An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

A Novel Treatment of Postpartum Depression and Review of Literature

Jennifer yoon, katherine b martin.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Jennifer Yoon [email protected]

Corresponding author.

Accepted 2022 Feb 18; Collection date 2022 Feb.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Early-onset postpartum depression has been shown to have a unique neurobiological basis compared to major depressive disorder, implying a need for targeted treatments such as the recent Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved brexanolone. In this case report, a woman with a past medical history of major depressive disorder was diagnosed with postpartum depression due to worsening mood with suicidal and homicidal ideations. She was treated with vilazodone and aripiprazole with good effect after consideration of her past medication trials. Her regimen is unique in clinical practice and not reported in current literature for the treatment of postpartum depression. It may represent a safe and effective medication choice, especially in the context of current first-line treatments that have a high treatment failure rate. More research is needed to find treatments that address the unique challenges of postpartum women.

Keywords: post partum depression, post-partum mood disorder, perinatal psychiatry, peripartum depression, perinatal mental health

Introduction

Postpartum depression (PPD) is the most common complication of pregnancy [ 1 ]. Studies have shown that it can have significant long-term effects on both the mother and her newborn [ 2 ]. It is associated with negative maternal caretaking behaviors as well as inferior language skills and IQ development in the child [ 2 ]. While early treatment of PPD is key for reducing these outcomes, there are unique challenges in treating this population. This report will review a recent case of PPD in which a woman presented with suicidal and homicidal ideation one month after delivery. Using the case as a catalyst, this paper will review updated pharmacotherapy treatment options for PPD.

Case presentation

The patient was a 30-year-old female with a history of major depressive disorder (MDD), self-injurious behaviors (cutting as recently as seven years ago), and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). More recently she had been suffering from PPD after the birth of her child one month earlier. She presented to the emergency department with two days of worsening depression along with suicidal and homicidal ideation. Her plan for suicide was to overdose on medications or stab herself with a knife. Her homicidal thoughts were less specific but were directed toward her husband and child. She also endorsed poor sleep, energy, and concentration. She denied any recent substance use and was not breastfeeding. She was overwhelmed by having to care for her newborn, perform household chores, and take care of her twenty pets. Prior to her most recent pregnancy, she was treated with vilazodone 40mg daily and aripiprazole 5mg daily with a good effect on her mood. She had stopped these medications during her pregnancy, but her mood had managed to remain stable until after her delivery.

On account of her symptomatology, she was admitted voluntarily to the inpatient psychiatric unit. She was diagnosed with MDD, recurrent, severe, without psychotic features. She was restarted back on vilazodone 40mg daily and aripiprazole 5mg daily. A family meeting was held to bolster her social support at home. After her third day of admission, her suicidal and homicidal ideation had resolved, and she was able to be discharged home with continued medication management as well as a referral for outpatient therapy.

The postpartum period is a unique time as there are significant fluctuations in a woman’s hormone levels that are associated with the pathophysiology of PPD [ 3 ]. Furthermore, there are critical psychosocial stressors that a new mother faces in adjusting to her new role. For many women, there is a stigma in seeking pharmacological treatment of PPD [ 4 ]. As in this case, the decision of whether to continue psychiatric medication during the pregnancy and postpartum periods can also be a stressor. Furthermore, as also was seen in this case, PPD can present as a clinical emergency as it can lead to suicidal ideation, a suicide attempt, or more rarely, infanticide [ 5 , 6 ]. Therefore, all mental health professionals must be familiar and comfortable with diagnosing and treating PPD.

Current pharmacotherapy treatment options of PPD

Postpartum depression is often clinically treated as a subtype of MDD. Consequently, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the most popular choice of pharmacotherapy [ 7 ]. Furthermore, SSRIs generally have a good safety profile for breastfeeding mothers. Paroxetine and sertraline are least likely to be detected in infant plasma [ 7 ]. Current evidence on the effectiveness of SSRIs for PPD shows that pharmacotherapy alone can be as effective as cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) with pharmacotherapy [ 7 ]. However, these studies have been criticized for lack of long-term follow-up and underpowered sample sizes. Additionally, the use of SSRIs is associated with a remission rate of only up to 60%, which demonstrates the need for more diverse and effective treatments for PPD [ 8 ].

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), labels PPD as “MDD with peripartum onset,” which is defined as the onset of mood symptoms during pregnancy or within four weeks after delivery. However, PPD has also been variably defined as depression that occurs at three months, six months, or 12 months after delivery [ 9 ]. Recent studies have found that the onset of PPD within the first eight weeks of childbirth is distinct from MDD whereas late-onset PPD is more like MDD outside of the postpartum period [ 8 , 10 ]. This finding is due to fluctuating levels of reproductive hormones that occur soon after birth. Therefore, there is likely a unique etiology for PPD as compared to MDD [ 10 ].

Drawing on this unique etiology of PPD, brexanolone, an allopregnanolone analog, became the first drug to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) specifically for PPD in 2019 [ 11 ]. Its use is based on research that found allopregnanolone to be a neuroactive hormone that sharply decreases after birth. This decrease leads to overactivity of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor activation and triggers PPD [ 12 ]. Clinical trials of brexanolone have shown a significant reduction in symptoms of moderate to severe PPD. These results are promising as this group of patients had often been resistant to SSRIs. While it is detected in breastmilk, infant exposure is very low. However, its use is currently restricted to certified healthcare facilities and must be infused over 60 hours. These factors, along with its cost of approximately $39,000 for the drug and its administration, have significantly limited its access [ 13 ].

There are other emerging treatments for PPD that show promise. Transcranial magnetic stimulation has been studied in patients that have PPD with significant effects in both open and double-blinded studies [ 14 ]. Omega-3 fatty acid supplements have been studied for both prevention and treatment of PPD, due to evidence that links PPD with reduced fatty acids [ 8 ].

Use of vilazodone and aripiprazole in PPD

In our case, the patient was treated with a combination of vilazodone and aripiprazole because these are the medications she did well on before pregnancy. This strategy is often employed when choosing a medication for any patient with depression [ 15 ]. With specific regard to PPD, the decision is also based on the balance of the risks and benefits of the proposed treatment [ 16 ]. The patient in this case was not breastfeeding. Therefore, the risks of restarting her medications were quite low and the benefits quite clear. However, it is more often the case that physicians are treating PPD in patients without a psychiatric history, leading to recommendations that may not have clear clinical significance.

Had our patient been pregnant or breastfeeding, it would have been more difficult to counsel her on the potential risks of vilazodone due to a lack of data. There are no human trials on vilazodone in this population, but animal trials have shown adverse effects in the fetus [ 17 ]. A case study of a woman who unexpectedly became pregnant while on vilazodone 40mg daily resulted in a normal birth without complication [ 18 ]. In our case presentation, the patient's extensive psychiatric history and the acuity of her presenting symptoms were factors in restarting her on vilazodone rather than choosing a “safer” choice such as an SSRI. Furthermore, there has been no research comparing the efficacy of vilazodone to SSRIs for PPD. Therefore, the question remains whether vilazodone could be a more effective treatment.

Like vilazodone, little data is also available on aripiprazole in pregnancy or breastfeeding. Until recently, human data for aripiprazole was limited to case reports. More recently, two larger prospective studies were relatively reassuring and did not indicate a higher risk from treatment with aripiprazole as compared to other second-generation antipsychotics during pregnancy, postpartum, and lactation periods [ 19 ]. In breastfeeding, insufficient milk from reduced prolactin release had been a concern, but no adverse reactions have been seen [ 19 ].

