How to write a research proposal

What is a research proposal.

A research proposal should present your idea or question and expected outcomes with clarity and definition – the what.

It should also make a case for why your question is significant and what value it will bring to your discipline – the why.

What it shouldn't do is answer the question – that's what your research will do.

Why is it important?

Research proposals are significant because Another reason why it formally outlines your intended research. Which means you need to provide details on how you will go about your research, including:

- your approach and methodology

- timeline and feasibility

- all other considerations needed to progress your research, such as resources.

Think of it as a tool that will help you clarify your idea and make conducting your research easier.

How long should it be?

Usually no more than 2000 words, but check the requirements of your degree, and your supervisor or research coordinator.

Presenting your idea clearly and concisely demonstrates that you can write this way – an attribute of a potential research candidate that is valued by assessors.

What should it include?

Project title.

Your title should clearly indicate what your proposed research is about.

Research supervisor

State the name, department and faculty or school of the academic who has agreed to supervise you. Rest assured, your research supervisor will work with you to refine your research proposal ahead of submission to ensure it meets the needs of your discipline.

Proposed mode of research

Describe your proposed mode of research. Which may be closely linked to your discipline, and is where you will describe the style or format of your research, e.g. data, field research, composition, written work, social performance and mixed media etc.

This is not required for research in the sciences, but your research supervisor will be able to guide you on discipline-specific requirements.

Aims and objectives

What are you trying to achieve with your research? What is the purpose? This section should reference why you're applying for a research degree. Are you addressing a gap in the current research? Do you want to look at a theory more closely and test it out? Is there something you're trying to prove or disprove? To help you clarify this, think about the potential outcome of your research if you were successful – that is your aim. Make sure that this is a focused statement.

Your objectives will be your aim broken down – the steps to achieving the intended outcome. They are the smaller proof points that will underpin your research's purpose. Be logical in the order of how you present these so that each succeeds the previous, i.e. if you need to achieve 'a' before 'b' before 'c', then make sure you order your objectives a, b, c.

A concise summary of what your research is about. It outlines the key aspects of what you will investigate as well as the expected outcomes. It briefly covers the what, why and how of your research.

A good way to evaluate if you have written a strong synopsis, is to get somebody to read it without reading the rest of your research proposal. Would they know what your research is about?

Now that you have your question clarified, it is time to explain the why. Here, you need to demonstrate an understanding of the current research climate in your area of interest.

Providing context around your research topic through a literature review will show the assessor that you understand current dialogue around your research, and what is published.

Demonstrate you have a strong understanding of the key topics, significant studies and notable researchers in your area of research and how these have contributed to the current landscape.

Expected research contribution

In this section, you should consider the following:

- Why is your research question or hypothesis worth asking?

- How is the current research lacking or falling short?

- What impact will your research have on the discipline?

- Will you be extending an area of knowledge, applying it to new contexts, solving a problem, testing a theory, or challenging an existing one?

- Establish why your research is important by convincing your audience there is a gap.

- What will be the outcome of your research contribution?

- Demonstrate both your current level of knowledge and how the pursuit of your question or hypothesis will create a new understanding and generate new information.

- Show how your research is innovative and original.

Draw links between your research and the faculty or school you are applying at, and explain why you have chosen your supervisor, and what research have they or their school done to reinforce and support your own work. Cite these reasons to demonstrate how your research will benefit and contribute to the current body of knowledge.

Proposed methodology

Provide an overview of the methodology and techniques you will use to conduct your research. Cover what materials and equipment you will use, what theoretical frameworks will you draw on, and how will you collect data.

Highlight why you have chosen this particular methodology, but also why others may not have been as suitable. You need to demonstrate that you have put thought into your approach and why it's the most appropriate way to carry out your research.

It should also highlight potential limitations you anticipate, feasibility within time and other constraints, ethical considerations and how you will address these, as well as general resources.

A work plan is a critical component of your research proposal because it indicates the feasibility of completion within the timeframe and supports you in achieving your objectives throughout your degree.

Consider the milestones you aim to achieve at each stage of your research. A PhD or master's degree by research can take two to four years of full-time study to complete. It might be helpful to offer year one in detail and the following years in broader terms. Ultimately you have to show that your research is likely to be both original and finished – and that you understand the time involved.

Provide details of the resources you will need to carry out your research project. Consider equipment, fieldwork expenses, travel and a proposed budget, to indicate how realistic your research proposal is in terms of financial requirements and whether any adjustments are needed.

Bibliography

Provide a list of references that you've made throughout your research proposal.

Apply for postgraduate study

New hdr curriculum, find a supervisor.

Search by keyword, topic, location, or supervisor name

- 1800 SYD UNI ( 1800 793 864 )

- or +61 2 8627 1444

- Open 9am to 5pm, Monday to Friday

- Student Centre Level 3 Jane Foss Russell Building Darlington Campus

Scholarships

Find the right scholarship for you

Research areas

Our research covers the spectrum – from linguistics to nanoscience

Our breadth of expertise across our faculties and schools is supported by deep disciplinary knowledge. We have significant capability in more than 20 major areas of research.

High-impact research through state-of-the-art infrastructure

- Schools & departments

Writing your PhD research proposal

Find guidance on how to write your PhD research proposal and a template form for you to use to submit your research proposal.

By asking you for an outline research proposal we hope to get a good picture of your research interests and your understanding of what such research is likely to entail.

The University's application form is designed to enable you to give an overview of your academic experience and qualifications for study at postgraduate level. Your outline research proposal then gives us an idea of the kind of research you want to undertake. This, together with information from your referees, will help us assess whether the Moray House School of Education and Sport would be the appropriate place for you to pursue your research interests.

At the application stage you are unlikely to be in a position to provide a comprehensive research proposal; the detailed shaping up of a research plan would be done in conjunction with your supervisors(s). But it is important for us to appreciate what you are hoping to investigate, how you envisage carrying out the research, and what the results might be expected to contribute to current knowledge and understanding in the relevant academic field(s) of study. In writing your proposal, please indicate any prior academic or employment experience relevant to your planned research.

In your research proposal, please also ensure that you clearly identify the Moray House research cluster your proposal falls under, as well as two to three staff members with expertise in this area. We also encourage you to contact potential supervisors within your area of proposed research prior to submitting your application in order to gauge their interest and availability.

How to write your research proposal

The description of your proposed research should consist of 4-5 typed A4 sheets. It can take whatever form seems best, but should include some information about the following:

- The general area within which you wish to conduct research, and why (you might find it helpful to explain what stimulated your interest in your chosen research field, and any study or research in the area that you have already undertaken)

- The kind of research questions that you would hope to address, and why (in explaining what is likely to be the main focus of your research, it may be helpful to indicate, for example, why these issues are of particular concern and the way in which they relate to existing literature)

- The sources of information and type of research methods you plan to use (for example, how you plan to collect your data, which sources you will be targeting and how you will access these data sources).

In addition to the above, please include any comments you are able to make concerning:

- The approach that you will take to analysing your research data

- The general timetable you would follow for carrying out and writing up your research

- Any plans you may have for undertaking fieldwork away from Edinburgh

- Any problems that might be anticipated in carrying out your proposed research

Please note: This guidance applies to all candidates, except those applying to conduct PhD research as part of a larger, already established research project (for example, in the Institute for Sport, Physical Education & Health Sciences).

