Top 40 Most Popular Case Studies of 2021

Two cases about Hertz claimed top spots in 2021's Top 40 Most Popular Case Studies

Two cases on the uses of debt and equity at Hertz claimed top spots in the CRDT’s (Case Research and Development Team) 2021 top 40 review of cases.

Hertz (A) took the top spot. The case details the financial structure of the rental car company through the end of 2019. Hertz (B), which ranked third in CRDT’s list, describes the company’s struggles during the early part of the COVID pandemic and its eventual need to enter Chapter 11 bankruptcy.

The success of the Hertz cases was unprecedented for the top 40 list. Usually, cases take a number of years to gain popularity, but the Hertz cases claimed top spots in their first year of release. Hertz (A) also became the first ‘cooked’ case to top the annual review, as all of the other winners had been web-based ‘raw’ cases.

Besides introducing students to the complicated financing required to maintain an enormous fleet of cars, the Hertz cases also expanded the diversity of case protagonists. Kathyrn Marinello was the CEO of Hertz during this period and the CFO, Jamere Jackson is black.

Sandwiched between the two Hertz cases, Coffee 2016, a perennial best seller, finished second. “Glory, Glory, Man United!” a case about an English football team’s IPO made a surprise move to number four. Cases on search fund boards, the future of malls, Norway’s Sovereign Wealth fund, Prodigy Finance, the Mayo Clinic, and Cadbury rounded out the top ten.

Other year-end data for 2021 showed:

- Online “raw” case usage remained steady as compared to 2020 with over 35K users from 170 countries and all 50 U.S. states interacting with 196 cases.

- Fifty four percent of raw case users came from outside the U.S..

- The Yale School of Management (SOM) case study directory pages received over 160K page views from 177 countries with approximately a third originating in India followed by the U.S. and the Philippines.

- Twenty-six of the cases in the list are raw cases.

- A third of the cases feature a woman protagonist.

- Orders for Yale SOM case studies increased by almost 50% compared to 2020.

- The top 40 cases were supervised by 19 different Yale SOM faculty members, several supervising multiple cases.

CRDT compiled the Top 40 list by combining data from its case store, Google Analytics, and other measures of interest and adoption.

All of this year’s Top 40 cases are available for purchase from the Yale Management Media store .

And the Top 40 cases studies of 2021 are:

1. Hertz Global Holdings (A): Uses of Debt and Equity

2. Coffee 2016

3. Hertz Global Holdings (B): Uses of Debt and Equity 2020

4. Glory, Glory Man United!

5. Search Fund Company Boards: How CEOs Can Build Boards to Help Them Thrive

6. The Future of Malls: Was Decline Inevitable?

7. Strategy for Norway's Pension Fund Global

8. Prodigy Finance

9. Design at Mayo

10. Cadbury

11. City Hospital Emergency Room

13. Volkswagen

14. Marina Bay Sands

15. Shake Shack IPO

16. Mastercard

17. Netflix

18. Ant Financial

19. AXA: Creating the New CR Metrics

20. IBM Corporate Service Corps

21. Business Leadership in South Africa's 1994 Reforms

22. Alternative Meat Industry

23. Children's Premier

24. Khalil Tawil and Umi (A)

25. Palm Oil 2016

26. Teach For All: Designing a Global Network

27. What's Next? Search Fund Entrepreneurs Reflect on Life After Exit

28. Searching for a Search Fund Structure: A Student Takes a Tour of Various Options

30. Project Sammaan

31. Commonfund ESG

32. Polaroid

33. Connecticut Green Bank 2018: After the Raid

34. FieldFresh Foods

35. The Alibaba Group

36. 360 State Street: Real Options

37. Herman Miller

38. AgBiome

39. Nathan Cummings Foundation

40. Toyota 2010

How six companies are using technology and data to transform themselves

The next normal: The recovery will be digital

A study referenced in the popular magazine Psychology Today concluded that it takes an average of 66 days for a behavior to become automatic. If that’s true, that’s good news for business leaders who have spent the past five months running their companies in ways they never could have imagined. The COVID-19 pandemic is a full-stop on business as usual and a launching pad for organizations to become virtual, digital-centric, and agile—and to do it all at lightning-fast speed.

Now, as leaders look ahead to the next year and beyond, they’re asking: How do we keep this momentum going? How do we take the best of what we’ve learned and put into practice throughout the pandemic, and make sure it’s woven into everything we do going forward? “Business leaders are saying that they’ve accomplished in 10 days what used to take them 10 months,” says Kate Smaje, a senior partner and global co-leader of McKinsey Digital . “That kind of speed is what’s unleashing a wave of innovation unlike anything we’ve ever seen.”

“The crisis has forced every company into a massive experiment in how to be more nimble, flexible, and fast.” Kate Smaje, senior partner, McKinsey & Company

That realization is coming not a moment too soon. Even before the global health crisis hit, 92 percent of company leaders surveyed by McKinsey thought that their business model would not remain viable at the rates of digitization at that time. The pandemic just put that whole scenario on steroids. The companies that are leading the way out of this crisis, the ones that will grab market share and set the tone and tempo for others, are the ones first out of the gate. “The fundamental reality is that the accelerating speed of digital means that we are increasingly living in a winner-take-all world,” Smaje says. “But simply going faster isn’t the answer. Rather, winning companies are investing in the tech, data, processes, and people to enable speed through better decisions and faster course corrections based on what they learn.”

Large incumbents who are winning the digital transformation battle get lots of things right. But McKinsey research has highlighted a few elements that really stand out:

- Digital speed. Leading companies just operate faster, from reviewing strategies to allocating resources. For example, they reallocate talent and capital four times more quickly than their peers.

- Ready to reinvent. While businesses need to maintain the profitable elements of their business, business as usual is a dangerous posture. Leading businesses are investing as much in upgrading the core of their business as they are in innovation, often by harnessing technology.

- All in. These companies aren’t just making decisions faster; the decisions themselves are bolder. Two of the most important areas where this kind of commitment shines through are major acquisitions (leaders spend three times more than their peers) and capital bets (leaders spend two times what their peers do).

- Data-driven decisions. “The road to recovery is paved with data,” Smaje says. Data is providing the fuel to power better and faster decisions. High-performing organizations are three times more likely than others to say their data and analytics initiatives have contributed at least 20 percent to EBIT (from 2016–19).

- Customer followers. Being “customer centric” is well established. But competing pressures and priorities mean that the customer can often be sidelined. Top companies that sustain a comprehensive focus on the customer (in addition to operational and IT improvements) can generate economic gains ranging from 20 to 50 percent of the cost base.

The companies you’re going to meet here are adopting and deploying these digital strategies and approaches at warp speed. Aside from moving thousands of employees from the office, call center, and factory floor to home overnight, they’re using these technologies to rejigger supply chains, stand up entirely new e-commerce channels, and leverage AI and predictive analytics to unearth smarter and more sustainable ways to operate.

I have clients saying that they’ve accomplished in 10 days what used to take them 10 months. Kate Smaje, senior partner, McKinsey & Company

Speed of digital

Most people don’t think of real estate as a particularly tech-savvy sector, but RXR Realty is proving that assumption wrong. Even before the pandemic hit, the New York City–based commercial and residential real estate developer began investing in the digital capabilities that would set it apart from competitors. “Historically, real estate has been a very transactional business,” explains Scott Rechler, CEO of RXR. “We felt that by leveraging our digital skills, we could create a unique and personalized experience for our customers similar to what they’re used to in other aspects of their lives.”

Prior to the global health crisis, RXR had established a digital lab . The company now has more than 100 data scientists, designers, and engineers across the organization working on digital initiatives. The investment in those capabilities—an app that enables move scheduling, deliveries, dog walking, and rent payments on the residential side, and real-time analytics on heating, cooling, and floor space optimization for tenants on the commercial side—allowed RXR to pivot quickly once the pandemic hit. Suddenly, physical distancing and the need for contactless interactions became paramount for RXR’s tenants.

