India-Pakistan Relations: Evolution, Challenges & Recent Developments

From Current Affairs Notes for UPSC » Editorials & In-depths » This topic

* Updates: at the bottom

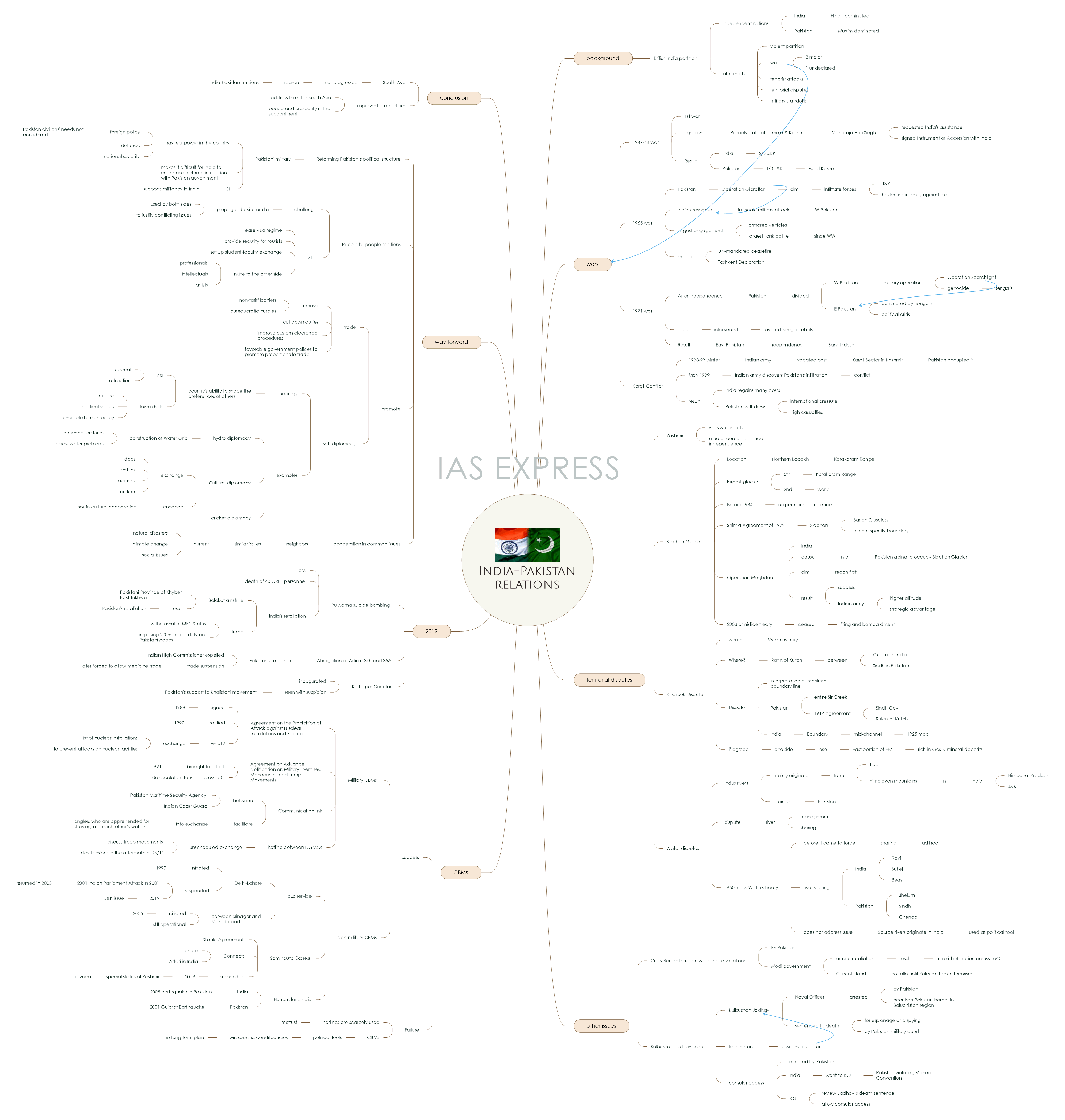

The India-Pakistan relations has often afflicted by cross-border terrorism, ceasefire violations, territorial disputes, etc. In 2019, the bilateral relationship was rocked by several tense events like the Pulwama terror attack, Balakot airstrike, scrapping of Jammu and Kashmir’s special status, etc. Improving bilateral ties is vital for both sides, as it would mean stabilisation of South Asia and the improvement of economies of both the nations. However, the political will to mend the relationship in the current juncture seems to be absent on both sides.

This topic of “India-Pakistan Relations: Evolution, Challenges & Recent Developments” is important from the perspective of the UPSC IAS Examination , which falls under General Studies Portion.

Background:

- Following the partition of British India, two separate nations, India (dominated by Hindus) and Pakistan (dominated by Muslims) was formed.

- Despite the establishment of diplomatic relations after their independence, the immediate violent partition, wars, terrorist attacks and numerous territorial disputes overshadowed the relationship.

- Since independence in 1947, both countries have fought three major wars, one undeclared war and have been involved in armed skirmishes and military standoffs.

- The dispute over Kashmir is the main centre-point of all these conflicts except for the Indo-Pakistan war of 1971, which resulted in the secession of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh ).

- Several efforts were made to improve the bilateral ties, which were successful in de-escalating tensions to a certain extent.

- However, these efforts were hampered by frequent terrorist attacks and ceasefire violations.

Express Learning Programme (ELP)

- Optional Notes

- Study Hacks

- Prelims Sureshots (Repeated Topic Compilations)

- Current Affairs (Newsbits, Editorials & In-depths)

- Ancient Indian History

- Medieval Indian History

- Modern Indian History

- Post-Independence Indian History

- World History

- Art & Culture

- Geography (World & Indian)

- Indian Society & Social Justice

- Indian Polity

- International Relations

- Indian Economy

- Environment

- Agriculture

- Internal Security

- Disasters & its Management

- General Science – Biology

- General Studies (GS) 4 – Ethics

- Syllabus-wise learning

- Political Science

- Anthropology

- Public Administration

SIGN UP NOW

What are the wars and conflicts that were fought between India and Pakistan?

Indo-Pakistani War of 1947-48

- It was the first of the four Indo-Pakistan Wars fought between the two newly independent nations.

- This war was fought between the two nations over the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir that was under the control of Maharaja Hari Singh.

- Fearing a revolt within the state and invasion from Pakistan, Maharaja Hari Singh made a plea to India for assistance. Assistance was offered by the Indian government in return to his signing an Instrument of Accession to India.

- The war resulted in India securing two-thirds of Kashmir, including Kashmir Valley, Jammu and Ladakh .

- Pakistan controls roughly one-third of the state, referring to it as Azad (free) Kashmir.

Indo-Pakistan War of 1965:

- The Indo-Pakistan War of 1965 initiated following the culmination of skirmishes that took place since April 1965.

- Pakistan’s Operation Gibraltar was launched to infiltrate forces into Jammu and Kashmir to hasten insurgency against India.

- India retaliated by launching a full-scale military attack on West Pakistan.

- This war resulted in thousands of causalities on both sides and witnessed the largest engagement of armoured vehicles and the largest tank battle since World War II.

- The war ended after an UN-mandated ceasefire was declared following diplomatic intervention by the USSR and the US, and the subsequent issuance of the Tashkent Declaration.

Indo-Pakistan War 1971:

- Since independence, Pakistan was geopolitically divided into two major regions, West Pakistan and East Pakistan, which is dominated by Bengali people.

- Following the launch of Pakistan’s military operation (Operation Searchlight), a genocide on Bengalis in December 1971 and the political crisis in East Pakistan, the situation went out of control in East Pakistan.

- India intervened in favour of the rebelling Bengalis population.

- Indian army invaded East Pakistan from three sides and the Indian Navy imposed a naval blockade of East Pakistan, leading to the destruction of a significant portion of Pakistan’s naval strength.

- After the surrender of Pakistani forces, East Pakistan became an independent nation of Bangladesh.

Kargil Conflict:

- During the winter of 1998-99, the Indian army vacated its posts at high peaks in Kargil Sector in Kashmir as it used to do every year.

- Pakistan Army made use of this opportunity to move across the line of control and occupied the vacant posts.

- The Indian army discovered this in May 1999, when the snow thawed.

- This led to intense fighting between Indian and Pakistani forces.

- Backed by the Indian Air Force, the Indian Army regained many of the posts that Pakistan had earlier occupied.

- Pakistan later withdrew from the remaining portion because of the international pressure and high causalities.

