- AsianStudies.org

- Annual Conference

- EAA Articles

- 2025 Annual Conference March 13-16, 2025

- AAS Community Forum Log In and Participate

Education About Asia: Online Archives

The korean war 101: causes, course, and conclusion of the conflict.

North Korea attacked South Korea on June 25, 1950, igniting the Korean War. Cold War assumptions governed the immediate reaction of US leaders, who instantly concluded that Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin had ordered the invasion as the first step in his plan for world conquest. “Communism,” President Harry S. Truman argued later in his memoirs, “was acting in Korea just as [Adolf] Hitler, [Benito] Mussolini, and the Japanese had acted ten, fifteen, and twenty years earlier.” If North Korea’s aggression went “unchallenged, the world was certain to be plunged into another world war.” This 1930s history lesson prevented Truman from recognizing that the origins of this conflict dated to at least the start of World War II, when Korea was a colony of Japan. Liberation in August 1945 led to division and a predictable war because the US and the Soviet Union would not allow the Korean people to decide their own future.

Before 1941, the US had no vital interests in Korea and was largely indifferent to its fate.

Before 1941, the US had no vital interests in Korea and was largely in- different to its fate. But after Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his advisors acknowledged at once the importance of this strategic peninsula for peace in Asia, advocating a postwar trusteeship to achieve Korea’s independence. Late in 1943, Roosevelt joined British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Chinese Generalissimo Chiang Kaishek in signing the Cairo Declaration, stating that the Allies “are determined that in due course Korea shall become free and independent.” At the Yalta Conference in early 1945, Stalin endorsed a four-power trusteeship in Korea. When Harry S. Truman became president after Roosevelt’s death in April 1945, however, Soviet expansion in Eastern Europe had begun to alarm US leaders. An atomic attack on Japan, Truman thought, would preempt Soviet entry into the Pacific War and allow unilateral American occupation of Korea. His gamble failed. On August 8, Stalin declared war on Japan and sent the Red Army into Korea. Only Stalin’s acceptance of Truman’s eleventh-hour proposal to divide the peninsula into So- viet and American zones of military occupation at the thirty-eighth parallel saved Korea from unification under Communist rule.

Deterioration of Soviet-American relations in Europe meant that neither side was willing to acquiesce in any agreement in Korea that might strengthen its adversary.

US military occupation of southern Korea began on September 8, 1945. With very little preparation, Washing- ton redeployed the XXIV Corps under the command of Lieutenant General John R. Hodge from Okinawa to Korea. US occupation officials, ignorant of Korea’s history and culture, quickly had trouble maintaining order because al- most all Koreans wanted immediate in- dependence. It did not help that they followed the Japanese model in establishing an authoritarian US military government. Also, American occupation officials relied on wealthy land- lords and businessmen who could speak English for advice. Many of these citizens were former Japanese collaborators and had little interest in ordinary Koreans’ reform demands. Meanwhile, Soviet military forces in northern Korea, after initial acts of rape, looting, and petty crime, implemented policies to win popular support. Working with local people’s committees and indigenous Communists, Soviet officials enacted sweeping political, social, and economic changes. They also expropriated and punished landlords and collaborators, who fled southward and added to rising distress in the US zone. Simultaneously, the Soviets ignored US requests to coordinate occupation policies and allow free traffic across the parallel.

Deterioration of Soviet-American relations in Europe meant that neither side was willing to acquiesce in any agreement in Korea that might strengthen its adversary. This became clear when the US and the Soviet Union tried to implement a revived trusteeship plan after the Moscow Conference in December 1945. Eighteen months of intermittent bilateral negotiations in Korea failed to reach agreement on a representative group of Koreans to form a provisional government, primarily because Moscow refused to consult with anti-Communist politicians opposed to trustee- ship. Meanwhile, political instability and economic deterioration in southern Korea persisted, causing Hodge to urge withdrawal. Postwar US demobilization that brought steady reductions in defense spending fueled pressure for disengagement. In September 1947, the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) added weight to the withdrawal argument when they advised that Korea held no strategic significance. With Communist power growing in China, however, the Truman administration was unwilling to abandon southern Korea precipitously, fearing domestic criticism from Republicans and damage to US credibility abroad.

Seeking an answer to its dilemma, the US referred the Korean dispute to the United Nations, which passed a resolution late in 1947 calling for internationally supervised elections for a government to rule a united Korea. Truman and his advisors knew the Soviets would refuse to cooper- ate. Discarding all hope for early reunification, US policy by then had shifted to creating a separate South Korea, able to defend itself. Bowing to US pressure, the United Nations supervised and certified as valid obviously undemocratic elections in the south alone in May 1948, which resulted in formation of the Republic of Korea (ROK) in August. The Soviet Union responded in kind, sponsoring the creation of the Democratic People’s Re- public of Korea (DPRK) in September. There now were two Koreas, with President Syngman Rhee installing a repressive, dictatorial, and anti-Communist regime in the south, while wartime guerrilla leader Kim Il Sung imposed the totalitarian Stalinist model for political, economic, and social development on the north. A UN resolution then called for Soviet-American withdrawal. In December 1948, the Soviet Union, in response to the DPRK’s request, removed its forces from North Korea.

