- Research note

- Open access

- Published: 03 June 2019

Premarital sexual practice and associated factors among high school youths in Debretabor town, South Gondar zone, North West Ethiopia, 2017

- Wondmnew Lakew Arega 1 ,

- Taye Abuhay Zewale 2 &

- Kassawmar Angaw Bogale 3

BMC Research Notes volume 12 , Article number: 314 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

80k Accesses

15 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

Premarital sex is voluntary sexual intercourse between unmarried persons. Prevalence and factors associated with premarital sexual practice in the study area are lacking. Thus, the aims of this study were to determine the prevalence and to identify factors associated with premarital sexual practice among Debretabor high school youths.

The prevalence of premarital sex among Debretabor town high school youths was 22.5% of which 63.9% of them were males. Among those high school youths, the majority (60.2%) had their first sexual intercourse at the age of 15–19 years. The main reason for initiation of sexual intercourse was due to fell in love which accounts 48.1%, followed by sexual desire 22.2%. Predictors that are risk for premarital sex were youths who did not attend religious education [AOR = 7.4, 95% CI (3.32, 16.43)], having boy or girl friends [AOR = 9.66, 95% CI (4.80, 19.43)], drinking alcohol every day [AOR = 9.43, 95% CI (2.86, 31.14)] and less than twice a week [AOR = 2.52, 95% CI (1.22, 5.21)], watching pornography film [AOR = 5.15, 95% CI (2.56, 10.37)] and youths came from rural residing families [AOR = 0.51, 95% CI (0.27, 0.96)].

Introduction

Youths are in a state of rapid physical and psychological change. They have curiosity and urge to experience new phenomena [ 1 ]. Nevertheless, youths are exposed to different circumstance like fears, worries and different desires, they feel shame to get advice and guidance from their parents and elders [ 2 ]. Over a life cycle approach, youths and their communities need to know about reproductive health so that, they can make informed decisions about their reproductive health and sexuality [ 3 , 4 ]. Premarital sex, defined as voluntary sexual intercourse between unmarried persons, is increasing worldwide [ 5 ]. It is unsafe because, most youths have no enough awareness on how to prevent and how to get guidance services on reproductive anatomy, physiology, sexually transmitted infection (STI), and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) [ 6 , 7 ]. As a result, they are exposed to serious problems including premarital sex with its consequences and emotional scar [ 8 , 9 ].

Though, schools are institutions where sufficient information and formal educations are provided to youths, premarital sexual practice among high school youths have been increased worldwide [ 10 ]. Globally, 35.3 million people live with HIV/AIDS of which youths account 2.1 million. Among 2.3 million new HIV infections, youths (15–24 years) account more than half [ 7 ].

Illegal abortions, risk of HIV infections and school dropout are the bad consequences of pre-marital sex in sub-Saharan Africa [ 11 ]. Up to 25% of 15–19 years, old youth’s exercised sex before age 15. In Ethiopia, the prevalence of premarital sex is increasing [ 12 , 13 , 14 ]. A study conducted in Eastern part of Ethiopia and Lalibela Town reported that above one-fourth of the school youths were exposed to premarital sex [ 12 , 15 ]. Another study which is done in west Shoa Zone reported that about 60% of high school youths were exercised premarital sex [ 9 ]. Different scholars identified inconsistent factors which were positively or negatively associated with premarital sexual practice. Some of these factors includes age of students, sex, residence, educational level, peer pressure, having pocket money, substance use, alcohol drink, watching pornography movie, living arrangement, discussion with parents about sexual issues, having peers who are experienced sex and fall in love and access religious and life skill education [ 9 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ].

According to Debretabor district health office report sexually transmitted diseases, abortion and unwanted pregnancy are high in the study area among youths [ 18 ]. However, prevalence of premarital sexual practice and its associated factors among high school youths (grade 9th to grade 12th) in the study area was not dealt yet. Thus, this study aimed to determine premarital sexual practices and associated factors among high school youths in Debretabor town, south Gondar, Ethiopia.

Study design and setting

School based cross-sectional study design was conducted from September 18 to October 16, 2017, among high school youths in Debretabor town, South Gondar zone, Ethiopia. Debretabor town is located at 667 km from Addis Ababa, capital city of Ethiopia and has three high schools. The total numbers of high school youths in the study area by the year 2017 were 8892 (5220 females and 3672 males) [ 18 ].

Source population

The source population was all high school youths who were residing in Debretabor town and its surrounding rural Kebeles.

Study population

The study population was all high-school youths aged 15 to 24 years that were enrolled as a regular day-time student in 2017.

Inclusion criteria

All secondary school youths aged 15–24 attending regular class in Debretabor town during data collection period were included in the study.

Exclusion criterion

Married high school youths were excluded.

Sample size determination

Sample size was calculated using a single population proportion formula designated as \({\text{n}} = \frac{{(Z_{\alpha /2)}^{2} p\left( {1 - p} \right)}}{{d^{2} }}\) based on the assumptions of P -value = 0.25 which was the proportion of premarital sex among in-school youths in Jimma [ 19 ], a 95% confidence level, 4% margin of error (d) and 10% non-response rate. Accordingly, the total sample size calculated was 497.

Sampling procedure

All the high schools in the town were included in the study, and total sample size was proportionally allocated to each school. The lists of youths were obtained from the respective school registrar. Then, the study participants from each school were selected by computer generated simple random sampling technique after proportional allocation to their grade level.

Data collection

Pre-tested, self-administered structured Amharic (local language) questionnaire was used to collect the data. The questionnaire was pre-tested on 10% of the study participants at Alem-ber high school, which has the same setup to the study area, found in South Gondar zone. The questionnaire was amended according to the finding in the pretest before the distributions of final questionnaires. Training was given for data collectors and supervisors. Before the participants filled the questionnaires, the trained data collector gave orientation to youths regarding the aim of the study, the content of the questionnaire, the issue of confidentiality and respondents rights. Moreover, trained data collectors were involved in taking consents from participants and gathering filled questionnaires. However, data collectors were not present when the participants were filling the questionnaire.

The study used premarital sex practice as dependent variable and Socio-demographic Characteristics of youths and parents (age, sex, education level, religion, pocket money living arrangement, parental education, parental occupation, sexual issue discussion with parents), risk behavior and peer pressure (chat chewing, alcohol drinking, cigarette smoking, watching pornography, Peer friend initiation of sex) and history of partner hood, demand for condom utilization (number of partners, having the boy/girlfriend, condom utilization) as independent variable.

Data management and analysis

The data were entered using Epi-info version 7.2.1 and exported to SPSS version 23 for analysis. Descriptive statistics like frequency, percentage and standard deviation was computed. Binary logistics regression model was applied to identify determinant factors related premarital sexual practice. Variables with P value less than 0.25 on bi-variate analysis were entered to multi-variate analysis. 95% confidence interval was used to identify associated factors in multi-variable binary logistic regression model. Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness of the model fit was checked and analysis was done by entering procedure.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents

Four hundred eighty high school youths were filled the questionnaire making a response rate of 96.6%. From the total respondents, more than half (53.8%) of them were females. Majority (71.2%) youths age were from 15 to 19 years. The average age and standard deviation of respondents were 17 and 1.29 years respectively. Larger proportion (35.8%) of the participants were grade nine students. The majority (97.5%) of the respondents were Orthodox Christians. Only 23.3% of in school youths had pocket money, about 89% of youths were living with their parents and attending religious services. Moreover, above half (61%) of the youths didn’t discuss about sexual issues with their parents (Table 1 ).

Sexual characteristics and risk behavior of respondents

From all respondents, 22.5% have had premarital sexual intercourse at the time of the survey, of which 63.9% were males and 60.2% had their first sexual intercourse at the age of 15–19 years. The main reason for initiation of sexual intercourse was due to fell in love which accounts 48.1%, followed by sexual desire 22.2%.

Concerning the number of sexual partners, majority (84.3%) of students have had sex with one partner and about 58% of the them were used condom during sexual intercourse. Coming to risky behavior, 28.1% of the youths drunk alcohol, 16.2% watched pornography and 2.7% chewed khat. About 61% of youths who watched pornography film were exposed to premarital sex (Table 2 ).

Factors associated with premarital sexual practice among high school youths in Debretabor town, 2017

The Logistic regression analysis showed that premarital sexual practice among youths who did not attend religious education was 7.4 times more likely exposed to premarital sex as compared to the counterpart [AOR = 7.4, 95% CI (3.32, 16.43)]. Similarly, youths who had a boy or a girl friend were 9.66 times more likely to start premarital sex than those who didn’t have a boy or a girl [AOR = 9.66, 95% CI (4.80, 19.43)]. Youths who were drinking alcohol every day and less than twice a week were 9.43 times [AOR = 9.43, 95% CI (2.86, 31.14)] and 2.52 times [AOR = 2.52, 95% CI (1.22, 5.21)] more likely engaged in premarital sex practice respectively as compared to those who did not drink alcohol. Students who watched pornography film were 5.15 times more likely practiced premarital sex as compared to those who didn’t watch pornography film [AOR = 5.15, 95% CI (2.56, 10.37)]. But it was found to be less likely among urban youths resident family as compared with youths who came from rural resident families (Table 3 ).

