ReviseSociology

A level sociology revision – education, families, research methods, crime and deviance and more!

Positivism and Interpretivism in Social Research

Positivists believe society shapes the individual and use quantitative methods, Interpretivists believe individuals shape society and use qualitative methods.

Table of Contents

Last Updated on February 3, 2023 by Karl Thompson

Positivism and Interpretivism are the two basic approaches to research methods in Sociology. Positivist prefer scientific quantitative methods, while Interpretivists prefer humanistic qualitative methods. This post provides a very brief overview of the two.

Please enable JavaScript

- Positivists see society as shaping the individual and believe that ‘social facts’ shape individual action.

- Sociology can and should use the same methods and approaches to study the social world that “natural” sciences such as biology and physics use to investigate the physical world.

- By adopting “scientific” techniques sociologists should be able, eventually, to uncover the laws that govern societies just as scientists have discovered the laws that govern the physical world.

- Positivists prefer quantitative methods such as social surveys, structured questionnaires and official statistics because these have good reliability and representativeness.

- The positivist tradition stresses the importance of doing quantitative research such as large scale surveys in order to get an overview of society as a whole and to uncover social trends, such as the relationship between educational achievement and social class. This type of sociology is more interested in trends and patterns rather than individuals.

- In positivist research, sociologists tend to look for relationships, or ‘correlations’ between two or more variables. This is known as the comparative method.

Interpretivism

- Interpretivists , or anti-positivists argue that individuals are not just puppets who react to external social forces as Positivists believe.

- According to Interpretivists individuals are intricate and complex and different people experience and understand the same ‘objective reality’ in very different ways and have their own, often very different, reasons for acting in the world, thus scientific methods are not appropriate.

- Intepretivist research methods derive from ‘ social action theory ‘

- An Interpretivist approach to social research would be much more qualitative, using methods such as unstructured interviews or participant observation

- Interpretivists argue that in order to understand human action we need to achieve ‘Verstehen‘, or empathetic understanding – we need to see the world through the eyes of the actors doing the acting.

- Intereptivists actually criticise ‘scientific sociology’ (Positivism) because many of the statistics it relies on are themselves socially constructed.

Positivism and Interpretivism Summary Grid

Positivism and Interpretivism FAQ

Positivism is a top down macro approach in sociology which uses quantitative methods to find the general laws of society, Interpretivism is a micro approach which uses qualitative methods to gain an empathetic understanding of why people act from their own understanding/ interpretation.

Positivism is a scientific approach social research developed by August Comte in the mid-19th century and developed by Emile Durkheim. It involves using quantitative methods to study social facts to uncover the objective laws of society.

Durkehims’ study of suicide is a good example of a Positivist research study. He used official statistics and other quantitative data to analyse why the suicide rate varied from country to country.

Interpretivism is an approach to social research first developed by Max Weber in early 19th century. He believed we needed to understand the motives for people’s actions to fully understand why they acted, aiming for what he called Verstehen, or empathetic understanding. Intepretivists use qualitative research methods as they are best for getting more in-depth information about the way people interpret their own actions.

Any study which aims to understand the world from the point of view of the participants, so most participant observation studies are examples, such as Paul Wills’ Learning to Labour and Venkatesh’ Gang Leader for a Day.

Absolutely, yes. In fact many contemporary research studies combine elements of quantitative and qualitative research to achieve greater validity, reliability and representativeness.

Theory and Methods A Level Sociology Revision Bundle

If you like this sort of thing, then you might like my Theory and Methods Revision Bundle – specifically designed to get students through the theory and methods sections of A level sociology papers 1 and 3.

Contents include:

- 74 pages of revision notes

- 15 mind maps on various topics within theory and methods

- Five theory and methods essays

- ‘How to write methods in context essays’.

Signposting and Related Posts

Links to more detailed posts on Positivism and Social Action Theory are embedded in the text above. Other posts you might like include:

Positivism in Social Research

Max Weber’s Social Action Theory

The Presentation of the Self in Everyday Life, A Summary

Links to all of my research methods posts can be found at my main research methods page .

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

7 thoughts on “Positivism and Interpretivism in Social Research”

really a great and academic one…thank you

we appreciate your effort

This helped so much for my research methods paper ! ! !

Does the semi structured interview fall the interpretivist framework?

Hi, in a way I guess it does!

Does triangulation solves the differences between positivism and interpretivism?

It’s better to explain with example,but this explanation is very good.thnks…

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Discover more from ReviseSociology

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

Interpretivism Paradigm & Research Philosophy

Charlotte Nickerson

Research Assistant at Harvard University

Undergraduate at Harvard University

Charlotte Nickerson is a student at Harvard University obsessed with the intersection of mental health, productivity, and design.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

The interpretivist paradigm is a research approach in sociology that focuses on understanding the subjective meanings and experiences of individuals within their social context.

Key Takeaways

- Interpretivism is an approach to social science that asserts that understanding the beliefs, motivations, and reasoning of individuals in a social situation is essential to decoding the meaning of the data that can be collected around a phenomenon.

- There are numerous interpretivist approaches to sociology, three of the most influential of which are hermeneutics, phenomenology and ethnomethodology, and symbolic interactionism.

- Sociologists who have adopted an interpretivists approach include Weber, Garfinkle, Bulmer, Goffman, Cooley, Mead, and Husser.

- Interpretivists use both qualitative and quantitative research methods. However, they believe that there is no one “right path” to knowledge, thus rejecting the idea that there is one methodology that will consistently get at the “truth” of a phenomenon.

- Interpretivist approaches to research differ from positivist ones in their emphasis on qualitative data and focus on context.

The Interpretivist Paradigm

Interpretivism uses qualitative research methods that focus on individuals” beliefs, motivations, and reasoning over quantitative data to gain understanding of social interactions.

Interpretivists assume that access to reality happens through social constructions such as language, consciousness, shared meanings, and instruments (Myers, 2008).

What is a Paradigm?

A paradigm is a set of ideas and beliefs which provide a framework or model which research can follow. A paradigm defines existing knowledge, the nature of the problem(s) to be investigated, appropriate methods of investigation, and the way data should be analyzed and interpreted.

The interpretivist paradigm developed as a critique of positivism in the social sciences

Interpretivism has its roots in idealistic philosophy. The umbrella term has also been used to group together schools of thought ranging from social constructivism to phenomenology and hermeneutics: approaches that reject the view that meaning exists in the world independently of people”s consciousness and interpretation.

Because meaning exists through the lens of people, interpretivist approaches to social science consider it important for researchers to appreciate the differences between people, and seek to understand how these differences inform how people find meaning.

The Interpretivist Assumptions

The interpretive approach is based on the following assumptions:

Human life can only be understood from within

According to interpretivism, individuals have consciousness. This means that they are not merely coerced puppets that react to social forces in the way that positivists mean. This has the result that people in a society are intricate and complex.

Different people in a society experience and understand the same “objective” reality in different ways, and have individual reasons for their actions (Alharahshel & Pius, 2020; Bhattacherjee, 2012).

This more sense-based approach of interpretivism to research has roots in anthropology, sociology, psychology, linguistics, and semiotics, and has been used since the early 19th century, long before the development of positivist sociology.

The social world does not “exist” independently of human knowledge

Interpretivists do not deny that there is an external reality. However, they do not accept that there is an independently knowable reality.

Contrary to positivist approaches to sociology, interpretivists assert that all research is influenced and shaped by the pre-existing theories and worldviews of the researchers.

