Criminology, Sociology and Policing at Hull

Student research journal, the forgotten victims: exploring the reasons male rape is still under-represented today.

In society it is inferred that sexual violence is a ‘women’s issue’, and only woman can be victims of sexual misconduct. The study of male rape and male sexual victimisation has been heavily overlooked. This dissertation aims to examine the reasons for this under-representation, by exploring the literature on the media representations of male rape, the male rape myths and rape myth acceptance in society, the theory of masculinities, and the reasons rape in prison institutions is under-researched. This is a literature-based review, and all of the materials collected has been via secondary research.

This dissertation has found that male rape and sexual victimisation are still extremely under-reported and underrepresented issues in society. Media representations of male rape do deviate considerably from the reality of male rape, and that newsprint and film, are main contributors to the rape myths ingrained in society. However, more recent media depictions in soap operas and documentaries have shown more realistic portrayals. Despite this, it has been highlighted through research studies that rape myths are still widely accepted. The acceptance of rape myths can be detrimental to a victim, as victims may be attributed more blame for the offence. It is therefore important for future research to discover ways in which these myths and stigmatising views can be eradicated to ensure awareness around male sexual victimisation is raised.

As well as rape myth acceptance, this study has observed that there is an underreporting of male sexual victimisation, that is partly due to the presence of hegemonic masculinity and gender role socialisations. This, together with the politicisation of the issue of male rape in prisons, has had a disadvantageous impact to the level of research undertaken in this area, particularly regarding incarceration.

Finally, this research has demonstrated the need for further academic research into society’s attitudes toward male sexual victimisation, to explore what has changed since previous studies, and what more can be done to ensure that male rape is better represented.

Author: Lucy-Kay Haywood, April 2020

BA (Hons) Criminology with Law

Acknowledgements

I would like to start off by thanking my dissertation supervisor, Dr David Honeywell, for his advice, support and guidance in completing this dissertation.

I would also like to thank my wonderful parents, Kay and Bruce Huggins, for their unconditional love, support, and encouragement throughout my time at university, and for always believing in me.

And lastly, to my wonderful partner, Antony Carmichael, thank you for all your love, patience and support, as I would not have been able to complete this degree without it.

1 Introduction

The illicit acts of rape, sexual assault, and sexual victimisation did not have any prominence in the United Kingdom until the rise of the Women’s Liberation Movement in the 1970s. Feminists within this movement sought to expose the issue of male sexual violence against women, with great emphasis given to the female rape survivor (Petrak, 2002). One of the most notable studies undertaken was Ask any woman: A London inquiry into rape and sexual assault, which revealed the prevalence, characteristics and the circumstances that surrounded these offences, and the effects the experience of rape can have on a female victim. Feminist activists subsequently advocated that there was an urgent need for social and political reforms, and numerous ‘Anti-Rape’ and ‘Women Against Rape’ campaigns emanated (Petrak, 2002). This resulted in governmental reforms, changes in legislation, and the introduction of support services, such as the Rape Crisis Centre, which assists female survivors in coming to terms with their victimisation (Petrak, 2002). The extensive amount of academic research into male sexual offending and female victimisation that followed, and the increased societal awareness around these issues, inferred that sexual violence is a ‘women’s issue’, and only women can be victims of sexual misconduct. Consequently, the study of male rape has been heavily overlooked, and male victimisation has received very little attention, not only in the Criminal Justice System and in academic literature, but also in the public domain (Javaid, 2018).

It may be questioned whether society’s reluctance to acknowledge the existence of male rape is partly due to the fact that homosexual activity was once criminalised in the UK, and was considered by many to be a ‘detestable’ and ‘abominable’ act (Ng, 2014:235). These views were reflected in the Buggery Act 1533, enacted during the reign of Henry VIII, which defined buggery as ‘an unnatural sexual act against the will of God and man’ (Ng, 2014:235). Although the legislation against homosexuality was abolished in 1967, and the collective attitudes of society are now more accepting of this culture, these homophobic views may still persist (Ng, 2014).

Nevertheless, in the late 1980s and the early 1990s, male rape started to gain some recognition within society. This act was initially conceived as either an affiliation of incarceration, or alternatively, as a violent act associated with the homosexual culture (Abdullah-Khan, 2008). Prior to 1994, only a female could be a legally recognised victim of rape, as the law specifically defined rape as vaginal penile penetration. Whereas, for a male, non-consensual anal penetration would be classified as buggery. The offence would be charged as an indecent sexual assault and would carry a sentence of six months to ten years imprisonment, as opposed to rape, which is an indictable offence and carries a maximum sentence of life imprisonment (Elliot & Quinn, 2008). It was not until the introduction of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994, that for the first time in English law it was recognised as rape for a man to anally penetrate another man without their consent. The Sexual Offence Act 2003 re-defined this legislation further to also include non-consensual oral intercourse (Elliot & Quinn, 2008). These acts mean that the offence of male rape is now legally of an equal stature to female rape (Lowe & Rogers, 2017).

Between 2015 and 2016 the official police statistics from the 43 forces in England and Wales revealed that there were 3,452 reported offences of male sexual assault, and, 1,276 reported offences of male rape (Pearson & Barker, 2018). The recent statistics show that by the end of 2017 there was a significant increase, as 4,342 males had reported being the victim of sexual assault, and, 1,625 males had reported rape (Office for National Statistics, 2018). Although this data suggests that more men are being encouraged to report their victimisation, these statistics need to be interpreted with caution. From a collection of studies and Home Office reports in 2013, it has been estimated that each year 75,000 men become victims of sexual assault, with approximately 9,000 men becoming victims of rape (Pearson & Barker, 2018). According to the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW), only 3.9% of males report their victimisation to the police, therefore, a considerable number of cases are un-reported, and the actual prevalence figures for these offences are unknown (Office for National Statistics, 2018).

In spite of the reformation of the law 26 years ago, male rape is still an under-reported and under-discussed issue in society today. Research by many scholars, such as Walker (2005), Carpenter (2009) and Mclean (2013), argues that the reason for this is that society still holds prevailing misconceptions about male victims of sexual misconduct (Pearson & Barker, 2018). One explanation for these misconceptions may be the repercussions of the mass media. The media is a powerful agent of socialisation as it reinforces societal norms and values, and it can influence and shape the attitudes, knowledge and views of society. Society’s ideology of what constitutes as male rape, may therefore be determined by how the media represents sexual violence and victims of rape (Sacco, 1995). Although there has been an extensive amount of academic research conducted on the media representations of female rape, there has been a sparse amount of research into the media representations of male rape and male victimisation, and this is a serious issue that needs addressing.

Thus, this dissertation will examine the reasons for this gap in the literature, with particular focus on exploring the rape myths in society, rape myth acceptance, and whether the media enhances rape myths and negatively depicts male victims, or, whether it dispels these myths by accepting the reality of male rape and sexual assault, and promotes change in societal attitudes. A theoretical framework of Masculinities will also be provided, and the reasons rape in prison institutions is under researched will be discussed, to further understand to what extent the under-representation of male rape is an issue in society, and the issues that surround male victimisation. Propositions will then be made on how to eradicate these issues, so that awareness is raised, stigmatising views are eliminated, and to ensure that this topic is no longer an unspoken phenomenon within society.

2 Methodology

Data collection:.

The topic of this research is of a sensitive nature, and it would have been inappropriate to collect primary data from human participants. This research has therefore been conducted and presented as a literature-based review, and all of the material collected has been via secondary research. The material and data collected has been derived from a variety of sources, including: academic books, journal articles, newspaper articles, webpages, government publications and reports, organisational campaigns, and documentaries.

Ethical Considerations:

Given the sensitive nature of this study there were certain ethical considerations that had to be adhered to. As this is a literature-based review no primary research was undertaken and there were no participants involved. All of the material obtained was in the public domain, and no confidential, private, or illegal sources were used. The information discussed throughout this dissertation is held to the highest level of objectivity, and all of the contributions by authors have been acknowledged via the Harvard referencing system. This research study was ethically approved as established in the Appendix 2.