Premarital sexual practice of high school youths in this study was 22.5% (CI: 19.0, 26.5). This finding was in line with a study conducted in Nekemtie town (21.5%) [ 20 ], in Jimma (21%) [ 19 ] and school youths in Alamata (21.1%) [ 21 ]. However, it was higher than in Coast Province, Kenya youths (14.9%) [ 22 ], and Robit high school youths (14.9%) [ 10 ]. The difference might be as a result of sample size, coast province; Kenya used existing data available from Kenya Global School Based Health Survey (GSHS) which was national study. So it could be more precise as compared with this study. In addition, there might be socio-cultural differences in community among study areas.

But this finding was lower than in-school youths in Ghana (42%) [ 23 ], in Jimma (28.5%) [ 24 ] in Eastern Ethiopia (24.8%) [ 12 ] and in Debremarkos high school youths (37.5% [ 25 ]. The variation may be due to difference in periods of the study (2011–2014), showing a changing and improving trend in easiness of reporting sexual matters and increasing premarital sexual awareness from time to time [ 7 , 26 ]. The difference might also be due to variations on the prevalence of risky sexual behavior.

This study also found that those youths who didn’t attend religious education were more likely exposed to premarital sex as compared with their counter parts. It is in agreement with studies conducted in Bahir Dar City [ 14 ] and Mizan Aman [ 27 ]. The possible reason could be religious institutions strongly thought youths to be abstained until marriage.

High School youths who have a boyfriend or girlfriend were more likely to have premarital sexual intercourse than those who don’t. There were similar reports in Alamata [ 28 ], and Nekemt towns [ 20 ]. This could be due to the pressure from their boy/girl friend to have sexual practice.

Youths who drunk alcohol were engaged in premarital sexual practice as compared to their counterparts. This finding is the same as the studies done in South West [ 27 ] and Western Ethiopia [ 29 ]. The possible explanation might be, when youths drink alcohol, his/her ability of self-controlling decrease and this may expose to premarital sex.

Students who watched pornography film were more likely practiced premarital sex as compared to those who didn’t. There is similar finding in Shendi Town [ 13 ] and Northern Ethiopia [ 7 ]. The possible reason could be pornography film leads youths physiological and psychological motive for sexual intercourse.

Youths from rural family residents were more exposed to premarital sex urban youths. This is not in agreement with other studies [ 7 , 21 , 28 , 30 , 31 ]. This difference might be due to low parental control of rural youths as they lived with rented rooms, exposed to exercising sexual issues freely.

Conclusions

Significant numbers of high school youths were engaged in sexual practice before marriage. Not attending religious education, have a boy/girlfriend, watching pornography film, alcohol drinkers and came from rural residing families were identified risk factors. So, the school community and respective health sector need to establish and strengthen school health program and school clubs to give awareness about identified risks of premarital sex. In addition family should link their youths to religious education in parallel to formal school education.

Limitation of the study

Since the nature of this study is sensitive, reporting errors and biases can’t be controlled. In addition as this study used only quantitative data, the behavioral related information might be missed. Since the questionnaire was self-administered, lack of control over the responses rate, no control over who filled the questionnaires and questions may be miss-understood so that the true impression of the participants may not be gathered.

Availability of data and materials

All the data sets used for this study are available from the corresponding author and can be given with a reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

adjusted odds ratio

confidence interval

Ethiopian calendar

Demographic Health Survey

Ethiopia Demographic Health Survey

standard deviation

Bachelor of Science

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Masters of Public Health

Statistical Package for Social Science

sexually transmitted infection

World Health Organization

Global School Based Health Survey

Lewis J. The physiological and psychological development of the adolescent. 27:2013. http://teachersinstitute.yale.edu/curriculum/units/1991/5/91.05.07.x.html . Accessed Apr 2007

Organization WH. Sexual health, human rights and the law. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

Google Scholar

Baryamutuma R, Baingana F. Sexual, reproductive health needs and rights of young people with perinatally acquired HIV in Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2011;11(2):211–8.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Brown A, Jejeebhoy SJ, Shah I, Yount KM. Sexual relations among young people in developing countries: evidence from WHO case studies. Occasional Paper. 2001;4

Shahid KH, AH SH, Wahab HA. Adolescents and premarital sex: perspectives from family ecological context. Int J Stud Child Women Elderly Disabled 2017;1

Abdissa B, Addisie M, Seifu W. Premarital Sexual practices, consequences and associated factors among regular undergraduate female students in Ambo University, Oromia Regional State, Central Ethiopia, 2015. Health Sci J. 2017;11(1):1.

Article Google Scholar

Habtamu M, Direslgne M, Hailu F. Assessment of time of sexual initiation and its associated factors among students in Northwest Ethiopia. Sci J Public Health. 2015;3(1):10–8.

Beyene AS, Seid AM. Prevalence of premarital sex and associated factors among out-of-school youths (aged 15–24) in Yabello town, Southern Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. Pharm Innovation. 2014;3(10, Part A):10.

Endazenaw G, Abebe M. Assessment of premarital sexual practices and determinant factors among high school students in West Shoa Zone, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. Sci J Public Health. 2015;3(2):229–36.

Alebachew FM. The prevalence of pre-marital sexual practice and its contributing factors in robit high school students science publishing group. 2016;1(1):1–6.

Gage AJ, Meekers D. Sexual activity before marriage in sub-Saharan Africa. Soc Biol. 1994;41(1–2):44–60.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Oljira L, Berhane Y, Worku A. Pre-marital sexual debut and its associated factors among in-school adolescents in eastern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):375.

Bogale A, Seme A. Premarital sexual practices and its predictors among in-school youths of shendi town, west Gojjam zone, North Western Ethiopia. Reprod Health. 2014;11(1):49.

Mulugeta Y, Berhane Y. Factors associated with pre-marital sexual debut among unmarried high school female students in bahir Dar town, Ethiopia: cross-sectional study. Reprod Health. 2014;11(1):40.

Desale AY, Argaw MD, Yalew AW. Prevalence and associated factors of risky sexual Behaviours among in-school youth in Lalibela town, north Wollo zone, Amhara regional sate. Ethiop Cross Sect Study Des Sci. 2016;4(1):57–64.

Dadi AF, Teklu FG. Risky sexual behavior and associated factors among grade 9–12 students in Humera secondary school, western zone of Tigray, NW Ethiopia, 2014. Sci J Public Health. 2014;2(5):410–6.

Seme A, Wirtu D. Premarital sexual practice among school adolescents in Nekemte Town, East Wollega. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2008;22(2):167–73.

office; Dte. Total numbers of high school students in Debretabor town. Debretabor: Debertabor Town Educaion Office; 2017.

Taye A, Asmare I. Prevalence of premarital sexual practice and associated factors among adolescents of Jimma Preparatory School Oromia Region, South West Ethiopia. J Nurs Care. 2016;5(2):353.

Seme A, Wirtu D. Premarital sexual practice among in-school adolescents in Nekemtie town. Ethiop j Health Dev. 2006;22(2):167–73.

Kassa GM, Woldemariam EB, Moges NA. Prevalence of premarital sexual practice and associated factors among alamata high school and preparatory school adolescents, Northern Ethiopia. Glob J Med Res 2014.

Rudatsikira E, Ogwell A, Siziya S, Muula A. Prevalence of sexual intercourse among school-going adolescents in Coast Province, Kenya. Tanzania J Health Res. 2007;9(3):159–65.

CAS Google Scholar

Dapaah JM, Appiah SCY, Amankwaa A, Ohene LR. Knowledge about sexual and reproductive health services and practice of what is known among Ghanaian Youth, a mixed method approach. Adv Sex Med. 2016;06(01):63086.

Abebe M, Tsion A, Netsanet F. Living with parents and risky sexual behaviors among preparatory school students in Jimma zone, South west Ethiopia. Afr Health Sci. 2013;13(2):498–506.

Kassa GM, Tsegay G, Abebe N, Bogale W, Tadesse T, Amare D, et al. Early Sexual Initiation and Associated Factors among Debre Markos University Students, North West Ethiopia. Science. 2015;4(5):80–5.

Oljira L, Berhane Y, Worku A. Pre-marital sexual debut and its associated factors among in-school adolescents in eastern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:375.

Meleko A, Mitiku K, Kebede G, Muse M, Moloro N. Magnitude of Pre-marital Sexual Practice and its Associated Factors among Mizan Preparatory School Students in Mizan Aman Town, South West Ethiopia. J Community Med Health Educ. 2017;7:539. https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-0711.1000539 .

Kassa GM, Woldemariam EB, Moges NA. Prevalence of premarital sexual practice and associated factors among alamata high school and preparatory school adolescents, Northern Ethiopia. Glob J Med Res. 2014;14(3).

Negeri EL. Assessment of risky sexual behaviors and risk perception among youths in Western Ethiopia: the influences of family and peers: a comparative cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):301.