In this case, you should provide a two- to three-page description of a research project that you have already undertaken, as a means of complementing information given in the application form. If you are in any doubt as to what is appropriate please contact us:

Contact us by email: Education@[email protected]

All doctoral proposals submitted as part of an application will be run through plagiarism detection software.

Template form for your research proposal

All applicants for a PhD or MSc by Research are required to submit a research proposal as part of their application. Applicants must use the template form below for their research proposal. This research proposal should then be submitted online as part of your application. Please use Calibri size 11 font size and do not change the paragraph spacing (single, with 6pt after each paragraph) or the page margins.

You're viewing this site as a domestic an international student

You're a domestic student if you are:

- a citizen of Australia or New Zealand,

- an Australian permanent resident, or

- a holder of an Australian permanent humanitarian visa.

You're an international student if you are:

- intending to study on a student visa,

- not a citizen of Australia or New Zealand,

- not an Australian permanent resident, or

- a temporary resident (visa status) of Australia.

How to write a good PhD proposal

Study tips Published 3 Mar, 2022 · 5-minute read

Want to make sure your research degree starts smoothly? We spoke with 2 PhD candidates about overcoming this initial hurdle. Here’s their advice for how to write a good PhD proposal.

Writing your research proposal is an integral part of commencing a PhD with many schools and institutes, so it can feel rather intimidating. After all, how you come up with your PhD proposal could be the difference between your supervisor getting on board or giving your project a miss.

Let’s explore how to make a PhD research proposal with UQ candidates Chelsea Janke and Sarah Kendall.

Look at PhD proposal examples

Look at other PhD proposals that have been successful. Ask current students if you can look at theirs.

Nobody’s asking you to reinvent the wheel when it comes to writing your PhD proposal – leave that for your actual thesis. For now, while you’re just working out how to write a PhD proposal, examples are a great starting point.

Chelsea knows this step is easier if you’ve got a friend who is already doing a PhD, but there are other ways to find a good example or template.

“Look at other PhD proposals that have been successful,” she says.

“Ask current students if you can look at theirs.”

“If you don’t know anyone doing their PhD, look online to get an idea of how they should be structured.”

What makes this tricky is that proposals can vary greatly by field and disciplinary norms, so you should check with your proposed supervisor to see if they have a specific format or list of criteria to follow. Part of writing a good PhD proposal is submitting it in a style that's familiar to the people who will read and (hopefully) become excited by it and want to bring you into their research area.

Here are some of the key factors to consider when structuring your proposal:

- meeting the expected word count (this can range from a 1-page maximum to a 3,000-word minimum depending on your supervisor and research area)

- making your bibliography as detailed as necessary

- outlining the research questions you’ll be trying to solve/answer

- discussing the impact your research could have on your field

- conducting preliminary analysis of existing research on the topic

- documenting details of the methods and data sources you’ll use in your research

- introducing your supervisor(s) and how their experience relates to your project.

Please note this isn't a universal list of things you need in your PhD research proposal. Depending on your supervisor's requirements, some of these items may be unnecessary or there may be other inclusions not listed here.

Ask your planned supervisor for advice

Alright, here’s the thing. If sending your research proposal is your first point of contact with your prospective supervisor, you’ve jumped the gun a little.

You should have at least one researcher partially on board with your project before delving too deep into your proposal. This ensures you’re not potentially spending time and effort on an idea that no one has any appetite for. Plus, it unlocks a helpful guide who can assist with your proposal.

PhD research isn’t like Shark Tank – you’re allowed to confer with academics and secure their support before you pitch your thesis to them. Discover how to choose the right PhD supervisor for you.

For a time-efficient strategy, Chelsea recommends you approach your potential supervisor(s) and find out if:

- they have time to supervise you

- they have any funds to help pay for your research (even with a stipend scholarship , your research activities may require extra money)

- their research interests align with yours (you’ll ideally discover a mutual ground where you both benefit from the project).

“The best way to approach would be to send an email briefly outlining who you are, your background, and what your research interests are,” says Chelsea.

“Once you’ve spoken to a potential supervisor, then you can start drafting a proposal and you can even ask for their input.”

Chelsea's approach here works well with some academics, but keep in mind that other supervisors will want to see a research proposal straight away. If you're not sure of your proposed supervisor's preferences, you may like to cover both bases with an introductory email that has a draft of your research proposal attached.

Sarah agrees that your prospective supervisor is your most valuable resource for understanding how to write a research proposal for a PhD application.

“My biggest tip for writing a research proposal is to ask your proposed supervisor for help,” says Sarah.

“Or if this isn’t possible, ask another academic who has had experience writing research proposals.”

“They’ll be able to tell you what to include or what you need to improve on.”

Find the 'why' and focus on it

One of the key aspects of your research proposal is emphasising why your project is important and should be funded.

Your PhD proposal should include your major question, your planned methods, the sources you’ll cite, and plenty of other nitty gritty details. But perhaps the most important element of your proposal is its purpose – the reason you want to do this research and why the results will be meaningful.

In Sarah’s opinion, highlighting the 'why' of your project is vital for your research proposal.

“From my perspective, one of the key aspects of your research proposal is emphasising why your project is important and should be funded,” she says.

“Not only does this impact whether your application is likely to be successful, but it could also impact your likelihood of getting a scholarship .”

Imagine you only had 60 seconds to explain your planned research to someone. Would you prefer they remember how your project could change the world, or the statistical models you’ll be using to do it? (Of course, you’ve got 2,000 words rather than 60 seconds, so do make sure to include those little details as well – just put the why stuff first.)

Proofread your proposal, then proof it again

As a PhD candidate, your attention to detail is going to be integral to your success. Start practising it now by making sure your research proposal is perfect.

Chelsea and Sarah both acknowledge that clarity and writing quality should never be overlooked in a PhD proposal. This starts with double-checking that the questions of your thesis are obvious and unambiguous, followed by revising the rest of your proposal.

“Make sure your research questions are really clear,” says Sarah.

“Ensure all the writing is clear and grammatically correct,” adds Chelsea.

“A supervisor is not going to be overly keen on a prospective student if their writing is poor.”

It might sound harsh, but it’s fair. So, proofread your proposal multiple times – including after you get it back from your supervisor with any feedback and notes. When you think you’ve got the final, FINAL draft saved, sleep on it and read it one more time the next morning.

Still feeling a little overwhelmed by your research proposal? Stay motivated with these reasons why a PhD is worth the effort .

Want to learn more from Chelsea and Sarah? Easy:

- Read about Chelsea’s award-winning PhD thesis on keeping crops healthy.

- Read Sarah’s series on becoming a law academic .

Share this Facebook Twitter LinkedIn Email

Related stories

How to get a PhD

4-minute read

How to find a PhD supervisor

5-minute read

How long does a PhD take?

3-minute read

Tips for PhD students from Samantha and Glenn

7-minute read

- Log in

- Site search

How to write a successful research proposal

As the competition for PhD places is incredibly fierce, your research proposal can have a strong bearing on the success of your application - so discover how to make the best impression

What is a research proposal?

Research proposals are used to persuade potential supervisors and funders that your work is worthy of their support. These documents setting out your proposed research that will result in a Doctoral thesis are typically between 1,500 and 3,000 words in length.

Your PhD research proposal must passionately articulate what you want to research and why, convey your understanding of existing literature, and clearly define at least one research question that could lead to new or original knowledge and how you propose to answer it.

