Why Is it Important to Respect School Property?

Positive Effects of the Zero Tolerance Policy Used in Schools

Some children don’t make the connection between respect for school property and personal consequences, but the two have a strong link. The school belongs to the student as much as it belongs to the faculty. When a child disrespects her school, she is hurting herself and those around her.

Self Respect

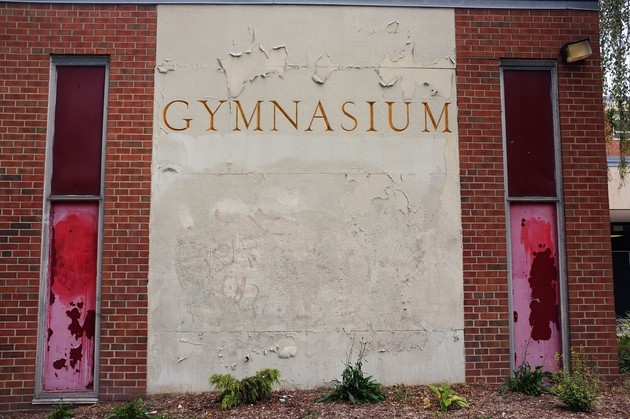

The state of the educational tools and school grounds reflect the quality of students and faculty in a school. If your school has graffiti tags and damaged books, it will show that the students of that school don’t care about their education. They are more interested in pointless acts of destruction than using the tools provided by the school to better themselves and pursue a well-rounded education.

Conserving Resources

Students may have a hard time understanding that school property doesn’t magically replenish itself. The damage a student causes may require money for repairs, something many schools have a severe lack of already. This puts the school in a tight spot and may force administrators to recycle damaged educational tools until they receive a new influx of funding. For example, if a student pulls the pages out of an education text, the next student to receive that book may have to work around the damage because the school doesn’t have an extra book for him.

When you damage school property, you run the risk of punishment. The school may report the incident to your parents, which can result in a hefty bill for damages. The instance can also go in your record, leaving a stain on your school career and credibility. While the fear of punishment may seem like a selfish reason to respect school property, it is often enough of a deterrent to help children learn respect and encourage parents to teach it.

Schools should be a comfortable safe haven for children to accrue knowledge. When a student lacks respect for school property, it can bring the quality of life in the school down. For example, leaving litter around the school grounds can make the place seem uncomfortable and cluttered. It also poses a safety threat. Other students can slip on the litter and injure themselves. Carving derogatory words and symbols into school property can also make a student who inherits use of the property uncomfortable when they discover the defacement.

Related Articles

Backpack and Locker Searches in Public High Schools

Consequences of School Violence

Can Schools Legally Take a Student's Belongings?

Pros & cons of surveillance cameras in school.

The Effects of School Uniforms on the Public School System

Ten Reasons Why Children Should Wear Uniforms

Pros & Cons of School Consolidation

Does a Public School Have Rights to Tell You What to Wear?

- University of Southern California: Lesson Plan: Respect

- EQI.org: Respect

- Discovery: Respect for Property and Authority

Shae Hazelton is a professional writer whose articles are published on various websites. Her topics of expertise include art history, auto repair, computer science, journalism, home economics, woodworking, financial management, medical pathology and creative crafts. Hazelton is working on her own novel and comic strip while she works as a part-time writer and full time Medical Coding student.

WHOSE CHILD IS THIS? EDUCATION, PROPERTY, AND BELONGING

Latoya baldwin clark*.

Previous work suggests that excludability is the main attribute of educational property and residence is the lynchpin of that exclusion. Once a child is non-excludable, the story goes, he should have complete access to the benefits of educational property. This Essay suggests a challenge to the idea that exclusion is the main attribute of educational property. By following four fictional children and their quests to own educational property in an affluent school district, this Essay argues that belonging, not exclusion, best encapsulates a child’s ability to fully benefit from a school’s educational property. Property as belonging involves a spatial relationship through which property claims are recognized and supported. In staking an unconditional claim for educational property, a child must be recognized as part of a group of entitled claimants and the property rules of the district must “hold up” that claim as legitimate. Simply because a child has a legal claim to access education does not mean that claim is equal to all other claims. Belonging helps us understand why some claims are accorded more security than others. The strength of a child’s claim to educational property depends on the extent to which the child belongs, as measured by that child’s proximity to the idealized bona fide resident.

The full text of this Essay can be found by clicking the PDF link to the left.

* Assistant Professor, University of California, Los Angeles, School of Law. Thank you to the participants of the Symposium for helpful discussion, Sunita Patel and Guy-Uriel Charles for valuable feedback, and the Columbia Law Review editors for their unending patience and support. William, Ahmir, Amina, and Ahmad: I am because you are. All mistakes are mine.

INTRODUCTION

Imagine four children all living within the boundaries of or in proximity to Hidden Heights, a predominately White, 1 1 I choose to capitalize “White” when referring to the racial group. See LaToya Baldwin Clark, Stealing Education, 68 UCLA L. Rev. 566, 568 n.1 (2021) [hereinafter Baldwin Clark, Stealing] (“I believe that capitalizing ‘Black,’ . . . without also capitalizing ‘White’ normalizes Whiteness, while the proper noun usage of the word forces an understanding of ‘White’ as a social and political construct and social identity in line with the social and political construct and social identity of ‘Black.’”). ... Close well-resourced school district sitting in a White, well-resourced municipality. 2 2 By focusing on a predominately White, well-resourced school district, I do not mean to make a normative claim that such schools are “better” than others. My claim is only that it is these school districts where claims to educational property may be most contested. ... Close Students in Hidden Heights have access to many resources that characterize educational property, including a curriculum that builds their skills, cultural resources that prepare them for middle-class and affluent social life, and resources derived from well-connected social networks. 3 3 See LaToya Baldwin Clark, Education as Property, 105 Va. L. Rev. 397, 401 (2019) [hereinafter Baldwin Clark, Property] (“Children need access to social and cultural capital, resources not easily monetized but that educational researchers have shown are integral to success in the modern workplace.” (footnotes omitted)). ... Close In this community and others like it, community members treat education as private property, a scarce resource deserving of protection like other forms of property. Because education is regarded as property, the community will encourage school officials to make it available only to those who deserve it (i.e., pay for it in property taxes and rent) and unavailable to all others without similar entitlements.

Our first child is Amanda, a White, middle-class girl who is typical of what school attendance laws consider a “bona fide resident.” 4 4 See San Antonio Indep. Sch. Dist. v. Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 1, 49 (1973) (holding that schools can restrict education to only bona fide residents). ... Close Amanda lives within the Hidden Heights boundaries with her archetypical family, including two parents, in a house they own. 5 5 Most White children live in two-parent households, compared to less than 40% of Black children. See Paul Hemez & Chanell Washington, Number of Children Living Only With Their Mothers Has Doubled in Past 50 Years, Census Bureau (Apr. 12, 2021), https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/04/number-of-children-living-only-with-their-mothers-has-doubled-in-past-50-years.html [https://perma.cc/Z572-GJNM]. Middle-class children are much more likely to live with two married parents than relatively poorer children. See Richard V. Reeves & Christopher Pulliam, Middle Class Marriage Is Declining, and Likely Deepening Inequality, Brookings Inst. (Mar. 11, 2020), https://www.brookings.edu/research/middle-class-marriage-is-declining-and-likely-deepening-inequality/ [https://perma.cc/6QT2-VZGS]. ... Close She is the prototypical student for school attendance; because she is a bona fide resident, the district cannot exclude her from its schools 6 6 See Baldwin Clark, Stealing, supra note 1, at 590 n.105 (listing state statutes from thirty-three states that require districts to prioritize residents for enrollment); id. at 570 (“Only residence within a school district’s jurisdiction confers on a parent a ‘seat license’ unavailable to nonresident parents.”). ... Close and may be obliged to protect her educational property by excluding others. 7 7 See generally Baldwin Clark, Property, supra note 3, at 410 (describing how “officials treat education as property by allowing taxpayers to lawfully exclude others, particularly through the coercive machinery of civil and criminal penalties” (emphasis omitted)). ... Close In other words, bona fide residents enjoy the right not to be excluded and the privilege of protection through the exclusion of others.

Our second child is Monica, a girl from a Black, working-class family who lives during the school week with her grandmother. 8 8 See LaToya Baldwin Clark, Family | Home | School, 117 Nw. U. L. Rev. 1, 29 (2022) [hereinafter Baldwin Clark, Family] (explaining how Black children are more likely than White children to be cared for through extended kin relationships, making it a common family form among Black families). ... Close While her grandmother is a bona fide resident within the Hidden Heights boundaries, Monica may not be, despite her presence in the district on school days. School attendance laws tend to reject living situations like Monica’s as indicative of bona fide residence, partly because most states require that a child’s address for school attendance be that of their parents or guardians, regardless of the child’s actual living situation. 9 9 Id. at 14; see also id. at 9–19 (describing “the three components of school residency laws [that determine bona fide residency]: from whom a child’s address derives, where a child can call an address a ‘home,’ and inquiries into why the caregiving adult established that address”). ... Close If she is not found to be a bona fide resident, Hidden Heights can exclude her.

Our third child is Malcolm, a Black boy from a low-income family, who lives with his parents right outside the Hidden Heights boundaries in a community not as affluent, or as White, as Hidden Heights. Unlike Amanda and (arguably) Monica, he is not a bona fide resident, and Hidden Heights has no obligation to educate him. But Hidden Heights schools are among the best, and his parents want him to attend its schools. Because they are not residents, their (legitimate) options are few. 10 10 Some parents take the step of falsifying an address to afford a nonresident child an education in a district in which a child does not live. In previous work, I referred to this as “stealing” education. See generally Baldwin Clark, Stealing, supra note 1 (describing how some nonresident children attend schools by “stealing,” or lying about their address to access school). ... Close His parents’ best option is to have Malcolm participate in an interdistrict transfer program 11 11 See Micah Ann Wixom, Educ. Comm’n of the States, Open Enrollment 1 (2019), https://www.ecs.org/wp-content/uploads/Open-Enrollment.pdf [https://perma.cc/9EXD-L2M3] (describing differences in open enrollment statutes for various states). ... Close that breaks the tight connection between school attendance and residence. Available in most states, these programs allow students who do not live inside a district’s boundaries to attend that school district’s schools. 12 12 Id. ... Close But his continued attendance is conditional and relies on considerations not applicable to resident students including academic and behavioral standards. Unlike bona fide resident children, Malcolm does not enjoy the unconditional right not to be excluded.

