A Level Philosophy & Religious Studies

Model essay plans for theories of perception

AQA Philosophy model essays

Note that this model essay plan is merely one possible way to write an essay on this topic.

Points highlighted in light blue are integration points Points highlighted in green are weighting points

This page contains essay plans for Direct realism, Indirect realism and Idealism.

Direct realism

- Direct realism – the view that the objects of perception are mind-independent objects and their properties.

- This theory is realist as it claims there is a mind-independent reality.

- We perceive reality immediately. We do not perceive a mental representation of reality like sense data. We simply perceive objective reality without any mediation.

- This gives direct realism the strength of seeming to avoid scepticism. If direct realism is true then all our perceptions are veridical.

The perceptual variation issue

- Russell’s table: imagine a shiny table with a beam of light falling on it from a window.

- If you stand in different places in relation to the table, the light can appear to fall on different parts of the table.

- This makes different areas of the table appear lighter brown or darker brown.

- So, this shows that the colour of the table cannot be a mind-independent property of it. It depends on the mind perceiving it.

- Russell also points to the texture of the table feeling smooth, but under a microscope appearing bumpy, or the shape of the table being square or rectangular depending on where you stand.

- Locke’s illustration – if a person puts one hot hand and one cold hand into some lukewarm water, it will feel hot to one hand but cold to the other.

- So, direct realism is false.

- An intrinsic property is a property a thing has in itself.

- A relational property is a property a thing has due to its relation to something else.

- Perceptual relational properties exist due to the relation of a thing to an observer.

- So the direct realist could say that a certain part of the table has the relational property of ‘looking light brown’ to some observer conditions, while also having the relational property of ‘looking dark brown’ to other observer conditions.

- Similarly, Locke’s water has an intrinsic property of a certain temperature, but it can also have the relational property of ‘feeling hotter than’ and ‘feeling colder than’ depending on the temperature of the organ used to perceive it.

- Locke’s illustration only shows that it’s possible for a single observer to directly perceive two different relational properties at once.

- Direct realists claimed that the objects of perception are mind-independent objects and their properties.

- They can thus respond that this includes relational properties.

- So, perceptual variation does not undermine direct realism.

- Sometimes we directly observe an object’s relational properties, which can make it appear different to its intrinsic property, however we still directly observe its properties.

Evaluation:

- Some could attack the relational properties as ‘mind-dependent’. However, they are not. A square table would really have the relational property of ‘looking rectangular’ to a certain perceiver from a certain physical angle, even if there was no perceiver.

- Perceptual variation could be explained by either relational properties or sense data.

- Indirect realism faces the issue of scepticism since it claims we never directly perceive reality.

- Ockham’s razor also shows that direct realism is simpler due to not proposing that sense-data exists.

- This puts direct realism in a stronger position than indirect realism.

- So, we seem justified in accepting its relational property explanation of perceptual variation over the indirect realist sense data explanation.

- However, the relational properties response arguably leads to scepticism.

- If one person sees the table as light brown and another as dark brown, this creates a sceptical issue for direct realism. How could we ever know what colour the table actually is? How can we tell which perception is directly perceiving the intrinsic property?

- We could never tell what the actual intrinsic property of an object is, since every time we perceive it for all we know we could be perceiving its relational properties instead.

- So, direct realism is unconvincing as it is not in a stronger position than indirect realism regarding scepticism.

The hallucination issue

- P1. According to direct realism, if I perceive object p, then object p exists mind-independently.

- P2. During a hallucination I observe an object p , but there is no object p.

- C1. Therefore, the object of perception p must be mind-dependent sense data.

- P3. Hallucinations can be subjectively indistinguishable from veridical perception.

- C2. Therefore, in all cases, the objects of perception are mind-dependent sense data. So direct realism is false.

- The disjunctive theory of perception

- Firstly, P1 & P2 does not justify C1. Hallucinations might not be sense data since they might not be perceptions at all – they could be uncontrollable projections of the imagination, which explains their being mind-dependent.

- Secondly, P3 does not justify C2. It could be true that hallucinations are mind-dependent, and yet other perceptions are not mind-dependent.

- Just because hallucinations look like ordinary perceptions, even if they were mind-dependent, that wouldn’t prove that ordinary perceptions are mind-dependent.

- Just because we are epistemically unable to tell them apart, doesn’t mean they are ontologically the same type of thing.

- So, direct realists could still be correct about perceptions being of mind-independent objects.

- There is still a sceptical issue for direct realism arising from this, however.

- If hallucinations appear like ordinary perceptions, then even if technically that doesn’t mean they are like ordinary perceptions, nonetheless we still can’t tell them apart.

- This means that all of our perceptions could be a hallucination for all we know. So, we can’t gain knowledge from perception.

- This version of the hallucination argument is in a stronger position because it cannot be avoided by the disjunctive theory of perception.

- So, direct realism leads to scepticism – making it less convincing as an epistemological theory of perception.

The time lag argument

- It takes time for light to bounce off an object and then enter our eyes.

- This means that our perceptions of objects are not as they exist exactly now, but at some time in the past.

- This seems to question whether we are seeing objects directly.

- This becomes clearer with the example of distant stars. Their light can take millions of years to reach us. Some of the stars we see have actually exploded or died, but we still see them.

- It can’t make sense to say we are directly perceiving something if it doesn’t actually exist.

- The objects of perception cannot be a mind-independent object, if that object does not exist.

- However, the direct realist can respond that this issue confuses what we see with how we see.

- Light is a physical medium by which we perceive objects.

- We don’t actually perceive the light itself, except in special cases – like seeing light reflecting off paper or a lake.

- Normally, when perceiving an object, we simply perceive the object, not the light.

- Light therefore does not mediate our perception – it doesn’t present us with a representation that we perceive (since we don’t perceive the light). It simply presents us with the object itself.

- Light is how we perceive objects, but not what we perceive.

- Light delays our perception because it takes time, but it does not mediate our perception.

- Directness does not require instantaneity.

- Time lag can only show that our perception is delayed, not that it isn’t direct.

- Direct realists can thus be successfully defended because the necessary condition of directness is immediacy, not instantaneity.

- Seeing something directly doesn’t require seeing it as it is now, it simply requires that our perception of it is not mediated, that we aren’t perceiving it ‘through’ something else (like sense data) that represents it.

- We are just directly perceiving the object, but as it was, not as it currently is.

- Direct realism only claims that the objects of perception are mind-independent objects and their properties.

- Direct realism is not committed to the objects we perceive actually existing at the moment of perception. It claims only that our perception of them is direct – unmediated.

Conclusion:

- Direct realism can be defended against the time-lag argument. The perceptual variation and hallucination issues cannot prove direct realism false because of the appeal to relational properties. However that defence did lead to scepticism. So, direct realism is unconvincing as an epistemological theory of perception.

Indirect realism

- Indirect realism is the view that the objects of perception are mind-dependent objects which are caused by and represent mind-independent objects.

- The strength of indirect realism is that it fits with the common-sense understanding of our perception that our experience teaches us. We are all familiar with the way our perception can be altered. Illusions, hallucination and perceptual variation suggests that our experience is a mental representation of reality, not reality itself.

The issue that indirect realism leads to scepticism about the existence of mind-independent objects

- Indirect realism claims that we only perceive sense data and that sense data is caused by a mind-independent reality.

- However, if we only have direct awareness of sense data, how do we know that sense data is actually caused by mind-independent objects? How do we know there is an external world at all?

- On this view, for all we know, so-called ‘sense data’ is actually caused by our imagination and there is no external world at all.

