After submitting the first drafts, students as authors can decide whether to seek and receive online peer feedback on the QQ platform asynchronously, and students as reviewers could provide oral or typed feedback on the private chat interface. Students self-initiated the feedback-seeking process so they knew the identities of the peers who provided the feedback, and they are able to ask clarifying or follow-up questions about the feedback provided. During the online peer interaction, students also could continue in-depth discussions in different ways, such as by offering further comments, providing additional writing sources, and clarifying and negotiating their English writing problems.

For those twelve students who had sought online peer feedback, they read and signed the consent forms distributed by the first author in-person and completed the revision worksheet (see Measures section), revised their first drafts, and submitted their revised drafts along with their revision worksheet to the first author and uploaded their revised drafts to the group chat interface on the QQ platform before the fifth week’s writing class. This gave the students one week to complete their revisions. Later, these students took about 20–30 min to participate in one-to-one in-person semi-structured interviews with the first author to talk about their experiences of the revision process.

In addition to student writing samples, the study included three instruments used for data collection: (1) a writing rubric, (2) a revision worksheet, and (3) a semi-structured interview. All of the instruments were developed or adapted by the first author and used for the first time in this study.

Writing rubric

The analytic writing rubric (see Appendix 1 for the full rubric) adapted from Li ( 2022b ) was used in two ways in the current study. First, peers who were asked to provide feedback could use the writing rubric taught in the class to evaluate the persuasive essays. Second, it was used by the first author and a research assistant to assess students’ revision quality changes between drafts. The analytic rubric included four components:

Unity (how well students made a specific thesis statement or central argument and kept to it),

Support (how well the students’ writing provided evidence to support the main argument and the evidence is pertinent, typical, and appropriate),

Coherence (how well the students’ writing is structured and linked to the many pieces of evidence), and

Mechanics (how well students used English grammar, particular words, active verbs, and avoided slang, clichés, pompous language, and wordiness).

The rubric included a definition for each writing element, questions evaluators should ask themselves when scoring the element, and a scoring guide with a 1–7 scale (7 is the highest score). The scale included statements for each of the odd scores on the scale (i.e., 1, 3, 5, 7), and indicated that the even scores fell between each of the odd scores. Each dimension accounted for 25% of the overall writing score.

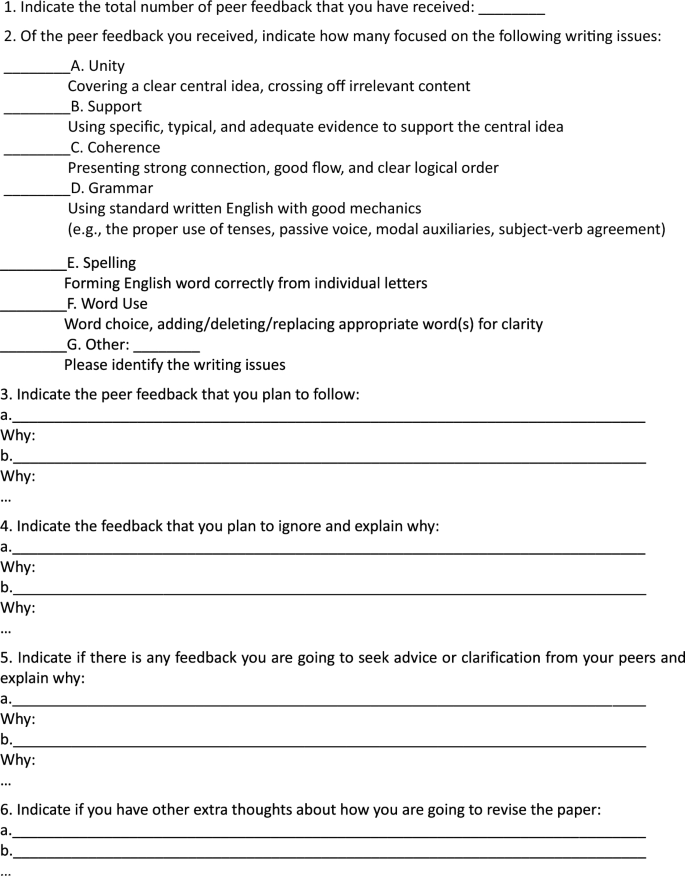

Revision worksheet

During the first draft revision activity, the participants were given a revision worksheet with six questions (see Appendix 2 ) developed by the first author to code the feedback they received from other students according to the coding scheme given on the revision worksheet; they then decided whether to follow or ignore the peer feedback, and finally generated a revision plan by answering the related questions. The revision worksheet guided participants in a structured thinking and reflection process to consider their goals and plan for revision. The worksheets were printed out and distributed to the participants. The participants took about 20–30 min to finish the revision worksheet. Students’ real names were replaced with pseudonyms after they submitted the worksheets.