Our fourth child is Kyle, a middle-class Black boy with a disability who is a Hidden Heights bona fide resident. Like Amanda, his claim should be the most secure, and in some ways, it is. Before the mid-1970s, Kyle may not have had a right to attend school, even as a bona fide resident. 13 13 See, e.g., Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (“IDEA”), 20 U.S.C. § 1400(c)(2) (2018) (explaining how prior to 1975, many children with disabilities were “excluded entirely from the public school system”). ... Close Today, federal law requires public schools to educate and accommodate children with disabilities. 14 14 Id. § 1412(a)(1) (requiring school districts to provide every child with a disability a free appropriate public education). ... Close But like many children with disabilities deemed incompatible with the general education classroom, Kyle spends much of his day in a segregated classroom, away from children who do not live with a disability. 15 15 Approximately one-third of students with disabilities spend less than 80% of their school day in a general education classroom. Specifically, [a]mong all school-age students served under IDEA, the percentage who spent 80 percent or more of their time in general classes in regular schools increased from 59 percent in fall 2009 to 66 percent in fall 2020. In contrast, during the same period, the percentage of students who spent 40 to 79 percent of the school day in general classes decreased from 21 to 17 percent, and the percentage of students who spent less than 40 percent of their time in general classes decreased from 15 to 13 percent. Nat’l Ctr. for Educ. Stat., Students with Disabilities, The Condition of Education 2022, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cgg [https://perma.cc/56UA-C55U] (last updated May 2022). ... Close Although every child with a disability is entitled to a free appropriate public education in the district in which they reside, the setting of that education need not be in the general education classroom, but only in the “least restrictive environment.” 16 16 IDEA’s LRE mandate requires that schools, [t]o the maximum extent appropriate, [ensure that] children with disabilities, including children in public or private institutions or other care facilities, are educated with children who are not disabled, and special classes, separate schooling, or other removal of children with disabilities from the regular educational environment occurs only when the nature or severity of the disability of a child is such that education in regular classes with the use of supplementary aids and services cannot be achieved satisfactorily. 20 U.S.C. § 1412(5)(A). ... Close As a result, he has little access to the general education curriculum and social experiences with general education students. Amanda, Monica, Malcolm, and Kyle all have claims to enjoy the Hidden Heights educational property. Still, the bases for their claims, the possibility of success when those claims are challenged, and the overall security of their claims differ.

Amanda’s claim to education is one of unconditional ownership, access, and benefits available to her if she remains a bona fide resident. Monica’s claim to the educational property is more tenuous than Amanda’s, even though she lives in the same area during the days she attends school. Because Monica does not live within the district’s boundaries 24/7, her family must jump through evidentiary hoops Amanda’s family avoids, proving that Hidden Heights is her true “home” to continue to attend school. 17 17 See infra Part I. ... Close

While Malcolm has access to the educational property when he receives permission to attend, his continued access as a nonresident is contingent; Hidden Heights decides the conditions under which it accepts nonresident students and can condition continuing attendance on academics and discipline. 18 18 See infra Part II (explaining how many districts impose academic and behavioral requirements on nonresident students as a condition of continued attendance). ... Close

Lastly, Kyle should be most secure in non-excludability, as both a bona fide resident and a child with a disability who has a statutory right to be educated in the district in which he resides. But his access to the educational property, the resources contained in the school’s walls, is limited; schools may use his disability label as a justification for his segregation, especially because he is a Black boy. 19 19 See infra Part II. ... Close

These children’s experiences, where they all have a legal claim to the educational property amassed in this district, complicate the story about education, property, and access. Legal entitlement or permission to attend school does not mean that one can fully benefit from a district’s educational property. This Essay suggests that the differences in these children’s claims to Hidden Heights educational property are not only about who cannot be excluded and who must be included. Instead, the children’s stories illustrate relational positions in the space of the Hidden Heights school district and the extent to which law, policies, and practices support their claims. The students’ access to educational property rises and falls on whether they “belong.”

A focus on belonging encourages us to see property claims as relational and spatial. 20 20 See infra Part III. ... Close Instead of focusing on the Subject and Object of property (“who” owns “what”), belonging attends to the Space in which property claims are asserted and the organizational and structural practices that support and legitimate, or undermine and delegitimate, those claims. Accessing educational property is not solely about the individual attributes of students making a claim, but also about the law, policies, and practices that define the space and render determinations about whose claims are legitimate—thus deserving of protection—and whose claims are not.

The degree of a child’s belonging depends not only on the legal right to ownership or access but also on the social processes, structures, and networks that support those claims. We can harmonize Amanda’s, Monica’s, Malcolm’s, and Kyle’s seemingly divergent experiences by considering the extent to which the children belong.

Of course, residence plays an essential role in school attendance and access to educational property. Bona fide resident children are the privileged class with the most substantial claim not to be excluded. As argued below, Amanda is the ideal against which all the other children are judged.

This Essay proceeds as follows: Part I describes the conventional test for who gets to access a district’s educational property. That test rises and falls on residency; thus, this Part focuses on Amanda’s and Monica’s disparate experiences in establishing bona fide residency, relating to family form and living arrangements. Part II describes circumstances in which nonresidents like Malcolm and bona fide resident children with disabilities like Kyle overcome exclusion to develop an inclusive right to educational property. Yet they experience that access very differently from prototypical Amanda.

Finally, Part III suggests how focusing on property as belonging complicates the story of education as property with the central characteristic of exclusion. To belong, the students need to show that not only do they (1) have a legal claim but also that (2) they are genuine members of the group that deserves the property and (3) the law, policies, and practices of the space support those claims. To conclude, this Essay suggests that thinking about access to educational property through the lens of belonging is particularly salient in the school context, in which belonging has long been considered critical to student academic and social success.

Schoolhouse Property

abstract . The Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments prohibit government actors from interfering with an individual’s property without due process of law. Property interests protected by the Due Process Clause are created by subconstitutional sources of law, such as federal, state, or local statutes or regulations, that create reasonable expectations of an entitlement, such as welfare benefits, in recipients. Individuals holding legitimate claims of entitlement to property are typically afforded procedural protections. In the landmark 1975 decision Goss v. Lopez , the Supreme Court determined that state laws entitling children to free public education conferred on public primary- and secondary-school students a property interest in education. To avoid unjust deprivation of students’ property interests, the Court held that the Due Process Clause requires school officials to provide students subject to suspension or expulsion with, at minimum, informal notice and opportunity to be heard by the school disciplinarian—a requirement that, in practice, affords students little protection against unjust exclusion. Since 1975, however, students’ constitutionally protected property interests have expanded beyond just education. Comprehensive fifty-state surveys of state laws and regulations reveal that the majority of states require schools to provide additional benefits to students, specifically government-subsidized meals and health services. This Note evaluates these entitlements and argues that they constitute property interests falling within the ambit of the Due Process Clause. As a result, students subject to exclusionary discipline are deprived not only of education, as the Goss Court foresaw, but also meals and health services. These additional property interests may require reevaluation and expansion of the minimum procedural requirements that schools must afford students subject to suspension or expulsion.

author. J.D. 2021, Yale Law School; B.S. Hon. 2017, Cornell University. Thank you to Professor Claire Priest for her invaluable support and guidance from this project’s inception. I am also deeply indebted to Professor Jason Parkin, Professor Nicholas Parrillo, Professor Andrew Hammond, Timur Akman-Duffy, Hirsa Amin, Joseph Daval, and David Herman for their perceptive feedback. Finally, I am grateful to the editors of the Yale Law Journal , particularly Kate Hamilton and Max Jesse Goldberg, for their insightful suggestions, assistance, and endless patience. All errors are my own.

This Note features three appendices regarding public primary- and secondary-school students’ rights to education granted by state constitutions and corollary entitlements to school meals and school health services granted by state laws and regulations. Each of these appendices are published online following the Note.

Introduction

The Due Process Clause forbids government actors, including public-school officials, 1 from interfering with an individual’s “life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” 2 The Clause protects some of the interests most vital to American democracy. The Supreme Court has understood the principal value of the Clause as promoting accurate decision making, 3 thus restraining arbitrary government action. 4 Procedural protections — often in the form of notice and opportunity to be heard before a government decision maker—function, in addition to facilitating accuracy of the substantive decision, 5 to promote participatory and dignitary values 6 and advance fundamental fairness. 7

The precise scope of the “property” interests protected by the Due Process Clause, and the process that must precede its deprivation, has provoked significant debate since the middle of the twentieth century. 8 In the 1970 decision Goldberg v. Kelly , the Supreme Court expanded the scope of constitutionally protected property to statutory entitlements, specifically welfare benefits. 9 By broadening the forms of property receiving constitutional protection, Goldberg initiated the “due process revolution,” 10 resulting in a series of Supreme Court decisions finding that public employment, 11 immigration status, 12 and, most importantly for this Note, public primary- and secondary-school education 13 are property under the Due Process Clause, 14 requiring the government to afford property-holders some kind of process. 15

Courts assess procedural due-process claims implicating property interests in two steps. The first step asks whether there exists a property interest protected by the Due Process Clause. 16 “To have a property interest in a benefit,” a person must “have a legitimate claim of entitlement to it.” 17 Legitimate claims of entitlement, in turn, arise from subconstitutional sources of positive law—such as federal, state, or local law or regulation, or express or implied government contracts—that create reasonable expectations of specific benefits. 18

If a court finds a protected property interest beyond a de minimis level, 19 it moves on to the second step, which asks what, if any, process is due. 20 In answering this question, courts focus on identifying the specific procedures that will promote accuracy in the substantive decision. 21 While the Supreme Court has explained that when state action implicates one’s property interests the Due Process Clause requires, at minimum, notice and a meaningful opportunity to be heard, 22 the “precise contours” of the procedures required by the Constitution are determined by the factual circumstances presented by each case . 23 Courts balance three interests: (1) the private property interest affected by the government’s action; (2) the risk of erroneous deprivation through the procedures used and the probable value of additional procedures; and (3) the financial and administrative burdens that additional procedures would impose on the government. 24 The private interest weighs heavily in this analysis: the formality of the process required corresponds to the court’s perception of the significance of the implicated property interest. 25 The more consequential the property interest, the more likely courts are to mandate more formal, trial-like procedures. Thus, due-process analysis, in both steps, “is sensitive to the facts and circumstances” that a specific deprivation presents. 26 At the first step, changes in substantive law may affect the existence or scope of a property interest, as well as the perceived import of the interest. At the second step, changed circumstances may affect how courts weigh the property interest against competing interests to establish the specific process due.

