- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What the Case Study Method Really Teaches

- Nitin Nohria

Seven meta-skills that stick even if the cases fade from memory.

It’s been 100 years since Harvard Business School began using the case study method. Beyond teaching specific subject matter, the case study method excels in instilling meta-skills in students. This article explains the importance of seven such skills: preparation, discernment, bias recognition, judgement, collaboration, curiosity, and self-confidence.

During my decade as dean of Harvard Business School, I spent hundreds of hours talking with our alumni. To enliven these conversations, I relied on a favorite question: “What was the most important thing you learned from your time in our MBA program?”

- Nitin Nohria is the George F. Baker Jr. and Distinguished Service University Professor. He served as the 10th dean of Harvard Business School, from 2010 to 2020.

Partner Center

Learning Outcomes and Training Satisfaction: A Case Study of Blended Customization in Professional Training

- Original research

- Open access

- Published: 09 September 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Sara Torre ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0001-7399-6692 1 , 2 ,

- Antonio Ulloa Severino 2 &

- Maria Beatrice Ligorio 1

612 Accesses

Explore all metrics

In the case of training programs for workplace settings, design customization can help trainers to better address trainees’ needs and, at the same time, it can help them build a sense of competence and autonomy. This is particularly difficult when trainees are skeptical because of former failing training experiences. The case study presented here, is about a training program featuring customization design from the pre-training phase throughout the training process, aimed precisely at trainees with previous negative experiences. Eighteen participants (M: 10; F: 8; age average: 55,7) were involved in training senior professionals in the information communication technology (ICT) field, all of them with a history of failed training attempts and a long period of workplace inactivity. In preparation for the training, the trainers gathered information about trainees’ attitude towards training, training preferences, and baseline skills, which determined the training design. During training, feedback and intermediate learning results were considered for fine tuning. Results attested the change of attitude towards training, perceived enhancement of self-awareness, feelings of being part of a community, and successful learning outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Flexibility in Formal Workplace Learning: Technology Applications for Engagement through the Lens of Universal Design for Learning

Learning experience design (LXD) professional competencies: an exploratory job announcement analysis

Process is king: evaluating the performance of technology-mediated learning in vocational software training, explore related subjects.

- Digital Education and Educational Technology

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The need in information communication technology (ICT) organizations to efficiently update internal technical and organizational skills leads to engagement with training providers specialized in professional training. As it often is the case, the main contractor of the training program—a human resources manager, a training manager, or an executive manager—reaches out to the training provider with a plethora of needs and goals. These needs and goals could deal with a large array of issues such as organizational strategies of human resources development (Hughey & Mussnug, 1997 ), employee’s satisfaction improvement and professional fulfillment (Shen & Tang, 2018 ), and workers’ productivity expansion (Niazi, 2011 ). In other words, a company may ask for a training intervention to invest in staff development, to answer environmental challenges, or to rectify perceived shortcomings in the skill asset of the company (Isiaka, 2011 ).

Oftentimes, the company requesting a training program seeks for a training design compliant mainly with the needs expressed by the management without really considering the trainees’ needs (Morrison, 2021 ). For instance, management may assume that a training program should be implemented in a face-to-face setting to guarantee participants’ engagement, and explicitly request an in-presence training program. At the same time, employees may perceive training as a source of fatigue due to the stress of commuting and interrupting their routine and prefer online training. In other words, management’s proposals could heavily influence the training design and program. Training needs analysis in organizations can also be prominently affected by organizational politics because of conflict and power relations (Clarke, 2003 ). Therefore, compliance to management is not sufficient to conceive an effective design, as the training context and the recent research should also be considered. Successful training can be achieved through awareness of organizational culture, individual characteristics of the trainees and baseline skills (Tracey & Tews, 1995 ).

In addition, to the best of our knowledge, oftentimes training programs in corporate settings are not designed to build on the most recent innovation reported in scientific literature on education and learning (Pavliuk et al., 2017 ). While training programs based on documented theoretical background and outcomes are implemented in healthcare fields (Richmond et al., 2017 ) and school settings (Luneta, 2012 ), small and mid-sized training practitioners may lack the resources to base their practice on learning models or to share their findings and innovations with the community.

In synthesis, two types of interlinked concerns emerge about training programs for corporations. Firstly, they rarely consider the specific requirements of each organizational context and learning group, favoring management’s guidelines; secondly, they tend not to draw inspiration from research nor to produce scientific publications.

Training companies can overcome these limitations. They surely can consider the management’s requirements, but at the same time their professionality is based on the evidence coming from the specialized literature in any phase of the training program. The case we present here, originated when an ICT company was looking for a customized blended training program. The reason declared by the management was to re-skill the inactive workers and to be able to employ them in the company’s future projects. After considering management’s goals and benchmarks, the training planners developed a learning model inspired by recent approaches highlighting the ability to adapt to the training participants (Alamri et al., 2021 ). From a review—presented in the subsequent section—emerges the relevance of on-going adaptation to the individual trainees. In our case, a distinctive feature was added. The training program was designed to personalize methods and contents coherently with preliminary information, shaping the training intervention already before it started. As a result, a blended learning environment was set up, able to intercept and implement trainees’ needs throughout the course. The continuous fine-tuning of the training program was based on learning analytics and participant’s feedback.

In the next sections, we will first report a short review on the most used theoretical background and approaches in designing personalized professional training; right after, we will present our case stressing its peculiarities such as the pre-customization and the results obtained.

2 Theoretical Background

Personalized learning management systems (LMS) can support accessing learning resources (Dolog et al., 2004 ) and promoting a sustainable learning environment (Klašnja-Milićević & Ivanovi, 2021 ). Even with these advantages, training personalization is still under-utilized within workforce training (Fake & Dabbagh, 2020 ). Oftentimes, personalization and customization are used interchangeably to describe a form of platform or content adaptation to learners in an e-learning setting (Marappan & Bhaskaran, 2022 ). Only a few studies focus on the effectiveness of personalization versus customization, describing personalization as a process that requires feature adaptation to the users’ needs, while customization directly involves users’ choice (Zo, 2003 ). Personalization is a top-down process where the digital platform or the training program is adapted to participants’ characteristics by a system or an operator (Sundar & Marathe, 2010 ). On the other hand, customization is a bottom-up process that allows users to directly impact the digital platform and training program by expressing their preferences (Sundar & Marathe, 2010 ). A major advantage of customization, when compared to personalization, is the perceived control (Zo, 2003 ) and engagement participants can experience after the customization experience (Zine et al., 2014 ). Training customization was mostly explored in academic contexts (Zine et al., 2014 ; Zo, 2003 ), providing relevant information about the effects of training customization. Nevertheless, the perception of training in an academic setting can differ quite a bit from its perception in a business setting (Fayyoumi, 2009 ).