Today, this team is working around the clock to put in place the health and safety protocols that allow tenants to feel safe as they return to the office. Its platform—RxWell—includes a new mobile app that provides information about air quality and occupancy levels of a building, cleaning status, food delivery options, and shift times for worker arrivals. Employees have their temperatures taken via thermal scanners when they enter a building, and heat maps are available online that show how full a restroom or conference room is at any given time. “The investments we made in our digital capabilities before the pandemic are why we’re able to give people peace of mind now as they begin to return to work,” Rechler says.

Reinventing yourself

The exponential growth in digitization coupled with consumer dissatisfaction with traditional brick-and-mortar banking has been driving the launch of fintechs with amazing speed over the past decade. That fact wasn’t lost on investment banking giant Goldman Sachs, which launched Marcus by Goldman Sachs in 2016. Marcus, the firm’s digital consumer business is, as global head Harit Talwar likes to describe it, “a 150-year-old startup that allows people to take control of their financial lives from their phone.” Over the past four years, this digital-first business has grown deposits to $92 billion and $7 billion in lending balances through a combination of organic growth, acquisitions, and partnerships with the likes of Apple and Amazon. Marcus has millions of customers in the United States and United Kingdom.

A digital-first philosophy, Talwar says, means that decisions on new products and services happen quickly. For instance, when the pandemic hit, Marcus realized that some of its customers were going to need assistance. The team decided to allow folks to defer payments on loans and credit cards for several months, without accruing interest. “The real news is not that we did this, but that we took just 72 hours from the time we realized customers needed help to when we rolled it out,” Talwar says. “We were able to do this because of our agile digital technology model.”

For Indonesian mining company Petrosea, the stakes involved in digital transformation were nothing less than survival. Industry changes, increased regulatory requirements, and society’s pushback on mining’s environmental footprint had culminated in what President Director Hanifa Indradjaya calls “an existential threat” for the company. “We’re not the biggest player in the industry, so that left us quite vulnerable,” he says. “If we were to survive, the status quo was not an option.”

In 2018, the company embarked on a three-pronged approach that addressed diversification away from coal, digitization, and decarbonization of its operations. At its Tabang project site, located in a remote area of East Kalimantan, Indonesia, the company employed a suite of advanced technologies, including artificial intelligence (AI) , smart sensors, and machine learning. The sensors enable predictive maintenance of its fleets of trucks, allowing the company to use fewer trucks and address breakdowns before they happen.

To move away from coal and toward copper, nickel, gold, and lithium—the minerals that are required as electrification of developing countries continues—the company is developing a suite of AI-enabled digital technologies to find these metals faster and more efficiently. Addressing its considerable reskilling needs—the majority of Tabang’s workers have no more than a high school education—resulted in the development of a mobile app with popular gamification elements, ensuring that employees would stay engaged and complete their training. The upshot: within six months, Tabang became one of the company’s most profitable operations by reducing costs and increasing production. “Technology enabled us to innovate our business model and remain relevant,” Indradjaya says. “A digital mindset now percolates through every aspect of the company.”

Data-driven decisions

Freeport-McMoRan is combining the power of AI and the institutional knowledge of its veteran engineers and metallurgists to take its operations to another level. Harry “Red” Conger, chief operating officer of the Phoenix-based company, says real-time data is allowing Freeport to lower operating costs, stand more resilient in tough economic climates (and when commodity prices are falling) and make faster decisions. “A learn-fast culture means we put things into action,” he says. “We don’t sit around thinking about it.”

Case in point: in 2018, Freeport was looking to add capacity at one of its more efficient copper mines—the sprawling complex in Bagdad, Arizona. A $200 million expansion plan, it figured, would enable the company to extract more copper from the site. But a few months later, copper prices dropped—and so, too, was the expensive expansion plan.

Quickly, the company figured out another way. Rather than a huge capital outlay, Freeport began building out an AI model that would allow it to wring more productivity out of the Bagdad site. Decades of mining data—what Conger calls “recipes”—had always dictated the mining process, including how machines and other equipment were run. Data scientists were now being brought in to challenge those long-standing processes.

“Our engineers thought that it was blasphemy that data scientists, who don’t know anything about metallurgy, were proposing that they knew how to run the plant better than they did,” Conger says. But what the AI data showed was that some of the historical recipes were limiting what Freeport was getting out of the Bagdad plant. “The AI model was telling us how much faster the equipment could be run and its maximum capacity,” he adds. By analyzing every aspect of the mining process, the AI models were showing what was possible.

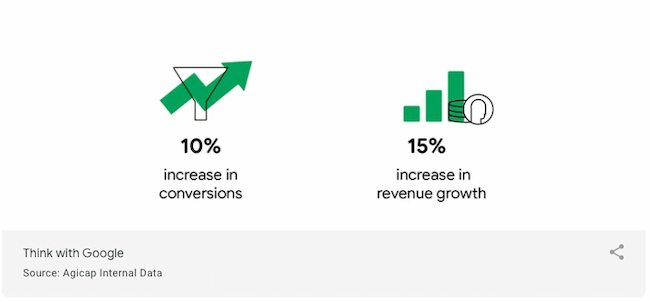

The engineers and metallurgists worked hand in hand with the data scientists. Over the next few months, they began to trust more of the AI recommendations on how to optimize the Bagdad plant. Today, the mine’s processing rate is 10 percent higher than it’s ever been, Conger says, and this same agile AI model is being used at eight of the company’s other mines, including one in Peru that has five times the capacity of Bagdad. Says Conger: “I have people tell me this is the only way they want to work.”

A follow-the-customer mindset

One of the biggest transformations that’s occurred throughout the pandemic is how customers shop. Store closings pushed millions of consumers online, many for the first time. Adapting to this shift quickly and seamlessly became the order of the day for so many retailers the world over. Among them: Levi Strauss and Majid Al Futtaim Retail.

As a company that’s been around for more than 100 years, Levi Strauss knows how to pace itself. But the pandemic threw into overdrive initiatives that were planned out for later this year and beyond. Chief Financial Officer Harmit Singh says the San Francisco–based apparel company was ready. Investments in digital technologies, including AI and predictive analytics, before the pandemic hit allowed Levi’s to react quickly and decisively as consumers switched to e-commerce channels in droves.

To meet demand, the company began fulfilling online orders not just with merchandise in fulfillment centers but from its stores. Prior to the health crisis, Singh says it would have taken weeks or months to work out the logistics of such a move, but as the pandemic rolled across the country, Levi’s was able to accomplish the shift in a matter of days. It quickly launched curbside pickup at about 80 percent of its roughly 200 US-based stores. And while it launched its mobile app before the appearance of COVID-19, the company has leveraged it in creative ways to connect with consumers during the pandemic. “It was important for us to enhance our engagement and stay connected with customers who were at home,” he says.

Even before the global health crisis hit, 92 percent of company leaders surveyed by McKinsey thought that their business model would not remain viable at the rates of digitization at that time.

Last year, Levi’s began making investments in AI and data in order to get a better handle on when and how to run promotions. A campaign that ran in May throughout Europe was launched using information gleaned from an AI model and wound up driving sales that were five times higher than in 2019. “AI gives us the ability to quickly transform data and facts into action,” Singh says. “We’re using this intelligence alongside our own consumer expertise and judgment to drive better results.”

Majid Al Futtaim, the Dubai-based conglomerate that operates the Carrefour grocery chain in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia, was building its digital muscle long before COVID-19. It decided back in 2015 that it needed to be as prominent online as it is in its 315 brick-and-mortar stores across 16 countries, says Hani Weiss, CEO of Majid Al Futtaim Retail. The company was making progress, but Weiss says there was little urgency to move any faster.

Then the pandemic hit. Online grocery orders for the company exploded, and they are now 400 percent higher than what they were in 2019. “The pandemic pushed us to accelerate our digital transformation,” Weiss says. “We are implementing in the coming 18 months things we originally said we wanted to achieve in five years.”

To accommodate increased online shopping demand, the company quickly converted some physical stores to fulfillment centers. When data showed that more capacity was needed, logistics managers quickly arranged to have a 54,000-square-foot online fulfillment center tent erected and operational in five weeks. Complete with rooms for frozen and chilled food, the facility stocks more than 8,000 items and is now handling 3,000 online orders a day, making it the latest and largest of 75 fulfillment centers launched this year.