Conclusions

Postpartum depression can have long-term negative effects on a mother and her child. Treatment regimens can be challenging due to the changes in mood and the physiology of a woman adjusting to her new role as a mother. There is a change in paradigm in considering PPD as a separate entity from MDD and this change may lead the way to novel pharmacotherapy strategies. Currently, decisions for treatment are made by weighing benefits and risks which can be challenging when there is a lack of reliable data. Continued research is essential to improving treatment strategies for this population.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study

- 1. Depression during pregnancy and postpartum. Toohey J. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;55:788–797. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e318253b2b4. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Postpartum depression: current status and future directions. O'Hara MW, McCabe JE. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9:379–407. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185612. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Pharmacotherapy of postpartum depression: current approaches and novel drug development. Frieder A, Fersh M, Hainline R, Deligiannidis KM. CNS Drugs. 2019;33:265–282. doi: 10.1007/s40263-019-00605-7. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Women's views and experiences of antidepressants as a treatment for postnatal depression: a qualitative study. Turner KM, Sharp D, Folkes L, Chew-Graham C. Fam Pract. 2008;25:450–455. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn056. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Prevalence of suicidality during pregnancy and the postpartum. Lindahl V, Pearson JL, Colpe L. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005;8:77–87. doi: 10.1007/s00737-005-0080-1. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Maternal infanticide associated with mental illness: prevention and the promise of saved lives. Spinelli MG. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1548–1557. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.9.1548. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Treatment of postpartum depression: clinical, psychological and pharmacological options. Fitelson E, Kim S, Baker AS, Leight K. Int J Womens Health. 2010;3:1–14. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S6938. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Pharmacotherapy of postpartum depression: an update. Kim DR, Epperson CN, Weiss AR, Wisner KL. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2014;15:1223–1234. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2014.911842. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Postpartum depression. Stewart DE, Vigod S. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2177–2186. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1607649. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. The peripartum human brain: current understanding and future perspectives. Sacher J, Chechko N, Dannlowski U, Walter M, Derntl B. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2020;59:100859. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2020.100859. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Brexanolone (Zulresso): finally, an FDA-approved treatment for postpartum depression. Powell JG, Garland S, Preston K, Piszczatoski C. Ann Pharmacother. 2020;54:157–163. doi: 10.1177/1060028019873320. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Lower allopregnanolone during pregnancy predicts postpartum depression: an exploratory study. Osborne LM, Gispen F, Sanyal A, Yenokyan G, Meilman S, Payne JL. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017;79:116–121. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.02.012. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Cost-effectiveness of brexanolone versus selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the treatment of postpartum depression in the United States. Eldar-Lissai A, Cohen JT, Meltzer-Brody S, et al. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2020;26:627–638. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2020.19306. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Efficacy of rTMS in decreasing postnatal depression symptoms: a systematic review. Ganho-Ávila A, Poleszczyk A, Mohamed MM, Osório A. Psychiatry Res. 2019;279:315–322. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.05.042. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Antidepressants: Selecting one that's right for you - Mayo Clinic. [ Feb; 2021 ]; https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/depression/in-depth/antidepressants/art-20046273 2019

- 16. Use of prescribed psychotropics during pregnancy: a systematic review of pregnancy, neonatal, and childhood outcomes. Creeley CE, Denton LK. Brain Sci. 2019;9:235. doi: 10.3390/brainsci9090235. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. The preclinical and clinical effects of vilazodone for the treatment of major depressive disorder. Sahli ZT, Banerjee P, Tarazi FI. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2016;11:515–523. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2016.1160051. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Vilazodone for the treatment of major depressive disorder: an evidence-based review of its place in therapy. Hellerstein DJ, Flaxer J. Core Evid. 2015;10:49–62. doi: 10.2147/CE.S54075. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Aripiprazole use during pregnancy, peripartum and lactation. A systematic literature search and review to inform clinical practice. Cuomo A, Goracci A, Fagiolini A. J Affect Disord. 2018;228:229–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.12.021. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (80.8 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Consequences of maternal postpartum depression: A systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes

Justine slomian, germain honvo, patrick emonts, jean-yves reginster, olivier bruyère.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Justine Slomian, Department of Public Health, Epidemiology and Health Economics, University of Liège, CHU—Sart Tilman, Quartier Hôpital, Avenue Hippocrate 13, Bât. B23, 4000 Liège, Belgium. Email: [email protected]

Received 2017 Dec 20; Revised 2019 Jan 30; Accepted 2019 Mar 15; Collection date 2019.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License ( http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ) which permits non-commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access pages ( https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage ).

Introduction:

The postpartum period represents the time of risk for the emergence of maternal postpartum depression. There are no systematic reviews of the overall maternal outcomes of maternal postpartum depression. The aim of this study was to evaluate both the infant and the maternal consequences of untreated maternal postpartum depression.

We searched for studies published between 1 January 2005 and 17 August 2016, using the following databases: MEDLINE via Ovid, PsycINFO, and the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group trials registry.

A total of 122 studies (out of 3712 references retrieved from bibliographic databases) were included in this systematic review. The results of the studies were synthetized into three categories: (a) the maternal consequences of postpartum depression, including physical health, psychological health, relationship, and risky behaviors; (b) the infant consequences of postpartum depression, including anthropometry, physical health, sleep, and motor, cognitive, language, emotional, social, and behavioral development; and (c) mother–child interactions, including bonding, breastfeeding, and the maternal role.

Discussion:

The results suggest that postpartum depression creates an environment that is not conducive to the personal development of mothers or the optimal development of a child. It therefore seems important to detect and treat depression during the postnatal period as early as possible to avoid harmful consequences.

Keywords: infant outcomes, maternal outcomes, maternal postpartum depression, mother–infant interactions, systematic review

Introduction

Pregnancy and childbirth are two major events in a woman’s life. The birth of a baby induces sudden and intense changes in a woman’s roles and responsibilities. Thus, the postpartum period represents the time of risk for the emergence of maternal postpartum depression (PPD). 1 PPD is a serious mental health problem. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.; DSM-IV) defines PPD as a specifier for major depressive disorder (MDD). 2 PPD is also defined symptomatically as exceeding a given threshold on a screening measure, such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). 3 , 4 In general, PPD occurs within 4 to 6 weeks after childbirth, and symptoms similar to MDD that may be present include depressed mood, loss of interest or pleasure in activities, sleep disturbance, appetite disturbance, loss of energy, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, diminished concentration, irritability, anxiety, and thoughts of suicide. 5

The prevalence of PPD varies substantially depending on the definition of the disorder, country, diagnostic tools used, threshold of discrimination chosen for the screening measure, and period over which the prevalence is determined. 3 , 6 For example, Halbreich and Karkun 7 performed a review of the literature and found a PPD prevalence that varied between 0.5% and 60% among countries, as estimated by the self-reported 10-item EPDS questionnaire. The prevalence of PPD varies from 1.9% to 82.1% in developed countries, with the lowest prevalence reported in Germany and the highest prevalence in the United States. 7 , 8 In developing countries, the prevalence varies from 5.2% to 74.0%, with the lowest prevalence reported in Pakistan and the highest prevalence in Turkey. 8 This tremendous variation in the prevalence of PPD could be explained by heterogeneous study designs or the use of different diagnostic tools (e.g. the EPDS, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), or Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)). 9

Untreated PPD seems to have negative consequences for both infants and mothers. Nonsystematic reviews have indicated that the risks to children of untreated depressed mothers (compared to mothers without PPD) include problems such as poor cognitive functioning, behavioral inhibition, emotional maladjustment, violent behavior, externalizing disorders, and psychiatric and medical disorders in adolescence. 5 , 10 – 17 These nonsystematic reviews reported the outcomes of these children from birth to adolescence. Other nonsystematic and systematic reviews have also explored specific maternal risks when mothers’ PPD is untreated, including more weight problems, 18 , 19 alcohol and illicit drug use, 20 social relationship problems, 21 breastfeeding problems, 22 or persistent depression 23 compared with women who have received treatment. Nevertheless, there are no well-established systematic reviews of the overall maternal and/or infant outcomes of maternal PPD. Thus, the aim of this study was to evaluate all the maternal consequences of untreated PPD and its effects on children between 0 and 3 years of age.

