- ACS Foundation

- Inclusive Excellence

- ACS Archives

- Careers at ACS

- Federal Legislation

- State Legislation

- Regulatory Issues

- Get Involved

- SurgeonsPAC

- About ACS Quality Programs

- Accreditation & Verification Programs

- Data & Registries

- Standards & Staging

- Membership & Community

- Practice Management

- Professional Growth

- News & Publications

- Information for Patients and Family

- Preparing for Your Surgery

- Recovering from Your Surgery

- Jobs for Surgeons

- Become a Member

- Media Center

Our top priority is providing value to members. Your Member Services team is here to ensure you maximize your ACS member benefits, participate in College activities, and engage with your ACS colleagues. It's all here.

- Membership Benefits

- Find a Surgeon

- Find a Hospital or Facility

- Quality Programs

- Education Programs

- Member Benefits

- The rise and fall of gende...

The rise and fall of gender identity clinics in the 1960s and 1970s

Editor’s note: this article is based on the second-place poster in the american college of surgeons history of surgery poster contest at the virtual clinical congress 2020. the authors note that as the field of medicine and society have evolved to better understand the experiences of transgender individuals, terminology has changed significantly. the authors have […].

Melanie Fritz, Nat Mulkey

April 1, 2021

Editor’s note: This article is based on the second-place poster in the American College of Surgeons History of Surgery poster contest at the virtual Clinical Congress 2020. The authors note that as the field of medicine and society have evolved to better understand the experiences of transgender individuals, terminology has changed significantly. The authors have kept the original wording of direct quotes, but elsewhere in the article terminology is used that is consistent with present-day standards; that is, “transgender” or “transgender and gender nonbinary.”

HIGHLIGHTS Summarizes early pioneering work in the GAS field in the U.S. and Europe Describes the effects of clinic closures in the 1970s Outlines the resurgence of multidisciplinary clinics for TGNB patients at academic centers and in private practice Identifies ongoing barriers related to GAS, including financial concerns and access to reliable information

Transgender and gender nonbinary (TGNB) individuals have existed for thousands of years and in cultures throughout the world. In Western medicine, however, the modern era of gender-affirming surgery (GAS) began at the Institute of Sexual Research in Berlin, Germany, under the leadership of Magnus Hirschfeld, MD. Surgeons at the institute performed the earliest vaginal constructions in the 1930s. Early patients included an employee of the facility, known by the last name of Dorchen, and the Danish painter Lili Elbe, whose story was depicted in the 2015 film The Danish Girl . 1

Around the same time that Dr. Hirschfeld’s institute began performing vaginoplasties, the father of plastic surgery, Sir Harold Gillies, OBE, FRCS, had been refining techniques for genital construction in Britain. He did so primarily by operating on British men who had sustained genital injuries during wartime and subsequently presented to him for assistance. In the 1940s, he performed the first known phalloplasty for a transgender patient on Michael Dillon, MD, a British physician. Dr. Gillies later performed a vaginoplasty on patient Roberta Cowell, who gained some renown in Britain. 2

In the 1950s, Georges Burou, MD, began performing vaginoplasty operations in Casablanca, Morocco, and is widely credited with inventing the anteriorly pedicled penile skin flap inversion vaginoplasty. 3

Increased awareness in the U.S.

One of the earliest known GAS procedures performed in the U.S. was for patient Alan Hart, MD, a transgender man and physician, who underwent a hysterectomy in 1910. 1

The field of GAS subsequently remained dormant in the U.S. until the 1950s, when pioneers like Elmer Belt, MD, University of California Los Angeles, and Milton Edgerton, MD, Johns Hopkins University (JHU) began performing GAS. 4,5

The work of sexologist and endocrinologist Harry Benjamin, MD, in the 1950s and 1960s provided additional momentum to the field within the medical community. At the time, many psychiatrists and physicians believed that the correct approach to treating transgender patients was exclusively through psychoanalytic therapy aimed at altering the desire to live as a different gender. Dr. Benjamin is attributed with being one of the first physicians to challenge this notion.

In 1966, he published The Transsexual Phenomenon , which detailed the era’s approach to GAS. 4 Notably, this text includes far more detail about male-to-female (MTF) surgical operations, such as vaginoplasty, than female-to-male (FTM) operations, such as phalloplasty or metoidioplasty. At the time, transgender men were incorrectly believed to be less common than transgender women, and surgeons were reluctant to perform FTM GAS procedures. Based on writings from the era, some of this reluctance stemmed from uncertainty as to whether surgical techniques were capable of constructing a neophallus that would be satisfactory to the patient. 6

A boom of awareness of GAS within both the field of medicine and the larger U.S. public can primarily be attributed to one individual: Christine Jorgensen. Ms. Jorgensen was a transgender woman who captured the attention and interest of the general public after undergoing a series of operations for GAS in Denmark from 1951 to 1952. 4 Her coming out story and transition were covered extensively in popular media, appearing in the New York Daily News under the eye-catching headline “Ex-GI Becomes Blonde Beauty.” 7

Wave of clinics providing GAS

Publication of Dr. Benjamin’s book coincided with the public announcement of JHU Gender Identity Clinic in November 1966. 8 While several major academic centers had internally discussed the formation of research institutes to study the treatment of transgender patients since the early 1960s, the opening of the JHU clinic marked a transition from quiet deliberation to public recruitment for research on GAS. Initiatives quickly sprung up at many major universities and hospitals, marked by interdisciplinary collaboration between psychiatrists, urologists, plastic surgeons, gynecologists, and social workers. While estimates vary, the increase in U.S. patients who underwent GAS was dramatic, growing to more than 1,000 by the end of the 1970s from approximately 100 patients in 1969. 5,9

Producing positive results in a stigmatized field

Whereas GAS was a new endeavor for U.S. physicians, these clinics primarily operated as research programs. As a new field of practice, the physicians involved in the clinics faced significant skepticism from colleagues, such as psychiatrist Joost Meerloo, MD, who outlined his concerns in the American Journal of Psychiatry in 1967. Dr. Meerloo wrote, “Unwittingly, many a physician does not treat the disease as such but treats, rather, the fantasy a patient develops about his disease…I believe the surgical treatment of transsexual yearnings easily falls into this trap…. What about our medical responsibility and ethics? Do we have to collaborate with the sexual delusions of our patients?” 10

Understandably, physicians involved in these gender identity clinics described feeling pressure to demonstrate successful postoperative outcomes in order to justify their work. In the introduction to a published case series on GAS, Norman Fisk, MD, a psychiatrist at Stanford University, CA, wrote, “In our efforts we were preoccupied with obtaining good results. This preoccupation, we believed, would enable us to continue our work in an area where many professional colleagues had, and retain, serious doubts as to the validity of gender reorientation.” 11

In an attempt to obtain good results, these clinics often maintained rigorous selection criteria that excluded a number of patients. The evaluation process required that patients undergo hormone treatment and live for a set period of time as the gender to which they intended to transition. This period of time could extend up to five years depending on the clinic, imposing a significant burden on patients. As one patient, transgender man Mario Martino, stated, “One talks of a period of two to five years. I agree that people should be tested. I think that they should be tested in every way possible before being accepted as a candidate for treatment. However, one of the problems that people tend to forget is that a female with a 48-inch bust cannot pass as a male for one day, much less for one year or five years, no matter how much he tries.” 12

Individuals who were considered traditionally attractive and were expected to be easily perceived as a member of the other sex, as well as individuals who were heterosexual per their gender identity, were considered better surgical candidates. To demonstrate the scale of this selectivity, out of 2,000 applications sent to JHU within two years of opening, only 24 patients underwent an operation. 5,11,13

Though early studies were small, many did, in fact, demonstrate successful psychiatric outcomes. A report from Edgerton and colleagues in 1970 found that at one to two years postoperatively, of nine patients who underwent GAS, all were glad to have undergone surgery, had greater self-confidence, and held “a brighter outlook for their future.” 5 When considering the competing demands of producing positive outcomes and providing GAS to patients in need, it’s clear how physicians working in these clinics were confronted with challenges in their roles. They were advocates for a marginalized population, and yet they also functioned as gatekeepers for thousands of transgender patients desperate for surgery and who faced reinforced gender-based stereotypes as described earlier in the eligibility criteria.

Timeline and clinic closure

Toward the end of the 1970s, many centers closed their doors to new patients. These closures often were kept out of the public eye, making it difficult to discern precise timing or causes. There were, however, two notable exceptions to the pattern of patient enrollment quietly declining and ceasing.