South Korea’s new government immediately faced violent opposition, climaxing in October 1948 with the Yosu-Sunchon Rebellion. Despite plans to leave the south by the end of 1948, Truman delayed military withdrawal until June 29, 1949. By then, he had approved National Security Council (NSC) Paper 8/2, undertaking a commitment to train, equip, and supply an ROK security force capable of maintaining internal order and deterring a DPRK attack. In spring 1949, US military advisors supervised a dramatic improvement in ROK army fighting abilities. They were so successful that militant South Korean officers began to initiate assaults northward across the thirty-eighth parallel that summer. These attacks ignited major border clashes with North Korean forces. A kind of war was already underway on the peninsula when the conventional phase of Korea’s conflict began on June 25, 1950. Fears that Rhee might initiate an offensive to achieve reunification explain why the Truman administration limited ROK military capabilities, withholding tanks, heavy artillery, and warplanes.

Pursuing qualified containment in Korea, Truman asked Congress for three-year funding of economic aid to the ROK in June 1949. To build sup- port for its approval, on January 12, 1950, Secretary of State Dean G. Ache- son’s speech to the National Press Club depicted an optimistic future for South Korea. Six months later, critics charged that his exclusion of the ROK from the US “defensive perimeter” gave the Communists a “green light” to launch an invasion. However, Soviet documents have established that Acheson’s words had almost no impact on Communist invasion planning. Moreover, by June 1950, the US policy of containment in Korea through economic means appeared to be experiencing marked success. The ROK had acted vigorously to control spiraling inflation, and Rhee’s opponents won legislative control in May elections. As important, the ROK army virtually eliminated guerrilla activities, threatening internal order in South Korea, causing the Truman administration to propose a sizeable military aid increase. Now optimistic about the ROK’s prospects for survival, Washington wanted to deter a conventional attack from the north.

Stalin worried about South Korea’s threat to North Korea’s survival. Throughout 1949, he consistently refused to approve Kim Il Sung’s persistent requests to authorize an attack on the ROK. Communist victory in China in fall 1949 pressured Stalin to show his support for a similar Korean outcome. In January 1950, he and Kim discussed plans for an invasion in Moscow, but the Soviet dictator was not ready to give final consent. How- ever, he did authorize a major expansion of the DPRK’s military capabilities. At an April meeting, Kim Il Sung persuaded Stalin that a military victory would be quick and easy because of southern guerilla support and an anticipated popular uprising against Rhee’s regime. Still fearing US military intervention, Stalin informed Kim that he could invade only if Mao Zedong approved. During May, Kim Il Sung went to Beijing to gain the consent of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Significantly, Mao also voiced concern that the Americans would defend the ROK but gave his reluctant approval as well. Kim Il Sung’s patrons had joined in approving his reckless decision for war.

On the morning of June 25, 1950, the Korean People’s Army (KPA) launched its military offensive to conquer South Korea. Rather than immediately committing ground troops, Truman’s first action was to approve referral of the matter to the UN Security Council because he hoped the ROK military could defend itself with primarily indirect US assistance. The UN Security Council’s first resolution called on North Korea to accept a cease- fire and withdraw, but the KPA continued its advance. On June 27, a second resolution requested that member nations provide support for the ROK’s defense. Two days later, Truman, still optimistic that a total commitment was avoidable, agreed in a press conference with a newsman’s description of the conflict as a “police action.” His actions reflected an existing policy that sought to block Communist expansion in Asia without using US military power, thereby avoiding increases in defense spending. But early on June 30, he reluctantly sent US ground troops to Korea after General Douglas MacArthur, US Occupation commander in Japan, advised that failure to do so meant certain Communist destruction of the ROK.

Kim Il Sung’s patrons [Stalin and Mao] had joined in approving his reckless decision for war.

On July 7, 1950, the UN Security Council created the United Nations Command (UNC) and called on Truman to appoint a UNC commander. The president immediately named MacArthur, who was required to submit periodic reports to the United Nations on war developments. The ad- ministration blocked formation of a UN committee that would have direct access to the UNC commander, instead adopting a procedure whereby MacArthur received instructions from and reported to the JCS. Fifteen members joined the US in defending the ROK, but 90 percent of forces were South Korean and American with the US providing weapons, equipment, and logistical support. Despite these American commitments, UNC forces initially suffered a string of defeats. By July 20, the KPA shattered five US battalions as it advanced one hundred miles south of Seoul, the ROK capital. Soon, UNC forces finally stopped the KPA at the Pusan Perimeter, a rectangular area in the southeast corner of the peninsula.

On September 11, 1950, Truman had approved NSC-81, a plan to cross the thirty-eighth parallel and forcibly reunify Korea

Despite the UNC’s desperate situation during July, MacArthur developed plans for a counteroffensive in coordination with an amphibious landing behind enemy lines allowing him to “compose and unite” Korea. State Department officials began to lobby for forcible reunification once the UNC assumed the offensive, arguing that the US should destroy the KPA and hold free elections for a government to rule a united Korea. The JCS had grave doubts about the wisdom of landing at the port of Inchon, twenty miles west of Seoul, because of narrow access, high tides, and sea- walls, but the September 15 operation was a spectacular success. It allowed the US Eighth Army to break out of the Pusan Perimeter and advance north to unite with the X Corps, liberating Seoul two weeks later and sending the KPA scurrying back into North Korea. A month earlier, the administration had abandoned its initial war aim of merely restoring the status quo. On September 11, 1950, Truman had approved NSC-81, a plan to cross the thirty-eighth parallel and forcibly reunify Korea.