Semi-structured interviews

The follow-up semi-structured interview questions (see Appendix 3 ) developed by the first author were used to explore students’ text revision process. Each interview, conducted in Mandarin with the first author, took about 20–30 min and was audio-recorded with permission. The participants commented on questions related to (1) their satisfaction with the revisions, (2) their challenges during the revision process, and (3) whether peer feedback, the QQ platform, and the revision plan helped them revise the draft. Participants responded to questions about whether they would continue to seek peer feedback, use the QQ platform, and draft revision plans in future L2 English writing and revision. The audio-recorded data were transcribed and translated into English by the first author after collecting all students’ data. The exact interview time and location were arranged at the student’s convenience. The full transcripts were then sent to the students to check the accuracy and clarity of the transcription. Two students made modifications to the interview content which were incorporated into the final version of the interview data.

Data collection and analysis

The study consisted of three data collection phases. The first phase consisted of draft writing and online peer review. In the second phase, the participants completed the revision worksheet and revision. The third phase was the interviews. Each phase took approximately one week.

To answer our RQs, we analyzed students’ first and revised drafts, writing performance between drafts, peer feedback during the online peer review activities, the revision worksheet, and the post-study interview transcripts. We first obtained students’ writing scores for the two drafts to examine the revision quality. The scores were generated from the mean value of two expert reviewers’ (i.e., the first author and a research assistant) ratings (afterward for the research study) on the writing rubric [rating Kappa (1st draft) = 0.93, Kappa (2nd draft) = 0.89] and we averaged the scores across raters to provide a final score and examine changes in scores from the first to second drafts. Each dimension accounted for 25% of the overall writing score. We then screened the worksheets to identify whether the participants had (1) coded the online peer feedback they received, (2) made decisions about whether to follow or ignore the online peer feedback, and (3) whether they elicited any revision goals and extra thoughts about the worksheet.

Students’ benefits and experiences from conducting online peer review on the QQ platform and using revision worksheets for self-reflections were obtained from the interview with the first author. The first author took the same writing course taught by the same writing instructor seven years ago and has taught college-level L2 writing in China and the USA, the participants seemed comfortable talking with the first author. The first author was an insider who could understand the students’ writing learning experiences but also an outsider with whom they could safely express their benefits and challenges when conducting online peer reviews and reflecting on the peer feedback.

The thematic analysis was applied to the semi-structured interview data by extracting themes (categories of benefits) from the interviews and triangulating views from all participants to clarify meaning and interpretation. The first author first synthesized all interview data to reveal themes related to RQ3. Later, relevant benefits in the interview data were coded for further patterning and clustering. The first author created new themes when the unit did not fit into any of the existing coding categories, and sub-categories were set when groups of data within a category could be classified. The coding process ended when all interview data units were assigned to one of the coding categories. The tentative coding scheme was also provided to a research assistant as a reference to ensure inter-coder reliability. This final revision coding scheme contains two major levels (social and cognitive) and four associated sub-benefits that were generated after analyzing the interview data is presented in Table 1 . It was assessed for inter-rater reliability, producing strong Kappas on all.

Results and discussion

We begin with basic descriptive statistics regarding twelve students’ revision quality, i.e., the score improvements from the first to the second draft. A paired t-test ( t (11) = 6.51, p < 0.000, Cohen’s d = 1.62) of paper ratings from the first to the second draft shows paper ratings improved by a mean of 1.1 points (out of 7), suggesting that the feedback led to students’ revisions produced meaningful improvements in the scores between drafts.

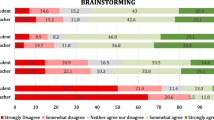

RQ1: What types and numbers of online peer feedback did students receive?

A total of 37 peer reviews were received and coded by the 12 participants into the six major writing issues. Three of these writing issues were higher-order content (global), i.e., unity, support, and coherence. The other three concerned mechanics, including grammar, spelling, and word use. Table 2 illustrates the types and frequencies of peer feedback. Among the six categories, the number of support - related peer feedback that the participants received was 37, which accounts for 100% (37/37) of the total. Coherence-related peer feedback came second (83.8%, 31/37) followed by unity (78.4%, 29/37).