Terms, procedures, and data used in research have meaning because a group of academics have agreed that these things have meaning. This makes research a socially constructed activity, which means phenomena is created by society and not naturally occurring. It will vary from culture to culture.

Consequently, the reality that research tells us is also socially constructed (Alharahshel & Pius, 2020).

Research should be based on qualitative methods

Interpretivists also use a broad range of qualitative methods . They also accept reflective discussions of how researchers do research, considering these to be prized sources of knowledge and understanding.

This is in contrast to post positivists, who generally consider their reflections and personal stories of researchers to be unacceptable as research because they are neither scientific nor objective (Smith, 1993).

The term interpretive research is often used synonymously with qualitative research , but the two concepts are different. Interpretive research is a research paradigm, or set of common beliefs and agreements shared between scientists about how problems should be understood and addressed (Kuhn, 1970).

Because interpretivists see social reality as embedded within and impossible to abstract from their social settings, they attempt to make “sense” of reality rather than testing hypotheses.

Research should be based on a grounded theory

There can be causal explanation in sociology but there is no need for a hypothesis before starting research. By stating an hypothesis at the start of the study Glaser and Strauss argue that researchers run the risk of imposing their own views on the data rather than those of the actors being researched.

Instead, there should be a grounded theory which means allowing ideas to emerge as the data is collected which can later be used to produce a testable hypothesis.

Research Design

Interpretivists believe that there is no particular right or correct path to knowledge, and no special method that automatically leads to intellectual progress (Smith, 1993). This means that interpretivists are antifoundationalists.

Interpretivists, however, accept that there are standards that guide research. However, they believe that these standards cannot be universal. Instead, interpretivists believe that research standards are the products of a particular group or culture

Interpretivists do not always abandon standards such as the rules of the scientific method; they simply accept that whatever standards are used are subjective, and potentially able to fail, rather than objective and universal (Smith, 1993).

Qualitative Methods

Qualitative data is virtually any type of information that can be observed and recorded, not numerical, and can be in the form of written or verbal communication.

Interpretivists can collect qualitative data using a variety of techniques. The most frequent of these is interviews. These can manifest in many forms, such as face-to-face, over the telephone, or f ocus groups . Another technique for interpretivist data collection is observation.

Observation can include direct observation, a technique common to case research where the researcher is a neutral and passive external observer and is not involved in the phenomena that they are studying.

Interpretivists can also use documentation as a data collecting technique, collecting external and internal documents , such as memos, emails, annual reports, financial statements, newspaper articles, websites, and so on, to cast further insight into a phenomenon of interest or to corroborate other forms of evidence (Smith, 1993).

Case Research

Case research is an intensive, longitudinal study of a phenomenon at least one research site that intends to derive detailed, contextualized inferences and understand the dynamics that underlie the phenomenon that is being studied.

In this research design, the case researcher is a neutral observer, rather than an active participant. In the end, drawing meaningful inferences from case research largely depends on the observational skills and integrative abilities of the research (Schwartz-Shea & Yanow, 2013).

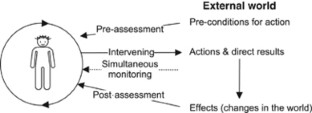

Action Research

Action research, meanwhile, is a qualitative albeit positivist research design aimed at testing, rather than building theories.

Action research designs interaction, assuming that complex social phenomena are best understood by introducing changes, interventions, or “Actions” into the phenomena being studied and observing the outcomes of such actions on that phenomena.

Usually, the researcher in this method is a consultant or organizational member embedded into a social context who initiates an action in response to a social problem, and examines how their action influences the phenomenon while also learning and generating insights about the relationship between the action and the phenomenon.

Some examples of actions may include organizational changes, such as through introducing people or technology, initiated with the goal of improving an organization”s performance or profitability as a business.

The researcher”s choice of actions may be based on theory which explains why and how certain actions could bring forth desired social changes (Schwartz-Shea & Yanow, 2013).

Interpretivist Sociological Perspectives

There are three major interpretivist approaches to sociology (Williams, 2000):

Hermeneutics , which refers to the philosophy of interpretation and understanding. Often, Hermeneutics focuses on influential, ancient texts, such as scripture.

Phenomenology and Ethnomethodology , which is a philosophical tradition that seeks to understand the world through directly experiencing the phenomena within it. Ethnomethodology , which has a phenomenological foundation, is the study of how people make sense of and navigate their everyday world through norms and rituals.

Symbolic interaction , which accepts symbols as culturally derived social objects that have shared meanings. These symbols provide a means to construct reality.

Hermeneutics

Originally, the term hermeneutics referred exclusively to the study of sacred texts such as the Talmud or the Bible.

Hermeneuticists originally used various methods to get at the meaning of these texts, such as through studying the meaning of terms and phrases from the document in other writings from the same era, the social and political context in which the passage was written, and the way the concepts discussed are used in other parts of the document (Williams, 2000).

Gradually, however, hermeneutics expanded beyond this original meaning to include understanding human action in context.

There are many variations on hermeneutics; however, Smith (1991) concluded that they all share two characteristics in common:

An emphasis on the importance of language in understanding, because language can both limit and make possible what people can say,

An emphasis on the context, particularly the historical one, as a frame for understanding, because human behavior and ideas must be understood in context, rather than in isolation.

Hermeneutics has several different subcategories, including validation, critical, and philosophical. The first of these, validation, is based on post positivism and assumes that hermeneutics can be a scientific way to find the truth.

Critical hermeneutics is focused on critical theory, and aims to highlight the historical conditions that lead to oppression.

Finally, philosophical hermeneutics aims to develop understanding and rejects the idea that there is a certain research method that will uncover the truth without fail (Smith, 1991).

Phenomenology

Phenomenology is a type of social action theory that focuses on studying people’s perceptions of the world.

Understanding different perspectives often call for different methods of research and different ways of reporting results. Research methods that attempt to examine the subjective perceptions of the person being studied are often called phenomenological research methods.

Interpretivists generally tend to use qualitative methods such as case studies and ethnography, writing reports that are rich in detail in order to depict the context needed for understanding.

Ethnography

Ethnography, a research method derived largely from anthropology, emphasizes studying a phenomenon within the context of its culture.

In practice, an ethnographic researcher must immerse themself into a social culture over an extended period of time and engage, observe, and record the daily life of the culture being studied and its social participants within their natural setting.

In addition, ethnographic researchers must take extensive field notes and narrate their experience in descriptive detail so that readers can experience the same culture as the researcher.

This gives the researcher two roles: relying on their unique knowledge and engagement to generate insights, and convincing the scientific community that this behavior applies across different situations (Schwandt, 1994).

Symbolic Interactionism

Symbolic interactionism starts which the assumptions that humans inhabit a symbolic world, in which symbols, such as language, have a shared meaning.

The social world is therefore constructed by the meaning that individual attach to events and phenomena and these are transmitted across generations through language.

A central concept of symbolic interactionism is the Self , which allows individuals to calculate the effects of their actions.

Interpretivist Research Designs

Interpretivists can collect qualitative data using a variety of techniques. The most frequent of these are interviews. These can manifest in many forms, such as face-to-face, over the telephone, or in focus groups.

Another technique for interpretivist data collection is observation. Observation can include direct observation, a technique common to case research where the researcher is a neutral and passive external observer and is not involved in the phenomena that they are studying.