Invading the DPRK was an incredible blunder that transformed a three-month war into one lasting three years. US leaders had realized that extension of hostilities risked Soviet or Chinese entry, and therefore, NSC- 81 included the precaution that only Korean units would move into the most northern provinces. On October 2, PRC Foreign Minister Zhou Enlai warned the Indian ambassador that China would intervene in Korea if US forces crossed the parallel, but US officials thought he was bluffing. The UNC offensive began on October 7, after UN passage of a resolution authorizing MacArthur to “ensure conditions of stability throughout Korea.” At a meeting at Wake Island on October 15, MacArthur assured Truman that China would not enter the war, but Mao already had decided to intervene after concluding that Beijing could not tolerate US challenges to its regional credibility. He also wanted to repay the DPRK for sending thou- sands of soldiers to fight in the Chinese civil war. On August 5, Mao instructed his northeastern military district commander to prepare for operations in Korea in the first ten days of September. China’s dictator then muted those associates opposing intervention.

On October 19, units of the Chinese People’s Volunteers (CPV) under the command of General Peng Dehuai crossed the Yalu River. Five days later, MacArthur ordered an offensive to China’s border with US forces in the vanguard. When the JCS questioned this violation of NSC-81, MacArthur replied that he had discussed this action with Truman on Wake Island. Having been wrong in doubting Inchon, the JCS remained silent this time. Nor did MacArthur’s superiors object when he chose to retain a divided command. Even after the first clash between UNC and CPV troops on October 26, the general remained supremely confident. One week later, the Chinese sharply attacked advancing UNC and ROK forces. In response, MacArthur ordered air strikes on Yalu bridges without seeking Washing- ton’s approval. Upon learning this, the JCS prohibited the assaults, pending Truman’s approval. MacArthur then asked that US pilots receive permission for “hot pursuit” of enemy aircraft fleeing into Manchuria. He was infuriated upon learning that the British were advancing a UN proposal to halt the UNC offensive well short of the Yalu to avert war with China, viewing the measure as appeasement.

On November 24, MacArthur launched his “Home-by-Christmas Offensive.” The next day, the CPV counterattacked en masse, sending UNC forces into a chaotic retreat southward and causing the Truman administration immediately to consider pursuing a Korean cease-fire. In several public pronouncements, MacArthur blamed setbacks not on himself but on unwise command limitations. In response, Truman approved a directive to US officials that State Department approval was required for any comments about the war. Later that month, MacArthur submitted a four- step “Plan for Victory” to defeat the Communists—a naval blockade of China’s coast, authorization to bombard military installations in Manchuria, deployment of Chiang Kai-shek Nationalist forces in Korea, and launching of an attack on mainland China from Taiwan. The JCS, despite later denials, considered implementing these actions before receiving favorable battlefield reports.

Early in 1951, Lieutenant General Matthew B. Ridgway, new commander of the US Eighth Army, halted the Communist southern advance. Soon, UNC counterattacks restored battle lines north of the thirty-eighth parallel. In March, MacArthur, frustrated by Washington’s refusal to escalate the war, issued a demand for immediate surrender to the Communists that sabotaged a planned cease-fire initiative. Truman reprimanded but did not recall the general. On April 5, House Republican Minority Leader Joseph W. Martin Jr. read MacArthur’s letter in Congress, once again criticizing the administration’s efforts to limit the war. Truman later argued that this was the “last straw.” On April 11, with the unanimous support of top advisors, the president fired MacArthur, justifying his action as a defense of the constitutional principle of civilian control over the military, but another consideration may have exerted even greater influence on Truman. The JCS had been monitoring a Communist military buildup in East Asia and thought a trusted UNC commander should have standing authority to retaliate against Soviet or Chinese escalation, including the use of nuclear weapons that they had deployed to forward Pacific bases. Truman and his advisors, as well as US allies, distrusted MacArthur, fearing that he might provoke an incident to widen the war.

MacArthur’s recall ignited a firestorm of public criticism against both Truman and the war. The general returned to tickertape parades and, on April 19, 1951, he delivered a televised address before a joint session of Congress, defending his actions and making this now-famous assertion: “In war there is no substitute for victory.” During Senate joint committee hearings on his firing in May, MacArthur denied that he was guilty of in- subordination. General Omar N. Bradley, the JCS chair, made the administration’s case, arguing that enacting MacArthur’s proposals would lead to “the wrong war, at the wrong place, at the wrong time, and with the wrong enemy.” Meanwhile, in April, the Communists launched the first of two major offensives in a final effort to force the UNC off the peninsula. When May ended, the CPV and KPA had suffered huge losses, and a UNC counteroffensive then restored the front north of the parallel, persuading Beijing and Pyongyang, as was already the case in Washington, that pursuit of a cease-fire was necessary. The belligerents agreed to open truce negotiations on July 10 at Kaesong, a neutral site that the Communists deceitfully occupied on the eve of the first session.

