Action Research: Steps, Benefits, and Tips

Introduction

History of action research, what is the definition of action research, types of action research, conducting action research.

Action research is an approach to qualitative inquiry in social science research that involves the search for practical solutions to everyday issues. Rooted in real-world problems, it seeks not just to understand but also to act, bringing about positive change in specific contexts. Often distinguished by its collaborative nature, the action research process goes beyond traditional research paradigms by emphasizing the involvement of those being studied in resolving social conflicts and effecting positive change.

The value of action research lies not just in its outcomes, but also in the process itself, where stakeholders become active participants rather than mere subjects. In this article, we'll examine action research in depth, shedding light on its history, principles, and types of action research.

Tracing its roots back to the mid-20th century, Kurt Lewin developed classical action research as a response to traditional research methods in the social sciences that often sidelined the very communities they studied. Proponents of action research championed the idea that research should not just be an observational exercise but an actionable one that involves devising practical solutions. Advocates believed in the idea of research leading to immediate social action, emphasizing the importance of involving the community in the process.

Applications for action research

Over the years, action research has evolved and diversified. From its early applications in social psychology and organizational development, it has branched out into various fields such as education, healthcare, and community development, informing questions around improving schools, minority problems, and more. This growth wasn't just in application, but also in its methodologies.

How is action research different?

Like all research methodologies, effective action research generates knowledge. However, action research stands apart in its commitment to instigate tangible change. Traditional research often places emphasis on passive observation , employing data collection methods primarily to contribute to broader theoretical frameworks . In contrast, action research is inherently proactive, intertwining the acts of observing and acting.

The primary goal isn't just to understand a problem but to solve or alleviate it. Action researchers partner closely with communities, ensuring that the research process directly benefits those involved. This collaboration often leads to immediate interventions, tweaks, or solutions applied in real-time, marking a departure from other forms of research that might wait until the end of a study to make recommendations.

This proactive, change-driven nature makes action research particularly impactful in settings where immediate change is not just beneficial but essential.

Action research is best understood as a systematic approach to cooperative inquiry. Unlike traditional research methodologies that might primarily focus on generating knowledge, action research emphasizes producing actionable solutions for pressing real-world challenges.

This form of research undertakes a cyclic and reflective journey, typically cycling through stages of planning , acting, observing, and reflecting. A defining characteristic of action research is the collaborative spirit it embodies, often dissolving the rigid distinction between the researcher and the researched, leading to mutual learning and shared outcomes.

Advantages of action research

One of the foremost benefits of action research is the immediacy of its application. Since the research is embedded within real-world issues, any findings or solutions derived can often be integrated straightaway, catalyzing prompt improvements within the concerned community or organization. This immediacy is coupled with the empowering nature of the methodology. Participants aren't mere subjects; they actively shape the research process, giving them a tangible sense of ownership over both the research journey and its eventual outcomes.

Moreover, the inherent adaptability of action research allows researchers to tweak their approaches responsively based on live feedback. This ensures the research remains rooted in the evolving context, capturing the nuances of the situation and making any necessary adjustments. Lastly, this form of research tends to offer a comprehensive understanding of the issue at hand, harmonizing socially constructed theoretical knowledge with hands-on insights, leading to a richer, more textured understanding.

Disadvantages of action research

Like any methodology, action research isn't devoid of challenges. Its iterative nature, while beneficial, can extend timelines. Researchers might find themselves engaged in multiple cycles of observation, reflection, and action before arriving at a satisfactory conclusion. The intimate involvement of the researcher with the research participants , although crucial for collaboration, opens doors to potential conflicts. Through collaborative problem solving, disagreements can lead to richer and more nuanced solutions, but it can take considerable time and effort.

Another limitation stems from its focus on a specific context: results derived from a particular action research project might not always resonate or be applicable in a different context or with a different group. Lastly, the depth of collaboration this methodology demands means all stakeholders need to be deeply invested, and such a level of commitment might not always be feasible.

Examples of action research

To illustrate, let's consider a few scenarios. Imagine a classroom where a teacher observes dwindling student participation. Instead of sticking to conventional methods, the teacher experiments with introducing group-based activities. As the outcomes unfold, the teacher continually refines the approach based on student feedback, eventually leading to a teaching strategy that rejuvenates student engagement.

In a healthcare context, hospital staff who recognize growing patient anxiety related to certain procedures might innovate by introducing a new patient-informing protocol. As they study the effects of this change, they could, through iterations, sculpt a procedure that diminishes patient anxiety.

Similarly, in the realm of community development, a community grappling with the absence of child-friendly public spaces might collaborate with local authorities to conceptualize a park. As they monitor its utilization and societal impact, continual feedback could refine the park's infrastructure and design.

Contemporary action research, while grounded in the core principles of collaboration, reflection, and change, has seen various adaptations tailored to the specific needs of different contexts and fields. These adaptations have led to the emergence of distinct types of action research, each with its unique emphasis and approach.

Collaborative action research

Collaborative action research emphasizes the joint efforts of professionals, often from the same field, working together to address common concerns or challenges. In this approach, there's a strong emphasis on shared responsibility, mutual respect, and co-learning. For example, a group of classroom teachers might collaboratively investigate methods to improve student literacy, pooling their expertise and resources to devise, implement, and refine strategies for improving teaching.

Participatory action research

Participatory action research (PAR) goes a step further in dissolving the barriers between the researcher and the researched. It actively involves community members or stakeholders not just as participants, but as equal partners in the entire research process. PAR is deeply democratic and seeks to empower participants, fostering a sense of agency and ownership. For instance, a participatory research project might involve local residents in studying and addressing community health concerns, ensuring that the research process and outcomes are both informed by and beneficial to the community itself.

Educational action research

Educational action research is tailored specifically to practical educational contexts. Here, educators take on the dual role of teacher and researcher, seeking to improve teaching practices, curricula, classroom dynamics, or educational evaluation. This type of research is cyclical, with educators implementing changes, observing outcomes, and reflecting on results to continually enhance the educational experience. An example might be a teacher studying the impact of technology integration in her classroom, adjusting strategies based on student feedback and learning outcomes.

