Your Article Library

Essay on indian languages.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

India is the home of a very large number of languages. In fact, so many languages and dialects are spoken in India that it is often described as a ‘museum of languages’. The language diversity is by all means baffling. In popular parlance it is often described as ‘linguistic pluralism’. But this may not be a correct description. The prevailing situation in the country is not pluralistic but that of a continuum. One dialect merges into the other almost imperceptibly; one language replaces the other gradually. Moreover, along the line of contact between two languages, there is a zone of transition in which people are bilingual.

Thus languages do not exist in water-tight compartments. While linguistic pluralism is a state of mutual existence of several languages in a contiguous space, it does not preclude the possibility of inter-connections between one language and the other. In fact, these links have grown over millennia of shared history. While linguistic pluralism continues to be a distinctive feature of the modern Indian state, it will be wrong to assume that there has been no interaction between the different groups.

On the contrary, the give-and-take between the languages groups has been very common, often resulting in systematic borrowings from one language to the other. The cases of assimilation of one language into the other are also not uncommon. Let us look at the nature of linguistic diversity observed in India today. According to the Linguistic Survey of India conducted by Sir George Abraham Grierson towards the end of the nineteenth century, there were 179 languages and as many as 544 dialects in the country.

However, this number has to be taken with caution. It may even be misleading in the sense that dialects and languages were enumerated separately, although they were taxonomically part of the same language. Of the 179 languages as many as 116 were speech-forms of the Sino-Tibetan family, spoken by small tribal communities in the remote Himalayan and the northeastern parts of the country.

Even the 1961 census recorded 187 languages. This was despite the fact that the census investigation was far more systematic and the classification was based on modern linguistic criteria. Much of this diversity may be understood properly in the light of some more statistics. For example, 94 out of the 187 languages were spoken by small populations of 10,000 persons or less. In the final analysis, about 97 per cent of the country’s population was found affiliated with just 23 languages.

The diversity of languages and dialects is a reality and it is not the numerical strength of the speakers of a language which is important. The important fact is that there are people who claim a certain language as their mother tongue. Another related development which contributed to linguistic diversity was the development of script. Different Indian languages were written in different scripts. This made learning of different languages a difficult exercise. However, with the growth of scripts, written languages have been successful in maintaining their record with the consequence that literary traditions have evolved.

With the development of a script, oral communication is supplemented by a more powerful form of written communication. In the course of time some of the minor dialect and language groups have lost their identity as they have been assimilated into developed languages. It is a known fact that most of the languages still serve the purpose of oral communication only as speakers of these languages are still illiterate, or preliterate.

It may be assumed that in the beginning various speech communities were confined to their own enclaves, more or less unaware of the existence of other language/dialect groups in the neighbourhood. Sometimes, the boundary between two dialects, or two languages, was knife-edged, as it was described by a hill-line or a river. Within the enclaves, these groups have been communicating through a common language, or dialect, for centuries.

This became the basis of their identity. This traditional association with a language gave them a sense of belonging and thus inculcated in them a feeling of unity with the larger speech community. It may, however, be noted that inter-communication through a language or dialect is always limited in space. Individuals in their daily course of life have a limited reach. In situations where the communication is largely oral the sphere of communication is even smaller. Thus, with the passage of time, each speech community gets differentiated from other communities in the neighbourhood.

This process leads to splitting of the spoken language into diverse dialects. The dialect formation is, however, within the same speech area. With the expansion of the speech territory more dialect groups emerge and the distance between them increases. Sometimes the outlying dialects are so isolated from the parent language that they acquire linguistic nuances of their own sufficient enough to be recognized as an independent branch. A study of historical linguistics reveals that India has gone through all these phases of language development. The present linguistic map of India is naturally a product of these developments.

Language and Dialect:

The faculty of speech is by far the most distinctive human trait. Human beings use a system of language for communication which distinguishes them from the rest of the animal kingdom. It was through language that communication between the different members of a human group started in the early stages of social evolution.

Language thus facilitated multiple forms of human cooperation. Eventually, a division of labour emerged, a prototype of which is unimaginable in the animal world. However, there is no gainsaying the fact that animals also communicate with one another. They also produce vocal sounds although their sounds are simple.

One can differentiate between warning calls, mating calls and those expressing anger or affection. This system of communication is simple as it lacks structure. A structured language was the invention of the human mind, and the most effective tool of communication. In this language words could be replaced easily to change the content of meaning.

In its basic characteristics a human language is essentially a signaling system in which a variety of vocal sounds are employed. These vocal sounds are produced by the peculiar constitution of the human speech organs. There is a combination of the different speech organs— the tongue, glottis, vocal cords and the palate—in producing vocal sounds which are essential elements in human articulation of language.

It appears that in the beginning speakers of a language restricted their communication to relatively small number of vocal sounds out of the many sounds which human beings were capable of making. However, the number of vocal sounds varied from language to language which indicated variations in social evolution and the material conditions of existence. Most languages are satisfied with the use of twenty or thirty such sounds. But there are other languages which have as many as sixty sounds, or even more.

There are others which have less than twenty sounds. These sounds constitute the system of a language. As we know the purpose of a language is communication and a language sooner or later tends to become symbolic, more complex and expressive of abstract ideas. The beginnings of all languages were, however, simple.

There are very specific purposes for which the language is used. The main purpose is, of course, to express oneself, to convey one’s feelings, sometimes to express a desire or pray for help. The human beings also communicate their ideas through body language either alone or in combination with vocal sounds or words.

Even today, the body language continues to be a powerful means of expression. The exchange of ideas, feelings and calls for pray or help continue in the daily course of life of a human being. Thus, an intricate pattern of human cooperation and a feeling of togetherness is evolved. It is obvious that a language needs a group of people among whom communication continues through this language.

This group of people who communicate in a certain language may be described as the ‘speech community’. In the course of time, several speech communities are formed, each occupying a chunk of a geographically contiguous space (Fig. 6.1).

Each language eventually expands over a territory, homogeneous in terms of its language structure—vocal sounds, words, sentences and conventionalized symbols. When a language is written in a script it lends to stabilize its distinguishing features and promotes communication over long distances between people.

Origins of Language:

Origins of language are shrouded in mystery. However, it is possible to reconstruct the bits of this history. It is generally agreed that in the history of social evolution language must have arisen with the discovery of the art of tool-making. Understandably, the early tool-making communities must have depended on cooperation between different members of the group on a highly organized basis.

This would have been possible through the use of a language. Thus evolution of language must have progressed hand in hand with the evolution of material cultures. As the history of material cultures shows the change in techniques of tool-making was initially slow, but later on it picked up. Language also evolved with the same pace. Expressions became more and more complex with the passage of time. In fact, at every stage of evolution, there was a direct relationship between material culture and the language in use.

Evidently progress in material cultures shows that the functions of brain were becoming more and more complex and with these changes language also became complex. The way languages evolved from vocal sounds to words and sentences revealed how they became symbolic as humans tended to express abstract rather than concrete ideas.

It is obvious that in the course of evolution many languages were invented independently at different points of time in different regions of the world. They became further ramified as the social space within which inter-communication continued was always limited (Box 6.1). As a result, new groups were formed and new speech communities came into being.

This is how the ‘families of languages’ developed. It is also understandable that the early languages were oral and writing became possible much later. In the beginning there was no need for maintaining a written record. When such a need arose writing was initially mostly pictorial.

The discovery of the script in the history of development of languages must have taken a painstakingly long time during which picture/signs became conventionalized. Our knowledge of the early scripts is still incomplete. For example, the script of the Indus valley (Harappan) civilization continues to pose difficulties. We have not been able to decipher it simply because we are not familiar with the system of language in which communication was conducted by the Harappan people.

India as a Linguistic Area:

Despite the widely perceived linguistic diversity India’s unity as a socio-linguistic area is quite impressive. Several linguists have analyzed the basic elements of India as a socio-linguistic area. Describing language as an ‘autonomous system’, Lachman M. Khubchandani recognized the major characteristics of the speech forms of modem India. Each region of the country is characterized by the plurality of cultures and languages “with a unique mosaic of verbal experience”. In Khubchandani’s view modem languages of India represent a striking example of the process of diffusion, grammatical as well as phonetic, over many contiguous areas.