Strengths and limitations of research:

By using secondary research instead of primary research, it has allowed for a more extensive amount of material to be collected and utilised. This has therefore enabled this research to be more generalisable, and to be high in validity (Crossman, 2019). Nevertheless, as male rape is an under-researched topic, there was not a lot of specific material in the existing literature regarding what this research is intended to discover, especially with respect to male rape and the media. Furthermore, with the existing research studies, there was a lack of clarity on how some of these had been conducted, analysed and presented, and, certain studies undertaken were specifically related to the American culture, rather than the culture in the United Kingdom. This however, was taken into consideration, and these studies and all research papers were closely scrutinised.

3 Media Representations of Male Rape

In a mediated, consumption-oriented society, much of what is considered as important to the public is based on the selection, organisation, production and dissemination of news stories within the mass media (Sacco, 1995). It has been argued that news media is a social construct within society. The way news stories are framed can have considerable power in influencing and shaping the public’s knowledge, attitudes, and opinions on the events that occur around the world, and societal issues that arise, particularly those issues relating to crime. As quoted by Kellner (1995) in Pollak and Kubrin (2007:59) ‘Media images help shape our view of the world and our deepest values; what we consider good or bad, positive or negative, moral or evil’. The media is therefore believed to be one of the most predominant forms of social control, and a powerful agent of socialisation (Sacco, 1995; Jewkes, 2015).

Necessary characteristics are required for a story to become newsworthy, and these are determined by news values; the value judgements held by journalists, and editors, which guide them in the news production process on the amount of prominence a news story should and will receive (Greer, 2003). News values were first credited to Galtung and Ruge in 1965, however, the revised versions by Jewkes (2004) are more culturally accurate to coincide with the societal values of the 21 st century. Sexual crimes, violence, proximity and atypicality are four pre-eminent news values within news outlets and entertainment formats, and thus, sexual offences and the act of rape are pervasive themes within the mass media (Jewkes, 2015). This can be supported by Williams and Dickinson (1993) who state that in the United Kingdom, 30% of the media’s overall news coverage is devoted to crime, with 65% of crime news focusing on stories that involve interpersonal violence and sexual offence victimisation. The further a crime departs from the cultural norms in society, the more newsworthy and intrinsically entertaining the media tend to consider it (Naylor, 2001). Yet, the media’s enduring tendency to focus on crimes of a sexual nature can become problematic.

McCormick (1995) argued that although the media can be seen as a reflection of reality, it in fact distorts reality, and when sexual misconduct is featured, the circumstances surrounding the offence, the perpetrators, and the victims can be inaccurately represented (Abdullah-Khan, 2008). Many individuals rely on the media as it is their only source of information. Yet, if they do not have any other experiences outside of the media domain, or lack alternative sources of knowledge, then they will have difficulty evaluating the media’s credibility. The way the media depicts sexual misconduct will then be taken as fact and the public will believe this to be an accurate representation of their social reality (Thacker, 2017). 75% of the public have claimed that their knowledge and views on crime are based on what they have read or seen in the news (Pollak & Kubrin, 2007). Furthermore, a study by the Kaiser Family Foundation in 1999, revealed that 61% of teenagers aged between 13 and 15 relied on news, television and film media to educate them on topics relating to sex, sexual assault, and sexual transmitted diseases, alongside alcohol, drugs, and violence (Bufkin & Eschholz, 2000). It is therefore important, given the media’s influential impact on societal perceptions, to understand how sexual offending and sexual victimisation are portrayed in the media, particularly in relation to male rape, as this coverage will not only influence society’s ideology of male rape, it will also have a powerful impact upon male victims and how they respond and contend with their victimisation.

Rape Myths in Society

Sexual violence is primarily depicted as a male-perpetrated-female victim attack. The term ‘rape victim’ is expressed as inherently female, and until recently, male victims of a sexual offence have been largely overlooked and ignored in the media (Abdullah-Khan, 2008). Research proposes that this marginalisation and invisibility of male victimisation is due to the perpetuation of rape myths, and the prevailing misconceptions society has about male rape (Turchik & Edwards, 2012).

Rape myths have been defined by Burt (1980) in Turchik and Edwards (2012:211) as ‘prejudicial, stereotyped or false beliefs about rape, rape victims, and rapists.’ The myths that surround male rape have been identified as, but are not limited to: males cannot be raped as ‘real men’ can defend themselves, male rape only occurs in prison institutions, women cannot sexually assault males, only homosexual men are victims or perpetrators of male rape, male rape can cause homosexuality, if the victim was under the influence of alcohol or drugs then it was their own fault, men are not affected by rape, and, if a physiological reaction occurs (an erection or ejaculation) during the attack, then it must mean that they ‘wanted it’, signifying consent (Turchik & Edwards, 2012; SurvivorsUK, 2020).

Although these myths are widely accepted within society, a number of studies have shown that these are mistaken beliefs and they distort the reality of rape. Mezey and King’s (1989) study revealed that men, like women, can experience an overwhelming sense of fear and disbelief during their attack, and the majority of their participants reacted to their assault with frozen helplessness. Out of 119 male rape cases, Hodge and Canter (1998) found that frozen helplessness was a response in 60% of them (Javaid, 2015). Furthermore, Coxell and King’s (2010) report on Tonic Immobility; a temporary state of muscle rigidity and immobility, argued that during a sexual assault, men may experience ‘freezing’ and will be unable to retaliate (Pitfield, 2013). This is evidence to the contrary that ‘real men’ cannot be raped as they are able to defend themselves. McMullen (1990) has further challenged the myth that male rape is solely a homosexual issue, as his results showed that ‘the sexual identity…of the vast majority of male rapists is heterosexual’ (Javaid, 2015:279). Mezey and King (1989) also disclosed in their research sample that 10 male victims of rape were homosexual, 8 were heterosexual, and 4 were bisexual. Nevertheless, the data from these studies need to be analysed with caution. McMullen’s results were drawn from clinical observations rather than an empirical study, and this purely anecdotal conclusion may have formulated a biased argument. Additionally, Mezey and King only placed advertisements for participants in homosexual magazines, which may have provided an unrepresentative sample and caused their results to also be biased (Javaid, 2015). Yet, these studies show that all men have the potential to either be the assailant, or the victim of rape, and it is not a reflection of their sexual orientation. Groth and Burgess (1980) provide support for this, as they assert that male rape is predominantly an assertion of violence, dominance, and control over the victim, and the enhancement of masculinity, rather than being motivated by sexual gratification (Abdullah-Khan, 2008). A further study by Carpenter (2009) revealed that the aftermath of sexual victimisation does affect males physically and psychologically, in even more ways than it affects female victims, and, in regards to the final myth of a physiological reaction occurring, McLean (2013) discovered that men are just as likely to have the same reaction should they experience feelings of extreme fear or anxiety, or, if they are involved in a stressful event (Pearson & Barker, 2018).

The acceptance of any one of these myths can be detrimental to how male victims are perceived, treated, and depicted by society; and it is therefore important to explore whether the media are reinforcing these myths, or, whether they are starting to encourage a change by dispelling these myths through the utilisation of television programming, film, and accurate news reporting.

Rape Myths in the Media

Rape myths in the press.

Prior to 1989, there was no newspaper or press coverage in the United Kingdom of male rape, however, research indicates that media reporting of this phenomenon is now on the rise. Abdullah-Khan (2008) conducted a content analysis on newspapers across the UK, between the years of 1989 and 2002, that reported incidents of male rape. Out of 413 articles analysed, 208 held stereotypical and sensationalised views of male rape, particularly perpetuating the myth that male rape is a homosexual issue. Articles from the Daily Record, The Mirror, The Herald, and The Sun contained headlines such as: ‘Jail warden in male rape quiz; police question guard over string of gay sex attacks’, ‘Gay rapist hunt arrest’, ‘Man raped at gay meeting place’ and ‘Raped by gays’ (Abdullah-Khan, 2008:169). A further study by Franuik et al. (2008) also draws attention to this, as they found an article on the BBC news website in 2005 that had the headline ‘Man raped in city’s gay village’ (Pitfield, 2013:21). Although perpetrators may be homosexual, headlines such as these insinuate that all acts of male rape are homosexual in nature, sexually motivated, and can only happen to individuals who are part of the homosexual subculture thereby preventing male rape to be considered amongst the heterosexual population (Abdullah-Khan, 2008).