North Korea and China created an acrimonious atmosphere with at- tempts at the outset to score propaganda points, but the UNC raised the first major roadblock with its proposal for a demilitarized zone extending deep into North Korea. More important, after the talks moved to Panmunjom in October, there was rapid progress in resolving almost all is- sues, including establishment of a demilitarized zone along the battle lines, truce enforcement inspection procedures, and a postwar political conference to discuss withdrawal of foreign troops and reunification. An armistice could have been concluded ten months after talks began had the negotiators not deadlocked over the disposition of prisoners of war (POWs). Rejecting the UNC proposal for non-forcible repatriation, the Communists demanded adherence to the Geneva Convention that required return of all POWs. Beijing and Pyongyang were guilty of hypocrisy regarding this matter because they were subjecting UNC prisoners to unspeakable mistreatment and indoctrination.

On April 11, with the unanimous support of top advisors, the presi- dent fired MacArthur.

Truman ordered that the UNC delegation assume an inflexible stand against returning Communist prisoners to China and North Korea against their will. “We will not buy an armistice,” he insisted, “by turning over human beings for slaughter or slavery.” Although Truman unquestionably believed in the moral rightness of his position, he was not unaware of the propaganda value derived from Communist prisoners defecting to the “free world.” His advisors, however, withheld evidence from him that contradicted this assessment. A vast majority of North Korean POWs were actually South Koreans who either joined voluntarily or were impressed into the KPA. Thousands of Chinese POWs were Nationalist soldiers trapped in China at the end of the civil war, who now had the chance to escape to Taiwan. Chinese Nationalist guards at UNC POW camps used terrorist “re-education” tactics to compel prisoners to refuse repatriation; resisters risked beatings or death, and repatriates were even tattooed with anti- Communist slogans.

In November 1952, angry Americans elected Dwight D. Eisenhower president, in large part because they expected him to end what had be- come the very unpopular “Mr. Truman’s War.” Fulfilling a campaign pledge, the former general visited Korea early in December, concluding that further ground attacks would be futile. Simultaneously, the UN General Assembly called for a neutral commission to resolve the dispute over POW repatriation. Instead of embracing the plan, Eisenhower, after taking office in January 1953, seriously considered threatening a nuclear attack on China to force a settlement. Signaling his new resolve, Eisenhower announced on February 2 that he was ordering removal of the US Seventh Fleet from the Taiwan Strait, implying endorsement for a Nationalist assault on the mainland. What influenced China more was the devastating impact of the war. By summer 1952, the PRC faced huge domestic economic problems and likely decided to make peace once Truman left office. Major food shortages and physical devastation persuaded Pyongyang to favor an armistice even earlier.

An armistice ended fighting in Korea on July 27, 1953.

Early in 1953, China and North Korea were prepared to resume the truce negotiations, but the Communists preferred that the Americans make the first move. That came on February 22 when the UNC, repeating a Red Cross proposal, suggested exchanging sick and wounded prisoners. At this key moment, Stalin died on March 5. Rather than dissuading the PRC and the DPRK as Stalin had done, his successors encouraged them to act on their desire for peace. On March 28, the Communist side accepted the UNC proposal. Two days later, Zhou Enlai publicly proposed transfer of prisoners rejecting repatriation to a neutral state. On April 20, Operation Little Switch, the exchange of sick and wounded prisoners, began, and six days later, negotiations resumed at Panmunjom. Sharp disagreement followed over the final details of the truce agreement. Eisenhower insisted later that the PRC accepted US terms after Secretary of State John Foster Dulles informed India’s prime minister in May that without progress toward a truce, the US would terminate the existing limitations on its conduct of the war. No documentary evidence has of yet surfaced to support his assertion.

Also, by early 1953, both Washington and Beijing clearly wanted an armistice, having tired of the economic burdens, military losses, political and military constraints, worries about an expanded war, and pressure from allies and the world community to end the stalemated conflict. A steady stream of wartime issues threatened to inflict irrevocable damage on US relations with its allies in Western Europe and nonaligned members of the United Nations. Indeed, in May 1953, US bombing of North Korea’s dams and irrigation system ignited an outburst of world criticism. Later that month and early in June, the CPV staged powerful attacks against ROK defensive positions. Far from being intimidated, Beijing thus displayed its continuing resolve, using military means to persuade its adversary to make concessions on the final terms. Before the belligerents could sign the agreement, Rhee tried to torpedo the impending truce when he released 27,000 North Korean POWs. Eisenhower bought Rhee’s acceptance of a cease-fire with pledges of financial aid and a mutual security pact.

An armistice ended fighting in Korea on July 27, 1953. Since then, Koreans have seen the war as the second-greatest tragedy in their recent history after Japanese colonial rule. Not only did it cause devastation and three million deaths, it also confirmed the division of a homogeneous society after thirteen centuries of unity, while permanently separating millions of families. Meanwhile, US wartime spending jump-started Japan’s economy, which led to its emergence as a global power. Koreans instead had to endure the living tragedy of yearning for reunification, as diplomatic tension and military clashes along the demilitarized zone continued into the twenty-first century.