At JHU, a new chair of psychiatry, Paul McHugh, MD, was hired in 1975. Dr. McHugh disapproved of offering GAS to transgender patients and acknowledged that from the moment he was hired, he intended to stop this practice at the clinic. Under his leadership, JHU psychiatrist Jon Meyer, MD, published a study of 50 surgical patients from the JHU clinic, which concluded that GAS offered “no objective benefit” for transgender people. Although this claim directly contradicted a growing body of evidence that found significant benefit for transgender patients, the publication sparked the rapid closure of the JHU clinic in 1979. 14

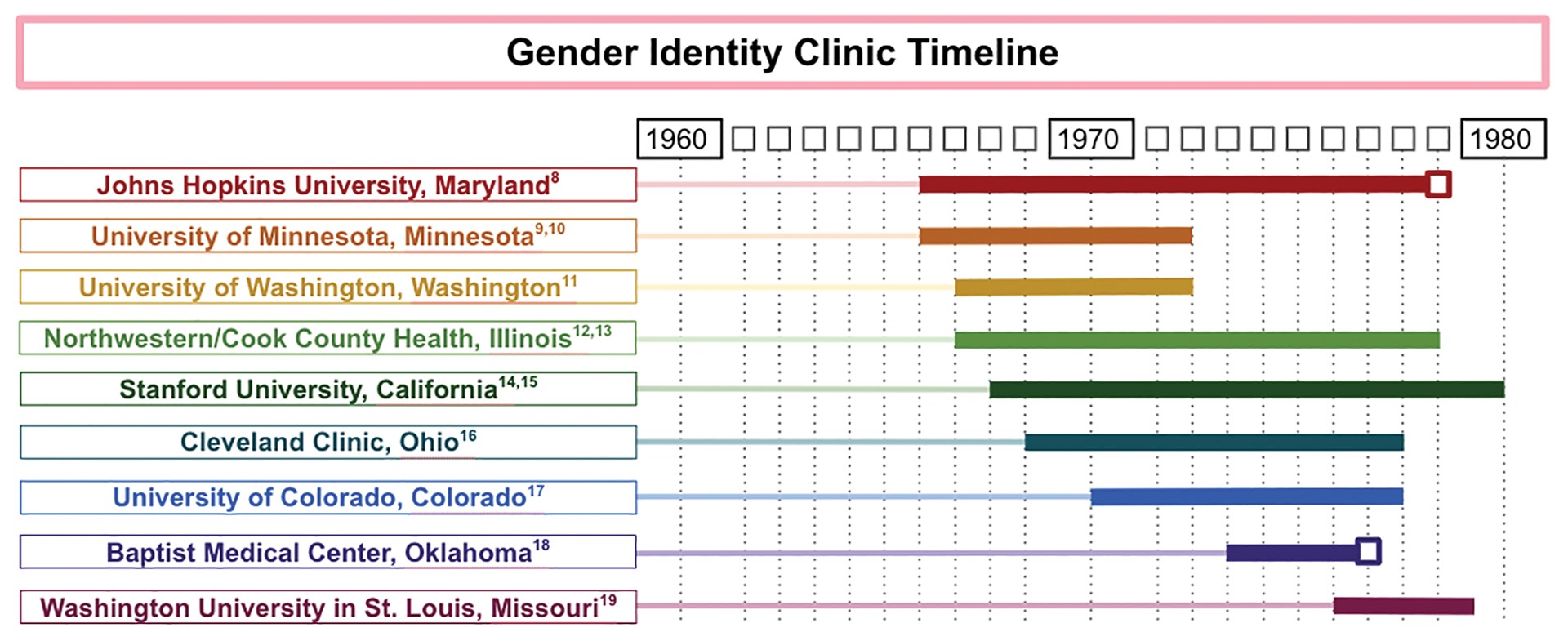

FIGURE 1. GENDER IDENTITY CLINIC TIMELINE

Another gender identity clinic where operations were abruptly terminated was the Baptist Medical Center in Oklahoma City. The Gender Identity Foundation at the center had offered a variety of services for transgender patients, including GAS, since 1973, under the radar of local religious leaders. In 1977, however, the issue of GAS was brought to the attention of the board of directors of the Baptist General Convention of Oklahoma. The physicians involved fervently advocated to be allowed to continue their practice, including surgeons Charles L. Reynolds, Jr., MD, FACS, and David W. Foerster, MD, FACS, who issued a joint statement that said, “[I]f Jesus Christ were alive today, undoubtedly he would render help and comfort to the transsexual.” Despite these appeals, the board of directors voted 54–2 to ban GAS at the Baptist Medical Center. 15

Given the known timing of when these two clinics closed, they are marked with a box in a timeline constructed by the authors (see Figure 1). The remaining end dates are estimates derived from the latest reported operations in the medical literature and news articles, which likely underestimate the length of time the clinics were in operation. The reasons for closure of the remaining clinics appear to be multifactorial.

The publicity around the Meyer paper that led to JHU’s clinic closure may have played a role in the decision to close other clinics. 16 In addition, some clinics described financial challenges during this time, as patients often were unable to afford the expensive operations, and insurance companies refused to cover them. For example, at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, clinic, the first two dozen operations were funded by a research grant at the expense of the state, but a news article from 1972 suggests that funding difficulties were exacerbated when the state no longer wanted to fund the project. 9 Institutional pushback, such as that experienced at JHU, and the retirement of leading surgeons also may have played a role in the closure of gender identity clinics across the nation.

Even though many clinics’ GAS-related research was winding down in the late 1970s, the last 15 years of academic interest motivated the 1979 establishment of the Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association. This organization, formed with the goal of organizing professionals who were “interested in the study and care of transexualism and gender dysphoria,” has since been renamed the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) and has grown into an international interdisciplinary organization. 17 WPATH has established internationally accepted guidelines for treating individuals with gender dysphoria, which are periodically updated. The most recent of these guidelines is the Standards of Care Version 7 (SOC7). 18 Today, insurance companies, national payors, and treatment teams in both the U.S. and Europe use the WPATH SOC7 guidelines for establishing surgical eligibility.

Present day significance

The contemporaneous evolution of the first wave of gender identity clinics generated a rich field for refinement of surgical technique, as well as the assessment of postoperative outcomes, and produced a foundation of scientific literature demonstrating successful psychiatric outcomes for transgender people undergoing GAS. These milestones foreshadowed a resurgence of multidisciplinary clinics for TGNB individuals in academic centers and paved the way for private practitioners to specialize in GAS. For example, Stanley Biber, MD, a private practice surgeon in Colorado, performed more than 5,000 GAS operations during his 35 years in practice. 19

Many centers for transgender medicine and surgery now exist across the U.S., and the number of GAS operations being performed in the U.S. has increased substantially, along with expanded insurance coverage. In 2015, the U.S. Transgender Survey found that 25 percent of TGNB individuals had one or more gender-affirming operations. 20 Similar to the earlier wave of clinics, present-day clinics still are frequently composed of an interdisciplinary team of primary care, surgical, and mental health professionals.

Although the number of GAS continues to increase, the current discourse echoes earlier concerns about how to limit barriers for this marginalized population while prioritizing positive surgical outcomes. The WPATH standards of care often function as guides to assist health care centers in creating TGNB health programs. 21 The WPATH SOCs have evolved since their establishment and presently tend to include fewer preoperative requirements for TGNB patients than in the 1970s and 1980s.

However, TGNB patients continue to face significant barriers to accessing GAS. A 2018 survey of TGNB patients found that the most commonly cited barriers to gender-affirming care are financial concerns, access to physicians who are knowledgeable about GAS, and access to reliable information. 22 These financial concerns can be exacerbated by the cost of obtaining the mental health evaluations recommended by WPATH SOC7, and challenges associated with insurance coverage. 23 To address these barriers, institutions are considering preoperative models besides the WPATH SOC7 to potentially reduce challenges.

Moreover, general medical education initiatives are under way to increase provider knowledge about this population. 24,25 As the field of GAS continues to evolve in the present day, we look forward to seeing how the surgical and medical community partners with patients to minimize these barriers and promote access to these essential surgical treatments.

- Denny D. Gender reassignment surgeries in the XXth century. Workshop at 9th Transgender Lives: The Intersection of Health and Law Conference, Farmington, CT. May 10, 2015. Available at: http://dallasdenny.com/Writing/2015/05/10/gender-reassignment-surgeries-in-the-xxth-century-2015/ . Accessed February 11, 2021.