Thirdly, interpretivists can use documentation as a data collecting technique, collecting external and internal documents, such as memos, emails, annual reports, financial statements, newspaper articles, websites, and so on — to cast further insight into a phenomenon of interest or to corroborate other forms of evidence (Smith, 1993).

Some examples of actions may include organizational changes, such as through introducing people or technology, initiated with the goal of improving an organization’s performance or profitability as a business.

Examples of Interpretive Research

Decision making in businesses.

Although interpretive research tends to rely heavily on qualitative data, quantitative data can add more precision and create a clearer understanding of the phenomenon being studied than qualitative data.

For example, Eisenhardt (1989) conducted an interpretive study of decision-making in high-velocity firms.

Eisenhardt collected numerical data on how long it took each firm to make certain strategic decisions (ranging from 1.5 months to 18 months), how many decision alternatives were considered for each decision, and surveyed her respondents to capture their perceptions of organizational conflict.

This numerical data helped Eisenhardt to clearly distinguish high-speed decision making firms from low-speed decision makers without relying on respondents” subjective perceptions.

This differentiation then allowed Eisenhardt to examine the number of decision alternatives considered by and the extent of conflict in high-speed and low-speed firms.

Eisenhardt”s study is one example of how interpretivist researchers can use a mixture of quantitative and qualitative data to study their phenomena of interest.

Teaching and Technology

Waxman and Huang (1996) conducted an interpretivist study on the relationship between computers and teaching strategies.

While positivists and post positivists may use the data from that study to make a general statement about the relationship between computers and teaching strategies, interpretivists would argue that the context of the study could alter this general conclusion entirely.

For example, Waxman and Huang (1996) mention in their paper that the school district where the data were collected had provided training for teachers that emphasized the use of “constructivist” approaches to teaching and learning.

This training may mean that the study would have generated different results in a school district where teachers were provided extensive training on a different teaching method.

Interpretivists are concerned about how data are situated, and how this context can affect the data.

Interpretivism vs. Positivism

Whereas positivism looks for universals based on data, interpretivism looks for an understanding of a particular context, because this context is critical to interpreting the data gathered.

Generally, interpretivist research is prepared to sacrifice reliability and representativeness for greater validity while positivism requires research to be valid, reliable, and representative.

While a positivist may use largely quantitative research methods, official statistics, social surveys, questionnaires, and structured interviews to conduct research, interpretivists may rely on qualitative methods, such as personal documents , participant observation, and unstructured interviews (Alharahshel & Pius, 2020; Bhattacherjee, 2012).

Interprevists and positivists also differ in how they see the relationship between the society and the individual. Positivists believe that society shapes the individual, and that society consists of “social facts” that exercise coercive control over individuals.

This means that people”s actions can generally be explained by the social norms that they have been exposed to through socialization, social class, gender, and ethnic background.

Many positivist researchers view interpretive research as erroneous and biased, given the subjective nature of qualitative data collection and the process of interpretation used in such research.

However, the failure of many positivist techniques to generate insights has resulted in a resurgence of interest in interpretive research since the 1970s, now informed with exacting methods and criteria to ensure the reliability and validity of interpretive inferences (Bhattacherjee, 2012).

Alharahsheh, H. H., & Pius, A. (2020). A review of key paradigms: Positivism VS interpretivism . Global Academic Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 2 (3), 39-43.

Bhattacherjee, A. (2012). Social science research: Principles, methods, and practices . University of South Florida.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Making fast strategic decisions in high-velocity environments. Academy of Management Journal, 32 (3), 543-576.

Goldkuhl, G. (2012). Pragmatism vs interpretivism in qualitative information systems research . European journal of information systems, 21 (2), 135-146.

Kuhn, T. S. (1970). Criticism and the growth of knowledge: Volume 4: Proceedings of the International Colloquium in the Philosophy of Science , London, 1965 (Vol. 4). Cambridge University Press.

Myers, M. D. (2008). Qualitative Research in Business & Management . SAGE Publications.

Schwandt, T. A. (1994). Constructivist, interpretivist approaches to human inquiry. Handbook of qualitative research, 1 (1994), 118-137.

Schwartz-Shea, P., & Yanow, D. (2013). Interpretive research design: Concepts and processes . Routledge.

Smith, D. G. (1991). Hermeneutic inquiry: The hermeneutic imagination and the pedagogic text. Forms of curriculum inquiry , 3.

Smith, J. K. (1993). After the demise of empiricism: The problem of judging social and education inquiry .

Waxman, H. C., & Huang, S. Y. L. (1996). Classroom instruction differences by level of technology use in middle school mathematics. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 14 (2), 157-169.

Walsham, G. (1995). The emergence of interpretivism in IS research . Information systems research, 6 (4), 376-394.

Williams, M. (2000). Interpretivism and generalisation. Sociology, 34 (2), 209-224.

Research Philosophy & Paradigms

Positivism, Interpretivism & Pragmatism, Explained Simply

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewer: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | June 2023

Research philosophy is one of those things that students tend to either gloss over or become utterly confused by when undertaking formal academic research for the first time. And understandably so – it’s all rather fluffy and conceptual. However, understanding the philosophical underpinnings of your research is genuinely important as it directly impacts how you develop your research methodology.

In this post, we’ll explain what research philosophy is , what the main research paradigms are and how these play out in the real world, using loads of practical examples . To keep this all as digestible as possible, we are admittedly going to simplify things somewhat and we’re not going to dive into the finer details such as ontology, epistemology and axiology (we’ll save those brain benders for another post!). Nevertheless, this post should set you up with a solid foundational understanding of what research philosophy and research paradigms are, and what they mean for your project.

Overview: Research Philosophy

- What is a research philosophy or paradigm ?

- Positivism 101

- Interpretivism 101

- Pragmatism 101

- Choosing your research philosophy

What is a research philosophy or paradigm?

Research philosophy and research paradigm are terms that tend to be used pretty loosely, even interchangeably. Broadly speaking, they both refer to the set of beliefs, assumptions, and principles that underlie the way you approach your study (whether that’s a dissertation, thesis or any other sort of academic research project).

For example, one philosophical assumption could be that there is an external reality that exists independent of our perceptions (i.e., an objective reality), whereas an alternative assumption could be that reality is constructed by the observer (i.e., a subjective reality). Naturally, these assumptions have quite an impact on how you approach your study (more on this later…).

The research philosophy and research paradigm also encapsulate the nature of the knowledge that you seek to obtain by undertaking your study. In other words, your philosophy reflects what sort of knowledge and insight you believe you can realistically gain by undertaking your research project. For example, you might expect to find a concrete, absolute type of answer to your research question , or you might anticipate that things will turn out to be more nuanced and less directly calculable and measurable . Put another way, it’s about whether you expect “hard”, clean answers or softer, more opaque ones.

So, what’s the difference between research philosophy and paradigm?

Well, it depends on who you ask. Different textbooks will present slightly different definitions, with some saying that philosophy is about the researcher themselves while the paradigm is about the approach to the study . Others will use the two terms interchangeably. And others will say that the research philosophy is the top-level category and paradigms are the pre-packaged combinations of philosophical assumptions and expectations.

To keep things simple in this video, we’ll avoid getting tangled up in the terminology and rather focus on the shared focus of both these terms – that is that they both describe (or at least involve) the set of beliefs, assumptions, and principles that underlie the way you approach your study .

Importantly, your research philosophy and/or paradigm form the foundation of your study . More specifically, they will have a direct influence on your research methodology , including your research design , the data collection and analysis techniques you adopt, and of course, how you interpret your results. So, it’s important to understand the philosophy that underlies your research to ensure that the rest of your methodological decisions are well-aligned .