Learning analytics can be implemented into educational environments for the purpose of being utilized by instructors, learning designers and students (Reigeluth & Beatty, 2016 ; Wise & Vytasek, 2017 ). For example, learning analytics can be used for personalizing feedback and course design (Gong et al., 2018 ; Yilmaz & Yilmaz, 2020 ). When it comes to customization, learning analytics can drive learning program customization in two ways (Wise & Vytasek, 2017 ): through adaptive learning analytics (Brooks et al., 2014 ; Brusilovsky & Peylo, 2003 ) or as adaptable learning analytics (Brooks et al., 2014 ). The first approach addresses the design of the learning analytics implementation, while the second lets users determine which analytics will be attended to and how they will influence the learning process. However flexible this last approach may be, Wise and Vytasek ( 2017 ) state that users may be overwhelmed and confused about the uncertainty of the choice. Therefore, user agency has to be supported by the implementation design and by the instructors that are supposed to make decisions aimed at meeting the users’ needs and resources.

Another factor that can influence the learning experience is the formative feedback. Through this factor, personalized assignments can be created and the learning resources are tailored based on trainees’ needs (Knight et al., 2020 ). However, when considering the formative feedback, a much more interactive system is possible (Neville et al., 2005 ). When trainees are able to impact training through feedback, trainers can gather fundamental information about the use of LMS, effectiveness of the training program, students’ relationships (Neville et al., 2005 ), and about the training program acceptance (Feng, 2020 ).

Learning outcomes and training satisfaction are often measured to assess efficacy of training (Armatas et al., 2022 ; Arthur et al., 2003 ; Puška et al., 2021 ). Many dimensions are proven to enhance learning outcomes and training satisfaction. For instance, it has been found that interaction between learners improves learning performance (Wang, 2023 ). In addition, training personalization can increase retention, customer satisfaction, and learner engagement (Kwon & Kim, 2012 ; Kwon et al., 2010 ; Springer, 2014 ).

Finally, it seems useful to define the concept of blended learning (BL) and how the training model adopted in our case can be tailored to fit a trainee's needs. BL is defined by Garrison and Kanuka ( 2004 ) as “the thoughtful integration of classroom face-to-face learning experiences with online learning experiences” (p. 96). As stated by Kaur ( 2013 ), BL can offer trainees “the best of both worlds” because it guarantees training flexibility without missing out face-to-face interactions (p. 5). Indeed, in BL models the advantages of both face-to-face encounters and online platforms are combined and valued (Ligorio & Sansone, 2009 ). However, BL can clash with the trainees’ technological resistance (Prasad et al., 2018 ), especially for adult students (Lightner & Lightner-Laws, 2016 ). This is the reason why this type of user feels hindered their ability to gain access to instructional materials (Rasheed et al., 2020 ) or their ability to learn a new technology. In some cases, the online sections of BL can be burdened by feelings of learning alienation (Chyr et al., 2017 ) and isolation (Lightner & Lightner-Laws, 2016 ). Students may be hesitant in engaging in online learning communities due to lack of non-verbal communication cues in asynchronous activities (Rashed et al., 2020 ), and discomfort in using cameras and microphones for synchronous activities (Szeto & Cheng, 2016 ).

In some training cases, BL can be adapted to the trainee’s characteristics to build a learned-centered training environment (Alamri et al., 2021 ). For example, learning statistics (Çetinkaya, 2016 ) or prior knowledge (Glover & Latif, 2013 ) are used to offer trainees a personalized learning experience (Watson and Watson, 2016 ), purposely selected content (Xie et al., 2019 ), and trainee-specific modeling activities (Amenduni & Ligorio, 2022 ; Amenduni et al., 2021 ). These examples fit the definition of personalized training previously provided, as the training process is adapted by an instructor or a software.

In synthesis, the literature review has revealed that better results in professional training could be obtained by increasing personalization and flexibility, in terms of trainees satisfaction and learning outcomes. This can be surely done by exploiting the opportunities offered by technology—both in terms of LMS features and psycho-pedagogical models. However, these elements are yet to be examined jointly in a work-place training setting. It is also important to consider the timing of personalization implementation within the course. Therefore, the main research question who leads our intervention concerns the effects of introducing an early personalized training in a complex context: What are the advantages and disadvantages of early customization and constant flexibility? This overall research question will be better exploited in the next section.

3 Methodology

3.1 the research question.

As already stated earlier, our overall research question is: What are the effects of early customization and constant flexibility in a training program meant to relocate professionals coming from a complex context? This question arises from the gap in literature concerning the real application of flexible training in a professional setting. Furthermore, our research question aims to explore if the concerns about BL’s risk of learning alienation and isolation in participants can be addressed through customization and flexibility.

To answer this question, the research group focused on two aspects in particular: (a) The early customization and flexibility; as revealed by the literature reviews, most of the training programs consider customization and flexibility from the start to the end of the course. In our case, personalization and flexibility are introduced even before the start of the course, in its planning phase. This was possible because information about the trainees was available, and the trainers used this information to personalize the program; (b) The effects of such customization. In particular, we are interested in the impact of such a course on attitude towards training, perceived enhancement of self-awareness, feelings of belonging to a community, and successful learning outcomes.

3.2 The Trainees' Company

The company involved in the case study presented here, is a leading company in ICT services for digital transformation. Its main activities include the design and implementation of custom end-to-end solutions, cloud environments, digital and operations services. Two years prior to the training program described here, this ICT company acquired a branch of another company, incorporating the majority of the branch’s workers. A consistent number of these workers did not have the opportunity to acquire the technical skills demanded by the new company; therefore, a mismatch was detected between the actually possessed and the required ones. As the ICT company could not employ these workers in its projects, they became inactive and did not take part in company practices. Inactive workers were offered to terminate their contract and receive a congruent severance pay. This proposal led to the involvement of the labor union, who sought after the assurance of rightful treatment for the inactive workers. Nevertheless, most of the inactive workers accepted the proposal of termination and exited the company, while the remaining inactive workers stood their ground and kept their position in the company. This decision of the remaining workers was reportedly caused by two matters: Uncertainty of employment outside the company and impracticability of upgrading their skill set outside the company (for example, by getting back to academic studying). At approximately the same time as this decision, the COVID-19 lockdown was imposed in all Italian workplaces. This unprecedented event, in addition to the dire foregoing employment situation, led the remaining workers to spend most part of two years at home, with no client project to work on, with a few contacts with the management and almost no communication with their co-workers. During these two challenging years, the ICT company attempted to train the remaining workers in a new customer relationship management (CRM) platform. The course was delivered by a third-party training company. Unfortunately, no trainee passed the final test and none of them attained the course certification. In conclusion, the course was regarded by the trainees as another misstep from management.

On the impending opening of a new company office in the South of Italy, the ICT company decided to employ the remaining 18 workers in the new branch-office and enable them to fulfill the demands of the new position. To do so, the desired training program would need to motivate the trainees enough to help them learn new technologies and organizational methods, while easing their distrust of training due to the previous attempt. At this point, a new training company (Grifo Multimedia) entered the scene.

3.3 The Training Company

The ICT company contacted Grifo Multimedia Footnote 1 to commission a training program for a group of employees. This is a company with more than 20-year experience in the field of training solutions and with a strong reputation about e-learning.