Weiss says the company expanded delivery services through initiatives such as Click and Collect, redesigned its app to make it easier for customers to use, and launched contactless payment options such as Mobile Scan and Go in its stores, which allow customers to scan items on, and pay with, their smartphones. It also launched an online marketplace with 420,000 new products from other retailers whose stores were closed during the lockdown, enabling them to continue to sell their products online.

“No matter how our customers want to shop, we can be there for them,” Weiss says. “We developed this agility through the pandemic, and I want to keep it as we go forward.”

The road ahead will certainly have challenges, these leaders acknowledge. But there’s also a tremendous amount of hope because of the doors that a digital-first strategy can open. “The companies that are winning aren’t making incremental improvements,” Smaje says. “They’re harnessing technology to reimagine how business runs and committing resources at sufficient scale to make sure the change sticks.”

Go behind the scenes and get more insights with “ Kate Smaje: Why businesses must act faster than ever on digitization ” from our New at McKinsey blog.

Related Articles

COVID-19: Implications for business

The coronavirus effect on global economic sentiment

Case study on adoption of new technology for innovation: Perspective of institutional and corporate entrepreneurship

Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship

ISSN : 2398-7812

Article publication date: 7 August 2017

This paper aims at investigating the role of institutional entrepreneurship and corporate entrepreneurship to cope with firm’ impasses by adoption of the new technology ahead of other firms. Also, this paper elucidates the importance of own specific institutional and corporate entrepreneurship created from firm’s norm.

Design/methodology/approach

The utilized research frame is as follows: first, perspective of studies on institutional and corporate entrepreneurship are performed using prior literature and preliminary references; second, analytical research frame was proposed; finally, phase-based cases are conducted so as to identify research objective.

Kumho Tire was the first tire manufacturer in the world to exploit the utilization of radio-frequency identification for passenger carâ’s tire. Kumho Tire takes great satisfaction in lots of failures to develop the cutting edge technology using advanced information and communication technology cultivated by heterogeneous institution and corporate entrepreneurship.

Originality/value

The firm concentrated its resources into building the organization’s communication process and enhancing the quality of its human resources from the early stages of their birth so as to create distinguishable corporate entrepreneurship.

- Corporate entrepreneurship

- Institutional entrepreneurship

Han, J. and Park, C.-m. (2017), "Case study on adoption of new technology for innovation: Perspective of institutional and corporate entrepreneurship", Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship , Vol. 11 No. 2, pp. 144-158. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJIE-08-2017-031

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2017, Junghee Han and Chang-min Park.

Published in the Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial & non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode

1. Introduction

Without the entrepreneur, invention and new knowledge possibly have lain dormant in the memory of persons or in the pages of literature. There is a Korean saying, “Even if the beads are too much, they become treasure after sewn”. This implies importance of entrepreneurship. In general, innovativeness and risk-taking are associated with entrepreneurial activity and, more importantly, are considered to be important attributes that impact the implementation of new knowledge pursuing.

Implementation of cutting edge technology ahead of other firms is an important mechanism for firms to achieve competitive advantage ( Capon et al. , 1990 ; D’Aveni, 1994 ). Certainly, new product innovation continues to play a vital role in competitive business environment and is considered to be a key driver of firm performance, especially as a significant form of corporate entrepreneurship ( Srivastava and Lee, 2005 ). Corporate entrepreneurship is critical success factor for a firm’s survival, profitability and growth ( Phan et al. , 2009 ).

The first-mover has identified innovativeness and risk-taking as important attributes of first movers. Lumpkin and Dess (1996) argued that proactiveness is a key entrepreneurial characteristic related to new technology adoption and product. This study aims to investigate the importance of corporate and institutional entrepreneurship through analyzing the K Tire’s first adaptation of Radio-frequency identification (RFID) among the world tire manufactures. Also, this paper can contribute to start ups’ readiness for cultivating of corporate and institutional entrepreneurship from initial stage to grow and survive.

K Tire is the Korean company that, for the first time in the world, applied RFID to manufacturing passenger vehicle tires in 2013. Through such efforts, the company has built an innovation model that utilizes ICTs. The adoption of the technology distinguishes K Tire from other competitors, which usually rely on bar codes. None of the global tire manufacturers have applied the RFID technology to passenger vehicle tires. K Tire’s decision to apply RFID to passenger vehicle tires for the first time in the global tire industry, despite the uncertainties associated with the adoption of innovative technologies, is being lauded as a successful case of innovation. In the global tire market, K Tire belongs to the second tier, rather than the leader group consisting of manufacturers with large market shares. Then, what led K Tire to apply RFID technology to the innovation of its manufacturing process? A company that adopts innovative technologies ahead of others, even if the company is a latecomer, demonstrates its distinguishing characteristics in terms of innovation. As such, this study was motivated by the following questions. With regard to the factors that facilitate innovation, first, what kind of the corporate and institutional situations that make a company more pursue innovation? Second, what are the technological situations? Third, how do the environmental situations affect innovation? A case study offers the benefit of a closer insight into the entrepreneurship frame of a specific company. This study has its frame work rooted in corporate entrepreneurship ( Guth and Ginsberg, 1990 ; Shane and Venkataraman, 2000 ) and institutional entrepreneurship ( Battilana, 2006 ; Fligstein, 1997 ; Rojas, 2010 ). As mentioned, we utilized qualitative research method ( Yin, 2008 ). This paper is structured as follows. Section two presents the literature review, and section three present the methodology and a research case. Four and five presents discussion and conclusions and implications, respectively.

2. Theoretical review and analysis model

RFID technology is to be considered as not high technology; however, it is an entirely cutting edged skills when combined with automotive tire manufacturing. To examine why and how the firm behaves like the first movers, taking incomparable high risks to achieve aims unlike others, we review three kinds of prior literature. As firms move from stage to stage, they have to revamp innovative capabilities to survive and ceaseless stimulate growth.

2.1 Nature of corporate entrepreneurship

Before reviewing the corporate entrepreneurship, it is needed to understand what entrepreneurship is. To more understand the role that entrepreneurship plays in modern economy, one need refer to insights given by Schumpeter (1942) or Kirzner (1997) . Schumpeter suggests that entrepreneurship is an engine of economic growth by utilization of new technologies. He also insists potential for serving to discipline firms in their struggle to survive gale of creative destruction. While Schumper argued principle of entrepreneurship, Kirzner explains the importance of opportunities. The disruptions generated by creative destruction are exploited by individuals who are alert enough to exploit the opportunities that arise ( Kirzner, 1997 ; Shane and Venkataraman, 2000 ).

Commonly all these perspectives on entrepreneurship is an appreciation that the emergence of novelty is not an easy or predictable process. Based on literature review, we note that entrepreneurship is heterogeneous interests and seek “something new” associated with novel outcomes. Considering the literature review, we can observe that entrepreneurship is the belief in individual autonomy and discretion, and a mindset that locates agency in individuals for creating new activities ( Meyer et al. ,1994 ; Jepperson and Meyer, 2001 ).

the firm’s commitment to innovation (including creation and introduction of products, emphasis on R&D investments and commitment to patenting);

the firm’s venturing activities, such as entry into new business fields by sponsoring new ventures and creating new businesses; and

strategic renewal efforts aimed at revitalizing the firm’s ability to compete.

developing innovation an organizational tool;

allowing the employees to propose ideas; and

encouraging and nurturing the new knowledge ( Hisrich, 1986 ; Kuratko, 2007 ).

Consistent with the above stream of research, our paper focuses on a firm’s new adaptation of RFID as a significant form of corporate entrepreneurial activity. Thus, CE refers to the activities a firm undertakes to stimulate innovation and encourage calculated risk taking throughout its operations. Considering prior literature reviews, we propose that corporate entrepreneurship is the process by which individuals inside the organization pursuing opportunities without regards to the resources they control.

If a firm has corporate entrepreneurship, innovation (i.e. transformation of the existing firm, the birth of new business organization and innovation) happens. In sum, corporate entrepreneurship plays a role to pursue to be a first mover from a latecomer by encompassing the three phenomena.