Prelims Sureshots – Most Probable Topics for UPSC Prelims

A Compilation of the Most Probable Topics for UPSC Prelims, including Schemes, Freedom Fighters, Judgments, Acts, National Parks, Government Agencies, Space Missions, and more. Get a guaranteed 120+ marks!

What are the territorial disputes between India and Pakistan?

- Due to political differences between the two countries, the territorial claim of Kashmir has been the subject of wars in 1947, 1965 and a limited conflict in 1999 and frequent ceasefire violations and promotion of rebellion within the Indian side of Jammu and Kashmir.

- The then princely state remains an area of contention and is divided between the two countries by the Line of Control (LoC), which demarcates the ceasefire line agreed post-1947 conflict.

Siachen Glacier:

- Siachen Glacier is located in Northern Ladakh in the Karakoram Range.

- It is the 5 th largest glacier in Karakoram Range and the 2 nd largest glacier in the world.

- Most of the Siachen Glacier is disputed between India and Pakistan.

- Before 1984, neither of the two countries had any permanent presence on the glacier.

- Under the Shimla Agreement of 1972, the Siachen was called a barren and useless.

- This Agreement also did not specify the boundary between India and Pakistan.

- When India got intelligence that Pakistan was going occupy Siachen Glacier, it launched Operation Meghdoot to reach the glacier first.

- Following the success of Operation Meghdoot, the Indian Army obtained the area at a higher altitude and Pakistan army getting a much lower altitude.

- Thus, India has a strategic advantage in this region.

- Following the 2003 armistice treaty between the two countries, firing and bombardment have ceased in this area, though both the sides have stationed their armies in the region.

Sir Creek Dispute:

- Sir Creek is a 96 km estuary in the Rann of Kutch.

- Rann of Kutch lies between Gujarat (India) and Sindh (Pakistan).

- The dispute lies in the interpretation of the maritime boundary line between the two countries.

- Pakistan claims the entire Sir Creek in accordance with a 1914 agreement that was signed between the Government of Sindh and Rulers of Kutch.

- India, on the other hand, claims that the boundary lies mid-channel as per a 1925 map.

- If one country agrees to the other’s position, the former will lose a vast amount of Exclusive Economic Zone that is rich with gas and mineral deposits.

Water disputes:

- The waters of the Indus Rivers begin mainly in Tibet and the Himalayan Mountains in the states of Himachal Pradesh and Jammu and Kashmir (Indian side).

- They flow through the states of Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan, Sindh etc., before draining into the Arabian Sea through the Pakistani side.

- The partition led to conflict over waters of the Indus basin as it was in such a way that the source rivers of the Indus Basin were in India.

- Both sides were at odds over how to manage and share these rivers

- Until the signing of the Indus Waters Treaty in 1960, the arrangement to share east and west-flowing rivers were ad hoc.

- The Indus Waters Treaty is the water distribution treaty signed between India and Pakistan, brokered by World Bank (then the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development).

- According to the treaty, three rivers, Ravi, Sutlej and Beas were given to India for exclusive use and the other three rivers, Sindh, Jhelum and Chenab were given to Pakistan.

- This treaty failed to address the dispute since source rivers of Indus Basin were in India, having the potential to create drought and famines in Pakistan.

- Last year, Modi Government had stated that India would no longer allow its share of river waters to flow into Pakistan in response to the Pulwama terror attack.

- According to the 1960 Indus Waters Treaty, India can exploit rivers under its control without disturbing the flow or quantum.

- India plans to divert its three rivers to the Yamuna.

What are the other areas of contentions?

Cross-Border terrorism and ceasefire violations:

- Cross-border terrorism has been an issue since independence.

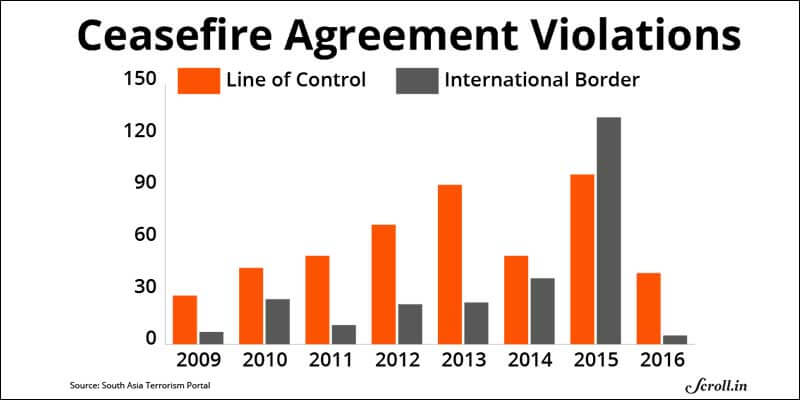

- Despite the 2003 Ceasefire Agreement post-Kargil Conflict, there have been regular ceasefire violations from the Pakistan side of the border since 2009, leading to the death and injury of security forces and civilians on both sides.

- The Modi Government’s massive armed retaliation to Pakistan’s ceasefire violations led to a rise in the number of infiltrations of terrorists from across the LoC.

- Subsequent incidents of 2016 Pathankot attack and Uri attack resulted in the ceasing of any effort to undertake bilateral talks between the two countries, with Indian Prime Minister declaring that “talks and terrorism cannot go hand in hand”.

- This was followed by surgical strikes by Indian Army across the LoC to target the terror infrastructure in PoK.

- India’s current stand is that it will not undertake talks until Pakistan tackle cross-border terrorism.

- Pakistan, in contrast, is ready for talks but with the inclusion of Kashmir issue.

Kulbushan Jadhav case:

- Kulbushan Jadhav, a retired Naval Officer was arrested near the Iran-Pakistan border in Baluchistan region by Pakistan.

- Pakistan accused him of espionage and spying. He was sentenced to death by Pakistan’s military court.

- India states that Jadhav was a retired Naval Officer who was in Iran on a business trip and was falsely framed by Pakistan.

- India, for many times, demanded consular access of Jadhav, which was rejected by Pakistan, citing national security.

- This led to India approaching International Court of Justice (ICJ) and stating that Pakistan was violating Vienna Convention by denying Consular Access.

- The ICJ asked Pakistan to review Jadhav’s death sentence and allow consular access.

Were the past Confidence Building Measures between India and Pakistan successful?

- Since the Partition, India and Pakistan have signed many agreements to generate confidence and reduce tensions.

- Perhaps the most notable among them are Liaquat- Nehru Pact (1951), Indus Waters Treaty (1960), Tashkent Agreement (1966), Rann of Kutch Agreement (1969), Shimla Accord (1972), Salal Dam Agreement (1978), and the establishment of the Joint Commission.

- Except for the Joint Commission, all the others were the products of either a crisis or a war that necessitated a logical end to the preceding developments.

- Though CBMs are efficient tools to improve inter-state relations, trust between the two sides is vital for its success.

- CBMs are difficult to establish but easy to disrupt and abandon.

- Some continue to be successful while others are abandoned.

Major Achievements:

Some of the confidence-building measures taken to improve Indo-Pakistan relations are as follows:

Military CBMs:

- Agreement on the Prohibition of Attack against Nuclear Installations and Facilities was signed in 1988 and ratified in 1990. The first exchange took place on January 1, 1992. As per the Agreement, India and Pakistan exchange the list of their nuclear installations to prevent attacking each other’s atomic facilities. This practise has been followed to date.

- Agreement on Advance Notification on Military Exercises, Manoeuvres and Troop Movements were brought into effect in 1991. This agreement played a crucial role in deescalating the tensions on both the sides of the LoC.

- A communication link between Pakistan Maritime Security Agency and the Indian Coast Guard was established in 2005 to facilitate the early exchange of information regarding anglers who are apprehended for straying into each other’s waters.

- A hotline between Directors-General of Military Operations (DGMOs) of both the countries have been in effect since 1965 and was used in an unscheduled exchange to discuss troop movements and allay tensions in the aftermath of the 26/11 attacks.

Non-military CBMs:

Most of these CBMs focused on improving people-to-people interaction. Some of the significant ones that more or less withstood the test of times are as follows:

- Delhi-Lahore Bus Service was initiated in 1999. It was suspended in the aftermath of the 2001 Indian Parliament Attack. The bus service was later resumed in 2003 when bilateral relations had improved. This service was recently suspended in 2019 in the aftermath of the abrogation of Article 370 and 35A of the Indian Constitution .

- Samjhauta Express that was launched following the signing of the Shimla Agreement connects Pakistani city of Lahore and the Indian town of Attari. It had been suspended frequently, but due to negotiations, it was restarted. In 2019, it was suspended after the revocation of the special status of Kashmir.

- Weekly Bus Service between Srinagar and Muzaffarabad was initiated in 2005. It has withstood the test of times and still operational.