To the extent possible, this research adhered to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement. 24

Search strategy

We searched for all studies published between 1 January 2005 and 17 August 2016, using the following databases: MEDLINE via Ovid, PsycINFO, and the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group trials registry. The following keywords were applied in the databases during the literature search: “postpartum depression” OR “postnatal depression” OR “puerperal depression.” The research was limited to human studies published in the English language. The search strategy and search terms used for this research are detailed in Appendix 1 . Additional studies were identified through a manual search of the bibliographic references of the relevant articles and existing reviews.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) cohort and cross-sectional epidemiological and qualitative individual studies; (b) studies that included mothers of all ages who suffered from PPD (all combinations of comparison groups were possible: PPD vs no PPD, severe PPD vs mild PPD, etc.); and (c) studies that included health (physical or psychological) or social outcomes of PPD in the results.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) meta-analyses, systematic and nonsystematic reviews, randomized controlled trials, and case studies; and (b) studies that included mothers who received treatment for PPD. Meta-analyses and systematic and nonsystematic reviews were only accessed to review their bibliographic references.

It is also important to note that there are many factors (e.g. comorbid conditions (anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, or substance abuse), socioeconomic status, education level, co- or single-parenting, and number of previous pregnancies) that could play an important role in the experience of PPD. Nevertheless, in the present systematic review, these factors were not considered as exclusion criteria; instead, they were treated as potential confounding factors. Moreover, because these confounding factors are difficult to account for in a systematic review, the adjusted results were used and discussed in this article when available.

After duplicates were removed, studies identified by the search strategy were exported to an Excel spreadsheet for study selection.

Study selection

In the first step, two investigators performed the study selection and assessed the titles and abstracts of the studies to exclude articles that were immaterial to the systematic review based on the inclusion criteria. In the second step, the same two investigators selected, read and evaluated the full-text studies that met the inclusion criteria. Given the large number of abstracts and full-text articles that needed to be read, the two investigators selected the studies independently.

Data extraction

The studies were divided between the two investigators for data extraction. However, if there was doubt regarding an article, the article was discussed by the two investigators, and a consensus was reached. The two investigators extracted the data from the selected studies according to a standardized data extraction form. The following data were isolated for each study: authors; journal name; year of publication; country of origin; objective of the study; study population data (type of population, mean age, sex ratio of the children, and age, if provided); sample size; design (length of intervention, number of groups, and description of groups); tools used to assess maternal PPD; reported prevalence of maternal PPD; types of infant and/or maternal outcomes and main (adjusted) results; and conclusion. To ensure that as many studies as possible were included in our systematic review, we systematically contacted the authors or co-authors when the full-text paper was not available.

Analysis and synthesis of the results

To facilitate data extraction, the included studies were initially grouped according to three types of outcomes: physical (e.g. weight, length, anthropometric indices, motor development, and physical health); psychological (e.g. mental health, cognitive development, language development, and bonding); or “other” (e.g. social relationships, quality of life, breastfeeding, and risky behaviors). Each outcome group was then thematically analyzed, coded by topic, and divided into more appropriate subgroups. The outcome subgroups were based on information obtained from the studies included in this review. In terms of the studies’ outcomes, key words were labeled and classified into groups with similar consequences. For example, the subcategories “weight,” “length,” and “anthropometric indices” were combined into the more general category of “anthropometry.”

This systematic review of the literature used a narrative synthesis methodology. Each included study was described in a commentary that reported the findings. Similarities and differences among the studies were also synthesized to draw conclusions within the subgroups.

Included studies

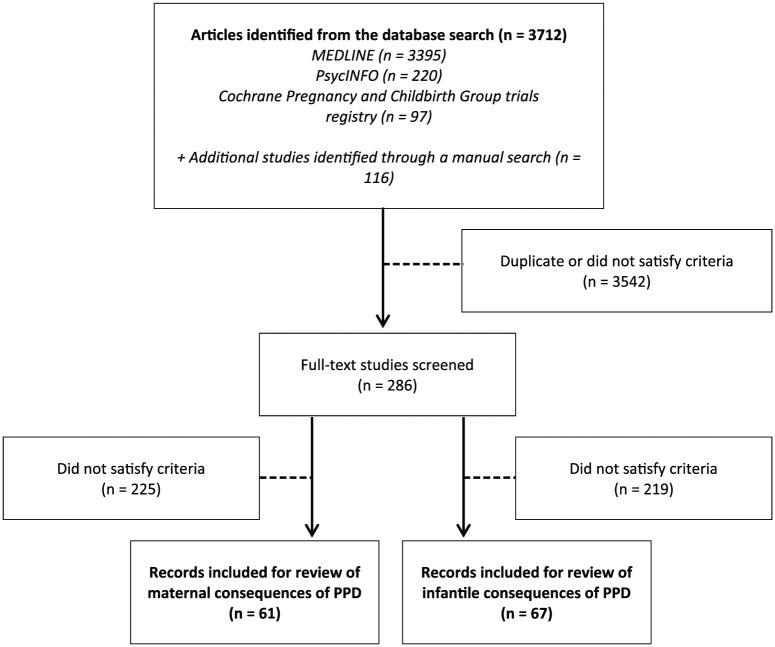

Of the 3712 references retrieved from the bibliographic databases ( Figure 1 ), we identified 122 eligible studies that evaluated the consequences of PPD: 68 that evaluated the maternal consequences and 73 that evaluated the infant consequences. Among the included studies, 19 examined both the infant and the maternal consequences of PPD.

Flowchart of the selection of relevant literature.

The group of studies that evaluated the maternal consequences of PPD included 46 cohort studies 25 – 72 and 21 cross sectional studies 73 – 92 (including 1 qualitative study). 93 The majority of the studies were performed in the United States (28 of 68) and Europe (22 of 68), 10 studies were performed in Asia, and 8 studies were performed in Australia and New Zealand. All studies included women aged between 13 and 45 years. The number of participants ranged from 15 93 to 22,118, 28 and the duration of follow-up varied from 2 weeks 32 to 6 years 33 for the cohort studies.

PPD was mainly diagnosed according to the 10-item EPDS (46 studies); however, there were studies that used the BDI (6 studies), the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview—Short Form (CIDI-SF; 3 studies), the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI; 3 studies), the Postpartum Depression Screening Scale (PDSS; 4 studies), and the CES-D (2 studies). To assess PPD, other studies used other questionnaires (e.g. the Patient Health Questionnaire depression module (PHQ-9 42 or PHQ-8 74 ), the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), 31 or the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) 30 ). The prevalence of PPD varied from 4.5% in a population of Canadian mothers at 6 weeks postpartum 89 to 68.8% in a population of Australian mothers at 4 months postpartum. 64

The group of studies that evaluated the infant consequences of PPD included 61 cohort studies 31 , 34 , 37 , 45 , 48 , 49 , 52 , 53 , 56 , 64 – 66 , 69 – 72 , 94 – 138 and 12 cross-sectional studies. 90 – 92 , 139 – 147 Most of the studies were performed in the United States (27 of 73) and Europe (20 of 73), 12 studies were performed in Asia, 10 studies were performed in Africa, and 4 studies were performed in Australia and New Zealand. All studies included women aged between 14 and 49 years and a percentage of baby girls that varied between 37.7% 49 and 57.5%. 147 The number of participants ranged from 28 123 to 24,263, 98 and the duration of follow-up varied from 2 months 31 , 118 , 123 to 5 years 96 for the cohort studies.