Taye A, Asmare I. Prevalence of premarital sexual practice and associated factors among adolescents of jimma preparatory school Oromia Region, South West Ethiopia. J Nurs Care. 2016. https://doi.org/10.4172/2167-1168.1000332 .

Tekletsadik E, Shaweno D, Daka D. Prevalence, associated risk factors and consquences of premarital sex among female students in aletawondo highschool, Sidama zone, Ethiopia. J Public Health Epidemiol. 2014;6(7):216–22.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The researchers would like to thank Bahir-Dar University, College of Medicine and health Science for permitting to conduct this research and Debretabor town education offices and the respective staffs for providing the required information on time and their cooperativeness for the study. At last but not least, our gratefulness thanks go to the data collectors and the study participants.

Not applicable, there was no sources of funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Reproductive Health, School of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Bahir-Dar University, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia

Wondmnew Lakew Arega

Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Bahir-Dar University, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia

Taye Abuhay Zewale

Kassawmar Angaw Bogale

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

WLA conceptualization of the study, designed the study, collected data, drafts the analysis, interpreted the data and drafts the manuscript. TAZ designs the work, enter the data and analyze using software, interpretation of results as well as critical review of the manuscript. KAB Participated in design the study, drafting the manuscript and subsequent review of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Taye Abuhay Zewale .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of College of Medicine and Health Sciences at Bahir Dar University with reference number EPB/110/2017. Written permission letter was obtained from all concerned authorities. Written consents from parents of school youths were collected and verbal consent from each participant was obtained after explaining the purpose of the study. The right of participants to refuse or not to respond to questions if, they don’t feel comfortable with or discontinue participation at any time was ensured. Confidentiality was kept at each step of the data collection.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Arega, W.L., Zewale, T.A. & Bogale, K.A. Premarital sexual practice and associated factors among high school youths in Debretabor town, South Gondar zone, North West Ethiopia, 2017. BMC Res Notes 12 , 314 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-019-4348-3

Download citation

Received : 11 February 2019

Accepted : 29 May 2019

Published : 03 June 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-019-4348-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Premarital sex

BMC Research Notes

ISSN: 1756-0500

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

The Effect of Sex Education on Premarital Sex Among Adolescents; Literature Review

Related Papers

Journal of Adolescent Health

American Journal of Epidemiology

Carolyn Halpern

European Journal of Educational Sciences

Kolawole Ajiboye

Encyclopedia of Adolescence

Eva Goldfarb

drugsandalcohol.ie

Maria Lohan

Sexuality & Culture

Mohan Ghule

Family Planning Perspectives

James M. Lepkowski

Progress in Chemical and Biochemical Research

Marcos Bollido

Raquel Luengo

Adolescence is the time during which the personal and sexual identity develops. The specific characteristics of adolescents and the lack of maturity facilitates the acquisition of sexual risk behaviors such as relaxation in the use of barrier contraceptives or the use of toxic substances, alcohol or drugs during sexual relations, increasing of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and unwanted pregnancies. Health education in sexuality is one of the best ways to prevent risk behaviors and to promote healthy and responsible sexuality. While there have been different works in sex education in adolescents, there is still a lack of a comprehensive systematic literature review that including randomized and non-randomized clinical trials and quasi-experimental pre-post studies addressing education programs that provide information on healthy and responsible sexuality. Further, it is noted that a protocol drafted in consideration of the existing approaches is needed to present a basis for...

RELATED PAPERS

Fordham Law Review

Alexandra Lahav

Erik Verlinde

Prof.Dr. Sevilay Topcu

Biochemical Journal

Diana Bigelow

La Revue de Médecine Interne

Anne Moreau

World journal of emergency medicine

Rias Van Wyk

Oriental Journal of Chemistry

Environmental Monitoring and Assessment

Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control

Mario Padula

Development

Cynthia Kenyon

Germán Bordel

Thoria Alghamdi

Sass Bálint

Daniela Bímová

Journal of The Korean Chemical Society

Jeongho Choi

Kind en adolescent Review

Louis Tavecchio

el-Ibtidaiy:Journal of Primary Education

Annisa Nisa

Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America

Kwok-hung Chan

Child: Care, Health and Development

Syed Mobashshir Huda 2112440630

İBRAHİM YİĞEN

Crop Protection

Rhodes Makundi

Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis

FRANCESCO BERNARDI

anita mahajan

Microbial Cell Factories

Lidia Gurba

See More Documents Like This

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Read our research on: Abortion | Podcasts | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

Key takeaways on americans’ views of and experiences with dating and relationships.

Dating has always come with challenges. But the advent of dating apps and other new technologies – as well as the #MeToo movement – presents a new set of norms and expectations for American singles looking for casual or committed relationships, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey .

Some 15% of U.S. adults say they are single and looking for a committed relationship or casual dates. Among them, most say they are dissatisfied with their dating lives, according to the survey, which was conducted in October 2019 – before the coronavirus pandemic shook up the dating scene. Here are some additional key findings from the study.

Pew Research Center conducted this study to understand Americans’ attitudes toward and personal experiences with dating and relationships. These findings are based on a survey conducted Oct. 16-28, 2019, among 4,860 U.S. adults. This includes those who took part as members of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses, as well as respondents from the Ipsos KnowledgePanel who indicated that they identify as lesbian, gay or bisexual (LGB).

Recruiting ATP panelists by phone or mail ensures that nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. This gives us confidence that any sample can represent the whole U.S. adult population (see our Methods 101 explainer on random sampling). To further ensure that each ATP survey reflects a balanced cross-section of the nation, the data is weighted to match the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories.

For more, see the report’s methodology about the project. You can also find the questions asked and the answers the public provided in this topline .

Nearly half (47%) of all Americans say dating is harder today than it was 10 years ago. A third of adults (33%) say dating is about the same as it was a decade ago, and 19% say it’s easier. Women are much more likely than men to say dating has gotten harder (55% vs. 39%).

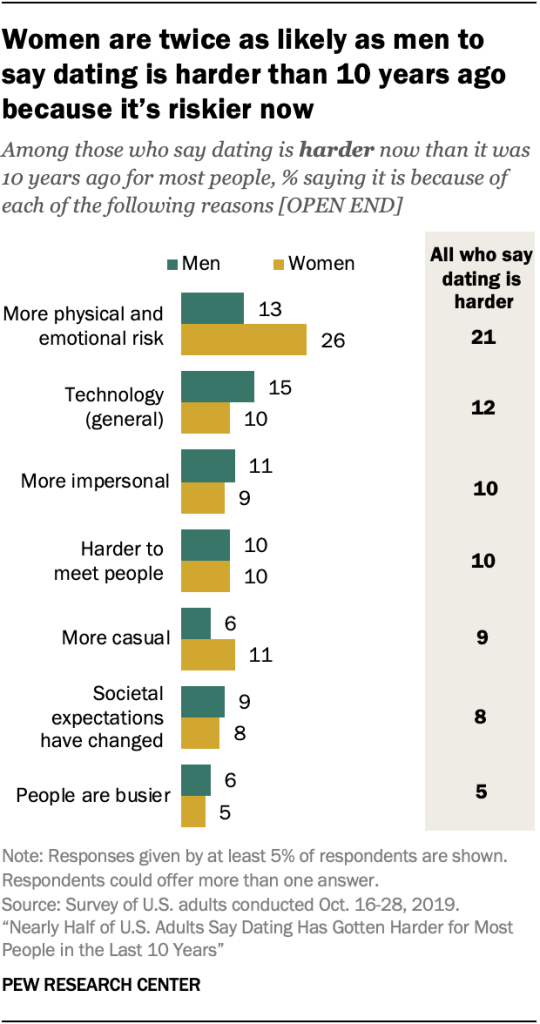

Among those who say dating is harder today, 21% think it is because of increased risk, including physical risks as well as the risk of getting scammed or lied to. Women are twice as likely as men to cite increased risk as a reason why dating is harder (26% vs. 13%).

Other reasons why people think dating is harder include technology (12%), the idea that dating has become more impersonal (10%), the more casual nature of dating today (9%), and changing societal expectations, moral or gender roles (8%).

Technology tops the list of reasons why people think dating has gotten easier in the last decade. Among those who say dating is easier today, 41% point to technology, followed by 29% who say it’s easier to meet people now and 10% who cite changing gender roles and societal expectations.