Community-based action research

Another noteworthy type is community-based action research, which focuses primarily on community development and well-being. Rooted in the principles of social justice, this approach emphasizes the collective power of community members to identify, study, and address their challenges. It's particularly powerful in grassroots movements and local development projects where community insights and collaboration drive meaningful, sustainable change.

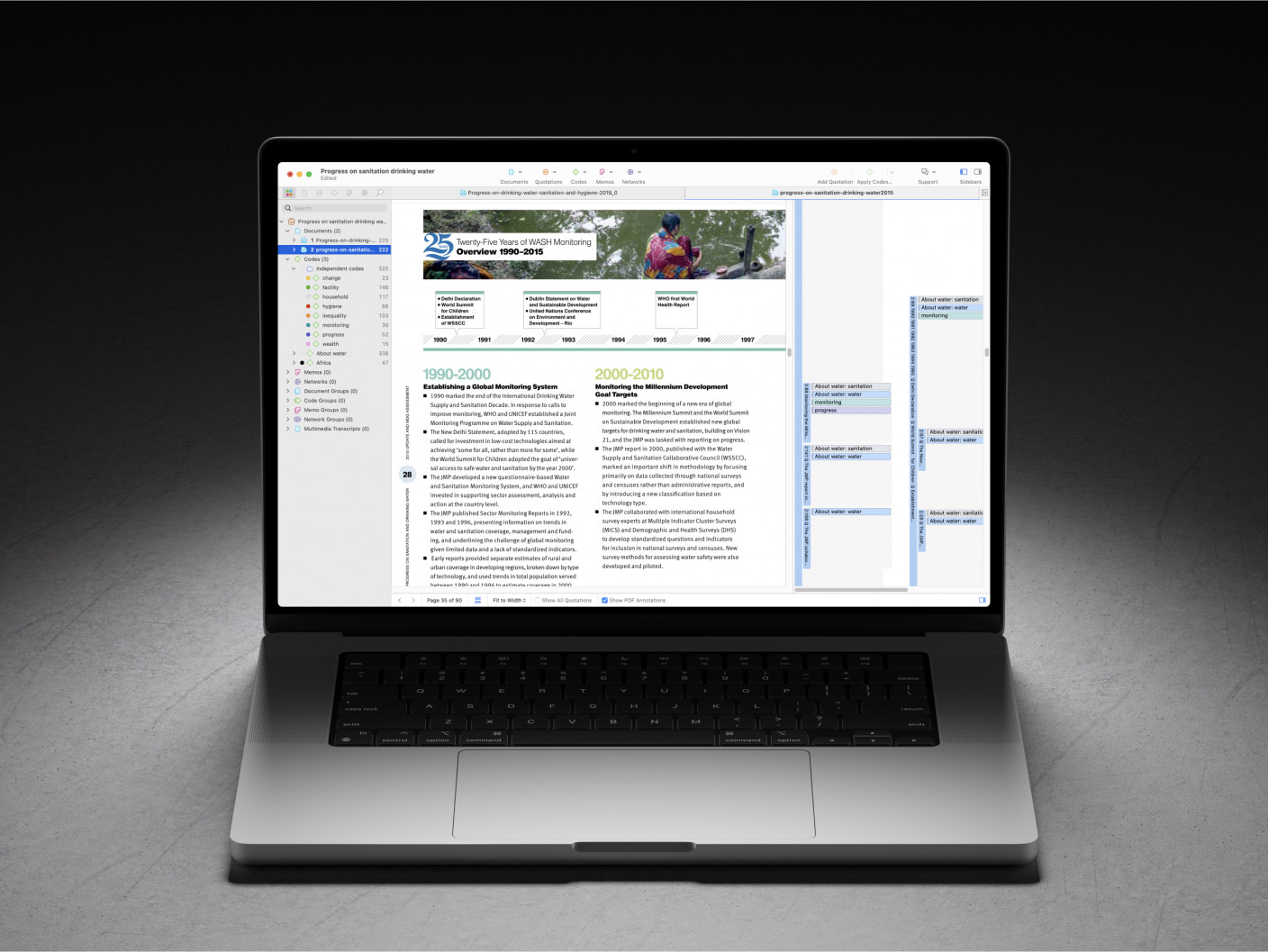

Key insights and critical reflection through research with ATLAS.ti

Organize all your data analysis and insights with our powerful interface. Download a free trial today.

Engaging in action research is both an enlightening and transformative journey, rooted in practicality yet deeply connected to theory. For those embarking on this path, understanding the essentials of an action research study and the significance of a research cycle is paramount.

Understanding the action research cycle

At the heart of action research is its cycle, a structured yet adaptable framework guiding the research. This cycle embodies the iterative nature of action research, emphasizing that learning and change evolve through repetition and reflection.

The typical stages include:

- Identifying a problem : This is the starting point where the action researcher pinpoints a pressing issue or challenge that demands attention.

- Planning : Here, the researcher devises an action research strategy aimed at addressing the identified problem. In action research, network resources, participant consultation, and the literature review are core components in planning.

- Action : The planned strategies are then implemented in this stage. This 'action' phase is where theoretical knowledge meets practical application.

- Observation : Post-implementation, the researcher observes the outcomes and effects of the action. This stage ensures that the research remains grounded in the real-world context.

- Critical reflection : This part of the cycle involves analyzing the observed results to draw conclusions about their effectiveness and identify areas for improvement.

- Revision : Based on the insights from reflection, the initial plan is revised, marking the beginning of another cycle.

Rigorous research and iteration

It's essential to understand that while action research is deeply practical, it doesn't sacrifice rigor . The cyclical process ensures that the research remains thorough and robust. Each iteration of the cycle in an action research project refines the approach, drawing it closer to an effective solution.