- If indirect realism is true, sense data is a ‘veil of perception’ behind which we cannot perceive or know.

- So, indirect realism’s claim that sense data is caused by mind-independent objects is epistemically undermined by its claim that sense data is all we perceive.

- Locke’s argument from the coherence of the various senses.

- When we perceive an apple, we see it, feel it and can taste it. The senses cohere and thus provide evidence for the validity of each other.

- We have multiple different senses – it seems the fact that they all cohere and sense the same things at the same time is good evidence for thinking there really is a mind-independent object. The chance that each sense would mistakenly report the same object at the same time seems very low.

- Locke’s argument from the involuntary nature of experience.

- If there was no mind-independent world, our perceptions would come from our imagination.

- However, we have control over our imagination, but not our perception.

- So, our perceptions must originate from an external world.

- So, we have a basis for rejecting scepticism and claiming that sense data is caused by mind-independent objects.

- Locke’s argument is inductive because he’s arguing there is evidence about the nature of our experience that can be used to infer the nature of its origin.

- However, Locke’s argument is weak because even if it succeeds in showing that our perceptions originate from outside our minds, that wouldn’t show it was caused by a mind-independent reality. It could be caused by another mind or higher being, like the mind of God, as Berkeley suggests.

- Perceptions could simply be caused by an unconscious part of our imagination (e.g. hallucinations) we have no awareness of control over, which produces perceptions for all our senses in a way which coheres with each other.

- So, Locke can’t escape scepticism about the existence of mind-independent reality nor solipsism.

Rusell’s best hypothesis response

- Russell’s response to scepticism is in a stronger position than Locke’s inductive approach.

- The nature of our experience, including its involuntary and coherent nature, are not better evidence for its origin being a real world compared to an evil demon or our own subconscious.

- We cannot prove there is a mind-independent reality, but nor can we prove there isn’t.

- Russell claims such cases justify resorting to an abductive approach of determining which explanation provides the best hypothesis. This means which explanation has the most explanatory power , i.e., provides the most explanation of why our perceptions are the way they are.

- There are two possibilities. Either there is a mind-independent reality causing our perceptions, or there isn’t. Russell gives the example of seeing his cat in his room, but the next time he looks it’s somewhere else.

- If there is no mind-independent reality causing those perceptions then we have no explanation of why those perceptions occurred. We have no explanation of the regularity and order in which our perceptions tend to appear.

- Yet if there is a mind-independent reality causing our perceptions, then we have an explanation of why they are the way they are. The cat’s perceived location changed because it has a mind-independent existence and it moved.

- So, we are justified in believing that our perceptions are caused by a mind-independent external world because it is the best hypothesis.

- Russell’s argument is abductive. Even if it succeeds, it’s not defeating scepticism to a convincing degree. (link to idealism as in a stronger position due to defeating scepticism more convincingly?)

- Furthermore, it doesn’t even succeed. There could be some reason why our unconscious imagination is producing perceptions that are orderly and regular. Perhaps we are living in a hallucinated dream-world that our mind has created to protect us from reality. Our minds could be completely disconnected from reality, if there even is one.

- Or, it could be that another powerful mind which wants to produce deceptively seemingly real perceptions in us is producing our orderly and regular perceptions. If there’s an evil demon and us, there need not be a physical ‘realist’ reality. Or Berkley’s suggestion that God is the origin of our perceptions would also be an equally powerful explanation.

- This possibility would explain the orderliness and regularity of our perceptions just as well as the possibility that a mind-independent reality causes them.

- So, a mind-independent reality causing our perceptions doesn’t have more explanatory power than other possible explanations, so we can’t claim it is the ‘best ‘hypothesis.

Berkeley’s criticism that mind-dependent objects cannot be like (resemble) mind-independent objects.

- IDR claims that sense data represents mind-independent objects.

- Berkeley responds that for something to represent something else, they must be alike.

- Berkeley’s ‘likeness principle’ claims that to justifiably know that two things are alike, requires that we can compare them – to verify that they are in fact alike.

- However, since IDR leads to a veil of perception, we never directly experience mind-independent objects.

- In that case, we can never compare sense data to what it supposedly represents.

- So, we can never justifiably claim that sense data represents mind-independent objects.

- If we perceive, e.g. a table, how do we know that this represents a mind-independent object, if we never directly perceive the mind-independent object?

- So, indirect realism is self-undermining since its claim that we only experience mind-dependent sense data undermines its further claim that this sense data represents mind-independent objects.

- A limitation of Berkeley’s critique is that he assumes representation requires likeness or resemblance.

- Representation seems to be possible without likeness/resemblance.

- For example, the symbols we use in language are arbitrary, meaning they have no resemblance or likeness to the objects they represent.

- The word ‘chair’ is not like a chair but nonetheless can represent it.

- So, mind-dependent objects could still represent mind-independent objects even if they are not like them.

- However, we can defend Berkeley’s conclusion by improving his argument into a stronger form which does not rely on his likeness principle.

- The claim of representation still requires justification.

- How does one know that a mind-dependent object represents a mind-independent object, if a mind-independent object has never been perceived.

- We only know that the word ‘chair’ represents a chair, because we have experienced a chair.

- If we have no experienced mind-independent objects, then we can’t know that our perceptions represent them in any way.

- Even if we accept that ‘likeness’ isn’t’ required for representation, nonetheless for all we know, our perceptions might not even represent the mind-independent world. It could be totally non-representative of our perceptions in any respect.

- So, we just cannot know whether our perceptions represent mind-independent objects.

- So, indirect realism’s claim that the objects of perception are mind-dependent objects does undermine its claim that they represent mind-independent objects and the theory thus leads to scepticism.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is Perception?

Recognizing Environmental Stimuli Through the Five Senses

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Steven Gans, MD is board-certified in psychiatry and is an active supervisor, teacher, and mentor at Massachusetts General Hospital.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/steven-gans-1000-51582b7f23b6462f8713961deb74959f.jpg)

- How It Works

- Improvement Tips

Perception refers to our sensory experience of the world. It is the process of using our senses to become aware of objects, relationships. It is through this experience that we gain information about the environment around us.

Perception relies on the cognitive functions we use to process information, such as utilizing memory to recognize the face of a friend or detect a familiar scent. Through the perception process, we are able to both identify and respond to environmental stimuli.

Perception includes the five senses; touch, sight, sound, smell , and taste . It also includes what is known as proprioception, which is a set of senses that enable us to detect changes in body position and movement.

Many stimuli surround us at any given moment. Perception acts as a filter that allows us to exist within and interpret the world without becoming overwhelmed by this abundance of stimuli.

Types of Perception

The types of perception are often separated by the different senses. This includes visual perception, scent perception, touch perception, sound perception, and taste perception. We perceive our environment using each of these, often simultaneously.

There are also different types of perception in psychology, including:

- Person perception refers to the ability to identify and use social cues about people and relationships.

- Social perception is how we perceive certain societies and can be affected by things such as stereotypes and generalizations.

Another type of perception is selective perception. This involves paying attention to some parts of our environment while ignoring others.

The different types of perception allow us to experience our environment and interact with it in ways that are both appropriate and meaningful.

How Perception Works

Through perception, we become more aware of (and can respond to) our environment. We use perception in communication to identify how our loved ones may feel. We use perception in behavior to decide what we think about individuals and groups.

We are perceiving things continuously, even though we don't typically spend a great deal of time thinking about them. For example, the light that falls on our eye's retinas transforms into a visual image unconsciously and automatically. Subtle changes in pressure against our skin, allowing us to feel objects, also occur without a single thought.