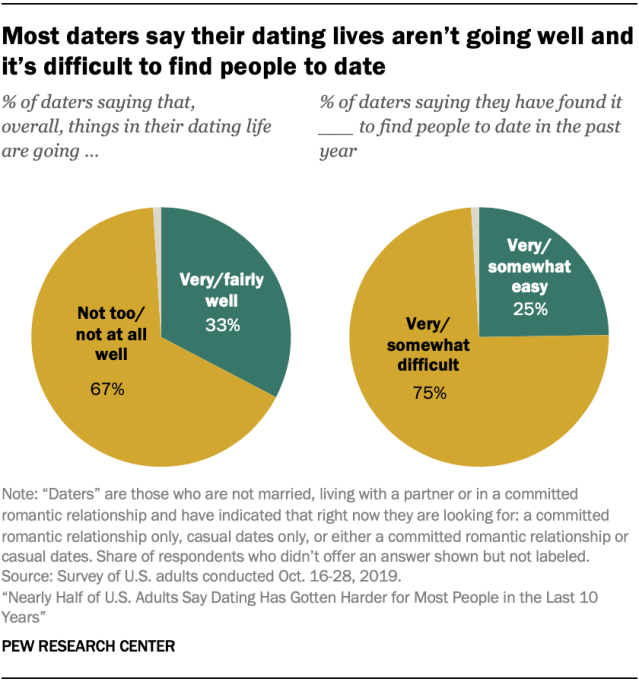

Most daters don’t feel like their dating life is going well and say it’s been hard to find people to date. Two-thirds of those who are single and looking for a relationship or dates say their dating life is going not too or not at all well (67%), while 33% say it’s going very or fairly well. Majorities of daters across gender, age, race and ethnicity, education, sexual orientation and marital history say their dating life isn’t going well.

Three-quarters of daters say it’s been difficult to find people to date in the past year, according to the pre-coronavirus survey. Among the top reasons cited are finding someone looking for the same type of relationship (53%), finding it hard to approach people (46%) and finding someone who meets their expectations (43%).

Substantial shares of daters also report other obstacles, including the limited number of people in their area (37%), being too busy (34%) and people not being interested in dating them (30%).

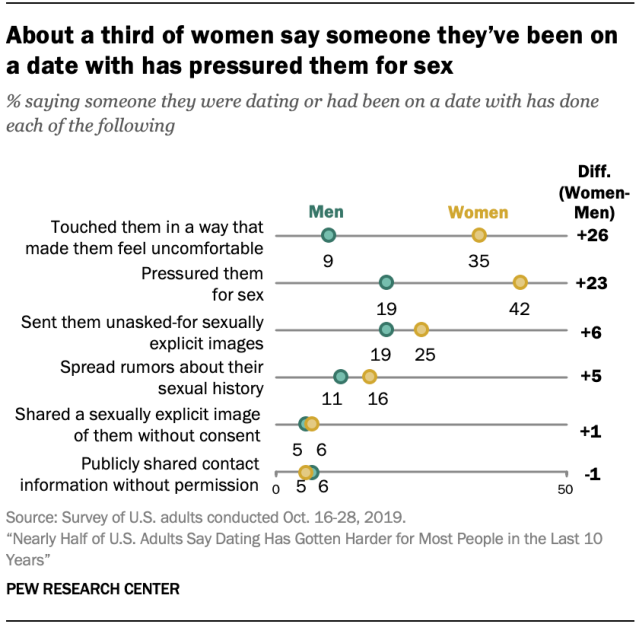

A majority (57%) of women – and 35% of men – say they have experienced some kind of harassing behavior from someone they were dating or had been on a date with. Women are much more likely than men to say they have been pressured for sex (42% vs. 19%) or have been touched in a way that made them feel uncomfortable (35% vs. 9%). While the gender gap is smaller, women are also more likely than men to say someone they have been on a date with sent them unwanted sexually explicit images or spread rumors about their sexual history.

Some 42% of women younger than 40 say someone they’ve been on a date with has sent them unwanted sexually explicit images, compared with 26% of men in this age group. And while 23% of women younger than 40 say someone they have been on a date with has spread rumors about their sexual history, 16% of younger men say the same. There is no gender gap on these questions among those older than 40.

Many Americans say an increased focus on sexual harassment and assault has muddied the waters, especially for men, in the dating landscape. A majority of Americans (65%) say the increased focus on sexual harassment and assault over the last few years has made it harder for men to know how to interact with someone they’re on a date with. About one-in-four adults (24%) say it hasn’t made much of a difference, while 9% say it has made things easier for men.

Meanwhile, 43% of Americans say the attention paid to sexual harassment and assault has made it harder for women to know how to interact with someone they’re on a date with, compared with 38% who say it hasn’t made much of a difference and 17% who say it’s easier for women.

Men are more likely than women to think the focus on sexual harassment and assault has made it harder for men to know how to act on dates. Republicans and Republican-leaning independents are more likely than Democrats and Democratic leaners to say this. Older men are also more likely than their younger counterparts to hold this view: Three-quarters of men 50 and older say it’s harder for single-and-looking men to know how to behave, compared with 63% of men younger than 50.

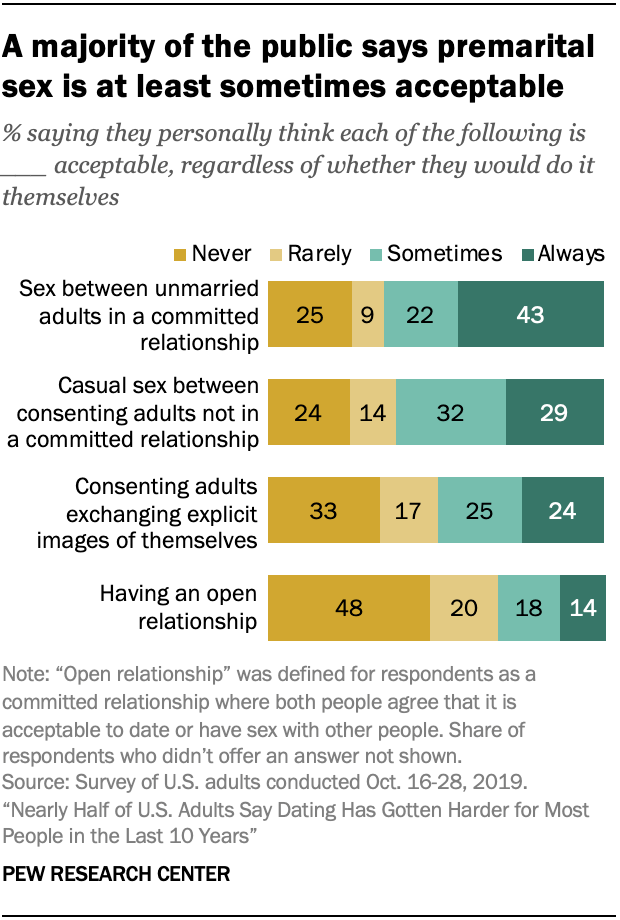

Premarital sex is largely seen as acceptable, but more Americans see open relationships and sex on the first date as taboo. Most adults (65%) say sex between unmarried adults in a committed relationship can be acceptable, and about six-in-ten (62%) say casual sex between consenting adults who aren’t in a committed relationship is acceptable at least sometimes. While men and women have similar views about premarital sex, men are much more likely than women to find casual sex acceptable (70% vs. 55%).

Americans are less accepting of other practices. For example, open relationships – that is, committed relationships where both people agree that it is acceptable to date or have sex with other people – are viewed as never or rarely acceptable by most Americans. About half of adults (48%) say having an open relationship is never acceptable, 20% say it’s rarely acceptable and 32% say it’s sometimes or always acceptable.

When it comes to consenting adults sharing sexually explicit images of themselves, about half of adults (49%) say it is at least sometimes acceptable, while a similar share (50%) say it is rarely or never acceptable. However, there are large age differences in views of this practice. Adults ages 18 to 29 are more than three times as likely as those 65 and older to say this is always or sometimes acceptable (70% vs. 21%). Younger adults are also more likely to say open relationships can be acceptable.

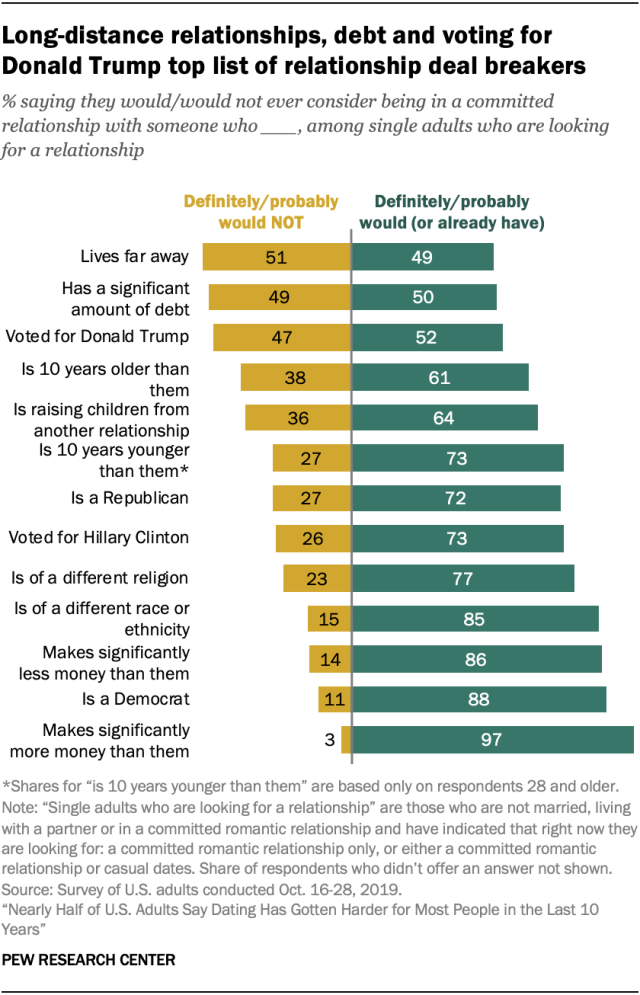

Many singles are open to dating someone who is different from them, but certain characteristics would give some people pause. Distance, debt and voting for Donald Trump top the list of reasons singles looking for a relationship wouldn’t consider a potential partner, but there are other considerations, too. For example, 38% say dating someone 10 years older than them would give them pause, and 36% say the same about dating someone who is raising children from another relationship. Some of those looking for a relationship also say they definitely or probably wouldn’t consider being in a relationship with someone who is a Republican (27% of all daters), someone who voted for Hillary Clinton (26%), someone who practices a different religion (23%) or someone who is a different race or ethnicity (15%). Among daters looking for a relationship who are 28 and older, 27% say they definitely or probably wouldn’t consider a relationship with someone 10 years younger than them.