It has been evidenced through research that male rape is primarily committed by an acquaintance of the victim, in a private setting. However, as the media are highly selective and report crimes of an atypical nature, they distort this fact by focusing their coverage on stranger rapes that occur in public locations (Javaid, 2014). In the content analysis by Abdullah-Khan (2008), it was identified that not only do the news media focus on stranger rapes, they also place great emphasis on multiple assailant cases of rape. ‘Man raped at knifepoint in Underground lavatory’, ‘Three sex beasts gang rape man yards from police station’, and, ‘Male rape trio hunted’, are just some of the sensationalist headlines used within the 13-year period (Abdullah-Khan, 2008:167). In reality these cases are extremely rare, yet, portraying this crime in this way can fuel moral panics, reinforce false beliefs, and keep society and victims of rape ill-informed. McMullen (1990) further argues that the media encourages the myth surrounding the physicality of male rape, as he discovered that many news reports discuss the shock and disbelief that a physically strong, masculine male, is incapable of defending himself, and have succumbed to been overpowered by another man (Javaid, 2015).

Considering the influential role that the media plays in society, representations of male rape ought to be disseminated in an accurate, objective, free of prejudice manner, which, as the evidence presented so far suggests, does not occur. It can be argued that these depictions of male rape create negative societal attitudes towards male victims, which can then cause the male survivor to experience secondary victimisation. Furthermore, as these representations are misleading, it may discourage victims from reporting an incident to the police, or, from seeking support, medical, or psychological treatment, as these portrayals may not be in line with their own experience. They may not view themselves as a ‘real victim’, and they may also fear that they will not be believed because society holds these myths to be true (Walfield, 2018).

Nonetheless, it has been demonstrated that a number of news outlets do encourage the dispelling of rape myths in society, which can be supported by Abdullah-Khan’s (2008) content analysis study. Out of the 413 newspaper articles analysed, 110 featured headlines, stories and discussions that portrayed an accurate, non-stereotypical view of male rape and male victimisation. One headline in The Independent stated ‘I’m male, 55 and overweight. Why rape me?’ (Abdullah-Khan, 2008:164). Although this headline suggests that the sexual preference and sexual orientation of the assailant is important for the commission of this act, the article does proceed to challenge the myth that male rape is a homosexual matter. It emphasises the fact that all men can become victims of rape, regardless of their age, attributes, ethnicity, and sexuality. Other articles also accentuated the traumatic effect that this offence can have on the victims, challenging the myth that men are not affected by rape, and they drew particular attention to the reasons why men may be reluctant to report their victimisation to their peers or to the authorities (Abdullah-Khan, 2008). These articles, however, were not displayed on the front page of the newspapers, where they would have had the most impact on their audience. This study also unveiled that tabloid newspapers, like The Sun and The Mirror for example, sensationalise, exaggerate and distort male rape, thereby reinforcing the rape myths, whereas, broadsheet newspapers, such as The Independent and The Herald, are more informative and factual in their journalism, using academic studies to support their discussions, and therefore dispelling the myths ingrained within society (Abdullah-Khan, 2008).

The majority of research on the representation of male rape in the newsprint media has focused on the American press, and the American culture. Whilst there is a copious amount of research on female rape in the newsprint media in the United Kingdom, the only study in existence for male rape is the study by Abdullah-Khan. This study focused on newspaper articles between the years of 1989 and 2002, which is now more than 18 years ago. The collective attitudes in society may have revolutionised since these dates, particularly in the wake of the MeToo movement, which in turn, may have improved the production of news stories on male rape. Further research in this area is therefore urgently required.

Rape myths in film

When male rape is depicted in film, it is primarily associated with the prison, or prison like establishments, reinforcing the myth that male rape only occurs in prison institutions. Eigenberg and Baro’s (2003) content analysis on prison films found that male rape is portrayed as a common and inevitable attack, when in reality, prison rape occurs infrequently. They also argue that presenting rape in this context, endorses the belief that this is an acceptable and normal consequence of prison life. Graphic media depictions or insinuations of rape, such as in the film American History X, can suggest that rape is a punishment for the crimes committed. During the rape scene in this film, a prison officer witnessing the attack, exits the shower area closing the door behind him, intentionally disregarding the assault, thereby not responding to this issue seriously. Depictions like these may add to the silence surrounding male rape, as men may view their victimisation as punishment, or, believe that others will not take their experience seriously (Eigenberg & Baro, 2003; Pitfield, 2013). It has also been identified by Levan et al. (2011) that prison rape can be portrayed as comedic, with particular focus being on this misconduct occurring in the shower, and references such as ‘don’t drop the soap’ being used. These references then start to become cultural catchphrases, constructing prison rape as a joke, and again, it not being treated as a serious issue.

Research has also shown that male rape and male sexual assault are depicted facetiously in comedy genre films. Henderson (2019) stated ‘Sexual assault of men as comedy is so ubiquitous and so normalised that you may not have even noticed it shows up everywhere’. This is particularly noticeable when films feature men been coerced into having sexual intercourse with female characters, promoting the myth that women cannot sexually assault a man. This can be illustrated in the 2002 comedy 40 Days and 40 Nights, and, in the 2005 comedy The Wedding Crashers, which are both highly popular films (Pitfield, 2013). Both of these films feature a scene where a male is handcuffed to a bed and forced to have sexual intercourse with female characters. Although in England and Wales a female cannot legally rape a male, this would be classed as sexual assault. In reality, this can be a dehumanising, traumatic experience for the victim, which can have lasting effects, yet in film, this is portrayed and classed as a humorous incident. The sexual assertiveness of the female is considered to be seductive, and, as it is a false belief that men are always willing to partake in sexual activity, these scenes are perceived as a male fantasy rather than a sexual assault (Pitfield, 2013; McKeever, 2018).

If society endorses the stereotypical view that men are ‘always up for sex’, then it may make some women rationalise their actions into thinking this behaviour is acceptable, as it may be seen as giving the victim what they desire. Men may also not recognise that the experience they have had is in fact a sexual assault, and if they experience emotions of confusion, anger, or distress it may make them not only question their masculinity but also their sexuality (McKeever, 2018). Furthermore, these depictions of male rape and male sexual assault imply that the popular film culture does not take male victimisation seriously, it portrays these offences as a joke, and it primarily promotes the myths that male rape only occurs in prison, and, women cannot sexually assault men.

Rape myths in television programmes

So far, it has been demonstrated that the media often presents male rape in a sensationalist, distorted, humorous manner. It has, however, been recognised that there has been an increased attempt to address these issues surrounding male rape, through the use of documentaries and several serious storylines within popular television programmes in the United Kingdom. Documentaries, such as Male Rape: Breaking the Silence (2017), emphasised the need for more accurate representations in the media, as it followed the story of three male rape victims and their experiences, dilemmas, concerns, and the effect their victimisation had upon their mental health. Yet, the most notable programming has come from the male rape stories featured in the soap operas Hollyoaks in 2014, and, Coronation Street in 2018, which aimed to dispel the rape myths in society by presenting an accurate representation of this crime, and to show the audience the effects this crime can have on its victims.

Hollyoaks and Coronation Street were the first soap operas in the UK to highlight the issue of male rape, drawing particular attention to the culture of silence that surrounds male sexual assault. Although the two have different approaches in documenting this crime, the rape myths within society are strongly challenged in both. In each storyline the perpetrators are heterosexual men, and acquaintances of the victim. The victim in Hollyoaks is a homosexual male, whereas, in Coronation Street, the victim is a heterosexual male (Hollyoaks, 2014; Coronation Street, 2018). This is noteworthy, as it not only dispels the myth that male rape is purely a homosexual issue, it also dispels the myth that men are not affected by rape, as the two programmes showed the differing ways each character struggled with their victimisation. Furthermore, the victim in Coronation Street was under the influence of alcohol and a date rape drug, and, both victims were unable to defend themselves against the attack. This brought to the public’s attention the fact that a ‘real man’ can be raped even if they do not retaliate, and, that men are still credible victims, even if they are under the influence of drugs and alcohol at the time of the assault (Hollyoaks, 2014; Coronation Street, 2018).