2.2 Institution and institutional entrepreneurship

Most literature regarding entrepreneurship deals with the attribute of individual behavior. More recently, scholars have attended to the wider ecosystem that serves to reinforce risk-taking behavior. Institution and institutional entrepreneurship is one way to look at ecosystem that how individuals and groups attempt to try to become entrepreneurial activities and innovation.

Each organization has original norm and intangible rules. According to the suggestion by Scott (1995) , institutions constrain behavior as a result of processes associated with institutional pillars. The question how actors within the organizations become motivated and enabled to transform the taken-for-granted structures has attracted substantial attention for institutionalist. To understand why some firms are more likely to seek innovation activities despite numerous difficulties and obstacles, we should take look at the institutional entrepreneurship.

the regulative, which induces worker’s action through coercion and formal sanction;

the normative, which induces worker’s action through norms of acceptability and ethics; and

the cognitive, which induces worker’s action through categories and frames by which actors know and interpret their world.

North (1990) defines institutions as the humanly devised constraints that structure human action. Actors within some organization with sufficient resources have intend to look at them an opportunity to realize interests that they value highly ( DiMaggio, 1988 ).

It opened institutional arguments to ideas from the co-evolving entrepreneurship literature ( Aldrich and Fiol, 1994 ; Aldrich and Martinez, 2001 ). The core argument of the institutional entrepreneurship is mechanisms enabling force to motivate for actors to act difficult task based on norm, culture and shared value. The innovation, adopting RFID, a technology not verified in terms of its effectiveness for tires, can be influenced by the institution of the society.

A firm is the organizations. An organization is situated within an institution that has social and economic norms. Opportunity is important for entrepreneurship. The concept of institutional entrepreneurship refer to the activities of worker or actor who have new opportunity to realize interest that they values highly ( DiMaggio, 1988 ). DiMaggio (1988) argues that opportunity for institutional entrepreneurship will be “seen” and “exploited” by within workers and not others depending on their resources and interests respectively.

Despite that ambiguity for success was given, opportunity and motivation for entrepreneurs to act strategically, shape emerging institutional arrangements or standards to their interests ( Fligstein and Mara-Drita, 1996 ; Garud et al. , 2002 ; Hargadon and Douglas, 2001 ; Maguire et al. , 2004 ).

Resource related to opportunity within institutional entrepreneurship include formal or informal authority and power ( Battilana, 2006 ; Rojas, 2010 ). Maguire et al. (2004) suggest legitimacy as an important ingredient related to opportunity for institutional entrepreneurship. Some scholars suggest opportunity resources for institutional entrepreneurship as various aspects. For instance, Marquire and Hardy (2009) show that knowledge and expertise is more crucial resources. Social capital, including market leadership and social network, is importance resource related to opportunity ( Garud et al. , 2002 ; Lawrence et al. , 2005 ; Townley, 2002 ). From a sociological perspective, change associated with entrepreneurship implies deviations from some norm ( Garud and Karnøe, 2003 ).

Institutional entrepreneurship is therefore a concept that reintroduces agency, interests and power into institutional analyses of organizations. Based on the previous discussion, this study defines institution as three processes of network activity; coercion and formal sanction, normative and cognitive, to acquire the external knowledge from adopting common goals and rules inside an organization. It would be an interesting approach to look into a specific company to see whether it is proactive towards adopting ICTs (e.g. RFID) and innovation on the basis of such theoretical background.

2.3. Theoretical analysis frame

Companies innovate themselves in response to the challenges of the ever-changing markets and technologies, so as to ensure their survival and growth ( Tushman and Anderson, 1986 ; Tidd and Bessant, 2009 ; Teece, 2014 ). As illustrated above, to achieve the purpose of this study, the researcher provides the following frames of analyses based on the theoretical background discussed above ( Figure 1 ).

3. Case study

3.1 methodology.

It is a highly complicated and tough task to analyze the long process of innovation at a company. In this paper, we used analytical approach rather than the problem-oriented method because the case is examined to find and understand what has happened and why. It is not necessary to identify problems or suggest solutions. Namely, this paper analyzes that “why K Tire becomes a first mover from a late comer through first adoption of RFID technology for automotive tire manufacture with regards to process and production innovations”.

To study the organizational characteristics such as corporate entrepreneurship, institutional entrepreneurship, innovation process of companies, the qualitative case study is the suitable method. This is because a case study is a useful method when verifying or expanding well-known theories or challenging a specific theory ( Yin, 2008 ). This study seeks to state the frame of analysis established, based on previously established theories through a single case. K Tire was selected as the sample because it is the first global tire manufacturer, first mover to achieve innovation by developing and applying RFID.

The data for the case study were collected as follows. First, this study was conducted from April 2015 to the end of December 2015. Additional expanded data also were collected from September 12 to November 22, 2016, to pursue the goal of this paper. Coauthor worked for K Tire for more than 30 year, and currently serves as the CEO of an affiliate company. As such, we had the most hands-on knowledge and directed data in the process of adoption RFID. This makes this case study a form of participant observation ( Yin, 2008 ). To secure data on institutional entrepreneurship, in-depth interviews were conducted with the vice president of K Tire. The required data were secured using e-mail, and the researchers accepted the interviewees’ demand to keep certain sensitive matters confidential. The interviewees agreed to record the interview sessions. In this way, a 20-min interview data were secured for each interviewee. In addition, apart from the internal data of the subject company, other objective data were obtained by investigating various literatures published through the press.

3.2 Company overview

In September 1960, K Tire was established in South Korea as the name of Samyang Tire. In that time, the domestic automobile industry in Korea was at a primitive stage, as were auto motive parts industries like the tire industry. K Tire products 20 tires a day, depending on manual labor because of our backward technology and shortage of facilities.

The growth of K Tire was astonishment. Despite the 1974 oil shock and difficulties in procuring raw materials, K Tire managed to achieve remarkable growth. In 1976, K Tire became the leader in the tire sector and was listed on the Korea Stock Exchange. Songjung plant II was added in 1977. Receiving the grand prize of the Korea Quality Control Award in 1979, K Tire sharpened its corporate image with the public. The turmoil of political instability and feverish democratization in the 1980s worsened the business environment. K Tire also underwent labor-management struggles but succeeded in straightening out one issue after another. In the meantime, the company chalked up a total output of 50 million tires, broke ground for its Koksung plant and completed its proving ground in preparation for a new takeoff.

In the 1990s, K Tire expanded its research capability and founded technical research centers in the USA and the United Kingdom to establish a global R&D network. It also concentrated its capabilities in securing the foundation as a global brand, by building world-class R&D capabilities and production systems. Even in the 2000s, the company maintained its growth as a global company through continued R&D efforts by securing its production and quality capabilities, supplying tires for new models to Mercedes, Benz, Volkswagen and other global auto manufacturers.

3.3 Implementation of radio-frequency identification technology

RFID is radio-frequency identification technology to recognize stored information by using a magnetic carrier wave. RFID tags can be either passive, active or battery-assisted passive (BAP). An active tag has an on-board battery and periodically transmits its ID signal. A BAP has a small battery on board and is activated when in the presence of an RFID reader. A passive tag is cheaper and smaller because it has no battery; instead, the tag uses the radio energy transmitted by the reader. However, to operate a passive tag, it must be illuminated with a power level roughly a thousand times stronger than for signal transmission. That makes a difference in interference and in exposure to radiation.

an integrated circuit for storing and processing information, modulating and demodulating a radio frequency signal, collecting DC power from the incident reader signal, and other specialized functions; and

an antenna for receiving and transmitting the signal.

capable of recognizing information without contact;

capable of recognizing information regardless of the direction;

capable of reading and saving a large amount of data;

requires less time to recognize information;

can be designed or manufactured in accordance with the system or environmental requirements;

capable of recognizing data unaffected by contamination or the environment;

not easily damaged and cheaper to maintain, compared with the bar code system; and

tags are reusable.