Korea’s war also dramatically reshaped world affairs. In response, US leaders vastly increased defense spending, strengthened the North Atlantic Treaty Organization militarily, and pressed for rearming West Germany. In Asia, the conflict saved Chiang’s regime on Taiwan, while making South Korea a long-term client of the US. US relations with China were poisoned for twenty years, especially after Washington persuaded the United Nations to condemn the PRC for aggression in Korea. Ironically, the war helped Mao’s regime consolidate its control in China, while elevating its regional prestige. In response, US leaders, acting on what they saw as Korea’s primary lesson, relied on military means to meet the challenge, with disastrous results in Việt Nam.

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

SUGGESTED RESOURCES

Kaufman, Burton I. The Korean Conflict . Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1999.

“Korea: Lessons of the Forgotten War.” YouTube video, 2:20, posted by KRT Productions Inc., 2000. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fi31OoQfD7U.

Lee, Steven Hugh. The Korean War. New York: Longman, 2001.

Matray, James I. “Korea’s War at Sixty: A Survey of the Literature.” Cold War History 11, no. 1 (February 2011): 99–129.

US Department of Defense. Korea 1950–1953, accessed July 9, 2012, http://koreanwar.defense.gov/index.html.

- Latest News

- Join or Renew

- Education About Asia

- Education About Asia Articles

- Asia Shorts Book Series

- Asia Past & Present

- Key Issues in Asian Studies

- Journal of Asian Studies

- The Bibliography of Asian Studies

- AAS-Gale Fellowship

- Council Grants

- Book Prizes

- Graduate Student Paper Prizes

- Distinguished Contributions to Asian Studies Award

- First Book Subvention Program

- External Grants & Fellowships

- AAS Career Center

- Asian Studies Programs & Centers

- Study Abroad Programs

- Language Database

- Conferences & Events

- #AsiaNow Blog

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: May 11, 2022 | Original: November 9, 2009

The Korean war began on June 25, 1950, when some 75,000 soldiers from the North Korean People’s Army poured across the 38th parallel, the boundary between the Soviet-backed Democratic People’s Republic of Korea to the north and the pro-Western Republic of Korea to the south. This invasion was the first military action of the Cold War. By July, American troops had entered the war on South Korea’s behalf. As far as American officials were concerned, it was a war against the forces of international communism itself. After some early back-and-forth across the 38th parallel, the fighting stalled and casualties mounted with nothing to show for them. Meanwhile, American officials worked anxiously to fashion some sort of armistice with the North Koreans. The alternative, they feared, would be a wider war with Russia and China–or even, as some warned, World War III. Finally, in July 1953, the Korean War came to an end. In all, some 5 million soldiers and civilians lost their lives in what many in the U.S. refer to as “the Forgotten War” for the lack of attention it received compared to more well-known conflicts like World War I and II and the Vietnam War. The Korean peninsula remains divided today.

North vs. South Korea

“If the best minds in the world had set out to find us the worst possible location in the world to fight this damnable war,” U.S. Secretary of State Dean Acheson (1893-1971) once said, “the unanimous choice would have been Korea.” The peninsula had landed in America’s lap almost by accident. Since the beginning of the 20th century, Korea had been a part of the Japanese empire , and after World War II it fell to the Americans and the Soviets to decide what should be done with their enemy’s imperial possessions. In August 1945, two young aides at the State Department divided the Korean peninsula in half along the 38th parallel . The Russians occupied the area north of the line and the United States occupied the area to its south.

Did you know? Unlike World War II and Vietnam, the Korean War did not get much media attention in the United States. The most famous representation of the war in popular culture is the television series “M*A*S*H,” which was set in a field hospital in South Korea. The series ran from 1972 until 1983, and its final episode was the most-watched in television history.

By the end of the decade, two new states had formed on the peninsula. In the south, the anti-communist dictator Syngman Rhee (1875-1965) enjoyed the reluctant support of the American government; in the north, the communist dictator Kim Il Sung (1912-1994) enjoyed the slightly more enthusiastic support of the Soviets. Neither dictator was content to remain on his side of the 38th parallel, however, and border skirmishes were common. Nearly 10,000 North and South Korean soldiers were killed in battle before the war even began.

The Korean War and the Cold War

Even so, the North Korean invasion came as an alarming surprise to American officials. As far as they were concerned, this was not simply a border dispute between two unstable dictatorships on the other side of the globe. Instead, many feared it was the first step in a communist campaign to take over the world. For this reason, nonintervention was not considered an option by many top decision makers. (In fact, in April 1950, a National Security Council report known as NSC-68 had recommended that the United States use military force to “contain” communist expansionism anywhere it seemed to be occurring, “regardless of the intrinsic strategic or economic value of the lands in question.”)

“If we let Korea down,” President Harry Truman (1884-1972) said, “the Soviet[s] will keep right on going and swallow up one [place] after another.” The fight on the Korean peninsula was a symbol of the global struggle between east and west, good and evil, in the Cold War. As the North Korean army pushed into Seoul, the South Korean capital, the United States readied its troops for a war against communism itself.