In Goss v. Lopez in 1975, the Supreme Court followed these two steps in determining whether students hold due-process rights to challenge their exclusion from school via short suspensions of ten days or less. 27 The Court first found that state laws guaranteeing resident children a free public education and compelling school attendance vested in students a constitutionally protected property interest in public education. 28 In other words, when school officials exclude students from the school setting even temporarily through suspensions, they deprive students of an important interest protected by the Due Process Clause. 29 The Court then, at the second step, considered which specific procedures were due to ensure that a school official’s decision to suspend a student was based on accurate findings of misconduct. 30 After weighing the interests of the student in avoiding unjust exclusion from school against the state interest in maintaining order in schools and conserving resources, the Court determined that schools owe students only informal, “rudimentary” procedures. 31 Specifically, school officials must give a student facing suspension “notice of the charges against him and, if he denies them, an explanation of the evidence the authorities have and an opportunity to present his side of the story.” 32 The Court specified that an informal conversation between student and disciplinarian moments after the alleged misconduct occurs will typically satisfy this notice-and-hearing requirement. 33

Goss ’s threshold determination—that public-school students hold a property interest in their educations—remains significant. 34 But the specific process it prescribed to protect that interest has done little in practice to shield students from unjust exclusion from schools. 35 Many commentators, addressing only the second step of the due-process inquiry, have called for additional procedures that might better protect students from unjust exclusion from school, such as mediation or representation at hearings. 36 Fewer, however, have suggested raising the procedural floor by reexamining the legal source of the property interest at stake at the first step. This Note provides such an approach by explaining how the procedural minimum for exclusionary discipline can be reevaluated upon a finding, at the first step of the due-process inquiry, that the state has conferred additional entitlements to students. 37

Unlike many other constitutional guarantees, an individual’s procedural rights are not fixed in time 38 —they evolve with both substantive developments in the law and evolving societal standards for “fairness.” 39 Indeed, the Court has repeated the maxim that “due process is flexible and calls for such procedural protections as the particular situation demands.” 40 The minimal procedures that Goss prescribed may have satisfied the constitutional requirements of the Due Process Clause in 1975. As both the legal landscape of entitlements and societal circumstances have evolved, however, those procedures may now be insufficient. 41

This Note argues that as the state has conferred additional entitlements on public primary- and secondary-school students in the form of school meals and health services, students’ property interests in avoiding unjust exclusion from school has correspondingly broadened. Given this expansion, the due-process protections owed to students subject to removal from school must be reevaluated. Since Goss was decided in 1975, both federal and state law have conferred additional entitlements— “legally enforceable individual right[s]”—upon students. 42 Federal nutrition-assistance programs have expanded to fund and administer a wide array of school-meal programs for all children. 43 Most importantly, fifty-state surveys reveal that states often require schools to participate in these federal-meal programs or a state equivalent. 44 Similarly, the great majority of states now require schools to provide health services of some kind to students. 45 Many states go so far as to require preventive healthcare to students at no cost to all parents, or, in some states, at no cost to indigent parents. 46

On the whole, since 1975, the school has become more than the child’s source of academic instruction and socialization—it has become a supplier of nutritional meals and a provider of health services. 47 Accordingly, the deprivation suffered by children excluded from school, for any period of time, has increased beyond what the Goss Court anticipated. 48 As students’ interests in avoiding unjust removal from the school setting evolve, so too should the protections they receive in the course of exclusion. 49

This Note proceeds in four parts. Part I outlines how the creation and growth of the welfare and administrative states in the twentieth century prompted a shift in procedural due-process jurisprudence. Through the 1960s and 1970s, the Supreme Court broadened its understanding of the types of “property” protected by the Due Process Clause, which in turn facilitated the extension of procedural rights to additional classes of individuals, including students in Goss v. Lopez .

Part II examines Goss and its consequences in greater depth, focusing on Goss ’s threshold finding that students have a protected property interest in their educations. Under the Court’s flexible conception of due process, that key determination serves as the basis for judicial “reevaluation” of the minimum process required by the Due Process Clause as students’ entitlements expand. 50

Part III identifies the functions of the school that have undergone significant growth, in both nature and scope, since Goss was decided. Fifty-state surveys of laws and regulations reflect paradigm shifts in the school’s role in society—it is now the centerpiece of child-welfare programs. Federal nutritional programs have expanded massively since Goss , and most states have enacted laws or promulgated regulations mandating schools to participate in the federal-meal programs and provide children with government-subsidized meals. Moreover, the laws and regulations of many states now also require the provision of formal school health services to students. 51 Such programs, guaranteed to at least some students by statute or regulation, create reasonable expectations of entitlements in public-school students that constitute property interests. 52 These additional property interests affect students’ interest in avoiding unjust removal from the school environment, and necessitate a reevaluation of whether the procedural safeguards demanded by the Due Process Clause in 1975 continue to satisfy due process today. 53

In light of Part III’s analysis of the additional statutory and regulatory entitlements to students that properly constitute property interests falling within the ambit of the Clause, Part IV provides preliminary thoughts on additional procedures, beyond the informal notice-and-hearing requirement from Goss , that students should be afforded when facing exclusionary discipline, subject to the duration of the exclusion, variations in state entitlement schemes, and the scope of benefits to which the specific student is entitled.

Volume 133’s Emerging Scholar of the Year: Robyn Powell

Announcing the eighth annual student essay competition, announcing the ylj academic summer grants program.

See W. Va. State Bd. of Educ. v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624, 637-38 (1943) (clarifying that public-school officials, as government actors, are subject to constitutional limits on government action).

U.S. Const. amends. V, XIV. The Supreme Court has read the cryptic language of the Due Process Clause as imposing both substantive and procedural limitations on government action. See Ryan C. Williams, The One and Only Substantive Due Process Clause , 120 Yale L.J. 408, 417-18 (2010). This Note focuses on the latter.

Robert L. Rabin, Job Security and Due Process: Monitoring Administrative Discretion Through a Reasons Requirement , 44 U. Chi. L. Rev. 60, 76 (1976) (observing that the “[u]nderlying . . . conception” of the Court’s early 1970s due-process jurisprudence “is the vital interest in promoting an accurate decision, in assuring that facts have been correctly established and properly characterized in conformity with the applicable legal standard”).

See Murray’s Lessee v. Hoboken Land & Improvement Co., 59 U.S. (18 How.) 272, 276 (1856).

See, e.g. , Martin H. Redish & Lawrence C. Marshall, Adjudicatory Independence and the Values of Procedural Due Process , 95 Yale L.J. 455, 476 (1986).

See, e.g. , Jerry L. Mashaw, Administrative Due Process: The Quest for a Dignitary Theory , 61 B.U. L. Rev. 885, 902-03 (1981) (highlighting participation in hearings as a “dignitary process value[]”); David L. Kirp, Proceduralism and Bureaucracy: Due Process in the School Setting , 28 Stan. L. Rev. 841, 845-49 (1976) (describing how hearings both facilitate accuracy in substantive outcomes and reduce the possibility of biased decision-making).

See, e.g. , Sanford H. Kadish, Methodology and Criteria in Due Process Adjudication—A Survey and Criticism , 66 Yale L.J. 319, 346 (1957) (explaining that one of the “objectives” of due process, to “insur[e] the reliability of the [adjudicatory] process,” is “often expressed in terms of ‘fairness’”).

See Cynthia R. Farina, On Misusing “Revolution” and “Reform”: Procedural Due Process and the New Welfare Act , 50 Admin. L. Rev. 591, 591-99 (1998) (summarizing “the debate about the direction of procedural due process”).

Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S. 254, 262 (1970).

Richard J. Pierce, Jr., The Due Process Counterrevolution of the 1990s? , 96 Colum. L. Rev. 1973, 1974 (1996) (noting that until Goldberg , property rights “were defined narrowly” by the Supreme Court “to include only forms of property that are usually the fruits of an individual’s labor, such as money, a house, or a license to practice law”).

See, e.g. , Cleveland Bd. of Educ. v. Loudermill, 470 U.S. 532, 538, 542-43 (1985) (establishing that government employees, including, in this case, public-school security guards, are entitled to due process before termination on the grounds that state law granted public employees a property interest in their employment).

See, e.g. , Landon v. Plasencia, 459 U.S. 21, 34-35 (1982) (finding that lawful permanent residents are entitled to procedural protections under the Due Process Clause).

Goss v. Lopez, 419 U.S. 565, 573-76 (1975).

See, e.g. , Logan v. Zimmerman Brush Co., 455 U.S. 422, 430 (1982) (“[T]he types of interests protected as ‘property’ are varied and, as often as not, intangible, relating ‘to the whole domain of social and economic fact.’” (quoting Nat’l Mut. Ins. Co. v. Tidewater Transfer Co., 337 U.S. 582, 646 (1949) (Frankfurter, J., dissenting))).

Loudermill , 470 U.S. at 541 (“The right to due process ‘is conferred, not by legislative grace, but by constitutional guarantee. While the legislature may elect not to confer a property interest . . . it may not constitutionally authorize the deprivation of such an interest, once conferred, without appropriate procedural safeguards.’” (quoting Arnett v. Kennedy, 416 U.S. 134, 167 (1974) (Powell, J., concurring in part and concurring in result in part))).

