The Interview Method In Psychology

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Interviews involve a conversation with a purpose, but have some distinct features compared to ordinary conversation, such as being scheduled in advance, having an asymmetry in outcome goals between interviewer and interviewee, and often following a question-answer format.

Interviews are different from questionnaires as they involve social interaction. Unlike questionnaire methods, researchers need training in interviewing (which costs money).

How Do Interviews Work?

Researchers can ask different types of questions, generating different types of data . For example, closed questions provide people with a fixed set of responses, whereas open questions allow people to express what they think in their own words.

The researcher will often record interviews, and the data will be written up as a transcript (a written account of interview questions and answers) which can be analyzed later.

It should be noted that interviews may not be the best method for researching sensitive topics (e.g., truancy in schools, discrimination, etc.) as people may feel more comfortable completing a questionnaire in private.

There are different types of interviews, with a key distinction being the extent of structure. Semi-structured is most common in psychology research. Unstructured interviews have a free-flowing style, while structured interviews involve preset questions asked in a particular order.

Structured Interview

A structured interview is a quantitative research method where the interviewer a set of prepared closed-ended questions in the form of an interview schedule, which he/she reads out exactly as worded.

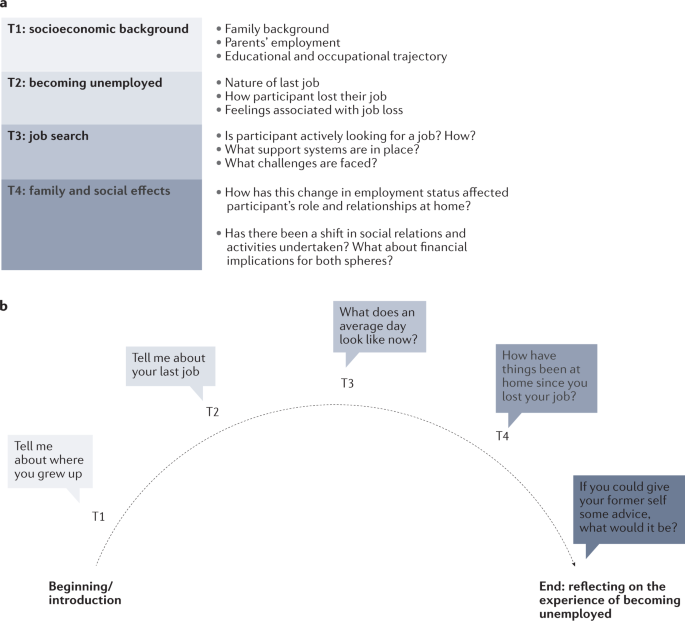

Interviews schedules have a standardized format, meaning the same questions are asked to each interviewee in the same order (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1. An example of an interview schedule

The interviewer will not deviate from the interview schedule (except to clarify the meaning of the question) or probe beyond the answers received. Replies are recorded on a questionnaire, and the order and wording of questions, and sometimes the range of alternative answers, is preset by the researcher.

A structured interview is also known as a formal interview (like a job interview).

- Structured interviews are easy to replicate as a fixed set of closed questions are used, which are easy to quantify – this means it is easy to test for reliability .

- Structured interviews are fairly quick to conduct which means that many interviews can take place within a short amount of time. This means a large sample can be obtained, resulting in the findings being representative and having the ability to be generalized to a large population.

Limitations

- Structured interviews are not flexible. This means new questions cannot be asked impromptu (i.e., during the interview), as an interview schedule must be followed.

- The answers from structured interviews lack detail as only closed questions are asked, which generates quantitative data . This means a researcher won’t know why a person behaves a certain way.

Unstructured Interview

Unstructured interviews do not use any set questions, instead, the interviewer asks open-ended questions based on a specific research topic, and will try to let the interview flow like a natural conversation. The interviewer modifies his or her questions to suit the candidate’s specific experiences.

Unstructured interviews are sometimes referred to as ‘discovery interviews’ and are more like a ‘guided conservation’ than a strictly structured interview. They are sometimes called informal interviews.

Unstructured interviews are most useful in qualitative research to analyze attitudes and values. Though they rarely provide a valid basis for generalization, their main advantage is that they enable the researcher to probe social actors’ subjective points of view.

Interviewer Self-Disclosure

Interviewer self-disclosure involves the interviewer revealing personal information or opinions during the research interview. This may increase rapport but risks changing dynamics away from a focus on facilitating the interviewee’s account.

In unstructured interviews, the informal conversational style may deliberately include elements of interviewer self-disclosure, mirroring ordinary conversation dynamics.

Interviewer self-disclosure risks changing the dynamics away from facilitation of interviewee accounts. It should not be ruled out entirely but requires skillful handling informed by reflection.

- An informal interviewing style with some interviewer self-disclosure may increase rapport and participant openness. However, it also increases the chance of the participant converging opinions with the interviewer.

- Complete interviewer neutrality is unlikely. However, excessive informality and self-disclosure risk the interview becoming more of an ordinary conversation and producing consensus accounts.

- Overly personal disclosures could also be seen as irrelevant and intrusive by participants. They may invite increased intimacy on uncomfortable topics.

- The safest approach seems to be to avoid interviewer self-disclosures in most cases. Where an informal style is used, disclosures require careful judgment and substantial interviewing experience.

- If asked for personal opinions during an interview, the interviewer could highlight the defined roles and defer that discussion until after the interview.

- Unstructured interviews are more flexible as questions can be adapted and changed depending on the respondents’ answers. The interview can deviate from the interview schedule.

- Unstructured interviews generate qualitative data through the use of open questions. This allows the respondent to talk in some depth, choosing their own words. This helps the researcher develop a real sense of a person’s understanding of a situation.

- They also have increased validity because it gives the interviewer the opportunity to probe for a deeper understanding, ask for clarification & allow the interviewee to steer the direction of the interview, etc. Interviewers have the chance to clarify any questions of participants during the interview.

- It can be time-consuming to conduct an unstructured interview and analyze the qualitative data (using methods such as thematic analysis).

- Employing and training interviewers is expensive and not as cheap as collecting data via questionnaires . For example, certain skills may be needed by the interviewer. These include the ability to establish rapport and knowing when to probe.

- Interviews inevitably co-construct data through researchers’ agenda-setting and question-framing. Techniques like open questions provide only limited remedies.

Focus Group Interview

Focus group interview is a qualitative approach where a group of respondents are interviewed together, used to gain an in‐depth understanding of social issues.

This type of interview is often referred to as a focus group because the job of the interviewer ( or moderator ) is to bring the group to focus on the issue at hand. Initially, the goal was to reach a consensus among the group, but with the development of techniques for analyzing group qualitative data, there is less emphasis on consensus building.

The method aims to obtain data from a purposely selected group of individuals rather than from a statistically representative sample of a broader population.

The role of the interview moderator is to make sure the group interacts with each other and do not drift off-topic. Ideally, the moderator will be similar to the participants in terms of appearance, have adequate knowledge of the topic being discussed, and exercise mild unobtrusive control over dominant talkers and shy participants.

A researcher must be highly skilled to conduct a focus group interview. For example, the moderator may need certain skills, including the ability to establish rapport and know when to probe.

- Group interviews generate qualitative narrative data through the use of open questions. This allows the respondents to talk in some depth, choosing their own words. This helps the researcher develop a real sense of a person’s understanding of a situation. Qualitative data also includes observational data, such as body language and facial expressions.