The reason that these storylines were so accurate and compelling in their representation of male rape is that producers of each show were advised by real survivors and had support from the Survivors Manchester charitable organisation. The programmes not only helped to transform societal understanding on male rape, they also proved influential to male victims of rape (Survivors Manchester, 2020). According to the Ministry of Justice, between the years of 2014 and 2018, there has been a 201% increase in the number of men accessing Ministry of Justice rape support services (HM Government, 2019). Organisational charities, such as Survivors UK and Survivors Manchester, have also reported that as a result of these programmes, there has been a 1,700% rise in calls to their helplines from the victims, and the families of victims, who have been raped or sexually assaulted (Morgan, 2019). It therefore illustrates that accurately conveying such powerful and emotive issues, encourages victims to speak out and seek support, and it is slowly breaking the silence around male victimisation.

The research presented in this chapter illustrates how media representations of male rape can deviate considerably from the reality of male rape, and that they are the main contributor to the rape myths in society. The sensationalist reporting and mis-representation of this offence in film keeps society misinformed, and presents a distorted picture of the classification of male rape, the prevalence, and the circumstances surrounding the offence. These erroneous depictions can have negative ramifications as it can result in the stigmatisation of the victim, and, they can also infer that rape is acceptable in certain circumstances, but not in others. If the victim or the offender does not fit the mythical profiles portrayed in the media, the credibility of their victimisation may be brought into question. This can influence the attitudes and response of law enforcement, the criminal justice system, jurors who will hear the case if it proceeds to court, policy makers, and voluntary organisations that support the victim (Javaid, 2015).

Nonetheless, it has also been evidenced that male rape is finally starting to become recognised as a serious offence in the media through television programming. Cohen (2014) argued that the more positive media representations of male rape, the more awareness there will be, and consequently, victim reports will rise leading to constructive governmental policies to be implemented, to the benefit of society (Javaid, 2015). This view is confirmed by the enactment of the ‘Break the Silence on Male Rape’ campaign. In 2014, a month after the Hollyoaks storyline aired, the government, for the first time, spent £500,000 on funding the already existing support services available for male victims, whilst also introducing extra provisions. James Sutton, the actor who played the rape victim in Hollyoaks, used his media profile, together with Survivors Manchester, to help secure this funding, whilst also expressing the necessity for the government and for the media to continue accurately representing and raising awareness of the issues surrounding male rape and sexual assault (Ministry of Justice, 2014). This media presence has been influential, and the dispelling of rape myths has begun to eliminate the negative and stigmatising views held in society. It has been argued however, that these stereotypical ideologies are embedded in the social construction of masculinities and gender role socialisations, which will be discussed in the following chapter.

4 The Theory of Masculinity

The social construction of gender and masculinity plays a critical role in the way male rape and sexual assault is experienced, perceived and understood. Raewyn Connell’s (1987) theory of masculinity has been the most influential in understanding the issues that surround male victimisation, as she argues that men, through gender role socialisation, are hierarchically organised into hegemonic or subordinated masculinities (Petersson & Plantin, 2019).

Hegemonic masculinity is at the top of this hierarchy, and it refers to the chauvinistic attitudes and practices among men that perpetuate male superiority and gender inequality in society, and justify the subordination of women and marginalised men (Jewkes et al., 2015). According to Connell (1995), heterosexuality is pivotal to the hegemonic ideals in the Western culture, in addition to being: white, middle-class, dominant, sexually assertive, strong and invulnerable. By contrast, subordinated masculinity, which is at the bottom of the hierarchy, is most notable for been associated with homosexuality, emotionality and effeminate behaviour (Petersson & Plantin, 2019). Men are institutionalised into believing that they need to adhere to the hegemonic ideal and that perceived weakness is frowned upon. Donnelly and Keyon (1996) state that this socialisation and the societal expectation of men creates ‘the myth of male invulnerability’, which disallows men to be recognised as victims of a sexual offence (Abdullah-Khan, 2008:23).

Experiencing sexual victimisation is the antithesis of the hegemonic ideal, as labels associated with subordinated masculinities, such as weakness, submission and homosexuality will surface. This deviation from the normative roles of masculinity can have a ruinous impact on males, as it can undermine their own sense of invulnerability, whilst also challenging their masculine identity, and what it means to be ‘a man’ (Pretorius, 2009). A study by Walker et al. (2005) shows support for this. Out of 40 sexually assaulted British men, 70% reported having lasting issues with their sexual orientation, and 68% of men had a ‘damaged masculine identity’. It was further noted that 72% of men had reported that losing the hegemonic masculine ideals of being powerful and in control actually felt worse than the sexual encounter itself. The constructed image of sexual victimisation violates the socially constructed tenets of masculinity, coinciding with the myth that ‘real men’ cannot be raped. Male survivors may therefore enter into a state of disbelief and denial, feeling an intense sense of shame and self-blame for not been able to defend themselves against the attack (Roberts, 2013). Men will consequently cope with their victimisation in silence, as they are under the misguided belief that they ought to be able to handle such adversity alone, and, as Lisak (1995) discovered, men will try to regain their masculine identity by overemphasising normative attributes, such as responding to their assault with overcontrolling, hypersexual, violent or aggressive behaviour (Petersson & Plantin, 2019).

Considering that hegemonic masculinities are closely related to heterosexuality; male victims of rape are frequently perceived as homosexual. If male victims accept this rape myth to be true, they may start to question their own sexuality. Kassing et al. (2005) found that a majority of heterosexual participants in their study believed that failing to defend themselves against the attack indicated that they subconsciously wanted the sexual assault to occur in some way. This was particularly true when a physiological reaction occurred. Lockwood (1980) also identified that a major factor concerning the trauma victims experience was appearing ‘gay’ or ‘less of a man’ to others (Walker et al., 2005:70). In regards to a female perpetrated sexual assault, it is a culturally held belief that men actively seek and are willing to engage in sexual activity. This therefore implies that it is improbable that a man would be reluctant to participate in, and not enjoy, forced sexual activity when it is initiated by a female (Fisher & Pina, 2012). The victim may then get accredited more blame for their assault. This is evidenced by Smith et al. (1988), as the results of their study disclosed that society believed male victims to have encouraged their attack, and instead of perceiving them as victims of assault, they regarded the incident to have just been an unsatisfactory experience (Chapleau et al., 2008). Male victims may therefore question their own experience and not recognise that they have in fact been a victim of sexual assault, and, if they experience emotions of distress and confusion, they may also query their sexuality for not wanting the encounter to occur. Physically retaliating to an attack by a male perpetrator refutes the notion that the victim is homosexual, however, retaliating to an attack against a female perpetrator may challenge the victim’s sexual identity. Research has shown that heterosexual men are unlikely to disclose a female perpetrated attack because they believe others will not take them seriously, and they want to ensure that their masculine reputation stays intact (Javaid, 2016; Pearson & Barker, 2018).

In society homosexual men already embody a subordinated masculinity, thus, when they are sexually victimised, they can experience a form of secondary victimisation. Although the collective attitudes of society are now more accepting of the homosexual subculture, homophobic and heterosexist attitudes still persist (Javaid, 2016). Research has identified that society holds a homosexual victim more at blame for his assault, than they do a heterosexual victim, and they are deemed as less deserving of sympathy and support. Their victimisation is often disbelieved, and, as they can face stereotypical views that suggest that they ‘wanted it’, ‘got pleasure from it’, or that they ‘colluded in their own abuse’, the offence can go unacknowledged as a ‘real rape’ (Weiss, 2010:292). This condemnation of homosexuality may explain the existence of the myth that male rape is a homosexual issue, and it may also explain why homosexual victims are less likely to disclose their victimisation and so are very rarely heard. In addition, if these homophobic views are internalised, it can have adverse consequences. It has been evidenced through research studies that men erroneously believe that their sexual victimisation was punishment for being homosexual, and that they deserved the attack for not conforming to the heteronormative roles in society (Walker et al., 2005; Dunn, 2012). In the aftermath of an attack, a victim’s self-identity may alter, and males can begin to have negative perceptions of themselves. When behaviour that was previously associated with the consensual act of homosexuality, becomes associated with an act of violence, homosexual men can find it difficult to view their sexual orientation in a positive way (Dunn, 2012). This is illustrated in the study by Walker et al. (2005:71), as one participant quoted ‘Before the assault I was proud to be homosexual; however, now I feel ‘neutered’. I feel sex is dirty and disgusting and I have a real problem with my sexual orientation.’