PPD was mainly diagnosed according to the 10-item EPDS (37 studies); however, there were studies that used the CES-D (9 studies), the BDI (7 studies), and the depression section of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; 4 studies). To assess PPD, other studies used various types of questionnaires (e.g. the PHQ-9 135 , 136 or the BSI 100 ). Only one study did not specify the questionnaire that was used to detect PPD. 98 The prevalence of PPD varied from 2.7% in a population of Pakistani mothers at 18 months postpartum 94 to 68.8% in a population of Australian mothers at 4 months postpartum. 64

The outcomes were separated into three sections: “maternal consequences of PPD,” “infant consequences of PPD,” and “mother–child interactions.” The first section, “maternal consequences of PPD,” reported results for 5 different types of outcomes: physical health (3 studies), 35 , 67 , 88 including health care practices and utilization measures (2 studies); 63 , 78 psychological health, including anxiety and depression (6 studies); 36 , 37 , 42 , 44 , 66 , 88 quality of life (8 studies); 27 , 37 , 39 , 48 , 66 , 85 , 86 , 88 relationships, including social relationships and relationships with the partner and sexuality (7 studies); 37 , 38 , 44 , 66 , 73 , 74 , 85 and risky behaviors, including addictive behavior (smoking behavior and alcohol consumption: 4 studies) 55 , 68 , 84 , 87 and suicidal ideation (7 studies). 28 , 30 , 33 , 76 , 81 , 85 , 93 The second section, “infant consequences of PPD,” reported results for 9 different types of outcomes: anthropometry, including weight, length, and anthropometric indices (13 studies); 97 , 100 , 104 , 109 , 110 , 112 , 113 , 119 , 125 , 126 , 131 , 140 , 142 infant health (10 studies); 48 , 104 , 119 , 122 – 124 , 135 , 136 , 138 , 142 infant sleep (3 studies); 104 , 108 , 130 motor development (7 studies); 66 , 94 , 95 , 97 , 103 , 107 , 141 cognitive development (11 studies); 94 , 95 , 99 , 101 – 103 , 107 , 134 , 139 , 141 , 147 language development (13 studies); 66 , 94 , 95 , 102 , 103 , 105 , 116 , 117 , 129 , 131 , 132 , 139 , 141 emotional development (5 studies); 94 – 96 , 115 , 121 social development (4 studies); 66 , 115 , 141 , 143 and behavioral development (12 studies). 49 , 52 , 96 , 110 , 111 , 114 , 115 , 120 , 121 , 131 , 133 , 141 Finally, the third section, “mother–child interactions,” reported results for 3 different types of outcomes: bonding and attachment, including mother-to-infant and infant-to-mother bonding (15 studies); 29 , 31 , 34 , 37 , 43 , 44 , 47 , 52 , 54 , 56 , 61 , 64 , 82 , 106 , 127 breastfeeding (22 studies); 25 , 26 , 32 , 41 , 45 , 59 , 60 , 62 , 65 , 69 – 72 , 77 , 89 – 92 , 118 , 119 , 130 , 137 and maternal role, including maternal behaviors (9 studies), 26 , 40 , 49 , 52 , 53 , 62 , 79 , 83 , 85 maternal competence (2 studies), 51 , 75 maternal care for the infant (6 studies), 37 , 53 , 130 , 137 , 145 , 146 infant health care practices or utilization measures (8 studies), 26 , 37 , 57 , 63 , 98 , 128 , 130 , 142 maternal perception of the infant’s patterns (5 studies), 40 , 46 , 50 , 58 , 80 and the risk of maltreatment (2 studies). 130 , 144

Maternal consequences of PPD

Physical health.

Only three studies evaluated the physical health of depressed mothers ( Table 1 ). One study found that compared to the general population of women, depressed mothers scored significantly lower on the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) physical component summary score (assessed based on physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health, bodily pain, and general health perceptions). 88 However, this study indicated that the severity of the depressed mood was not associated with a worse physical health status, whereas a worse aerobic capacity emerged as a significant independent contributor to physical health status. The two last studies evaluated postpartum weight retention (PPWR) and found that significantly more women with PPWR had higher scores on the PPD scale. 35 , 67

Characteristics of the studies included in the evaluation of maternal physical health.

PPD: postpartum depression; PPWR: postpartum weight retention; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; SD: standard deviation; SF-36: 36-Item Short Form Health Survey; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Health care practices and utilization measures

Two studies 63 , 78 demonstrated an effect of maternal PPD on health care practices and utilization measures ( Table 1 ). One of these studies demonstrated that women with worse depressive symptoms were more likely to consult a general practitioner or mental health professional than women with milder depressive symptoms. 78 The other study showed that women with PPD consulted with family physicians more often than nondepressed mothers did. 63

Psychological health

Six studies ( Table 2 ) evaluated the association between PPD and psychological health; five studies focused on overall psychological health, 37 , 42 , 44 , 66 , 88 two studies focused on anxiety, 36 , 37 and three studies focused on depression. 36 , 37 , 66

Characteristics of the studies included in the evaluation of the maternal psychological health.

GAD: generalized anxiety disorder; MDD: major depressive disorder; PPD: postpartum depression; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.); PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire depression module; QIDS-SR: Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (Self-Report); BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory-II; GLM: general linear models; SD: standard deviation.

Overall psychological health

Several studies showed that depressed mothers presented lower mood scores in the long term (1 year after childbirth) than mothers without depression. One study highlighted that compared to the general population of women, depressed mothers scored significantly lower on the SF-36 mental component summary score (based on vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and mental health). 88 This study also showed that depressed mood was a significant predictor of mental health status in the future (explaining 18% of its variance). 88 Another study showed that women with PPD had lower self-esteem than mothers without depression. 66 Depressed mothers also reported being less happy, more dysphoric, and sadder than mothers without depression. 44 In addition, women with high depression scores had significantly higher levels of anger, lower scores for anger control, and lower levels of positive affect than mothers with low depression scores. 37 Finally, mothers with PPD were generally less responsive to negative stimuli, with lower ratings for intensity and reactions to negative pictorial stimuli, than mothers without PPD. 42

One study showed that depressed mothers had significantly elevated levels of state and trait anxiety at 1 year and 3.5 years after childbirth compared with nondepressed mothers. 37 Another study highlighted that depressed mothers at 3 months postpartum were more likely to exhibit an anxiety disorder than nondepressed mothers at 6 months postpartum, but not after this time point. 36

Compared to nondepressed women, women who were diagnosed with depression in the first weeks after childbirth continued to suffer from depression at 1 year after childbirth. 36 , 37 , 66 However, one study underlined that although mothers continued to suffer from depression, the symptoms appeared to improve, progressing from moderate-to-severe depression at 6 weeks to mild-to-moderate depression at 1 year. 66 Therefore, there appeared to be a slight improvement in the severity of depression over time with or without treatment. 66 Another study used a life history calendar method and found that compared to currently nondepressed mothers, mothers who were depressed at follow-up (3.5 years) did not have more depressive episodes; however, they had longer depressive episodes, received more psychotherapy after hospitalization, and experienced more negative life events during the follow-up period. 37

Quality of life

Eight studies 27 , 37 , 39 , 48 , 66 , 85 , 86 , 88 examined the overall quality of life of depressed mothers compared with nondepressed mothers ( Table 3 ). Three studies 48 , 86 , 88 demonstrated a significantly negative association between maternal depressive symptoms and quality of life. Women with PPD had lower scores on all dimensions of quality of life (e.g. SF-36 or a generic Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) questionnaire) than women without PPD. However, one of the three studies showed that after controlling for mental health-related quality of life earlier in the postpartum period, there was no difference in the subsequent mental health-related quality of life according to the presence of significant depressive symptoms later in the postpartum period. 48

Characteristics of the studies included in the evaluation of the maternal quality of life.