Professor Leigh Wilson, director of the graduate school at the University of Westminster, explains that while the research proposal is about work that hasn't been done yet, what prospective supervisors and funders are focusing on just as strongly is evidence of what you've done - how well you know existing literature in the area, including very recent publications and debates, and how clearly you've seen what's missing from this and so what your research can do that's new. Giving a strong sense of this background or frame for the proposed work is crucial.

'Although it's tempting to make large claims and propose research that sweeps across time and space, narrower, more focused research is much more convincing,' she adds. 'To be thorough and rigorous in the way that academic work needs to be, even something as long as a PhD thesis can only cover a fairly narrow topic. Depth not breadth is called for.'

The structure of your research proposal is therefore important to achieving this goal, yet it should still retain sufficient flexibility to comfortably accommodate any changes you need to make as your PhD progresses.

Layout and formats vary, so it's advisable to consult your potential PhD supervisor before you begin. Here's what to bear in mind when writing a research proposal.

Your provisional title should be around ten words in length, and clearly and accurately indicate your area of study and/or proposed approach. It should be catchy, informative and interesting.

The title page should also include personal information, such as your name, academic title, date of birth, nationality and contact details.

Aims and objectives

This is a short summary of your project. Your aims should be two or three broad statements that emphasise what you ultimately want to achieve, complemented by several focused, feasible and measurable objectives - the steps that you'll take to answer each of your research questions. This involves clearly and briefly outlining:

- how your research addresses a gap in, or builds upon, existing knowledge

- how your research links to the department that you're applying to

- the academic, cultural, political and/or social significance of your research questions.

Literature review

This section of your PhD proposal discusses the most important theories, models and texts that surround and influence your research questions, conveying your understanding and awareness of the key issues and debates.

It should focus on the theoretical and practical knowledge gaps that your work aims to address, as this ultimately justifies and provides the motivation for your project.

Methodology

Here, you're expected to outline how you'll answer each of your research questions. A strong, well-written methodology is crucial, but especially so if your project involves extensive collection and significant analysis of primary data.

In disciplines such as humanities the research proposal methodology identifies the data collection and analytical techniques available to you, before justifying the ones you'll use in greater detail. You'll also define the population that you're intending to examine.

You should also show that you're aware of the limitations of your research, qualifying the parameters that you plan to introduce. Remember, it's more impressive to do a fantastic job of exploring a narrower topic than a decent job of exploring a wider one.

Concluding or following on from your methodology, your timetable should identify how long you'll need to complete each step - perhaps using bi-weekly or monthly timeslots. This helps the reader to evaluate the feasibility of your project and shows that you've considered how you'll go about putting the PhD proposal into practice.

Bibliography

Finally, you'll provide a list of the most significant texts, plus any attachments such as your academic CV . Demonstrate your skills in critical reflection by selecting only those resources that are most appropriate.

Final checks

Before submitting this document along with your PhD application, you'll need to ensure that you've adhered to the research proposal format. This means that:

- every page is numbered

- it's professional, interesting and informative

- the research proposal has been proofread by both an experienced academic (to confirm that it conforms to academic standards) and a layman (to correct any grammatical or spelling errors)

- it has a contents page

- you've used a clear and easy-to-read structure, with appropriate headings.

Research proposal examples

To get a better idea of how your PhD proposal may look, some universities have provided examples of research proposals for specific subjects:

- The Open University - Social Policy and Criminology

- University of Sheffield - Sociological Studies

- University of Sussex

- University of York - Politics

Find out more

- Explore PhD studentships .

- For tips on writing a thesis, see 7 steps to writing a dissertation .

- Read more about PhD study .

How would you rate this page?

On a scale where 1 is dislike and 5 is like

- Dislike 1 unhappy-very

- Like 5 happy-very

Thank you for rating the page

School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies

How to write a phd research proposal.

In order to help you with your application, the information below aims to give some guidance on how a typical research proposal might look.

Your research proposal is a concise statement (up to 3,000 words) of the rationale for your research proposal, the research questions to be answered and how you propose to address them. We know that during the early stages of your PhD you are likely to refine your thinking and methodology in discussion with your supervisors.

However, we want to see that you can construct a fairly rigorous, high quality research proposal.

We use your research proposal to help us decide whether you would be a suitable candidate to study at PhD level. We therefore assess your proposal on its quality, originality, and coherence. It also helps us to decide if your research interests match those of academics in the School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies (SPAIS) and whether they would be able to provide suitably qualified supervision for your proposed research.

Format of the research proposal

Your proposal should include the following:

Title. A short, indicative title is best.

Abstract. This is a succinct summary of your research proposal (approximately 200-300 words) that will present a condensed outline, enabling the reader to get a very quick overview of your proposed project, lines of inquiry and possible outcomes. An abstract is often written last, after you have written the proposal and are able to summarise it effectively.

Rationale for the research project. This might include a description of the question/debate/phenomenon of interest; an explanation of why the topic is of interest to you; and an outline of the reasons why the topic should be of interest to research and/ or practice (the 'so what?' question).

Aims and initial research question. What are the aims and objectives of the research? State clearly the puzzle you are addressing, and the research question that you intend to pursue. It is acceptable to have multiple research questions, but it is a good idea to clarify which is the main research question. If you have hypotheses, discuss them here. A research proposal can and should make a positive and persuasive first impression and demonstrate your potential to become a good researcher. In particular, you need to demonstrate that you can think critically and analytically as well as communicate your ideas clearly.

Research context for your proposed project. Provide a short introduction to your area of interest with a succinct, selective and critical review of the relevant literature. Demonstrate that you understand the theoretical underpinnings and main debates and issues in your research area and how your proposed research will make an original and necessary contribution to this. You need to demonstrate how your proposed research will fill a gap in existing knowledge.

Intended methodology. Outline how you plan to conduct the research and the data sources that you will use. We do not expect you to have planned a very detailed methodology at this stage, but you need to provide an overview of how you will conduct your research (qualitative and/or quantitative methods) and why this methodology is suited for your proposed study. You need to be convincing about the appropriateness and feasibility of the approaches you are suggesting, and reflective about problems you might encounter (including ethical and data protection issues) in collecting and analysing your data.

Expected outcomes and impact. How do you think the research might add to existing knowledge; what might it enable organisations or interested parties to do differently? Increasingly in academia (and this is particularly so for ESRC-funded studentships), PhD students are being asked to consider how their research might contribute to both academic impact and/or economic and societal impact. (This is well explained on the ESRC website if you would like to find out more.) Please consider broader collaborations and partnerships (academic and non-academic) that will support your research. Collaborative activity can lead to a better understanding of the ways in which academic research can translate into practice and it can help to inform and improve the quality of your research and its impact.

Timetable. What is your initial estimation of the timetable of the dissertation? When will each of the key stages start and finish (refining proposal; literature review; developing research methods; fieldwork; analysis; writing the draft; final submission). There are likely to overlaps between the stages.

Why Bristol? Why – specifically – do you want to study for your PhD at Bristol ? How would you fit into the School's research themes and research culture . You do not need to identify supervisors at the application stage although it can be helpful if you do.

Bibliography. Do make sure that you cite what you see as the key readings in the field. This does not have to be comprehensive but you are illustrating the range of sources you might use in your research.

We expect your research proposal to be clear, concise and grammatically correct. Prior to submitting your research proposal, please make sure that you have addressed the following issues:

- Have you included a clear summary of what the proposed research is about and why it is significant?

- Have you clearly identified what your proposed research will add to our understanding of theory, knowledge or research design?

- Does it state what contributions it will make to policy and/or practice?