3.3.1 Phase 1. Background of exploitation of radio-frequency identification (2005-2010).

Despite rapid growth of K Tire since 1960, K Tire ranked at the 13th place in the global market (around 2 per cent of the global market share) as of 2012. To enlarge global market share is desperate homework. K Tire was indispensable to develop the discriminated technologies. When bar code system commonly used by the competitors, and the industry leaders, K Tire had a decision for adoption of RFID technology instead of bar code system for tires as a first mover strategy instead of a late comer with regard to manufacture tires for personal vehicle. In fact, K Tire met two kinds of hardship. Among the top 20, the second-tier companies with market shares of 1-2 per cent are immersed in fiercer competitions to advance their ranks. The fierceness of the competition is reflected in the fact that of the companies ranked between the 11th and 20th place, only two maintained their rank from 2013.

With the demand for stricter product quality control and manufacture history tracking expanding among the auto manufacturers, tire manufacturers have come to face the need to change their way of production and logistics management. Furthermore, a tire manufacturer cannot survive if it does not properly respond to the ever stricter and exacting demand for safe passenger vehicle tires of higher quality from customers and auto manufacturers. As mentioned above, K Tire became one of the top 10 companies in the global markets, recording fast growth until the early 2000. During this period, K Tire drew the attention of the global markets with a series of new technologies and innovative technologies through active R&D efforts. Of those new products, innovative products – such as ultra-high-performance tires – led the global markets and spurred the company’s growth. However, into the 2010s, the propriety of the UHP tire technology was gradually lost, and the effect of the innovation grew weaker as the global leading companies stepped forward to take the reign in the markets. Subsequently, K Tire suffered from difficulties across its businesses, owing to the failure to develop follow-up innovative products or market-leading products, as well as the aggressive activities by the company’s hardline labor union. Such difficulties pushed K Tire down to the 13th position in 2014, which sparked the dire need to bring about innovative changes within the company.

3.3.2 Phase 2. Ceaseless endeavor and its failure (2011-2012).

It needs to be lightweight : An RFID tag attached inside a vehicle may adversely affect the weight balance of the tires. A heavier tag has greater adverse impact on the tire performance. Therefore, a tag needs to be as light as possible.

It needs to be durable : Passenger vehicle tires are exposed to extensive bending and stretching, as well as high levels of momentum, which may damage a tag, particularly causing damage to or even loss of the antenna section.

It needs to maintain adhesiveness : Tags are attached on the inner surface, which increase the possibility of the tags falling off from the surface while the vehicle is in motion.

It needs to be resistant to high temperature and high pressure : While going through the tire manufacture process, a tag is exposed to a high temperature of around 200°C and high pressure of around 30 bars. Therefore, a tag should maintain its physical integrity and function at such high pressure and temperature.

It needs to be less costly : A passenger vehicle tire is smaller, and therefore cheaper than truck/bus tires. As a result, an RFID tag places are greater burden on the production cost.

Uncountable tag prototypes, were applied to around 200 test tires in South Korea for actual driving tests. Around 150 prototypes were sent to extremely hot regions overseas for actual driving tests. However, the driving tests revealed damage to the antenna sections of the tags embedded in tires, as the tires reached the end of their wear life. Also, there was separation of the embedded tags from the rubber layers. This confirmed the risk of tire separation, resulting in the failure of the tag development attempt.

3.3.3 Phase 3. Success of adoption RFID (2013-2014).

Despite the numerous difficulties and failures in the course of development, the company ultimately emerged successful, owing to its institutional entrepreneurship and corporate entrepreneurship the government’s support. Owing to the government-led support project, K Tire resumed its RFID development efforts in 2011. This time, the company discarded the idea of the embedded-type tag, which was attempted during the first development. Instead, the company turned to attached-type tag. The initial stages were marked with numerous failures: the size of a tag was large at 20 × 70 mm, which had adverse impact on the rotation balance of the tires, and the attached area was too large, causing the attached sections to fall off as the tire stretched and bent. That was when all personnel from the technical, manufacturing, and logistics department participated in creating ideas to resolve the tag size and adhesiveness issues. Through cooperation across the different departments and repeated tests, K Tire successfully developed its RFID tag by coming up with new methods to minimize the tag size to its current size (9 × 45 mm), maintain adhesiveness and lower the tag price. Finally, K Tire was success the adoption RFID.

3.3.4 Phase 4. Establishment of the manufacture, logistics and marketing tracking system.

Whenever subtle and problematic innovation difficulties arise, every worker and board member moves forward through networking and knowledge sharing within intra and external.

While a bar code is only capable of storing the information on the nationality, manufacturer and category of a product, an RFID tag is capable of storing a far wider scope of information: nationality, manufacturer, category, manufacturing date, machines used, lot number, size, color, quantity, date and place of delivery and recipient. In addition, while the data stored in a bar code cannot be revised or expanded once the code is generated, an RFID tag allows for revisions, additions and removal of data. As for the recognition capability, a bar code recognizes 95per cent of the data at the maximum temperature of 70°C. An RFID tag, on the other hand, recognizes 99.9 per cent of the data at 120°C.

The manufacture and transportation information during the semi-finished product process before the shaping process is stored in the RFID tags, which is attached to the delivery equipment to be provided to the MLMTS;

Logistics Products released from the manufacture process are stored in the warehouses, to be released and transported again to logistics centers inside and outside of South Korea. The RFID tags record the warehousing information, as the products are stored into the warehouses, as well as the release information as the products are released. The information is instantly delivered to the MLMTS;

As a marketing, the RFID tags record the warehousing information of the products supplied and received by sales branches from the logistics centers, as well as the sales information of the products sold to consumers. The information is instantly delivered to the MLMTS; and

As a role of integrative Server, MLM Integrative Server manages the overall information transmitted from the infrastructures for each section (production information, inventory status and release information, product position and inventory information, consumer sales information, etc.).

The MLMTS provides the company with various systemic functions to integrate and manage such information: foolproof against manufacture process errors, manufacture history and quality tracking for each individual product, warehousing/releasing and inventory status control for each process, product position control between processes, real-time warehouse monitoring, release control and history information tracking across products of different sizes, as well as link/control of sales and customer information. To consumers, the system provides convenience services by providing production and quality information of the products, provision of the product history through full tracking in the case of a claim, as well as a tire pressure monitoring system:

“South korea’s K Tire Co. Inc. has begun applying radio-frequency identification (RFID) system tags on: half-finished” tire since June 16. We are now using an IoT based production and distribution integrated management system to apply RFID system on our “half-finished products” the tire maker said, claiming this is a world-first in the industry. The technology will enable K Tire to manage products more efficiently than its competitors, according to the company. RFID allows access to information about a product’s location, storage and release history, as well as its inventory management (London, 22, 2015 Tire Business).

4. Discussions

Originally, aims of RFID adoption for passenger car “half-finished product” is to chase the front runners, Hankook Tire in Korea including global leading companies like Bridgestone, Michaelin and Goodyear. In particular, Hankook Tire, established in 1941 has dominated domestic passenger tire market by using the first mover’s advantage. As a late comer, K Tire needs distinguishable innovation strategy which is RFID adoption for passenger car’s tire, “half-finished product” to overcome shortage of number of distribution channels. Adoption of RFID technology for passenger car’s tire has been known as infeasible methodologies according to explanation by Changmin Park, vice-CTO (chief technology officer) until K Tire’s success.

We lensed success factors as three perspectives; institutional entrepreneurship, corporate entrepreneurship and innovation. First, as a corporate entrepreneurship perspective, adopting innovative technologies having uncertainties accompanies by a certain risk of failure. Corporate entrepreneurship refers to firm’s effort that inculcate and promote innovation and risk taking throughout its operations ( Burgelman, 1983 ; Guth and Ginsberg, 1990 ). K Tire’s success was made possible by overcome the uncountable difficulties based on shared value and norms (e.g. Fligstein and Mara-Drita, 1996 ; Garud et al. , 2002 ; Hargadon and Douglas, 2001 ; Maguire et al. , 2004 ).

