60 Words To Describe Writing Or Speaking Styles

Writers Write creates and shares writing resources. In this post, we give you 60 words to describe writing or speaking styles .

What Is Your Writing Or Speaking Style?

“Style, in its broadest sense, is a specific way in which we create, perform, or do something. Style in literature is the way an author uses words to tell a story. It is a writer’s way of showing his or her personality on paper.

Just as a person putting together items of clothing and jewellery, and applying make-up creates a personal style, the way a person puts together word choice, sentence structure, and figurative language describes his or her literary style.

When combined, the choices they make work together to establish mood , images, and meaning. This has an effect on their audience.”

From 7 Choices That Affect A Writer’s Style

- articulate – able to express your thoughts, arguments, and ideas clearly and effectively; writing or speech is clear and easy to understand

- chatty – a chatty writing style is friendly and informal

- circuitous – taking a long time to say what you really mean when you are talking or writing about something

- clean – clean language or humour does not offend people, especially because it does not involve sex

- conversational – a conversational style of writing or speaking is informal, like a private conversation

- crisp – crisp speech or writing is clear and effective

- declamatory – expressing feelings or opinions with great force

- diffuse – using too many words and not easy to understand

- discursive – including information that is not relevant to the main subject

- economical – an economical way of speaking or writing does not use more words than are necessary

- elliptical – suggesting what you mean rather than saying or writing it clearly

- eloquent – expressing what you mean using clear and effective language

- emphatic – making your meaning very clear because you have very strong feelings about a situation or subject

- emphatically – very firmly and clearly

- epigrammatic – expressing something such as a feeling or idea in a short and clever or funny way

- epistolary – relating to the writing of letters

- euphemistic – euphemistic expressions are used for talking about unpleasant or embarrassing subjects without mentioning the things themselves

- flowery – flowery language or writing uses many complicated words that are intended to make it more attractive

- fluent – expressing yourself in a clear and confident way, without seeming to make an effort

- formal – correct or conservative in style, and suitable for official or serious situations or occasions

- gossipy – a gossipy letter is lively and full of news about the writer of the letter and about other people

- grandiloquent – expressed in extremely formal language in order to impress people, and often sounding silly because of this

- idiomatic – expressing things in a way that sounds natural

- inarticulate – not able to express clearly what you want to say; not spoken or pronounced clearly

- incoherent – unable to express yourself clearly

- informal – used about language or behaviour that is suitable for using with friends but not in formal situations

- journalistic – similar in style to journalism

- learned – a learned piece of writing shows great knowledge about a subject, especially an academic subject

- literary – involving books or the activity of writing, reading, or studying books; relating to the kind of words that are used only in stories or poems, and not in normal writing or speech

- lyric – using words to express feelings in the way that a song would

- lyrical – having the qualities of music

- ornate – using unusual words and complicated sentences

- orotund – containing extremely formal and complicated language intended to impress people

- parenthetical – not directly connected with what you are saying or writing

- pejorative – a pejorative word, phrase etc expresses criticism or a bad opinion of someone or something

- picturesque – picturesque language is unusual and interesting

- pithy – a pithy statement or piece of writing is short and very effective

- poetic – expressing ideas in a very sensitive way and with great beauty or imagination

- polemical – using or supported by strong arguments

- ponderous – ponderous writing or speech is serious and boring

- portentous – trying to seem very serious and important, in order to impress people

- prolix – using too many words and therefore boring

- punchy – a punchy piece of writing such as a speech, report, or slogan is one that has a strong effect because it uses clear simple language and not many words

- rambling – a rambling speech or piece of writing is long and confusing

- readable – writing that is readable is clear and able to be read

- rhetorical – relating to a style of speaking or writing that is effective or intended to influence people; written or spoken in a way that is impressive but is not honest

- rhetorically – in a way that expects or wants no answer; using or relating to rhetoric

- rough – a rough drawing or piece of writing is not completely finished

- roundly – in a strong and clear way

- sententious – expressing opinions about right and wrong behaviour in a way that is intended to impress people

- sesquipedalian – using a lot of long words that most people do not understand

- Shakespearean – using words in the way that is typical of Shakespeare’s writing

- stylistic – relating to ways of creating effects, especially in language and literature

- succinct – expressed in a very short but clear way

- turgid – using language in a way that is complicated and difficult to understand

- unprintable – used for describing writing or words that you think are offensive

- vague – someone who is vague does not clearly or fully explain something

- verbose – using more words than necessary, and therefore long and boring

- well-turned – a well-turned phrase is one that is expressed well

- wordy – using more words than are necessary, especially long or formal words

Source for Words: Macmillan Dictionary

If you enjoyed this article, you may also enjoy

- The 4 Main Characters As Literary Devices

- 7 Choices That Affect A Writer’s Style

- 5 Incredibly Simple Ways To Help Writers Show And Not Tell

- Cheat Sheets for Writing Body Language

- Punctuation For Beginners

- If you want to learn how to write a book, sign up for our online course .

- If you want to learn how to blog, sign up for the online course.

- Style , Writing Resource

4 thoughts on “60 Words To Describe Writing Or Speaking Styles”

useful thank you …

useful thank you.

Very informative. Taught me slot

Thanks a lot. Very useful.

Comments are closed.

© Writers Write 2022

- 40 Useful Words and Phrases for Top-Notch Essays

To be truly brilliant, an essay needs to utilise the right language. You could make a great point, but if it’s not intelligently articulated, you almost needn’t have bothered.

Developing the language skills to build an argument and to write persuasively is crucial if you’re to write outstanding essays every time. In this article, we’re going to equip you with the words and phrases you need to write a top-notch essay, along with examples of how to utilise them.

It’s by no means an exhaustive list, and there will often be other ways of using the words and phrases we describe that we won’t have room to include, but there should be more than enough below to help you make an instant improvement to your essay-writing skills.

If you’re interested in developing your language and persuasive skills, Oxford Royale offers summer courses at its Oxford Summer School , Cambridge Summer School , London Summer School , San Francisco Summer School and Yale Summer School . You can study courses to learn english , prepare for careers in law , medicine , business , engineering and leadership.

General explaining

Let’s start by looking at language for general explanations of complex points.

1. In order to

Usage: “In order to” can be used to introduce an explanation for the purpose of an argument. Example: “In order to understand X, we need first to understand Y.”

2. In other words

Usage: Use “in other words” when you want to express something in a different way (more simply), to make it easier to understand, or to emphasise or expand on a point. Example: “Frogs are amphibians. In other words, they live on the land and in the water.”

3. To put it another way

Usage: This phrase is another way of saying “in other words”, and can be used in particularly complex points, when you feel that an alternative way of wording a problem may help the reader achieve a better understanding of its significance. Example: “Plants rely on photosynthesis. To put it another way, they will die without the sun.”

4. That is to say

Usage: “That is” and “that is to say” can be used to add further detail to your explanation, or to be more precise. Example: “Whales are mammals. That is to say, they must breathe air.”

5. To that end

Usage: Use “to that end” or “to this end” in a similar way to “in order to” or “so”. Example: “Zoologists have long sought to understand how animals communicate with each other. To that end, a new study has been launched that looks at elephant sounds and their possible meanings.”

Adding additional information to support a point

Students often make the mistake of using synonyms of “and” each time they want to add further information in support of a point they’re making, or to build an argument. Here are some cleverer ways of doing this.