However, he considers linguistic plurality only as a superficial trait. “Indian masses through sustained interaction and common legacies have developed a common way to interpret, to share experiences, to think.” What has emerged is a kind of organic plurality, although the geographical distribution of speech communities suggests a kind of linguistic heterogeneity.

Some of the basic elements of India’s linguistic unity may be seen in the fuzzy nature of language boundaries, fluidity in language identity and complementarity of inter-group and intra-group communication. Khubchandani also emphasized the need of linking languages with the ecology of cultural regions described by him as kshetras.

As a language area India is being put to mutually contradictory linguistic interpretations which confuse the issue. Perhaps a better understanding of the linguistic scene can be developed if the static account of the multiplicity of languages is replaced by recognition of the elements of cultural regionalism. Similarly, the issue of linguistic homogeneity which has been argued by several linguists is fraught with complexities. In this context, one can cite the example of the states of the Indian Union carved out on the principle of linguistic homogeneity. The reality is that these states are not necessarily homogeneous in their language composition and cultural attributes.

In an earlier study, Khubchandani examined the evidence on plural languages and plural cultures of India. He dwelt upon the question of language in a plural society. The processes of language modernization and language promotion were also analyzed on the basis of a review of the language policies and planning in India. In this work, Khubchandani noted that people in certain regions of India displayed a certain degree of fluidity in their declaration of mother tongue. On this basis, he recognized two zones in which the country could be divided: a fluid zone and a stable zone. The fluid zone extended over the north-central region where Hindi, Urdu, Punjabi, Kashmiri and Dogri are spoken.

The stable zone, on the other hand, incorporates western, southern and eastern regions. People in these regions did not reveal any fluidity in their mother tongue declaration. Reference may also be made to the seminal work of Murray B. Emeneau who analyzed the characteristics of India as a language area. Tracing the history of development of the Indo-Aryan and the Dravidian languages he evaluated the shared experiences of the different speech communities.

Emeneau defined linguistic area as “an area which includes languages belonging to more than one family but sharing traits in common which are found not to belong to other members of (at least) one of the families”.

Geographic Patterning of Languages:

The geographic patterning of languages in the South Asian sub-continent can perhaps be understood in the context of the space relations the region had with other parts of Asia. As already pointed out, the sub-continent marks a southward projection of the Asian landmass into the Indian Ocean. The overland connections with West and Central Asia, Tibet, China and other regions of Southeast Asia helped the process of infiltration of linguistic influences into the South Asian region.

This is evident from the fact that the languages spoken in the peripheral regions of South Asia, such as Baluchistan, Pak-Afghan borderlands, Kashmir, Gilgit, Hunza, Baltistan and Ladakh as well as the hilly parts of Himachal Pradesh and the regions in the Northeast have strong affinity with the languages spoken in the regions beyond the Hindu-Kush Himalayas. The remote Himalayan areas became the abode of Tibeto-Chinese languages. Similarly, the Northeastern region continued to receive influences from the neighbouring parts of Myanmar, Thailand and Indo-China. These regions are now the domain of the Tibeto-Chinese (Sino-Tibetan) or Tibeto-Burman languages.

The people in the plains of North India from Sind to Assam acquired different branches of the Indo-European family of languages. The peninsular region continued to retain the Dravidian speech-forms even though the north was completely swayed over by the Indo-European languages. Between the Indo-European and the Dravidian one finds the Austric-speaking tribes nestled in the hills of the mid-Indian region.

The linguistic heterogeneity of India can perhaps be brought to some order when one realizes that these speeches really belong to four language families: Sino-Tibetan (Tibeto-Burman), Austro-Asiatic, Dravidian and Indo-European. In the course of usage over millennia of years these language families have found for themselves niches in the Indian social space in different parts of the sub-continent.

Their geographical patterning throws some light on the routes through which these language families reached India. In fact, despite the vast heterogeneity, Indian languages experienced parallel trends in linguistic and literary development during the long phases of shared history. This has made India ‘a composite region’ in terms of linguistic attributes (Table 6.1).

Historical Process of Language Diffusion:

The history of Indian languages is not easy to reconstruct. As an overview of the processes of peopling of India shows, Negroids were the first people to arrive. However, we do not exactly know about their language affiliation. The subsequent waves of migrations were so strong that the Negroids lost their identity completely, leaving behind little traces of either their racial or linguistic past.

The story of the four families of languages may be briefly recapitulated here, although it is not easy to establish the chronological sequence in which the speakers of the Austric, Sino-Tibetan and the Dravidian languages came to India. It is almost certain that these families were already there at the time of the advent of the Indo-Aryan.

This is, however, an established fact that the Sino-Tibetan speech communities were Mongoloids racially. The original Sino-Tibetan, the parent of the early Chinese, is supposed to have developed somewhere in western China around 400 B.C. It is also believed that the diffusion of this language eventually affected the regions lying to the south and the southwest of China-Tibet, Ladakh, northeastern India, Myanmar and Thailand. Perhaps, the Vedic Aryans were familiar with this group. They described the Tibeto-Burman-speaking Mongoloids of the Brahmaputra valley and the adjoining regions as Kiratas.

The speakers of the Kirata family of languages are distributed all along the Himalayan axis from Baltistan and Ladakh to Arunachal Pradesh. They occupy the regions surrounding the Brahmaputra valley in the northeast from Nagaland to Tripura and Meghalaya. There are striking differences between the languages of the Kirata family distributed over such a vast geographical area. The speakers of the Tibeto-Himalayan branch of the Kirata languages occupy the Himalayan regions from Baltistan to Sikkim and beyond to Arunachal Pradesh.

The Bhotia group consists of the Balti, Ladakhi, Lahauli, Sherpa and the Sikkim Bhotia dialects. Linguists also recognize a Himalayan group consisting of Lahuli of Chamba, Kanauri and Lepcha which is distinguishable on the basis of certain linguistic traits. In the east there is a North-Assam branch including the dialects of Arunachal Pradesh, such as Miri and Mishing. In other parts of the northeast the languages belong to the Assam-Burmese branch and are divided into Bodo, Naga, Kachin and Kuki-Chin groups. The speakers of the Kirata languages came to India in different streams at different points of time. Understandably, the groups in the northwest were unrelated to the groups in the northeast.

Similarly, the Kachin and the Kuki-Chin groups followed separate routes of migration. This is why there is a vast variety of dialects within the Kirata family and the roots of linguistic heterogeneity go far beyond the Indian borders into the neighbouring parts of Tibet, Myanmar and Indo-China. Anthropologists as well as linguists believe that the Austric-speaking groups came earlier than the Dravidian-speaking communities. The Austric speech communities were already there in the mid-Indian region before the advent of the Dravidian. The present geography of the Austric dialect groups holds some clues to the historical processes of their diffusion into India.

Generally, the Austric family of languages is recognized as consisting of a Mon-Khmer and a Munda branch. The Mon-Khmer speakers belong to two separate groups, viz., Khasi and the Nicobarese, both separated by a distance of more than 1,500 kilometres which spans over an expanse of the Bay of Bengal. There is no clarity among the scholars about the routes taken by the speakers of the Mon-Khmer dialects. The Khasi speakers themselves are surrounded by other Kirata and Arya dialects in the Meghalayan plateau.

The advent of the Dravidian in India is generally associated with a branch of the Mediterranean racial stock which was already there in India before the rise of the Indus valley civilization. In fact, archaeologists believe that they were the builders of the Harappan civilization along with the Proto-Austroloids. The Dravidian speech communities were found over most of the northern and the northwestern region of India before the advent of the Indo-Aryan. However, following the rise of the Indo-Aryan in northwestern India, a linguistic change came and the Dravidian-speak- ing area shrank in its geographical extent.

The present distributions of the Dravidian dialects in different parts of North India, such as Baluchistan, Chhotanagpur plateau and eastern Madhya Pradesh, where Baruhi, Kurukh-Oraon and the Gondi are spoken respectively, suggest the earlier stage of distribution of this family of languages. In fact, Gondi is spoken in many parts of Central India from Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra to Orissa and Andhra Pradesh.