Contrary to the myth that men are not affected by rape, the research presented so far suggests otherwise. In conjunction with the loss of a masculine and sexual identity, studies have also revealed that male victims can experience an array of psychological issues, similar to that of female victims. These have been shown to include; a loss of self-esteem, symptoms of depression and anxiety, suicidal ideation, substance abuse and dependency issues, sexual dysfunction, and, an onset of post-traumatic stress disorder (Mezey & King, 1989; Walker et al., 2005; Turchik & Edwards, 2012; Dunn, 2012).

It is a widely held belief that the silence that surrounds male sexual victimisation is due to the reluctance of men to admit weakness or to disclose vulnerability. Masculinities and gender role constructions within society are therefore crucial in understanding the victims’ perceptions of their experience, how they view themselves, and, the attitudes of those to whom men disclose their encounter (Javaid, 2016). In a culture that accentuates hegemonic masculinity and male superiority as the normative ideal, a male rape victim is constructed to be perceived as feminine, weak and submissive, and therefore unaccepted and discredited. Society places a lot of pressure on men, from a young age, to conform to this normative role, with particular emphasis deriving from the powerful and pervasive media system, which provides a steady stream of images that define manhood as being connected with power, dominance, and control (Abdullah-Khan, 2008). The literature indicates that rape myth acceptance in society is determined by societal perceptions of these gender roles, and that acceptance is more likely to cause homophobic and heterosexist attitudes towards victims of rape (Walfield, 2018). It is therefore important to review whether these rape myths are believed to be true, and if so, to what extent.

5 Rape Myth Acceptance

Although an extensive amount of research has been undertaken on female rape myth acceptance, research on male rape myth acceptance remains limited. The first study to explore the adherence of rape myths for male victims was conducted by Struckman-Johnson and Struckman-Johnson (1992). This study focused primarily on the myths that men cannot be raped, men are to blame for their assault if they did not retaliate, and, men are not affected or traumatised by rape. Each of these myths was presented twice to the participants, once with a male perpetrator and again with a female perpetrator. Although the results of this study indicated that the majority of participants disagreed with these myths in some manner, 49% of male participants, and 27% of female participants accepted at least one these myths to be true (Struckman-Johnson & Struckman-Johnson, 1992). It was further documented that male participants endorsed these myths to a greater extent than the female participants, particularly when a female assailant was concerned. 22% of men agreed with the myth that men are to blame for their assault if they did not retaliate against a male perpetrator, however, this percentage increased to 44% when the perpetrator was female, and, 1 in 5 men believed that it is impossible for a man to be raped, regardless of the assailant’s gender (Struckman-Johnson & Struckman-Johnson, 1992).

In an additional study by Chapleau et al. (2008) similar results arose. It was however detected that rape myth acceptance for a small number of myths was significantly lower than in the previous study; most notably, the myth that men cannot be raped. It has been argued that this myth rejection may be a result of the increased awareness male rape and sexual assault has received in legislation, in the media, and through educational and organisational support charities (Turchik & Edwards, 2012). Yet, as male victimisation has only relatively recently gained recognition in society, it is not surprising that there has not been any considerable change in the statistics since the previous study was undertaken.

Chapleau et al. (2008) also analysed the relationship between ambivalent sexist attitudes towards men and rape myth acceptance. Ambivalent sexism is the ideology that sexism is composed of both ‘hostile’ and ‘benevolent’ prejudices. Hostile sexism can reflect attitudes such as: men can exploit women for sex and power, whereas, benevolent sexism can reflect attitudes that may be classed as subjectively positive, but in fact are harmful to others, such as: men are invulnerable and stoic (Davies et al., 2012). The authors found that hostile sexism did not have any relevance or association with the acceptance of male rape myths, whereas benevolent sexism was a significant factor. By examining the same rape myths as in the Struckman-Johnson and Struckman-Johnson (1992) study, they found that females who held benevolent sexist notions towards men accepted all three rape myths. Yet, for males, benevolent sexism was only associated with the acceptance of the myth that men are to blame for their assault. It was believed that a male victim must have shown cowardice and weakness to allow the attack to occur (Chapleau et al., 2008). These results are also reflected in a more recent study by Walfield (2018).

Although these studies provide support that gender role socialisations are an influential factor in rape myth acceptance, the results need to be interpreted with caution. The participants utilised in both studies were solely undergraduate university students, and although assessing the attitudes of the younger generation is necessary, as they are at an increased risk of sexual victimisation, the results cannot be generalisable to other members of the population (Walfield, 2012). These studies were also conducted in similar locations in the United States of America, therefore, the samples used are homogeneous, and the data for rape myth acceptance cannot be generalisable to other countries (Pearson & Barker, 2018). Nevertheless, the study by Davies et al. (2012), one of the only studies on rape myth acceptance conducted in the United Kingdom, revealed that the traditional values of the British culture does not differ greatly from the values identified in the American culture.

Consistent with the previous results, Davies et al. (2012) has shown that although rape myth acceptance regarding male victims has decreased, they are still prevalent in society. It was identified that male participants endorsed these myths on a higher level than female participants, particularly when the victim was homosexual. In contrast to previous research, males displayed more hostile sexism towards male victims, and believed that gender roles ought not to be transcended (Davies et al., 2012). Female participants, however, still displayed negative attitudes towards victims, endorsing the same benevolent sexism as their male counterparts. Specifically, accepting stereotypical views about male invulnerability and male dominance. As previous research has also recognised, male participants revealed more victim-blaming attitudes towards men, than female participants, and considered the rape or sexual assault of a homosexual man to be less severe and traumatic, compared with a heterosexual man, and therefore taken less seriously. It can be further noted that within each of these three studies, individuals did not accept male or female victim rape myths any more than the other (Davies et al., 2012).

Collectively these studies suggest that although the acceptance of male rape myths are declining, they still prevail within society. It has been highlighted that holding traditional views regarding masculinity and gender roles, and rape myth adherence, correlate strongly. The acceptance of any one of the rape myths can be detrimental to a victim, as they receive less compassion, and thus, are attributed more blame for the offence (Chapleau et al., 2008; Davies et al., 2012). Male victimisation is progressively becoming recognised as a serious issue within society, and as there is a limited amount of research on male rape myth acceptance, with the latter study being conducted 8 years ago, there is considerable scope for more examination to be done in this area. Increasing knowledge and publicity of male rape myths will ensure these misrepresentations decrease. One of the myths surrounding male rape is that it only occurs in prison institutions. As prison rape has been largely overlooked in the UK, it suggests that rape in this context is acceptable behaviour. It is therefore important to assess the reasons for this lack of attention and lack of research.

6 The Reasons Rape in Prison Institutions is Under Researched

As there has been a scarcity of research undertaken, the nature, scale and prevalence of male rape and sexual assault in prison institutions in the United Kingdom is unknown. Male rape in this context was not considered to be a serious issue until relatively recently, and the only independent review to ever be conducted on coercive sex in prison was by the Howard League for Penal Reform in 2014.

This review revealed that between the years 2007 and 2012 the Prisons and Probation Ombudsman received 108 complaints of unwanted sexual occurrence across prison establishments within the UK, with only 47 cases being eligible for investigation. The data obtained by the Ministry of Justice also shows that there were 113 recorded sexual assaults in 2012, which increased to 169 in 2013 (Howard League for Penal Reform, 2014). Although this data may suggest that sexual offences are rising, or more prisoners are being encouraged to report their victimisation to prison officials, these statistics need to be viewed with caution.