- Does the proposal clearly explain how you will do the research?

- Is the language clear and easy to understand by someone who is not an expert in the field?

- Is the grammar and spelling correct?

How to Write a PhD Research Proposal

Understand and harness the key elements of a succinct research plan while preparing your PhD proposal. Join our Massive Open Online Course (MOOC).

.jpg)

Audun Bjerknes filming Fikadu Balcha, PhD student during a former MOOC. Photo: Øystein Røynesdal.

The University of Oslo (UiO), Norway, and Jimma University (JU), Ethiopia, have developed a free online course, a MOOC, on how to write a PhD proposal as part of the mobility and capacity-developing project NORPART: EXCEL SMART. It is funded by DIKUs NORPART program and the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Oslo.

This online course is based on a scientific writing workshop delivered by Dr. Jeanette Magnus and Prof. Anne Moen in Addis Abeba and Jimma under the NORHED: SACCADE program funded by NORAD.

So far over 5000 participants have had the chance to follow the MOOC, and this August it is run for the third time.

The online course is open for registration on the FutureLearn platform and runs for four

weeks from August 17th. We recommend that all participants start from Week 1, to get the full benefit of interacting with fellow participants as well as Prof. Anne Moen.

Although it will be possible to join the course at any time throughout the four weeks run and even for four weeks after. I.e. deadline for joining will be October 11th.

The course is free and available to participants all over the world as long as you have internet access.

Prof. Anne Moen spearheads the course and is the lead educator, while carefully selected PhD candidates at UiO from Jimma University from the SACCADE program, who completed the Scientific Workshop courses, and Dr. Jeanette Magnus contribute by presenting several video lectures.

Please read more about the course in the following sections, or go to the FutureLearn website to learn more .

Learn how to develop a successful PhD proposal

Successful PhD research requires systematic preparation, planning, critical thinking and dedicated work. In this course, you will harness the key elements of the main sections in a research proposal and solve common challenges when planning and writing a PhD proposal.

You will learn how to structure, define and present your research idea in writing. During the course, you can develop your own research objectives and sub-questions, argue for their importance, and outline the context and the setup of the study. You will also learn how to manage a project.

Although we are starting from a focus in health sciences, the content of the PhD proposal, and the planning strategy of a research study is relevant in other disciplines.

What topics will you cover?

- Defining the research idea, writing a research statement with objective with sub questions.

- Identifying and writing a literature summary and review.

- Empirical, conceptual or theoretical foundations of a research study.

- Research ethics, fraud and plagiarism in research.

- Research design and methodological approaches.

- Data collection strategies, sampling, instruments and biases.

- Fieldwork and contingency planning.

- How to organize your PhD project.

What will you achieve?

At the end of the course, you will be able to:

- Present your research statement with objectives and sub-questions

- Identify gaps in the relevant research literature and argue for why your research matters

- Ensure that the planned PhD-study follows the conventions for sound ethical conduct

- Appraise your work with the help of peers, course educators and mentors

- Discuss the setup for sample, data collection strategies and present a plan for data analysis

- Explain how you will organize your PhD project

- Evaluate what you learned by giving and receiving feedback on your weekly assignments

- Collaborate with peers and find ways to solve possible challenges in your PhD proposal

Who is the course for?

- Primary target group: Future PhD students aiming to develop a PhD proposal and improving their skills in research proposal writing.

- Secondary target group: Any junior researcher working on harnessing their small research grant application skills.

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

IOE Writing Centre

Develop a Research Proposal

The sections below provide guidance on developing a research proposal as part of postgraduate / doctoral studies or when applying for a research grant.

Please note that the guidance below is generic and you should follow any additional specific guidance given by your department or funding body.

What is a research proposal? A research proposal provides a detailed plan of a research project before you undertake the research. A proposal is usually submitted before you undertake research for a final dissertation during postgraduate study, and before or during doctoral studies. A proposal may also be submitted as part of an application for a funding grant.

What to include in a research proposal

A research proposal will usually (but not always) include the following key elements:

- An outline of the background and context of the research topic / issue

- Reasons why the specific topic / issue is important (rationale)

- A review of key literature related to the topic / issue

- An outline of the intended research methodology (including consideration of ethical issues)

- A discussion of ethical issues

- How the findings will be disseminated

- A timescale for the research

Getting started

Start by choosing a topic or issue related to your course. A broader topic / issue will need to be narrowed down to a more specific focus that can be explored or investigated. Recommendations for further research at the end of published papers can be a useful source of ideas.

To help narrow down a topic / issue and plan your research project:

- Start by re-reading some of the research papers which you read as part of your course. Conduct a preliminary review of the literature related to the topic / issue. This can include literature related to theoretical concepts as well as practical research.

- Aim to identify what is currently known and whether there are any 'gaps' in existing knowledge. This will enable you to determine how your own research will contribute to and build on what is already known.

- Identify how research on the topic / issue has previously been conducted in terms of, for example: approach, methods, analysis of data.

- It will also be useful to refer to literature on research methods - check the recommended reading list for your dissertation module / Centre for Doctoral Education guidance.

- For Masters level research, the contribution to existing knowledge does not necessarily need to be something completely new that has never been explored before. Your research could make a contribution to existing knowledge by, for example: Adopting a less commonly used research approach / research method or focusing on a particular context (such as a school or country) where a limited amount of research has been conducted

- For doctoral level research, there will usually be a need to demonstrate more originality.

Below is an outline of the sections typically included in a research proposal. Specific guidance on how to structure the research proposal for a dissertation or doctoral research will usually be given by individual departments. If you are applying for doctoral research funding, specific guidelines will be stipulated by the funding body. It is important to follow specific guidance given by your department or funding body when writing your own research proposal for a dissertation or PhD application, but the following can be used as general guidance .

Title / working title of the research

An initial idea of the title should be given - this is likely to be revised as the research progresses and can therefore be a tentative suggestion at the proposal stage.

Introduction

The context and background of the research topic / issue, as well as the rationale for undertaking the research, should be outlined in the introduction section. Reference to key literature should be included to strengthen the rationale for conducting the research. This will enable the reader to understand what the research will be about and why it is important. At the end of the introduction, include an outline (or synopsis) of how the proposal is organised.

Literature review

This should expand on the key literature referred to in the introduction. The review of the literature will need to go further than listing individual studies or theories. You will need to demonstrate an awareness of the current state of knowledge and an understanding of key lines of argument and debates on the topic / issue. The literature will need to be critically analysed and evaluated rather than just described. This means demonstrating how studies, arguments and debates are linked and how the existing body of research links to your own research area / issue.

Research aims and questions

The research aims and research questions should be used to guide your research. The aims of the research relate to the purpose of conducting the research and what you specifically want to achieve. The research questions should be formulated to show how you will achieve the aims of the research and what you want to find out. The research aims and questions can either be stated at the end of the introduction (before the outline of the proposal) or after the literature review - guidance from your department / funding body may specify this.

Methodology

The methodology section of the proposal should outline how the research will be conducted. This should generally include a description and justification of: sample / participants, methods, data collection and analysis, and ethical considerations. To justify the chosen methodology, you can refer to recommended reading for research methods as well as previous studies conducted on your chosen topic.

Including a detailed discussion of the ethics of your research project can really strengthen the proposal. It forces you to think in very practical and detailed terms about what you are planning to do.

You may be required to include a schedule or plan of how you intend to conduct the research within a specified timeframe. This can be presented in a variety of ways but should generally include specific milestones (e.g. collection of data, analysis of findings) and intended completion dates.