- India extended humanitarian aid to Pakistan in the aftermath of the 2005 earthquake. Pakistan too had earlier provided relief in the aftermath 2001 Gujarat Earthquake.

Failures in the CBM process:

- Although there are hotlines connecting both military and political leaders in both countries, they have been scarcely used when required the most. The absence of communications has led to suspicions and accusations of misinformation.

- There is a disproportionate emphasis on military CBMs and inadequate recognition of several momentous non-military CBMs.

- Governments of both sides often use CBMs as political tools to win over specific constituencies, which can be very damaging in the long-run. Public conciliatory statements, which are meant to be CBMs, can have the opposite effect if they are insincere.

What was the progress made in 2019?

- The year 2019 has in many ways, set the tone, tenor and tempo of how 2020 will pan out between India and Pakistan.

- Early last year, the Pulwama suicide bombing carried out by the Pakistani terrorist group Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM) led to the death of 40 CRPF personnel. This was the starting point of the steep decline in relations.

- Within a few days after the incident, India’s fighter jets targeted a JeM terrorist camp, not in Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (PoK), but in Balakot in the Pakistani Province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. This led to retaliation from Pakistan.

- This incident led to a paradigm shift to the traditional India-Pakistan tensions.

- Later that year, the amendment and hollowing out of Article 370 , scrapping of Article 35A, the bifurcation of the erstwhile Jammu and Kashmir into two Union Territories stunned Pakistan.

- This move effectively killed whatever remained of the bilateral ties post-Balakot airstrike.

- Pakistan responded by expelling the Indian High Commissioner and suspending all trade between the two countries.

- Trade had already fallen steeply after India withdrew Pakistan’s Most Favoured Nation (MFN) status and imposed a 200% import duty on Pakistani goods earlier that year post-Pulwama.

- However, within days, Pakistan was forced to allow the import of medicines from Indian to provide relief to its patients who were affected due to its suspension of bilateral trade with India.

- Amid the post Article 370 breakdown, Pakistan went ahead with the Kartarpur Corridor. Even this move is seen with mistrust by many due to Pakistan’s support to the Khalistani movement.

- Furthermore, any progress in the diplomatic ties in the political front is going to be difficult because of Pakistan military’s dominance in the country’s foreign policy. Any progress made has often led to a terror attack or ceasefire violation.

- In the current situation, the prospects for meaningful engagement between the two nations remain bleak and the best that can happen is that the diplomatic relations are fully restored, trade is opened up and easing of travel between the two nations.

What can be the way forward?

Reforming Pakistan’s political structure:

- Despite the democratic elections in Pakistan, the military wields the real power in the country. This holds true especially on matters of defence, national security and foreign policy.

- Pakistan’s military is the most dominant national political institution, the primary decision-maker and the chief overseer of Pakistan’s growing nuclear arsenal.

- People’s needs on the aspects of health, employment and education are not prioritised while the military decides on its foreign policies with other nations, leading to the Pakistani economy feeling the brunt of the radical decisions by the military.

- Pakistan’s Inter-Service Intelligence (ISI), consisting for personnel from Pakistan Armed Forces, is often accused of supporting and training separatist militant groups operating in Kashmir and other parts of the country like North-East India .

- This makes it highly difficult for India to undertake diplomatic relations with Pakistani government since it is not the decision-maker in the country.

- Thus, a strong political reform in Pakistan, the one that focuses on the welfare of the Pakistani nationals is vital to improving its relations with India.

People-to-people relations:

- Propaganda is currently being used by both sides through the media to justify each other’s stand on conflicting issues.

- This is creating misconception, hatred and stereotyping among the people of both countries.

- This method is also used for political gains of both nations, with least consideration towards people’s welfare and the need for peace.

- Steps must be taken to facilitate travel between the two countries, ease up visa regimes, provide security for tourists, set up student and faculty exchanges, and invite professionals, intellectuals and artists to events to promote the bilateral ties.

Promote trade:

Steps that can be undertaken to improve bilateral trade include:

- Remove non-tariff barriers and bureaucratic hurdles that are currently impeding trade.

- Cut down duties

- Improve customs clearance procedures

- Proportionate trade is beneficial for both sides and is possible through the right government policies.

Promoting soft diplomacy:

It is the ability of the country to shape the preferences of others through appeal and attraction towards its political values, culture and favourable foreign policy. Measures that can be taken to promote soft diplomacy include:

- Use of Indus Waters Treaty to promote hydro diplomacy. Both nations can come together to construct Water Grid between their territories to address the water problems in the region.

- Cultural diplomacy can be used through the exchange of ideas, values, traditions and other cultural aspects to strengthen bilateral ties, enhance the socio-cultural cooperation and promote the individual national interest.

- Promotion of Cricket diplomacy i.e., the use of cricket as a diplomatic tool to overcome differences between the two countries.

To a certain extent, soft diplomacy improved the people-to-people relations between the two countries and eased the tensions on both sides.

Cooperation to address common issues:

- Being neighbours, both India and Pakistan face similar problems that are currently plaguing the region.

- For instance, recently, Pakistan has sought to import chemicals from India to fight the imminent locust attack.

- India too is a victim to locust attack.

- Thus, such similar problems like climate change and natural disasters can be dealt with through cooperation from both sides.

- This can significantly improve the bilateral relations between India and Pakistan.

- Social issues like child marriage, illiteracy, disease, discrimination, exploitation, unemployment and poverty are also an issue of common importance for both the nations, which the countries can use to improve their relations and coexist with each other.

Conclusion:

South Asia has not yet progressed despite it having the potential to ensure fast-paced economic growth and development. This is mostly because of the differences and tensions between India and Pakistan. Improved India-Pakistan relations can ensure the addressing of any threat the subcontinent may face in the future. Cooperation and coexistence through trust can ensure an establishment of peaceful and prosperous South Asia.

Practice Question

Terrorism and decisive military response have plagued the India-Pakistan bilateral ties. What can be done to improve diplomatic relations? (250 words)

GET MONTHLY COMPILATIONS

Related Posts

China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC): Why is India concerned?

Pakistan’s National Security Policy

Pakistan’s internal crisis: Implications and the way forward

Indus Waters Treaty: All you need to know

There was a problem reporting this post.

Block Member?

Please confirm you want to block this member.

You will no longer be able to:

- See blocked member's posts

- Mention this member in posts

Please allow a few minutes for this process to complete.

Review: Why the India-Pakistan Rivalry Endures

Create an FP account to save articles to read later and in the FP mobile app.

ALREADY AN FP SUBSCRIBER? LOGIN

World Brief

- Editors’ Picks

- Africa Brief

China Brief

- Latin America Brief

South Asia Brief

Situation report.

- Flash Points

- War in Ukraine

- Israel and Hamas

- U.S.-China competition

- Biden's foreign policy

- Trade and economics

- Artificial intelligence

- Asia & the Pacific

- Middle East & Africa

Reimagining Globalization

Fareed zakaria on an age of revolutions, ones and tooze, foreign policy live.

Spring 2024 Issue

Print Archive

FP Analytics

- In-depth Special Reports

- Issue Briefs

- Power Maps and Interactive Microsites

- FP Simulations & PeaceGames

- Graphics Database

From Resistance to Resilience

The atlantic & pacific forum, redefining multilateralism, principles of humanity under pressure, fp global health forum 2024.

By submitting your email, you agree to the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use and to receive email correspondence from us. You may opt out at any time.

Your guide to the most important world stories of the day

Essential analysis of the stories shaping geopolitics on the continent

The latest news, analysis, and data from the country each week

Weekly update on what’s driving U.S. national security policy

Evening roundup with our editors’ favorite stories of the day

One-stop digest of politics, economics, and culture

Weekly update on developments in India and its neighbors

A curated selection of our very best long reads

Why the India-Pakistan Rivalry Endures

A recent book emphasizes domestic politics in the conflict but doesn’t account for the depth of the impasse..

- Geopolitics

- Sumit Ganguly

India and Pakistan have mostly been at odds since 1947, when both emerged as independent countries after decades of British rule. The two states fought a war in that year—and three more in the years since, in 1965, 1971, and 1999. (Their fleeting cooperation was largely confined to the 1950s.) The most recent crisis between New Delhi and Islamabad took place three years ago, following a terrorist attack in Indian-administered Kashmir; India followed with an aerial attack in Pakistan, leading to retaliation from Islamabad.