PPD: postpartum depression; CIDI-SF: Composite International Diagnostic Interview—Short Form; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; MINI: Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory-II; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Studies also showed that PPD was associated with greater perceived stress, 66 more negative life events (indicating greater distress and discontinuity), more financial problems, and more illness among close relatives. 37 Depressive symptoms were also associated with fatigue during the first week but not at 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months after childbirth. 39

Regarding the life environment, one study showed that PPD predicted lower levels of household functioning (household care). 85 Another study demonstrated that mothers who experienced depression were twice as likely to become homeless and approximately 1.5 times more likely to be at risk for homelessness than nondepressed mothers. 27

Relationships

Seven studies evaluated social and couple relationships in relation to maternal depressive symptoms ( Table 4 ); four studies were related to social relationships, 37 , 66 , 73 , 85 and four studies were related to relationships with partners and sexuality. 37 , 38 , 44 , 74

Characteristics of the studies included in the evaluation of the maternal social and couple relationship.

FSD: female sexual dysfunction; PPD: postpartum depression; PDSS-SF: Postpartum Depression Screening Scale—Short Form; SRQ-20: Self-Reporting Questionnaire-20; PHQ-8: Patient Health Questionnaire depression module; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; MINI: Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory-II; RR: risk ratio; CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

Social relationships

PPD was associated with more relationship difficulties 37 and therefore with lower social function. 85 Depressed mothers also presented lower (perceived) social support scores than nondepressed mothers. 66 Regarding the probability of returning to paid work, one study showed that there was no difference between depressed and nondepressed mothers. 73 The authors of this study specified that most mothers experienced depressive symptoms during the first year after childbirth; thus, depression was not an independent predictor of how quickly mothers would return to work.

Partner relationships and sexuality

Depressed mothers rated their relationship with their partner as more distant, cold and difficult, and felt less confident than nondepressed mothers over the first year after childbirth. 44 Depressed mothers also reported having more relationship difficulties, including romantic break-ups, than nondepressed mothers; however, this difference was not significant. 37 Regarding sexual life during the first year after childbirth, mothers who had resumed sexual activity had lower depression scores than mothers who did not resume sexual activity during the postpartum period. 38 In addition, depression appeared to cause nearly three times more sexual dysfunction during the first year after childbirth. 74

Risky behaviors

Addictive behavior.

Three studies 55 , 84 , 87 evaluated the influence of PPD on smoking behavior ( Table 5 ). One study showed that smoking and depression often co-occurred among mothers during the postpartum period. 87 The prevalence of PPD was higher among smokers than nonsmokers; conversely, smoking was also more common among mothers with a major depressive episode. The two other studies demonstrated that women who quit smoking during pregnancy might be more likely to relapse if they experience negative emotions or depressive symptoms. 55 , 84 In addition, one study evaluated the influence of PPD on postpartum “risky” drinking at 3 months among women who were frequent drinkers before pregnancy. 68 This study emphasized that there was no significant association between maternal PPD and risky drinking.

Characteristics of the studies included in the evaluation of the maternal risky behavior.

PPD: postpartum depression; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; CIDI-SF: Composite International Diagnostic Interview—Short Form; ICD-9-CM: International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; PDSS: Postpartum Depression Screening Scale; HDRS: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; MINI: Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; MDD: maternal major depressive disorder; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; SD: standard deviation.

Suicidal ideation

Five studies showed that higher levels of depressive symptoms were associated with an increased prevalence of suicidal ideation 30 , 33 , 76 , 81 , 85 ( Table 5 ). Mothers with high suicidality risks experienced greater mood disturbances and more severe postpartum symptomatology than mothers with low suicidality risks. 81 One of the five studies also demonstrated that women who reported higher levels of depression were also significantly more likely to report thoughts of self-harm than women with low levels of depression. 30 The sixth study 28 showed a significant association between PPD and suicidal ideation in an unadjusted analysis, but not in adjusted analysis. An additional study demonstrated that mothers who experienced PPD could imagine acts of infanticide. 93 The authors of this study explained that many mothers preferred to describe their suicidal thoughts rather than their infanticidal thoughts when seeking health care.

Infant consequences of PPD

Anthropometry.

The characteristics and main results of the studies included in the evaluation of anthropometric parameters are presented in Table 6 .

Characteristics of the studies included in the evaluation of infant anthropometric outcomes.

PPD: postpartum depression; CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; SCID-NP: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Non-Patient edition; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; BSI: Brief Symptom Inventory; SRQ-20: Self-Reporting Questionnaire-20; BMI: body mass index; WHZ: weight-for-height z-score; SS: subscapular; TR: triceps; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

A total of 11 studies reported weight as an outcome. Among them, five studies 97 , 104 , 131 , 140 , 142 demonstrated a significant effect of maternal PPD on the child’s weight; infants of depressed mothers gained less weight than infants of nondepressed mothers. Four studies were conducted in low-resource countries (India, 131 Nigeria, 140 Zambia, 142 and Bangladesh 97 ), and one study was conducted in the United States with a very low-income population. 104 Two other studies (one in the United Kingdom 125 and one in Nigeria 119 ) showed that while there were differences in infant weight in the first months of life, they did not persist. Finally, four studies demonstrated that maternal PPD had no effect 100 , 113 , 126 or a very small effect 112 on the child’s weight. Two studies were conducted in high-income countries (a multicountry study that included Belgium, Germany, Italy, Poland, and Spain 113 and one study conducted in the Netherlands 100 ). The third study 126 was conducted in South Africa; however, the authors stated that they were unable to test their hypothesis due to a lack of statistical power.

Eight studies identified in this systematic review reported infant length as an outcome. Three of the studies 110 , 140 , 142 showed a significant effect of maternal PPD on stunting. The three studies were conducted in low-resource countries (Nigeria, 140 Zambia, 142 and South Africa 110 ). One other study 119 showed differences in length in the first months of life; however, it was determined that these differences did not persist over time (Nigeria). Three other studies 97 , 113 , 126 demonstrated that maternal PPD had no effect on stunting. One multicountry study 113 evaluated high-income countries (Belgium, Germany, Italy, Poland, and Spain), and two studies were conducted in low-income countries, including Bangladesh 97 and South Africa. 126 The authors of the South African study stated that they were unable to test their hypothesis due to a lack of statistical power. Another study 109 conducted in a high-income country (the United States) showed the opposite effect: exposure to PPD was associated with a greater height-for-age z-score and a longer leg length.

Anthropometric indices

Four studies evaluated anthropometric indices, and two of them showed no effect of maternal PPD. One study 140 found that maternal PPD was not associated with head circumference (Nigeria). Two studies demonstrated that the triceps and subscapular skinfold thicknesses did not differ between infants of depressed and nondepressed mothers (one study was conducted in Belgium, Germany, Italy, Poland, and Spain; 113 the other was from the United States 112 ). In contrast, one study from the United States 109 showed that PPD was associated with higher subscapular and triceps skinfold thickness scores, which indicated overall adiposity.