- Kennedy P. The First Man-Made Man: The Story of Two Sex Changes, One Love Affair, and a Twentieth-Century Medical Revolution . New York: Bloomsbury USA; 2007.

- Hage JJ, Kareem RB, Laub DR. On the origin of pedicled skin inversion vaginoplasty: Life and work of Dr. Georges Burou of Casablanca. Ann Plast Surg . 2007;59(6):723-729.

- Benjamin H. The Transsexual Phenomenon . New York, New York: Warner Books Incorporated; 1966.

- Edgerton MT, Knorr NJ, Callison JR. The surgical treatment of transsexual patients. Limitations and indications. Plast Reconstr Surg . 1970;45(1):38-46.

- Williams G. An approach to transsexual surgery. Nurs Times . 1973;69(25):787.

- Ex-GI becomes blonde beauty: Operations transform Bronx youth. New York Daily News . December 1, 1952:75. Available at: www.newspapers.com/clip/25375703/ex-gi-becomes-blonde-beauty/ . Accessed March 22, 2021.

- Buckley T. A changing of sex by surgery begun at Johns Hopkins. The New York Times . November 21, 1966. Available at: www.nytimes.com/1966/11/21/archives/a-changing-of-sex-by-surgery-begun-at-johns-hopkins-johns-hopkins.html . Accessed March 22, 2021.

- Brody J. 500 in the U.S. change sex in six years with surgery. The New York Times . Nov 20, 1972. Available at: www.nytimes.com/1972/11/20/archives/500-in-the-u-s-change-sex-in-six-years-with-surgery-500-change-sex.html . Accessed February 11, 2021.

- Meerloo JA. Change of sex and collaboration with the psychosis. Am J Psychiatry . 1967;124(2):263-264.

- Fisk NM. Five spectacular results. Arch Sex Behav . 1978;7(4):351-369.

- Money J. Transsexualism: Open forum. Arch Sex Behav . 1978;7(4):387-415.

- Hastings D, Markland C. Post-surgical adjustment of 25 transsexuals at University of Minnesota. Arch Sex Behav . 1978;7(4):327-336.

- Siotos C, Neira PM, Lau BD, et al. Origins of gender affirmation surgery: The history of the first gender identity clinic in the United States at Johns Hopkins. Ann Plast Surg . 2019;83(2):132-136.

- Baptists vote to ban sex change operations. Sarasota Herald-Tribune . October 15, 1977.

- Nutt AE. Long shadow cast by psychiatrist on transgender issues finally recedes at Johns Hopkins. Washington Post . April 5, 2017. Available at: www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/long-shadow-cast-by-psychiatrist-on-transgender-issues-finally-recedes-at-johns-hopkins/2017/04/05/e851e56e-0d85-11e7-ab07-07d9f521f6b5_story.html . Accessed February 11, 2021.

- Walker PA. The University of Texas Medical Branch. Memo to persons interested in the Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association. April 17, 1979. Available at: www.wpath.org/media/cms/Documents/History/Harry%20Benjamin/First%20HBIGDA%20Membership%20Request%20Letter%201979.pdf . Accessed February 11, 2021.

- Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, et al. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7. Int J Transgend . 2012;13(4):165-232.

- Arrillaga P. Onetime coal mining town bolstered by changing economy. Los Angeles Times . June 4, 2000. Available at: www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2000-jun-04-me-37512-story.html . Accessed February 11, 2021.

- James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi M. The Report of the 2015 Transgender Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Healthcare Equality, 2016. Available at: www.transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/USTS-Full-Report-FINAL.PDF . Accessed February 11, 2021.

- National LGBT Health Education Center. Creating a transgender health program at your health center: Planning to implementation. September 2018. Available at: www.lgbtqiahealtheducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Creating-a-Transgender-Health-Program.pdf . Accessed February 11, 2021.

- El-Hadi H, Stone J, Temple-Oberle C, Harrop AR. Gender-affirming surgery for transgender individuals: Perceived satisfaction and barriers to care. Plast Surg . 2018;26(4):263-268.

- Puckett JA, Cleary P, Rossman K, Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Barriers to gender-affirming care for transgender and gender nonconforming individuals. Sex Res Social Policy . 2018;15(1):48-59.

- Lichtenstein M, Stein L, Connolly E, et al. The Mount Sinai patient-centered preoperative criteria meant to optimize outcomes are less of a barrier to care than WPATH SOC 7 criteria before transgender-specific surgery. Transgend Health . 2020;5(3):166-172.

- Streed CG, Davis JA. Improving clinical education and training on sexual and gender minority health. Curr Sex Health Rep . 2018;10:273-280.

- Submit a Tip

- Subscribe News-Letter Weekly Leisure Weekly

- About Contact Staff Mission Statement Policies Professional Advisory Board

Hopkins Hospital: a history of sex reassignment

By RACHEL WITKIN | May 1, 2014

Editor’s note: this article makes several misleading claims. It does not properly contextualize psychologist John Money ’ s forced sexual reassignment surgery of David Reimer. It also implies that sexual reassignment surgery was introduced in the 1960s, though procedures took place earlier in the 1900s.

The News-Letter regrets these errors.

In 1965, the Hopkins Hospital became the first academic institution in the United States to perform sex reassignment surgeries. Now also known by names like genital reconstruction surgery and sex realignment surgery, the procedures were perceived as radical and attracted attention from The New York Times and tabloids alike. But they were conducted for experimental, not political, reasons. Regardless, as the first place in the country where doctors and researchers could go to learn about sex reassignment surgery, Hopkins became the model for other institutions. But in 1979, Hopkins stopped performing the surgeries and never resumed.

In the 1960s, the idea to attempt the procedures came primarily from psychologist John Money and surgeon Claude Migeon, who were already treating intersex children, who, often due to chromosome variations, possess genitalia that is neither typically male nor typically female. Money and Migeon were searching for a way to assign a gender to these children, and concluded that it would be easiest if they could do reconstructive surgery on the patients to make them appear female from the outside. At the time, the children usually didn’t undergo genetic testing, and the doctors wanted to see if they could be brought up female.

“[Money] raised the legitimate question: ‘Can gender identity be created essentially socially?’ ... Nurture trumping nature,” said Chester Schmidt, who performed psychiatric exams on the surgery candidates in the 60s and 70s.

This theory ended up backfiring on Money, most famously in the case of David Reimer, who was raised as a girl under the supervision of Money after a botched circumcision and later committed suicide after years of depression.

However, at the time, this research led Money to develop an interest in how gender identities were formed. He thought that performing surgery to match one’s sex to one’s gender identity could produce better results than just providing these patients with therapy.

“Money, in understanding that gender was — at least partially — socially constructed, was open to the fact that [transgender] women’s minds had been molded to become female, and if the mind could be manipulated, then so could the rest of the body,” Dana Beyer, Executive Director of Gender Rights Maryland, who came to Hopkins to consider the surgery in the 70s, wrote in an email to The News-Letter .

Surgeon Milton Edgerton, who was the head of the University’s plastic surgery unit, also took an interest in sex reassignment surgery after he encountered patients requesting genital surgery. In 2007, he told Baltimore Style : “I was puzzled by the problem and yet touched by the sincerity of the request.”

Edgerton’s curiosity and his plastic surgery experience, along with Money’s interest in psychology and Migeon’s knowledge of plastic surgery, allowed the three to form a surgery unit that incorporated other Hopkins surgeons at different times. With the University’s approval, they started performing sex reassignment surgeries and created the Gender Identity Clinic to investigate whether the surgeries were beneficial.

“This program, including the surgery, is investigational," plastic surgeon John Hoopes, who was the head of the Gender Identity Clinic, told The New York Times in 1966. “The most important result of our efforts will be to determine precisely what constitutes a transsexual and what makes him remain that way.”

To determine if a person was an acceptable candidate for surgery, patients underwent a psychiatric evaluation, took gender hormones and lived and dressed as their preferred gender. The surgery and hospital care cost around $1500 at the time, according to The New York Times .

Beyer found the screening process to be invasive when she came to Hopkins to consider the surgery. She first heard that Hopkins was performing sex reassignment surgeries when she was 14 and read about them in Time and Newsweek .