So, what are the options?

We’ll be straight with you – research philosophy is a rabbit hole (as with anything philosophy-related) and, as a result, there are many different approaches (or paradigms) you can take, each with its own perspective on the nature of reality and knowledge . To keep things simple though, we’ll focus on the “big three”, namely positivism , interpretivism and pragmatism . Understanding these three is a solid starting point and, in many cases, will be all you need.

Paradigm 1: Positivism

When you think positivism, think hard sciences – physics, biology, astronomy, etc. Simply put, positivism is rooted in the belief that knowledge can be obtained through objective observations and measurements . In other words, the positivist philosophy assumes that answers can be found by carefully measuring and analysing data, particularly numerical data .

As a research paradigm, positivism typically manifests in methodologies that make use of quantitative data , and oftentimes (but not always) adopt experimental or quasi-experimental research designs. Quite often, the focus is on causal relationships – in other words, understanding which variables affect other variables, in what way and to what extent. As a result, studies with a positivist research philosophy typically aim for objectivity, generalisability and replicability of findings.

Let’s look at an example of positivism to make things a little more tangible.

Assume you wanted to investigate the relationship between a particular dietary supplement and weight loss. In this case, you could design a randomised controlled trial (RCT) where you assign participants to either a control group (who do not receive the supplement) or an intervention group (who do receive the supplement). With this design in place, you could measure each participant’s weight before and after the study and then use various quantitative analysis methods to assess whether there’s a statistically significant difference in weight loss between the two groups. By doing so, you could infer a causal relationship between the dietary supplement and weight loss, based on objective measurements and rigorous experimental design.

As you can see in this example, the underlying assumptions and beliefs revolve around the viewpoint that knowledge and insight can be obtained through carefully controlling the environment, manipulating variables and analysing the resulting numerical data . Therefore, this sort of study would adopt a positivistic research philosophy. This is quite common for studies within the hard sciences – so much so that research philosophy is often just assumed to be positivistic and there’s no discussion of it within the methodology section of a dissertation or thesis.

Paradigm 2: Interpretivism

If you can imagine a spectrum of research paradigms, interpretivism would sit more or less on the opposite side of the spectrum from positivism. Essentially, interpretivism takes the position that reality is socially constructed . In other words, that reality is subjective , and is constructed by the observer through their experience of it , rather than being independent of the observer (which, if you recall, is what positivism assumes).

The interpretivist paradigm typically underlies studies where the research aims involve attempting to understand the meanings and interpretations that people assign to their experiences. An interpretivistic philosophy also typically manifests in the adoption of a qualitative methodology , relying on data collection methods such as interviews , observations , and textual analysis . These types of studies commonly explore complex social phenomena and individual perspectives, which are naturally more subjective and nuanced.

Let’s look at an example of the interpretivist approach in action:

Assume that you’re interested in understanding the experiences of individuals suffering from chronic pain. In this case, you might conduct in-depth interviews with a group of participants and ask open-ended questions about their pain, its impact on their lives, coping strategies, and their overall experience and perceptions of living with pain. You would then transcribe those interviews and analyse the transcripts, using thematic analysis to identify recurring themes and patterns. Based on that analysis, you’d be able to better understand the experiences of these individuals, thereby satisfying your original research aim.

As you can see in this example, the underlying assumptions and beliefs revolve around the viewpoint that insight can be obtained through engaging in conversation with and exploring the subjective experiences of people (as opposed to collecting numerical data and trying to measure and calculate it). Therefore, this sort of study would adopt an interpretivistic research philosophy. Ultimately, if you’re looking to understand people’s lived experiences , you have to operate on the assumption that knowledge can be generated by exploring people’s viewpoints, as subjective as they may be.

Paradigm 3: Pragmatism

Now that we’ve looked at the two opposing ends of the research philosophy spectrum – positivism and interpretivism, you can probably see that both of the positions have their merits , and that they both function as tools for different jobs . More specifically, they lend themselves to different types of research aims, objectives and research questions . But what happens when your study doesn’t fall into a clear-cut category and involves exploring both “hard” and “soft” phenomena? Enter pragmatism…

As the name suggests, pragmatism takes a more practical and flexible approach, focusing on the usefulness and applicability of research findings , rather than an all-or-nothing, mutually exclusive philosophical position. This allows you, as the researcher, to explore research aims that cross philosophical boundaries, using different perspectives for different aspects of the study .

With a pragmatic research paradigm, both quantitative and qualitative methods can play a part, depending on the research questions and the context of the study. This often manifests in studies that adopt a mixed-method approach , utilising a combination of different data types and analysis methods. Ultimately, the pragmatist adopts a problem-solving mindset , seeking practical ways to achieve diverse research aims.

Let’s look at an example of pragmatism in action:

Imagine that you want to investigate the effectiveness of a new teaching method in improving student learning outcomes. In this case, you might adopt a mixed-methods approach, which makes use of both quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis techniques. One part of your project could involve comparing standardised test results from an intervention group (students that received the new teaching method) and a control group (students that received the traditional teaching method). Additionally, you might conduct in-person interviews with a smaller group of students from both groups, to gather qualitative data on their perceptions and preferences regarding the respective teaching methods.

As you can see in this example, the pragmatist’s approach can incorporate both quantitative and qualitative data . This allows the researcher to develop a more holistic, comprehensive understanding of the teaching method’s efficacy and practical implications, with a synthesis of both types of data . Naturally, this type of insight is incredibly valuable in this case, as it’s essential to understand not just the impact of the teaching method on test results, but also on the students themselves!

Wrapping Up: Philosophies & Paradigms

Now that we’ve unpacked the “big three” research philosophies or paradigms – positivism, interpretivism and pragmatism, hopefully, you can see that research philosophy underlies all of the methodological decisions you’ll make in your study. In many ways, it’s less a case of you choosing your research philosophy and more a case of it choosing you (or at least, being revealed to you), based on the nature of your research aims and research questions .

- Research philosophies and paradigms encapsulate the set of beliefs, assumptions, and principles that guide the way you, as the researcher, approach your study and develop your methodology.

- Positivism is rooted in the belief that reality is independent of the observer, and consequently, that knowledge can be obtained through objective observations and measurements.

- Interpretivism takes the (opposing) position that reality is subjectively constructed by the observer through their experience of it, rather than being an independent thing.

- Pragmatism attempts to find a middle ground, focusing on the usefulness and applicability of research findings, rather than an all-or-nothing, mutually exclusive philosophical position.

If you’d like to learn more about research philosophy, research paradigms and research methodology more generally, be sure to check out the rest of the Grad Coach blog . Alternatively, if you’d like hands-on help with your research, consider our private coaching service , where we guide you through each stage of the research journey, step by step.

Psst… there’s more (for free)

This post is part of our dissertation mini-course, which covers everything you need to get started with your dissertation, thesis or research project.

You Might Also Like:

13 Comments

was very useful for me, I had no idea what a philosophy is, and what type of philosophy of my study. thank you

Thanks for this explanation, is so good for me

You contributed much to my master thesis development and I wish to have again your support for PhD program through research.

the way of you explanation very good keep it up/continuous just like this

Very precise stuff. It has been of great use to me. It has greatly helped me to sharpen my PhD research project!

Very clear and very helpful explanation above. I have clearly understand the explanation.