Sexual violence within prison is a concealed issue, and it is believed to be a more under-reported crime than in the wider community (Abdullah-Khan, 2008). Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons disseminated surveys to a sample of male inmates to discover whether, during their time in incarceration, they had been sexually assaulted by another prisoner or by any of the prison staff. The results revealed that 1 percent of prisoners, across the most secure categories of prisons, had experienced some form of sexual abuse whilst in incarceration (Howard League for Penal Reform, 2014). Considering that there are approximately 83,000 individuals currently residing in prisons across the UK, this percentage can infer that 830 inmates are currently victims of sexual violence (Howard League for Penal Reform, 2020), however, the actual prevalence figures are unknown.

Although it is important to investigate the hegemonic masculine ideology of male prisoners, and the issues that surround male perpetrators and victims of rape in prison institutions, the reason rape and sexual assault is under researched is a more prevailing issue. It has been argued that the reluctance of male prisoners to disclose or report their sexual victimisation is one reason research into this matter is absent (Javaid, 2018). Male victims in prison experience the same barriers as male victims in the wider community; the consequences of rape myth acceptance, succumbing to the effects of losing the hegemonic normative roles, and victim-blaming attitudes, amongst others. In incarcerated settings, however, additional barriers to reporting are present (Fowler et al., 2010). Sykes (1958) proclaims that when inmates arrive in prison, they suffer certain deprivations, such as: liberty, autonomy, heterosexual relationships, goods and services, and, security. As a result, men form their own subculture which includes its own values, roles, inmate codes and argot, and it is also deemed to be high in hyper-masculinity, heterosexism and homosexuality. Hyper-masculinity in prison equates to having a high-status, self-worth and a diminished danger of victimisation (Fowler et al., 2010). The most relevant factor of this prison culture to explain underreporting, however, is the inmate code and the proscription against ‘snitching’. Inmates value loyalty and it has been documented that if a prisoner reports their victimisation to a prison official and ‘snitches’ on the perpetrator it will be met with hostility. Fear of stigmatising labels, retaliation, ridicule, and repercussions from other inmates, or, disbelief and an unsympathetic response from the prison guards will therefore refrain victims from reporting (Struckman-Johnson & Struckman-Johnson, 2006; Fowler et al., 2010). Thus, non-disclosure of sexual offences will ensure that this issue stays hidden. Prison authorities are likely aware of these issues in their establishments, and regardless of their attempts to keep them concealed, research has consistently shown that male rape does occur (Abdullah-Khan, 2008).

Politicisation of male sexual misconduct in prison may be another reason research in this area is lacking. It has been argued that the main issue is that politicians deny or fail to recognise that this is an issue (O’Donnell, 2004). An illustration of this can be Chris Grayling, the former Secretary of State for Justice, who would not grant permission for research to be conducted by the Howard League for Penal Reform, into sexual coercion in prison (Fogg, 2014). Under his tenure, researchers were forbidden to approach any prison staff, prison governors, serving prisoners, or any individuals out on licence. If any volunteering prisoner or parolee did provide evidence, it could be viewed as a breach of their conditions, and they may be reprimanded or recalled back to prison (Fogg, 2014). The true reason for this refusal is unknown, however, it has been viewed that a ‘see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil’ demeanour has been instilled into the governmental department that is accountable for the nation’s prisons (Neilson, 2014).

Males within the hegemonic domain can be in positions of power within society, such as politicians and editors within the media, and these positions can be utilised to oppress those individuals who do not uphold or conform to the hegemonic ideals. It could therefore be suggested that if the elite class uphold the hegemonic masculine ideologies in society, or hold negative or homophobic views towards homosexual men, then this may influence political notions, policies, media depictions, and effective research (Pretorius, 2009). It has further been claimed that the silence surrounding male rape, is because society is living in a rapist culture. Du Toit (2005) as quoted in Pretorius (2009:577) states a rapist culture ‘effectively negates the existence of rape and its consequences, so effectively in fact, that the issue of rape is consistently denied political visibility.’ Maintaining this silence perpetuates the rape myth that men are capable of committing the act of rape, but they are not vulnerable enough to be the victims of rape. There is therefore an extensive need for research to be undertaken in prisons across the United Kingdom to establish the prevalence, nature, and issues of male rape in institutions. Nevertheless, until male sexual victimisation is added into the political agenda, and prison authorities admit and insist that a problem does exist, effective research will not be executed, and the silence around male sexual misconduct in prison will persist (Pretorius, 2009; Javaid, 2018).

7 Conclusion

Despite the reformation of the law in 1994, where it became a recognised legal offence for a man to non-consensually anally penetrate another man, the literature presented indicates that male rape and sexual victimisation are still extremely under-reported and under-represented issues in society. In recent years, however, male rape, sexual assault, and male sexual victimisation have started to receive increasing amounts of attention, in both academic literature and in the public domain; particularly in the media.

The media has an influential impact on societal perceptions, and the way the different media formats portray male rape and sexual assault does not only influence society’s understanding of these crimes and who are credible victims, it also has a powerful impact upon the victims themselves. These depictions can affect a victim’s response to the crime, their self-worth and self-perception, and, how they understand their experience and contend with their victimisation (Turchik & Edwards, 2012). It has been illustrated that media representations of male rape do deviate considerably from the reality of male rape, and the sensationalist reporting in newsprint, and the mis-representation of this offence in film, are main contributors to the rape myths ingrained in society (Abdullah-Khan, 2008; Levan et al., 2011; Pitfield, 2013).

Nevertheless, media outlets are starting to show more realistic portrayals and fewer stereotypes of male sexual victimisation, treating this topic with greater sensitivity, particularly through the utilisation of documentaries and soap operas. However, more representations on female perpetrator male victim attacks are required, as there is a minimal amount of portrayals of this, and where it does exist, it is treated facetiously. Regardless of the media starting to dispel rape myths, it has been highlighted through research studies that rape myths are still widely accepted in society, and unless drastic change occurs, these myths are likely to persist (Chapleau et al., 2008; Davies et al., 2012).

Male rape myth acceptance is strongly associated with the traditional views of hegemonic masculinity and gender role socialisations; thus, the extent individuals adhere to these myths will depend on how hegemonic society is. The United Kingdom has a capitalistic society, and the media can be viewed as acting in the interest of the bourgeoisie; the elite class (Newburn, 2017). It can therefore be suggested that if the elite class uphold these hegemonic ideals, they are in positions of power to promote these ideologies upon the rest of society, defining it as the acceptable norm. These ideals may also be accentuated through legislation and political policies (Pretorius, 2009). This can be demonstrated by the politicisation of the issue of male rape with the prison system.

The acceptance of any one of these rape myths can be detrimental to a victim, as heterosexist and homophobic attitudes will transpire, and victims may be attributed more blame for the offence. It is therefore important for future research to discover ways in which these myths and stigmatising views can be eradicated to ensure awareness around male sexual victimisation is raised, victims are encourage to disclose their incident, and seek the support and justice they deserve, and to ensure this topic is no longer an unspoken phenomenon.

Future Research

In the United Kingdom, Abdullah-Khan’s (2008) study on the representations of male rape in the newsprint media, is the only study currently in existence. As this study was undertaken 12 years ago, and focused on newspaper articles between the years of 1989 and 2002, further research in this area is urgently required. Since these dates the collective attitudes in society may have reformed, particularly in the wake of the MeToo movement, and practices within news production and news stories may have improved.

Until relatively recently, there has been a lack of realistic imagery in the media on male rape. What is now needed is further research into how the more recent portrayals of male rape in entertainment, such as in drama programmes and soap operas have impacted the attitudes of society, the attitudes of the victims, and to explore whether male rape myth acceptance is declining. There is a limited amount of research on rape myth acceptance for male victims, with the most recent study based in the United Kingdom conducted in 2012. As the studies in existence have primarily utilised undergraduate students as participants, there is considerable scope for more examination to be done on other members of the population, with varying demographic characteristics and backgrounds.

Abdullah-Khan, N. (2008) Male Rape: The Emergence of a Social and Legal Issue . Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bufkin, J. & Eschholz, S. (2000) Images of Sex and Rape: A Content Analysis of Popular Film. Violence Against Women, 6(12), 1317-1344

Chapleau, K. M., Oswald, D. L. & Russell, B. L. (2008) Male Rape Myths: The Role of Gender, Violence, and Sexism. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23(5), 600-615.