6. Moreover

Usage: Employ “moreover” at the start of a sentence to add extra information in support of a point you’re making. Example: “Moreover, the results of a recent piece of research provide compelling evidence in support of…”

7. Furthermore

Usage:This is also generally used at the start of a sentence, to add extra information. Example: “Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that…”

8. What’s more

Usage: This is used in the same way as “moreover” and “furthermore”. Example: “What’s more, this isn’t the only evidence that supports this hypothesis.”

9. Likewise

Usage: Use “likewise” when you want to talk about something that agrees with what you’ve just mentioned. Example: “Scholar A believes X. Likewise, Scholar B argues compellingly in favour of this point of view.”

10. Similarly

Usage: Use “similarly” in the same way as “likewise”. Example: “Audiences at the time reacted with shock to Beethoven’s new work, because it was very different to what they were used to. Similarly, we have a tendency to react with surprise to the unfamiliar.”

11. Another key thing to remember

Usage: Use the phrase “another key point to remember” or “another key fact to remember” to introduce additional facts without using the word “also”. Example: “As a Romantic, Blake was a proponent of a closer relationship between humans and nature. Another key point to remember is that Blake was writing during the Industrial Revolution, which had a major impact on the world around him.”

12. As well as

Usage: Use “as well as” instead of “also” or “and”. Example: “Scholar A argued that this was due to X, as well as Y.”

13. Not only… but also

Usage: This wording is used to add an extra piece of information, often something that’s in some way more surprising or unexpected than the first piece of information. Example: “Not only did Edmund Hillary have the honour of being the first to reach the summit of Everest, but he was also appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire.”

14. Coupled with

Usage: Used when considering two or more arguments at a time. Example: “Coupled with the literary evidence, the statistics paint a compelling view of…”

15. Firstly, secondly, thirdly…

Usage: This can be used to structure an argument, presenting facts clearly one after the other. Example: “There are many points in support of this view. Firstly, X. Secondly, Y. And thirdly, Z.

16. Not to mention/to say nothing of

Usage: “Not to mention” and “to say nothing of” can be used to add extra information with a bit of emphasis. Example: “The war caused unprecedented suffering to millions of people, not to mention its impact on the country’s economy.”

Words and phrases for demonstrating contrast

When you’re developing an argument, you will often need to present contrasting or opposing opinions or evidence – “it could show this, but it could also show this”, or “X says this, but Y disagrees”. This section covers words you can use instead of the “but” in these examples, to make your writing sound more intelligent and interesting.

17. However

Usage: Use “however” to introduce a point that disagrees with what you’ve just said. Example: “Scholar A thinks this. However, Scholar B reached a different conclusion.”

18. On the other hand

Usage: Usage of this phrase includes introducing a contrasting interpretation of the same piece of evidence, a different piece of evidence that suggests something else, or an opposing opinion. Example: “The historical evidence appears to suggest a clear-cut situation. On the other hand, the archaeological evidence presents a somewhat less straightforward picture of what happened that day.”

19. Having said that

Usage: Used in a similar manner to “on the other hand” or “but”. Example: “The historians are unanimous in telling us X, an agreement that suggests that this version of events must be an accurate account. Having said that, the archaeology tells a different story.”

20. By contrast/in comparison

Usage: Use “by contrast” or “in comparison” when you’re comparing and contrasting pieces of evidence. Example: “Scholar A’s opinion, then, is based on insufficient evidence. By contrast, Scholar B’s opinion seems more plausible.”

21. Then again

Usage: Use this to cast doubt on an assertion. Example: “Writer A asserts that this was the reason for what happened. Then again, it’s possible that he was being paid to say this.”

22. That said

Usage: This is used in the same way as “then again”. Example: “The evidence ostensibly appears to point to this conclusion. That said, much of the evidence is unreliable at best.”

Usage: Use this when you want to introduce a contrasting idea. Example: “Much of scholarship has focused on this evidence. Yet not everyone agrees that this is the most important aspect of the situation.”

Adding a proviso or acknowledging reservations

Sometimes, you may need to acknowledge a shortfalling in a piece of evidence, or add a proviso. Here are some ways of doing so.

24. Despite this

Usage: Use “despite this” or “in spite of this” when you want to outline a point that stands regardless of a shortfalling in the evidence. Example: “The sample size was small, but the results were important despite this.”

25. With this in mind

Usage: Use this when you want your reader to consider a point in the knowledge of something else. Example: “We’ve seen that the methods used in the 19th century study did not always live up to the rigorous standards expected in scientific research today, which makes it difficult to draw definite conclusions. With this in mind, let’s look at a more recent study to see how the results compare.”

26. Provided that

Usage: This means “on condition that”. You can also say “providing that” or just “providing” to mean the same thing. Example: “We may use this as evidence to support our argument, provided that we bear in mind the limitations of the methods used to obtain it.”

27. In view of/in light of

Usage: These phrases are used when something has shed light on something else. Example: “In light of the evidence from the 2013 study, we have a better understanding of…”

28. Nonetheless

Usage: This is similar to “despite this”. Example: “The study had its limitations, but it was nonetheless groundbreaking for its day.”

29. Nevertheless

Usage: This is the same as “nonetheless”. Example: “The study was flawed, but it was important nevertheless.”

30. Notwithstanding

Usage: This is another way of saying “nonetheless”. Example: “Notwithstanding the limitations of the methodology used, it was an important study in the development of how we view the workings of the human mind.”

Giving examples

Good essays always back up points with examples, but it’s going to get boring if you use the expression “for example” every time. Here are a couple of other ways of saying the same thing.

31. For instance

Example: “Some birds migrate to avoid harsher winter climates. Swallows, for instance, leave the UK in early winter and fly south…”

32. To give an illustration

Example: “To give an illustration of what I mean, let’s look at the case of…”

Signifying importance

When you want to demonstrate that a point is particularly important, there are several ways of highlighting it as such.

33. Significantly

Usage: Used to introduce a point that is loaded with meaning that might not be immediately apparent. Example: “Significantly, Tacitus omits to tell us the kind of gossip prevalent in Suetonius’ accounts of the same period.”

34. Notably

Usage: This can be used to mean “significantly” (as above), and it can also be used interchangeably with “in particular” (the example below demonstrates the first of these ways of using it). Example: “Actual figures are notably absent from Scholar A’s analysis.”

35. Importantly

Usage: Use “importantly” interchangeably with “significantly”. Example: “Importantly, Scholar A was being employed by X when he wrote this work, and was presumably therefore under pressure to portray the situation more favourably than he perhaps might otherwise have done.”

Summarising

You’ve almost made it to the end of the essay, but your work isn’t over yet. You need to end by wrapping up everything you’ve talked about, showing that you’ve considered the arguments on both sides and reached the most likely conclusion. Here are some words and phrases to help you.

36. In conclusion

Usage: Typically used to introduce the concluding paragraph or sentence of an essay, summarising what you’ve discussed in a broad overview. Example: “In conclusion, the evidence points almost exclusively to Argument A.”

37. Above all

Usage: Used to signify what you believe to be the most significant point, and the main takeaway from the essay. Example: “Above all, it seems pertinent to remember that…”

38. Persuasive

Usage: This is a useful word to use when summarising which argument you find most convincing. Example: “Scholar A’s point – that Constanze Mozart was motivated by financial gain – seems to me to be the most persuasive argument for her actions following Mozart’s death.”

39. Compelling

Usage: Use in the same way as “persuasive” above. Example: “The most compelling argument is presented by Scholar A.”

40. All things considered

Usage: This means “taking everything into account”. Example: “All things considered, it seems reasonable to assume that…”

How many of these words and phrases will you get into your next essay? And are any of your favourite essay terms missing from our list? Let us know in the comments below, or get in touch here to find out more about courses that can help you with your essays.