At first, the war was a defensive one to get the communists out of South Korea, and it went badly for the Allies. The North Korean army was well-disciplined, well-trained and well-equipped; Rhee’s forces in the South Korean army, by contrast, were frightened, confused and seemed inclined to flee the battlefield at any provocation. Also, it was one of the hottest and driest summers on record, and desperately thirsty American soldiers were often forced to drink water from rice paddies that had been fertilized with human waste. As a result, dangerous intestinal diseases and other illnesses were a constant threat.

By the end of the summer, President Truman and General Douglas MacArthur (1880-1964), the commander in charge of the Asian theater, had decided on a new set of war aims. Now, for the Allies, the Korean War was an offensive one: It was a war to “liberate” the North from the communists.

Initially, this new strategy was a success. The Inch’on Landing , an amphibious assault at Inch’on, pushed the North Koreans out of Seoul and back to their side of the 38th parallel. But as American troops crossed the boundary and headed north toward the Yalu River, the border between North Korea and Communist China, the Chinese started to worry about protecting themselves from what they called “armed aggression against Chinese territory.” Chinese leader Mao Zedong (1893-1976) sent troops to North Korea and warned the United States to keep away from the Yalu boundary unless it wanted full-scale war.

'No Substitute for Victory'

This was something that President Truman and his advisers decidedly did not want: They were sure that such a war would lead to Soviet aggression in Europe, the deployment of atomic weapons and millions of senseless deaths. To General MacArthur, however, anything short of this wider war represented “appeasement,” an unacceptable knuckling under to the communists.

As President Truman looked for a way to prevent war with the Chinese, MacArthur did all he could to provoke it. Finally, in March 1951, he sent a letter to Joseph Martin, a House Republican leader who shared MacArthur’s support for declaring all-out war on China–and who could be counted upon to leak the letter to the press. “There is,” MacArthur wrote, “no substitute for victory” against international communism.

For Truman, this letter was the last straw. On April 11, the president fired the general for insubordination.

The Korean War Reaches a Stalemate

In July 1951, President Truman and his new military commanders started peace talks at Panmunjom. Still, the fighting continued along the 38th parallel as negotiations stalled. Both sides were willing to accept a ceasefire that maintained the 38th parallel boundary, but they could not agree on whether prisoners of war should be forcibly “repatriated.” (The Chinese and the North Koreans said yes; the United States said no.)

Finally, after more than two years of negotiations, the adversaries signed an armistice on July 27, 1953. The agreement allowed the POWs to stay where they liked; drew a new boundary near the 38th parallel that gave South Korea an extra 1,500 square miles of territory; and created a 2-mile-wide “demilitarized zone” that still exists today.

Korean War Casualties

The Korean War was relatively short but exceptionally bloody. Nearly 5 million people died. More than half of these–about 10 percent of Korea’s prewar population–were civilians. (This rate of civilian casualties was higher than World War II’s and the Vietnam War’s .) Almost 40,000 Americans died in action in Korea, and more than 100,000 were wounded. Today, they are remembered at the Korean War Veterans Memorial near the Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., a series of 19 steel statues of servicemen, and the Korean War memorial in Fullerton, California , the first on the West Coast to include the names of the more than 30,000 Americans who died in the war.

HISTORY Vault

Stream thousands of hours of acclaimed series, probing documentaries and captivating specials commercial-free in HISTORY Vault

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

Selling the Korean War: Propaganda, Politics, and Public Opinion in the United States, 1950-1953

Lecturer in International History

Author Webpage

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

How presidents spark and sustain support for wars remains an enduring and significant problem. Korea was the first limited war the United States experienced in the contemporary period—the first recent war fought for something less than total victory. This book explores how Truman and then Eisenhower tried to sell it to the American public. Based on primary sources, this book explores the government's selling activities from all angles. It looks at the halting and sometimes chaotic efforts of Truman and Acheson, Eisenhower and Dulles. It examines the relationships that they and their subordinates developed with a host of other institutions, from Congress and the press to Hollywood and labor. And it assesses the complex and fraught interactions between the military and war correspondents in the battlefield theater itself. From high politics to bitter media spats, this book guides the reader through the domestic debates of this messy, costly war. It highlights the actions and calculations of colorful figures, including Taft, McCarthy, and MacArthur. It details how the culture and work routines of Congress and the media influenced political tactics and daily news stories. And the book explores how different phases of the war threw up different problems.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Home — Essay Samples — War — Korean War

Essays on Korean War

Korean war essay topics and outline examples, essay title 1: the korean war (1950-1953): uncovering the origins, cold war context, and global implications.

Thesis Statement: This essay delves into the complex origins of the Korean War, the Cold War context that fueled the conflict, and the far-reaching global implications of the war, including its impact on international alliances and the division of Korea.