Ky. Dep’t of Corrs. v. Thompson, 490 U.S. 454, 460 (1989). In other words, before determining what specific procedures are due, a court must make a threshold determination that an interest protected by the Due Process Clause is, in fact, implicated.

Bd. of Regents of State Colls. v. Roth, 408 U.S. 565, 577 (1972).

Id. at 576-77 ; see Rodney A. Smolla, The Reemergence of the Right/ P rivilege Distinction in Constitutional Law: The Price of Protesting Too Much , 35 Stan. L. Rev. 69, 72-73 (1982).

See Ingraham v. Wright, 430 U.S. 651, 674 (1977) (“There is, of course, a de minimis level of imposition with which the Constitution is not concerned.”).

Thompson , 490 U.S. at 460. A court may determine that a constitutionally protected interest is implicated at the first step of the due-process inquiry but nevertheless not require any process at the second step if the burdens the procedure would impose on the government outweigh the value of any “additional [procedural] safeguard[s].” See, e.g. , Ingraham , 430 U.S. at 682 (quoting Mathews v. Eldridge, 424 U.S. 319, 348 (1976)).

Rabin, supra note 3, at 76.

Cleveland Bd. of Educ. v. Loudermill, 470 U.S. 532, 542 (1985) (“An essential principle of due process is that a deprivation of life, liberty, or property ‘be preceded by notice and opportunity for hearing appropriate to the nature of the case.’” (quoting Mullane v. Cent. Hanover Bank & Tr. Co., 339 U.S. 306, 313 (1950))); Grannis v. Ordean, 234 U.S. 385, 394 (1914) (“The fundamental requisite of due process of law is the opportunity to be heard.”); Armstrong v. Manzo, 380 U.S. 545, 552 (1965) (stating that the opportunity to be heard “must be granted at a meaningful time and in a meaningful manner”); see also Larry Bartlett & James McCullagh, Exclusion from the Educational Process in the Public Schools: What Process Is Now Due , 1993 BYU Educ. & L.J. 1, 8-9 (explaining that, though the exact procedures required by the Due Process Clause depend in part on the nature of the deprivation, courts have recognized that due process requires notice and an opportunity to be heard).

Jason Parkin, Due Process Disaggregation , 90 Notre Dame L. Rev. 283, 301-02 (2014); see, e.g. , Hannah v. Larche, 363 U.S. 420, 442 (1960) (explaining that the specific procedure required “varies according to specific factual contexts”); Boddie v. Connecticut, 401 U.S. 371, 378 (1971) (“The formality and procedural requisites for the hearing can vary, depending upon the importance of the interests involved . . . .”).

Mathews , 424 U.S. at 334-35.

Frank H. Easterbrook, Substance and Due Process , 1982 Sup. Ct. Rev. 85, 89.

Jason Parkin, Dialogic Due Process , 167 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1115, 1119, 1127-28 (2019); see also Cafeteria & Rest. Workers Union, Local 473 v. McElroy, 367 U.S. 886, 895 (1961) (“The very nature of due process negates any concept of inflexible procedures universally applicable to every imaginable situation.”).

419 U.S. 565 (1975). Goss remains the only case that the Supreme Court has decided with respect to public-school students’ procedural rights when facing exclusionary discipline and is expressly limited “to the short suspension, not exceeding 10 days.” See id. at 584.

Id. at 572-74.

Id. at 576. Suspensions of ten days were deemed not de minimis. Id. The Court did not address the precise procedure constitutionally demanded for suspensions exceeding ten days or expulsions, instead merely noting that longer exclusions from the school setting “may require more formal procedures.” Id. at 584.

Id. at 577-78, 581.

Id. at 581.

Id. at 582; see Justin Driver, The Schoolhouse Gate: Public Education, the Supreme Court, and the Battle for the American Mind 144-45 (2018) (discussing the minimal procedural requirements imposed by Goss v. Lopez ).

See infra Section II.B.2.

See, e.g. , Nadine Strossen, Protecting Student Rights Promotes Educational Opportunity: A Response to Judge Wilkinson , 1 Mich. L. & Pol’y Rev. 315, 316-18 (1996).

See, e.g. , John M. Malutinok, Beyond Actual Bias: A Fuller Approach to an Impartiality in School Exclusion Cases , 38 Child.’s Legal Rts. J. 112, 138-42 (2018) (proposing the addition of a requirement of impartial adjudication); Simone Marie Freeman, Note, Upholding Students’ Due Process Rights: Why Students Are in Need of Better Representation at, and Alternatives to, School Suspension Hearings , 45 Fam. Ct. Rev. 638, 644-46 (2007) (proposing representation at exclusionary hearings); James W. McMasters, Comment, Mediation: New Process for High School Disciplinary Expulsions , 84 Nw. U. L. Rev. 736, 737-38, 764-70 (1990) (proposing student-teacher mediation).

See Parkin, supra note 26, at 1119 (emphasizing that the specific procedure that satisfies the Due Process Clause is “amenable to reevaluation and revision”).

Cafeteria & Rest. Workers Union, Local 473 v. McElroy, 367 U.S. 886, 895 (1961) (“‘[D]ue process,’ unlike some legal rules, is not a technical conception with a fixed content unrelated to time, place and circumstances.” (quoting Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Comm. v. McGrath, 341 U.S. 123, 162 (1951) (Frankfurter, J., concurring))).

Parkin, supra note 23, at 322; see Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12, 20-21 (1956) (Frankfurter, J., concurring) (“‘Due process’ is, perhaps, the least frozen concept of our law—the least confined to history and the most absorptive of powerful social standards of a progressive society.”).

Morrissey v. Brewer, 408 U.S. 471, 481 (1972); see also Wilkinson v. Austin, 545 U.S. 209, 224 (2005) (observing that the Court has “declined to establish rigid rules” to govern the due-process inquiry); Hannah v. Larche, 363 U.S. 420, 442 (1960) (“‘Due process’ is an elusive concept. Its exact boundaries are undefinable, and its content varies according to specific factual contexts.”).

Cf. Jason Parkin, Adaptable Due Process , 160 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1309, 1311, 1314-17 (2012) (summarizing how changes in the administration of public benefits may have changed the specific procedures necessary to comport with the dictates of the Due Process Clause).

See David A. Super, The Political Economy of Entitlement , 104 Colum. L. Rev. 633, 648 (2004). David A. Super helpfully delineates six different types of entitlements: subjective, unconditional, positive, budgetary, responsive, and functional. See id. at 644-58. This Note, when referring to entitlements, employs Super’s definition of “positive entitlement,” one that confers “a legally enforceable individual right,” id. at 648, since that is the definition that courts use to determine whether a benefit constitutes a property interest protected by the Due Process Clause, id. at 648-50.

See Richard B. Russell National School Lunch Act, ch. 281, §§ 2-11, 60 Stat. 230, 230-34 (1946) (codified at 42 U.S.C. §§ 1751-1759 (2018)); see also infra Section III.A. Super observes that federal provisions concerning school lunches and breakfasts meet the criteria for budgetary, responsive, and functional entitlements, and arguably meet the criteria for unconditional entitlements, in addition to the positive-entitlement definition used in this Note. Super, supra note 42, at 728. In effect, then, regardless of one’s definition of “entitlement,” school-meal services meet it.

This Note features three online appendices. Appendix A displays relevant constitutional provisions from all fifty states concerning the right to education. Appendix B provides, where applicable, states’ laws and regulations pertaining to school meals. And Appendix C provides, where applicable, states’ laws and regulations pertaining to school healthcare. In each of the appendices, I exclude (1) state provisions that relate to measures related only during the COVID-19 public health emergency; and (2) state provisions regarding public charter schools and private schools. Each appendix is current as of March 1, 2022.

See infra Appendix C; Section III.B.

See infra Appendix C.

See infra Part III; Appendices B & C.

See Patricia Wald, Goss v. Lopez : Not the Devil; Nor the Panacea , 1 Mich. L. & Pol’y Rev. 331, 333 (1996).

Cf. Parkin, supra note 41, at 1317 (“By undermining many of the factual assumptions that originally justified the right to a fair hearing, these changes in the facts and circumstances of welfare programs and welfare recipients have increased the risk that benefits will be erroneously terminated.”).

Parkin, supra note 26, at 1152-53 (explaining that the Supreme Court’s due-process jurisprudence “open[s] the door to reevaluation of procedural due process precedents when changes in the underlying facts and circumstances bear upon the factors that courts must consider when evaluating challenges to existing procedures”).

See infra Appendices B & C. Inspiration for looking to applicable state laws and regulations to see change over time is drawn from James Bryce, who commented in 1888 that “he who would understand the changes [in] the American democracy will find far more instruction in a study of the state governments than of the federal Constitution.” 1 James Bryce, The American Commonwealth 366 (Indianapolis, Liberty Fund, Inc. 1995) (1888). Moreover, localities, via school district boards of education, can and have mandated additional nutritional and health programs. See Timothy D. Lytton, An Educational Approach to School Food: Using Nutrition Standards to Promote Healthy Dietary Habits , 2010 Utah L. Rev. 1189, 1190. I omit analysis of local regulations for the sake of brevity. See infra note 276.

See Bd. of Regents of State Colls. v. Roth, 408 U.S. 564, 577 (1972) (holding that constitutionally protected property interests are not created by the Constitution but “stem from an independent source such as state law”).

See Parkin, supra note 41, at 1362-65 (arguing that amending the procedures demanded by the Due Process Clause to account for “changing facts and circumstances is faithful to the Court’s” understanding of due process).

- 0 Shopping Cart $ 0.00 -->

🎉 JD Advising’s Biggest Sale is Live! Get 20% off our top bar exam products, including our must-have one-sheets – Shop Now 🎉

With the bar exam fast approaching, our FREE MEE Highly Tested Topics guide and our FREE July 2024 UBE Study Guide can help you use your remaining study time wisely!

Taking the MPRE in August? Enroll in our FREE MPRE Course to access our outline, one-sheet, lecture videos, 300+ practice questions, and more! If you’re looking for more help, consider purchasing released MPRE questions or MPRE tutoring !

Real Property on the Multistate Essay Exam: Highly Tested Topics and Tips

Real Property is regularly tested on the MEE. Here, we give you tips for approaching Real Property on the MEE and we reveal some of the highly tested issues in Real Property MEE questions.