At Oxford Royale Academy, we offer a number of summer school courses for young people who are keen to improve their essay writing skills. Click here to apply for one of our courses today, including law , business , medicine and engineering .

Comments are closed.

- Games, topic printables & more

- The 4 main speech types

- Example speeches

- Commemorative

- Declamation

- Demonstration

- Informative

- Introduction

- Student Council

- Speech topics

- Poems to read aloud

- How to write a speech

- Using props/visual aids

- Acute anxiety help

- Breathing exercises

- Letting go - free e-course

- Using self-hypnosis

- Delivery overview

- 4 modes of delivery

- How to make cue cards

- How to read a speech

- 9 vocal aspects

- Vocal variety

- Diction/articulation

- Pronunciation

- Speaking rate

- How to use pauses

- Eye contact

- Body language

- Voice image

- Voice health

- Public speaking activities and games

- Blogging Aloud

- About me/contact

How to write a good speech in 7 steps

By: Susan Dugdale

- an easily followed format for writing a great speech

Did you know writing a speech doesn't have be an anxious, nail biting experience?

Unsure? Don't be.

You may have lived with the idea you were never good with words for a long time. Or perhaps giving speeches at school brought you out in cold sweats.

However learning how to write a speech is relatively straight forward when you learn to write out loud.

And that's the journey I am offering to take you on: step by step.

To learn quickly, go slow

Take all the time you need. This speech writing format has 7 steps, each building on the next.

Walk, rather than run, your way through all of them. Don't be tempted to rush. Familiarize yourself with the ideas. Try them out.

I know there are well-advertised short cuts and promises of 'write a speech in 5 minutes'. However in reality they only truly work for somebody who already has the basic foundations of speech writing in place.

The foundation of good speech writing

These steps are the backbone of sound speech preparation. Learn and follow them well at the outset and yes, given more experience and practice you could probably flick something together quickly. Like any skill, the more it's used, the easier it gets.

In the meantime...

Step 1: Begin with a speech overview or outline

Are you in a hurry? Without time to read a whole page? Grab ... The Quick How to Write a Speech Checklist And come back to get the details later.

- WHO you are writing your speech for (your target audience)

- WHY you are preparing this speech. What's the main purpose of your speech? Is it to inform or tell your audience about something? To teach them a new skill or demonstrate something? To persuade or to entertain? (See 4 types of speeches: informative, demonstrative, persuasive and special occasion or entertaining for more.) What do you want them to think, feel or do as a result of listening the speech?

- WHAT your speech is going to be about (its topic) - You'll want to have thought through your main points and have ranked them in order of importance. And have sorted the supporting research you need to make those points effectively.

- HOW much time you have for your speech eg. 3 minutes, 5 minutes... The amount of time you've been allocated dictates how much content you need. If you're unsure check this page: how many words per minute in a speech: a quick reference guide . You'll find estimates of the number of words required for 1 - 10 minute speeches by slow, medium and fast talkers.

Use an outline

The best way to make sure you deliver an effective speech is to start by carefully completing a speech outline covering the essentials: WHO, WHY, WHAT and HOW.

Beginning to write without thinking your speech through is a bit like heading off on a journey not knowing why you're traveling or where you're going to end up. You can find yourself lost in a deep, dark, murky muddle of ideas very quickly!

Pulling together a speech overview or outline is a much safer option. It's the map you'll follow to get where you want to go.

Get a blank speech outline template to complete

Click the link to find out a whole lot more about preparing a speech outline . ☺ You'll also find a free printable blank speech outline template. I recommend using it!

Understanding speech construction

Before you begin to write, using your completed outline as a guide, let's briefly look at what you're aiming to prepare.

- an opening or introduction

- the body where the bulk of the information is given

- and an ending (or summary).

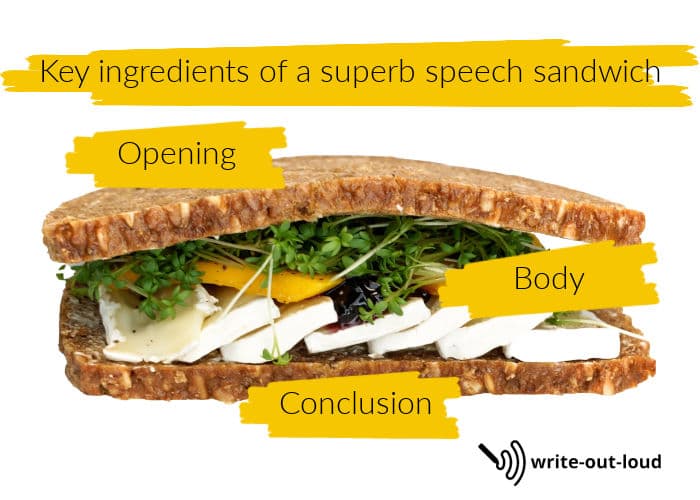

Imagine your speech as a sandwich

If you think of a speech as a sandwich you'll get the idea.

The opening and ending are the slices of bread holding the filling (the major points or the body of your speech) together.

You can build yourself a simple sandwich with one filling (one big idea) or you could go gourmet and add up to three or, even five. The choice is yours.

But whatever you choose to serve, as a good cook, you need to consider who is going to eat it! And that's your audience.

So let's find out who they are before we do anything else.

Step 2: Know who you are talking to

Understanding your audience.

Did you know a good speech is never written from the speaker's point of view? ( If you need to know more about why check out this page on building rapport .)

Begin with the most important idea/point on your outline.

Consider HOW you can explain (show, tell) that to your audience in the most effective way for them to easily understand it.

Writing from the audience's point of view

To help you write from an audience point of view, it's a good idea to identify either a real person or the type of person who is most likely to be listening to you.

Make sure you select someone who represents the "majority" of the people who will be in your audience. That is they are neither struggling to comprehend you at the bottom of your scale or light-years ahead at the top.

Now imagine they are sitting next to you eagerly waiting to hear what you're going to say. Give them a name, for example, Joe, to help make them real.

Ask yourself

- How do I need to tailor my information to meet Joe's needs? For example, do you tell personal stories to illustrate your main points? Absolutely! Yes. This is a very powerful technique. (Click storytelling in speeches to find out more.)

- What type or level of language is right for Joe as well as my topic? For example, if I use jargon (activity, industry or profession specific vocabulary) will it be understood?

Step 3: Writing as you speak

Writing oral language.

Write down what you want to say about your first main point as if you were talking directly to Joe.

If it helps, say it all out loud before you write it down and/or record it.

Use the information below as a guide

(Click to download The Characteristics of Spoken Language as a pdf.)

You do not have to write absolutely everything you're going to say down * but you do need to write down, or outline, the sequence of ideas to ensure they are logical and easily followed.

Remember too, to explain or illustrate your point with examples from your research.

( * Tip: If this is your first speech the safety net of having everything written down could be just what you need. It's easier to recover from a patch of jitters when you have a word by word manuscript than if you have either none, or a bare outline. Your call!)