Grifo Multimedia is specialized in supplying digital learning and gamification solutions, with a special focus on tailoring services to the client’s needs. As a company specialized in professional training programs, Grifo Multimedia takes care of all the facets of the training implementation: needs’ analysis, training design, digital learning content development and maintenance, ICT platform supply and customization. Grifo Multimedia was asked to deploy its competencies for the development of a training program that could be adapted to the delicate ICT company background. Grifo Multimedia appeared to be the best possible company to fulfill the training needs, mainly because of its good reputation in the area. In addition, this company has its headquarters in the same city where the employees in training will be relocated at the end of the training program and this made the trainees perceive them as reliable in the future given the physical proximity. Grifo Multimedia was responsible for the designing, planning, and delivering of the training course. According to the ICT company’s managers, the goal of the training program was to update the employees’ technical skills and soft skills. The purpose of re-skilling employees was to set them up to successfully fill the roles of developers and testers in the company.

No ethical guidelines were established during the contractualization of the training intervention between the training company and the commissioning ICT company, although a non-competitiveness clause was included in the contractual agreement. However, personal data were processed throughout the research, in compliance with current privacy protection regulations.

3.4 Participants

The beneficiaries of the training program were 18 workers aged between 52 and 62 (mean age of 55,7 years; Dev St = 2,7), 10 of them were men and eight were women. Workers lived in three cities in the North, Center and South of Italy: 2 in Milan, 10 in Rome, 6 in Naples. About their background, 6 of the trainees graduated in a technical institute, 9 have a high school diploma, two graduated with a bachelor’s degree, and one received a master degree. According to the managers and the labor union’s reports, none of the employees was involved in a company project at the time of the training, and all of them reported dissatisfaction towards the company and previous training attempts. Further details about participants were gathered and analyzed in a following phase of the research and are therefore reported within the context of the case.

The inclusion criteria for participants was based on two aspects: (i) Their willingness to participate in the training; (ii) The company offered them the opportunity to attend professional training to be professionally re-located.

3.5 Training Design

When planning the training, the main objective taken into account was to motivate and engage all the trainees all along the training program. To accomplish such a goal, the training team had to keep trainees involved in the decision-making process and customization for the entire duration of the training program. The ultimate goal of the training company was to have all trainees successfully pass the course and to see them efficiently relocated by their company. Learning objectives were defined in details. Learning objectives can be understood as precise descriptions of actions that learners should perform as a training result and that can be assessed during or after training (Chatterjee & Corral, 2017 , p.1). Coherently, learning objectives were defined:

During the course, trainees should demonstrably gain knowledge on the Agile-Scrum and DevOps framework, soft skills in the workplace, Micro-services architecture, Gitlab’s and Mia’s platforms, software testing, software development and service desk;

During the course, trainees should be fully engaged and satisfied with the training contents and methods;

Trainees should be able to build a support network to empower them during training

Teachers were required to adhere to the learning objectives and training model to the best of their ability. In order to do so, teachers conducted their lessons using a variety of teaching methods. Teachers conducted frontal lessons proposing anchoring ideas, following the pedagogical approach proposed by Ausubel ( 1970 ). In more details, teachers investigated the baseline knowledge and ideas of trainees through the data obtained during the pre-training stage; then, teachers during the lessons anchored the new concepts to previous knowledge, while highlighting the relevance of the new concepts. In addition, teachers often proposed case studies to further associate new knowledge to relatable events that might happen in a work setting (Schank, 1990 ). The case-studies material was posted online and discussed face-to-face. Finally, group activities, both online and in presence, were organized following the pedagogical principles of collaborative learning applied also online (McAlpine, 2000 ). The group activities were also designed to foster a sense of community among the participants (Harrison & West, 2014 ).

During preliminary meetings, the training team defined a basic structure of the training program. The training would consist of four steps:

Information gathering about participants and training needs, with the purpose of organizing training customization;

Entrance test, which would test baseline knowledge of the training’s topics;

Lessons with teachers and workshops with tutors, and a second mid-training administration of the general knowledge test;

Final general knowledge test, which would test learning outcomes of training.

Such a design was intended as just a general outline of training, that would be re-worked and enriched by the data gathered during the pre-training and the actual training phases.

It was required to end the whole training within four months; therefore, the course took place from September to December 2022. It included 10 training modules, totalizing a duration of 428 h of training. Approximately 41% of instructional sessions were conducted in-presence, while the remaining portion occurred online. The scheduling of the sessions attempted to balance in-presence and online training by proposing an agreed rotation of the two modalities ensuring, in this way, equal opportunities to experience both training methods while accommodating trainees’ availability. Commuting limitations and individual circumstances of trainees were considered during training to further accommodate trainees’ needs. The training hours were distributed across the training modules as follows:

M-1, “Aims and introduction”, 20 h, all in-presence;

M-2, “AGILE-SCRUM framework”, 32 h, of which 16 in-presence;

M-3, “Fundamentals of DevOps”, 60 h, of which 20 in-presence;

M-4, “Soft skills in the organization”, 40 h, of which 20 in-presence;

M-5, “Architecture of Micro-services and containers”, 60 h, of which 16 in-presence;

M-6, “Git-labs’ platform”, 20 h, all in-presence;

M-7, “Mia Platform’s fundamentals”, 16 h, all in-presence;

M-8, “Continuous Testing & Deployment in DevOps”, 40 h, of which 16 in-presence;

M-9, “Java Back-end Development”, 100 h, of which 16 in-presence;

M-10, “Service desk in DevOps”, 40 h, of which 16 in-presence.

3.6 The Measures

At each phase of the training, multiple instruments of measurement were used by the training team to assess attitudes, baseline skills, learning outcomes and training satisfaction. Table 1 presents a summary of used measurement tools, which will be further described within the relevant context of the case description. The curriculum vitae analysis was the only data scrutinized anonymously, as all documents were provided by the participants’ company, which requested anonymity for its employees’ documents. All other instruments clearly associated participants’ identity with the results. In this article we will continue to refer to participants anonymously even if the identity of the participants is known to the authors. All the tests and questionnaires were administered and scored automatically through the quiz and survey tools in thee-learning platform of the course.

3.7 Data Analysis

Given the limited number of our participants, we opted for a qualitative-quantitative case study. We have segmented the timing of the course into three different moments—pre-training, during training and post-training—and we used all the data available to track down the participation processes and effects on the trainees by considering these moments as benchmarkers. In this way, we can easily answer our research question—What are the effects of early customization and constant flexibility in a training program meant to relocate professionals?- because we can compare different moments and understand what actually happened during the training.

Although there is no single definition of what exactly a case study is, in general, this method is suitable whenever the aim is to study in depth the performance of a person, a group of people or an institution/agency over a certain period of time (Heale & Twycross, 2018 ). The main aim is not to simply describe a phenomenon but to understand why it went in that way, considering the specific circumstances of the case. In this way, indications to improve that situation can be gathered and generalized limited to similar cases. When this method is used, usually the data is collected in natural settings. By combining qualitative or quantitative datasets.

about the phenomenon, it is possible to gain a more in-depth insight into the phenomenon than would be obtained using only one type of data.

The intention of this case study is to test an early customized training model and consider the effects training customization can have on trainees, particularly those with a negative predisposition toward training programs due to failing previous experience.