- Group responses are helpful when you want to elicit perspectives on a collective experience, encourage diversity of thought, reduce researcher bias, and gather a wider range of contextualized views.

- They also have increased validity because some participants may feel more comfortable being with others as they are used to talking in groups in real life (i.e., it’s more natural).

- When participants have common experiences, focus groups allow them to build on each other’s comments to provide richer contextual data representing a wider range of views than individual interviews.

- Focus groups are a type of group interview method used in market research and consumer psychology that are cost – effective for gathering the views of consumers .

- The researcher must ensure that they keep all the interviewees” details confidential and respect their privacy. This is difficult when using a group interview. For example, the researcher cannot guarantee that the other people in the group will keep information private.

- Group interviews are less reliable as they use open questions and may deviate from the interview schedule, making them difficult to repeat.

- It is important to note that there are some potential pitfalls of focus groups, such as conformity, social desirability, and oppositional behavior, that can reduce the usefulness of the data collected.

For example, group interviews may sometimes lack validity as participants may lie to impress the other group members. They may conform to peer pressure and give false answers.

To avoid these pitfalls, the interviewer needs to have a good understanding of how people function in groups as well as how to lead the group in a productive discussion.

Semi-Structured Interview

Semi-structured interviews lie between structured and unstructured interviews. The interviewer prepares a set of same questions to be answered by all interviewees. Additional questions might be asked during the interview to clarify or expand certain issues.

In semi-structured interviews, the interviewer has more freedom to digress and probe beyond the answers. The interview guide contains a list of questions and topics that need to be covered during the conversation, usually in a particular order.

Semi-structured interviews are most useful to address the ‘what’, ‘how’, and ‘why’ research questions. Both qualitative and quantitative analyses can be performed on data collected during semi-structured interviews.

- Semi-structured interviews allow respondents to answer more on their terms in an informal setting yet provide uniform information making them ideal for qualitative analysis.

- The flexible nature of semi-structured interviews allows ideas to be introduced and explored during the interview based on the respondents’ answers.

- Semi-structured interviews can provide reliable and comparable qualitative data. Allows the interviewer to probe answers, where the interviewee is asked to clarify or expand on the answers provided.

- The data generated remain fundamentally shaped by the interview context itself. Analysis rarely acknowledges this endemic co-construction.

- They are more time-consuming (to conduct, transcribe, and analyze) than structured interviews.

- The quality of findings is more dependent on the individual skills of the interviewer than in structured interviews. Skill is required to probe effectively while avoiding biasing responses.

The Interviewer Effect

Face-to-face interviews raise methodological problems. These stem from the fact that interviewers are themselves role players, and their perceived status may influence the replies of the respondents.

Because an interview is a social interaction, the interviewer’s appearance or behavior may influence the respondent’s answers. This is a problem as it can bias the results of the study and make them invalid.

For example, the gender, ethnicity, body language, age, and social status of the interview can all create an interviewer effect. If there is a perceived status disparity between the interviewer and the interviewee, the results of interviews have to be interpreted with care. This is pertinent for sensitive topics such as health.

For example, if a researcher was investigating sexism amongst males, would a female interview be preferable to a male? It is possible that if a female interviewer was used, male participants might lie (i.e., pretend they are not sexist) to impress the interviewer, thus creating an interviewer effect.

Flooding interviews with researcher’s agenda

The interactional nature of interviews means the researcher fundamentally shapes the discourse, rather than just neutrally collecting it. This shapes what is talked about and how participants can respond.

- The interviewer’s assumptions, interests, and categories don’t just shape the specific interview questions asked. They also shape the framing, task instructions, recruitment, and ongoing responses/prompts.

- This flooding of the interview interaction with the researcher’s agenda makes it very difficult to separate out what comes from the participant vs. what is aligned with the interviewer’s concerns.

- So the participant’s talk ends up being fundamentally shaped by the interviewer rather than being a more natural reflection of the participant’s own orientations or practices.

- This effect is hard to avoid because interviews inherently involve the researcher setting an agenda. But it does mean the talk extracted may say more about the interview process than the reality it is supposed to reflect.

Interview Design

First, you must choose whether to use a structured or non-structured interview.

Characteristics of Interviewers

Next, you must consider who will be the interviewer, and this will depend on what type of person is being interviewed. There are several variables to consider:

- Gender and age : This can greatly affect respondents’ answers, particularly on personal issues.

- Personal characteristics : Some people are easier to get on with than others. Also, the interviewer’s accent and appearance (e.g., clothing) can affect the rapport between the interviewer and interviewee.

- Language : The interviewer’s language should be appropriate to the vocabulary of the group of people being studied. For example, the researcher must change the questions’ language to match the respondents’ social background” age / educational level / social class/ethnicity, etc.

- Ethnicity : People may have difficulty interviewing people from different ethnic groups.

- Interviewer expertise should match research sensitivity – inexperienced students should avoid interviewing highly vulnerable groups.

Interview Location

The location of a research interview can influence the way in which the interviewer and interviewee relate and may exaggerate a power dynamic in one direction or another. It is usual to offer interviewees a choice of location as part of facilitating their comfort and encouraging participation.

However, the safety of the interviewer is an overriding consideration and, as mentioned, a minimal requirement should be that a responsible person knows where the interviewer has gone and when they are due back.

Remote Interviews

The COVID-19 pandemic necessitated remote interviewing for research continuity. However online interview platforms provide increased flexibility even under normal conditions.

They enable access to participant groups across geographical distances without travel costs or arrangements. Online interviews can be efficiently scheduled to align with researcher and interviewee availability.

There are practical considerations in setting up remote interviews. Interviewees require access to internet and an online platform such as Zoom, Microsoft Teams or Skype through which to connect.

Certain modifications help build initial rapport in the remote format. Allowing time at the start of the interview for casual conversation while testing audio/video quality helps participants settle in. Minor delays can disrupt turn-taking flow, so alerting participants to speak slightly slower than usual minimizes accidental interruptions.

Keeping remote interviews under an hour avoids fatigue for stare at a screen. Seeking advanced ethical clearance for verbal consent at the interview start saves participant time. Adapting to the remote context shows care for interviewees and aids rich discussion.

However, it remains important to critically reflect on how removing in-person dynamics may shape the co-created data. Perhaps some nuances of trust and disclosure differ over video.

Vulnerable Groups

The interviewer must ensure that they take special care when interviewing vulnerable groups, such as children. For example, children have a limited attention span, so lengthy interviews should be avoided.

Developing an Interview Schedule

An interview schedule is a list of pre-planned, structured questions that have been prepared, to serve as a guide for interviewers, researchers and investigators in collecting information or data about a specific topic or issue.

- List the key themes or topics that must be covered to address your research questions. This will form the basic content.

- Organize the content logically, such as chronologically following the interviewee’s experiences. Place more sensitive topics later in the interview.

- Develop the list of content into actual questions and prompts. Carefully word each question – keep them open-ended, non-leading, and focused on examples.

- Add prompts to remind you to cover areas of interest.

- Pilot test the interview schedule to check it generates useful data and revise as needed.

- Be prepared to refine the schedule throughout data collection as you learn which questions work better.

- Practice skills like asking follow-up questions to get depth and detail. Stay flexible to depart from the schedule when needed.

- Keep questions brief and clear. Avoid multi-part questions that risk confusing interviewees.

- Listen actively during interviews to determine which pre-planned questions can be skipped based on information the participant has already provided.