Perception Process

To better understand how we become aware of and respond to stimuli in the world around us, it can be helpful to look at the perception process. This varies somewhat for every sense.

In regard to our sense of sight, the perception process looks like this:

- Environmental stimulus: The world is full of stimuli that can attract attention. Environmental stimulus is everything in the environment that has the potential to be perceived.

- Attended stimulus: The attended stimulus is the specific object in the environment on which our attention is focused.

- Image on the retina: This part of the perception process involves light passing through the cornea and pupil, onto the lens of the eye. The cornea helps focus the light as it enters and the iris controls the size of the pupils to determine how much light to let in. The cornea and lens act together to project an inverted image onto the retina.

- Transduction: The image on the retina is then transformed into electrical signals through a process known as transduction. This allows the visual messages to be transmitted to the brain to be interpreted.

- Neural processing: After transduction, the electrical signals undergo neural processing. The path followed by a particular signal depends on what type of signal it is (i.e. an auditory signal or a visual signal).

- Perception: In this step of the perception process, you perceive the stimulus object in the environment. It is at this point that you become consciously aware of the stimulus.

- Recognition: Perception doesn't just involve becoming consciously aware of the stimuli. It is also necessary for the brain to categorize and interpret what you are sensing. The ability to interpret and give meaning to the object is the next step, known as recognition.

- Action: The action phase of the perception process involves some type of motor activity that occurs in response to the perceived stimulus. This might involve a major action, like running toward a person in distress. It can also involve doing something as subtle as blinking your eyes in response to a puff of dust blowing through the air.

Think of all the things you perceive on a daily basis. At any given moment, you might see familiar objects, feel a person's touch against your skin, smell the aroma of a home-cooked meal, or hear the sound of music playing in your neighbor's apartment. All of these help make up your conscious experience and allow you to interact with the people and objects around you.

Recap of the Perception Process

- Environmental stimulus

- Attended stimulus

- Image on the retina

- Transduction

- Neural processing

- Recognition

Factors Influencing Perception

What makes perception somewhat complex is that we don't all perceive things the same way. One person may perceive a dog jumping on them as a threat, while another person may perceive this action as the pup just being excited to see them.

Our perceptions of people and things are shaped by our prior experiences, our interests, and how carefully we process information. This can cause one person to perceive the exact same person or situation differently than someone else.

Perception can also be affected by our personality. For instance, research has found that four of the Big 5 personality traits —openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, and neuroticism—can impact our perception of organizational justice.

Conversely, our perceptions can also affect our personality. If you perceive that your boss is treating you unfairly, for example, you may show traits related to anger or frustration. If you perceive your spouse to be loving and caring, you may show similar traits in return.

Are Perception and Attitude the Same?

While they are similar, perception and attitude are two different things. Perception is how we interpret the world around us, while our attitude (our emotions, beliefs, and behaviors) can impact these perceptions.

Tips to Improve Perception

If you want to improve your perception skills, there are some things that you can do. Actions you can take that may help you perceive more in the world around you—or at least focus on the things that are important—include:

- Pay attention. Actively notice the world around you, using all your senses. What do you see, hear, taste, smell, or touch? Using your sense of proprioception, notice the movements of your arms and legs, or your changes in body position.

- Make meaning of what you perceive. The recognition stage of the perception process is essential since it allows you to make sense of the world around you. Place objects in meaningful categories, so you can understand and react appropriately.

- Take action. The final step of the perception process involves taking some sort of action in response to your environmental stimulus. This could involve a variety of actions, such as stopping to smell the flower you see on the side of the road, incorporating more of your senses.

Potential Pitfalls of Perception

The perception process does not always go smoothly, and there are a number of things that may interfere with our ability to interpret and respond to our environment. One is having a disorder that impacts perception.

Perceptual disorders are cognitive conditions marked by an impaired ability to perceive objects or concepts. Some disorders that may affect perception include:

- Spatial neglect syndromes, which involve not attending to stimuli on one side of the body

- Prosopagnosia, also called face blindness, is a disorder that makes it difficult to recognize faces

- Aphantasia , a condition characterized by an inability to visualize things in your mind

- Schizophrenia , which is marked by abnormal perceptions of reality

Some of these conditions may be influenced by genetics, while others result from stroke or brain injury.

Perception can also be negatively affected by certain factors. For instance, one study found that when people viewed images of others, they perceived individuals with nasal deformities as having less satisfactory personality traits. So, factors such as this can potentially affect personality perception.

History of Perception

Interest in perception dates back to the time of ancient Greek philosophers who were interested in how people know the world and gain understanding. As psychology emerged as a science separate from philosophy, researchers became interested in understanding how different aspects of perception worked—particularly, the perception of color.

In addition to understanding basic physiological processes, psychologists were also interested in understanding how the mind interprets and organizes these perceptions.

Gestalt psychologists proposed a holistic approach, suggesting that the sum equals more than the sum of its parts. Cognitive psychologists have also worked to understand how motivations and expectations can play a role in the process of perception.

As time progresses, researchers continue to investigate perception on the neural level. They also look at how injury, conditions, and substances might affect perception.

American Psychological Association. Perception .

University of Minnesota. 3.4 Perception . Organizational Behavior .

Jhangiani R, Tarry H. 5.4 Individual differences in person perception . Principles of Social Psychology - 1st International H5P Edition .

Aggarwal A, Nobi K, Mittal A, Rastogi S. Does personality affect the individual's perceptions of organizational justice? The mediating role of organizational politics . Benchmark Int J . 2022;29(3):997-1026. doi:10.1108/BIJ-08-2020-0414

Saylor Academy. Human relations: Perception's effect . Human Relations .

ICFAI Business School. Perception and attitude (ethics) . Personal Effectiveness Management .

King DJ, Hodgekins J, Chouinard PA, Chouinard VA, Sperandio I. A review of abnormalities in the perception of visual illusions in schizophrenia . Psychon Bull Rev . 2017;24(3):734‐751. doi:10.3758/s13423-016-1168-5

van Schijndel O, Tasman AJ, Listschel R. The nose influences visual and personality perception . Facial Plast Surg . 2015;31(05):439-445. doi:10.1055/s-0035-1565009

Goldstein E. Sensation and Perception .

Yantis S. Sensation and Perception .

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- Help & FAQ

Berkeley on the objects of perception

- School of Philosophy, Psychology and Language Sciences

Research output : Chapter in Book/Report/Conference proceeding › Chapter (peer-reviewed) › peer-review

Abstract / Description of output

Keywords / materials (for non-textual outputs).

- Berkeley’s theory of perception

- act-object theory of perception

- relational theory of perception

- adverbialism

- direct realism

- appearances

Access to Document

- 10.1093/oso/9780198755685.003.0004

Fingerprint

- Perception Arts and Humanities 100%

- Object Arts and Humanities 100%

- Theories of perception Arts and Humanities 40%

- Sensation Arts and Humanities 40%

- Response Arts and Humanities 40%

- Quality Arts and Humanities 20%

- Material objects Arts and Humanities 20%

- Dialogue Arts and Humanities 20%

T1 - Berkeley on the objects of perception

AU - Marusic, Jennifer Smalligan

N2 - In the first of the Three Dialogues between Hylas and Philonous, Hylas distinguishes two parts or aspects of every perception, namely a sensation, which is an act of mind, and an object immediately perceived. Hylas concedes that sensations can exist only in a mind, but maintains that the objects immediately perceived have a real existence outside the mind; they are qualities of material objects. This distinction and Philonous’s response to it are the topic of this essay. It considers the implications of this response for understanding Berkeley’s theory of perception and concludes that it supports attributing to Berkeley an object-first theory of perception, according to which it is the special kind of object involved in perception that is philosophically significant.