The role of the action researcher

The action researcher stands at the nexus of theory and practice. Not just an observer, the researcher actively engages with the study's participants, collaboratively navigating through the research cycle by conducting interviews, participant observations, and member checking . This close involvement ensures that the study remains relevant, timely, and responsive.

Drawing conclusions and informing theory

As the research progresses through multiple iterations of data collection and data analysis , drawing conclusions becomes an integral aspect. These conclusions, while immediately beneficial in addressing the practical issue at hand, also serve a broader purpose. They inform theory, enriching the academic discourse and providing valuable insights for future research.

Identifying actionable insights

Keep in mind that action research should facilitate implications for professional practice as well as space for systematic inquiry. As you draw conclusions about the knowledge generated from action research, consider how this knowledge can create new forms of solutions to the pressing concern you set out to address.

Collecting data and analyzing data starts with ATLAS.ti

Download a free trial of our intuitive software to make the most of your research.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case AskWhy Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research Research Tools and Apps

Action Research: What it is, Types, Stages & Examples

The best way to get things accomplished is to do it yourself. This statement is utilized in corporations, community projects, and national governments. These organizations are relying on action research to cope with their continuously changing and unstable environments as they function in a more interdependent world.

By engaging in cycles of planning, observation, action, and reflection, action research enables participants to identify challenges, implement solutions, and evaluate outcomes. This approach generates practical knowledge and empowers individuals and organizations to effect meaningful change in their contexts.

In practical educational contexts, this involves using systematic inquiry and reflective practice to address real-world challenges, improve teaching and learning, enhance student engagement, and drive positive changes within the educational system .

What is Action Research?

Action research is a strategy that tries to find realistic solutions to organizations’ difficulties and issues. It is similar to applied research.

Action research refers basically learning by doing. First, a problem is identified, then some actions are taken to address it, then how well the efforts worked are measured, and if the results are not satisfactory, the steps are applied again.

It can be put into three different groups:

- Positivist: This type of research is also called “classical action research.” It considers research a social experiment. This research is used to test theories in the actual world.

- Interpretive: This kind of research is called “contemporary action research.” It thinks that business reality is socially made, and when doing this research , it focuses on the details of local and organizational factors.

- Critical: This action research cycle takes a critical reflection approach to corporate systems and tries to enhance them.

Important Types of Action Research

Here are the main types of action research:

1. Practical Action Research

It focuses on solving specific problems within a local context, often involving teachers or practitioners seeking to improve practices.

2. Participatory Action Research (PAR)

A research process in which people, staff, and activists work together to generate knowledge from a study on an issue that adds value and supports their actions for social change.

3. Critical Action Research

Built to address power and social injustices in light of the Hegemonic Underpinnings, this research facilitates a callback, self-reflection, and thorough societal reformations.

4. Collaborative Action Research

In this form of research, a team of practitioners joins to do project work as part of an overall effort to improve. The work continues into the analysis phase with these same folks across all stages.

5. Reflective Action Research

This kind of research emphasizes individual or group reflection on practices. The key to this model is that it encourages reflective and deliberate practice, thus promoting learning and unfolding within ongoing experiences.

6. Transformative Action Research

This model empowers participants to address issues within their communities related to social justice and transformation.

Each type serves different contexts and goals, contributing to the overall effectiveness of action research.

Stages of Action Research

All research is about learning new things. Collaborative action research contributes knowledge based on investigations in particular and frequently useful circumstances. It starts with identifying a problem. After that, the research process is followed by the below stages:

Stage 1: Plan

For an action research project to go well, the researcher needs to plan it well. After coming up with an educational research topic or question after a research study, the first step is to develop an action plan to guide the research process. The research design aims to address the study’s question. The research strategy outlines what to undertake, when, and how.

Stage 2: Act

The next step is implementing the plan and gathering data. At this point, the researcher must select how to collect and organize research data . The researcher also needs to examine all tools and equipment before collecting data to ensure they are relevant, valid, and comprehensive.

Stage 3: Observe

Data observation is vital to any investigation. The action researcher needs to review the project’s goals and expectations before data observation . This is the final step before drawing conclusions and taking action.

Different kinds of graphs, charts, and networks can be used to represent the data. It assists in making judgments or progressing to the next stage of observing.

Stage 4: Reflect

This step involves applying a prospective solution and observing the results. It’s essential to see if the possible solution found through research can really solve the problem being studied.

The researcher must explore alternative ideas when the action research project’s solutions fail to solve the problem.

The Steps of Conducting Action Research

Action research is a systematic approach researchers, educators, and practitioners use to identify and address problems or challenges within a specific context. It involves a cyclical process of planning, implementing, reflecting, and adjusting actions based on the data collected. Here are the general steps involved in conducting an action research process:

Identify the action research question or problem

1. Identify The Action Research Question or Problem

Clearly define the issue or problem you want to address through your research. It should be specific, actionable, and relevant to your working context.

2. Review Existing Knowledge

Conduct a literature review to understand what research has already been done on the topic. This will help you gain insights, identify gaps, and inform your research design .

3. Plan The Research

Develop a research plan outlining your study’s objectives, methods, data collection tools , and timeline. Determine the scope of your research and the participants or stakeholders involved.

4. Collect Data

Implement your research plan by collecting relevant data. This can involve various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, document analysis, or focus groups . Ensure that your data collection methods align with your research objectives and allow you to gather the necessary information.

5. Analyze The Data

Once you have collected the data, analyze it using appropriate qualitative or quantitative techniques. Look for patterns, themes, or trends in the data that can help you understand the problem better.

6. Reflect on The Findings

Reflect on the analyzed data and interpret the results in the context of your research question. Consider the implications and possible solutions that emerge from the data analysis. This reflection phase is crucial for generating insights and understanding the underlying factors contributing to the problem.

7. Develop an Action Plan

Based on your analysis and reflection, develop an action plan that outlines the steps you will take to address the identified problem. The plan should be specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART goals). Consider involving relevant stakeholders in planning to ensure their buy-in and support.