While Dravidian speech forms were in use for many centuries in the pre- Christian era, the literary development in the Dravidian speech community could take place only in the first few centuries after Christ. It is believed that the old Tamil, old Kannada and the old Telugu had already come into being by 1000 A.D. Malayalam acquired its form a little later. With the Vedic Sanskrit, a branch of the Indo-European, the Indo- Aryan established itself in northwestern India. It had definite relations with the different Indo-European languages, such as Persian, Armenian, Greek, French, Spanish, German and English. An early form of Indo-European seems to have genetic relations with the Hittite speech of Asia Minor.

The linguists have recognized a primitive form of Indo- European in its earlier stage of development. They called it Indo-Hittite. A branch of the Indo-European which had already established itself in Mesopotamia came to be described by the linguists as Indo-Iranian. It is this Indo-Iranian branch which spread over Iran and the northwestern regions of India by the middle of the second millennium B.C. Among the different families of languages spoken in India the Indo-European seems to be the last to arrive. The advent of Indo- European in the South Asian sub-continent brought about a major change in the linguistic affinity of the people of northern India.

The form of Indo-European which was spoken in India came to be known as Indo-Iranian or Indo-Aryan. Its advent in India is seen with the rise of the Vedic Sanskrit. However, the old Sanskrit changed into Prakrit and several speech forms developed in different parts of northern and western India. The region lying between Saraswati and Ganga, encompassing the upper Ganga-Yamuna doab and adjoining parts of Haryana, to the west of the Yamuna, became the stage for the transformation of classical Sanskrit into a Prakrit form. From this early stage of development of Prakrit came the different Indo-Aryan vernaculars which are now spoken in north-western, north-central, central and eastern parts of India.

The Suraseni emerged in the core region of the midland (Madhyadesa of the Purartas) as the popular language. Its core area extended over western Uttar Pradesh and the adjoining parts of Haryana. A developed form of this parent language is described by the linguists as Western Hindi (Fig. 6.2).

Around the core region of Suraseni other speech forms developed on the west, south and east. These languages formed an outer band around the core language. On the west and the northwest lay the Punjabi and the Pahari dialects. Rajasthani and Gujarati emerged on the southwest. On the east, a form of language, now known as Eastern Hindi, emerged in Kosali (Awadhi). Linguists believe that these outer dialects were all more closely related to each other than any one of them was to the language of the midland.

“In fact, at an early period of the linguistic history of India, there must have been two sets of Indo-Aryan dialects—one the language of the midland and the other the group of dialects forming the outer band.” This first stage was followed by a subsequent phase of expansion. As the population of the midland region increased expansion became a necessity. Thus, on the periphery of the languages of the outer band developed new speech forms which were by and large not related to the language of the midland.

For example, while Punjabi was closely related to the language of the upper doab it got transformed into Lahnda in southwestern Punjab. This language had little relationship with the language of the midland. With increasing distance changes became quite pronounced. The geographical distribution of the Indo-Aryan languages may be briefly summarized here as follows: The midland language occupies the Ganga-Yamuna doab and the regions to its north and south. This core region is encircled by different speech forms in eastern Punjab, Rajasthan and Gujarat.

Further beyond in the west and the northwest, there is a band of outer languages—Kashmiri, Sindhi, Lahnda and Kohistani. The languages of this band may be described as constituting the northwestern group of the outer languages. On the southern periphery lies the Marathi. In the intermediate band are situated languages, such as Awadhi, Bagheli and Chhattisgarhi. On the eastern periphery lie the three dialects of Bihari, viz., Bhojpuri, Maithili and Maghadi. The Bihari is surrounded by Oriya in the southeast and Bengali in the east. The languages of the eastern branch of the Indo-Aryan extend further in the east where Assamese occupies the Brahmaputra valley (Fig. 6.3).

Linguists believe that the development of the Indo-Aryan languages completed itself through several phases. The Prakrits developed into two stages: Primary Prakrits and Secondary Prakrits. The Primary Prakrits which were the first to evolve out of the classical Sanskrit were synthetic languages with a complicated grammar.

In the course of time they ‘decayed’ into Secondary Prakrits. “Here we find the languages still synthetic, but diphthongs and harsh combinations are eschewed, till in the latest developments we find a condition of almost absolute fluidity, each language becoming an emasculated collection of vowels hanging for support on an occasional consonant. This weakness brought its own nemesis and from, say 1000 A.D., we find in existence the series of modern Indo-Aryan vernaculars, or, as they may be called Tertiary Prakrits.”

The last stage of development of the Prakrits is known as literary Apabrahmsa. It is supposed that the modern vernaculars are the direct children of these Apabrahmsas. The sequence of change was like this. The Suraseni Apabrahmsa was the parent of Western Hindi and Punjabi. Closely connected with it were Avanti, the parent of Rajasthani, and Gaurjari the parent of Gujarati. The other intermediate language —Kosali (Eastern Hindi)—sprang from Ardha-Magadhi Apabrahmsa. The chronological sequence may be roughly reconstructed here (Table 6.2).

The different stages through which the Indo-Aryan languages passed can be depicted as on Figure 6.4.

In a country where so many languages/dialects are spoken, and many of them are used for oral communication only, linguistic classification may not be an easy exercise. The scientific study of Indian languages, their grammar, phonetics and vocabulary which goes back to the nineteenth century is still ridden with problems.

For one thing, linguists are still unsure of genetic relationships between one language group and the other. Their knowledge of some of the minor languages is pathetically inadequate. This leaves the problem of classification always open to revision. A second set of problems arises from the recognition of the major languages and their specification in the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution.

There were political compulsions under which some languages were given this special status. The Eighth Schedule mentions eighteen languages; twelve of them have their own territory where they receive maximum state patronage and seem to have great potential for development. The Eighth Schedule also includes languages, such as Sanskrit, Sindhi, Nepali and Urdu. The first three do not have a speech territory as such. The speakers of Urdu, Sindhi and Nepali are distributed across several states.

Minor speech communities, such as Manipuri (with a population of 1.27 million) and Konkani (with a population of 1.72 million) have also been given the status of scheduled languages. The anomaly in this approach is that while some of the minority speech groups have found a place in the Eighth Schedule, major Austric languages, such as Santali (speakers 5.22 million), Bhili (speakers 5.57 million) or Gondi (speakers 2.12 million), have been completely ignored.

The official language policy leaves the issue amenable to political manipulation. Like the Austric languages all small Tibeto-Burman languages have also been excluded from the Eighth Schedule. Hindi, which has the largest number of speakers, is an aggregate of at least fifty different dialect groups. There are at least seven states which recognize Hindi as their official language. Of the four language families (Tibeto-Burman, Austro-Asiatic, Dravidian and the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European) the most diverse is the Tibeto-Burman as their speakers communicate in 70-80 different languages. Next is the Indo-Aryan with 19 languages grouped under it.

The Dravidian family incorporates 17 different speech communities; while the Austro-Asiatic has 14 languages. However, this analysis is incomplete because of the fact that the 1991 census used an eligibility condition for recognizing a language as a mother tongue if it had more than 10,000 speakers at the all-India level.

This resulted in the exclusion of 0.56 million speakers of different minor languages from finding a reference in the census records. There is, therefore, no recognition of these small speech communities. Due to operational difficulties, the 1991 census could not be conducted in the state of Jammu and Kashmir. This resulted in the exclusion of the Dard group of languages (Dardi, Shina, Kohistani and Kashmiri) from the census count.

The compilation of data for the 18 scheduled languages also contributed to the multiple problems of classification. For example, minor speech communities, such as Chakma and Hajong, were clubbed together with Bengali. Secondly, Yerava and Yerukala were amalgamated with Malayalam and Tamil respectively. Such examples are many. It is obvious that the census preferred to ignore the minor dialect groups.

The story of Hindi is equally interesting. For example, 50 dialect groups have been grouped under Hindi with the result that there is no scope for an analytical study of the geographical spread of these dialect groups. In the course of time many speakers of these dialects have tended to declare Hindi as their mother tongue without making reference to the dialect they use.