Three researchers were involved in the data analysis: one of them—the first author of this paper—has prepared the selection of the data and their processing. The quantitative data was processed through simple analysis—frequency and average—and, when possible, with more sophisticated tests to verify the significance of the distribution. When analyzing the qualitative data, coding schemes and results were always discussed with the other two researchers. In building the qualitative categories, the Grounded Theory was employed as a method to develop ‘theory from data systematically obtained from social research’ (Glaser and Strauss, 2017 ). Grounded Theory consists of “systematic, yet flexible guidelines for collecting and analyzing qualitative data to construct theories ‘grounded’ in the data themselves’’ (Charmaz, 2006 ; p. 2). In essence, Grounded Theory allows researchers to continuously refine their theory as new data is collected and analyzed, securing a context-aware, interactive, and iterative approach to research.

In presenting the case study, we focused on and compared three specific moments of the training course: the pre-training phase when the program was conceived and prepared; the actual training phase during which the course was delivered to the trainees; finally, the post-training phase concerning the assessment of the learning and participation outcomes. Each of these phases will be illustrated in detail in the following section. More detailed information about the methodology used will be given at each phase, since each of them required some specificity.

3.8 Pre-training Phase

As a first step, Grifo Multimedia created the training team, consisting of a training manager and two training tutors, among which the first author of the present study was included. The training team analyzed the training demand coming from the ICT company management. As requested by the ICT company management, the course would have to mainly be held remotely and include several subjects’ areas: Agile-Scrum framework for organization, DevOps organizational model, soft skills for teamwork, microservices architecture and containers, Gitlab platform, Mia platform, Java back-end development, Continuous Testing and Deployment in DevOps. It was established that all these topics would be divided in separate training modules over the span of four months. Each training module needed to be self-contained and independent from the other modules.

Before the training design phase started, two main priorities were set, both of equal importance, to address requirements from the contextual setting and to conduct an effective training:

Fostering the participant’s collaboration with the training company and nurturing engagement for training;

Succeeding in gathering information useful for design training customization.

These priorities were intertwined and circular in their cause-effect relationship. Without effective collaboration and communication between the training company and the trainees, there would be no chance of early customization; at the same time, the interest displayed in the trainees’ needs had the potential to boost engagement and better collaboration and communication between the parties involved.

Soon the team realized that to fulfill these priorities a customization of the course was needed at a very early stage and a few steps were designed to this aim. Firstly, the training team analyzed the curriculum vitae of the training participants, which were provided by the ICT company. The provided curriculum vitae were entirely anonymous, by the will of the labor union who sought after the privacy for participants. Data about age, ICT skills and last position held were extracted from the CVs and analyzed. Information about technical tools and platforms were analyzed and categorized with the help of three technical professionals in the software testing and development field. Figure 1 represents professional background and Fig. 2 summarizes the ITC skills reported at the time of the CV analysis.

Employees’ professional background

Employees’ ICT skills

Employees’ professional background and ICT skills were considered during the training design. In their CVs, participants were allowed to provide information on more than one ICT skill, for the purpose of providing a comprehensive outlook on their background skills. Since many of the participants reported skills in basic computer programs (such as Microsoft Office and Database software) and obsolete programming languages (Cobol, JCL, Pascal, Clipper etc.), the training team planned to recruit experienced trainers who could lay the foundational concepts of the desired subjects for the course. However, this information was not sufficient to fully customize the training design.

To gather information about the participants’ needs and characteristics, the training team conducted face-to-face interviews with each participant. As the available curriculum vitae did not provide names for the participants, interviews were crucial to match participants with their skills and experiences. Interviews were conducted by two members of the training team in a quiet room at the ICT company office. One member of the training team had the interviewer role, while the other one presented Grifo Multimedia to the participants. The interview dealt with several topics:

Main activities conducted during the past 2 years of workplace inactivity;

The soft skills included into eLene4work project—a soft skills inventory whose aim is to create an open access tool, to help self-assess digital, interpersonal, cognitive and emotive soft skills—including the learning-to-learn soft skill, the digital problem solving soft skill and the organizational change processing soft skill (Cinque, 2017 ). The short self-assessment test consists of self-report sentences, with a four-steps Likert scale. The goal of the instrument is not to provide an objective measure of soft skills, but rather to encourage self-reflection and skills improvement. This tool was described by authors as a self-assessment questionnaire encouraging respondents’ proactivity, reflection on motivation, re-framing one’s professional experience and programming of one’s learning process. The learning-to-learn skill is defined as a learning specific meta-cognitive skill. Digital problem-solving sub-scale measures the ability to rely on online resources and new technologies to find solutions and reach one’s goals. The organizational change processing scale evaluates the ability to cope with and possibly cherish change in one’s organization;

Willingness to take part in a remote training course, expressed in three answering options: not at all; yes, under certain conditions; yes, under any conditions.

Figure 3 summarizes the main activities performed by the trainees from 2020 to 2022.

Main activities from 2020 to 2022

Participants were allowed to specify more than one activity, for the purpose of providing a comprehensive outlook on their background. As reported by management, the majority of participants confirmed that their work performance during the last two years was impaired by inactivity and/or work activities that were not coherent with their employee’s job profile. This result certainly helped researchers define the complexity of the context referred to in the research question. Participants had undergone a demotion in their work activities and, consequently, they had to cope with the lack of motivation in their job.

The content of interviews was analyzed by two separate coders. The coders looked at the data to single out the relevant excerpts, according to the research question. The coders went through several cycles of reading. During the first cycle, both coders looked at the interviews integrally. The coders confronted and discussed the divergent cases (about 10%) till a total agreement was reached. The selection of excerpts was better attuned during the second and third cycle, when the totality of the data was analyzed. The final selection was considered by both coders as well finalized in offering insights for our research question. The following excerpts are the result of this selection.

A significant example of these altered activities is the case of Jacob Footnote 2 who during the interview stated: “ For the last 10 years I worked autonomously as a second level analyst, on the mainframe for the Ministry of Education. I enjoyed being independent because it was rewarding. After my branch was acquired by the company, I mainly helped my colleagues with their access to the Cobble software ”. When asked for clarification, Jacob explained how access management for Cobble was a much more sporadic and support-adjacent role, while his precedent job entailed responsibility for an entire project and relationship with the client. A role change of this kind can be described as demotivating and affected Jacob’s sense of competence and autonomy. Jacob reported that his work was dull and unfulfilling. Another noteworthy interview result is about the failure of the previous training course—called Salesforce, mentioned in the Context section—they attended. When asked their opinion on why this training attempt failed, participants reported several factors:

The course was entirely in English. This represented a major obstacle because most of the participants only have a basic understanding of English;

At the beginning of the course, participants had the support of several training tutors. These tutors would help trainees to understand difficult topics, gather additional study material and translate some of the course content. However, tutors gradually withdrew their support and soon enough the participants felt abandoned and alone in facing the most difficult parts of the course;

Baseline skills were reportedly not sufficient to help understand the complex course content. Participants felt like they did not have enough information to grasp CRM applications.