Reference list

The reference list should include all sources cited in the research proposal. Departmental guidelines for referencing should be followed for in-text citations and the reference list.

IOE Writing Centre Online

Self-access resources from the Academic Writing Centre at the UCL Institute of Education.

Anonymous Suggestions Box

Information for Staff

Academic Writing Centre

Academic Writing Centre, UCL Institute of Education [email protected] Twitter: @AWC_IOE Skype: awc.ioe

- Undergraduate courses

- Postgraduate courses

- January starts

- Foundation courses

- Apprenticeships

- Part-time and short courses

- Apply undergraduate

- Apply postgraduate

Search for a course

Search by course name, subject, and more

- Undergraduate

- Postgraduate

- (suspended) - Available in Clearing Not available in Clearing location-sign UCAS

Fees and funding

- Tuition fees

- Scholarships

- Funding your studies

- Student finance

- Cost of living support

Why study at Kent

Student life.

- Careers and employability

- Student support and wellbeing

- Our locations

- Placements and internships

- Year abroad

- Student stories

- Schools and colleges

- International

- International students

- Your country

- Applicant FAQs

- International scholarships

- University of Kent International College

- Campus Tours

- Applicant Events

- Postgraduate events

- Maps and directions

- Research strengths

- Research centres

- Research impact

Research institutes

- Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology

- Institute of Cyber Security for Society

- Institute of Cultural and Creative Industries

- Institute of Health, Social Care and Wellbeing

Research students

- Graduate and Researcher College

- Research degrees

- Find a supervisor

- How to apply

Popular searches

- Visits and Open Days

- Jobs and vacancies

- Accommodation

- Student guide

- Library and IT

- Research highlights

- Signature themes

- Partner with us

- Student Guide

- Student Help

- Health & wellbeing

- Student voice

- Living at Kent

- Careers & volunteering

- Diversity at Kent

- Finance & funding

- Life after graduation

Research projects & dissertations

Developing a research proposal.

The following guide has been created for you by the Student Learning Advisory Service . For more detailed guidance and to speak to one of our advisers, please book an appointment or join one of our workshops . Alternatively, have a look at our SkillBuilder skills videos.

What is a research proposal

A research proposal outlines a case for undertaking a piece of research and how it will be carried out. Research proposals are an important first step in any research project. The process of drafting a proposal, negotiating a way forward with your supervisor/tutor and then redrafting, can be lengthy. However, it is important to remember that your supervisor/tutor is responsible for ensuring that your proposal:

- has a specific research question or enquiry.

- meets the academic requirements of your course.

- is feasible in the available time and with the available resources.

Departmental procedures for Research Proposals vary across the university. ALWAYS check your course documentation for precise information about the forms to be completed and deadlines for submission. If in doubt, check with your supervisor.

Components of a research proposal

Word counts and structure vary, but on average they are usually between 1500 to 2000 words and include the following:

- Research context and rationale for research

Research issue and questions

Proposed research methodology, use of research findings.

- Initial bibliography

Time plan/schedule

Before you submit a research proposal check whether there is a prescribed format for the application and, if there is, follow it, even if it differs from what is described in this guide.

Key components of a research proposal explained:

Sum up the objective of the research and the proposed methodology concisely.

Research context and rationale

Explain (supported with research) the situation that has led to the need for the research (e.g. when, what, who, why) and the reasons why this research is necessary. Also consider your own background and clarify how you are particularly well-placed or qualified to undertake this research.

Explain the key issues or gaps in knowledge that your research will address. Indicate what core questions your research will be answering.

Explain your research design using research to justify your decisions. Typical areas of discussion:

- How research questions relate to approaches to research design in the field

- Sample group and sample methods, supported with research

- Measurement instruments or data collection procedures to be used, supported with research on why, how and when these instruments/approaches are generally used, consider strengths and weaknesses

- Data analysis techniques to be used, supported with research on why, how and when these techniques are generally used, consider strengths and weaknesses

Explain how your research will be used. For example, it may resolve theoretical issues in your field, or lead to the development of new theoretical models; it may affect the ways in which people working in the field operate in future, or influence politicians and other decision makers. Back up your arguments with details in order to build up a case for supporting the research. Give brief details of any immediate applications of your research, including any further research that may be done to build on your findings.

A bibliography

As in any piece of academic writing, you should list the articles and texts to which you have referred to in your proposal.

Draw up a schedule that reflects a realistic appreciation of the time your research will take to complete. Do not be over-optimistic when working out time frames.

- The Open University

- Guest user / Sign out

- Study with The Open University

My OpenLearn Profile

Personalise your OpenLearn profile, save your favourite content and get recognition for your learning

Writing your research proposal

A doctoral research degree is the highest academic qualification that a student can achieve. The guidance provided in these articles will help you apply for one of the two main types of research degree offered by The Open University.

A traditional PhD, a Doctor of Philosophy, usually studied full-time, prepares candidates for a career in Higher Education.

A Professional Doctorate is usually studied part-time by mid- to late-career professionals. While it may lead to a career in Higher Education, it aims to improve and develop professional practice.

We offer two Professional Doctorates:

- A Doctorate in Education, the EdD and

- a Doctorate in Health and Social Care, the DHSC.

Achieving a doctorate, whether a PhD, EdD or DHSC confers the title Dr.

Why write a Research Proposal?

To be accepted onto a PhD / Professional Doctorate (PD) programme in the Faculty of Wellbeing, Education and Language Studies (WELS) at The Open University, you are required to submit a research proposal. Your proposal will outline the research project you would like to pursue if you’re offered a place.

When reviewing your proposal, there are three broad considerations that those responsible for admission onto the programme will bear in mind:

1. Is this PhD / PD research proposal worthwhile?

2. Is this PhD / PD candidate capable of completing a doctorate at this university?

3. Is this PhD / PD research proposal feasible?

Writing activity: in your notebook, outline your response to each of the questions below based on how you would persuade someone with responsibility for admission onto a doctoral programme to offer you a place:

- What is your proposed research about & why is it worthy of three or more years of your time to study?

- What skills, knowledge and experience do you bring to this research – If you are considering a PhD, evidence of your suitability will be located in your academic record for the Prof Doc your academic record will need to be complemented by professional experience.

- Can you map out the different stages of your project, and how you will complete it studying i) full-time for three years ii) part-time for four years.

The first sections of the proposal - the introduction, the research question and the context are aimed at addressing considerations one and two.

Your Introduction

Your Introduction will provide a clear and succinct summary of your proposal. It will include a title, research aims and research question(s), all of which allows your reader to understand immediately what the research is about and what it is intended to accomplish. We recommend that you have one main research question with two or three sub research questions. Sub research questions are usually implied by, or embedded within, your main research question.

Please introduce your research proposal by completing the following sentences in your notebook: I am interested in the subject of ………………. because ……………… The issue that I see as needing investigation is ………………. because ………………. Therefore, my proposed research will answer or explore [add one main research question and two sub research questions] …... I am particularly well suited to researching this issue because ………………. So in this proposal I will ………………. Completing these prompts may feel challenging at this stage and you are encouraged to return to these notes as you work through this page.

Research questions are central to your study. While we are used to asking and answering questions on a daily basis, the research question is quite specific. As well as identifying an issue about which your enthusiasm will last for anything from 3 – 8 years, you also need a question that offers the right scope, is clear and allows for a meaningful answer.