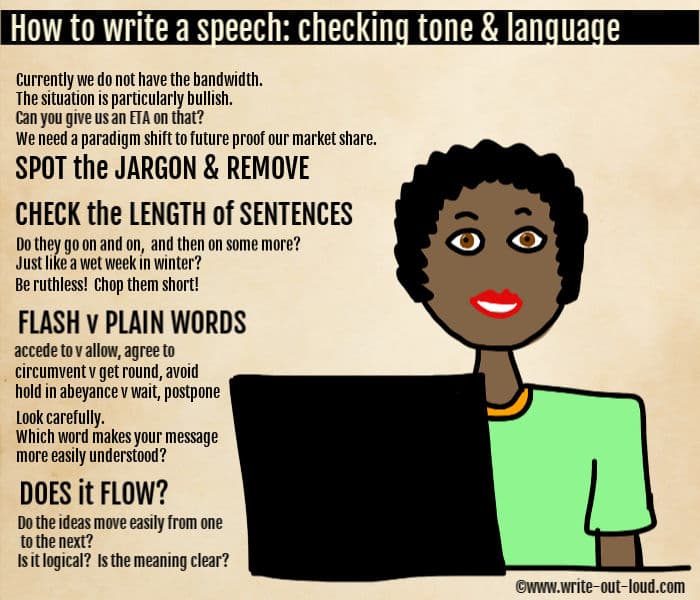

Step 4: Checking tone and language

The focus of this step is re-working what you've done in Step 2 and 3.

You identified who you were talking to (Step 2) and in Step 3, wrote up your first main point. Is it right? Have you made yourself clear? Check it.

How well you complete this step depends on how well you understand the needs of the people who are going to listen to your speech.

Please do not assume because you know what you're talking about the person (Joe) you've chosen to represent your audience will too. Joe is not a mind-reader!

How to check what you've prepared

- Check the "tone" of your language . Is it right for the occasion, subject matter and your audience?

- Check the length of your sentences. You need short sentences. If they're too long or complicated you risk losing your listeners.

Check for jargon too. These are industry, activity or group exclusive words.

For instance take the phrase: authentic learning . This comes from teaching and refers to connecting lessons to the daily life of students. Authentic learning is learning that is relevant and meaningful for students. If you're not a teacher you may not understand the phrase.

The use of any vocabulary requiring insider knowledge needs to be thought through from the audience perspective. Jargon can close people out.

- Read what you've written out loud. If it flows naturally, in a logical manner, continue the process with your next main idea. If it doesn't, rework.

We use whole sentences and part ones, and we mix them up with asides or appeals e.g. "Did you get that? Of course you did. Right...Let's move it along. I was saying ..."

Click for more about the differences between spoken and written language .

And now repeat the process

Repeat this process for the remainder of your main ideas.

Because you've done the first one carefully, the rest should follow fairly easily.

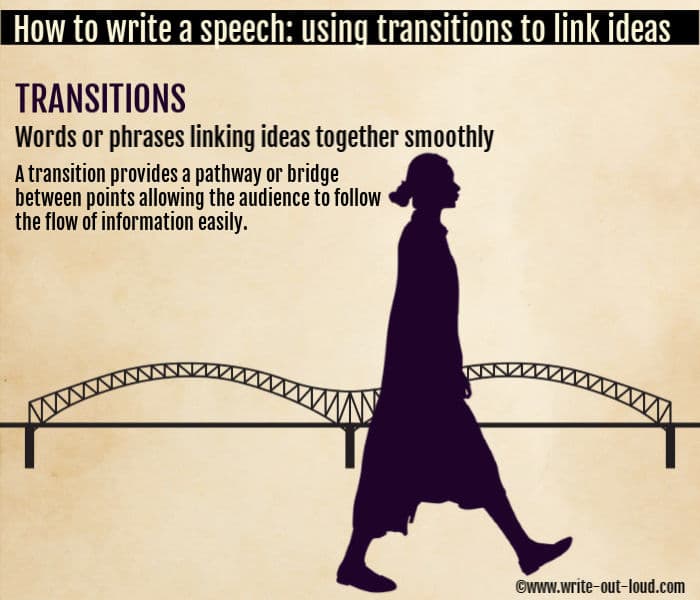

Step 5: Use transitions

Providing links or transitions between main ideas.

Between each of your main ideas you need to provide a bridge or pathway for your audience. The clearer the pathway or bridge, the easier it is for them to make the transition from one idea to the next.

If your speech contains more than three main ideas and each is building on the last, then consider using a "catch-up" or summary as part of your transitions.

Is your speech being evaluated? Find out exactly what aspects you're being assessed on using this standard speech evaluation form

Link/transition examples

A link can be as simple as:

"We've explored one scenario for the ending of Block Buster 111, but let's consider another. This time..."

What follows this transition is the introduction of Main Idea Two.

Here's a summarizing link/transition example:

"We've ended Blockbuster 111 four ways so far. In the first, everybody died. In the second, everybody died BUT their ghosts remained to haunt the area. In the third, one villain died. His partner reformed and after a fight-out with the hero, they both strode off into the sunset, friends forever. In the fourth, the hero dies in a major battle but is reborn sometime in the future.

And now what about one more? What if nobody died? The fifth possibility..."

Go back through your main ideas checking the links. Remember Joe as you go. Try each transition or link out loud and really listen to yourself. Is it obvious? Easily followed?

Keep them if they are clear and concise.

For more about transitions (with examples) see Andrew Dlugan's excellent article, Speech Transitions: Magical words and Phrases .

Step 6: The end of your speech

The ideal ending is highly memorable . You want it to live on in the minds of your listeners long after your speech is finished. Often it combines a call to action with a summary of major points.

Example speech endings

Example 1: The desired outcome of a speech persuading people to vote for you in an upcoming election is that they get out there on voting day and do so. You can help that outcome along by calling them to register their support by signing a prepared pledge statement as they leave.

"We're agreed we want change. You can help us give it to you by signing this pledge statement as you leave. Be part of the change you want to see!

Example 2: The desired outcome is increased sales figures. The call to action is made urgent with the introduction of time specific incentives.

"You have three weeks from the time you leave this hall to make that dream family holiday in New Zealand yours. Can you do it? Will you do it? The kids will love it. Your wife will love it. Do it now!"

How to figure out the right call to action

A clue for working out what the most appropriate call to action might be, is to go back to your original purpose for giving the speech.

- Was it to motivate or inspire?

- Was it to persuade to a particular point of view?

- Was it to share specialist information?

- Was it to celebrate a person, a place, time or event?

Ask yourself what you want people to do as a result of having listened to your speech.

For more about ending speeches

Visit this page for more about how to end a speech effectively . You'll find two additional types of speech endings with examples.

Write and test

Write your ending and test it out loud. Try it out on a friend, or two. Is it good? Does it work?

Step 7: The introduction

Once you've got the filling (main ideas) the linking and the ending in place, it's time to focus on the introduction.

The introduction comes last as it's the most important part of your speech. This is the bit that either has people sitting up alert or slumped and waiting for you to end. It's the tone setter!

What makes a great speech opening?

Ideally you want an opening that makes listening to you the only thing the 'Joes' in the audience want to do.

You want them to forget they're hungry or that their chair is hard or that their bills need paying.

The way to do that is to capture their interest straight away. You do this with a "hook".

Hooks to catch your audience's attention

Hooks come in as many forms as there are speeches and audiences. Your task is work out what specific hook is needed to catch your audience.

Go back to the purpose. Why are you giving this speech?

Once you have your answer, consider your call to action. What do you want the audience to do, and, or take away, as a result of listening to you?

Next think about the imaginary or real person you wrote for when you were focusing on your main ideas.

Choosing the best hook

- Is it humor?

- Would shock tactics work?

- Is it a rhetorical question?

- Is it formality or informality?

- Is it an outline or overview of what you're going to cover, including the call to action?

- Or is it a mix of all these elements?