This is evident from the fact that some 233 million speakers declared Hindi as their mother tongue. Gradually, the stage is not far when many of the distinguished dialect groups, such as Braj Bhasha, Awadhi, Bhojpuri, Magadhi, Maithili and Marwari, will loose their identity at least in the census records. This withdrawal of patronage by the speakers of these dialects is a symptom of their eventual decline, if not death. A broad classification scheme of the four language families is given in Table 6.1 (for detailed classificatory schemes, see Tables 6.3-6.6).

Numerical Strength:

Of the four language families Indo-European has by far the largest strength of speakers. In fact, three-fourths of the country’s population claimed one or the other language of the Indo-European family as their mother tongue. The Dravidian family comes next with 22.5 per cent of the total population of the country claiming affinity to it.

The speakers of the other two families—Austro-Asiatic and the Tibeto- Burman—consist of small groups. Their overall proportionate share is low: 1.13 and 0.97 per cent respectively. As already indicated, Austro- Asiatic languages are spoken by a host of tribal groups. This is also true for most of the Tibeto-Burman languages.

Among the languages of the Austro-Asiatic family, Santali is the most outstanding speech community, the numerical strength of its speakers being as high as 5.2 million. Other languages of the Munda branch, such as Ho, or of the Mon Khmer branch, such as Khasi, have a numerical strength of less than one million speakers each. Santali speakers account for 55 per cent of the entire strength of the Austro- Asiatic family. Speakers of the Ho, Khasi and Mundari languages account for 10, 9.6 and 9.1 per cent respectively of all Austric speakers.

There are many language groups within the Austro-Asiatic family whose numerical strength is insignificant. Reference may be made to Bhumij, Nicobarese, Gadaba and Juang. However, their declining numerical strength shows that conditions are not favourable for their growth. As indicated earlier, the 1991 census adopted a policy of excluding all languages from the census count whose speakers numbered less than 10,000 persons at the all-India level at the time of census enumeration. This policy was by and large negative to the interests of the tribal languages.

As is evident from Tables 6.3-6.6, there are striking differences in the numerical strength of the languages of the Tibeto-Burman family. The major speech communities include Manipuri/Meithei (1.27 million), Bodo (1.22 million), Tripuri (0.69 million), Garo (0.67 million), Lushai (0.54 million) and Miri/Mishing (0.39 million). The Manipuri and Bodo groups together account for one-third of the total strength of Tibeto-Burman speakers.

As is generally known, the major Dravidian speech communities consist of Telugu, Tamil, Kannada and Malayalam. They have been ranked here in descending order of the strength of their speakers. The Dravidian family also includes minor groups, such as Gondi (2.12 million), Tulu (1.55 million), Kurukh-Oraon (1.42 million), Kui (0.64 million), Koya (0.27 million) and Khond (0.22 million).

Many of them are tribal dialects and have an imminent risk of extinction. Gondi, for example, presents a case of language loss, as its speakers are getting assimilated into the regional languages of the state of their habitation. The same is true for other tribal dialects, unless otherwise they have come under the cover of state protection.

In terms of numerical strength of speakers Hindi is the foremost among the Indo-European languages. With 337.27 million speakers who claimed Hindi, or its different dialects, as their mother tongue, Hindi has no comparison with other languages of the family.

Bengali, Marathi and Urdu which follow in the same order have a numerical strength ranging between 43 and 69 million. Bengali and Marathi account for about 10 per cent each of the total strength of speakers of the Indo-European family. Among the dialects of Hindi, Bhojpuri was claimed by 23,1 million speakers. One can compare Bhojpuri with Assamese (total speakers: 12.96 million) and Punjabi (total speakers; 23.08 million).

The other dialects of Hindi, such as Maithili, Magadhi, Awadhi, Braj Bhasha, Marwari or Chhattisgarhi figure poorly. In fact, the dialect speakers tend to declare Hindi as their mother tongue. The strength of those who declared these dialects as their mother tongue seems to be diminishing with successive censuses. The progress of the languages of the Dard group, namely, Shina, Kohistani and Kashmiri, cannot be monitored since 1991 census was not conducted in Jammu and Kashmir.

As many as 13 of the Indo-European languages have been listed in the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution. They are: Kashmiri (Dard group), Sindhi (northwestern group), Hindi, Urdu, Punjabi, Nepali, Gujarati (eastern, east-central, central and northern groups), Bengali, Assamese and Oriya (eastern group) and Marathi and Konkani (southern group). While Konkani, with a total strength of 1.76 million speakers, is mentioned in the Eighth Schedule, Santali finds no place, although its speakers numbered at 5.22 million at the 1991 census.

Language Domains:

A generalized study of the domains of various languages spoken in India may be helpful in understanding the historical processes leading to their geographic spread and concentration. It may also be helpful in identifying the basic elements of India’s linguistic geography. It may be worthwhile to recapitulate the historical processes that led to the evolution of language regions in India (Box 6.2).

It is understood that the Indo-Aryan was the last to arrive. It was preceded by Dravidian, Sino-Tibetan and Austric. However, there is no clarity about the chronological sequence in which the different families came to affect the situation in India. This question has been partly answered by the linguists. Which came first? Austro-Asiatic, Sino-Tibetan or Dravidian? The Vedic Aryans had the knowledge of the Tibeto-Bur- man-speaking Mongoloids whom they described as the Kiratas. Yajurveda and Atharvaveda as well as Mahabharata and Manu Samhita also mentioned the Kiratas.

Austro-Asiatic Languages:

The domain of the Austro-Asiatic languages lies in the mid-Indian region and extends from Maharashtra to West Bengal. The two outliers of this domain—Khasi and Nicobarese—have their enclaves in Meghalaya and Nicobar Islands respectively. The two pockets are separated by a vast expanse of the sea. Santali is the foremost among the Munda languages. The Santali speakers are mainly concentrated in Bihar, West Bengal and Orissa. About one-half of them live in Bihar, 35 per cent in West Bengal and 13 per cent in Orissa. The Santals living in Assam, numbering 135,000, also declared Santali as their mother tongue at the 1991 census.

Another significant language of the Munda branch is Munda/Mundari. Of the 1.27 million speakers of Mundari, 54 per cent live in Bihar, 31 per cent in Orissa and only 6 per cent in West Bengal. The domain of the Ho language lies in Bihar and Orissa. Two-thirds of all Ho speakers are confined to Bihar and the remaining one-third to Orissa. The territories of the Kharia, Korku and Savara languages extend over Bihar, Orissa and Madhya Pradesh. However, the Savara speakers are mostly confined to Orissa.

Tibeto-Burman Language:

The territory of the Tibeto-Burman languages is by and large conterminous with the Himalayas and extends from Baltistan and Ladakh in Jammu and Kashmir to Arunachal Pradesh. It extends further to encompass other northeastern states. The Bhotia and the Himalayan groups of the Tibeto-Burman family are confined to Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, hilly Uttar Pradesh and Sikkim. The Tibetan speakers, however, have a wider spread as they are distributed over many states in India. The Tibetans are of course in exile in India and live in camps and colonies especially created for them in several states. Notable among the languages of the North Assam branch of the Tibeto-Burman family are Miri/Mishing and Adi.

More than 97 per cent of the Adi speakers are confined to Arunachal Pradesh. The Miri/Mishing speakers, on the other hand, are confined to Assam. Of the languages of the Bodo group, Bodo is largely specific to Assam where 97 per cent of its speakers live. The domains of the Garo and Tripuri lie in Meghalaya and Tripura respectively.

About 80 per cent of the Garo speakers are confined to Meghalaya whereas 17 per cent of them are based in Assam. About 93 per cent of the Tripuri speakers are confined to Tripura, although in recent years a section of their population has also moved out to Mizoram and Assam. The Bodo group also includes Karabi/Mikir and Rabha dialects.

Their speakers are mostly concentrated in Assam and Meghalaya. However, a small proportion of Rabha speakers is also found in the northern districts of West Bengal. Likewise, the Koch is confined to Meghalaya and Assam, Dimasa to Assam and Nagaland, and Lalung is specific to Assam alone. Most of the speech territory of the Naga group of languages is shared between Nagaland and Manipur. While Ao, Angami, Lotha, Pochury, Phom, Yimchingure and Khiemnungan are exclusive to Nagaland, Kabui and Tangkhul are specific to Manipur. On the other hand, Khezha and Mao are spoken both in Manipur and Nagaland. However, a small proportion of their speakers are also located in Assam.