AB - In the first of the Three Dialogues between Hylas and Philonous, Hylas distinguishes two parts or aspects of every perception, namely a sensation, which is an act of mind, and an object immediately perceived. Hylas concedes that sensations can exist only in a mind, but maintains that the objects immediately perceived have a real existence outside the mind; they are qualities of material objects. This distinction and Philonous’s response to it are the topic of this essay. It considers the implications of this response for understanding Berkeley’s theory of perception and concludes that it supports attributing to Berkeley an object-first theory of perception, according to which it is the special kind of object involved in perception that is philosophically significant.

KW - Berkeley’s theory of perception

KW - act-object theory of perception

KW - relational theory of perception

KW - adverbialism

KW - direct realism

KW - sensation

KW - appearances

KW - mental act

U2 - 10.1093/oso/9780198755685.003.0004

DO - 10.1093/oso/9780198755685.003.0004

M3 - Chapter (peer-reviewed)

SN - 9780198755685

BT - Berkeley's Three Dialogues

A2 - Storrie, Stefan

PB - Oxford University Press

Perceptual objectivity and the limits of perception

- Open access

- Published: 12 April 2018

- Volume 18 , pages 879–892, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Mark Textor 1

7395 Accesses

5 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Common sense takes the physical world to be populated by mind-independent particulars. Why and with what right do we hold this view? Early phenomenologists argue that the common sense view is our natural starting point because we experience objects as mind-independent. While it seems unsurprising that one can perceive an object being red or square, the claim that one can experience an object as mind-independent is controversial. In this paper I will articulate and defend the claim that we can experience mind-independence by mainly drawing on the work of the Gestalt psychologist Karl Duncker who, in turn, built on Husserl’s work. In the development of this claim the notion of a limit – either a maximum or minimum – of perception will play an important role.

Similar content being viewed by others

Twenty years of load theory—where are we now, and where should we go next.

Gillian Murphy, John A. Groeger & Ciara M. Greene

No one knows what attention is

Bernhard Hommel, Craig S. Chapman, … Timothy N. Welsh

Mental machines

David L. Barack

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Early phenomenologists on objective experience

We can introduce our topic by comparing and contrasting two cases Footnote 1 :

You look up at the night sky and I have a visual experience as of many stars twinkling.

You bang your head hard and ‘see stars’.

We could say, without yet putting any explanatory weight on it, that in (A) you have an experience as of a multitude of objects that seem to you to be out there to be encountered. In contrast, in (B) there is a multitude of ‘things’, but they don’t seem to you to be ‘out there’ to be encountered. Let’s call an experience of the kind you have in (A) an ‘objective experience’. An objective experience is not just an experience of something that exists independently of any mental activity but that also (purports to) represents its object(s) as mind-independent.

Several early phenomenologists argued that we have such objective experiences. Here are four examples that will help to anchor our discussion. Footnote 2

First , Paul Linke (1876–1955) wrote with reference to an example given by the Munich phenomenologist Hans Cornelius:

Even the immediately perceived Corneliusian grey spot is given to me as something independent from me whether it is real or not. (Linke 1918, 124; my translation.)

If a surface looks to me as if there is a grey spot on it, it seems to me as if there is a spot ‘out there’, whether there is one or not. I experience the spot, in Linke’s terminology, as ‘extraneous to me’ (“ichfremd”) and ‘extraneous to the act of perception (“aktfremd”) (ibid.).

Second , Roman Ingarden (1893–1970) asked his readers to consider perceiving a red ball:

The ball has – if it exists at all – its own being [Eigensein], and it is for the ball completely accidental that it is perceived by someone. It suffers no changes in virtue of the fact that it is perceived and it is given as such an object that continues to exist in space after we have closed our eyes and no longer perceive it. (Ingarden 1930 , 272-3, my translation and emphasis.)

The ball does not only exist without being perceived, says Ingarden, it is given to the perceiver as something that would persist in space if it were not (no longer) perceived. We experience the ball as something that is disposed to go on existing independently of our experience of it.

Third , the Gestaltpsychologist Karl Duncker (1903–40) called non-epistemic visual perception ‘visual participation’: perceiving is a form of participating in the changes and being of an object. This terminology may strike one as idiosyncratic but we can easily reformulate Duncker’s statements without it. He writes:

Visual participation requires, first of all, the object in which we participate. In the very nature of participation as such lies the independence, the being-in-itself of this object with reference to the act of participation. In other words, participation in an object is not creation of the object. Beyond this, it is characteristic of visual participation (in contradistinction to many another type of participation) that the object remains untouched phenomenally. The tree enters my vision and leaves it; but it does not, for that reason, change qua that tree. The world of objects is experienced as “unverändert durchgehend,” as “persisting unchanged” (“object-constancy”) . The phenomenon of being-in-itself and of persisting unchanged is the objective correlate of the phenomenon of (merely-) participating-in. (Duncker 1947 , 506-507, my emphasis.) Footnote 3

A page later, Duncker sums this up by stating that ‘the objective world is experienced as transcending the temporal and spatial limits of vision, as “ persisting ”.’

Duncker introduces here the concept that will be the key to understand objective experience: the concept of the limit of perception. When we have a perceptual experience as of an object, we are aware in our experience of the limits of our contact with the object and can experience the object ‘transcending’ these limits. We can experience the object as persisting beyond the limits of our perception. The phenomenon of persistence is not restricted to vision (ibid). There is an experiential difference between an auditory experience as of a note gradually softening and finally ceasing on the one hand and an auditory experience as of a note that is played with the same volume gradually becoming less distinct on the other hand. In the second case we experience the note as transcending or persisting beyond the limits of our auditory experience.

Having such an objective experience is independent of the perceiver’s beliefs about the object of their experience. To make the belief-independence of objective experience plausible, think of your perceptual experience of the ball. I tell you that you are participating in a psychological experiment and that you will be undergoing an illusion of seeing a ball rolling away from you because you took hallucination inducing drugs. In fact you do see a ball rolling away from you; I misinformed you: there is no experiment at all. In this situation you will have an experience as of the ball as persisting when it rolls too far away from you to see it. Since your belief that you are undergoing an illusion prevents you from applying your beliefs about the ball, the appearance of persistence must indeed be a matter of how things visually seem to you.

Fourth , when speaking of ‘phenomenal autonomy of persistence’ Duncker refers, like Ingarden before him, to Hedwig Conrad -Martius. Conrad-Martius coined the suggestive term, ‘phenomenal claim to autonomy of being’ (‘phänomenaler Anspruch auf Daseinsautonomie’). Footnote 4 In perceptual experience, objects make a claim on us to be perceived as existing independently of our perceptions. One way they do so is that we experience the limits of our experience of some objects; another way is that we encounter objects that were beyond the limits of our experience. When you walk around the corner it seems to you that you encounter objects that were there all along. Again the experience of a limit of your experience and what lies beyond it is needed to make sense of an experience of encountering an object that was there all along. Conrad -Martius discussed this aspect of objective experience in detail and I will come back to her work in section 6 .

I hope the four descriptions resonate with the reader. If these authors are on the right track, we not only perceive mind-independent objects, sometimes we experience a mind-independent object as being mind-independent: in our experience of it we experience the object’s persistence beyond the limits our perceiving. The main task of this paper will be answer the question what the experience as of an object be like for it to be an experience of an object as well as an experience of its own limits.