Research questions matter. They are like the compass you use to find your way through a complicated terrain towards a specific destination.

A good research proposal centres around a good research question. Your question will determine all other aspects of your research – from the literature you engage with, the methodology you adopt and ultimately, the contribution your research makes to the existing understanding of a subject. How you ask your question, or the kinds of question you ask, matters because there is a direct connection between question and method.

You may be inclined to think in simplistic terms about methods as either quantitative or qualitative. We will discuss methodology in more detail in section three. At this point, it is more helpful to think of your methods in terms of the kinds of data you aim to generate. Mostly, this falls into two broad categories, qualitative and quantitative (sometimes these can be mixed). Many academics question this distinction and suggest the methodology categories are better understood as unstructured or structured.

For example, let’s imagine you are asking a group of people about their sugary snack preferences.

You may choose to interview people and transcribe what they say are their motivations, feelings and experiences about a particular sugary snack choice. You are most likely to do this with a small group of people as it is time consuming to analyse interview data.

Alternatively, you may choose to question a number of people at some distance to yourself via a questionnaire, asking higher level questions about the choices they make and why.

Once you have a question that you are comfortable with, the rest of your proposal is devoted to explaining, exploring and elaborating your research question. It is probable that your question will change through the course of your study.

At this early stage it sets a broad direction for what to do next: but you are not bound to it if your understanding of your subject develops, your question may need to change to reflect that deeper understanding. This is one of the few sections where there is a significant difference between what is asked from PhD candidates in contrast to what is asked from those intending to study a PD. There are three broad contexts for your research proposal.

If you are considering a PD, the first context for your proposal is professional:

This context is of particular interest to anyone intending to apply for the professional doctorate. It is, however, also relevant if you are applying for a PhD with a subject focus on education, health, social care, languages and linguistics and related fields of study.

You need to ensure your reader has a full understanding of your professional context and how your research question emerges from that context. This might involve exploring the specific institution within which your professionalism is grounded – a school or a care home. It might also involve thinking beyond your institution, drawing in discussion of national policy, international trends, or professional commitments. There may be several different contexts that shape your research proposal. These must be fully explored and explained.

Postgraduate researcher talks about research questions, context and why it mattered

The second context for your proposal is you and your life:

Your research proposal must be based on a subject about which you are enthused and have some degree of knowledge. This enthusiasm is best conveyed by introducing your motivations for wanting to undertake the research. Here you can explore questions such as – what particular problem, dilemma, concern or conundrum your proposal will explore – from a personal perspective. Why does this excite you? Why would this matter to anyone other than you, or anyone who is outside of your specific institution i.e. your school, your care home.

It may be helpful here to introduce your positionality . That is, let your reader know where you stand in relation to your proposed study. You are invited to offer a discussion of how you are situated in relation to the study being undertaken and how your situation influences your approach to the study.

The third context for your doctoral proposal is the literature:

All research is grounded in the literature surrounding your subject. A legitimate research question emerges from an identified contribution your work has the potential to make to the extant knowledge on your chosen subject. We usually refer to this as finding a gap in the literature. This context is explored in more detail in the second article.

You can search for material that will help with your literature review and your research methodology using The Open University’s Open Access Research repository and other open access literature.

Before moving to the next article ‘Defining your Research Methodology’, you might like to explore more about postgraduate study with these links:

- Professional Doctorate Hub

- What is a Professional Doctorate?

- Are you ready to study for a Professional Doctorate?

- The impact of a Professional Doctorate

Applying to study for a PhD in psychology

- Succeeding in postgraduate study - OpenLearn - Open University

- Are you ready for postgraduate study? - OpenLearn - Open University

- Postgraduate fees and funding | Open University

- Engaging with postgraduate research: education, childhood & youth - OpenLearn - Open University

We want you to do more than just read this series of articles. Our purpose is to help you draft a research proposal. With this in mind, please have a pen and paper (or your laptop and a notebook) close by and pause to read and take notes, or engage with the activities we suggest. You will not have authored your research proposal at the end of these articles, but you will have detailed notes and ideas to help you begin your first draft.

More articles from the research proposal collection

Defining your research methodology

Your research methodology is the approach you will take to guide your research process and explain why you use particular methods. This article explains more.

Level: 1 Introductory

Addressing ethical issues in your research proposal

This article explores the ethical issues that may arise in your proposed study during your doctoral research degree.

Writing your proposal and preparing for your interview

The final article looks at writing your research proposal - from the introduction through to citations and referencing - as well as preparing for your interview.

Free courses on postgraduate study

Are you ready for postgraduate study?

This free course, Are you ready for postgraduate study, will help you to become familiar with the requirements and demands of postgraduate study and ensure you are ready to develop the skills and confidence to pursue your learning further.

Succeeding in postgraduate study

This free course, Succeeding in postgraduate study, will help you to become familiar with the requirements and demands of postgraduate study and to develop the skills and confidence to pursue your learning further.

This free OpenLearn course is for psychology students and graduates who are interested in PhD study at some future point. Even if you have met PhD students and heard about their projects, it is likely that you have only a vague idea of what PhD study entails. This course is intended to give you more information.

Become an OU student

Ratings & comments, share this free course, copyright information, publication details.

- Originally published: Tuesday, 27 June 2023

- Body text - Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 : The Open University

- Image 'quantitative methods versus qualitative methods - shows 10% of people getting a cat instead of a dog v why they got a cat.' - The Open University under Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 license

- Image 'Succeeding in postgraduate study' - Copyright: © Everste/Getty Images

- Image 'Are you ready for postgraduate study?' - Copyright free

- Image 'Applying to study for a PhD in psychology' - Copyright free

- Image 'Writing your research proposal' - Copyright free

- Image 'Defining your research methodology' - Copyright free

- Image 'Addressing ethical issues in your research proposal' - Copyright: Photo 50384175 / Children Playing © Lenutaidi | Dreamstime.com

- Image 'Writing your proposal and preparing for your interview' - Copyright: Photo 133038259 / Black Student © Fizkes | Dreamstime.com

Rate and Review

Rate this article, review this article.

Log into OpenLearn to leave reviews and join in the conversation.

Article reviews

For further information, take a look at our frequently asked questions which may give you the support you need.

Learn how to write a PhD proposal that will stand out from the rest

Feb 27, 2019

Here, we show you how to write a PhD proposal that will stand out from the hundreds of others that are submitted each day.

Before we do though, know one thing :

The research you describe when you write your PhD proposal won’t look anything like the research you finally write up in your PhD thesis.

Wait, what ?

That’s not a typo. Everyone’s research changes over time. If you knew everything when you were writing up your proposal there wouldn’t be any point doing the PhD at all.

So, what’s the point of the proposal?

Your proposal is a guide, not a contract . It is a plan for your research that is necessarily flexible. That’s why it changes over time.

This means that the proposal is less about the robustness of your proposed research design and more about showing that you have

1. Critical thinking skills

2. An adequate grasp of the existing literature and know how your research will contribute to it

3. Clear direction and objectives. You get this by formulating clear research questions

4. Appropriate methods. This shows that you can link your understanding of the literature, research design and theory

5. An understanding of what’s required in a PhD

6. Designed a project that is feasible

Your PhD thesis. All on one page.

Use our free PhD structure template to quickly visualise every element of your thesis.

What is a PhD proposal?

Your PhD proposal is submitted as part of your application to a PhD program. It is a standard means of assessing your potential as a doctoral researcher.