The Kuki-Chin languages are confined to the states of Manipur and Mizoram. Manipuri (including Meitei) has its domain in the central valley of Manipur where 87 per cent of its speakers live. A section of the Manipuri population (about 10 per cent) has also moved out to Assam. Manipuri speakers were also enumerated in Tripura, Nagaland and other parts of the northeast, although in small numbers. Lushai is confined to Mizoram. Manipur presents a case of linguistic plurality. In fact, the state is the home of many speech communities belonging to both the Naga and Kuki-Chin groups.

Notable among these dialects are Thado, Paite, Halam, Hmar, Kabui, Tangkhul, Gangte, Khezha, Kom, Kuki, Liangmei, Lushai, Mao, Maram, Maring, Vaiphei, Zeliang, Zemi and Zau. Lakher has its domain in Mizoram only. Migration in recent years has taken the Kuki speakers to other parts of the northeast, such as Assam, Nagaland and Tripura. Manipur may be chosen as an example to illustrate the territoriality of minor language groups in a contiguous geographical space. The people of Manipur exhibit a complex pattern of ethnic diversity, where each ethnic or dialect group tends to concentrate in a monolithic world of its own.

Broadly speaking, the population of Manipur consists of two different groups:

(a) Palaeo-Mongoloids consisting of

(i) The Meiteis, and

(ii) The hill tribes; and

(b) Immigrants mostly consisting of Palae-Mediterraneans further sub-divided into

(i) The Pangals (Muslim settlers), and

(ii) The Mayangs or Kols. Each of these groups can be further sub-divided on the basis of language/dialect and racial attributes.

While the Meiteis, Pangals and Mayangs are plain-dwellers, the tribes, such as Kuki-Chins and Nagas are hill-dwellers. The ethno- lingual situation in Manipur suggests that geographical factors have promoted the emergence of homogeneous dialect territories. Each dialect is confined to a pocket where people communicate in a given dialect. These monolithic dialect territories are contiguous. This linguistic plurality has survived the onslaught of time.

In his doctoral thesis Hemkhothang Lunghdim examined the patterns of communication in the multi-speech area of Manipur. The presence of as many as 29 major speech communities in Manipur has contributed to a type of ethno-centrism for the survival of speeches or Patois coupled with other socio-cultural differences.

Ethnic groups have often indulged in competition resulting in inter-ethnic conflicts. In any case ethnic groups strive for the preservation of their dialects even if it results in diminishing interaction between different dialect groups. Over time linguistic plurality has resulted in bilingualism or multilingualism. Many tribes have adopted elements of Meitei-Lon for mutual inter-communication (Box 6.3).

Dravidian Languages :

As is generally known, the four southern states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Kerala are the home of the major Dravidian languages, viz., Telugu, Kannada, Tamil and Malayalam. The speakers of these languages have also moved out to other states, particularly the neighbouring states of the south in the recent past. The geographical spread of these languages is evident from Table 6.7.

Evidently, these languages display a high degree of concentration in their home states. The highest degree of concentration is seen in the case of Malayalam, followed by Tamil. On the other hand, the lowest degree of concentration is revealed in the case of Telugu. There are several minor speech communities within the Dravidian family. Notable among them are: Yurukala, Yerava, Tulu, Coorgi, Gondi, Malto and Kurukh-Oraon. The Kurukh-Oraon and Malto are confined to Bihar. They belong to the northern branch of the Dravidian family.

Gondi, which is classified as a language of the central Dravidian branch, is the traditional dialect of the Gonds. However, recent census data show a steep decline in the numerical strength of the Gondi speakers. At the 1991 census, the Gondi-speaking population numbered just 2.12 million. This is an indication of the loss of language due to assimilation into the dominant regional languages. More than 90 per cent of the Gondi (mother tongue) speakers live in Madhya Pradesh (70 per cent) and Maharashtra (21 per cent). The remaining population is found in Andhra Pradesh and Orissa. In other states, their number is too small.

Indo-European Languages:

Both in terms of numerical strength and the territorial extent the Indo-European languages surpass all other language families in India. The speech territory extends from Rajasthan in the west to Assam in the east and from Jammu and Kashmir in the north to Goa in the south. In fact, the domain of the Indo-European family extends beyond the borders of Rajasthan on the west and continues over adjoining Pakistan. Notable among the languages of this family are Hindi, Bengali, Marathi, Urdu, Gujarati, Oriya, Punjabi and Assamese. Keeping in view their importance as many as 13 of the Indo-European languages have been included in the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution.

While Hindi and Urdu are spoken across many states, including southern states, other languages, such as Bengali, Marathi, Gujarati, Oriya, Punjabi and Assamese, are specific to their own states. For example, while Bengali is specific to West Bengal, Marathi and Gujarati have their domain in Maharashtra and Gujarat respectively. The dominance of Hindi is evident from the fact that there were 337 million speakers who claimed it as their mother tongue in the 1991 census. About 81 per cent of the total population of Bihar, 91 per cent of Haryana and 89 per cent of Himachal Pradesh claimed affinity to Hindi.

The respective percentages for Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh were 89 and 90. The story of the Hindi-speaking population is rather complicated. There are no less than 50 dialects which are grouped under Hindi. The speakers of these dialects declared them as their mother tongue in the same way as millions of others accepted Hindi as their mother tongue without making any reference to the dialect used by them.

These dialects are actually regional variants of a spoken language of which the standardized form written in the Devnagri script is the official Hindi. Three-fifths of all Hindi speakers are concentrated in the two northern states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. Of the remaining, about 17 per cent live in Madhya Pradesh and 12 per cent in Rajasthan. The rest of the Hindi- speaking population is found in Haryana, Delhi, Himachal Pradesh, Maharashtra and West Bengal (Fig. 6.5).

In terms of numerical strength Bengali comes next to Hindi. While its speakers are heavily concentrated in West Bengal, a sizeable proportion of Bengali speakers is also found in the neighbouring states of Assam, Bihar and Tripura. Marathi is next to Bengali. About 93 per cent of its speakers live in Maharashtra alone. However, Marathi is also spoken by a section of population in Karnataka as well as Madhya Pradesh. Urdu holds the fourth rank among the Indo-Aryan languages. Its core region overlaps with that of the Hindi.

While the domain of Punjabi lies in Punjab, it is widely spoken over the entire northwestern region, particularly Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir and northern Rajasthan. Its territorial extent is wider as Punjabi is spoken in the neighbouring Punjab in Pakistan. Within India migration processes have taken Punjabi-speaking population to different parts of the country (Fig. 6.7).

In the east, almost 99 per cent of the Assamese speakers are confined to Assam. The domain of the Assamese is surrounded on the north, east, south-east and the south by Tibeto-Burman and Austric languages. There is a slight spill-over of the Assamese population into the neighbouring states of Arunachal Pradesh and Meghalaya (Fig. 6.8).

In fact, they mainly live in the littoral region in the neighbourhood of Goa. Some speakers of the Konkani have also dispersed to other neighbouring states, such as Kerala and Gujarat as well as the union territory of Dadra and Nagar Haveli. Since the 1991 census was not conducted in the state of Jammu and Kashmir, the home of the Kashmiri language, it is difficult to describe the patterns of geographic distribution of the Kashmiri speakers.

Outside the state a population of 56,000 persons returned Kashmiri as their mother tongue. The Nepali-speaking population is distributed in a number of states, mostly in the neighbourhood of Nepal. Of the 2.07 million Nepali speakers, more than 40 per cent are concentrated in West Bengal and another 21 per cent in Assam. A small proportion (12.35 per cent) of the Nepali speakers is also found in Sikkim. They are scattered all over the northeast although in small numbers. The domain of Sindhi lies in the Sind province of the neighbouring state of Pakistan. The present Sindhi-speaking population in India, however, consists of population displaced in the wake of Partition in 1947.