Very clear and useful. Thanks

Thanks so much for your insightful explanations of the research philosophies that confuse me

I would like to thank Grad Coach TV or Youtube organizers and presenters. Since then, I have been able to learn a lot by finding very informative posts from them.

thank you so much for this valuable and explicit explanation,cheers

Hey, at last i have gained insight on which philosophy to use as i had little understanding on their applicability to my current research. Thanks

Tremendously useful

thank you and God bless you. This was very helpful, I had no understanding before this.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Interpretivism (interpretivist) Research Philosophy

Interpretivism, also known as interpretivist involves researchers to interpret elements of the study, thus interpretivism integrates human interest into a study. Accordingly, “interpretive researchers assume that access to reality (given or socially constructed) is only through social constructions such as language, consciousness, shared meanings, and instruments”. [1] Development of interpretivist philosophy is based on the critique of positivism in social sciences. Accordingly, this philosophy emphasizes qualitative analysis over quantitative analysis.

Interpretivism is “associated with the philosophical position of idealism, and is used to group together diverse approaches, including social constructivism , phenomenology and hermeneutics; approaches that reject the objectivist view that meaning resides within the world independently of consciousness” [2] . According to interpretivist approach, it is important for the researcher as a social actor to appreciate differences between people. [3] Moreover, interpretivism studies usually focus on meaning and may employ multiple methods in order to reflect different aspects of the issue.

Important Aspects of Interpretivism

Interpretivist approach is based on naturalistic approach of data collection such as interviews and observations . Secondary data research is also popular with interpretivism philosophy. In this type of studies, meanings emerge usually towards the end of the research process.

The most noteworthy variations of interpretivism include the following:

- Hermeneutics refers to the philosophy of interpretation and understanding. Hermeneutics mainly focuses on biblical texts and wisdom literature and as such, has a little relevance to business studies.

- Phenomenology is “the philosophical tradition that seeks to understand the world through directly experiencing the phenomena”. [4]

- Symbolic interactionism accepts symbols as culturally derived social objects having shared meanings. According to symbolic interactionism symbols provide the means by which reality is constructed

In general interpretivist approach is based on the following beliefs:

1. Relativist ontology . This approach perceives reality as intersubjectively that is based on meanings and understandings on social and experiential levels.

2. Transactional or subjectivist epistemology. According to this approach, people cannot be separated from their knowledge; therefore there is a clear link between the researcher and research subject.

The basic differences between positivism and interpretivism are illustrated by Pizam and Mansfeld (2009) in the following manner:

Assumptions and research philosophies

The use of interpretivism approach in business studies involves the following principles as suggested by Klein and Myers (1999)

- The Fundamental Principle of the Hermeneutic Circle.

- The Principle of Contextualization

- The Principle of Interaction between the Researchers and the Subjects

- The Principle of Abstraction and Generalization

- The Principle of Dialogical Reasoning

- The Principle of Multiple Interpretations

- The Principle of Suspicion

Advantages and Disadvantages of Interpretivism

Main disadvantages associated with interpretivism relate to subjective nature of this approach and great room for bias on behalf of researcher. Primary data generated in interpretivist studies cannot be generalized since data is heavily impacted by personal viewpoint and values. Therefore, reliability and representativeness of data is undermined to a certain extent as well.

On the positive side, thanks to adoption of interpretivism, qualitative research areas such as cross-cultural differences in organizations, issues of ethics, leadership and analysis of factors impacting leadership etc. can be studied in a great level of depth. Primary data generated via Interpretivism studies might be associated with a high level of validity because data in such studies tends to be trustworthy and honest.

Generally, if you are following interpretivism research philosophy in your dissertation the depth of discussion of research philosophy depends on the level of your studies. For a dissertation at Bachelor’s level it suffices to specify that you are following Interpretivism approach and to describe the essence of this approach in a short paragraph. For a dissertation at Master’s level discussion needs to be expanded into 2-3 paragraphs to include justification of your choice for interpretivist approach.

At a PhD level, on the other hand, discussion of research philosophy can cover several pages and you are expected to discuss the essence of interpretivism by referring to several relevant secondary data sources. Your justification for the selection of interpretivism need to be offered in a succinct way in about two paragraphs.

My e-book, The Ultimate Guide to Writing a Dissertation in Business Studies: a step by step assistance contains discussions of theory and application of research philosophy. The e-book also explains all stages of the research process starting from the selection of the research area to writing personal reflection. Important elements of dissertations such as research philosophy , research approach , research design , methods of data collection and data analysis are explained in this e-book in simple words.

John Dudovskiy

[1] Myers, M.D. (2008) “Qualitative Research in Business & Management” SAGE Publications

[2] Collins, H. (2010) “Creative Research: The Theory and Practice of Research for the Creative Industries” AVA Publications

[3] Source: Saunders, M., Lewis, P. & Thornhill, A. (2012) “Research Methods for Business Students” 6 th edition, Pearson Education Limited

[4] Littlejohn, S.W. & Foss, K.A. (2009) “Encyclopedia of Communication Theory” Vol.1, SAGE Publication

Introduction to positivism, interpretivism and critical theory

Affiliation.

- 1 Open University, Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire, England.

- PMID: 29546962

- DOI: 10.7748/nr.2018.e1466

Background: There are three commonly known philosophical research paradigms used to guide research methods and analysis: positivism, interpretivism and critical theory. Being able to justify the decision to adopt or reject a philosophy should be part of the basis of research. It is therefore important to understand these paradigms, their origins and principles, and to decide which is appropriate for a study and inform its design, methodology and analysis.

Aim: To help those new to research philosophy by explaining positivism, interpretivism and critical theory.

Discussion: Positivism resulted from foundationalism and empiricism; positivists value objectivity and proving or disproving hypotheses. Interpretivism is in direct opposition to positivism; it originated from principles developed by Kant and values subjectivity. Critical theory originated in the Frankfurt School and considers the wider oppressive nature of politics or societal influences, and often includes feminist research.

Conclusion: This paper introduces the historical context of three well-referenced research philosophies and explains the common principles and values of each.

Implications for practice: The paper enables nurse researchers to make informed and rational decisions when embarking on research.

Keywords: critical theory; interpretivism; novice researchers; nursing research; positivism; research philosophy.

©2018 RCN Publishing Company Ltd. All rights reserved. Not to be copied, transmitted or recorded in any way, in whole or part, without prior permission of the publishers.

- Nursing Research*

- Philosophy, Nursing*

Interpretivism

Often contrasted with Positivism is Interpretivism. The starting point for Interpretivism – which is sometimes called Anti-Positivism – is that knowledge in the human and social sciences cannot conform to the model of natural science because there are features of human experience that cannot objectively be “known”. This might include emotions; understandings; values; feelings; subjectivities; socio-cultural factors; historical influence; and other meaningful aspects of human being. Instead of finding “truth” the Interpretivist aims to generate understanding and often adopts a relativist position.

Qualitative methods are preferred as ways to investigate these phenomena. Data collected might be unstructured (or “messy”) and correspondingly a range of techniques for approaching data collection have been developed. Interpretivism acknowledges that it is impossible to remove cultural and individual influence from research, often instead making a virtue of the positionality of the researcher and the socio-cultural context of a study.

One key consideration here is the purported validity of qualitative research. Interpretivism tends to emphasize the subjective over the objective. If the starting point for an investigation is that we can’t fully and objectively know the world, how can we do research into this without everything being a matter of opinion? Essentially Positivism and Interpretivism retain different ontologies and epistemologies with contrasting notions of rigour and validity (in the broadest rather than statistical sense). Interpretivist research often embraces a relativist epistemology, bringing together different perspectives in search of an overall understanding or narrative.