As reported during the interviews, participants felt that the course had no clear purpose from an organizational perspective. Managers did not communicate aims and future projects in which they could be involved after the training. Consequently, participants felt as if they were required to commit to a pointless, difficult course, with no managerial support. This perception further fueled the sense of neglect for the company’s part.

Table 2 reports the results of the soft skill self-assessment tool.

Scores for the learning-to-learn skill show that participants believe to have a fair understanding of their own learning processes and preferences. We can better understand their level of understanding by considering also the statements registered during the interview. Rosy, for instance, stated: “ I think I know now well how to organize my learning strategies, but I recognize that my learning process might take a long time ”. Lucas recounted that he prefers to learn in a group, since he enjoys exchanging ideas and thinks that communication is an effective tool for learning. Furthermore, Andrew stated “ I’m not drawn to learning new technologies through theoretical study. I prefer learning through work, collaborating with my coworkers ”.

Scores for digital problem solving and organizational change processing can help highlight participants’ attitude towards digital innovations and towards the organization. These scales elicited reflection about participants’ own skills and organizational context. Regarding digital problem solving, Andrew reported: “I can’t always solve work problems on my own, because I’m not up to date with the latest technologies. Oftentimes, I don’t know how to find answers. My skills are only updated through training when I have to be included into a work project ”. During the interviews, six of the participants mentioned they did not feel knowledgeable about the latest technologies. In the matter of organizational change processing, several participants found it hard to answer the test because, as they stated, “ There is no organization to speak about ”. When asked to clarify this statement, Frank explained he did not have a point of reference for the organization, since he feels like he and his group are isolated from the company. All the answers provided by participants were crucial to define the context of the training, which represents a fundamental portion of the research question.

Finally, participants were asked if they were comfortable with a remote training program. Whilst none of the participants was opposed to remote training, most of them (83,3%) were in favor of it. A few participants (16.7%), however, consented to remote training only under certain conditions. When prompted, participants specified what circumstances needed to be provided:

Useful and functional tools, like an adequate presentation platform and a e-learning tool;

Reciprocal understanding and trust between participants and training team;

Collaboration among the participants, meaning fostering group learning and cooperation during training;

Rotation of remote and in-presence lessons and meetings.

These indications were especially useful during the designing and planning of the training model. Overall, the face-to-face interviews had a major impact on the customization of the course, which will be described towards the end of the current section.

After all the information gathered during interviews were analyzed, it became evident how participants valued group learning and collaboration with their colleagues. The training team concluded that the best way to deliver the program was the blended mode. In this way, group cohesion and collaboration could be better enhanced by exploiting the advantages of combining face-to-face and online encounters. Finding ways to interconnect moments of work in presence with those at a distance would certainly help all participants (trainers and trainees) to create a learning community capable of overcoming critical issues and achieving the aims set. Equally important was the matter of guaranteeing minimal commute stress during training, which was not a trivial task considering location of participants, as well as their personal and familiar lives. Finally, it was decided that training had to be preceded by kick-off encounters with the complete training team and all the participants.

The training team programmed a three-day meeting, where several topics would be discussed: interviews outcomes, a broader presentation of Grifo Multimedia and the training team, expectations about training, course contents and topics, attitudes towards training and organizational context, training on the digital tools that would be used during training, future working projects planned for the participants by the organization. Activities included during this training introduction aimed to give feedback about the interviews and how they would help design the training. As feedback is fundamental to learning engagement (Winstone et al., 2017 ), it was decided to constantly keep participants informed about the results of every test and questionnaire trainees were required to fill in. At the same time, there was a clear commitment in collecting continuous feedback, comments and suggestions about the training. To this aim, moments of exchange and communication among the training group members and between the trainees and the team responsible for delivering training were considered particularly relevant. The general aim was to create a collaborative learning environment for all parties involved.

Firstly, the training team introduced themselves and the company they work for (Grifo Multimedia). The training manager described the company’s most prominent activities and specialization. Then, the training team explained how tutors would be involved during training. Tutors would support training activities and access to digital tools and platforms, in addition there will always be an open channel for communication with teachers and training managers. Next, tutors presented results of the face-to-face interviews, showing them the same graphs we included in this paper (Figs. 1 , 2 and 3 ). Participants had the chance to pose any question or observation about results, which were promptly addressed by the training team. The training team announced that the training course will be delivered through a blended learning approach.

Afterwards, the training team presented an online board on Padlet, Footnote 3 named “My training expectations”. Participants could connect with the online board using their personal devices and add an anonymous note that answered the question “What are my expectations for the course about to begin?”. The whole activity was conducted by two tutors. While Fig. 4 shows the original board, Fig. 5 presents the translated content.

“My expectation about the course” results

“My expectations about the course”. Padlet translation

Participants’ contributions to the board were examined by the same two coders that examined the interviews. Again, the coders went through several cycles of reading. During the first cycle, coders read about 20% of data. The rest of the procedure followed the same steps as the qualitative analysis of the interviews.

Hearts below statements were added by participants, signaling their agreement with the statement. By reading this Padlet, tutors understood the importance participants attributed to learning and self-improvement. In addition, participants emphasized the importance of feeling supported during the training process, further confirming what emerged during face-to-face interviews. Curiosity, enthusiasm, and optimism were accompanied by caution caused by the novelty of the course. In addition, it seems they all agree about the importance of useful and well-thought-out study materials and training tools. This consideration is connected to their previous negative experience with training.

The next day, participants were divided into three groups of six to join a focus group with the training team. Two tutors and the training manager were assigned to each group. Every group met in a separate room for 30 min. The topic discussed during the focus group was “What is the group point of view about the training course about to start?”. Tutors and training managers had a facilitator role, which included: presenting the topic, explaining the topic if necessary, balancing the duration of each speech turn so that everyone could contribute, ensuring that everyone had at least one speech turn, mediating disagreements, and taking notes of the discussion. The analysis of the focus group discussions were conducted through the same analysis process of the interviews, previously described. Below are the summaries of the three group discussions:

Group 1 is composed of Jacob, Andrew, Alexander, Fern, Elias and Lucas. They expressed worries about measuring up to the difficulty of the training. They wanted to rise to the occasion, and wondered if maybe they were too late to develop their skills. However, participants expressed trust in their chance to advance. They recognized their current condition is better than two months ago and it could even improve with the right support and a good amount of practice. A certain amount of grit would be needed from their side. The issue about being not so young any more is discussed and they reckoned that youth boldness is counterbalanced by their being experienced. The prior two years of standstill fueled focus and the value of hard work motivated the participants to a new re-start. Not having a clear perception of their future was perceived as walking in the dark or like being asked to get back to first grade, and that studying new topics feels like invalidating their already long career.

Group 2 is composed by Max, Sandra, Dominique, Charlie, Pierce and Matthew. This group agreed that the course seemed well structured so far. For some of them, a blended learning course is a novelty and they hoped that such a method could be maintained during the whole training. Willingness to experiment new things is expressed and the novelty of the course is recognized as a stimulating challenge. The group focuses on the topic of their perceived professional expertise claiming that it could be a useful resource that defines their professional life and that the company did not recognize it as a resource. Charlie stated that their knowledge and experiential baggage could be restrictive if it prevented them from learning new things. Pierce added that the Project Manager role serves to polish the team's rough edges and to help leverage team members’ professional experiences.