The key is balancing preparation with the flexibility to adapt questions based on each interview interaction. With practice, you’ll gain skills to conduct productive interviews that obtain rich qualitative data.

The Power of Silence

Strategic use of silence is a key technique to generate interviewee-led data, but it requires judgment about appropriate timing and duration to maintain mutual understanding.

- Unlike ordinary conversation, the interviewer aims to facilitate the interviewee’s contribution without interrupting. This often means resisting the urge to speak at the end of the interviewee’s turn construction units (TCUs).

- Leaving a silence after a TCU encourages the interviewee to provide more material without being led by the interviewer. However, this simple technique requires confidence, as silence can feel socially awkward.

- Allowing longer silences (e.g. 24 seconds) later in interviews can work well, but early on even short silences may disrupt rapport if they cause misalignment between speakers.

- Silence also allows interviewees time to think before answering. Rushing to re-ask or amend questions can limit responses.

- Blunt backchannels like “mm hm” also avoid interrupting flow. Interruptions, especially to finish an interviewee’s turn, are problematic as they make the ownership of perspectives unclear.

- If interviewers incorrectly complete turns, an upside is it can produce extended interviewee narratives correcting the record. However, silence would have been better to let interviewees shape their own accounts.

Interviewing Children

By understanding the unique challenges and employing these solutions, interviewers can create a more child-friendly and effective interview process, promoting accurate and reliable information gathering from young witnesses.

Pitfalls to Avoid

- Speculation and misinterpretation : Children may misinterpret questions due to immature language and memory skills, leading them to speculate or provide inaccurate information . For example, children might not fully grasp the meaning of words like “before” and “after” .

- Limited information : Directive questions often result in brief answers, restricting the child’s opportunity to provide a full and detailed account of the event.

- Children’s desire to cooperate: Children are generally inclined to answer any question posed by an authority figure, even if they don’t understand the question or know the answer. This can result in inaccurate responses or speculation to please the interviewer.

- Language development : Young children may not understand complex vocabulary, grammatical structures, or abstract concepts . For instance, words like “aunt” and “uncle” can be challenging for children because their meaning shifts depending on the speaker.

- Memory capabilities : Children’s memory abilities are still developing, making them more susceptible to memory errors and suggestibility . Questions that repeatedly cue specific details can inadvertently alter their recollections .

- Attention span and fatigue : Children, especially younger ones, have shorter attention spans and tire more easily than adults. Lengthy interviews or those with excessive questioning can lead to fatigue and reduce the quality of their responses.

- Reluctance to talk: Children may be hesitant to talk due to various reasons, such as fear of getting into trouble, an inhibited temperament, distrust of unfamiliar adults, or feeling overwhelmed. This can make it challenging to obtain information from them.

- Adopt a child-centered approach: Interviewers prioritize creating a supportive and less intimidating environment by using techniques tailored to the child’s developmental level and cultural background. This includes using developmentally appropriate language, building rapport, and employing a patient and non-judgmental demeanor.

- Emphasize open-ended questions: Instead of relying heavily on focused questions, interviewers prioritize open-ended prompts that encourage children to provide detailed narratives in their own words. They use open-ended invitations like “Tell me everything that happened” or “What happened next?” to elicit more comprehensive and accurate responses.

- Use a questioning cycle: Interviewers combine open-ended invitations with focused prompts to gather specific details while maintaining a conversational flow. This involves cycling back to broader, open-ended prompts after asking focused questions to ensure a thorough understanding of the situation.

- Provide ample time to respond: Recognizing that children may need more time to process information, interviewers provide sufficient wait time, allowing children to respond at their own pace. This patience helps to reduce pressure and encourages more thoughtful responses.

- Build rapport: Establishing rapport is crucial for creating a safe and comfortable space for children to share their experiences. Interviewers achieve this by engaging in neutral conversations, showing genuine interest in the child’s life, and using a calm and reassuring tone.

- Deliver clear interview instructions: Interviewers provide clear and concise instructions, explaining the ground rules of the interview, emphasizing honesty, and encouraging the child to ask for clarification if needed.

- Use interview aids cautiously: While tools like drawings or diagrams can be helpful, interviewers use them with caution, ensuring they don’t lead or suggest information to the child. These aids are primarily used to clarify or elaborate on information the child has already provided verbally.

- Be prepared for multiple interviews: It’s often necessary to conduct multiple interviews to allow children time to process information and recall additional details. Subsequent interviews provide an opportunity to clarify information and explore inconsistencies.

Recording & Transcription

Design choices.

Design choices around recording and engaging closely with transcripts influence analytic insights, as well as practical feasibility. Weighing up relevant tradeoffs is key.

- Audio recording is standard, but video better captures contextual details, which is useful for some topics/analysis approaches. Participants may find video invasive for sensitive research.

- Digital formats enable the sharing of anonymized clips. Additional microphones reduce audio issues.

- Doing all transcription is time-consuming. Outsourcing can save researcher effort but needs confidentiality assurances. Always carefully check outsourced transcripts.

- Online platform auto-captioning can facilitate rapid analysis, but accuracy limitations mean full transcripts remain ideal. Software cleans up caption file formatting.

- Verbatim transcripts best capture nuanced meaning, but the level of detail needed depends on the analysis approach. Referring back to recordings is still advisable during analysis.

- Transcripts versus recordings highlight different interaction elements. Transcripts make overt disagreements clearer through the wording itself. Recordings better convey tone affiliativeness.

Transcribing Interviews & Focus Groups

Here are the steps for transcribing interviews:

- Play back audio/video files to develop an overall understanding of the interview

- Format the transcription document:

- Add line numbers

- Separate interviewer questions and interviewee responses

- Use formatting like bold, italics, etc. to highlight key passages

- Provide sentence-level clarity in the interviewee’s responses while preserving their authentic voice and word choices

- Break longer passages into smaller paragraphs to help with coding

- If translating the interview to another language, use qualified translators and back-translate where possible

- Select a notation system to indicate pauses, emphasis, laughter, interruptions, etc., and adapt it as needed for your data

- Insert screenshots, photos, or documents discussed in the interview at the relevant point in the transcript

- Read through multiple times, revising formatting and notations

- Double-check the accuracy of transcription against audio/videos

- De-identify transcript by removing identifying participant details

The goal is to produce a formatted written record of the verbal interview exchange that captures the meaning and highlights important passages ready for the coding process. Careful transcription is the vital first step in analysis.

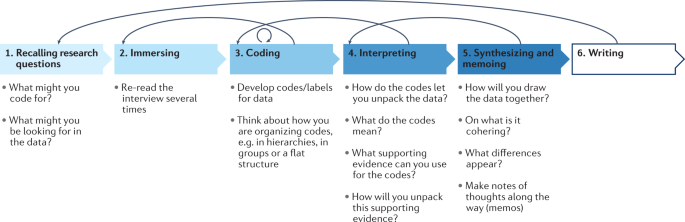

Coding Transcripts

The goal of transcription and coding is to systematically transform interview responses into a set of codes and themes that capture key concepts, experiences and beliefs expressed by participants. Taking care with transcription and coding procedures enhances the validity of qualitative analysis .

- Read through the transcript multiple times to become immersed in the details

- Identify manifest/obvious codes and latent/underlying meaning codes

- Highlight insightful participant quotes that capture key concepts (in vivo codes)

- Create a codebook to organize and define codes with examples

- Use an iterative cycle of inductive (data-driven) coding and deductive (theory-driven) coding

- Refine codebook with clear definitions and examples as you code more transcripts

- Collaborate with other coders to establish the reliability of codes

Ethical Issues

Informed consent.