8. Implement The Action Plan

Put your action plan into practice by implementing the identified strategies or interventions. This may involve making changes to existing practices, introducing new approaches, or testing alternative solutions. Document the implementation process and any modifications made along the way.

9. Evaluate and Monitor Progress

Continuously monitor and evaluate the impact of your actions. Collect additional data, assess the effectiveness of the interventions, and measure progress towards your goals. This evaluation will help you determine if your actions have the desired effects and inform any necessary adjustments.

10. Reflect and Iterate

Reflect on the outcomes of your actions and the evaluation results. Consider what worked well, what did not, and why. Use this information to refine your approach, make necessary adjustments, and plan for the next cycle of action research if needed.

Remember that participatory action research is an iterative process, and multiple cycles may be required to achieve significant improvements or solutions to the identified problem. Each cycle builds on the insights gained from the previous one, fostering continuous learning and improvement.

Explore Insightfully Contextual Inquiry in Qualitative Research

Examples of Action Research

Here are two real-life examples of action research.

Action research initiatives are frequently situation-specific. Still, other researchers can adapt the techniques. The example is from a researcher’s (Franklin, 1994) report about a project encouraging nature tourism in the Caribbean.

In 1991, this was launched to study how nature tourism may be implemented on the four Windward Islands in the Caribbean: St. Lucia, Grenada, Dominica, and St. Vincent.

For environmental protection, a government-led action study determined that the consultation process needs to involve numerous stakeholders, including commercial enterprises.

First, two researchers undertook the study and held search conferences on each island. The search conferences resulted in suggestions and action plans for local community nature tourism sub-projects.

Several islands formed advisory groups and launched national awareness and community projects. Regional project meetings were held to discuss experiences, self-evaluations, and strategies. Creating a documentary about a local initiative helped build community. And the study was a success, leading to a number of changes in the area.

Lau and Hayward (1997) employed action research to analyze Internet-based collaborative work groups.

Over two years, the researchers facilitated three action research problem -solving cycles with 15 teachers, project personnel, and 25 health practitioners from diverse areas. The goal was to see how Internet-based communications might affect their virtual workgroup.

First, expectations were defined, technology was provided, and a bespoke workgroup system was developed. Participants suggested shorter, more dispersed training sessions with project-specific instructions.

The second phase saw the system’s complete deployment. The final cycle witnessed system stability and virtual group formation. The key lesson was that the learning curve was poorly misjudged, with frustrations only marginally met by phone-based technical help. According to the researchers, the absence of high-quality online material about community healthcare was harmful.

Role clarity, connection building, knowledge sharing, resource assistance, and experiential learning are vital for virtual group growth. More study is required on how group support systems might assist groups in engaging with their external environment and boost group members’ learning.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Action Research

Action research has both good and bad points.

- It is very flexible, so researchers can change their analyses to fit their needs and make individual changes.

- It offers a quick and easy way to solve problems that have been going on for a long time instead of complicated, long-term solutions based on complex facts.

- If It is done right, it can be very powerful because it can lead to social change and give people the tools to make that change in ways that are important to their communities.

Disadvantages

- These studies have a hard time being generalized and are hard to repeat because they are so flexible. Because the researcher has the power to draw conclusions, they are often not thought to be theoretically sound.

- Setting up an action study in an ethical way can be hard. People may feel like they have to take part or take part in a certain way.

- It is prone to research errors like selection bias , social desirability bias, and other cognitive biases.

Why QuestionPro Research Suite is Great for Action Research?

QuestionPro Research Suite is an ideal choice for action research, which typically involves multiple rounds of data collection , analysis, and intervention cycles. This is one reason it might be great for that:

01. Data Collection

QuestionPro offers flexible and adaptable methods for data dissemination. You can collect and store crucial business data from secure, personalized questionnaires , and distribute them through emails, SMSs, or even popular social media platforms and mobile apps.

This adaptability is particularly useful for action research, which often requires a variety of data collection techniques.

02. Advanced Analysis Tools

- Efficient Data Analysis: Built-in tools simplify both quantitative and qualitative analysis.

- Powerful Segmentation: Cross-tabulation lets you compare and track changes across cycles.

- Reliable Insights: This robust toolset enhances confidence in research outcomes.

03. Collaboration and Real-Time Reporting

Multiple researchers can collaborate within the platform, sharing permissions and changes in real-time while creating reports. Asynchronous collaboration: Conversation threads and comments can be in one place, ensuring all team members stay updated and are aligned with stakeholders throughout each action research phase.

04. User-Friendly Interface

At the user level, what kind of data visualization charts/graphs, tables, etc., should be provided to visualize the complex findings most often done through these)? Across all solutions, we need fully customizable dashboards to offer perfect vision to different people so they can make decisions and take action based on this data.

05. Automation and Integration Capabilities

- Workflow Automation: Enables recurring surveys or updates to run seamlessly.

- Time Savings: Frees up time in long-term research projects.

- Integrations: Connects with popular CRMs and other applications.

- Simplified Data Addition: This makes incorporating data from external sources easy.

These features make QuestionPro Research Suite a powerful tool for action research. It makes it easy to manage data, conduct analyses, and drive actionable insights through iterative research cycles.

Action research is a dynamic and participatory approach that empowers individuals and communities to address real-world challenges through systematic inquiry and reflection.

The methods used in action research help gather valuable insights and foster continuous improvement, leading to meaningful change across various fields. By promoting iterative cycles, action research generates knowledge and encourages a culture of learning and adaptation, making it a crucial tool for driving transformation.

At QuestionPro, we give researchers tools for collecting data, like our survey software, and a library of insights for any long-term study. Go to the Research Suite if you want to see a demo or learn more about it.

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

Frequently Asked Questions(FAQ’s)

Action research is a systematic approach to inquiry that involves identifying a problem or challenge in a practical context, implementing interventions or changes, collecting and analyzing data, and using the findings to inform decision-making and drive positive change.