Group 3 is composed by Rosy, Frank, Ronald, Dan, Steve, and Robert. The group worried about the difficulty of the topics the training proposed. Nonetheless, they all wanted to prove to be able to grasp new concepts. The need to not feel isolated and confused is remarked together with the intention to prove they are not obsolete workers. This group feels this is an opportunity not to be missed but it ought to be adequately accompanied all along the training. The radical difference from previous attempts of training is recognized and this could help the group in regaining trust in training.

After the focus groups’ discussions ended, the three groups were dissolved and all the following activities involved the cohort of trainees in its entirety.

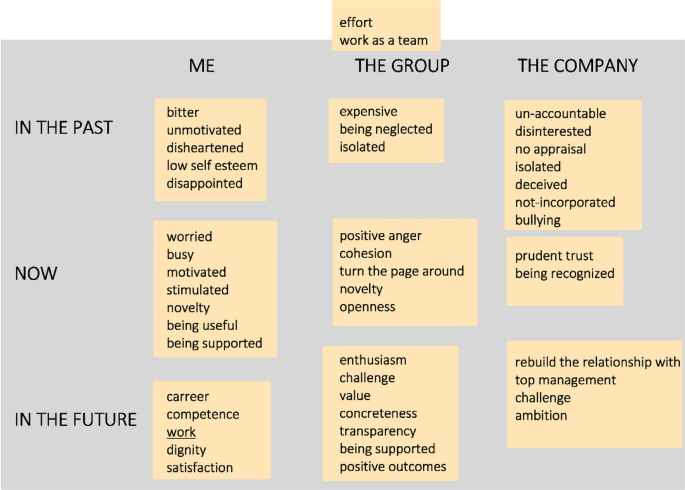

Based on the focus group results, a new activity was proposed to gather positive attitudes towards participants’ professional background and their future perspective. This activity consisted in brainstorming answers to fill out a 3 × 3 table (see Table 3 ).

Entries were categorized in attitudes regarding past, present and future, and attitudes towards themselves, the training group, and the company. This brainstorming had multiple aims. Firstly, to identify past experiences and perceptions, help participants elaborate the training and professional distress they experienced, and collectively overcome their training and professional past to allow themselves to start anew. Secondly, to gather data about how their present condition and the communication with the training team are perceived. Thirdly, to detect hopes and expectations for the future. All this information would be used for training customization. The activity was conducted by the first author of this article. The following rules were set: participants would first verbally report their ideas to the conductor indicating where to place them in the table; the conductor would listen and write down the participants’ ideas; participants can comment on the written text and add more content even if they did not unanimously agree on it. Figure 6 shows a photo of the original brainstorming, while Fig. 7 translates the content.

Photo of the original brainstorming table

Translation of brainstorming table

Participants were allowed to situate some of the contributions between categories, if needed. For instance, the contributions “Effort” and “Work as a team” were placed over the group category because, in the participants’ opinion, these contributions described the group in every moment. The analysis of this content was conducted through the same analysis process for qualitative data as previously described.

As the brainstorming strived for open communication, it is interesting to notice how this activity assisted in revealing all the negative attitudes and emotions linked to previous work conditions and training. Nonetheless, participants chose to describe the group as a team that always strived for hard work, despite all the distress they experienced. This proactive attitude reflects on the “now” category, where the prevalent attitude is characterized by motivation, eagerness and willingness to get involved in training. Contributions like “being supported”, “cohesion” and “being recognized” helped the training team understand how much open communication and feedback gathering would be important during the training process. Training customization would need to include a system to support participants and a feedback-based recursive training model. Finally, it seems important to point out how participants valued hard work, dignity and satisfaction with one’s work. The importance placed on hard work and challenge allowed to program an intensive training schedule which fitted with management’s requests for a short course.

During the last day of pre-training activities, training participants were instructed about the e-learning platform that would support training. Each of the training modules included specific contents and goals. Accessing the calendar area of the platform would show lessons agenda, alerts regarding the course, updated learning contents, and personal messages. Calendar included lessons held by teachers and workshops supported by tutors, indicating the modes—in-presence or remote—and the dates. In each learning module, participants would find links for the zoom class, the power point presentations used by teachers, exercises, tests and more in-depth materials shared by tutors, teachers and by the training participants themselves.

As the last pre-training activity, participants were tested on all the topics of the training program to assess their previous knowledge and obtain a baseline score to be compared to the course outcomes. The test was created with the help of all the teachers involved in training. They generated a multiple-choice test that represented all the topics of the course: AGILE-SCRUM framework; fundamental issues in DevOps; soft skills in the organization; architecture of micro-services and containers; git-labs’ platform; Mia Platform;, continuous testing and deployment in DevOps; Java back-end development; service desk in DevOps. The set of questions composing the tests covered basic information about the topics that would be extensively explored during the course. The test was a multiple-choice test with three-answers options, among which only one answer was the correct one. The test results were transformed into quantitative data by assigning to each correct answer a value of 1, and a value of 0 to all incorrect answers. Figure 8 reports the results of this general knowledge test.

Pre-course entrance general knowledge test results for every participant. Score ranged from 0 to 26

Only two participants, Pierce and Fern, out of 18 passed the first iteration of the pre-course entrance general knowledge test, reaching or surpassing the minimum score of 16 out of 26. Based on this result, the training team concluded that participants had little prior knowledge about the topics of the course that was about to start. Participants were informed about their score, but they did not know which one of their answers were correct or wrong. All the information gathered during the pre-training phase contributed to adapt the subsequent training phase and as it will be further explored and illustrated in Fig. 9 , the pre-training phase helped in understanding the complex context and in addressing the early customization requirement, postulated in our research question.

Representation of customization model

3.9 Training Phase

Before initiating the training, the information collected was analyzed to properly customize the training program. Decisions were made on the following matters:

Teachers. Data was used to define the fitting teachers’ profile. That is an experienced professional, the same age of participants, to overcome participants’ anxiety concerning young professionals. In addition, the teachers should be able to explain complex concepts by practical evidence based on both their own work life and that of the participants. Finally, teachers should be available for continuous dialogue with participants and should be flexible enough to adapt to rising needs.

Training team periodical meetings. The training team, including tutors and training manager would need to hold fine-tuning meetings with teachers to firstly present the training context and, later, to monitor the course evolution and negotiate changes or add-ons.

Continuous feedback. The training team would need to constantly be aware of the mood of the groups and their attitudes towards the training to promptly address issues that may impair the training success. This purpose would be achieved by frequent check-ins, where tutors would ask how the course is going on and what could be done to further support learning.

Training schedule. In defining the schedule, the participants’ work commitment is considered so as to accomplish the learning goals within the three months allocated to the training. Participants showcased eagerness to dive into a new training challenge and spend a great deal of effort in learning, if it means marking a turning point in their career.

Data collection. Via participants’ feedback, tests and questionnaires, the training team could monitor participants’ progress throughout the course and adjust if necessary.

Training content. All the provided materials are in Italian, the participants’ native language. In addition, teachers provided exercises, tests, simulations, case studies and explanatory real-life examples, as requested by the participants.