Coronation Street (2018) Directed by Vicky Thomas. Written by Jonathan Harvey [TV Programme]. ITV, March, 20:30.

Crossman, A. (2019) The Pros and Cons of Secondary Data Analysis . Available online: https://www.thoughtco.com/secondary-data-analysis-3026536 [Accessed 03/03/2020].

Davies, M., Gilston, J. & Rogers, P. (2012) Examining the Relationship Between Male Rape Myth Acceptance, Female Rape Myth Acceptance, Victim Blame, Homophobia, Gender Roles, and Ambivalent Sexism. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(14), 2807-2823.

Dunn, P. (2012) Men as Victims: ‘Victim’ Identities, Gay Identities, and Masculinities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(17), 3442-3467.

Eigenberg, H. & Baro, A. (2003) If You Drop the Soap in the Shower You Are on Your Own: Images of Male Rape in Selected Prison Movies. Sexuality & Culture: An Interdisciplinary Quarterly, 7(4), 56-89.

Elliott, C. & Quinn, F. (2008) Criminal Law , 7 th Edition. New York: Pearson Longman.

Fisher, N. L. & Pina, A. (2012) An Overview of the Literature on Female-Perpetrated Adult Male Sexual Victimisation. Aggression and Violent Behaviour, 18(1), 54-61.

Fogg, A. (2014) Why is Chris Grayling Blocking Research into Rape in Prison? Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/may/06/chris-grayling-blocking-research-rape-prison-sexual-assault-jail [Accessed 01/03/2020].

Fowler, S. K., Blackburn, A. G., Marquart, J. W. & Mullings, J. L. (2010) Would They Officially Report an In-Prison Sexual Assault? An Examination of Inmate Perceptions. The Prison Journal, 90(2), 220-243.

Greer, C. (2003) Sex Crime and the Media: Sex Offending and the Press in a Divided Society. Devon: Willan Publishing.

Henderson, T. (2019) Why Does Film and TV Treat Men’s Sexual Assault Like a Punchline? Available online: https://www.pride.com/tv/2019/2/11/why-does-film-tv-treat-mens-sexual-assault-punchline [Accessed 25/01/2020].

HM Government (2019) Position Statement on Male Victims of Crimes Considered in the Cross-Government Strategy on Ending Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG). London. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/783996/Male_Victims_Position_Paper_Web_Accessible.pdf [Accessed 28/01/2020].

Hollyoaks (2014) Directed by Matt Holt. Written by Jessica Lea [TV Programme]. Channel 4, January, 18:30.

Javaid, A. (2014) Male Rape: The ‘Invisible’ Male. Internet Journal of Criminology, January, 1-49.

Javaid, A. (2015) Male Rape Myths: Understanding and Explaining Social Attitudes Surrounding Male Rape. Masculinities and Social Change, 4(3), 270-294.

Javaid, A. (2016) Feminism, Masculinity and Male Rape: Bringing Male Rape ‘Out of the Closet’. Journal of Gender Studies, 25(3), 283-293.

Javaid, A. (2018) Male Rape, Masculinities, and Sexualities: Understanding, Policing, and Overcoming Male Sexual Victimisation. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jewkes, R., Morrell, R., Hearn, J., Lundqvist, E., Blackbeard, D., Lindegger, G., Quayle, M., Sikweyiya, Y. & Gottzen, L. (2015) Hegemonic Masculinity: Combining Theory and Practice in Gender Interventions. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 17(2), 112-127.

Jewkes, Y. (2015) Media and Crime, Third Edition. London: SAGE Publications.

Kassing, L. R., Beesley, D. & Frey, L. L. (2005) Gender Role Conflict, Homophobia, Age, and Education as Predictors of Male Rape Myth Acceptance. Journal of Mental Health Counselling, 27(4), 311-328.

Levan, K., Polzer, K. & Downing, S. (2011) Media and Prison Sexual Assault: How We Got to the ‘Don’t Drop the Soap’ Culture. International Journal of Criminology and Sociological Theory, 4(2), 647-682.

Lowe, M. & Rogers, P. (2017) The Scope of Male Rape: A Selective Review of Research, Policy and Practice. Aggression and Violent Behaviour , 35, 38-43.

Male Rape: Breaking the Silence (2017) [TV Programme] BBC1 Scotland. Available online: https://learningonscreen.ac.uk/ondemand/index.php/prog/104A1E41?bcast=125759530 Accessed [18/12/2019].

McKeever, N. (2018) Can a Woman Rape a Man and Why Does It Matter? Criminal Law and Philosophy, 13, 599-619.

Mezey, G. & King, M. (1989) The Effects of Sexual Assault on Men: A Survey of 22 Victims. Psychological Medicine, 19(1), 205-209.

Ministry of Justice. (2014) £500,000 to Help Break the Silence for Male Rape Victims. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/500000-to-help-break-the-silence-for-male-rape-victims [Accessed 01/02/2020].

Morgan, A. (2019) Importance of Being Brave: How Putting Male Rape Stories on TV has Fuelled a Surge in Reporting. Available online: https://www.staybrave.org.uk/single-post/2019/04/29/Importance-of-being-Brave-how-putting-Male-rape-stories-on-TV-has-fueled-a-surge-in-reporting [Accessed 25/01/2020].

Naylor, B. (2001) Reporting Violence in the British Print Media: Gendered Stories. The Howard Journal, 40(2), 180-194.

Neilson, A. (2014) Why Does the US Take Rape in Prison More Seriously than England and Wales? Available online: https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/2014/09/why-does-us-take-rape-prison-more-seriously-england-and-wales [Accessed 01/03/2020].

Newburn, T. (2017) Criminology, Third Edition. Oxon: Routledge.

Ng, S. (2014) The Last Taboo: Male Rape and the Effectiveness of Existing Legislation in Afghanistan, Great Britain, and the United States. Tulane Journal of International and Comparative Law, 23(1), 227-250.

O’Donnell, I. (2004) Prison Rape in Context. The British Journal of Criminology, 44(2), 241-255.

Office for National Statistics. (2018) Sex Offences in England and Wales: Year Ending March 2017 . Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/crimeandjustice/articles/sexualoffencesinenglandandwales/yearendingmarch2017 [Accessed 02/03/2020].

Pearson, J. & Barker, D. (2018) Male Rape: What We Know, Don’t Know and Need to Find Out – A Critical Review. Crime Psychology Review , 4(1), 72-94.

Petersson, C. C. & Plantin, L. (2019) Breaking with Norms of Masculinity: Men Making Sense of Their Experience of Sexual Assault. Clinical Social Work Journal, 47, 372-383.

Petrak, J. (2002) Rape: History, Myths and Reality. In Petrak, J. & Hedge, B. (eds) The Trauma of Sexual Assault: Treatment, Prevention and Practice. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 1-18.

Pitfield, C. (2013) Male Survivors of Sexual Assault: To tell or not to tell? Available online: https://repository.uel.ac.uk/download/7114928707ffdc81db2b052b20765be5b5c8eae24c2bca074e79f9a60966ce67/3605459/2013_DClinPsych_Pitfield.pdf [Accessed 18/01/2020].

Pollak, J. M. & Kubrin, C. E. (2007) Crime in the News: How Crimes, Offenders and Victims Are Portrayed in the Media. Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture, 14(1), 59-83.

Pretorius, G. (2009) The Male Rape Survivor: Possible Meanings in the Context of Feminism and Patriarchy. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 19(4), 575-580.

Roberts, M. (2013) When a Man is Raped [Booklet]. NSW Health Education Centre Against Violence.

Sacco, V. F. (1995) Media Constructions of Crime. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, May, 141-154.

Struckman-Johnson, C. & Struckman-Johnson, D. (1992) Acceptance of Male Rape Myths Among College Men and Women. Sex Roles, 27(3), 85-100.

Struckman-Johnson, C. & Struckman-Johnson, D. (2006) A Comparison of Sexual Coercion Experiences Reported by Men and Women in Prison. Journal of Interpersonal Violence , 21(12), 1591-1615.

Survivors Manchester. (2020) Campaigning. Available online: https://www.survivorsmanchester.org.uk/breakthesilence/campaigning/ [Accessed 18/01/2020].