Real Property on the Multistate Essay Exam

1. first, be aware of how real property is tested.

Real Property is tested, on average, about once a year. Real Property is generally tested on its own and not combined with another subject.

Real Property can be a challenging subject for many students. To prepare for Real Property on the MEE, it is best to begin by focusing on the highly tested issues. Also make sure to understand key Real Property vocabulary, as we discuss below.

2. Be aware of the highly tested Real Property issues

The examiners tend to test several of the same issues in Real Property MEE questions. You can maximize your score by being aware of these highly tested issues. (We have a nice summary of these in our MEE One-Sheets if you want to see all of them and have them all in one place.)

Some of the highly tested Real Property Multistate Essay Exam issues include:

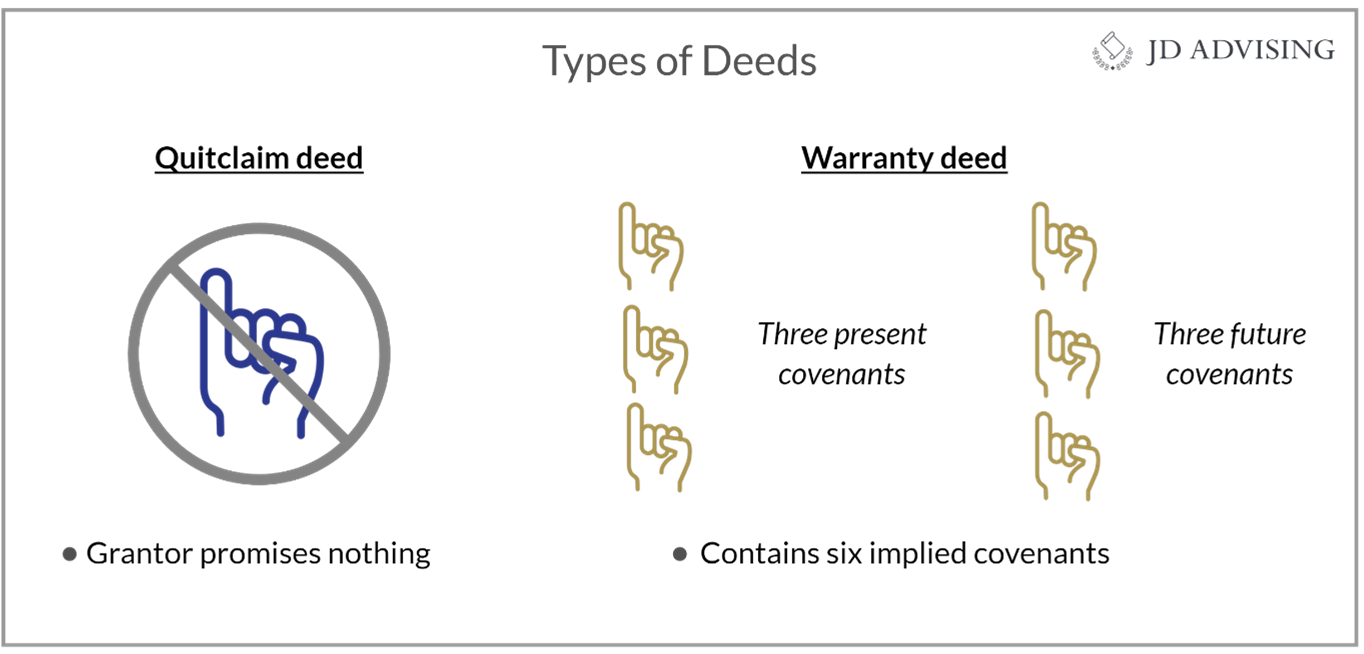

Deeds are frequently tested when Real Property is tested on the MEE. Remember that there are two different types of deeds: general warranty deeds and quitclaim deeds.

- With a quitclaim deed , the grantee receives whatever interest the grantor has in the property. There are no warranties.

- A general warranty deed has six covenants: right to convey , seisen , no encumbrances , further assurances , quiet enjoyment , and warranty .

Recording acts

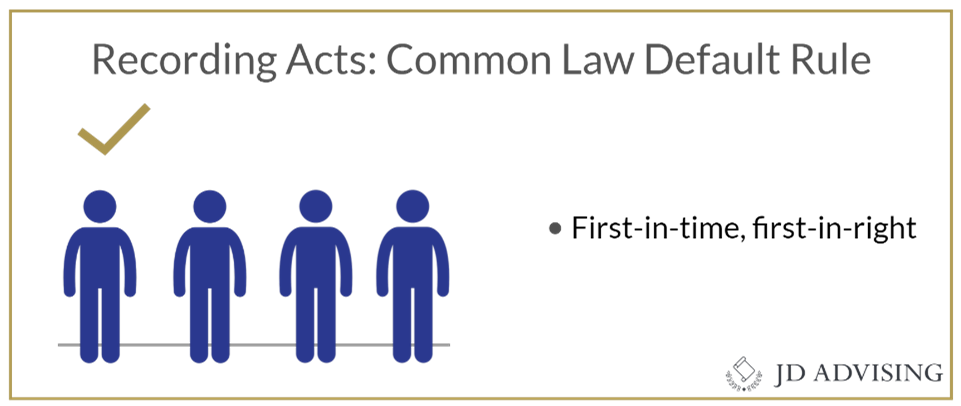

If you see a recording act issue tested, you should start your answer by discussing the common law default rule of first-in-time first-in-right .

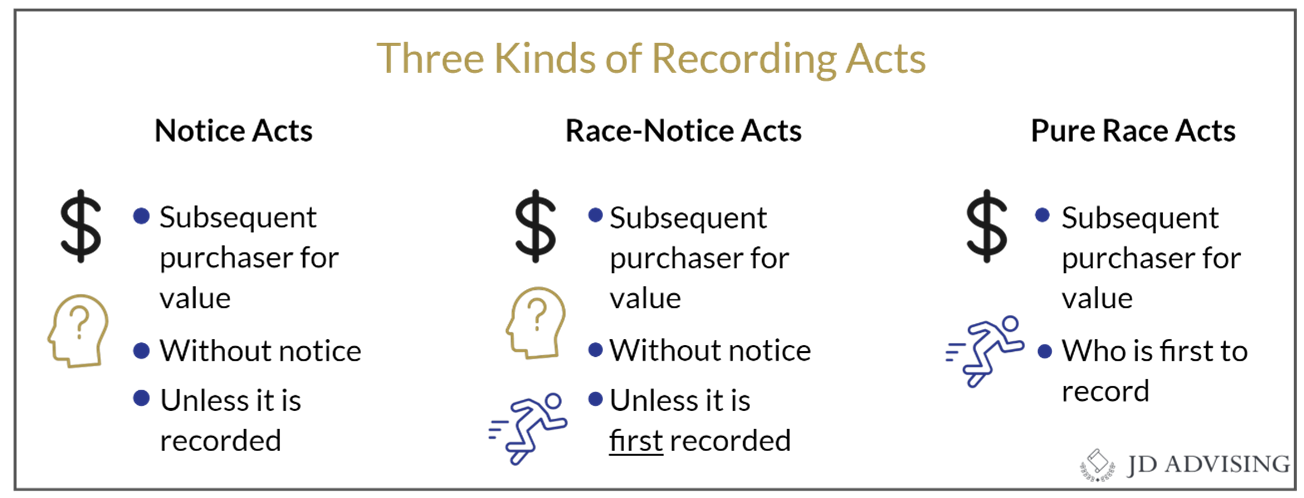

Remember that a grantor can only convey the rights the grantor has at the time of conveyance. Many states have implemented recording acts that change the common law result. There are three different types of recording acts :

- Notice acts: The language of a notice recording act will be something like, “A conveyance of interest in land is not valid against any subsequent purchaser for value without notice unless it is recorded .” This act has the word “recorded” but says nothing about recording first .

- Race-notice acts: The language of a race-notice act will be something like, “No conveyance of an interest in land is valid against any subsequent purchaser for value without notice unless it is recorded first . ” This act mentions both notice and “recording first, which is your cue it is a race-notice act!

- Pure race acts: Pure race acts protect a subsequent purchaser who records first. These are rare and are virtually never tested!

Landlord-tenant law

Landlord-tenant law turns up frequently in Real Property on the MEE. Be aware of the following points:

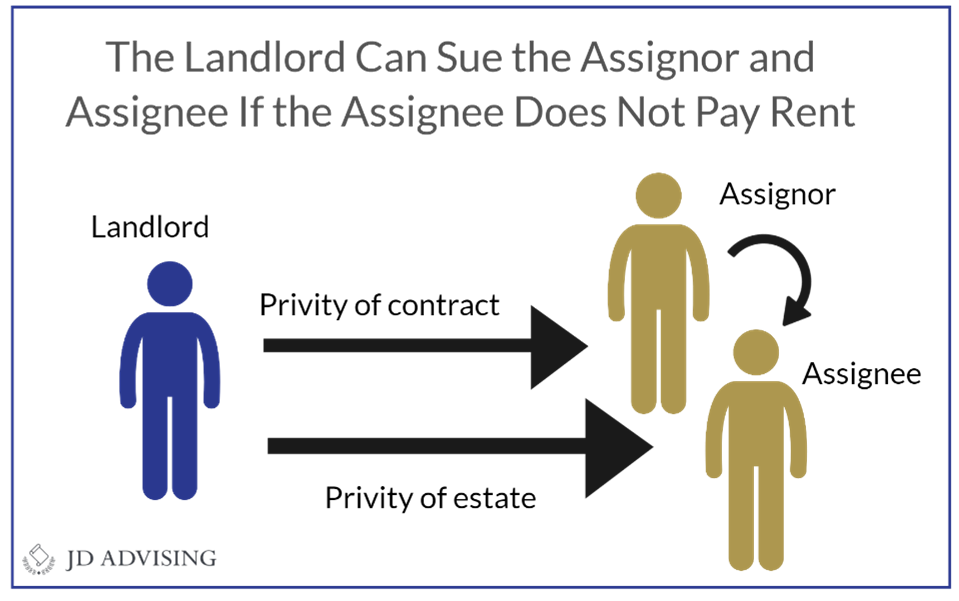

- Assignment of a lease or subleasing is permitted as long as there is no language in the original lease prohibiting it.