An unsuccessful attempt at developing innovative technologies causes direct loss, as well as loss of the opportunity costs. This is why many companies try to avoid risks by adopting or following the leading companies’ technologies or the dominant technologies. Stimulating corporate entrepreneurship requires firms to acquire and use new knowledge to exploit emerging opportunities. This knowledge could be obtained by joining alliances, selectively hiring key personnel, changing the composition or decision-making processes of a company’s board of directors or investing in R&D activities. When the firm uses multiple sources of knowledge ( Branzei and Vertinsky, 2006 ; Thornhill, 2006 ), some of these sources may complement one another, while others may substitute each other ( Zahra and George, 2002 ). Boards also provide managers with appropriate incentives that better align their interests with those of the firm. Given the findings, K Tire seeks new knowledge from external organizations through its discriminative corporate entrepreneurship.

When adopting the RFID system for its passenger vehicle tires, K Tire also had to develop new RFID tags suitable for the specific type of tire. The company’s capabilities were limited by the surrounding conditions, which prevented the application of existing tire RFID tag technologies, such as certain issues with the tire manufacturing process, the characteristic of its tires and the price of RFID tags per tire. Taking risks and confronting challenges are made from board member’s accountability. From the findings, we find that entrepreneurship leadership can be encouraged in case of within the accountability frame work.

Despite its status as a second-tier company, K Tire attempted to adopt the RFID system to its passenger vehicle tires, a feat not achieved even by the leading companies. Thus, the company ultimately built and settled the system through numerous trials and errors. Such success was made possible by the entrepreneurship of K Tire’s management, who took the risk of failure inherent in adopting innovative technologies and confronting challenges head on.

Second, institutional entrepreneurship not only involves the “capacity to imagine alternative possibilities”, it also requires the ability “to contextualize past habits and future projects within the contingencies of the moment” if existing institutions are to be transformed ( Emirbayer and Mische, 1998 ). New technologies, the technical infrastructure, network activities to acquire the new knowledge, learning capabilities, creating a new organization such as Pioneer Lab and new rules to create new technologies are the features. To qualify as institutional entrepreneurs, individuals must break with existing rules and practices associated with the dominant institutional logic(s) and institutionalize the alternative rules, practices or logics they are championing ( Garud and Karnøe, 2003 ; Battilana, 2006 ). K Tire established new organization, “Special lab” to obtain the know technology and information as CEO’s direct sub-committees. Institutional entrepreneurship arise when actors, through their filed position, recognize the opportunity circumstance so called “norms” ( Battilana et al. , 2009 ). To make up the deficit of technologies for RFID, knowledge stream among workers is more needed. Destruction of hierarch ranking system is proxy of the institutional entrepreneurship. Also, K Tire has peculiar norms. Namely, if one requires the further study such as degree course or non-degree course education services, grant systems operated via short screen process. Third, as innovation perspectives, before adopting the RFID system, the majority of K Tire’s researchers insisted that the company use the bar code technology, which had been widely used by the competitors. Such decision was predicated on the prediction that RFID technology would see wider use in the future, as well as the expected effect coming from taking the leading position, with regard to the technology.

Finally, K Tire’s adoption of the RFID technology cannot be understood without government support. The South Korean government has been implementing the “Verification and Dissemination Project for New u-IT Technologies” since 2008. Owing to policy support, K Tire can provide worker with educational service including oversea universities.

5. Conclusions and implications

To cope with various technological impasses, K Tire demonstrated the importance of institutional and corporate entrepreneurship. What a firm pursues more positive act for innovation is a research question.

Unlike firms, K Tire has strongly emphasized IT technology since establishment in 1960. To be promotion, every worker should get certification of IT sectors after recruiting. This has become the firm’s norm. This norm was spontaneously embedded for firm’s culture. K Tire has sought new ICT technology become a first mover. This norm can galvanize to take risk to catch up the first movers in view of institutional entrepreneurship.

That can be cultivated both by corporate entrepreneurship, referred to the activities a firm undertakes to stimulate innovation and encourage calculated risk taking throughout its operations within accountabilities and institutional entrepreneurship, referred to create its own peculiar norm. Contribution of our paper shows both importance of board members of directors in cultivating corporate entrepreneurship and importance of norm and rules in inducing institutional entrepreneurship.

In conclusion, many of them were skeptical about adopting RFID for its passenger vehicle tires at a time when even the global market and technology leaders were not risking such innovation, citing reasons such as risk of failure and development costs. However, enthusiasm and entrepreneurship across the organization towards technical innovation was achieved through the experience of developing leading technologies, as well as the resolve of the company’s management and its institutional entrepreneurship, which resulted in the company’s decision to adopt the RFID technology for small tires, a technology with unverified effects that had not been widely used in the markets. Introduction of new organization which “Special lab” is compelling example of institutional entrepreneurship. Also, to pursue RFID technology, board members unanimously agree to make new organization in the middle of failing and unpredictable success. This decision was possible since K Tire’s cultivated norm which was to boost ICT technologies. In addition, at that time, board of director’s behavior can be explained by corporate entrepreneurship.

From the findings, this paper also suggests importance of firms’ visions or culture from startup stage because they can become a peculiar norm and become firm’s institutional entrepreneurship. In much contemporary research, professionals and experts are identified as key institutional entrepreneurs, who rely on their legitimated claim to authoritative knowledge or particular issue domains. This case study shows that authoritative knowledge by using their peculiar norm, and culture as well as corporate entrepreneurship.

This paper has some limitations. Despite the fact that paper shows various fruitful findings, this study is not free from that our findings are limited to a single exploratory case study. Overcoming such limitation requires securing more samples, including the group of companies that attempt unprecedented innovations across various industries. In this paper, we can’t release all findings through in-depth interview and face-to-face meetings because of promise for preventing the secret tissues.

Nevertheless, the contribution of this study lies in that it shows the importance of corporate entrepreneurship and institutional entrepreneurship for firm’s innovative capabilities to grow ceaselessly.

Integrated frame of analysis

Aldrich , H.E. and Fiol , C.M. ( 1994 ), “ Fools rush in? The institutional context of industry creation ”, Academy of Management Review , Vol. 19 No. 4 , pp. 645 - 670 .

Aldrich , H.E. and Martinez , M.A. ( 2001 ), “ Many are called, but few are chosen: an evolutionary perspective for the study of entrepreneurship ”, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice , Vol. 25 No. 4 , pp. 41 - 57 .

Battilana , J. ( 2006 ), “ Agency and institutions: the enabling role of individuals’ social position ”, Organization , Vol. 13 No. 5 , pp. 653 - 676 .

Battilana , J. , Leca , B. and Boxenbaum , E. ( 2009 ), “ How actors change institutions: towards a theory of institutional entrepreneurship ”, The Academy of Management Annals , Vol. 3 No. 1 , pp. 65 - 107 .

Branzei , O. and Vertinsky , I. ( 2006 ), “ Strategic pathways to product innovation capabilities in SMEs ”, Journal of Business Venturing , Vol. 21 No. 1 , pp. 75 - 105 .

Burgelman , R.A. ( 1983 ), “ A model of the interaction of strategic behavior, corporate context, and the context of strategy ”, Academy of Management Review , Vol. 8 No. 1 , pp. 61 - 70 .

Capon , N. , Farley , J.U. and Hoenig , S. ( 1990 ), “ Determinants of financial performance: a meta-analysis ”, Management Science , Vol. 36 , pp. 1143 - 1159 .

Covin , J. and Miles , M. ( 1999 ), “ Corporate entrepreneurship and the pursuit of competitive advantage ”, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice , Vol. 23 , pp. 47 - 63 .

D’Aveni , R.A. ( 1994 ), Hyper-competition: Managing the Dynamics of Strategic Maneuvering . Free Press , New York, NY .

DiMaggio , P.J. ( 1988 ), “ Interest and agency in institutional theory ”, in Zucker , L.G. (Ed.), Institutional Patterns and Organizations , Ballinger , Cambridge, MA .

Emirbayer , M. and Mische , A. ( 1998 ), “ What is agency? ”, American Journal of Sociology , Vol. 103 , pp. 962 - 1023 .

Fligstein , N. ( 1997 ), “ Social skill and institutional theory ”, American Behavioral Scientist , Vol. 40 , pp. 397 - 405 .

Fligstein , N. and Mara-Drita , I. ( 1996 ), “ How to make a market: reflections on the attempt to create a single market in the European Union ”, American Journal of Sociology , Vol. 102 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 33 .