“That was the time that I finally was able to put a name on who I was and realized that something could be done,” she said. “That was a very important milestone in my consciousness, in understanding who I was.”

When Beyer arrived at Hopkins, the entrance forms she had to fill out were focused on sexuality instead of sexual identity. She says she felt as if they only wanted to consider hyper-feminine candidates for the surgery, so she decided not to stay. She had her surgery decades later in 2003 in Trinidad, Colo.

“It was so highly sexualized, which was not at all my experience, certainly not the reason I was going to Hopkins to consider transition, that I just got up and left, I didn’t want anything to do with it,” she said. “No one said this explicitly, but they certainly implied it, that the whole purpose of this was to get a vagina so you could be penetrated by a penis.”

Beyer thinks that it was very important that the transgender community had access to this program at the time. However, she thinks that the experimental nature of the program was detrimental to its longevity.

“It had negative consequences because when it was done it was clearly experimental,” she said. “Our opponents were able to use the experimental nature of the surgery in the 60s and the 70s against us.”

By the mid-70s, fewer patients were being operated on, and many changes were made to the surgery and psychiatry departments, according to Schmidt, who was also a founder of the Sexual Behaviors Consultation Unit (SBCU) at the time. The new department members were not as supportive of the surgeries.

In 1979, SBCU Chair Jon Meyer conducted a study comparing 29 patients who had the surgery and 21 who didn’t, and concluded that those who had the surgery were not more adjusted to society than those who did not have the surgery. Meyer told The New York Times in 1979: “My personal feeling is that surgery is not proper treatment for a psychiatric disorder, and it’s clear to me that these patients have severe psychological problems that don’t go away following surgery.”

After Meyer’s study was published, Paul McHugh, the Psychiatrist-in-Chief at Hopkins Hospital who never supported the University offering the surgeries according to Schmidt, shut the program down.

Meyer’s study came after a study conducted by Money, which concluded that all but one out of 24 patients were sure that they had made the right decision, 12 had improved their occupational status and 10 had married for the first time. Beyer believes that officials at Hopkins just wanted an excuse to end the program, so they cited Meyer’s study.

“The people at Hopkins who are naturally very conservative anyway … decided that they were embarrassed by this program and wanted to shut it down,” she said.

A 1979 New York Times article also states that not everyone was convinced by Meyer’s study and that other doctors claimed that it was “seriously flawed in its methods and statistics and draws unwarranted conclusions.”

However, McHugh says that it shouldn’t be surprising that Hopkins discontinued the surgeries, and that he still supports this decision today. He points to Meyer’s study as well as a 2011 Swedish study that states that the risk of suicide was higher for people who had the surgery versus the general population.

McHugh says that more research has to be conducted before a surgery with such a high risk should be performed, especially because he does not think the surgery is necessary.

“It’s remarkable when a biological male or female requests the ablation of their sexual reproductive organs when they are normal,” he said. “These are perfectly normal tissue. This is not pathology.”

Beyer, however, cites a study from 1992 that shows that 98.5 percent of patients who underwent male-to-female surgery and 99 percent of patients who underwent female-to-male surgery had no regrets.

“It was clear to me at the time that [McHugh] was conflating sexual orientation and the actual physical act with gender identity,” Beyer said.

However, she thinks that shutting down the surgeries at Hopkins actually helped more people gain access to them, because now the surgeries are privatized.

“Paul McHugh did the trans community a very big favor … Privatization [helps] far more people than the alternative of keeping it locked down in an academic institution which forced trans women to jump through many hoops.”

Twenty major medical institutions offered sex reassignment surgery at the time that Hopkins shut its program down, according to a 1979 AP article.

Though the surgeries at Hopkins ended in 1979, the University continued to study sexual and gender behavior. Today, the SBCU provides consultations for members of the transgender community interested in sex reassignment surgery, provides patients with hormones and refers patients to specialists for surgery.

The Hopkins Student Health and Wellness Center is also working toward providing transgender students necessary services as a plan benefit under the University’s insurance plan once the student health insurance plan switches carriers on Aug. 15.

“We are hopefully working towards getting hormones and other surgical options covered by the student health insurance,” Demere Woolway, director of LGBTQ Life at Hopkins, said. “We’ve done a number of trainings for the folks over in the Health Center both on the counseling side and on the medical side. So we’ve done some great work with them and I think they are in a good place to be welcoming and supportive of folks.”

Schmidt does ongoing work to provide the Hopkins population with transgender services, and says he would like for Hopkins to start performing sex reassignment surgeries again. But Chris Kraft, the current co-director of the SBCU, says that this is not feasible today, as no academic institution provides these surgeries since not enough people request them.

“It is unfortunate that no medical schools in the country have faculty who are trained or able to provide surgeries,” he wrote in an email to The News-Letter . “All the best surgeons work free-standing, away from medical schools. If we had surgeons who could provide the same quality services as the other surgeons in the country, then it would make sense to provide these services. Sadly, few physicians are willing to make gender surgery a priority in their careers because gender patients who go on to surgery are a very small population.”

Beyer, however, does not think that the transgender community needs Hopkins to reinstate its program, and that there are currently enough options available.

“We’re way, way past that,” she said. “It’s no longer the kind of procedure that needs an academic institution to perform research and development.”

Though she finds the way that Hopkins treated its sex reassignment patients in the 60s and 70s questionable, she thinks that the SBCU has been a great resource for the transgender community.

“Today those folks are wonderful people,” Beyer said. “They’re very helpful. They’re the go-to place up in Baltimore. They’ve done a lot of good for a lot of people. They’ve contributed politically as well to passage of gender identity legislation in Maryland and elsewhere.”

The Maryland Coalition for Trans Equality’s Donna Cartwright said that the transgender community does not have enough resources available to them. She said offering surgery at a nearby academic institution could provide more support to the community.

“Generally, the medical community needs to be better educated on trans health care and there should be greater availability [of sex reassignment surgery],” she said. “I think it would be good if there was an institution in the area that did provide health care, including surgery.”

Related Articles

Students voice discontent with University response to affirmative action ruling

SGA hosts public town hall to discuss racial diversity on campus

Hopkins students and student organizations reflect on the upcoming 2024 election

Please note All comments are eligible for publication in The News-Letter .

Editor's Picks

Antiguoko kikol elkartea: a cradle of soccer talent in the north of spain, aiming for the stars: hopsat’s mission to solar sailing, your stem degree alone is useless, tyler, the creator’s chromakopia prioritizes introspection over innovation, film and media studies faculty showcase highlights four labors of love, weekly rundown, events this weekend (nov. 1–3), science news in review: oct. 29, to watch and watch for: week of oct. 27, science news in review: oct. 23, hopkins sports in review (oct. 16–20), events this weekend (oct 18–20).

Be More Chill

Leisure interactive food map.

The News-Letter Print Locations

News-Letter Special Editions

- UK Politics

- News Videos

- Paris 2024 Olympics

- Rugby Union

- Sport Videos

- John Rentoul

- Mary Dejevsky

- Andrew Grice

- Sean O’Grady

- Photography

- Theatre & Dance

- Culture Videos

- Fitness & Wellbeing

- Food & Drink

- Health & Families

- Royal Family

- Electric Vehicles

- Car Insurance Deals

- Lifestyle Videos

- Home & Garden

- Broadband deals

- Fashion & Beauty

- Travel & Outdoors

- Sports & Fitness

- Hotel Reviews

- News & Advice

- Simon Calder

- Australia & New Zealand

- South America

- C. America & Caribbean

- Middle East

- Politics Explained

- News Analysis

- Today’s Edition

- Climate 100

- Sustainable Living

- Climate Videos

- Solar Panels

- Behind The Headlines

- On The Ground

- Decomplicated

- You Ask The Questions

- Binge Watch

- Travel Smart

- Watch on your TV

- Crosswords & Puzzles

- Most Commented

- Newsletters

- Ask Me Anything

- Virtual Events

- Wine Offers

- Betting Sites

- Casino Sites

Thank you for registering

Please refresh the page or navigate to another page on the site to be automatically logged in Please refresh your browser to be logged in

The French gynaecologist who turned Casablanca into the sex change capital of the world

The work of ‘celebrity’ gender reassignment surgeon dr georges burou, whose clients included the late, great jan morris, is still a defining debate of our age, writes oliver bennett.