Infant health

Of the 10 cohort studies, 9 indicated a significant association between maternal PPD and health concerns in infants ( Table 7 ). Maternal depressive symptoms at 5 months seemed to predict more overall physical health concerns for infants at 9 months 104 and a greater proportion of childhood illnesses. 119 Three studies showed that infants of depressed mothers had significantly more diarrheal episodes per year than those of nondepressed mothers, 119 , 122 , 138 and one study reported that infants of depressed mothers had more days of illness with diarrhea. 138 Harriet et al. specified that these associations with diarrheal episodes were accurate only within the first 3 months. One study also associated maternal depressive symptoms with infant colic. 124 Two studies reported greater overall pain in the infants of depressed mothers 48 and a stronger infant pain response during routine vaccinations. 123 One study demonstrated that maternal PPD at 4 months predicted worse health-related quality of life for the infant in the following months. 48 One study indicated a robust and predictive association between maternal PPD and febrile disease in children. 135 Another study 136 showed that probable postnatal depression was associated with an approximately three-fold increased risk of mortality in infants up to 6 months of age, with an approximately two-fold increased risk of mortality up to 12 months of age. This study also showed that probable postnatal depression was associated with an increased risk of infant morbidity. Only one cross-sectional study reported a nonsignificant association between a high risk of maternal depression and serious illness or diarrheal episodes after adjusting for infant age and other possible confounders. 142 Nevertheless, the occurrence of these two outcomes was proportionally higher among infants of depressed mothers.

Characteristics of the studies included in the evaluation of infant health.

PPD: postpartum depression; CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; SCID-NP: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Non-Patient edition; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire depression module; SRQ-20: Self-Reporting Questionnaire-20; WHO: World Health Organization; SD: standard deviation; CI: confidence interval; SES: socioeconomic status; PND: postnatal depression; RR: risk ratio.

Infant sleep

Three studies evaluated the association between maternal depressive symptoms and infant sleep patterns ( Table 8 ). Two studies showed that higher depressive symptoms were associated with an increased incidence of infant night-time awakenings and predicted more problematic infant sleep patterns. 104 , 108 One of the two studies demonstrated that children whose mothers had severe and/or chronic depressive symptoms had a higher risk of sleep disorders than those with mothers who had mild depressive symptoms. 108 The third study reported that significantly fewer children of mothers with depressive symptoms were placed in the recommended back-to-sleep position compared with children of women who had not experienced depression. 130

Characteristics of the studies included in the evaluation of infant sleep.

PPD: postpartum depression; CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; PHQ: Patient Health Questionnaire; CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio.

Motor development

Three of seven studies showed a significant effect of maternal PPD on the motor development of infants ( Table 9 ). The first study, 97 conducted in Bangladesh, showed that symptoms of maternal PPD that were present at 2–3 months predicted impaired motor development in infants at 6–8 months. The second study 95 included Greek mothers in Crete and demonstrated that symptoms of maternal PPD were associated with lower fine motor scores in infants at 18 months of age (a 5-unit decrease on the scale of fine motor development). The third study 94 showed a nonsignificant impact of maternal depression on the fine and gross motor development of children at 2 and 6 months that became significant at 12 months for gross motor development and at 18 months for fine motor development (Pakistan). The fourth study 141 underlined the indirect effect of maternal PPD on motor development as a consequence of the effects of maternal depressive symptoms on the quality of the home environment. This mechanism had a direct effect on early child development. Three studies 66 , 103 , 107 demonstrated that maternal PPD had no effect on motor development ( Table 9 ). Two studies 66 , 107 explained the nonsignificant results by stating that most of the mothers in the depressed group had moderate-to-severe depression symptoms that were similar to a general description of psychological difficulty during the postnatal period and were less severe than a psychiatric diagnosis of a depressive illness (France and Taiwan). The third study 103 emphasized that the home environment remained a significant predictor of infant development in Australia.

Characteristics of the studies included in the evaluation for motor development in children.

PPD: postpartum depression; AKUADS: Aga Khan University Anxiety and Depression Scale; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory-II; CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; PND: postnatal depression.

Cognitive development

Of the 11 studies, 7 94 , 95 , 99 , 101 , 102 , 107 , 147 indicated a significant and negative association between maternal postpartum depressive symptoms and cognitive development in children ( Table 10 ). One of the studies 147 specifically emphasized the important role of maternal insensitivity in delays in children’s cognitive development. The eighth study 141 underlined the indirect effect of maternal PPD on cognitive development, which occurred as a result of maternal depressive symptoms that impacted the quality of the home environment and had a direct effect on early child development. Three studies 103 , 134 , 139 showed that maternal PPD was not significantly correlated with children’s cognitive development. One of the studies found a nonsignificant effect of maternal PPD and indicated that the home environment was a more important predictor of infant cognitive development in Australia. 103

Characteristics of the studies included in the evaluation of child cognitive development.

PPD: postpartum depression; AKUADS: Aga Khan University Anxiety and Depression Scale; CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory-II; DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.);

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; MSEL: Mullen Scales of Early Learning; PND: postnatal depression.

Language development

A series of different variables may be used to assess language development. Across all studies included in the review ( Table 11 ), language development was evaluated using the following measures: overall language development, 94 , 103 , 105 , 117 expressive and receptive communication, 66 , 95 , 102 , 139 parent-to-child reading, 116 composite speech, 131 and literacy and enrichment literacy activities combined with an understanding of vocabulary and production. 132

Characteristics of the studies included in the evaluation of child language development.

PPD: postpartum depression; AKUADS: Aga Khan University Anxiety and Depression Scale; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory-II; DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.); MINI: Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; CSBS-DP: Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales Developmental Profile.

Of 13 studies, 6 102 , 105 , 116 , 131 , 132 , 139 demonstrated a significant effect of maternal PPD on the language development of infants. Four studies demonstrated an indirect effect on language development; in particular, one study 117 showed that maternal depressive symptomatology in the postnatal year was indirectly associated with worse child language skills at 36 months. Moreover, depression was associated with worse caregiving, and maternal caregiving was positively associated with language. In addition, the effects of depression on caregiving were stronger in less-advantaged socioeconomic groups. Another study 141 underlined the indirect effect of maternal PPD on language development via maternal depressive symptoms that impacted the quality of the home environment and had a direct effect on early child development. The third study, 94 conducted in Pakistan, showed that a child’s language development was affected by maternal PPD only when the father’s income was high. The fourth study 129 reported that maternal PPD was a predictor of less silence and of neutral, positive, and high positive infant vocalizations. This study also found that infants of depressed mothers were more likely to maintain high positive vocalizations than infants of nondepressed mothers, which is a rare vocal quality affective behavior.

The last three studies 66 , 95 , 103 showed that maternal PPD had no effect on the language development of infants. One study 66 justified the nonsignificant results because the majority of the mothers in the depressed group suffered from moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms that were less severe than a psychiatric diagnosis of a depressive illness (Taiwan). The third study 103 highlighted that the home environment remained the significant predictor of infant development in Australia.

Emotional development

Four of five studies 94 , 96 , 115 , 121 demonstrated a significant effect of maternal PPD on the emotional development of infants ( Table 12 ). Infants of depressed mothers also had a significantly higher fear score 115 , 121 and higher degrees of emotional disorders that included anxiety 96 than infants of nondepressed mothers. In addition, one study showed that mothers with a low depression score after birth and a high depression score after several months postpartum had children with significantly higher fear scores than women with decreasing or stable depressive symptomatology. 121 One study indicated a nonsignificant effect of maternal PPD on the social-emotional development of children at 18 months of age. 95 The last study showed that maternal PPD was not associated with separation anxiety. 96

Characteristics of the studies included in the evaluation of child emotional development.

PPD: postpartum depression; AKUADS: Aga Khan University Anxiety and Depression Scale; BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory-II; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Social development

The results of the four studies included in the evaluation of social development are presented in Table 13 . One study indicated that the infants of depressed mothers had lower social engagement scores at 9 months than infants of nondepressed mothers. 115 In this study, the effect of MDD on social engagement was moderated by maternal sensitivity. Another study showed the indirect effect of maternal PPD on social development via the impact of maternal depressive symptoms on the quality of the home environment, which directly affected early child development. 141

Characteristics of the studies included in the evaluation of child social development.