A hook example

Here's an example from a fictional political speech. The speaker is lobbying for votes. His audience are predominately workers whose future's are not secure.

"How's your imagination this morning? Good? (Pause for response from audience) Great, I'm glad. Because we're going to put it to work starting right now.

I want you to see your future. What does it look like? Are you happy? Is everything as you want it to be? No? Let's change that. We could do it. And we could do it today.

At the end of this speech you're going to be given the opportunity to change your world, for a better one ...

No, I'm not a magician. Or a simpleton with big ideas and precious little commonsense. I'm an ordinary man, just like you. And I have a plan to share!"

And then our speaker is off into his main points supported by examples. The end, which he has already foreshadowed in his opening, is the call to vote for him.

Prepare several hooks

Experiment with several openings until you've found the one that serves your audience, your subject matter and your purpose best.

For many more examples of speech openings go to: how to write a speech introduction . You'll find 12 of the very best ways to start a speech.

That completes the initial seven steps towards writing your speech. If you've followed them all the way through, congratulations, you now have the text of your speech!

Although you might have the words, you're still a couple of steps away from being ready to deliver them. Both of them are essential if you want the very best outcome possible. They are below. Please take them.

Step 8: Checking content and timing

This step pulls everything together.

Check once, check twice, check three times & then once more!

Go through your speech really carefully.

On the first read through check you've got your main points in their correct order with supporting material, plus an effective introduction and ending.

On the second read through check the linking passages or transitions making sure they are clear and easily followed.

On the third reading check your sentence structure, language use and tone.

Double, triple check the timing

Now go though once more.

This time read it aloud slowly and time yourself.

If it's too long for the time allowance you've been given make the necessary cuts.

Start by looking at your examples rather than the main ideas themselves. If you've used several examples to illustrate one principal idea, cut the least important out.

Also look to see if you've repeated yourself unnecessarily or, gone off track. If it's not relevant, cut it.

Repeat the process, condensing until your speech fits the required length, preferably coming in just under your time limit.

You can also find out how approximately long it will take you to say the words you have by using this very handy words to minutes converter . It's an excellent tool, one I frequently use. While it can't give you a precise time, it does provide a reasonable estimate.

Step 9: Rehearsing your speech

And NOW you are finished with writing the speech, and are ready for REHEARSAL .

Please don't be tempted to skip this step. It is not an extra thrown in for good measure. It's essential.

The "not-so-secret" secret of successful speeches combines good writing with practice, practice and then, practicing some more.

Go to how to practice public speaking and you'll find rehearsal techniques and suggestions to boost your speech delivery from ordinary to extraordinary.

The Quick How to Write a Speech Checklist

Before you begin writing you need:.

- Your speech OUTLINE with your main ideas ranked in the order you're going to present them. (If you haven't done one complete this 4 step sample speech outline . It will make the writing process much easier.)

- Your RESEARCH

- You also need to know WHO you're speaking to, the PURPOSE of the speech and HOW long you're speaking for

The basic format

- the body where you present your main ideas

Split your time allowance so that you spend approximately 70% on the body and 15% each on the introduction and ending.

How to write the speech

- Write your main ideas out incorporating your examples and research

- Link them together making sure each flows in a smooth, logical progression

- Write your ending, summarizing your main ideas briefly and end with a call for action

- Write your introduction considering the 'hook' you're going to use to get your audience listening

- An often quoted saying to explain the process is: Tell them what you're going to tell them (Introduction) Tell them (Body of your speech - the main ideas plus examples) Tell them what you told them (The ending)

TEST before presenting. Read aloud several times to check the flow of material, the suitability of language and the timing.

- Return to top

speaking out loud

Subscribe for FREE weekly alerts about what's new For more see speaking out loud

Top 10 popular pages

- Welcome speech

- Demonstration speech topics

- Impromptu speech topic cards

- Thank you quotes

- Impromptu public speaking topics

- Farewell speeches

- Phrases for welcome speeches

- Student council speeches

- Free sample eulogies

From fear to fun in 28 ways

A complete one stop resource to scuttle fear in the best of all possible ways - with laughter.

Useful pages

- Search this site

- About me & Contact

- Free e-course

- Privacy policy

©Copyright 2006-24 www.write-out-loud.com

Designed and built by Clickstream Designs

How to Build Vocabulary You Can Actually Use in Speech and Writing?

- Published on Aug 25, 2019

- shares

This post comes from my experience of adding more than 8,000 words and phrases to my vocabulary in a way that I can actually use them on the fly in my speech and writing. Some words, especially those that I haven’t used for long time, may elude me, but overall the recall & use works quite well.

That’s why you build vocabulary, right? To use in speech and writing. There are no prizes for building list of words you can’t use. (The ultimate goal of vocabulary-building is to use words in verbal communication where you’ve to come up with an appropriate word in split second. It’s not to say that it’s easy to come up with words while writing, but in writing you can at least afford to think.)

This post also adopts couple of best practices such as

- Spaced repetition,

- Deliberate Practice,

- Begin with end in mind, and

- Build on what you already know

In this post, you’ll learn how you too can build such vocabulary, the one you can actually use. However, be warned. It’s not easy. It requires consistent work. But the rewards are more than worth the squeeze.

Since building such vocabulary is one of the most challenging aspects of English Language, you’ll stand out in crowd when you use precise words and, the best part, you can use this sub-skill till you’re in this world, long after you retire professionally. (Doesn’t this sound so much better when weighed against today’s reality where most professional skills get outdated in just few years?)

You may have grossly overestimated the size of your vocabulary

Once your understand the difference between active and passive vocabulary, you’ll realize that size of your vocabulary isn’t what you think it to be.

Active vs. Passive vocabulary

Words that you can use in speech and writing constitute your active vocabulary (also called functional vocabulary). You, of course, understand these words while reading and listening as well. Think of words such as eat , sell , drink , see , and cook .

But how about words such as munch , outsmart , salvage , savagery , and skinny ? Do you use these words regularly while speaking and writing? Unlikely. Do you understand meaning of these words while reading and listening? Highly likely. Such words constitute your passive vocabulary (also called recognition vocabulary). You can understand these words while reading and listening, but you can’t use them while speaking and writing.

Your active vocabulary is a tiny subset of your passive vocabulary:

(While the proportion of the two inner circles – active and passive vocabulary – bears some resemblance to reality, the outer rectangle is not proportionate because of paucity of space. In reality, the outer rectangle is much bigger, representing hundreds of thousands of words.)

Note : Feel free to use the above and other images in the post, using the link of this post for reference/attribution.

Many mistakenly believe that they’ve strong vocabulary because they can understand most words when reading and listening. But the real magic, the real use of vocabulary is when you use words in speech and writing. If you evaluate your vocabulary against this yardstick – active vs. passive – your confidence in your vocabulary will be shaken.

Why build vocabulary – a small exercise?

You would be all too aware of cases where people frequently pause while speaking because they can’t think of words for what they want to say. We can easily spot such extreme cases.

What we fail to spot, however, are less extreme, far more common cases where people don’t pause, but they use imprecise words and long-winding explanations to drive their message.

The bridge was destroyed (or broken) by the flooded river.

The bridge was washed away by the flooded river.

Although both convey the message, the second sentence stands out because of use of precise phrase.

What word(s) best describe what’s happening in the picture below?

Image source

Not the best response.

A better word is ‘emptied’. Even ‘dumped’ is great.

A crisp description of the above action would be: “The dumper emptied (or dumped) the stones on the roadside.”

What about this?