Kivunja & Kuyini (2017) describe the essential features of Interpretivism as:

- The admission that the social world cannot be understood from the standpoint of an individual

- The belief that realities are multiple and socially constructed

- The acceptance that there is inevitable interaction between the researcher and his or her research participants

- The acceptance that context is vital for knowledge and knowing.

- The belief that knowledge is created by the findings, can be value laden and the values need to be made explicit

- The need to understand the individual rather than universal laws

- The belief that causes and effects are mutually interdependent

- The belief that contextual factors need to be taken into consideration in any systematic pursuit of understanding

Interpretivism as a research paradigm is often accompanied by Constructivism as an ontological and epistemological grounding. Many learning theories emphasize Constructivism as an organising principle, and Constructivism often underlies aspects of educational research.

Interpretivist Methods : Case Studies; Conversational analysis; Delphi; Description; Document analysis; Interviews; Focus Groups; Grounded theory; Phenomenography; Phenomenology; Thematic analysis

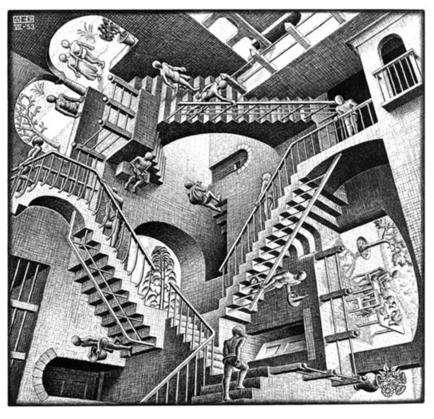

[INSERT Figure 2]

methodological aspects of Positivism and Interpretivism. Positivism Interpretivism Ontology Being in the world Direct access (Naturalism) Indirect access (Idealism) Reality Objective, accessible Subjectively experienced Epistemology Relation between knowledge and reality Objective knowledge of the world is possible supported by appropriate method Objective knowledge of the world is possible supported by appropriate method Epistemological goals Generalisation, abstraction, discovery of law-like relationships Knowledge of specific, concrete cases and examples Basic approach Hypothesis formation and testing Describing and seeking to understand phenomena in context Methodology Focus Description and explanation Understanding and interpretation Research Perspective Detached, objective Embedded in the phenomena under investigation Role of emotions Strict separation between the cognitions and feeling of the researchers Emotional response can be part of coming to understanding Limits of researcher influence Discovery of external, objective reality – minimal influence Object of study is potentially influenced by the activity of the researcher Valued approaches Consistency, clarity, reproducibility, rationality, lack of bias Insight, appreciation of context and prior understanding Fact/value distinction Clear distinction between facts and values Distinction is less rigid, acknowledges entanglement Archetypal research methods Quantitative (e.g. statistical analysis) Qualitative (e.g. case study) Figure 2. Ontology, Epistemology and Methodology across Positivism and Interpretivism (adapted from Carson et al., 2001)

Research Methods Handbook Copyright © 2020 by Rob Farrow; Francisco Iniesto; Martin Weller; and Rebecca Pitt is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Fujita Med J

- v.6(4); 2020

Functions of qualitative research and significance of the interpretivist paradigm in medical and medical education research

Takashi otani.

Graduate School of Education & Human Development, Nagoya University, Nagoya, Aichi, Japan

What is Qualitative Research?

Scientific research in which researchers collect data comprises quantitative and qualitative approaches. The former collects quantitative data using measurements and analyzes these data statistically. The latter acquires qualitative linguistic data, such as interview and observation data, which are analyzed in various scientific ways. It is important to note that both approaches are empirical science.

The dominant focus of medical science and practice has been bio-medical. However, in 1977, Engel (1977) highlighted the necessity of a “bio-psycho-social” model. 1 Since then, our society has also become more multi-/cross-cultural. Therefore, medical research is expected to include a psycho-socio-cultural aspect. Qualitative research can reflect this aspect, as it may investigate factors such as hope, belief, cognition, values, meaning, and the significance of human thoughts and conduct. These factors are subjective and inter-subjective, linguistic and non-linguistic, dynamic and interactional, irrational and contradictory, and are often not measurable quantitatively. In addition, a dominant aspect of education is essentially psycho-socio-cultural. Therefore, a qualitative approach has become indispensable in both medical research and medical education research; today, more qualitative research is conducted in these areas than before.

Research Paradigms in Qualitative Research

The paradigm in quantitative research is positivist without exception, meaning quantitative researchers can ignore the concept of a research paradigm. However, qualitative researchers adopt diverse approaches from very positivist to very interpretivist. Denzin and Lincoln (2017) discussed a comprehensive variety of research paradigms used in qualitative research. 2 Otani (2019) indicated that these paradigms were continuously distributed within the “qualitative research spectrum” ( Figure 1 ). 3 This means that it is necessary for researchers to be aware of different research paradigms to fully understand qualitative research. This is particularly important as most qualitative medical research in Japan, with few exceptions such as Takahashi et al. (2018), 4 has adopted a positivist paradigm rather than an interpretivist paradigm. This may partly be because such positivist qualitative research has an affinity with readers who are accustomed to quantitative research (which is completely positivist). However, it may also be because when qualitative research was introduced into Japan, a positivist paradigm was used. In other words, Japanese qualitative medical research has not yet caught up with international development of the paradigm shift in qualitative research. Therefore, a major challenge for medical qualitative research in Japan is to design and conduct qualitative research using an interpretivist paradigm, and demonstrate the meaningfulness of such an approach.

Spectrum of Qualitative Research

The Qualitative Research Article in This Issue

Fortunately, this issue has one such article, titled “Moving beyond superficial communication to collaborative communication: learning processes and outcomes of interprofessional education in actual medical settings” by Mihoko Ito et al. 5 This is a well-designed and well-conducted interpretivist qualitative study on medical interprofessional education. The authors’ interpretative analysis of interview data is excellent in its depth and significance, and their study offers a model for further qualitative medical and medical education research, both in Japan and internationally.

Research Ethics in Qualitative Research

Research ethics is a crucial issue in qualitative research. For example, in quantitative research, it is possible to anonymize data to become unlinkable, so that even the researcher cannot know to whom the data belong. However, in qualitative research, although it is possible to preserve participant anonymity for readers, it is impossible to also make the data completely anonymous to the researcher. This is because qualitative data include information from which the researcher can identify a participant. This is just one example of how ethical issues differ between qualitative and quantitative research. In the abovementioned article, the authors designed, conducted, and reported their research carefully, meaning there were no ethical problems despite reaching a significant conclusion. Therefore, this article could also offer a model of research ethics of interpretative qualitative research.

Expectation

I hope that the abovementioned article acts as a catalyst for the further development of medical and medical education qualitative research that uses a range of interpretative paradigms.

Conflict of Interest

The author has no conflicts of interest directly relevant to the content of this article.