PPD: postpartum depression; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory-II; m-ADBB: Modified Alarm Distress Baby Scale.

One study did not find differences between infants of depressed or nondepressed mothers in the area of social development, 66 and another study showed that maternal PPD did not predict infant social withdrawal (in infants of HIV-infected mothers). 143

Behavioral development

Of 12 studies, 10 demonstrated a significant effect of maternal postpartum depressive symptoms on negative behavior in infants ( Table 14 ). Studies described multiple behavioral traits in children with depressed mothers, including an increase in child behavioral problems at age 2 years, 110 more mood disorders and a more difficult temperament, 114 more internalizing of problems, 111 , 120 lower scores on the Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales Developmental Profile, 131 less mature regulatory behaviors, 115 and higher fear scores that increased behavioral inhibition. 121 One study examined the bidirectional effect of depressed maternal mood on mother–infant engagement using a picture book activity and found that infants of mothers with a depressed mood tended to push away and close books more often. 49 Another study showed a detrimental effect of maternal PPD on dysregulated behavior in infants only when PPD was associated with a comorbid personality disorder. 133 Another study demonstrated that depression explained a significant portion of children’s warmth-seeking behavior toward their mothers (for all mothers) and infant attention and arousal (only for adolescent mothers). 52

Characteristics of the studies included in the evaluation of child behavioral development.

PPD: postpartum depression; K-SADS: Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; SCID: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV; BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory-II; MMD: maternal mood disorder; CBCL: Child Behavior Checklist; PD: personality disorders; MDD: major depressive disorder; MDI: Major Depression Inventory; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; CSBS-DP: Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales Developmental Profile.

One study 141 reported the indirect effect of maternal PPD on self-regulatory behaviors via maternal depressive symptoms, which had an impact on the quality of the home environment and directly affected early child development.

Only one study explored hyperactivity with inattention and physical aggression in the form of opposition; it did not identify an association between maternal PPD and children’s behavioral outcomes. 96

Mother–child interactions

Bonding and attachment, mother-to-infant bonding.

A total of 11 studies 29 , 31 , 34 , 37 , 43 , 44 , 47 , 52 , 56 , 61 , 82 demonstrated a negative effect of maternal depression on mother-to-infant bonding ( Table 15 ). These studies showed that maternal depression might be a risk factor in the development of the mother–infant relationship. For example, O’Higgins et al. 34 demonstrated that women who scored ⩾13 on the EPDS at week 4 were five times more likely to be experiencing poor bonding at the same time as women who scored <13 on the EPDS. Despite these results, Muzik et al. 43 concluded that all women, regardless of whether they are depressed, showed increased bonding with their infant over the first 6 months postpartum. Unfortunately, depressed women showed consistently greater impairment in bonding scores at all time points than nondepressed mothers. However, one study showed that mother–infant bonding appeared to be negatively affected by maternal PPD only in the first months; 61 these studies did not identify an effect of PPD on maternal bonding at 14 months, despite finding negative effects at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, and 4 months postnatally.

Characteristics of the studies included in the evaluation of bonding/attachment between mother and infant.

PPD: postpartum depression; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; CIDI: Composite International Diagnostic Interview; SCL-90-R: Symptom Checklist-90—Revised; PDSS: Postpartum Depression Screening Scale; BSI: Brief Symptom Inventory; SCID: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV; MFAS: Maternal–Fetal Attachment Scale; PRAQ-R: Pregnancy Related Anxiety Questionnaire—Revised; STAI-T: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory—Trait version; PBQ-16: Postpartum Bonding Questionnaire-16; PCERA: Parent–Child Early Relational Assessment; OR: odds ratio; SD: standard deviation; PTSD: posttraumatic stress disorder; MIBQ: Mother–Infant Bonding Questionnaire; MIBS: Mother-to-Infant Bonding Scale.

In addition, women with depressive symptoms showed less closeness, 44 warmth, 44 , 52 and sensitivity 44 , 52 and a significantly lower level of mutual attunement (with regard to emotional availability) 37 and experienced more difficulties in their relationships with their child 44 during the first year than women without depressive symptoms. Lower emotional involvement with the newborn was observed among mothers who suffered from PPD. 82

Finally, mothers who were diagnosed as depressed were more likely to have an insecure state of mind regarding attachment; they had more negative perceptions of their relationship with their infant than nondepressed mothers. 54 , 64 McMahon et al. 64 highlighted that chronically depressed mothers were more likely to be classified as feeling insecure about their attachment, whereas briefly depressed mothers did not differ from mothers who had never been depressed.

Infant-to-mother bonding

Four studies 31 , 34 , 52 , 64 demonstrated a significantly negative effect of maternal PPD on infant–mother bonding ( Table 15 ). One study showed that infants of chronically depressed mothers were more likely to be insecurely attached, while infants of briefly depressed mothers did not differ from infants of mothers who had never been depressed. 64 Another study reported that as maternal depression increased, babies scored less favorably with respect to seeking warmth from their mothers. 52

One study showed that scores on both the maternal positive affective involvement scale and the positive communication scale were lower in mothers with depressive symptoms than in mothers who did not have symptoms of depression. 56 Nevertheless, this study showed that the number of depressive features did not affect infant scale scores (for preterm babies). Another study found that maternal PPD at 2 months was associated with insecure infant attachment at 2 and 18 months. 127 However, this study noted that when concurrent maternal sensitivity was considered, the quality of the early mother–infant relationship remained important, although maternal depression was no longer predictive. Two studies showed that postnatal depressive symptoms were not related to attachment insecurity 106 or disorganization 64 , 106 at 14 months.

Breastfeeding

A total of 22 studies evaluated the association between maternal PPD and breastfeeding, 25 , 26 , 32 , 41 , 45 , 59 , 60 , 62 , 65 , 69 – 72 , 77 , 89 – 92 , 118 , 119 , 130 , 137 ( Table 16 ). Of which, 16 studies found a significant negative effect of maternal depressive symptoms on breastfeeding and/or its parameters. Mothers with depressive symptoms were significantly more likely to discontinue breastfeeding (early interruption of exclusive breastfeeding in the first months), 41 , 59 , 69 , 71 , 90 , 91 , 118 , 119 , 137 engage in less-healthy feeding practices with their infant 25 , 62 , 130 (e.g. significantly more depressed women fed their children prematurely and inappropriately compared with nondepressed women), 130 be unsatisfied with their infant feeding method, 59 experience significant breastfeeding problems, 59 report lower levels of breastfeeding self-efficacy, 59 , 92 and exhibit a lack of breastfeeding confidence 91 and bottle feed 45 , 62 , 65 than mothers without depressive symptoms. Higher depression scores were also associated with early weaning. 89

Characteristics of the studies included in the evaluation of breastfeeding.

PPD: postpartum depression; SCID-NP: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Non-Patient edition; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; POMS: Profile of Mood States; GHQ: General Health Questionnaire; CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; PHQ: Patient Health Questionnaire; PDSS: Postpartum Depression Screening Scale; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; MDD: major depressive disorder; TGF: transforming growth factor; CRF: corticotropin-releasing factor; FT4: plasma free thyroxine; SD: standard deviation; BSES-SF: Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale—Short Form.

Hatton et al. 65 showed conflicting results; they reported a significant inverse relationship between depressive symptoms and breastfeeding at 6 weeks postpartum, but not at 12 weeks.