Action research can be conducted by various individuals or groups, including teachers, administrators, researchers, and educational practitioners. It is often carried out by those directly involved in the educational setting where the research takes place.

The steps of action research typically include identifying a problem, reviewing relevant literature, designing interventions or changes, collecting and analyzing data, reflecting on findings, and implementing improvements based on the results.

MORE LIKE THIS

Maximize Employee Feedback with QuestionPro Workforce’s Slack Integration

Nov 6, 2024

2024 Presidential Election Polls: Harris vs. Trump

Nov 5, 2024

Your First Question Should Be Anything But, “Is The Car Okay?” — Tuesday CX Thoughts

QuestionPro vs. Qualtrics: Who Offers the Best 360-Degree Feedback Platform for Your Needs?

Nov 4, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

community, pedagogy and informal education

What is action research and how do we do it?

In this article, we explore the development of some different traditions of action research and provide an introductory guide to the literature., contents : what is action research · origins · the decline and rediscovery of action research · undertaking action research · conclusion · further reading · how to cite this article . see, also: research for practice ..

In the literature, discussion of action research tends to fall into two distinctive camps. The British tradition – especially that linked to education – tends to view action research as research-oriented toward the enhancement of direct practice. For example, Carr and Kemmis provide a classic definition:

Action research is simply a form of self-reflective enquiry undertaken by participants in social situations in order to improve the rationality and justice of their own practices, their understanding of these practices, and the situations in which the practices are carried out (Carr and Kemmis 1986: 162).

Many people are drawn to this understanding of action research because it is firmly located in the realm of the practitioner – it is tied to self-reflection. As a way of working it is very close to the notion of reflective practice coined by Donald Schön (1983).

The second tradition, perhaps more widely approached within the social welfare field – and most certainly the broader understanding in the USA is of action research as ‘the systematic collection of information that is designed to bring about social change’ (Bogdan and Biklen 1992: 223). Bogdan and Biklen continue by saying that its practitioners marshal evidence or data to expose unjust practices or environmental dangers and recommend actions for change. In many respects, for them, it is linked into traditions of citizen’s action and community organizing. The practitioner is actively involved in the cause for which the research is conducted. For others, it is such commitment is a necessary part of being a practitioner or member of a community of practice. Thus, various projects designed to enhance practice within youth work, for example, such as the detached work reported on by Goetschius and Tash (1967) could be talked of as action research.

Kurt Lewin is generally credited as the person who coined the term ‘action research’:

The research needed for social practice can best be characterized as research for social management or social engineering. It is a type of action-research, a comparative research on the conditions and effects of various forms of social action, and research leading to social action. Research that produces nothing but books will not suffice (Lewin 1946, reproduced in Lewin 1948: 202-3)

His approach involves a spiral of steps, ‘each of which is composed of a circle of planning, action and fact-finding about the result of the action’ ( ibid. : 206). The basic cycle involves the following:

This is how Lewin describes the initial cycle:

The first step then is to examine the idea carefully in the light of the means available. Frequently more fact-finding about the situation is required. If this first period of planning is successful, two items emerge: namely, “an overall plan” of how to reach the objective and secondly, a decision in regard to the first step of action. Usually this planning has also somewhat modified the original idea. ( ibid. : 205)

The next step is ‘composed of a circle of planning, executing, and reconnaissance or fact-finding for the purpose of evaluating the results of the second step, and preparing the rational basis for planning the third step, and for perhaps modifying again the overall plan’ ( ibid. : 206). What we can see here is an approach to research that is oriented to problem-solving in social and organizational settings, and that has a form that parallels Dewey’s conception of learning from experience.

The approach, as presented, does take a fairly sequential form – and it is open to a literal interpretation. Following it can lead to practice that is ‘correct’ rather than ‘good’ – as we will see. It can also be argued that the model itself places insufficient emphasis on analysis at key points. Elliott (1991: 70), for example, believed that the basic model allows those who use it to assume that the ‘general idea’ can be fixed in advance, ‘that “reconnaissance” is merely fact-finding, and that “implementation” is a fairly straightforward process’. As might be expected there was some questioning as to whether this was ‘real’ research. There were questions around action research’s partisan nature – the fact that it served particular causes.

The decline and rediscovery of action research

Action research did suffer a decline in favour during the 1960s because of its association with radical political activism (Stringer 2007: 9). There were, and are, questions concerning its rigour, and the training of those undertaking it. However, as Bogdan and Biklen (1992: 223) point out, research is a frame of mind – ‘a perspective that people take toward objects and activities’. Once we have satisfied ourselves that the collection of information is systematic and that any interpretations made have a proper regard for satisfying truth claims, then much of the critique aimed at action research disappears. In some of Lewin’s earlier work on action research (e.g. Lewin and Grabbe 1945), there was a tension between providing a rational basis for change through research, and the recognition that individuals are constrained in their ability to change by their cultural and social perceptions, and the systems of which they are a part. Having ‘correct knowledge’ does not of itself lead to change, attention also needs to be paid to the ‘matrix of cultural and psychic forces’ through which the subject is constituted (Winter 1987: 48).

Subsequently, action research has gained a significant foothold both within the realm of community-based, and participatory action research; and as a form of practice-oriented to the improvement of educative encounters (e.g. Carr and Kemmis 1986).

Exhibit 1: Stringer on community-based action research

A fundamental premise of community-based action research is that it commences with an interest in the problems of a group, a community, or an organization. Its purpose is to assist people in extending their understanding of their situation and thus resolving problems that confront them….

Community-based action research is always enacted through an explicit set of social values. In modern, democratic social contexts, it is seen as a process of inquiry that has the following characteristics:

• It is democratic , enabling the participation of all people.

• It is equitable , acknowledging people’s equality of worth.

• It is liberating , providing freedom from oppressive, debilitating conditions.

• It is life enhancing , enabling the expression of people’s full human potential.