As for low-level writing issues, most peer feedback focused on grammar (73.0%, 27/37) followed by word use (64.9%, 24/37) and spelling (32.4%, 12/37). Thus, peer feedback focused more on higher-order writing issues than lower-order language use. Unlike previous studies (e.g., Leki, 1990 ; Tsui & Ng, 2000 ), where L2 students’ peer feedback heavily focused on surface concerns, such as word use, grammar, spelling, and punctuation, while neglecting macro-level content-related writing issues, the feedback in the present study covered global aspects, such as content, organization, and logic in alignment with Min ( 2006 ) and Yang et al. ( 2006 ). This is likely attributable to the pre-writing training. As revealed by some studies (Min, 2006 ; Min & Chiu, 2021 ), students who are given peer feedback training are inclined to provide and receive more feedback focusing on organization, content, and logic (global areas) rather than grammar, word use, or spelling (local areas). From the first class of the academic English writing course, the instructor started to train students through in-class peer-to-peer discussion to identify both higher- and lower-level writing issues, which could be found in the sample essay shown to the students. Thus, students received peer feedback that covered all six writing issues.

In addition, the affordance of online communication on the QQ platform rather than written marginalia on the hardcopy of their essays might have enabled students to pay more attention to higher-ordered English writing issues (Patchan et al., 2013 ). Specifically, students are likely to receive detailed low prose peer feedback that focuses on grammar, word use, or spelling problems when their peers write marginalia on their essays, or in Lee’s ( 2019 ) words, the written feedback/commentary usually target lower-level writing issues such as grammar correction and “make the paper flooded with the red ink” (p. 524). While in the current study, the QQ platform provided an interactive communication space that enabled students to read and evaluate their peers’ essays online and then type/record peer feedback at the bottom of the individual chat box, which may also encourage students to provide more feedback on the global aspects of writing such as contents, organization, and logic when communicating with peers.

Six of the 12 participants coded nine other types of peer feedback, which accounted for 21.6% (9/37) of the total peer feedback received. Among this feedback, two comments focused on enhancing students’ handwriting, and the other seven were categorized as sentence skills concerning the extensive and effective use of sentences. The writing instructor gave instructions on sentence skills using College writing skills with Readings (Langan, 2011 ) as the required textbook at the beginning of the course so that students would (1) write complete sentences rather than fragments; (2) avoid run-on sentences; and (3) use various sentence patterns. Thus, it was unsurprising to see students receive such peer feedback, although they had learned and practiced these sentence skills since high school.

RQ2: How did students use online peer feedback in the text revision process?

Online peer feedback to follow.

The third question of the revision worksheet generated data revealing that all students decided to take actions based on the support-related peer feedback. When answering the sixth question regarding students’ other thoughts for revision, all students claimed that the support dimension (see Table 3 for examples), i.e., adding supporting evidence to enrich the content, is important.

Deciding to follow peer feedback on specific writing issues does not always mean that students will finally take action to implement those peer feedback into their revisions (Lam, 2021 ; Zhang et al., 2017 ). By comparing their first and second drafts, it was found that all students incorporated support-related peer feedback and made substantial revisions in their second drafts, which aligns with Baikadi et al.’s ( 2015 ) finding that students reflect on content-level peer feedback such as adding more supporting details are more likely lead to text revisions. As Table 4 illustrates, students revised their support problems by adding more details, examples, and evidence to support their central arguments.

All students decided to follow grammar-related peer feedback. Students listed the reasons in the worksheet why these comments were helpful (see Table 5 for examples).

Students believed these grammar-related problems needed to be revised because writers may fail in their primary purpose of writing and lose the readers’ interest (Zelda, Julia). Therefore, such low-level grammatical problems that their peers mentioned were revised (Zoe, Lisa, Mike, Milton). They also believed that paying attention to low-level writing issues could make their second draft error-free (Tina, Helen,) clearer, and more idiomatic (Lisa,) without taking much time (Julia).

Areas where participants revised included: singular and plural, questioning, non-finite verbs, adverbs, and subject-verb agreement (see Table 6 ). In sum, participants decided to follow and incorporate both higher- and lower-order peer feedback into their second draft and revise the writing issues, especially regarding support, coherence, grammar, and spelling. Contrary to the conclusions drawn from other empirical studies (e.g., Cho & MacArthur, 2010 ; Min, 2006 ) which found that students tended to act on micro-level language issues from their peers and make only low-level revisions on their second drafts, this finding indicates that students could identify and balance both higher-order content and low-level language issues upon receiving peer feedback and make decisions based on their self-reflections on peer feedback for further revision planning.

Online peer feedback to ignore

Four students ignored unity-related peer feedback, while two ignored word-use-related peer feedback. Their reasons are presented in Table 7 .