Thacker, L. K. (2017) Rape Culture, Victim Blaming, and the Role of the Media in the Criminal Justice System. Kentucky Journal of Undergraduate Scholarship, 1(1), 89-99.

The Howard League for Penal Reform. (2014) Commission on Sex in Prison: Coercive Sex in Prison – Briefing Paper 3. Available online: https://howardleague.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Coercive-sex-in-prison.pdf [Accessed 01/03/2020].

The Howard League for Penal Reform. (2020) Prison Watch. Available online: https://howardleague.org/prisons-information/prison-watch/ [Accessed 01/03/2020].

Turchik, J. A. & Edwards, K. M. (2012) Myths About Male Rape: A Literature Review. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 13(2), 211-226.

Walfield, S. M. (2018) Men Cannot Be Raped: Correlates of Male Rape Myth Acceptance. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, December, 1-27

Walker, J., Archer, J. & Davies, M. (2005) Effects of Rape on Men: A Descriptive Analysis. Archives of Sexual Behaviour , 34(1), 69-80.

Weiss, K. G. (2010) Male Sexual Victimisation: Examining Men’s Experiences of Rape and Sexual Assault. Men and Masculinities, 12(3), 275-298.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Male Victims of Sexual Abuse: Impact and Resilience Processes, a Qualitative Study

Léa poirson, marion robin, gérard shadili, josianne lamothe, emmanuelle corruble, florence gressier, aziz essadek.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence: [email protected] ; Tel.: +33-372-743-058

Received 2023 Mar 24; Revised 2023 Jun 19; Accepted 2023 Jun 22; Collection date 2023 Jul.

Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ).

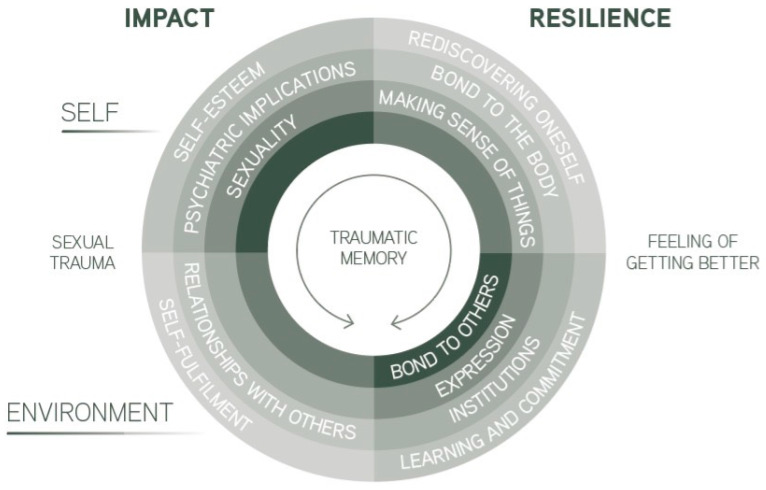

The increasing prevalence of sexual abuse calls for exceptional awareness of its multidimensional impact on the mental, sexual, and social wellbeing of male adults. This study aims to deepen the overall understanding of sexual abuse consequences; to highlight some common resilience factors; and to strengthen therapeutic and social support. In this qualitative research, we conducted seven semi-structured interviews with male victims of sexual violence. The data were analysed with the interpretative phenomenological analysis. They shed light on the great suffering linked to sexual violence, and on seven themes which are seemingly pillars of resilience: bond to others, bond to the body, making sense of things, expression, rediscovering oneself, institutions, and finally, learning and commitment. The exploration of these themes reveals several avenues for adjusting care, most of which imply the importance of raising awareness so that spaces receiving the victims’ word can emerge.

Keywords: male victims, sexual abuse, impact, resilience

1. Introduction

The literature shows varying prevalence rates of male sexual abuse, with a tendency toward increase [ 1 ]. In the United States of America, the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS) of 2017 indicated that 30.7% of men report having been victims of sexual violence [ 2 ]. Moreover, 16% of male victims would be sexually abused before the age of sixteen [ 3 ]. In a recent study including children and adolescents from Barbados and Grenada, the rates of sexual abuse outside and within the family were higher for boys than girls [ 4 ]. As for Asia, the estimated prevalence of childhood sexual abuse (CSA) among boys ranged from 1.7% to 49.5% [ 5 ]. On a worldwide scale, it would range from 3% to 17% [ 6 ]. Despite a significant prevalence, it is possible that male sexual abuse remains highly underestimated, as few men report sexual abuse.

Considering the growing prevalence of male sexual abuse, it is important to investigate its impact on individuals and how they might overcome its negative sequelae. The traumatic impact of sexual abuse seems to be expressed in the context of traumatic dynamics relating to sexuality, interrelationships, powerlessness, and stigmatisation [ 7 ]. Emotions tied to sexual trauma can lead to conflicts with identity, as well as masculine norms and stereotypes [ 8 ]. Those would include aggression, rejection of “feminine” characteristics, stoicism, preoccupation with sex, being an economic provider, and being the protector of the home and family [ 3 , 8 ].

Easton et al. [ 9 ] estimate that it takes an average of twenty years for a man to talk about his history of sexual abuse, due to the stigma induced by current norms of masculinity [ 10 ]. This prevents the creation of intimacy [ 8 ]. Hudspith et al. [ 11 ] add that rape myths may generate feelings of self-blame and shame, which discourage victims, male and female alike, from revealing the abuse. Amongst common gender-based rape myths, one reads “only gay men are raped; heterosexual men are not” [ 12 ]. Such false beliefs reinforce secrecy, as well as the stigma induced by norms of masculinity.

Some cultural or religious groups amplify secrecy [ 13 , 14 ]. Findings of a study investigating childhood sexual abuse within German catholic churches indicated that 62% of children were male [ 13 ]. In most cases, the relocation of perpetrators hinders the disclosure of sexual abuse and its future prevention [ 13 ]. Similarly, a study conducted within the Haredi community suggested that the taboo surrounding sexuality, the fear of sinning, as well as the valorisation of obedience, induced lesser tendencies for individuals, families, and peers to reveal the abuse [ 14 ]. Some customs, such as child marriage or child genital mutilation, also put children at risk [ 15 ]. Although sexual abuse within religious groups often results in feelings of worthlessness, mistrust, or spiritual struggles, faith may support resilience by providing hope [ 16 ].

Regardless of religious background, studies show that the sense of stigma is stronger when the perpetrator was a mother or a woman, as unconsciously, men tend to be more often associated with the status of being the perpetrator of sexual abuse [ 10 , 17 ]. The mistaken belief that women cannot be offenders can discourage recognising an experience as abusive if it involves a woman or a mother [ 10 ]. In a study focusing on men who were forced to penetrate women, Weare [ 18 ] shows that this form of female-to-male sexual abuse often results in anxiety, depressive and/or suicidal thoughts, self-harm behaviours, mistrust, and negative feelings of anger, shame, and isolation. Being subjected to penetration would also worsen the sense of stigma and feelings of shame [ 3 ].

Feelings of powerlessness and loss of control, reported by many male victims, seem to be thought of as being a consequence of male gender socialisation [ 3 , 9 , 17 ]. Feelings of powerlessness would result from a man’s recollection of being defenceless and would pervade the emotional and relational aspects of his adult life, during which he may feel unable to succeed or to overcome the challenges he struggles with [ 17 ]. Additionally, traumatic memory, sometimes referred to as “flashbacks”, seems to focus on bits of the traumatic event and is often unexpected [ 19 ]. Thus, traumatic memory might worsen the overall feeling of hurt and losing control, hence the defensive use of avoidance strategies [ 19 ]. Traumatic memory figures among numerous symptoms of PTSD, along with persistent stress responses, hyperarousal, dysphoric mood, and circadian rhythm dysregulation [ 20 ], and increases the risk of psychoactive substance use and suicidality.

Male victims may also experience great fear in facing contact or aggression from others. Some would tend to defend themselves through the embodiment of a hypermasculine and controlling personality [ 9 , 17 , 21 ]. Following sexual abuse, many of them show disturbances in identity construction and socialisation, as well as in their sexual identity development [ 8 ].