Article bookmarked

Find your bookmarks in your Independent Premium section, under my profile

C asablanca is an anomaly in Morocco . Much of it is commercial, urban and Europeanised, with art deco parades, shopping centres and parks laid out in the early 20th century. Despite the towering Hassan II Mosque, the crashing Atlantic coast and a certain raffish appeal, it lacks the tourist-trapping atmospherics of Marrakesh and Fez.

But the “white city” set one marker in history – as a key location in the history of gender reassignment surgery, or GRS. From the 1950s to the ’70s, Casablanca became the fabled destination of people wishing to trans ition from male to female, courtesy of glamorous gynaecologist Dr Georges Burou – including Jan Morris , who died last week and who at 45 years old in 1972 went to see Dr Burou for GRS. Her account, in the 1974 book Conundrum , is a classic in its field, and introduced Britain to the idea of what was then known bluntly as a “sex change”.

In an admittedly small field, Dr Burou was arguably the first celebrity of GRS. “Arguably” because Burou had competition from US army veteran Stanley Biber, who from the late 1960s onwards turned Trinidad, Colorado, into the nominative “sex change capital of the world”, performing four sex reassignment surgery, or SRS (as it was then known), operations a day, while another contender was Elmer Belt, until the late 1960s was said to be the first surgeon to perform SRS in the US.

But Dr Burou had European fame and celebrity clients, and became well known in the UK in the 1960s and ’70s, with Casablanca becoming a byword for transgender individuals wishing to change gender, including Morris, model April Ashley in 1960, and singer and model Amanda Lear, whose surgery was said to have been carried out in 1964 and apocryphally paid for by her patron Salvador Dalì. It is said that Dr Burou’s fee was $1,250, which would be more or less $10,000 today – a bargain.

In recent years, the subject of GRS has become a huge and contentious part of public discourse – indeed, it’s no overstatement to say that it has become one of the primary ethical issues of the day. Because of that, it sometimes feels as if GRS is an issue that has landed in the last 10 years. But it has far deeper roots and in the modern era is thought to be about a century old. The first reports of GRS – although they are contested – are normally said to have originated in Germany in the 1920s, when male-to-female GRS was influenced by sex research pioneer Magnus Hirschfeld at Berlin’s Institute for Sexual Research during the 1920s and early 1930s.

There was also a centre in the UK where it found early fruition – the Charing Cross Hospital on Fulham Palace Road. Here, the most celebrated patient was Mary Edith Louise Weston, England’s best female shot putter between 1924 and 1930 and a leading javelin thrower in 1927. In 1936 Mary became Mark after two operations performed by South African surgeon Lennox Broster at Charing Cross and two months later married Alberta Bray in Plymouth. In a line that would hum with conflict were it on Twitter today, Broster said: “Mr Mark Weston, who was always brought up as a female, is male, and should continue life as such.”

Such liberalism was helped by a groundbreaking article in Physical Culture magazine of January 1937 by one Donald Furthman Wickets called “Can Sex in Humans be Changed”, citing both Weston and the Czechoslovakian athlete Zdenek, who won the 100 metres at the Olympics. “Sports writers called him ‘the fastest woman on legs’,” wrote Wickets, in another line that would occasion a contemporary Twitter-storm.

Controversies aside, their work paved the way for the post-war era; and Dr Burou himself. A maverick gynaecologist, the Frenchman had been bought up in Algeria where he had a medical practice but, with a touch of the renegade, was forced to leave after performing illegal abortions and was struck off by the French Order of Physicians.

Of course you can’t do an operation if it isn’t available. Let’s say it’s like wanting to fly but not being able to grow wings

A keen sailor, Burou settled on Morocco’s Atlantic coast, and landed at Parc Clinic near Avenue Hassan II in central Casablanca, where he then built up a reputation for abortions, IVF and, finally, SRS/GRS. Casablanca became the storied mothership for those who wanted to transition from male to female – then the most viable direction of travel, surgically-speaking.

Burou’s breakthrough in public consciousness occurred in 1956 when a Parisian singer at Le Carrousel club called Jacqueline Charlotte Dufresnoy, or Coccinelle, went to see him for GRS. With the door opened, news spread to the UK and April Ashley became Dr Burou’s ninth patient and the first Briton to have GRS in 1960.

His “one-stage” GRS was known in medical gobstopper language as “anteriorly pedicled penile skin flap inversion vaginoplasty”. This became the “gold standard of skin-lined vaginoplasty” with a so-called “neovagina” created between the rectum and prostate, lined with skin tissue taken from the penis and scrotum, completed with labia and clitoris.

Dr Burou, in a 1974 interview in Paris Match , described his work in the language of the time: “I started this speciality almost by accident, because a pretty woman came to see me,” he said. “In reality, it was a man, I only knew it afterwards, a sound engineer in Casablanca, 23 years old, dressed as a woman … with a lovely chest which he had obtained thanks to hormone bites.” The patient had told Dr Burou that he felt his body was an accident, and although the surgeon had apparently been unaware of the operation’s history, he went on to undertake a three-hour GRS operation, claiming afterwards that “I made her a real woman”.

The Parc Clinic then became the go-to place for male-to-female transition. By the 1970s, Dr Burou had performed between 800 and 3,000 such operations, though the true numbers are difficult to measure in a semi-clandestine milieu. Those seeking GRS with him had to put in the groundwork, find out the location of the clinic and deal with the considerable logistics.

There was also a significant risk. As April Ashley wrote about her decision to see Dr Burou in 1960: “In Paris, I debated with myself the decision to have a sex change. I knew I would be pioneering a dangerous operation. The doctor told me there was a 50-50 chance I would not come through. However, I knew I was a woman and that I could not live in a male body. I had no choice. I flew to Casablanca and the rest, as they say, is history.”

In Paris, I debated with myself the decision to have a sex change. I knew I would be pioneering a dangerous operation … However, I knew I was a woman and that I could not live in a male body. I had no choice

Over the years the cloak-and-dagger mist started to lift and Dr Burou became a medical celebrity, helped by the spirit of sexual freedom and fluidity that infused the late 1960s and ’70s. In February 1973, for example, he presented to the Medical Congress of Transsexuality at Stanford University in the US, followed by the International Congress of Sexology in Paris in 1974. Time magazine included him in a report about “prisoners of sex”. There was even an unsubstantiated rumour that one Michael Jackson had passed his way. The world was coming around to GRS, assisted by avant-garde medics like Harry Benjamin in the US, who changed medical attitudes by creating a distinction between gender identity and homosexuality: then assumed to be the cause of gender dysphoria, and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders changed so that homosexuality was not classified as a mental disorder in 1974, the same year as Morris’ Conundrum was published.

Even the puritanical UK saw powerful currents of change. The case of Corbett v Corbett in 1970, the divorce between April Ashley and her husband Arthur Corbett, saw the judge ruling that Ashley was a biological man and the marriage invalid, which caused a stir and fuelled the cause. In Conundrum , Jan Morris revealed that she had been refused GRS in the UK because of the pre-condition that she should divorce her wife, which she didn’t want to do. The academic Carol Riddell, also a British patient of Dr Burou’s in 1972, had faced a punitive waiting period in the UK. Their combined cases set a precedent that helped lead to 2004’s Gender Recognition Act, allowing people to change gender.

Now, Dr Burou’s work has found another historical moment. Dr Vincent Wong, a plastic surgeon working in the sexual dysmorphism field – particularly with feminisation and masculinisation in faces – has worked with several transitioning people including Talulah-Eve, the first transgender contestant on Britain’s Next Top Model , who said: “I knew how I felt in the inside, but I didn’t know how to project that on the outside.”

Dr Wong “dislikes the whole concept that GRS is something new”, and delivers lectures about its history, aiming to show that this transitioning is not some new fad. “The general public might see it as a hot topic but it’s evident that transgender people are not new,” he says. “The mismatch between the outer and inner person is not a trend. It’s been around since the beginning of time. But finally people are a bit more accepting.”

Prior to surgery being available, Wong believes, people would find other outlets, for example, by dressing differently. “What we call drag now has happened for a very long time,” he says. “But it has not been easy and in the past patients were seen as having serious mental health problems.” And while male-to-female reassignment was once more common, as with Dr Burou, Dr Wong says that female-to-male reassignment has now become more dominant and people “are making the decision a lot younger” – although he qualifies this with a certain “worry that the kids are truly questioning their gender or doing it because a friend has”.

Eric Plemons, a medical anthropologist at the University of Arizona and author of The Look of a Woman , has charted the growth of GRS, and notes how the way was paved by “mavericks such as Dr Burou and Biber”.