As the above students wrote, they used several negative expressions like “I do not think…”, “I do not agree with peer comment…”, “I disagree with my peers”, “… is not off-topic”, “without irrelevant details”, “I am sorry…”, and “I will ignore this comment” to show disagreement and their decisions to ignore peer feedback. The finding echoes previous studies (e.g., Baikadi et al., 2015 ; Guardado & Shi, 2007 ) that individual L2 students tend to generate decisions/actions to ignore peers’ comments that conflict with their own when revising a second draft.

Online peer feedback requires further advice and clarification

During the interviews, three of the participants said that support-related issues were easy to revise. However, seven students said they were not because some peers’ feedback was too vague. Yara felt lost when reading peer feedback and said:

Some peers mentioned on QQ that I should provide more detailed content to make my essay clearer, but I did not know how to revise the support-related writing problems because they did not provide me with some specific suggestions, and they didn’t specify which paragraph or sentence I should focus on revising. (Yara, Interview Footnote 2 )

Like Yara, some students were struggling with the question of how to revise . For example, Mercer said he wrote a very concise first draft about the career of a network writer. One of his peers suggested that he should add more details to enrich the content and support his central argument . However, he felt confused because he did not know how to enrich the content. Thus, he indicated on the review worksheet that he needed further advice and clarification:

I don’t know how to revise to make my content richer. Their comments are too general. Shall I simply add numbers to provide the salary of the job? Or should some specific examples be given? Adding too many details will make it become wordy and hard to understand, but my essay will become more persuasive to some degree. (Mercer, Revision Worksheet)

Finally, Mercer accepted this suggestion and added details to support his central argument. Furthermore, he mentioned he double-checked with two peers by sending revised drafts to them and continued the conversation after revising the drafts on the QQ platform.

In contrast to Mercer, Julia’s response was quite different when facing the same problem. She wrote on the revision worksheet:

My peers pointed out that the effects and meaning of being a teacher should be provided to support my major argument - Being a teacher is an attractive career for us to pursue, but this peer comment is very general. So, I am not sure how to revise it. (Julia, Revision Worksheet)

Julia also indicated that revising support-related issues was difficult because she thought her peers’ comments were too general and hard to follow. However, she found some model essays and relevant news from the internet as references. In the end, Julia was still dissatisfied with the revised draft, and she found more information online and wrote a third and a fourth draft.

Four students claimed that coherence-related writing issues were difficult to revise, and they sought further suggestions. For example, Yara said:

Coherence-related writing issues in my essay are very difficult to revise because I am not sure how to make my writing more coherent and idiomatic by simply reading my peers’ comments. It is very easy for my peer to say that I have coherence-related problems because our English writing is not perfect. But I just felt very confused because what I really want is more specific suggestions. (Yara, Interview)

When asked to provide more details, Yara explained that one peer suggested that some sentences lacked coherence and needed improvement. Nevertheless, Yara complained that she had no idea which sentences had problems, and thus did not know how to revise them to improve coherence. Therefore, she sought advice and clarification with their peers who provided the original comments on the QQ platform by sending the revised draft to them. In the end, her peers agreed that the revised version was improving, and Yara was delighted to see her writing improve on coherence-related issues with her peers’ help.

Regarding low-level writing issues, three students argued that word use-related peer feedback was difficult to follow. During the interviews with Tina and Julia, they said:

I felt helpless when reading word-use-related peer feedback, and I thought my word usage was good in the first draft. I think they can provide more specific comments to help me revise my essay. I was not sure whether they meant that the use of the word – “Australian” was wrong in my essay. (Tina, interview) My peers’ comments on the word-use writing issues are too general to follow. I understand I had some problems or used some words wrongly in my first draft. But what confused me was that I had no idea which word was used incorrectly. I need more peers to help me find my problems. (Julia, Interview)

Tina decided to double-check with peers on the QQ platform and ask them why they provided these comments. After discussing with peers, she found that the word “Australian” (people) should be “Australia” (country), and she successfully revised the sentence. Unlike Tina, Julia re-read her essay and used the e-dictionary to check the usage of some words like “elect” in the essay and found that it could be replaced by another phrasal verb “search for” to make the essay clearer. Julia’s learning experience with the word use-related writing issue also echoed her decision to use the internet to solve support-related writing issues.