- The tenant has specific duties , including the duty to pay rent . If the tenant does not pay rent but has abandoned the property, the landlord can sue the tenant for damages or treat it as a surrender . Under the common law, the landlord has no duty to mitigate damages. However, many states have instituted their own laws requiring landlords to make a reasonable attempt to mitigate damages.

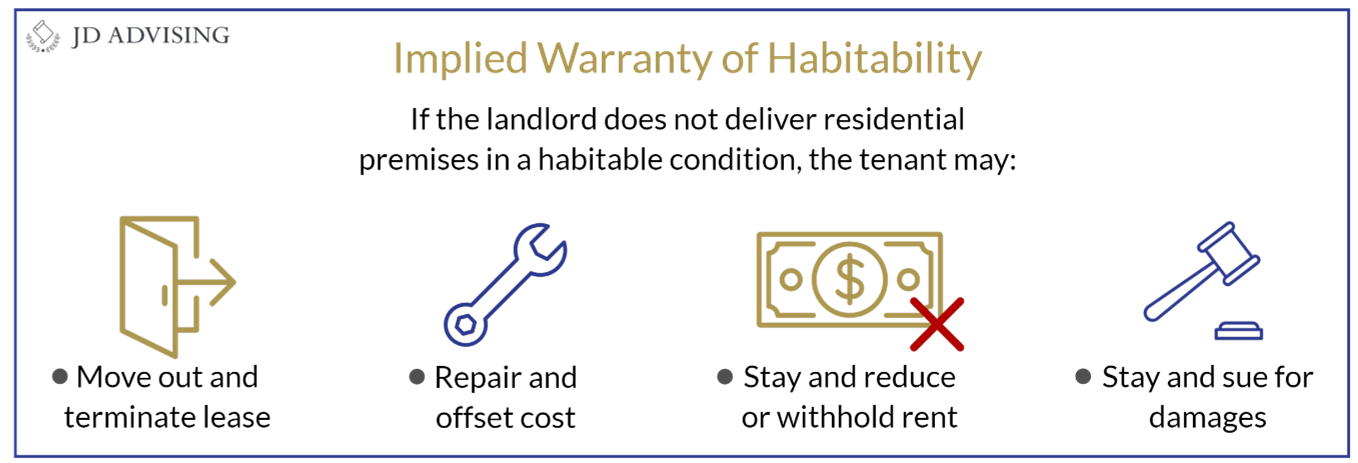

- The landlord also has specific duties , including the implied warranty of habitability —which requires the landlord to deliver residential premises in habitable condition —and the covenant of quiet enjoyment —which prohibits the landlord from interrupting the tenant’s enjoyment of the premises or making the premises unsuitable .

3. Learn Real Property vocabulary

Not only is it important to understand and be able to define key terms, but it is also a good idea to bold and underline Real Property buzzwords on your MEE answers. By doing so, you will draw the grader’s attention to them and maximize your potential points.

Here are a few Real Property terms you should be aware of:

- Warranty deed: contains six warranties (or covenants).

- Quitclaim deed: contains no covenants.

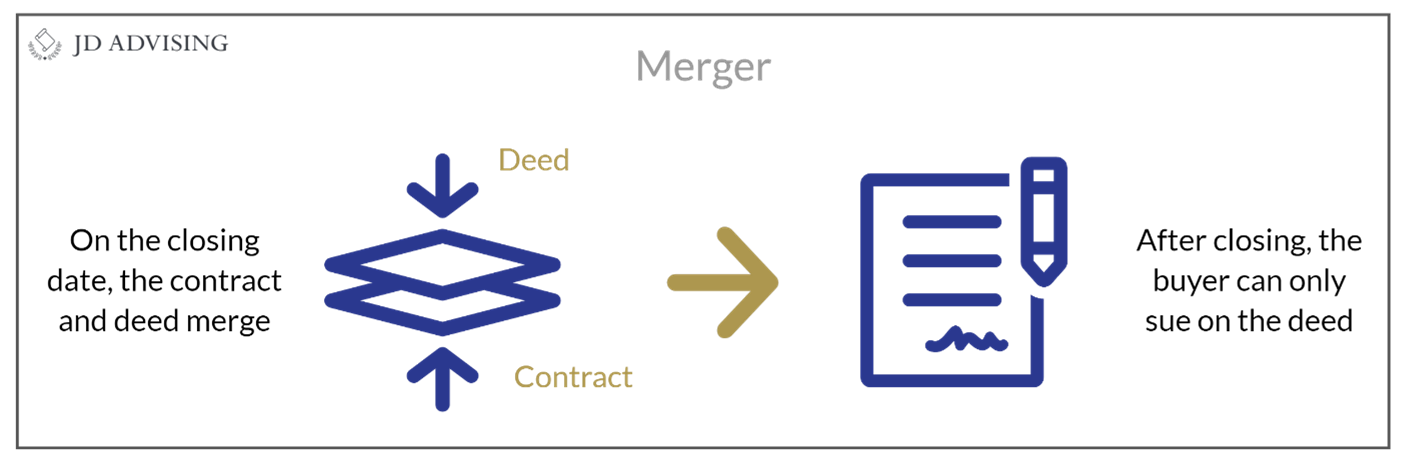

- Merger: once the closing occurs, the contract “merges” with the deed and the buyer can only sue on the deed at that point.

- Wild deed: a deed that is not properly recorded in the chain of title and is outside the chain of title.

- Mortgagor: the party responsible for the mortgage.

- Mortgagee: The bank (or whoever lends money in exchange for a security interest). If you mix up the terms “mortgagor” and “mortgagee” remember that “it is better to be the mortgagee!”

- Term-of-years lease: This term is deceiving because it does not have to be for years. This type of lease just has a specific start and end date . You can also think of this as a “fixed term” lease.

- Assignment: the tenant grants all the time remaining on the lease to the assignee.

- Sublease: the tenant grants only part of the time on the lease and still has an interest in the property.

- Easement: The non-possessory right to use the property of another . In other words, an easement holder does not own the property that is subject to the easement; it merely has a right to use the property.

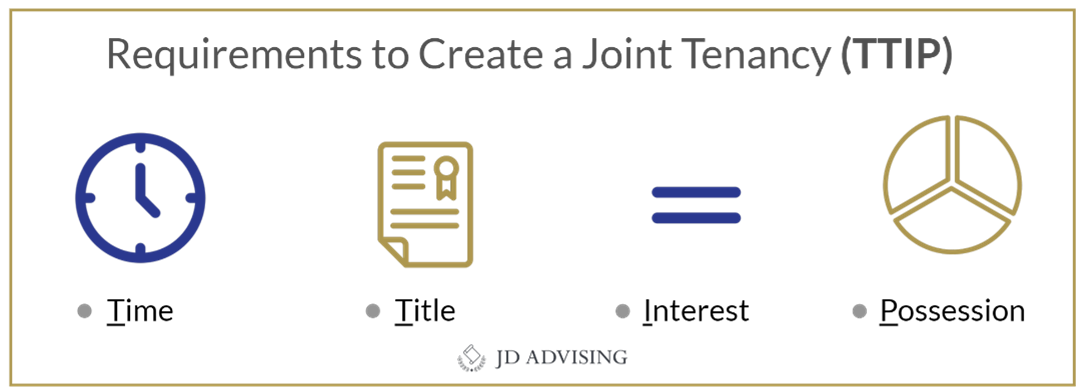

- Joint tenancy: When parties own an equal interest in land with the right of survivorship (as opposed to tenants in common , where there is no right of survivorship).

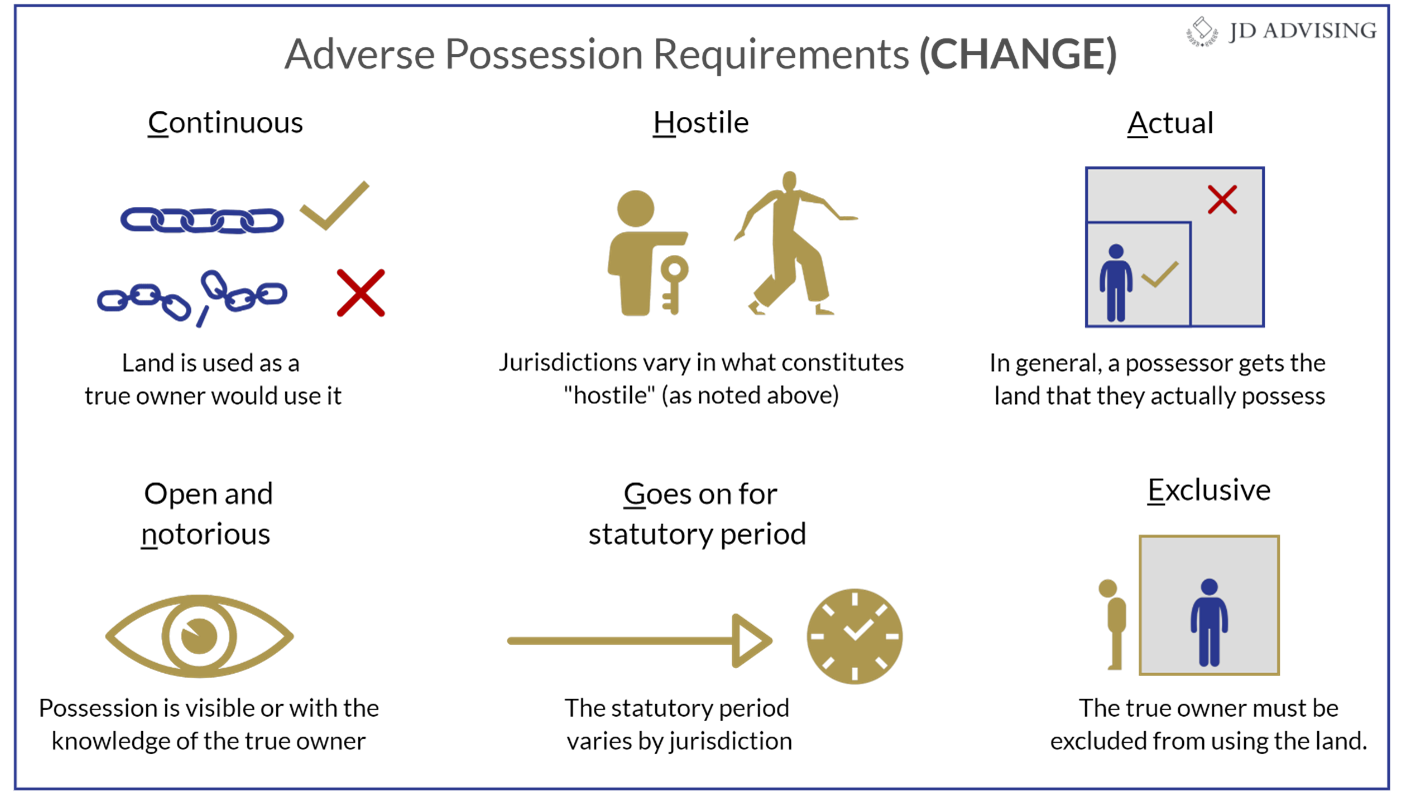

- Adverse possession: when a party possesses land adversely (e.g., without permission), that party can become the true owner of the land after the statutory period has passed .