There are some differences in these attitudes by gender, political party and age. For example, single women looking for a relationship are roughly three times as likely as men to say they wouldn’t consider a relationship with someone who makes significantly less money than them (24% vs. 7%). Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say they probably or definitely wouldn’t consider a committed relationship with someone of a different race or ethnicity (21% vs. 12%). And when it comes to debt, 59% of adults 40 and older say they probably or definitely wouldn’t consider a committed relationship with someone who has significant debt, compared with 41% of people younger than 40.

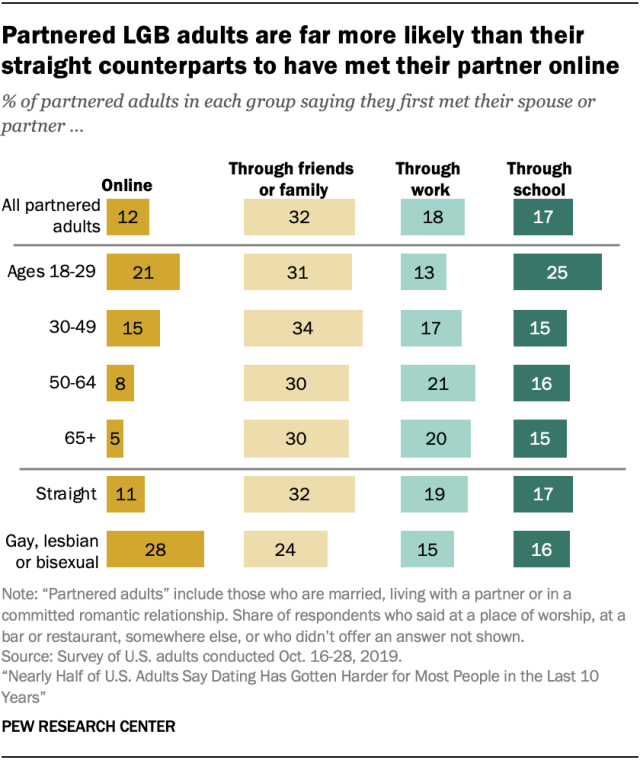

While meeting partners through personal networks is still the most common kind of introduction, about one-in-ten partnered adults (12%) say they met their partner online. About a third (32%) of adults who are married, living with a partner or are in a committed relationship say friends and family helped them find their match. Smaller shares say they met through work (18%), through school (17%), online (12%), at a bar or restaurant (8%), at a place of worship (5%) or somewhere else (8%).

Meeting online is more common among younger adults and those who live in urban and suburban areas, as well as those who are lesbian, gay or bisexual (LGB). About one-in-five partnered adults ages 18 to 29 (21%) say they met their partner online, compared with 15% or fewer among their older counterparts. And while 28% of partnered LGB adults say they met their partner online, 11% of those who are straight say the same.

Among those who met their partner online, 61% say they met through a dating app, while 21% met on a social media site or app, 10% met on an online discussion forum, 3% met on a texting or messaging app and 3% through online gaming.

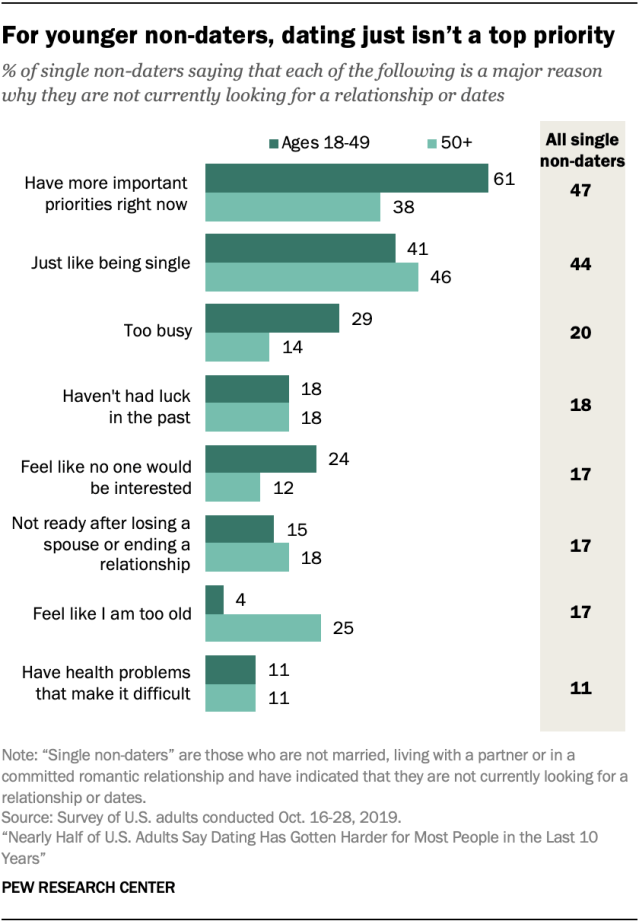

Half of singles say they aren’t currently looking for a relationship or dates. Among these single non-daters, 47% say a major reason why they aren’t currently looking for a relationship or dates is that they have more important priorities, while 44% say they just like being single. Other factors include being too busy (20%), not having had luck in the past (18%), feeling like no one would be interested in dating them (17%), not being ready to date after losing a spouse or ending a relationship (17%), feeling too old to date (17%) and having health problems that make dating difficult (11%).

While these answers are mostly similar for men and women, there is one notable exception: Male non-daters are about twice as likely as female non-daters to say a major reason they aren’t looking to date is the feeling that no one would be interested in dating them (26% vs. 12%).

There is also some variation by age. For example, 61% of non-daters younger than 50 say that a major reason they aren’t looking to date is that they have more important priorities, compared with 38% of older non-daters. And a quarter of non-daters ages 50 and older – including 30% of those 65 and up – say a major reason is they that feel too old to date.

Note: Here are the questions asked for this report, along with responses, and its methodology .

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivered Saturday mornings

For Valentine’s Day, facts about marriage and dating in the U.S.

Dating at 50 and up: older americans’ experiences with online dating, about half of lesbian, gay and bisexual adults have used online dating, about half of never-married americans have used an online dating site or app, for valentine’s day, 5 facts about single americans, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Premarital Sex Attitudes Among Youth and Adults Research Paper

Introduction, methodology, works cited.

The project is dedicated to people’s attitudes towards the issue of premarital sex. The purpose of the report is to find out the similarities and differences in people’s treatment of the issue. The research aims at finding out whether people’s age, education, ethnicity, gender, and other demographic data have a common or divergent impact on their attitude to premarital sex. The theory is that the level of education and age impact people’s opinions about premarital sex. The hypothesis of the project is that adult females are more likely to disapprove of premarital sex than other age and gender groups.

To obtain the data necessary for the project, I did a survey. I prepared a questionnaire (see Appendix A) consisting of 19 questions: 6 questions regarding their personal data, 8 questions regarding their attitude to premarital sex, and 5 questions about their premarital sex experience (1 question about having the experience and 4 questions for those who answered positively the first one). The type of survey was true or false. The participants were required to enter their demographic data (age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital/living status, sexual orientation, and education). Then, they were suggested 8 questions that were aimed at finding out their attitude towards the issue. The questions were created in such a way which allowed to find out whether people felt positive or negative about premarital sex and why they felt so. The third block of questions was to be answered by those who admitted having practiced premarital sex.

The survey did not require the participants to reveal their names, phone numbers, or addresses. It was designed for purely informational purposes and was completely anonymous. Since most of my friends and family felt uncomfortable taking the survey, I had to find other respondents to obtain twenty completed questionnaires. I distributed the survey among the visitors to a local café and park, and I obtained several participants’ answers via the internet.