Initially, the Sindhis came to the neighbouring regions of Rajasthan and Gujarat. Later, they dispersed to other western and northern states. At the 1991 census, about two-thirds of all Sindhi speakers in India were enumerated in Gujarat and Maharashtra. Of the remaining one-third, the two states of Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh shared together 15 per cent each. A small proportion of Sindhi speakers are also found in Delhi and Uttar Pradesh.

Language Scene in Tribal Areas:

The language scene in tribal areas of India deserves a mention. During the 50 years since independence, the tribes have been exposed to diverse influences—economic, political and socio-cultural. The scene in northeastern India is somewhat different. There, the tribes have been empowered to manage their own political affairs.

In other regions of India a certain number of seats have been reserved for the tribes to ensure their representation in the state and the national legislative bodies. These measures have paved the way for their rehabilitation in the national polity. However, a majority of Indian tribes lives in the mid-Indian region where their participation in the political processes is nominal.

Their traditional habitats lie divided between several states. They do not have much of a say in policy formulation. This has left an imprint on their traditional culture, language and social structure. Language seems to have suffered the most.

First, the developmental processes initiated since independence seem to have contributed towards the disintegration of tribal economies, and their communitarian way of life. The tribes have lost their hold on the forest resources and have been forced to depend on the market forces. In fact, the free market economy has encircled completely the petty tribal commodity trade.

Secondly, expansion of primary education has brought tribal children face to face to a new cultural situation. In the course of schooling they have been exposed to the regional languages of the states of their habitation. This has paved the way for their becoming bilingual. The ultimate effect is on their traditional dialects which are on the way to decline and eventual death.

It has been noted that the Indian tribes display a very high degree of diversity in their language affinity. Despite the relative isolation of the tribal communities there have been contact areas in which give- and-take between the tribal and non-tribal languages has continued throughout history.

The geographic patterning of tribal languages suggests that along the zone of contact between them and the non-tribes progressive interaction has resulted in the fusion of linguistic elements on either side. This is evident from the fact that while the tribes communicate mainly in the Nishada, Kirata and Dravidian languages, they have also adopted several speech-forms of the Indo-Aryan family. The incidence of bilingualism and multilingualism among the tribes has increased phenomenally.

One may develop an understanding of the linguistic plurality observed in tribal areas by selecting the case of Austric-speaking tribes. In India, the Austric-speaking tribes are grouped into Mon-Khmer and Munda branches of languages. We have already seen that the Munda- speaking zone extends over a vast area from the Aravallis in the west to the Raj Mahal hills in the east.

Language Shift:

A striking feature of the language scene in tribal areas is the growing shift in language affinity of the tribal communities. This fluid situation in which the tribes are losing their linguistic identity and are being identified with languages spoken by other tribes or the dominant regional languages of the states in which they have been living is observed in many parts of India.

An evaluation of the census data reveals gaps between the numerical strength of the ethnic tribals, say the Mundas, Santals and the Gonds and those sections of the Munda, Santal and Gond population who declared their own dialects as their mother tongue, say at the 1961 census. This lack of conformity between ethnic identity and language affinity reveals the process of language shift in a significant way. There can be several plausible explanations for this phenomenon. It may be assumed that by 1961 a major shift in the linguistic/dialectal affinity of the Indian tribes had already taken place in certain regions of the country. The 1961 census may, however, be taken as a benchmark.

It may be assumed that as tribal/non-tribal interaction was growing, a section of the tribal population shifted to other dialects/ languages with which it has no traditional affinity. This shift to the dominant languages of the regions of their habitation indicated a process of language shift and assimilation into the regional languages. The language shift was, however, not necessarily from a tribal to a non-tribal dialect. In fact, several tribal groups shifted over to the other tribal dialects as contacts between them were growing fast.

As a result they lost their own traditional dialects. The 1961 census data on linguistic affinity of the tribal communities as revealed in their declaration of a particular language as their mother tongue makes it possible to analyze the following dimensions of language shift among the tribes:

(a) Tribes speaking a dialect with which they are traditionally identified. For example, Santals declaring the Santali as their mother tongue or Gonds declaring Gondi as their mother tongue. This reveals that the tribes in certain regions of the country display continuity in their language affinity. We may call it a case of language retention.

(b) Tribes declaring a regional language as their mother tongue. For example, Santals declaring Bengali as their mother tongue in West Bengal, or Gonds declaring Oriya as their mother tongue in Orissa. This shows the ongoing process of language shift indicating that the tribal communities are getting assimilated into

the dominant regional languages. Tribal regions where the process of regional development has brought tribes face to face to non-tribes have witnessed this phenomenon more significantly.

(c) Tribes on the periphery of their traditional areas have a tendency to declare as their mother tongue a language which is spoken by a dominant tribal group or the official language of a neighbouring state. This process indicates that the tribes are getting exposed to other tribal/regional languages. As a result they are getting assimilated into these languages (Table 6.8).

Language Retention:

While collection of data on mother tongues may replate with problems, the position as recorded by the 1961 census was that one-half of the tribal population of India retained their own dialects as mother tongues. This was an evidence of language retention. The situation, however, varied from tribe to tribe and from region to region.

The geographic patterning of the tribes still claiming affinity to their own tribal dialects revealed three major formations:

(a) Areas of tribal fastness in which tribes were by and large living in a state of exclusivity. For example, in Mizoram, Manipur, Meghalaya, Tripura, Nagaland, Arunachal Pradesh, West Bengal, Rajasthan, and Himachal Pradesh, 70-100 per cent of tribes retained their traditional dialects as their mother tongue.

(b) Areas of tribal-non-tribal inter-mingling, where tribes were living in a state of varied degrees of exposure to non-tribal economic and cultural influences. One can cite the case of Assam, Orissa, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra and Mysore (now Karnataka) where 25-60 per cent of tribes retained their own language.

(c) Areas where tribes have been assimilated into dominant cultures of the regions of their habitation. In these areas less than 10 per cent of the tribal population claimed affinity with their own traditional tribal dialect (Table 6.9).

A number of doctoral theses, written under the direction of this writer at the Centre for the Study of Regional Development of the Jawaharlal Nehru University, explored these questions at length. In two of these theses the question of language shift and retention as registered among the Austric-speaking tribes of the mid-Indian region was examined.

These studies revealed that the Santals and Korkus by and large preferred to retain their traditional dialect.’ On the other hand, there were other Austric-speaking tribes who displayed a tendency of shift to the regional languages. The language shift was the highest among the Savaras. The Kharias, Mundas and the Hos followed.

Studies also revealed that the Bhils of Rajasthan, Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh preferred to claim regional language as their mother tongue. A study of the household-level data generated through field- work from Wanera Para, Umedgarhi, Nai Abadi and Regania villages of Bagidora tehsil of Banswara district, as well as from Banswara town, revealed that the Bhils by and large maintained Bhili as their mother tongue.

On the other hand, the Korkus of Punasa, Richhi and Udaipur villages of Khandwa district tended to switch over to the regional languages. In fact, they declared Nimadi as their mother tongue. However, no generalizations can be made about Korkus on this basis as in other villages they continue to retain their own dialect and declare it as their mother tongue at the successive censuses.

Another finding of this research is that tribes living in rural areas have a greater affinity with their traditional dialects as compared to the tribes in urban areas. In regions of tribal concentration, for example, tribes enjoyed a certain degree of isolation which helped them retain their language and culture.

Their stay in cities and towns, on the other hand, diluted their cultural identity and their language was the first casualty. Investigations at the household level confirmed the language shift among the Mundas of Ranchi town and the Korkus of Khandwa tehsil, East Nimar district. On the contrary, the Bhils of Banswara district, the Santals of Santal Parganas, the Korkus of Khalwa tehsil (East Nimar district) and the Mundas of the rural parts of Ranchi district have continued to retain their language.

The study noted a strong correlation between language shift and a number of associated factors, such as urbanization, proportion of Hinduized tribes, and the proportion of non-primary workers. Literacy also revealed a high positive correlation with language shift. In fact, the school-going tribal children were receiving education through the medium of regional languages.

Obviously, schooling became a powerful instrument of bilingualism and/or language shift. In terms of exposure of the mid- Indian tribes to regional languages, Bhils stand first, followed by Mundas, Korkus and Santals. In any case, loss of language is symptomatic of the loss of cultural identity.