‘Took out grapes’.

‘Plucked grapes’ is far better.

If you notice, these words – wash away , empty , dump , and pluck – are simple. We can easily understand them while reading and listening, but rarely use them (with the possible exception of empty ) in speech or writing. Remember, active vs. passive vocabulary?

If you use such precise words in your communication you’ll stand out in crowd.

Little wonder, studies point to a correlation between strength of vocabulary and professional success. Earl Nightingale, a renowned self-help expert and author, in his 20-year study of college graduates found :

Without a single exception, those who had scored highest on the vocabulary test given in college, were in the top income group, while those who had scored the lowest were in the bottom income group.

He also refers to a study by Johnson O’Connor, an American educator and researcher, who gave vocabulary tests to executive and supervisory personnel in 39 large manufacturing companies. According to this study:

Presidents and vice presidents averaged 236 out of a possible 272 points; managers averaged 168; superintendents, 140; foremen, 114; floor bosses, 86. In virtually every case, vocabulary correlated with executive level and income.

Though there are plenty of studies linking professional success with fluency in English overall, I haven’t come across any study linking professional success with any individual component – grammar and pronunciation, for example – of English language other than vocabulary.

You can make professional success a motivation to improve your active vocabulary.

Let’s dive into the tactics now.

How to build vocabulary you can use in speech and writing?

(In the spirit of the topic of this section, I’ve highlighted words that I’ve shifted from my passive to active vocabulary in red font . I’ve done this for only this section, lest the red font become too distracting.)

Almost all of us build vocabulary through the following two-step process:

Step 1 : We come across new words while reading and listening. Meanings of many of these words get registered in our brains – sometimes vaguely, sometimes precisely – through the context in which we see these words. John Rupert Firth, a leading figure in British linguistics during the 1950s, rightly said , “You shall know a word by the company it keeps.”

Many of these words then figure repeatedly in our reading and listening and gradually, as if by osmosis , they start taking roots in our passive vocabulary.

Step 2 : We start using some of these words in our speech and writing. (They are, as discussed earlier, just a small fraction of our passive vocabulary.) By and large, we stay in our comfort zones, making do with this limited set of words.

Little wonder, we add to our vocabulary in trickle . In his book Word Power Made Easy , Norman Lewis laments the tortoise-like rate of vocabulary-building among adults:

Educational testing indicates that children of ten who have grown up in families in which English is the native language have recognition [passive] vocabularies of over twenty thousand words. And that these same ten-year-olds have been learning new words at a rate of many hundreds a year since the age of four . In astonishing contrast, studies show that adults who are no longer attending school increase their vocabularies at a pace slower than twenty-five to fifty words annually .

Adults improve passive vocabulary at an astonishingly meagre rate of 25-50 words a year. The chain to acquire active vocabulary is getting broken at the first step itself – failure to read or listen enough (see Step 1 we just covered). Most are not even reaching the second step, which is far tougher than the first. Following statistic from National Spoken English Skills Report by Aspiring Minds (sample of more than 30,000 students from 500+ colleges in India) bears this point:

Only 33 percent know such simple words! They’re not getting enough inputs.

Such vocabulary-acquisition can be schematically represented as:

The problem here is at both the steps of vocabulary acquisition:

- Not enough inputs (represented by funnel filled only little) and

- Not enough exploration and use of words to convert inputs into active vocabulary (represented by few drops coming out of the funnel)

Here is what you can do to dramatically improve your active vocabulary:

1. Get more inputs (reading and listening)

That’s a no-brainer. The more you read,

- the more new words you come across and

- the more earlier-seen words get reinforced

If you’ve to prioritize between reading and listening purely from the perspective of building vocabulary, go for more reading, because it’s easier to read and mark words on paper or screen. Note that listening will be a more helpful input when you’re working on your speaking skills .

So develop the habit to read something 30-60 minutes every day. It has benefits far beyond just vocabulary-building .

If you increase your inputs, your vocabulary-acquisition funnel will look something like:

More inputs but no other steps result in larger active vocabulary.

2. Gather words from your passive vocabulary for deeper exploration

The reading and listening you do, over months and years, increase the size of your passive vocabulary. There are plenty of words, almost inexhaustible, sitting underutilized in your passive vocabulary. Wouldn’t it be awesome if you could move many of them to your active vocabulary? That would be easier too because you don’t have to learn them from scratch. You already understand their meaning and usage, at least to some extent. That’s like plucking – to use the word we’ve already overused – low hanging fruits.

While reading and listening, note down words that you’re already familiar with, but you don’t use them (that is they’re part of your passive vocabulary). We covered few examples of such words earlier in the post – pluck , dump , salvage , munch , etc. If you’re like most, your passive vocabulary is already large, waiting for you to shift some of it to your active vocabulary. You can also note down completely unfamiliar words, but only in exceptional cases.

To put what I said in the previous paragraph in more concrete terms, you may ask following two questions to decide which words to note down for further exploration:

- Do you understand the meaning of the word from the context of your reading or listening?

- Do you use this word while speaking and writing?

If the answer is ‘yes’ to the first question and ‘no’ to the second, you can note down the word.

3. Explore the words in an online dictionary

Time to go a step further than seeing words in context while reading.

You need to explore each word (you’ve noted) further in a dictionary. Know its precise meaning(s). Listen to pronunciation and speak it out loud, first individually and then as part of sentences. (If you’re interested in the topic of pronunciation, refer to the post on pronunciation .) And, equally important, see few sentences where the word has been used.

Preferably, note down the meaning(s) and few example sentences so that you can practice spaced repetition and retain them for long. Those who do not know what spaced repetition is, it is the best way to retain things in your long-term memory . There are number of options these days to note words and other details about them – note-taking apps and good-old word document. I’ve been copying-pasting on word document and taking printouts. For details on how I practiced spaced repetition, refer to my experience of adding more than 8,000 words to my vocabulary.

But why go through the drudgery of noting down – and going through, probably multiple times – example sentences? Why not just construct sentences straight after knowing the meaning of the word?

Blachowicz, Fisher, Ogle, and Watts-Taffe, in their paper , point out the yawning gap between knowing the meaning of words and using them in sentences:

Research suggests that students are able to select correct definitions for unknown words from a dictionary, but they have difficulty then using these words in production tasks such as writing sentences using the new words.

If only it was easy. It’s even more difficult in verbal communication where, unlike in writing, you don’t have the luxury of pausing and recalling appropriate words.

That’s why you need to focus on example sentences.

Majority of those who refer dictionary, however, restrict themselves to meaning of the word. Few bother to check example sentences. But they’re at least as much important as meaning of the word, because they teach you how to use words in sentences, and sentences are the building blocks of speech and writing.

If you regularly explore words in a dictionary, your vocabulary-acquisition funnel will look something like:

More inputs combined with exploration of words result in even larger active vocabulary.

After you absorb the meaning and example sentences of a word, it enters a virtuous cycle of consolidation. The next time you read or listen the word, you’ll take note of it and its use more actively , which will further reinforce it in your memory. In contrast, if you didn’t interact with the word in-depth, it’ll pass unnoticed, like thousands do every day. That’s cascading effect.

Participate in a short survey

If you’re a learner or teacher of English language, you can help improve website’s content for the visitors through a short survey.

4. Use them

To quote Maxwell Nurnberg and Morris Rosenblum from their book All About Words :

In vocabulary building, the problem is not so much finding new words or even finding out what they mean. The problem is to remember them, to fix them permanently in your mind. For you can see that if you are merely introduced to words, you will forget them as quickly as you forget the names of people you are casually introduced to at a crowded party – unless you meet them again or unless you spend some time with them.