Training community. The pre-training process made evident how participants valued teamwork and collaboration. To meet this propensity, group activities and workshops were scheduled. In addition, the training team built a learning community that would support every participant. Groups were encouraged to exchange insights about the course, share additional study material, solve doubts by exchanging lesson notes and discussing them. Participants felt they could rely on a support network that also included the colleagues on which they can count on even when the training course will be over. This addressed the feeling of being isolated and neglected, participants reported during the pre-training phase.

These features allowed participants to play an active role in determining training features and changes in the training program. Figure 9 represents the training customization model, while Fig. 10 shows the structure of each training module.

Representation of module structure

The same module structure was repeated for each module. The entire course featured 10 modules, including the pre-training module and the final post-training module. Before each module starts, the training team meets the module's teacher and the team presents the participants’ background. Additionally, the training team would describe contents of previous modules to the new module’s teacher, to avoid content repetition.

A usual day of training would include a four-hours lesson with the module’s teacher and a four-hours workshop with tutors. During workshops, tutors presented exercises and tests provided by the module’s teacher, group work designed by the module’s teacher and the tutors, autonomous study and research from participants. At the beginning of each workshop, tutors would ask participants how the training was going. When participants notified tutors about specific needs or made suggestions, tutors would revise workshop activities for the day or forward to the training managers and teacher. For instance, during the second module, participants told tutors they were feeling overwhelmed by the quantity of new words in the Agile-Scrum technical jargon. To solve this issue, tutors suspended programmed activities for the day and proposed a group construction of an Agile-Scrum glossary. Participants were divided in four groups, and each of the groups studied a section of the training program. Then, participants wrote down in a shared document every new term they encountered and its definition. Finally, tutors compared every group doc file, deleted repetitions and built a complete Agile-Scrum glossary that participants could consult when studying. The final list was the result of collaboration between participants and tutor, and it proved to be a valuable resource during the whole course. In another instance, during the fifth module, participants reported they were finding some difficulties studying the course's content. To be precise, the group struggled with figuring out applications of the Microservices technology and felt that the course was too theoretical. The tutor reported this struggle to the rest of the training team, which negotiated with the teacher a more practical approach to the course's content. This negotiation resulted in a change of the subsequent lesson into a Q&A session that would help solve misunderstandings and doubts, plus the teacher presented a case study that would depict practical applications of Microservices technology. From that day forward, the teacher re-tuned his lessons to always include real-life examples of the technology application.

As stated, every module was followed by a satisfaction questionnaire and a final module-specific test. Satisfaction questionnaire would ask to evaluate the module on a scale from 1 to 5. Questionnaire required to assign a score to the module's content, method of delivery, perception of teacher’s knowledge, perception of teacher’s empathy and helpfulness and module’s overall organization. In addition, participants were free to add suggestions and comments. Figure 11 represents mean scores of every module’s satisfaction questionnaire.

Results of training satisfaction questionnaire for every module. Satisfaction ranged from 0 to 5

Comments and suggestions were particularly useful for training customization. For instance, after the Agile-Scrum Module, some participants suggested adding some time of individual study during workshops with tutors. The purpose of individual study would be to allow participants to review the morning’s lesson content and be prepared for group assignments during workshops. During the following workshop, tutors and participants negotiated time for individual study, and finally agreed on one hour per session of individual study.

Although the trend does not appear to be regularly increasing, we can observe how in the first four modules the score remains at a good level. The score dramatically drops at the Microservices module. When asked for feedback about that module, participants stated that it was too technical, therefore hard to grasp for beginners. In addition, participants felt that the study material provided was insufficient and unclear. The subsequent module had the same teacher, so he was asked to provide more explanatory content and exercises. Thanks to the teacher’s collaboration, the next module had a rising score. However, the last four scores do not reach the same level of satisfaction of the first four. When asked for feedback, participants stated that the reason for this decline is due to the more technical content of the last four modules.

Figure 12 presents module-specific test scores for each module’s test. They were all generated by the teacher responsible for the module and these questions did not overlap with those included in the general knowledge test. The tests were all multiple-choice tests with three-answers options, with only one correct answer.

Module-specific tests scores for every module. Score ranged from 0 to 15

The first and last module did not have a module-specific test because they did not involve theoretical or technical content. Considering module-specific test scores, on average participants reached the passing grade of 9 out of 15 for every module. This goal was reached even in the case of the least enjoyed modules.

Halfway through training, the general knowledge test was repeated to monitor changes in knowledge. The general knowledge test was repeated after a month and a half of training. As stated in the pre-training phase section, the test was considered passed with a score of at least 16 out of 26. Figure 13 compares learning results in the first and second administration.

Test score comparison between first and second general knowledge test administration. Score ranged from 0 to 26

Overall, participants obtained a higher score the second time they answered the test. The highest percent of score improvement was attained by Charlie, with a score improvement of 65.38%. All participants but one passed the test. The lowest score improvement was found to be Fern’s, who obtained the same score as the pre-course test. Fern obtained one of the highest scores in the pre-training administration of the test and did not improve her score in the following administration. This could happen for many reasons. Fern answered the first administration casually and incidentally reached a high score or she actually did not improve her knowledge; it is also possible that for her the course was too intensive and she did not have enough time to transform the content of the course into a consolidated knowledge. At this point of the training, it was decided to address this point by persevering with a flexible model of training. Since at this moment trainees only experienced half of the training course, the percentage of passing scores was deemed coherent with the stage of the training. After the second administration of the test, the course continued for another month and a half, with the same structure as described in Fig. 10 , the same customization model represented in Fig. 9 , and a continuous feedback loop between the training group and the training team.

The continuous adaptation process described in the present section addressed the constant flexibility of the training program implicit in our research question. Some results regarding the outcomes of the training program are already anticipated in this section, in the form of the mid-training test.

After exploring the “customization during training”, the following section will deal with the final phase of the training program and try to provide a definitive answer about the effects of the training, as required by the research question.

3.9.1 Post-training Phase

The post-training phase focused on gathering information about the outcomes of the training program. In particular, the considered outcomes included: (i) the trainees’ change of perspective about themselves, (ii) their experience with the training and their work life, (iii) their perception about their skills and (iv) their knowledge improvement.

After the course was over, participants met with the training manager for the purpose of having feedback over each training module. For every module, participants described positive and negative aspects about the training experience. This meeting provided initial elements about the effects of the training program, as by our research question. The meeting results can be summarized as such:

Positive features. According to participants, there was a change in the group’s self-awareness. The group felt more competent and resourceful, more aware of their past and future. Studying DevOps methodology taught them collaboration and sharing responsibility within the work team. Moreover, participants felt that they had a clearer understanding of the difference between soft and hard skills, and they felt more aware of communication strategies and emotional intelligence. In addition, participants enjoyed how the course was tailored to their needs: participants felt that the amount of communication with the training team helped fine tuning during the training. Discovering new tools and technologies was a valued feature of the training, and practice activities were especially useful. Participants felt supported by many of the teachers, and appreciated the differences between each teacher, who kept the course from becoming monotonous.