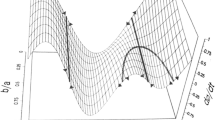

2 Perceptual constancy as a model

Common sense has it that perceiving an object depends on a number of factors: the perceiver is in the right position with respect to it, she is not too far or too close to the object, the illumination is right etc. Evans ( 1980 , 261ff) envisaged that these conditions are collected in a rudimentary theory of perception. The folk theory of perception will contain conditionals such as

If x moves behind y, x will no longer be perceived.

If x moves some distance from a perceiver, it will no longer be perceived.

If the perceiver is distracted, x will no longer be perceived by her.

If the light is too bright (dim), x won’t be perceived.

If some of these conditions are not satisfied, the object will not be perceived. But it would be perceived again, if they were fulfilled. Our grasp of what it is to be mind-independent consists in our knowledge of factors on which our perceptual experience depends and which put limits on it. If we were perceptually aware of the limits of our perception, we could experience our perception of an object depending and transgressing them. This would amount to an experiential awareness of mind-independence.

A well-known phenomenon makes it plausible that we are indeed perceptually aware of factors on which our perceiving of an object depends: perceptual constancies. Let us consider two examples:

Colour constancy: When the illumination changes a white surface still looks white although it seems brighter than before. The colour looks the same; the illumination, a condition for perception, seems to change.

Size constancy: I walk towards a tower. When I approach the tower its visual manifestation expands: it occupies more and more of my visual field. Yet the tower does not appear to change in size: it looks the same size. In turn, it seems to us that the distance between us and the object is decreasing. Footnote 5

Both (A) and (B) are examples of, to use Hopp’s ( 2011 , 149) helpful formulation, ‘a feature appearing differently under different conditions while not appearing to be different’. In the perceptual processes described in (A) and (B) we experience changes in the factors mentioned in the folk theory of perception. In an extended perceiving – my seeing the tower while I approach it – we experience the change of an intervening factor – here, the distance between us and the tower – as well as the constant size of the object to which we attend in perception. Duncker’s description of the perceptual constancy phenomena is therefore spot on:

These facts prove that there are other cases in which a living being (not only man) spontaneously experiences certain phenomena as characteristics, not of things, but of an intervening factor. (Duncker 1947 , 539)

In general, if a perceptual system enables the perceiver to experience changes in relations between the perceiver and the object of perception (the intervening factors) and thereby to experience that the existence and character of her experience depends on the holding of these relations, the perceiver can experience objects as being independent of his actual perceptions. Footnote 6

3 Experiencing mind-independence

We can now use these ideas to make progress with objective experience; the experience of something as mind-independent . In order to experience something in this way, it does not suffice to have an experience of an object as independent of our actual perception. It must perceptually seem to us as if the object persists while our perceiving of it reaches its limit: we need to have an experience as of an object persisting beyond the limits our perceiving . Are there such experiences?

Yes, answered Duncker:

Just as, under certain circumstances, a darkening is experienced as a diminution of illumination rather than as a darkening of the object color, just so a disappearance or a fading is under certain circumstances experienced as the cessation or as a diminution of participation, not as disappearance or fading of the object. (Duncker 1947 , 540)

You can experience a fading either as a change in an intervening factor – a change in the relation to the object is experienced, while the object does not seem to change – or as a change in the object – a gradual ceasing to be – while the intervening factors seem not to change. If one is able to have experiences of the former kind, one will be able to experience the mind-independence of an object. We experience the object as constant through experienced changes of conditions of perceivability – perceptual constancy – and we experience the object as constant through changes beyond a limit of perceivability: mind-independence. In experiences of the second kind something, an object or process, seems to persist, while our perceiving reaches a limit. Such experiences are the basis for our understanding of mind-independence. We get a sense that the object of perception persists beyond the limits of perception. I will come back to the notion of an objective experience in the next section.

Cassam recently rediscovered this idea. He pictures himself walking towards and then past a tree in a quad:

As I keep walking, the tree eventually recedes until at some point I can no longer see it. To experience the tree as receding from view is not to experience it as diminishing in size. Receding is not the same as ceasing to exist, and the experience of an object gradually disappearing from view is not the experience of it gradually ceasing to exist. My experience represents the tree as persisting as my location changes and I move away. (Cassam 2014 , 162)

Cassam uses this observation to address what he and John Campbell call ‘Berkeley’s Puzzle’: how do we acquire concepts of mind-independent objects in the first place? The answer is straightforward, says Cassam: our experience represents some things as mind-independent and we can abstract the concept from there.

In the next sections, we will not assess whether this is the way to solve Berkeley’s puzzle, but what, in general, the case must be for one to have experiences of one’s perceiving of a persisting object ‘diminishing’. If Duncker is on the right track, we can answer this question in part by drawing on what we know about perceptual constancy. Footnote 7 However, we will see that we need to go beyond the concepts necessary to describe perceptual constancies to understand what it is for an object to appear mind-independent.

4 Perceptual anticipations and perceptual maxima and minima

There is an experiential difference between experiencing the perishing or dissolution of an object and experiencing the worsening of one’s perceiving of an object that continues to exist beyond our perceiving. What must experience as of objects be like to allow for this difference?

In the background of the work of authors in the phenomenological tradition is Husserl’s answer to this question. So let’s have a look at it. Husserl’s work on perception is fueled by discoveries about perceptual constancies. For example, colour constancy was explored by a number of psychologists, such as Hering ( 1905 ), Katz ( 1911 ) and Gelb ( 1929 ). They influenced Husserl and he influenced them. Footnote 8 Husserl is concerned with the experiential side of perceptual constancies:

Different acts can perceive the same and yet sense different things. The same tone we hear once spatially near and once far. (Husserl 1913b , 381; my translation) Footnote 9

One can distinguish in an extended perceiving different phases. But throughout its different phases the identity of the object perceived is manifest, although it appears differently in different phases. The question is what links the different phases of such an extended perceiving perceptions together.

Husserl’s answer, in essence, is that it seems to us that we perceive one and the same object through changes of appearance because our experiences are connected to intentions that have conditions of fulfillment. It is tempting to construe these intentions as expectations, that is, beliefs about perceptions one will have at a later point in time. Husserl is adamant that this temptation needs to resisted:

Intention is not expectation; it is not essential to it that it directed towards a future realization. (Husserl 1913a , b II/2, 40; my translation)

Husserl motivates the distinction between intention and expectation with a suggestive example. Footnote 10 You see a carpet with a particular pattern on it, but part of the carpet is hidden by a piece of furniture. In this case ‘we, as it were, feel that the lines and colour patterns continue ‘in the sense’ of what we have seen’ (1913b II/2, 40; my translation.). But we have no expectations about how the pattern will look if we go on perceive the parts hidden from us; we know that we can’t perceive these parts. The intentions under consideration – I will follow the literature in calling them ‘anticipations – differ from expectations, but they can prompt expectations. If we just look at an object in front of us without intending to move closer or around it, we anticipate how other parts of the object look. These anticipations prompt expectations about how the object will appear to us when we start to move in relation to the object of perception. Footnote 11

In the visual case, anticipations are pictorial clues or suggestions ( bildliche Andeutungen ). Take the carpet pattern example: the look of the pattern suggests how its hidden parts look. Similarly, if I see the front of a cubus, some of its parts are seen well others poorly. My current view of the cubus is a good view of its front as well as a poor view of its side. Footnote 12 Yet, the poor view of its side is still a view of its side. The poor view of the side suggests to me a better view of the side under differ conditions. The look of the object from one perspective gives you a clue how it looks from a different perspective: it looks to me such that I can get a better view of its side if I change my position. Footnote 13 Such clues can be confirmed or fulfilled in further perceptions. When one changes one’s position, it seems to one that one is seeing something better that one has already seen poorly.