As that crisis underscored, the India-Pakistan relationship has deteriorated significantly in the last decade, especially following the election of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2014. This decline stems in part from Pakistan’s continued dalliance with anti-Indian terrorist organizations, an unstated component of its national security strategy . In response, the Modi government has adopted an unyielding stance. India’s decision in 2019 to unilaterally rescind the special autonomous status of the disputed state of Jammu and Kashmir further undermined bilateral ties. Any recent progress in the relationship—such as India’s humanitarian gestures in the wake of devastating floods in Pakistan this year—has been largely cosmetic.

Complex Rivalry: The Dynamics of India-Pakistan Conflict , Surinder Mohan, University of Michigan Press, 420 pp., $39.95, October 2022

A new book by Indian scholar Surinder Mohan takes a multilayered approach to the India-Pakistan relationship, eschewing well-worn explanations—including those based in the tradition of realism, which emphasizes material power. Complex Rivalry: The Dynamics of India-Pakistan Conflict argues that the enmity between the two countries traces to a unique jumble of factors, beginning with the shock of the Partition of India; tensions have been further intensified by ideology, a shared border, and disputed territory. However, the book has a few shortcomings that limit its insights into the future of the India-Pakistan rivalry, most notably its failure to directly acknowledge the primacy of the Pakistani military establishment in the country’s politics.

Mohan acknowledges that India and Pakistan each embraced power politics, accepting the utility of force—or the threat of force—to settle their bilateral relations as independent states. However, unlike realist scholars, who focus almost exclusively on power asymmetries, he argues that domestic politics also contributed to the start of the rivalry—and have sustained it. The terrible fallout of Partition, with more than 1 million people dead and 10 million displaced, became closely intertwined with the domestic politics of both India and Pakistan. Because the status of Kashmir remains unreconciled for both parties, political leaders fixated on the territorial dispute.

Early on, the Pakistani leadership’s obsession with the Kashmir dispute led it to draw in the United States to balance India’s power. In 1954, the Eisenhower administration gave in to these entreaties and signed a defense pact with Pakistan. Emboldened by these new military capabilities acquired from the United States, Pakistan initiated a war with India in 1965. During these years, the dispute over Kashmir and the involvement of great powers deepened the rivalry—which became more salient in domestic politics, culminating in another war in 1971. Here, Mohan doesn’t offer much new analysis, covering familiar ground for regional specialists.

Mohan’s discussions of the role of both internal and external shocks in sustaining the India-Pakistan rivalry are more illuminating. After the 1971 war, India’s preponderant military role in the subcontinent contributed to ragged regional stability: No Pakistani regime considered provoking India for nearly two decades, largely due to asymmetries of power. However, Mohan argues that India’s attempts to meddle in Kashmir’s internal politics contributed to an insurgency in Indian-administered Kashmir in 1989—a shock that gave Pakistan a window of opportunity. As Islamabad entered the fray through covert backing for the rebels, the insurgency was transformed from a domestic uprising into a civil war with religious inspiration and external support.

From this perspective, Pakistan’s ongoing political and economic crisis might have some effect on the rivalry with India. In April, the ouster of Prime Minister Imran Khan threw the country’s politics into turmoil, making a renewal of dialogue between New Delhi and Islamabad even more unlikely. The country’s opposition leader seems intent on harassing—and distracting—the civilian government through public rallies and street protests. There is little reason to believe that the appointment of Pakistan’s new Army chief, former spymaster Asim Munir, will pacify the fraught relationship. Meanwhile, the economy is buckling under the weight of heavy debt and massive inflation.

Is Imran Khan Pakistan’s Comeback Kid?

Foreign Policy talked to the former prime minister about the recent attempt on his life, relations with Washington, and how he’d make Pakistan great.

However, Mohan does not offer a fresh approach to the India-Pakistan rivalry or to reducing tensions that accounts for the fraught domestic politics in both states at the moment. He draws on theoretical literature to outline a possible pathway for the countries to end their dispute, but his suggestions are diffuse and somewhat didactic. Mohan suggests that as a first step, Indian and Pakistani elites could take risks in promoting de-escalation—moves that could lead to an eventual end to the rivalry. But he fails to spell out what incentives either side has to undertake such risky ventures or what those risky ventures might look like in the first place.

Finally, the principal drawback of Complex Rivalry is that it fails to forthrightly confront two related issues that still play a crucial role in India-Pakistan tensions. Mohan alludes to the appropriate literature—most notably, Maya Tudor’s scholarship on the subject—but he does not adequately address the initial weakness of Pakistan’s civilian political institutions. Their anemic features and inability to maintain order from the outset led to the second issue: the authoritarian bureaucratic-military nexus that came to the fore in the absence of robust civilian institutions.

Forged in the late 1950s, this alliance between the military and an elitist bureaucracy has remained a constant in Pakistan’s domestic politics. Even after the Pakistan Army was morally discredited by its egregious role in the 1971 war—a genocidal campaign against Bengali dissidents in East Pakistan—it managed to regroup and restore its central role in domestic politics. More to the point, Pakistan’s military has consistently exaggerated the security threat from India, largely to bolster its own interests. The military has aggrandized so much power that it has become a first among equals within Pakistan’s domestic political sphere.

This military establishment now confronts an intransigent adversary in New Delhi. Modi, an unabashed exponent of Hindu nationalism, sees the conflict through the prism of his own domestic politics: An unyielding stance toward Pakistan plays well with key constituencies at home. Perhaps more than ever, the two sides face a near impasse. Furthermore, the continuing political uncertainty in Pakistan provides Modi a ready-made excuse to avoid taking the initiative to improve ties. As the politics of Hindu nationalism become entrenched in Modi’s India, the possibilities of any meaningful dialogue look increasingly like a mirage.

Books are independently selected by FP editors. FP earns an affiliate commission on anything purchased through links to Amazon.com on this page.

Sumit Ganguly is a columnist at Foreign Policy and visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. He is a distinguished professor of political science and the Rabindranath Tagore chair in Indian cultures and civilizations at Indiana University Bloomington.

Join the Conversation

Commenting on this and other recent articles is just one benefit of a Foreign Policy subscription.

Already a subscriber? Log In .

Subscribe Subscribe

View Comments

Join the conversation on this and other recent Foreign Policy articles when you subscribe now.

Not your account? Log out

Please follow our comment guidelines , stay on topic, and be civil, courteous, and respectful of others’ beliefs.

Change your username:

I agree to abide by FP’s comment guidelines . (Required)

Confirm your username to get started.

The default username below has been generated using the first name and last initial on your FP subscriber account. Usernames may be updated at any time and must not contain inappropriate or offensive language.

Sign up for Editors' Picks

A curated selection of fp’s must-read stories..

You’re on the list! More ways to stay updated on global news:

Biden Proposes New Asylum System Policies

Biden draws a red(ish) line on israel, what does america want in ukraine, uncle sam wants you to join the mining industry, germany is now spying on its own top spy, editors’ picks.

- 1 No, This Is Not a Cold War—Yet

- 2 Taiwan Wants Suicide Drones to Deter China

- 3 Why Are More Chinese Migrants Arriving at the U.S. Southern Border?

- 4 What Does America Want in Ukraine?

- 5 Saudi Arabia Is on the Way to Becoming the Next Egypt

- 6 Xi Believes China Can Win a Scientific Revolution

Biden Proposes New Asylum Eligibility Timeline at U.S.-Mexico Border

Israel-hamas war: biden pauses some military aid to israel over rafah plans, u.s. ukraine policy: what's biden's endgame, u.s. critical mineral worker shortage hurts competition with china, more from foreign policy, nobody is competing with the u.s. to begin with.

Conflicts with China and Russia are about local issues that Washington can’t win anyway.

The Very Real Limits of the Russia-China ‘No Limits’ Partnership

Intense military cooperation between Moscow and Beijing is a problem for the West. Their bilateral trade is not.

What Do Russians Really Think About Putin’s War?

Polling has gotten harder as autocracy has tightened.

Can Xi Win Back Europe?

The Chinese leader’s visit follows weeks of escalating tensions between China and the continent.

Saudi Arabia Is on the Way to Becoming the Next Egypt

Taiwan wants suicide drones to deter china, no, this is not a cold war—yet, why are more chinese migrants arriving at the u.s. southern border.

Sign up for World Brief

FP’s flagship evening newsletter guiding you through the most important world stories of the day, written by Alexandra Sharp . Delivered weekdays.

- IAS Preparation

- UPSC Preparation Strategy

- India Pakistan Relations

India - Pakistan Relations

India pakistan relations upsc.

In this article, you can read about several issues concerned with India’s relations with its neighbour Pakistan.

The India Pakistan relations are one of the most complex associations that India shares with any of its neighbouring countries. In spite of the many contentious issues, India and Pakistan have made major strides in reducing the “trust deficit” over the past few years.