“Dr Burou was in north Africa , outside of Europe and the US, and therefore he worked in an area that was geographically as well as sociologically marginal,” says Plemons. “There was a kind of glamour there, but remember, it was highly risky. The loss of blood was immense and only in the microsurgery of the 1980s and beyond has it become safer.”

The vaginoplasty of Burou was more more easily undertaken than the phalloplasty of the female-to-male transition. Although this too has a surgical heritage dating back to pre-Second World War, it has lagged behind vaginoplasty – but again, has become easier since the 1980s. Such operations are not about demand but obtainability and viability, says Plemons: “Of course you can’t do an operation if it isn’t available. Let’s say it’s like wanting to fly but not being able to grow wings.”

The acceptance of the trans identity has been more complicated, says Plemons, himself female-to-male transgendered. “An anthropological view would be that the old ways of resource distribution have cleaved down male and female lines for so many years that without them a certain chaos ensues.” Perhaps we are witnessing that chaos at present, and in a similar spirit, Wong emphasises that transitioning isn’t itself clear-cut. “Transitioning isn’t a start and end point,” he says. “It’s a life long journey.”

Dr Burou, long keen on watersports, died in 1987 when his boat capsized in a storm off Pont Blondin, to the north of Casablanca. The maverick surgeon might have been astonished at how his operations, conceived in the absence of other opportunities, had become such a defining debate of our age. At the same time, he would sure have been pleased at how well it worked out for his most celebrated patient, the extraordinary writer Jan Morris.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Gender-affirming care has a long history in the US – and not just for transgender people

Associate Professor of History, Roanoke College

Disclosure statement

G. Samantha Rosenthal is co-founder of the Southwest Virginia LGBTQ+ History Project

View all partners

In 1976, a woman from Roanoke, Virginia, named Rhoda received a prescription for two drugs: estrogen and progestin. Twelve months later, a local reporter noted Rhoda’s surprisingly soft skin and visible breasts. He wrote that the drugs had made her “so completely female.”

Indeed, that was the point. The University of Virginia Medical Center in nearby Charlottesville had a clinic specifically for women like Rhoda. In fact, doctors there had been prescribing hormones and performing surgeries – what today we would call gender-affirming care – for years.

The founder of that clinic, Dr. Milton Edgerton , had cut his teeth caring for transgender people at Johns Hopkins University in the 1960s. There, he was part of a team that established the nation’s first university-based Gender Identity Clinic in 1966.

When politicians today refer to gender-affirming care as new, “ untested ” or “ experimental ,” they ignore the long history of transgender medicine in the United States.

It’s been nearly 60 years since the first transgender medical clinic opened in the U.S. , and 47 years since Rhoda started her hormone therapy. Understanding the history of these treatments in the U.S. can be a helpful guide for citizens and legislators in a year when a record number of bills in statehouses target the rights of transgender people.

Treating gender in every population

As a trans woman and a scholar of transgender history , I have spent much of the past decade studying these issues . I also take several pills each morning to maintain the proper hormonal balance in my body: spironolactone to suppress testosterone and estradiol to increase estrogen.

When I began HRT, or hormone replacement therapy, like many Americans I wasn’t aware that this treatment had been around for generations. What I was even more surprised to learn was that HRT is often prescribed to cisgender women – women who were assigned female at birth and raised their whole lives as women. In fact, many providers in my region already had a long record of prescribing hormones to cis women , primarily women experiencing menopause.

I also learned that gender-affirming hormone therapies have been prescribed to cisgender youths for generations – despite what contemporary politicians may think. Disability scholar Eli Clare has written of the history and continued practice of prescribing hormones to boys who are too short and girls who are too tall for what is considered a “normal” range for their gender. Because of binary gender norms that celebrate height in men and smallness in women, doctors, parents and ethicists have approved the use of hormonal therapies to make children conform to these gender stereotypes since at least the 1940s .

Clare describes a severely disabled young woman whose parents – with the approval of doctors and ethicists from their local children’s hospital – administered puberty blockers so that she would never grow into an adult. They deemed her mentally incapable of becoming a “real” woman.

The history of these treatments demonstrates that hormone therapies and puberty blockers have been used on cisgender children in this country – for better or for worse – with the goal of regulating the passage from girlhood to womanhood and from boyhood to manhood. Gender stereotypes concerning the presence or absence of secondary sex characteristics – too tall, too short, too much body hair – have all led parents and doctors to perform gender-affirming care on cisgender children.

For over half a century, legal and medical authorities in the U.S. have also approved and administered surgeries and hormone therapies to force the bodies of intersex children to conform to binary gender stereotypes. I myself had genital surgery in infancy to bring my anatomy into alignment with expectations for what a “male” body should look like. In most cases, intersex surgeries are unnecessary for the health or well-being of a child.

Historians such as Jules Gill-Peterson have shown that early advances in transgender medicine in this country are deeply interwoven with the nonconsensual treatment of intersex children . Doctors at Johns Hopkins and the University of Virginia practiced reconstructing the genitalia of intersex people before applying those same treatments on transgender patients.

Given these intertwined histories, I contend that the current political focus on prohibiting gender-affirming care for transgender people is evidence that opposition to these treatments is not about the safety of any specific medications or procedures, but rather their use specifically by transgender people.

How transgender people access care

Many transgender people in the U.S. have deeply complicated feelings about gender-affirming care. This complexity is a result of over half a century of transgender medicine and patient experiences in the U.S.

In Rhoda’s time, medical gatekeeping meant that she had to live “full time” as a woman and prove her suitability for gender-affirming care to a team of primarily white, cis male doctors before they would give her treatment. She had to mimic language about being “ born in the wrong body ” – language invented by cis doctors studying trans people, not by trans people themselves. She had to affirm she would be heterosexual and seek marriage and monogamy with a man. She could not be a lesbian or bisexual or promiscuous.

Many trans people still need to jump through similar hoops today to receive gender-affirming care. For example, a diagnosis of “ gender dysphoria ,” a designated mental disorder, is sometimes required before treatment. Many trans people argue that these preconditions for access to care should be removed because being trans is an identity and a lived experience, not a disorder.

Feminist activists in the 1970s also critiqued the role of medical authority in gender-affirming care. Writer Janice Raymond decried “ the transsexual empire ,” her term for the physicians, psychologists and other professionals who practice transgender medicine. Raymond argued that cis male doctors were making an army of trans women to satisfy the male gaze: promoting iterations of womanhood that reinforced sexist gender stereotypes, ultimately ushering in the displacement and eradication of the world’s “biological” women. The origins of today’s gender-critical, or trans-exclusionary radical feminist , movement are visible in Raymond’s words. But as trans scholar Sandy Stone wrote in her famous reply to Raymond , it’s not that trans women are unwilling dupes of cis male medical authority, but rather that we have to strategically perform our womanhood in certain ways to access the care and treatments we need.

The future of gender-affirming care

In many states, especially in the South, where I live, governors and legislatures are introducing bills to ban gender-affirming care – even for adults – in ignorance of history. The consequences of hurried legislation extend beyond trans people, because access to hormones and surgeries is a basic medical service many people may need to feel better in their body.

Prohibitions on hormone therapy and gender-related surgeries for minors could mean ending the same treatment options for cisgender children . The legal implications for intersex children may directly clash with proposed legislation in several states that aims to codify “male” and “female” as discrete biological sexes with certain anatomical features.

Prohibitions on hormone replacement therapy for adults could affect access to the same treatments for menopausal women or limit access to hormonal birth control. Prohibitions of gender-affirming surgeries could affect anyone’s ability to access a hysterectomy or a mastectomy . So-called cosmetic surgeries such as breast implants or reductions, and even facial feminization procedures such as lip fillers or Botox, could also come under question.

These are all different types of gender-affirming procedures. Are most Americans willing to live with this level of government intrusion into their bodily autonomy?

Almost every major medical organization in the U.S. has come out against new government restrictions on gender-affirming care because, as doctors and professionals, they know that these treatments are time-tested and safe . These treatments have histories reaching back over 50 years.

Trans and intersex people are important voices in this debate, because our bodies are the ones politicians opposing gender-affirming care most frequently treat as objects of ridicule and disgust . Legislators are developing policies about us despite the fact that most Americans say they do not even know a trans person .

But trans and intersex people know what it is like to have to fight to access the care and treatment we need. And we know the joy of finally feeling comfortable in our own skin and being able to affirm our gender on our own terms.