4. Practice!

Practice is critical if you want to master Real Property on the MEE. As an added bonus, you may also see your MBE score improve if you practice writing answers to Real Property MEE essays.

Note that since many Real Property issues are tested repeatedly, practice can make a big difference. For example, many of the same concepts in February 2018 were tested in February 2010 ! Any student who completed the February 2010 question would have been well prepared for the Real Property MEE on the February 2018 exam.

Here, we have provided you with some links to free Real Property MEE questions and NCBE point sheets. (If you would like to purchase a book of Real Property MEE questions and NCBE point sheets, check out our MEE books here. You can also see some additional exams on the NCBE website for free here .)

- February 2023 Real Property MEE: this MEE covers adverse possession; color of title and constructive adverse possession; tacking for cause of action; and tolling of statute of limitations for disability (minor).

- July 2022 Real Property MEE: this MEE covers life estate, vested remainder, and duties of a life tenant; fee simple determinable and possibility of reverter; devisability, and RAP.

- February 2015 Real Property MEE: this MEE covers adverse possession and deeds.

- July 2013 Real Property MEE: this MEE covers deeds, merger, and warranties.

- February 2013 Real Property MEE: this MEE covers several landlord-tenant issues.

Go to the next topic, Secured Transactions .

Seeking mee expertise.

Our July 2024 bar exam sale is live! Check out our fantastic deals on everything you need to pass the bar

🌟 Freebies & Discounts

- Free Bar Exam Resource Center : Explore for leading guides, articles, and webinars.

- Expert-Crafted Bar Exam Guides : Unveil insights on high-frequency MEE topics and strategies for success.

- Free Webinars : Engage with top bar exam experts.

🔥 Top-Rated MEE Resources

- MEE One-Sheets : Boost your confidence with our most popular bar exam product!

- Bar Exam Outlines : Our comprehensive and condensed bar exam outlines present key information in an organized, easy-to-digest layout.

- NEW MEE Mastery Class : Unearth focused, engaging reviews of essential MEE topics.

- Bar Exam Crash Course and Mini Outlines : Opt for a swift, comprehensive refresher.

- MEE Private Tutoring and feedback : Elevate your approach with tailored success strategies.

- MEE Course : Preview our acclaimed five-star program for unmatched instruction, outlines, and questions.

🔥 NEW! Dive deep into our Repeat Taker Bar Exam Course and discover our unrivaled Platinum Guarantee Pass Program .

Related posts

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Public Interest

By using this site, you allow the use of cookies, and you acknowledge that you have read and understand our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service .

Cookie and Privacy Settings

We may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

You can read about our cookies and privacy settings in detail on our Privacy Policy Page.

- Privacy Overview

- Strictly Necessary Cookies

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

Good School, Rich School; Bad School, Poor School

The inequality at the heart of America’s education system

HARTFORD, Conn.—This is one of the wealthiest states in the union. But thousands of children here attend schools that are among the worst in the country. While students in higher-income towns such as Greenwich and Darien have easy access to guidance counselors, school psychologists, personal laptops, and up-to-date textbooks, those in high-poverty areas like Bridgeport and New Britain don’t. Such districts tend to have more students in need of extra help, and yet they have fewer guidance counselors, tutors, and psychologists; lower-paid teachers; more dilapidated facilities; and bigger class sizes than wealthier districts, according to an ongoing lawsuit. Greenwich spends $6,000 more per pupil per year than Bridgeport does, according to the State Department of Education .

The discrepancies occur largely because public school districts in Connecticut, and in much of America, are run by local cities and towns and are funded by local property taxes. High-poverty areas such as Bridgeport and New Britain have lower home values and collect less taxes, and so can’t raise as much money as a place like Darien or Greenwich, where homes are worth millions of dollars. Plaintiffs in a decade-old lawsuit in Connecticut, which heard closing arguments earlier this month, argue that the state should be required to ameliorate these discrepancies. Filed by a coalition of parents, students, teachers, unions, and other residents in 2005, the lawsuit, Connecticut Coalition for Justice in Education Funding (CCJEF) v. Rell , will decide whether inequality in school funding violates the state’s constitution.

“The system is unconstitutional,” the attorney for the plaintiffs Joseph P. Moodhe argued in Hartford Superior Court earlier this month, “because it is inadequately funded and because it is inequitably distributed.”

Connecticut is not the first state to wrestle with the conundrum caused by relying heavily on local property taxes to fund schools; since the 1970s, nearly every state has had litigation over equitable education, according to Michael Rebell, the executive director of the Campaign for Educational Equity at Teachers College at Columbia University. Indeed, the CCJEF lawsuit, first filed in 2005, is the state’s second major lawsuit on equity. The first, in 1977, resulted in the state being required to redistribute some funds among districts, though the plaintiffs in the CCJEF case argue the state has abandoned that system, called Educational Cost Sharing.

In every state, though, inequity between wealthier and poorer districts continues to exist. That’s often because education is paid for with the amount of money available in a district, which doesn’t necessarily equal the amount of money required to adequately teach students.

“Our system does not distribute opportunity equitably,” a landmark 2013 report from a group convened by the former Education Secretary Arne Duncan, the Equity and Excellence Commission, reported.

This is mainly because school funding is so local. The federal government chips in about 8 to 9 percent of school budgets nationally, but much of this is through programs such as Head Start and free and reduced-price lunch programs. States and local governments split the rest , though the method varies depending on the state.

Recommended Reading

Why School Funding Will Always Be Imperfect

How Fancy Water Bottles Became a 21st-Century Status Symbol

How Cats Used Humans to Conquer the World

Nationally, high-poverty districts spend 15.6 percent less per student than low-poverty districts do, according to U.S. Department of Education. Lower spending can irreparably damage a child’s future, especially for kids from poor families. A 20 percent increase in per-pupil spending a year for poor children can lead to an additional year of completed education, 25 percent higher earnings, and a 20-percentage-point reduction in the incidence of poverty in adulthood, according to a paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Violet Jimenez Sims, a Connecticut teacher, saw the differences between rich and poor school districts firsthand. Sims, who was raised in New Britain, one of the poorer areas of the state, taught there until the district shut down its bilingual education programs, at which point she got a job in Manchester, a more affluent suburb. In Manchester, students had individual Chromebook laptops, and Sims had up-to-date equipment, like projectors and digital whiteboards. In New Britain, students didn’t get individual computers, and there weren’t the guidance counselors or teacher’s helpers that there were in Manchester.

“I noticed huge differences, and I ended up leaving because of the impact of those things,” she told me. “Without money, there’s just a domino effect.” Students frequently had substitutes because so many teachers got frustrated and left; they didn’t have as much time to spend on computer projects because they had to share computers; and they were suspended more frequently in the poor district, she said. In the wealthier area, teachers and guidance counselors would have time to work with misbehaving students rather than expelling them right away.

Testimony during the CCJEF trial bears out the differences between poor areas like New Britain, Danbury, Bridgeport, and East Hartford, and wealthier areas like New Canaan, Greenwich, and Darien. Electives, field trips, arts classes, and gifted-and-talented programs available in wealthier districts have been cut in poorer ones. New Britain, where 80 percent of students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, receives half as much funding per special-education student as Darien. In Bridgeport, where class sizes hover near the contractual maximum of 29, students use 15-to 20-year-old textbooks; in New London, high-school teachers must duct tape windows shut to keep out the wind and snow and station trash cans in the hallways to collect rain. Where Greenwich’s elementary school library budget is $12,500 per year (not including staffing), East Hartford’s is zero.

All of this contributes to lower rates of success for poorer students. Connecticut recently implemented a system called NextGen to measure English and math skills and college and career readiness. Bridgeport’s average was 59.3 percent and New Britain 59.7 percent; Greenwich, by contrast, scored 89.3 percent and Darien scored 93.1. Graduation rates are lower in the poorer districts; there’s more chronic absenteeism.

The crux of the state’s case is that it spends enough on education, and that Connecticut has one of the country’s best public-school systems. The Educational Cost Sharing formula gets tinkered with by the legislature, the state says, and Connecticut still spends more on poor districts than many regions of the country. It says that what CCJEF is asking is essentially $2 billion more in taxpayer funding to make schools equitable—a sum that would be difficult to raise in a cash-strapped state.

“While we wholeheartedly share the goal of improving educational opportunities and outcomes for all Connecticut children, it is the state’s position both that we are fulfilling our constitutional responsibilities and that the decisions on how to advance those goals are best left to the appropriate policymakers: local communities and members of the General Assembly,” Jaclyn M. Falkowski, a spokeswoman for Connecticut Attorney General George Jepsen, told me in an email.