- Introduction

- Background and Historical Context: Pre-war Korea and Its Division

- The Cold War Setting: U.S.-Soviet Rivalry and Proxy Wars

- The Outbreak of War: North Korea's Invasion and International Response

- The Course of the Conflict: Battles, Truce Talks, and Stalemate

- Global Implications: The Korean War's Impact on East Asia and International Relations

- Legacy and Repercussions: The Division of Korea and Ongoing Tensions

Essay Title 2: The Korean War's Forgotten Heroes: Examining the Role of United Nations Forces and the Armistice Agreement

Thesis Statement: This essay focuses on the often-overlooked contributions of United Nations forces in the Korean War, the complexities of the Armistice Agreement, and the enduring impact of the war on Korean society and international peacekeeping efforts.

- The United Nations Coalition: Multinational Forces in Korea

- The Armistice Negotiations: Challenges, Agreements, and Ongoing Tensions

- Forgotten Heroes: Stories of Courage and Sacrifice

- Korean War Veterans: Their Post-War Experiences and Commemoration

- Peacekeeping and Reconciliation Efforts: The Role of the United Nations

- Implications for Modern International Conflict Resolution

Essay Title 3: The Korean War and the Origins of the Cold War: Analyzing the Impact on U.S.-Soviet Relations and Global Alliances

Thesis Statement: This essay explores how the Korean War influenced U.S.-Soviet relations, the formation of military alliances such as NATO and the Warsaw Pact, and the Cold War's evolution into a global struggle for influence.

- The Korean War as a Catalyst: Escalation of Cold War Tensions

- Military Alliances: NATO, the Warsaw Pact, and the Globalization of the Cold War

- The U.S.-Soviet Confrontation: Proxy Warfare and Diplomatic Efforts

- International Response and Support for North and South Korea

- The Aftermath of the Korean War: Paving the Way for Future Cold War Conflicts

- Assessing the Korean War's Long-Term Impact on U.S.-Soviet Relations

The Korean War – a Conflict Between The Soviet Union and The United States

The local and global effects of the korean war, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

The Role of The Korean War in History

The origin of the korean conflict, the role of the battle of chipyong-ni in the korean war, the korean war and its impact on lawrence werner, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Historical Accuracy of The Book Korean War by Maurice Isserman

Solutions for disputes and disloyalty, depiction of the end of the korean war in the film the front line, the impact of war on korea.

25 June, 1950 - 27 July, 1953

Korean Peninsula, Yellow Sea, Sea of Japan, Korea Strait, China–North Korea border.

China, North Korea, South Korea, United Nations, United States

Korean War was a conflict between the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) and the Republic of Korea (South Korea) in which at least 2.5 million persons lost their lives. The war reached international proportions in June 1950 when North Korea, supplied and advised by the Soviet Union, invaded the South.

North Korean invasion of South Korea repelled; US-led United Nations invasion of North Korea repelled; Chinese and North Korean invasion of South Korea repelled; Korean Armistice Agreement signed in 1953; Korean conflict ongoing.

Relevant topics

- Vietnam War

- Israeli Palestinian Conflict

- Syrian Civil War

- Nuclear Weapon

- Atomic Bomb

- The Spanish American War

- Treaty of Versailles

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

The Korean War and the Battle of Chosin Reservoir

Written by: Bill of Rights Institute

By the end of this section, you will:.

- Explain the continuities and changes in Cold War policies from 1945 to 1980

Suggested Sequencing

Use this narrative with the Truman Intervenes in Korea Decision Point, the Truman Fires General Douglas MacArthur Decision Point, and the Harry S. Truman, “Truman Doctrine” Address, March 1947 Primary Source to have students analyze the United States’ involvement in the conflict.

On June 25, 1950, North Korea invaded South Korea and rapidly swept through the nation until it controlled all but a small perimeter around Pusan at the southern tip of the Korean Peninsula. President Harry Truman was concerned about containing Soviet expansion because of the Russian explosion of an atomic bomb and the fall of China to communism the year before. He secured an authorization of force from the United Nations rather than Congress because he considered his planned intervention in South Korea to be a “police action.” General Douglas MacArthur was named supreme commander of a U.N. coalition of forces led by the United States as the nation went to war.

The U.N. armies counterattacked the North Koreans and gained back much of the territory belonging to the South. On September 15, 1950, the First Marine Division under General Oliver Prince Smith made an amphibious landing at Inchon behind enemy lines and quickly took control of Seoul, the capital of South Korea, with the X Corps of the U.S. Army. Not satisfied with regaining South Korea, General MacArthur secured support from the U.N. and the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, and permission from President Truman to send American and allied troops past the 38th parallel and into North Korea.

On October 5, Chinese Foreign Minister Chou En-lai warned that if U.N. troops crossed the 38th Parallel into North Korea, China would intervene in the war. MacArthur shrugged off the warning, and U.N. forces took the North Korean capital, Pyongyang, two weeks later. MacArthur then sent his forces farther north in several columns toward the Yalu River, on the border with China.

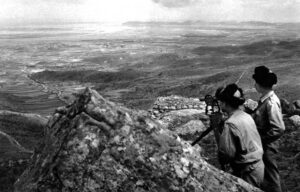

The map shows the northern advance of U.N. forces past the 38th Parallel toward the Chinese border.