The four remaining studies did not find a difference between depressed mothers and nondepressed mothers with respect to feeding practices; 26 , 60 , 70 , 72 one study showed that a delayed onset of lactation within the first 48 h, methodological breastfeeding problems, and nipple pain were significantly predictive of breastfeeding cessation. 70

Breast milk concentration and endocrine response to breastfeeding

Three studies evaluated the association between PPD and breast milk concentration and/or the endocrine response to breastfeeding. Maternal depressive symptoms appeared to be correlated with lower oxytocin, 41 total T4 41 concentrations, and higher TGF-β2 concentrations. 77 Kawano and Emori 32 identified weak negative correlations between breast milk secretory immunoglobulin A levels (breast milk SigA level) and all negative profile of mood states (POMS: tension–anxiety, depression–dejection, anger–hostility, fatigue, and confusion); however, there was no correlation between breast milk SigA level and positive POMS state.

Maternal role

Studies that evaluated the association between PPD and the maternal role are presented in Table 17 . Nine studies focused on maternal behaviors and PPD, 26 , 40 , 49 , 52 , 53 , 62 , 79 , 83 , 85 two studies focused on PPD and maternal competence, 51 , 75 six studies focused on PPD and maternal care for infants, 37 , 53 , 130 , 137 , 145 , 146 eight studies focused on PPD and infant health care practices or utilization measures, 26 , 37 ,57,63, 98 , 128 , 130 , 142 five studies focused on maternal perceptions of the infant’s patterns and depression, 40 , 46 , 50 , 58 , 80 and two studies focused on PPD and the risk of maltreatment. 130 , 144

Characteristics of the studies included in the evaluation of the maternal role.

PPD: postpartum depression; MDD: major depressive disorder; GAD: generalized anxiety disorder; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; CES-D: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; MINI: Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; PHQ: Patient Health Questionnaire; SRQ-20: Self-Reporting Questionnaire-20; GAD-Q: Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire; ZSDS: Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale; SOC: sense of coherence; IFSAC: Inventory of Functional Status after Childbirth; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; SD: standard deviation; RR: risk ratio; ED: emergency department; ICQ: Infant Care Questionnaire.

Maternal behaviors

Depressed mothers appeared to be more likely to engage in less-healthy practices with their infant compared to nondepressed mothers ( Table 17 ). They were less likely to place their infant in the back-to-sleep position, 26 , 62 to use a car seat, 26 and to have a working smoke alarm in the home. 26 A higher proportion of the mothers with self-scored depressive symptoms had a poor sense of coherence (comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness) compared with mothers without depressive symptoms. 40 Depressive symptoms were also negatively associated with participation in positive enrichment activities with the child. 52 , 53 , 62 Mothers with PPD were less likely to tell their child stories every day 62 and played games less often 62 than nondepressed mothers. One study found no significant differences in mother–infant engagement with a picture book between depressed and nondepressed mothers. 49 However, this study noted that the infants of these two groups of mothers showed significant differences in their nonverbal behaviors. Depressed mothers also tended to sing faster to their infants than nondepressed mothers. 79 Reissland et al. 83 demonstrated that depressed mothers preferred to cradle their infant to the left, similar to stressed mothers; nondepressed mothers showed right-sided cradling, similar to nonstressed mothers. Nevertheless, the authors added that the left-sided cradling bias might be due to stress rather than depression experienced by mothers. In addition, as depression increased, mothers scored less favorably on positive affect, contingent responsiveness, physical intrusiveness, punitive tone, verbal content, and general verbalness. 52 Low nurturance (defined as behaviors that promotes a child’s psychological growth) and high discipline scores were significantly associated with postnatal depression. 53 Finally, one study showed that functional status, an evaluation of overall functional status, household function, social function, personal function, and infant care activities, was negatively correlated with PPD, with the exception of infant care activities. 85

Maternal competence

Two studies showed that depressed mothers had a lower perception of their competence than nondepressed mothers ( Table 17 ). The first study highlighted that women with lower parenting self-efficacy were more likely to report depressive symptoms than women with higher parenting self-efficacy. 75 The second study concluded that maternal depression was an important factor (32.3% of the total variance) that affected perceived maternal role competence and satisfaction at 6 weeks postpartum. 51

Maternal care for infant

All six studies indicated a significant association between maternal PPD and the care that mothers provided to their child ( Table 17 ). Studies showed that EPDS scores were significantly correlated with increased difficulty with infant care 145 and that significantly more depressed women had poor parenting practices than women who had not experienced PPD. 130 One study highlighted that children of depressed mothers experienced more interruptions and breaks in parental care. 37 Another study indicated that mothers with depressive symptoms showed books, played with or talked to the infant and followed routines significantly less often than nondepressed mothers. 137 A further study demonstrated that low nurturance and high discipline scores were significantly associated with PPD (higher scores were indicative of greater nurturance and a greater use of discipline behaviors). 53 Another study 146 reported that children with a depressed mother had a greater mean number of hours of household television exposure during both weekdays and weekends. Bank et al. 146 also showed that infants of depressed mothers were exposed to significantly more children’s programming than infants of nondepressed mothers.

Infant health care practices and utilization measures

Six out of eight studies demonstrated an effect of maternal PPD on infant health care practices and utilization ( Table 17 ). The first study 128 showed that children whose mothers had depressive symptoms at 2 to 4 months had a reduced probability of receiving age-appropriate vaccinations or age-appropriate well-child visits between 6 and 24 months. This study also showed that these children had an increased likelihood of visiting the emergency department between 1.5 and 2.5 years of age. Mothers who had depressive symptoms also had an increased probability of reporting that their children had sustained injuries. The second study 130 highlighted that depressed women differed significantly from women who had not experienced depression in their use of health services for their child. Depressed women were less likely to complete expected well-health visits for their child. The relative risk (RR) of inadequate well-child visits was two times greater for depressed women than for women who had never experienced depression. Children of depressed women were also less likely to complete immunizations within the expected time frame, and they had significantly more visits to the emergency department for acute care. The third study 98 demonstrated that infants of mothers with PPD were more likely to have ⩾6 sick or emergency visits and had an increased risk of hospitalization compared to infants of mothers without depression. The fourth study 37 reported that most depressed women sought some form of professional help for their child compared to nondepressed women. The fifth study showed that women with PPD consulted more with family physicians and pediatricians than nondepressed mothers did. 63 In addition, the rate of PPD was significantly higher in women who consulted health services for medical reasons (nonroutine care) than for those who visited for routine care only. 57

Another study 26 demonstrated that women with PPD had an increased likelihood of bringing their babies for emergency room visits than women without PPD; however, this association was no longer significant in the adjusted model. Finally, one study 142 did not demonstrate a significant effect of maternal PPD on infant health care practices and utilization measures. This study showed that a high risk of maternal depression did not have a negative impact on the completion of routine immunizations in Zambia. However, clinic location and older infant age were significantly associated with incomplete vaccinations.

Maternal perceptions of infants’ patterns

Postpartum depressive symptoms appear to lead to negative maternal perceptions of infant patterns ( Table 17 ). One study showed that mothers with depressive symptoms had a higher perception of their children’s temperament as “more difficult” than nondepressed mothers. 40 Another study highlighted that mothers with elevated depressive symptoms were more inclined to report infant crying/fussing, sleeping and temperament problems than mothers without PPD. 58 The third study reported that mothers who suffered from PPD were more likely to rate negative infant faces shown for a longer period more negatively than mothers without PPD. 50 The authors of this third study concluded that their results highlighted the difficulties that these mothers have in responding to their own infants’ signals. A fourth study demonstrated that the only difference between mothers with and without PPD was their assessment of babies’ faces; neutral baby faces were judged to be less neutral by depressed mothers than by nondepressed mothers. 80 Mothers with PPD were also less likely to accurately identify happy infant faces (no differences regarding sad faces were identified) than mothers without PPD. 46