(Stringer 1999: 9-10)

Undertaking action research

As Thomas (2017: 154) put it, the central aim is change, ‘and the emphasis is on problem-solving in whatever way is appropriate’. It can be seen as a conversation rather more than a technique (McNiff et. al. ). It is about people ‘thinking for themselves and making their own choices, asking themselves what they should do and accepting the consequences of their own actions’ (Thomas 2009: 113).

The action research process works through three basic phases:

Look -building a picture and gathering information. When evaluating we define and describe the problem to be investigated and the context in which it is set. We also describe what all the participants (educators, group members, managers etc.) have been doing.

Think – interpreting and explaining. When evaluating we analyse and interpret the situation. We reflect on what participants have been doing. We look at areas of success and any deficiencies, issues or problems.

Act – resolving issues and problems. In evaluation we judge the worth, effectiveness, appropriateness, and outcomes of those activities. We act to formulate solutions to any problems. (Stringer 1999: 18; 43-44;160)

The use of action research to deepen and develop classroom practice has grown into a strong tradition of practice (one of the first examples being the work of Stephen Corey in 1949). For some, there is an insistence that action research must be collaborative and entail groupwork.

Action research is a form of collective self-reflective enquiry undertaken by participants in social situations in order to improve the rationality and justice of their own social or educational practices, as well as their understanding of those practices and the situations in which the practices are carried out… The approach is only action research when it is collaborative, though it is important to realise that action research of the group is achieved through the critically examined action of individual group members. (Kemmis and McTaggart 1988: 5-6)

Just why it must be collective is open to some question and debate (Webb 1996), but there is an important point here concerning the commitments and orientations of those involved in action research.

One of the legacies Kurt Lewin left us is the ‘action research spiral’ – and with it there is the danger that action research becomes little more than a procedure. It is a mistake, according to McTaggart (1996: 248) to think that following the action research spiral constitutes ‘doing action research’. He continues, ‘Action research is not a ‘method’ or a ‘procedure’ for research but a series of commitments to observe and problematize through practice a series of principles for conducting social enquiry’. It is his argument that Lewin has been misunderstood or, rather, misused. When set in historical context, while Lewin does talk about action research as a method, he is stressing a contrast between this form of interpretative practice and more traditional empirical-analytic research. The notion of a spiral may be a useful teaching device – but it is all too easy to slip into using it as the template for practice (McTaggart 1996: 249).

Further reading

This select, annotated bibliography has been designed to give a flavour of the possibilities of action research and includes some useful guides to practice. As ever, if you have suggestions about areas or specific texts for inclusion, I’d like to hear from you.

Explorations of action research

Atweh, B., Kemmis, S. and Weeks, P. (eds.) (1998) Action Research in Practice: Partnership for Social Justice in Education, London: Routledge. Presents a collection of stories from action research projects in schools and a university. The book begins with theme chapters discussing action research, social justice and partnerships in research. The case study chapters cover topics such as: school environment – how to make a school a healthier place to be; parents – how to involve them more in decision-making; students as action researchers; gender – how to promote gender equity in schools; writing up action research projects.

Carr, W. and Kemmis, S. (1986) Becoming Critical. Education, knowledge and action research , Lewes: Falmer. Influential book that provides a good account of ‘action research’ in education. Chapters on teachers, researchers and curriculum; the natural scientific view of educational theory and practice; the interpretative view of educational theory and practice; theory and practice – redefining the problem; a critical approach to theory and practice; towards a critical educational science; action research as critical education science; educational research, educational reform and the role of the profession.

Carson, T. R. and Sumara, D. J. (ed.) (1997) Action Research as a Living Practice , New York: Peter Lang. 140 pages. Book draws on a wide range of sources to develop an understanding of action research. Explores action research as a lived practice, ‘that asks the researcher to not only investigate the subject at hand but, as well, to provide some account of the way in which the investigation both shapes and is shaped by the investigator.

Dadds, M. (1995) Passionate Enquiry and School Development. A story about action research , London: Falmer. 192 + ix pages. Examines three action research studies undertaken by a teacher and how they related to work in school – how she did the research, the problems she experienced, her feelings, the impact on her feelings and ideas, and some of the outcomes. In his introduction, John Elliot comments that the book is ‘the most readable, thoughtful, and detailed study of the potential of action-research in professional education that I have read’.

Ghaye, T. and Wakefield, P. (eds.) CARN Critical Conversations. Book one: the role of the self in action , Bournemouth: Hyde Publications. 146 + xiii pages. Collection of five pieces from the Classroom Action Research Network. Chapters on: dialectical forms; graduate medical education – research’s outer limits; democratic education; managing action research; writing up.

McNiff, J. (1993) Teaching as Learning: An Action Research Approach , London: Routledge. Argues that educational knowledge is created by individual teachers as they attempt to express their own values in their professional lives. Sets out familiar action research model: identifying a problem, devising, implementing and evaluating a solution and modifying practice. Includes advice on how working in this way can aid the professional development of action researcher and practitioner.

Quigley, B. A. and Kuhne, G. W. (eds.) (1997) Creating Practical Knowledge Through Action Research, San Fransisco: Jossey Bass. Guide to action research that outlines the action research process, provides a project planner, and presents examples to show how action research can yield improvements in six different settings, including a hospital, a university and a literacy education program.

Plummer, G. and Edwards, G. (eds.) CARN Critical Conversations. Book two: dimensions of action research – people, practice and power , Bournemouth: Hyde Publications. 142 + xvii pages. Collection of five pieces from the Classroom Action Research Network. Chapters on: exchanging letters and collaborative research; diary writing; personal and professional learning – on teaching and self-knowledge; anti-racist approaches; psychodynamic group theory in action research.

Whyte, W. F. (ed.) (1991) Participatory Action Research , Newbury Park: Sage. 247 pages. Chapters explore the development of participatory action research and its relation with action science and examine its usages in various agricultural and industrial settings

Zuber-Skerritt, O. (ed.) (1996) New Directions in Action Research , London; Falmer Press. 266 + xii pages. A useful collection that explores principles and procedures for critical action research; problems and suggested solutions; and postmodernism and critical action research.