This is the crux. Use it or lose it.

Without using, the words will slowly slip away from your memory.

Without using the words few times, you won’t feel confident using them in situations that matter.

If you use the words you explored in dictionary, your vocabulary-acquisition funnel will look something like:

More inputs combined with exploration of words and use of them result in the largest active vocabulary.

Here is a comparison of the four ways in which people acquire active vocabulary:

The big question though is how to use the words you’re exploring. Here are few exercises to accomplish this most important step in vocabulary-building process.

Vocabulary exercises: how to use words you’re learning

You can practice these vocabulary activities for 10-odd minutes every day, preferably during the time you waste such as commuting or waiting, to shift more and more words you’ve noted down to your active vocabulary. I’ve used these activities extensively, with strong results to boot.

1. Form sentences and speak them out during your reviews

When you review the list of words you’ve compiled, take a word as cue without looking at its meaning and examples, recall its meaning, and, most importantly, speak out 4-5 sentences using the word. It’s nothing but a flashcard in work. If you follow spaced repetition diligently, you’ll go through this process at least few times. I recommend reading my experience of building vocabulary (linked earlier) to know how I did this part.

Why speaking out, though? (If the surroundings don’t permit, it can be whisper as well.)

Speaking out the word as part of few sentences will serve the additional purpose of making your vocal cords accustomed to new words and phrases.

2. Create thematic webs

When reviewing, take a word and think of other words related to that word. Web of words on a particular theme, in short, and hence the name ‘thematic web’. These are five of many, many thematic webs I’ve actually come up in my reviews:

(Note: Name of the theme is in bold. Second, where there are multiple words, I’ve underlined the main word.)

If I come across the word ‘gourmet’ in my review, I’ll also quickly recall all the words related with food: tea strainer, kitchen cabinet, sink, dish cloth, wipe dishes, rinse utensils, immerse beans in water, simmer, steam, gourmet food, sprinkle salt, spread butter, smear butter, sauté, toss vegetables, and garnish the sweet dish

Similarly, for other themes:

Prognosis, recuperate, frail, pass away, resting place, supplemental air, excruciating pain, and salubrious

C. Showing off

Showy, gaudy, extravaganza, over the top, ostentatious, and grandstanding

D. Crowd behavior

Restive, expectant, hysteria, swoon, resounding welcome, rapturous, jeer, and cheer

E. Rainfall

Deluge, cats and dogs, downpour, cloudburst, heavens opened, started pouring , submerged, embankment, inundate, waterlogged, soaked to the skin, take shelter, run for a cover, torrent, and thunderbolt

(If you notice, words in a particular theme are much wider in sweep than just synonyms.)

It takes me under a minute to complete dozen-odd words in a theme. However, in the beginning, when you’re still adding to your active vocabulary in tons, you’ll struggle to go beyond 2-3 simple words when thinking out such thematic lists. That’s absolutely fine.

Why thematic web, though?

Because that’s how we recall words when speaking or writing. (If you flip through Word Power Made Easy by Norman Lewis, a popular book on improving vocabulary, you’ll realize that each of its chapters represents a particular idea, something similar to a theme.) Besides, building a web also quickly jogs you through many more words.

3. Describe what you see around

In a commute or other time-waster, look around and speak softly an apt word in a split second for whatever you see. Few examples:

- If you see grass on the roadside, you can say verdant or luxurious .

- If you see a vehicle stopping by the roadside, you can say pull over .

- If you see a vehicle speeding away from other vehicles, you can say pull away .

- If you see a person carrying a load on the road side, you can say lug and pavement .

Key is to come up with these words in a flash. Go for speed, not accuracy. (After all, you’ll have similar reaction time when speaking.) If you can’t think of an appropriate word for what you see instantaneously – and there will be plenty in the beginning – skip it.

This vocabulary exercise also serves an unintended, though important, objective of curbing the tendency to first think in the native language and then translating into English as you speak. This happens because the spontaneity in coming up with words forces you to think directly in English.

Last, this exercise also helps you assess your current level of vocabulary (for spoken English). If you struggle to come up with words for too many things/ situations, you’ve job on your hands.

4. Describe what one person or object is doing

Another vocabulary exercise you can practice during time-wasters is to focus on a single person and describe her/ his actions, as they unfold, for few minutes. An example:

He is skimming Facebook on his phone. OK, he is done with it. Now, he is taking out his earphones. He has plugged them into his phone, and now he is watching some video. He is watching and watching. There is something funny there in that video, which makes him giggle . Simultaneously, he is adjusting the bag slung across his shoulder.

The underlined words are few of the new additions to my active vocabulary I used on the fly when focusing on this person.

Feel free to improvise and modify this process to suit your unique conditions, keeping in mind the fundamentals such as spaced repetition, utilizing the time you waste, and putting what you’re learning to use.

To end this section, I must point out that you need to build habit to perform these exercises for few minutes at certain time(s) of the day. They’re effective when done regularly.

Why I learnt English vocabulary this way?

For few reasons:

1. I worked backwards from the end result to prepare for real-world situations

David H. Freedman learnt Italian using Duolingo , a popular language-learning app, for more than 70 hours in the buildup to his trip to Italy. A week before they were to leave for Rome, his wife put him to test. She asked how would he ask for his way from Rome airport to the downtown. And how would he order in a restaurant?

David failed miserably.

He had become a master of multiple-choice questions in Italian, which had little bearing on the real situations he would face.

We make this mistake all the time. We don’t start from the end goal and work backwards to design our lessons and exercises accordingly. David’s goal wasn’t to pass a vocabulary test. It was to strike conversation socially.

Coming back to the topic of vocabulary, learning meanings and examples of words in significant volume is a challenge. But a much bigger challenge is to recall an apt word in split second while speaking. (That’s the holy grail of any vocabulary-building exercise, and that’s the end goal we want to achieve.)

The exercises I described earlier in the post follow the same path – backwards from the end.

2. I used proven scientific methods to increase effectiveness

Looking at just a word and recalling its meaning and coming up with rapid-fire examples where that word can be used introduced elements of deliberate practice, the fastest way to build neural connection and hence any skill. (See the exercises we covered.) For the uninitiated, deliberate practice is the way top performers in any field practice .

Another proven method I used was spaced repetition.

3. I built on what I already knew to progress faster

Covering mainly passive vocabulary has made sure that I’m building on what I already know, which makes for faster progress.

Don’t ignore these when building vocabulary

Keep in mind following while building vocabulary:

1. Use of fancy words in communication make you look dumb, not smart

Don’t pick fancy words to add to your vocabulary. Use of such words doesn’t make you look smart. It makes your communication incomprehensible and it shows lack of empathy for the listeners. So avoid learning words such as soliloquy and twerking . The more the word is used in common parlance, the better it is.

An example of how fancy words can make a piece of writing bad is this review of movie , which is littered with plenty of fancy words such as caper , overlong , tomfoolery , hectoring , and cockney . For the same reason, Shashi Tharoor’s Word of the Week is not a good idea . Don’t add such words to your vocabulary.

2. Verbs are more important than nouns and adjectives

Verbs describe action, tell us what to do. They’re clearer. Let me explain this through an example.

In his book Start with Why , Simon Sinek articulates why verbs are more effective than nouns:

For values or guiding principles to be truly effective they have to be verbs. It’s not ‘integrity’, it’s ‘always do the right thing’. It’s not ‘innovation’, it’s ‘look at the problem from a different angle’. Articulating our values as verbs gives us a clear idea… we have a clear idea of how to act in any situation.