The plan was for the First Marine Division to push its way to the objective of the Yalu along the northeastern part of the peninsula, through the forbidding Taebaek Mountains and supported by the 1st Marine Air Wing and the 11th Artillery. MacArthur described the area as a “merciless wasteland . . . locked in a silent death grip of snow and ice.”

The Marines and Army troops sailed to Wonsan in North Korea, where they disembarked 100 miles north of the 38th parallel. General Smith opposed the plan to march through the Taebaeks because of the arctic temperatures, narrow roads vulnerable to ambush, and thin supply lines likely to be cut. He was also concerned about Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and military reports of contact with the Chinese, but MacArthur was unworried and urged the Marines forward.

From October 19 to 25, approximately 300,000 battle-hardened Chinese troops who had fought in the Chinese Civil War crossed the Yalu. The Chinese Ninth Army Group, 120,000 soldiers strong, swarmed into the Taebaeks. They camouflaged their movements by traveling at night and covering themselves with white sheets in the snow. The Chinese planned to use their numbers to overwhelm the Marines, who had superior firepower.

General Song Shilun, center, was the commander of the Chinese Ninth Army Group at Chosin, Korea, in 1950.

Just before midnight on November 2, the Chinese attacked the 3,000 Marines of the 7th Regiment under Colonel Homer Litzenberg at the village of Sudong, on the road to Hagaru-ri. The Chinese forces surged in human waves that were annihilated by Marine machine guns, rifles, and mortars. The Marines killed almost 1,000 Chinese and lost only 61 of their own. The enemy disappeared after the probing attack, having gained valuable information about the Marines’ capabilities as well as about U.S. and South Korean armies elsewhere in the area.

General Smith selected Hagaru-ri village as a forward base on the southeastern tip of the Chosin Reservoir. He ordered the artillery to deploy their batteries and the engineers to build an airstrip and supply depot. Smith sent Marines to cover East Hill, the heights overlooking the village. Marine infantrymen of the 7th Regiment Easy Company marched 14 miles to the northwest, to Hill 1282, which had a commanding view of the village of Yudam-ni. Fox Company was given the critical job of occupying a hill next to Toktong Pass, the only road linking Hagaru-ri to Yudam-ni, so their fellow Marines could be supplied and would not be cut off. They arrived on November 27 and immediately started digging in, despite biting temperatures of ?25°F with strong winds.

The Fox Company Marines deployed in a horseshoe formation around the perimeter of the hill, anchored to a high embankment in the road. The front units laid out foxholes in a standard formation of two foxholes with one behind. Half the Marines went to sleep in heavy sleeping bags while the other half kept watch. They could not light fires because they had to hide their positions.

At 2:00 a.m., a large formation of Chinese in white uniforms attacked. They blew whistles and bugles and clanged cymbals, relying on sheer numbers rather than surprise. Soon, grenade explosions and machine-gun and rifle fire added to the deafening noise. There were so many Chinese that the Americans did not even aim their weapons. Within minutes, their American front-line positions were overrun and dozens were dead or wounded. Still, they fought back tenaciously.

Privates Hector Cafferata and Ken Benson were in a foxhole together when a grenade landed right on top of them. Benson grabbed it and it exploded in his face, temporarily blinding him. Cafferata fired a machine gun or rifle while Benson reloaded ammunition into empty weapons. Cafferata threw grenades as well and swung his shovel like a baseball bat to knock enemy grenades back down the hill. He was about to throw another one when it exploded in his hand and shredded his fingers. Nevertheless, he kept firing the weapons that Benson handed him. Captain William Barber rallied his troops at the top of the hill and moved among his men under fire to bolster their courage throughout the night.

The story was much the same on Hill 1282 at Yudam-ni, where Easy Company was under heavy attack all night and almost lost the hill until they counterattacked and gained a brief respite. They suffered significant casualties. East Hill on Hagaru-ri was beleaguered as well and barely held. U.S. Army units to the east of the reservoir and South Korean forces farther east were also hit hard during the first night. Chinese casualties totaled nearly 10,000 from these battles the first day.

As the sun rose over the rugged landscape, the exhausted Marines on Fox Hill counted 24 dead, 50 wounded, and three missing, cutting their effective strength by one-third. Captain Barber counted more than 450 enemy dead strewn all over the hill, with almost 100 in front of Cafferata and Benson’s foxhole. The extreme cold had clotted the bleeding from most of their wounds, but it also caused numerous cases of frostbite among the Marines. The soldiers helped the wounded and ate cold rations. Their spirits were lifted by support from airstrikes by Marine Corsairs and artillery barrages. In addition, cargo planes began dropping bundles of medical supplies, food, ammunition, radio batteries, and blankets.

The wounded from the battle at Fox Hill in Korea, 1950, were evacuated by plane to be helped elsewhere.

The Chinese, however, launched massive attacks during the next few nights. As the fighting grew desperate, dozens of wounded Marines in field hospitals gritted their teeth, grabbed a weapon, and straggled back to the fighting. One partially paralyzed man with his spine exposed from a gunshot wound tried to get up and fight but was stopped by a corpsman. Because the Marine Corps abided by the slogan, “Every Marine a rifleman,” cooks, mechanics, and drivers picked up weapons and entered the fray on the various hills.