India desires peaceful, friendly and cooperative relations with Pakistan, which requires an environment free from violence and terror. The two countries share linguistic, cultural, geographical and economic links but due to political and historical reasons, the two share a complex relation.

India – Pakistan Relations [UPSC Notes]:- Download PDF Here

From the IAS Exam perspective, the relation between India and Pakistan is an important topic and aspirants must be aware of the latest bilateral development between the two countries.

India-Pakistan Relations – Latest Developments

In February 2021, India and Pakistan issued a joint statement for the first time in years, announcing that they would observe the 2003 ceasefire along the Line of Control (LoC). The countries have agreed to a strict observance of all agreements, understandings and cease firing along the Line of Control (LoC) and all other sectors with effect from the midnight of February 24-25, 2021. In the interest of achieving mutually beneficial and sustainable peace along the borders, the two Directors General of Military Operations agreed to address each other’s core issues and concerns which have the propensity to disturb peace and lead to violence.

- In the latest bilateral brief between India and Pakistan (February 2020) India stands by its “Neighbourhood First Policy” and desires normal relations with Pakistan in an environment which is free of terror and violence.

- In 2019, Article 370 of India’s Constitution, was scrapped off, which gave a special status to Jammu and Kashmir. Following which, the bilateral relations faced a severe blow. It was followed by Pakistan expelling the Indian Hgh Commissioner in Islamabad and suspension of air and land links, and trade and railway services.

- There was no forward movement in bilateral ties in 2020 due to the mistrust between the two countries, especially on the Kashmir issue.

- India, on February 15, 2019, withdrew Most Favoured Nation Status to Pakistan

Aspirants can go through the details regarding India Pakistan Cease Fire on the video provided below-

A Brief Background of India-Pakistan Relations

Ever since India’s independence and the partition of the two countries, India and Pakistan have had sour relations. Discussed below is a brief timeline of the relations between the two countries:

- The Composite Dialogue between India and Pakistan from 2004 to 2008 addressed all outstanding issues. It had completed four rounds and the fifth round was in progress when it was paused in the wake of the Mumbai terrorist attack in November 2008.

- Then again in April 2010, then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and Pakistani PM Yousuf Raza Gillani on the margins of the SAARC Summit, spoke about the willingness to resolve the issue and resume the bilateral dialogue.

- Counterterrorism & Humanitarian issues

- Economic issues at Commerce

- Tulbul Navigation Project at Water Resources Secretary-level

- Siachen at Defence Secretary-level

- Peace & Security including Confidence Building Measures (CBMs)

- Jammu & Kashmir

- Promotion of Friendly Exchanges at the level of the Foreign Secretaries.

- Cross LoC travel was started in 2005 and trade across J&K was initiated in 2009

- India and Pakistan signed a visa agreement in 2012 leading to liberalization of bilateral visa regimes between the two countries

Aspirants can also get details about the Indian-International relations in the links given below:

Conflict Zones between India and Pakistan

There have been a few constant factors which have led to the complex bilateral ties between the two countries. Discussed below are these factors as per the latest developments released by the Government authorities, as of February 2020:

Cross-border Terrorism

- Terrorism emanating from territories under Pakistan’s control remains a core concern in bilateral relations

- India has consistently stressed the need for Pakistan to take credible, irreversible and verifiable action to end cross border terrorism against India

- Pakistan has yet not brought the perpetrators of Mumbai terror attacks 2008 to justice in the ongoing trials, even after all the evidence have been provided to them

- India has firmly stated that it will not tolerate and comprise on issues regarding the national security

- Based on attacks in India and involvement of the neighbouring country, the Indian Army had conducted surgical strike at various terrorist launch pads across the Line of Control, as an answer to the attack at the army camp in Uri, Jammu and Kashmir

- India had again hit back over the cross border terror attack on the convey of Indian security forces in Pulwama by carrying out a successful air strike at a training camp of JeM in Balakot, Pakistan

Cross border terrorism is one of the biggest factors for the disrupted relations between India and Pakistan.

Trade and Commerce

The figures for India Pakistan bilateral trade in the last 6 years is as follows:

The trade agreement has also faced a downfall when it comes to the relations between India and Pakistan. In 2019, after the Pulwama terror attack, India hiked customs duty on exports from Pakistan to 200% and subsequently, Pakistan suspended bilateral trade with India on August 7, 2019.

There are two major routes via which trade is commenced between the two countries:

- Sea Route – Mumbai to Karachi

- Land Route – via Wagah Border through trucks

Indus Waters Treaty

The 115th meeting of Permanent Indus Commission (PIC) was held on August 29 and 30, 2018 in Lahore. The Indian delegation was led by the Indian Commissioner for Indus Water (ICIW), while the Pakistan delegation was led by Pakistan Commissioner of Indus Water (PCIW).

In the two days meeting both sides discussed Pakal Dul Hydroelectric Power Project (HEP), Lower Kalnai HEP and reciprocal tours of Inspection to both sides of the Indus basin. Subsequently, a delegation led by PCIW inspected Pakal Dul, Lower Kalnai, Ratle and other hydropower projects in the Chenab Basin between January 28 and 31, 2019.

Read in detail about the Indus Water Treaty at the linked article.

People to People Relations

- Since 2014, India has been successful in the repatriation of 2133 Indians from Pakistan’s custody (including fishermen), and still, about 275 Indians are believed to be in their custody

- In October 2017, the revival of Joint Judicial Committee was proposed by India and accepted by Pakistan, wherein, the humanitarian issues of custody of fishermen and prisoners, especially the ones who are mentally not sound in each other’s custody need to be followed

- The Bilateral Protocol on Visits to Religious Shrines was signed between the two countries in 1974. The protocol provides for three Hindu pilgrimage and four Sikh pilgrimage every year to visit 15 shrines in Pakistan while five Pakistan pilgrimage visit shrines in India.

Kartarpur Corridor

- An agreement between India and Pakistan for the facilitation of pilgrims to visit Gurdwara Darbar Sahib Kartarpur, Pakistan, was signed on 24 October 2019 in order to fulfil the long-standing demand of the pilgrims to have easy and smooth access to the holy Gurudwara

- The Kartarpur Sahib Corridor Agreement, inter alia, provides for visa-free travel of Indian pilgrims as well as Overseas Citizen of India (OCI) cardholders, from India to the holy Gurudwara in Pakistan on a daily basis, throughout the year.

- On November 9, 2019, on the occasion of the 550th birth anniversary of Guru Nanak Dev ji, Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurated the corridor

Aspirants can know in detail about the Kartarpur Corridor at the linked article and know its religious and social importance.

Kashmir Issue

This is one of the most sensitive issues between India and Pakistan and has been a major cause of the sour relations the two countries share. Article 370 gave Jammu and Kashmir a special right to have its own constitution, a separate flag and have their own rules, but in August 2019, the Article was scrapped off and J&K now abides by the Indian Constitution common for all. It was given the status of a Union Territory and this move of the Indian Government was highly objected by Pakistan due to their longing of owning Kashmir entirely.

Trade Agreement between India and Pakistan

The two countries had signed a Trade agreement which was mutually beneficial for both. Discussed below are the ten Articles of the Trade Agreement:

Article I – exchange of products shall be done based on the mutual requirement of both the countries, ensuring common advantages

Article II – With regard to the commodities/goods mentioned in Schedules ‘A’ and ‘B’ attached to this Agreement, the two Governments shall facilitate imports from and exports to each other’s territories to the extent permitted by their respective laws, regulations and procedures

Article III – The import/export shall take place only through commercial means approved by both side

Article IV – With respect to commodities/goods not included in Schedules ‘A’ and ‘B’ export or import shall also be permitted in accordance with the laws, regulations and procedures in force in either country from time to time

Article V – Each Government shall accord to the commerce of the country

Article VI – There are a few exceptions for Article V

Article VII – The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade must be followed

Article VIII – Border trade shall be allowed for the day-to-day requirement of commodities

Article IX – For proper implementation of the agreement, meetings can be done every six months

Article X – The Trade Agreement between the two countries waa effective from February 1, 1957

List of Products India Imports from Pakistan

List of Products India Exports to Pakistan

Candidates can get the detailed UPSC Syllabus for the Prelims and Mains examination at the linked article and can start their preparation accordingly.

Also, to get the latest exam updates, preparation strategy and study material, turn to BYJU’S for assistance.

Frequently Asked Questions on India-Pakistan Relations

Q 1. what is the biggest cause of concern between india and pakistan relations, q 2. what was the indus water treaty and between who was it signed.

UPSC General Studies Paper-2 Preparation:

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

IAS 2024 - Your dream can come true!

Download the ultimate guide to upsc cse preparation.