Other—sentence skills

Three students also indicated that they wanted further advice and clarification on some peer feedback regarding sentence skills. For example, Mike received one peer comment which suggested that one sentence should be revised using another expression because it sounded too passive. However, he was not sure which expression was better. Then he discussed with the peer who provided the comment and finally replaced “if I got to” with “when it comes to” in the second draft. Mike commented:

This mutual online learning process is very critical to my learning of English writing, and I benefited a lot. Although some peer feedback I received is quite general, and I was unsure how to revise it, I negotiated this issue with my peers on the QQ platform. And to my big surprise, my peers were very kind, patient, and willing to continue the conversation with me. I feel very grateful to them. (Mike, Interview)

Peer feedback can be either general or contradictory (two peers conflicting) among multiple peer reviewers (Baikadi et al., 2015 ; Patchan et al., 2013 ). One peer suggested that Rose should change one long sentence to two short sentences because the long sentence was difficult to understand; however, another peer praised her because she used some complex sentence structure correctly in her long sentence. Rose felt confused and said:

Interestingly, I received contradictory peer feedback on one writing issue – sentence skills. I found it is really hard to make a decision based on reading my peers’ comments. So, I checked it with the online software called Grammarly on my phone, and it highlighted the sentence as “hard-to-read” because “an expert audience may find this sentence … not clear.” I finally split it into two sentences. (Rose, Interview)

This illustrates how Rose decided with the help of Grammarly to gather helpful feedback on sentence structure for better text revision after reflecting on contradictory peer comments. Echoing previous studies (e.g., Chang, 2015 ; Ho & Savignon, 2007 ; Lam, 2021 ), unlike traditional face-to-face peer review, online technologies play an affordance role in permitting students to gather new information. For example, the QQ platform used in the current study could permit students to continue the private conversation with their peers in either written or oral forms, and the Grammarly software could assess the issues of grammar, word use, and sentence structure of their academic writings, which can increase the quality and volume of feedback that student received. Such timely and thorough revision suggestions are less likely can be provided by individual writing instructors.

The analyses in this section demonstrated that each L2 student might have different action/decision-making paths toward second draft writing triggered by different types of online peer feedback received and revision planning from self-refection. More importantly, students could strategically fix higher- and lower-order writing issues by experiencing one or more rounds of social learning processes mediated by peers in the online technology or other social agents existing in their academic English learning environments.

RQ3. How did students perceive the benefits of the peer-mediated revision process?

Social-level benefits.

The first social-level benefit that all students mentioned during the interview is that peers in the online social environment could provide new insights from various perspectives. For example, Yara said:

My peers have different perspectives and standards when evaluating my writing, so I can understand what different peers think about my writing. I may face a situation where I do not know how to revise, so peer feedback offers me fresh thoughts and solutions from various perspectives. I think this social learning process with my peers is an excellent way to improve my English writing skills. (Yara, Interview)

Students also mentioned that their peers’ perspectives were as important as their instructors’ comments whose time and help are limited (e.g., Tina, Rose). Students like Zoe and Zelda indicated that having peers evaluate their essays was better than self-revision without peer and instructor support.

Furthermore, some students expressed a positive attitude toward conducting peer review because they enjoyed hearing their peers’ “new” (Yara), “different” (Helen), “unique” (Rose), and “interesting” (Zelda, Zara) viewpoints. “The more [peer] feedback, the better , ” said Tina. Zoe used a Confucian proverb “Among any three people walking, I will find something to learn.” to appreciate her peers’ comments. Revising with peer feedback, students found that their second draft was becoming better. Some confirmed that they needed their peers to view their essays from a new perspective (Helen, Zara) and expressed their willingness to find different peers to provide feedback in the future (Lisa, Zoe).

The second social-level benefit that seven students articulated is that using the interactive technology (the QQ platform) could encourage them to initiate several rounds of social self-regulation by discussing, clarifying, and negotiating writing issues with their peers. For example, when reading peer feedback, Mercer commented:

After reading peer feedback, I was unsure how to revise and wanted to explain my thoughts to peers. So I sent some voice messages to my peer, who provided feedback on the QQ platform and we discussed different writing issues again. For me, the peer review never ends because the casual chat with peers on my writing is not confined by time and space. I really like the way we talk about writing learning, and I finally revised my writing problems and really benefited from the online discussion with my supportive classmate. (Mercer, Interview)

Similarly, Lisa felt social interaction with peers on the QQ platform was enjoyable and would continue to practice revisions by continuing the conversation with those peers who provided feedback in the future. Zara, Mike, and Rose also believed that peers on the QQ platform helped them make decisions and generate a more workable plan for the second draft. Mike said:

The QQ platform allows me to continue talking about my writing with peers who provided feedback through private chat. After discussing with my peers, I clarified my thoughts and deepened my understanding of English writing issues. (Mike, Interview)

Cognitive-level benefits

The first cognitive-level benefit that many students referred to is that using the revision worksheet could obtain opportunities to reflect on their peers’ comments and find solutions for revision. For example, Julia explained: