The Political Situation in Pakistan

Cultural development in pakistan, stereotypes and prejudice in pakistan.

The region today referred to as Pakistan was much of its history part of Persian dynasties including what is today referred to as India. Today, Pakistan is an independent country in South Asia to the west of India. But what led to the split and the rise of Pakistan to what it is today? The events that led to the breakaway of Pakistan from greater India were as a result of some misunderstanding between the Muslim and the Hindu population in India. This essay seeks to briefly address the events that led to the split of Pakistan from India and the culture and practices they developed. It will also entail, in brief, the political situation, stereotypes and the prejudices experienced in Pakistan.

The region today referred to as Pakistan was much of its history part of Persian dynasties including what is today referred to as India. Today, Pakistan is an independent country in South Asia to the west of India. But what led to the split and the rise of Pakistan to what it is today? The history of Pakistan can be traced back to as early as the year 1857. In this year, present day India and Pakistan were one nation under British rule. The colony was known as British India. 1857 saw the rise of the Indian rebellion opposing British rule. It was clear that the Indians had had enough of the British rule and wanted to be free. There was however one problem; the Muslim population in India felt that their interests were not being addressed in the same manner that the Indian interests were (Basham, 1954).

As a result, the All Indian Muslim League was formed in 1906. It gained massive popularity in the 1930’s amid fears of neglect and under-representation of Muslims in politics. Muhammad Iqbal saw the need to call for an independent state in northwestern India for the Indian Muslims. After serious debates and confrontations over the issue, the Indians gave in and heeded to the demands of the Muslim population. In 1947, Pakistan gained her independence from British-India as a Muslim majority state. Quite a number of the Muslim population moved to Pakistan while the Indian population moved to India. It was expected that grievances over valuable pieces of land would arise leading to conflicts. This is being experienced to date. Kashmir and Jammu were the most disputed for states and this even led to the Kashmir war of 1948 which ended with Pakistan acquiring only a third of the state and the rest left to India (Aziz, 1969).

The political situation in Pakistan over the years has left a lot to be desired. A mixture of civilian and military rule has been experienced in Pakistan. Occasioned by civil wars, protests and authoritarian rule, the citizens of Pakistan have experienced over five decades of political instability. A ray of hope was however seen in the recent past when the former president Pervez Musharraf stepped down and a civilian president, Asif Ali Zardari, was elected. Pakistan also brought a massive revolution in political thought in 1988, after they elected the first female prime minister of the nation Benazir Bhutto. She was later assassinated in 2007 (Aziz, 1969).

Since 1947, the Pakistani has developed a culture, which has become accustomed as their own. The Pakistani mainly developed the Islamic culture and maintained the practices practiced by Muslims in other areas of the world. What led to this development is the fact that the Pakistani wanted to be identified with other Islamic nations and they wanted a state free from the Hindu practices. An example is the establishment of the Sharia laws, which is a common practice in many Islamic nations. They are governed by the Islamic laws and practices and have to adhere to them.

The cultural heritage of Pakistan developed over a period of time. The fact however is that they moved from the Hindu traditions and cultures to the Islamic traditions and way of life (Ahmad, 1964).

The picture painted of the Pakistani by the media and the rest of the world people is one that creates a lot of acrimony and sorrow among the people of Pakistan. Contrary to the world belief that people from Pakistan are radical Islamists who engage in acts of terror to pass across a message, the Pakistani Muslim are very religious people who advocate for the sanctity of life. The picture painted is that of all non-Muslim individuals being killed by the Pakistani.

Another stereotype that many people have across the world is that of Pakistan being an all-Muslim nation. Islam is not the only religion practiced in Pakistan. A wide majority of the citizens are Muslim but other religions are also accepted in Pakistan.

The last stereotype experienced by the Pakistani is that they are and harbor terrorists in Pakistan. What criterion is used to determine whether one is a terrorist or not? The one predominant in the world today is that of being a Muslim. Pakistan does not advocate for terrorism. People from Pakistan are against any form of terror and as mentioned earlier belief in the sanctity of life (Aziz, 1969).

The prejudice experienced in Pakistan is that against the Hindus. Since the acquisition of independence from British India, Hindus who remained in Pakistan have faced a lot of prejudice and discrimination. In the cultural and the legal sense, Hindus are discriminated against. They are referred ‘un pure’ by the Pakistani people. The other form prejudice is in the legal system where the infamous blasphemy law where people practicing the Hindu traditions and religion are sentenced to death.

All in all, Pakistan is a diverse country with diverse cultures and traditions. It is important that citizens from the country appreciate each other and work hand in hand with each other.

Aziz.A, (1969). An intellectual history of Islam in India . Chicago: Oxford university press.

Ahmad A, (1964). Islamic modernizations in Pakistan and India. New York: Oxford University press.

Basham. A. L, (1954). The wonder that was India . New York: Grove press.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2021, November 20). The Political Situation in Pakistan. https://studycorgi.com/the-political-situation-in-pakistan/

"The Political Situation in Pakistan." StudyCorgi , 20 Nov. 2021, studycorgi.com/the-political-situation-in-pakistan/.

StudyCorgi . (2021) 'The Political Situation in Pakistan'. 20 November.

1. StudyCorgi . "The Political Situation in Pakistan." November 20, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/the-political-situation-in-pakistan/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "The Political Situation in Pakistan." November 20, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/the-political-situation-in-pakistan/.

StudyCorgi . 2021. "The Political Situation in Pakistan." November 20, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/the-political-situation-in-pakistan/.

This paper, “The Political Situation in Pakistan”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: November 9, 2023 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

Pakistan and its Politics Essay

Introduction, reason for move towards islamic state, impact of islamic state on democracy, works cited.

Pakistan was established as a state in 1947 after a separation from the Indian British Empire. From its beginning, the country has had a turbulent life with political instability and ethnic disputes characterizing its existence. While Pakistan was established as a secular state with a Muslim majority, the country has exhibited over the decades showed signs of evolving into an Islamic State. Such an outcome would have dire consequences for democratization.

The prevailing economic conditions have increased the popularity of Islamic movements all over the country. Farhat notes that most Pakistanis blame bad government policies for the high unemployment, inflation, and lack of access to education and healthcare in the country (121).

Islamists express skepticism over the ability of the secular leadership, which is blamed for Pakistan’s problems. Saudi influence has also been a contributing factor to the evolution of Pakistan into an Islamic state.

Due to the lack of financial opportunities in Pakistan, Saudi Arabia has been a major destination for Pakistanis working abroad since the 1970s. When the Pakistani workers return home from this Islamic state, they are influenced by the religious teachings of Saudi clerics (Farhat 122).

Western dominance has also accelerated the move towards Islamic reform in Pakistan. After the events of 9/11, the cooperation between the Pakistani government and the United States has increased with Pakistan becoming a key strategic ally. Radical Islamists see this as a corruption of Islam by the West.

Farhat points out that this challenge of the West has become the single most important factor promoting the renewal of Islamic movements in Pakistan today (129). Western dominance has fueled nationalistic sentiments and many people are in support of an Islamic renewal.

Evolution to an Islamic State will hurt democracy in Pakistan. Politicians have been known to employ religious criteria to justify their actions in Islamic states. This will be to the disadvantage of Pakistanis of other religions and Islamic sub-sects.

Ishtiaq observes that While Pakistan has a Muslim majority with 96% of Pakistanis being Muslims, the Muslim community is not monolithic and it contains different sub-sects (195). An Islamic state would therefore threaten democracy since it would give rise to sectarianism in Pakistani territories.

By adopting an Islamic character, Pakistan has enacted many laws that are discriminatory to non-Muslims. For example, the third constitution of 1973 required the president and the prime minister to be Muslims (Ishtiaq 198). Such laws are not in line with the democratic principles that give each person equal opportunity in the state.

The Islamic state will ensure that only practicing Muslims can take up key leadership positions in the country. An Islamic state will also hurt democracy since the ruling elite may resort to Islamic rhetoric to undermine the opposition. Farhat demonstrates that Islamic symbolism may be used to legitimize leadership that would otherwise be voted out in a true democracy (127).

Pakistan is a country with a rich Islamic history spanning centuries and the country was created with these religious and cultural bearings in mind. However, Pakistan was created as a Muslim state and not an Islamic State. The trends articulated in this paper are moving Pakistan towards becoming an Islamic State. If this happens, the democratic values currently enjoyed by the country will suffer as Islamic laws becomes adapted all over the land.

Farhat, Haq. “A state for the Muslims or an Islamic state?” Religion and Politics in South Asia . Ed. Ali Riaz. NY. Routledge, 2010. 119-145. Print.

Ishtiaq, Ahmed. “The Pakistan Islamic State Project: A secular Critique.” Religion and Politics in South Asia . Ed. Ali Riaz. NY. Routledge, 2010. 185-211. Print.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, October 31). Pakistan and its Politics. https://ivypanda.com/essays/pakistan-and-its-politics/

"Pakistan and its Politics." IvyPanda , 31 Oct. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/pakistan-and-its-politics/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Pakistan and its Politics'. 31 October.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Pakistan and its Politics." October 31, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/pakistan-and-its-politics/.

1. IvyPanda . "Pakistan and its Politics." October 31, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/pakistan-and-its-politics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Pakistan and its Politics." October 31, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/pakistan-and-its-politics/.

- Pakistan Versus The USA

- Phone Industry: Entrepreneur in Foreign Markets

- The Kashmir Crisis: An Ethno-Religious Perspective

- Pakistani Nuclear Program Development and Factors

- Pakistani and American Intelligence Agencies

- Pakistan’s Double Game in the War on Terror

- Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt

- Pakistani Students’ Education in "I am Malala" by Yousafzai

- Tunisia's Gender Equality

- How U.S. Relations Have Impacted and Affected Pakistani-Indian Relations Post Cold War

- Political Liberalism Pros and Cons

- Modernity and Islamism in Morocco

- Islam: Religious Tradition and Politics

- Islam and Politics: Separation of Religion and State

- Regime Trajectories: Structuralist and Process-Oriented Views

United States Institute of Peace

Home ▶ Publications

The Current Situation in Pakistan

A USIP Fact Sheet

Monday, January 23, 2023

Publication Type: Fact Sheet

Pakistan continues to face multiple sources of internal and external conflict. Extremism and intolerance of diversity and dissent have grown, fuelled by a narrow vision of Pakistan’s national identity, and are threatening the country’s prospects for social cohesion and stability.

The inability of state institutions to reliably provide peaceful ways to resolve grievances has encouraged groups to seek violence as an alternative. The country saw peaceful political transitions after the 2013 and 2018 elections. However, as the country prepares for anticipated elections in 2023, it continues to face a fragile economy along with deepening domestic polarization. Meanwhile, devastating flooding across Pakistan in 2022 has caused billions in damage, strained the country’s agriculture and health sectors, and also laid bare Pakistan’s vulnerability to climate disasters and troubling weaknesses in governance and economic stability.

Regionally, Pakistan faces a resurgence of extremist groups along its border with Afghanistan, which has raised tensions with Taliban-led Afghanistan. Despite a declared ceasefire on the Line of Control in Kashmir in 2021, relations with India remain stagnant and vulnerable to crises that pose a threat to regional and international security. The presence and influence of China, as a great power and close ally of Pakistan, has both the potential to ameliorate and exacerbate various internal and external conflicts in the region.

USIP’S Work

The U.S. Institute of Peace has conducted research and analysis and promoted dialogue in Pakistan since the 1990s, with a presence in the country since 2013. The Institute works to help reverse Pakistan’s growing intolerance of diversity and to increase social cohesion. USIP supports local organizations that develop innovative ways to build peace and promote narratives of inclusion using media, arts, technology, dialogues and education.

USIP works with state institutions in their efforts to be more responsive to citizens’ needs, which can reduce the use of violence to resolve grievances. The Institute supports work to improve police-community relations, promote greater access to justice and strengthen inclusive democratic institutions and governance. USIP also conducts and supports research in Pakistan to better understand drivers of peace and conflict and informs international policies and programs that promote peace and tolerance within Pakistan, between Pakistan and its neighbors, and between Pakistan and the United States.

USIP’s Work in Pakistan Includes:

Improving police-community relations for effective law enforcement

The Pakistani police have struggled with a poor relationship with the public, characterized by mistrust and mistreatment, which has hindered effective policing. USIP has partnered with national and provincial police departments to aid in building police-community relationships and strengthening policing in Pakistan through training, capacity building and social media engagement.

Building sustainable mechanisms for dialogue, critical thinking and peace education.

Nearly two-thirds of Pakistan’s population is under the age of 30. Youth with access to higher education carry disproportionate influence in society. However, Pakistan’s siloed education system does not allow interactions across diverse groups or campuses, leading to intolerance, and in some cases, radicalization. To tackle growing intolerance of diversity on university campuses, USIP has partnered with civil society and state institutions to support programs that establish sustainable mechanisms for dialogue, critical thinking and peace education.

Helping Pakistanis rebuild traditions of tolerance to counter extremists’ demands for violence

USIP supports local cultural leaders, civil society organizations, artists and others in reviving local traditions and discourses that encourage acceptance of diversity, promote dialogue and address social change. USIP also supports media production — including theater, documentaries and collections of short stories — which offer counter narratives to extremism and religious fundamentalism.

Support for acceptance and inclusion of religious minorities

Relations between religious communities in Pakistan have deteriorated, with some instances of intercommunal violence or other forms of exclusion. USIP supports the efforts of local peacebuilders, including religious scholars and leaders, to promote interfaith harmony, peaceful coexistence and equitable inclusion of minorities (gender, ethnic and religious) in all spheres of public life.

Supporting inclusive and democratic institutions

To help democratic institutions be more responsive to citizens, USIP supports technical assistance to state institutions and efforts to empower local governments, along with helping relevant civil society actors advocate for greater inclusion of marginalized groups. Gender has been a major theme of this effort and across USIP’s programming in Pakistan. These programs empower women in peacebuilding and democratic processes through research, advocacy and capacity building.

Related Publications

As Fragile Kashmir Cease-Fire Turns Three, Here’s How to Keep it Alive

Wednesday, February 21, 2024

By: Christopher Clary

At midnight on the night of February 24-25, 2021, India and Pakistan reinstated a cease-fire that covered their security forces operating “along the Line of Control (LOC) and all other sectors” in Kashmir, the disputed territory that has been at the center of the India-Pakistan conflict since 1947. While the third anniversary of that agreement is a notable landmark in the history of India-Pakistan cease-fires, the 2021 cease-fire is fragile and needs bolstering to be maintained.

Type: Analysis

Global Policy

Understanding Pakistan’s Election Results

Tuesday, February 13, 2024

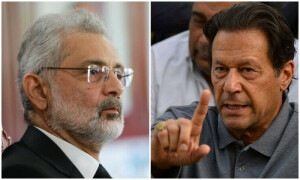

By: Asfandyar Mir, Ph.D. ; Tamanna Salikuddin

Days after Pakistan’s February 8 general election, the Election Commission of Pakistan released the official results confirming a major political upset. Contrary to what most political pundits and observers had predicted, independents aligned with former Prime Minister Imran Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) won the most seats at the national level, followed by former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N), the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) and the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM). No party won an absolute majority needed to form a government on its own. The resultant uncertainty means the United States may have to contend with a government that is more focused on navigating internal politics and less so on addressing strategic challenges.

Global Elections & Conflict ; Global Policy

Tamanna Salikuddin on Pakistan’s Elections

Monday, February 12, 2024

By: Tamanna Salikuddin

Surprisingly, candidates aligned with former Prime Minister Imran Khan won the most seats in Pakistan’s elections. But while voters “have shown their faith in democracy,” the lack of a strong mandate for any specific leader or institution “doesn’t necessarily bode well for [Pakistan’s] stability,” says USIP’s Tamanna Salikuddin.

Type: Podcast

The 2021 India-Pakistan Ceasefire: Origins, Prospects, and Lessons Learned

Tuesday, February 6, 2024

The February 2021 ceasefire between India and Pakistan along the Line of Control in Kashmir has—despite occasional violations—turned into one of the longest-lasting in the countries’ 75-year shared history. Yet, as Christopher Clary writes, the ceasefire remains vulnerable to shocks from terrorist attacks, changes in leadership, and shifting regional relations. With the ceasefire approaching its third anniversary, Clary’s report examines the factors that have allowed it to succeed, signs that it may be fraying, and steps that can be taken to sustain it.

Type: Special Report

Peace Processes

- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- 2024 election

- Solar eclipse

- Supreme Court

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

- World Politics

Pakistan’s political crisis, briefly explained

An end to Pakistan’s constitutional crisis. But a political crisis endures.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: Pakistan’s political crisis, briefly explained

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/70729775/GettyImages_1239685272.0.jpg)

Editor’s note, April 10: Sunday, Imran Khan received a vote of no confidence from the Pakistani parliament, losing his position as prime minister. A vote on a new prime minister is expected as soon as Monday.

One of Pakistan’s twin crises was resolved this week. The other one, not so much.

On Thursday, the country’s supreme court delivered a historic ruling that resolved a constitutional crisis that took shape last week. The court rebuked Prime Minister Imran Khan, a self-fashioned populist leader and former cricket star who is more celebrity than statesman. Khan, the court ruled, had acted unconstitutionally when he dissolved Pakistan’s Parliament last week in order to avoid losing power through a no-confidence vote.

It was a surprising and reassuring decision, experts in the country’s politics said, given the supreme court’s checkered record as a sometime political ally of Khan. On Thursday, the court sided with the rule of law.

But the underlying political crisis that led to the court’s landmark order endures.

Khan outlandishly blamed the opposition parties’ efforts to oust him on a US-driven foreign conspiracy. Now, the Parliament has been restored and will continue with its no-confidence vote against Khan’s premiership Saturday, likely leading to his ouster and extraordinary elections later this year. Khan, for his part, said that he would “ fight ” back.

The broader political crisis, however, can be traced to the 2018 election that brought Khan to power. Traditionally, the military is the most significant institution in Pakistan, and it has often intervened to overthrow elected leaders that got in its way. Khan’s rise is inextricable from military influence over politics , and the incumbent prime minister accused the military of a soft coup for manipulating the election in Khan’s favor.

It was a “very controversial election,” says Asfandyar Mir, a researcher at the United States Institute of Peace. “There was a major question over the legitimacy of that electoral exercise and the government that Khan formed could just never escape the shadow of the controversy surrounding that election,” Mir explained.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23377093/GettyImages_1005001746.jpg)

More recently, the relationship between the military and Khan has worsened, and that gave the political opposition an opening to act against him. Though it’s not known what role the military played in the supreme court’s ruling, experts note that the harshness of the court’s order suggests the military’s buy-in. “This is part of a larger history of instability in Pakistan in which prime ministers are ousted from power, because they lose the support of Pakistan’s military,” Madiha Afzal, foreign policy fellow at the Brookings Institution, told Vox.

But “even if the court was influenced by the military, it took the right decision,” she says.

Khan’s position weakened domestically

The political and economic situation set the stage for a challenge to Khan.

After running on a campaign that promised less corruption and more economic opportunity for the poor, Khan has failed to deliver. Inflation is climbing , unemployment is soaring , and a billion-dollar program from the International Monetary Fund has not helped stabilize matters. An international investigation into offshore money from last year, known as the Pandora Papers , showed that Khan’s inner circle had moved money abroad to avoid taxes, in contradiction with Khan’s populist rhetoric.

Khan presided over an anti-corruption witch hunt targeting opposition parties. Indeed, the opposition parties, many of them composed of dynastic leadership and families with old money, are corrupt , and their attempt to oust Khan can be seen as a move to evade further scrutiny, Mir said.

Still, that anti-corruption effort brought the government bureaucracy to a halt. And it’s part of Khan’s broader strongman-style approach to governing that has been ineffective .

Since his start in politics, Khan has depended on the courts. Yasser Kureshi, a researcher in constitutional law at the University of Oxford, says Khan has built his political standing on backing the judiciary. “Imran Khan’s political platform has been built around an anti-corruption populism, where he charges the political class for being corrupt, and in the last 15 years the supreme court has been on a spree of jurisprudence targeting the political corruption of Pakistan's traditional parties,” he explains. “Khan has been the biggest supporter of this jurisprudence as it has validated and legitimized his politics.”

Now, the court appears to have turned against him at a time when the military has also lost faith in Khan. “With Imran Khan, I think that the problem for him is that right now, he has no institutional solutions that he can really turn to,” says Kureshi.

Khan’s relationship with the US has also cooled

Pakistan is a nuclear-armed country with a population of 220 million; it has built the sixth-largest military in the world, and has clout as a leader in the Islamic world. A longtime participant in the US war on terrorism, Pakistan has also been a conflicted partner, criticized for at times abetting the Taliban .

Khan was elected in 2018, and Mir says that, two years in, the military’s relationship to him began to cool. Khan feuded with the army chief over foreign policy issues, and the military saw Khan’s poor governance as a liability. Last year, Khan’s delays in signing off on a new intelligence chief prompted speculation of more divides between the two.

President Joe Biden did not phone Khan in his initial days in office, though he did call the leader of India , Pakistan’s chief rival. “The Biden administration’s cold shoulder to Imran Khan rubbed him the wrong way,” said Afzal. “Pakistan has just fallen off a little bit of the radar in terms of high-level engagement.”

Khan’s public messaging as a strongman has partially been responsible for agitating the relationship with the US — and by extension, his relationship with the Pakistani military, which wants to be closer to the US.

Most recently, that chill was expressed by Khan’s decision to stay neutral in Russia’s war on Ukraine; Khan visited Moscow just in advance of Russia’s invasion.

And, now, he’s turned to accusations of conspiracy: that the opposition’s stand against him is manufactured by the US. The origins of Khan’s incendiary claims appear to be a diplomatic cable that Pakistan’s ambassador to Washington sent home last month after a meeting with senior State Department official Donald Lu. Whatever criticisms Lu may have conveyed about Pakistan’s foreign policy, Khan’s interpretation of the memo has clearly been blown out of proportion. “When it comes to those allegations, there is no truth to them,” State Department spokesperson Ned Price said last week.

It’s an open question whether his argument will resonate among a Pakistani populace who is suspicious of the United States. One group it’s likely not resonating with: Pakistan’s powerful military.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23377272/GettyImages_1239432654.jpg)

Khan is “critical of the United States to a point that makes the military uncomfortable,” said Shamila Chaudhary, an expert at the New America think tank. “The way he’s talking about the United States is preventing the US relationship with Pakistan from being repaired, and it needs to be repaired.”

Meanwhile, the Biden administration’s focus in Asia has been on great-power competition with China and two national security crises (the Afghanistan withdrawal and Russia’s Ukraine invasion). The sloppy withdrawal of US forces from Afghanistan furthered the disconnect between Washington and Islamabad, according to Chaudhary, and further upset Pakistan’s government.

Robin Raphel, a former ambassador who served as a senior South Asia official in the State Department from 1993 to 1997, described Biden’s outlook to Pakistan as a “non-approach approach.”

“I’m a diplomat, and, I believe you get more with honey than vinegar,” she said. “It would have been more than worth it for the president to take five minutes to call Imran Khan.”

The US did send its top State Department official for human rights, Uzra Zeya, to the Organization of Islamic Countries summit in Pakistan last month. Zeya also met with the country’s foreign minister and senior officials, as the two countries celebrated the 75th anniversary of diplomatic relations.

But there hasn’t been more than that in terms of a positive message for the US-Pakistan relationship in light of the recent political and constitutional crises in the country. Price’s recent comments on the situation were brief: “We support Pakistan’s constitutional process and the rule of law.”

What happens next

Once the Parliament completes its no-confidence vote, which may happen as soon as today, it will dissolve the government. The country’s electoral commission will then oversee a caretaker government that will likely be headed by the leader of the opposition, Shehbaz Sharif . (Sharif is the brother of Nawaz Sharif , a former prime minister himself, who is currently living in exile in the UK as he faces accusations of corruption.) And, in that forthcoming vote, Khan will most probably lose .

But even the specifics of those elections are contentious. Khan had asked the electoral commission to set a date within the next 90 days; opposition politicians told NPR that reforms are needed before the next vote, otherwise they say the military will “rig” the next elections.

Long-term, things are even less clear. Among civil society leaders in Pakistan, there is agreement that the supreme court’s ruling is good for constitutionalism. But it may also be a vehicle for further expansion of the judiciary’s ability to intervene in politics.

Kureshi, an expert on the courts of Pakistan and how they have increasingly become the arbiter of politics in the country, says the bigger takeaways won’t be fully understood until the court releases the full text of its ruling in the next month or so. That detailed order may set other legal precedents and even cast the opposition in a bad light.

After the immediate euphoria of keeping Khan’s audacious unconstitutional maneuver in check, that judgment may say a lot about how the court sees itself, especially its supervisory role over the parliament and prime minister.

“The elected institutions are deeply constrained by the tutelage of overly empowered unelected institutions, whether it is the military, historically, or the judiciary more recently,” said Kureshi. “Judgments like this give them an opportunity to further affirm and expand that role.”

Will you support Vox today?

We believe that everyone deserves to understand the world that they live in. That kind of knowledge helps create better citizens, neighbors, friends, parents, and stewards of this planet. Producing deeply researched, explanatory journalism takes resources. You can support this mission by making a financial gift to Vox today. Will you join us?

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Next Up In Politics

Sign up for the newsletter today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

Thanks for signing up!

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

What the Supreme Court case on tent encampments could mean for homeless people

Will AI mean the end of liberal democracy?

Israel and Iran’s conflict enters a new, dangerous phase

Trump’s jury doesn’t have to like him to be fair to him

What’s behind the latest right-wing revolt against Mike Johnson

Taylor Swift seems sick of being everyone’s best friend

- Arts & Culture

Get Involved

Autumn 2023

Annual Gala Dinner

Internships

Pakistan’s political crisis and the imperatives of economic reform

Pakistan continues to reel from uncertainty as its political transition — ill-timed during a period of domestic and global economic tumult — has yet to consolidate.

Political volatility during the new governing coalition’s first two months in power has led to policy paralysis. But this paralysis has begun to ease as the army has signaled support for the government and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) continues to press for austerity measures.

The IMF has made clear that it will only release the next $1 billion tranche from Pakistan’s $6 billion Extended Fund Facility if Islamabad raises fuel and electricity prices and takes aggressive measures to reduce the fiscal deficit. And the resumption of the IMF program is essential to unlocking assistance from other bilateral and multilateral partners and staving off a balance of payments crisis. As a result, the coalition led by the Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz) (PML-N) has finally started raising energy prices .

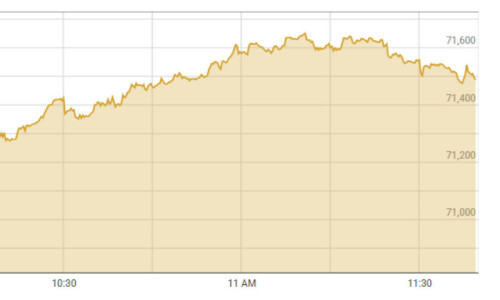

These measures will ease Pakistan’s twin deficit challenge, involving both fiscal and current account deficits, but they will also take a heavy toll on the average Pakistani. Inflation, which hit 13.8% in May , could rise to around 20% and remain in the double digits into next year. This will be a painful summer for Pakistanis as they're hit with a one-two punch of rising energy prices and electricity supply cuts .

Understandably, the PML-N would like other power brokers, including the army, to share the political burden of economic reform . Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif has called for the adoption of a Charter of the Economy — a national consensus on economic reform.

The idea is sound, but politically infeasible right now. What is more important is for Pakistan’s current federal and provincial governments to go beyond firefighting and push forward essential reforms — including in agriculture, energy, and local governance — that are key to ensuring the country’s political and economic stability and long-term growth prospects. Indeed, it is in their political interest to do so.

Pakistan’s angry middle class

Pakistan’s power elite must recognize that this is an exceptional moment in the country’s history — an inflection point both politically and economically.

Former Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan, once backed by the powerful army and Inter-Services Intelligence agency, is taking on the new government and the army leadership. Khan is not just backed by what one might call the “anti-elite elite,” but also by much of the middle class.

Sixty-two percent of those with a full secondary education or higher said they were “angry” about Khan’s ouster in an April survey conducted by Gallup Pakistan. Given widespread anti-U.S. sentiment, Khan’s claims of being deposed by an American "regime change” campaign have resonated with this demographic. But it’s not the only reason why they support him. Khan is also tapping into their resentment of the status quo.

In recent years, Pakistan’s middle class has been hit hard by unemployment and inflation. According to the Pakistan Human Development Report 2020 from the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), the real growth rate of per capita income for Pakistan’s middle class from the 2013-14 and 2018-19 fiscal years trailed that of the rest of the population (1.2% versus 1.8%). The unemployment rate of those with a college degree or higher surged from less than 5% in 2007-08 to over 16% in 2018-19. Pakistan has a seen an expansion of higher education, but there remains a mismatch between the skill sets and preferences of college graduates and the demands of employers. As the current government reduces blanket subsidies, replacing them with targeted cash transfers for the very poor, macroeconomic stabilization may largely come at the middle class’s expense. And that could have political as well as geopolitical ramifications.

Khan has fused the issues of inflation and national sovereignty by alleging that the Sharif government is afraid of incurring Washington’s wrath by following through on an agreement he claims to have made with Moscow for importing discounted Russian oil. He notes that New Delhi has ramped up imports of Russian oil and, as a result, has been able to avoid fuel price hikes.

A focused reform agenda

The big picture is this: Pakistan’s economy is working, but only for its elite. Sustained, rapid, and equitable economic growth has remained elusive due to policy distortions that serve its civilian and military elite.

The aforementioned UNDP report , produced by a team of Pakistani researchers led by Dr. Hafiz Pasha, offers an exceptional deconstruction of Pakistan’s political economy. It assesses that in the 2017-18 fiscal year alone, Pakistan’s corporate, feudal, and military elite received the equivalent of $13 billion in current dollar terms in “benefits and privileges” — roughly 7% of the country's GDP.

Reform is a long-term process. But Pakistan must make use of this “shock” period to redistribute allocations toward social protection and incentivize greater productivity. Delay is not an option. In the coming years, Pakistan’s challenges will only deepen due to climate change and rapid population growth. Pakistan is already one of the world’s 10 most populous countries and it will remain among those ranks as its population surges over the coming decades.

Pakistan needs a path toward sustained, rapid, and equitable economic growth that incorporates its fast-growing population into the labor market. But Pakistan is a net energy importer with a narrow export base. Periods of economic expansion have been consumption-driven and import-dependent. As a result, Pakistan’s economy overheats once growth passes the 5-6% range . It is vital that the current government devote its energy and reallocate resources toward facilitating export growth, improving agricultural productivity, and addressing the domestic fuel production deficit.

Pakistan’s agricultural sector has grown at an average rate of less than 2% since the 2014-15 fiscal year. Declining agricultural productivity, a rapidly growing population, increasing water stress, and the worsening effects of climate change are all exacerbating an already-serious food security challenge. The agricultural industry also contributes to the massive electric power industry arrears. Pakistan provides hundreds of millions of dollars in annual electric power subsidies for agricultural tube wells. And edible oils are among Pakistan’s top imports .

Policy experiments in Pakistan in recent years have identified solutions to these challenges. For example, conditioning the provision of low-interest loans for solar tube well installation on the use of high-efficiency irrigation systems or allowing net-metering can promote water conservation, lower input costs, and help curtail power sector debt.

Pakistan’s federal and provincial governments should also incentivize innovation in the private sector seed development industry and the local production of edible oils.

With domestic gas and oil reserves in decline, Pakistan’s vulnerability to surges in global fuel prices will grow. It needs to ramp up domestic energy exploration, promote renewables, and assess the feasibility of green hydrogen and ammonia production, especially in southern Balochistan.

Finally, Pakistan must strengthen the “last mile” of governance. Pakistani politicians often hail China’s model of governance, but few recognize the role of decentralization of power and empowerment of local governments in China’s growth story.

To their credit, Pakistan’s politicians banded together to devolve power to the provinces under the 18th Amendment. Yet most have been averse to devolving power down to elected local bodies, with some provincial governments repeatedly delaying local elections. That has left large metropolises like Karachi orphaned when it comes to local governance and stunts their ability to grow and develop independent sources of revenue, including through the issuance of bonds.

Political stability in Pakistan cannot be ensured simply through intra-elite deals made in Islamabad. It also requires improving the last mile of governance and the responsiveness of the state to the needs of the public.

Arif Rafiq is the president of Vizier Consulting LLC, a political risk advisory company focused on the Middle East and South Asia, and a non-resident scholar at the Middle East Institute (MEI).

Photo by AAMIR QURESHI/AFP via Getty Images

The Middle East Institute (MEI) is an independent, non-partisan, non-for-profit, educational organization. It does not engage in advocacy and its scholars’ opinions are their own. MEI welcomes financial donations, but retains sole editorial control over its work and its publications reflect only the authors’ views. For a listing of MEI donors, please click her e .

Publications

- Analysis & Opinions

- News & Announcements

- Newsletters

- Policy Briefs & Testimonies

- Presentations & Speeches

- Reports & Papers

- Quarterly Journal: International Security

- Artificial Intelligence

- Conflict & Conflict Resolution

- Coronavirus

- Economics & Global Affairs

- Environment & Climate Change

- International Relations

- International Security & Defense

- Nuclear Issues

- Science & Technology

- Student Publications

- War in Ukraine

- Asia & the Pacific

- Middle East & North Africa

- North America

- South America

- Infographics & Charts

US-Russian Contention in Cyberspace

The overarching question imparting urgency to this exploration is: Can U.S.-Russian contention in cyberspace cause the two nuclear superpowers to stumble into war? In considering this question we were constantly reminded of recent comments by a prominent U.S. arms control expert: At least as dangerous as the risk of an actual cyberattack, he observed, is cyber operations’ “blurring of the line between peace and war.” Or, as Nye wrote, “in the cyber realm, the difference between a weapon and a non-weapon may come down to a single line of code, or simply the intent of a computer program’s user.”

The Geopolitics of Renewable Hydrogen

Renewables are widely perceived as an opportunity to shatter the hegemony of fossil fuel-rich states and democratize the energy landscape. Virtually all countries have access to some renewable energy resources (especially solar and wind power) and could thus substitute foreign supply with local resources. Our research shows, however, that the role countries are likely to assume in decarbonized energy systems will be based not only on their resource endowment but also on their policy choices.

What Comes After the Forever Wars

As the United States emerges from the era of so-called forever wars, it should abandon the regime change business for good. Then, Washington must understand why it failed, writes Stephen Walt.

Telling Black Stories: What We All Can Do

Full event video and after-event thoughts from the panelists.

- Defense, Emerging Technology, and Strategy

- Diplomacy and International Politics

- Environment and Natural Resources

- International Security

- Science, Technology, and Public Policy

- Africa Futures Project

- Applied History Project

- Arctic Initiative

- Asia-Pacific Initiative

- Cyber Project

- Defending Digital Democracy

- Defense Project

- Economic Diplomacy Initiative

- Future of Diplomacy Project

- Geopolitics of Energy Project

- Harvard Project on Climate Agreements

- Homeland Security Project

- Intelligence Project

- Korea Project

- Managing the Atom

- Middle East Initiative

- Project on Europe and the Transatlantic Relationship

- Security and Global Health

- Technology and Public Purpose

- US-Russia Initiative to Prevent Nuclear Terrorism

Special Initiatives

- American Secretaries of State

- An Economic View of the Environment

- Cuban Missile Crisis

- Russia Matters

- Thucydides's Trap

Policy Brief

- Xenia Dormandy

Since March 2007, tensions in Pakistan have been rising: the political instability surrounding both the presidential and parliamentary elections is commingling with the increase in militant activity within Pakistan proper, which led to around 60 suicide attacks in Pakistan in 2007. Following Benazir Bhutto's assassination on December 27, the extremists have upped the ante, perhaps hoping to disrupt the February 18 elections. Is Pakistan becoming the world's "most dangerous nation"?

Since gaining independence in 1947, Pakistan has veered back and forth between democratically-elected and authoritarian military leaders, coupled with an unstable relationship with neighboring India and Bangladesh. From 1988 to 1999, following Zia ul Haq's death, democracy - albeit an unstable one - reigned; power alternated between Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif, with neither completing a full term as Prime Minister. Finally, in October 1999, a Chief of Army Staff, Pervez Musharraf, led a coup against Sharif and took over as President.

CURRENT SITUATION

Over the past eight years, President Musharraf has done many good things for Pakistan, most notably building a relatively stable and fast-growing economy (GDP growth in 2006 was 6.5%). However, he has made no effort to create independent institutions, improve the provision of education and other social services, or establish local governance systems and networks. The situation has worsened significantly over the past year: the judiciary is now thoroughly politicized, the media is restricted by a "code of conduct", and the interim government is biased. Meanwhile, Musharraf's approval ratings have almost halved from 51% in late 2006 to 28% in early January 2008. Musharraf continues to prioritize his own political survival; however, he is no longer trusted by either the Pakistani people or the international community, leaving him in an untenable situation.

The recent deterioration of Pakistan's political situation has been driven by the following events:

- In March 2007, Musharraf suspended Chief Justice Iftikhar Mohammed Chaudhry for misconduct, triggering a public outcry. Four months later, Chaudhry was reinstated in a ruling by his own Supreme Court; however, the incident sparked an enormous grassroots movement for change.

- In July, security forces raided Islamabad's Red Mosque, a center for radical and militant thought, killing cleric Abdul Rashid Ghazi and an undetermined number of followers (estimates range from around 100 to over 1000). Consequently, Musharraf lost the support of the mullahs, who wield enormous social and moral power in Pakistan.

- On October 6, Musharraf was overwhelmingly reelected President while still acting as Chief of Army Staff. The majority of opposition delegates boycotted the election, and the Supreme Court began assessing the legitimacy of the results.

- On November 3, Musharraf declared a state of emergency and dismissed Chaudhry once again, staffing the caretaker government and judiciary with loyal supporters. As a result, his already-wavering public support plummeted.

- In late November, Musharraf removed his uniform, appointing General Kiyani as the new Chief of Army Staff, and a day later was inaugurated in a new term as president.

- On December 27, nearly two weeks after Musharraf ended emergency rule, Benazir Bhutto was assassinated at a campaign rally. Her 19-year-old son, Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, and her husband, Asif Zardari, were appointed in her stead. In light of the violence that ensued, the parliamentary elections were pushed back to February 18.

- In January 2008, there were at least four major suicide attacks within Pakistan proper; more have followed. Violence and military activity in the tribal areas has risen significantly.

The lack of predictability and transparency through both the presidential and parliamentary elections has amplified the confusion, the instability, and Musharraf's loss of credibility. Recently, these political fights have been compounded by a concurrent rise in militancy, which has fed into the ongoing sectarian violence throughout Pakistan and the fight for more autonomy in Baluchistan. Security in Pakistan is fading; this fact was made clear in January when refugees flooded into Afghanistan from Pakistan, the former being perceived as providing a safer environment.

Short Term: Tensions will remain on the boil at least until the parliamentary elections scheduled for February 18 take place. The militant attacks are not diminishing, and the electoral race continues, complicated by the additional confusion surrounding the new and multi-headed leadership of the PPP. Three scenarios for Pakistan's immediate future are feasible:

- Given the continued violence and particularly if it seems likely that his party will lose badly in the parliamentary elections, it is still possible that President Musharraf could cancel the elections altogether and call a state of emergency. However, it is unlikely that the public would allow Musharraf to maintain this situation for long; ultimately, he would be removed from office, either by the military or by the people.

- The elections could be won by the PPP, either by earning a majority or building a coalition with Sharif's PML-N or Musharraf's PML-Q. If the former coalition is created, then Musharraf will likely be ousted from power and prosecuted for his recent actions. Polls conducted in November 2007 found that if a legitimate election were held, the PPP would win by a slight margin. In early February 2008, polls predicted that the PPP had gained additional sympathetic support after Bhutto's assassination, further increasing their vote bloc.

- Given polling data, it is clear that if Musharraf's party, the PML-Q, wins the parliamentary elections, it will be an illegitimate win. Under these circumstances, there will be a massive popular backlash and he will be ousted.

Regardless of who wins, all of the leading candidates will likely pursue similar policies to Musharraf, with differing levels of competence. Stability will be maintained by the military, particularly given the continuity that General Kiyani brings to the leadership. Any of the candidates for Prime Minister will face the same challenges; variance in their performance will be in the margins, with Sharif likely engaging more with the mullahs and the PPP following a more socialist economic policy.

Long Term: Perhaps the more important factor than the winner is the process followed, and whether the people feel their voices are being heard and their participation encouraged. Pakistan is at a crossroads. It could either follow a slow descent into further authoritarianism and increased militancy and extremism that will be clearly detrimental to Pakistan today and could in 5 to 7 years also become a danger to the rest of the world. Alternatively, it could pursue a slow ascent towards a more stable democratic system with established independent institutions, growing economy, and a nation representative of a moderate Muslim democracy. The people's continued participation will raise the probability of the latter path being taken and so, above all else, it is important that this is encouraged. However, either path is a gradual one, and as such requires patience and a long-term perspective from both Pakistanis and the international community.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The United States needs to pursue the following policy priorities and guidelines:

- Pursue a long-term strategy rather than a short-term one.

- Build trust between the U.S. and Pakistan and its people: Given perceived past fickleness and hypocrisy over promoting democratic sentiments but supporting authoritarian leaders (specifically Musharraf), the Pakistani people do not trust the U.S. Without this, the will to pursue joint interests vigorously will be limited.

- Support democratic processes and stability first and foremost: This means also supporting Pakistan's current focus on the Pakistani Taliban rather than on al-Qaida as being the greater direct threat to Pakistan in the immediate term.

- Prevent Pakistan from becoming the next epicenter of terrorism: This entails continuing to support Pakistan's military efforts at destroying the terrorist threat, as well as engaging hearts and minds, bringing the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) into Pakistan proper.

Given these priorities, the United States should alter current policy by:

- Explicitly stating its support for free and fair elections and, more pertinently, support for the legitimate winner of these elections (discarding the current U.S. ambiguity of supporting both credible elections and President Musharraf in particular);

- Reallocating a greater proportion of current U.S. military assistance to training Pakistan's military in counter-insurgency in Pakistan in the short-term and in the United States in the long-term.

- Transferring around 15% of current military assistance to social and economic assistance specifically to democracy building efforts, supporting independent institutions and grass-roots political organizing.

- Monitoring the current U.S. spending to the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) and increase as capacity allows.

- Policy Brief: Pakistan Political Stability

- Former Senior Associate, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs

- Nuclear proliferation

- Terrorism & Counterterrorism

- Homeland security

- U.S. foreign policy

- India nuclear program

- Pakistan nuclear program

- Afghanistan war

- Military strategy

- Security Strategy

- Bio/Profile

- More by this author

Recommended

In the spotlight, most viewed.

Journal Article - International Security

A “Nuclear Umbrella” for Ukraine? Precedents and Possibilities for Postwar European Security

- Matthew Evangelista

From the Frontlines to the Future: Assessing Emerging Technology in Russia's Invasion Strategy and NATO's Next Moves

- Grace Jones

- Armughan Syed

- Sydney Hansen

Action on AI: Unpacking the Executive Order’s Security Implications and the Road Ahead

- Diletta Milana

The Short March to China’s Hydrogen Bomb

‘New Cold Wars’

- David Sanger

- Meghan O'Sullivan

- Karen Donfried

- Graham Allison

America Fueled the Fire in the Middle East

- Stephen M. Walt

Paper - Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School

Attacking Artificial Intelligence: AI’s Security Vulnerability and What Policymakers Can Do About It

- Marcus Comiter

Report - Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs

Challenging Biases and Assumptions in Analysis: Could Israel Have Averted Intelligence Failure?

- Beth Sanner

- Adam Siegel

Analysis & Opinions - TIME Magazine

The World's Newest Nation Is Unraveling

- Intrastate conflict

Belfer Center Email Updates

Belfer center of science and international affairs.

79 John F. Kennedy Street, Cambridge, MA 02138 (617) 495-1400

The Political Crisis in Pakistan

by Betty Wehtje | Dec 1, 2022 | Commentary , Democracy & Rule of Law

A political crisis has erupted in Pakistan, following months of unrest since the removal of former Prime Minister Imran Khan in April. Khan lost a no-confidence motion in the parliament and quickly called for his supporters to take to the streets. Since April, protests have occurred across the country with thousands of participants, as Khan accuses his removal of being a conspiracy orchestrated by the US and his political opposition. The political crisis intensified on November 3 , when Khan was shot at a protest in Wazirabad. Khan survived with a wound to the leg and has resumed his fight to return to power, calling for the continuation of his “Long March” toward the capital Islamabad. Since his removal, Muhammad Shehbaz Sharif, one of the leaders of the opposition, has become the temporary Prime Minister in wait for a new election. Yet no general election date has been set. While Khan and his supporters push for the immediate election, the opposition seeks to hold elections when due in August next year. Furthermore, a new army chief has recently been elected by current Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif, a crucial position since the army greatly influences Pakistan’s politics, adding to the tense political situation. Pakistan has reached a political stalemate that could turn into a harmful conflict. Pakistan is already heavily challenged by an economic crisis and the destruction after the catastrophic floodings, and further political unrest may only make matters even worse.

Imran Khan, the PTI, and his Political Opposition

Imran Khan was elected Prime Minister in July 2018 as the leader of the party Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI). The party was founded in 1996 with Khan as the chairman, and it emerged as a socio-political movement for “ justice ,” including fighting inequality and corruption. PTI grew in popularity over the upcoming decades and gained a majority in the 2018 election, which upset his political opponents. Imran Khan is seen as a charismatic populist who can gather huge public support for his party’s causes. In 2018 he vowed to fight corruption and improve governance, yet the results have fallen short. Pakistan has faced severe economic challenges which the government was unable to counter. Furthermore, Pakistan ranked 140 among 180 countries in the Transparency International Index. According to the index, corruption in 2021 was worse than in 2018. Still, Khan gathers great support among voters in Pakistan and a majority supports his call for direct elections, which might result in his return as Prime Minister. Khan has continued his “Long March” to Islamabad in demand of immediate elections, and supporters have openly stated that they are ready to defend themselves if the protests are met with violence. Khan has recently been accused of derailing democracy when commenting on the possibility of martial laws being imposed in Pakistan as the tense political situation continues.

Khan’s no-confidence vote was led by the opposition parties, the Pakistan Muslim League – Nawaz (PML-N) and the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP). Some key figures are the current Prime Minister Muhammad Shehbaz Sharif (leader of PML-N), Bilawal Bhutto-Zardari, and Asif Ali Zardari (heads of PPP). Khan has been harsh on the opposition, calling them “a gang of thieves,” threatening to expose their corruption and claim accountability, and the no-confidence vote was seen as an attempt to save themselves . However, the opposition pointed to Khan’s weak performance during his time as Prime Minister, with spiraling inflation and a massive devaluation of the rupee. Additionally, Khan has been criticized for appointing Usman Buzdar as Chief Minister in the Punjab province, who later was accused of widespread corruption . The opposition eventually won the no-confidence vote against Khan in April, as dozens of party members defected and some key allies voted against him. Yet, critical voices point to the army as the decisive actor who tipped the scales to the point that resulted in Khan’s removal, as Khan lost its support during his time as Prime Minister.

The Army: A Powerful and Decisive Player in Politics

Pakistan is a democracy, yet the country has a powerful and influential army, which significantly impacts politics. Pakistan has a long history of coups and military involvement in politics. There have been four military coups against elected governments since Pakistan’s independence in 1947, the latest being in 1999. The army has continued to have a significant impact on politics, especially concerning security and foreign policy. When Khan became Prime Minister in 2018, he announced his good relations with the army as the two were “on the same page,” and it seemed like Khan enjoyed close ties with the military during his first months in government. However, differences quickly appeared as his leadership did not fulfil its promises, and his opposition blamed the military for bringing him to power. Tensions rose further in late 2021 when Khan opposed the army’s decision to appoint a new chief of the intelligence services since he was a close ally of the incumbent Lt.Gen.Faiz Hameed. Khan eventually lost this fight against the army, and their cleavages became more visible. The war in Ukraine also became a source to widen the division between the army and Khan. With his anti-American policies and fear of India’s growing geopolitical influence, Khan has been getting closer to Russia, with a historic and criticized visit to Moscow on February 24 . He became the first Pakistani Prime Minister to visit Russia since 1999, which happened to take place as the invasion of Ukraine began. While Khan has resisted condemning the war in Ukraine and said Pakistan was to be neutral in the conflict, the military chief General Qamar Javed Bajwa has criticized Russia for its aggression on Ukraine, showing further political differences between Khan and the army.

Critics have long accused the military of orchestrating the removal of elected governments that do not follow the military’s institutional lines, which Khan and his supporters accused the military of having followed this modus operandi in April. Khan believes his former ally has betrayed him, and he has tried to halter the election of a new army chief which has been discussed this fall. The now outgoing army chief, General Qamar Javed Bajwa, admits that the military has “meddled in politics for decades,” but since February, it has been decided that the institution will no longer do so. Still, Khan has continued to criticize the army, and the newly elected army chief General Asim Munir, appointed by the current Prime minister Shehbaz Sharif, might become yet another backlash for Khan and his relationship with the military.

The Future is Uncertain

Pakistan is facing great challenges ahead, dealing with both an economic crisis and political instability. Politics are tumultuous, with an “all versus Khan” dynamic, in a changing environment with both a new Prime Minister and a new Chief of the army. The removal of Khan could be seen as part of the democratic process of parliamentary accountability, yet history seems to repeat itself in Pakistan. No democratically elected Prime Minister has ever completed a five-year term due to military coups, presidential ousting, and disqualifications from holding public office. The democratic process in Pakistan is vulnerable and has experienced considerable instability since the country’s independence. Corruption allegations, grievances, and political turmoil are common themes in Pakistani history, with the military as a recurrent stakeholder in politics.

It is impossible to predict the future of Pakistan, but it does not seem like Khan is to be excluded. His public support appears to have grown even larger since his removal in April, and his continued rallies across the country still attract the masses. The question is when the general elections will be held and if Khan will gain a majority again. Khan has shown his clear will for elections to be held this winter in hopes of keeping up the momentum. On Saturday, Khan said that the PTI would resign from the provincial assemblies to force the Shehbaz Sharif-led government to hold immediate elections. It is still to be seen what role the new Chief of the army will play in this political conundrum. Even though it is said that the army would no longer interfere with politics, Khan’s ousting has again put the army at the epicentre of the Pakistani political landscape. Tensions will likely increase continuously, and it is difficult to say for sure that there is a non-violent solution to the current political crisis unfolding in Pakistan, a country with a turbulent past and a vulnerable democracy.

Betty Wehtje is a research assistant intern at Beyond the Horizon ISSG. She is currently pursuing a Bachelor’s degree in Peace and Conflict Studies at Lund University in Sweden.

Pakistan: A Land of Dented Democracy and Increasing Polarization

NESA Center Alumni Publication Maida Farid (Consultant and an Independent Researcher) 22 June 2023

Pluralism is a key feature of democracy, that is often accompanied by tolerance. These ideas are intertwined, as a pluralistic society acknowledges and respects the diverse opinions, beliefs, and interests of its people. However, when pluralism lacks tolerance and regard for the rights of other groups, it can lead to political polarization. Political polarization occurs when there is a deep divide between different ideological or political groups, and there is little to no room for negotiation or finding common ground within the political system. In such a scenario, the lack of tolerance and respect for differing viewpoints can hinder the functioning of democracy. Polarized politics can be understood as a growing divide between people with different political views, leading to an environment of mistrust and animosity. It often involves zero-sum disagreements on various policies and rules within the political system. This phenomenon is not limited to any one country but is a global trend. Even the world’s oldest democracies, such as the United States, have faced challenges posed by polarized politics. Pakistan, with its turbulent history of civil-military relations, military interventions, ineffective civilian governments, and linguistic and ethnonational divides, is no exception to polarized politics and the challenges facing democracy. The socio-political fabric of Pakistan is greatly polarized on all levels, from the political elite to the masses, with a noticeable lack of consensus on fundamental democratic norms.

In Pakistan’s context, political polarization can be better understood as a top-down phenomenon rather than a bottom-up one. Throughout the country’s history, political elites have shaped narratives and influenced public sentiments. Thus, political polarization among the masses depends on what occurs in the corridors of power which penetrates the social fabric and polarizes the masses.