Pragmatism vs interpretivism in qualitative information systems research

- Research Article

- Published: 20 December 2011

- Volume 21 , pages 135–146, ( 2012 )

Cite this article

- Göran Goldkuhl 1 , 2

21k Accesses

199 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Qualitative research is often associated with interpretivism, but alternatives do exist. Besides critical research and sometimes positivism, qualitative research in information systems can be performed following a paradigm of pragmatism. This paradigm is associated with action, intervention and constructive knowledge. This paper has picked out interpretivism and pragmatism as two possible and important research paradigms for qualitative research in information systems. It clarifies each paradigm in an ideal-typical fashion and then conducts a comparison revealing commonalities and differences. It is stated that a qualitative researcher must either adopt an interpretive stance aiming towards an understanding that is appreciated for being interesting; or a pragmatist stance aiming for constructive knowledge that is appreciated for being useful in action. The possibilities of combining pragmatism and interpretivism in qualitative research in information systems are analysed. A research case (conducted through action research (AR) and design research (DR)) that combines interpretivism and pragmatism is used as an illustration. It is stated in the paper that pragmatism has influenced IS research to a fairly large extent, albeit in a rather implicit way. The paradigmatic foundations are seldom known and explicated. This paper contributes to a further clarification of pragmatism as an explicit research paradigm for qualitative research in information systems. Pragmatism is considered an appropriate paradigm for AR and DR.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis

David Byrne

Research Methodology: An Introduction

Mixed methods research: what it is and what it could be

Rob Timans, Paul Wouters & Johan Heilbron

Arens E (1994) The Logic of Pragmatic Thinking. From Peirce to Habermas. Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands.

Google Scholar

Argyris C, Putnam R and Mclain SD (1985) Action Science. Concepts, Methods and Skills for Research and Intervention. Jossey Bass, San Francisco, CA.

Baskerville R (1999) Investigating information systems with action research. Communication of AIS 2, 1–32.

Baskerville R and Myers M (2004) Special issue on action research in information systems: making IS research relevant to practice – foreword. MIS Quarterly 28 (3), 329–335.

Baskerville R and Pries-Heje J (1999) Grounded action research: a method for understanding IT in practice. Accounting, Management & Information Technology 9, 1–23.

Article Google Scholar

Benbasat I, Goldstein D and Mead M (1987) The case research strategy in studies of information systems. MIS Quarterly 11 (3), 369–386.

Blumer H (1969) Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA.

Boland RJ (1985) Phenomenology: a preferred approach to research on information systems. In Research Methods in Information Systems (M UMFORD E, H IRSCHHEIM R, F ITZGERALD G, W OOD -H ARPER T, Eds), North-Holland, Amsterdam.

Boland RJ (1991) Information systems use as a hermeneutic process. In Information Systems Research: Contemporary Approaches and Emergent Traditions (N ISSEN H-E, K LEIN H, H IRSCHHEIM R, Eds), North-Holland, Amsterdam.

Braa K and Vidgen R (1999) Interpretation, intervention, and reduction in the organizational laboratory: a framework for in-context information system research. Accounting, Management & Information Technology 9, 25–47.

Butler T (1998) Towards a hermeneutic method for interpretive research in information systems. Journal of Information Technology 13, 285–300.

Chua WF (1986) Radical development in accounting thought. The Accounting Review 61 (4), 601–632.

Cole R, Purao S, Rossi M and Sein M (2005) Being proactive: where action research meets design research. Proceedings of the Twenty-sixth International Conference on Information Systems, pp 325–336, Association for Information Systems, Atlanta.

Cronen V (2001) Practical theory, practical art, and the pragmatic-systemic account of inquiry. Communication Theory 11 (1), 14–35.

Davison RM, Martinsons MG and Kock N (2004) Principles of canonical action research. Information Systems Journal 14, 65–86.

Dewey J (Ed.) (1931) The development of American pragmatism. In Philosophy and Civilization. Minton, Balch & Co, New York.

Dewey J (1938) Logic: The Theory of Inquiry. Henry Holt, New York.

Fishman DB (1999) The Case for Pragmatic Psychology. New York University Press, New York.

Fitzgerald B and Howcroft D (1998) Towards resolution of the IS research debate: from polarization to polarity. Journal of Information Technology 13, 313–326.

Gasson S (1998) A social action model of situated information systems design. In Proceedings of IFIP WG8.2 & WG8.6 Joint Working Conference on Information Systems: Current Issues and Future Changes (K EIL M, M C L EAN ER, L ARSEN TJ and L EVINE L), ACM, New York.

Goldkuhl G (2004) Meanings of pragmatism: Ways to conduct information systems research. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Action in Language, Organisations and Information Systems (ALOIS). Linköping University, Linköping.

Goldkuhl G (2007) What does it mean to serve the citizen in e-services? – towards a practical theory founded in socio-instrumental pragmatism. International Journal of Public Information Systems 2007 (3), 135–159.

Goldkuhl G (2008a) Practical inquiry as action research and beyond. In Proceedings of the 16th European Conference on Information Systems (G OLDEN W, A CTON T, C ONBOY K, V AN D ER H EIJDEN H and T UUNAINEN VK, Eds), pp 267–278, Galway, Ireland.

Goldkuhl G (2008b) What kind of pragmatism in information systems research? AIS SIG Prag Inaugural Meeting, Paris.

Goldkuhl G and Lyytinen K (1982) A language action view of information systems. In Proceedings of 3rd International Conference on Informations Systems (G INZBERG and R OSS , Eds), Ann Arbor.

Goles T and Hirschheim R (2000) The paradigm is dead, the paradigm is dead … long live the paradigm: the legacy of Burell and Morgan. Omega 28, 249–268.

Gregor S and Jones D (2007) The anatomy of a design theory. Journal of AIS 8 (5), 312–335.

Hevner AR, March ST, Park J and Ram S (2004) Design science in information systems research. MIS Quarterly 28 (1), 75–15.

Hirschheim R, Klein H and Lyytinen K (1996) Exploring the intellectual structures of information systems development: a social action theoretic analysis. Accounting, Management & Information Technology 6 (1/2), 1–64.

Iivari J (2007) A paradigmatic analysis of information systems as a design science. Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems 19 (2), 39–64.

Iivari J and Venable J (2009) Action research and design science research – seemingly similar but decisively dissimilar. 17th European Conference on Information Systems, Verona.

Joas H (1993) Pragmatism and Social Theory. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL.

Järvinen P (2007) Action research is similar to design science. Quality & Quantity 41, 37–54.

Klein H and Myers M (1999) A set of principles for evaluating and conducting interpretive field studies in information systems. MIS Quarterly 23 (1), 67–94.

Kock N (Ed.) (2007) Information Systems Action Research. An Applied View of Emerging Concepts and Methods. Springer, Berlin.

Book Google Scholar

Kock N and Lau F (2001) Information systems action research: serving two demanding masters. Information Technology & People 14 (1), 6–11.

Kuutti K (1996) Activity theory as a potential framework for human-computer interaction research. In Context and consciousness. Activity Theory and Human-Computer Interaction (N ARDI BA, Ed.), MIT Press, Cambridge.

Lee A (1989) Integrating positivist and interpretive approaches to organizational research. Organization Science 2 (4), 342–365.

Lee A and Nickerson J (2010) Theory as a case of design: lessons for design from the philosophy of science. Proceedings of the 43rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences .

Lee AS, Liebenau J and Degross JI (Eds) (1997) Information Systems and Qualitative Research. Chapman & Hall, London.

Leonardi PM and Barley SR (2008) Materiality and change: challenges to building better theory about technology and organizing. Information and Organization 18, 159–176.

Lovejoy AO (1908) The thirteen pragmatisms. The Journal of Philosophy, Psychology and Scientific Methods 5 (1–2), 5–39.