The average age of the participants was 36 years old, the youngest being 17, and the oldest being 63. Half of the participants were female, and the other half were male. 16 participants reported straight sexual orientation, and 4 were homosexual (three males and one female). 5 participants were at high school, 1 was at college, and 14 people finished a university (2 of them had a Bachelor’s degree, 8 had a Master’s degree, and 4 obtained a Ph.D. level). What concerns ethnicity, 10 respondents were white Americans, 6 were African Americans, 3 were Asian, and 1 was European. The participants’ marital/living status was reported as a single for 6 people, in a relationship – 3 people, married – 8, and divorced – 3 people. The variety of demographic data allowed to obtain the results from different populations, which gives more reliability to the obtained outcomes.

The results were analyzed and synthesized to find the common and divergent opinions concerning the issue.

65% of respondents disapproved of premarital sex, among them 46.15% males and 53.84% females. However, only 35% of the participants are being judgmental about the issue of premarital sex.

72.72% of respondents at the age of 17- 33 (the “millennials”) reported their disapproval of premarital sex, but 45.45% of those disapproving it admitted practicing it.

55.55% of respondents at the age of 41- 63 reported their disapproval of premarital sex, but 100% of them admitted practicing it. Out of this age group, 50% females expressed their disapproval and 50% females were not against it.

25% of participants reported that their attitude towards premarital sex was impacted by family upbringing. 60% of males considered premarital sex beneficial for the future family, whereas only 20% of females reported the same.

None of the respondents considered premarital sex the main cause of sexually transmitted diseases. 20% of females considered premarital sex the major reason for undesired pregnancy and abortions.

The average number of sexual partners reported by respondents between 17 and 33 years old was 3, and for the respondents between 41 and 63 years old, it was 3.77.

55% of respondents were or had been married. Out of these, 72.72% practiced premarital sex. 36.36% male and 9.09% female respondents who were or had been married said that premarital sex could cause mistrust among the partners if they lost virginity to other people. 20% of respondents had married or planned to marry their first premarital sex partners. 42.8% of females and 37.5% of males regretted having practiced premarital sex. Out of the females, 66.66% of younger respondents (17-31 years old) and 33.33% of older (41-60 years old) regretted having practiced premarital sex.

10% males and 20% females admitted the negative impact of premarital sex on their decision to marry the partner. 20% males and 5% females admitted the positive impact of premarital sex on their decision to marry the partner. 45% did not report any impact.

According to the General Social Survey results, people tend to change their attitudes towards premarital sex (Kraft). Over the last fifty years, the number of those who do not disapprove of it rose from 29% in the 1970s to 58% in 2012 (Kraft). In my report, 65% of people feel negative about the issue. However, only one-third of the respondents feel judgmental. Furthermore, many of those who disapprove of premarital sex admitted having practiced it. 55.55% of female participants between 40 and 61 years old disapproved of premarital sex. This result does not coincide with the hypothesis about adult females being more likely to disapprove of premarital sex than other age and gender groups. However, such result is common in other studies. According to research performed by Elias et al., people’s permissiveness of premarital sex is higher in the younger age (131). A study by Wright supports this idea and reports that young people are less opposed to premarital sex, and the tendency is growing (89).

Fernández-Villaverde et al. argue that the youth’s attitude to premarital sex is not connected with church’s or parents’ influence as long as contraceptives allow young people to avoid undesired pregnancy (27). However, a quarter of my respondents admitted that they felt the family impact when forming their attitude to premarital sex.

Elias et al. mention that married people are less permissive of premarital sex than single people (132). The results of my questionnaire agree with this argument as many of the married respondents reported their negative attitude of premarital sex. Some of them regretted having practiced it, and some even considered it a serious barrier to trust between spouses.

According to Ghebremichael and Finkelman, there is a higher risk of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) among women engaging in premarital sex (61). However, my survey showed that neither female nor male respondents considered these two issues connected. This controversy signifies the importance of increasing the population’s literacy concerning STDs. The same thing concerns the abortion rates. While the survey participants do not tend to associate premarital sex with unwanted pregnancy and abortion, Teferra et al. report a high level of abortion among young women (2).

The hypothesis of the project was not justified. Among the participants of the survey, older females did not report higher disapproval of premarital sex. The results of the survey are contradictory to the findings of some research articles. This situation can be explained in two ways. For one thing, people’s attitudes tend to alter very fast and frequently. Thus, the data incorporated in the current project is more modern. However, there may be another explanation of the divergences. The number of participants in the current project was much smaller than the number of people surveyed for the articles discussed.

Questionnaire about Attitudes to Premarital Sex (PS)

Elias, Vicky L., et al. “Long-Term Changes in Attitudes Toward Premarital Sex in the United States: Reexamining the Role of Cohort Replacement.” Journal of Sex Research , vol. 52, no. 2, 2015, pp. 129-139.

Fernández-Villaverde, Jesús, et al. “From Shame to Game in One Hundred Years: an Economic Model of the Rise in Premarital Sex and Its De-Stigmatization.” Journal of the European Economic Association , vol. 12, no. 1, 2014, pp. 25-61.

Ghebremichael, Musie S., and Finkelman, Matthew D. “The Effect of Premarital Sex on Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) and High Risk Behaviors in Women.” Journal of AIDS and HIV Research , vol. 5, no. 2, 2013, pp. 59-64.

Kraft, Amy. “Changing Attitudes about Premarital Sex, Homosexuality.” CBS News , 2015. Web.

Teferra, Tomas Benti, et al. “Prevalence of Premarital Sexual Practice and Associated Factors among Undergraduate Health Science Students of Madawalabu University, Bale Goba, South East Ethiopia: Institution Based Cross Sectional Study.” PanAfrican Medical Journal , vol. 20, no. 209, 2015, pp. 1-11.

Wright, Paul J. “Americans’ Attitudes Toward Premarital Sex and Pornography Consumption: A National Panel Analysis.” Archives of Sexual Behavior , vol. 44, no. 1, 2015, pp. 89-97.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, September 10). Premarital Sex Attitudes Among Youth and Adults. https://ivypanda.com/essays/premarital-sex-attitudes-among-youth-and-adults/

"Premarital Sex Attitudes Among Youth and Adults." IvyPanda , 10 Sept. 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/premarital-sex-attitudes-among-youth-and-adults/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'Premarital Sex Attitudes Among Youth and Adults'. 10 September.

IvyPanda . 2020. "Premarital Sex Attitudes Among Youth and Adults." September 10, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/premarital-sex-attitudes-among-youth-and-adults/.

1. IvyPanda . "Premarital Sex Attitudes Among Youth and Adults." September 10, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/premarital-sex-attitudes-among-youth-and-adults/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Premarital Sex Attitudes Among Youth and Adults." September 10, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/premarital-sex-attitudes-among-youth-and-adults/.

- The Importance of Premarital Counseling Before Marriage

- Butterfly Effect with Premarital Sex

- Behavioral Trends Paper Premarital Sex Document

- Social Issues: Teen Pregnancy

- Relationship Between Premarital and Marital Satisfaction

- Teen Pregnancy: Abortion Rates Rise

- Premarital Counseling

- Premarital Cohabitation's Impact on Marriage

- Premarital Counseling Discussion

- Sexual Double Standard for Men and Women

- Gender in Media Presentation and Public Opinion

- Modern Girl from Historical and Gender Perspectives

- Australian Workforce Changes After WWII

- Gender in Atlas of Emotions by Giuliana Bruno

- Gender-Neutral vs. Traditional Upbringing

- Free Essays

- Citation Generator

Research Paper about Premarital Sex (Chapter 1)

You May Also Find These Documents Helpful

Psy 220 week 4 review paper.

Heavily influenced by young person’s social context. Typically parents provide little to no info on sex, discourage sex play and rarely talk about sex in children’s presence. If kids do not receive info from parents they will find out from books, magazines, friends or tv shows that depict that partners are spontaneous, taking no precautions and having no consequences. Early and frequent teenage sexual activity is linked to personal, family, peer and educational characteristics.…

Effects of Early Marriage

Marriage, as a fundamental social and cultural institution and as the most common milieu for bearing and rearing children, profoundly shapes sexual behaviors and practices. It is undeniable that early marriage is a controversial yet hot topic that gets the attention of the professionals across many fields such as economy, psychology and sociology. The age at first marriage variegates across the globe. Being married before the age of 18 has been a social norm in third world countries [refer to Appendix A]. The percentage of women being married before age 18 is estimated from 20 to 50 percent in average in developing countries (Joyce, et al., 2001).…

Premartial Sex

This paper will include my research on premarital sex. For many years, premarital sex has been seen as a type of deviant behavior; but like many other concepts, deviant behavior can be define in many ways. This research will include a clear definition of deviant behavior and its relationship with premarital sex.…

Research: High School and Students

This chapter presents the background of the study, the statement of the problem, the significance of the study, and scope and delimitation.…

Customer Satisfaction

This chapter is divided into five parts: (1) Background and Theoretical Framework of the Study, (2) Statement of the Problem and the Hypothesis, (3) Significance of the Study, (4) Definition of Terms, and (5) Delimitation of the Study.…