- Share Share

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

- Washington DC, USA

- California, USA

- Activities in Singapore and Beijing, China

- Brussels, Belgium

- New Delhi, India

- Beirut, Lebanon

- Berlin, Germany

India-Pakistan Relations and Regional Stability

India and Pakistan have considerable scope to build on the various confidence-building measures that have been negotiated in the past decade and a half, especially in the areas of trade and economic cooperation.

Source: National Bureau of Asian Research

This essay reviews the current state of India-Pakistan relations and examines the prospects for bilateral and regional cooperation between the two South Asian neighbors.

MAIN ARGUMENT

India and Pakistan have considerable scope to build on the various confidence-building measures that have been negotiated in the past decade and a half, especially in the areas of trade and economic cooperation. Greater economic engagement has the potential to generate interdependence that could help promote the normalization of relations. However, policymakers in both countries face familiar obstacles to a normal relationship—cross-border terrorism originating from Pakistan, differences over Kashmir, and entrenched domestic opposition to broadening engagement on both sides of the border. The inability of policymakers to separate progress in one field from differences in other areas has rendered it difficult to expand and sustain cooperation. More immediately, India-Pakistan relations are further complicated by the turbulent regional dynamic centered on Afghanistan. The drawdown of foreign troops after over a decade-long international presence in Afghanistan and the challenges of producing internal stability there will make the construction of a shared vision for regional cooperation elusive.

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

This essay offers the following policy recommendations for limiting conflict between India and Pakistan and expanding the scope for cooperation:

- India and Pakistan need to find ways to sustain their resumed dialogue.

- Trade and commercial relations, where quick advances are possible, should be isolated from differences in other fields.

- An early restoration of the ceasefire agreement along the Line of Control and the international border in Kashmir will help arrest the further deterioration of the security environment and create the space for progress elsewhere.

- India should take unilateral steps, wherever possible, to improve relations. It has taken such initiatives in the past—for example, in granting most-favored-nation status to Pakistan in 1996.

- India and Pakistan should begin a dialogue on the future of Afghanistan.

This chapter is available on the National Bureau of Asian Research website.

Read Full Text

More work from carnegie.

The postponement of Erdoğan’s Washington visit may be a missed opportunity, but the NATO Summit in July offers a chance to get back on track.

- Alper Coşkun

Europeans still lack a common vision for how to ensure the continent’s security. Regardless of who becomes the next U.S. president, a stronger European pillar in NATO is essential.

- Judy Dempsey

The ongoing African Growth and Opportunity Act reauthorization process could facilitate the expansion of U.S.-Africa trade in critical minerals.

- Zainab Usman ,

- Alexander Csanadi

This essay is the first of a three-part series that will seek to understand the considerations for building compute capacity and the different pathways to accessing compute in India. This essay delves into the meaning of compute and unpacks the various layers of the compute stack.

- Aadya Gupta ,

- Adarsh Ranjan

The opening of EU accession talks marks an important milestone for Bosnia, where ethnic tensions run high. But progress on the EU track is no remedy for the chronic crisis besetting the country’s politics.

- Dimitar Bechev

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

UPSC Coaching, Study Materials, and Mock Exams

Enroll in ClearIAS UPSC Coaching Join Now Log In

Call us: +91-9605741000

India-Pakistan Relations – Terrorism, Kashmir, and Recent Issues

Last updated on September 21, 2023 by ClearIAS Team

Kashmir has been the bedrock issue between both the nations and has been an unresolved boundary dispute.

Terrorism , particularly targeting India which is bred on Pakistani soil is yet another major issue which has mired the relationship.

Despite many positive initiatives taken, the India-Pakistan relationship in recent times has reached an all-time low with some sore issues sticking out. Here we are analysing the core issues in the India-Pakistan relationship.

Table of Contents

Present Context and the Issues in India-Pakistan Relationship

- With the regime change in India, there was a perception that a hard line and staunch policy towards Pakistan would be followed. However, the current Prime Minister (PM) of India put forward the idea of ‘Neighborhood First’, which was particularly aimed at improving relationships within the Indian Subcontinent.

- There were initiatives taken by the government, for example, inviting the Prime Minister of Pakistan for the swearing-in ceremony of the new PM of India, an unscheduled visit to Lahore by the Indian PM to the residence of the PM of Pakistan, which showed some signs of positive development.

- However, with the attack on the Indian Air Force Base in 2016 (Pathankot) January, just a few days after Indian PM visited the Pakistani counterpart, events thereafter haven’t been really encouraging. There has been a complete stoppage of talks at all levels in between the nations. Speculations, however, run that back-channel talks exist.

- With rising discontent and a volatile situation once again in Kashmir from mid-2016, India has accused Pakistan of adding fuel to the unrest and glorifying terrorists by declaring them, martyrs.

- Terrorist attacks on security forces since have increased and the attack on the Uri Army base camp in September 2016, where 19 Indian soldiers were killed, was also carried by an organization, which has its roots in Pakistan. (Lashkar-e-Toiba, also responsible for 26/11 attacks)

- The case of Kulbushan Jadhav , a retired Indian Naval officer arrested nears the Iran-Pakistan border in Baluchistan region by the Pakistani establishment and accused of espionage by Pakistan.

- On 14 February 2019, a convoy of vehicles carrying security personnel on the Jammu Srinagar National Highway was attacked by a vehicle-borne suicide bomber in the Pulwama district of Jammu and Kashmir. The attack resulted in the deaths of 40 Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) personnel and the attacker.

Changing Political Scenario in Pakistan

- For quite a while, the Panama Papers issue was being raked up in Pakistan and the then PM Nawaz Sharif of Pakistan was alleged to have received unaccounted money from abroad. The Supreme Court of Pakistan recently disqualified the PM from office, making him the second PM in the history of Pakistan to be disqualified from office.

- This backdrop comes at a time when the already existing India-Pakistan relations are at a low and with the disqualified PM being perceived as someone who has always wanted to improve the relationship with India, it is not good news for India in a way.

- In the ouster, surprisingly, the Pakistani Army has remained silent publicly on the issue. However, in the Joint Investigation Team created by the Supreme Court of Pakistan, there was the presence of a Military Intelligence Official and an Inter Services Intelligence (ISI) Official, which shows that the influence the military establishment still continues to have a stronghold in Pakistan.

- Some people perceive the judgment of the Supreme Court of Pakistan, as being politically motivated, with some saying there was a judicial overreach by the Court. Also, the court has directed the National Accountability Bureau to further investigate into cases related to Panama papers.

- However, there are also reports that the developments are a sort of deepening the roots of democracy in Pakistan because the due process of law was followed.

Pakistan Politics and the Impact on India-Pakistan relationship

- The disqualified PM was seen as someone who tried to pursue a better relationship with India. Thus, his ouster can have implications with the incoming new PM of Pakistan.

- This can be a cause of concern because of the background scenario with the relationship between both countries already fraught and the Pakistan Army indirectly flexing its muscle in the process of the ouster of the PM. The future thus remains uncertain.

Terrorism and Kashmir – The never-ending issues

- Cross border terrorism has always been an issue.

- Some analysts go to the extent of saying that both nations are always in a perpetual state of war.

- Despite the fact the after the Kargil conflict, there was a Ceasefire Agreement signed in 2003, there have been regular cross border ceasefire violations from the Pakistan side of the border with the trend being as such that since 2009 onwards, there has been a rise in the violations (with the exception of 2014). It has killed and injured security forces as well as civilians on both sides.

Add IAS, IPS, or IFS to Your Name!

Your Effort. Our Expertise.

Join ClearIAS

- With the regime change in India, there has been a different approach to the violations. With the hardline policy of the new government, there has been massive retaliation to the unprovoked firing.

- Thus, out of desperation, there has been a rise in the number of infiltrations of terrorists from across the Line of Control (LOC), which has been routine for quite a while now.

- With the void in between the Kashmiri people and the establishment increasing after the devastating floods of 2014 , there was rising discontent again in the valley. The trigger to the events was the killing of the militant commander of the terrorist organization Hizb-ul-Mujahideen Burhan Wani , which led to widespread protests in the valley and the situation has been highly volatile ever since with almost daily scenes of protests and stone pelting in the valley.

- Pakistan has taken advantage of the situation and has fuelled the protests by providing the elements fighting against the Indian establishment and Forces in the state with all sorts of possible support. The PM of Pakistan, in fact, went a step ahead and during the United Nations General Assembly meeting of 2016, declared Wani as a martyr and the struggle of the people of Kashmir as an Intifada .