Perceptual anticipations are, in general, fulfilled in further perceptions and we experience their fulfillment:

The prior intention was directed on the same object as the current one, but what was only unclearly suggested in the first intention is now itself given, or at least more clearly, more richly, obviously more adequately given and thereof we have an immediate awareness, we experience the fulfillment of the suggestion as a peculiar feature of the new perception or, respectively, as a unity creating moment in the succession of acts . (Husserl 1898 , 144. My translation and emphasis.)

Husserl’s description strikes me as spot on. When you see the sides of the book better, you sometimes feel that things look as they should look. This feeling is, in part, negatively characterised as the absence of surprise. Footnote 14 When one has this feeling, one experiences some acts as belonging to one extended perceiving.

Some of our perceptions are tied together by chains of anticipations and experienced fulfillments to an extended perceiving of one object. In such an extended perceiving we experience sameness of object through manifest changes of perception. If the anticipations concern changes of conditions – how the object will look if we move closer or change our position relative to it – and we experience the fulfillment of the anticipations, we experience perceptual constancy. It seems to us that we perceive the same object from a different side, from a better perspective or from closer up. The interplay of anticipation and experienced fulfillment makes it possible to have an experience of manifest sameness of an object perceived through changes of appearance. It is the person-level counterpart to the requirement that the perceptual faculty ‘locates’ some perceived changes in changes of the conditions of perception. Footnote 15

This interplay of anticipation and experienced fulfillment is absent in what Husserl calls ‘adequate perception’. The following example, in which a tone – an objective particular – and the hearing of the tone are contrasted, helps us to see Husserl’s distinction between adequate and inadequate perception:

An emotional experience has no adumbrations. If I turn my gaze on it, I have something absolute, it has no sides that represent themselves once in this, then that way. […] In contrast, the tone of a violin with its objective identity is only given in adumbrations; it has its changing appearances. These differ depending on whether I approach or move away from the violin, whether I am in the concert hall or listen through closed doors etc. No appearance is privileged as the absolute one. … (Husserl 1913b , 81. My translation.)

Emotional experience serves here as a representative example of experience in general. ‘Adumbration’ is Husserl’s term for the appearances of external objects: such objects are given only in adumbrations; objects of this kind adumbrate. Other objects, experiences, that is, mental acts and activities, don’t adumbrate (see Husserl 1913b , 77). Consciousness of one’s present mental acts suggests no further acts of awareness in which anticipations are fulfilled or ‘disappointed’. For this reason, Husserl calls it ‘absolute’. Consider further emotions. Your awareness of your anger does not suggest further acts of awareness to you in which the anger is perceived better. You may have inductive knowledge that your raging anger will abate soon and change into a less violent emotion. But this expectation is not suggested by your present awareness of anger. It is simply general knowledge that you have about your emotional propensities.

For our purposes it is important that we not only anticipate how an object would look if the conditions of perception change, but also anticipate the diminishing and extinction of our perceiving of an object under some changes of these conditions. For if it seems to us that an object can be perceived better if some factors change, it also seems to us that an object can be perceived worse if those factors change differently. The improvement and worsening of our perception has a limit. If, for example, I move closer to an object I will see its colour better, there will be a distance to the object where I see the colour as best as it can be seen for my purposes. If I go even closer, the colour will go out of focus. My perceiving the object contains anticipations to this effect. There is, then, a positive maximum of perception (“Maximalpunkt”) of perceiving that is also a turning point: if you go beyond the point your perception of the object worsens. Footnote 16 There is also a worst point of perception (“Minderungsgrenze”) beyond which we lose perceptual contact with the object. Footnote 17

In his 1907 Husserl spends paragraphs 35 to 38 to resolve the tension between the idea that there are maxima and minima of perception and his view that there is no adequate perception of an object. Yes , there is no adequate perception: we can’t perceive the object as it is because we can only perceive it in adumbrations. But there is still a maximum of perception. For our human constitution and interests determine maxima and minima of perception. By nature perception is a process that cannot result in adequate perception, but there is best perception for beings like us relative to a given interest in the object perceived.

In a perceptual experience of an object, we anticipate how our perceiving of the object will improve as well as how it will worsen with respect to such a limit. Because we anticipate our perceiving of an object to worsen if certain factors change and approximate a minimum or improve until a turning point is reached, there is an experiential difference between an experience as of an object ‘decaying’ and an experience as of an object persisting beyond the limits of perception. If we experience the fulfillment of such ‘negative anticipations’, it seems to us that we cease to perceive a persisting object.

5 A minimal notion of objective experience

The last section suggests that an experience as of an object is an objective experience if, and only if, it involves anticipations about how it can be improved and worsened in relation to a maximum (minimum).

For an experience to be objective it is not necessary that one actually experiences the fulfillment of such anticipations. The anticipations are enough to have an objective experience. Footnote 18 Why? Because of the anticipations, it seems to us that if some conditions of our present perceiving change beyond a limit, our perception of the persisting object will diminish and finally cease. This seeming and not its actual fulfillment makes for perceptual objectivity.

To see the point of this clarification of the notion of an objective experience consider an ‘experience’ in which something seems mind-dependent to you. You have tinnitus. You hear a ringing ‘in your ears’ for an hour. When you are aware of the ringing, you don’t have perceptual anticipations. The auditory experience does not seem to become better or worse in response to changing conditions of perceptions. There is nothing like the experience of fulfillment of positive or negative anticipations. Footnote 19 There is no experiential distinction between your awareness of the ringing becoming fainter while your experience is clear and your experiencing worsening while the ringing persists unchanged. You may have inductive knowledge that the ringing stops after roughly 30 min or that the extent and intensity of it depends on your blood pressure. Such inductive knowledge will enable you to predict how and when the ringing will persist, but such expectations are not perceptual anticipations. It does not seem to you that the ringing will soon stop or get more intense; you have propositional knowledge about changes of your experience, but this is not a case of perceptual objectivity.

The notion of objective experience discussed so far minimal because it leaves open substantial questions about perceptual objectivity. To see this compare it with Siegel following explication of what she calls an experience with perceptual phenomenology:

An experience is perceptual if it seems to one that if one moves one’s sense-organ, one’s perspective on the [odor/thing seen] can thereby change. (Siegel 2006 , 401)

An experience has perceptual phenomenology if experience represents an object as independent from the perceiver, roughly, as out there to be met. If I have an after-image, I have no perspective that seems to change in response change to movements of my sense-organs.

According to Siegel’s necessary condition for objective experience, only experiences which can make us aware of changes in spatial relations between us and the object perceived can be objective. For the movement of our sense-organs changes spatial relations between the object of perception and these organs. Now, there are no doubt anticipations relating to distance and orientation involved in many objective experiences. If sensory experience had no spatial content, we could, for example, not experience some changes in how things seem to us as changes of distance or orientation etc. Footnote 20 But is it part of our concept of experiential objectivity that an experience is only objective if we have anticipations of how the object would appear to us when we change the orientation or distance to it? According to the minimal notion, the answer is NO. An objective experience is an experience that comes with anticipations about improvement and worsening in response to changes of some conditions. But it does not identify these changes as movements of the sense-organs or, more generally, changes in spatial relations. The conditions may be non-spatial.