Marriage and Ancient Rome Eras

The study is significant to everyone, especially to the youth who are still unaware of the different effects it may bring to the society and to their own lives. It is important that the people’s attention be caught so that their awareness about premarital sex and its effects will increase and as a result, they will be one of those well-educated people who show concern not only to themselves but to the society.…

risk management challenges

Definition of ProblemThe crisis concentrated on in this editorial is teenage pregnancy. “Teenage pregnancy poses as a major public emergency both internationally as well as nationally” (Karnik & Kaneka, 2012, para. 1.) The alarm of teenage pregnancy has developed into a governmental altitude requiring action to aid children and their families to reframe from sexual activity as well as sexier sex techniques. Some feel the reason for most teenage pregnancy cases are due to peer pressure. There are quite a few factors such as behavioral, environmental and genetics that enhance the possibility of early teenage pregnancy. The alarm of teenage pregnancy has increased throughout the years due to the changes in society. It is important to educate both the children and parents on safe sex techniques. The importance to stop the epidemic of teenage pregnancy is to reduce the number of unplanned and unwanted pregnancies.…

Pre-marital Sex: College students point of view

Society has forbid premarital sex from the very outlook that adolescence is the time to form oneself as mature and responsible human being and not at all a time to procreate. Sex in itself, is not wrong at any age; but premarital sex may harm the mental development of adults in several forms. Premarital sexual experiences, many a times, leads to the misconception that sex is to be enjoyed at whatever ways possible. Forced premarital lovemaking will lead to mental depression and dilemma. Another danger is possible exchange of diseases; as premarital partners may not be aware of diseases that spread through intercourses. Getting pregnant through premarital sex is another disaster. Emotional imbalances and guilt feeling could be the result of most premarital sexual affairs.…

Pre-Marital Sex & Role of Youth in Building a Nation

Premarital sexual relationship is an important subject – especially today. Young people are bombarded with the world’s standards of morality, or immorality. The values and moral standards, which were endorsed by most Filipinos in years past, are now ridiculed and/or ignored by many.…

Premarital Sex

Causes and Effects on Premarital Sex” by Stephanie Joyce Uymatiao for English IV Second Term 2007-2008 Submitted to Miss Melfe Cañolas Cuizon Holy Cross High School Outline Page I. Introduction II. Definition of Terms A. Sex B. Adolescents...…

Nothing: Marriage and View Premarital Sex

Premarital sex is a huge problem in society today; the numbers are staggering. "Among Americans who have been married, a raging ninety- three percent of men, and eighty percent of women (between ages eighteen and fifty-four) have lost their virginity before their honeymoon" (Hjelle). Teens everywhere are not waiting until they are married to have sex. "Teenagers are saying, ‘sex is fun’ and ‘everybody is doing it’" (Dave). Teens are less developed, emotionally and physically before having sex, and they are not prepared for the serious problems that come along with their decision to have sex. There are always consequences when a teenager chooses to have sex. "Teenagers, according to some polls, view premarital sex as acceptable as long as ‘two people love each other’" (Hjelle). If at age sixteen a teenager tells a parent or someone older that they are in love, the parent will laugh and say that no teenager at sixteen has experienced true love. Love is something one experiences when one is mature and ready for a life-long commitment, not when one is involved in a two-year high school crush. "Premarital sex is based on selfishness, not on love" (Hjelle). If one has passionate feelings for someone, one may feel the need to have intercourse with that person. Teens need to open their eyes and see the harmful effects of premarital sex. "Premarital sex hurts you (sic), running the risk of getting diseases and it profoundly scars you emotionally, by cutting you off from God" (Evert). Some teenage girls are saying, "Oh I’ll be fine, I am on birth control and we used a condom; there are no worries." "No form of contraception can prevent a heart from being broken, and a soul from being lost"(Evert). While contraceptives may lessen the…

The Advantages of Science

Since the 1990s, extra-marital relationships such as mistress-fostering have become less uncommon, resulting in psychological fear among the youth nowadays. So it is becoming quite common to have a trial marriage, Unsatisfactory sex is one of the major reasons for divorces, therefore premarital sex, in this sense, may help avoid unhappy marriages.…

After watching unmarried people having unwanted pregnancies , children from parents that dont want them , and children from parents that are not prepared to have them , I assume premarital sex is a controversial issue nowadays and we can see it everyday on the newspaper , Television , in our families , our society.…

PMS from Wikipedia esc

In some cultures, the significance of premarital sex has traditionally been related to the concept of virginity. However, unlike virginity, premarital sex can refer to more than one occasion of sexual activity or more than one sex partner. There are cultural differences as to whether and in which circumstances premarital sex is socially acceptable or tolerated. Social attitudes to premarital sex have changed over time as has the prevalence of premarital sex in various societies. Social attitudes to premarital sex can include issues such as virginity, sexual morality, extramarital unplanned pregnancy, legitimacy besides other issues.…

Heterosexual Adolescent Sexual Behavior in the United States

Adolescence in the United States is defined by Miller (2007) as “. . . a person between puberty and marriage” (p. 157). The majority of studies involved in this research are teenagers between the ages of 14 – 19 years of age; their age group will be the focus of this research paper. These adolescents are becoming sexually active in large numbers. According to a study of…

Related Topics

- Sexual intercourse

- Human sexuality

- Human sexual behavior

- Albert Bandura

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Premarital Education and Later Relationship Help-seeking

Hannah c. williamson.

University of Texas at Austin

Julia F. Hammett

University of California, Los Angeles

Jaclyn M. Ross

Benjamin r. karney, thomas n. bradbury.

Despite evidence that empirically supported couple therapies improve marital relationships, relatively few couples seek help when they need it. Low-income couples are particularly unlikely to engage in relationship interventions despite being at greater risk for distress and dissolution than their higher-income counterparts. The present study aimed to clarify how premarital education influences couples’ progression through different stages of later help-seeking, as identified in prior research. Using five waves of self-report data from a sample of 431 ethnically diverse newlywed couples living in low-income neighborhoods, analyses revealed that wives who received premarital education later considered seeking therapy at a higher level of relationship satisfaction and lower level of problem severity than those who did not receive premarital education, though this was not true for husbands. Wives who received premarital education were also more likely as newlyweds to say that they would seek therapy if their relationship was in trouble, though husbands were not. Spouses who considered seeking therapy were more likely to follow through with participation if they had received premarital education, whereas if they had not received premarital education they were more likely to consider seeking therapy without following through. Similarly, among couples who received therapy, those who also received premarital education sought therapy earlier than those who did not receive premarital education, though not at a higher level of relationship satisfaction. Taken together, these results suggest that participation in premarital education is linked with later help-seeking by empowering couples to take steps throughout their marriage to maintain their relationship.

Although empirically-supported couple therapies reliably improve relationships (e.g., Baucom, Atkins, Rowe, Doss, & Christensen, 2015 ), relatively few couples seek help when they need it ( Halford, Kelly, & Markman, 1997 ). Efforts to increase rates of help-seeking among couples are complicated by the fact that both spouses are required to participate, and men in particular appear to be less interested in seeking therapy and slower to pursue treatment once the decision is made ( Doss, Atkins, & Christensen, 2003 ; also see Addis & Mahalik, 2003 ). The present study aims to understand how couples naturally seek help and how prior experience with premarital education might contribute to this process. We focus specifically on help-seeking among couples living with low incomes — couples who are less likely to participate in relationship interventions than middle-class couples ( Halford, O’Donnell, Lizzio, & Wilson, 2006 ; Sullivan & Bradbury, 1997 ) despite being at greater risk for distress and dissolution (e.g., Bramlett & Mosher, 2001).

Increasing uptake of couple therapy may pivot on couples’ earlier experiences with premarital education. Although the long-term effectiveness of premarital education remains a topic of debate ( Bradbury & Lavner, 2012 ; Cowan & Cowan, 2014 ), these programs are widely available and very well-received by couples ( Halford & Bodenmann, 2013 ). To the extent that premarital education does improve relationships, we would predict that couples’ newly established skills and awareness should reduce their need for later treatment. Paradoxically, however, couples who receive premarital education appear to be more likely to seek couple therapy compared those who do not receive it, a possibility suggested by early developers of premarital education programs ( Halford, Markman, Kline, & Stanley, 2003 ; Stanley, 2001 ) and later demonstrated empirically ( Williamson, Trail, Bradbury, & Karney, 2014 ). Described as the gateway effect , this finding suggests that participation in premarital education induces later help-seeking by empowering couples to maintain their relationship and directing them to resources that enable them to do so. This view implies that increasing participation in premarital education will lead to greater rather than lesser eventual use of couple therapy, perhaps at a time when relationships are still functioning relatively well. We build on this premise by undertaking a replication of the gateway effect and, more critically, by specifying how participation in premarital education might affect the process by which couples later seek therapy.