- Gender stereotypes

- Transgender

- Health care

- Gender dysphoria

- History of medicine

- Hormone therapy

- Johns Hopkins University

- Transgender rights

- Transgender health

- Trans rights

- LGBTQ history

- gatekeepers

- US health care

- Gender-affirming healthcare

- Trans healthcare

- Gender disparities

- Anti-trans legislation

- University of Virginia

- trans history

Commissioning Editor Nigeria

Subject Coordinator PCP2

Professor in Physiotherapy

Postdoctoral Research Associate

Editorial Internship

Introduction

The historic and cultural diversity of gender, biological underpinnings of gender identity, history of modern gender-affirming medical treatment, history of gender-affirming medical treatment in adolescents, changing prevalence of trans identities and the rise of nonbinary identification, legislative and social dynamics, conclusions, statement of ethics, conflict of interest statement, funding sources, author contributions, data availability statement, the evolution of adolescent gender-affirming care: an historical perspective.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Jeremi M. Carswell , Ximena Lopez , Stephen M. Rosenthal; The Evolution of Adolescent Gender-Affirming Care: An Historical Perspective. Horm Res Paediatr 29 November 2022; 95 (6): 649–656. https://doi.org/10.1159/000526721

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

While individuals have demonstrated gender diversity throughout history, the use of medication and/or surgery to bring a person’s physical sex characteristics into alignment with their gender identity is relatively recent, with origins in the first half of the 20th century. Adolescent gender-affirming care, however, did not emerge until the late 20th century and has been built upon pioneering work from the Netherlands, first published in 1998. Since that time, evolving protocols for gender-diverse adolescents have been incorporated into clinical practice guidelines and standards of care published by the Endocrine Society and World Professional Association for Transgender Health, respectively, and have been endorsed by major medical and mental health professional societies around the world. In addition, in recent decades, evidence has continued to emerge supporting the concept that gender identity is not simply a psychosocial construct but likely reflects a complex interplay of biological, environmental, and cultural factors. Notably, however, while there has been increased acceptance of gender diversity in some parts of the world, transgender adolescents and those who provide them with gender-affirming medical care, particularly in the USA, have been caught in the crosshairs of a culture war, with the risk of preventing access to care that published studies have indicated may be lifesaving. Despite such challenges and barriers to care, currently available evidence supports the benefits of an interdisciplinary model of gender-affirming medical care for transgender/gender-diverse adolescents. Further long-term safety and efficacy studies are needed to optimize such care.

The relatively recent recognition of diversity of “gender identity” – one’s inner sense of self as male or female or somewhere on the gender spectrum – in the current culture belies its long-standing presence in cultures diverse and ancient. “Transgender” (sometimes referred to as “gender incongruence”) is defined as a marked and persistent incongruence between an individual’s experienced gender and their sex designated at birth. Transgender is often used as an umbrella term to encompass all gender identities that are not the same as the birth-assigned gender (typically based on the sex designated at birth) but may also be used specifically for a binary gender identification.

As our understanding of gender has been evolving over time, so has the language used to describe gender. Throughout this manuscript, the authors have primarily used the terminology of the present day, though historical descriptions will contain language that is clearly outdated. We have chosen to use these terms only to maintain the historical perspective in this context.

Though it may seem that transgender as a concept is a recent phenomenon, there are both ancient and diverse examples that underscore the understanding that humans have experienced gender as beyond the set of cultural norms assigned to them based on their genitals. In Greek and Roman mythology, there are legends of deities who defy traditional concepts of gender; the most famous may be Hermaphroditus, a son born of Hermes and Aphrodite. When the nymph Salmacis fell in love with him, their forms became merged, with the god depicted as having male genitalia with breasts and a more feminine body shape [1, 2]. Norse mythology gives us the notorious shape and sex shifting Loki, who was known for his trickery, appearing at times in a female form when it suited his purpose [1]. Several Indigenous North American tribes have long-standing recognition and language for gender and/or sexual minority-identified individuals that often signified a third gender, or a combination of male and female. Though the designation and roles varied among tribes, the term “two-spirit” was coined in 1990 during the international LGBT Native American Gathering and attributed to Elder Maya Laramee [3, 4]. This term is not specific to any one tribe or any one group of individuals but encompasses any indigenous member with gender-diverse identification or same-sex attraction.

John Money, a New Zealand psychologist and faculty member in pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University beginning in the early 1950s, and co-founder of the Gender Identity Clinic at that university, promoted the concept that gender identity was influenced by “social learning and memory” in conjunction with biological factors [5]. However, a widely publicized case described in a book by John Colapinto published in 2000 lends strong support to the concept that gender identity is not primarily learned [6]. This book focused on a failed circumcision in an 8-month-old male resulting in loss of the penis, leading Money to advise the family to castrate the infant and raise him as a girl [6]. The child never accepted a female gender identity, became severely depressed, and changed gender to male during adolescence. He later committed suicide [6]. In subsequent years, evidence in support of biological underpinnings to gender identity development has continued to emerge, derived primarily from three biomedical disciplines: genetics, endocrinology, and neurobiology [7].

Starting in the late 1970s, heritability of being transgender was suggested from studies describing concordance of gender identity in monozygotic twin pairs and in father-son and brother-sister pairs [8, 9]. In the largest twin study evaluating gender identity, in which at least one member of a twin pair was transgender, there was a much greater likelihood that the other member of the twin pair was also transgender if they were identical versus nonidentical (but same sex) twins [ 10 ]. Attempts to identify polymorphisms in candidate genes that might be more prevalent in transgender versus cisgender individuals have been inconsistent. In particular, a 2009 study from Japan did not find any significant associations of transsexualism with polymorphisms in five candidate genes (encoding the androgen receptor, CYP19, ER-alpha, ER-beta, and the progesterone receptor) [ 11 ]. However, a 2019 study in 380 transgender women and 344 cisgender male controls demonstrated an over-representation of several allele combinations involving the androgen receptor in transgender women [ 12 ]. A subsequent study using whole-exome sequencing in a relatively small number of transgender males ( n = 13) and transgender females ( n = 17) demonstrated 21 variants in 19 genes that were associated with previously described estrogen receptor-activated pathways of sexually dimorphic brain development [ 13 ]. An association between polymorphisms in the estrogen receptor alpha gene promoter and a transgender male identity has also been reported [ 14 ].

The vast majority of transgender individuals do not have an intersex condition or any associated abnormality in sex steroid production or responsiveness [7]. However, studies in a variety of intersex conditions have informed our understanding of the potential role of hormones, particularly prenatal and early postnatal androgens, in gender identity development [7]. For example, several studies of 46,XX individuals with virilizing congenital adrenal hyperplasia caused by 21-hydroxylase deficiency demonstrated a greater prevalence of a transgender identity outcome (female to male) compared to the general population [ 15-17 ]. One such study published in 2006 demonstrated a relationship between severity of congenital adrenal hyperplasia and gender identity outcome, where 7% of patients with the severe salt-wasting form had gender dysphoria or a male gender identity, while no gender dysphoria was seen in any of the less severely affected individuals [ 16 ]. Studies in a variety of other hormonal and nonhormonal intersex conditions support a role of prenatal and/or postnatal androgens in gender identity development [7]. However, in 2011, a case report in a 46,XY individual with complete androgen insensitivity and a male gender identity challenged the concept that androgen receptor signaling is required for male gender identity development [ 18 ].

Neuroimaging studies that aim to understand the neurobiology of gender identity indicate that some sexually dimorphic brain structures are more closely aligned with gender identity than with physical sex characteristics in transgender adults prior to treatment with gender-affirming hormones [ 19-21 ]. A similar trend was reported in studies of gray matter in youth with gender dysphoria [ 22 ]. In 2021, an MRI study in transgender adults, also prior to treatment with gender-affirming sex hormones, found that transgender people have a unique brain phenotype “rather than being merely shifted towards either end of the male-female spectrum” [ 23 ]. Notably, in both transgender adolescents and adults, several functional brain studies looking at responses to odorous compounds or mental rotation tasks demonstrated that patterns typically observed to be sexually dimorphic were more closely aligned with gender identity than with physical sex characteristics, even before treatment with gender-affirming sex hormones [ 24-26 ].