While the incidence of bilingualism among the Indian tribes is very high,’ it does not mean that they have always retained their traditional languages. This is understandable in view of the fact that most of the tribes are getting exposed to external influences, particularly at the schools and the market places. Interaction at these places is possible through a common language, generally a regional language or pidgin, such as the Sadan/Sadari in Ranchi, which is adopted by the tribes for day-to-day communication. Back at their homes, their own dialect reigns supreme. This may not be true for the displaced tribals whose number is increasing day by day.

Related Articles:

- Linguistic Diversity in India

- Classification of Tribal Groups of India – Essay

No comments yet.

Leave a reply click here to cancel reply..

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- AsianStudies.org

- Annual Conference

- EAA Articles

- AAS Community Forum Log In and Participate

- AAS-in-Asia Conference July 9-11, 2024

Education About Asia: Online Archives

Multilingualism in india.

With a growing population of just over 1.3 billion people, India is an incredibly diverse country in many ways. This article will focus specifically on contemporary linguistic diversity in India, first with an overview of India as a multilingual country just before and after Independence in 1947 and then through a brief outline of impacts of multilingualism on business and schools, as well as digital, visual, and print media.

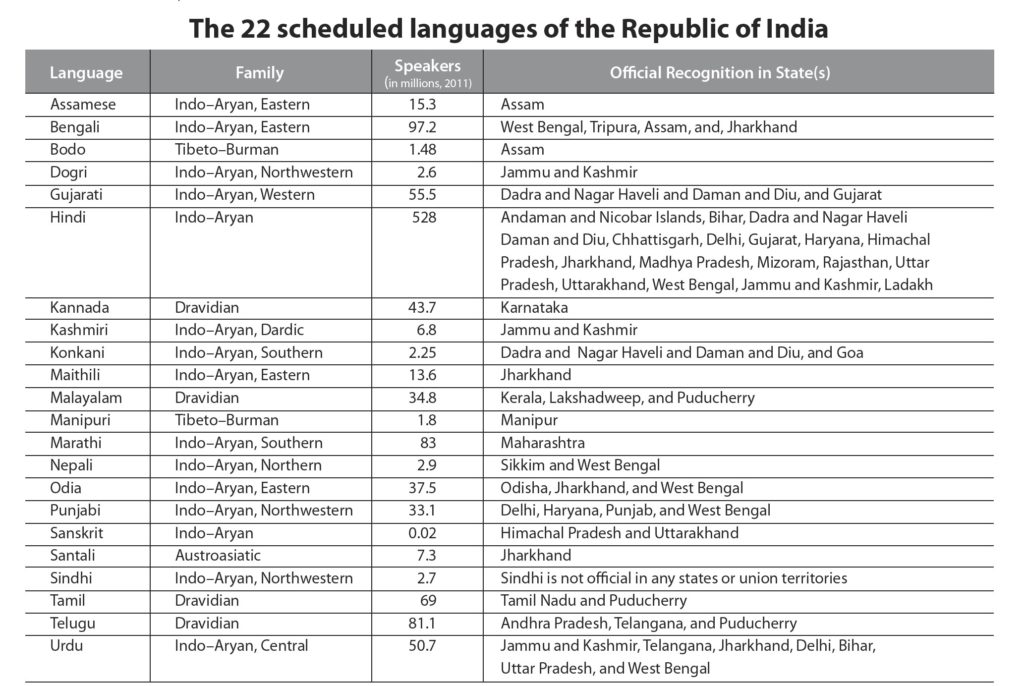

India is home to many native languages, and it is also common that people speak and understand more than one language or dialect, which can entail the use of different scripts as well. India’s 2011 census documents that 121 languages are spoken as mother tongues, which is defined as the first language a person learns and uses.1 Of these languages, the Constitution of India recognizes twenty-two of them as official or “scheduled” languages. Articles 344(1) and 351 of the Constitution of India, titled the Eighth Schedule, recognizes the following languages as official languages of states of India: Assamese, Bengali, Bodo, Dogri, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Kashmiri, Konkani, Maithili, Malayalam, Manipuri, Marathi, Nepali, Oriya, Punjabi, Sanskrit, Santhali, Sindhi, Tamil, Telugu, and Urdu.2

Six languages also hold the title of classical languages (Kannada, Malayalam, Odia, Sanskrit, Tamil, and Telugu), which are determined to have a history of recorded use for more than 1,500 years and a rich body of literature. Furthermore, for a contemporary language to also be a classical language, it must be an original language and cannot be a variety, such as a dialect, stemming from another language. Just as there are many people who wish for their mother tongues to be recognized as official, scheduled languages, there are also efforts to add Indian languages to the list of classical languages. Once a language has the official status of a classical language, the Ministry of Education organizes international awards for scholars of those languages, sets up language studies centers, and grants funding to universities to promote the study of the language. Interestingly, the Constitution of India lists no national language for the country as a whole.

Of the official, scheduled languages, Modern Standard Hindi—as an umbrella term for a family of languages—has the most mother tongue speakers, with around 528 million speakers, or 44 percent of India’s population, followed by Bengali with around 97 million speakers, or 8 percent of the population. Marathi has around 83 million speakers, or 7 percent of the population, and Telugu speakers number around 81 million, or almost 6 percent of the population. Speakers who list the remaining official languages as their mother tongues also number between 2 and 4 percent of the population, as recorded in the 2011 census. It is interesting to note that due to India’s large population, native speakers of these regional Indian languages often outnumber native speakers of other major world languages such as Korean—with 77.2 million native speakers—and Italian—with 67 million native speakers—as of 2020.3

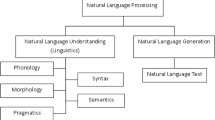

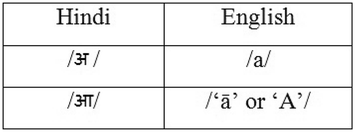

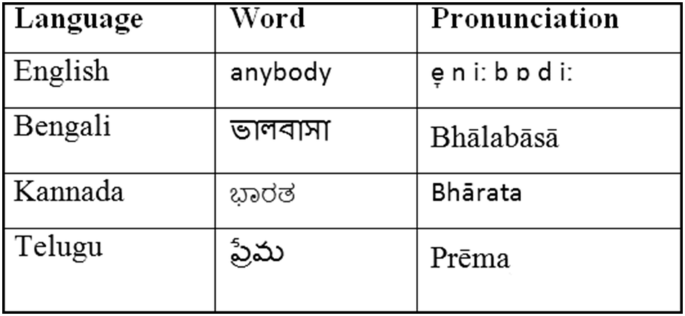

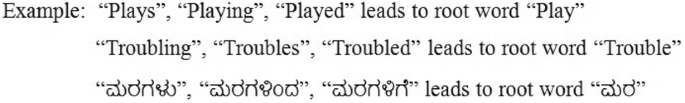

Languages in India are categorized into language families based on their different linguistic origins, which often include different scripts as well. The main language families include Dravidian, Indo–Aryan, and Sino–Tibetan. Bodo is the Sino–Tibetan language spoken in northeastern Indian states with the most speakers (1.4 million). Languages considered to be mother tongues or regional languages in the south of India have grammatical structures and scripts with Dravidian roots, and languages used in the central and northern regions of India are part of the Indo–Aryan family of languages. Many central and northern Indian languages use scripts derived from the Nagari script. Contemporary variations of Hindi use the Devanagari script, and scripts used in Gujarati, Punjabi, and Marathi use Nagari-derived scripts or versions of Devanagari that include some differences in their alphabets.

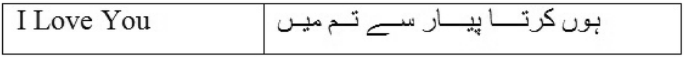

Similarly, Modern Standard Hindi and Urdu are grammatically identical, though they often differ in some vocabulary and their use of scripts, as Urdu uses a modified form of the Perso–Arabic script. As Hindi and Urdu are often considered to be one language with two scripts, a common belief is that the distinction among speaking and writing Hindi and Urdu falls along a religious divide between Hindus and Muslims, where Hindus are listed as Hindi speakers and Muslims as Urdu speakers in government documents such as the census.4 However, in practice, the distinction between Hindi and Urdu speakers is much more fluid and complex, as linguistic boundaries rely more on geographic location and speech community.