The participant information sheet must give potential interviewees a good idea of what is involved if taking part in the research.

This will include the general topics covered in the interview, where the interview might take place, how long it is expected to last, how it will be recorded, the ways in which participants’ anonymity will be managed, and incentives offered.

It might be considered good practice to consider true informed consent in interview research to require two distinguishable stages:

- Consent to undertake and record the interview and

- Consent to use the material in research after the interview has been conducted and the content known, or even after the interviewee has seen a copy of the transcript and has had a chance to remove sections, if desired.

Power and Vulnerability

- Early feminist views that sensitivity could equalize power differences are likely naive. The interviewer and interviewee inhabit different knowledge spheres and social categories, indicating structural disparities.

- Power fluctuates within interviews. Researchers rely on participation, yet interviewees control openness and can undermine data collection. Assumptions should be avoided.

- Interviews on sensitive topics may feel like quasi-counseling. Interviewers must refrain from dual roles, instead supplying support service details to all participants.

- Interviewees recruited for trauma experiences may reveal more than anticipated. While generating analytic insights, this risks leaving them feeling exposed.

- Ultimately, power balances resist reconciliation. But reflexively analyzing operations of power serves to qualify rather than nullify situtated qualitative accounts.

Some groups, like those with mental health issues, extreme views, or criminal backgrounds, risk being discredited – treated skeptically by researchers.

This creates tensions with qualitative approaches, often having an empathetic ethos seeking to center subjective perspectives. Analysis should balance openness to offered accounts with critically examining stakes and motivations behind them.

Potter, J., & Hepburn, A. (2005). Qualitative interviews in psychology: Problems and possibilities. Qualitative research in Psychology , 2 (4), 281-307.

Houtkoop-Steenstra, H. (2000). Interaction and the standardized survey interview: The living questionnaire . Cambridge University Press

Madill, A. (2011). Interaction in the semi-structured interview: A comparative analysis of the use of and response to indirect complaints. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 8 (4), 333–353.

Maryudi, A., & Fisher, M. (2020). The power in the interview: A practical guide for identifying the critical role of actor interests in environment research. Forest and Society, 4 (1), 142–150

O’Key, V., Hugh-Jones, S., & Madill, A. (2009). Recruiting and engaging with people in deprived locales: Interviewing families about their eating patterns. Social Psychological Review, 11 (20), 30–35.

Puchta, C., & Potter, J. (2004). Focus group practice . Sage.

Schaeffer, N. C. (1991). Conversation with a purpose— Or conversation? Interaction in the standardized interview. In P. P. Biemer, R. M. Groves, L. E. Lyberg, & N. A. Mathiowetz (Eds.), Measurement errors in surveys (pp. 367–391). Wiley.

Silverman, D. (1973). Interview talk: Bringing off a research instrument. Sociology, 7 (1), 31–48.

Interview Method

- First Online: 27 October 2022

Cite this chapter

- Hazreena Hussein 4

3525 Accesses

2 Citations

The rationale of research interviews is to gain people’s knowledge, views, and experiences, which are meaningful in understanding social realities. Although some research interviews are time-consuming, researchers can interact and communicate while developing a rapport with people to find out these facts—something observations or surveys can never do. How a response from an interview is made (tone of voice, facial expression, hesitation) can feed information that a written response would conceal. Having a good audio quality recorder would be of great assistance. However, if the respondent refuses to be recorded, researchers should practise note-taking. Researchers need to be careful of what and how to ask, as some information may be controversial and confidential. Interviews are a highly subjective method, and the danger of bias always exists.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Qualitative Interviewing

Interviewing in Qualitative Research

Abramson, J. S. & Mizrahi, T. (1994). Examining social work/physician collaboration: An application of grounded theory methods. Qualitative Studies in Social Work Research , 28–48.

Google Scholar

Ahmed, V., Opolu, A., & Aziz, Z. (Eds.). (2016). Research methodology in the built environment: A selection of case studies . Taylor & Francis.

Buckeldee, J. (1994). Interviewing carers in their own homes. In The research experience in nursing (pp. 101–114). Chapman and Hall.

Hussein, H. (2009). Therapeutic intervention: Using the sensory garden to enhance the quality of life for children with special needs . Unpublished doctoral.

Hussein, H. (2012a). Affordances of sensory garden towards learning and self-development of special schooled children. International Journal of Psychological Studies, 4 (1), 135–149.

Article Google Scholar

Hussein, H. (2012b). The influence of sensory gardens on the behaviour of children with special educational needs. Procedia—Social and Behavioural Sciences, 38 , 343–354.

Hussein, H., & Daud, M. N. (2015). Examining the methods for investigating behavioural clues of special-schooled children. Field Methods, 27 (1), 97–112.

Islam, M. R. & Faruque, C. J. (Eds.). (2016). Qualitative research: Tools and techniques (eds.). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Mason, J. (1996). Qualitative researching . Saga.

Zeisel, J. (1981). Inquiry by design: Tools for environment-behaviour research . University Press.

Zimring, C. M. (1987). Evaluation of designed environments: Methods for post-occupancy evaluation. In Bechtel, Marans & Mitchelson (Eds.), Methods in environmental and behavioural research . Van Nostrand.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre For Sustainable Urban Planning & Real Estate, Faculty of Built Environment, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Hazreena Hussein

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Hazreena Hussein .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Centre for Family and Child Studies, Research Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Sharjah, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

M. Rezaul Islam

Department of Development Studies, University of Dhaka, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Niaz Ahmed Khan

Department of Social Work, School of Humanities, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

Rajendra Baikady

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Hussein, H. (2022). Interview Method. In: Islam, M.R., Khan, N.A., Baikady, R. (eds) Principles of Social Research Methodology. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-5441-2_14

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-5441-2_14

Published : 27 October 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-19-5219-7

Online ISBN : 978-981-19-5441-2

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Types of Interviews in Research | Guide & Examples

Types of Interviews in Research | Guide & Examples

Published on 4 May 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on 10 October 2022.

An interview is a qualitative research method that relies on asking questions in order to collect data . Interviews involve two or more people, one of whom is the interviewer asking the questions.

There are several types of interviews, often differentiated by their level of structure. Structured interviews have predetermined questions asked in a predetermined order. Unstructured interviews are more free-flowing, and semi-structured interviews fall in between.

Interviews are commonly used in market research, social science, and ethnographic research.

Table of contents

What is a structured interview, what is a semi-structured interview, what is an unstructured interview, what is a focus group, examples of interview questions, advantages and disadvantages of interviews, frequently asked questions about types of interviews.

Structured interviews have predetermined questions in a set order. They are often closed-ended, featuring dichotomous (yes/no) or multiple-choice questions. While open-ended structured interviews exist, they are much less common. The types of questions asked make structured interviews a predominantly quantitative tool.

Asking set questions in a set order can help you see patterns among responses, and it allows you to easily compare responses between participants while keeping other factors constant. This can mitigate biases and lead to higher reliability and validity. However, structured interviews can be overly formal, as well as limited in scope and flexibility.

- You feel very comfortable with your topic. This will help you formulate your questions most effectively.

- You have limited time or resources. Structured interviews are a bit more straightforward to analyse because of their closed-ended nature, and can be a doable undertaking for an individual.

- Your research question depends on holding environmental conditions between participants constant

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Semi-structured interviews are a blend of structured and unstructured interviews. While the interviewer has a general plan for what they want to ask, the questions do not have to follow a particular phrasing or order.

Semi-structured interviews are often open-ended, allowing for flexibility, but follow a predetermined thematic framework, giving a sense of order. For this reason, they are often considered ‘the best of both worlds’.

However, if the questions differ substantially between participants, it can be challenging to look for patterns, lessening the generalisability and validity of your results.

- You have prior interview experience. It’s easier than you think to accidentally ask a leading question when coming up with questions on the fly. Overall, spontaneous questions are much more difficult than they may seem.

- Your research question is exploratory in nature. The answers you receive can help guide your future research.

An unstructured interview is the most flexible type of interview. The questions and the order in which they are asked are not set. Instead, the interview can proceed more spontaneously, based on the participant’s previous answers.

Unstructured interviews are by definition open-ended. This flexibility can help you gather detailed information on your topic, while still allowing you to observe patterns between participants.

However, so much flexibility means that they can be very challenging to conduct properly. You must be very careful not to ask leading questions, as biased responses can lead to lower reliability or even invalidate your research.

- You have a solid background in your research topic and have conducted interviews before

- Your research question is exploratory in nature, and you are seeking descriptive data that will deepen and contextualise your initial hypotheses

- Your research necessitates forming a deeper connection with your participants, encouraging them to feel comfortable revealing their true opinions and emotions

A focus group brings together a group of participants to answer questions on a topic of interest in a moderated setting. Focus groups are qualitative in nature and often study the group’s dynamic and body language in addition to their answers. Responses can guide future research on consumer products and services, human behaviour, or controversial topics.

Focus groups can provide more nuanced and unfiltered feedback than individual interviews and are easier to organise than experiments or large surveys. However, their small size leads to low external validity and the temptation as a researcher to ‘cherry-pick’ responses that fit your hypotheses.

- Your research focuses on the dynamics of group discussion or real-time responses to your topic

- Your questions are complex and rooted in feelings, opinions, and perceptions that cannot be answered with a ‘yes’ or ‘no’

- Your topic is exploratory in nature, and you are seeking information that will help you uncover new questions or future research ideas

Depending on the type of interview you are conducting, your questions will differ in style, phrasing, and intention. Structured interview questions are set and precise, while the other types of interviews allow for more open-endedness and flexibility.

Here are some examples.

- Semi-structured

- Unstructured

- Focus group

- Do you like dogs? Yes/No

- Do you associate dogs with feeling: happy; somewhat happy; neutral; somewhat unhappy; unhappy

- If yes, name one attribute of dogs that you like.

- If no, name one attribute of dogs that you don’t like.

- What feelings do dogs bring out in you?

- When you think more deeply about this, what experiences would you say your feelings are rooted in?

Interviews are a great research tool. They allow you to gather rich information and draw more detailed conclusions than other research methods, taking into consideration nonverbal cues, off-the-cuff reactions, and emotional responses.

However, they can also be time-consuming and deceptively challenging to conduct properly. Smaller sample sizes can cause their validity and reliability to suffer, and there is an inherent risk of interviewer effect arising from accidentally leading questions.

Here are some advantages and disadvantages of each type of interview that can help you decide if you’d like to utilise this research method.

The four most common types of interviews are:

- Structured interviews : The questions are predetermined in both topic and order.

- Semi-structured interviews : A few questions are predetermined, but other questions aren’t planned.

- Unstructured interviews : None of the questions are predetermined.

- Focus group interviews : The questions are presented to a group instead of one individual.

A structured interview is a data collection method that relies on asking questions in a set order to collect data on a topic. They are often quantitative in nature. Structured interviews are best used when:

- You already have a very clear understanding of your topic. Perhaps significant research has already been conducted, or you have done some prior research yourself, but you already possess a baseline for designing strong structured questions.

- You are constrained in terms of time or resources and need to analyse your data quickly and efficiently

- Your research question depends on strong parity between participants, with environmental conditions held constant

More flexible interview options include semi-structured interviews , unstructured interviews , and focus groups .

A semi-structured interview is a blend of structured and unstructured types of interviews. Semi-structured interviews are best used when:

- You have prior interview experience. Spontaneous questions are deceptively challenging, and it’s easy to accidentally ask a leading question or make a participant uncomfortable.

- Your research question is exploratory in nature. Participant answers can guide future research questions and help you develop a more robust knowledge base for future research.

An unstructured interview is the most flexible type of interview, but it is not always the best fit for your research topic.

Unstructured interviews are best used when:

- You are an experienced interviewer and have a very strong background in your research topic, since it is challenging to ask spontaneous, colloquial questions

- Your research question is exploratory in nature. While you may have developed hypotheses, you are open to discovering new or shifting viewpoints through the interview process.

- You are seeking descriptive data, and are ready to ask questions that will deepen and contextualise your initial thoughts and hypotheses

- Your research depends on forming connections with your participants and making them feel comfortable revealing deeper emotions, lived experiences, or thoughts

The interviewer effect is a type of bias that emerges when a characteristic of an interviewer (race, age, gender identity, etc.) influences the responses given by the interviewee.

There is a risk of an interviewer effect in all types of interviews , but it can be mitigated by writing really high-quality interview questions.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

George, T. (2022, October 10). Types of Interviews in Research | Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 21 October 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/types-of-interviews/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, data collection methods | step-by-step guide & examples, face validity | guide with definition & examples, construct validity | definition, types, & examples.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 15 September 2022

Interviews in the social sciences

- Eleanor Knott ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9131-3939 1 ,

- Aliya Hamid Rao ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0674-4206 1 ,

- Kate Summers ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9964-0259 1 &

- Chana Teeger ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5046-8280 1

Nature Reviews Methods Primers volume 2 , Article number: 73 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

748k Accesses

104 Citations

190 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Interdisciplinary studies

In-depth interviews are a versatile form of qualitative data collection used by researchers across the social sciences. They allow individuals to explain, in their own words, how they understand and interpret the world around them. Interviews represent a deceptively familiar social encounter in which people interact by asking and answering questions. They are, however, a very particular type of conversation, guided by the researcher and used for specific ends. This dynamic introduces a range of methodological, analytical and ethical challenges, for novice researchers in particular. In this Primer, we focus on the stages and challenges of designing and conducting an interview project and analysing data from it, as well as strategies to overcome such challenges.

Similar content being viewed by others

The fundamental importance of method to theory

How ‘going online’ mediates the challenges of policy elite interviews

Participatory action research

Introduction.

In-depth interviews are a qualitative research method that follow a deceptively familiar logic of human interaction: they are conversations where people talk with each other, interact and pose and answer questions 1 . An interview is a specific type of interaction in which — usually and predominantly — a researcher asks questions about someone’s life experience, opinions, dreams, fears and hopes and the interview participant answers the questions 1 .

Interviews will often be used as a standalone method or combined with other qualitative methods, such as focus groups or ethnography, or quantitative methods, such as surveys or experiments. Although interviewing is a frequently used method, it should not be viewed as an easy default for qualitative researchers 2 . Interviews are also not suited to answering all qualitative research questions, but instead have specific strengths that should guide whether or not they are deployed in a research project. Whereas ethnography might be better suited to trying to observe what people do, interviews provide a space for extended conversations that allow the researcher insights into how people think and what they believe. Quantitative surveys also give these kinds of insights, but they use pre-determined questions and scales, privileging breadth over depth and often overlooking harder-to-reach participants.

In-depth interviews can take many different shapes and forms, often with more than one participant or researcher. For example, interviews might be highly structured (using an almost survey-like interview guide), entirely unstructured (taking a narrative and free-flowing approach) or semi-structured (using a topic guide ). Researchers might combine these approaches within a single project depending on the purpose of the interview and the characteristics of the participant. Whatever form the interview takes, researchers should be mindful of the dynamics between interviewer and participant and factor these in at all stages of the project.

In this Primer, we focus on the most common type of interview: one researcher taking a semi-structured approach to interviewing one participant using a topic guide. Focusing on how to plan research using interviews, we discuss the necessary stages of data collection. We also discuss the stages and thought-process behind analysing interview material to ensure that the richness and interpretability of interview material is maintained and communicated to readers. The Primer also tracks innovations in interview methods and discusses the developments we expect over the next 5–10 years.

We wrote this Primer as researchers from sociology, social policy and political science. We note our disciplinary background because we acknowledge that there are disciplinary differences in how interviews are approached and understood as a method.

Experimentation

Here we address research design considerations and data collection issues focusing on topic guide construction and other pragmatics of the interview. We also explore issues of ethics and reflexivity that are crucial throughout the research project.

Research design

Participant selection.

Participants can be selected and recruited in various ways for in-depth interview studies. The researcher must first decide what defines the people or social groups being studied. Often, this means moving from an abstract theoretical research question to a more precise empirical one. For example, the researcher might be interested in how people talk about race in contexts of diversity. Empirical settings in which this issue could be studied could include schools, workplaces or adoption agencies. The best research designs should clearly explain why the particular setting was chosen. Often there are both intrinsic and extrinsic reasons for choosing to study a particular group of people at a specific time and place 3 . Intrinsic motivations relate to the fact that the research is focused on an important specific social phenomenon that has been understudied. Extrinsic motivations speak to the broader theoretical research questions and explain why the case at hand is a good one through which to address them empirically.

Next, the researcher needs to decide which types of people they would like to interview. This decision amounts to delineating the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study. The criteria might be based on demographic variables, like race or gender, but they may also be context-specific, for example, years of experience in an organization. These should be decided based on the research goals. Researchers should be clear about what characteristics would make an individual a candidate for inclusion in the study (and what would exclude them).

The next step is to identify and recruit the study’s sample . Usually, many more people fit the inclusion criteria than can be interviewed. In cases where lists of potential participants are available, the researcher might want to employ stratified sampling , dividing the list by characteristics of interest before sampling.

When there are no lists, researchers will often employ purposive sampling . Many researchers consider purposive sampling the most useful mode for interview-based research since the number of interviews to be conducted is too small to aim to be statistically representative 4 . Instead, the aim is not breadth, via representativeness, but depth via rich insights about a set of participants. In addition to purposive sampling, researchers often use snowball sampling . Both purposive and snowball sampling can be combined with quota sampling . All three types of sampling aim to ensure a variety of perspectives within the confines of a research project. A goal for in-depth interview studies can be to sample for range, being mindful of recruiting a diversity of participants fitting the inclusion criteria.

Study design

The total number of interviews depends on many factors, including the population studied, whether comparisons are to be made and the duration of interviews. Studies that rely on quota sampling where explicit comparisons are made between groups will require a larger number of interviews than studies focused on one group only. Studies where participants are interviewed over several hours, days or even repeatedly across years will tend to have fewer participants than those that entail a one-off engagement.

Researchers often stop interviewing when new interviews confirm findings from earlier interviews with no new or surprising insights (saturation) 4 , 5 , 6 . As a criterion for research design, saturation assumes that data collection and analysis are happening in tandem and that researchers will stop collecting new data once there is no new information emerging from the interviews. This is not always possible. Researchers rarely have time for systematic data analysis during data collection and they often need to specify their sample in funding proposals prior to data collection. As a result, researchers often draw on existing reports of saturation to estimate a sample size prior to data collection. These suggest between 12 and 20 interviews per category of participant (although researchers have reported saturation with samples that are both smaller and larger than this) 7 , 8 , 9 . The idea of saturation has been critiqued by many qualitative researchers because it assumes that meaning inheres in the data, waiting to be discovered — and confirmed — once saturation has been reached 7 . In-depth interview data are often multivalent and can give rise to different interpretations. The important consideration is, therefore, not merely how many participants are interviewed, but whether one’s research design allows for collecting rich and textured data that provide insight into participants’ understandings, accounts, perceptions and interpretations.

Sometimes, researchers will conduct interviews with more than one participant at a time. Researchers should consider the benefits and shortcomings of such an approach. Joint interviews may, for example, give researchers insight into how caregivers agree or debate childrearing decisions. At the same time, they may be less adaptive to exploring aspects of caregiving that participants may not wish to disclose to each other. In other cases, there may be more than one person interviewing each participant, such as when an interpreter is used, and so it is important to consider during the research design phase how this might shape the dynamics of the interview.

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews are typically organized around a topic guide comprised of an ordered set of broad topics (usually 3–5). Each topic includes a set of questions that form the basis of the discussion between the researcher and participant (Fig. 1 ). These topics are organized around key concepts that the researcher has identified (for example, through a close study of prior research, or perhaps through piloting a small, exploratory study) 5 .

a | Elaborated topics the researcher wants to cover in the interview and example questions. b | An example topic arc. Using such an arc, one can think flexibly about the order of topics. Considering the main question for each topic will help to determine the best order for the topics. After conducting some interviews, the researcher can move topics around if a different order seems to make sense.

Topic guide

One common way to structure a topic guide is to start with relatively easy, open-ended questions (Table 1 ). Opening questions should be related to the research topic but broad and easy to answer, so that they help to ease the participant into conversation.

After these broad, opening questions, the topic guide may move into topics that speak more directly to the overarching research question. The interview questions will be accompanied by probes designed to elicit concrete details and examples from the participant (see Table 1 ).

Abstract questions are often easier for participants to answer once they have been asked more concrete questions. In our experience, for example, questions about feelings can be difficult for some participants to answer, but when following probes concerning factual experiences these questions can become less challenging. After the main themes of the topic guide have been covered, the topic guide can move onto closing questions. At this stage, participants often repeat something they have said before, although they may sometimes introduce a new topic.

Interviews are especially well suited to gaining a deeper insight into people’s experiences. Getting these insights largely depends on the participants’ willingness to talk to the researcher. We recommend designing open-ended questions that are more likely to elicit an elaborated response and extended reflection from participants rather than questions that can be answered with yes or no.

Questions should avoid foreclosing the possibility that the participant might disagree with the premise of the question. Take for example the question: “Do you support the new family-friendly policies?” This question minimizes the possibility of the participant disagreeing with the premise of this question, which assumes that the policies are ‘family-friendly’ and asks for a yes or no answer. Instead, asking more broadly how a participant feels about the specific policy being described as ‘family-friendly’ (for example, a work-from-home policy) allows them to express agreement, disagreement or impartiality and, crucially, to explain their reasoning 10 .

For an uninterrupted interview that will last between 90 and 120 minutes, the topic guide should be one to two single-spaced pages with questions and probes. Ideally, the researcher will memorize the topic guide before embarking on the first interview. It is fine to carry a printed-out copy of the topic guide but memorizing the topic guide ahead of the interviews can often make the interviewer feel well prepared in guiding the participant through the interview process.

Although the topic guide helps the researcher stay on track with the broad areas they want to cover, there is no need for the researcher to feel tied down by the topic guide. For instance, if a participant brings up a theme that the researcher intended to discuss later or a point the researcher had not anticipated, the researcher may well decide to follow the lead of the participant. The researcher’s role extends beyond simply stating the questions; it entails listening and responding, making split-second decisions about what line of inquiry to pursue and allowing the interview to proceed in unexpected directions.

Optimizing the interview

The ideal place for an interview will depend on the study and what is feasible for participants. Generally, a place where the participant and researcher can both feel relaxed, where the interview can be uninterrupted and where noise or other distractions are limited is ideal. But this may not always be possible and so the researcher needs to be prepared to adapt their plans within what is feasible (and desirable for participants).

Another key tool for the interview is a recording device (assuming that permission for recording has been given). Recording can be important to capture what the participant says verbatim. Additionally, it can allow the researcher to focus on determining what probes and follow-up questions they want to pursue rather than focusing on taking notes. Sometimes, however, a participant may not allow the researcher to record, or the recording may fail. If the interview is not recorded we suggest that the researcher takes brief notes during the interview, if feasible, and then thoroughly make notes immediately after the interview and try to remember the participant’s facial expressions, gestures and tone of voice. Not having a recording of an interview need not limit the researcher from getting analytical value from it.

As soon as possible after each interview, we recommend that the researcher write a one-page interview memo comprising three key sections. The first section should identify two to three important moments from the interview. What constitutes important is up to the researcher’s discretion 9 . The researcher should note down what happened in these moments, including the participant’s facial expressions, gestures, tone of voice and maybe even the sensory details of their surroundings. This exercise is about capturing ethnographic detail from the interview. The second part of the interview memo is the analytical section with notes on how the interview fits in with previous interviews, for example, where the participant’s responses concur or diverge from other responses. The third part consists of a methodological section where the researcher notes their perception of their relationship with the participant. The interview memo allows the researcher to think critically about their positionality and practice reflexivity — key concepts for an ethical and transparent research practice in qualitative methodology 11 , 12 .

Ethics and reflexivity

All elements of an in-depth interview can raise ethical challenges and concerns. Good ethical practice in interview studies often means going beyond the ethical procedures mandated by institutions 13 . While discussions and requirements of ethics can differ across disciplines, here we focus on the most pertinent considerations for interviews across the research process for an interdisciplinary audience.

Ethical considerations prior to interview

Before conducting interviews, researchers should consider harm minimization, informed consent, anonymity and confidentiality, and reflexivity and positionality. It is important for the researcher to develop their own ethical sensitivities and sensibilities by gaining training in interview and qualitative methods, reading methodological and field-specific texts on interviews and ethics and discussing their research plans with colleagues.

Researchers should map the potential harm to consider how this can be minimized. Primarily, researchers should consider harm from the participants’ perspective (Box 1 ). But, it is also important to consider and plan for potential harm to the researcher, research assistants, gatekeepers, future researchers and members of the wider community 14 . Even the most banal of research topics can potentially pose some form of harm to the participant, researcher and others — and the level of harm is often highly context-dependent. For example, a research project on religion in society might have very different ethical considerations in a democratic versus authoritarian research context because of how openly or not such topics can be discussed and debated 15 .

The researcher should consider how they will obtain and record informed consent (for example, written or oral), based on what makes the most sense for their research project and context 16 . Some institutions might specify how informed consent should be gained. Regardless of how consent is obtained, the participant must be made aware of the form of consent, the intentions and procedures of the interview and potential forms of harm and benefit to the participant or community before the interview commences. Moreover, the participant must agree to be interviewed before the interview commences. If, in addition to interviews, the study contains an ethnographic component, it is worth reading around this topic (see, for example, Murphy and Dingwall 17 ). Informed consent must also be gained for how the interview will be recorded before the interview commences. These practices are important to ensure the participant is contributing on a voluntary basis. It is also important to remind participants that they can withdraw their consent at any time during the interview and for a specified period after the interview (to be decided with the participant). The researcher should indicate that participants can ask for anything shared to be off the record and/or not disseminated.

In terms of anonymity and confidentiality, it is standard practice when conducting interviews to agree not to use (or even collect) participants’ names and personal details that are not pertinent to the study. Anonymizing can often be the safer option for minimizing harm to participants as it is hard to foresee all the consequences of de-anonymizing, even if participants agree. Regardless of what a researcher decides, decisions around anonymity must be agreed with participants during the process of gaining informed consent and respected following the interview.

Although not all ethical challenges can be foreseen or planned for 18 , researchers should think carefully — before the interview — about power dynamics, participant vulnerability, emotional state and interactional dynamics between interviewer and participant, even when discussing low-risk topics. Researchers may then wish to plan for potential ethical issues, for example by preparing a list of relevant organizations to which participants can be signposted. A researcher interviewing a participant about debt, for instance, might prepare in advance a list of debt advice charities, organizations and helplines that could provide further support and advice. It is important to remember that the role of an interviewer is as a researcher rather than as a social worker or counsellor because researchers may not have relevant and requisite training in these other domains.

Box 1 Mapping potential forms of harm

Social: researchers should avoid causing any relational detriment to anyone in the course of interviews, for example, by sharing information with other participants or causing interview participants to be shunned or mistreated by their community as a result of participating.

Economic: researchers should avoid causing financial detriment to anyone, for example, by expecting them to pay for transport to be interviewed or to potentially lose their job as a result of participating.

Physical: researchers should minimize the risk of anyone being exposed to violence as a result of the research both from other individuals or from authorities, including police.

Psychological: researchers should minimize the risk of causing anyone trauma (or re-traumatization) or psychological anguish as a result of the research; this includes not only the participant but importantly the researcher themselves and anyone that might read or analyse the transcripts, should they contain triggering information.

Political: researchers should minimize the risk of anyone being exposed to political detriment as a result of the research, such as retribution.

Professional/reputational: researchers should minimize the potential for reputational damage to anyone connected to the research (this includes ensuring good research practices so that any researchers involved are not harmed reputationally by being involved with the research project).

The task here is not to map exhaustively the potential forms of harm that might pertain to a particular research project (that is the researcher’s job and they should have the expertise most suited to mapping such potential harms relative to the specific project) but to demonstrate the breadth of potential forms of harm.

Ethical considerations post-interview

Researchers should consider how interview data are stored, analysed and disseminated. If participants have been offered anonymity and confidentiality, data should be stored in a way that does not compromise this. For example, researchers should consider removing names and any other unnecessary personal details from interview transcripts, password-protecting and encrypting files and using pseudonyms to label and store all interview data. It is also important to address where interview data are taken (for example, across borders in particular where interview data might be of interest to local authorities) and how this might affect the storage of interview data.

Examining how the researcher will represent participants is a paramount ethical consideration both in the planning stages of the interview study and after it has been conducted. Dissemination strategies also need to consider questions of anonymity and representation. In small communities, even if participants are given pseudonyms, it might be obvious who is being described. Anonymizing not only the names of those participating but also the research context is therefore a standard practice 19 . With particularly sensitive data or insights about the participant, it is worth considering describing participants in a more abstract way rather than as specific individuals. These practices are important both for protecting participants’ anonymity but can also affect the ability of the researcher and others to return ethically to the research context and similar contexts 20 .

Reflexivity and positionality

Reflexivity and positionality mean considering the researcher’s role and assumptions in knowledge production 13 . A key part of reflexivity is considering the power relations between the researcher and participant within the interview setting, as well as how researchers might be perceived by participants. Further, researchers need to consider how their own identities shape the kind of knowledge and assumptions they bring to the interview, including how they approach and ask questions and their analysis of interviews (Box 2 ). Reflexivity is a necessary part of developing ethical sensibility as a researcher by adapting and reflecting on how one engages with participants. Participants should not feel judged, for example, when they share information that researchers might disagree with or find objectionable. How researchers deal with uncomfortable moments or information shared by participants is at their discretion, but they should consider how they will react both ahead of time and in the moment.

Researchers can develop their reflexivity by considering how they themselves would feel being asked these interview questions or represented in this way, and then adapting their practice accordingly. There might be situations where these questions are not appropriate in that they unduly centre the researchers’ experiences and worldview. Nevertheless, these prompts can provide a useful starting point for those beginning their reflexive journey and developing an ethical sensibility.

Reflexivity and ethical sensitivities require active reflection throughout the research process. For example, researchers should take care in interview memos and their notes to consider their assumptions, potential preconceptions, worldviews and own identities prior to and after interviews (Box 2 ). Checking in with assumptions can be a way of making sure that researchers are paying close attention to their own theoretical and analytical biases and revising them in accordance with what they learn through the interviews. Researchers should return to these notes (especially when analysing interview material), to try to unpack their own effects on the research process as well as how participants positioned and engaged with them.

Box 2 Aspects to reflect on reflexively

For reflexive engagement, and understanding the power relations being co-constructed and (re)produced in interviews, it is necessary to reflect, at a minimum, on the following.

Ethnicity, race and nationality, such as how does privilege stemming from race or nationality operate between the researcher, the participant and research context (for example, a researcher from a majority community may be interviewing a member of a minority community)

Gender and sexuality, see above on ethnicity, race and nationality

Social class, and in particular the issue of middle-class bias among researchers when formulating research and interview questions

Economic security/precarity, see above on social class and thinking about the researcher’s relative privilege and the source of biases that stem from this

Educational experiences and privileges, see above

Disciplinary biases, such as how the researcher’s discipline/subfield usually approaches these questions, possibly normalizing certain assumptions that might be contested by participants and in the research context

Political and social values

Lived experiences and other dimensions of ourselves that affect and construct our identity as researchers

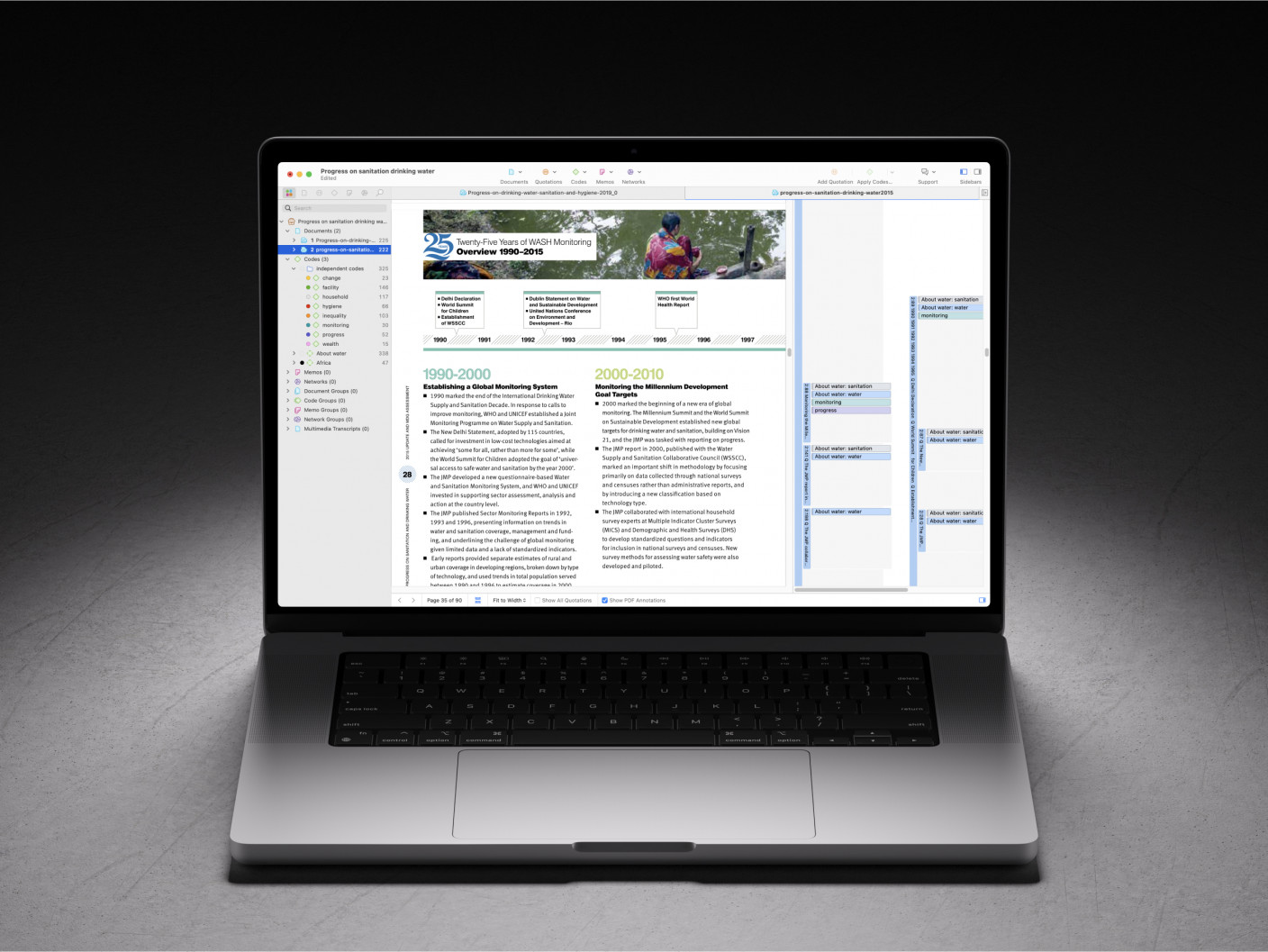

In this section, we discuss the next stage of an interview study, namely, analysing the interview data. Data analysis may begin while more data are being collected. Doing so allows early findings to inform the focus of further data collection, as part of an iterative process across the research project. Here, the researcher is ultimately working towards achieving coherence between the data collected and the findings produced to answer successfully the research question(s) they have set.

The two most common methods used to analyse interview material across the social sciences are thematic analysis 21 and discourse analysis 22 . Thematic analysis is a particularly useful and accessible method for those starting out in analysis of qualitative data and interview material as a method of coding data to develop and interpret themes in the data 21 . Discourse analysis is more specialized and focuses on the role of discourse in society by paying close attention to the explicit, implicit and taken-for-granted dimensions of language and power 22 , 23 . Although thematic and discourse analysis are often discussed as separate techniques, in practice researchers might flexibly combine these approaches depending on the object of analysis. For example, those intending to use discourse analysis might first conduct thematic analysis as a way to organize and systematize the data. The object and intention of analysis might differ (for example, developing themes or interrogating language), but the questions facing the researcher (such as whether to take an inductive or deductive approach to analysis) are similar.

Preparing data