Garud , R. and Karnøe , P. ( 2003 ), “ Bricolage versusbreakthrough: distributed and embedded agency in technology entrepreneurship ”, Research Policy , Vol. 32 , pp. 277 - 300 .

Garud , R. , Jain , S. and Kumaraswamy , A. ( 2002 ), “ Institutional entrepreneurship in the sponsorship of common technological standards: the case of sun microsystems and Java ”, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 45 No. 1 , pp. 196 - 214 .

Guth , W. and Ginsberg , A. ( 1990 ), “ Guest editors’ introduction: corporate entrepreneurship ”, Strategic Management Journal , Vol. 11 , pp. 5 - 15 .

Hargadon , A.B. and Douglas , Y. ( 2001 ), “ When innovations meet institutions: Edison and the design of the electric light ”, Administrative Science Quarterly , Vol. 46 No. 3 , pp. 476 - 502 .

Hisrich , R.D. ( 1986 ), Entrepreneurship, Intrapreneurship and Venture Capital , Lexington Books , MA .

Hoffman , A.J. ( 1999 ), “ Institutional evolution and change: environmentalism and the US chemical industry ”, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 42 No. 4 , pp. 351 - 371 .

Jennings , D.F. and Lumpkin , J.R. ( 1989 ), “ Functioning modeling corporate entrepreneurship: an empirical integrative analysis ”, Journal of Management , Vol. 15 , pp. 485 - 502 .

Jepperson , R. and Meyer , J. ( 2001 ), “ The ‘actors’ of modern society: the cultural construction of social agency ”, Sociological Theory , Vol. 18 , pp. 100 - 120 .

Kirzner , I.M. ( 1997 ), “ Entrepreneurial discovery and the competitive market process: an Austrian approach ”, Journal of Economic Literature , Vol. 35 No. 1 , pp. 60 - 85 .

Kuratko , D. ( 2007 ), Corporate Entrepreneurship: Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship , Cambridge, MA .

Lawrence , T.B. , Hardy , C. and Phillips , N. ( 2002 ), “ Institutional effects of inter-organizational collaboration: the emergence of proto-institutions ”, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 45 No. 1 , pp. 281 - 290 .

Lumpkin , G.T. and Dess , G.G. ( 1996 ), “ Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance ”, Academic. Management Review , Vol. 21 , pp. 135 - 172 .

Maguire , S. , Hardy , C. and Lawrence , T.B. ( 2004 ), “ Institutional entrepreneurship in emerging fields: HIV/AIDS treatment advocacy in Canada ”, The Academy of Management , Vol. 47 No. 5 , pp. 657 - 679 .

Meyer , J.W. , Boli , J. and Thomas , G.M. ( 1994 ), “ Ontology and rationalization in the western cultural account ”, in Richard Scott , W. and Meyer , J.W. (Eds), Institutional Environments and Organizations: Structural Complexity and Individualism , Sage Publications , Thousand Oaks, CA , pp. 9 - 27 .

North , D.C. ( 1990 ), Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance , Cambridge University Press , Cambridge .

Phan , P.H. , Wright , M. , Ucbasaran , D. and Tan , W.L. ( 2009 ), “ Corporate entrepreneurship: current research and future directions ”, Journal of Business Venturing , Vol. 29 , pp. 197 - 205 .

Rojas , F. ( 2010 ), “ Power through institutional work: acquiring academic authority in the 1968 third world strike ”, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 53 No. 6 , pp. 1263 - 1280 .

Srivastava , A. and Lee , H. ( 2005 ), “ Predicting order and timing of new product moves: the role of top management in corporate entrepreneurship ”, Journal of Business Venturing , Vol. 20 No. 1 , pp. 459 - 481 .

Schumpeter , J.A. ( 1942 ), Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy , Harper and Brothers , New York, NY .

Scott , R. ( 1995 ), Institutions and Organizations , Sage , Thousand Oaks, CA .

Shane , S. and Venkataraman , S. ( 2000 ), “ The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research ”, Academy of Management Review , Vol. 25 No. 1 , pp. 217 - 226 .

Teece , D.J. ( 2014 ), “ The foundations of enterprise performance: dynamic and ordinary capabilities in an (economic) theory of firms ”, Academy of Management Perspectives , Vol. 28 No. 4 , pp. 328 - 352 .

Thornhill , S. ( 2006 ), “ Knowledge, innovation and firm performance in high- and low-technology regimes ”, Journal of Business Venturing , Vol. 21 No. 5 , pp. 687 - 703 .

Tidd , J. and Bessant , J. ( 2009 ), Managing Innovation: Integrating Technological, Market and Organizational Change , 4th ed. , John Wiley & Sons , Sussex .

Tushman , M.L. and Anderson , P. ( 1986 ), “ Technological discontinuities and organizational environments ”, Administrative Science Quarterly , Vol. 31 No. 3 , pp. 439 - 465 .

Townley , B. ( 2002 ), “ The role of competing rationalities in institutional change ”, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 45 No. 1 , pp. 163 - 179 .

Yin , R.K. ( 2008 ), Case Study Research: Design and Methods (Applied Social Research Methods) , 4th ed. , Sage, Thousand Oaks , CA .

Zahra , S.A. ( 1991 ), “ Predictors and financial outcomes of corporate entrepreneurship: an exploratory study ”, Journal of Business Venturing , Vol. 6 , pp. 259 - 285 .

Zahra , S.A. ( 1996 ), “ Governance, ownership, and corporate entrepreneurship: the moderating impact of industry technological opportunities ”, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 39 No. 6 , pp. 1713 - 1735 .

Zahra , S.A. and George , G. ( 2002 ), “ Absorptive capacity: a review, reconceptualization, and extension ”, Academy of Management Review , Vol. 27 , pp. 185 - 203 .

Further reading

Bresnahan , T.F. , Brynjolfsson , E. and Hitt , L.M. ( 2002 ), “ Information technology, workplace organization, and the demand for skilled labor: firm-level evidence ”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics , Vol. 117 No. 1 , pp. 339 - 376 .

DiMaggio , P.J. ( 1984 ), “ Institutional isomorphism and structural conformity ”, paper presented at the 1984 American Sociological Association meetings, San Antonio, Texas .

Garud , R. ( 2008 ), “ Conferences as venues for the configuration of emerging organizational fields: the case of cochlear implants ”, Journal of Management Studies , Vol. 45 No. 6 , pp. 1061 - 1088 .

Maguire , S. and Hardy , C. ( 2009 ), “ Discourse and deinstitutionalization: the decline of DDT ”, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 52 No. 1 , pp. 148 - 178 .

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by 2017 Hongik University Research Fund.

Corresponding author

Related articles, we’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

- Technology Ethics Cases

- Markkula Center for Applied Ethics

- Focus Areas

- Technology Ethics

- Technology Ethics Resources

Find case studies illustrating dilemmas in technology and ethics.

Case studies are also available on Internet Ethics .

For permission to reprint cases, submit requests to [email protected] .

Looking to draft your own case studies? This template provides the basics for writing ethics case studies in technology (though with some modification it could be used in other fields as well).

AI-generated text, voices, and images used for entertainment productions and impersonation raise ethical questions.

Ethical questions arise in interactions among students, instructors, administrators, and providers of AI tools.

Which stakeholders might benefit from a new age of VR “travel”? Which stakeholders might be harmed?

Case study on the history making GameStop short and stock price surge that occurred during January 2021.

As PunkSpider is pending re-release, ethical issues are considered about a tool that is able to spot and share vulnerabilities on the web, opening those results to the public.

With URVR recipients can capture and share 360 3D moments and live them out together.

VR rage rooms may provide therapeutic and inexpensive benefits while also raising ethical questions.

A VR dating app intended to help ease the stress and awkwardness of early dating in a safe and comfortable way.

Ethical questions pertaining to the use of proctoring software in online teaching.

Concern is high over possible misuses of new AI technology which generates text without human intervention.

- More pages:

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Community case study article, communicating science, technology, and environmental issues: a case study of an intercultural learning experience.