‘Always do the right thing’ is better than ‘integrity’ and ‘look at the problem from a different angle’ is better than ‘innovation’ because the former, a verb, in each case is clearer.

The same (importance of verb) is emphasized by L. Dee Fink in his book Creating Significant Learning Experiences in the context of defining learning goals for college students.

Moreover, most people’s vocabulary is particularly poor in verbs. Remember, the verbs from the three examples at the beginning of the post – wash away , dump , and pluck ? How many use them? And they’re simple.

3. Don’t ignore simple verbs

You wouldn’t bother to note down words such as slip , give , and move because you think you know them inside out, after all you’ve been using them regularly for ages.

I also thought so… until I explored few of them.

I found that majority of simple words have few common usages we rarely use. Use of simple words for such common usages will stand your communication skills out.

An example:

a. To slide suddenly or involuntarily as on a smooth surface: She slipped on the icy ground .

b. To slide out from grasp, etc.: The soap slipped from my hand .

c. To move or start gradually from a place or position: His hat slipped over his eyes .

d. To pass without having been acted upon or used: to let an opportunity slip .

e. To pass quickly (often followed by away or by): The years slipped by .

f. To move or go quietly, cautiously, or unobtrusively: to slip out of a room .

Most use the word in the meaning (a) and (b), but if you use the word for meaning (c) to (f) – which BTW is common – you’ll impress people.

Another example:

a. Without the physical presence of people in control: an unmanned spacecraft .

b. Hovering near the unmanned iPod resting on the side bar, stands a short, blond man.

c. Political leaders are vocal about the benefits they expect to see from unmanned aircraft.

Most use the word unmanned with a moving object such as an aircraft or a drone, but how about using it with an iPod (see (b) above).

4. Don’t ignore phrasal verbs. Get at least common idioms. Proverbs… maybe

4.1 phrasal verbs.

Phrasal verbs are verbs made from combining a main verb and an adverb or preposition or both. For example, here are few phrasal verbs of verb give :

We use phrasal verbs aplenty:

I went to the airport to see my friend off .

He could see through my carefully-crafted ruse.

I took off my coat.

The new captain took over the reins of the company on June 25.

So, don’t ignore them.

Unfortunately, you can’t predict the meaning of a phrasal verb from the main verb. For example, it’s hard to guess the meaning of take over or take off from take . You’ve to learn each phrasal verb separately.

What about idioms?

Compared to phrasal verbs, idioms are relatively less used, but it’s good to know the common ones. To continue the example of word give , here are few idioms derived from it:

Give and take

Give or take

Give ground

Give rise to

Want a list of common idioms? It’s here: List of 200 common idioms .

4.3 Proverbs

Proverbs are popular sayings that provide nuggets of wisdom. Example: A bird in hand is worth two in the bush.

Compared to phrasal verbs and idioms, they’re much less used in common conversation and therefore you can do without them.

For the motivated, here is a list of common proverbs: List of 200 common proverbs .

5. Steal phrases, words, and even sentences you like

If you like phrases and sentences you come across, add them to your list for future use. I do it all the time and have built a decent repository of phrases and sentences. Few examples (underlined part is the key phrase):

The bondholders faced the prospect of losing their trousers .

The economy behaved more like a rollercoaster than a balloon . [Whereas rollercoaster refers to an up and down movement, balloon refers to a continuous expansion. Doesn’t such a short phrase express such a profound meaning?]

Throw enough spaghetti against the wall and some of it sticks .

You need blue collar work ethic to succeed in this industry.

He runs fast. Not quite .

Time to give up scalpel . Bring in hammer .

Note that you would usually not find such phrases in a dictionary, because dictionaries are limited to words, phrasal verbs, idioms, and maybe proverbs.

6. Commonly-used nouns

One of my goals while building vocabulary has been to learn what to call commonly-used objects (or nouns) that most struggle to put a word to.

To give an example, what would you call the following?

Answer: Tea strainer.

You would sound far more impressive when you say, “My tea strainer has turned blackish because of months of filtering tea.”

Than when you say, “The implement that filters tea has turned blackish because of months of filtering tea.”

What do you say?

More examples:

Saucer (We use it every day, but call it ‘plate’.)

Straight/ wavy/ curly hair

Corner shop

I’ll end with a brief reference to the UIDAI project that is providing unique biometric ID to every Indian. This project, launched in 2009, has so far issued a unique ID (popularly called Aadhaar card) to more than 1.1 billion people. The project faced many teething problems and has been a one big grind for the implementers. But once this massive data of billion + people was collected, so many obstinate, long-standing problems are being eased using this data, which otherwise would’ve been difficult to pull off. It has enabled faster delivery of scores of government and private services, checked duplication on many fronts, and brought in more transparency in financial and other transactions, denting parallel economy. There are many more. And many more are being conceived on top of this data.

At some level, vocabulary is somewhat similar. It’ll take effort, but once you’ve sizable active vocabulary, it’ll strengthen arguably the most challenging and the most impressive part of your communication. And because it takes some doing, it’s not easy for others to catch up.

Anil is the person behind this website. He writes on most aspects of English Language Skills. More about him here:

Such a comprehensive guide. Awesome…

I am using the note app and inbuilt dictionary of iPhone. I have accumulated over 1400 words in 1 year. Will definitely implement ideas from this blog.

Krishna, thanks. If you’re building vocabulary for using, then make sure you work it accordingly.

Building solid vocabulary is my new year’s resolution and you’ve perfectly captured the issues I’ve been facing, with emphasis on passive vocabulary building. So many vocab apps are multiple choice and thereby useless for this reason. Thanks so much for the exercises! I plan to put them to use!

It was everything that I need to boost my active vocabulary. Thank you so much for sharing all these precious pieces of information.

Anil sir, I am quiet satisfied the way you laid out everything possible that one needs to know from A-Z. Also, thanks for assuring me from your experience that applying this will work.

This post definitely blew me away…. I am impressed! Thank you so much for sharing such valuable information. It was exactly what I needed!

Amazing post! While reading this post, I am thinking about the person who developed this. I wanna give a big hug and thank you so much.

Comments are closed.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Big Words To Use in Speeches and Debates. When you’re giving a speech or debating, using sophisticated words can provide greater emotional resonance, add credence to your argument, or otherwise make your speaking flow more freely. Just make sure you know what the word means and how it's pronounced before you actually say it out loud. Advertisement.

60 Words To Describe Writing Or Speaking Styles. articulate – able to express your thoughts, arguments, and ideas clearly and effectively; writing or speech is clear and easy to understand; chatty – a chatty writing style is friendly and informal

Developing the language skills to build an argument and to write persuasively is crucial if you’re to write outstanding essays every time. In this article, we’re going to equip you with the words and phrases you need to write a top-notch essay, along with examples of how to utilise them.

These are the tenets that will guide you in your speech writing process (and pretty much anything else you want to write). Know the purpose: What are you trying to accomplish with your speech? Educate, inspire, entertain, argue a point?

Step 1: Begin with a speech overview or outline. Are you in a hurry? Without time to read a whole page? Grab ... The Quick How to Write a Speech Checklist And come back to get the details later. Before you start writing you need to know: WHO you are writing your speech for (your target audience) WHY you are preparing this speech.

Words that you can use in speech and writing constitute your active vocabulary (also called functional vocabulary). You, of course, understand these words while reading and listening as well. Think of words such as eat, sell, drink, see, and cook.