The struggle for power between state elites (such as the establishment and judiciary) and political parties can be seen as the primary level of political polarization in Pakistan. Due to this polarization and a lack of consensus, Pakistan has experienced prolonged influence of state institutions in political affairs, including direct military interventions, and judicial activism. The seventy-five years of Pakistan’s history have witnessed limited periods of political harmony and convergence between state institutions and political parties. Pakistan’s journey towards its first constitution took nine years due to a lack of agreement on the basic mode of governance between state institutions. The parliament, which is meant to represent the people, has often succumbed to external pressures. Parties in power tend to avoid crossing a certain point to maintain their position and not antagonize the institutions. Moreover, the long history of martial law has further divided political parties into pro-establishment and anti-establishment factions.

Pakistan’s political system was established on democratic principles, but it is questionable if the country has experienced true democracy. Instead, Pakistan has had various forms of democracy. Mohammed Wasim in his book Political Conflict in Pakistan refers to democracy in Pakistan as “Establishmentarian Democracy.” He describes different variants of democracy briefly mentioned below:

- Direct Military Rule: Pakistan’s political landscape has seen various forms of governance throughout its history. Direct military rule was imposed on the country for a total of 17 years, with General Ayub Khan leading from 1958 to 1962, General Yahya Khan from 1969 to 1971, General Zia-ul-Haq from 1977 to 1985, and General Pervez Musharraf from 1999 to 2002.

- Military-bureaucratic oligarchy: During the early years of Pakistan’s independence, a bureaucratic polity with an elected government existed for 11 years, from 1947 to 1958. However, this period was characterized by a military-bureaucratic oligarchy, where power was concentrated within the military and bureaucracy.

- Military government under a civilian president: Another form of governance witnessed in Pakistan was military government under a civilian president, following the King’s party model. This lasted for 16 years, with General Ayub Khan serving as the president from 1962 to 1969, General Zia-ul-Haq from 1985 to 1988, and General Pervez Musharraf from 2002 to 2008.

- Elected governments under civilian presidents: where the rule of the Trica model was followed, involving the establishment, judiciary, and parliament. This lasted for 11 years, with Benazir Bhutto serving as the president from 1988 – 1990, Nawaz Sharif from 1990 to 1993, Benazir Bhutto again from 1993 to 1996, followed by a caretaker government in 1996-1997, and Nawaz Sharif again from 1997 to 1999.

- Elected governments that constantly faced military tensions: For a period of 10 years, the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) held power from 2008 to 2013, followed by the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PMLN) from 2013 to 2018.

- Two years of an elected government and the establishment seemingly on the same page: This occurred from 2018 to 2021, during the tenure of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party. However, this short-lived marriage of convenience had a bitter ending.

Imran Khan, the former Prime Minister of Pakistan, and chairman of PTI was removed from office through a vote of no confidence in the national assembly. Initially, he alleged it was a U.S. conspiracy aimed at removing him from power. However, a few months later, he shifted the blame to the Pakistan army and effectively gathered a substantial political following that openly expresses its disapproval of the military. What sets Mr. Khan apart from other political leaders is his embrace of populist politics. The populist tendencies of Khan’s leadership have never been more evident before than now. From circumnavigating the constitutional processes, questioning, and targeting constitutional structures, and creating binaries among the masses as outsiders and insiders, Imran Khan seems to have checked all the boxes of a populist leader. Moreover, the tone and the political discourse that Khan has introduced in Pakistani politics are unprecedented.

The current political crisis in Pakistan is being referred to as extraordinary and unprecedented by some, while many political experts and journalists believe it is a recurring loop or vicious cycle that repeats itself every few years. What sets the current crisis apart from past events is the unprecedented level of openness to the public and the public outrage against the military institutions. In a recent event on 9 May 2023, Imran Khan was arrested by Islamabad high court under some corruption charges. The arrest of Khan led to significant outrage and anger among supporters of the PTI. The situation took a chaotic turn when attacks were carried out on the Army General Headquarters (GHQ) in Rawalpindi, and the Corps Commander House, also known as Jinnah House, in Lahore. These events not only caused havoc for those involved in the attacks but also for the PTI’s political leadership. Many PTI leaders were arrested, imprisoned, released on bail, and re-arrested, and many have quit not only their political party but politics altogether.

Those responsible for the attacks on the GHQ and Corps Commander House are being tried in military courts rather than civil courts. Furthermore, thousands of PTI supporters have been arrested in less than a week. While these actions are condemnable, it is crucial to question where the problem lies. Looking back at recent history, when the PTI itself was in power, a long list of false cases was made against their opposition. Many people were falsely imprisoned, accused, and persecuted. At that time, when it suited the PTI’s interests, they did not take any measures to stop or at least condemn the mistreatment of their political rivals. On the contrary, they not only endorsed it but also threatened severe consequences for their political opposition if they did not comply. It now appears that the actions they took against their political rivals are returning to haunt them, albeit with greater speed and severity. And now the current government is doing the same.

The Pakistan army, previously an obscure force operating from behind the scenes, has thrust itself into the public eye, shedding its taboo status and becoming a subject of open discussion. The former Chief of Army Staff General Qamar Javed Bajwa, on the verge of retirement, boldly accepted complete accountability for the chaotic state of politics. He reassured the public that the army would prioritize its core responsibilities and refrain from any political involvement. This declaration initially brought a sense of renewed hope, akin to a breath of fresh air. However, the relief was short-lived.

Immersed in a pool of problems and formidable challenges, it seems difficult to pinpoint a direct and singular solution for Pakistan. The challenges faced are multifaceted and demand an intricate solution. While many solutions have been proposed by the experts over the years, there appears to be an absolute lack of political will to address these issues. The underlying reason for this indifferent attitude is that personal and short-term goals consistently take precedence over national and long-term goals.

Nevertheless, to bring democracy into practice and reinstate the sanctity of institutional boundaries, Pakistan needs to take certain measures. First and foremost, Pakistan army would have to take a clear and strong stance by distancing itself from politics, maintaining neutrality, and avoiding involvement in political processes. Such a step can be a significant turning point in Pakistan’s democratic journey.

Similarly, the judiciary in Pakistan should not confine itself to juristocracy and hyperactive judicial activism, which can encroach upon political sovereignty. Instead, it should operate within a balanced framework that respects the separation of powers. Legislative assemblies should introduce reforms aimed at strengthening democracy and minimizing external influences in political processes.

Political parties have a vital role to play in upholding democracy. They should strive to build political consensus on shared norms and a code of conduct. Key aspects such as free and fair elections, civil liberties, free media, equality, and peaceful transfer of government must be areas of convergence among political parties. It is crucial that all political parties accept the democratic practices and results thereof. Populist rhetoric should be avoided to gain public support, as it can undermine democratic processes.

Therefore, it is imperative that all the stakeholders identify and acknowledge the magnitude of the issues and display a collective resolve to address these issues effectively.

The views presented in this article are those of the speaker or author and do not necessarily represent the views of DoD or its components.

Law, Order, and the Future of Democracy in Pakistan

Subscribe to this week in foreign policy, stephen p. cohen stephen p. cohen former brookings expert.

May 21, 2012

Editor’s Note: Paper presented to the NIC-EUISS Conference on Pakistan “Looking towards 2025: drivers of democratic consolidation and stability,” Paris, France, 20-21 May 2012

The optimistic title of this conference attempts an even more optimistic objective: that we understand the factors that will shape Pakistan by the year 2025, and predict how these factors will influence Pakistan’s slow crawl towards democratic consolidation.

There is also a contradiction: democratic consolidation may be inversely related to “stability” if by that we mean the continuation of an oligarchic political order, usually termed “the establishment”. Over sixty years of an establishment-dominated political order—whether by the army or by the army in cooperation with civilians—has not made Pakistan a democratic country in most senses of the word, except that the aspirations of many Pakistanis are to have democracy Pakistan-style. This aspiration is held by many in the army, which would like to have political leaders that can govern Pakistan up to its own high standards.