Action research guides

Coghlan, D. and Brannick, D. (2000) Doing Action Research in your own Organization, London: Sage. 128 pages. Popular introduction. Part one covers the basics of action research including the action research cycle, the role of the ‘insider’ action researcher and the complexities of undertaking action research within your own organisation. Part two looks at the implementation of the action research project (including managing internal politics and the ethics and politics of action research). New edition due late 2004.

Elliot, J. (1991) Action Research for Educational Change , Buckingham: Open University Press. 163 + x pages Collection of various articles written by Elliot in which he develops his own particular interpretation of action research as a form of teacher professional development. In some ways close to a form of ‘reflective practice’. Chapter 6, ‘A practical guide to action research’ – builds a staged model on Lewin’s work and on developments by writers such as Kemmis.

Johnson, A. P. (2007) A short guide to action research 3e. Allyn and Bacon. Popular step by step guide for master’s work.

Macintyre, C. (2002) The Art of the Action Research in the Classroom , London: David Fulton. 138 pages. Includes sections on action research, the role of literature, formulating a research question, gathering data, analysing data and writing a dissertation. Useful and readable guide for students.

McNiff, J., Whitehead, J., Lomax, P. (2003) You and Your Action Research Project , London: Routledge. Practical guidance on doing an action research project.Takes the practitioner-researcher through the various stages of a project. Each section of the book is supported by case studies

Stringer, E. T. (2007) Action Research: A handbook for practitioners 3e , Newbury Park, ca.: Sage. 304 pages. Sets community-based action research in context and develops a model. Chapters on information gathering, interpretation, resolving issues; legitimacy etc. See, also Stringer’s (2003) Action Research in Education , Prentice-Hall.

Winter, R. (1989) Learning From Experience. Principles and practice in action research , Lewes: Falmer Press. 200 + 10 pages. Introduces the idea of action research; the basic process; theoretical issues; and provides six principles for the conduct of action research. Includes examples of action research. Further chapters on from principles to practice; the learner’s experience; and research topics and personal interests.

Action research in informal education

Usher, R., Bryant, I. and Johnston, R. (1997) Adult Education and the Postmodern Challenge. Learning beyond the limits , London: Routledge. 248 + xvi pages. Has some interesting chapters that relate to action research: on reflective practice; changing paradigms and traditions of research; new approaches to research; writing and learning about research.

Other references

Bogdan, R. and Biklen, S. K. (1992) Qualitative Research For Education , Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Goetschius, G. and Tash, J. (1967) Working with the Unattached , London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

McTaggart, R. (1996) ‘Issues for participatory action researchers’ in O. Zuber-Skerritt (ed.) New Directions in Action Research , London: Falmer Press.

McNiff, J., Lomax, P. and Whitehead, J. (2003) You and Your Action Research Project 2e. London: Routledge.

Thomas, G. (2017). How to do your Research Project. A guide for students in education and applied social sciences . 3e. London: Sage.

Acknowledgements : spiral by Michèle C. | flickr ccbyncnd2 licence

How to cite this article : Smith, M. K. (1996; 2001, 2007, 2017) What is action research and how do we do it?’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education. [ https://infed.org/mobi/action-research/ . Retrieved: insert date] .

© Mark K. Smith 1996; 2001, 2007, 2017

Action Research

J. Spencer Clark, Kansas State University

Suzanne Porath, Kansas State University

Julie Thiele, Kansas State University

Morgan Jobe, Kansas State University

Copyright Year: 2020

Last Update: 2024

ISBN 13: 9781944548292

Publisher: New Prairie Press

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Cathy Stierman, Assistant Professor, Clarke University on 10/26/24

This text is very thorough in its overview of the action research process. The book is laid out according to the steps of the action research process and outlines each step thoroughly. It was very nice to see the authors address some of the... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

This text is very thorough in its overview of the action research process. The book is laid out according to the steps of the action research process and outlines each step thoroughly. It was very nice to see the authors address some of the misconceptions of action research. The chapter on the types of literature that can be utilized in doing research is especially strong. I especially appreciate that the authors included an entire chapter on thoughtfully preparing for action research and suggestions for maintaining focus and patience with the research process. Helpful extras include the use of colored blocks to highlight important concepts and links to actual action research samples.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

I compared the content to two other books I am currently using and found the information in this book to be accurate.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

This book is written such that in-service teachers, undergraduate students, and graduate students can all utilize this book. Users will find it helpful that the book is laid out in the order of the steps of action research. The sample papers are a little old as most are from 2016-2019, but the topics are still timely.

Clarity rating: 5

The language used in this text is concise and easy to read. The authors speak directly to the reader. All vocabulary is explained thoroughly and multiple examples are provided. Key pieces of information are set within colored blocks to draw attention to them. Each chapter begins with a set of essential questions so the reader knows exactly what will be discussed in that section.

Consistency rating: 5

The book is laid out according to the steps of action research, modeling the action research process. Each chapter begins with a set of essential questions. Each section within a chapter is clearly identified and each step is outlined thoroughly. The font is easy to read and the text materials is regularly broken by color blocks or illustrations that highlight important concepts.

Modularity rating: 5

Each chapter is around 20 pages in length but the margins are large and there are illustrations and highlighted blocks of text throughout. The subsections are bolded and could be utilized when assigning readings. This book is meant to be read from beginning to end as it mirrors the action research process, but the descriptions are thorough enough that reading single sections in isolation is possible.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

The book is laid out according to the steps of the action research, mirroring the process itself. It lends itself easily as a reference to use both before and during the research activity.

Interface rating: 5

I tried out the online version and downloaded a pdf of the text. The online version has each chapter as a single page, which was very helpful as I could scan a single page quickly for the section I needed. The previous and upcoming chapters are identified in the links at the bottom of the page, which was also very helpful. I'm going to encourage my students to use this version. The pdf is a quick download but isn't quite as easy to navigate as the online version. When trying to locate a single section one has to either know the page number or scroll through the entire document.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

I found no grammatical errors.