Here is an example that makes the minimal condition plausible. In colour constancy the colour of an object ‘looks differently’ under different illumination ‘without appearing to be different’ (Hopp). Now, the illumination may change without you moving your sense-organ. To make this vivid consider a situation in which you can only stare at the coloured surface without changing your orientation towards it or even moving your eyes. If your perception of the object contains perceptual anticipations of how the surface colour will look better or worse if more or less light is on it, you have an objective perception of it. Footnote 21 The surface colour seems to persist beyond the limits of your perceiving, although the limits are not approached by moving your sense-organs. Imagine further that you are able change the ambient light without moving any of your sense-organs . If you change the light, some of your anticipations will be satisfied or disappointed; the colour looks as you anticipated it would look. Now, if your anticipations are fulfilled or disappointed in this situation, they are not anticipations about how the perception of the surface will be improved/worsened in response to movements of a sense-organ. For your sense-organs have not moved and, hence, anticipations that involve their movement cannot be fulfilled or disappointed. Yet, the anticipations that you have seem to suffice to make an experiential difference between ceasing to see a constant colour and seeing a colour fading away. You will of course also have perceptual anticipations that concern improvements/worsening of perception in response to movements of your sense-organs. But the example shows that it is not part of our conceptual understanding of an objective experience that such an experience ‘comes with’ anticipations relating to changes in space.

The last point can be strengthened by considering a case in which we cannot have anticipations about improvement/worsening of our perceiving in response to movements of our sense-organs. Imagine that you hear a melody. Husserl brings out that a form of anticipation is involved here:

While the first tone is sounding, the second follows, then the third. Are we not forced to say: when the second tone sounds, I hear it, but no longer the first? Therefore I never really hear the melody, but only individual tones. (Husserl 1928 , 385; my translation)

We hear the melody and in order to do so we must still ‘hear’ the tone that we heard before when it no longer sounds. We hear the tone as the same, although it ‘fades out’ and appears therefore differently. Here we have at least a prima facie case of an objective (auditory) experience in which our anticipations don’t concern movement of sense-organs. We anticipate a different, less clear appearance of the tone as time passes, independently of the movement of any sense-organ. The object of the perception is the same, but our perceiving of it approaches a temporal limit. Whether we indeed have an objective experience in this case should be assessed in the light of further reasons and not simply be ruled out by our notion of objective experience. The minimal notion allows us to assess these cases and is therefore preferable. It does not commit us to hold that the objects of experience need to have a spatial location. For example, it is an open question whether a sound has a spatial location; yet it can be the object of an objective experience.

6 Further limits of perception

Husserl provided the main conceptual tools to understand perceptual constancy. In the previous section we used, following Duncker’s example, these tools to shed light on the notion of an objective experience. But appealing to perceptual anticipations and fulfillments is insufficient to capture the full range of perceptual experiences in which an object seems mind-independent to us. For not only do we have experiences of a persisting object going out of ‘view’, we also have the experience of an unseen object coming into ‘view’. When I turn the corner, I have an experience of encountering the car that was there all along; I don’t have an experience of the car coming into existence. This cannot easily be explained with the same apparatus that was introduced for perceptual constancy. There is no extended perceiving in which intervening factors seem to change, sometimes beyond ‘breaking point’. There is an onset of a perceptual experience in which something seems to be already there.

This kind of experience is discussed in detail by Conrad -Martius:

[I]f we posit the case that we turn around in unfamiliar surroundings, the now newly perceivable objects are not “suddenly” there without any intuitive relation to the previously perceived objects, simply added to them. Rather the in peculiar way empty spatial reality which was previously co-given [mitgegebene] with the sphere of perception fills itself with them. (Conrad -Martius 1916 , 381; my translation)

Even if the scene before my eyes is occupied by a house, the space beyond the house is co-given but not seen. It seems, therefore, that I encounter something that occupied a location that exists independently of my perception when I walk around the house and see the parked car beyond it. In order for us to have such perceptions, we must be aware of space although we don’t see it.

Conrad Martius argues that the co-givenness of something beyond the limits of one’s perceiving is a general feature of how the external world is given to us in perception:

In all cases where I am at all directed into the external world, I am directed with my intuition somewhat over the limits of my sphere of perception. (Conrad Martius 1916 , 381)

How must experience be like to be directed beyond its own limits? Space seems not to end where our perceiving ‘gives out’. We have such experience because the limits of perceiving are manifest to us in perception: Duncker gave a good description of this phenomenon as the limits of perceiving ‘presenting themselves’ to us:

The limit of participation does not, in general, present itself as a sharp contour, but as a peculiar reaching-no-further, of which we frequently do not become conscious until new objects enter. (Duncker 1947 , 511)

When it seems to me that there is white vase in front of me, it also seems to me that there is more to be seen to the left, right and behind the vase, but my perceiving does not reach that far. It is part of the phenomenal character of our experience that it seems to us to have limits and that these limits are not limits of the objects of perception. Footnote 22 It seems that scene before our eyes does not stop where our vision cannot reach. Footnote 23 Again, this is not a belief in unseen regions of space, but a perceptual seeming. In the figure on the previous space, it just looks as if there is part of the figure hidden from view.

With this in mind, we can make sense of the kind of experience that has so far escaped us. We have the experience of a formerly unperceived object coming into view and not of an object coming into existence, because we are aware of the limits of our perceiving and now experience a change in the limits of perception, not in the world we perceive.

There is, then, an analogy between the two cases of object constancy. In both cases, we experience the limits of our faculty. Once we experience some enabling condition for perception changing beyond a limit, we experience a change in the limit of our perceiving such that something which was located in a region beyond our previous limit is now within the new limit, either because the object or we changed location. In general, our awareness of our limits of our perceiving enables us to have experiences of objects as mind-independent.

7 Conclusion

Objective experience is a matter of limits of perception being perceptually manifest in the perception they are limits of. In some experiences, we are aware of an object and how the limits of our receptivity bear on our experience. If this idea is along the right lines, things are given to us as mind-independent before we have acquired the corresponding concept of a mind-independent object. Human and nonhuman animals can therefore both have objective experiences. Hence, they experience the world as containing persisting mind-independent objects. The picture of the world as containing mind-independent particulars with ‘biographies’ is our natural starting point because it is how we experience the world. A revisionary metaphysics that dispenses with objects of this kind beggars belief because it does not sit with our experience of the world.

I borrow the example from Siegel 2006 , 402.

Duncker, Linke and Conrad-Martius will figure later in Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of Perception . In this paper I will focus on the former authors.

According to the editor of Duncker’s paper, the paper was written in the 1930s.

See Conrad -Martius ( 1916 , 413) and Duncker ( 1947 , 509).

Thanks to a referee for helping me to improve these sections.

See also Smith ( 2002 ), 175. Burge ( 2010 , 408) takes perceptual constancies to be capacities whose exercises need not be conscious perceptions in which, for example, an object/feature appear different yet manifestly the same. Because Burge is not concerned with how things seem to the perceiver, but with the states of a subpersonal system, I will set his account aside in this paper. See Campbell ( 2011 , 272-3) for criticism of Burge’s conditions for perceptual objectivity.

Duncker ( 1947 , 541) himself argued that a more satisfactory explanation of phenomenological object-constancy can be given by appealing to a number of facts about voluntary movements. For example, the voluntary act of opening your eyes is not experienced as causing a change in the properties of the objects that come into view. However, such facts seem to be too contingent to yield a general explanation. There is nothing like voluntarily opening your ears. Yet a being that had only auditory experiences could still experience some objects of perception as mind- independent.