When stripped down to its basic components, it does two things:

Explains the ‘what’- t hese are the questions you will address and the outcomes you expect

Explains the ‘why’- t his is the case for your research, with a focus on why the research is significant and what the contributions will be.

It is used by potential supervisors and department admission tutors to assess the quality and originality of your research ideas, how good you are at critical thinking and how feasible your proposed study is.

This means that it needs to showcase your expertise and your knowledge of the existing field and how your research contributes to it. You use it to make a persuasive case that your research is interesting and significant enough to warrant the university’s investment.

Above all though, it is about showcasing your passion for your discipline . A PhD is a hard, long journey. The admissions tutor want to know that you have both the skills and the resilience required.

What needs to be included in a PhD proposal?

Exactly what needs to be included when you write your PhD proposal will vary from university to university. How long your proposal needs to be may also be specified by your university, but if it isn’t, aim for three thousand words.

Check the requirements for each university you are applying for carefully.

Having said that, almost all proposals will need to have four distinct sections.

1. Introduction

2. the research context.

3. The approach you take

4. Conclusion

In the first few paragraphs of your proposal, you need to clearly and concisely state your research questions, the gap in the literature your study will address, the significance of your research and the contribution that the study makes.

Be as clear and concise as you can be. Make the reader’s job as easy as possible by clearly stating what the proposed research will investigate, what the contribution is and why the study is worthwhile.

This isn’t the place for lots of explanatory detail. You don’t need to justify particular design decisions in the introduction, just state what they are. The justification comes later.

In this section, you discuss the existing literature and the gaps that exist within it.

The goal here is to show that you understand the existing literature in your field, what the gaps are and how your proposed study will address them. We’ve written a guide that will help you to conduct and write a literature review .

Chances are, you won’t have conducted a complete literature review, so the emphasis here should be on the more important and well-known research in your field. Don’t worry that you haven’t read everything. Your admissions officer won’t have expected you to. Instead, they want to see that you know the following:

1. What are the most important authors, findings, concepts, schools, debates and hypotheses?

2. What gaps exist in the literature?

3. How does your thesis fill these gaps?

Once you have laid out the context, you will be in a position to make your thesis statement . A thesis statement is a sentence that summarises your argument to the reader. It is the ‘point’ you will want to make with your proposed research.

Remember, the emphasis in the PhD proposal is on what you intend to do, not on results. You won’t have results until you finish your study. That means that your thesis statement will be speculative, rather than a statement of fact.

For more on how to construct thesis statements, read this excellent guide from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill who, incidentally, run a great academic writing blog you should definitely visit.

3. The approach you will take

This is the section in which you discuss the overall research design and is the most important component of the proposal. The emphasis here is on five things.

1. The overall approach taken (is it purely theoretical, or does it involve primary or empirical research? Maybe it’s both theoretical and empirical?)

2. The theoretical perspective you will use when you design and conduct your research

3. Why you have chosen this approach over others and what implications this choice has for your methods and the robustness of the study

4. Your specific aims and objectives

5. Your research methodology

In the previous section you outlined the context. In this section you explain the specific detail of what your research will look like.

You take the brief research design statements you made in the introduction and go into much more detail. You need to be relating your design decisions back to the literature and context discussion in the previous section.

The emphasis here is on showing that there is a logical flow. There’s no point highlighting a gap in the literature and then designing a study that doesn’t fill it.

Some of the detail here will only become clear once you have started the actual research. That’s fine. The emphasis in your proposal should be on showing that you understand what goes into a PhD.

So, keep it general.

For example, when talking about your methodology, keep things deliberately broad and focus on the overarching strategy. For example, if you are using interviews, you don’t need to list every single proposed interview question. Instead, you can talk about the rough themes you will discuss (which will relate to your literature review and thesis/project statement). Similarly, unless your research is specifically focusing on particular individuals, you don’t need to list exactly who you will interview. Instead, just state the types of people you will interview (for example: local politicians, or athletes, or academics in the UK, and so on).

4. Concluding paragraphs

There are a number of key elements to a proposal that you will need to put in the final paragraphs.

These include:

1. A discussion on the limitations of the study

2. A reiteration of your contribution

3. A proposed chapter structure (this can be an appendix)

4. Proposed month-by-month timetable (this can also be an appendix). The purpose of this timetable is to show that you understand every stage required and how long each stage takes relative to others.

Tips to turn an average proposal into one that will be accepted

1. be critical.

When you are making your design decisions in section three, you need to do so critically. Critical thinking is a key requirement of entry onto a PhD programme. In brief, it means not taking things at face value and questioning what you read or do. You can read our guide to being critical for help (it focuses on the literature review, but the take home points are the same).

2. Don’t go into too much detail too soon in your proposal

This is something that many people get wrong. You need to ease the reader in gradually . Present a brief, clear statement in the introduction and then gradually introduce more information as the pages roll on.

You will see that the outline we have suggested above follows an inverted pyramid shape.

1. In section one, you present the headlines in the introductory paragraphs. These are the research questions, aims, objectives, contribution and problem statement. State these without context or explanation.

2. When discussing the research context in section two, you provide a little more background. The goal here is to introduce the reader to the literature and highlight the gaps.

3. When describing the approach you will take, you present more detailed information. The goal here is to talk in very precise terms about how your research will address these gaps, the implications of these choices and your expected findings.

3. Be realistic

Don’t pretend you know more than you do and don’t try to reinvent your discipline .

A good proposal is one that is very focused and that describes research that is very feasible. If you try to design a study to revolutionise your field, you will not be accepted because doing so shows that you don’t understand what is feasible in the context of a PhD and you haven’t understood the literature.

4. Use clear, concise sentences

Describe your research as clearly as possible in the opening couple of paragraphs. Then write in short, clear sentences. Avoid using complex sentences where possible. If you need to introduce technical terminology, clearly define things.

In other words, make the reader’s job as easy as possible.

5. Get it proofread by someone else

We’ve written a post on why you need a proofreader .

Simple: you are the worst person to proofread your own work.

6. Work with your proposed supervisor, if you’re allowed

A lot of students fail to do this. Your supervisor isn’t your enemy. You can work with them to refine your proposal. Don’t be afraid to reach out for comments and suggestions. Be careful though. Don’t expect them to come up with topics or questions for you. Their input should be focused on refining your ideas, not helping you come up with them.

7. Tailor your proposal to each department and institution you are applying to

Admissions tutors can spot when you have submitted a one-size-fits-all proposal. Try and tailor it to the individual department. You can do this by talking about how you will contribute to the department and why you have chosen to apply there.

Follow this guide and you’ll be on a PhD programme in no time at all.

If you’re struggling for inspiration on topics or research design, try writing a rough draft of your proposal. Often the act of writing is enough for us to brainstorm new ideas and relate existing ideas to one another.

If you’re still struggling, send your idea to us in an email to us and we’ll give you our feedback.

Hello, Doctor…

Sounds good, doesn’t it? Be able to call yourself Doctor sooner with our five-star rated How to Write A PhD email-course. Learn everything your supervisor should have taught you about planning and completing a PhD.

Now half price. Join hundreds of other students and become a better thesis writer, or your money back.

Share this:

13 comments.

A wonderful guide. I must say not only well written but very well thought out and very efficient.

Great. I’m glad you think so.

Thanks for sharing. Makes navigating through the proposal lot easier

Great. Glad you think so!

An excellent guide, I learned a lot thank you

Great job and guide for a PhD proposal. Thank you!