Negative features. According to participants, they preferred to have more lessons face-to-face rather than remote lessons. In addition, participants felt that some of the modules’ contents were too advanced for their knowledge and skills. In the instance of the Microservices training module they did not feel supported by the teacher, which caused the lowest satisfaction rate (Fig. 11 ). Participants felt that in some modules practice activities were not frequent enough, and the module resulted to be too theoretical. Finally, participants felt that blended training needed to skew more in favor of face-to-face training, since they thought that cohabiting the same physical space enhanced group collaboration.

Next, once again a brainstorming was conducted, as described in the Pre-training phase section. The purpose of the second brainstorming was firstly to detect changes in attitudes and emotions regarding training and career, and secondly, to track the effects of training customization on participants. Figure 14 shows the brainstorming in Italian, while Fig. 15 reports the content translated.

Brainstorming table in original language

Brainstorming table translation

The analysis of the table content was conducted through the same analysis process for qualitative data as previously described.

Contributions placed into the “in the past” row, mostly repeat what was stated in the first brainstorming table administration (see Fig. 7 ). However, the reference to workers’ rights and the search for new jobs is a substantial change in the contributions. Comparing results to the first administration, this proactive attitude only emerged in the group setting, while after training this attitude seems to also surface in the individual setting. This change can be explained as a shift in self-perception after training, perhaps caused by experiences of competence and self-efficacy. Participants may have retroactively reinterpreted their past experiences in accordance to more recent experiences, a phenomenon known for a long time as retroactive interference (Osgood, 1948 ). In addition, participants felt more empowered, self-aware and competent than in the past. The group reported feelings of being a part of a community. However, the current perspective towards the company did not seem to be better than the previous one even if participants felt enriched by the training. As for the “in the future” row, participants’ contributions focused on self-awareness, trust in their own skills, need for more practical skills and the appreciation for travels. In Fig. 10 , pictures represent landmarks and typical foods of Apulia, the region where the new company’s branch-office would be opened. This feature could reveal some excitement or curiosity about the opportunity connected to the opening of a new office located in that region. This enthusiastic perspective is detected also in the company cell of the future row: participants highlighted an ambitious future. The effects of the training, in summary, seemed to be a newly found sense of hope, self-efficacy and trust in the community, which is a further hint to compose an answer to our research question.

Finally, participants were asked to answer, for the last time, the general knowledge test. Figure 16 shows the comparison among the three test’s scores administrations.

Score comparison of the three general knowledge test administrations. Score ranged from 0 to 26

While 33.33% experienced a decline in their scores in the third test administration (Fig. 16 ), 66.66% of participants demonstrated a general improvement. Only one participant, Rosy, received a lower score at the third general knowledge test administration when compared to the first one. This result could be due to many different factors: overload with training; lack of understanding of the content; carelessness in answering the test. To transform this result into a constructive experience for Rosy, she received personalized feedback and she could review her answers’ pattern. Then, the training team organized an individual session with her to answer her questions and doubts. Overall, the mean score at the final administration was 22.22 points, compared to 20.27 points at the second administration and 12.27 points at the first one.

Scores for the three general knowledge test administrations were further analyzed to determine statistical significance. Analysis was conducted using the software rStudio. Normal distribution of the sample was proven by the Shapiro–Wilk normality test. The general knowledge test scores were normally distributed for W = 0.917, p < 0.001. The absence of outliers and sphericity were checked during analysis. The Repeated Measures ANOVA method was chosen for its ability to detect differences in means of multiple related samples, for example, in the case of a test that is repeated by the same group more than two times. The Repeated Measures ANOVA is often used to test scores differences in within-subjects designs (Lavori, 1990 ), which is exactly the case of the present study. To each phase of the program—pre, during, post—the general knowledge tests scores were significantly different (F(2, 34) = 39.29, p < 0.01, eta2[g] = 0.58). This means, at least one test score was significantly different from at least one of the other test scores. To identify which test administration was responsible for the statistical significance, multiple pairwise pair t-tests were performed as a post-hoc analysis of the Repeated Measures ANOVA. P-values were adjusted using the Bonferroni correction method. The pairwise pair t-tests detected that the difference between the first and second test administration was significant ( p < 0.05). The difference between the first and third test administration was also significant ( p < 0.05), while the difference between the second and third test administration was not significant. This result could be because the third iteration of the test happened between the seventh and eighth training module, when the majority of the training already happened.

A month after the last training meeting, participants were asked to express their point of view on the delivered training. Specifically, participants evaluated perceived efficacy and enjoyment of all training activities. Table 4 presents perceived efficacy mean scores for each training activity, while Table 5 presents enjoyment mean scores for every training activity.

Overall, face-to-face lessons with a teacher were the most enjoyable and useful activity according to participants. Participants agreed on the value of group communication activities and group activities in general. The latest appreciated activity was remote individual workshop activities. Overall, the course was mostly evaluated in a positive way, with the group interactions and face-to-face settings as the most appreciated activities involved. The fact that these features got the highest efficacy and enjoyment scores fits with the reported needs in the pre-training phase, as group activities and face-to-face encounters were detected as prominent needs. The reason teachers’ face-to-face lessons were the most appreciated could be related to the relationship established between trainer and trainees, which was perceived as less strong during remote lessons.

In addition, since tests provided constant feedback on learning progress, tests were mostly appreciated.

While this section had the goal of describing the effects of the customized training, the answer to the research question will be explored in the next section.

4 Discussion

In this paper, we presented a quali-quantitative case study of professional training concerning trainees with a history of negative previous training experiences. This case study can be also regarded as an example of early customization and full flexibility throughout the course. Therefore, our leading research question is: What are the effects of early customization and constant flexibility in a training program meant to relocate professionals?

To answer this question, we segmented the course in three phases—pre-training, training and post-training—and for each phase we looked at several aspects. For instance, the first two phases were particularly adequate to give information about the efficacy of the training program based on background knowledge, subsequent learning outcomes, trainee’s satisfaction, and trust towards training programs in general. Table 6 summarizes the results obtained at the first two phases. The third phase is not considered in this table but it will be used later to have a wider understanding of the customization effects.

The results of the general knowledge tests, together with the module specific tests’ scores, can provide an insight into the effectiveness of the learning process. Furthermore, the training program was proven to be perceived as relevant, useful and enjoyable, as evidenced by informal feedback, enjoyment questionnaire, satisfaction questionnaire and perceived usefulness questionnaire. This result is quite coherent with other research, where customization has already proved to increase learners’ motivation, perception of a meaningful experience and it facilitates the transfer of learned knowledge and skills to a real-world working environment (Lainema & Nurmi, 2005 ). This allows us to assume that the earlier the customization is provided, the more these results are amplified.

As the most enjoyed and effective training activities were face-to-face lessons and group activities, we can infer two conclusions:

The relationship between trainer/teacher and trainees was particularly effective. This can be seen as a positive outcome of customization particularly in terms of choosing the teachers to fit the trainees’ characteristics and needs;

The preference towards group learning, expressed during the pre-training phase, was confirmed to foretell enjoyment and effectiveness. In other words, favoring group learning and expressing this preference effectively resulted in positive outcomes.