- This is in sync with the stand Pakistan holds on Kashmir i.e., to internationalize the issue of Kashmir and asking for holding a plebiscite in Kashmir under Indian administration to decide the fate of Kashmiri people. The stand has been rejected by India as it says it is in direct violation of the Shimla Agreement of 1972 , which clearly mentions that peaceful resolution to all issues will be through bilateral approach .

- After the attack at the Pathankot base in 2016 January, there was again a thaw in the relationship, especially when seen in the context that the Indian PM paid an unscheduled visit to Pakistan to meet his Pakistani counterpart. With Kashmir already on the boil and Pakistan adding fuel to fire to the situation, the attack on Uri Army camp in September 2016 in which 19 Indian soldiers were killed made the Indian PM declare the statement that ‘talks and terrorism’ cannot go hand in hand .

- This was followed by surgical strikes carried out by the Indian Army across the LOC targeting the terror infrastructure in Pakistan occupied Kashmir (PoK). They were carried out at the end of September.

- In a first, India tinkered with the Indus Water Treaty , a Treaty which has stood the test of time and the bitter sour relationship for more than 55 years and was pondering with the fact to fully exploit the water potential of the West flowing rivers over which Pakistan has control.

- Thus, the fact trickles down to the point that India has its stand that until Pakistan doesn’t do enough to tackle the terrorism menace, there can be no talks held in between the nations.

- On the other hand, Pakistan is ready for a dialogue with India but it wants the inclusion and discussion of the Kashmir issue which it keeps raking up every time.

The Curious Case of Kulbushan Jadhav

- The case of Kulbushan Jadhav, a retired Naval officer arrested nears the Iran-Pakistan border in Baluchistan region by the Pakistani establishment.

- He has been accused by Pakistan of espionage and spying and has been sentenced to death by a military court in Pakistan.

- India, on many previous occasions, demanded consular access of Jadhav, a demand consistently rejected by Pakistan citing national security issues.

- India says that Jadhav was a retired Naval officer who was a businessman working in Iran and has been falsely framed by the Pakistani establishment.

- As there were repeated denials of the Consular Access , India approached the International Court of Justice (ICJ) at Hague where it put forward the argument that Vienna Convention was being violated as the Consular Access was denied.

- The ICJ has asked Pakistan to stay the execution of Jadhav and the matter is sub judice.

Future of India-Pakistan relationship

- India and Pakistan are neighbours. Neighbours can’t be changed . Thus, it is in the better of interest of both the nations that they bring all the issues on the drawing board and resolve them amicably.

- India wants Pakistan to act more strongly on the terrorism being sponsored from its soil .

- Also, India wants Pakistan to conclude the trial of 26/11 sooner so that the victims are brought to justice and the conspirers meted out proper punishment.

- India has genuine concerns, as there are internationally declared terrorists roaming freely in Pakistan and preaching hate sermons as well as instigating terror attacks.

- With the international community accusing Pakistan of breeding terrorism on its soil, Pakistan cannot remain in denial state and thus, needs to act tougher on terrorism-related issues.

- In 2018, Imran Khan became the 22nd Prime Minister of Pakistan. PM Imran Khan received a lot of praise for releasing the IAF pilot Abhinandan who was captured in Pakistan during the counter-terrorism operations (after the Pulwama attack) in 2019.

India-Pakistan Relations: Positive initiatives which were taken in the past

- Composite Dialogue Framework , which was started from 2004 onwards, excluded, some of the contentious issues between the two sides had resulted in good progress on a number of issues.

- Delhi-Lahore Bus service was successful in de-escalating tensions for some time.

- Recently, the ‘ Ufa ‘Agreement ’ was made during the meeting of the National Security Advisors of both nations at Ufa, Russia.

A couple of important points agreed upon in Ufa were:

- Early meetings of DG BSF and DG Pakistan Rangers followed by the DGMOs.

- Discussing ways and means to expedite the Mumbai case trial, including additional information needed to supplement the trial.

Ufa Agreement has now become a new starting point of any future India-Pakistan dialogue, which is a major gain for India.

However, despite all the initiatives, there is always a breakdown in talks. Thus, more needs to be done for developing peaceful relations. With India and Pakistan both being two Nuclear States , any conflict can lead to a question mark on the existence of the subcontinent as well as the entire planet, especially with the border being ‘live’ almost all the time.

Benefits, which can be accrued from a good India-Pakistan Relationship

- If there is peace at the border and a solution of Kashmir is arrived upon, then the China Pakistan Economic Corridor , which is passing through Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (PoK) can certainly benefit Kashmir, its people and the economy. Kashmir can act as a gateway to Central Asia .

- Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline which originates in Turkmenistan and passes through Afghanistan, Pakistan before reaching and terminating in India can also get huge benefits as it can help secure the National Energy needs of both Pakistan and India, which are potentially growing nations with increasing needs of energy.

- Iran-Pakistan-India pipeline is another project, which is currently stalled. If relations are cordial, then this pipeline can also supply the energy needs of both nations.

- A stable Afghanistan is in the best interest of both Pakistan as well as India. Terrorism is affecting both India as well as Pakistan and the porous boundary between Afghanistan and Pakistan provides a safe haven for terrorists. Also, a better relationship with Pakistan can give direct road access to Afghanistan . Currently, India has to go via Iran to Afghanistan to send any trade goods and vice versa.

- South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) and the initiatives taken by the association will start to hold more relevance as the same hasn’t lived up to its expected potential as the elephant in the room during any summit is sour in the India-Pakistan relationship.

Article by: Aadarsh Clerk

Aim IAS, IPS, or IFS?

Prelims cum Mains (PCM) GS Course: Target UPSC CSE 2025 (Online)

₹95000 ₹59000

Prelims cum Mains (PCM) GS Course: Target UPSC CSE 2026 (Online)

₹115000 ₹69000

Prelims cum Mains (PCM) GS Course: Target UPSC CSE 2027 (Online)

₹125000 ₹79000

About ClearIAS Team

ClearIAS is one of the most trusted learning platforms in India for UPSC preparation. Around 1 million aspirants learn from the ClearIAS every month.

Our courses and training methods are different from traditional coaching. We give special emphasis on smart work and personal mentorship. Many UPSC toppers thank ClearIAS for our role in their success.

Download the ClearIAS mobile apps now to supplement your self-study efforts with ClearIAS smart-study training.

Reader Interactions

August 14, 2017 at 9:16 pm

Sharif is not the first PM to be disqualified. Raza Gilani was disqualified in 2012.

August 15, 2017 at 12:21 am

Apologies for the mistake. Point taken into consideration and corrected.

August 16, 2017 at 10:22 am

GIVE me Links Of All Important GS News For 2018 prepartion

October 8, 2017 at 3:48 pm

Sir can I get a notes on India – China relation

December 11, 2017 at 6:49 am

What’s the problem with TAPI pipeline such that it can be improved after cordial relations with Pakistan? I have checked on google there is nothing showing other than the amount of investment needs to be enhanced

June 30, 2018 at 1:19 pm

Nice one article thanku sir .. shall v hv a WhatsApp group for updating of current topics

April 10, 2019 at 7:10 pm

Sir how can we know abt ur latest updates…is there nd whts grp. Or.. Smthing else.. For keep connecting with u

September 28, 2019 at 3:15 pm

How we make a project on the topic Indo-pak relation according this information

March 5, 2021 at 10:36 am

You did not cite Kashmir in the Future of India-Pakistan relationship as this is main bone of contention between Pakistan and India relations since 1948. This issue should be resolved for the betterment poor people of the region. India and Pakistan are neighbours. Neighbours can’t be changed. Thus, it is in the better of interest of both the nations that they bring all the issues on the drawing board and resolve them amicably. In this article you mentioned terrorism but terrorism is matter of last two to three decades but enmity between both nuclear armed countries prevailed from 70 years . Both countries should resolve their mutual issues amicably.

March 5, 2021 at 10:37 am

You did not cite Kashmir in the Future of India-Pakistan relationship as this is main bone of contention between Pakistan and India relations since 1948. This issue should be resolved for the betterment poor people of the region. India and Pakistan are neighbours. Neighbours can’t be changed. . In this article you mentioned terrorism but terrorism is matter of last two to three decades but enmity between both nuclear armed countries prevailed from 70 years . Both countries should resolve their mutual issues amicably.

March 16, 2021 at 3:49 pm

It is quite simple. Let india create work towards creating its own narrative in kashmir, through development. Even if Rederrendum happens in future, it will go in favour of INDIA. Pakistan will not change, unless the political re-structuring takes place in Pakistan. For now Pakistan is a rogue state. we cannot expect a rational behaviour from rogue states like Pakistan or North-Korea.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Don’t lose out without playing the right game!