You’re welcome!

I am going to start writing my Ph.D. proposal. This has been so helpful in instructing me on what to do. Thanks

Thanks! Glad you thought so.

A very reassuring guide to the process. Thank you, Max

I appreciate the practical advice and actionable steps you provide in your posts.

Glad to hear it. Many thanks.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Search The PhD Knowledge Base

Most popular articles from the phd knowlege base.

The PhD Knowledge Base Categories

- Your PhD and Covid

- Mastering your theory and literature review chapters

- How to structure and write every chapter of the PhD

- How to stay motivated and productive

- Techniques to improve your writing and fluency

- Advice on maintaining good mental health

- Resources designed for non-native English speakers

- PhD Writing Template

- Explore our back-catalogue of motivational advice

Planning your PhD research: A 3-year PhD timeline example

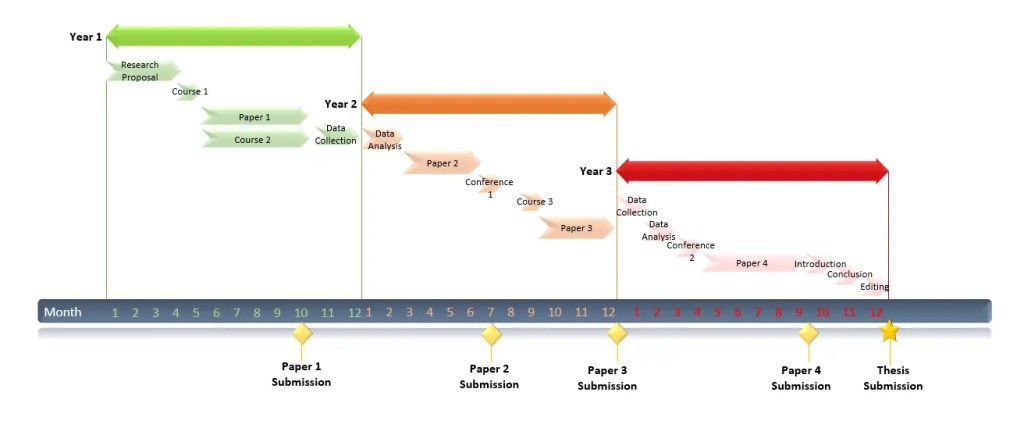

Planning out a PhD trajectory can be overwhelming. Example PhD timelines can make the task easier and inspire. The following PhD timeline example describes the process and milestones of completing a PhD within 3 years.

Elements to include in a 3-year PhD timeline

The example scenario: completing a phd in 3 years, example: planning year 1 of a 3-year phd, example: planning year 2 of a 3-year phd, example: planning year 3 of a 3-year phd, example of a 3 year phd gantt chart timeline, final reflection.

Every successful PhD project begins with a proper plan. Even if there is a high chance that not everything will work out as planned. Having a well-established timeline will keep your work on track.

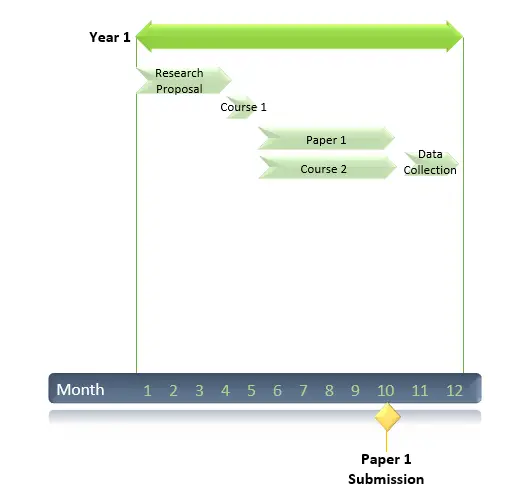

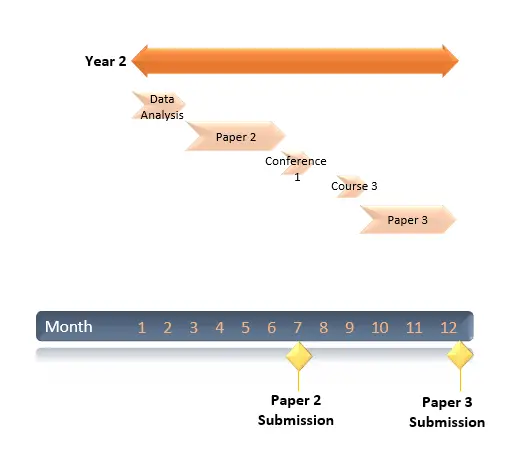

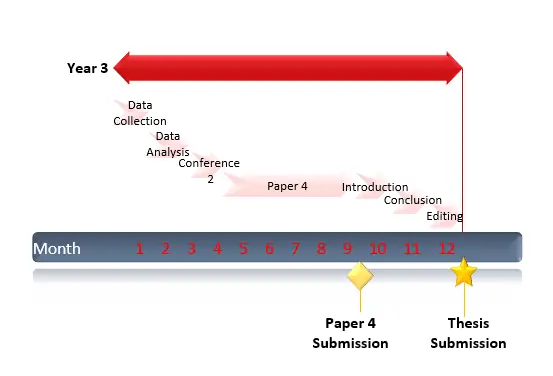

What to include in a 3-year PhD timeline depends on the unique characteristics of a PhD project, specific university requirements, agreements with the supervisor/s and the PhD student’s career ambitions.

For instance, some PhD students write a monograph while others complete a PhD based on several journal publications. Both monographs and cumulative dissertations have advantages and disadvantages , and not all universities allow both formats. The thesis type influences the PhD timeline.

Furthermore, PhD students ideally engage in several different activities throughout a PhD trajectory, which link to their career objectives. Regardless of whether they want to pursue a career within or outside of academia. PhD students should create an all-round profile to increase their future chances in the labour market. Think, for example, of activities such as organising a seminar, engaging in public outreach or showcasing leadership in a small grant application.

The most common elements included in a 3-year PhD timeline are the following:

- Data collection (fieldwork, experiments, etc.)

- Data analysis

- Writing of different chapters, or a plan for journal publication

- Conferences

- Additional activities

The whole process is described in more detail in my post on how to develop an awesome PhD timeline step-by-step .

Many (starting) PhD students look for examples of how to plan a PhD in 3 years. Therefore, let’s look at an example scenario of a fictional PhD student. Let’s call her Maria.

Maria is doing a PhD in Social Sciences at a university where it is customary to write a cumulative dissertation, meaning a PhD thesis based on journal publications. Maria’s university regulations require her to write four articles as part of her PhD. In order to graduate, one article has to be published in an international peer-reviewed journal. The other three have to be submitted.

Furthermore, Maria’s cumulative dissertation needs an introduction and conclusion chapter which frame the four individual journal articles, which form the thesis chapters.

In order to complete her PhD programme, Maria also needs to complete coursework and earn 15 credits, or ECTS in her case.

Maria likes the idea of doing a postdoc after her graduation. However, she is aware that the academic job market is tough and therefore wants to keep her options open. She could, for instance, imagine to work for a community or non-profit organisation. Therefore, she wants to place emphasis on collaborating with a community organisation during her PhD.

You may also like: Creating awesome Gantt charts for your PhD timeline

Most PhD students start their first year with a rough idea, but not a well-worked out plan and timeline. Therefore, they usually begin with working on a more elaborate research proposal in the first months of their PhD. This is also the case for our example PhD student Maria.