- 1 Building Services Engineering, Paper and Packaging Technology and Print and Media Technology, Munich University of Applied Science (HM–Hochschule München), Munich, Germany

- 2 Environmental Studies, State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry (ESF), Syracuse, NY, United States

This science communication case study analyzes an online international co-taught course where students practiced blog article conceptualization and production covering a wide variety of science and technology related issues. Students had an international experience during the COVID-19 pandemic, and gained experience in communicating science and technology to intercultural audiences. Through student article reviews, course evaluations and project reflections students demonstrated an adoption of new science communication skills and some key examples of changing perspective on issues such as environment and technology. They also enjoyed the opportunity to learn about new cultures, reflect on their own, and bond over life experiences.

Introduction

The study of science has played a pivotal role in the development of the human species. Scientific inquiry has advanced all facets of understanding of both human and biophysical systems, including medicine, astrophysics, war, and ecology. Science focuses on empirical studies to gain knowledge ( Morrison et al., 2008 ). The concept of truth in the positivist philosophy of science is often seen as one without the taint of the subjective, which seeks truth through objectivity and logical empiricisms ( Lincoln and Guba, 1985 ; Morrison et al., 2008 ). Though the positivist paradigm is still present in the scientific community, others have adopted research paradigms more suited to their field of study, including the postpositivist philosophy of science ( Lincoln and Guba, 1985 ). This paradigm attempts to rectify the problems of the positivist paradigm by recognizing an absence of a single, shared reality. Therefore, the scientific method has gone through many incarnations (i.e., inductive, deductive, and retroductive reasoning) to the now widely accepted hypothetico-deductive method, the scientific approach developed by Karl Popper (1902–1994) which includes hypothesis development, usually through the process of retroduction, and hypothesis testing to determine if it can be falsified ( Morrison et al., 2008 ). With an ever more rigorous approach to conducting research, scientific findings are more difficult to dispute by those outside a specific area of knowledge and are therefore given higher value in decision-making processes. This tendency toward trust of expert knowledge by outsiders does not, however, eliminate political debate or general speculation of scientific findings ( Cox, 2006 ), using climate change and COVID-19 as two unfortunate examples.

Science as a multifaceted institution consisting of various fields and approaches is not monolithic, but is sometimes treated as such (e.g., not recognizing disciplinary boundaries or the presence of different research paradigms). Furthermore, it is spoken in tandem with other disciplines such as technology, engineering, and math, hence the common usage of STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) to describe fields of similar thought and structure. While a generalized public might have vague conceptualizations of science, the scientific process and the various fields included, studies have shown that levels of scientific knowledge on a variety of topics differ ( Takahashi and Tandoc, 2016 ). Interdisciplinary fields such as science and technology studies as well as science and environmental communication face the problem of translating the ever evolving research and states of knowledge to diverse audiences, some of which might question scientific findings because of value systems, politics or worldviews ( Cann and Raymond, 2018 ). Science, including climate change science, calls for action upon what is a problem with anthropogenic causes. This science is the harbinger of change through policy and personal action, carrying the baggage of chances and gains as well as risks and threats on local and global level ( Dunlap and McCright, 2011 ; Cann and Raymond, 2018 ). Hence, such scientific findings are called into question.

While science communicators struggle to break down the intricacies of scientific thought and research for the public, some sectors of society feel “left out” by science communication and not a part of scientific discussions ( Dawson, 2019 ; Humm et al., 2020 ). As Humm et al. (2020) state, “Science communication only reaches certain segments of society. Various underserved audiences are detached from it and feel left out, which is a challenge for democratic societies that build on informed participation in deliberative processes” (p. 164). Attempts to rectify this include increased efforts in research dissemination, outreach, and public participation. Organizations such as the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF), the ninth European Research and Innovation Framework ( Horizon Europe Strategic Plan, 2021 ), and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research have attempted to bolster actions around science communication in the hopes of greater social impact (U.S. National Science Foundation, (n.d.); Wissenschaftsbaromenter, 2020 ; Handlungsperspektiven, 2021 ).

In an attempt to meet these challenges head on, university curriculums are putting forth classes that are designed to teach and give practice to students communicating about science, technology, and environments ( Rose et al., 2020 ). Traditionally, researchers and students in science-based disciplines focus on writing according to scientific requirements and styles ( Martinez-Conde, 2016 ). Writing for the public is not part of most science education programs ( Brownell et al., 2013 ) and understandable so, regarding academic career-paths that are highly specialized, competitive, and based on peer-appreciation, not publicity. However, communicating effectively with and conveying scientific findings to the public is obviously a major challenge for political systems based on deliberation, participation, and democratic processes. Communication about climate change, risk assessment for new technologies such as artificial intelligence, and COVID-19 (e.g., Honora et al., 2022 ) are examples for this challenge. Thus, efforts have been made worldwide and in a broad variety of formats to train science students to engage with non-scientific audiences and communicate more actively and effectively ( Mercer-Mapstone and Kuchel, 2015 ; Baram-Tsabari and Lewenstein, 2017 ). But despite these efforts, a recent experimental assessment of science communication formats indicates that even well-developed and proliferated trainings do not match expectations, suggesting that “trainees need more repetition putting what they have learned cognitively into practice” and “require more opportunities to apply their conceptual knowledge to a greater diversity of communication tasks” ( Rubega et al., 2020 , 25).

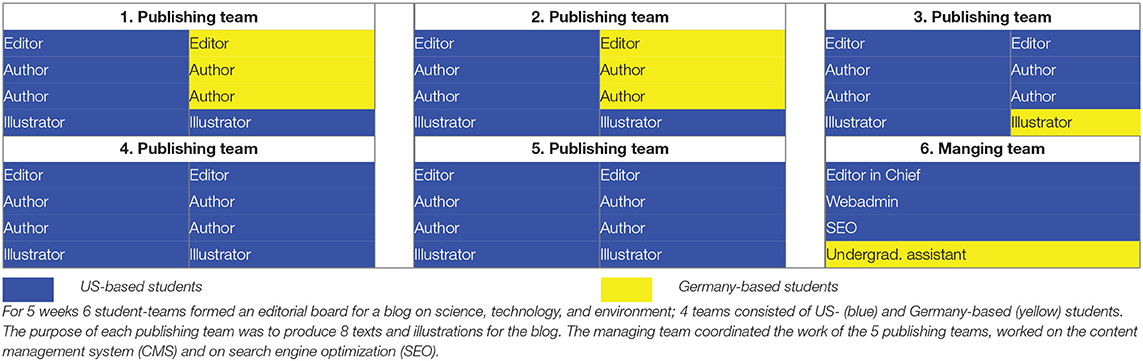

Rubega et al. (2020) suggestions as well as Kappel and Holmen's screening and evaluation of science communication aims ( Kappel and Holmen, 2019 ) indicate that one-time trainings and the provision of tool boxes do not suffice to make public communication of science and technology part of researcher's routine. The overarching goal of the international editorial board as classroom-format was to allow students to experience the challenges and opportunities of writing for laypersons and to encourage them to perceive it not as additional demand, but as integral part of their professional and academic work. In detail, objectives regarding students' development of communication competencies included: (1) introducing undergraduate students to standard processes of science writing and journalism including a possibility for “real” publication; (2) forming interdisciplinary (technical writing and environmental science) and intercultural (US-based and Germany-based) teams in times of restricted mobility; (3) gathering experiences in communicating to intercultural audiences and motivating students to continue their efforts in publicly accessible science communication beyond the course. In addition (4), we included objectives toward organizational and curriculum development.

Case Study Description

Program description.

The “techtalkers”-editorial department as an international classroom-format was part of the pilot phase of the “UAS7 Virtual Academy”, whose objective is to bring together students from the seven leading German Universities of Applied Sciences (UAS7) and from the State University of New York, USA, in joint teaching experiences. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, virtual teaching was used to collaborate, teach, and provide students with an international learning experience. The overall goal of the Virtual Academy was to lay the foundations for future digital collaboration formats. Modules within the Academy covered a broad range from six academic disciplines, including Business Administration, Agricultural Sciences and Landscape Architecture, and Computer Sciences.