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

While the steps of action research are rather generic, the authors did take time to explain what the research process might look in practice in a classroom. An entire chapter is dedicated to the practical aspects of doing respectful research with students and provides guidance on a variety of situations and needs that one might need to keep in mind both in the development and action phases.

I loved this book and am excited to adopt it for my introductory graduate course on action research!

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- About the Authors

- What is Action Research for Classroom Teachers?

- Action Research as a Process for Professional Learning and Leadership

- Planning Your Research: Reviewing the Literature and Developing Questions

- Preparing for Action Research in the Classroom: Practical Issues

- Collecting Data in Your Classroom

- Analyzing Data from Your Classroom

- Let it Be Known! Sharing your Results

- The Action Research Process from a High School ELA Teacher’s Perspective

Ancillary Material

About the book.

Action research is a common journey for graduate students in education and other human science fields. This book attempts to meet the needs of graduate students, in-service teachers, and any other educators interested in action research and/or self-study. The chapters of this book draw on our collective experiences as educators in a variety of educational contexts, and our roles guiding educator/researchers in various settings. All of our experiences have enabled us to question and refine our own understanding of action research as a process and means for pedagogical improvement. The primary purpose of this book is to offer clear steps and practical guidance to those who intend to carry out action research for the first time. As educators begin their action research journey, we feel it is vital to pose four questions: 1) What is action research, and how is it distinct from other educational research?; 2) When is it appropriate for an educator to conduct an action research project in their context?; 3) How does an educator conduct an action research project?; 4) What does an educator do with the data once the action research project has been conducted? We have attempted to address all four questions in the chapters of this book.

About the Contributors

J. Spencer Clark is an Associate Professor of Curriculum Studies at Kansas State University. He has used action research methodology for the past 17 years, in K-12 schools and higher education. More recently, for the past 10 years he has taught action research methods to teachers in graduate and licensure degree programs. He also has led secondary student action research projects in Indiana, Utah, and Kansas. Clark also utilizes action research methodology in his own research. Much of his research has focused on understanding and developing teacher agency through clinical and professional learning experiences that utilize aspects of digital communication, inquiry, collaboration, and personalized learning. He has published in a variety of journals and edited books on teacher education, technology, inquiry-based learning, and curriculum development.

Suzanne Porath has been an English Language Arts, history, and humanities classroom teacher and reading teacher for 13 years before becoming a teacher educator. She has taught in Wisconsin and American international schools in Brazil, Lithuania, and Aruba when she conducted her own action research projects. Before accepting her current position as an assistant professor at Kansas State University in Curriculum and Instruction, she taught at Concordia University and Edgewood College in Wisconsin. She has taught action research methods at the graduate level and facilitated professional development through action research in school districts. She is the lead editor of Networks: An Online Journal for Teacher Research https://newprairiepress.org/networks/ .

Julie Thiele , PhD. is an Assistant Professor at Kansas State University. She teaches math education courses, math and science education courses and graduate research courses. Prior to teaching at KSU, she taught elementary and middle school, and led her district level professional learning community, focusing on implementing effective, research-based teaching practices.

Morgan M. Jobe is a program coordinator in the College of Education at Kansas State University, where she also earned a bachelor’s degree in secondary education and a master’s degree in curriculum and instruction. Morgan taught high school English-Language Arts for ten years in two different Kansas school districts before returning to Kansas State University as a staff member. Her research interests include diversity and equity issues in public education, as well as action research in teacher education programs.

Contribute to this Page

COMMENTS

Action research is a research method that aims to simultaneously investigate and solve an issue. In other words, as its name suggests, action research conducts research and takes action at the same time. It was first coined as a term in 1944 by MIT professor Kurt Lewin.A highly interactive method, action research is often used in the social ...

Introduction. Action research is an approach to qualitative inquiry in social science research that involves the search for practical solutions to everyday issues. Rooted in real-world problems, it seeks not just to understand but also to act, bringing about positive change in specific contexts. Often distinguished by its collaborative nature ...

Stage 1: Plan. For an action research project to go well, the researcher needs to plan it well. After coming up with an educational research topic or question after a research study, the first step is to develop an action plan to guide the research process. The research design aims to address the study's question. The research strategy outlines what to undertake, when, and how.

Action research (AR) is a methodical process of self-inquiry accomplished by practitioners to unravel work-related problems. This paper analyzed the action research reports (ARRs) in terms of ...

tioners. Examples of action research projects undertaken by healthcare practitioners in a range of situations are provided later in this chapter. The development of action research: a brief background Whether the reader is a novice or is progressing with an action research project, it would be useful to be aware of how action research has devel-

in an action research project 94. 1.2.1. Identi cation and analysis of stakeholders 94. 1.2.2. Building a relationship: challenges and action strategies 96. 1.3. Research community 97. 2.

Action research is a philosophy and methodology of research generally applied in the social sciences. It seeks transformative change through the simultaneous process of taking action and doing research, which are linked together by critical reflection. ... Major adjustments and reevaluations would return the OD project to the first or planning ...

ACTION RESEARCH. is a rather simple set of ideas and techniques that can introduce you to the power of systematic reflection on your practice. Our basic assumption is that you have within you the power to meet all the challenges of the teaching profession. Furthermore, you can meet these challenges without wearing yourself down to a nub.

Guide to action research that outlines the action research process, provides a project planner, and presents examples to show how action research can yield improvements in six different settings, including a hospital, a university and a literacy education program. Plummer, G. and Edwards, G. (eds.) CARN Critical Conversations.

Action research is a common journey for graduate students in education and other human science fields. This book attempts to meet the needs of graduate students, in-service teachers, and any other educators interested in action research and/or self-study. The chapters of this book draw on our collective experiences as educators in a variety of educational contexts, and our roles guiding ...