Madill A, Jordan A and Shirley C (2000) Objectivity and reliability in qualitative analysis: realist, contextualist and radical constructionist epistemologies. British Journal of Psychology 91, 1–20.

Marshall P, Kelder J-A and Perry A (2005) Social constructionism with a twist of pragmatism: a suitable cocktail for information systems research. 16th Australasian Conference on Information Systems, Sydney.

MÅrtensson P and Lee A (2004) Dialogical action research at Omega corporation. MIS Quarterly 28 (3), 507–536.

Mathiassen L (2002) Collaborative practice research. Information Technology & People 15 (4), 321–345.

Mead GH (1934) Mind, Self and Society. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL.

Mead GH (1938) Philosophy of the Act. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL.

Metcalfe M (2008) Pragmatic inquiry. Journal of the Operational Research Society 59, 1091–1099.

Mingers J (2001) Combining IS research methods: Towards a pluralist methodology. Information Systems Research 12 (3), 240–259.

Mumford E, Hirschheim R, Fitzgerald G and Wood-Harper T (Eds) (1985) Research Methods in Information Systems. North-Holland, Amsterdam.

Myers M and Avison D (Eds) (2002a) Qualitative Research in Information Systems: A Reader. Sage, London.

Myers M and Avison D (Eds) (2002b) An introduction to qualitative research in information systems. In Qualitative Research in Information Systems: A Reader. Sage, London.

Chapter Google Scholar

Myers M and Walsham G (1998) Exemplifying interpretive research in information systems: an overview. Journal of Information Technology 13, 233–234.

Nissen H-E, Klein H and Hirschheim R (Eds) (1991) Information Systems Research: Contemporary Approaches and Emergent Traditions. North-Holland, Amsterdam.

Orlikowski WJ (1992) The duality of technology: rethinking the concept of technology in organizations. Organization Science 3 (3), 398–429.

Orlikowski WJ (2000) Using technology and constituting structures: a practice lens for studying technology in organizations. Organization Science 11 (4), 404–428.

Orlikowski WJ (2008) Sociomaterial practices: exploring technology at work. Organization Studies 28 (9), 1435–1448.

Orlikowski WJ and Baroudi JJ (1991) Studying information technology in organizations: research approaches and assumptions. Information Systems Research 2 (1), 1–28.

Peirce CS (1878) How to make our ideas clear. Popular Science Monthly .

Pleasants N (2003) A philosophy for the social sciences: realism, pragmatism, or neither? Foundations of Science 8, 69–87.

Rescher N (2000) Realistic Pragmatism. An Introduction to Pragmatic Philosophy. SUNY Press, Albany, NY.

Rorty R (1980) Pragmatism, relativism and irrationalism. Proceedings and Addresses of the American Philosophical Association 53 (6), 719–738.

Schutz A (1970) On Phenomenology and Social Relations. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL.

Sein M, Henfridsson O, Purao S, Rossi M and Lindgren R (2011) Action design research. MIS Quarterly 35 (1), 37–56.

Shusterman R (2004) Pragmatism and East-Asian thought. Metaphilosophy 35 (1/2), 13–43.

Silverman D (1970) The Theory of Organizations. Heineman, London.

Stevenson C (2005) Practical inquiry/theory in nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing 50 (2), 196–203.

Susman GI and Evered RD (1978) An assessment of the scientific merits of action research. Administrative Science Quarterly 23 (4), 582–603.

Thayer HS (1981) Meaning and Action. A Critical History of Pragmatism. Hackett Publishing, Indianapolis, IN.

Torbert W (1999) The distinctive questions developmental action inquiry asks. Management Learning 30 (2), 189–206.

Trauth EM (Ed.) (2001) Qualitative Research in IS: Issues and Trends. Idea Group, Hershey, PA.

Trauth EM (Ed.) (2001b) The choice of qualitative research methods in IS. In Qualitative Research in IS: Issues and Trends. Idea Group, Hershey, PA.

Van de ven A (2007) Engaged Scholarship: A Guide for Organizational and Social Research. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Walls JG, Widmeyer GR and El Sawy OA (1992) Building an information systems design theory for vigilant EIS. Information Systems Research 3 (1), 36–59.

Walsham G (1993) Interpreting Information System in Organizations. John Wiley, Chichester.

Walsham G (1995) Interpretive case studies in IS research: nature and method. European Journal of Information Systems 4, 74–81.

Walsham G (2006) Doing interpretive research. European Journal of Information Systems 15, 320–330.

Weber M (1978) Economy and Society. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA.

Weber R (2004) The rhetoric of positivism vs. interpretivism: a personal view. MIS Quarterly 28 (1), iii–xii.

Wicks AC and Freeman RE (1998) Organization studies and the new pragmatism: positivism, anti-positivism, and the search for ethics. Organization Science 9 (2), 123–140.

Winograd T and Flores F (1986) Understanding Computers and Cognition: A New Foundation for Design. Ablex, Norwood, MA.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden

Göran Goldkuhl

Stockholm University, Kista, Sweden

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Göran Goldkuhl .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Goldkuhl, G. Pragmatism vs interpretivism in qualitative information systems research. Eur J Inf Syst 21 , 135–146 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2011.54

Download citation

Received : 31 January 2010

Revised : 22 September 2011

Accepted : 18 October 2011

Published : 20 December 2011

Issue Date : 01 March 2012

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2011.54

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- qualitative research

- interpretivism

- information systems

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

There are four categories of philosophy such as interpretivism, realism, positivism, and pragmatism. Interpretivism philosophy is generally used for understanding qualitative data whereas ...

Positivism and Interpretivism are the two basic approaches to research methods in Sociology. Positivist prefer scientific quantitative methods, while Interpretivists prefer humanistic qualitative methods. This post provides a very brief overview of the two. Positivism Interpretivism.

Interpretivism is a research paradigm in social sciences that believes reality is subjective, constructed by individuals, emphasizing understanding of social phenomena from the perspective of those involved. ... Action research, meanwhile, is a qualitative albeit positivist research design aimed at testing, rather than building theories. Action ...

Paradigm 1: Positivism. When you think positivism, think hard sciences - physics, biology, astronomy, etc. Simply put, positivism is rooted in the belief that knowledge can be obtained through objective observations and measurements.In other words, the positivist philosophy assumes that answers can be found by carefully measuring and analysing data, particularly numerical data.

Qualitative research draws from interpretivist and constructivist paradigms, seeking to deeply understand a research subject rather than predict outcomes, as in the positivist paradigm (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011).Interpretivism seeks to build knowledge from understanding individuals' unique viewpoints and the meaning attached to those viewpoints (Creswell & Poth, 2018).

positivism in a single piece of research ... interpretivism or positivism,2 methods are not inherently linked to either methodology.3 ... Institute for Qualitative and Multi-Method Research. The distinction is also made by Gerring (2012), Jackson (2006), and Sartori (1970), who wrote that methods texts have little to do with methodology, which ...

The basic differences between positivism and interpretivism are illustrated by Pizam and Mansfeld (2009) in the following manner: Assumptions: Positivism: Interpretivism: ... On the positive side, thanks to adoption of interpretivism, qualitative research areas such as cross-cultural differences in organizations, issues of ethics, leadership ...

Qualitative research is one of the most commonly used types of research and methodology in the social sciences. Unfortunately, qualitative research is commonly misunderstood. ... Depending on one's epistemological position, some scholars argue that interpretivism and positivism are complementary (Lin 1998; Sobh and Perry 2006) ...