Drawing from Doss, Atkins, and Christensen’s (2003) model of couple help-seeking, we propose that participation in premarital education will operate upon the progression toward help-seeking in three ways. In the initial stage, partners first recognize and acknowledge friction in the relationship that they cannot readily repair on their own. Here, premarital education might increase couples’ awareness of relationship problems earlier in their marriage, at a time when these problems may be more easily resolved. Consistent with this possibility, premarital education programs appear to heighten awareness of communication deficits targeted specifically within those programs (e.g., couples trained to resolve conflict appear to have greater awareness of unresolved conflict; Rogge, Cobb, Lawrence, Johnson, & Bradbury, 2013 ). In the second stage, partners consider what to do about their difficulties and whether or not couple therapy could be a solution for them. Couples with prior experience in premarital education should be more likely to consider counseling to be a viable option, compared to couples who had not experienced premarital education. Finally, in Doss et al.’s (2003) third stage, partners actively participate in couple therapy. At this point we might expect that premarital education participants would feel less threatened by therapy, and more inclined to see value in more intensive intervention, and therefore take steps as a couple to seek it out.

In this study we test three predictions about how participation in premarital education will covary with couples’ progression through these stages of help-seeking. First, to examine whether premarital education is associated with heightened awareness of relationship problems, we test whether couples who receive premarital education consider seeking therapy when their relationship satisfaction is higher and their levels of relationship problems are lower, compared to couples who did not receive premarital education. Second, to examine whether premarital education is associated with considering treatment, we test whether couples who receive premarital education are more likely as newlyweds to report that they will seek professional help and to report that they have considered seeking therapy after marrying. Third, to examine whether premarital education covaries with help-seeking behaviors, we test whether premarital education receipt is associated with an increased likelihood that couples who consider seeking therapy actually receive it, and whether those who receive premarital education convert from considering to seeking therapy more quickly than couples who did not receive premarital education.

We conduct these tests using five waves of self-report data, collected over the first four-five years of marriage from a sample of 431 ethnically diverse couples living in low-income communities. We focus on this important segment of the population in response to calls for greater diversity in research on couples (e.g., Karney, Kreitz, & Sweeney, 2004 ; Rogge et al., 2006 ) and more specifically because enhancing relationships among people living with sociodemographic disadvantage can stabilize the financial status of people who, were they to divorce, would be subject to even more severe forms of poverty and especially poor child outcomes (e.g., Amato, 2000 ). More pointedly, the gateway effect is especially strong for high-risk populations, including African American couples and couples living with lower incomes and less formal education ( Williamson, Trail, Bradbury, & Karney, 2014 ). Understanding how premarital education may increase use of couple therapy is therefore likely to have greater impact on vulnerable couples than on couples with more economic resources.

The sampling procedure was designed to yield first-married newlywed couples in which both partners were of the same ethnicity (Hispanic, African American, or Caucasian), living in neighborhoods with a high proportion of low-income residents in Los Angeles County. Recently married couples were identified through names and addresses on marriage license applications. Addresses were matched with census data to identify applicants living in low-income communities, defined as census block groups wherein the median household income was no more than 160% of the 1999 federal poverty level for a 4-person family. Next, names on the licenses were weighted using data from a Bayesian Census Surname Combination, which integrates census and surname information to produce a multinomial probability of membership in each of four racial/ethnic categories (Hispanic, African American, Asian, and Caucasian/other). Couples were chosen using probabilities proportionate to the ratio of target prevalences to the population prevalences, weighted by the couple’s average estimated probability of being Hispanic, African American, or Caucasian. A total of 3,793 couples were contacted through the addresses they listed on their marriage licenses, and offered the opportunity to participate in a longitudinal study of newlywed development. Of the 3,793 couples contacted, 2,049 could not be reached and 1,522 responded to the mailing and agreed to be screened for eligibility. Of those, 824 couples were screened as eligible, and 658 of them agreed to participate in the study, with 431 couples actually completing the study.

Participants

The sample comprised 862 spouses (431 couples) identified with the above procedures. At baseline, marriages averaged 4.8 months in duration ( SD = 2.5); 38.5% of couples had children. Mean ages were 26.3 ( SD = 5.0) for women and 27.9 ( SD = 5.8) for men. Median household income was $45,000. Twelve percent of couples were African American, 12% were Caucasian, and 76% were Hispanic.

At baseline (T1), couples were visited in their homes by two interviewers who took spouses to separate areas to describe the IRB approved study, obtain informed consent, and orally administer self-report measures. Interviewers returned at 9 months (T2), 18 months (T3), and 27 months after baseline (T4) and administered the same interview protocol. Couples who reported that they had divorced or separated did not complete the interview. Following each interview couples were debriefed and paid $75 for T1, $100 for T2, $125 for T3 and $150 for T4. At Time 5 (T5), which occurred an average of 22 months after T4, all intact couples and spouses from dissolved couples were contacted via telephone. Each individual was compensated $25 for the T5 interview. Data collection took place between 2009 and 2013 for T1 through T4. Collection of T5 data occurred in February and March 2014.

Over the course of the study, 93 couples (21.6%) were lost to attrition while 55 couples (12.8%) divorced or legally separated. The average number of waves completed was 4.08 out of 5; 241 couples completed all five waves, 89 couples completed four waves, 36 couples completed three waves, 24 couples completed two waves, and 41 couples completed only baseline. Missing data was handled by using all available data for analysis. Thus, if a couple completed fewer than all five waves of assessment their cumulative variables (i.e., consideration of couple therapy, receipt of relationship counseling) were calculated based upon the waves at which they provided data.

Premarital Education

At T1 participants were asked “Did the two of you receive any sort of relationship education or classes before you got married?” Reponses were coded as 0 = no and 1= yes . Couples were coded as receiving premarital education if either spouse responded yes . In 86% of couples, partners agreed on whether or not they received premarital education. In 7% of couples the husband reported that they received premarital education but the wife did not, and in 7% of couples the wife reported that they received premarital education and the husband did not.

Help-seeking Intentions

Participants’ intentions to seek therapy in the future if they were to experience relationship difficulties were measured with two items administered at T1. Participants were asked; “If you and [SPOUSE NAME] were having marital difficulties, what would you do about it?” Responses to the option “get therapy” were coded as 0 = no and 1 = yes . Next participants were asked; “If you needed to, who would you talk to about your marriage?” Individuals who responded yes to “professional counselor” and/or “other professional (doctor, social worker, etc.)” were coded as 0 = no and 1 = yes .

Consideration of Couple Therapy

Whether participants had considered seeking help for their relationship was assessed by asking “In the last nine months, did you ever consider seeking or receiving counseling for this relationship?” at T2 – T5. Responses were coded 0 = no and 1 = yes at each time point and then collapsed across time points, such that an individual who responded yes at any time point was coded as 1 and individuals who responded no at all time points were coded as 0.

To calculate the level of relationship satisfaction and problem severity at which participants considered seeking therapy, we used the relationship satisfaction and problem severity scores reported at the time point prior to when they reported considering therapy. For example, if an individual reported at T2 that they had considered seeking therapy at some point over the past 9 months, their relationship satisfaction and problem severity scores from T1 would be assigned as the level at which they considered therapy.

Relationship Counseling

At T2 – T5 participants were asked “In the last nine months, have you received counseling for this relationship?” Reponses were coded as 1= yes and 0 = no . Couples were coded as receiving counseling if either spouse responded yes . In 86% of couples, partners agreed on whether or not they received counseling. In 5% of couples the husband reported that they received counseling but the wife did not, and in 9% of couples the wife reported that they received counseling and the husband did not.

To calculate the level of relationship satisfaction and problem severity at which participants sought counseling, we used the relationship satisfaction and problem severity scores reported at the time point prior to when they reported receiving counseling. For example, if an individual reported at T2 that they had received counseling at some point over the past 9 months, their relationship satisfaction and problem severity scores from T1 would be assigned as the level at which they received counseling.

Relationship Satisfaction

Relationship satisfaction at each time point was assessed by summing responses on an eight-item questionnaire. Five items asked how satisfied the respondent was with certain areas of their relationship (e.g., “satisfaction with the amount of time spent together”), and were scored on a 5-point scale (ranging from 1 = Very dissatisfied to 5 = Very satisfied ). Three items asked the degree to which the participant agreed with a statement about their relationship, (e.g., “how much do you trust your partner”) and were scored on a 4-point scale (1 = Not at all , 2 = Not that much , 3 = Somewhat, 4 = Completely ). Coefficient α exceeded .70 for husbands and wives across all time points.

Relationship Problem Severity

At T1–T5 participants rated how much each of 28 common areas of marital disagreement (e.g., management of money, relationships with in-laws; adapted from Geiss & O’Leary, 1981 ) was a source of difficulty/disagreement in their relationship on a scale of 0 to 10, such that higher scores reflected issues that caused frequent or intense conflict. To measure the maximum severity of the relationship problems, each participant’s maximum problem rating (possible score 0–10) across the 28 items was assigned as their problem score.

Descriptive Statistics and Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for the study variables. Roughly 45% of couples received premarital education, which is relatively high in comparison to other studies of premarital education (e.g., 29% reported by Halford and colleagues (2006) ). At the time of marriage, 35% of husbands and 41% of wives reported that they intended to “get therapy” if their relationship were to become troubled, whereas only 26% of husbands and 25% of wives reported that they would talk to a “professional counselor.” Over the course of their marriage, 40% of husbands and 51% of wives considered seeking therapy at some point; 27% of couples went on to actually receive therapy.

Base rates of key study variables