Follow the ClearIAS Prelims cum Mains (PCM) Integrated Approach.

Join ClearIAS PCM Course Now

UPSC Online Preparation

- Union Public Service Commission (UPSC)

- Indian Administrative Service (IAS)

- Indian Police Service (IPS)

- IAS Exam Eligibility

- UPSC Free Study Materials

- UPSC Exam Guidance

- UPSC Prelims Test Series

- UPSC Syllabus

- UPSC Online

- UPSC Prelims

- UPSC Interview

- UPSC Toppers

- UPSC Previous Year Qns

- UPSC Age Calculator

- UPSC Calendar 2024

- About ClearIAS

- ClearIAS Programs

- ClearIAS Fee Structure

- IAS Coaching

- UPSC Coaching

- UPSC Online Coaching

- ClearIAS Blog

- Important Updates

- Announcements

- Book Review

- ClearIAS App

- Work with us

- Advertise with us

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Talk to Your Mentor

Featured on

and many more...

Take ClearIAS Mock Exams: Analyse Your Progress

UPSC Prelims Test Series for GS and CSAT: With Performance Analysis and All-India Ranking (Online)

₹9999 ₹4999

Timeline: India-Pakistan relations

A timeline of the rocky relationship between the two nuclear-armed South Asian neighbours.

1947 – Britain, as part of its pullout from the Indian subcontinent, divides it into secular (but mainly Hindu) India and Muslim Pakistan on August 15 and 14 respectively. The partition causes one of the largest human migrations ever seen and sparks riots and violence across the region.

1947/48 – The first India-Pakistan war over Kashmir is fought, after armed tribesmen (lashkars) from Pakistan’s North-West Frontier Province (now called Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa) invade the disputed territory in October 1947. The Maharaja, faced with an internal revolt as well an external invasion, requests the assistance of the Indian armed forces, in return for acceding to India. He hands over control of his defence, communications and foreign affairs to the Indian government.

![india pakistan relations essay Maharaja of Kashmir, June 20, 1946 [File: The Associated Press]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/cf3988d32671423baa9401ce77e9e7b2_18.jpeg)

Both sides agree that the instrument of accession signed by Maharaja Hari Singh be ratified by a referendum, to be held after hostilities have ceased. Historians on either side of the dispute remain undecided as to whether the Maharaja signed the document after Indian troops had entered Kashmir (i.e. under duress) or if he did so under no direct military pressure.

Fighting continues through the second half of 1948, with the regular Pakistani army called upon to protect Pakistan’s borders.

The war officially ends on January 1, 1949, when the United Nations arranges a ceasefire, with an established ceasefire line, a UN peacekeeping force and a recommendation that the referendum on the accession of Kashmir to India be held as agreed earlier. That referendum has yet to be held.

Pakistan controls roughly one-third of the state, referring to it as Azad (free) Kashmir. It is semi-autonomous. A larger area, including the former kingdoms of Hunza and Nagar, is controlled directly by the central Pakistani government.

The Indian (eastern) side of the ceasefire line is referred to as Jammu and Kashmir state.

Both countries refer to the other side of the ceasefire line as “occupied” territory.

1954 – The accession of Jammu and Kashmir to India is ratified by the state’s constituent assembly.

1957 – The Jammu and Kashmir constituent assembly approves a constitution. India, from the point of the 1954 ratification and 1957 constitution, begins to refer to Jammu and Kashmir as an integral part of the Indian union.

1963 – Following the 1962 Sino-Indian war, the foreign ministers of India and Pakistan – Swaran Singh and Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto – hold talks under the auspices of the British and Americans regarding the Kashmir dispute. The specific contents of those talks have not yet been declassified, but no agreement was reached. In the talks, “Pakistan signified willingness to consider approaches other than a plebiscite and India recognised that the status of Kashmir was in dispute and territorial adjustments might be necessary,” according to a declassified US state department memo (dated January 27, 1964).

1964 – Following the failure of the 1963 talks, Pakistan refers the Kashmir case to the UN Security Council.

![india pakistan relations essay Army general J N Chaudhuri and Air Marshal Arjan Singh at the Defence Headquarters in New Delhi after the cease-fire following the second India-Pakistan conflict in 1965. [Photo by Keystone/Getty Images]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/1f6ce737a7b74e7ab4941c5749558d43_18.jpeg)

1965 – India and Pakistan fight their second war. The conflict begins after a clash between border patrols in April in the Rann of Kutch (in the Indian state of Gujarat), but escalates on August 5, when between 26,000 and 33,000 Pakistani soldiers cross the ceasefire line dressed as Kashmiri locals, crossing into Indian-administered Kashmir.

Infantry, armour and air force units are involved in the conflict while it remains localised to the Kashmir theatre, but as the war expands, Indian troops cross the international border at Lahore on September 6. The largest engagement of the war takes place in the Sialkot sector, where between 400 and 600 tanks square off in an inconclusive battle.

By September 22, both sides agree to a UN-mandated ceasefire, ending the war that had by that point reached a stalemate, with both sides holding some of the other’s territory.

1966 – On January 10, 1966, Indian Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri and Pakistani President Ayub Khan sign an agreement at Tashkent (now in Uzbekistan), agreeing to withdraw to pre-August lines and that economic and diplomatic relations would be restored.

![india pakistan relations essay An elderly Pakistani refugee is pushed aside by Indian troops advancing into the East Pakistan (Bangladesh) area during the 1971 Indo-Pakistani war. [Getty Images]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/d4c87a2129a541c39be2781590a1f573_18.jpeg)

1971 – India and Pakistan go to war a third time, this time over East Pakistan. The conflict begins when the central Pakistani government in West Pakistan, led by Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, refuses to allow Awami League leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, a Bengali whose party won the majority of seats in the 1970 parliamentary elections, to assume the premiership.

A Pakistani military crackdown on Dhaka begins in March, but India becomes involved in the conflict in December, after the Pakistani air force launches a pre-emptive attack on airfields in India’s northwest.

India then launches a coordinated land, air and sea assault on East Pakistan. The Pakistani army surrenders at Dhaka, and its army of more than 90,000 become prisoners of war. Hostilities lasted 13 days, making this one of the shortest wars in modern history.

East Pakistan becomes the independent country of Bangladesh on December 6, 1971.

![india pakistan relations essay Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, right, and President of Pakistan Zulfikar Ali Bhutto shake hands after signing and agreement in the Governor's Mansion, in Simla on June 28, 1972. [The Associated Press]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/f3033a04e8d340318b8a2b21d92b5c93_18.jpeg)

1972 – Pakistani Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi sign an agreement in the Indian town of Simla, in which both countries agree to “put an end to the conflict and confrontation that have hitherto marred their relations and work for the promotion of a friendly and harmonious relationship and the establishment of a durable peace in the subcontinent”. Both sides agree to settle any disputes “by peaceful means”.

The Simla Agreement designates the ceasefire line of December 17, 1971, as being the new “Line-of-Control (LoC)” between the two countries, which neither side is to seek to alter unilaterally, and which “shall be respected by both sides without prejudice to the recognised position of either side”.

1974 – The Kashmiri state government affirms that the state “is a constituent unit of the Union of India”. Pakistan rejects the accord with the Indian government.

On May 18, India detonates a nuclear device at Pokhran, in an operation codenamed “Smiling Buddha”. India refers to the device as a “peaceful nuclear explosive”.

1988 – The two countries sign an agreement that neither side will attack the other’s nuclear installations or facilities. These include “nuclear power and research reactors, fuel fabrication, uranium enrichment, isotopes separation and reprocessing facilities as well as any other installations with fresh or irradiated nuclear fuel and materials in any form and establishments storing significant quantities of radio-active materials”.

Both sides agree to share information on the latitudes and longitudes of all nuclear installations. This agreement is later ratified, and the two countries share information on January 1 each year since then.

1989 – Armed resistance to Indian rule in the Kashmir valley begins. Muslim political parties, after accusing the state government of rigging the 1987 state legislative elections, form activist wings.

Pakistan says that it gives its “moral and diplomatic” support to the movement, reiterating its call for the earlier UN-sponsored referendum.

India says that Pakistan is supporting the resistance by providing weapons and training to fighters, terming attacks against it in Kashmir “cross-border terrorism”. Pakistan denies this.

Activist groups taking part in the fight in Kashmir continue to emerge through the 1990s, in part fuelled by a large influx of “mujahideen” who took part in the Afghan war against the Soviets in the 1980s.

1991 – The two countries sign agreements on providing advance notification of military exercises, manoeuvres and troop movements, as well as on preventing airspace violations and establishing overflight rules.

1992 – A joint declaration prohibiting the use of chemical weapons is signed in New Delhi.