Though individuals have demonstrated gender diversity throughout history, the use of medication and/or surgery is relatively recent with origins in Germany in the first half of the 20th century and is credited to the pioneering work of Magnus Hirschfeld. The institution he founded, “Institut für Sexualwissenschaft (the Institute for Sexual Science)” in Berlin (1922), paved the way for the use of hormones and surgery [ 27 ]. In Hirschfeld’s study of what he named “sexual intermediaries,” he recognized that people may be born with a nature contrary to their assigned gender. In cases where the desire to live as the opposite sex was strong, he thought science ought to provide a means of transition. Innovative for his time, he argued that a person may be born with characteristics that did not fit into heterosexual or binary categories and supported the idea that a “third sex” existed naturally [ 27 ]. The first documented case of genital surgery was performed at the institute on Dorchen Richter in 1922 with orchiectomy and then 1931 with penectomy and vaginoplasty [ 27, 28 ]. Notable patients, including Lili Elbe (born Einar Wegener), the patient on whom the movie “The Danish Girl” is based, underwent a series of operations including transplant of both ovaries and a uterus [ 29 ].

This clinic would be a century old if it had not fallen victim to Nazi ideology and Hitler’s mission to rid Germany of Lebensunwertes Leben, or “lives unworthy of living.” What began as a sterilization program ultimately led to the extermination of millions of Jews, Gypsies, Soviet, and Polish citizens, as well as homosexuals and transgender people. When the Nazis came for the institute in 1933, Hirschfeld had fled to France. Troops swarmed the building and created a bonfire that engulfed more than 20,000 of his books, some of them rare copies that had helped provide a history for transgender people [ 27 ].

In the 1950s, German-American physician Harry Benjamin (1885–1986) introduced the term “transsexuality,” defining a “transsexual” person as someone who identifies in opposition to their “biological sex” [ 30 ]. Harry Benjamin graduated cum laude from medical school in Tübingen, Germany, in 1912. He moved to New York City in 1914 to study tuberculosis, but over time, he became known as a geriatrician, endocrinologist, and sexologist [ 31 ]. He did not treat his first transgender patient until he was in his 60s, and his colleagues described him as follows: “Being a true physician, Benjamin treated all these patients as people and by respectfully listening to each individual voice, he learned from them what gender dysphoria was about” [ 32 ]. Notably, he did not describe “transsexualism” as a psychological problem, but as a biological condition that could be treated with hormone or surgical therapy [ 31 ]. He treated over 1,500 patients, and in 1966, he published the first medical textbook in this field, “The Transsexual Phenomenon” [ 33 ]. His work was very influential, and he became known as “The Father of Transsexualism” [ 31, 32 ].

Following World War II, gender-affirming treatment in the USA was limited to wealthy patients who could afford to travel to Europe, though they did so at great risk given the laws in several states outlawing “cross-dressing” [ 34 ]. Christine Jorgensen (1926–1989) brought visibility to transgender patients, having undergone medical and surgical transition in Europe after she had served time in the US military as a male [ 35 ].

Influenced by Dr. Benjamin Harris’ “The Transsexual Phenomenon” [ 33 ], Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore became the first academic institution in the USA to offer gender-affirming surgery [ 36 ]. Soon after, at least another 8 academic institutions opened transgender programs throughout the 1960–1970s (University of Minnesota, University of Washington, Northwestern/Cook County Health in Chicago, Stanford University, Cleveland Clinic, University of Colorado, Baptist Medical Center in Oklahoma City, and Washington University in St. Louis) [ 37 ].

Toward the end of the 1970s, however, most transgender programs closed access to new patients. These closures were done quietly out of public view, and the causes were often not disclosed [ 37 ]. At Johns Hopkins Hospital, Paul McHugh became the Chair of Psychiatry in 1975. From the moment he was hired, McHugh openly stated he intended to stop gender-affirming surgery at this hospital [ 38 ]. Under his leadership, another Johns Hopkins psychiatrist, Dr. Jon Meyer, published a study of 50 patients which concluded that gender-affirming surgery did not provide “objective” benefit for transgender individuals [ 39 ]. This publication led to the sudden closure of the clinic in 1979 [ 36 ]. Interestingly, John Money, who believed that gender could be learned and who co-founded the Johns Hopkins gender clinic, publicly expressed opposition to Meyer’s conclusions of his study [ 36 ].

The program at the Baptist Medical Center in Oklahoma City had been functioning since 1973. However, in 1977, its existence was brought to the attention of the Board of Directors of the Baptist General Convention of Oklahoma. This led to a 54-2 vote by the Board of Directors at the Baptist Medical Center to close the program. Physicians who passionately advocated to continue this practice issued a joint statement saying, “If Jesus Christ were alive today, undoubtedly he would render help and comfort to the transsexual” [ 37 ].

It is thought that publicity around the Meyer paper [ 39 ] from Johns Hopkins played a role in an escalation of closure of other clinics [ 37 ]. Despite these closures, academic interest in the field led to the foundation of the Harry Benjamin Gender Dysphoria Association in 1979 [ 40 ]. This association had the goal of organizing professionals who were interested in the “study and care of transsexualism and gender dysphoria.” It has since been renamed the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) and has evolved into a large international multidisciplinary organization that provides Standards of Care for the treatment of transgender/gender-diverse (TGD) adolescents and adults [ 41 ].

In 1980, “transsexualism” and “gender identity disorder of childhood” were both recognized as illnesses in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [ 42 ]. In 2013, the term “gender identity disorder” was replaced by “gender dysphoria in children” and “gender dysphoria in adolescents and adults” to diagnose and treat those transgender individuals who felt distress at the mismatch between their gender identities and their bodies, with the American Psychiatric Association stating that “it is important to note that gender nonconformity is not in itself a mental disorder” [ 43 ].

In 2019, the World Health Organization International Classification of Diseases version 11 replaced International Classification of Diseases-10’s “transsexualism” and “gender identity disorder of children” with “gender incongruence of adolescence and adulthood” and “gender incongruence of childhood,” respectively [ 44 ]. Gender incongruence was moved out of the “Mental and behavioral disorders” chapter into a new chapter, entitled “Conditions related to sexual health” [ 44 ]. This reflects current perspective that TGD identities are not mental health illnesses and that classifying them as such can cause significant stigma.

Providers in the Netherlands recognized the importance of preventing progression of a gender incongruent puberty by using a gonadotropin hormone-releasing hormone analog (GnRHa) followed by treatment with either testosterone or estrogen to bring physical characteristics into alignment with a patient’s gender identity [ 45, 46 ]. This approach was first published by Drs. Cohen-Kettenis and van Goozen in 1998 in a case report of an adolescent treated with GnRHa by Dr. Henriette A. Delemarre-van de Waal (though not named in the publication) (Dr. Sabine E. Hannema , personal communication) [ 47 ]. Under the direction of Dr. Peggy Cohen-Kettenis, the first program geared to treating adolescents with gender dysphoria was established in the Netherlands [ 45 ]. Initially based on the guidelines of adult transgender treatment established by the Harry Benjamin Society and adapted to adolescents, patients first underwent comprehensive psychological assessment to establish a diagnosis of gender dysphoria (then called “gender identity disorder”) and then initiated treatment with GnRH agonists (GnRHa) typically at Tanner 2–3 to pause pubertal development [ 45, 46 ]. The time spent under pubertal suppression would be used to further explore gender identity prior to committing to either estrogen or testosterone and their physical effects. This intervention with a GnRHa would also be somewhat of a diagnostic aid in that if it eased the distress; it was reasonable to correlate the distress with gender dysphoria as a primary cause. This was followed by hormone therapy around age of 16 years and then gender-affirming genital surgery at 18 years or later [ 45, 46, 48 ]. The “Dutch Protocol” [ 49 ] was adapted by practitioners internationally, though it was not until pediatric endocrinologist and adolescent medicine pediatrician Dr. Norman Spack , having traveled to Amsterdam to observe the clinic there, established the first formal US program geared specifically to transgender adolescents at Boston Children’s Hospital: the Gender Management (subsequently replaced with Multispecialty) Service program in 2007 [ 50 ]. It should be noted that adolescents there and elsewhere across the USA had been treated outside of a structured program [ 50 ]. Clinical protocols at Gender Management Service were derived from direct observation, adaptation of the Dutch program, and a May 2005 consensus meeting (the Gender Identity Research and Education Society) and expanded upon previous guidelines from the Standards of Care of the WPATH and those from the Royal College of Psychiatrists [ 46, 51, 52 ].