Katz took courses with Husserl from 1904 to 1906; see Schuhmann ( 1977 , 80). Husserl read and commented on Hering’s work in 1909, in connection with the dissertation of his student Heinrich Hofmann; see Hofmann ( 1919 ) (see Schuhmann 1977 , 129ff).

Husserl frequently describes perception of an object interpretation of non-intentional sensations or ‘hyletic data’ (see, for example, Husserl 1913b II/1, § 2). Husserl’s dichotomy between data and interpretation gives rise to a number of exegetical and systematic questions (see, for instance, Linke 1928 , § 68). Are hyletic data elements of our sub-personal or personal psychology? How does interpretation work? Are the sensations ‘building stones’ out of which a perception of objects is constructed, as Duncker ( 1947 , 517 Fn.) and Burge ( 2010 , 130) think? Or are they posterior abstractions from a perceiving, as a more charitable reconstruction might hold? For the purposes of this essay we can set these questions aside. Dunker and Linke, for example, follow Husserl in taking perceptual constancies to hold the key to understanding objective representation, yet explicitly reject that objective experiences are constructed or derived from something prior.

On this see Madary ( 2010 ), 148.

See Husserl ( 1913b ) II/2, 40–1.

See Husserl ( 1904 /5), 50. Husserl ( 1904 ), 36–7

See Smith ( 2002 ), 135. Kelly ( 2010 ) goes a substantial step further and argues that one must be driven to get a better ‘perceptual grip’ on the object.

See Mulligan ( 1995 ), 204.

See Madary 2010 , 149.

See Husserl ( 1904 /5) § 14.

See Husserl ( 1907 ), 107.

See Husserl ( 1913b ), II/2, 41. See also Siegel ( 2006 , 401), who stresses that for what she, following Smith ( 2002 ), calls ‘perceptual consciousness’, it is sufficient that something looks as if one’s experience of it will change under certain conditions.

Sometimes rainbows are listed as sensory or mind-dependent objects. See Evans ( 1982 , 263). Our experience of a rainbow comes with perceptual anticipations, but these anticipations will be disappointed. The rainbow looks like something out there to be met in space, but it isn’t.

See Cassam 2014 , 166.

According to Smith, spatial relations are indirectly involved in colour constancy: ‘[T]he varying sensations indicate to us a changing relation to the perceived object to something else in space ’ (Smith 2002 , 175). There is more light over here than over there. So light seems to occur in spatial regions in various quantities and we experience the object to the light that surrounds it . While plausible, this does not help to defend the account of perceptual consciousness in terms of movement of sense-organs. I am grateful to a referee for making me think more about the relations involved in perceptual constancy.

See Soteriou ( 2011 , 193).

See Soteriou ( 2011 , 193) and Richardson ( 2009 , 238).

Burge, T. (2010). Origins of objectivity . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Campbell, J. (2011). Review of Tyler Burge’s origins of objectivity . The Journal of Philosophy, 108 , 269–285.

Article Google Scholar

Cassam, Q. (2014). Representationalism. In Campbell, J. & Cassam, Q. 2014, 158–79.

Conrad Martius, H. (1916). Zur Ontologie und Erscheinungslehre der realen Außenwelt. Verbunden mit einer Kritik positivistischer Theorien. Jahrbuch für Philosophie und phänomenologische Forschung, 3 .

Duncker, K. (1947). Phenomenology and the epistemology of consciousness. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 7 , 505–542.

Evans, G. (1980). ‘Things without the mind’. Reprinted in his Collected Papers (pp. 249–291). Oxford: Oxford University Press 1985.

Google Scholar

Evans, G. (1982). The varieties of reference . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gelb, A. (1929). Die Farbenkonstanz: der Sehdinge. In W. A. von Bethe (Ed.), Handbuch normalen und pathologische Psychologie (pp. 594–678). Berlin: Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

Hering, E. (1905). Die Lehre vom Lichtsinn . Leipzig: Wilhelm Engelmann.

Hofmann, H. (1919). Empfindung und Vorstellung . Berlin: Reuther and Reinhard.

Hopp, W. (2011). Perception. In S. Luft & S. Overgaard (Eds.), The routledge companion to philosophy (pp. 146–158). London: Routledge.

Husserl, E. (1898). Abhandlung über Wahrnehmung von 1898. In his Wahrnehmung und Aufmerksamkeit. Texte aus dem Nachlass (1893–1912). Husserliana 38. Dordrecht: Springer 2004, 123–59.

Husserl, E. (1904/5). Hauptstücke aus der Phänomenologie und Theorie der Erkenntnis. Vorlesungen aus dem Wintersemester 1904/5. In his Wahrnehmung und Aufmerksamkeit. Texte aus dem Nachlass (1893–1912), 3–123.

Husserl, E. 1907. Ding und Raum Vorlesungen 1907. Husserliana 16. Ed. by U. Claesges. Den Haag: Martinu Nijhoff 1973.

Husserl, E. (1913a). Logische Untersuchungen (Second ed.). Tübingen: Max Niemeyer.

Husserl, E. (1913b). Ideen zur reinen Phänomenologie und phänomenologischen Forschung . Jahrbuch für Philosophie und Phänomenologische Forschung 1, 1–323. Transl. 1933 by Boyce Gibson as Ideas: General Introduction to Phenomenology . Reprint London: Routledge 2012.

Husserl, E. (1928). Vorlesungen zur Phänomenologie des inneren Zeitbewusstseins . Ed. by M. Heidegger. Halle: Niemeyer.

Ingarden, R. (1930, 1972). Das Literarische Kunstwerk. (Fourth ed.). Tübingen, Max Niemeyer.

Katz, D. (1911). Die Erscheinungsweise der Farben und ihre Beeinflussung durch die individuelle Entwicklung . Leipzig: Barth.

Kelly, S. (2010). The normative nature of perception. In B. Nanay (Ed.), Perceiving the world (pp. 146–160). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Linke, P. (1928). Grundfragen der Wahrnehmungslehre . München: Ernst Reinhardt.

Madary, M. (2010). Husserl on Perceptual Constancy. European Journal of Philosophy, 20 , 145–165.

Mulligan, K. (1995). Perception. In B. Smith & D. Smith (Eds.), The Cambridge Companion to Husserl (pp. 168–238). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Cambridge.

Richardson, L. (2009). Seeing empty space. European Journal of Philosophy, 18 , 227–243.

Schuhmann, K. (1977). Husserl Chronik: Denk- und Lebensweg Edmund Husserls . Den Haag: Martinus Nijhoff.

Siegel, S. (2006). Direct realism and perceptual consciousness. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 73 , 378–409.

Smith, A. D. (2002). The problem of perception . Cambridge: Mass. Harvard University Press.

Soteriou, M. (2011). The perception of absence, space and time. In J. Roessler, H. Lerman, & N. Eilan (Eds.), Perception, causation, and objectivity (pp. 181–206). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Download references

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Bill Brewer for very helpful written comments and discussion and to Dominic Alford-Duguid and David Jenkins for helpful comments. I presented a forerunner of the paper in a summer seminar in King's College: many thanks to all participants for their feedback. I owe special thanks to two referees who both provided extensive comments which led me to rethink the paper.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Philosophy, King’s College London, WC2R 2LS, London, UK

Mark Textor

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mark Textor .

Rights and permissions