Another aspect of India’s multilingualism is that each mother tongue, or regional language, roughly belongs to one or more states. India’s twenty-eight states have been largely organized along linguistic lines since the 1950s, just after Independence, with the formation of the southeastern state of Andhra Pradesh in 1953 for Telugu speakers. Andhra Pradesh was created after prolonged protests and strikes by Telugu speakers, which included the prominent activist Potti Sreeramulu fasting for the creation of a Telugu state until his death in 1952.5 A new state was finally created in 1953 by dividing the Tamil- and Telugu-speaking regions in what, under the British, was called the Madras Presidency. Immediately after Independence, the country retained similar political divisions it had under colonial rule, which newly independent Indians felt did not accurately represent them in the new government. The state reorganization movement for Andhra Pradesh culminated in the government-organized Dhar commission, which was ordered to investigate reordering additional Indian state borders along the lines of linguistic communities, or groups of people who speak the same language. The commission produced the State Reorganization Act of 1956, which called for states to be formed to represent linguistic groups rather than to stay the way the country was divided over the course of British rule.

Following the division of the state of Andhra Pradesh and the orders of the State Reorganization Act of 1956, the states of Kerala, Mysore, and Madras were formed. (In 1969, Madras was renamed Tamil Nadu, and in 1973, Mysore was renamed Karnataka.) In 1956 as well, the princely state of Hyderabad was divided between Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Madhya Pradesh. Just as the state of Andhra Pradesh was formed after prolonged protests for the rights of Telugu speakers, the Province of Bombay was also divided between Marathi and Gujarati speakers in 1960 into the states of Gujarat and Maharashtra. The bustling port city of Bombay, later renamed Mumbai in 1995, became part of the state of Maharashtra. Large reorganization efforts along the lines of language and religious communities continued with the 1966 reorganization of Patiala and East Punjab States Union (PEPSU) and Punjab into three new states, Punjab, Haryana, and Himachal Pradesh; and India’s northeastern region also underwent a linguistic and communal reorganization into different states between the years of 1963 and 1987.

Multilingualism in India has therefore played a key role in the country’s contemporary politics. State boundaries were drawn along the lines of language groups, even though regions remain linguistically diverse, because languages in India can be an important way of defining one’s identity. Many people in different Indian regions in cultural and religious groups retain distinct identities that set them apart from other communities through language. As India is culturally, ethnically, and religiously diverse, language is one way people maintain group identities. Identity politics have also made mother tongues an object and mode of political struggle. Authors of the State Reorganization Act felt that democratic participation would grow if local populaces could access information and participate in government programs in their mother tongues. Language is a basis of identity and is why, when state boundaries were being redrawn after Independence in 1947, languages and the areas in which they were spoken were utmost factors of importance in where the boundaries of new Indian states would be.

Today, there are twenty-eight states in India and eight union territories, or areas directly governed by the federal government, and each state has at least one official language and many have two, in addition to English. In this way, with unique languages and scripts attributed to each state, India often seems like a collection of distinct countries due to the cultural and linguistic differences between states. Due to this vast diversity in languages and the way language is closely tied to identity, sometimes there are also struggles along religious and political lines that play out through language. Hindu nationalists engage in movements to spread the use of Hindi and Sanskrit as a means to spread the Hindu religion as well. Some have also felt that the distinct regional languages of states should indicate that people who do not speak those languages from birth should not be allowed to reside and work in states where they do not belong to the linguistic community. This was the message of the conservative party, the Shiv Sena, in Maharashtra.

English as an Indian Language

Adding to the complexity of the history of languages in South Asia, the English language was also integrated into the social fabric of the region insofar as it played a key role as a unifying language in the Constitution among north and south India at the time of Independence in 1947. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (1869–1948), also known by the name Mahatma, which means “Great Soul,” was a famous activist who led many Indians in peaceful protests against British rule. Gandhi and his supporters made concessions for the English language to remain in use in the new nation. They found English incredibly useful for unifying the country despite their support for Hindustani, the name for the mix of Hindi and Urdu commonly used in the northern regions of India, as the national language.

Paradoxically for Gandhi and his supporters, English represented a dividing force that emphasized the distance between educated Indian elites, who were more aligned with British colonizers, and non-English-speaking, often-uneducated masses. Gandhi maintained that to have a successful Independence movement was to govern through Indian ways, including through Indian regional languages. During the late colonial period, Gandhi addressed audiences from 1916 to 1928 over English linguistic colonization in education. He called for education in regional languages, stating, “The question of vernaculars as media of instruction is of national importance,” and he criticized how “English-educated Indians are the sole custodians of public and patriotic work”; he also said the “neglect of the vernaculars means national suicide.”6 However, the question of a national unifying language at Independence was a complicated one, as Gandhi’s call for Hindustani to wholly replace English was also rejected. Hindustani, later known as a variety of Hindi and Urdu, is not commonly spoken across all of India, and it is considered a northern Indian regional language since it is distinct from the language families and scripts used in south India. English, therefore, served as a utilitarian language to connect disparate and diverse areas of the newly unified country, as it still does today. Now, Indian English, with a unique vocabulary and accent, is a recognized variety of English in the world.

Ultimately, the English language was written into India’s new Constitution as a language to help with the new country’s transition from a British colonial subject to independent governance. Specifically, the 1949 original Constitution of India states that “business in Parliament shall be transacted in Hindi or in English” in Article 210, Article 343 states that “the official language of the Union shall be Hindi in Devanagari script” and “for a period of fifteen years from the commencement of this Constitution, the English language shall continue to be used for all the official purposes of the Union for which it was being used immediately before such commencement: provided that the president may, during the said period, by order authorize the use of the Hindi language in addition to the English language.”7 The intention of including English as a language for official government purposes along with Hindi was that English would be shed as the new nation matured.

In 1963, the impending transition away from English brought about similar concerns over the need for a unifying language, which were voiced at the time of Independence. Parliament enacted the Official Languages Act of 1963 to continue the use of English and section 3 of the act extended the implementation of English for official purposes along with Hindi.8 India decided to keep English as a unifying language to connect parts of the country where Modern Standard Hindi is not commonly spoken, such as in the southern Indian states with different scripts and language roots. While English is also a legacy of the British in India, it remains a tool and window through which to gain wider knowledge and understanding of the country. English also connects India with other English-speaking regions of the world.

Multilingualism in Daily Life

As there are many languages in India, many Indians can speak, read, and/or write in multiple languages, and multilingualism therefore is a part of daily life. Challenges and advantages of linguistic diversity affect the everyday lives of Indians in terms of businesses, educational institutions, and media. Due to the widespread use of English in India, the country is home to many international companies where English is commonly used for work. As English fluency often means higher socioeconomic status in India, middle- and upper-class Indians who have greater access to English have relative ease when working, studying, traveling, and immigrating to areas of the world where English is a lingua franca, or common language.

English is used in many office settings, especially in the international businesses and multinational corporations housed in India. Businesses in Indian cities hire employees from all over the country, and English is a common language among people with different mother tongues. In shops and supermarkets, many labels are written in English in the Roman script.

Other than English in business and commerce, many people also use Modern Standard Hindi as a common language, especially in the northern regions of India. In many of these places, mixing two or more languages or language varieties together when speaking is a prevalent practice known as “code-switching.”

Example of code-switching in conversation:

Waiter: Aur chahiye ? (Do you want anything else?) [Hindi] Man: Don coffee pahije (We want two coffees) [Marathi]

Code-switching as a practice is distinct from commonly used English words that have been subsumed into other Indian languages, which are called “loan” or “borrowed” words.9 While English and forms of code-switching are incorporated into Indian corporate culture, many people find themselves facing barriers to communication in these settings if they are not fluent in English or Hindi.

Example of loan words:

Teacher to the class: OK, all of you, open like this. Saglyana asa ghya aani, first page ogu-da, first page war kay lihile ? (Everyone take it like this and open to the first page. On the first page, what is written?) [English and Marathi]