Yet the fact remains that delegating education funding to local communities increases inequality. That’s especially true in Connecticut, which has some of the biggest wealth disparities in the country. Indeed, in Connecticut, rich and poor districts often abut each other. Bridgeport is in the same county as Greenwich and Darien; East Hartford is poor, but nearby West Hartford is affluent. How did a state like Connecticut, which had one of the first laws making public education mandatory, become so divided? And why does such an unequal system exist in a country that puts such a high priority on equality?

Many of the problems that have arisen in Connecticut’s school system can be traced back to how public education was founded in this country, and how it was structured. It was a system that, at its outset, was very innovative and forward-thinking. But that doesn’t mean it is working for students today.

“The origins were very progressive, but what might have been progressive in one era can become inequitable in another,” Rebell told me.

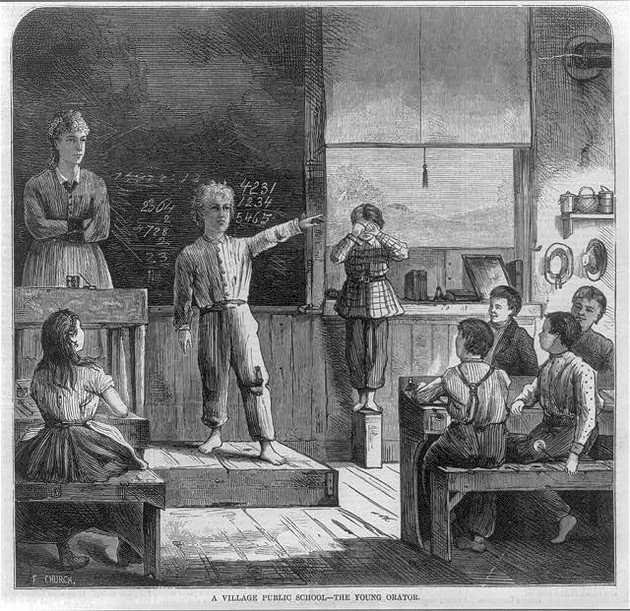

In the early days of the American colonies, the type of education a child received depended on whether the child was a he or a she (boys were much more likely to get educated at all), what color his or her skin was, where he or she lived, how much money his or her family had, and what church he or she belonged to. States like New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and New York depended on religious groups to educate children, while southern states depended on plantation owners, according to Charles Glenn, a professor of educational leadership at Boston University.

It was the Puritans of Massachusetts who first pioneered public schools, and who decided to use property-tax receipts to pay for them. The Massachusetts Act of 1642 required that parents see to it that their children knew how to read and write; when that law was roundly ignored, the colony passed the Massachusetts School Law of 1647 , which required every town with 50 households or more hire someone to teach the children to read and write. This public education was made possible by a property-tax law passed the previous year, according to a paper, “ The Local Property Tax for Public Schools: Some Historical Perspectives ,” by Billy D. Walker, a Texas educator and historian. Determined to carry out their vision for common school, the Puritans instituted a property tax on an annual basis—previously, it had been used to raise money only when needed. The tax charged specific people based on “visible” property including their homes as well as their sheep, cows, and pigs. Connecticut followed in 1650 with a law requiring towns to teach local children, and used the same type of financing.

Property tax was not a new idea; it came from a feudal system set up by William the Conquerer in the 11th century when he divided up England among his lieutenants, who required the people on the land to pay a fee in order to live there. What was new about the colonial property-tax system was how local it was. Every year, town councils would meet and discuss property taxes, how much various people should pay, and how that money was to be spent. The tax was relatively easy to assess because it was much simpler to see how much property a person owned that it was to see how much money he made. Unsurprisingly, the amounts various residents had to pay were controversial. (A John Adams – instituted national property tax in 1797 was widely hated and then repealed.)

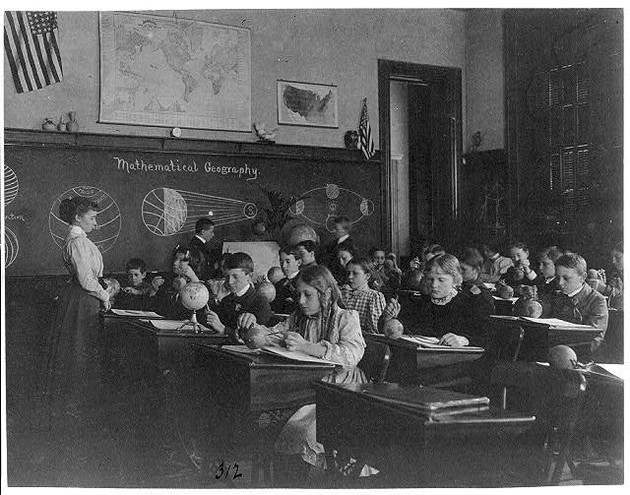

Initially, this system of using property taxes to pay for local schools did not lead to much inequality. That’s in part because the colonies were one of the most egalitarian places on the planet—for white people, at least. Public education began to become more common in the mid-19th century. As immigrants poured into the country’s cities, advocates puzzled over how to assimilate them. Their answer: public schools. The education reformer Horace Mann, for example, who became the secretary of the newly formed Massachusetts Board of Education in 1837, believed that public schooling was necessary for the creation of a national identity. He called education “the great equalizer of the conditions of men.”

Though schooling had, until then, been left up to local municipalities, states began to step in. After Mann created the Board of Education in 1837, he lobbied for and won a doubling of state expenditures on education. In 1852, Massachusetts passed the first law requiring parents to send their children to a public school for at least 12 weeks.

The idea of making free education a right was controversial—the “most explosive political issue in the 19th century, except for abolition,” Rebell said. Eventually, though, when reformers won, they pushed to get a right for all children to public schooling into states’ constitutions. The language of these education clauses varies; Connecticut’s constitution, for example, says merely that “there shall always be free public elementary and secondary schools in the state,” while Illinois’ constitution requires an “efficient system of high-quality public educational institutions and services.”

Despite widespread acceptance of mandatory public education by the end of the 19th century, the task of educating students remained a matter for individual states, not the nation as a whole. And states still left much of the funding of schools up to cities and towns, which relied on property tax. In 1890, property taxes accounted for 67.9 percent of public-education revenues in the U.S. This means that as America urbanized and industrialized and experienced more regional inequality, so, too, did the schools. Areas that had poorer families or less valuable land had less money for schools.

In the early part of the 20th century, states tried to step in and provide grants to districts so that school funding was equitable, according to Allan Odden, an expert in school finance who is a professor emeritus at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. But then wealthier districts would spend even more, buoyed by increasing property values, and the state subsidies wouldn’t go as far as they once had to make education equitable.

The disparities became more and more stark in the decades after World War II, when white families moved out of the cities into the suburbs and entered school systems there, and black families were stuck in the cities, where property values plummeted and schools lacked basic resources. In some states, where school districts were run on the county level, costs could be shared between rich and poor districts by combining and integrating them, especially after Brown v. Board of Education . But in states like Connecticut, with deeper histories of public schooling, there were hundreds of separate districts, and it was much more difficult to combine them or to equalize funding across them.

The most aggressive attempt to ameliorate these disparities came in 1973, in a Supreme Court case, San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez . It began when a father named Demetrio Rodriguez, whose sons attended a dilapidated elementary school in a poor area of San Antonio, sued the state of Texas, claiming that the way that schools were funded fundamentally violated the U.S. Constitution’s equal-protection clause. Rodriguez wanted the justices to apply the same logic they had applied in Brown v. Board of Education —that every student is guaranteed an equal opportunity to education. The justices disagreed. In a 5 – 4 decision, they ruled that there is no right to equal funding in education under the Constitution.

With Rodriguez , the justices essentially left the funding of education a state issue, forgoing a chance for the federal government to step in to adjust things Since then, school-funding lawsuits have been filed in 45 out of 50 states, according to Rebell.

Though it might seem odd that the Supreme Court has ruled that Americans have a right to live in a better zip code and a right to work at a company no matter their race, but not that every American child has the right to an equal education, there is legal justification for this. The Founders didn’t include a right to an education in the country’s founding documents. Though the federal government is involved in many parts of daily life in America, schooling is, and has always been, the responsibility of the states.

The plaintiffs in the Connecticut lawsuit want the state to undertake an intense study of local schools and see what is needed to give each child a good education. They want the state to look at how much a district can reasonably raise from its property taxes, and then come up with a formula for how different districts can share revenues so that schooling is more equitable. They don’t just want poor districts to get more money; they want poor districts to get enough money so that disadvantaged children can do just as well as children from wealthier areas.

“We think the state’s responsibility is to ensure that every child, in every school, in every school district, regardless of whether they’re impoverished, is given the opportunity to graduate from high school, and be able to be a full citizen and active in the civic life of their town, state and nation,” Jim Finley, the principal consultant for CCJEF, told me.

If CCJEF wins, it might take a page from other states that have tried to radically overhaul how schools are funded from district to district. After the Vermont Supreme Court ruled that the state’s education funding system was unconstitutional, the state in 1997 passed Act 60, which ensured that towns spent the same amount of revenue per pupil. Districts paid into a common pool, which was then redistributed to poorer areas. And since the New Jersey Supreme Court ruled in 1990 that the state’s funding system was unconstitutional in the Abbott v. Burke case, New Jersey has been required to spend extra money in 31 of the state’s poorest school districts.

Asking the state to step in can also have its downsides. A court decision in California in 1971, Serrano v. Priest , found that the state system, which relied heavily on property tax, violated the state’s constitution because there was such great inequality. The state decided then to make sure spending in every district was the same, not allowing for any disparity. But then, when voters in the state passed Proposition 13 in 1978, limiting the amount of property tax homeowners pay in a given year, the state was left trying to equalize schools with a shrinking pot of money. The result has been extremely low levels of state funding available, and shrinking expenditures on public schools throughout the state.

The federal government has provided additional funding for poor districts since 1965, when Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), but federal intervention in schools has always been controversial, with many parents and school-district leaders resisting federal dictates about curriculum and standards. The 2001 No Child Left Behind Act, which reauthorized ESEA, received pushback after schools struggled to keep up with testing requirements and progress reports. That law was replaced in 2015 with the Every Student Succeeds Act, which rolled back the federal government’s role in local education.